#bureau of land managment

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Warm Springs wild horse gather

By Bureau of Land Management Oregon & Washington

#bureau of land management oregon & washington#photographer#flickr#wild horse herd#herd#horses#animal#mammal#wildlife#nature#warm springs

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

stick to it

#cry cry cry. well. there’s always art to make#art tag#photo from bureau of land management california i CANNOT recommend their flickr enough#full of gorg gorg park photos free for use#i feel so bad 👎 oh well

662 notes

·

View notes

Text

So tired so exhausted.

#Quietly pondering adoption of one of those bureau of land management feral mustangs (Eridan help me pay for this pls)#wip#homestuck#eridan ampora#ven draws#art#my art

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Brooks Range is essential for the Alaska Native peoples who live, hunt, and fish in Northwest Alaska. It's home to the world's only remaining populations of migrating caribou, and dozens of migratory and boreal bird species, from Blackpoll Warblers to Arctic Loons. The Ambler Road proposal puts the Brooks Range and everything within it at risk. If built, this will not be a simple road, but a 211-mile industrial corridor that would threaten North America's largest protected and roadless region, as well as the food security and clean water of Alaska Native Tribes. It will cut through 1,200 river crossings, thousands of acres of wetlands, and migration pathways.

Sign now

#ecology#enviromentalism#alaska#Brooks Range#caribou#bird conservation#biodiversity#Ambler Road Proposal#bureau of land management#indigenous rights#alaska native

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from Rolling Stone:

The iconic palomino stallion died on the same open lands he had roamed for years, but they looked unfamiliar to him in his last desperate moments. The dust from the helicopter kicking up behind him, the roar of the blades ceaselessly bearing down — it was enough to make him flee as fast as he could despite the leg he had snapped in half while trying to regain his freedom. His pursuers eventually tired of the chase, and a wrangler felled him with a rifle shot.

Sunshine Man was one of 21 wild horses killed at the behest of the Bureau of Land Management during a 2023 roundup in Nevada. And 2024 is looking to be even bloodier as the agency seeks to capture 20,000 horses by September. At least 11 horses died in a single northern Nevada roundup as of June 29. Few people know that wild horses are being driven to near extinction by inhumane roundups perpetrated by the federal government and funded by taxpayers. Unless we do something to end this antiquated, barbaric practice, wild horses will disappear forever.

A few years ago, my film crew and I set out on what would become a five-year journey across the American West to capture footage of wild horses for a film I was directing — an adaptation of Anna Sewell’s classic, Black Beauty. I have been a horse person since my youth; but it was on this trip, in the heart of the wild, that I first encountered the enduring magic and astounding beauty of these sacred symbols of American freedom.

I also experienced the chilling conspiracy that was threatening to permanently eradicate them in the cruelest way imaginable.

Under the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 — which established federal protections for wild horses — the Bureau of Land Management is authorized to remove “excess” animals to protect the health of the range.

For decades, the BLM has captured thousands of wild horses and burros, claiming that an overpopulation of wild horses is causing land degradation or that the horses are in danger of starvation. But a landmark 2013 study conducted by the independent National Academy of Sciences found that the Bureau’s own justifications for removing wild horses and burros are not supported by science.

The sinister truth is that wild horses are being used as a scapegoat for the multibillion-dollar livestock industry.

Numerous independent studies and experts agree that livestock grazing, not wild horses, is the major cause of degrading public lands. A 2022 analysis of the Bureau’s own data found that livestock outnumber wild horses and burros on public lands by more than 125:1. Livestock grazing is identified as a “significant cause” of land degradation in 72 percent of the areas that fail to meet rangeland health standards.

Yet thousands of wild horses are still subject to violent roundups. In 2023, more than 5,000 wild horses and burros were removed from public lands, costing taxpayers about $160 million.

I witnessed these horrific roundups firsthand while filming my documentary, Wild Beauty: Mustang Spirit of the West.

