#but this??? wildly and poignantly different

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I just. idk. something about Steph getting along best/closest to Jason and Damian out of everybody... like I have no clue how much canon basis that's actually got but I can't stop thinking about it. yeah, yeah, the Dead Robin's Club, we've all seen it, but also — they're the outcasts. the ones who forged their own paths, the ones who question if they're really wanted at all. they have the most fundamental disagreements with Bruce/Batman, based in numerous unfortunate uncontrollable circumstances. Stephanie Brown is an outlier and shoudl not have been counted. she forced her way in and died on the way out — middle point between Tim and Jason. she isn't part of the family the way anyone else is and her one tie to them (dating Tim) is a thing of the past but she still sticks around with the excuse of the nightlife because if she didn't what would she have to call family. her situation with her mom is complicated but at least she HAS a mom, yknow? and that's a point of connection with Damian, because his relationship with Talia is complicated and complex and fraught as well. so she gets it. she gets Damian and she gets Jason because she understands where he comes from and why he believes the way he does and can just accept it and move on. maybe she believes in capital punishment, too, just a little (maybe it would be easier if her father just died). her place in the family is so fragile and she almost wishes she didn't have one at all, she's so at odds with Bruce so often, the whole thing with Tim is a mess, STEPH HERSELF is a mess. but she has the most connection with Damian and Jason because they feel that way too. they've burned bridges and, to varying degrees, repaired them too. they've all died and come back. the three of them have a unique understanding of each other that the rest of the fam maybe can never quite understand. that's why I can't stop thinking about it.

#like... in n52 canon jason and tim see themselves and each other as outsiders in the family yes. I'm obsessed with that.#but this??? wildly and poignantly different#idk I'm just stuck on that one AU run (i think they call them elseworlds?) with the zombie apocalypse whatnot#(i know i know I'm Predictable)#bc damian takes up the batman cowl doesn't he? and steph steps in as his robin??#like I've gotten the impression that they're REALLY close in that au#like... maybe. maybe just maybe... all steph really wants is to be included#so she pushes her way into things before anyone can say no the same way jay burns his bridges before anyone can do it first#FASCINATED by these dynamics. dead robins club my beloved....#Lu rambles#meta finding tag#batfam#steph brown#damian wayne#jason todd

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

fan the flames and face the fire (all these sparks make me a liar)

Some glass is crystal clear, with all the world behind it to behold. This glass sends color ricocheting off the walls, brings light where there was none and makes the world look brighter, more valuable than it was before. It makes the world look worth exploring, worth loving. Worth being vulnerable for.

They’re both glass. Just glass, right?

Felix was used to the feeling of eyes on his skin like judgement, like insects or shame crawling up his spine. It was easy to ignore; years of practice made shedding stares like shedding a coat after stepping indoors.

Hanging out with Marinette made his nerves tingle, every curious glance like a spark waiting to set him alight. He itched, squirmed under the attention, didn’t know how she could bear it so poignantly. It took him two months to ask. By the time she responded, head tilted cutely, bangs falling into her eyes, he wished he’d never even thought of the question.

“What stares?”

She didn’t even notice! Marinette had spent her whole life existing in a circle everyone wished they could be a part of, for good or for evil, curious and conniving and hopeful and horrible and everything in between, and she had no idea. Being in the middle of a hurricane that he had spent five years caught in the winds of was surreal. It was like floating on the same clouds that had left him drenched and drowned for so long.

Marinette handed out pieces of herself so casually, as if this information wasn’t unbelievably precious, as if they were scraps of paper like notes dropped onto his desk instead of gifts of gold he hoarded like a dragon, as if Felix didn’t desperately want to make up for the last five years of distance. I like to sew, she mentioned, I want to be a fashion designer. Do you want to see my sketches? Baking is stress relief for me, she explained when her parents dropped off the mini cinnamon buns she’d made in the shape of little cats. I don’t like to bring them to school myself though because I’m either confident or clumsy, and I haven’t figured out how to choose yet. She brought him notes when he was sick, because catching up when Chloe got me wrongfully suspended was so hard, and even when it was overturned the teachers didn’t offer much time for recovery. She was astonishingly good at science and never learned how to subtract; she liked to quilt and cross stitch but she knew how to bind her own books too, because reading on the screen gave her a headache.

Felix learned all of these things like they didn’t matter, like the way that she hummed off key under her breath and the way that she swung her arms in time to his footsteps when they walked together wasn’t important, wasn’t as essential to Felix’s life as his own breath, his own heart.

Felix grew up without friends. By choice, by necessity, by whatever he chose to label it: but now he was here, and he wanted everything. This being friends thing was so… was so intense, with the way his heart pounded in his chest and his words disappeared with one glance of her playful blue eyes. Felix had never felt so flustered in his life, like he was always a step behind her, like every time he managed to catch up she disarmed and sent him reeling long enough to race forward again.

Felix had spent so long learning how to be a good boy, a mature boy. A young adult confident in his skin. Being around Marinette meant learning how to be messy, wild and spiraling out of his body, taking up space and throwing words against a wall to see what sticks.

Marinette made him feel like it was okay to do that.

Marinette made him feel like he was good when he did.

It’ll be the first year they’ll take the bus to camp together, really together, the way they should’ve at age seven. Felix is bouncing in his seat, clenching his fists over air when he can’t find anything to grab, to hold onto or tear at. He’s clutching at the windowsill waiting for her signature ponytail to bounce into sight.

She does, and his pulse races. Her tank top stretches over her shoulders, rides up against her stomach, and Felix nearly topples out of his seat. She’s here!!

Immediately, two campers rush to grab her wrists, already pulling at her. Felix remembers them from last year, so scared to be away from home for the first time, and it looks like they remember her well. Another child is crying quietly, and Marinette makes her way over, kneels until she’s at their level.

“Hey there, little bird!” She tugs at their t-shirt, hanging loosely off of their shoulder. A cartoon bird is ironed onto the pocket, and Marinette pokes at it gently. The child hiccups a laugh through tears, and Marinette scoops them up into the air. “Gonna fly away from me, little bird?” They laugh and kick until Marinette pulls them into her chest, where they bury their face into her neck.

“No!! I’m gonna stay here with you!!!” Suddenly shy, they peek up at her. “If… if that’s okay?”

“Well gosh! I can’t imagine being anywhere else.” When Marinette winks, Felix sees their shoulders relax, draining of tension. They snuggle into her, and he knows she’ll be spending the bus ride in the back with the youngest campers. Something like disappointment and pride curls up in his stomach, a cat making its home by the hearth.

Marinette waves at him as she passes and another camper, nine years old and too hyper for their own good, throws themselves at Felix. He catches them, and grins at Marinette. His smile is crooked and the child is already yanking Felix’s shirt out of place.

She takes a picture, and Felix grins harder.

Being at camp as the eldest campers is a wildly new experience. Nino has taken over the guitar laying haphazardly by the fire pit, and there are always camp songs drifting across the fields now. His wrist is decorated with friendship bracelets from all the kids he sings with. Felix and Marinette have matching ones and Nino likes to tease Felix about them being the only pop of color on his otherwise grey palette. Being friends with Nino is new and thrilling too, inside jokes and playful ribbing that makes Felix grin. Marinette has admitted she likes watching the two of them interact, and Felix makes an effort to do it more often just for that. He spends time with Nino even when she’s not there, though, and it’s nice to have another friend, no matter how much it doesn’t feel the same as being friends with Marinette.

Camp looks the same and different now. There are so many people they already know, who are still finding all the best spots in the forest to hide in, the best trees to climb to see all the way out to the waterfalls just ahead of camp, the best foods from the great hall and the best ways to roast marshmallows over a campfire to get that perfect char, that melted inside.

Every now and then, Marinette smirks at a particularly perfect marshmallow and then glances at Felix. He refuses to ask until almost six weeks later, she adds a little shimmy of her shoulders and an eyebrow wiggle, and then he folds like a bad hand at poker.

“Okay, fine, what is it?!”

“...they’re like youuu!” She does it again, and this time her shimmy leans her into his space. Felix holds himself still and hopes the light of the fire covers his blush.

