#but for the most part moffat was left to his own devices

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Always hilarious seeing people say they think Moffat was better under RTD's direction because the way RTD tells it he just left Moffat alone to do what he wanted because he trusted him to always deliver something good.

#doctor who#dw#at most he'd give him a brief to start with#like include madame de pompadour and a cloakwork man#but for the most part moffat was left to his own devices#and rtd never reworte any of his scripts because they all came in exactly as he liked#moffat was the sole writer he trusted to always deliver#which is why he pushed for him to succeed him#and brought him back#because he isn't a writer rtd feels needs a lot of supervision#which frees him up to focus on his own scripts#which is the exact opposite of what happened with chibnall#he was so busy overseeing all the other writers he had barely any time for his own scripts

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

NOT A NEW THEORY AND NOT THE MOST POPULAR.

Moffat missed the biggest opportunity to bring an arc full circle and the thought of it makes me want to throw up.

Let me start by saying I think this theory still holds true even with the way the story has progressed.

DONNA NOBLE IS THE HYBRID.

Hands down zero doubts.

That's why 12 chose his face.

That's why he lied and lied and went through the whole confession dial thing.

1 he was mad about Clara sure.

2 He was protecting Donna (obviously)

That's why fate had their timelines all twisted together not only for the whole davros destroys all of creation thing but because he was always intertwined with the hybrid.

That's the real reason he erased her memories and him asking you know what this means and her saying yeah hurts so much more because she knew why her memories had to be erased because the prophecy had been passed down in Timelord history only to sprout it's beginnings there.

This brings me to MOFFATS MISSED OPPORTUNITIES:

Donna Noble or rather her new hybrid form had her memories erased to protect her.

Wilf said she seems okay but every once in a while he sees this look on her face like she is so sad... But she can't remember why.

Memories erased and Timelord part of her suppressed. Things were still leaking through. The doctor knew his psychic memory block wasn't up to par. This was furthered by his need to use the device on clara for the full memory purge.

So my theory goes; Little by little donna starts becoming clever, and sad. She can't understand what is missing what is wrong with her. Eventually being around her mundane life doesn't cut it for her anymore and she begins searching for answers elsewhere.

Always trying to fill that hole the doctor left inside her.

"The prophecy identified the Hybrid as a being born of two warrior races, and said that one day the Hybrid would stand in the ruins of Gallifrey and "unravel the Web of Time and destroy a billion billion hearts to heal its own."

She couldn't remember she couldn't remember, and every time she had a breakthrough she would black out.

The only single thing that kept bleeding through was "Timelord" "Timelord" "Timelord" "Timelord"

But what did it mean? What was a Timelord?

All she knew was that she had to keep looking.

This nagging question lead her into many dangerous instances with many other alien races. All of which she was some how able to out witt with information she had no idea how she knew.

Eventually she finds herself on Gallifrey standing before the cloysters still looking for answers.

How many lives were lost? how far gone was the once donna noble at this point? Just to get her here. The Timelord home planet. In the cloysters where the mass of their great knowledge inevitably ends up.

She stands there in tears. Almost unrecognizable as the Donna Noble we love.

The 12th Doctor's voice can be heard from behind her:

"Donna Noble I am so so sorry."

#donna noble#doctor#doctor who#the doctor#timelord#moffat#give me some feedback because this has been banging around in my head forever now#thinkingaboutwhatwelost

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Big Moffat Rewrite: Series 7

Following on from my Series 5 and my Series 6 rewrites

XMAS SPECIAL The Snowmen

The Bells of Saint John

The Rings of Akhaten

Cold War

A Town Called Mercy

The Slow Invasion

Journey to the Centre of the TARDIS

Asylum of the Cybermen

Nightmare in Silver

Dinosaurs on a Spaceship

Hide

Supremacy of the Daleks

Extermination of the Daleks

The Name of the Doctor

The Snowmen

· 11 is still a recluse in Victorian London, but because in my Series 6 he left the Ponds instead of losing them, it’s because he’s convinced he’ll screw up if he travels again. After wiping himself from history he’s lying low, not helping because he’s convinced he’ll make things worse

· (also he’s totally wallowing in self-pity because of his self-imposed exile from the Ponds)

· Clara re-convinces him he can make positive change, drags him out of his self-absorption, shows him something new

CLARA’s CHARACTER

· Clara gets all of series 7. Moffat originally wanted The Time of the Doctor to be a whole series, so we can fit some of that stuff about the Silence and Trenzalore in here.

· GIVE CLARA A FUCKING ARC – the Doctor takes an ordinary girl who he thinks is special, and accidentally makes her special

· Most people seem to prefer Victorian! Clara to her in S7B anyway, so she becomes that flirty, authoritative character by the finale

· The pieces were already there – her being scared in Cold War compared to her taking charge in Nightmare in Silver, but make it explicit – the Doctor realises he is changing Clara and turning her into the person he met in Victorian London and the Cyberman Asylum

· This sets up her arcs and relationship with 12 – he brings out the liar in her, forces her to become cold and calculating. This is now already happening with 11

The Rings of Akhaten

· Introduce Trisha Lem, the head of the Church of the Silence, here. The best part of this episode is The Speech, but we could easily say that the Silence is presiding over the Long Song ceremony to appease the Old God, taking the place of those creatures hunting the little girl.

· (I imagine the Church pre-Trenzalore as a kind of Shadow Proclamation for religion - presiding over and safeguarding the religious traditions of species across the universe)

· This way Trisha and the Silence’s role as confessionals doesn’t come out of nowhere in The Time of the Doctor

· 11 and Trisha’s relationship being so flirty confuses me - as the head of the Church, 11 must associate her with all the pain the Silence caused River and the Ponds. Instead, he acts really flirty but Clara notices he’s faking it – a reflection of their own relationship?

· Trisha doesn’t understand why 11 is being elusive.

A Town Called Mercy

· Use this story’s framework – a Western where 11 is forced to protect war criminal – and insert River

· Partly bc River and Clara interacting seems super interesting

· River is angry at 11 for ‘replacing’ the Ponds. I also think she’d be competitive with Clara? As she’s scattered all over the Doctor’s timestream, Clara is the only person who really could compete with her

· As an archaeologist expert on the Doctor River knows about Clara, but can’t tell 11 exactly what she is

· Also 11 agreeing with River’s more violent methodology is really interesting and shows how they can feed into each other’s dark sides – think River’s line from The Angels Take Manhattan – “One psychopath per TARDIS, don’t you think?”

The Slow Invasion

· A version of The Power of Three told from the perspective of the Alice character who replaced Craig in S5/6. 11 pops in and out of her life with different versions of Clara

· It’s revealed that 11 has tried to travel with different versions of Clara before, tracking her down all across the universe, but she always, always dies. Our Clara doesn’t know.

· Alice is deeply critical of what 11 is doing. She acts almost as his therapist; he comes over for tea and talks to her about what’s going on.

· Instead of the cubes being alien exterminators, this is a plot buy the Great Intelligence (series 7′s big bad) inspired by the Skith from DWM comic The First and Superman villain Brainiac – i.e. the Intelligence is collecting all information it can about a thing, and then destroys it to stop that knowledge becoming commonplace and therefore losing its value. Specifically, the Intelligence is also investigating Clara (because she keeps appearing across its timeline). The Intelligence’s fascination is a dark parallel to 11’s

· Alice asks 11 what happened to the Ponds, and he reveals they still think he’s dead. Alice tells 11 to go see them (the ending scenes of The Doctor, the Widow and The Wardrobe). She also tells him to start treating Clara like a real person, not a human question mark

· 11 takes Clara to meet them. River is also there, having dinner. The episode closes with them reconnecting

Pond Life

· After The Slow Invasion launch this minisode series about life post-11, with River barging in instead of the Doctor

Journey to the Centre of the TARDIS

· Tie the TARDIS disliking Clara into the series arc – it’s because the TARDIS knows Clara is an anomaly scattered through the Doctor’s timestream. Have a scene in Journey To the Centre of the TARDIS where 11 argues with the TARDIS about it – “Do you know what she is? You do, don’t you? I miss the time when you could talk and just tell me.”

· The TARDIS went to the end of the universe to throw Jack Harkness off, and 11 abandoned Future!Amy in The Girl Who Waited because the TARDIS hates paradoxes – this is the same kind of thing, just make it clear by the finale (Clara even jumps into the time stream INSIDE the TARDIS)

· Clara remembers the events of the episode so she can be be active in the investigation of who she is, (also fixing how the episode undoes the three brothers’ arcs, but still insists they grew as people at the end)

This represents 11 opening up to her and trusting her more

Asylum of the Daleks (retitled Asylum of the Cybermen)

Roll Nightmare in Silver and Asylum into a 2-parter, because the best part of Nightmare is Mister Clever. Both episodes even have the same ‘someone’s about to destroy the planet’ ticking time bomb.