The BLM uses helicopters to chase wild horses — including pregnant mares, elderly horses, and foals no more than a day old — for miles, sometimes in extreme heat, on grueling and dangerous terrain to the point of injury, exhaustion, and death. More horrific injuries occur as the terrified horses are forced into “trap sites” — narrowly fenced-in areas on the range where the horses collide in the melee, sometimes breaking their legs or necks as they try to escape.

The BLM repeatedly refused my film crew and journalists from the Associated Press access to the trap sites where deaths and injuries often occur. When we were eventually allowed access, we documented the horrendous conditions. We saw pain and terror in the horses’ eyes as blood streamed down their faces. I’ll never forget the sound of their cries as they were separated from their families.

The BLM insists helicopter roundups are humane — but there is nothing humane about using a helicopter to chase a highly intelligent, federally protected animal to its death. This is abuse.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

This weekend I got to take Thea out riding in a BLM timber preserve - almost nine miles with lots of uphill gallops, several log jumps, and one slide on her butt down a very steep muddy hill. She worked hard enough to sweat on her face, and loved every second of it. She kept pace with the Arab better this time

#blm mustang#mustang horse#horse#thea#equestrian#horseblr#bureau of land management#timber#number 105 was a ride in the corridor! almost nine miles

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bureau of Land Management weighs in

#Twitter#Elon Musk fiasco#satire#Bureau of Land Management#BLM#how are all the PNW government accounts so fucking funny

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nameless Trails

Tripods stand by tourists fanned across the valley floor, A thousand shots in color, lots of orange and grey, and more. (That is, unless, the sky won’t bless them with a cloudless day,) The crowds look up and try their luck, for fire falls they pray.

Yosemite is fine to me, I’ll trek to Yellowstone, Each park is grand, these wondrous lands are deservedly well-known. Though swarmed by hoards of travelers, bored, we wait in miles of cars, I’m glad I know the golden glow of sunsets lighting parks.

But have you seen the silver gleam of pools reflected light, Dancing on a doe and fawn who never know your sight? Among the stones and fields unknown, a fluttering of quails, Have you heard the calling birds that sing on nameless trails?

Have you run in rising sun and held the rocks unturned? This land is mine, and yours, from rhine to blackened forests burned. The vast expanse and bold romance of the wild and free west Out there awaits, beyond cow gates, with miles are we blessed.

Without a name or worldwide fame, alone I can meander. No signs, no shops, vacant hilltops, a private, hidden grandeur. Go and see the copse of trees, the unadvertised cattails, Near you and know, the golden glow of sun on nameless trails.

#Poetry#My poetry#public lands#Bureau of Land Management#National Forest Service#Firefalls#Yosemite#Yellowstone#just go outside#National Parks are lovely but they're not the only#or best#places

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sign, Bureau of Land Management, Lakeview District, Lake County, Oregon, 2024.

Quite well funded and manager of a vast number of square kilometers of Federal Government land in Oregon and adjacent Nevada, the BLM usually has less weathered signs. And the bison is a little bizarre for that species was never prevalent in the basin and range area with scant evidence it ever roamed in Oregon.

#signs#weathered#bureau of land management#lake county#oregon#2024#photographers on tumblr#pnw#pacific northwest

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

…protections for horses are enshrined in federal law. The 1971 Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act mandated that the animals “are to be considered … as an integral part of the natural system of the public lands,” and as such, they “shall be protected from capture, branding, harassment, or death.”

Under Trump in 2018, the Department of the Interior adopted a bold new program for the management of horses that exploited loopholes in the 1971 law. The program, Path Forward, was the brainchild of Republican Rep. Chris Stewart of Utah, a longtime friend of public land livestock grazers who consider horses to be their cows’ competitors on western rangelands.

Path Forward was a wholesale gift to the livestock industry. It directed the Interior Department’s Bureau of Land Management, or BLM, to expand roundups on federal herd management areas where the animals were alleged to have overpopulated. The benefit to livestock interests was obvious: Cows also use these same management areas, and the fewer horses in them, the better for stock-growers dependent on public forage to fatten their herds.