“How?!”

“Grumpy on the outside and melted in the middle!!” Her voice is sing-songing and Felix refuses to acknowledge exactly how melty being around her makes him feel.

“...you’re just as melty, okay.” His voice is gruff and he’s worried as soon as he says it that she doesn’t want his friendship in that same consuming kind of way, that she’ll laugh and prove him wrong. Instead, she stays quiet for a long moment that sends Felix into a whole new kind of panic and then responds, almost too quiet to be heard over the crackling of the fire.

“...I really am.”

Felix is suddenly overwhelmed with the way that she says it, like there are so many levels to what she’s saying that he can’t possibly burrow through them all.

“I-- Marinette, I’m so lu-- lucky to be your friend. I know that I could’ve had yo-- uh, could’ve been your friend years ago, and it’s my fau-- my fault, but I have you now and I’m… lucky, thank you.”

“...I’ve never heard you stutter like that.”

Shame flushes through his body.

“I’m sorry. I’m so-- I’m sorry, Marinette, I’ll stop.”

“I kind of like it.” She isn’t looking at him. Her voice cuts through to his heart anyways. It pulls at him, yanks his response out of him before he has a chance to grab it back, pull it into himself and tear it apart.

“Why?!”

“I like it when you fall apart like that. I feel like… I feel like I get to know you more than the polished perfect boy you used to pretend to be, like I get to see the way you think as it happens. It makes me feel trusted, and I just… I really value that, Felix. I know how special it is.” She watches the campfire spit flames at her marshmallow and turns it idly, following the glittering trail of sparks across the skyline, then peeks at him between her bangs.

“I know how special you are. I’m pretty lucky, too.”

#Notte Writes#Fanfiction#Miraculous Ladybug Fanfiction#ML#Miraculous Ladybug#Miraculous: Adventures of Ladybug and Chat Noir#Felix#PV Felix#Felix Agreste#Marinette Dupain-Cheng#Nino Lahiffe#Felix/Marinette#Felinette#Slow Burn#Making Friends#Having Crushes#Not Quite The Same#Fluff#Angst#Campfire#Felix Month 2020 Prompt 11#Felix Month 2020

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

PART 1 of 4(?): LUCIFER ON THEURGY AND HOLIES, NARRATIVE STRUCTURE THERE.

Bullet pointed thing not separating out good and bad stuff because most of the bad stuff is just like, failures to follow through on good stuff? Or weird arm-twists when the good stuff starts implying things a little too numinous and rebellious to the worldbuilding order and gets forcibly reined in?

Incapable of organizing my thoughts properly even though I tried so I’m just going to post all my thoughts and semi-arbitrarily break them apart into sections, I’ll probably come back to add links to the other parts later:

(I broke this in half lol becuz is was seriously too long but anyway part 2 which is more holies stuff is here)

Bullet 1. Fuck, theurgy is so good. Like the concept, the entire idea of it. Just fuck that is so good. *Much better explanation of wtf it is in this meta post.*

But it’s especially good as like a gateway to interactions or concepts too complex or liminal or interactive or emergent to be captured in anything like ‘a normal physical object’ — and it makes for a really really great process from the point of view of the characters doing it (or in Tamar’s and Eliya’s cases, interacting with someone else’s for the first time.)

The hint comes percolating through, slowly, inexplicitly, (or maybe it’s just because I read that meta post I linked first? I’m not 100% sure) — the whole world is made by this. Infinite recursion of souls.

1.a Yet it’s........actually pretty shallow simply from explanation of what it is, almost new-age-y vibes that really do it a disservice, and even more an underwhelming disservice when characters are being told how to do it. This is abrahamic fantasy! No embodied and tangible rituals? No songs and chants, no mysterious properties of specific things, which would have an extra layer of meaning because all things are souls? Eliya comes up with, in total (but forcibly unacknowledged) defiance of Lucifer, spoken-word ritual type things towards the end that DO help her, powerfully so. But so much of the book’s discussion of it seems almost designed to make it sound....lame. Thank G-d for Yenatru’s early-on pov of doing his own theurgy or I would have disliked it a lot, and thanks even more to that meta post I linked.

1.b It’s just…..weird and a bit of an um, self-own, that learning about theurgy was done through the characters literally just fucking…..being taught to about theurgy. As if this was a non-fiction book! Instead of a fiction book, a fantasy one no less, where information-communication is inherently always done differently. Why not have Eliya learn theurgy by subjecting her to various theurgies, manifestations of various people, sending her on a hunt for manifestations and making her have to try to figure them out or understand what this meant until finally she understands enough to ask questions? Why not have various elaborate rituals for theurgy?

BULLET 2. Lucifer is…………!!!$$%%???&&**???>. I loathed Lucifer as a constructed character, an execution of a part of a full narrative story. Absolutely hated them. Could not stop thinking about how much I hated them, how bad it was, all the ways the execution of them completely fails and takes out huge amounts of the overall book — character arcs, concepts, worldbuilding, resonant emotions — with them in the blast radius of the author utter failure at executing them.

And yet, Lucifer’s CONCEPT is………..amazing, their BACKSTORY is phenomenal. Absolutely incredibly original and drop-dead clever and woven into the worldbuilding in a way where dozens of tiny details about them, about theurgy, about G-d, about angels, etc, all line up to collide and open in the reveal *perfectly*. On the other hand, they are absolutely loathsome as a person. But this isn’t the problem. In fact it’s awesome. It’s not a problem on the front hand of it, at all, that they are so so so awful, as a person. It fits. This is what trauma does. Tells a truth, but then that truth metastasizes into a demanding cancer covering the world.

2.a (In this book, Lucifer’s (incredibly sympathetic) fall is very, very far from either the traditionalist folk depiction (ewwww rebellion against the wise and good laws of Heaven) OR the now-ubiquitous folk resistant reading (oooooh rebellion against the unjust and oppressive laws of heaven!) Their rebellion is instead basically a rejection of The Way Angels Are Naturally Existing, which is entangled with G-d’s soul in a lawless chaotic orgasmic orgy of unchecked creation that has the pitiless one-way un-budging This Is What Is simple Being-ness of nature and the universe. And it makes so so much sense, that in the intensity of traumatized backlash to this, Lucifer is not simply wise in the ways of ethical demands for justice from G-d and the world the way (I think) Lilith is, but is instead cruelly, reductionistly, circumscribingly dogmatic. They are many other bad things — projecting, saneist, insincere, avoidant, glib, safety-fetishizing, lacking in the tiniest budge of character development, but all these mostly go back to being dogmatic.)

None of which, again, I emphasize again, is anything except BRILLIANT and perfect from a characterization perspective. All of these things fit their character conception and trauma backstory perfectly. The issue is really that not a single one of these things are unearthed or bounced off of as the bad things they are. By which I REALLY don’t mean ‘ugh why didn’t any of the characters explicitly Call Them Out [tell not show] for how awful they are while they’re just minding their own business being awful [shown not told] as a character in this story’. I hate that kind of thing. I mean simply….the other characters’ personalities, natural reactions, and in fact the entire world around Lucifer, warps wildly in order for their creepy narrowing way of steamrollering and falsely-restating-using-‘it’s just my issue’ to be enshrined and stated [telling not showing] as Correct and somehow The Way and The Truth, the Reason Yenatru is happy now, the Reason Eliya succeeded at theurgy. When there’s not a single way this actually tracks.

2.b Why does Yenatru care about this person when everything they say would be horribly devastatingly harmful to Yenatru if its content was aimed at a slightly different category of people, but happens to not be harmful to him simply because this person happens to understand him specifically? Not the tiniest bit of supporting evidence why. There’s a tiny moment, where Lucifer challenges Yenatru to challenge them, in a way where I would almost claim that Lucifer was hoping Yenatru would challenge them and argue back against them, and continue to argue against them throughout the book because Yenatru is one of the few people who could do this without deeply triggering Lucifer’s trauma. But it never ever happens. It’s also not acknowledged but sadly refused along with their friendship later on, as it also could have been. It’s devastatingly disappointing and brought my liking of Yenatru, which was so so promising and deep because he in many scenes and aspects is written so well, down many notches.