The army fighting the Cybermen kidnap 11 to get him to destroy the Asylum with a bunch of expendable grunts they can afford to lose to a suicide mission.· Clara meeting/interacting with another version of herself is really interesting, so we keep converted Oswin saving them·

Changing it to Asylum of the Cybermen makes more sense thematically

All those people, including Oswin, being converted – the Asylum’s security system is its conversion machinery – attackers become part of the security system. Instead of a nano-cloud, use the tiny upgraded Cybermats·

It would also be scarier (a haunted hospital a la World Enough and Time- botched cybermen > insane Daleks) and would add an interesting layer to Cyberman lore instead of making the Daleks look weak. It can also use old models to explain the Cybermen’s multiple backstories, touched on in The Doctor Falls (”everywhere there’s people, there’s cybermen,” 12 says)·

The ‘subtracting love’ thing makes more sense with cybermen too – instead of Amy and Rory, focus on Clara holding onto her connection with 11 – emphasising their genuine, emotion-based bond over ‘flirty quirky plot device’·

This renewed focus on the Cybermen is good because the last full-on Cyberman story was in Series 2 (in The Next Doctor they’re just kind of in the background), and Moffat is much better at writing the body-horror of the Cybermen than he is writing the Daleks.

Nightmare in Silver

· 11 deliberately lets himself be ‘infected’ by the asylum’s nanocloud and begins conversion in attempt to save the converted Oswin’s mind.

· Ladies and Gentlemen, I give you the origin of Handles, the Cyberman head from The Time of The Doctor: the remains of Oswin’s cyber-converted mind downloaded into a head.

· 11 uses Mr Clever to get information about her - i.e. that she just appeared one day as a fully-formed person without any family. This sets up the other Claras being time remnants.

· It also lets Mr Clever play more psychological games with 11 and Clara – Mr Clever reveals 11 is scared of Clara, putting more strain on Clara having to hold on to her emotional attatchments

· The Cybermen are actively trying to get out. This way we dig into their primary drive – survival at all costs,

· What happens when a Cyberman’s emotional inhibitor is broken, but they don’t die? Driven insane and desperate, and fiercely intelligent.

· I like the idea of the Cybermen like the Xenomorph in Alien; blending in with thoier broken down, mechanical environment, plugging into it and using to separate and play games with the soldiers.

Dinosaurs on a Spaceship

· Replace The Crimson Horror with a version of Dinosaurs on a Spaceship with the Paternoster Gang replacing Brian, the Ponds, Nefertiti and that hunter bloke

· I just really need to see Vastra interacting with her culture OK? Seeing her be taken back to her childhood, opening up to Jenny about it. Her anger, realising what the villain Solomon has done to her people. Use this conflict to call back to and explain how she met the Doctor, how he stopped her slaughtering humans before.

· Clara and 11 go to the Paternoster Gang for help investigating her other selves

· Clara researches and finds her past selves, not only in Victorian London but also throughout the 60s and 70s, when she’s helping the past Doctors – finding this research is how the kids find out she’s a time traveller

· This is how THE DOCTOR REALISES HE’S SEEN HER MANY TIMES BEFORE, setting up The Name of the Doctor’s out-of-nowhere, un-guessable resolution.

· Dark!11 again. Matt saoid they would’ve explored a ‘meaneer’ version if he’d stayed on for series 8. Clara is the perfect way to bring that out as they lie and manipulate each other for their own ends.

DALEK CIVIL WAR STORY

· Progenitor Daleks vs the regular Time War model. Display how the Progenitor Daleks are different - each of them having a different weapon/role etc. The crux of the story is that the Progenitor Daleks are better at fighting the Doctor and come close to killing him, but the other Daleks value their ‘purity’ and survival more

· Maximum Dark!11

The Name of the Doctor

· When 11 rescues Clara she is changed – she retains bits and pieces of her time remnants’ experiences, it’s at once traumatising and exhilarating

The Time of the Doctor

· Whereas The End of Time felt stretched-out (135 minutes) this felt really rushed. Make it 2 parts.

· We see the set-up of Trenzalore and the Church of Silence in the first.

· The second part is the long siege of Trenzalore – we need to see 11 age fighting these monsters, taking his turn being left behind, the tragedy of him slowly losing his memory, focusing on his character

· We can also flesh out the citizens of Trenzalore and Christmas so their safety is important to us

· Let’s see Madame Kovarian and her splinter cell break off from the main Church of Silence and leave to try and kill the Doctor – make her a supporting character

· Then have Trisha Lem explicitly talk to the Doctor about how Kovarian blowing up the TARDIS caused the cracks in the universe in the first place, allowing the Time Lords to get their message out. Instead of a montage, have this be the moment that unites the Doctor and the Silence – they are both fighting to make up for their mistakes and the problems they caused

· We see the many races surrounding Trenzalore form the alliance from The Pandorica Opens

#doctor who#eleventh doctor#matt smith#clara oswald#clara oswin#jenna louise coleman#jenna coleman#steven moffat#stephen moffat#dw#bbc doctor who#doctor who series 7#11th doctor#series rewrite#amy pond#the paternoster gang#madame vastra#strax#The Big Moffat Rewrite#doctor who dalek#cybermen

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dracula (2020)

(spoilers) I’m kinda sad that I didn’t watch this one with one with a bingo chart or a drinking game. Even with all of its plot mutations and character updates, Netflix’s Dracula (2020) is pretty much exactly what I expected from a Mark Gatiss & Steven Moffat take on the classic source material: a self-congratulatory, over-produced adaptation obsessed with its own “cleverness” and with its overbearing main character, sprinkled with juuuust enough moments of genuine innovation to make it really sting when it all amounts to a big dud. If you have seen Jekyll, Sherlock, and the worst of Moffat’s Doctor Who episodes, you know exactly what I mean. If you don’t, I refer you to this entertaining and ridiculously long video essay (that absolutely merits every second of its 1 h 49 min runtime) by YouTuber hbomberguy: https://youtu.be/LkoGBOs5ecM; even though I don’t completely agree with all of his points, he does make a strong, multifaceted argument on why, despite his admitted talent, Moffat’s writing usually ends up sucking hard. Anyway. I think the first episode of the three-part Dracula series does make some kind of case for itself. It sets a distinctive mood, includes some pretty solid performances, tells a coherent story, and introduces some truly impressive and creepy horror imagery. I also enjoyed the inclusion of Sister Agatha - even though her being revealed as the Van Helsing of this version is definitely one of those Gatiss & Moffat moments that the writers thought would be much more of oooooh moment than it actually ended up being - who did serve as a formidable opponent for Dracula for the first two episodes. As I said, Moffat tends to anchor his stories to an overbearing lead around whom all other characters revolve, and while that’s is definitely the case here as well, Sister Agatha does stir up the dynamics by refusing to dance to his tune. Still, the writing is also riddled with the usual Moffat plagues, which stay mostly at bay in episode 1 but end up becoming more of an issue in the second episode. The second episode, which fully takes place on the doomed ship Demeter’s journey to Britain (which I believe has been the subject of a horror film script that has been stuck in Hollywood’s development hell for years and years - I wonder if it’ll ever get made now that the story concept was basically executed here?), is overlong, and it’s weighed down by an unnecessary framing device that develops into an unsurprising plot twist, and by the general lack of interest in creating emotional investment in any other character besides the two leads. Just like the ship, the story drifts in the fog for ages but almost makes it to shore in one piece, only to be sunken down by the most stupid thing I’ve watched in a very long time: episode three. Yikes. I do my best to give credit when credit is due and point of the merits of things I overall disliked, but I honestly can’t say that there was anything in the finale that I liked. It’s a mess, and not even a hot one. It’s more like they dug up the long-dead remains of Jekyll, carved out the most awful bits, reheated them, and then left them out to cool down again. I could go on and point out every little thing I found exasperating about the episode, from the regrettable time jump to the lack of thematic focus, to Van Helsing going on and on about the “illogical” nature of Dracula’s weaknesses like it’s remotely interesting, to the clumsy narrative structure that picks up and abandons plot threads like it’s an indecisive customer in a thrift shop, to Zoe Van Helsing becoming just another addition to Moffat’s long line of seemingly “strong” female characters who are rendered basically powerless by the overwhelming charms of the male lead, and all the way to what must be my least favourite horror trope - a paramilitary, pseudo-scientific secret organization set on capturing and studying monsters (seriously, can we please retire this unexciting trope that has never once improved any horror property?) - but for now I’m only going to address the one that made me groan the hardest: Lucy. If you are at all familiar with the novel or any of its numerous adaptations, you might also be aware of the conversation around Lucy and Mina, the novel’s two female characters who both embody Victorian ideas about women and sexuality. A popular reading is that Lucy, the flirty little minx with various suitors who ends up being seduced and corrupted by Dracula, is the whore to Mina’s virgin, which reflects the narrow, black-and-white, judgmental attitudes towards women who stray from the Victorian ideal of the virtuous, demure woman with no appetite for sex or male attention outside marriage. In that sense, the 2020 incarnation of Lucy is a faithful adaptation of the character from the book. And that’s precisely the problem! Just because Bram Stoker’s book is sexist, it doesn’t mean that this version should be that as well. But it is, and oh god I hate it so much. Gatiss & Moffat’s Lucy is a glittery, uncaring thot who takes selfies and DMs strange men, because of course she is; shaming young women for liking sex, being beautiful, and enjoying attention is exactly the sort of thing men who cannot relate to women do when they’re trying to be insightful. And as if that wasn’t enough, they also give Lucy “depth” by making her resent her beauty in some way that remains woefully unexplored, because heaven forbid pretty girls should have any thoughts inside their head that aren’t directly related to being pretty. Even the shallow, dark edge they give to the character fails to bring her any sense of complexity and humanity, and she ends up being just a beautiful creature for men to gaze at in both adoration and condemnation. A beautiful creature who must ultimately be cruelly punished for the sin of being lovely and untameable. How’s that for some Victorian bullshit? More than anything, Dracula reads like a revue of Gatiss & Moffat’s (particularly Moffat’s) greatest and most recurring grievances as writers: a self-defeating attempt at outwitting the audience with “surprising” plot twists hammered awkwardly into the story at the cost of anything that might have made it good, ambitious world-building ideas left to die as soon as they’ve been introduced, an overreliance on a scene-chewing, dickish male lead character who’s supposed to be bad but, like, in a fuckable way, pointless queer-baiting that is guaranteed to elicit frustrated screams from certain parts of the internet, and terribly written female characters with inner worlds conceived by a middle-aged man who is evidently unable to imagine a woman whose every thought isn’t motivated by uncontrollable lust for aforementioned dickish male lead. Jesus.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hawksmoor, BBC Sherlock and historiographic metafiction

