#capital and empire

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

SUN COMING UP ON A DREAM COME AROUND ONE HUNDRED YEARS FROM THE EMPIRE NOW SUN COMING UP ON A WORLD THAT’S EASY NOW ONE HUNDRED YEARS FROM NOW ONE HUNDRED YEARS FROM NOW

#empire now#hozier#hozier unheard#its sooo ursula k le guin ‘we live in capitalism. it’s power seems inescapable. so did the divine right of kings’#ace.txt

769 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imperial Star Destroyer

#Star Wars#Imperial Star Destroyer#Star Destroyer#Capital Ship#Imperial Navy#Galactic Empire#Scifi#science fiction#starship#starcruiser#spaceship

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

Growing up I was told that the reason Cuba and North Korea was in poverty was "because of their dictators."

Nobody talked about how the US has a decades-long sanction on Cuba which exists because the US Empire does not want communism.

Or how about 80% of North Korea was destroyed during the Korean War.

The US does not have a "free press" because the state does not allow corporate media to say the word "genocide," because Israel is their proxy state.

#US Empire#US politics#Media theory#Corporate media#Genocide#Israel#Palestine#Cuba#North Korea#Socialism#Communism#Capitalism

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just want to note that while I don't see it happening here, I read comments (no longer comment) on other places like Reddit (just read one last night), and supposed fans of Carmy say things like: But was what Chef David did to Carmy necessary to make him so good?

And this is the kind of thinking and system that we live under. That's why Claire's doo doo is normalized, and people are like: Make more backstory for this person that reminds Carmy of his mom and makes him have panic attacks and doesn't require anything of him in the way of change.

People are conditioned to accept these kinds of narratives without questioning them. Trapping you in the system, placating you, numbing you. While still extracting everything that feeds them.

Instead of trying to create something new, of trying to stay becoming who you really are, and not who you have been conditioned to be. The Bear seems like a big warning about that, to me.

I don't think this show will side with the idea that Carmy will just remain stuck and move back to Chicago and take Mikey's slot and fix everything. Stuff like that doesn't get fixed overnight. He's happiest when he's free of it, they've already shown that.

Despite the nosedive into his own heart of darkness for Carmy in S3, we see him coming out of the other side of it. Syd has been exposed to all of this, too, well before Carmy. They have hinted at and not really shown the misogynoir she's had to endure in the industry.

These two both agreed in S1 to make something different. It's time to let it rip in S4!

#sydcarmy#the bear meta#Demon Chef David#Anti-Clair Bear#late stage capitalism#empire#Claire is stuck too look at her work life balance

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

P e r s e p o l i s

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Malediction Ritual Against Evil Empires

(Dark Moon Ritual Dec. 1, 2024)

youtube

Suggested materials are: * a candle * a lighter or matches * a piece of paper * a writing instrument Though if you lack any of these you can simply follow along on the video stream. The candle will be lit in the ritual, so keep it at hand for now. *If you are not a member but are interested in getting involved, you can find a link to our [Capital Area Satanists’] Discord at CapitalAreaSatanists.org * Credits Opening and Closing of Ritual: The Organizers of Capital Area Satanists * The Malediction Against Evil Empires: Piper Furiosa (Inspired by Greek Curse Tablets & Archbishop Gavin Dunbar’s “Monition of Cursing") * Performed and Filmed By: Felo de Se and Piper Furiosa * Video Editing: Piper Furiosa

#satanism#satanic ritual#ritual#moon ritual#Capital Area Satanists#Piper Furiosa#Felo de Se#dark moon ritual#Malediction Against Evil Empires#Youtube

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atlantis: the Lost Empire subverts the "White Savior" trope so well and here's my Ted talk tangent