2.c Why does Eliya successfully uncritically learn anything from them? Why does she [telling not showing] credit Lucifer with anything she learned, when she very very clearly [showing not telling] actually learned everything about herself and about theurgy’s weight and truth from Yenatru and from Tamar? It shatters the imagination to think that any of what Lucifer told her would not be grade-schooler basic knowledge for a lifelong resident of this non-portal-fantasy world, unless theurgy was a Secret Misunderstood Forgotten Art (which it very explicitly and clearly is not). I could see the information Lucifer gave her as perhaps so basic that it could easily fade into the background as not really Meaning anything or being graspable — which is exactly where Yenatru and Tamar, as an unusually gifted and deeply expressive theurgist, and an unusually extreme soul-appreciator and lover, respectively, come in!!!!

2.d And also it could have been where Lucifer’s rigid, trauma-calcified, dogma could have very expressively and poignantly come in too, as something that purports to be about How Souls Are and is illuminating by dint of how hyper-specific and inapplicable to most other people it is, how it’s actually not what souls are, but is very much what a traumatizing but successful struggle to Not Be Steamrollered Into Something You’re Not is. This would have been intensely sympathetic even. And speaking of, here’s the thing: I would have liked Lucifer a thousand times better if they [as a person] had been openly *worse.* If they were outspoken and explicit about their horrible ideas, and if the book [as a narrative] had let them be a mess incapable of intentionally teaching anyone functionally (and therefore much more poignant and illuminating-of-theurgy just by existing as an example of a person, an example that changed the world). Instead of them smoothly tucking their prescriptive ideas into the stretches between other unrelated scenes of ‘oh this is just my issue, these are my own weird biases’. They would be far better if they weren’t being twisted into having the narrative state [tell not show] like they were right about everything.

Bullet 3 It’s this — that’s what I mean. Insincere and politely erasing nonviolent-communication (a specific thing I have encountered a hundred time, more damagingly than any blatant articulated disgust and hatred I have ever encountered) -- with repeated statements of ‘no it’s okay to be you :)’ ‘i don’t think you’re immoral :)’ ‘everyone is different :)’ despite everything they say belying this. Which when placed alongside everything Lucifer says when not being confronted, does not ever function as a genuine ‘don’t listen to my biases’, but instead functions as a way to avoid actually stating (and therefore baring up to an argument) any of the erasing assumptions underlying their authoritative explanations of other things, so that those assumptions sneak through undetected when they would be interrogated and valuable if they were stated.

3.a. For example, if Lucifer’s [obvious to me, but probably not obvious to anyone else who hasn’t been personally subjected to a lifetime of this language] revulsion for the Holies and Tamar was openly stated and if they tried to actually argue they were right to be revolted…..I would have loved them! Even if they are arguing Tamar (and indirectly, I too) was a disgusting thing — a ‘leper-soul’ (to quote this fanfic), mad and lost and ruined and degenerate (to quote *this canon book quote*)—I would have loved them! I have nothing but delighted love for people whose clawing desperate insistence on not being what they were raised and created to be, no matter how hateful that makes them towards my loves and experiences.

If Lucifer had said and stuck by this until proven wrong by the narrative [show not tell, or even tell or not show!], instead of simply going ‘oh don’t worry, I don’t think you’re bad :) I don’t think it’s harmful :) it’s just my issue :)’ whenever speaking about Holies, it would have been GOOD and I would have REALLY respected them. Even while everything they’ve actually said about their opinion of souls in other contexts is such that it fundamentally precludes and rejects, as sick and as nothingness and deluded and incapable of being real, the entire concept and lived real existence of Holies (Tamar: I saw them, I am someone who’s done that) — but then Lucifer being actively explicitly validated [again, i mean ‘gets validated’ as in the book states this, with a positive-presence, tell not show wording, while also refusing to admit anyone else influencing Eliya as much or more. i do NOT mean ‘waaahh it’s Obviously Validated becuz Lucifer doesn’t get explicitly called out’ or whatever].

In fact, this specific struggle, between what they state to be True, and what Tamar’s very existence declares to be a truth, would have echoed the struggle of their backstory, and conveyed the message of this book more powerfully, more clearly, more sincerely. But seeing Lucifer instead warp a way into an actively (tell not show) defined enlightened master position in the book’s narrative structure made me shake a bit, not going to lie.

Continued uhhhhhhh soon, links to other parts (continually updated) under the cut:

2

#LONG POST#i have 99 problems with this book and it's the most direct contact with my soul anything's had in years and complaining is really fun#the eternal combination#coal reads the stars that rise at dawn#girl with burned out and still burning eyes#VERY sorry if i forgot to put in a link somewhere i intended to.....lol#coal sings#<-new original post tag

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Sátántangó Experience

How exactly does one prepare to watch a 7.5 hour film? A bit like what you might do in preparation for major surgery: Pack a bag of necessities (in this case, water and protein bars), kiss your loved ones goodbye, and try to make peace with your god. Or, maybe less dramatically, treat it as you would a long train journey, one that takes you through some harrowing terrain on half a rutted track before depositing you to your eventual destination.

Of course, this sort of conception of time is entirely relative: If you have to drive somewhere that takes half an hour, it feels unduly long; but if the trip were normally three hours long, and you somehow found a shortcut that would cut the time down to 30 minutes, you would be flying on dulcet wings for that amount of time, and think you were blessed by angels. In other words, spending an entire standard work day watching one film might seem excessive, but it all has to do with your expectations.

In my case, I was at Philadelphia’s newly renovated Lightbox Theater at the University of the Arts to take in Béla Tarr’s magnum opus Sátántangó, all glorious 450 minutes, in a new 4K restoration (it’s currently playing at select theaters across the country). Armed with my snack survival kit, and safe in the knowledge that we would get intermissions at roughly 2.5 hour intervals, I settled in to watch what has been described as a masterpiece in cinephile circles, and currently resides at number 36 in the most recent Sight & Sound critics’ poll.

Tarr’s beyond-bleak film is broken up into 12 segments, each having to do with a failing farmer’s cooperative in Hungary during the last throes of communism in the late ‘80s. Each section has its own feel and perspective — some of them are more lighthearted, others are desolate beyond measure — but all expertly shot in low-contrast black and white (by Gábor Medvigy), which renders the people and landscape in various tones of drudgery grey.

It originally opened in America as part of the 1994 New York film festival, at a time when Hungary was undergoing a transformation from Communism to shaky democratic capitalism, so it served as a kind of epigraph to the era, a showcase, as it were, as to the imperfections of a political system built on a promise of human egalitarianism that proved to be depressingly difficult to put into practice.

The landscape makes up a lot of Tarr’s vision, the flat, moody farmland upon which the collective has been toiling, and the unceasing rain and wind that constantly pelts the characters as they venture outside for one business or another. As the film opens, the collective — made up of three couples; a curious “doctor” (Peter Berling), who spends his time spying on the others, making copious notes in his stacks of file folders, and daily drinking his considerable body weight in Palinka (Hungarian plum brandy); and the cagey Futaki (Miklos Szekely B.), who has to walk with a cane from an unspecified accident, but seems a bit more shrewd than the others — is anxiously awaiting their annual wages, which come all at once and is meant to get divvied up amongst the members equally.

Early on, there are various halfcocked plans from individuals to try and steal the small fortune for themselves, reflected in much idle talk about meeting that evening and decamping for parts unknown, but that ultimately come to nothing. However, when word reaches the group that the mysterious Irimiás (Mihály Vig, also the film’s composer) is, in fact, not dead as they had been told, but alive, and returning to the collective he started, the group dynamic is thrown akimbo, with various members fretting for their future, and, one, the owner of the local bar (Zoltán Kamondi), furious at the thought his business will be taken from him.

Just why they respond like this remains vague. In ensuing segments, we see Irimiás, along with his associate, Petrina (Dr. Putyi Horvath), navigating through a police interview — where the local Captain informs them they will be working for him now in ways unspecified — though it appears the collective had very actively planned on not having to include their former leader (and his right-hand man) in their financial arrangements. As for the non-collective characters, including the aforementioned barkeep, and various prostitutes sitting idly around, the collective is virtually their only business, such as it is, so they, too, await this potential flood of cash eagerly.