First:

This piece is not of academic quality or rigour. I left university eight years ago; I studied literature in two languages and did well at it. Nevertheless I am no longer in academia and have not written an essay since then. My sources are partial, dependent on what I can get access to through my local library, through academic friends, or what I choose to pay for on JSTOR. I work full-time and have put no time into e.g. referencing (always my least favourite part of essays).

Although I personally hold out hope for unambiguous Johnlock still, I would not class this as a ‘meta’ arguing that it will certainly happen. This is a reading, undertaken for my own satisfaction and interest, jumping off from the inclusion of ‘Hawksmoor’ as a password in one scene of The Six Thatchers. I do not particularly mean to suggest that Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat are deliberately playing with/off literary criticism. They may well be holding two (or more) time periods in tension, however, in a way that I choose to explore through the lens of the literary tools described here. I do not seek to challenge or disprove other fan theories.

I am no television/film studies scholar. There are probably layers and layers of nuance and meaning that I’m missing because I simply have no frame of theoretical reference in that field (and one of the primary ‘texts’ we are talking about here is, after all, a television show). The abundance of television and film references discovered by Sherlock fans have made it clear that the show’s creators deliberately allude to other visual media within modern Sherlock all the time. I believe my approach here is valid because Hawksmoor, a literary text, is pointed to in the show, and because ACD canon itself was a literary text. But I want to flag up this important way in which my analysis is deficient.

I tagged a few people in this but I’m aware this is more of a musing/essay than a traditional ‘meta’ so don’t worry about reading/responding if it’s not your thing!

The Six Thatchers

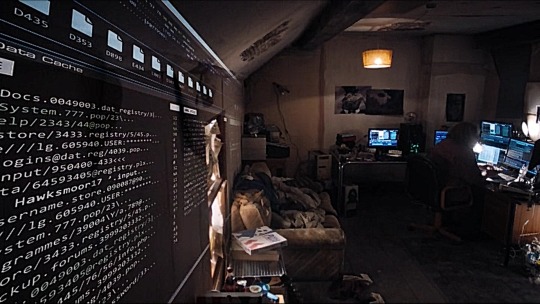

In The Six Thatchers, Sherlock visits Craig the hacker, to borrow his dog Toby. On the left of our screen (taking up an entire wall of Craig’s house, realistically enough…) are lines of code, in the centre of which is written ‘Hawksmoor17’.

I was interested in finding out more about this. I decided my first port of call would be the ‘detective novel’ Hawksmoor, by Peter Ackroyd.

Peter Ackroyd

Peter Ackroyd is a historian and author, who has written a huge array of fiction and non-fiction, including:

London: The Biography (non-fiction)

Queer City: Gay London from the Romans to the Present Day (non-fiction)

The Last Testament of Oscar Wilde (an imagining of the diary Oscar Wilde might have written in exile in Paris)

Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem (novel, presenting the diary of a murderer)

Hawksmoor (novel)

In his work London is present, constantly, a character in itself, woven into the very fabric of the story as irrevocably as it is into the mythos of Sherlock Holmes.

Hawksmoor

In brief, Hawksmoor is a postmodern detective story, running in two timelines. Each timeline focuses on a main character: in 1711, the London architect Nicholas Dyer; two hundred and fifty years later, in the 1980s, Nicholas Hawksmoor, a detective, responsible for investigating a series of murders carried out near the churches built by Dyer.

Ackroyd plays with the ‘real history’ of London throughout, muddling and confusing the past with fictional events, with conspiracy and rumour.

There was a real London architect named Nicholas Hawksmoor who worked alongside Christopher Wren in eighteenth-century London to design some of its most famous buildings. He also designed six churches. Ackroyd chooses to change the eighteenth-century architect’s name to Nicholas Dyer, and to make Nicholas Hawksmoor the twentieth-century fictional detective instead – a deliberate muddling together of timelines and of ‘facts’.

Ackroyd had drawn inspiration for Hawksmoor from Iain Sinclair’s poem, ‘Nicholas Hawksmoor: His Churches’ (Lud Heat, 1975). This poem suggests that the architectural design of Hawksmoor’s churches is consistent with him having been a Satanist.

As well as changing the historical figure Hawksmoor’s last name to Dyer, Ackroyd adds a church, ‘Little St Hugh’. Seven, in total.

The architect Dyer writes his own story, in the first person and in eighteenth-century style.

Only in Part Two of the novel does Nicholas Hawksmoor – a fictional detective with a real man’s name – appear, to investigate the three murders that have so far happened in 1980s London. Written in the third person, the reader is nonetheless invited into Hawksmoor’s thoughts, his point of view.

As the novel proceeds, Ackroyd employs literary devices so that the stories – separated, apparently, by so much time – begin to blur. In particular, the architect Dyer and the detective Hawksmoor are linked. For instance, both men experience a kind of loss of self, a “dislocation of identity”, upon staring into a convex mirror (Ahearn, 2000, DOI: 10.1215/0041462X-2000-1001).

The cumulative effect of all the parallels is that the reader starts to lose any sense of temporal separation between the time periods; starts to see Dyer and Hawksmoor as almost the same person; to suspect each of them of being the murderer and the detective at the same time. The parallels between the time periods “escape any effort at organization and create a mental fusion between past and present” so that “fiction and history fuse so thoroughly that an abolition of time, space, and person is […] inflicted on the reader” (Ahearn, 2000).

Importantly, I believe, Hawksmoor again and again “tries to reconstruct the timing of the crimes, but this is from the start impossible” (Ahearn, 2000). This is a rather familiar feeling to Sherlock Holmes fans.

At the end of the book, Dyer and Hawksmoor come together in the church, take hands across time, or perhaps out of time. They become aware of one another. Their perspectives dissolve and seem to merge into one person, into a new style of narration not like either of them: “when he put out his hand and touched him he shuddered. But do not say that he touched him, say that they touched him. And when they looked at the space between them, they wept” (Ackroyd, 1985).

Historiographic metafiction

Hawksmoor is a postmodern detective story. It has been classified by critics as a work of ‘historiographic metafiction’. As a detective story, it lacks the most familiar feature – a detective who is able to sort and order the events and facts, before finally drawing together all the threads to present a coherent, satisfying and plot-hole-free conclusion. In other words, a solution to the mystery.

