#but also the person who made her publically anti Church teaching

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

.

#i am literally so torn on how to feel about Luce#cause on one hand she's super cute and has a lot of potential to help bring people to Christ#but also the person who made her publically anti Church teaching#and as Catholics we should support Catholic artists who are like actually catholic#especially if they are making something for the Church to use in a public manner#I was waiting for the other shoes to drop from the moment I saw her#cause we really can't have nice things#every cake we bake gets dropped face down and stomped on

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 26: Rocky V

(previous notes: Rocky IV)

A fifth Rocky movie if you can believe it! I saw this in the theater when it came out in 1990. My movie appreciation had become exponentially more sophisticated since the previous movie, but I remember thinking that they were going for something less formulaic when they came out with this. They even brought back the Oscar-winning director of the original Rocky, John Avildson. And surely this character was way too old to still be able to win fights against professional boxers, right? I must say, I don't remember what the story of this movie is.

The intro does a brief throwback to the original name-scroll-plus-fanfare, but now we're showing a recap of the previous movie's final fight during the credits, which promise an appearance by no less than Burgess Meredith.

Do you think there was a conversation where Sylvester Stallone condescendingly told Avildson, "hey, trust me, start the movie with three and a half minutes that is just the end of the last picture, easy money baby, cha-ching ya know?"

The story begins immediately after the Battle of Cold War Symbolism, and we see that he is experiencing physical trauma as a result of Soviet Boxing Technology.

Then we see that they had the idea to introduce a Don King-type character, a really irritating boxing promoter blindsiding him in public to get on his case about a new challenger. Do you think the promoter character will have a nuanced arc.

After a chill father-son catch-up chat, there's an awkwardly-blocked expository scene about how Paulie made some stupid mistake and got tricked into signing away millions of Rocky dollars to a sinister accountant. And then he goes to the doctor who tells him he has irreversible punch damage and can't fight any more. Conflict is looking dire. Do you think Robot Character will arrive soon to cheer us all up.

After selling all of their possessions at an auction, Rocky goes to his old hangouts. He leaves the corner bar looking defeated. They don't show how he was defeated in the bar, but that bar clearly humiliated him.

Then he goes to the old gym, and here's where we have a flashback scene of Burgess Meredith giving him a pep talk. It's kinda nice. But it still feels like we're at the point in the story right before the tide turns and suddenly Rocky is inspired to become supernaturally good at boxing once again. But that's not gonna happen; we're just twenty minutes into the movie.

Rocky has to move back into his old neighborhood. It's dirty and run down, and people gawk.

0:32:00 - For the third time in this movie, Rocky tries to charm his family with a LOOK WHAT I PULLED OUT OF YOUR EAR gag. The characters are barely charmed by this gag. We, the audience, are way way way less charmed.

Fake Don King is buzzing around a lot. He is a dick and he is annoying to every single person alive. It's effective at driving the conflict because he is so persistent at needling Rocky into maybe fighting. But the acting is cringey. Kinda the point, though, right?

Just like that, the old gym where we saw the flashback, which was abandoned and run down, is open for business and full of people. How did that happen?

0:43:30 - Okay now it is me - Zawmer! - who is about to be an unappealing bad guy because I must now report how little tolerance I have for this scene with two child actors. Rocky's son, who got bullied at school earlier, is having his first maybe-we-fancy-each-other conversation with a girl. The dialogue has no chemistry with these kid actors.

I should mention that there is a character named Tommy Gunn. He is a spirited young boxer who has found Rocky and wants Rocky to help him. He is bemulleted and earnest and good-punch-y.

Rocky is going to manage Tommy, but his son wants some attention. Feels like an artificially manufactured conflict. Plus the dumb bullies at school beat him up again. It is hard being the newly-poor child of Rocky Balboa.

0:53:25 - I probably wouldn't have caught this if I hadn't watched the first movie kind of recently, but we cut to a fight, Tommy is fighting someone and it's in the same church that started the first movie. He wins that fight and it becomes a montage of Tommy becoming increasingly successful under Rocky's coaching, plus there is evidence that Rocky's son is trying to get his dad's attention by using some of the gym equipment.

It does seem like it would be fun to make boxing-improvement montages.

Oh, the kid learning boxing was so he could get back at the bullies. Mission accomplished but he clearly thinks his dad was supposed to be even nicer about that, even though he was kind of nice. But he was in the middle of something with Tommy, I mean, come on!

Ooh, and that was just a brief interruption in the boxing-improvement montage, it keeps going. This movie is pretty generous with fun montages.

The falling out scene between Rocky and Kid is not better than a similar scene in an after school special. And it's way worse than that one anti-drugs commercial we all remember, "I LEARNED IT FROM WATCHING YOU"

Oh, but then Kid runs away and starts hanging out with Ivan Drago! Drago starts teaching him how to beat up his dad, and says something about "If he die, he die". No. No he doesn't. That doesn't happen. I was just getting a little bored there. What's true here, what's actually true, is that Kid's increasingly rebellious personality has yielded a very, very stupid looking ear chain. It is an earring… with a chain hanging off it at the exact perfect length for no human being to think it looks good. The length of that chain is the chain-length equivalent of the amount of time that Talia Shire closes her eyes that one time.

A new conflict emerges where Tommy is going to sign with Fake Don King. It turns out Rocky had no interest in making any money. You can't blame him really. Rocky's all "don't sell out". But. Dude.

Okay so Tommy Gunn, having divorced Rocky and married Fake Don King, wins the title fight and becomes the new champion. The crowd boos, and they also cheer "Rocky". Rocky is not there. Rocky is watching the fight on TV in the basement and also punching a thing because he can't help it, but the crowd at the fight is like "Rocky" and "boo". I don't quite get it.

This press conference is kind of clearing it up, see, no one thinks it was a legitimate fight, it seemed fakey. There is pandemonium and insultation! It is clearly building to some silly insistence that he, Tommy, should fight Rocky.

Tommy shows up at the bar and he's hopping mad because he ain't nobody's robot and will you accept my challenge Rocky! Fake Don King thought this would turn into an actual arena event, but it's turning into just a back-alley fight like in that Fight-y movie about that Club.

It escalates thusly. As Rocky endures cinematically beautiful flashbacks to fights from earlier movies, they punch each other beneath rumbling trains. I sound mocking but some of it is pretty visually interesting.

Interesting enough to serve as an abstract explanation for how, once again, Rocky is supernaturally good at punch-game. It may be a street brawl this time, and we may have to do without Adrian closing her eyes Just So, but once again the Rocky movie ends with him winning the fight and everyone being very very excited about that. He punches Fake Don King because of how smarmy he is, and even the priest is delighted.

There is a denouement of Rocky and Kid bonding genially by the famous steps, and then the credits roll in front of touching stills from all five movies, and an Elton John song that didn't have as much cultural impact as some other songs we've heard recently.

I guess I like the montages and the quick cinematic choices that are to be found here and there in these movies, but mostly when I think back on them it seems like they are arrangements of familiar modules. In this one, the modules were held together with more flimsy material. I was wrong to think that this movie would be less formulaic. Soon I am done with this project. Soon. SOON.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