As the segments begin to collect, they also begin to fold upon themselves: Scenes that we see from one vantage point in an earlier segment are revisited later on, from the perspective of a different character, enabling a thrilling moment of realization that the stream of time we’re following has breaks, jumps, and hiccoughs throughout. Never more poignantly than a moment with a young girl peering into a window of the bar — one of the only lit buildings in the otherwise dismally dark countryside — watching the adults inside drunkenly dancing and cavorting.

About that girl. Easily the most emotional moment of the film involves her, but not first without the audience paying a heavy price, depending on your empathy for other creatures. Before the film screened, during its introduction, we were made aware that there was a scene of animal cruelty involving a cat somewhere in the proceedings. The sympathetic presenter, himself a cat lover, suggested looking away for parts of that segment, though a friend of mine in attendance who had seen it before assured me looking away wasn’t really an option. Fortunately, he also told me that the cat in question wasn’t actually hurt, and was still alive at the time of a 2012 interview with Tarr.

Needless to say, my worry about this poor cat dominated my experience in the early going: Every time I saw a feline in the background of a scene, I worried that it was coming up, such that it was almost a relief when it finally happened. The situation is this: Estike (Erica Bók), the young daughter of one of the local prostitutes, caught up in her world of half-fantasies after being sent out of their apartment by her working mother, holes up in an attic with a grey tabby. At first, she pets and cuddles him, but eventually, she desires to control him, bend the cat to her will. To the cat’s increasing discomfort and fury, she grabs him by the front paws and rolls around with him, all the while muttering how she alone can determine its fate. Looping up the poor fellow in a net bag and hanging it from a post, she goes downstairs to mix a batch of milk with some rat poison powder and force feeds him until he dies (though in actuality merely tranquilized).

Wandering around the farm that night with the stiffened body of the cat tucked under her arm (a prosthetic, the director assures us), Estike runs into the doctor, shuffling outside to refill his giant jug of brandy, shortly after peering through the window of the bar. Eventually, she lies down amongst the deserted crumble of a bomb-blasted church and takes the poison herself.

As gruesome as the segment becomes, its haunting evocations permeate the rest of the film (though not immediately: in a jarring juxtaposition, the very next segment takes us back to the bar, where everyone is still dancing wildly about to a loopy accordion refrain — only towards the end of this extended scene do we see the face of the soon-to-be-dead Estike peering inside). Eventually, Irimiás does indeed return, in time to give a moving eulogy for Estike, while at the same time transitioning the group towards his next vision, a new farm some distance away where he assures them they can finally live freely and thrive. All he needs to achieve this goal for them is the money they just received from their previous year’s efforts.

With nowhere else to go, and no other plan on the horizon, the members of the collective dutifully deposit their wages on the table in front of their leader. He sends them out to pack their things so that they may meet with him in a couple of days at the new farm he’s selected.

Gathering their miserable belongings, the group reassemble and trudge down the muddy road on foot, as the rain pelts down on them without ceasing. Distressingly, the members don’t have any proper rain coats — in an earlier soliloquy in the bar, Kráner (János Derszi) laments that his leather coat is so old and stiff he has to bend it in order to sit down — so they wear their woolen winter coats, which do little to keep them from getting soaked in the heavy fall rains.

As they make their way to this new destination, it’s clear that Irimiás is up to something. Most obviously, he could make off with their wages and move on, but it turns out his scheme is less direct than just taking their hard-earned money for himself.

Towards the second half, Tarr’s penchant for long, elegantly composed shots gives gradually away to more adventurous camerawork, including a single steadicam shot in the woods that’s like something out of a Sam Raimi film. There are extensive elliptical shots with the camera spinning slowly on an axis, this particular effect never more effective than when after the group arrives at their new farm, yet another dilapidated series of box-like concrete buildings. Once they dump their belongings and lie on the floor of the unheated, broken-windowed main house, trying to sleep, our narrator makes one of his occasional VO appearances to describe in intimate detail the dreams each character is having.

It’s a shot that could have served as an excellent final salvo, one would imagine. Indeed, by the last hour of this opus, time and again, Tarr arrives at what might be considered a conclusive moment — in this, the confusion is aided by his particular style: It turns out many films end on a superbly composed, static long shot — only to keep the narrative flowing, circling back, eventually to the original farm, where the doctor, having just returned from a stint in a hospital, begins to narrate, again, the original opening lines. Such is the perfection in this device (the segment is titled “The Circle Closes”) that once you finally arrive there, it’s clear there could be no other ending that would have sufficed.

When finally the film ended, it was later in the evening. I met up with my compatriots also in attendance, and the three of us ventured back out into the city, heading to a bar where we could nurse a beer and attempt to articulate the tangled mass of feelings and impressions of the previous nine hours. In one of the very few bars in the city that still allows smoking, appropriately enough, we debated about the film in an atmosphere swirling with the poisonous fumes of an earlier era. It seemed hopeless, but still necessary, somehow; like bidding farewell to someone already in a coma.

#sweet smell of success#ssos#piers marchant#films#movies#satantango#bela tarr#hungary#communism#Mihály Vig#philadelphia lightbox theater

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

10/25/21.

Chelou || Halfway to Nowhere

i want to focus on Sunday and how i felt.

i remember making my way down and feeling very confused at the weather. it was gloomy but very windy. i remember driving to Lone Fir Cemetery. it was beautiful to see the golden, orange, red leaves just dancing wildly like rain. it was pretty amazing. it was intense. it should have served as foreshadowing for what was to come that day.

i don’t remember exactly what you said but i remember how it felt hearing you in the moment. it sounded like you were in a lot of pain and that you are feeling unsafe. i couldn’t help you because i am a part of it and i think that i have a hard time with that. i want to fix things so that we can get back on track but i feel that it’s misguided and only leads to one of us feeling rushed to meet the other person where they’re at. it’s like the analogy she used where we’re trying to be a part of this race and i ran up and slow down and run up again. i have so much energy that needs to be redirected and focused.

you sounded like you were in a lot of pain and i remember this poignantly out of everything you’ve said...

i don’t want to get to a point where i want to break up with you. it feels like i’m stuck and i don’t know if i can even make the decision.

i think that therein lies my answer. i think let me help you. i think that i say something along the lines of i’m thinking that we should break up and not leave things in the air. how does this sound to you? it doesn’t mean that we’re done for good... just maybe not now. she says yeah with clarity. it makes me feel better for the both of us. i think that there will eventually be a feeling of... “good job, team. you recognized your limits and you did it without destroying one another”.

i am proud of us for that. before she leaves, she mentions i hope that you can appreciate the commitment i made when you told me that you weren’t ready for a relationship. at the time, i was still considering med school, was about to enter the travel pool after i took the MCAT. the difference is that i have these major things going on... 1) dealing with D and S’ deaths, 2) compassion fatigue, 3) giving up a dream of being a physician, 4) new medication, 5) nicotine addiction, 6) practicing new ways of communication, 7) reconnecting with the child in me, 8) responding to my body signals.

this is all stuff that i haven’t had the chance to talk about/feel with the help of a therapist.

today was the first time that i asked my therapist for what i needed. i told her that i need some help with staying focused when we talk. i need more straight forward conversations but are balanced with warmth. coldness = discomfort and uncomfortable Ave = low tolerance.

i realize that i haven’t thought about what you mean when you keep saying that you feel like i don’t want to spend time with you. i haven’t said anything because i was afraid that you were gonna reject my affection so sometimes, i also feel stuck and i don’t know where to go from here which i’ve been noticing that you express and it’s helpful to see that modeled.

i’m nodding off. i think thats my body’s way of telling me to go to bed.

isn’t that video pretty cool?