So what is ‘metafiction’? Waugh defines it as “a term given to fictional writing which self-consciously and systematically draws attention to its status as an artefact in order to pose questions about the relationship between fiction and reality” (1984).

In Hawksmoor, Ackroyd uses a popular literary form (the detective story) to unsettle our understanding of fiction, reality and history. An Agatha Christie detective novel (for example) relies on an accepted, understood structure, where the reader has definite expectations of what the outcome will be; as such, Christie’s novels “provide collective pleasure and release of tension through the comforting total affirmation of accepted stereotypes” (Waugh, 1984). In metafiction, however, there is often no traditionally predictable, neat, satisfying ending: accepted stereotypes are disturbed rather than affirmed. The application of rationality and logic to the clues gets the detective no closer to solving the crime. Readerly expectation (“the triumph of justice and the restoration of order” [Waugh, 1984]) is thwarted.

Hutcheon coined the term ‘historiographic metafiction’, fiction where “narrative representation – fictive and historical – comes under […] subversive scrutiny […] by having its historical and socio-political grounding sit uneasily alongside its self-reflexivity” (Hutcheon, 2002). It is a kind of fiction that explicitly points out the text-dependent nature of what we know as ‘history’: “How do we know the past today? Through its discourses, through its texts – that is, through the traces of its historical events: the archival materials, the documents, the narratives of witnesses…and historians” (Hutcheon, 2002).

Whereas a ‘historical novel’ will present an account of the past which purports to be true, a ‘historiographic metafiction’ has a combination of:

deliberate, self-reflexive foregrounding of the difficulty of telling ‘the whole story’ or ‘the whole truth’ especially due to the limitations of the narrative voice;

internal metadiscourse about language revealing the fictional nature of the text;

an attempt to explain the present by way of the past, simultaneously giving a (partial) account of both;

disturbed chronology in the narrative structure, representing the determining presence of the past in the present;

‘connection’ of the historical period structurally to the novel’s present;

a self-consciously incomplete and provisional account of ‘what really happened’ e.g. via ‘holes’ in the [hi]story which cannot be resolved by either narrator or reader (Widdowson, 2006, DOI: 10.1080/09502360600828984).

The above points are certainly true of Hawksmoor. The reader of Sherlock Holmes will find some of them very familiar – for example, Watson’s self-conscious in-world changing of dates, names and places; and the impossible-to-resolve timeline. The audience of BBC Sherlock will also find these features very recognisable, especially from Series 4 of the programme.

I’d like to examine BBC Sherlock itself as a ‘historiographic metafiction’: a ‘text’ which self-consciously holds the past and present fictional events of Sherlock Holmes’ life in tension, not merely as another adaptation of the source text, but as a way of destabilising the accepted ‘[hi]story’ and mythos of Sherlock Holmes.

The Great Game

The Sherlockian fandom is well-known for its practice of ‘The Great Game’:

“Holmesian Speculation (also known as The Sherlockian game, the Holmesian game, the Great Game or simply the Game) is the practice of expanding upon the original Sherlock Holmes stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle by imagining a backstory, history, family or other information for Holmes and Watson, often attempting to resolve anomalies and clarify implied details about Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. It treats Holmes and Watson as real people and uses aspects of the canonical stories combined with the history of the era of the tales' composition to construct fanciful biographies of the pair.” [x]

There are a number of interesting features about the Great Game. It:

pretends that Sherlock Holmes and John Watson were real people;

ignores or explains away the real author Arthur Conan Doyle’s existence;

attempts to use ‘real’ historical facts (texts…) to resolve gaps in a fictional text;

in turn, produces additional (meta)fictional texts, often presented as ‘fact’ in journals set up for the purpose;

in so doing, adds constantly to the (meta)fictional destabilisation of chronology and holes in the story, as different, competing ‘versions’ are added by a multitude of authors.

The Sherlock Holmes fandom, as it attempts to elucidate ‘what really happened’, only destabilises the original (hi)story further – drawing attention, over and over again, to the gaps and inconsistencies in the original canon tales.

I would argue that the Sherlock fandom has been engaged, for over a century, in an act of collective historiographic metafiction.

The writers of BBC Sherlock are aware of themselves as fans, and of the wider Sherlockian fandom. They paid tribute to Holmesian Speculation in the episode title of Series 1 Episode 3. The title – ‘The Great Game’ – is a signal, an early marker of postmodernity in BBC Sherlock, a sign that the Sherlockian fandom will not be absent from this metafiction.

Implicating the reader/audience

There is an interesting moment in Hawksmoor where Detective Chief Superintendent Nicholas Hawksmoor goes to investigate the murder of a young boy near the church of St-George’s-in-the-East. The body is beside “a partly ruined building which had the words M SE M OF still visible above its entrance” (Ackroyd, 1985).

As Lee says, the “missing letter is "U," ("you") the reader” (1990).

Elsewhere in the book, Hawksmoor receives a note instructing him “DON’T FORGET … THE UNIVERSAL ARCHITECT” alongside a “sketch of a man kneeling with a white disc placed against his right eye” (Ackroyd, 1985).

Lee suggests that this drawing refers to “detective fiction’s transcendental signifier” Sherlock Holmes, and that the “Universal Architect, here, can only be the reader, since it is he or she who is in possession of all the histories: the historically verifiable past, the eighteenth-century text and the text accumulated through reading”. Thus, the reader is “doubly implicated not only as a repository of the past, but also as a co-creator of artifact and artifice” (Lee, 1990). In the Sherlock Holmes fandom, this is more true than in almost any other; co-creators indeed.

The missing ‘U’ in Hawksmoor can be clearly linked to the daubed ‘YOU’ in ‘The Abominable Bride’, a sign that, from that point on, BBC Sherlock will be clearly and mercilessly implicating its audience; putting the Sherlockian fandom back in the story, where it has always belonged. This includes the writers and creators of BBC Sherlock.

I also think there is reason to link the ‘YOU’ daubed on the wall to another piece of graffiti in BBC Sherlock – the yellow smiley face in 221b. An all-seeing, ever-present audience within Sherlock and John’s very home.

It is often repeated that Arthur Conan Doyle only continued to write Sherlock Holmes stories out of financial necessity and due to public demand; that he was bored and exasperated by his creation. The Sherlock Holmes fandom is (possibly apocryphally) known as having worn black armbands in the street in mourning for the fictional detective when Conan Doyle attempted to kill him off in The Final Problem.

The Sherlock Holmes fandom has long been considered importunate and unruly. As Stephen Fry puts it in his foreword to The Case Book of Sherlock Holmes: “Holmes has been bent and twisted into every genre imaginable and unimaginable: graphic novels, manga, science fiction, time travel, erotica, literary novels, animation, horror stories, comic books, gaming and more. Junior Sherlocks, animal Sherlocks, spoofs called Sheer Luck and Schlock; you think it up, and you’ll find it’s been done before. There is no indignity that has not been heaped upon the sage and super-sleuth of Baker Street” (2017).

And yet, with every new adaptation, there is a tendency to regard it as a blank slate, in direct conversation with the canon of Arthur Conan Doyle. There is a tendency to forget the changes that fandom itself has wrought on the figure of Sherlock Holmes – a weight of stereotype and expectation which warps the character to a pre-fit mould in every incarnation. As Fry says, Holmes:

“rises up, higher and higher with each passing decade, untarnished and unequalled. Because, I suppose, we need him, more and more, a figure of authority that is benign, rational, soothing, omniscient, capable and insightful. In a world, and in daily lives, so patently devoid of almost all those marvellous qualities, how welcome that is, and how grateful we are, for its presence in our lives. So grateful, that we won’t really accept that Sherlock Holmes could ever be classed as ‘make believe’. Between fact and fiction is a space where legend dwells. It is where Holmes and Watson will always live” (2017).

This is the traditional understanding of Sherlock Holmes and its fandom, and is highly reminiscent of the voiceover by Mary Morstan in Series 4 Episode 3, ‘The Final Problem’: “I know who you really are. A junkie who solves crimes to get high, and the doctor who never came home from the war. Well, you listen to me: who you really are, it doesn’t matter. It’s all about the legend, the stories, the adventures. There is a last refuge for the desperate, the unloved, the persecuted. There is a final court of appeal for everyone. When life gets too strange, too impossible, too frightening, there is always one last hope. When all else fails, there are two men sitting arguing in a scruffy flat like they’ve always been there, and they always will. The best and wisest men I have ever known – Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson.” [transcript by Ariane Devere]

The conception of Sherlock Holmes as “a figure of authority that is benign, rational, soothing, omniscient, capable and insightful” shows what we, the reader, want: a traditional detective story, with an all-knowing detective, who uses rationality and logic to assess the clues and brings us smoothly, at last, to a solution which reasserts the order of things; where justice is done and society is made safe once again.

