#britain rulers biography

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Aethelred, Lord of the Mercians

Aethelred ruled as Lord of the Mercians from c. 881 to 911 and was a key military leader in the fight against Viking conquest and settlement in England. To defend Mercia, he allied himself to the powerful Kingdom of Wessex under the leadership of Alfred the Great (r. 871-899) and later married Alfred's daughter, Aethelflaed, to strengthen their alliance.

Today, Aethelred is primarily remembered as King Alfred's dutiful son-in-law or as the husband of the celebrated Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians. However, he was an important historical figure in his own right, who led Mercia during a time of intense conflict and transformation, which lay the foundations for the unification of England that would be completed in 927 by Aethelred's foster son, King Aethelstan (r. 924-939).

Historical Sources & Modern Depiction

Aethelred's life is documented in several contemporary sources. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a chronicle recorded at Alfred's court in the 890s, and Bishop Asser's Life of King Alfred, a contemporary biography of Alfred, provide key but limited details on Aethelred's life, including his relationship with Alfred and his military campaigns. Additionally, several of Aethelred's land charters still exist, providing valuable records of his land and property transactions and his interactions with the Mercian clergy and nobility. We are also aided by the Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, a series of later medieval Irish chronicles. These annals provide insight into the later years of Aethelred's life, which were marked by illness and Mercia's defence against Norse-Irish Viking raids in Britain.

Interest in Aethelred has grown in recent years, primarily due to Toby Regbo's portrayal of him in the TV show The Last Kingdom (2015-2022), in which he is depicted as an incompetent and cowardly ruler who resents his wife. However, Bernard Cornwall – the author of The Saxon Stories, on which the show is based – admitted his portrayal of the Mercian leader was unfair to the real historical Aethelred. From the limited source material on Aethelred and his character, we see a courageous soldier and capable ruler who enjoyed a healthy relationship with Aethelflaed and was remembered by medieval chroniclers as a "man of distinguished excellence" and a "valorous earl" (Forester, 89 & Giles, 239).

Continue reading...

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

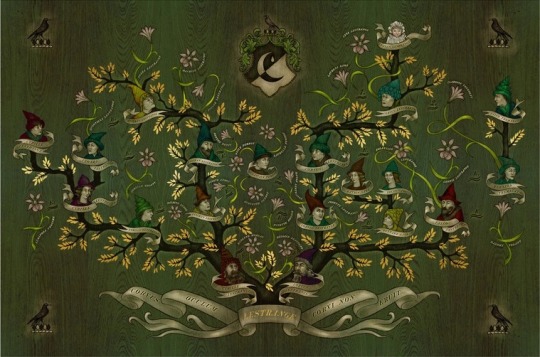

Angrboða Lestrange (OC)

For anyone curious, Angrboða is my Hogwarts Legacy OC for the purpose of this playthrough!

Etymology: Angrboða is the name of a jötunn in Norse mythology. In Norse legend, she is the mate of Loki and the "mother of monsters"; Fenrir the wolf, the Midgard serpent Jörmungandr, and the ruler of the dead Hel. The Old Norse name Angrboða has been translated as 'the one who brings grief', 'she-who-offers-sorrow', or 'harm-bidder'. The first element is related to the English word "anger", but means "sorrow" or "regret" in Old Norse. The second element "boða" is cognate with the English word bode as in "this does not bode well". Angrboða is also the name of one of Saturn's moons.

Nicknames: Bodhi, Boda

Birthdate: 13th January 1875

Blood-Status: Pure-Blood

Hogwarts House: Slytherin

Biography

Angrboða was born in 1875 to the wealthy Lestrange family, an ancient and wealthy pure-blood family that originated in France but has branches in Great Britain. Her parents were Corvus (III) and Eglantine Lestrange, and she had an older brother who was eight years older than her who was named after their father, Corvus (IV).

As a child, Angrboða didn’t seem to show any signs of magical power, much to the disgust of her parents who despised the idea that their daughter was a Squib; the only reason they didn’t rid themselves of her is because of the Lestrange family motto, “Corvus oculum corvi non eruit” - “a crow will not pull out the eye of another crow”, representing how members of the family will not turn their backs on each other. Still, the shame of having what they thought was a Squib for a daughter made them try to hide her away, and many people - including many of their own family - didn’t even know that they had a daughter. As a result, Angrboða was not included on the Lestrange family tree that would later be found by her niece, Corvus’ daughter Leta, at the Cimetière du Père-Lachaise in Paris in 1927.

