#bureaucrats india

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Citizen Support Centers Transform Rural Jharkhand: Jean Dreze

NSKs Bridge Gap Between Government Services and Villagers Jharkhand’s Nagarik Sahayata Kendras revolutionize rural governance, empowering marginalized communities by facilitating access to essential services across 76 blocks. RANCHI – Nagarik Sahayata Kendras in 76 Jharkhand blocks are transforming rural governance, facilitating access to essential services for marginalized communities. The…

#राज्य#citizen support centers#digital divide rural India#empowering marginalized communities#government service access#MNREGA Implementation#Nagarik Sahayata Kendras#Rural Development Jharkhand#rural governance improvement#social welfare schemes#state#streamlining bureaucratic processes

0 notes

Text

Black Figure

Yesterday I never went to the gov’t building to make the daily bread as a managing government bureaucrat. I decided to take a couple of days off. On this day off during the night I was in an engaging political discussion on the What’s Up app. When I was finished, I decided to lay down. The lights were still on in the adjacent room, so my bedroom was not totally dark. I was lying on my stomach,…

0 notes

Text

From Conflict to Harmony: A Tale of Two Realities

In a world gripped by the tragedies of conflict, we find ourselves torn between the desolation of war and the beacon of hope that unites us—sports. The recent events in the Israel-Palestine conflict have cast a shadow on humanity, with lives lost, infrastructure shattered, and livelihoods extinguished. It's a stark reminder of the fragility of peace and the urgent need for unity.

Amidst these somber circumstances, a glimmer of hope emerges on the other side of the globe. The International Olympic Committee, in a symbolic gesture, inaugurates its proceedings at Mumbai in the presence of Shri Narendra Modi ji and president of international olympic committee Mr. Thomas Bach.

As the world witnesses the devastation of war, the IOC, through the words of Mrs. Nita Ambani, emphasizes the crucial role of sports in fostering holistic human development. The vision resonates with PM Modi's belief in sports as a catalyst for unity, breaking down barriers and fostering a sense of belonging —an ode to the noble idea of "Vasudaika Kutumbakam" or "One World, One Family," as championed by India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

The recent Asian Games showcased India's prowess in sports, with numerous winners emerging from humble family backgrounds. PM Modi is happy about the children of Inda performing well and he also congratulated Indian cricket team at the same dias for winning yesterdays match of world cup cricket against Pakistan. This success story highlights the transformative power of sports, offering opportunities for all, irrespective of socio-economic status. All this can only be possible with creating infrastructure available for all aspiring sportsmen without any boundaries.

However, to facilitate the journey from humble beginnings to global success, the importance of robust sports infrastructure cannot be overstated. This is where bureaucrats in India specially the heads of the districts who are the district collectors can play a pivotal role in shaping the nation's sports landscape, thereby nurturing human potential.

District Collectors, as the administrative heads of districts, hold a pivotal position in the Indian bureaucracy. They are entrusted with the responsibility of not only overseeing law and order but also with the development and welfare of the region they serve. In recent times, an increasing number of District Collectors have recognized the transformative power of sports in shaping the future of their districts.

Their role extends beyond merely maintaining law and order. They are actively involved in the overall development of their districts. This includes areas like education, healthcare, infrastructure, and, crucially, sports. Sports have emerged as an effective tool for human development and societal transformation.

Empowering the youth, especially those hailing from humble backgrounds, is a key goal. District Collectors are driven by the vision that every child, regardless of their socio-economic status, should have access to opportunities that enable them to become champions not only in sports but also in life.

One such District Collector who has led visionary initiatives to promote sports at the grassroots level is Hari Chandana IAS. During her tenure as the Collector of Narayanpet District, Telangana, she laid the foundation for a brighter future. Her dedication to human development through sports is an embodiment of the collective investment needed to shape future global champions.

Hari Chandana IAS's belief is simple yet profound: with the right opportunities, every child can become a champion. During her time in Narayanpet District, she focused on providing accessible sports grounds for children with dreams of excelling in sports. These initiatives were rooted in her firm conviction that the infrastructure for sports and opportunities for children should not be bound by socio-economic barriers.

The transformative potential of sports extends to all aspects of human development. Sports foster discipline, teamwork, leadership, and a sense of purpose. They contribute to the physical and mental well-being of individuals. Moreover, they create a sense of unity and togetherness that transcends divisions.

The influence of District Collectors like Hari Chandana IAS in promoting sports infrastructure and, consequently, human development is a testimony to the power of collective investment in nurturing future champions. Their vision resonates with the ideals of a united and empowered India, which stands as a beacon on the global stage.

In conclusion, as we reflect on the devastation of conflicts worldwide and the uplifting spirit of sports, we realize that sports can be a powerful force for human development. Bureaucrats, specifically District Collectors, play a pivotal role in promoting sports infrastructure. Hari Chandana IAS's visionary initiatives underline the transformative potential of sports. It's not a question of whether sports can shape lives; it's a question of how far we are willing to go to realize this vision of a united and empowered world.

#Sports#Human Development#Bureaucrats#Sports Infrastructure#Sporting India#Olympics 2036#New India 2047#She Inspires Us

0 notes

Text

The year 2024 marks a decade since the landmark NALSA judgement that recognised the rights of transgender persons in India. But Delhi’s transgender community continues to face an uphill battle for basic recognition and access to essential services.

Bureaucratic red tape, insensitive verification processes and the absence of systemic accountability make it nearly impossible for many trans individuals to secure essential identity documents such as the transgender ID card, which is also a crucial document for accessing healthcare, employment, and education.

For activists like Pari, a trans woman working at Delhi’s Naz Foundation, the numbers are telling: out of the 75 people she has helped apply for certificates, only two have been successful. Her own reluctance to apply stems from the same fears that paralyse much of the community – an exhausting maze of paperwork, multiple office visits and the threat of family rejection.

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Passed in February [2024], a massive subsidy program to help Indian households install rooftop solar panels in their homes and apartments aims to provide 30 gigawatt hours of solar power to the nation’s inventory.

The scheme, called PM-Surya Ghar, will provide free electricity to 10 million homes according to estimates, and the designing of a national portal—a sort of Healthcare.gov for solar panels—will streamline the process of installation and payment.

The program was cooked up because India had fallen woefully behind on its planned installations for rooftop solar. In many parts of the subcontinent, the sun is absolutely brutal and relentless, but by 2022, Indian rooftop solar power generation topped out at 11 gigawatts, which was 29 gigawatts under a national target set a decade ago.

Part of the challenge, Euronews reports, is that approval from various agencies and departments—as many as 21 different signatures in some cases—was needed to place a solar array on your house. Aside from this bureaucratic nightmare, the cost of installation was often higher than $5,000; more than half the average yearly income for a working Indian urbanite.

Under PM-Surya Ghar, subsidies for a 2-kilowatt solar array will cover as much as 60% of the installation costs, falling to 40% for arrays 3 kilowatts or higher. Loans set at around 7% interest rates will help families in need get started. 750 billion Indian rupees, or $9 billion has been set aside for the project.

Even in New Delhi, which can be covered in clouds and smog for days, solar users report saving hundreds during summer time on their electricity costs, with one apartment shaving $700 every month off energy bills.

PM-Surya Ghar is also seen as having the potential to cause a boom in the Indian solar market. Companies no longer have to go running around for planning and permitting requirements, and the government subsidies ensure their customer base can grow beyond the limits of household income."

-Good News Network, April 10, 2024

#india#new delhi#solar#solar panels#clean energy#solar power#renewables#rooftop solar#climate policy#climate action#climate hope#renewable energy#good news#hope

271 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1872, W.A. Short, a government official in northern Indian was ordered to create a register of the Hijra living in his area. This was part of a British colonial policy of criminalising Hijra, whose gender-non-conforming practices, such as castration and wearing female dress, fell outside of British norms.

Short chose not to register a single person. When his superiors questioned him, he set out to prove that there was no reason to suspect the local Hijra any crimes. The list he provided in 1873 stands out from other bureaucratic sources of the time for providing a nuanced picture of the lives of eleven Hijra, giving us insight into their family structure, shared households, and ways of supporting themselves and each other.

Check out our podcast to hear their stories, and learn more about the history of Hijra in northern India!

[Image: A Hijra and her companions in East Bengal, 1860s]

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about this line in GtN hinting at the organisation of the Empire beyond the House system. Third House governor to gov with Fifth House bureaucrats? Politics vs wallet? Necromantic viceroy vs Necromantic East India Company?