0 notes

Text

Kajillionaire: How the Evan Rachel Wood Movie Explores the ‘Mini-Cult’ of Family

https://ift.tt/2RPN4hK

Kajillionaire is the first feature film from writer-director Miranda July in which she isn’t also the star. It’s a different experience, stepping outside the frame and choosing instead to cast Evan Rachel Wood as her unconventional leading lady. But as the artistic polymath also tells us over a digital interview, she also “never [has] to stop looking at it from the outside.” The ‘it’ being an intimate portrait of a dysfunctional family of small-time scammers.

“I could go further,” July says during her conversation, “I could be more devoted to the actors… I wasn’t in there with them, in the fire.” This remove allowed her to be open to the final product, and letting it differ from her initial script. That and the confidence that comes from a long career of many hats.

“I’ve been now just making things in all mediums for a long time,” says July, a performance artist of all trades—from punk theater to sculpture installations, to a messaging app—who is used to wearing a dozen hats on a single project. “When you’re younger, you get really freaked out when things aren’t going according to plan; and by this point I think, ‘Well, there’s another way that’s gonna end up being the right way that’s different from what we planned.’”

That adaptability has served her especially well in the last six months of the COVID-19 pandemic, which delayed the release of Kajillionaire (among many other films) into theaters. Yet there’s a touch of self-fulfilling prophecy that July learned to embrace chaos in the current life-changing circumstances from her project about a brood of truly bad con artists whose attempts to score big earn them more problems than windfalls, with their half-baked schemes often spinning wildly out of control.

Though she wasn’t in front of the camera, July worked closely with Wood to develop the character of Old Dolio, the twentysomething daughter of a pair of lousy con artists (Richard Jenkins and Debra Winger), who nonetheless shares her parents’ fierce conviction in their scavenger lifestyle. Not only does Old Dolio not resemble July’s two avatars in her past films, Me and You and Everyone We Know and The Future, but her absence of femininity or softness distinguishes her from most twenty-something cinematic heroines.

“I’ve been wanting to work with [Miranda] for years and just jumped at the opportunity,” Wood says. “And then when I saw the kind of film she was creating, and the heroine that was Old Dolio, I was elated because you never get to see a leading lady look or act or sound like Old Dolio, and I had also never really read this script. And I’ve been doing this [for] over 25 years now, I’ve read a lot of scripts. So to actually be able to read a script that was so original I couldn’t compare it to anything else, that’s what excited me more than anything.”

With her lank hair, baggy tracksuit, and guttural voice, Old Dolio possesses the raised-by-wolves ferality of someone reared outside of mainstream society, especially with regard to hyper-feminized gender norms. Yet she’s clearly devoted herself to the Dynes’ scams, leaping, diving, and twisting herself into poses to evade security cameras—or just their long-suffering laundromat landlord.

“I’d never had a character who was gonna take some real work to get into,” July says. “I didn’t know if any of that was going to work, but I did think that rather than just arbitrarily come up with these physical restraints that it was important to sort of limit her intellectual state. I mean, she’s a full complete soul in there, but she’s not used to articulating, internally or externally, about her emotions.”

They workshopped the character together for about a week, with references and videos, so that they could build up what Wood describes as a “toolbox” once they got to set. “We had our own language that we had built for Old Dolio,” the star says. “Miranda could just call something out, and I would know what she was talking about. She would yell out, ‘Proud lion!’ ‘cause that’s one of the animals we had picked for Old Dolio, that she would emulate and have the same energy [as], and also when she needed to be slightly attractive for [Gina Rodriguez’s character] Melanie.”

That toolbox also gave them verbal shorthands for keeping Wood in-character; if it seemed like any feminine qualities (i.e., any of Wood’s own personality aspects) were coming through, July would yell out “hands” or “voice,” and her lead would remember to adjust her gestures or lower her voice.

In doing so, July says, they honed Old Dolio “until it was just physical. I was like, well, that sets her up inside her mind, her state, and from there she can probably do anything, was the hope. She could say these lines, she could do a tuck-and-roll.” While July had written in Old Dolio’s eccentric physicality before they began developing the character, she was gratified to see that Wood had no problem truly embodying the character.

“Evan actually could limbo, Evan could roll. You write all this stuff and then you’re braced to have to adjust to reality, but in Evan’s case, I never had to.”

Matching Old Dolio’s signature moves are the emotional and ethical gymnastics she must undertake as part of her family’s cons: whipping out the Catholic schoolgirl uniform when sweet-talking some rich marks; impersonating a stranger for a measly $20; forging signatures as easily as breathing.

“I related to Old Dolio in that way of a very unconventional upbringing and childhood,” says Wood, who has been acting for most of her life. “I was working since I was five, and sometimes seen more as a peer than as a child, and as a child star you can very easily confuse adoration and love, or performance and how it relates to love.”

Yet for all the necessary evils to which Old Dolio commits herself, she lacks the social intelligence to entirely pull them off; and her parents have no qualms about letting her know that they find her wanting.

“I think as Old Dolio understands it,” Wood continues, “love is a performance, in how well she does in these cons, and that [it’s] the only way to win her parents’ approval, and she convinces herself she doesn’t need anything else.”

Like money, Old Dolio can get by on a dearth of love—until the Dynes meet Melanie (Rodriguez), a bubbly young thing who is all too eager to get in on their schemes. Flirty and feminine where Old Dolio is awkward and androgynous, quick-thinking in a way that reveals a whole host of life experience, Melanie allows the Dynes to expand the scope of their cons; but Robert (Jenkins) and Theresa (Winger) also begin to project on her all of the affection that they’ve always withheld from Old Dolio in the name of supposed authenticity. “You get the sense that she knows something is missing,” Wood says, “and she can’t quite put her finger on it until Melanie comes into the picture.”

The slow-burn queer romance between Old Dolio and Melanie helps the former begin to envision a life outside of the Dynes’ restrictive existence of diminishing returns, and to experience a love (or at least the sense of being wanted) that she has long been lacking. But not even July initially intended for first love to be part of Old Dolio’s journey of self-discovery.

“I actually had Melanie in there a little bit before understanding that there was a romance,” July says, “and so Old Dolio had this repulsion and this reaction against her, and the parents adored her. And then I was like, ‘Ah, wouldn’t it be [wonderful] to give this woman all the joy of being loved by her.’ I just wanted that for Old Dolio.”

“We agreed that it was so easy to fall in love with each other,” Wood says about developing the romance with Rodriguez. “We had that chemistry right away. And with a character like Old Dolio, you have to be incredibly forward, because she just doesn’t get it, or doesn’t want to. Again, she had no exposure to things. It’s all new to her. What I love is that gender is never spoken about, and sexuality is never spoken about, it just is. And it’s a part of the film, but it’s not what the film is about.”

The absence of gender that Wood found so freeing seems to have been by design, as July explains that she was aware of gendered tropes and expectations when crafting this romance.

“I always thought that if Evan’s character had been a guy, that the second Melanie entered the movie, you would know that there was gonna be a romance,” she says. “You could make that a real slow-burn, you could totally work against it and hide it, because you just know already, because of the formula, that they were gonna end up together. So I enjoyed treating it the same way, like not overly indicating, giving it the same artfulness—holding my cards like that, and trusting it, just trusting.”

Read more

Movies

Toronto International Film Festival 2020 Movie Round-Up

By David Crow

TV

Westworld: What Dolores’ Fate Means for Season 4

By Alec Bojalad

One of the most artful moments in the film, which demonstrates not just the trust between July and her leads but also between Wood and Rodriguez, is Old Dolio’s dance. The scene is part of Melanie helping Old Dolio check off a list of formative life events she has been lacking up until now; the latter has never had the teenage experience of rocking out in one’s bedroom alone or with a friend. Yet the dance itself—set to the telephone hold music that is Old Dolio’s ersatz soundtrack for her own life—is entirely about Melanie being witness to Old Dolio’s pent-up anger and joy, poignantly inelegant yet hopeful.

Wood describes how she and Rodriguez each surprised one another: Rodriguez had not seen Wood rehearse the dance prior to shooting the scene; and when the cameras started rolling, the tears in Rodriguez’s eyes were completely authentic.

“She’s just that kind of actor,” Wood says. “She throws herself in, and she’s right there with you, just giving you everything.” Such moments also underscore why Wood feels like Kajillionaire was at times like shooting two different movies.