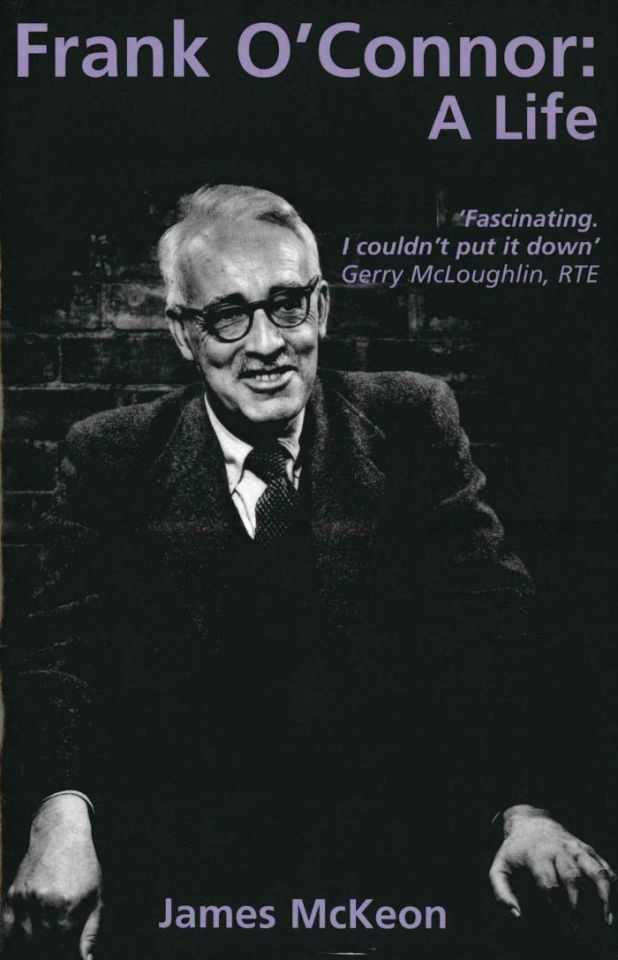

National Heritage Week | Frank O’Connor – Librarian

by Jim McKeon

Writer, Frank O’Connor, was just twenty years of age when he was released from Gormanstown Interment Camp. Cork had been badly hit by the Civil War. It was still a smouldering ruin. Because the city and county had been the focal point of much of the bloodiest fighting the turmoil of the Civil War lingered there longer than it did elsewhere in the country. In the spring of 1924, the city was still edgy. O’Connor had no money and no job. Under the new government all teachers were required to learn the Irish language. For a few months he taught Irish to the teachers at the Protestant school in St Luke’s Cross, near his home. He was paid a few shillings a week for this. He struggled by, a twenty-year old in his father’s patched up, old hand-me-down trousers teaching middle-aged teachers how to speak the Irish language. It was frustrating, especially if you were on the losing side in the Civil War. MacCurtain and MacSwiney had tragically died but he still met Corkery and Seán O’Faoláin regularly. As so often before Daniel Corkery, forever in O’Connor’s background, stepped in and arranged an interview for a job. Cork dramatist, Lennox Robison, who was secretary of the Carnegie Library, was organising rural libraries and he was looking for young men and women to train as librarians. After a tough interview O’Connor got the job. His mother packed his little cardboard suitcase, including a big holy picture of the Sacred Heart, and he set off for Sligo.

Bust of Frank O’Connor - on display in the City Library, Grand Parade

At last he had enough books to read. Even for 1924, the wages were poor, thirty shillings a week. His lodgings were twenty-seven and sixpence. He had a half-crown (12.5 cent) left for cigarettes and drink. He posted his dirty laundry on to Cork every week. His mother washed it, with unconditional love, and posted it back, and sometimes included five shillings for her son. As a librarian he was all hands. His boss said he was untrainable. He kept busy by reading poetry books and getting them off by heart. He was blessed with a phenomenal memory. The only thing of note in Sligo was that he celebrated his twenty-first birthday far from home. After six months he was sent to Wicklow, where a new library was to be opened.

When he arrived a local priest wanted to close down the library. Lennox Robinson had just been heavily criticised and fired from his library position because of a controversial story he wrote about a pregnant girl who felt she had mysterious visit by the Holy Ghost. O’Connor’s boss was Geoffrey Phibbs, an influential fellow poet with controversial opinions on many aspects of life. The two young poets became great friends. Phibbs escorted O’Connor to Dublin and introduced him to Lady Gregory, George Russell (AE) and Yeats. AE was editor of the Irish Statesman and encouraged O’Connor to send him on something for publication. He sent a verse translation of Suibne Geilt Aspires and when AE published it 14 March 1924, it carried for the first time the pseudonym Frank O’Connor. It must be remembered that he was a young civil servant and he may have been contemplating on keeping his job by using a pen name ever since Lennox Robinson’s enforced resignation. He chose his confirmation name, Francis, and his mother’s maiden name, O’Connor. The prominence AE and the Irish Statesman gave him thrust him into literary view. Yeats had great time for O’Connor and said that he did for Ireland what Chekhov did for Russia. But the young librarian missed home and his mother. A vacancy came up in Cork. AE tried to talk him out of it and warned him he’d be miserable back in Cork. It never occurred to O’Connor that he would not return home. Like his father he was, at that stage, a one-town man..

Notwithstanding AE’s forebodings, he accepted the job of Cork’s first county librarian in December 1925. He was just twenty-two years of age. His salary of five pounds a week was more than anyone in Harrington’s Square had ever dreamed of earning. The library was at twenty-five Patrick Street which was still in the process of being rebuilt. Minnie was happy that her son was back home again and his father, Big Mick, was impressed that a pension went with his son’s new job. The city was still in a poor condition. The foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922 augured a period of new confidence in Cork. But in 1924 a public inquiry found:

…limited progress had been made on rebuilding Cork’s city centre since it had been burned down in 1920. Criticism was made of the poor quality of maintenance of the city streets, many of which were still paved with timber blocks. Part of Anderson’s Quay had fallen into the river. The public water supply was of poor quality…There was virtually no building in progress in the city.

In the burning of Cork not alone had many of the character and physical structures of the city been lost, but so also had thousands of jobs and many peoples’ homes. The Cork Examiner reported that thousands were rendered idle by the destruction. The rebuilding was tediously slow mainly because of the shortage of funding. Britain’s refusal to accept blame and pay compensation didn’t help. The Civil War itself and the post-war political divide were also major factors in delaying the building progress. This was another chapter in Frank O’Connor’s Cork, a damaged city struggling to survive. He opened his library over a shop near the corner of Winthrop Street. It was five years since the burning yet major buildings, just yards away, like Roches Stores and Cash & Co, were still rubble. Rebuilding had not yet started in these two well-known shops. In January 1927, Roches Stores finally re-opened for business. Summing up, the burning of Cork had a unifying effect on a people that had been collectively damaged by the event. It also exposed divisions in Cork society at the time. A Church/political divide came to the surface during this traumatic time. It was demonstrated through criticism by councillors of Bishop Coholan for his refusal to condemn the burning. Many republicans were unhappy because they felt the clerical comments were often selective. Frank O’Connor had a huge responsibility for a young and inexperienced man. He was given a cheque for three thousand pounds to set up and stock his library. He made his first mistake. At that time an anti-Catholic bias still lingered in commerce. He naively lodged the cheque in the nearby and more practical catholic bank when the accepted practice was to use the protestant bank. This innocent action caused a major committee dispute and O’Connor was accused of having a personal and ulterior motive. Then, when he insured the building, the insurance company gave him a cheque as a personal thank you. He didn’t want it and kept it for years but never cashed it. He sums up this whole chaotic scenario:

By the time the Cork County Council had done with organizing my sub-committee it consisted of a hundred and ten members, and anyone who has ever had to deal with a public body will realize the chaos this involved. Finally I managed to get my committee together in one of the large council rooms, and by a majority it approved my choice of bankers. There was, I admit, a great deal of heat. Some of the councillors felt I had acted in a very high-handed way, and one protested against my appearing in a green shirt – a thing which, he said, he would not tolerate from anybody.

When he finally got his stock of books together and organised his new library, he decided that he should have closer contact with the rural community. If they couldn’t come to him then he’d go to them. He bought a van, packed it with boxes of books, and drove all over the county. After six months this affected his health. He was exhausted from working long hours driving all over West Cork and he wrote almost every night. In a letter to old Wicklow colleague, Phibbs, he wrote, I’m working like a brute beast. He became ill and had to have a serious operation in the Bon Secours Hospital. He spent two weeks in hospital and six weeks convalescing. It shows his stubbornness when he shocked the nuns in the hospital by refusing to receive the sacraments before the operation.

Cork had a long tradition of theatre and a critical play-going audience, but in 1927 there was only one drama group in the city, the newly formed Cork Shakespearian Company. Daniel Corkery’s little theatre had closed in 1913 and groups like Munster Players, Leeside Players and Father Matthew Players were also defunct. On 8 August 1927 Micheál MacLiammoir and Hilton Edwards brought their touring company to Cork. They performed The High Steppers’in the Pavillion Theatre in Patrick Street. This venue later became a cinema and is presently HMV music shop. After the opening night there was a party at Seán and Geraldene Neeson’s home. Geraldene was Terence MacSwiney’s bridesmaid when he married in England. MacLiammoir encouraged O’Connor to revive drama in Cork. O’Connor was inspired and was instrumental in forming the Cork Drama League. Although he knew nothing about drama he threw himself headlong at the project. Old friend, Seán Hendrick, recalls:

That Michael knew nothing about producing plays and I knew nothing about stage-managing them did not trouble us at all…The producer was to be given a free hand in the choice of both plays and cast and members were bound to accept the parts allotted them. There were to be no stars and an all-round uniformity of performance was to be aimed at.