BBC Sherlock, however, resists these comforting fictions. The detective unravels, becoming more emotional, more human as the story progresses. Mysteries go unsolved. The narrator gets more unreliable with every episode. Characters inhabit strange states, seemingly alive or dead as the story demands. The ‘rules’ of traditional detective fiction are flouted left, right and centre.

Viewed as a historiographic metafiction, BBC Sherlock aims to hold up the historical text (ACD canon) against the modern one (BBC Sherlock) in such a way as to slough away a century of extra-canonical fan speculation and addition, and give a new reading to canon.

‘Writing back’: re-visionary fiction

I would now like to look at Peter Widdowson’s journal article, ‘Writing back’: Contemporary re-visionary fiction’ (DOI: 10.1080/09502360600828984). He argues that there is a “radically subversive sub-set of contemporary ‘historiographic metafiction’” which, while being “acutely self-conscious about their metafictional intertextuality and dialectical connection with the past”, ‘write back’ to “formative narratives that have been central to the textual construction of dominant historical worldviews”.

Widdowson explains that his term ‘re-visionary’: “deploys a tactical slippage between the verb to revise (from the Latin ‘revisere’: ‘to look at again’) – ‘to examine and correct; to make a new, improved version of; to study anew’; and the verb to re-vision – to see in another light; to re-envision or perceive differently; and thus potentially to recast and re-evaluate (‘the original’)” (2006). He points out that this is closest to Rich’s approach to feminist criticism: “We need to know the writing of the past, and know it differently than we have ever known it; not to pass on a tradition but to break its hold over us” (Rich, 1975).

This act of ‘knowing it differently’ can also be achieved by “the creative act of ‘re-writing’ past fictional texts in order to defamiliarize them and the ways in which they have been conventionally read within the cultural structures of patriarchal and imperial/colonial dominance” (Widdowson, 2006).

Widdowson lays out what he regards as the defining characteristics of re-visionary fiction, first negatively by what it is not:

Re-visionary fiction does not simply take an earlier work as its source for writing;

It is not simply modern adaptation – instead it challenges the source text;

It is not parody – whereas parody takes a pre-existing work and reveals its particular stylistic traits and ideological premises by exaggerating them in order to render it absurd or to satirise the ‘follies of its time’, a re-visionary work seeks to bring into view “those discourses in [the source text] suppressed or obscured by historically naturalising readings. The contemporary version attempts, as it were, to replace the pre-text with itself, at once to negate the pre-text’s cultural power and to ‘correct’ the way we read it in the present” (Widdowson, 2006).

As to what re-visionary fiction is:

First, it challenges the accepted authority of the original. “[S]uch novels invariably ‘write back’ to canonic texts of the English tradition – those classics that retain a high profile of admiration and popularity in our literary heritage – and re-write them ‘against the grain’ (that is, in defamiliarising, and hence unsettling, ways)”. This means that “a hitherto one-way form of written exchange, where the reader could only passively receive the message handed down by a classic text, has now become a two-way correspondence in which the recipient answers or replies to – even answers back to – the version of things as originally delineated. In other words, it represents a challenge to any writing that purports to be ‘telling things as they really are’, and which has been believed and admired over time for doing exactly that.”

Second, it keeps a constant tension between the source and the new text. A re-visionary fiction will “keep the pre-text in clear view, so that the original is not just the invisible ‘source’ of a new modern version but is a constantly invoked intertext for it and is constantly in dialogue with it: the reader, in other words, is forced at all points to recall how the pre-text had it and how the re-vision reinflects this.”

Third, it enables us to read the source text with new eyes, free of established preconceptions. Re-visionary fictions “not only produce a different, autonomous new work by rewriting the original, but also denaturalise that original by exposing the discourses in it which we no longer see because we have perhaps learnt to read it in restricted and conventional ways. That is, they recast the pre-text as itself a ‘new’ text to be read newly – enabling us to ‘see’ a different one to the one we thought we knew as [Sherlock Holmes] – thus arguably releasing them from one type of reading and repossessing them in another.” The new text ‘speaks’ “the unspeakable of the pre-text by very exactly invoking the original and hinting at its silences or fabrications.”

Fourth, it forces the reader to consider the two texts together at all times: “our very consciousness of reading a contemporary version of a past work ensures that such an oscillation takes place, with the reader, as it were, holding the two texts simultaneously in mind. This may cause us to see parallels and contrasts, continuities and discontinuities, between the period of the original text’s production and that of the modern work.”

Fifth, they “alert the reader to the ways past fiction writes its view of things into history, and how unstable such apparently truthful accounts from the past may be”, making clear that the original text, though canon, was also just a text and should not necessarily govern our perceptions and understanding forever.

Sixth, “re-visionary novels almost invariably have a clear cultural-political thrust. That is why the majority of them align themselves with feminist and/or postcolonialist criticism in demanding that past texts’ complicity in oppression – either as subliminally inscribed within them or as an effect of their place and function as canonic icons in cultural politics – be revised and re-visioned as part of the process of restoring a voice, a history and an identity to those hitherto exploited, marginalized and silenced by dominant interests and ideologies.”

That last point, I think, should also apply to queer re-visionings of source texts (and indeed, Widdowson uses the example of Will Self’s Dorian: An Imitation re-visioning Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray in his article).

We can view BBC Sherlock as a re-visionary fiction which aims to ‘speak’ “the unspeakable of the pre-text by […] hinting at its silences or fabrications.”

BBC Sherlock as re-visionary fiction

Not only does BBC Sherlock have to hold itself up against the original canon of Arthur Conan Doyle; there is also a century of accumulated speculation and creation by an extremely active and resourceful fandom to contend with.

I think that BBC Sherlock asks us to re-vision ACD canon, but has a few sly jabs at the Sherlock Holmes fandom (including the writers themselves) along the way. Let’s look at some concrete examples:

John Watson’s wife:

In BBC Sherlock, the woman we know as Mary Morstan has no fixed identity. Her name is taken from a dead baby; she is not originally British; she is an ex-mercenary and killer; she is variously motherly, friendly and threatening; she shoots Sherlock in the heart – or does she save his life? In Series 4, her characterisation is more unstable than ever. She is a romantic heroine, a ruthless killer, a selfless mother, a consummate actress, a wronged woman, a martyr, an ever-present ghost, and the embodiment of John’s conscience. She is also the manifestation of the Sherlock Holmes fandom’s speculation about John Watson’s wife: did he have one wife, or six? Was she an orphan, or was she at her mother’s? When did she die? How did she die?

Ultimately, however, if you hold BBC Sherlock up against ACD canon, it highlights the fact that so many Sherlockians have tried to compensate for: in order to reconcile the irregularities in Mrs Watson’s story as narrated by Watson, she would need to be a secret agent actively hiding her identity. Examining BBC Sherlock against ACD canon makes us apply Occam’s Razor – the idea that the simplest explanation will always be best. John Watson’s wife was only written into the story because homophobia was so pervasive at the time that ACD was writing that his characters – and by extension he himself – would have been suspected of ‘deviance’ if there had not been a layer of plausible deniability in the shape of a wife.

And there you have it: the central problem of Mary Morstan/Watson, in both ACD canon and BBC Sherlock – she shoots Sherlock in the heart – or does she save his life? Look at ACD canon again. Does Mary Morstan’s engagement to John Watson hurt Sherlock Holmes, to the point that he replies, at the end of SIGN, “For me, …there still remains the cocaine-bottle”? Or does Mary Watson save his life? In the nineteenth century, suspicion of a romance between Sherlock Holmes and John Watson could have meant imprisonment or even hanging; many men suspected or accused of same-sex relationships chose suicide rather than total disgrace. Mary Watson’s presence provides Holmes and Watson with a lifesaving alibi.

Let’s have a look at this against the criteria for a ‘re-visionary fiction’:

Challenges the idea that Watson ‘told things as they really were’ – instead, it introduces the idea that Watson deliberately obscured the facts of his and Holmes’ partnership

Keeps the pre-text Mary Morstan constantly in view – a startling contrast, which rather effectively comments on the position of both women and queer people in the nineteenth and twenty-first centuries

Enables us to abandon our “restricted and conventional ways” of reading the original – if it makes no sense for Mrs Watson to have existed in ACD canon, then the reader must radically reconsider Holmes and Watson’s relationship; no longer ‘just’ a friendship, but a lifetime’s commitment, as close and loving as a marriage. BBC Sherlock encourages this re-visioning by setting Mary up as a rival to Sherlock; by having her attempt to get rid of him; by highlighting that she both kills and saves him. It re-casts Sherlock Holmes as the dominant romance of John Watson’s life, in every version.

