#but we were talking about the ways subjectivity in medieval poetry is different from modern literature

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Frank O’Hara, “Mayakovsky”

#frank o’hara#poetry#quote#literature#lit#beauty#subjectivity#wound#trauma#self acceptance#this really brilliant guy brought up this poem in one of my classes today and i am just wowed by it#the class was medieval lyric poetry and the professor didnt really understand why he brought it up at first#but we were talking about the ways subjectivity in medieval poetry is different from modern literature#and he said this poem reminded him of the more flexible subjectivity in first person narration in medieval poems#while this is obviously far from medieval i see his point#and i am so glad he brought it up because it is such a beautiful poem!#english major things#insecurity#self expression#mayakovsky#writing process#writing

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Romantic Period began in the late 18th century as a reaction against social, economic, and political changes that were occurring at the same time. It was a period of emotional expression, creativity, and imagination, characterized by an emphasis on feeling rather than reason. This movement sought to capture the beauty and mystery of nature through the exploration of various themes such as love, death, and nature. The works of authors such as William Wordsworth, Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and John Keats are considered to be among the most important works from this period. Notable achievements of the Romantic Period include a heightened interest in music and literature, a focus on individualism rather than communal values, and an embrace of new forms of expression. In short, the Romantic Period embodied a spirit of creativity and exploration that continues to influence modern culture today. An Overview of the Romantic Period and Key Features The Romantic Period was a highly influential movement in the world of literature and art that began in the late 18th century and continued through the mid-19th century. It was marked by a strong emphasis on emotional expression, individualism, and imagination. Key features of the Romantic Period include the rejection of the Enlightenment's emphasis on reason and logic, a fascination with nature, and a renewed interest in the medieval past. Romantics also placed a great deal of importance on the concept of the sublime, which referred to a sense of awe and terror that could be inspired by the grandeur and power of nature or the human imagination. The Romantic Period produced some of the most enduring literary works in history, including the poetry of William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and John Keats, as well as the novels of Jane Austen, Mary Shelley, and the Bronte sisters. This era in literature remains a fascinating and captivating subject for scholars and readers alike. Influences from the Enlightenment and French Revolution Hey there! Let's talk about the influences of the Enlightenment and French Revolution, shall we? These two events in history were major game changers and had a huge impact on society as we know it today. The Enlightenment paved the way for modern science and philosophy, emphasizing reason, individualism, and skepticism toward traditional authority. It provided the foundation for the French Revolution, which aimed for democracy, equality, and the abolition of feudalism and absolute monarchy. The reverberations of these two movements spread throughout Europe and beyond, influencing other revolutions and social movements and shaping our modern world. Pretty impressive stuff, right? Interest in Nature and Emotional Expressions Have you ever found yourself feeling overwhelmed by the beauty of nature? Maybe you stopped to watch a sunset or went for a hike in the woods and felt a sense of peace wash over you. It turns out that there's a scientific explanation for why nature can evoke such emotional reactions from us. Researchers have found that when we spend time in nature, our bodies release certain hormones that help reduce stress and anxiety. This may explain why so many people feel a deep connection to the natural world and why spending time in green spaces can be so therapeutic. So, next time you're feeling stressed out, try taking a walk outside and see if you notice a difference in your mood. New Literary Genres and Sub-Genres during this Time Have you noticed the recent explosion of new literary genres and sub-genres? It seems like every time I turn around, there's a new designation to categorize books. From "cli-fi" (climate fiction) to "wuxia" (Chinese martial arts fiction), there's something for everyone to sink their teeth into. It's exciting to see how the literary world is evolving and expanding, allowing for more diverse voices and stories to be heard. I can't wait to see what else emerges in the future!

Changes in Music during the Period It's fascinating how music has evolved over time. One period that sticks out is the Renaissance. During this time, music was moving away from the simplicity of the Middle Ages and becoming more complex. Composers were experimenting with different harmonies and rhythms, creating something that was both intricate and beautiful. As instruments became more advanced, they were able to produce a wider range of sounds, which in turn elevated the complexity of the music. It's interesting to think about how even centuries ago, artists were pushing the boundaries of what was possible and paving the way for future musicians to come. Impact of Industrialization on the Popularity of Romanticism It's no secret that industrialization changed the landscape of our world, but it also had a surprising impact on the arts. Romanticism, a cultural movement that valued individualism, nature, and emotion over rationality and tradition, emerged in the late 18th century during a time of great social and economic change. As the industrial revolution gained momentum, people began to feel disconnected from nature and the simplicity of life. Romanticism's emphasis on emotion and individual experience provided an escape from the rigidity and monotony of mechanized life. So while industrialization threatened to quell creativity and imagination, it actually helped fuel the popularity of Romanticism. Conclusion: The Romantic Period was a pivotal time in history- it brought new theories, literary works, and art forms that indelibly shaped culture as we know it today. It all began as a reaction against reason and the order of the Enlightenment, and instead focused on emotion, nature, and imagination. This idea spread throughout Europe with its newfound appeal to the masses, transforming grand old genres like opera, ballet, and symphonic music in ways that still move us today. Industrialization further fuelled this movement's popularity by providing much larger theaters with improved acoustics for musical performances, wider audiences to appreciate these works, and even a way to distribute them through mass media including newspapers and pamphlets. All these elements combined helped shape the period we now know as the Romantic Period- an undeniable milestone in art, literature, and music. FAQS: Q: What kind of art was popular in the Romantic Period? A: Popular art forms included ballet, opera, and symphonic music. Paintings were usually large oil on canvas works that depicted highly emotional scenes from nature or mythology. Literature focused on stories with strong emotions, heroic characters, and longing for unattainable aspirations. Poetry also became very popular with works like Lord Byron's "Childe Harold's Pilgrimage" and William Wordsworth's "Ode: Intimations of Immortality". This period also saw a rise in the popularity of novels, including Jane Austen's "Pride and Prejudice", Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein" and Victor Hugo's "Les Miserables". All these forms of art helped to define the Romantic Period. Q: How did industrialization influence the Romantic Period? A: Industrialization had a major impact on this period as it enabled larger theaters with improved acoustics for musical performances, wider audiences to appreciate these works, and even a way to distribute them through mass media including newspapers and pamphlets. This made the art forms of the Romantic Period more accessible to a larger audience and helped shape it into what we now know today. Q: What are some iconic works of art that originated during this period? A: Some of the most iconic works of art from this era include Beethoven's Symphony No. 9, William Wordsworth's "The Prelude", Caspar David Friedrich's "Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog" and Percy Bysshe Shelley's "Ode to the West Wind". All these works embody many of the themes associated with the Romantic Period such as nature, intense emotion and nostalgia.

They are all still widely appreciated today and have had a lasting impact on art history.

0 notes

Text

people of color in arthurian legend masterpost

hi! some people said it would be cool if i did this, and this is something i find interesting so. yeah! are you interested in king arthur and the knights of the round table? do you like to read about characters of color, especially in older lit? well, i hope this can be a good resource for people to get into stuff like that, especially poc/ethnic minorities who might feel uncomfortable or lonely getting into older media like arthuriana. this post is friendly to both those who prefer medieval lit and those who prefer modern stuff!

disclaimers: i am not a medievalist nor a race theorist! very much not so. i am just a 17 year old asian creature on the internet who wants to have an easy-to-reference post, if i’m not comprehensive enough please inform me. i’m going to stay closely to the matter of britain, as well, not all medieval european literature as a. this is what i’m more familiar with and b. there’s so much content and information and context to go along with it that it would really be impossible to put it all into one tumblr post. (however there’s always going to be overlap!) also, please do not treat me or any other person of color/ethnic minority as a singular all-knowing authority on anything! we’re all trying to have fun here and being made into an information machine on things, especially what is and isn’t offensive isn’t fun. with that out of the way, let’s get into it! (under cut for length!)

part i: some historical context (tw for racism and antisemitism discussion)

fair warning, i’m going to start off with some discussions of more heavier history before we talk about more fun stuff. while pre colonial racism was far more different than how it is today, there still...was racism. and it’s important to understand the social mien around nonwhite people in europe at the time these works were written.

to understand how marginalized ethnicities were written in medieval european literature, you have to understand the fact that religion, specifically catholicism, was a very important part of medieval european life. already, catholicism has violent tenets (ie, conversion as an inherent part of the church, as well as many antisemitic theologies and beliefs), but this violence worsened when an event known as the crusades happened.