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shikigami and onmyōdō through history: truth, fiction and everything in between

Abe no Seimei exorcising disease spirits (疫病神, yakubyōgami), as depicted in the Fudō Riyaku Engi Emaki. Two creatures who might be shikigami are visible in the bottom right corner (wikimedia commons; identification following Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage, pp. 57-58)

In popular culture, shikigami are basically synonymous with onmyōdō. Was this always the case, though? And what is a shikigami, anyway? These questions are surprisingly difficult to answer. I’ve been meaning to attempt to do so for a longer while, but other projects kept getting in the way. Under the cut, you will finally be able to learn all about this matter.

This isn’t just a shikigami article, though. Since historical context is a must, I also provide a brief history of onmyōdō and some of its luminaries. You will also learn if there were female onmyōji, when stars and time periods turn into deities, what onmyōdō has to do with a tale in which Zhong Kui became a king of a certain city in India - and more!

The early days of onmyōdō In order to at least attempt to explain what the term shikigami might have originally entailed, I first need to briefly summarize the history of onmyōdō (陰陽道). This term can be translated as “way of yin and yang”, and at the core it was a Japanese adaptation of the concepts of, well, yin and yang, as well as the five elements. They reached Japan through Daoist and Buddhist sources. Daoism itself never really became a distinct religion in Japan, but onmyōdō is arguably among the most widespread adaptations of its principles in Japanese context.

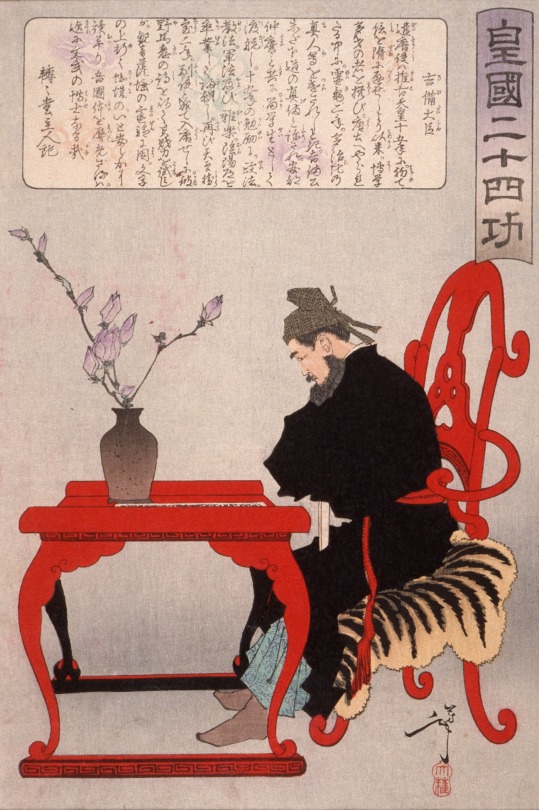

Kibi no Makibi, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (wikimedia commons)

It’s not possible to speak of a singular founder of onmyōdō comparable to the patriarchs of Buddhist schools. Bernard Faure notes that in legends the role is sometimes assigned to Kibi no Makibi, an eighth century official who spent around 20 years in China. While he did bring many astronomical treatises with him when he returned, this is ultimately just a legend which developed long after he passed away.

In reality onmyōdō developed gradually starting with the sixth century, when Chinese methods of divination and treatises dealing with these topics first reached Japan. Early on Buddhist monks from the Korean kingdom of Baekje were the main sources of this knowledge. We know for example that the Soga clan employed such a specialist, a certain Gwalleuk (観勒; alternatively known under the Japanese reading of his name, Kanroku).

Obviously, divination was viewed as a very serious affair, so the imperial court aimed to regulate the continental techniques in some way. This was accomplished by emperor Tenmu with the formation of the onmyōryō (陰陽寮), ��bureau of yin and yang” as a part of the ritsuryō system of governance. Much like in China, the need to control divination was driven by the fears that otherwise it would be used to legitimize courtly intrigues against the emperor, rebellions and other disturbances. Officials taught and employed by onmyōryō were referred to as onmyōji (陰陽師). This term can be literally translated as “yin-yang master”. In the Nara period, they were understood essentially as a class of public servants. Their position didn’t substantially differ from that of other specialists from the onmyōryō: calendar makers, officials responsible for proper measurement of time and astrologers. The topics they dealt with evidently weren’t well known among commoners, and they were simply typical members of the literate administrative elite of their times.

Onmyōdō in the Heian period: magic, charisma and nobility

The role of onmyōji changed in the Heian period. They retained the position of official bureaucratic diviners in employ of the court, but they also acquired new duties. The distinction between them and other onmyōryō officials became blurred. Additionally their activity extended to what was collectively referred to as jujutsu (呪術), something like “magic” though this does not fully reflect the nuances of this term. They presided over rainmaking rituals, purification ceremonies, so-called “earth quelling”, and establishing complex networks of temporal and directional taboos.

A Muromachi period depiction of Abe no Seimei (wikimedia commons)

The most famous historical onmyōji like Kamo no Yasunori and his student Abe no Seimei were active at a time when this version of onmyōdō was a fully formed - though obviously still evolving - set of practices and beliefs. In a way they represented a new approach, though - one in which personal charisma seemed to matter just as much, if not more, than official position. This change was recognized as a breakthrough by at least some of their contemporaries. For example, according to the diary of Minamoto no Tsuneyori, the Sakeiki (左經記), “in Japan, the foundations of onmyōdō were laid by Yasunori”.

The changes in part reflected the fact that onmyōji started to be privately contracted for various reasons by aristocrats, in addition to serving the state. Shin’ichi Shigeta notes that it essentially turned them from civil servants into tradespeople. However, he stresses they cannot be considered clergymen: their position was more comparable to that of physicians, and there is no indication they viewed their activities as a distinct religion. Indeed, we know of multiple Heian onmyōji, like Koremune no Fumitaka or Kamo no Ieyoshi, who by their own admission were devout Buddhists who just happened to work as professional diviners.

Shin’ichi Shigeta notes is evidence that in addition to the official, state-sanctioned onmyōji, “unlicensed” onmyōji who acted and dressed like Buddhist clergy, hōshi onmyōji (法師陰陽師) existed. The best known example is Ashiya Dōman, a mainstay of Seimei legends, but others are mentioned in diaries, including the famous Pillow Book. It seems nobles particularly commonly employed them to curse rivals. This was a sphere official onmyōji abstained from due to legal regulations. Curses were effectively considered crimes, and government officials only performed apotropaic rituals meant to protect from them. The Heian period version of onmyōdō captivated the imagination of writers and artists, and its slightly exaggerated version present in classic literature like Konjaku Monogatari is essentially what modern portrayals in fiction tend to go back to.

Medieval onmyōdō: from abstract concepts to deities

Gozu Tennō (wikimedia commons)

Further important developments occurred between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. This period was the beginning of the Japanese “middle ages” which lasted all the way up to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. The focus in onmyōdō in part shifted towards new, or at least reinvented, deities, such as calendarical spirits like Daishōgun (大将軍) and Ten’ichijin (天一神), personifications of astral bodies and concepts already crucial in earlier ceremonies. There was also an increased interest in Chinese cosmological figures like Pangu, reimagined in Japan as “king Banko”. However, the most famous example is arguably Gozu Tennō, who you might remember from my Susanoo article.

The changes in medieval onmyōdō can be described as a process of convergence with esoteric Buddhism. The points of connection were rituals focused on astral and underworld deities, such as Taizan Fukun or Shimei (Chinese Siming). Parallels can be drawn between this phenomenon and the intersection between esoteric Buddhism and some Daoist schools in Tang China. Early signs of the development of a direct connection between onmyōdō and Buddhism can already be found in sources from the Heian period, for example Kamo no Yasunori remarked that he and other onmyōji depend on the same sources to gain proper understanding of ceremonies focused on the Big Dipper as Shingon monks do.

Much of the information pertaining to the medieval form of onmyōdō is preserved in Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), a text which is part divination manual and part a collection of myths. According to tradition it was compiled by Abe no Seimei, though researchers generally date it to the fourteenth century. For what it’s worth, it does seem likely its author was a descendant of Seimei, though. Outside of specialized scholarship Hoki Naiden is fairly obscure today, but it’s worth noting that it was a major part of the popular perception of onmyōdō in the Edo period. A novel whose influence is still visible in the modern image of Seimei, Abe no Seimei Monogatari (安部晴明物語), essentially revolves around it, for instance.