It causes us to see parallels and contrasts between the two time periods: the societal homophobia that made Mrs Watson a necessity in ACD canon has largely gone in modern Britain. But BBC Sherlock hints at a profoundly closeted bisexual John Watson who strives after a ‘normal’ wife who “wasn’t meant to be like that”. The continued presence of a Mrs Watson very effectively shows us that societal attitudes are not as profoundly different as we may think.

BBC Sherlock shows us how the existence of a Mrs Watson has been written not only into the [hi]story of Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, but into the fabric of society: Sherlock Holmes is a great man, but God forbid he should also be a happy, human man, in a loving relationship with another man. The cultural script has been written: the great figures are either straight, or they are nothing. There is always a wife.

As discussed above, the presence of Mrs Watson is also important politically and culturally. It draws attention to the total lack of agency for nineteenth-century women, and to the restrictive narratives imposed on female characters in today’s culture. It makes terribly clear the extent and dangerousness of the homophobia in nineteenth-century Britain. It highlights the fact that there are still countries today where people are forced to hide their sexualities for fear of being imprisoned or killed.

The Watson baby:

In BBC Sherlock, the woman we know as Mary Morstan is revealed to be pregnant on the Watsons’ wedding day. In ACD canon, Watson never mentions a child from his marriage. In Holmesian speculation, plenty of children have been suggested for Watson, especially since it is often posited that he must have had more than one marriage (that Watson might be infertile is not something the proponents of the ‘Three Continents Watson’ school of thought often like to suggest).

As a re-visionary fiction, then, BBC Sherlock forces us to examine the source text: in a time when reliable contraceptive methods were virtually non-existent, why did John Watson and his wife never have a child?

The options, broadly, are:

Mrs Watson was infertile (if Watson only had one wife)

Watson was infertile (if he had more than one wife)

They didn’t have sex, either due to ignorance (but Watson was a doctor…) or reluctance

Mrs Watson only ‘existed’ because societal homophobia made her a necessity (see above).

John Watson:

In Series 4 of BBC Sherlock, John behaves in an unrecognisable manner: he beats Sherlock bloody, so that his eye is still bloodshot some little time later. This is said to be due to the pain of losing his wife, and the fact that her death is Sherlock’s ‘fault’.

Viewed as re-visionary fiction, as metafiction, BBC Sherlock here satirises the idea of the ‘deutero-Watson’ which has existed since Ronald Knox wrote his Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes. It also, however, critically examines the fact that, in ACD canon, there are (at least) ‘two Watsons’: one, the narrator, seemingly the most reliable and loyal of fellows, straight (in all senses) and true, good in a fight; and a second, the ‘true’ John Watson behind the narration, the man we discern when we look beyond the surface of the tales. A man who is devoted, above all, to Holmes; prepared to adopt Holmes’ habit of ‘compounding a felony’ to follow the idea of justice as opposed to law; prepared, in fact, to break the law if Holmes thinks it right; prepared to abandon his wife at a moment’s notice, when Holmes calls; prepared to alter all kinds of details in his stories to protect their participants. (Also, presumably, a bit of a joke about the accidental ‘dual personality’ that ACD gave his Watson by naming him James and John on different occasions.)

Looking at ACD canon through the lens of BBC Sherlock, the entirely unreliable nature of Watson as a narrator comes to light, but the enduring feature of his stories – his love for, and loyalty to Holmes – provides the obvious answer to why he should be so unreliable. Watson may be ‘two people’, but he lies, he breaks the law, he abandons his wife and his patients for only one person: Holmes.

Ultimately, the reader understands that they have been lied to, because the truth would have been impossible to tell at the time ACD was writing. Famously, the final story in the Sherlock Holmes canon, The Adventure of the Retired Colourman, ends with the words, “some day the true story may be told.”

If BBC Sherlock is seen as re-visionary fiction, Series 4 of the programme becomes a representation of the artificiality of the construct that we think of as BBC Sherlock and – viewed through its lens – ACD canon becomes visible as an equally artificial construct, filtered through the writings of an unreliable narrator and governed by the societal and cultural imperatives and prejudices of its time.

Every trick has been employed in Series 4 to highlight its artificiality: lack of coherent structure, temporal uncertainty, incoherent character arcs, introduction of a deus ex machina character, fluctuations of genre, and members of the crew actually appearing on screen. Just as in Hawksmoor, the ‘case’ of Series 4 defies solution. BBC Sherlock and Hawksmoor are both postmodern detective fictions. We have been told that this is ‘a show about a detective, not a detective show’. The form of the show, like the form of the traditional detective novel, leads us to expect a neat, tidy ending, explained carefully by an all-knowing figure of authority. The makers of BBC Sherlock, however, have done everything they can to pantomime a lack of care for, or understanding of, their own show. They have simultaneously inserted themselves into the story (Mark/Mycroft; giving varying accounts of when/how Series 4 was written; lying and saying that they lie) and withdrawn the ‘grand narrative’, the fiction of the omniscient narrator.

Why?

For over a century, ACD canon has been read in the same way: as the most archetypally logical detective story available to us. The fact that the canon is a huge mess of inconsistencies, requiring the collective effort of thousands of people to pick away at, is typically explained by the idea of an omniscient but uncaring storyteller: Arthur Conan Doyle.

This is particularly ironic for a fandom which supposedly wishes to disavow the existence of an author at all.

And yet, the problem is, if you don’t slip into extra-universe speculations on ACD’s attitude to Sherlock Holmes, you have to face head-on the conclusion that Watson is a very, very unreliable narrator indeed.

And you have to face why.

@devoursjohnlock @garkgatiss @221bloodnun @tjlcisthenewsexy @may-shepard

#sherlock meta#hawksmoor#bbc sherlock#acd canon#historiographic metafiction#postmodern detective fiction#hawksmoor17

409 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best of 2017

Countering the truly embarrassing news cycle of the past year was the deluge of great new music released upon the world, so much so that I’m leaving a good chunk of more than deserving albums hanging. To simplify everything, this is a compendium of what was played most around here, along with a handful of new-to-me reissues/archival releases.

I skipped doing the rap recap this year because my list was so pathetically brief, and doing so seemed both short-sighted and irrelevant. That being said: Quelle Chris’ Being You Is Great, I Wish I Could Be You More Often was my favorite album, followed by Starlito’s Manifest Destiny and Playboi Carti’s vapid, relentlessly fun album. Goldlink’s “Crew” featuring Brent Faiyaz and Shy Glizzy was my favorite song, like everyone else.

Full list of 30 records below. We’ll do better next year.

LP

12. Mount Trout, Screwy (self-released)

This unassuming, digital-only gem crept up on me as the months turned cold. Scraps of paper with notes written on them are held afloat by spare guitar lines; elsewhere winds whip in and chaos overtakes clarity. Lots of the lyrics sound like half-thoughts that forced themselves out after extended periods of solitude, sometimes peaceful, sometimes anguished. Screwy rewards patient attention without dragging you through the mud - but it’s there, should you need to cool off.

11. Group Doueh & Cheveu, Dakhla Sahara Session (Born Bad)

The intriguing pairing on Dakhla Sahara Session turns out to be one of the best surprises of the year, and easily one of the most listenable. Cheveu’s robotic yet effervescent contributions are immediately recognizable, as are Group Doueh’s swirling guitar lines and sweeping vocals; the two fit in and around each other, explosion welded together into a foundation for a colored smoke tower.

10. Leda, Gitarrmusik III-X (Förlag För Fri Musik)

The two people behind Neutral put out a lot of music this year, most of it well worth hunting down despite its highly limited, premium price barrier. I can’t claim to have heard everything, but by my count the two best were Neutral’s När mini-LP and Leda’s limited-to-100 Gitarrmusik III-X LP. Most of this sounds like King Blood collaborating with Robert Turman, looping machinations mixing with heavily distorted shredding, all of it recorded in a metal-walled bunker. Doesn’t sound like much on paper, but when you arrive at “Gitarrmusik VIII” and “IX,” time just about stops. (If you missed out, “Gitarrmusik I” and “II” are available here.)