the crusades were a series of religious wars started by the catholic church to ‘reclaim’ the holy land from islamic rule and to aid the byzantine empire. while i won’t go into the full history of the crusades, (some basic info here and here and here) its important to understand that they had strengthened the european view of the ’pagan’ (ie: not european christian) world as an ‘other’, a threat to christiandom that needed to be conquered and converted, for the spiritual benefit of both the convertee and the converter. these ideas of ethnoreligious superiority and conversion would permeate into the literature of the time written by european christians.

even today, the crusades are very much associated with white supremacy and modern islamophobic sentiment, with words such as ‘deus vult’ as a dogwhistle, and worship of and willingness to emulate the violence the crusaders used against the inhabitants of the holy land in tradcath spaces, so this isn’t stuff that’s all dead and in the past. crusader propaganda and the ignorance on the violence of the catholic church and the crusaders on muslim and jewish populations (as well as nonwhite christians ofc) is very harmful. arthuriana itself has a lot of links to white supremacy too-thanks to @/to-many-towered-camelot for this informative post. none of this stuff exists in a bubble.

here’s a book on catholic antisemitism, here’s a book on orientalism, here’s a book about racism in history that touches on the crusades. (to any catholic, i highly reccommend you read the first.)

with that out of the way, we can talk about the various not european groups that typically show up in arthurian literature and some historical background irt to that. the terms ‘moor’ and ‘saracen’ will typically pop up. both terms are exonyms and are very, very broad, eventually used as both a general term for muslims and as a general term for african and (western + central) asian people. they’re very vague, but when you encounter them the typical understanding you’re supposed to take away is ‘(western asian/african) foreigner’ and typically muslim/not christian as well. t

generally, african and asian lands will typically be referred to as pagan or ‘eastern/foreign’ lands, with little regard for understanding the actual religions of that area. they will also typically refer to saracens as pagans although islam is not a pagan religion. this is just a bit of a disclaimer. the term saracen itself is considered to be rather offensive-thank you to @/lesbianlanval for sending me a paper on this subject.

while i typically refer to the content on this post as having to pertain to african and asian people (ie, not european) european jewish arthurian traditions are included on this post too. but, i know more about poc and they’ll feature more prominently in this post because of that, lol.

part ii: so, are there any medieval texts involving characters of color?

i’m glad you asked! of course there are! to be clear, european medieval authors were very much aware that people of color and african + asian nations existed, don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. even the vita merlini mentions sri lanka and a set of islands that might (?) be the philippines!! for the sake of brevity though, on this list i’m not going to list every single one of these small and frequent references, so i’m just going to focus on texts that primarily (or notably) feature characters of color.

first of all, it’s important to know was the influence of cultures of color and marginalized ethnicities that helped shape arthurian legend. the cultural exchange between europe and the islamic world during the crusades, as well as the long history of arab presence in southern europe, led to the influence of arabic love poetry and concepts of love on european literature, helping to form what we consider the archetypal romance. there are also arthurian traditions in hebrew, and yiddish too, adding new cultural ideas and introducing new story elements to their literature-all of these are just as crucial to the matter of britain as any other traditions!

when it comes to nonwhite presence in the works themselves, many knights of color in arthurian legend tend to be characters that, after defeated by a knight of arthur’s court join the court themselves. though some are side characters, there are others with their own romances and stories devoted to them! many of them are portrayed as capable + good as, if not better than their counterparts. (this, however, usually only comes through conversion to christianity if the knight is not christian...yeah.) though groups of color as a general monolith created by european christians tended to be orientalized in literature (see: mystical and strange ~eastern~ lands), many individual knights were written to be seen by their medieval audience as positive heroes. i’m going to try to stick to mostly individual character portrayals such as these.

with that all said though, these characters can still be taken as offensive (i would consider most to be) in their writing, so take everything with a grain of salt here. i will also include links to as many english translations of texts as i can, as well as note which ones i think are beginner friendly to those on the fence about medieval literature!

he shows up in too many texts so let’s make this into two bullet notes and start with one of, if not the most ubiquitous knight of color of the round table (at least in medieval lit),-palamedes! palamedes/palomides is a ‘’saracen knight’’ who (typically) hails from babylon or palestine and shows up in a good amount of texts. his first appearance is in the prose tristan, and he plays a major role there as a knight who fights with tristan for the hand of iseult-while he uh. loses, him and tristan later become companions + friends with a rivalry, and palamedes later goes off to hunt the questing beast, a re-occurring trend in his story.

palamedes even got his own romance named after him (which was very popular!) and details the adventures of the fathers of the knights of the round table, pre arthur, as well as later parts of the story detailing the adventures of their sons. it was included in rustichello da pisa’s compilation of arthurian romances, which i unfortunately have not seen floating around online (or...anywhere), so i can’t attest to the quality of it or anything. he appears in le morte darthur as well, slaying the questing beast but only after his conversion to christianity (...yeah.) in the texts in which he appears, palamedes is considered to be one of the top knights of the round table, alongside tristan and lancelot, fully living up to chivalric and courtly ideals and then some. i love him dearly and i’ve read the prose tristan five times just for him. (also the prose tristan in general is good, please give it a try, especially if you’re a romance fan.)

speaking of le morte d’arthur, an egyptian knight named priamus shows up in the lucius v arthur episode on lucius’ side first, later joining arthur’s after some interactions with gawaine. palamedes has brothers here as well-safir and segwarides. safir was relatively popular, and shows up in many medieval texts, mostly alongside his older brother. i wouldn’t recommend reading le morte of all things for the characters of color though-if you really want to see what it’s all about, just skip to the parts they’re mentioned with ctrl + f, haha.

the romance of moriaen is a 12th century dutch romance from the lancelot compilation, named for its main character morien. morien, who is a black moor, is the son of sir aglovale, the brother of perceval. whilst gawaine and lancelot are searching for said perceval, they encounter morien, who is in turn searching for aglovale as he had abandoned morien’s mother way back when. i wholeheartedly recommend this text for people who might feel uncomfy with medieval lit. though the translation i’ve linked can be a bit tricky, the story is short, sweet, and easy to follow, and morien and his relationships (esp with gariet, gawaine’s brother) are all wonderful.

king artus (original hebrew text here) is a northern italian jewish arthurian text written in hebrew- it retells a bit of the typical conception of arthur story, as well as some parts from the death of arthur as well. i really can’t recommend this text enough-it’s quite short, with an easy-to-read english translation, going over episodes that are pretty familiar to any average reader while adding a lot of fun details and it’s VERY interesting to me from a cultural standpoint. i find the way how they adapt the holy grail (one of the most archetypal christian motifs ever) in particular pretty amazing. this is also a very beginner friendly text!

wolfram von eschenbach’s parzival (link to volume 1 and volume 2-this translation rhymes!) is a medieval high german romance from the early 13th century, based off de troyes’ le conte du graal while greatly expanding on the original story. it concerns parzival and his quest for the grail (with a rather unique take on it-he fails at first!), and also takes like one million detours to talk about gawaine as all arthurian lit does. the prominent character of color here is a noble mixed race knight called feirefiz, parzival’s half brother by his father, who after dueling with parzival, and figures out their familial connection, joins him on his grail quest. he eventually converts to christianity (..yeah.) to see the grail and all ends happily for him. however, this text is notable to me as it contains two named women of color-belacane, feirefiz’s black african mother, and secundilla, feirefiz’s indian wife. though unfortunately, both are pretty screwed over by the text and their respective husbands. though parzival is maybe my favorite medieval text i’ve read so far i don’t necessarily know if i’d recommend this one, because it is long, and can be confusing at times. however, i do think that when it comes to the portrayal of people of color, while quite poor by today’s standards, von eschenbach was trying his best?-of course, in reason for. a 13th century medival german christian but he treats them with respect and all these characters are actually characters. if you’re really interested in grail stories (and are aware of the more uncomfortably christian aspects of the grail story), and you like gawaine and perceval, i’d say go for it.

in the turk and sir gawain, an english poem from the early 16th century, gawaine and the titular turkish man play a game of tennis ball. i’m shitting you not. this text is pretty short, funnily absurd, and with most of the hallmarks of a typical quest (various challenges culminating in some castle being freed), so it’s an easier read. it’s unclear to me, but at the end of the story the turkish man turns into sir gromer, a noble knight, who may or may not be white which uh. consider my ‘....yeah’ typical at this point, but i don’t personally read it that way for my own sanity. also he throws the sultan (??) of the isle of man (????) into a cauldron for not being a christian so when it comes to respectful representation of poc this one doesn’t make it, but it does make this list.