Atlantis: the Lost Empire is just Avatar but with a smarter story. Both films feature a young white man discovering a foreign culture, falling for the culture's princess, and saving the natives' way of life. Both films commentate on the exploitation of indigenous people for their resources. The biggest fundamental difference between Avatar and Atlantis is how the white male leads approach their scenarios. Milo Thatch is a wide-eyed scholar who just wants to learn; Jake Sullivan is a soldier infiltrating the culture so he can exploit them. Milo never had any intention of hurting/exploiting the natives but the people around him did; Jake knew the end goal was exploitation and only changed his alliance when he fell in love. Kida comes to Milo for help and he approaches her with respect not condescension; Jake has to learn the planet and its people are worthy of respect. Milo is attracted to Kida but he doesn't save her so he can get the girl; he saves her to save her people (getting the girl was a luxury and even then, it's obvious they'll take things slow cuz there's more important things than romance like reconnecting the Atlanteans with the lost parts of their culture). The Atlanteans are also not harmless, primitive natives. They had super-advanced technology ie the Leviathan that took out a modern submarine in like 2 minutes while the Navi are overtly primitive, their simplicity treated as a virtue. The Atlanteans were so advanced that they sent themselves back to the Stone Age with their war tech. This little detail keeps the Atlanteans from being hippie-dippie natives who need rescuing and make them a cautionary tale; they used to be greedy, hyper-advanced warmongers and that hubris leaves their race and culture on the verge of extinction. Both the Navi and Atlanteans have spiritual, mystical aspects to them, but the Navi are anti-tech while it's only the rediscovery of their tech that allows the Atlanteans to save themselves. The primitive life we see the Atlanteans lead is not presented as ideal; it is the death throes of a culture, a fatal stagnation at the bottom of the world. When Kida and Milo meet, it's not the typical "more advanced culture taking from the weaker culture" that has come to define first contact between societies. It's quid pro quo: we both answer, we both listen, we both come away with more not one party coming away with less. No one is humbled or talked down to. As for the antagonists of both films (Avatar and Atlantis) the antagonists of Avatar are just cardboard cutouts. The antagonists of Atlantis are just disinherited individuals coming together for a treasure hunt. There's a gag where Milo asks what each character seeks and they all say "Money" but that's not it. They each want to pursue goals unique to them and they need money to do it. When the chips are down and it's either money or NOT dooming an entire lost tribe to death, they choose saving the tribe. The main big bads, Rourke and Helga, have just spent a day walking through a ruined city where people live in the remains of their greatness and think, "Yeah, we are so stealing their technology so we can reenact the fall of their civilization on our OWN civilization. Why? Cuz capitalism." Why am I talking so much about Atlantis but not Avatar? Because Avatar lacks depth. I've watched Atlantis a thousand times on my cheap 2000s-era TV and get pulled in each time but Avatar's just a pretty screensaver playing in the background.

#ted talks#tangents#atlantis the lost empire#milo thatch#atlantis#disney atlantis#kidagakash#avatar#avatar way of water#jakesullivan#jake sully#white savior#story analysis#commentary#anti capitalism#capitalism#james cameron#corporate greed#worldbuilding#rant#personal rant#rourke#miles quaritch#helga sinclair#kidada jones#disney animation

331 notes

·

View notes

Text

[…] “What burns in Palestine and Los Angeles today are symptoms of the same disease: a system that values conquest over conservation, profit over people, expansion over existence.”

[…] “… we either stand together against this destruction, or we all burn separately.”

#united states#california#palestine#capitalism#empire#environment#ecology#human rights#climate change#justice#systems thinking

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

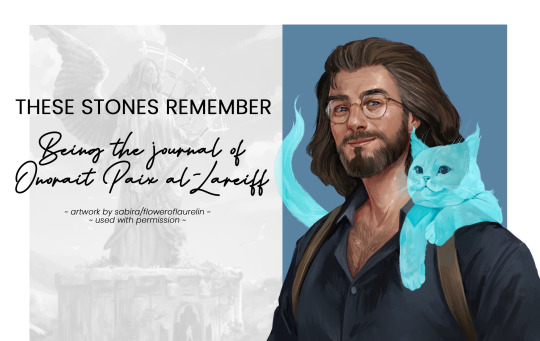

These Stones Remember - LXXX - Epilogue 3: Companion Reader (part 2 of 2) - STORY NOW COMPLETE

Bet you didn’t think you’d see this banner ^ again, did you? ;)

The final part of These Stones Remember has just been posted to AO3: the second of the two Companion Readers. This brings to an end the story that consumed a year of my life, and that brought me such joy as well as some wonderful new friends.