“There was the one with the Dynes, and there was the one that Gina and I were doing. And that was always so beautiful and tender and sexy and heartbreaking. That’s when we really got to lean into the heart and soul of the film.”

Arguably, what most identifies Kajillionaire as a Miranda July film is the surreal imagery of pink soap bubbles cascading over the wall of the Dynes’ shabby rented residence: an instantly familiar sitcom shorthand for a situation about to get out of hand, but that in July’s framing becomes strangely soothing. What began as the explanation for why they were able to live somewhere with such cheap rent—every day they must clean up the bubbles, only for the laundromat to inevitably produce more—took on a dreamlike beauty as July decided to link the bubbles to a recurring visual device in her films. In the case of Kajillionaire, the director says the bubbles “tap into that primal anxiety… they have to dispose of it in this Sisyphean way, but it keeps coming.”

Sisyphean could perhaps also apply to the staggered timing for Kajillionaire’s release. Following the film’s production, Annapurna Pictures declared bankruptcy, and July was forced to find a new distributor at Sundance; they did in Focus Features. The movie premiered at the festival in January 2020, weeks before whispers of COVID-19 began permeating America, and once the nationwide lockdown and quarantine began, its June release was pushed to September. While July acknowledges that she was of course disappointed “not to get to do my well-laid plans for this movie,” watching the film finally get released six months into COVID has given her a change in perspective.

That was due in large part to hearing from people within the last several weeks who were watching Kajillionaire for the first time during quarantine. “There was no other version of the movie to them but the one that they saw now,” she says. “It’s not that it’s a different movie, but there’s so many things in it that they spoke so intensely to me about—just a lot of little resonances with this time, and I think that made me feel like, ‘Well, maybe I was making it for us now.’”

July has found the silver lining on the metaphorical soap bubbles, in that Kajillionaire might be coming out exactly when it is supposed to. “That is the reality of what has happened,” she says, “so there’s no point in thinking that six months ago was my true time—like, no, I have to own it, this movie is for now.”

While filming Kajillionaire, Wood was also wrapping up three seasons’ worth of character arc for android Dolores on HBO’s Westworld. “There’s certainly parallels there,” Wood says of Dolores’ becoming self-aware and breaking out of her own loop compared to Old Dolio’s story. “I think that journey inward and that journey to consciousness is part of all of our journeys.” But her real takeaway is about breaking out of toxic loops, plus concerns of family as a whole.

“I’ve heard Miranda speak about families and how each one of them is its own mini-cult, in that they all have their own set of rules and morals and standards,” she says. “Each one is a little different, and we all go through a moment where we have to start defining ourselves separate from our family: what that looks like and who we really are, and what we really want. And sometimes that does not match up with the family that we have been raised in, and it can be quite jarring and traumatizing. Especially when you make the decision to share your true self with your family. I know queer people can certainly relate to some of this, and that idea of discovering who you are and sometimes having to leave the only thing that you’ve ever known.”

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

Wood hopes that Kajillionaire moves audiences to reconsider their childhoods and their own parenting styles, but her greatest wish is that it reaches the people who may never have seen themselves reflected back in film before: “I hope if there’s any Old Dolios watching, that they feel seen, and like they got to be the leading lady.”

Kajillionaire will be released in theaters on Sept. 25.

The post Kajillionaire: How the Evan Rachel Wood Movie Explores the ‘Mini-Cult’ of Family appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/32T6RTK

0 notes

Text

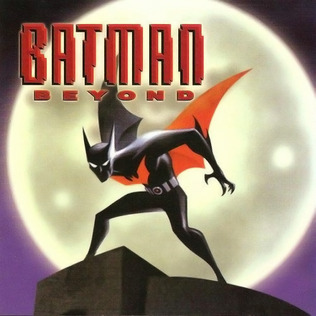

Before Spec Spidey Batman Beyond was called the best Spider-Man cartoon ever, more or less as an insult to all other Spider-Man cartoons, but more specifically the 1994 Spider-Man animated series.

Frankly in thinking about it...that’s really just superficial and ignorant.

The point of view stems from the following commonalities between Batman Beyond and Spider-Man, though I’m sure I am missing some.

1) They are both about teenage superheroes

2) The protagonists are both being raised by single mothers

3) Both have a blonde/ginger jock rival at school

4) Both have corrupt industrialist businessman villains who’re untouched by the law and believed to be perfectly innocent

5) Both have villains who have inky black bodies and shapeshifting powers

6) Both have friends who turn into villains

7) Both have villains who are urban hunters

8) Both have love interests who are morally grey, black and white clad costumes thieves

9) In one scene the protagonist of the story comes home to find police outside his house and informing him his father figure was murdered , believing that the killer’s actions had something to do with them, thus facilitating feelings of guilt within them

Let’s go through those points and discuss why Batman Beyond whilst a great show is really NOT the best Spider-Man show ever exempting Spec Spidey.

They are both about teenage superheroes

Spider-Man invented the archetype of the teenage superhero but it doesn’t inherently mean any teen hero equates to him.

That would be like saying every superhero ever equates to Superman.

Specifics of personality and life situation matter.

Peter Parker is a wholesome nerdy kid whereas Terry McGinnis is a modestly popular ex-juvenile offender and punk.

The protagonists are both being raised by single mothers

See above. Noticeably Terry doesn’t have to support his mother the way Peter supported Aunt May and she is neither elderly, sickly nor doting.

Both have a blonde/ginger jock rival at school

Sure, but whilst Flash Thompson was a jock with some semblance of redeeming features and adored Spidey, Nelson Nash was indifferent to Batman Beyond and generally seemed like an arrogant jerk and nothing more.

More poignantly while Flash was a bully and bullied Peter Parker specifically Nelson was not a bully to Terry McGinnis . They competed, were rivals but they ultimately hung in the same social circles whereas Flash was very much higher up the High school hierarchy than ‘Puny Parker’.

Both have corrupt industrialist businessman villains who’re untouched by the law and believed to be perfectly innocent

Derek Powers and his son Paxton Powers could be compared to Norman Osborn or Kingpin.

However Kingpin is more or less akin to Spider-Man in so far as he spawned an archetype of businessman criminals of which even post-Crisis Lex Luthor would fit. Does Kingpin own the franchise on this type of character and nobody else can play on it?

And whilst Derek Powers/Blight is a better analogy to Norman Osborn/Green Goblin due to their secret identities as villains (and green colour schemes) their personalities, motives and overall relationship are wildly different.

Derek Powers is more or less a ruthless and mercenary businessman. He breaks the law and hurts people, even kills them, but it’s all to simply protect his interests or make a profit.

Whilst Norman would definitely do things like that, for him the money is just a means to an end. That end being power. And unlike Derek who will kill and attack someone if you antagonize him, Norman is outright sadistic. He doesn’t seek to simply kill his enemies who’ve really gotten to him so much as destroy and torment them.

Finally for Derek Powers, being Blight is a frustrating illness he wants rid of and tries to not to spend too much time in that identity. For Norman it is the route he truly desires to seek power from. He loves it and feels complete when in costume.

Both have villains who have inky black bodies and shapeshifting powers

Again this is profoundly superficial.

Putting sex aside, Venom and Inque are very obviously completely different characters.

Inque’s powerset makes her a living blob.

Venom is a solid pack of muscle who uses said muscle and very physical force to attack with.

Inque is a mercenary and saboteur in it for the money and at most a little payback.

Venom is a delusional, obsessive stalker bent on revenge.

Inque is a at the end of the day just a villain to Batman Beyond.

Venom is a terrifying dark reflection of Spider-Man who preys upon his personal life.

Both have friends who turn into villains

My how utterly exclusive to Spider-Man and Spider-Man alone that is.

And of course vulnerable drug addict and abused kid Harry Osborn going over the edge and becoming a bad guy out of a desire for post-humorous paternal approval is just like Charlie Bigalow.

I mean he was a troubled punk kid who pushed the law with our hero when they were kids and wound up in prison before getting out and mutating.

They are the exact same thing.