the revenge of ragisel, or at least the version i’ve read (the eng translation of the dutch version from the lancelot compilation), die wrake van ragisel, starts off being about the mysterious murder of a knight, but eventually, as most stories do, becomes a varying series of adventures about gawaine and co. one of gawaine’s friends (see: a knight who he combated with for a hot sec and then became friends and allies with, as you do) is a black knight named maurus! he’s not really an mc, but he features prominently and he’s pretty entertaining, as all the characters in this are. i also recommend this highly, i was laughing the whole time reading it! it’s not too long and pretty wild, you’ll have a good romp. this is a good starter text for anyone in general!

i’ve not read the roman van walewein, which, as it says on the tin, is a 12th century dutch romance concerning some deeds of gawaine (if only gawaine was a canon poc, i wouldn’t need to make this list because he’s so popular...). i’m putting it on the list for in this, gawaine goes to the far eastern land of endi (india) and romances a princess named ysabele. i can’t speak to ysabele’s character or the respectfulness of her kingdom or representation, but i know she’s a major character and her story ends pretty well, so that’s encouraging. women of color, especially fleshed out woc, are pretty rare in arthurian lit. i’ve also heard the story itself is pretty wild, and includes a fox, which sounds pretty exciting to me!

now the next two things i’m going to mention aren’t really? texts that feature characters of color or jewish characters, but are rather more notable for being translations of existing texts into certain languages. wigalois is a german 13th century romances featuring the titular character (the son of, you guessed it, gawaine!) and his deeds. the second, jaufre, is the only arthurian romance written in occitan, and is a quite long work about the adventures of the knight jaufre, based on the knight griflet. what’s notable about these two works is that wigalois has a yiddish translation, and jaufre has a tagalog translation. wigalois’ yiddish translation in particular changed the original german text into something more fitting of the arthurian romance format as well as adding elements to make it more appealing for a jewish audience. the tagalog translation of jaufre on the other hand was not medieval, only coming about in 1900, but the philippines has had a long history of romantic tradition and verse writing, so i’m curious to see if it too adds or changes elements when it comes to the arthurian story, but i can’t find a lot on the tagalog version of jaufre unfortunately-i hope i can eventually!

this list of texts is also non-exhaustive! i’m just listing a couple of notoriety, and some to start with.

part iii: papers and academic analysis

so here’s just a dump of various papers i’ve read and collected on topics such as these-this is an inexhaustive and non-comprehensive list! if you have any papers you think are good and would like to be added here, shoot me an ask. i’ll try to include a link when i can, but if it’s unavailable to you just message me. * starred are the ones i really think people, especially white people, should at least try to read.

Swank, Kris. ‘Black in Camelot: Race and Ethnicity in Arthurian Legend’ *

Harrill, Claire. ‘Saracens and racial Otherness in Middle English * Romance’

Keita, Maghan. ‘Saracens and Black Knights’

Hoffman, Donald L. ‘Assimilating Saracens: The Aliens in Malory's ‘Morte Darthur’

Goodrich, Peter H. ‘Saracens and Islamic Alterity in Malory's ‘Le Morte Darthur’

Schultz, Annie. ‘Forbidden Love: The Arabic Influence on the Courtly Love Poetry of Medieval Europe’ *

Hardman, Philipa. ‘Dear Enemies: the Motif of the Converted Saracen and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’

Knowles, Annie. ‘Encounters of the Arabian Kind: Cultural Exchange and Identity the Tristans of Medieval France, England, and Spain’ *

Hermes, Nizar F. ‘King Arthur in the Lands of the Saracens’ *

Ayed, Wajih. ‘Somatic Figurations of the Saracen in Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur’

Herde, Christopher M. ‘A new fantasy of crusade: Sarras in the vulgate cycle.’ *

Rovang, Paul R. ‘Hebraizing Arthurian Romance: The Originality of ‘Melech Artus.’’

Rajabzdeh, Shokoofeh. ‘The Depoliticized Saracen and Muslim erasure’ *

Holbrook, Sue Ellen. ‘To the Well: Malory's Sir Palomides on Ideals of Chivalric Reputation, Male Friendship, Romantic Love, Religious Conversion—and Loyalty.’ *

Lumbley, Coral. ‘Geoffrey of Monmouth and Race’ *

Oehme, Annegret. ‘Adapting Arthur. The Transformations and Adaptations of Wirnt von Grafenberg’s Wigalois’ *

Hendrix, Erik. ‘An Unlikely Hero: The Romance of Moriaen and Racial Discursivity in the Middle Ages’ *

Darrup, Cathy C. ‘Gender, Skin Color, and the Power of Place in the Medieval Dutch Romance of Moriaen’ *

Armstrong, Dorsey. ‘Postcolonial Palomides: Malory's Saracen Knight and the Unmaking of Arthurian Community’ (note this is the only one i can’t access in its entirety)

part iv: supplemental material

here’s some other stuff i find useful to getting to know knights of color in arthurian legend, especially if papers/academic stuff/medieval literature is daunting! i’d really recommend you go through all of these if you can’t go through anything else-most are quick reads.

a magazine article on knights of color here, and this article about the yiddish translation of wigalois.

this video about characters of color in arthurian legend!

the performance of the translation of arabic in Libro del Caballero Zifar, and how it pertains to the matter of britain

a post by yours truly about women of color in parzival

this info sheet about palamedes, and this info sheet about ysabele-thanks to @/pendraegon and @/reynier for letting me use these!

this page on palamedes as well

this post with various resources on race and ethnicity in arthuriana-another thank you to @/reynier!

part v: how about modern day stories and adaptations?

there’s a lot of em out there! i’m not as familiar with modern stuff, but i will try to recommend medias i know where characters of color (including racebends!) are prominent. since i haven’t read/watched all (or truly most) of these, i can’t really speak on the quality of the representation though, so that’s your warning.

first of all, when it comes to the victorian arthurian revival, i know that william morris really liked palamedes! (don’t we all.) he features frequently in morris’ arthurian poetry, (in this beautiful book, he primarily features in ‘sir galahad, a christmas mystery’ and ‘king arthur’s tomb’. he has his own poem by morris here.)

and some other poems about palamedes, which i’d all recommend.

for movies, i know a knight in camelot (1998) stars whoopi goldberg as an original character, the green knight (2021) will star dev patel as gawaine.

some shows include camelot high, bbc merlin, disney’s once upon a time, and netflix’s cursed, all featuring both original characters of color and people of color cast as known arthurian figures.

for any music people, in ‘high noon over camelot’, an album by the mechanisms, mordred is played by ashes o’reilley, who in turn is performed by frank voss, and arthur is played by marius von raum who is perfomed by kofi young.

i’ve also heard the pendragon and the squire’s tales have palamedes as a relevant character if you’re looking for novels, as well as legendborn and the forgotten knight: a chinese warrior in king arthur’s court starring original protagonists of color!

part vi: going on from here

so, you’ve read some medieval lit, read some papers, watched some shows, and done all that. what now? well, there’s still so much out there!

if you have fanfiction, analysis, metaposts, fun content etc etc about arthurian poc, feel free to plug your content on this post! i’d be happy to boost it.

in general, if you’re a person of color or a jewish person and you’re into arthurian legend, feel free to promote your blog on this post as well! i would love to know more people active on arthurian tumblr who are nonwhite.

this is really just me asking for extra content, especially content made by poc, but that’s okay! arthurian legend is a living, breathing set of canons and i would love love love to see more fresh diversity within them right alongside the older stuff.

a very gracious thank you to the tumblr users whom i linked posts to on here, and thanks to y’all for saying you want to see this! i hope this post helped people learn some new things!

#finny.txt#arthuriana#arthurian legend#matter of britain#medieval romance#arthurian literature#arthurian mythology#<- :/#but necessary#also ITS DONE ITS DONE ITS FINALLY DONE#PLEASEREBLOG THIS WRHSFSHDFDHSFSDF#2K PLUS WORDS..

303 notes

·

View notes

Text

The lovely @curiouselfqueen tagged me on this one. (Thank you! I love these things.)