Read it in full at AO3: These Stones Remember - LXXX - Epilogue 3: Companion Reader (part 2 of 2)

Make sure you read to the very end, as not only is there some more beautiful art by Sabira (@floweroflaurelin) but there's also a special treat for you in the end notes ;-)

#these stones remember#being the journal of onorait paix al-lareiff#empires smp#empiresblr#pixlriffs#empires pixlriffs#empires fanfic#mcytblr#mcyt#the ancient capital#pixandria#the copper king

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

In case you’re having a bad day, remember that Steve and Robin held hands, canonically.

Have a wonderful rest of your day

#you know that tiktok trend about the Roman Empire#this is my Roman Empire#i think about this constantly#steve harrington#robin buckley#stobin friendship#platonic stobin#stobin#platonic with a capital p#platonic soulmates#stranger things

250 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whenever Brits are like "tea is our national drink, our culture, our personality, our mental health" I think of our hill country blanketed in a patchwork quilt of human suffering and ongoing violent colonialism and want to smash all their tea cups. Your genocidal leaf juice is nothing to be proud of. The present day tea pluckers are the descendants of the Indians you enslaved and they still live in unthinkable poverty in the line houses you built to house them like cattle. The families whose farmlands you robbed have been starving for generations. Every sip of your leaf juice is soaked in blood and you drink it like vampires.

Tea will never belong to you. It's our legacy of grief, and your shame.

Drink your tea and shut the fuck up.

#sri lanka#'but my parents were immigrants!' 'and you're living in a genocidal country that's still sucking the marrow from the global south. so.'#'but my parents were indians!' 'ok? drink your chai and think about the stateless south indian tea pluckers? what is your point?'#if you live in britain you enjoy the fruits of its empire even if you're at the bottom of the food chain#that's why middle class Asians and Africans migrate to europe even if it means they have to earn a living on minimum wage#you can't share a race and country with sue braverman and tell me that your origins can make you any less complicit#british culture#tea#british empire#colonialism#british colonialism#colonization#extractive colonialism#tourism#capitalism#indigenous rights#indian ocean slavery#slavery#white supremacy#knee of huss#food culture#cash crops#monoagriculture#ecocide

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

(context for watcher/listener!sausage can be found in the “videos” tag on my blog if you want it, but this ficlet can be read without said context)

- - -

“Y’know, of all the Hermits I was expecting to be pulling me into a dark corner tonight, I did not expect you to be first, Grian! I love the initiative!”

“I’m going to pretend I didn’t hear that,” Grian says in a voice near a hiss. He’s got Sausage by the wrist, leading him into a small area of the upper floor of the tavern in Sanctaury that does look like it was built for the exact purpose Sausage is implying. Grian decides to ignore that as well.

“What are you doing here?” Grian’s straight to the point. He always has to be, with these Things, if he doesn’t want to get trapped in a loop of slant rhyming pleasantries.

“What do you mean?” Sausage asks, shaking his wrist out of Grian’s tight grip and leaning comfortably against the wall. “This is where I live. It’s my home. If anything, I should be asking you mysterious strangers what you’re doing here, but I’m sure you’ve heard that question enough for one day.”

“You know exactly what I mean.” Grian crosses his arms and tries his best not to look petulant, but he sure feels like it. “I thought They’d given up on trying to snatch me back, so why would They send you of all people? What’s your game?”

Sausage laughs, honest to god laughs, like he can’t believe Grian’s even asking him such a question. Grian thinks it’s a reasonable question, in this scenario, but what he thinks and what’s reasonable rarely seems to matter with these things.