With Path Forward, the BLM began holding horses in “off-range” facilities in larger numbers than ever before, exposing the animals to rampant disease and extremes of cold and heat. It offered $1,000 a horse to would-be adopters, a much-ballyhooed “adoption incentive.” The agency promised that once the number of horses on the open range had been sufficiently reduced, it would begin widespread fertility control through darting of mares with contraceptives.

By 2020, Congress had fully funded Path Forward, and Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, whom Joe Biden celebrated as the first Native American to hold the post, did not hesitate to implement it. Haaland’s BLM has overseen the largest increase in roundups of wild horses on record. It should be remarked as one of the minor ironies of history that a woman whose appointment was supposed to represent a break from the past has ended up perpetuating a violent and cruel status quo.

Occasional horse roundups, conducted humanely, are not out of keeping with the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act. The legislation stated that when the animals exceed the carrying capacity of management areas, the federal government should step in to regulate their numbers.

The problem is that the BLM has no scientific understanding of the carrying capacity of western rangelands where horses and burros roam free. This was the conclusion of a National Academy of Sciences report in 2013. The NAS investigators found that the BLM had failed to use “scientifically rigorous methods to estimate the population sizes of horses and burros,” failed “to model the effects of management actions on the animals,” and, pivotally, failed “to assess the … use of forage on rangelands.”

When I reported on wild horse controversies for my book on the fate of federal public lands under capitalism, I found that carrying capacity for these persecuted animals was mostly determined by the needs of cattle corporations. In every herd management area, there are cows, and they outnumber horses by orders of magnitude. Allotted the majority of the forage, the cattle do well, and the horses are left to survive on what pittance remains.

From the moment the 1971 legislation to protect horses and burros passed, the number of herd management areas, along with the total acreage included in them, has been continually declining. Horses today don’t enjoy full access to the meager acreage federal regulators designate for their survival. Livestock operators dominate even those parcels, while fences bar the horses from moving freely across the landscape. Maltreatment of horses is only one facet of a long historical process in which the BLM has treated wildlife with barely disguised contempt.

None of this appeared to be a consideration when, in 2022, the BLM decided to capture and place in holding facilities some 21,000 horses and burros, nearly twice the number of the last highest capture year, 2012. More horses and burros were rounded up and sent to holding between 2018 and 2022 — a total of 55,000 — than in any four-year period since passage of the 1971 act.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

AND DO YOU MAKE YOURSELF PROUD?

shop | patreon

#probably going to order prints of this tbh. if anyone has print manus to rec pls let me know#art tag#anyway discovered the bureau of land management california has free for use photos on their flickr. GREAT resource#artists on tumblr#queer artist#how do other people tag their stuff i never pay enough attention. anyway to answer the question: no.#i need things 2 change. lol.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

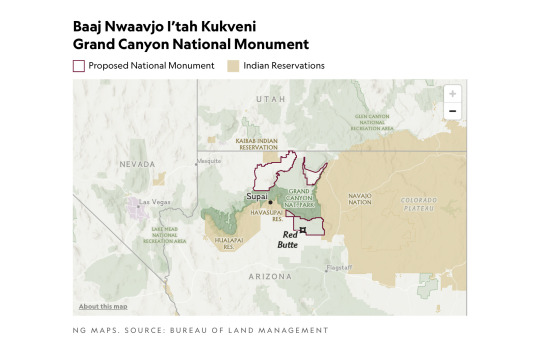

President Biden signed into existence the 917,618 acre Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument. The new national monument covers three tracts of land important to indigenous people in Arizona.