Uh. I have *feelings* about these? I have no idea why I feel so strongly, but... uh... there you go.

deep violet or blood red? Both? Not at the same time, but I love both. Purple and red are both power colors, but they convey very different things. Old ladies are allowed to wear both because they have the power to pull it off.

sunshine or moonlight? Oof. My default answer is moonlight? Some of the medication I’m on makes my eyes super-sensitive to sunlight. I’m like a damn vampire. Even on cloudy days I need sunglasses. I like seeing the sunlight through the trees when I’m in the woods? It’s pretty and far less painful.

Don’t get me wrong—I do love the moonlight. It’s so beautiful. Winter moonlight and summer moonlight are gorgeous.

80s music or 90s music? How dare you! Don’t speak to me or my 874 music genres ever again. Seriously though, I really love music. I listen to a wide variety of genres and some artists span decades. I love new wave and synthpop, but I also love pop punk and the swing revival. I can’t say one decade is better than the other.

orchids or dahlias? I like to garden, and from a gardening standpoint it’s dahlias all the way. Orchids are a wildly diverse species (over 25,000 types), but the pretty, delicate orchids they sell in stores are not hardy and require a lot of intensive, specific support. They’ll die if you plant them outside where I live. And the garden outside is what makes me happy and brings me joy.

garnet or ruby? These are such different stones. It’s almost like asking if I like chocolate milk or cola. Yes, they are both brown and you can drink them—but they’re really not similar.

Garnet— it’s semi-precious, plentiful, in use since antiquity. A decent go-to stone for jewelry. Like any gemstone, the color is determined by the type of impurities, so garnet can be almost any color. Blue garnets are the rarest. The Mohs scale for garnet depends on those same impurities because some can actually strengthen the hardness of the stone. Generally 6 to 7.5 on the Mohs scale.

I like garnets. Depending on the talent of the jeweler you can get lovely pieces set in silver that won’t cost an arm, a leg, and your soul. It was also my mother’s birthstone, so there’s that.

Ruby— Occasionally confused with spinels, rubies are pieces of corundum that contain the impurity chromium. Corundum that contains the impurities iron, titanium, vanadium, or magnesium are usually blue and referred to as sapphires. (Pink sapphires are actually poor quality rubies that the jewelry industry decided to rebrand to dupe the public. Similar to “chocolate diamonds” and other attempts to sell gems that don’t meet the criteria for their type.)

Corundum is a 9 on the Mohs scale. They highly sought after, have a rich mythos surrounding them, and feature prominently in history.

It seems like a lot of hype to me? They’re sturdy pieces of jewelry, not prone to breakage, but they ought to be for the price you pay. They’re pretty, I’ll grant you that.

moths or butterflies? Well, one is nocturnal and one is diurnal. One is fuzzy and stocky and one is smooth and slender. One is drab and one is brightly colored. I feel like I should picks moths on principle. I love Luna Moths. But butterflies are so very, very pretty. Moths I guess?

Aphrodite or Athena? Okay... so, um, here’s where it’s going to get heated. I apologize. I am *specifically* addressing how Athena and Aphrodite were worshipped/treated in Greek myths. I’m not looking at proto versions from Minoa, Mycenae, or Phoenicia. I’m also not looking at later syncretizations with other cultures e.g. Rome. It is the Greek myths that matter here because those are the myths and attitudes that were directly incorporated into Western culture. We’ve learned a lot about their origins, but *those* myths and attitudes were *not* incorporated into mainstream Western culture.

Athena was either born from Zeus’ head or his thigh. Either she has no mother—Zeus is her only parent—or Zeus swallowed her mother Metis (wisdom, prudence, counsel). This is critically important. In Athenian law, the father was the only legal parent. Mothers had no legal rights to their children at all. Athena is a very real symbol of that.

She is often portrayed as the goddess of wisdom, handicraft, and war. She is a goddess of industry (wine and olive oil). The thing we must ask is what kind of wisdom? What kind of war?

Plato argues this in Cratylus— that Athena’s wisdom could be a number of things from divine knowledge to moral intelligence. I think it’s important that Plato, one of Greece’s most celebrated philosophers, and more important one of the philosophers most embraced by Western Culture praised this choice of “moral intelligence.” [see Plato’s stance on poets in The Republic.]

Athena’s war is not the war of Ares, which is tied to passion and emotion. Ares represents the brutal aspects of war where humanity gives way to cruelty and inhumanity. Athena’s warfare is rational and “just.” Athena makes war on behalf of the city-state. Athena makes war to defend the government.

Athena’s purpose in myth and in poetry and song is to support the government. She is the shield of the king. She upholds and enforces the status quo. Look at her role in the Orestes trilogy. She supplants the Erinyes [the furies originally hunted and tormented ppl who committed matricide]. She decides that Iphigenia’s murder didn’t matter. Clytemnestra (Iphigenia’s mother) didn’t have the right to revenge for her daughter. Orestes was *justified* in murdering his mother because she killed his parent, his father.

Aphrodite also has a motherless birth, but it’s more incidental and spontaneous. Kronos cuts off his father Uranus’ genitals ( like you do ) and tosses them into the sea. Aphrodite is born from the sea foam. There’s a different feel to Aphrodite’s myth. An independence almost. Yes, a male god was involved because it’s a Greek requirement for any child, but it’s in such an incidental way. There was no purpose or intent on Uranus’ part. He had no control over her birth.

Aphrodite is an incredibly independent goddess. She owns her own sexuality and has autonomy over her own body. She is often referred to as the wife of Hephaestus, but in both the Iliad and Hesiod’s Theogony, Hephaestus has wives with different names and Aphrodite is unmarried.

A goddess with this kind of freedom and power in her own right—not tied to a husband or male family member (sorry Artemis!)— is almost unheard of. It makes Aphrodite unique and interesting.

TLDR: I prefer Aphrodite.

grapefruit or pomegranate? Pomegranate. For so many reasons, not the least of which is it’s associations with death and fertility. It’s a lovely contrast and a reminder that death brings forth life e.g. Nurse logs.

angel’s halo or devil’s horns? Oof. This is another rant, guys. Horns as a symbol of divine power are used throughout history and throughout the Indo-European culture. From Egyptian gods like Amun and Isis to Hindu gods like Śiva to Canaanite gods like El and Yahweh, horns have been used to show their power and might. Moses has most famously been depicted with horns due to murky/difficult translations of the Hebrew verb keren/qaran, which can mean BOTH “to send forth beams/rays” and “to be horned”.

There was a concerted effort to associate horns with the devil/evil/bad. Horns are also used to imply fertility/abundance, and that may have played into the perception of horns as devilish. Moses with horns was used as a jumping off point to demonize Jewish people during the Medieval period in a variety of European countries and cultures.

Halos, too, have been used across history and cultures as a symbol of divine power. Sumerian literature talks about a bright emanation that appears around gods and heroes. Chinese and Japanese Buddhist art shows Buddhist saints with halos.

I choose horns because I choose to reclaim that divine power. I reject the idea that either symbol is wholly good or wholly evil. I reject the idea that sexuality by itself is evil/wrong.

sirens or banshees? Both!!! I must admit a partiality to Sirens that is based wholly on my preference for the sea/ocean.

lorde or florence + the machine? Both!!! I love both groups and I’ve listened to their albums so many times. I will admit that I end up listening to Lorde more often when writing.

the birth of venus or the starry night? Huh. I’m going to assume that you mean the painting by Boticelli, even though there’s more than one Birth of Venus.

Honestly, Venus Anadyomene (Venus rising from the sea) is my favorite. It’s her origin myth and anyone could paint it, draw it, write about it, and put their own spin on it. It is malleable because it is myth. It lives on and changes and grows with us. Boticelli’s version is particularly lovely.

Starry Night (1889) belongs to VanGogh. No one can really recreate it without copying his style or his vision. Verschuier’s The Great Comet of 1680 Over Rotterdam could never really be confused with Starry Night. Not even Munch’s Starry Night (1893) could be confused for VanGogh. The two paintings are wildly different in subject matter despite the fact that their subject is the night sky.

I doubt any modern painter would dare. O’Keefe called hers Starlight Night, and I can only guess that others would follow that naming pattern of not quite using the title Starry Night.

Boy, I bet @curiouselfqueen is regretting tagging me now... sorry?

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The KleskizhAUs and their Poetic Styles

Under read more because lomg

SWTOR Kleskizhae

Ridiculous Sith Juggernaut. Excessively proud of his Sith ancestry but also ridiculously light side and somehow doesn’t see this as a problem. Loves lightsabers, loves the Empire but is a little less clear on whether he likes the Empire as an institution or the Empire as the people, and hint, it’s the people, he’ll pick the people if he had to.