Both have villains who are urban hunters

Kraven the Hunter is not the only example of a character like this. Merely the most famous.

Both have love interests who are morally grey, black and white clad costumes thieves

Ten is obviously Catwoman more than she is Felicia Hardy.

More poignantly Ten and Terry’s relationship plays out excluisivly in their normal identities and is about genuine young love. Ten also doesn’t honestly want the criminal life she leads and does so out of family obligation.

Peter and Felicia’s relationship begins in their costumed identities and is about Peter trying to turn her away from villainy and her thrillseeking ways making that difficult. Felicia is an adventurer because it’s who she is and wants to be, a decision she made for herself not out of any obligation.

In one scene the protagonist of the story comes home to find police outside his house and informing him his father figure was murdered , believing that the killer’s actions had something to do with them, thus facilitating feelings of guilt within them

Yeah but the Terry’s guilt is resolved by the end of the first 2 episodes when he learns his father’s death had nothing to do with him.

When the death of your teen hero’s father had nothing to do with their own actions and doesn’t teach them a lesson about how and why to be a hero then fundamentally you are not telling a Spider-Man story.

I could go on and on about other deviations between Spider-Man lore and Batman Beyond but instead I want to focus upon the stones thrown against Spider-Man the Animated Series by comparing this show to Spidey.

I’m not suggesting Batman Beyond wasn’t INSPIRED to some extent by Spider-Man but the idea that it was honestly a Spider-Man show in even an abstract sense or that it was the ‘best’ Spider-Man show until Spec came along is utterly boneheaded and superficial.

And I’m not talking about simplistic differences like the names, costumes and power sets of the leads being different or any of the deviations I listed above.

I’m talking about the spirit and core concept of Spider-Man vs Batman Beyond being intrinsically different to one another.

Batman Beyond conceptually is about a punk teenager who becomes Batman in the future, learning from Bruce Wayne and trying to redeem himself for his past as a punk. It’s dark, it’s edgy, it’s about legacy and helping a city which is in desperate need of the hero they lost long ago. A better analogy would be to say it is the Mask of Zorro to regular Batman’s Mark of Zorro.

Spider-Man conceptually is totally different. To begin with (and putting aside the futuristic setting) Spider-Man isn’t ABOUT being a teen hero. He merely started that way. Spider-Man is about one man’s life as he juggles the responsibilities of heroism alongside the normal life responsibilities most of us deal with at some point and the complications thereof. The point of the character is for him to be relatively speaking a relatable albeit nerdy guy and to examine the themes of responsibility, specifically in relation to the power one has in one’s life.

This is ignited by an origin story of a kid shirking his responsibilities and learning the harsh price of doing so. Batman Beyond much like Batman himself is a story not about someone becoming a hero because they saw the ramifications of them NOT being one but becoming a hero because the forces of evil took someone they love, so they resolve to try and prevent such a thing from happening again. Peter’s story is an aesop’s fable where he is shaped by his own mistakes whilst Burce and Terry’s stories are about cruel chance shattering their lives. They are innocent victims in the tragedy of their origins, whereas Peter is not, he could have prevented calamity.

It goes without saying Spider-Man the animated series got this right so I don’t see how on this count anyone could say Terry is Peter and therefore Batman Beyond was a better Spider-Man tv show.

Furthermore a vital part of the core concept of Spider-Man was his status as a independent, self made man. This again was captured in the 1994 cartoon whilst Batman Beyond hinged upon the student/teacher relationship between Terry and Bruce Wayne. This would be a categorical betrayal of Spider-Man’s story if done in a Spider-Man show.

Tonally Spider-Man the Animated Series captured the vitally important grey area Spider-Man typically occupies as a series. Spider-Man stories can fall somewhere between light and fun, dark and serious. Usually they mix the two together so that there is bombastic colourful superhero action alongside more grounded real life human drama. Spider-Man the Animated Series eloquently captured this vast range with dark stories like the Alien Costume Saga, goofier episodes like the Spot spotlight episode and the ‘somewhere in between’ like the debut of Mysterio which generates pathos for our hero whilst showcasing the over the top character of Mysterio, having Peter and Mary Jane flirt over the phone and have her later dump him. Batman Beyond meanwhile was appropriately dark and edgy most of the time with occasional ventures into the light and the fun.

Microcosm of this can be seen in the characters’ divergent senses of humour. For all the one liners and jokes Terry McGinnis dropped, his style of humour was akin to a James Bond ‘cool one liner’ or Ali’s trademark disses. Spidey in the 90s cartoon much like in the comics, was more of a witty banterer, prone to mocking the absurdity of a villain, a situation and even his own lifestyle.

Some examples to illustrate the differences.

In Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker Terry McGinnis confronts the Jokerz gang and says:

It's a school night, boys and girls. I'm gonna have to call your folks.

Cool. Bad ass. And one of the few things Terry says in the proceeding fight, let alone one of the few jokes.

In the episode Doctor Octopus Armed and Dangerous, Doc Ock says

Spider-Man! You're making a career of interference!

Which then prompts our hero to say:

Some career! No salary, no vacation; and talk about on-the-job health hazards!

Later in the same episode this exchange happens:

How does it feel to know that you could change things, Spider-Man, but be helpless to do so?

Not as bad as I'd feel if I had a name like Doc Ock!

See what I mean. Terry has a sense of humour but it functions totally differently to Spidey’s.

In terms of story structure Batman Beyond followed the typical DCAU standard of making mostly self-contained episodes which were mini-movies in a sense. Now it DID have one notable subplot which was Derek Powers’ medical condition which ran during the first season. But really that was it. Beyond that whilst some episodes exist post certain shifts in the status quo a lot of episodes are interchangeable in their viewing order. Typically any given episode is just a day in the life of Terry McGinnis .

And I’m not insulting the show for that, it worked beautifully. But it is totally not how Spider-Man’s comic book series nor Spidey TAS functioned. Although one could shift some episodes around in the first season of Spider-Man the animated series the majority of the show demanded you see the episodes on sequence to get the full story.

Peter’s life much like the comics wasn’t a series of day in the life adventures, but rather a forward flowing narrative wherein events of one day might impact upon the next and so on and so forth.

Spider-Man in episode 10 of season 1 is casually interested in Mary Jane Watson and Felicia Hardy. By the concluding episode of season 3 he’s very much in love with Mary Jane and debating ending his career as a superhero to be with her. By the final episode of season 5 he’s come to complete peace and acceptance in his life despite the absence of Mary Jane, whom he is determined to find and be with. These events run in conjunction with shifting developments and subplots in the lives of the supporting cast. In season 1 Norman Osborn gets in debt to the Kingpin whom Spider-Man is unaware is Wilson Fisk, meanwhile Felicia Hardy is casually dating Flash Thompson. In season 3 Norman becomes the Green Goblin and seeks to kill Kingpin to free himself of the debt, whilst Felicia is trying to move on from her lost love Michael Morbius with Spider-Man himself and Jason Macendale who is in fact the Hobgoblin who was originally created by Norman Osborn to kill Kingpin to free himself of the debt. In the course of the season Spidey learns Kingpin’s identity, Kingpin pressures Norman to reveal Hobgoblin’s identity prompting Norman to become the Goblin again and reveal Macendale’s relationship to Felicia whilst also trying to get rid of him and Fisk.

Which brings me to my next point. Whilst Batman Beyond did have a supporting cast they didn’t get half the play that Spider-Man’s did, which is appropriate because the supporting cast is a vital part of Spider-Man’s lore. To underuse them or not have them is to most definitely be screwing up Spider-Man. In this regard if we were judging the two shows as a Spider-Man adaptation Spidey TAS crushes Batman Beyond as the supporting cast is large, present and has their own subplots beautifully intertwined with one another and the main plots overall. And often times these sorts of entanglements are romantic in nature, far moreso than in Batman Beyond.

All of which is VITAL to the spirit of Spider-Man the comic book series but is mostly absent from Batman Beyond.

I could go on but to start wrapping things up lets ponder the question of WHY anybody in t he face of these incredibly obvious deviations ever claim Batman Beyond is the best Spider-Man show ever or in fact a Spider-Man show at all?