Undaunted, Frank O’Connor tore into their new venture. Lennox Robinson’s play, The Round Table, was to be the first production. It was its first appearance in Cork and there were some slight adjustments to suit the local audience. The curtain-raiser was Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard. Typically, O’Connor wrote the programme notes, directed The Round Table, and appeared in both plays. The Round Table was a difficult play to produce. It had fourteen characters. Many of them doubled up and played two roles. They had trouble trying to cast the part of Daisy Drennan, but one night Geraldine Neeson brought along a pretty young girl to audition. Although she had a terrible stammer she was a natural actress. Not alone did she get the part but that night O’Connor walked her home. From then on Nancy McCarthy became his leading lady and for years to come she was to flit in and out of his life. The company’s first play opened on 28 February 1928 in Gregg Hall in the South Mall, a theatre venue no longer used in Cork. They got high praise all round especially Nancy McCarthy. They immediately started rehearsing for their second venture, The Cherry Orchard. Cork City was now back on its feet and completely rebuilt and people were getting used to a new freedom and sense of safety. Theatre was a hugely popular event. Plays at that time generally had an Irish theme and written by the likes of Yeats, Synge, Robinson and T. C. Murray. That had been the custom and they were very popular with Cork audiences. But the young Frank O’Connor had other ideas. He was into French and German and Russian theatre and he wanted to offer the Cork public something different.

English drama, no matter how significant it may be in its own setting can have no beneficial effect upon a country which is subjected to cultural influences only from one source. The Cork Drama League proposes to give the best of American and continental theatre, of Chekhov, of Martine Sierra, of Eugene O’Neill and those other dramatists whose work, as a result of the dominating influence of the English theatre, is quite unknown in Cork.

That was a more than subtle dig at Fr, O’Flynn, a local priest, who had founded the Cork Shakespearian Company in 1924. The two men did not get on. From 20 December to 30 December1927 they exchanged four letters in the Cork Examiner trading insults. Fr, O’Flynn signed his letters The Producer while O’Connor used his name in Irish. Seán Hendrick joined in the attack calling himself Spectator. Everyone in Cork knew who both men were. Ironically, they were more alike than they cared to admit; they were two proud Cork men, they both loved Shakespeare and they both loved Irish. Two more plays were produced, The Cherry Orchard and A Doll’s House. Both got fine reviews, but the audiences were poor. Maybe the Cork Drama League was going too far too soon, and Cork wasn’t ready for them. By now O’Connor was spending most of his time with Nancy McCarthy. Nancy was a religious girl from a well-known Cork family. He brought her home to see his mother and the couple went on a three-week holiday to Donegal. They stayed in houses three miles apart. They met every day for a year outside of St, Peter and Paul’s church after mass. They were engaged for a while but it did not work out. She would not marry him. He would not marry in a Catholic church and there was no way Nancy would marry outside the Church. She was one of ten siblings and he was an only child. She felt he was spoiled. This was quite true. By now he was being regularly published in the Irish Statesman. He had a poem dedicated to Nancy published 9 May 1928. The last two lines are filled with melodrama:

That even within this darkness of our body keeps

Communion with the brightness of a world we dream

Frank O’Connor was beginning to feel that AE was right. He should never have left Dublin. He was no longer enjoying his years in Cork. It was no longer the place he had known. O’Faoláin was in America and recently he had found it difficult to talk to Corkery. He made it plain that he was taking sides and that O’Connor was on the wrong side. O’Connor was restless and felt that Cork was threatening to suffocate him. He missed Wicklow where he could talk literature and art to Phibbs and go on to Dublin to meet AE and Yeats. AE would give him all the latest books and gossip, and Sunday evening he could go to the Abbey Theatre and see a series of continental plays, Chekhov, Strindberg and contemporary German plays. Eventually, getting frustrated with the parochialism of Cork and his lack of success with Nancy McCarthy, he applied for the job as municipal librarian in Ballsbridge. On Saturday 1 December 1928 he packed his case and left for Dublin. He still felt it was only a temporary move. Nothing could cure him of the notion that Cork needed him and he needed Cork. Nothing but death could ever cure him of this.

Jim McKeon’s book Frank O’Connor: A Life is available to borrow from Cork City Libraries

Jim McKeon has been involved in theatre all his life and has many film scripts, plays and books to his name. His best-known work is probably the biography of Frank O'Connor. He also toured Ireland and the US with his one-man-show on the writer's life. Jim is also an award-winning theatre director and poet.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have a silly Napoleon ask for you: if he suddenly woke up in the present day what do you think he would a)like most about it b) like least about it c)get unreasonably addicted to d)decide to do for a living

hahah I’ve answered a similar one before here and here.

Most Like About It: A lot, I think. Central heating. Guys, he’d fucking love central heating.

In general, he’d love most technological advances. Cars, planes, trains etc. like he’d be very into that. “Bertrand we’re going to ride the TGV all day every day. Look at how fast we are going! This is genius.”

“Bertrand WE ARE IN THE SKY. This is AMAZING. We are going from Paris to Rome in a matter of HOURS. HOURS BERTRAND. WE DON’T HAVE TO CROSS MOUNTAINS.” (sorry just assuming this is exile Napoleon who woke up in modern day.)

Public transit in general - the metro, buses - anything that makes life more efficient for people. Dishwasher, washers/dryers, modern electricity, laptops, printers, ball point pens etc.

I suspect he’d be a big supporter of public health care and all the advances made on vaccines and medicine in general. 100% would hate anti-vaxxers. Pro-modern glasses (he’d get himself a pair asap. Then they’d explain contacts to him and I think he’d be like “WAIT NO, I WANT THOSE.” He would not be into lasik, I suspect).

Modern hygiene! Razors, tooth brushes, floss, moisturizer - general daily body care he’d probably be keen on. (All that stuff we take for granted.) Though maybe not all of it, he was quite traditional in certain things (his penchant for older fashion, par exemple). Maybe he’d keep the old straight razor shaving approach. But modern dentistry would be a huge improvement and I can’t see him being against it. Especially as someone who had a tooth extracted in the early 19th century.

‘Oh they give you pain killers now? Fantastic.’

‘Sir, we just numb the area where we are doing the work.’

‘So it doesn’t impede my awareness? Amazing. Please, fix all my teeth right now.’

He’d also support the greater access to education that exists, especially compared to his day. Also, streaming services. He would binge so many things. ‘Bertrand we are watching every thing this very soothing sounding British naturalist made about planet earth. Holy shit look at that they’re under water! They’re at the bottom of the ocean! Bertrand look at this. if only Josephine were here. She’d be so excited.’

Pro-zoom/Microsoft teams/facetime etc. 100%. ‘If I had this instead of people relying on my bad handwriting ...’

Oh, he’d like the EU as a concept. Except he would be very disappointed that France wasn’t at the helm. I think France’s position globally would disappoint him, overall. But yeah, the broad principles espoused by the concept of the European Union would appeal to him.

Brexit though. Lol. I think he’d enjoy watching England shoot itself in the foot. But if you asked him for his opinion, as in “do you think the UK should do this” he would answer no. They should remain.

He would like globalization, trade agreements, things like NAFTA, CETA etc. Supporter of big government. Reduction of religion in public sphere. Though would he be pro-banning visual manifestations of faith? (i.e. Hijab etc.) I don’t know. I doubt it. Simply because he was very focused on religion in government, so if churches aren’t involved in decision making, what citizens get up to on their own is their business (so long as you don’t cause problems). But I don’t know, he might be pro-it, because he was also into assimilation and creating a broad sense of a French culture. I could see him really going either way on it. It’d probably come down to whatever he thought would garner the most public support as a political move (since a lot of his more liberal moves as a leader were tied to understanding that marginalized communities would gun hard for him if he helped them).

He would be pro-mask wearing for COVID because he wasn’t a fucking idiot and lived in a time when pandemics were still a real going concern.

He would also probably like how comfortable modern clothing is. I don’t think he’d like how cheap and made-to-wear-out that most brands are, but he’d like the over all philosophy. Like Napoleon would dig t-shirts. Lounge wear. The fact that jeans have some stretch in them. That sort of thing.