Onmyōdō in the Edo period: occupational licensing

Novels aside, the first post-medieval major turning point for the history of onmyōdō was the recognition of the Tsuchimikado family as its official overseers in 1683. They were by no means new to the scene - onmyōji from this family already served the Ashikaga shoguns over 250 years earlier. On top of that, they were descendants of the earlier Abe family, the onmyōji par excellence. The change was not quite the Tsuchimikado’s rise, but rather the fact the government entrusted them with essentially regulating occupational licensing for all onmyōji, even those who in earlier periods existed outside of official administration.

As a result of the new policies, various freelance practitioners could, at least in theory, obtain a permit to perform the duties of an onmyōji. However, as the influence of the Tsuchimikado expanded, they also sought to oblige various specialists who would not be considered onmyōji otherwise to purchase licenses from them. Their aim was to essentially bring all forms of divination under their control. This extended to clergy like Buddhist monks, shugenja and shrine priests on one hand, and to various performers like members of kagura troupes on the other.

Makoto Hayashi points out that while throughout history onmyōji has conventionally been considered a male occupation, it was possible for women to obtain licenses from the Tsuchimikado. Furthermore, there was no distinct term for female onmyōji, in contrast with how female counterparts of Buddhist monks, shrine priests and shugenja were referred to with different terms and had distinct roles defined by their gender. As far as I know there’s no earlier evidence for female onmyōji, though, so it’s safe to say their emergence had a lot to do with the specifics of the new system. It seems the poems of the daughter of Kamo no Yasunori (her own name is unknown) indicate she was familiar with yin-yang theory or at least more broadly with Chinese philosophy, but that’s a topic for a separate article (stay tuned), and it's not quite the same, obviously.

The Tsuchimikado didn’t aim to create a specific ideology or systems of beliefs. Therefore, individual onmyōji - or, to be more accurate, individual people with onmyōji licenses - in theory could pursue new ideas. This in some cases lead to controversies: for instance, some of the people involved in the (in)famous 1827 Osaka trial of alleged Christians (whether this label really is applicable is a matter of heated debate) were officially licensed onmyōji. Some of them did indeed possess translated books written by Portuguese missionaries, which obviously reflected Catholic outlook. However, Bernard Faure suggests that some of the Edo period onmyōji might have pursued Portuguese sources not strictly because of an interest in Catholicism but simply to obtain another source of astronomical knowledge.

The legacy of onmyōdō

In the Meiji period, onmyōdō was banned alongside shugendō. While the latter tradition experienced a revival in the second half of the twentieth century, the former for the most part didn’t. However, that doesn’t mean the history of onmyōdō ends once and for all in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Even today in some parts of Japan there are local religious traditions which, while not identical with historical onmyōdō, retain a considerable degree of influence from it. An example often cited in scholarship is Izanagi-ryū (いざなぎ流) from the rural Monobe area in the Kōchi Prefecture. Mitsuki Ueno stresses that the occasional references to Izanagi-ryū as “modern onmyōdō” in literature from the 1990s and early 2000s are inaccurate, though. He points out they downplay the unique character of this tradition, and that it shows a variety of influences. Similar arguments have also been made regarding local traditions from the Chūgoku region.

Until relatively recently, in scholarship onmyōdō was basically ignored as superstition unworthy of serious inquiries. This changed in the final decades of the twentieth century, with growing focus on the Japanese middle ages among researchers. The first monographs on onmyōdō were published in the 1980s. While it’s not equally popular as a subject of research as esoteric Buddhism and shugendō, formerly neglected for similar reasons, it has nonetheless managed to become a mainstay of inquiries pertaining to the history of religion in Japan.

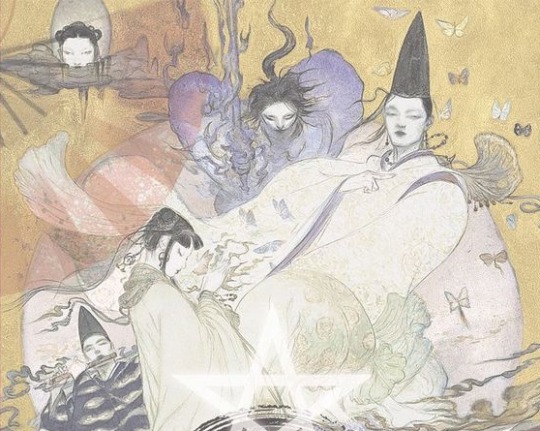

Yoshitaka Amano's illustration of Baku Yumemakura's fictionalized portrayal of Abe no Seimei (right) and other characters from his novels (reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Of course, it’s also impossible to talk about onmyōdō without mentioning the modern “onmyōdō boom”. Starting with the 1980s, onmyōdō once again became a relatively popular topic among writers. Novel series such as Baku Yumemakura’s Onmyōji, Hiroshi Aramata’s Teito Monogatari or Natsuhiko Kyōgoku’s Kyōgōkudō and their adaptations in other media once again popularized it among general audiences. Of course, since these are fantasy or mystery novels, their historical accuracy tends to vary (Yumemakura in particular is reasonably faithful to historical literature, though). Still, they have a lasting impact which would be impossible to accomplish with scholarship alone.

Shikigami: historical truth, historical fiction, or both?

You might have noticed that despite promising a history of shikigami, I haven’t used this term even once through the entire crash course in history of onmyōdō. This was a conscious choice. Shikigami do not appear in any onmyōdō texts, even though they are a mainstay of texts about onmyōdō, and especially of modern literature involving onmyōji.

It would be unfair to say shikigami and their prominence are merely a modern misconception, though. Virtually all of the famous legends about onmyōji feature shikigami, starting with the earliest examples from the eleventh century. Based on Konjaku Monogatari, there evidently was a fascination with shikigami at the time of its compilation. Fujiwara no Akihira in the Shinsarugakuki treats the control of shikigami as an essential skill of an onmyōji, alongside the abilities to “freely summon the twelve guardian deities, call thirty-six types of wild birds (...), create spells and talismans, open and close the eyes of kijin (鬼神; “demon gods”), and manipulate human souls”.

It is generally agreed that such accounts, even though they belong to the realm of literary fiction, can shed light on the nature and importance of shikigami. They ultimately reflect their historical context to some degree. Furthermore, it is not impossible that popular understanding of shikigami based on literary texts influenced genuine onmyōdō tradition. It’s worth pointing out that today legends about Abe no Seimei involving them are disseminated by two contemporary shrines dedicated to him, the Seimei Shrine (晴明神社) in Kyoto and the Abe no Seimei Shrine (安倍晴明神社) in Osaka. Interconnected networks of exchange between literature and religious practice are hardly a unique or modern phenomenon.

However, even with possible evidence from historical literature taken into account, it is not easy to define shikigami. The word itself can be written in three different ways: 式神 (or just 式), 識神 and 職神, with the first being the default option. The descriptions are even more varied, which understandably lead to the rise of numerous interpretations in modern scholarship. Carolyn Pang in her recent treatments of shikigami, which you can find in the bibliography, has recently divided them into five categories. I will follow her classification below.

Shikigami take 1: rikujin-shikisen

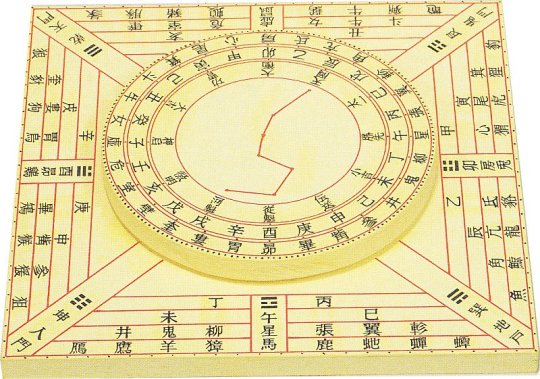

An example of shikiban, the divination board used in rikujin-shikisen (Museum of Kyoto, via onmarkproductions.com; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

A common view is that shikigami originate as a symbolic representation of the power of shikisen (式占) or more specifically rikujin-shikisen (六壬式占), the most common form of divination in onmyōdō. It developed from Chinese divination methods in the Nara period, and remained in the vogue all the way up to the sixteenth century, when it was replaced by ekisen (易占), a method derived from the Chinese Book of Changes.