“They didn’t send me,” Sausage looks him up and down in that way that makes Grian have to physically stop himself from curling inwards. This is why he never talks to Them. “Nobody sends me anywhere, they don’t tell me what to do and I like it that way! I just do my own thing. Isn’t that what you’re doing?”

“No you’re not! You’re not- you can’t be! That’s not how this works!” Grian begins to notice that he’s no longer whisper-shouting and starting to just-normal-shout and takes a deep breath, trying not to draw the attention of his friends enjoying themselves on the floor below. And, realistically, in the other dark corners Sausage seems to have built into this place.

“That’s exactly how this works. You didn’t think you were the only person who’d left, did you?”

Grian opens his mouth, closes it, and thinks. In hindsight… yeah, he had kind of assumed he’d been the only person who’d left. Not for lack of trying, probably- but They’d tried for so long to get him back, kept him closely surveilled even when They’d accepted he was gone- surely some people had caved to that pressure eventually. When there was no sign They’d ever let up, ever let you go… he could understand eventually letting it overtake you.

“Did- did you leave, too?” Grian doesn’t remember the last time he saw Sausage’s face. He didn’t know him back then, of course. He probably would’ve connected the man with the person Pearl so often spoke about sooner. But he knows it’s been a long time, maybe even longer than the last time Grian had gone There. He doesn’t think Sausage had been There, that day. This might explain why.

“Eh, not quite?”

“What-“ Grian flails, both mentally and with his arms a bit. “What do you mean not quite?”

“Exactly what I said! I was never- it’s complicated, y’know?”

“Explain. Now.”

“Well, uh,” Sausage seems to flounder for the first time since this conversation started, which Grian is choosing to take as a victory. “Look, I wasn’t- they didn’t pick me. For this, or for anything, ever. Sometimes things just happen and you get yourself into a place you shouldn’t have and then… they can’t get rid of me, I can’t get rid of them, it is what it is.”

Grian stares at him for a long moment. Really stares at him, in the same way Sausage had looked him over earlier, in the same way that makes you feel like you’re under a microscope. Judging by the sudden nerves in his eyes, Grian can assume he feels it too. Grian remembers his face. That had been the first thing he’d noticed, when the Hermits had arrived. It had been a long time since they’d seen each other, but Grian knew his face. And now that Grian was studying him, really trying to remember… he’s not sure he quite likes what memories he’s dredging up.

“What are you?”

“Grian!” Sausage’s voice drips with mock offense as he puts his hand up to partially cover his mouth. “We only just met, do you think that’s polite?”

“Answer the question,” Grian sighs. How Pearl deals with this man on the regular, he doesn’t know.

“Well, if you insist.” Sausage sighs, somehow even more exaggerated than his previous movements. “It’s just… if you’ll believe it, it’s somehow even harder to answer the first question.”

“It shouldn’t be,” Grian says. “They’re two very different People, you know.”

“But they’re the same species, when it all comes down to it. Like, you might be very different than a chicken, but you’re both birds in the long run.”

Grian pauses, fanning his wings out a bit behind him as he considers. “I don’t think that metaphor’s quite landing the way you want it to.”

“No, me neither. Anyways, let me continue.

When they don’t pick you, things go a little differently! You don’t get sorted onto one side or the other since, well, you’re not really supposed to be there? So I’m… whatever I want to be, really. I think I’m feeling like more of a Listener, today, but we’ll see how the mood shifts.”

Grian flinches at the Name, on instinct. He doesn’t know how to feel about that, so he files it away to be dealt with at a later date. As for the rest of what Sausage said-

“What?”

“You heard me.” Sausage shrugs. He’s so nonchalant, Grian thinks he might strangle him, if not for the worry that that’s exactly what he wants out of this, somehow.

“Did I? Did I hear you?” Grian wants to pace, but that requires leaving the security of the corner, so he forces his feet to root themselves to the floor. “I thought- I thought you had to- if you wanted to change sides, I thought you had to-“

Grian closes one eye and takes his thumb to it, twisting the finger into his eyelid. The gesture seems to get the point across.