--

Least Like: I think he’d be very wary of the internet. For many reasons. For the lack of government control (Napoleon “What is a free press? never heard of her” Bonaparte). But also, because of the misinformation problems. The side effects many of us are now bearing witness to, and experiencing the ramifications of.

He would dislike the whole fake news nonsense. Oh this man was a master spin-doctor, very good at twisting a narrative around to suit him, but he still did have respect for and a firm belief in basic facts. Especially fake news that usurped the sound advise of scientists and doctors (i.e. COVID nonsense).

Free press, I think he would be wary of it. Mostly from a government control perspective. Like as a day-to-day citizen, since he wouldn’t be anyone in power in this hypothetical, I think he’d value it. He would do that disassocative thing he did when he talked about things in the abstract. That cold, calculating way he would position himself in a situation and be like “Ah yes, these are the things that need to be tamped down if you want control of a populace as a monarch”. Then he had his more liberal, call-back-to-that-misspent-jacobin-youth moments where his views shifted.

I suppose it would also depend what age this hypothetical Napoleon is. He softened a lot in retirement exile. Napoleon at the height of his power, thirty-odd years old, different man to fifty year old Napoleon.

Would not be into women in politics. He’d be like ‘Why is there a woman in charge of Germany? Also what happened to the Habsburgs? Where’s Prussia? Silesia? What the FuCk is happening in the Balkans? I’m very confused about Europe’s current geographic layout. ...Corsica...still doing you, I see.’

He’d dislike Trump and his cronies. As I wrote before: “ I think Napoleon would find Trump disgusting on a personal level. Uneducated, incapable of holding a real conversation, gauche, anti-intellectual, anti-fact-based discussion, anti-science, anti-art etc. He’d also feel that Trump is disgracing the position of President and that he is unworthy of leadership. Napoleon would also find Trump physically repulsive as he could be a wee bit shallow in some of his assessments (though, very early modern to 19th century to assume your physical appearance is a manifestation of your interiority).”

Steve Bannon’s fiddling with finances? Napoleon would find that repulsive. Mitch Mcconnell disgracing his office by fucking around with constitutional loop holes? Napoleon would think it a disgrace.

He had a lot of respect for America’s experiment with democracy. Like, quite a lot of respect. So I think he’d be vastly disappointed in not only the person occupying the white house, but also a lot of the apathy in voting that is going around. (Yes, this coming from a [mostly] absolutest monarch, too.) But Napoleon valued and respected the notion of civic duty. If you live in a democracy, you have a duty to participate. To opt out is to shirk that duty which he would find insulting and distasteful. Because, I would argue, he was very much a believer in people doing right by their fellow citizens.

--

Get unreasonably addicted to: MODERN BATHS. HE WOULD NEVER LEAVE THE BATHTUB. THEY CAN HAVE JETS AND EVERYTHING BERTRAND THIS IS GREAT.

Also central heating. Saunas. Jacuzzis. He was like a wee lizard seeking warmth at all times.

I think he’d be into driving. I don’t know if he would be good at it. Don’t let Napoleon take the wheel, guys. But if someone else was driving he’d be that person “go faster. you’re driving like my grandmother.” And gods, he’d do dumb shit like drive like a maniac around the arc de triumph six times in a row because he’s an adrenaline junkie and a risk-taker (it’s that bored ADD brain of his). The autobahn would be his dream.

I think he’d be super into epic fantasy series. Like the big sweeping ones like Lord of the Rings. I think less so GRRM because GRRM is unrealistic and Napoleon is pedantic. Especially about politics and war. Exhibit A: consider Napoleon’s very detailed nitpicking of Virgil on his inaccurate rendition of Troy from a military perspective. Therefore, I suspect GRRM’s lack of accuracy in how society works, how war works, how politics works, all the plot holes and illogical character decisions, would drive him up the wall. Napoleon liked Homer because he could tell Homer had been to war. And you can tell Tolkien has been to war. Also LOTR hits all those notes of high-hearted emotion and big sweeping scenes that Napoleon so liked in Ossian and the Illiad etc.

All this to say, overall, as a genre, I think those big, sweeping fantasies with lots of plot, politics, intrigue, soaring battles, great heights of emotion - he’d love that. It would hit all of his buttons for what he liked in fiction. Lots of emotion, lots of action, lots of big scenes, lots of crazy shenanigans. This can also be applied to Sci-fi. I think he’d be a big nerd on that too. But the science would have to make sense.

I think he’d be into Star Trek, particularly Picard, if only for the philosophical aspects of it. He liked those sorts of questions and hypotheticals. So I think he’d binge all of The Next Generation (among other seasons).

--

Do for a living: Teach? God knows. This is Napoleon from 18-something who just woke up? He could be paid for consultant work for historians and film crews and the like, I guess. Just to tell them how accurate stuff is. Of course, be wary, this is Napoleon I Am A Spin Doctor Bonaparte.

I think he could lean into writing histories - particularly the classics, early French and European history - that sort of thing, where he already has a strong background in it and it wouldn’t require him basically learning an entirely new trade. Like, will Napoleon ever fully be a natural with computers and cell phones? Probably not. Could he be like your old school Professor emeritus who still churns out papers and does 90% of it the old fashioned by-hand way? Yes. And Napoleon had a bunch of histories planned on St. Helena that he wanted to write, so I think he could do that.

As this is literally Napoleon Bonaparte he’d get a book deal in seconds. There’d be a bidding war over it.

--

Thank you for the ask! This was very amusing :D

#napoleon#napoleon was his own shitpost#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic#napoleon in the modern day#ask#reply#anon

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Superhero Values (2021)

Whether we have great powers or simply great responsibilities, we return to our values to guide our actions. This talk was revised and expanded for the Washington Ethical Society, February 21, 2021.

Earlier, you gave some advice to “Human Person” (a fictional superhero who “visited” earlier in the Platform) about compassion, understanding, and commitment, which are easier words to say than to practice. It helps to have role models, even if their stories didn’t happen exactly in the way they are told. It seems to me that mythology, fiction, and maybe even history can supply us with examples of values we can agree on. Stories that have captured our imaginations in the past may remind us of the people we hope to become.

When I was a kid, Batman was the lead character in some of those stories. He showed up in comic books and Pez dispensers, but the most influential form of Batman from my childhood was the Adam West character on television. When I was six or seven years old, the other kids who went to my babysitter and I used to run around the yard chasing super villains, pretending the basement steps were the Bat Cave, and generally doing our part for the good of Gotham City. We all traded roles as the heroes, heroines, and the various arch-nemeses.

I learned a couple of things from the Bat-team. I learned that superheroes have origin stories, events that changed the direction of their lives. You might not be able to tell from looking at them, especially in their secret identities, but every superhero has a past. The Bat-team also taught me that superheroes struggle with power. Whether the super skills come from hard work, cool gadgets, or another planet, heroes have to figure out the most effective and responsible way to use those skills. Finally, I learned that superheroes form coalitions. Batman and Robin and Batgirl worked together, not to mention Commissioner Gordon and Chief O’Hara. Even an independent vigilante needs other people for the toughest problems.

Come to think of it, those same things are true for all of us. Each of us has to decide how to respond to the past. Individually and as a group, we are faced with questions of power and responsibility. Teaming up with other people is a source of strength, in spite of and perhaps because of our differences. I think these characteristics of superheroes call attention to WES’s future as a community.

Heroes Have Origins

First, superheroes have origin stories. Some event from the past sparked the character’s discovery of talents and passions, leading to a new sense of identity and purpose. Those events might be associated with death or separation from a loved one, or with the loss of the character’s pre-heroic dreams.

Superman’s powers come from his extra-planetary birth, but his ideas about truth, justice, and the American way come from Martha and Jonathan Kent. There is some speculation that Superman’s creators (Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster) modeled him after Moses, a baby whose people faced destruction, and was carried in a small vessel to a land where his birth identity had to be concealed.

There is a category of stories in which the characters have qualities that were typical in their place of origin, but something called them to help people in a world similar to our own, where their profound difference turned out to be a gift. Wonder Woman, Black Panther, AquaMan, and Valkyrie fall into this category.