Shikisen required a special divination board known as shikiban (式盤), which consists of a square base, the “earth panel” (地盤, jiban), and a rotating circle placed on top of it, the “heaven panel” (天盤, tenban). The former was marked with twelve points representing the signs of the zodiac and the latter with representations of the “twelve guardians of the months” (十二月将, jūni-gatsushō; their identity is not well defined). The heaven panel had to be rotated, and the diviner had to interpret what the resulting combination of symbols represents. Most commonly, it was treated as an indication whether an unusual phenomenon (怪/恠, ke) had positive or negative implications. It’s worth pointing out that in the middle ages the shikiban also came to be used in some esoteric Buddhist rituals, chiefly these focused on Dakiniten, Shōten and Nyoirin Kannon. However, they were only performed between the late Heian and Muromachi periods, and relatively little is known about them. In most cases the divination board was most likely modified to reference the appropriate esoteric deities.

Shikigami take 2: cognitive abilities

While the view that shikigami represented shikisen is strengthened by the fact both terms share the kanji 式, a variant writing, 識神, lead to the development of another proposal. Since the basic meaning of 識 is “consciousness”, it is sometimes argued that shikigami were originally an “anthropomorphic realization of the active psychological or mental state”, as Caroline Pang put it - essentially, a representation of the will of an onmyōji. Most of the potential evidence in this case comes from Buddhist texts, such as Bosatsushotaikyō (菩薩処胎経).

However, Bernard Faure assumes that the writing 識神 was a secondary reinterpretation, basically a wordplay based on homonymy. He points out the Buddhist sources treat this writing of shikigami as a synonym of kushōjin (倶生神). This term can be literally translated as “deities born at the same time”. Most commonly it designates a pair of minor deities who, as their name indicates, come into existence when a person is born, and then records their deeds through their entire life. Once the time for Enma’s judgment after death comes, they present him with their compiled records. It has been argued that they essentially function like a personification of conscience.

Shikigami take 3: energy

A further speculative interpretation of shikigami in scholarship is that this term was understood as a type of energy present in objects or living beings which onmyōji were believed to be capable of drawing out and harnessing to their ends. This could be an adaptation of the Daoist notion of qi (氣). If this definition is correct, pieces of paper or wooden instruments used in purification ceremonies might be examples of objects utilized to channel shikigami.

The interpretation of shikigami as a form of energy is possibly reflected in Konjaku Monogatari in the tale The Tutelage of Abe no Seimei under Tadayuki. It revolves around Abe no Seimei’s visit to the house of the Buddhist monk Kuwanten from Hirosawa. Another of his guests asks Seimei if he is capable of killing a person with his powers, and if he possesses shikigami. He affirms that this is possible, but makes it clear that it is not an easy task. Since the guests keep urging him to demonstrate nonetheless, he promptly demonstrates it using a blade of grass. Once it falls on a frog, the animal is instantly crushed to death. From the same tale we learn that Seimei’s control over shikigami also let him remotely close the doors and shutters in his house while nobody was inside.

Shikigami take 4: curse As I already mentioned, arts which can be broadly described as magic - like the already mentioned jujutsu or juhō (呪法, “magic rituals”) - were regarded as a core part of onmyōji’s repertoire from the Heian period onward. On top of that, the unlicensed onmyōji were almost exclusively associated with curses. Therefore, it probably won’t surprise you to learn that yet another theory suggests shikigami is simply a term for spells, curses or both. A possible example can be found in Konjaku Monogatari, in the tale Seimei sealing the young Archivist Minor Captains curse - the eponymous curse, which Seimei overcomes with protective rituals, is described as a shikigami.

Kunisuda Utagawa's illustration of an actor portraying Dōman in a kabuki play (wikimedia commons)

Similarities between certain descriptions of shikigami and practices such as fuko (巫蠱) and goraihō (五雷法) have been pointed out. Both of these originate in China. Fuko is the use of poisonous, venomous or otherwise negatively perceived animals to create curses, typically by putting them in jars, while goraihō is the Japanese version of Daoist spells meant to control supernatural beings, typically ghosts or foxes. It’s worth noting that a legend according to which Dōman cursed Fujiwara no Michinaga on behalf of lord Horikawa (Fujiwara no Akimitsu) involves him placing the curse - which is itself not described in detail - inside a jar.

Mitsuki Ueno notes that in the Kōchi Prefecture the phrase shiki wo utsu, “to strike with a shiki”, is still used to refer to cursing someone. However, shiki does not necessarily refer to shikigami in this context, but rather to a related but distinct concept - more on that later.

Shikigami take 5: supernatural being

While all four definitions I went through have their proponents, yet another option is by far the most common - the notion of shikigami being supernatural beings controlled by an onmyōji. This is essentially the standard understanding of the term today among general audiences. Sometimes attempts are made to identify it with a specific category of supernatural beings, like spirits (精霊, seirei), kijin or lesser deities (下級神, kakyū shin). However, none of these gained universal support. Generally speaking, there is no strong indication that shikigami were necessarily imagined as individualized beings with distinct traits.

The notion of shikigami being supernatural beings is not just a modern interpretation, though, for the sake of clarity. An early example where the term is unambiguously used this way is a tale from Ōkagami in which Seimei sends a nondescript shikigami to gather information. The entity, who is not described in detail, possesses supernatural skills, but simultaneously still needs to open doors and physically travel.

An illustration from Nakifudō Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

In Genpei Jōsuiki there is a reference to Seimei’s shikigami having a terrifying appearance which unnerved his wife so much he had to order the entities to hide under a bride instead of residing in his house. Carolyn Pang suggests that this reflects the demon-like depictions from works such as Abe no Seimei-kō Gazō (安倍晴明公画像; you can see it in the Heian section), Fudōriyaku Engi Emaki and Nakifudō Engi Emaki.

Shikigami and related concepts

A gohō dōji, as depicted in the Shigisan Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

The understanding of shikigami as a “spirit servant” of sorts can be compared with the Buddhist concept of minor protective deities, gohō dōji (護法童子; literally “dharma-protecting lads”). These in turn were just one example of the broad category of gohō (護法), which could be applied to virtually any deity with protective qualities, like the historical Buddha’s defender Vajrapāṇi or the Four Heavenly Kings. A notable difference between shikigami and gohō is the fact that the former generally required active summoning - through chanting spells and using mudras - while the latter manifested on their own in order to protect the pious. Granted, there are exceptions. There is a well attested legend according to which Abe no Seimei’s shikigami continued to protect his residence on own accord even after he passed away. Shikigami acting on their own are also mentioned in Zoku Kojidan (続古事談). It attributes the political downfall of Minamoto no Takaakira (源高明; 914–98) to his encounter with two shikigami who were left behind after the onmyōji who originally summoned them forgot about them.

A degree of overlap between various classes of supernatural helpers is evident in texts which refer to specific Buddhist figures as shikigami. I already brought up the case of the kushōjin earlier. Another good example is the Tendai monk Kōshū’s (光宗; 1276–1350) description of Oto Gohō (乙護法). He is “a shikigami that follows us like the shadow follows the body. Day or night, he never withdraws; he is the shikigami that protects us” (translation by Bernard Faure). This description is essentially a reversal of the relatively common title “demon who constantly follow beings” (常随魔, jōzuima). It was applied to figures such as Kōjin, Shōten or Matarajin, who were constantly waiting for a chance to obstruct rebirth in a pure land if not placated properly.

The Twelve Heavenly Generals (Tokyo National Museum, via wikimedia commons)

A well attested group of gohō, the Twelve Heavenly Generals (十二神将, jūni shinshō), and especially their leader Konpira (who you might remember from my previous article), could be labeled as shikigami. However, Fujiwara no Akihira’s description of onmyōji skills evidently presents them as two distinct classes of beings.

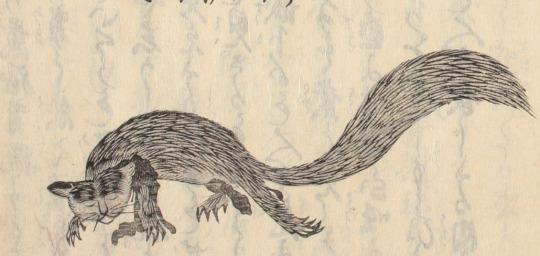

A kuda-gitsune, as depicted in Shōzan Chomon Kishū by Miyoshi Shōzan (Waseda University History Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Granted, Akihira also makes it clear that controlling shikigami and animals are two separate skills. Meanwhile, there is evidence that in some cases animal familiars, especially kuda-gitsune used by iizuna (a term referring to shugenja associated with the cult of, nomen omen, Iizuna Gongen, though more broadly also something along the lines of “sorcerer”), were perceived as shikigami.