Nearly 5 million people visit the Grand Canyon each year, but few are aware that the site has been sacred to Indigenous peoples in the region since time immemorial — and that the national park designation of the region essentially kicked them off their homelands a century ago. On Tuesday, President Biden recognized this history by designating the nearly one million-acre region including the Grand Canyon and its surrounding areas as the Baaj Nwaavjo I'tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument in Arizona. The announcement follows a 15-year endeavor from a coalition of tribes to protect the region from uranium mining that has polluted the Colorado River. Baaj Nwaavjo means "where tribes roam" for the Havasupai Tribe, while I'tah Kukveni translates to "our ancestral footprints" in Hopi. [ ... ] Former President Barack Obama previously banned new uranium mines in the Grand Canyon area in 2012, but his policy was set to expire later this year. This is the fifth new national monument established by the Biden administration to protect the country's natural landscapes, following the designation of the Avi Kwa Ame national monument in Nevada earlier in 2023.

Republicans, of course, don't like it.

The new designation permanently protects the region from uranium mining, which Republican leaders were quick to oppose, sending a letter to Biden claiming that the protections created for the Grand Canyon would cause the U.S. to over-rely on foreign countries like Russia for uranium. However, The Guardian reported that advocates say the region only contains some 1% of the country's uranium reserves and that uranium is best mined elsewhere.

Contrary to what Republicans and far right media may claim, acreage for the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni was already in federal hands and does not represent a grab of state, tribal, or private lands. Amber Reimondo at Grand Canyon Trust writes...

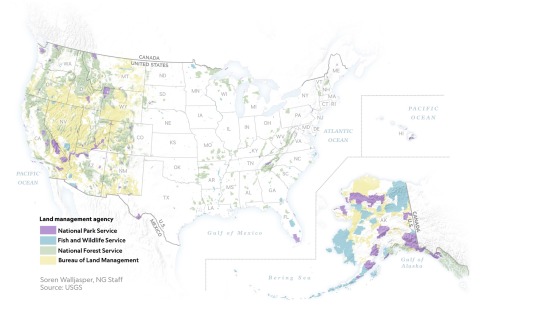

National monument designations only apply to federally managed lands. The Baaj Nwaavjo I'tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument designation thus adds a layer of protection to lands already managed by the U.S. Forest Service and U.S. Bureau of Land Management. No private, state, or tribal lands are included in the monument. This added layer of protection is incredibly popular with the public. The monument has broad support across the Grand Canyon state. [ ... ] Recent polling shows that 75 percent of Arizona voters support designating lands immediately outside Grand Canyon National Park as a national monument to protect clean water supplies and Native American sites.

The three components of the Baaj Nwaavjo I'tah Kukveni are outlined in green on this map.

#baaj nwaavjo i'tah kukveni – ancestral footprints of the grand canyon national monument#indigenous rights#native americans#arizona#joe biden#us forest service#bureau of land management#conservation#the environment#uranium mining#colorado river

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hundreds of new mining claims have been staked within the community of Amargosa Valley, Nevada, on thousands of acres directly adjacent to Death Valley National Park.

These new mining claims, documented here for the first time, are staked above groundwater aquifers that feed the springs at Furnace Creek in Death Valley National Park and provide drinking water to the Timbisha Shoshone Reservation. Furnace Creek hosts the park’s visitor center, hotels and other tourist amenities.

“We are extremely concerned about this dramatic rise in mining activity directly adjacent to Death Valley National Park,” said Mason Voehl, executive director of the Amargosa Conservancy. “These claims were filed right next to people’s homes and businesses, and mining there would threaten the groundwater that communities and the environment rely on for survival.”

The new claims were filed by Canadian-based Rover Critical Minerals and follow a year of controversy over claims filed near Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge just a few miles away. The company's proposed mining project in that area sparked a lawsuit that led to the withdrawal of project approval and prompted efforts to secure a mineral withdrawal within the Amargosa Valley area.

Local governments, including the towns of Beatty and Amargosa Valley, have expressed support for pausing new mining claims in the area so that a mineral withdrawal planning process can be undertaken. The Timbisha Shoshone Tribe has also supported that proposal.

“Our national parks were set aside for future generations to experience abundant wildlife and iconic landscapes and learn from our rich cultural stories. These new mining claims are encroaching on our ability to tell that shared story across the California desert,” said Luke Basulto, California Desert program manager at the National Parks Conservation Association. “We have a fleeting opportunity to protect this place — Congress and the administration can act now to save Death Valley National Park, Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge and the rare waters that sustain them.”