9. The Body & Full of Hell, Ascending a Mountain of Heavy Light (Thrill Jockey)

The first collaboration between these two heavyweights was a slow grower, both bands clearing the land by seeing how far out they could push their respective versions of extreme metal. Ascending, then, is the sound of the two bands communicating as one. The immediate standout is “Farewell, Man,” exactly what comes to mind when one imagines what kind of song the Body and Full of Hell could write together. But tracks like “Our Love Conducted With Shields Aloft,” all free drumming, violently humming noise and sandblasted vocals, hint at a broader, uglier horizon.

8. Bad Breeding, Divide (Iron Lung/La Vida Es Un Mus)

One of the year’s nastier hardcore records, and a reminder that the shitstorm at home extends across the Atlantic, too. The band’s got enough chops to rip through every track here - check out that stuttering riff on “Anamnesis,” and how it comes roaring back after a quick respite - but the best songs close each side. The screaming of “Now what?” that concludes “Leaving” is chilling, and serves as one of the best summations of this mess of a year.

7. The Terminals, Antiseptic (Ba Da Bing)

I’ve been hankerin’ for more Steven Cogle ever since that self-titled Dark Matter LP, and if that’s one of your favorite records of recent yore like it is mine, you oughta get your mitts on Antiseptic. The long-running band is absent Brian Crook, but he is ably replaced by Nicole Moffat, who also appeared on Dark Matter; her violin seeps into the empty pores, creating a dense, beautiful atmosphere ripe for Cogle’s powerful vocals. The deal’s done by the time “Edge of the Night” hits.

6. Taiwan Housing Project, Veblen Death Mask (Kill Rock Stars)

Wrecking crew led by Kilynn Lunsford and Mark Feehan brings the heat, here as two parts of a six-piece ensemble. The ten tracks on here range from caustic to catchy (”Eat or Be Eat” into “Luminous Oblong Blur” for the former, “Multidimensional Spectrum” for the latter), accentuated by sax blurts and ever-present static grime. If that ain’t enough, lyrics acidic enough to melt bone make Veblen Death Mask a complete meal worth droolin’ over.

5. Sida, s/t (Population)

The Theoreme LP that came out last year turned into one of my favorites this year, syrupy-thick industrial body music from one Maissa D. She fronts Sida, and she turns in the vocal performance of the year on their first LP. She seemed more restrained as Theoreme but that’s all out the window here; "Qu'Est-Ce Qui T'As Pris?” ups the ante and things don’t slow down from there. The band, for their part, turn in a burly and caustic punk/no wave hybrid that does all it can to keep up. An aural steamroller.

4. Omni, Multi-task (Trouble In Mind)

It was a real mistake to not include Omni’s deceptively catchy debut Deluxe on my year-end list last year, so when they came back and made an even better record, credit is due. Not sure how Frankie Broyles doesn’t sprain his wrist or let melodies go off the rails, but his snappy drumming and spindly guitar work are the stars of the show. The lyrics slyly present a general malaise with modern romance, and when it all clicks, like on “Supermoon” into “Date Night,” strap in.

3. Bed Wettin’ Bad Boys, Rot (R.I.P. Society/What’s Your Rupture?)

Ready for Boredom was a great album full of weary-headed anthems, and it looks like growin’ up hasn’t come any easier for these bedwetters on Rot. The Boys left their glam rock tendencies (i.e., “Sally”) behind this time, and they stick to making gruff pop songs for people whose weeks slip by uneventfully more and more frequently. Songs like “Plastic Tears” and “Device” are urgent and unbelievably catchy, and whoever did the vocals on “Work Again” needs more time at the mic. The Replacements are still a good reference point for these guys, but after two rock-solid albums, it’s time they get to shed that flattering-yet-overbearing label and lay claim to this sound that they’ve perfected.

2. Dreamdecay, YÚ (Iron Lung)

Man, Dreamdecay are so good. They’ve softened the edges from N V N V N V but they’re even more potent this time around, figuring out how to include big slow-moving guitar riffs in a nominally punk framework. Songs like “Mirror” just about leave you on the floor with the guitar theatrics, while “IAN” is a one-way ticket to the stratosphere. All of it sounds incredible, and I think Andrew Earles said it best, so I’ll let him do the honors: “YÚ could easily rearrange how someone thinks about music… in that unforgettable way that stays with the experiencer forever.”

1. Aaron Dilloway, The Gag File (Dais)

What more can I say about The Gag File? I have gushed. Not only a complete statement of an album, but one of the only records to force a localized shutdown when it’s on, keeping everything else at arm’s length. A world unto its own. Clear the cobwebs out.

7″/12″

Anxiety, Wild Life 7″ (La Vida Es Un Mus)

There’s a good bit of cornball humor present in Anxiety’s lyrics and credited band member names, the sort of thing that has persisted/pervaded a lot of modern punk and hardcore. But these guys sell it, and more: with better (read: less juvenile) lyrics, sly and self-deprecating; a monster vocal performance (”Dumped” especially); and a blistering intensity that oughta put their peers on notice.

Bent, Mattress Springs 7″ (Emotional Response)

Bent’s been on my radar since their Non Soon tape, and this year they dropped the Snakes & Shapes LP, every bit the shifting, shambling and at times annoyingly silly experience Non Soon prepped me for. The Mattress Springs 7″ came soon after, and compressed all the best parts of the LP (including “Mattress Springs”) into several minutes of leaky roof drums, hypnotic bass lines and smothered, frantic guitar parts.

Crack Cloud, Anchoring Point 7″ (Good Person)

Whereas Bent are happy to let their songs droop and flow, Crack Cloud come across as almost militaristic in their approach. Perfectly rehearsed, not a hair out of place, and yet as urgent as anything released under the banner of post-punk in the past however-many-years. The first three jagged and dense tracks whip in and cut out, just in time but somehow just too soon; “Philosopher’s Calling” is the payoff.

Hothead, Richie Records Summer Singles Series 7″ (Richie)

The Richie Records Summer Singles Series once again distinguished itself in a household where 7″s aren’t really given the time of day. Sure, Writhing Squares Too breathed life into krautrock in 2017, and David Nance’s "Amethyst” is kingdom come on the right day, but Hothead? Their shambling take on two covers (and a quick sketch) netted them the gold.

Mordecai, What Is Art? 7″ (Sophomore Lounge)

Mordecai is one of America’s great treasures, ain’t no way around it. Their Abstract Recipe LP on Richie from this year is great, reclaiming the highs of Neil’s Generator while pushing further from their influences - but the two disparate sides of this 7″ compress everything great about the band into a tidy package. The A-side rambles out of the gate in the same way Abstract Recipe does, whereas the B-side goes all Don Howland: low fidelity, downtrodden but toe-tapping. Buy everything they’ve recorded.

Mutual Jerk, s/t 7″ (State Laughter)

“He’s really a nice guyyy” begins the A-side track “He’s Harmless,” and hoo boy you better sit down for this one, because that bass line is not quitting anytime soon. Feeble excuses pile up, a disinterested defense of a friend presented with a mocking snarl until the constant pummel causes the dam to burst. The flip cynically covers comfortable suburban lifestyles and macho hardcore, two new takes on No Trend's vast influence, but not quite reaching the impossible heights of song-of-the-year “He’s Harmless.”

Neutral, När 12″ (Omlott)

Neutral’s self-titled LP quickly turned into a favorite here in the early months of 2017. The duo kept busy all year, eventually releasing this mini-LP that favors electronics over guitars. The brittle backbone is the perfect support for Sofie Herner’s fragile yet mechanical vocals, a fitting soundtrack for a walk home so cold your eyelashes freeze. Shadow music that lacks a distinct time or place but leaves a flood of sensory overload in its wake.

Scorpion Violente, The Stalker 12″ (Bruit Direct Disques)

“The Wound”’s slow ooze remains one of my favorite musical moments of the year; there’s a reason it’s the only one you can’t stream via Bandcamp. Pay up, because if any modern label deserves your money, it’s Bruit Direct Disques.

The Shifters, “A Believer” b/w “Contrast of Form” (Market Square)

Brilliant little single of downer pop from the Shifters, whose self-titled cassette gained them a lot of Fall comparisons and was previously mined for a 7″ by It Takes Two. But it looks like they’ve got ambitions beyond the record nerd cadre: both songs are immediately satisfying without imparting a sticky sweetness - who can find fault with that?

Straightjacket Nation, s/t 12″ (La Vida Es Un Mus)

This is the punk record of the year for me, one that maybe got lost in the deluge of releases from La Vida Es Un Mus. If you wanna learn about effective vocal delivery in hardcore, please see “2021.” Eight tracks, all meat. Please tour the US.