Poetry: ALL CAPS HAIKUS FREE VERSE ASTRONOMY METAPHORS EXTREMELY VIOLENT REFERENCES TO ANCIENT SITH HISTORY BEAUTIFUL WORDS BEATEN STRAIGHT OUT OF HIS HEART OF DARK PASSION

DS!SWTOR Kleskizhae

Ridiculous and awful Sith Juggernaut. Believes himself morally and genetically superior to all others. Delights in toying with his inferiors, especially in breaking their hearts with his charm and facade of kindness.

Poetry: Flowery and romantic and flattering. More or less copies of ancient Sith poems, but with the words changed a bit. They’re mostly for showing off how cultured he is and how much he loves you babe, so he doesn’t put in much effort.

ESO Kleskizhae

Altmer Battlemage. A scion of the Direnni but not on great terms with his family due to his allegiance to the Aldmeri Dominion and his marrying a Bosmer because of Spinner shenanigans. Ambassador of the Queen and definitely not one of her Eyes nosir. Got pressganged into the Buoyant Armigers after impressing Vivec by exemplifying all of hir favorite virtues and vices just by accident.

Poetry: Sonnets. Ballads. Sexually explicit but it’s so purple that you can hardly tell just how sexually explicit it really is. Mostly about his own adventures and the people he knows. Melodramatic as fuck. The stuff he wrote when Vivec specifically was taking an interest in him is his best work, since he starts getting more experimental and tones down the silliness without losing that red hot emotional core that really elevates the verse to something that so many people try and fail to replicate in the future that it’s become its own genre.

DS!ESO Kleskizhae

Altmer Battlemage what dabbles in necromancy. Believes himself the rightful king of all of High Rock with the Bretons as his rebellious subjects. Allied with Mannimarco because he promised him that when Planemeld happened, he could have his ancestral holdings all to himself, with all the people there living only to glorify him. The kinda guy you end up killing in the Daggerfall Covenant quests or in a Balfiera focused dungeon DLC.

Poetry: Pretty similar to light side ESO!Kleskizhae, but if he thinks you didn’t appreciate his work he’ll torture you until you do. Try and critique it and he’ll just plain murder you and raise your corpse to grovel for his forgiveness and admit that you were wrong. Also his poetry is his annoying boss mechanic somehow. Didn’t read the books in his dungeon? Too bad because that’s how you defeat him.

GW2 Klejskizae

Norn Herald. Skald, champion of Wolf, Lightbringer of the Order of Whispers. A Delight unto all people of Tyria! Your new best friend who is not using your friendship with him to learn your secrets! Come and listen to him channel the spirits and the Legends next Dragon Bash!

Poetry: Actually more into prose. Veddas. Stories about heroes, exaggerated for effect. Tales that he keeps in his mind that he tells differently each time he’s asked to tell it, depending on what he thinks his audience needs to hear. The poetry tends to be more personal, often taking the form of prayers to the Spirits that are between him and them. Also will write songs, also about heroes, with calls to action for the Pact.

TES!Specifically Klejskizae

Nord Skaald. Traveling yeller. Delighter of audiences all throughout Tamriel. Follower of the Old Ways. Probably also in the Blades.

Poetry: SCREAMING TAVERN SONGS. Great heroes, sometimes gets kicked out of taverns in Skyrim because he’s performing songs about non-Nord heroes but how can you not be excited by EVERYONE

SWTOR!Specifically Klejskizae

Mandalorian what will scream battle poems in your ear as he faces you in glorious hand to hand combat. Has some very weird ideas of what being Mandalorian is, but they’re closer to reality than his Sith version’s ideas of being Sith.

Poetry: You thought Sith Kleskizhae’s poetry was gory and violent? You haven’t heard Mando Klejskizae. They are ridiculous. Everything ends with lovers embracing for the last time as they die in battle and their death is described in excruciating detail.

FFXIV Kleskizhae

Ishgardian adventurer. Dragoony Bard. Got kicked out for being way too scandalous for the theocracy and for talking too much about how he thought that maybe we should just smooch the Dragons?

Poetry: The poetry isn’t why he’s not liked back in Ishgard, though that poetry was a means to transmit his unpopular and scandalous ideas and activities. The poetry specifically is why he’s distrusted in Gridania after he met an elemental and challenged it to a rap battle and it went very poorly. (Kleskizhae won and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise or that that’s not the point and there is no winning because he definitely won)

West Coast Fallout Klaus K. Zheng

Paladin of the Brotherhood of Steel. Sort of into the whole BoS thing of keeping dangerous tech out of people’s hands but also he’s into protecting people in any way he can, since they must protect those who will inherit the past, yes? That is what we’re doing, right? Right?

Poetry: He found a book of poems about Arthurian legends and they changed his life, as did Grognak the Barbarian which he’s sure is in the same canon. He’s also read a bunch of Shakespeare and only sort of understands it. So yeah, sonnets that are Shakespeare ripoffs. Casting modern topics into medieval terms. Sometimes it’ll get weird and his BoS worldview will come in and make them anachronistic but it’s unintentional because he just wants to write like the knights of yore.

East Coast Fallout Klaus K. Zheng

Enclave soldier, later deserter once he sees that oh shit killing everyone wasn’t supposed to be what they were going to do! He wasn’t listening to the quiet part! Ends up aiding synths because it pisses off the BoS and also saves lives. Still believes in America but it’s one that maybe never existed.

Poetry: The Enclave did preserve a lot of good American literature in their databanks, though they’re kinda sketchy about distributing it to their soldiers since even before 2077 they realized that a lot of the American canon contains like, anti-war, anti-corporate ideas and they couldn’t have that in their new society. He read Leaves of Grass once and it blew his mind. He might just surrender to the Brotherhood if they let him have access to their books, because he needs those. But also he might not because they would probably kill him and he’s also spending his post-Raven Rock time helping synths out of the Institute and that’s something they’d kill him for. And probably also kill a lot of other people if they realized that the Railroad had ex-Enclave in there. And the Institute doesn’t care for the humanities, which is why they had to create machines to teach them how to be human and then proceed to do such terrible things to the humans they’ve created; because they are less machine than they are and they resent them for it.

Modern Vlogger Klaus K. Zheng

Relationship advice vlogger, specifically as a counter-voice to all those shitty misogynist PUAs that are targeting lonely straight men. Also here for the lonely women and the lonely queers since he’s a queer man himself.

Poetry: He’s got a Master’s in Poetry and he feels it was time well spent, even if he didn’t care as much for academia as he did for the writing and the reading. One of the rewards for donating to his Patreon at a higher tier is a short poem written just for you about whatever subject you wish. (Assuming that it’s not extremely objectionable. He’ll gladly write poems about all sorts of sex acts, but he won’t write one about the virtues of white power.)

HZD Kleskizhae

Carja Warrior. Participated in the Red Raids because that was what the will of the Sun was but he couldn’t take the violence and the genocide and ended up joining with Sun-Prince Avad to overthrow the murderous king literally as soon as he could. Has been on a tour of goodwill ever since.

Poetry: Overuses the words “glinting”, “scintillating”, “resplendent”, “radiant”, “brilliant” and other words that mean A LOT OF LIGHT because he’s really into writing ridiculous songs about the Sun. A lot more personal and emotional than a lot of Carja poetry, since it’s more about love than about praising the Sun or the King. It’s a new dawn, and what the world needs is love’s shining rays to heal her wounds. With the help of some Oseram who wanted to promote the newly invented phonograph, manages to become the first real pop star after the apocalypse.

DA Kleskizhae

Tevinter Battlemage. Was sent off to the front lines against the Qunari to keep from embarrassing his family and his master. Accidentally ended up embarrassing them anyway.

Poetry: So he’s really into bringing up the Old Gods in his poems. He doesn’t worship them, he’s a good Andrastian, but you know how in the Renaissance everyone was a huge Greeceaboo? Yeah, it’s like that.

WtA Klaus K. Zheng

Fianna Galliard. He’s a werewolf poet who sings ballads of his pack’s glorious battles and lifts their spirits in the name of Gaia and Stag!

Poetry: He’s got a soft spot for dirty limericks. All of the Kleskizhaes will make improv poems upon request when they’re drunk enough but Fianna!Klaus is the master of the drunken on-the-spot poem. Like they get way better when he’s drunk and they’re improvised, as opposed to the usual thing where they’re charmingly bad.