“Well, that’s the funny thing about this, actually.” From the way he’s been talking, Grian assumed Sausage thought this whole thing was funny. He restrains himself from saying that out loud if only so Sausage will finish his explanation.

Sausage reaches up to his left eye, pulls his eye lid back a bit, and unceremoniously pops out his prosthetic eye.

“All these processes and rituals actually have a lot of loopholes.”

Grian doesn’t know what face he’s making, but it’s enough to make Sausage giggle while he pops the eye back in. Because of course he does. Because this how his day is going, apparently. Walk through a weird portal in his basement and wake up in a world filled with his friends who don’t recognize him and also a guy he only ever saw There, who he was never supposed to see again. Sure. Of course he’s laughing about it. Grian thinks if he was a slightly different person, he’d be laughing too. It is, undeniably, absurd.

“Well, I think we’re done here then!” Grian would probably object if he weren’t so shocked about the loopholes. As it is, he just stands there a bit stupidly.

Sausage turns away to return to the party before turn around again for just a moment, reaching over, and ruffling Grian’s hair. That shocks him enough to shake him out of his stupor and swat Sausage’s hand away, though not before his hair is suitably messed up.

“What was that for?!”

Sausage smiles as he reaches up to rough up his own hair as well. “I assumed you didn’t want your friends asking questions about why you were dragging me into a dark corner, you know?” Sausage even goes far enough to pull his shirt a bit out of where it’s tucked into his pants, because of course he does. Grian tries not to cringe, but Sausage is right about this one thing. It is the easiest way to dodge any questions about where he’d gone off to- at the expense of the many knowing looks and teasing remarks he’ll be getting from the other Hermits instead.

“Have a good night, Grian!” Sausage calls over his shoulder as he turns to leave for real this time. “And remember, drinks are on me for all you guests tonight! You look like you need it.”

#empires smp#hermitcraft#grian#mythicalsausage#hermitfic#empiresfic#long post#my writing#….do i need to tag shipping on this#they’re not actually DOING anything. and i would say i’m not really going much further than sausage usually does#but like. idk man. if i wake up in the morning and decide i need to tag shipping i will#anyways. fics for an audience of like two people total#but that’s ok cause i like this SO MUCH#the first few sentences have been rotting in my tumblr drafts for like at least two months#and i finally kicked myself into gear to just finish it#and i had fun! i liked the way i used capitalization here to really wedge the difference between how these two think of the watchers#(and listeners)#grian doesn’t necessarily respect them but he does still see them as Other. and he’s maybe a little afraid#so all the important stuff gets capitalized#sausage doesn’t. he doesn’t respect them and he doesn’t fear them and they’re just a weird bureaucracy to him#so no capitalization!#also ten seconds after posting this i got a post on my dash#of sausage posting a screenshot of e’s tumblr post about him checking tumblr in their twitter replies#terrifying. hey king if you see this keep the bit up. i think it’s funny#my art

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

one of the reasons it's so bad the Baten Kaitos remaster on Switch didn't include the English dub:

when you finally reach the Empire pretty far in the game and walk around the capital city, you see first-hand how the propaganda machine of the Empire works, how they're telling their own citizens that the Empire is the greatest, other places are backwards, bringing imperial civilization is a benevolence, etc.

One of the first nameless NPCs you hear parroting the imperial line is a kid NPC speaking with a British accent. Which I always thought was a really neat dubbing choice.

#baten kaitos#dubbing#smart localization choices#later on you delve in the price the Empire expects from its worker population but the capital is only the people who most benefit

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In these circumstances, the commercial economy of the fur trade soon yielded to industrial economies focused on mining, forestry, and fishing. The first industrial mining (for coal) began on Vancouver Island in the early 1850s, the first sizeable industrial sawmill opened a few years later, and fish canning began on the Fraser River in 1870. From these beginnings, industrial economies reached into the interstices of British Columbia, establishing work camps close to the resource, and processing centers (canneries, sawmills, concentrating mills) at points of intersection of external and local transportation systems. As the years went by, these transportation systems expanded, bringing ever more land (resources) within reach of industrial capital. Each of these developments was a local instance of David Harvey's general point that the pace of time-space compressions after 1850 accelerated capital's "massive, long-term investment in the conquest of space" (Harvey 1989, 264) and its commodifications of nature. The very soil, Marx said in another context, was becoming "part and parcel of capital" (1967, pt. 8, ch. 27).