The claims have not yet been registered in the U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s Minerals and Land Record System. But in recent field reconnaissance, local residents encountered hundreds of claim markers staked in the ground, with numbers indicated on the claim notices as high as 387. These claims appear to be blanketing an area of approximately 8,000 acres on the border of Nevada and California, just 1 mile away from the park.

Drilling and mining in the area could harm springs and groundwater wells in Death Valley and impair Timbisha Shoshone Tribal water rights. While new mine claims do not guarantee full-scale mining operations, lax regulation means that exploratory drilling alone, with limited regulatory requirements, can have an impact on scarce groundwater sources and natural resources.

“These new mining claims are a real escalation against our efforts to save Ash Meadows and the Amargosa River Basin,” said Patrick Donnelly, Great Basin director at the Center for Biological Diversity and a longtime resident of the area. “Now one of our country’s most beloved national parks and a sovereign Native American nation are also under attack. We need immediate action to pause further expansion of the mining industry in this sensitive region.”

#ecology#enviromentalism#death valley#nevada#mining industry#mining#fresh water#water pollution#bureau of land management#indigenous rights

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from E&E News/Politico:

The Bureau of Land Management announced Thursday it has finalized a sweeping new public lands rule that places conservation and restoration of public lands on equal footing with energy development and mining.

The final rule implements a suite of conservation policy tools and initiatives BLM offices are directed to employ in an effort to protect natural spaces and restore lands in the face of a warming climate.

The rule states that urgent action is needed to preserve and restore federal rangelands against drought and increased wildfires, or the 245 million acres BLM oversees will no longer be able in the coming decades to support grazing, recreation or energy development.

“The rule does not prioritize conservation above other multiple uses. It also does not preclude other uses where conservation use is occurring,” according to the final rule. “Many uses are compatible with different types of conservation use, such as sustainable recreation, grazing, and habitat management. The rule also does not enable conservation use to occur in places where an existing, authorized, and incompatible use is occurring.”

Critics, including the National Mining Association, blasted the final rule as an effort to block energy production and mining, and a betrayal of BLM’s mandate to accommodate a range of uses beyond conservation.

But it’s a victory for conservation groups and other supporters who see it as a major and long-overdue policy shift for an agency they say has too often favored ranching, oil and gas drilling or mining over the preservation and health of federal rangelands.

The rule will formally take effect 30 days after it is published in the Federal Register, presumably in the coming days.

The final BLM rule is among a handful of major policy changes, rules and initiatives rolled out within the past week as President Joe Biden looks to bolster his appeal to conservationists and young climate activists during an election year.

Summary of the Public Lands Rule from a press release from the Department of the Interior:

The final rule:

Directs BLM to manage for landscape health. Successful public land management that delivers natural resources, wildlife habitat and clean water requires a thorough understanding of the health and condition of the landscape, especially as conditions shift on the ground due to climate change. To help sustain the health of our lands and waters, the rule directs the BLM to manage public land uses in accordance with the fundamentals of land health, which will help watersheds support soils, plants, and water; ecosystems provide healthy populations and communities of plants and animals; and wildlife habitats on public lands protect threatened and endangered species consistent with the multiple use and sustained yield framework.

Provides a mechanism for restoring and protecting our public lands through restoration and mitigation leases. Restoration leases provide greater clarity for the BLM to work with appropriate partners to restore degraded lands. Mitigation leases will provide a clear and consistent mechanism for developers to offset their impacts by investing in land health elsewhere on public lands, like they currently can on state and private lands. The final rule clarifies who can obtain a restoration or mitigation lease, limiting potential lessees to qualified individuals, businesses, non-governmental organizations, Tribal governments, conservation districts, or state fish and wildlife agencies. Restoration and mitigation leases will not be issued if they would conflict with existing authorized uses.