Beliefs pertaining to gohō dōji and shikigami seemingly merged in Izanagi-ryū, which lead to the rise of the notion of shikiōji (式王子; ōji, literally “prince”, can be another term for gohō dōji). This term refers to supernatural beings summoned by a ritual specialist (祈祷師, kitōshi) using a special formula from doctrinal texts (法文, hōmon). They can fulfill various functions, though most commonly they are invoked to protect a person, to remove supernatural sources of diseases, to counter the influence of another shikiōji or in relation to curses.

Tenkeisei, the god of shikigami

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

The final matter which warrants some discussion is the unusual tradition regarding the origin of shikigami which revolves around a deity associated with this concept.

In the middle ages, a belief that there were exactly eighty four thousand shikigami developed. Their source was the god Tenkeisei (天刑星; also known as Tengyōshō). His name is the Japanese reading of Chinese Tianxingxing. It can be translated as “star of heavenly punishment”. This name fairly accurately explains his character. He was regarded as one of the so-called “baleful stars” (凶星, xiong xing) capable of controlling destiny. The “punishment” his name refers to is his treatment of disease demons (疫鬼, ekiki). However, he could punish humans too if not worshiped properly.

Today Tenkeisei is best known as one of the deities depicted in a series of paintings known as Extermination of Evil, dated to the end of the twelfth century. He has the appearance of a fairly standard multi-armed Buddhist deity. The anonymous painter added a darkly humorous touch by depicting him right as he dips one of the defeated demons in vinegar before eating him. Curiously, his adversaries are said to be Gozu Tennō and his retinue in the accompanying text. This, as you will quickly learn, is a rather unusual portrayal of the relationship between these two deities.

I’m actually not aware of any other depictions of Tenkeisei than the painting you can see above. Katja Triplett notes that onmyōdō rituals associated with him were likely surrounded by an aura of secrecy, and as a result most depictions of him were likely lost or destroyed. At the same time, it seems Tenkeisei enjoyed considerable popularity through the Kamakura period. This is not actually paradoxical when you take the historical context into account: as I outlined in my recent Amaterasu article, certain categories of knowledge were labeled as secret not to make their dissemination forbidden, but to imbue them with more meaning and value.

Numerous talismans inscribed with Tenkeisei’s name are known. Furthermore, manuals of rituals focused on him have been discovered. The best known of them, Tenkeisei-hō (天刑星法; “Tenkeisei rituals”), focuses on an abisha (阿尾捨, from Sanskrit āveśa), a ritual involving possession by the invoked deity. According to a legend was transmitted by Kibi no Makibi and Kamo no Yasunori. The historicity of this claim is doubtful, though: the legend has Kamo no Yasunori visit China, which he never did. Most likely mentioning him and Makibi was just a way to provide the text with additional legitimacy.

Other examples of similar Tenkeisei manuals include Tenkeisei Gyōhō (天刑星行法; “Methods of Tenkeisei Practice”) and Tenkeisei Gyōhō Shidai (天刑星行法次第; “Methods of Procedure for the Tenkeisei Practice”). Copies of these texts have been preserved in the Shingon temple Kōzan-ji.

The Hoki Naiden also mentions Tenkeisei. It equates him with Gozu Tennō, and explains both of these names refer to the same deity, Shōki (商貴), respectively in heaven and on earth. While Shōki is an adaptation of the famous Zhong Kui, it needs to be pointed out that here he is described not as a Tang period physician but as an ancient king of Rajgir in India. Furthermore, he is a yaksha, not a human. This fairly unique reinterpretation is also known from the historical treatise Genkō Shakusho. Post scriptum The goal of this article was never to define shikigami. In the light of modern scholarship, it’s basically impossible to provide a single definition in the first place. My aim was different: to illustrate that context is vital when it comes to understanding obscure historical terms. Through history, shikigami evidently meant slightly different things to different people, as reflected in literature. However, this meaning was nonetheless consistently rooted in the evolving perception of onmyōdō - and its internal changes. In other words, it reflected a world which was fundamentally alive. The popular image of Japanese culture and religion is often that of an artificial, unchanging landscape straight from the “age of the gods”, largely invented in the nineteenth century or later to further less than noble goals. The case of shikigami proves it doesn’t need to be, though. The malleable, ever-changing image of shikigami, which remained a subject of popular speculation for centuries before reemerging in a similar role in modern times, proves that the more complex reality isn’t necessarily any less interesting to new audiences.

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, A Religion in Search of a Founder?

Idem, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Makoto Hayashi, The Female Christian Yin-Yang Master

Jun’ichi Koike, Onmyōdō and Folkloric Culture: Three Perspectives for the Development of Research

Irene H. Lin, Child Guardian Spirits (Gohō Dōji) in the Medieval Japanese Imaginaire

Yoshifumi Nishioka, Aspects of Shikiban-Based Mikkyō Rituals

Herman Ooms, Yin-Yang's Changing Clientele, 600-800 (note there is n apparent mistake in one of the footnotes, I'm pretty sure the author wanted to write Mesopotamian astronomy originated 4000 years ago, not 4 millenia BCE as he did; the latter date makes little sense)

Carolyn Pang, Spirit Servant: Narratives of Shikigami and Onmyōdō Developments

Idem, Uncovering Shikigami. The Search for the Spirit Servant of Onmyōdō

Shin’ichi Shigeta, Onmyōdō and the Aristocratic Culture of Everyday Life in Heian Japan

Idem, A Portrait of Abe no Seimei

Katja Triplett, Putting a Face on the Pathogen and Its Nemesis. Images of Tenkeisei and Gozutennō, Epidemic-Related Demons and Gods in Medieval Japan

Mitsuki Umeno, The Origins of the Izanagi-ryū Ritual Techniques: On the Basis of the Izanagi saimon

Katsuaki Yamashita, The Characteristics of On'yōdō and Related Texts

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

TIGER HRT CHAPTER 1 - MONTH MINUS 6 - THE CONSULTATION

The specialest of special thanks to @ayviedoesthings for creating the original Dragon HRT story, and a big shoutout as well to @kaylasartwork, @welldrawnfish, @nyxisart, and @deadeyedfae for their takes on the concept! Every one of you is inspirational, and your work gives me so much second-hand gender euphoria!

NEXT

---

"Miss Alexis, please come in."

I look around as I walk inside. Between the doctor being a balding middle-aged man and the office looking like any generic doctor's office, I'm honestly a little disappointed. I was hoping the infamous source of therian HRT would be a little more… I don't know. Exotic? Unique? I was half expecting the walls to have before and after photographs of clients, but I suppose when it comes down to it, this is a serious medical facility, not a beauty salon. I walk up to the desk and sit down in the chair.

"Now I understand you wish to be a… a tiger?"

I'm unable to suppress my euphoria at the idea, and I start grinning and nodding. "A white tiger! I haven't changed my fursona since I got one, it's about time I start embodying it!"

"Indeed… And I see on your medical history that you are transgender." He mutters under his breath, "Just like all the others…"

I give a little smirk. 'All the others' are the reason I'm here. If this guy is handing out meds that can turn people into dragons or fish or bats, then a tiger should be easy, right? It's a mammal, and not much bigger than a human, relatively speaking. I had even given some thought to the rumoured "Fifteen Minute Shortcut", but when it comes down to it, even if I did have the ungodly pain tolerance to withstand such a rapid transformation of my bone structure and musculature, I… don't really want to do it quickly. Mundane HRT has already been such an absolute gift in terms of euphoria from noticing the slow and gradual changes, I want to keep that up. I want to notice the little things.

"Now I'm afraid there are some requirements to be settled first…"

Oh boy. Here comes the bureaucratic bullshit. Everything that's been put in place to make sure Our Children don't Make A Terrible Mistake. When it comes down to it, bodily autonomy only counts when you're not one of the weirdos. The instant you decide to be capital-d Different, people start falling over themselves trying to talk you out of it.

"First of all, I see that you have been taking human hormone therapy for a little over six months. We do require a full year of human treatment before beginning therian treatments, and I'm afraid that is fully non-negotiable. There are matters of biology that require the body to be a certain degree of… receptive."

I was afraid of this, but at least it's not a deal-killer. Another half-year is bearable, even if I am going to be shaking with anticipation the entire time.

"I also see you have letters from a practicing physician and a social worker, but we do require a second psychologist to be involved in the process."

Okay. Absolute horseshit, but not impossible. All I've got to do is find another social worker or psychologist. And pay them for several months of sessions. And hope they don't decide I'm crazy for wanting to throw away my humanity. I can feel my expression souring…

"It's also required to live as your desired species for at least a year before beginning the process."