As Marx and, subsequently, others have noted, the spatial energy of capitalism works to deterritorialize people (that is, to detach them from prior bonds between people and place) and to reterritorialize them in relation to the requirements of capital (that is, to land conceived as resources and freed from the constraints of custom and to labor detached from land). For Marx the

wholesale expropriation of the agricultural population from the soil... created for the town industries the necessary supply of a 'free' and outlawed proletariat (1967, pt. 8, ch. 27).

For Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari (1977) - drawing on insights from psychoanalysis - capitalism may be thought of as a desiring machine, as a sort of territorial writing machine that functions to inscribe "the flows of desire upon the surface or body of the earth" (Thomas 1994, 171-72). In Henri Lefebvre's terms, it produces space in the image of its own relations of production (1991; Smith 1990, 90). For David Harvey it entails the "restless formation and reformation of geographical landscapes," and postpones the effects of its inherent contradictions by the conquest of space-capitalism's "spatial fix" (1982, ch. 13; 1985, 150, 156). In detail, positions differ; in general, it can hardly be doubted that in British Columbia industrial capitalism introduced new relationships between people and with land and that at the interface of the native and the nonnative, these relationships created total misunderstandings and powerful new axes of power that quickly detached native people from former lands. When a Tlingit chief was asked by a reserve commissioner about the work he did, he replied

I don't know how to work at anything. My father, grandfather, and uncle just taught me how to live, and I have always done what they told me-we learned this from our fathers and grandfathers and our uncles how to do the things among ourselves and we teach our children in the same way.

Two different worlds were facing each other, and one of them was fashioning very deliberate plans for the reallocation of land and the reordering of social relations. In 1875 the premier of British Columbia argued that the way to civilize native people was to bring them into the industrial workplace, there to learn the habits of thrift, time discipline, and materialism. Schools were secondary. The workplace was held to be the crucible of cultural change and, as such, the locus of what the premier depicted as a politics of altruism intended to bring native people up to the point where they could enter society as full, participating citizens. To draw them into the workplace, they had to be separated from land. Hence, in the premier's scheme of things, the small reserve, a space that could not yield a livelihood and would eject native labor toward the industrial workplace and, hence, toward civilization. Marx would have had no illusions about what was going on: native lives, he would have said, were being detached from their own means of production (from the land and the use value of their own labor on it) and were being transformed into free (unencumbered) wage laborers dependent on the social relations of capital. The social means of production and of subsistence were being converted into capital. Capital was benefiting doubly, acquiring access to land freed by small reserves and to cheap labor detached from land.

The reorientation of land and labor away from older customary uses had happened many times before, not only in earlier settler societies, but also in the British Isles and, somewhat later, in continental Europe. There, the centuries-long struggles over enclosure had been waged between many ordinary folk who sought to protect customary use rights to land and landlords who wanted to replace custom with private property rights and market economies. In the western highlands, tenants without formal contracts (the great majority) could be evicted "at will." Their former lands came to be managed by a few sheep farmers; their intricate local land uses were replaced by sheep pasture (Hunter 1976; Hornsby 1992, ch. 2). In Windsor Forest, a practical vernacular economy that had used the forest in innumerable local ways was slowly eaten away as the law increasingly favored notions of absolute property ownership, backed them up with hangings, and left less and less space for what E.P. Thompson calls "the messy complexities of coincident use-right" (1975, 241). Such developments were approximately reproduced in British Columbia, as a regime of exclusive property rights overrode a fisher-hunter-gatherer version of, in historian Jeanette Neeson's phrase, an "economy of multiple occupations" (1984, 138; Huitema, Osborne, and Ripmeester 2002). Even the rhetoric of dispossession - about lazy, filthy, improvident people who did not know how to use land properly - often sounded remarkably similar in locations thousands of miles apart (Pratt 1992, ch. 7). There was this difference: The argument against custom, multiple occupations, and the constraints of life worlds on the rights of property and the free play of the market became, in British Columbia, not an argument between different economies and classes (as it had been in Britain) but the more polarized, and characteristically racialized juxtaposition of civilization and savagery...