VtM Klaus K. Zheng

Toreador. Got the vampire bug some time in the Victorian era, I dunno if he was actually British or what.

Poetry: Lord Byron himself once called his poems “a bit maudlin.” His sire was certainly fond of his work, but if he had more time in his peak living creative years he would have probably been a better known figure in the Romantic movement. As it is he’s fairly irrelevant and forgotten by all but a few intense scholars of the period, and even they consider him a minor figure.

Shadowrun Klaus K. Zheng

Elven Street Samurai. Just wants to make the world a better place through the power of love and also katanas. Probably unfortunately involved with Aztechnology which is gonna end badly for him probably.

Poetry: Machines and corporations have not yet conquered the metahuman soul, and that is why he writes. Has been banned from a couple of Runner BBSs for constantly posting about his latest runs in the form of epic poem, and that’s not what these boards are for, @GLORIOUSSAMURAI, please turn off your caps lock

Star Trek Kleskizhae

Romulan Tactical Officer. Fought in the Dominion War, joined the Romulan Republic after Romulus asplode, because they wouldn’t let him quietly desert and because he believes in the true Romulan spirit that can never be repressed!

Poetry: He’s trying to revive ancient pre-Awakening Vulcan poetic traditions whilst failing to recognize that lots of it doesn’t work in the modern Romulan language. He’s always been super into poetry but after the destruction of Romulus, he becomes obsessed with writing the perfect series of poems to describe it for the future, so that people will remember what it’s like long after everyone who remembers it is dead. He hasn’t been successful yet and it’s upsetting him but he can’t just not do it. He owes it to the dead.

Bionicle Kleskizhae

He's a proud Skakdi warlord of Fire who is trying his best to unite his proud and noble people against the wicked deprivations of the Makuta and might also be in the Order of Mata Nui because sometimes Kleskizhae is a spy? But always he is very loud.

Poetry: Extremely long and elaborate war chants with 40 verses that he’s trying to get his guys to chant into battle but no one else but him can remember it all and he keeps adding more verses. But also he’s written love poetry that’s gone all the way around Greg and made romance canon again! He’s done it! With the chiseling of the tablets he’s made love real!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Academic Book Review

Reading the Anglo-Saxon Self Through the Vercelli Book by Amity Reading. New York: Peter Land, 2018. Pp. 152. $29.33.

Argument: Reading the Anglo-Saxon Self Through the Vercelli Book explores conceptions of subjectivity in Anglo-Saxon England by analyzing the contents and sources of the Vercelli Book, a tenth-century compilation of Old English religious poetry and prose. The Vercelli Book’s selection and arrangement of texts has long perplexed scholars, but this book argues that its organizational logic lies in the relationship of its texts to the performance of selfhood. Many of the poems and homilies represent subjectivity through "soul-and-body," a popular medieval literary motif that describes the soul’s physical departure from the body at death and its subsequent addresses to the body. Vercelli’s soul-and-body texts, together with its exemplary narratives of apostles and saints, construct a model of selfhood that is embodied and performative, predicated upon an interdependent relationship between the soul and the body in which the body has the potential for salvific action. The book thus theorizes an Anglo-Saxon conception of the self that challenges modern assumptions of a rigid soul/body dualism in medieval religious and literary tradition.

***Full review under the cut.***

Chapter Breakdown

Chapter One: Argues that the soul and body work together to achieve salvation (rather than being diametrically opposed). Takes Homilies IV and XII and Soul and Body I as its foci. Includes sections on embodiment, thinking vs feeling, Judgment Day, unity, agency, and salvation.

Chapter Two: Argues that the poem Andreas is about the conversion of the self rather than conversion of the Other. Contains sections on typology, baptism, eschatology, and conversion.

Chapter Three: Argues that the Ascension dramatizes the development of the religious self. Takes The Dream of the Rood and Homilies X, Xi, and XXI as its foci. Contains sections on Ascension doctrine, Rogationtide, performative piety, and unity with God.

Chapter Four: Argues that the hagiographic texts within the Vercelli Book model ideal Christian behavior. Takes Homilies XVII, XVIII, and XXIII as its foci. Contains sections on asceticism, clerical vs lay spirituality, performativity, and the purification of the Virgin.

Theories/Methodologies Used

manuscript studies (especially codicology)

source study

Reviewer Comments

Aspects of this book have been very helpful for my dissertation, so I’m perhaps a bit biased when I say that I very much enjoyed reading it. I learned a lot about the potential use and audience of the Vercelli Book from Reading’s analyses, and I was delighted to see a scholar talk about homilies and poetry together, rather than as separate components of the manuscript.

My favorite parts were the moments when she talked about soul and body discourse. Too often we tend to think of the two entities as opposing forces, so Reading’s insistence that they were both agentive and cooperative made me think of salvation and judgment in totally different ways. For example, I had the impression that the body was something to be transcended in medieval Christianity (and, in some ways, that’s still true), but this book made me rethink the body and soul at the Last Judgment in terms of ideal unity and communion.

If there are any drawbacks to Reading’s text, it would be that it’s (comparatively) short, and I would have loved to read the author’s take on some of the other texts in the Vercelli Book, such as Elene (she mentions the poem briefly, but I very much wanted to see more). If you’re not very enthusiastic about literary theory, this book might be a good fit for you, since Reading mostly uses close reading and source/manuscript studies to make her points. The lack of theory may be surprising, given that the focus is the self (and much ink has been spilled discussing that topic within philosophy and literary theory), but I don’t think it would have helped the argument at all. In fact, Reading very clearly lays out what definitions of the “self” she works with, distinguishing between the modern and medieval self, the constructed self of Christian identity, etc. - all of which I found very useful and easy to understand. Having a basic understanding of soul and body discourse (as well as understanding how baptism and salvation work in medieval Christianity) will help you get the most out of Reading’s arguments, but Reading’s points are laid out so clearly that you don’t need to be a theologian to understand the value of her analyses.

In short, I found this book thought-provoking and useful for my own work, so I would highly recommend anyone with an interest in the Christian self or salvation to engage with this text.

Recommendations: This book is useful if you’re working on

the Vercelli Book

concept of the (medieval) self and subjectivity

soul and body

eschatology

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

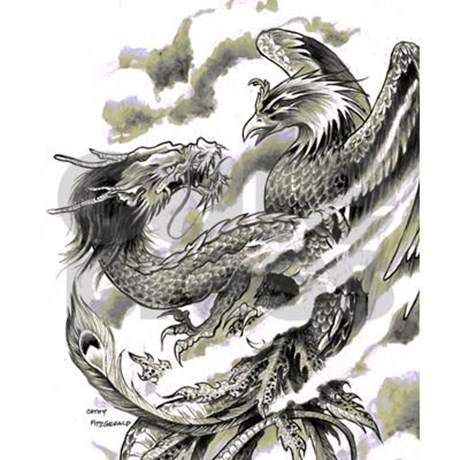

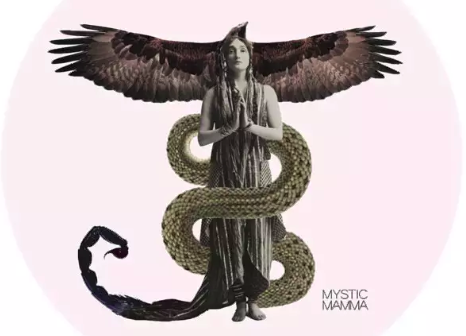

Ancient dichotomy

Eagle/Phoenix vs Serpent/Dragon: sacred vs unholy

I wanna talk about something that is central to my lore and story, and one of my favorite themes to work with: duality, in this case a very specific one.

In mythology around the world, the eagle and the snake represent the conflict of opposites. Predator and prey, interchangeable, locked in eternal dance.

They are the precursors to my whole concept of phoenix and dragon. In most cultures, eagles are seen as visionaries and messengers of the gods, while snakes represent transformation, death and rebirth (growth). This dichotomy is very commonly found in imagery around the world and mirrors my own stuff with the whole rivalry between the primeval gods, the eternal dance of the cosmos and ultimately avians and draconians.

The meaning of the battling serpent and eagle found in western imagery ties directly with the symbolism of both animals.

The eagle is a logical choice for representing a group, or the power of god. It stands for admirable, intimidating power, which is why it appears in connection with so many political entities.