On the other hand, some superheroes start off with an event of pain or trauma, like Peter Parker’s radioactive spider bite to become Spiderman. Batman’s path is a response to trauma. In the Watchmen mini-series on HBO, one of the characters’ commitment to justice came from being a survivor of the 1921 white supremacist attack on Tulsa, Oklahoma. Ms. Marvel’s Kamala Khan is mainly in this category, having gained her powers during an unusual event.

Whatever the story, most extra-human comic book characters have faced a life-changing event that seems to isolate them from important people in their lives. Often, the character will acquire or discover or place new value on a gift or a talent they have during that experience. Picking up these pieces of loss, loneliness, and strength, the character eventually forges a new sense of purpose.

Michael Servetus (Miguel Serveto) is someone from history whose story follows this pattern a bit. He wasn’t always brave, and he wasn’t known for being kind, but he did set himself apart and commit his life to the truth as he saw it. I wouldn’t necessarily call him a Humanist, but he was a free thinker in that he defied the orthodoxy of his time, and his sacrifices made it possible for the people who came after him to do even more questioning of creeds, dogmas, and oppressive religious organizations.

When Servetus read the Bible for himself for the first time as a young student in the 1520s, he was shocked to discover no evidence for the doctrine of the Trinity. In 1531, he published a tract, De Trinitatis Erroribus (On the Errors of the Trinity), seemingly convinced that people would see it his way if only they would listen. That’s not what happened. He was run out of town, his books were confiscated, and the Supreme Council of the Inquisition started looking for him.

This is where the secret identity comes in. Servetus fled to Paris and assumed the name of Michel de Villeneuve. He had a varied career as de Villeneuve, first as an editor and publisher, then as a doctor. He worked on a seven-volume edition of the Bible, adding insightful footnotes. He was the first European to publish about the link between the pulmonary and respiratory systems.

During his time as the personal physician for the Archbishop of Vienne, he secretly worked on his next theological treatise, Christianismi Restitutio (The Restoration of Christianity). He also struck up a correspondence with his old classmate, John Calvin. Servetus was not diplomatic in his criticisms of Calvin’s writing, and Calvin broke off correspondence. Servetus seemed to think that their exchange was illuminating, because he included copies of the letters when he sent an advance copy of the Restitutio to Geneva.

The publication of the Restitutio in 1553 marked the end of Servetus’ secret identity. Both Protestant and Catholic authorities pursued him as a dangerous heretic. He was burned at the stake on October 27, 1553, by the order of The Council of Geneva. Reportedly, he maintained his beliefs until the end, shouting heretical prayers from the flames. The Catholic Inquisition in France burned Servetus in effigy a few months later. There were a lot of people who didn’t want his ideas to be heard. Luckily for us, a few copies of his books were preserved, and went on to generate new ideas among religious reformers for over 450 years.

Now, I’m not saying Michael Servetus was a superhero. It might be hard to identify with him in some ways. Though he had ideas that were called Unitarian at the time, Unitarian Universalists oday would disagree with most of what he wrote, as would most Ethical Culturists. His creeds don’t match most of our beliefs; though some of his deeds, such as challenging authority and being a medical provider, might resonate. Nevertheless, we can see how a turning point in someone’s life can bring isolation, energy, purpose, abilities, and vulnerabilities, all at the same time. His origins were more like Spiderman than Superman: Being in the right place at the right time, Servetus was bitten by the free thinking bug. He had to adopt an alter ego, but the bug also afforded him the drive and the insight to make great contributions to scholarship and religious freedom.

How often is it the same for those of us who are regular folks? The events that make us who we are may bring a sense of loss or loneliness. These same events may bring a chance for us to develop new talents, or personal connection to the work we aspire to do. Passion and vulnerability can come from a single point in time.

The thing that sets a superhero origin story apart from a villain origin story is how the character translates their past into a future of meaning and purpose. Most of us are not consistently villains or heroes; we have to choose in every moment how to draw from our past to make choices in the present. We can’t control the historical facts of our origin stories. Even if our own choices led to the turning points in our lives, they are in the past now. What we can do is bring our values to the way we understand those turning points, and to our decisions about what to do with the gifts we have now. Let’s do our best to choose to use our origins well.

Heroes Form Coalitions

The very first appearance of Spiderman (in Amazing Fantasy #15 in 1962) saw the teenage Peter Parker misusing his new powers, only to have his negligence contribute to the death of his Uncle Ben, one of his adoptive parents. Peter’s understanding of Ben’s teaching that “With great power there must also come—great responsibility!” shaped his character from then on. The spider counterparts from other universes, heroes like Gwen Stacy and Miles Morales, also have turning points on that theme.

Superhero characters struggling with power and responsibility would have benefitted from reading about James Luther Adams, who was a professor at Harvard during the 1950s and 1960s. Adams had a great deal to say about power and what that meant for the responsibilities of movements for liberation.

Between 1927 and the late 1930s, Adams made several trips to Germany, a country that was renowned for philosophical scholarship. He spoke with religious and academic leaders, was detained for questioning by the Gestapo, and developed a sense of urgency about the political, cultural, moral, and spiritual crisis that went along with the rise of the Nazi party. While Adams developed great respect for the anti-Nazi Confessing Church movement, he noticed that Germany’s churches as a whole were not pushing back against the crisis.

Adams said that individual and organized philosophy should be “examined.” There must be a path for critique, self-correction, and development. Adams wrote, “the achievement of freedom in community requires the power of organization and the organization of power.”

In that same period when Adams was noticing trends of power, organization, and responsibility in Germany, Humanists in the United States were also teaming up. The roots of some of these relationships went back to the Free Religious Association, which was the group where Felix Adler hung around with Ralph Waldo Emerson and the other Transcendentalists. The FRA led to another trend called the “Ethical Basis” group within Unitarianism.

I’m drawing here from The Humanist Way: An Introduction to Ethical Humanist Religion, a book by former WES Senior Leader Ed Ericson. Ericson writes that, by the end of the nineteenth century, the Ethical Basis bloc had successfully advocated that inclusion as either a member or a clergy person in Unitarian congregations be purely on an ethical basis rather than having any doctrinal basis. Ericson continues:

They resisted all attempts to impose any theological requirement, however broadly such a test might be construed. Like Felix Adler’s Ethical Culture, the Ethical Basis Unitarians regarded the dedicated ethical life to be inherently religious without any necessary underpinning of theological belief. This concurrence of views resulted in a close working relationship between the leaders of the Ethical Societies of Chicago and St. Louis and their ministerial counterparts in the Western Unitarian Conference.

(Ericson, The Humanist Way, p. 46-47)

Ericson goes on to say that, while this cohort was concentrated in the midwest, Octavius Brooks Frothingham in New York also largely shared Adler’s philosophy. Ericson also points out that the Ethical Basis cohort provided “a seedbed where organized religious Humanism, under that name, would first put down roots in American soil,” making this development of interest to Ethical Humanism. So, already at the turn of the century, there is some superhero teaming up going on. It gets better!

In 1913, the Unitarian minister John H. Dietrich began using the term “Humanism” to identify his non-theistic philosophy of religion. Dietrich said that he first encountered the term as a religious designation in the text of a lecture delivered to the London Ethical Society (Ericson, p. 61). Ericson writes that “the Ethical Union in Britain had described their movement by the turn of the century.” Ethical Culture in the United States started identifying more closely as a unique expression within the broader Humanist movement a little later, not until after Adler’s death in 1933. At that point, they found a whole league’s worth of Humanists to team up with.

But back to Dietrich, who discovered that his colleague Curtis Reese in Chicago was writing about the same kind of philosophy. Having found each other, they attracted others to the growing Humanist movement. By 1927, they had connected with scientists, philosophers, and journalists, who collectively were turning out what Ericson describes as “a torrent of books, articles, sermons and lectures” (p. 67) that established Humanism as a significant force in American society. In 1933, thirty-four of these prominent figures signed on to The Humanist Manifesto.

Later groups wrote the Humanist Manifesto II of 1973 and the Humanist Manifesto III of 2003. The original 1933 document set a historic precedent, bringing together people from a variety of perspectives and settings. Unitarian and Universalist ministers were well represented, along with V.T. Thayer, Director of the Ethical Culture Schools of New York, plus A. Eustace Haydon and Lester Mondale, who later became Ethical leaders (Ericson, p. 70).