Moreover, in British Columbia, capital was far more attracted to the opportunities of native land than to the surplus value of native labor. In the early years, when labor was scarce, it sought native workers, but in the longer run, with its labor needs supplied otherwise (by Chinese workers contracted through labor brokers, by itinerant white loggers or miners), it was far more interested in unfettered access to resources. A bonanza of new resources awaited capital, and if native people who had always lived amid these resources could not be shipped away, they could be-indeed, had to be-detached from them. Their labor was useful for a time, but land in the form of fish, forests, and minerals was the prize, one not to be cluttered with native-use rights. From the perspective of capital, therefore, native people had to be dispossessed of their land. Otherwise, nature could hardly be developed. An industrial primary resource economy could hardly function.

In settler colonies, as Marx knew, the availability of agricultural land could turn wage laborers back into independent producers who worked for themselves instead of for capital (they vanished, Marx said, "from the labor market, but not into the workhouse") (1967, pt. 8, ch. 33). As such, they were unavailable to capital, and resisted its incursions, the source, Marx thought, of the prosperity and vitality of colonial societies. In British Columbia, where agricultural land was severely limited, many settlers were closely implicated with capital, although the objectives of the two were different and frequently antagonistic. Without the ready alternative of pioneer farming, many of them were wage laborers dependent on employment in the industrial labor market, yet often contending with capital in bitter strikes. Some of them sought to become capitalists. In M. A. Grainger's Woodsmen of the West, a short, vivid novel set in early modern British Columbia, the central character, Carter, wrestles with this opportunity. Carter had grown up on a rock farm in Nova Scotia, worked at various jobs across the continent, and fetched up in British Columbia at a time when, for a nominal fee, the government leased standing timber to small operators. He acquired a lease in a remote fjord and there, with a few men under towering glaciers at the edge of the world economy, attacked the forest. His chances were slight, but the land was his opportunity, his labor his means, and he threw himself at the forest with the intensity of Captain Ahab in pursuit of the white whale. There were many Carters.

But other immigrants did become something like Marx's independent producers. They had found a little land on the basis of which they hoped to get by, avoid the work relations of industrial capitalism, and leave their progeny more than they had known themselves. Their stories are poignant. A Czech peasant family, forced from home for want of land, finding its way to one of the coaltowns of southeastern British Columbia, and then, having accumulated a little cash from mining, homesteading in the province's arid interior. The homestead would consume a family's work while yielding a living of sorts from intermittent sales from a dry wheat farm and a large measure of domestic self-sufficiency-a farm just sustaining a family, providing a toe-hold in a new society, and a site of adaptation to it. Or, a young woman from a brick, working-class street in Derby, England, coming to British Columbia during the depression years before World War I, finding work up the coast in a railway hotel in Prince Rupert, quitting with five dollars to her name after a manager's amorous advances, traveling east as far as five dollars would take her on the second train out of Prince Rupert, working in a small frontier hotel, and eventually marrying a French Canadian farmer. There, in a northern British Columbian valley, in a context unlike any she could have imagined as a girl, she would raise a family and become a stalwart of a diverse local society in which no one was particularly well off. Such stories are at the heart of settler colonialism (Harris 1997, ch. 8).