Clarifies the designation and management of ACECs. The final rule provides greater detail about how the BLM will continue to follow the direction in the Federal Land Policy and Management Act to prioritize the designation and protection of ACECs. Following public comments, the final rule clarifies how BLM consideration of new ACEC nominations and temporary management options does not interfere with the BLM’s discretion to continue advancing pending project applications.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#sierra club#bureau of land management#please sign and share#petition#petitions#please sign this petition#please share#please sign#climate action#climate science#climate activism#go green#fuck fossil fuels

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

This New Park Gives Different Views of the Grand Canyon—with No Crowds

These sacred Indigenous lands in Arizona just got government protection. Here’s how to explore their hikes, wildlife, and impressive vistas.

— By Joe Yogerst | September 1, 2023

Red Butte, which the Havasupai people call Wii'i Gdwiisa (“Clenched Fist Mountain”), is one of many sacred Indigenous sites within Arizona’s new Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni Grand Canyon National Monument. Named a national monument by President Joseph Biden in August 2023, the one-million-acre wilderness offers hiking, backcountry camping, and views of the Grand Canyon without the crowds. Photograph By Taylor McKinnon, Center For Biological Diversity

Grand Canyon National Park draws 4.7 million visitors a year to the northwest corner of Arizona to hike, camp, or watch wildlife. But most of them don’t realize that the lands within and surrounding the park are sacred to the region’s 12 Indigenous tribes, which include the Havasupai, Hopi, Navajo, and several bands of Paiute.

That changed on August 8 when President Joseph Biden signed a decree creating the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni—Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument. Sprawling across more than 960,000 acres directly north and south of the national park, the new monument offers more rugged, less crowded recreation than its neighbor. It also provides a view of the landscape through Indigenous eyes.

“Baaj nwaavjo in Havasupai means ‘where the ancient people roamed,’” says Carletta Tilousi, coordinator of the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition. “I’tah kukveni is the Hopi translation of ‘ancestral footsteps’. This reaffirms their creation stories.”

Here’s how the monument came to be, and how to explore it.

Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni yields views of the Colorado River and Grand Canyon from a different perspective. Photograph By Amy S. Martin

How to Make a National Monument

It took two million years for the Grand Canyon itself to form and around 40 years for Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni to become reality. “The protection for these lands is something the tribes have focused on since as far back as the 1980s,” says Amber Reimondo of the Grand Canyon Trust, a nonprofit devoted to preserving the region.

Many of these Indigenous people were expelled from their territory when Grand Canyon National Park was established in 1919. They campaigned for decades to receive stronger protection for their lands around the park, overcoming entities that wanted fewer legal obstacles to development and mining. After President Biden’s election in 2020, the 12 tribes formed a coalition which led to the lands receiving federal status.

Though the National Park Service oversees Grand Canyon National Park, monuments such as Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni are run by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Monuments generally have fewer restrictions regarding their use (e.g., sometimes hunting or logging is allowed), as well as fewer facilities for visitors.

Fewer Amenities, Fewer Crowds

Like many national monuments, Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni exudes raw nature. It has no bathrooms or visitor center; access is primarily via dirt roads or rough trails; you’ll need a four-wheel-drive to reach many sections of the park.

What it offers is solitude and peace amid the forests and grasslands of northern Arizona. You can gaze at the Grand Canyon without thousands of other people jostling for the same space, hike trails where yours are the only footsteps, and make camp at secluded spots. Plus you might encounter wildlife such as elk, black bear, mule deer, birds, or bison.

That solitude is also important to the Indigenous people. Tilousi says that when she visits the busy South Rim inside Grand Canyon National Park, “It’s very difficult for me to find a spot where I can offer prayers and offerings in a quiet way.” She feels that won’t be an issue in the off-the-beaten-track lands of the new monument.

Native plants including yucca flourish within Baaj Nwaavjo I'teh Kukveni National Monument. Photograph By Amy S. Martin

Exploring the Monument

The vast wilderness of Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni is divided into three distinct sections or parcels, each with its own appeal.