I would suggest that the Washington Ethical Society, by affiliating with both the Unitarian Universalist Association and the American Ethical Union, is living out the spirit of cooperation that has powered the Humanist movement in the United States from its inception. Ethical Humanism is a unique expression and tradition within the larger Humanist movement, and yet that larger movement remains important for understanding who we are and what we are here to do. We come to a deeper understanding of identity and mission when we team up.

In fiction, superheroes seem to gravitate to one another. From the X-Men to the Avengers to the Teen Titans, collections of lead characters become ensembles. They have very different abilities and outlooks. Teaming up isn’t always easy, and it can be risky. Household squabbles may become epic battles if super abilities get out of hand. However, when they combine their gifts in the same direction, they can tackle complex problems that none of them would be able to handle alone.

This is why we form coalitions, too. WES is a community of people who have many differences in your individual lives. Diversity in creed and unity in deed, WES members are able to learn together, make music together, serve the community, and witness for justice, without worrying too much about who is an atheist or an agnostic or a theist or a polytheist. Whether among members, or in coalition with our neighbors across religious or geographic lines, we are able to put differences aside as we work for the benefit of our shared community. It does happen, though, that human beings forget, or retreat into what we think is a bubble of sameness, or narrow our scope of what seems possible.

Let’s build on what is already going well as we resist the shrinking of our horizons. There may be partners in our community that we have yet to meet. There may be institutes for exceptional heroes, or halls of justice, that we have to overcome our internalized hurdles of classism and racism before we can join.

At the very least, we can ensure that we’re making the most of our super team here at WES. Like the superheroes, we can do more and support each other when we come together.

Conclusion

There is a lot that WES has in common with an assembly of superheroes. Each one of us has an origin story, a set of events that shaped our talents, passions, and vulnerabilities. Each one of us has the opportunity to shape that story into a life of meaning and purpose. Like superheroes, it is incumbent on us to come to terms with power. Our collective abilities and assets make us a force to be reckoned with, and it is up to us to do the moral discernment to make sure we’re doing a good job wielding that power. Our honesty with each other and practicing all of our shared values and commitments will help. Like the best superheroes, we form alliances. Within the WES community, we share our specialized powers and support one another to accomplish goals none of us could handle alone. In our coalitions with other groups, we build bridges that support compassion. May all that has been divided be made whole.

May it be so.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

task 001: character introduction.

(admin tangerine, 21, est) ☼ who’s that hottie, standing outside the love hotel? it’s VERONICA LOMBARDI, a BISEXUAL CISFEMALE, who looks a lot like LEA MICHELE! NIKKI’s insta bio says SHE is an INFLUENCER and is looking for a fun time this summer. SHE is into DADDY/MOMMY KINK & GROUP SEX, but not into SCAT & BLOOD PLAY. by the way, SHE reminds me of TIGHT YOGA PANTS & COLORFUL SUNSETS.

quick infos:

full name: veronica eleanor rosemary lombardi

dob: august 23rd 1988 (she’ll turn 31 this year)

pob: las vegas, nevada.

kinks: daddy***/mommy kink, mild roughness, group sex, public sex, receiving oral (eat her out good and she’ll marry you... too soon) although she enjoys giving oral to girls and/or strap-ons/dildos, mutual masturbation, nipple play, hair pulling squirting, spanking, consensual somnophilia.

anti kinks: blood play, wax play, electric stimulation, bondage, very rough sex, scat, foot play, humiliation & extreme anal (fingering and butt plugs are fine, but there will be very rare anal sex).

3 favorite things: dancing naked at 2am to some electronic music or old rock songs, italian gelato (she’d give you a handjob for a raspberry gelato) & puppies videos on instagram.

3 things she hates: spiders or bugs of any sorts (excluding spider man or ant man or black widow wink wink), people who lack of respect & compassion, bad hair days.

+2 positive traits: easygoing & compassionate

-2 negative traits: gullible & jealous

wanted connections:

TAKEN BY LINCOLN LEWIS & HIGHLY WANTED! ex-husband: idk where i’m going with this, but i have a feeling this would be so interesting if he’d come back to the hotel and they’d reconnect after a few years of being apart and not speaking. bonus points for high sexual tension and cute stuff! suggested fcs: chris hemsworth, jamie dornan, tom hiddleston, john stamos, nick jonas or darren criss.

daddy and/or mommy: just that “caring, loving but also can please all your needs” vibe. spoiler alert, she won’t be the mommy, she’s too much of a sub for that (usually). keanu reeves, bradley cooper, jeremy renner, joel kinnaman / natalie dormer, amy adams, jessica chastain, priyanka chopra, gal gadot, olivia munn, anna hathaway.

TAKEN BY GABRIELLA PEREZ femme fatale: just a woman, preferably younger whom nikki just can’t resist. someone with dominant tendencies. or someone around her age too! suggested fcs: dianna agron, ana de armas, margot robbie, gal gadot.

friends with benefits: GIRLS GIRLS GIRLS GIRLS GIRLS no suggested fcs, i just want girls.

sexual tension: it says it all. all fcs!

headcanons

childhood + teenage years:

only child of a loving family of restaurant owners, veronica inherited the best conditions to become a typical italian girl from a just as typical italian family. she was loved by her parents, she loved them. she learned to cook at a very young age and had a noticeable talent. she was the preppy girl from the picture perfect family. she had a dog, alfredo, that she rescued from the streets and who became her only friend for most of her childhood.

in high school, she bonded with a pair of twin siblings who came from a completely different background. from what she knew, their parents were big gamblers and lost most of their savings in casino nights. these people had that edge and gave that down to earth vibe nikki admired yet could not completely comprehend. they were a dynamic trio that balanced one another perfectly. jack (npc) was a total artist who encouraged nikki to express herself, valerie (npc) was very analytical and had a talent at reading through nikki while nikki herself was that sweet figure who was easy to please and could easily please everyone.

when they graduated, valerie confessed she had no idea what she would be doing with her future with no money at all. they were sitting in nikki’s family restaurant and drinking beer in cask with nostalgia and a part of sadness. jack had big plans, he found an apartment in san francisco and wanted to become a graphic designer. nikki, however, was torn between taking over the family business or making a living of her own. that was when valerie drunkenly suggested to work at one of the newly opened strip clubs nearby their neighborhood.

so she did.

twenties:

she turned 18 when she realized she had lost so many years to living in a mold she no longer fit in. she was more than just preppy church outfits and cooking sundays with her mother, she was more than a daddy’s girl who washed tables when the restaurant was closed. what did adults always say? a good education promised a good future, so, veronica applied to the college of southern nevada for a degree in communications with a minor in women’s studies. she had no idea where she was heading, but it was a start.

her parents contributed by driving from class to home every day, they paid her more adult looking clothing and they finally gave her the freedom she never knew she needed until she reached majority.

although jack disappeared from her life, valerie remained very present. they did as they agreed and found a job at a high end strip club in vegas. they made good money instantly without having to do nasty stuff nikki had never been introduced to. within a few months, they saved enough to get matching tattoos, new jewelry and pay for valerie’s apartment. the club provided a living area a few blocks away, but valerie felt better living on her own. nikki tried to mingle and fit in with the other girls, but they were too different. maybe it was the education, maybe it was the background, but the trashy side of this job did not interest the italian girl more than that.

veronica worked as a stripper during college until she graduated with a degree that would soon become irrelevant and useless. with contribution from her parents who never even judged her for her job (it was true nikki did tell them it was just a dancing studio) and with her savings, veronica moved out of nevada and headed to california. she found a small place and joined a community business that organized all kinds of social and sport activities. she became a pro at all yoga, zumba, meditation and dancing activities. she loved to work with the kids, the families and the older people who were just searching for a fun time.

while she was working there, nikki started to get active on social media. she would most dance choreographies to massive songs, making hundreds of thousands of views on youtube. she liked the attention she was getting, but she still preferred her real job the most.

mid-twenties

so she met someone. randomly. they hooked up with no after thoughts, then hooked up again and again and again... it felt like love to them. everything escalated so quickly, but it felt like she was finally meeting her parents’ expectations so nikki went with it. LINCOLN proposed only a couple of months in the relationship, and they got married soon after that. he was smart, attractive, perfect, almost too good to be true. she never thought she would deserve someone like him. they lived together, and their love became very intense. marriage was not about dealing with every issues by fucking all over the place. she loved it, of course, but something was off between them. maybe they were falling out of love, maybe they did not take the time to evaluate their future together, maybe they were not made to be together. or maybe they were, just not at that moment.