The lives reflected in these stories, like the productions of capital, were sustained by land. Older regimes of custom had been broken, in most cases by enclosures or other displacements in the homeland several generations before emigration. Many settlers became property owners, holders of land in fee simple, beneficiaries of a landed opportunity that, previously, had been unobtainable. But use values had not given way entirely to exchange values, nor was labor entirely detached from land. Indeed, for all the work associated with it, the pioneer farm offered a temporary haven from capital. The family would be relatively autonomous (it would exploit itself). There would be no outside boss. Cultural assumptions about land as a source of security and family-centered independence; assumptions rooted in centuries of lives lived elsewhere seemed to have found a place of fulfillment. Often this was an illusion - the valleys of British Columbia are strewn with failed pioneer farms - but even illusions drew immigrants and occupied them with the land.

In short, and in a great variety of ways, British Columbia offered modest opportunities to ordinary people of limited means, opportunities that depended, directly or indirectly, on access to land. The wage laborer in the resource camp, as much as the pioneer farmer, depended on such access, as, indirectly, did the shopkeeper who relied on their custom.

In this respect, the interests of capital and settlers converged. For both, land was the opportunity at hand, an opportunity that gave settler colonialism its energy. Measured in relation to this opportunity, native people were superfluous. Worse, they were in the way, and, by one means or another, had to be removed. Patrick Wolfe is entirely correct in saying that "settler societies were (are) premised on the elimination of native societies," which, by occupying land of their ancestors, had got in the way (1999, 2). If, here and there, their labor was useful for a time, capital and settlers usually acquired labor by other means, and in so doing, facilitated the uninhibited construction of native people as redundant and expendable. In 1840 in Oxford, Herman Merivale, then a professor of political economy and later a permanent undersecretary at the Colonial Office, had concluded as much. He thought that the interests of settlers and native people were fundamentally opposed, and that if left to their own devices, settlers would launch wars of extermination. He knew what had been going on in some colonies - "wretched details of ferocity and treachery" - and considered that what he called the amalgamation (essentially, assimilation through acculturation and miscegenation) of native people into settler society to be the only possible solution (1928, lecture xviii). Merivale's motives were partly altruistic, yet assimilation as colonial practice was another means of eliminating "native" as a social category, as well as any land rights attached to it as, everywhere, settler colonialism would tend to do.

These different elements of what might be termed the foundational complex of settler colonial power were mutually reinforcing. When, in 1859, a first large sawmill was contemplated on the west coast of Vancouver Island, its manager purchased the land from the Crown and then, arriving at the intended mill site, dispersed its native inhabitants at the point of a cannon (Sproat 1868). He then worried somewhat about the proprieties of his actions, and talked with the chief, trying to convince him that, through contact with whites, his people would be civilized and improved. The chief would have none of it, but could stop neither the loggers nor the mill. The manager and his men had debated the issue of rights, concluding (in an approximation of Locke) that the chief and his people did not occupy the land in any civilized sense, that it lay in waste for want of labor, and that if labor were not brought to such land, then the worldwide progress of colonialism, which was "changing the whole surface of the earth," would come to a halt. Moreover, and whatever the rights or wrongs, they assumed, with unabashed self-interest, that colonists would keep what they had got: "this, without discussion, we on the west coast of Vancouver Island were all prepared to do." Capital was establishing itself at the edge of a forest within reach of the world economy, and, in so doing, was employing state sanctioned property rights, physical power, and cultural discourse in the service of interest."

- Cole Harris, “How Did Colonialism Dispossess? Comments from an Edge of Empire,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 94, No. 1 (Mar., 2004), p. 172-174.

#settler colonialism#settler colonialism in canada#dispossession#violence of settler colonialism#land theft#canadian history#indigenous people#first nations#reading 2024#cole harris#history of british columbia#reservation system#resource extraction#british empire#canada in the british empire#homesteading#marxist theory#capitalism#capitalism in canada#immigration to canada

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Under capitalism, the police prioritize property-owners and their wealth over people and public safety.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

#capitalism#militarism#climate change#us empire#US centralized empire#ecocide#american exceptionalism

23 notes

·

View notes