The serpent represents many things, including healing, fertility, poison and medicine.. whoever in the west its often associated with evil, vengefulness and vindictiveness because of the Bible story in which the snake offers Eve the fruit from the forbidden tree, “the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.”

However, as we’ll see next, the relation between both entities isn't fixed.

Egyptian falcon and snake:

Serpents weren't regarded as symbols of evil in Ancient Egypt, however, there’s still some animosity between the falcon god Horus and them.

Seth, the enemy of Horus is sometimes refereed as “the serpent”. Horus role as the opponent of Seth is assumed as the most sacred bird of the Egyptians, the falcon, attacking Seth whom takes refuge in a hole in the ground, like a snake. However they’re shown to cooperate at times and the primeval antagonism is clouded by the joining of Nekhebet the vulture goddess of upper Egypt and the Wadjet serpent of lower Egypt on royal diadems.

During the late period when Horus became a popular god he was sometimes represented as a naked child standing above a crocodile holding in his hands snakes, scorpions and lions. Therefore Horus became known as an entity that interceded to heal and soothe snake bites and scorpion stings.

Even more interesting is the role of the primordial Egyptian serpent, Apep:

Ra was the solar deity, bringer of light, and thus the upholder of Ma'at. Apep was viewed as the greatest enemy of Ra, and so was given the title Enemy of Ra, and also "the Lord of Chaos". In later Egyptian dynastic times, Ra was merged with the god Horus, he was associated with the falcon or hawk.

As the personification of all that was evil, Apep was seen as a giant snake or serpent leading to such titles as Serpent from the Nile and Evil Lizard.

The Roman eagle also eats snakes:

Eagles killing snakes were popular subjects in Roman art. The sculpture was probably chosen to please the god Jupiter and depict the triumph of good over death and evil, but it was also a way for wealthy families to show off and commemorate their deceased loved ones.

Some other classical examples:

Mosaic floor from the Imperial Palace in Constantinople, showing eagle and serpent in battle:

A Homeric omen: A Greek wine cup with a scene of an eagle battling a snake. Homer’s description of a high-flying bird carrying a snake in its talons was an omen the Trojans saw as they attacked the Greek forces. Homer's snake was still alive and was dropped by the eagle before it could be eaten.

In the Persian mythology we have the Zahhāk (Avestan word for "serpent" or "dragon."), generally an evil figure, sometimes seen as enemy of the Simurgh (phoenix), adopted from a common source of cosmological knowledge.

The founding of Tenochtitlan, Mexico City:

The Mexican emblem shows an eagle devouring a serpent, which actually is in conflict with Mesoamerican belief. The original meanings of the symbols were different in numerous aspects, being the eagle a representation of the sun god Huitzilopochtli, who was very important to the ‘people of the sun’; and the snake a symbol of wisdom, with strong connotations to the god Quetzalcoatl.

The story of the eagle and snake was derived from an incorrect translation in which "the snake hisses", was mistranslated as "the snake is torn". Based on this error, the legend was misinterpreted and as a result the eagle represents all that is good and right, while the snake represents evil and sin, being used as an element of evangelism by the first missionaries to convert native people, as it conformed with European heraldic tradition and Christian lore.

Zodiac:

The eagle and the serpent are both variant symbols for the astrological sign of Scorpio, whose basic level, that of the scorpion was depicted by the ancient zodiac as the serpent. Both are poisonous creatures that hide under rocks, always ready to attack, representing negativity and resentment, yet strongly related to initiation into the sacred mysteries.

The eagle is another, higher level of the sign, regarding strength and wisdom, incidentally, the highest level is the phoenix, a ‘transformed eagle’ whom soared as a higher expression of the nature of this sign: transcendence from the crawling scorpion/snake to the soaring eagle/phoenix, tying together the theme of destruction and renewal.

Garuda and Nagas:

Now, going back a bit in time... The great nemesis of the nagas in the Mahabharata is the gigantic eagle-king Garuda.

According to Hindu and Buddhist stories, the giant, birdlike Garuda spends eternity killing snakelike Nagas. The feud started when both Garuda's mother and the Nagas' mother married the same husband. The husband then gave each wife one wish. The Nagas' mother asked for a thousand children. Garuda's mother wished for just two children who were superior to all of the Nagas. Their rivalry continued until Garuda's mother lost a bet and became the servant and prisoner of the Nagas' mother. Garuda was able to free his mother by stealing the nectar of immortality from the gods. But he swore vengeance for his mother's treatment and has been fighting Nagas ever since.

The Japanese version of the myth, called Karura, is said to be enormous, fire-breathing, and to feed on dragons/serpents, just as Garuda is the bane of Nagas. Only a dragon who possesses a special talisman, or one who has converted to the Buddhist teaching, can escape unharmed from the Karura.

Once more we witness the eternal rivalry between the eagle and the serpent.

Allegorical conclusion of the Christological cycle. The bird and the snake:

Early Christian writers used the phoenix bird as a symbol not only of resurrection in general but also of Christ himself. Here is an example of the Incarnation or a symbolic portrait of Christ overcoming the devil, depicted allegorically in the form of a bird fighting a serpent.

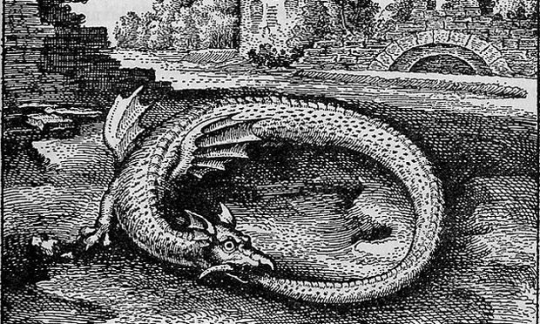

The Dragon:

As we've been able to witness, the serpent symbol is decidedly more ambiguous than the eagle, so I’d like to focus a bit on it:

With a few allegories one is able to establish the dragon as an entity derived from the snake, and the phoenix as an entity derived from the eagle. Now, going from the root symbol of serpent to its representation as the dragon:

A serpent and a dragon are often interchangeable in some proses, including the Bible and Old Norse poetry. The poem Beowulf describes a dragon also as wyrm (worm, or serpent) indicating a snake-like form and movement rather than with a lizard-like or dinosaur-like body. In the Far East, few distinctions are made between them.

Having established the dragon as the synonym of serpent, with similar meaning in the duality theme I’m working here... its noteworthy that the dragon usually carries negative connotations, especially in its more popular form, just as the phoenix usually carries positive connotations.

The medieval dragon. In medieval symbolism, dragons were often symbolic of apostasy and treachery, but also of anger and envy, and eventfully symbolized great calamity. Several heads were symbolic of decadence and oppression, and also of heresy. An evil dragon is often associated with a great hero who tries to slay it.

But dragons aren't always related to evil in traditional representation, just as their prototype, the serpent. In some countries, it was said a good dragon would give wise advice to those who seek it.

In ancient Greece, the snake figure was associated with Asclepios, the god of medicine, and possessed benevolent properties, believed to be able to cure a patient or a wounded person just by touch.

Also, a serpent biting its tail symbolized eternity and the soul of the world, being sometimes described as part dragon.. it surrounds the world. The alchemical symbol of the Ouroborus often carries positive connotations.

Fenghuang and Dragon, a more balanced view:

The fenghuang is a mythological bird of East Asia that reign over all other birds. The males were originally called feng and the females huang but such a distinction of gender is often no longer made and they are blurred into a single feminine entity so that the bird can be paired with the Chinese dragon, which is traditionally deemed male.

Fenghuang ,the "Sovereign of Birds" came to symbolize the empress when paired with a dragon as a dragon represented the emperor.

In ancient and modern Chinese culture, the fenghuang can often be found in the decorations for weddings or royalty, along with dragons. This is because the Chinese considered the dragon and phoenix symbolic of blissful relations between husband and wife, another common yang and yin metaphor.

Ancient & modern interpretations

Looking back its easy to see why those two archetypal symbols carry such antagonist interpretations... the eagle is easily a ‘good animal’. The eagle does not impact negatively human life (or it rarely does), quite the contrary. Birds of prey, including eagles, have been trained and used to our benefit, serving as companions and valuable hunting assets during our early history.

The eagle obviously has an impressive figure, and its always sky high.. human’s natural curiosity to see more of the world and have freedom has led us to naturally admire and envy animals able to fly. They are often carrying spiritual/divine connotations, on top of that, we’re both diurnal animals. An eagle is often seen or glimpsed under situations that are ‘positive’ to our primeval brains: its visage is often accompanied of imagery of large, open spaces, bright blue skies and sunlight, more or less comfortable scenarios that inspire feelings of freedom, awe and perhaps even religious reverence.