they divorced a couple of years later like a couple who noticed they were better off as friends, the thing was they did not remain friends and decided to live life on their own. there was no fighting, plate throwing on the ground, ugly crying and couch sleeping. there were just goodbye kisses and passionate love making for the last time, or so they believed.

after divorce, she decided to quit her job and focused entirely on social medias.

now:

she has been an influencer and youtuber for the past 2-3 years. she posts about cooking, relaxing, fashion, and does a ton of vlogs.

she loves the sun, the vibes and the people of los angeles.

she also decided to open her own yoga and lifestyle studio, where she teaches for all ages and all kinds of people. from yoga to the basics of dancing, she loved to be surrounded with people. her well-developped flexibility from dancing served her beautifully. she hired other instructors but still runs the business while focusing on her instagram, which has 900 000 followers.

she has been divorced for the same amount of time without being able to quite erase LINCOLN from her mind. the truth is she never really dated or hooked up for the fun of it. she focused on work and on discovering new hobbies.

she heard about the love hotel through her friend, valerie, who joked about this being exactly what newly divorced nikki needed as a way to spice up her life. on a just as drunken night as the one that brought them to work as strippers, nikki called and reserved a room. it is taking her completely out of her comfort zone, but she has a feeling that this is for the best.

headcanons:

she is more of a receiver than a giver. she rarely decides to take the lead unless she really wants to or feel comfortable with the other person. she crushes and gets attracted very easily but nothing leads to serious relationships. she enjoys threesomes and being the center of attention in them. she is very comfortable in her body and would walk around naked all the time if it was socially accepted, so she does not mind having an audience too much.

outside of kinky stuff, she’s a romantic at heart. she LOVES to be treated with kindness and to be treated like a princess. she is also willing to do that for her partner, because if marriage taught her one thing, it’s that it takes two to tango. nikki’s at a point in her life when she wants to meet new people and have fun. she had plenty of it when she was stripping and dancing, but being rushed into marriage kind of made her lose herself into a world she was not completely ready to enter back then.

she volunteers at animal shelters and helps playing and socializing pets. she has a few scars here and there of times when it did not go that well with an animal. chances are she might be distracted at all times if she sees a cute puppy or kitty.

her instagram and youtube are filled with dancing videos, cooking videos, song covers, general vlogs and thirst traps. there’s a reason she got so famous from doing almost nothing at all and said reason is her perfect peach butt she just loves to show off.

she’s italian so yeah she’s all about sharing and loving and eating pasta all the time because that is her own definition of a dolce vita. she is kinda close to her parents, but their relationship became a bit rocky when a) she moved out and b) ended her perfect marriage and broke the traditional dream of building a family of her own before she hit thirty.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

DUAL PURPOSE

David Adjaye and A-Cold-Wall’s Samuel Ross on architecture, fashion, Covid-19, anti-racism, and the future of the creative industries

‘Architecture and fashion move away from each other, and then come really close, and then move away again,’ says Sir David Adjaye, on a video call from Accra. He is in conversation with Samuel Ross, stationed in London. It’s mid-summer and the world is in the grips of the Covid-19 pandemic and anti-racism protests. This is a transformative moment for both industries.

The architect behind the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Adjaye was recently commissioned to create Brixton’s Cherry Groce Memorial and Abu Dhabi’s Abrahamic Family House. He continues to work on the landmark Ghana National Cathedral, and champion new African architecture and architects.

Ross, who founded A-Cold-Wall* in 2015, is a rising star of the fashion industry. A natural master of cross-disciplinary collaboration, he has partnered with brands as wide-ranging as Nike (to create emergency blankets upcycled from plastic bottles, with aspirations to make them freely available in parks), Apple, Converse, Diesel, Oakley and Dr Martens, as well as recently establishing a grant fund for Black creatives.

Their discussion covered the impact of technology, localised production, the politicisation of architecture and fashion, anti-racism, the effects of pandemic, and the future of creative industries. Right after, they were photographed – Ross in person and Adjaye via video call – by Liz Johnson Artur, who has dedicated her three-decade career to documenting people of African descent.

Adjaye Associates’ design for the Abrahamic Family House on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island, comprising a mosque, a synagogue and a church.

Collaboration has long been key to Adjaye’s work. Artist Chris Ofili’s Within Reach, the British Pavilion at the 2003 Venice Biennale, designed with Adjaye and engineered by Charles Walker, Arup, featuring a glass sculpture titled Afro Kaleidoscope above the main gallery space.

Wallpaper*: How does the responsibility of creating lasting works – as opposed to ephemeral ideas –influence your designs and process?

DA: There’s a bit of a myth with this idea of permanence, because nothing is really permanent, not even architecture. It all ends up disappearing. Architecture [just] has a larger duration.

SR: It all comes down to having the ability to quantify if a product should exist, which goes back to functionality and use.

W*: As a discipline, architecture can be really slow, whereas fashion feels faster – but that’s not always the case as the after-effects can last a long time.

DA: Fashion seems to be absolutely immediate, but [its] impact might be in the way we look at the bodies of males and females. [Take] for example the work of Yves Saint Laurent: it’s profound, it changes and resonates through generations.

SR: Totally. I kind of look at fashion like a moving slipstream. This idea of [how garments can serve] changes from generation to generation, as times move forwards and as social movements move forwards.

‘I kind of look at fashion like a moving slipstream. This idea of [how garments can serve] changes from generation to generation, as times move forwards and as social movements move forwards.’ — Samuel Ross

W*: How do the materials you use embody the ideas that you want to portray in your work? Does sustainability play into your material choices?

SR: I’ve dabbled with technical and synthetic materials, although I’m moving into more sustainable materials. There is a movement happening within big tech that needs to be integrated into fabrication, which can then define fashion as a whole for the 21st century. Fashion should mean smart materials and patented weaves that are antibacterial, that cling and mould to the body, versus just being about a point of expression.

DA: In the built environment, we spent the 20th century industrialising, making very efficient materials that will get things done fast. With speed came excess and pollution and degradation and destruction. Now we are asking, how do we build responsibly? In architecture, we are talking about microbial issues and creating healthy environments. That’s become much more heightened with Covid-19. We have to look at the things that destroy the planet – pandemics and ecological collapses – and really be responsive. I’m working with communities here [in Accra] and discovering that compressed mud has incredible properties that we totally underestimated. We just assumed that it was primitive, but actually it’s one of the best performing and most abundant materials on the planet.

W*: How much of your work is about educating people in your respective professions, to push your industries forwards?

DA: With all design there is a kind of public role, especially if you’re interested in pushing the limits of your industry. You deliver things to the public, so the public needs to be able to hold you accountable. I taught for about a decade and then I stopped, because I was teaching in elite schools to kids who are already very privileged. Instead, now I mentor and I’m interested in finding emerging voices that are not getting attention, trying to support them or to help them think about their businesses in the early stages.

‘I chose architecture because it was part of a language that I felt was very much under-represented from the position of a person of colour within the global discourse. I felt that I had a lot to say and I wanted to be part of that conversation about how we make the contemporary world.’ — David Adjaye

A look from A-Cold-Wall’s pre-S/S21 collection.

Ross’ Beacon 1, presented at Serpentine Galleries as part of the 2019 Hublot Design Prize exhibition.

W*: How important has the role of mentor or mentee been in your career? When you started out, could you identify Black creatives you related to?

DA: A real hero for me when I started was Joe Casely-Hayford. He was simply a man of colour doing really excellent work. And I thought, ‘Why don’t we have that in other places?’ It actually drove me to want to do it. I have a stubborn disposition. To be faced with ‘You can’t do this because…’, well, the ‘because’ better be damn good! It made me angry when I was younger. I’m much more chilled out these days.

SR: Mentors have been seminal to my journey. I shifted my direction [from product and graphic design] towards fashion to be a little more expressive. At that time, Virgil [Abloh] and Kanye West happened to come across my work, and I started working underneath the two of them. They were great mentors, able to articulate between Western European and North American ideologies, whilst having an intrinsically Black imprint on the work they were producing. They took these references to an industry, cross-referenced them through channels of mass communication, and built a new language and discourse that a lot of designers of my generation now operate within. From these two mentors, I learned how to communicate ideas and to have this ‘scatter diagram’ approach to zig-zagging across industries.