"What." I'm leaning forward and glaring at the doctor before I fully realize it. "And how exactly am I supposed to do that, without the… the requisite biology, or the inborn instincts, or the… the habitat!" I let out a frustrated growl. "Am I supposed to fly off to India or Bangladesh or somewhere, and start camping out in the wilderness??"

"Miss Alexis, please, I'm afraid these are… are the requirements set forth by the guidelines of -"

"Guidelines!" I slam a palm down on the desk between us, before letting out a frustrated breath. "Just that… Guidelines. You know, and I know, that a lot of people have come to you already, with a lot more… exotic requests. Flying animals? Aquatic animals? A fucking DRAGON??"

The doctor seems taken aback, maybe he didn't expect this level of resistance.

"What is even the natural habitat of a dragon anyway? Or the diet? Or the behaviours in the wild?? It's a mythical creature for gods' sakes, there's no firm evidence they even existed!!" I stare at him, unblinkingly, with what I dearly hope is a predatory glare. "But I do get it, though. You have to be absolutely sure I won't regret it. Liability, or whatever. …Maybe we just need to know how hard I can BITE."

Something changes in his expression. ...Malice? No, not quite. A sort of… satisfaction, maybe.

It was a test. He wanted to know whether I'd just roll over and accept the impossibility of my quest, or whether I was prepared to fight for it.

Joke's on him, just getting human HRT was such a godsdamned hassle, I already know how to fight.

He adjusts his glasses. "Perhaps there is something I can do for you… Let me get you some forms."

92 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’ve been meaning to read more of Indian authors lately since I sometimes feel kinda ashamed to consume so much of foreign books but not of my own country, but the thing is … I just can’t get into most of them (that I’ve tried so far ). I’ve dnf’ed so many and I don’t even consider myself a picky reader. so it’d be helpful if you suggest some of your favourites that aren’t internationally popular ones.

I understand; I'm also very picky with the Indian authors I read, but here are some I've liked:

Battlefield by Vishram Bedekar (trans. Jerry Pinto): about two refugees fleeing wartime Europe (one Hindu, one Jewish), who meet on a ship and grow really close

Maharani by Ruskin Bond, or Room on the Roof, or The Blue Umbrella: I will turn myself inside out recommending Ruskin Bond, but these are my top three for you

Em and the Big Hoom by Jerry Pinto: about an East Indian family in Mumbai dealing with the mother's mental health; it's a really touching book

Our Moon Has Blood Clots by Rahul Pandita: a memoir of the Kashmiri Pandit genocide and its aftermath; it's a chilling memoir, but really good

English August by Upamanyu Chatterjee: about this elite bureaucrat who gets posted to the "hottest town in India" and how he deals with the locals; it has good satire going for it

Raag Darbari by Shrilal Shukl: another satire; follows a village and through it, explores democracy in early Independent India (or lack of it), the transition for the landed elite and generally most of the village to a democratic society. If you can read Hindi, I would recommend reading the original. If not, there's a translation by Gillian Wright.

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

How former bureaucrats in Modi government are transforming India

Former bureaucrats in Modi government are an asset for India’s governance. They are a reflection of India’s talent and potential. They are a testimony of Modi’s vision and leadership. They are a catalyst for India’s progress and transformation.

India is a country that faces many challenges, such as poverty, corruption, terrorism, climate change, and regional conflicts. To tackle these challenges, India needs a strong and visionary leadership that can formulate and implement effective policies for the welfare and development of the nation. One of the distinctive features of the current government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi is…

View On WordPress

#Ajit Doval#Ashwini Vaishnaw#former bureaucrats#Governance#Hardeep Singh Puri#India#Modi government#RK Singh#S Jaishankar#transformation

0 notes

Text

The problem with using value-added as a proxy for productivity is that value-added represents a combination of output (tangible and intangible) and prices/wages. ‘Productive’ employment in the tertiary sector, for instance, is as much a reflection of wage rates in that sector as any notion of productive output per se (for example, what is the output of a lawyer or a bureaucrat?) Hence, the use of value-added as a shorthand for productivity leads to absurd logical implications, such as the suggestion that a barber in the United States is 30 or more times more productive than a barber in India even though they both ‘produce’ the same number of haircuts per hour (according to the tastes and expectations of their clients), simply because the wage of the barber in the United States is 30 or more times higher. Or else, within the United States, that the ‘productivity’ of a lawyer is 20 times higher than that of a barber. The lawyer’s labour is certainly more valued than the barber’s, whether or not for good reason, but this has little to do with productivity (unless we consider that the power to leverage higher value for one’s labour is, in itself, a form of productivity). In other words, much of what we are picking up in most conventional measures of productivity actually amounts to price or wage differences, not actual effort or output, especially in economies that are increasingly based on services.

Andrew M. Fischer, Beware the Fallacy of Productivity Reductionism

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everybody treats JTTW like it's holy scripture and such like- No you jackass, JTTW was a composite of ancient stories and folk tales trying to explain how this actual real life dude got from China to India without getting mugged or eaten. There have been plays and sonnets made of this man's story before someone wrote it down in a VERY biased way towards Buddhism, you can tell it's bias by how it treats the Taoist figureheads like bumbling idiots half the time and people hiding behind their bureaucratic petticoats the other half. This is not scripture, it's not holy text, it's a bunch of stories made into a more streamlined narrative. Y'all would have your minds blown if you knew the evolution that Sun Wukong went through to get to his eventual book form.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

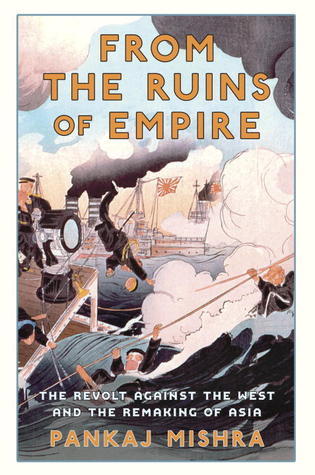

2024 Book Review #27 – From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt Against the West and the Remaking of Asia by Pankaj Mishra

Yet another work of nonfiction I picked up because an intriguing-sounding quote from it went viral on tumblr. This was the fifth history book I’ve read this year, but the first that tries very consciously to be an intellectual history. Both an interesting and a frustrating read – my overall opinion went back and forth a few times both as I read and as I put together this review.

The book is ostensibly a history of Asia’s intellectual response to European empire’s sudden military and economic superiority and political imperialism in the 19th and 20th centuries, though it’s focus and sympathy is overwhelmingly with what it calls ‘middle ground’ responses (i.e. neither reactionary traditionalism nor unthinking westernization). It structures this as basically a series of biographies of notable intellectual figures from the Islamic World, China and India from throughout the mid-late 19th and early 20th centuries - Liang Qichao and Jamal al-Din al-Afghani get star bidding and by far the most focus, with Rabindranath Tagore a distant third and a whole scattering of more famous personages further below him.

The central thesis of the book is essentially that the initial response of most rich, ancient Asian societies to sudden European dominance (rung in by the Napoleonic occupation of Egypt and the British colonization of India) was denial, followed (once European guns and manufactured goods made this untenable) by a deep sense of inferiority and humiliation. This sense of inferiority often resulted in attempts by ruling elites and intellectuals to abandon their own traditions and westernize wholesale (the Ottoman Tanzimat reforms, the New Culture Movement in China, etc), but at the same time different intellectual currents responded to the crisis by synthesizing their own visions of modernity, and tried to construct a new world with a centre other than the West.

I will be honest, my first and most fundamental issue with this book is that I just wish it was something it wasn’t. Which is to say, it is a resolutely intellectual and idealist history, convinced of the power of ideas and rhetoric as the engine for changing the world. Which means that the biography of one itinerant revolutionary is exhaustively followed so as to trace the evolution of his world-historically important thoughts, but the reason the Tanzimat Reforms failed is just brushed aside as having something to do with europhile bureaucrats building opera houses in Istanbul. Not at all hyperbole to say I’d really rather it was actually the exact opposite – the latter is just a much more interesting subject!

Not that the biographies aren’t interesting! They very much are, and do an excellent job of getting across just how interconnected the non-Western (well, largely Islamic and to a lesser extent Sino-Pacific) world was in the early/mid-19th century, and even moreso how late 19th/early 20th century globalization was not at all solely a western affair. They’re also just fascinating in their own right, the personalities are larger than life and the archetype of the globe-trotting polyglot intelligentsia is one I’ve always found very compelling. While I complain about the lack of detail, the book does at least acknowledge the social and economic disruptions that even purely economic colonialism created, and the impoverishment that created the social base the book’s subjects would eventually try to arouse and organize. And, even if I wish they were all dug into in far more detail, the book’s narrative is absolutely full of fascinating anecdotes and episodes I want to read about in more detail now.