The soaring eagle rises above earthly limitations.

The serpent otherwise carries strong negative connotation to primitive humans, it is visually connected with the underworld and darker places, the unknown, the unseen... not only because it crawls on the ground, but because it can bring death, its easily a dangerous creature and its rather easy to see why it served as inspiration to so many mythological creatures as it inspired a lot of fear in our ancestors. Its almost like a primeval fear, imprinted in our brains...

However, as the lines between light and darkness become blurred and the definitions of symbolism gains new interpretations in our modern era, the ancient meanings still carry a lot of weight, still... in the recent history, the eagle, a supreme symbol of divine light has gained a certain negative connotation: imperialism and supremacy: claws grasping for power, wings outstretched, its shadow covering the world... while its counterpart, the serpent, has also emerged from the underworld and has been adopted as the symbol of the modern medical profession and the image of these animals has strongly improved with the knowledge of biology and of their nature.

Converging meaning

The eagle and the snake are some of the symbols with the strongest presence in the history of mankind. Separately they have their presence widespread, while together we have a more interesting conflict.

In the modern view of most myths, these two symbols clearly express fundamental opposites: height/depth, heaven/earth, etc... however it wasn't always the case, and sometimes these symbols cooperate, or act as halves of the same whole. Specially regarding the serpent half, if you dig just a little its easy to start finding more sensible or sympathetic incarnations of this animal through the world mythology, with more benign variations such as the eastern dragon. It becomes clear that the dichotomy isn't so simple as ‘life against death’ or ‘good against evil’.

Together they are a pair of opposites: the soaring and the creeping.

I think that, concerning those aspects.. the far eastern mythologies offer the best incarnation of the primeval duo or eagle and serpent, the phoenix and the dragon.

I want to work my phoenixes and dragons for something in between, they’re capable of great destruction as much as they’re capable of great good.

The Eagle and the Serpent as One Entity

In my world, the phoenix and dragon have superficial and deep meanings. Its easy to overlook their more common representation as opposites, and delegate the phoenix with positive meaning while the dragon is surrounded by negative energy, and its easy to simply do the opposite.. I mean to find a balance between the two.

When the eagle and serpent are perfectly paired as opposites, and equals... as phoenix and dragon, the superlative form of these creatures... they represent not victory and defeat, not light and darkness nor good and evil, but dynamic cosmic completion, the union of spirit and matter, as shown in the common emblem of their cosmic dance:

United they are stronger, they are whole. This is the force that drives the universe as the celestial bird and the serpent wheel around each other forever, in perfect balance of opposite energies, or ideally it should be like this..

It is such an interesting and very ancient symbol.. like yin yang..or the masculine and the feminine.. it shows two powerful people combining forces to create something very dynamic or shape shifting.. being able to shape a new reality..

It’s left for the characters to find common ground and forge a better future.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

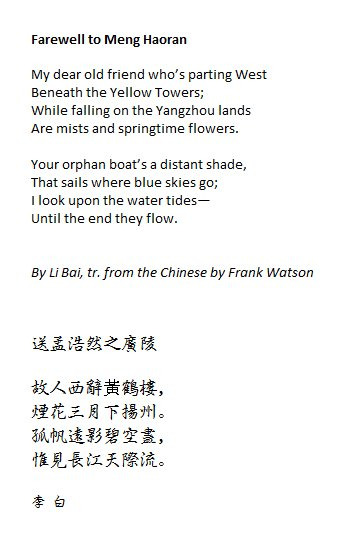

Poetry to know the world history and cultures

Poetry through time has served to know the world and others. Poetry gives us a route to discover millions of worlds in which we can engage ourselves and explore universes, that is what makes poetry a great way to enjoy the details of life that sometimes go unnoticed. Poetry also serves to know the history of a town. Thanks to the epic poems of the ancient civilizations, for example, we can come to understand how they lived and how they faced fundamental aspects of life such as education or the art of war.

Thus, in this analysis, we will talk a bit about poetry as a means to discover the history, culture, and the world.

Poetry through time from different cultures

Old age

During the old age period, in Greece, some authors were writing epic poetry. Epic poetry is the narration of feats of historical or legendary heroes, it started being oral and sung, and it’s written in verse and using slow and majestic versification. Epic poetry generally tells the exploits of a hero based on the tradition of a people. One of its pioneers is Homer with his most outstanding works the Iliad and the Odyssey, these tell the story of the legendary Trojan war.

In these two poems, Greek society and social reality are reflected at a certain point. As for the political structure, Homeric poetry gathers it well referring to the Mycenaean period, where there is a Palatial civilization whose visible head is the King, surrounded by a Nobility named by him with a reversible character and a complex bureaucratic apparatus. As for the social organization of the Mycenaean world, we can see it clearly in the Homeric poems, and it is centered on the family cultivation unit.

In the East, during the 8th century AD, poets Li Bai and Du Fu were considered the greatest national poets in China in times of the Tang dynasty. At that time, both Chinese and Japanese made impressive poetic anthologies. Here is a poem by Li Bai:

“His verses bring us closer to a real human being, with a strong temperament, very sensitive and very cordial. The energies that run through his lines, concise and imaginative, transmit warmth, sincerity, enthusiasm and life. This is how its diffusion in different environments is explained by culture, space or time.” Dañino Ribatto*

*Writer, translator, recognized among the main foreign actors in Chinese cinema.

During this time in India, the Hindus made their great epic works, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, it is considered as their most important national poems, to the point that, today, India is called Bharat in its own language. According to Gabriel Mondragon this last book is the most extensive poem in the world, with around one hundred thousand paired verses, and its name means great weight, because, according to tradition, it weighed more on a scale than the four Vedas, the religious books of India, written also in verse.

Middle Age

According to Britannia, in Europe, during the Middle Ages, the so-called minstrels or troubadours were very popular, they walked through the towns and cities singing the deeds of their great warriors and their kings, and who came to create the true collective memory of their towns at a time when most people were uneducated. Parallel to them, there was another form of poetic and moral creation, cultivated in the religious fields and monastic schools, known as the master of the clergy, and which was essential to give form and structure to the mystical and religious poetry of later centuries.

Here is a poem that was written in Old English, and the meaning. An extract taken from the web page Interesting Literature:

Somer is y-comen in

Sing cuckóu, nou! Sing cuckóu! Sing cuckóu! Sing cuckóu nou!

Somer is y-comen in, Loudë sing, cuckóu! Growëth sed and blowëth med And springth the wodë nou Sing cuckóu!

Ewë bletëth after lamb, Lowth after cálve cóu; Bullok stertëth, bukkë vertëth, Merye sing, cuckóu!

Cuckóu, cuckóu, Wél singést thou, cuckóu, Ne swik thou never nou!

“Somer is y-comen in” i.e. ‘Summer has come in’ it is a medieval poem about the summer, designed to be sung as a "round" with several people. The poet pleads with the cuckoo (bird) to sing aloud as the seed grows and the meadows flourish, and the wood now turns into leaf. The ewe bleats after the lamb, the cow after the calf, the bullock leaps, and the buck cavorts.

In the East, in India the bhajan or kirtan was spread, a Hindu devotional song. Bhajans are often simple songs in lyrical language that express emotions of the love for the Divine. Here is a poem that was written by Kabir, he was a 15th/16th century devotional poet, and social critic from northern India.

Modern Age

These forms evolved to give birth to European lyrical poetry from pre-Renaissance times, which reached its peak in the work of poets such as Dante and Petrarch. Later, during the sixteenth century in Spain there would be a resurgence of cultured literature around classical themes, in what came to be called the Spanish Golden Age, where the great figures of Hispanic letters of the time shone, Quevedo, Lope de Vega, Calderón de la Barca, Góngora and Argote, among many others, without forgetting, of course, the magnificent Cervantes.

The Chains of Love

Some made links and chains; and some made chains from love!

For there’s steel forged and bent, and true love to find or invent!

Some made coins from the best metal! And some made chains from love!

Miguel de Cervantes

English translation by Paul Archer of Bien haya quien hizo cadenas.

As we can see in this poem, the author transmits a certain state of mind. Lyric poetry is usually characterized by introspection and the expression of feelings. Most of the lyric poems are characterized by their brevity, it is not often that they exceed one hundred verses.