‘For me, the act, the statement, the building, is always political, it’s always making a statement about the world that we are in, it’s always positioning an ideal of some sort. The building isn’t mute, it speaks volumes about a certain world value and morality.’ — David Adjaye

W*: In terms of communication, is fashion more inherently attuned to marketing, whereas architecture is built on letting the work speak for itself?

DA: Absolutely. There’s a desire to depoliticise architecture continually, and I fight against that all the time. For me, the act, the statement, the building, is always political, it’s always making a statement about the world that we are in, it’s always positioning an ideal of some sort. The building isn’t mute, it speaks volumes about a certain world value and morality.

SR: The work I showed at Serpentine Galleries [Ross won the 2019 Hublot Design Prize], and the work I’m soon to do with Marc Benda from Friedman Benda gallery, is about that. I’m pivoting towards the long form conversation, and how we stabilise and re-chisel the playing field for the next generation.

W*: How does collaboration enrich your work?

DA: When I left the Royal College of Art I missed not being in a campus environment. I would collaborate across disciplines, with a scientist or a musician. When I did the Venice Biennale with Chris Ofili in 2003, we flipped roles – I said, ‘you design and I’ll do the visuals’. It was amazing to see my now dear friend talking about architecture, to learn what was interesting to him. It teaches you different ways of seeing the world.

SR: I’m a moderately sized brand, so collaboration offers access to tooling and technology. It’s also about having an opportunity to push forwards a social consciousness. I’m thinking how I can carry as much information through a macro partner, let’s say Nike, without being too cumbersome: can I hijack a community to a certain degree and fix the attention?

Moving forward, the idea of showing collections needs to be completely rearticulated.’ — Samuel Ross

W*: Practically, has Covid-19 affected your business?

DA: I moved to Accra as I’m doing a lot of work in West Africa right now. This decade feels like the decade of Africa to me. This pandemic has unleashed this new connectivity that I’m very grateful for. I have three offices on different continents, and most of my time was spent moving between those. And now it’s become very technologically based. What’s kind of amazing is that it all works! Apart from the amazing aromas that you miss, I love the aroma of construction sites!

SR: We’ve decided not to do two shows a year any more. This idea of a continuous critique to an open market every six months when you’re building and growing didn’t necessarily sit right with me in the first place, but I was willing to participate and spar and win in that arena to show a more intellectual Black approach within fashion design. But moving forward, the idea of showing collections needs to be completely rearticulated. We are looking at more personable presentations, which almost feeds back into the early days, when counter-cultural movements actually began to swirl and churn around fashion brands. I’m becoming a bit more hands on with discourse with consumers. We’ve been able to compress and condense down the modelling of the company. And be more emotive and sensitive to market needs. And take a lot more risk. I’m hoping that it will kick start a few other contemporaries in a similar situation to ourselves.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

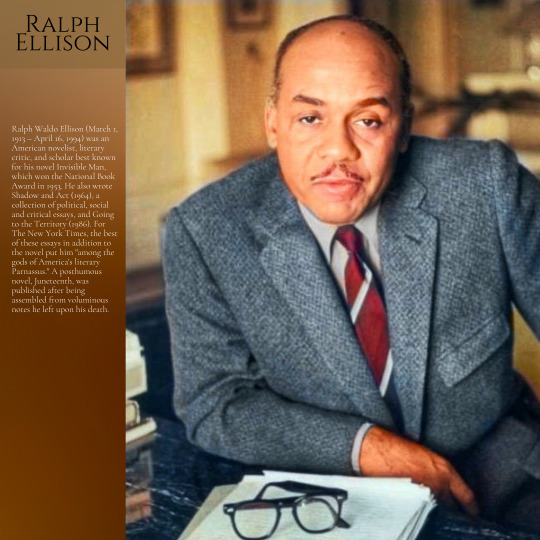

Ralph Ellison

Ralph Waldo Ellison (March 1, 1913 – April 16, 1994) was an American novelist, literary critic, and scholar best known for his novel Invisible Man, which won the National Book Award in 1953. He also wrote Shadow and Act (1964), a collection of political, social and critical essays, and Going to the Territory (1986). For The New York Times, the best of these essays in addition to the novel put him "among the gods of America's literary Parnassus." A posthumous novel, Juneteenth, was published after being assembled from voluminous notes he left upon his death.

Early life

Ralph Waldo Ellison, named after Ralph Waldo Emerson, was born at 407 East First Street in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, to Lewis Alfred Ellison and Ida Millsap, on March 1, 1913. He was the second of three sons; firstborn Alfred died in infancy, and younger brother Herbert Maurice (or Millsap) was born in 1916. Lewis Alfred Ellison, a small-business owner and a construction foreman, died in 1916, after an operation to cure internal wounds suffered after shards from a 100-lb ice block penetrated his abdomen, when it was dropped while being loaded into a hopper. The elder Ellison loved literature, and doted on his children, Ralph discovering as an adult that his father had hoped he would grow up to be a poet.

In 1921, Ellison's mother and her children moved to Gary, Indiana, where she had a brother. According to Ellison, his mother felt that "my brother and I would have a better chance of reaching manhood if we grew up in the north." When she did not find a job and her brother lost his, the family returned to Oklahoma, where Ellison worked as a busboy, a shoeshine boy, hotel waiter, and a dentist's assistant. From the father of a neighborhood friend, he received free lessons for playing trumpet and alto saxophone, and would go on to become the school bandmaster.

Ida remarried three times after Lewis died. However, the family life was precarious, and Ralph worked various jobs during his youth and teens to assist with family support. While attending Douglass High School, he also found time to play on the school's football team. He graduated from high school in 1931. He worked for a year, and found the money to make a down payment on a trumpet, using it to play with local musicians, and to take further music lessons. At Douglass, he was influenced by principal Inman E. Page and his daughter, music teacher Zelia N. Breaux.

At Tuskegee Institute

Ellison applied twice for admission to Tuskegee Institute, the prestigious all-black university in Alabama founded by Booker T. Washington. He was finally admitted in 1933 for lack of a trumpet player in its orchestra. Ellison hopped freight trains to get to Alabama, and was soon to find out that the institution was no less class-conscious than white institutions generally were.

Ellison's outsider position at Tuskegee "sharpened his satirical lens," critic Hilton Als believes: "Standing apart from the university's air of sanctimonious Negritude enabled him to write about it." In passages of Invisible Man, "he looks back with scorn and despair on the snivelling ethos that ruled at Tuskegee."

Tuskegee's music department was perhaps the most renowned department at the school, headed by composer William L. Dawson. Ellison also was guided by the department's piano instructor, Hazel Harrison. While he studied music primarily in his classes, he spent his free time in the library with modernist classics. He cited reading T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land as a major awakening moment. In 1934, he began to work as a desk clerk at the university library, where he read James Joyce and Gertrude Stein. Librarian Walter Bowie Williams enthusiastically let Ellison share in his knowledge.

A major influence upon Ellison was English teacher Morteza Drezel Sprague, to whom Ellison later dedicated his essay collection Shadow and Act. He opened Ellison's eyes to "the possibilities of literature as a living art" and to "the glamour he would always associate with the literary life." Through Sprague Ellison became familiar with Fyodor Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment and Thomas Hardy's Jude the Obscure, identifying with the "brilliant, tortured anti-heroes" of those works.

As a child, Ellison evidenced what would become a lifelong interest in audio technology, starting by taking apart and rebuilding radios, and later moved on to constructing and customizing elaborate hi-fi stereo systems as an adult. He discussed this passion in a December 1955 essay, "Living With Music," in High Fidelity magazine. Ellison scholar John S. Wright contends that this deftness with the ins-and-outs of electronic devices went on to inform Ellison's approach to writing and the novel form. Ellison remained at Tuskegee until 1936, and decided to leave before completing the requirements for a degree.

In New York

Desiring to study sculpture, he moved to New York City on 5 July 1936 and found lodging at a YMCA on 135th Street in Harlem, then "the culture capital of black America." He met Langston Hughes, "Harlem's unofficial diplomat" of the Depression era, and one—as one of the country's celebrity black authors—who could live from his writing. Hughes introduced him to the black literary establishment with Communist sympathies.