Which is a problem with the book that it’s probably fairer to hold against it – it’s ostensible subject matter could fill libraries, and so to fit what it wants to into a readable 400-page volume, it condenses, focuses, filters and simplifies to the point of myopia. Which, granted, is the stereotypical historian’s complaint about absolutely anything that generalizes beyond the level of an individual village or commune, but still.

This isn’t at all helped but the overriding sense that this was a book that started with the conclusion and then went back looking for evidence to support its thesis and create a narrative. Which is a shame, because the section on the post-war and post-decolonization world is by far the sloppiest and least convincing, in large part because you can feel the friction of the author trying to make their thesis fit around the obvious objections to it.

Which is to say, the book draws a line on the evolution of Asian thought through trying to westernize/industrialize/nationalize and compete with the west on it’s own terms (in the book’s view) a more authentic and healthy view that rejects the western ideals of materialism and nationalism into something more spiritual, humane, and cosmopolitan, with Gandhi kind of the exemplar of this kind of view. It tries to portray this anti-materialistic worldview as the ideology of the future, the natural belief system of Asia which Europe and America can hope to learn from. It then, ah, lets say struggles to to find practical evidence of this in modern politics or economics, lets say (the Islamic Republic of Iran and Edrogan’s Turkey being the closest). It is also very insistent that ‘westernization’ is a false god that can never work, which is an entirely reasonable viewpoint to defend but if you are then you really gotta remember that Japan/South Korea/Taiwan like, exist while going through all the more obvious failures. One is rather left feeling that Mishra is trying to speak an intellectual hegemony into existence, here. (The constant equivocation and discomfort when bringing up socialism – the materialistic western export par excellence, but also perhaps somewhat important in 20th century Asian intellectual life – also just got aggravating).

It’s somewhere between interesting and bleakly amusing that modernity and liberal democracy have apparently been discredited and ideologically exhausted for more than one hundred years now! Truly we are ruled by the ideals of the dead.

I could honestly complain about the last chapter at length – the characterization of Islam as somehow more deeply woven in and inextricable from Muslim societies than any other religion and the resultant implicit characterization of secular government as necessarily western intellectual colonialism is a big one – but it really is only a small portion of the book, so I’ll restrain myself. Though the casual mention of the failures of secular and socialist post-colonial nation-building projects always just reminds me of reading The Jakarta Method and makes me sad.

So yeah! I felt significantly more positively about the book before I sat down and actually organized my thoughts about it. Not really sure how to take that.

#book review#history#From the Ruins of Empire#From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt Against the West and the Remaking of Asia#Pankaj Mishra

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vice president Kamala Harris Sunday reminisced about her Indian roots and said when she used to visit her grandparents, her grandfather used to take her on morning walks and then discuss the importance of fighting for equality and fighting corruption. In her post made on the occasion of the National Grandparents Day, Kamala Harris included an old family photo and claimed that her grandfather had been a part of the movement to win India's independence.

"As a young girl visiting my grandparents in India, my grandfather took me on his morning walks, where he would discuss the importance of fighting for equality and fighting corruption. He was a retired civil servant who had been part of the movement to win India’s independence.

"My grandmother traveled across India—bullhorn in hand—to speak with women about accessing birth control.

"Their commitment to public service and fight for a better future live on in me today.

"Happy National Grandparents Day to all the grandparents who help shape and inspire the next generation," the post read.

Social media users from India objected to the claim and pointed out that her grandfather was in the British Imperial Secretariat Service which became the Central Secretariat Service after Independence. "How could a serving bureaucrat be part of the independence movement opposing the same government and violating service rules?" one user wrote. "Everything you say is a lie," another said.

This is not the first time that Kamala Harris mentioned that her grandfather PV Gopalan was one of the "original independence fighters in India". But according to records, Gopalan was born in 1911 and was a diligent civil servant. Gopalan's son, Kamala Harris' uncle G Balachandran said that had his father openly advocated ending British rule, he could have been fired.

Gopalan was born in Painganadu near the Madras presidency in 1911. He joined the Indian civil services and also served in Zambia, where he was assigned to manage an influx of refugees.

While Kamala Harris' Indian roots are much discussed, reports surfaced Sunday that Kamala Harris would be meeting Congress leader from India DK Shivakumar, the deputy chief minister of Karnataka. But Shivakumar dismissed the rumors of his meeting with Harris and Barack Obama and said he is travelling to the US on a personal visit. _________________

I bet he's the one that taught her to say fweedom too.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

SneakPeak#107.......

From the story I might never write

[Iskaed au pt.1]

Those misogynistic pigs!!! They only wanted to meet today to try and intimidate me.

As if, I snorted and massaged the crown of my head with my pointers.

I did not work through blood and tears for half a decade so some self obsessed, greedy politicians could frame me for treason against my country.

To be an Indian foriegn secretary had taken a better portion of my life.

I had to completely flip my attitude to pursue the sudden passion I had acquired, no more parties, late night rendezvous, lack of routine and so on. Basically every rule that I had lived by for the 21 years, before I decided I wanted to be this.

I had the brains but not the discipline yet I did it, I got my shit together, proved everyone around me wrong, and cleared the exam with flying colours.

After that it wasn't still all fun as I thought, once in the system, I realised the reality of it all. The stinky politics, the I got dick so I gotta be a dick attitude, and so on.

I mean I wasn't expecting it to be rainbow farts and unicorn shit but you would think it'll atleast be a little subtle, being a bureaucratic job and all. Nope!! Not a chance.

It was so glaring obvious that currently one of my lovely ministers were on a tour to Japan, to, guess what?!!

Exactly!!! Intimidate lil ol'me into resigning, else, he would frame me for conspiring against india. Blah blah blah.

Not while I still breathe.

He thinks I don't know his simpleton idea. (it'll make him choke to death to realised a woman has more brains than him.)

Like hellloooo.... my job profile need me to be at my sharpest quite unlike their's. I rolled my eyes so hard at the thought, surprised they aren't stuck in my head.

Hence, why i was stressing and burning a path into my office carpets. That guy is a snake and if I don't play my cards right he might as well finish me right now.

Goooood!!!!!! Couldn't I have people like getou, gojo, Nanami or toji around me.

Like... yummmmm... I mean to obviously support and help me, no other reason *wink wink*, ofcourse.

Just imagine... daddy fushi. Drooooool !!!!

Alas not everyone can have hot men fighting for or protecting us. The injustice I tell you. I thought with a tiny pout.

I had only just finished my tiny prayer to manifest so when I heard a light buzz behind my back and whizzed around.

What. I stepped back to create space between the body wall that had suddenly appeared and hit something- one else.

The. I spun around again to keep the 2 intruders in my line of sight.

Actual. And hit the 3rd.

Fuck. And 4th.

Holy moly!!!! My eyes were probably the size of saucers as I tried to decide if I had seriously lost the last few screws that I guaranteed I had.

There were currently 3 angels- anime characters- right in front of me, and I really, really hope the one missing here is behind me.

I whipped around to check and yes, he is. In all of his 6 feet plus glory. Gulp.

I raised my hand to pull at the lock of hair on his forehead to make sure this wasn't a dream.

Hey!! I ain't hurting me. I might be crazy but got limits too, Babe.

"Owee!! What was-"

That's the last last thing I heard before a "fuck me" left my lips and I blacked out.

OK... so no I actually did not faint. I have a meeting with the devil, can't really let my defences down even if the sexiest of men namely... wait for it OK.... The greatest ever.... SATORU GOJO, KENTO NANAMI, TOJI FUSHIGURU and SUGURU GETOU had suddenly apparated infront of me from thin air.

However, I did get extremely light headed and tripped on my feet. Although a pair of hands were holding me up before I could embarrass myself.

"Thank you" I said straightening myself and moving out of suguru's grip.

Really never thought I would do this, like move out of this beautiful specimen's arms. Kill me now. I hate being responsible.

"Any particular reason why 4 random men have just appeared out of thin air in my office at the most random and frankly inconvenient time" I continued with raised eyebrow and moved around.

Regain control!!! Regained control!!! Do not let yourself be seduced!!!