Because...it had better production values.

Honestly that is the real reason. Batman Beyond had better animation and used less stock footage, therefore it was better as a Spider-Man show than Spider-Man the Animated Series.

And I won’t deny it’s better quality production values, nor will I dive into why the production values were different.

But I will say this...it’s superficial. I’m not saying good animation isn’t important to an animated TV show but good lord surely the story and the characters themselves are at least AS important if not moreso. In that regard Spider-Man the Animated series as a Spider-Man show is egregiously superior than Batman Beyond.

It is truly an honest and heartfelt interpretation of the Spider-Man mythology as it existed at that time.

Batman Beyond is not. It’s just an incredibly awesome show unto itself that took cues from the same lore but was it’s own thing.

People need to stop being superficial morons and saying otherwise.

#Spider-Man#Batman#Batman Beyond#Spider-Man the Animates Series#terry mcginnis#Peter Parker#DCAU#DC animated universe#Marvel Animation#Blight#Derek Powers#Norman Osborn#Inque#Venom

103 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://toldnews.com/technology/entertainment/review-novel-revisits-culture-wars-aids-crisis/

Review: Novel revisits culture wars, AIDS crisis

“The Spectators” (Random House), by Jennifer duBois

A deadly school shooting serves as a pivotal event in “The Spectators,” a novel that revisits American cultural wars and crises in the last decades of the 20th century.

Mostly set in New York City, the novel looks at this period through the experiences of two wholly different characters: a gay man, Semi, who is a playwright grappling angrily and poignantly with the AIDS crisis; and an unhappy young woman, Cel, a publicist for a wildly successful and hated television talk show featuring increasingly bizarre guests.

Told in alternating sections about Semi and Cel that move back and forth in time, the meandering narrative revolves around a central figure, Matthew Miller. He’s a calm but crusading lawyer and politico who makes a run for mayor of New York City before switching careers and hosting “The Mattie M Show.”

His show’s freakish subjects, such as devil worship and incest, ignite on-set threats and violence that may or may not be real. But fake or not, the show draws huge ratings and voluble scorn — even a claim that “Mattie M,” through its riveting media mayhem, is responsible for the two teenage students who opened fire in a high school classroom.

As one of the shooters explains: “I didn’t know it was real.”

“The Spectators,” the third novel by the well-regarded author Jennifer duBois, often thrums with vibrancy and echoes divisive current events as it covers a timeline from the late 1960s to the early 1990s. It also gains momentum when the plot takes a sudden, sinister twist —a threat of blackmail, a shooter’s potentially explosive letter, a secret taping. But it can turn tedious when the prose is overly embellished or a scene goes on too long.

Through Semi, the novel looks back at the gay sexual revolution and the anguish of AIDS in the 1980s. Semi says one of his plays was a “modestly elegiac retrospective of what had happened.” In sections of “The Spectators,” however, his words are a searingly felt remembrance.

For Cel, the distress in part is over the ugly faux media environment she wants to flee.

Cel and Semi don’t know each other and move mostly in different circles, but Matthew Miller, aka Mattie M, is connected to both — he was Semi’s secret lover — and is the key unlocking the narrative as their stories converge.

———

Online: https://www.jennifer-dubois.com

#Arts and entertainment#bollywood movie#Books and literature#celebrity gossip#celebrity news#Cultures#Diseases and conditions#Entertainment#entertainment news#Gays and lesbians#Health#HIV and AIDS#hollywood movies#Infectious diseases#Matisyahu#movie reviews#music concerts#New York#New York City#North America#Social affairs#United States

0 notes

Text

As a writer myself, the commentary that @tumblhurgoyf has added here hits VERY close to my heart.

Writing (like all other creative acts I can think of) is a process with a LOT of layers. And to some extent it’s a process that never truly ends as long as the creation exists and has an audience.

In the past I’ve written about how I believe that the line between speculative fiction (sci-fi) and fantasy is the presence or influence of magic. And I would define “magic” as “a force without an individual identity that can impact the world subjectively, with an unexplainable understanding of the context and/or intentions of those affected by it.”

That’s a mouthful, so here’s the shorter version: “Magic is allowed to care about what characters WANT it to do, rather than be governed by consistent rules.”

In my own fantasy series, I treat magic like an extension of art that can physically impact its environment. After all, a scientific process should yield consistent results, an artistic process can produce wildly different results depending on the artist, their circumstances, what they need, what they’ve created before, or who the audience is.

In science you want to limit your variables. In art and magic, the variables are what make new creations possible at all. And one of the biggest and most important variables is the audience.

Readers are what transform a work of literature from a collection of words on a page or screen, into ideas, characters, and whole worlds.

Writers offer up little pieces of themselves in everything they write. Then readers step up and offer pieces of themselves to fill in the gaps, give the words context and meaning, and bring those words to life. And because each reader brings different pieces of themselves to the experience, the “story” contained within the imaginations of the audience, will be somewhat different for every person.

And then there’s that “generative process” that @tumblhurgoyf describes so poignantly. When readers come together and share their own interpretations and observations with each other, to create something else magical and exciting.

And at each stage of the process, the progress is additive. What results from the audience reading the story is greater than what the author alone created. What results from multiple readers sharing their thoughts and insights with each other and discussing those points together, is greater than the sum total of what each reader brought to the conversation.

It’s all part of a process of creation, and it only STARTS with the writer, rather than ending with them.

It's this "generative process" that gets me so excited about discussing this kind of stuff with my wife! Because it was the two of us talking and thinking and sharing TOGETHER that led to this fan theory. Neither of us would have come up with it on our own.

And it's that same generative process that gets me so excited about continuing to discuss it with all of you! Who knows what's still in store for us to discover?!

So once again I want to say a HUGE thank you to @tumblhurgoyf for the insightful and thoughtful commentary!!

And for those of you with thoughts to share who may be feeling shy, PLEASE JOIN IN!!! Because the more people who contribute to this generative process, the more insights we ALL get out of it!

Soul Purpose

While driving home from the beach last weekend, my wife and I started discussing Voldemort’s horcruxes (as you do) and we were talking about whether the different horcruxes had different abilities. For example, could all of them potentially make a new, living Voldemort, the way that Tom Riddle’s diary almost became fully corporeal when it was draining the life from Ginny?

My wife contended that not all the horcruxes had that ability, and the reason that the diary could do that was because it was the memory of Tom Riddle, and was simply bringing that memory to life. That statement led to a fascinating idea…

Each horcrux represents a specific piece of Voldemort’s soul that he wanted to tear away from himself

Now you might be thinking, “That’s nothing new. We’ve known that each horcrux was a piece of Voldemort’s soul since book 6.” But what I’m saying is that the horcruxes weren’t just random pieces of his soul. They were specific pieces.

Or to be more precise, these specific pieces:

Gaunt’s Ring - His history

Riddle’s Diary - His identity

Slytherin’s Locket - His fears

Ravenclaw’s Diadem - His doubts

Hufflepuff’s Cup - His pleasures

Nagini - His humanity

Harry Potter - His purpose

Have you ever wondered why Voldemort went to the trouble to create six horcruxes intentionally? (Plus one on accident.) I mean, just one horcrux could have kept him from dying as long as he kept it safe. Why would anyone intentionally tear off SIX pieces of their own soul? Unless they were pieces that you didn’t want anyway…

I believe all of these horcruxes, with the exception of Harry, were meant to contain aspects of Voldemort that he believed were holding him back from achieving his fullest potential and fulfilling his destiny. And that tearing off those pieces not only drastically altered who Voldemort was, but each piece defined what that horcrux could do, and how things changed once each one was destroyed.

To support this theory, let’s look at each horcrux in detail…

(This gets pretty long, and includes lots of spoilers for anyone who hasn’t finished all the books yet, so I’m going to put the rest of the post under a link.)

Keep reading

#creative writing discussion#writing commentary#hp fan theory#harry potter fan theory#horcrux theory#wizardsuzy#magicfolk#voldemort#generative process#writer reader relationship#artist audience relationship#random thoughts from dave#long post#supercarlinbrothers#harry potter fandom

1K notes

·