Reissue/Archival

I don’t really feel too qualified to comment on music largely made before I was born, especially since I am the owner of several 2017 reissues with flowery press kits that I will probably never listen to again. But if you’re gonna be a sucker, let a sucker clue you in to these tried-and-true slabs deserving of any and all accolades. Unrepresented here, somewhat criminally, is the Black Editions, a label doing really amazing work reviving the P.S.F. catalog.

The And Band / Perfect Strangers, Noli Me Tangere split 7″ (Look Plastic/Noisyland)

Noli Me Tangere is two sides of barely-music from early ‘80s Christchurch, with this new edition featuring extensive liner notes from George Henderson, he of the And Band (and perhaps more recognizably, the Spies and the Puddle). Both sides showcase a coupla outcasted NZ bands supporting each others’ avant-scrawl, as inspirational as it is baffling.

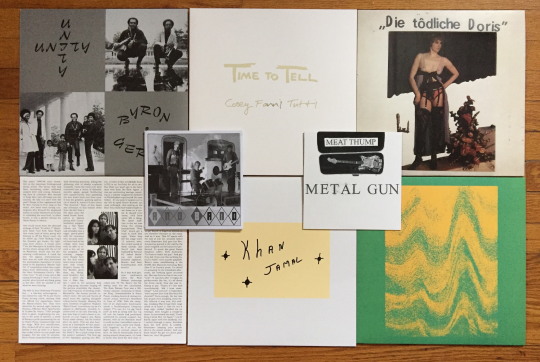

Byron Morris & Gerald Wise, Unity LP (Eremite)

Freedom music, full of raw intensity (”Byard Lancaster did push-ups when not playing”) and fiery exchanges. The two sidelong pieces are demanding of your full attention, repaid in kind with chills so deep you’ll swear a spirit passed through ya.

Cosey Fanni Tutti, Time to Tell LP (Conspiracy International)

Gorgeous reissue with a foil-stamped gatefold and a huge booklet full of ephemera from the recording period. Less Throbbing Gristle menace than new age shimmer, especially on the B-side; the gentle ascent is the natural conclusion once you’ve lived through the stunning title track. Cosey, take me away.

Die Tödliche Doris, “ “ LP (États-Unis)

Brutally minimalistic post-punk from early ‘80s Germany, painstakingly restored by the Superior Viaduct sub-label États-Unis. The A-side is full of blistering, manic bursts; the flip smoothes things out, allowing ideas to stick around, proving this approach works in both short- and long-form. Call it ZNR meets DNA.

Harry Pussy, A Real New England Fuck Up LP (Palilalia)

Two live sets, one on each side, both monstrous and in shockingly high fidelity, especially given the circumstances detailed by Tom Lax and Tom Carter on the sleeve. The show from T.T. the Bear’s is the performance I always want (”Harry Pussy took the stage and sandblasted the night into oblivion”) and rarely get.

Khan Jamal Creative Art Ensemble, Drum Dance to the Motherland LP (Eremite)

Capping off a brilliant year for Eremite was a beautiful reissue of Drum Dance to the Motherland’s cosmic transmission. All of the hyperbolic reviews ring true when “Inner Peace” stumbles into a groove, but my favorite part is the almost painfully shrill horns on the title track.

Meat Thump, “Metal Gun” b/w “Left to Rust” 7″ (Coward Punch)

Coward Punch Records kept the memory of Brendon Annesley alive with a couple of archival Meat Thump 7″ers this year. The earlier one was good, but didn’t quite hit home; here, “Metal Gun” could be twice its length, and “Left to Rust” rambles down my spine in the same way that still-great “Box of Wine” 7″ does.

V/A, Oz Waves LP (Efficient Space)

I did not have more fun this year than when I was dancing along to this record like a poorly operated marionette, which was every time “Will I Dream?” started. Efficient Space continues to deliver the goods I didn’t know I needed.

#Mount Trout#Group Doueh#Cheveu#Leda#The Body#Full of Hell#Bad Breeding#Terminals#Taiwan Housing Project#Sida#Omni#Bed Wettin' Bad Boys#Dreamdecay#Aaron Dilloway#Anxiety#Bent#Crack Cloud#Hothead#Mordecai#Mutual Jerk#Neutral#Scorpion Violente#Shifters#Straightjacket Nation#Cosey Fanni Tutti#Harry Pussy#Quelle Chris#Starlito#Shy Glizzy#Khan Jamal

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Name Of The Doctor - Doctor Who blog

(SPOILER WARNING: The following is an in-depth critical analysis. If you haven’t seen this episode yet, you may want to before reading this review)

I remember at the time there was a lot of panic within the fandom. The Name Of The Doctor? Oh God! He wouldn’t! Is Moffat actually going to reveal the Doctor’s real name?! Heresy! Sacrilege! The end of Who is nigh!

Looking back with the benefit of hindsight, I recognise that was just silly. Of course Moffat isn’t brave enough to reveal the Doctor’s real name. He’s stupid enough, but he’s not brave enough. And in some ways that provides a small comfort. While The Name Of The Doctor is without a shadow of a doubt the worst series finale in the whole of New Who, at least the Doctor’s name has been left untouched.

So the Paternoster Gang, Clara and River Song (yes she’s back again. Sigh) meet up via a hallucinogenic trance to discuss the Doctor. Because it’s always about the Doctor isn’t it? And I want you to bear this in mind as we continue.

So some gibbering serial killer has revealed that ‘the Doctor has a secret that he will take to his grave, and it has been discovered.’ This is soon revealed to be yet more of Moffat’s pretentious bollocks because it turns out the grave has been discovered, not the secret. So why didn’t the serial killer just say ‘the Doctor’s grave has been discovered’? And how the fuck does he even know about it anyway? Did the Great Intelligence tell him? Why didn’t the Great Intelligence talk to the Paternoster Gang directly if he wanted to lure the Doctor to Trenzalore?

This leads me to quite possibly the only thing about this episode I actually liked. The Whisper Men. They never give an explanation for where they came from, but I like them. They’re very creepy. At least at first. Unfortunately as the episode goes along, their threat is diminished dramatically because all they ever seem to do is just stand around hissing at people and spouting stupid nursery rhymes. Also they kill off Jenny, which made me sit bolt upright in my seat as I realised that the characters are actually in danger for once, only for Strax to magically bring her back to life with his remote control. So what was the point of that?

So off we go to Trenzalore to visit the tomb of the Doctor. I have several problems with this. For starters, I really don’t want to see the Doctor’s grave. I think in Moffat’s zeal to massage his own ego and pull the rug out from under our feet, he’s now at serious risk of stripping too much of the Doctor’s mystery away. Also I get why the Doctor would be reluctant to find out where he dies, but how can he possibly avoid information like that? He’s travelled to so many places and helped so many people to the point where he’s become one of the most well known people in the universe. He’s in recorded history. Surely he’s bound to come across the date and circumstances of his own death at some point whether he wants to or not. Besides, haven’t we done this already in Series 6? Why are we doing this again? And if the Doctor was always destined to die at Trenzalore, why bother killing him at Lake Silencio? And if him dying at Lake Silencio is a fixed point, how could he possibly die at Trenzalore? This makes no sense.

Still, at least Trenzalore is nice to look at. There’s some gravestones and a giant TARDIS. Then it gets ruined by yet more Moffat idiocy. Who put the River Song grave secret entrance there? They never explain that. And if this is post Library River Song, I’m not 100% sure how she can be taking part in the Paternoster Gang’s ‘conference call.’ Nor how she and Clara can be communicating with each other when it’s been firmly established you need to be unconscious to make the conference call. I certainly don’t get how in God’s name the Doctor is able to talk to her at the end when he hasn’t even had a whiff of hallucinogen. Truth be told, I haven’t the faintest idea why River Song is even in this. She’s basically there to open the tomb because she’s the only person who knows the Doctor’s real name. Moffat’s ego working overtime yet again. It’s funny how Moffat likes to make fun of RTD’s obsession with Rose when his obsession with River is infinitely worse. I mean I wasn’t too fond of Rose neither, but credit where it’s due, at least Rose was a three dimensional character. River is nothing but a Mary Sue who always has to be better than the Doctor at everything and yet displays no actual character or agency of her own. The fact she apparently made the Doctor tell her his name should tell you everything you need to know about Moffat’s mindset as a writer. The Doctor didn’t tell her because he trusted her. She made him. She’s always the one who has to have an advantage over the Doctor, the title character, because she’s Moffat’s special creation and he wants her to be oh so important without putting in the effort to properly justify it. Plus she’s not really that strong or independent because, like every other female character Moffat has ever written, her life still utterly revolves around the male protagonist. At least one silver lining we can draw from this episode is that it looks like River Song might finally be gone for good at last. Thank God.