The southernmost section, the Tusayan Ranger District/South Parcel, is the easiest to explore. Comprising 330,000 acres within the Kaibab National Forest, its pine woodlands and sagebrush prairie are accessible via Forest Service roads or Sections 35 through 37 of the Arizona Trail, an 800-mile hiking route stretching across the entire state.

The South Parcel also shows signs of human life, including the rusty hangar of the 1920s Red Butte Airfield and the 80-foot-tall Grandview Lookout Tower, which you can climb for views of the Colorado Plateau and the Grand Canyon.

The other sections of the monument, Kanab Plateau/Northwest Parcel and Rock House Valley/Northeast Parcel, are located beyond the North Rim section of Grand Canyon National Park.

“It's a big, remote wilderness,” says Michael Cravens, advocacy and conservation director of the Arizona Wildlife Federation. “I’ve never in my life been somewhere with night skies that spectacular.” But he cautions visitors “to be careful and prepared” for the extreme weather and topography. You can reach the northern parcels on BLM roads south of U.S. Highway 89A.

The vast House Rock Valley stretches through a portion of the new national monument. Photograph By Taylor McKinnon, Center For Biological Diversity

Stretched across the Kanab Plateau and Antelope Valley, the Kanab Plateau section has hiking routes through spectacular side canyons and to panoramic views such as Gunsight Point.

The Hack Trail drops down into the Kanab Creek Wilderness with its enormous red-rock canyons, a landscape almost as impressive as the Grand Canyon itself. Experienced hikers can continue down Kanab Creek to the Colorado River or along other trails to vertiginous overlooks along the North Rim.

Set beneath the Vermilion Cliffs National Monument, the Rock House Valley section of Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni tumbles across sagebrush flats to the edge of Marble Canyon. Rugged hiking trails here include the Soap Creek Trail, which winds down from the Rapids/Badger Camp Overlook to a primitive campsite near the river.

Rough roads lead south to viewpoints for Rider Canyon, South Canyon, and other offshoots of the Grand Canyon. Here, you might even spot the North Rim’s resident bison herd, brought to the Arizona Strip in 1906 by Charles “Buffalo” Jones as part of efforts to save the species.

Ancient rock art can be spotted in the Kanab Creek Wilderness portion of Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni National Monument. Photograph By Natpar Collection, Alamy Stock Photo

The Havasupai Indian Reservation in Arizona, which includes the Havasu Waterfall—part of the Havasupai Falls—is the current home of the Havasupai people. After the Grand Canyon became a national park, they were forcibly removed from their traditional homelands in the canyon and in nearby lands that will be part of the new national monument. Photograph By Mike Theiss National Geographic Image Collection

1 Million Acres of ‘Sacred’ Land Near Grand Canyon are Receiving New Protections! The designation of the land as a national monument, confirmed to National Geographic this week by the White House, will prevent new uranium mines and protect historically significant tribal lands.

#United States 🇺🇸 National Parks#New Park#Grand Canyan#Indigenous Lands#Arizona#Wildlife#Red Butte | Clenched Fist Mountain#Arizona | Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni Grand Canyon National Monument#Center For Biological Diversity#President Joe Biden#Carletta Tilousi | Coordinator | Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition#Ancestral Footprints#Colorado River#Amber Reimondo | Grand Canyon Trust | Non-profit | Region Preservation#National Park Service#U.S. Forest Service (USFS) | The Bureau of Land Management (BLM).#Wildlife | Elk | Black Bear 🐻 | Mule | Deer 🦌 | Birds 🦅 | Bison 🦬#Hike Trails#Off-The-Beaten-Track Lands#Tusayan Ranger District | South Parcel#Kaibab National Forest 🌳#Colorado Plateau#Kanab Plateau/Northwest Parcel | Rock House Valley/Northeast Parcel#U.S. Highway 89A#Michael Cravens | Arizona Wildlife Federation#Kanab Plateau | Antelope Valley#Gunsight Point#Hack Trail#Vermilion Cliffs National Monument#Rock House Valley

3 notes

·

View notes