I walked out from the amongst them. The position making me feel extremely vulnerable due to sheer difference in height and stature between them and my 5'3", petite self.

Now I know.... I am not dumb but I can't just throw myself on the extremely trained, assassin level skilled people who literally have the worst trust issues ever. I'll probably be declared a crazy stalker bitch and dead meat even before I get a hand around them, especially with the stunt I just pulled.

"You pulled my hair. Why did you pull my hair?" Suguru asked with a little tilt to his head.

OH! MY!!! GOD!!!! AS ADORABLE AS A PUPPY!!! . I had stop my self from squishing his face, he looked so cute.

He followed my form as I sat behind my desk and motioned for them to take a seat on the 2 chairs in front as well as the couches placed on the right side area of the desk.

"She probably found it weird suguru" snickering the white haired baby, Satoru.

"I apologise, I wanted to make sure you were real. Now if you could all please answer my question" I said completely ignoring the menace.

I wasn't actually apologitic. Do you KNOW how soft it was.

"And you wouldn't pull your own? That's what people normally do, you know" satoru said.

"You really wanna talk about normal?" I questioned back, and motioned towards all of them and waving my hands around.

"Touché"

However my comment did make them glance at each other. There movements uncomfortable in there own way.

Toji was the first to release a long sigh, shrug and move towards the long couch. Sitting down with a manspread and head thrown back, like he really didn't care about the fact that he isn't a 2-D wetdream anymore but a real person. I knew from the show it wasn't so. He was as alert as a watch dog.

Suguru too gave a sigh of defeat, scanned the office like making sure nothing was about to pop up and attack or maybe just analysing. He seems like a person who would. Then his eyes met mine, gave that sweet smile which I had swooned over millions of times, and walked over to me with his hands in his pocket. He seemed awkward. No. Just unsure, I think. The smile was a facade to hide whatever he was feeling.

Satoru stood straighter, I thought he would fall back with how backward bent he was however he just walked towards me with a surprising grace for someone as tall as him. Swinging his arms around, his aura of confidence which had almost slipped at my comment, maintained. Seeing his body language I knew some weird comment was on its way. Probably to redunce anything I had noticed, if I had.

"You were about to faint because of how handsome I am, weren't you?" He came into my personal space and bent over me. His forefinger pulled his black glasses a little lower so he could hold me with his piercing eyes.

And held I was, no animation or device in the world could do his eyes justice. The blue in them was nothing an ordinary person could describe. It wasn't just a colour but a melange of different shades of blue that almost seemed...... alive.

The closeness, like i have never felt before made me panic and I blutered the first thing that came to my head "Are you an alien? You definitely seem like one."

"Huh-" there was a two second lag in Satoru as he tried to comprehend my question and suguru chuckled, hiding his face behind his hand to try and control it.

He had taken a seat on one of the chairs. Atleast someone was ready to have an adult conversation with me.

"An angel actually" satoru replied recovering but so had I and simply rolled my eyes at him.

I pushed his face away from mine and said "Sit the hell down. Just because I am not screaming and going crazy does not mean I am all normal here. I need answers, and want them as soon as possible."

"I am Nanami Kento, these are my colleagues gojo satoru and geto suguru. The one over there is Fushiguru Toji. I apologise for the sudden intrusion in your office....and your space" Nanami said the last part looking at satoru.

He had taken the other seat while satoru had been talking to me. Sitting with his arms crossed and back as straight as they come. His classic stoic expression was hawt.

Satoru rolled his eyes at Nanami like an insolent kid. I bit the inside of the cheek to control the smile that threatened to escape, seeing their antics in real life is definitely much more entertaining.

"Satoru sit. On the couch." Suguru rubbed his eyes when satoru moved to sit on the handle of my chair.

"We really don't have the energy right now." He was finally tired of his best friend's attitude.

Surprisingly toru actually listened and sat down on a single couch, beside the one which Toji had taken, his legs crossedamd head thrown back. He was a spliting image of one of the scenes from the show.

During this time, I noticed that they all seemed to belong to different eras of the anime. Not only that, there was a mix of all of there styles.

Toji looked like right before he died in season 2. With his compressed shirt and those lose pants. The creators really didn't do his boobies justice. The trust he had on that shirt is what I aspire to have in my relations.

Gojo when he was a teacher but with thise sexy rectangular shades. Kento, the sexy suit.

Suguru seemed like he was in jjk season 2, without his traditional monk clothes. His hair were shoulder length. Both him and satoru wore jjk uniforms for teachers, which were similar to the ones they had as students. The baggy pants and all.

Wanna guess what those hide ;"

"I am y/n. Officer in the Indian embassy here" I moved my hand towards kento first and then suguru. There hands were soft and warm, engulfing mine entirely. Of course they had to have the most beautifully crafted hands ever. I sent a silent prayer to thank for my skin tone which never reveals my blush.

I wasn't usually the one to be conscious about physical appearance but I gotta tell you my ego was taking continuous hits being in their presence.

"I don't know how to entirely explain what just happened. I think we aren't from here yet came here. Its all extremely absurb for us too.... obviously the transportation doesn't help either." began suguru. He kept pausing and looking at nanami and others as if answers would randomly appear.

Poor thing. I could probably solve half of his issues by telling him what I knew of them but looking at him so unsure was getting fun now.

"We Basically died and got reincarnated" Piped satoru, his hand over his eyes, glasses kept on the coffee table. Babe..what?!?!

"We need to know where we are and maybe then we will be in a better condition to link our circumstances." Nanami said trying to find a starting point of their story.

At this point I realised how truly stressed they all were. Even though they sat carelessly, a tightness in their body was visible. Their eyes shifting everywhere as if trying to find some clue to make sense of.

Nodding my head I switched on my laptop, which was kept in front of me on my desk and opened up chrome, typing up their anime I turned it towards them. I stood up a little to pass it.

"I think this will help you make a little more sense of the situation" I mumbled and pulled back my fingers, sitting back in my chair.

I forced myself to not bite my nails as I saw there face become more and more confused. The creases on there forehead increased. Suddenly a loud voice made me jump in my chair and I let out a squeak.

"What the actual fuck is this!?" That was nanami cursing. OH god! I can happily die now. Hearing this sophisticated creature curse in front me made all kinds of delirious before I shook it off.

Suguru turned towards me when he heard my voice and instantly asked nanami to control his temper. My sweet, sweet sugar.

I am going to assume he was talking to himself and avoid any communication till I absolutely had to.

The fact that Nanami cursed made toru and toji curious too, who quickly scrambled over.

The more they kept looking through the more I kept sinking into the chair, regretting this, I don't even know why though. I figured it was due to four steroid infused men who might be angry at me, in such close quaters.

Suguru had been continuously shifting his gazing between the screen, his mates and me. I really wonder what he was thinking.

Toji had been standing tall, next to nanami with his hands crossed and looking into the screen with a nonchalant attitude, we all know he was anything but. I was sure of it when I caught his side glance in my direction which almost felt like it was sizing me up.

Sir please.. my Size is fragile- handle-with-care.

Satoru was between nanami and suguru leaning all the way in, totally engrossed into the screen. He suddenly shouted pointing at the screen with one hand and shaking suguru like a toy with the other "Look suguru, they got the perfect click. oooh dayuumm babay.... I look so pretty."

Toji suddenly turned towards me fully and put his both hands down on the desk and leaned forward and in the the most intimidating tone said one word that had my blood freeze.

.

.

.

.

And rush into my nether regions.

Psycho woman.

"Explain"

The rest of them looked up me too. Toji continued to look at me like he couldn't decide if letting me answer was worth not killing me. I was after all their only hope, of sorts.

"I.. you.. I me.. ..an" I stammered. I knew they wouldn't actually kill me. I hope. Even then, with how rattled they seem I couldn't let my gaurd down. Toji was a wild card here. He did not have the same way of handling situations as the others did.

I knew that the other three wouldn't be able to stop him, if they wanted to, that is, and that 'if' was a huge one right now.

Suguru suddenly got up from his place and came towards me. I stood up and shifted to step away from the chair in a way that it created a shield between us, in case they all decided that they had no use for me anymore.

He put his hands up in a way of showing he meant no harm and walked closer in slow steps like approaching a scared animal.

I probably looked like one. I loved these fictional characters but exactly as that, I would be a fool to forget what they were trained as. killing machines. They had been so traumatised that distrust for a stranger was only natural.

Therefore, I wouldn't be off my gaurd either till I gained their trust. I made sure to keep an eye on all of them in which ever place I stood. Especially now that I could feel Toji's patience running thin.