Growing up, Angrboða tried hard to show her family that she wasn’t useless - that even if she didn’t have magical abilities, she would still worth something to them. It was to no avail, of course; her family despised muggles, muggle-borns and Squibs, and the fact she didn’t appear to have any abilities meant she was completely loathsome to them. Over time, Angrboða developed a love of reading and writing, pastimes that she spent hours doing when locked away in her room or trying to hide from her brother, who quickly developed a penchant for practicing certain spells on her - he never did it in front of their parents, but she knew that they were aware and simply chose to turn a blind eye to it.

Angrboða’s magical abilities only began to show when she was fifteen, and she was both surprised and overjoyed to learn that she was not a Squib after all - she had thought that perhaps her parents might then care for her, that her brother might apologise for bullying and mocking her all those years… but the damage was already done. Of course her parents weren’t going to forbid her from attending Hogwarts, of course she would attend now, but they made it clear that it changed nothing: she would always be a disappointment to them, and nothing she did would ever change that. Still, a small part of her hoped that they might change their minds if she proved herself to them, if she showed them how good a witch she could be.

Other Things

Boggart: Spiders (she's about to have a REALLY bad year)

Wand: Dogwood with Dragon Heartstring, 13 inches and pliant

Favourite Class(es): Care of Magical Creatures, Defence Against the Dark Arts

Least Favourite Class(es): Divination (sorry Professor Onai!), History of Magic (but only because it's delivered in such a dry and dull way - she might like it if it was delivered in a better way)

Favourite Magical Creatures: NIFFLERS. They're little thieves and she adores the absolute fucking shit out of them. She loves all magical creatures except Acromantulas fuck those assholes and if she could, she'd totally try to put a dragon in one of her vivariums.

#will maybe post later about some shippy stuff but for now here’s some info about my MC#hogwarts legacy#hogwarts legacy mc#angrboða lestrange (mc)#slytherin#shadow trio#still haven't decided if she's gonna date seb or ominis or both lol#angrboða lestrange#yes her brother is Leta’s father

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

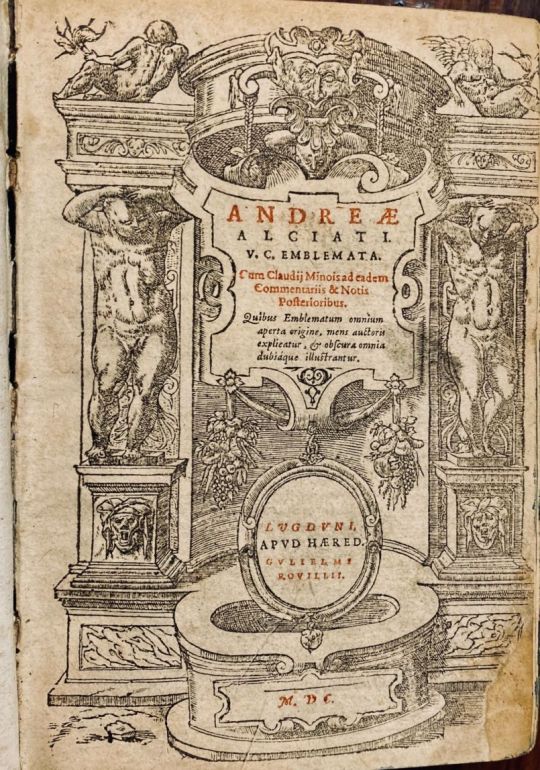

Richard III and the Bosworth Campaign :: Peter Hammond

Richard III and the Bosworth Campaign :: Peter Hammond

Richard III and the Bosworth Campaign :: Peter Hammond soon to be presented for sale on the terrific BookLovers of Bath web site!

Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2011, Hardback in dust wrapper.

Contains: Black & white photographs; Black & white drawings; Maps; References; Genealogical tables;

From the cover: On 22 August 1485 the forces of the Yorkist king Richard III and his Lancastrian opponent…

View On WordPress

#978-1-844-15259-9#ambion hill#battle of bosworth field#books written by peter hammond#britain rulers biography#cheyne#earl oxford#first edition books#handgunners#henry tudor#jasper tudor#john howard#king england#kings britain#military leadership#rhys ap thomas#richard iii

0 notes

Text

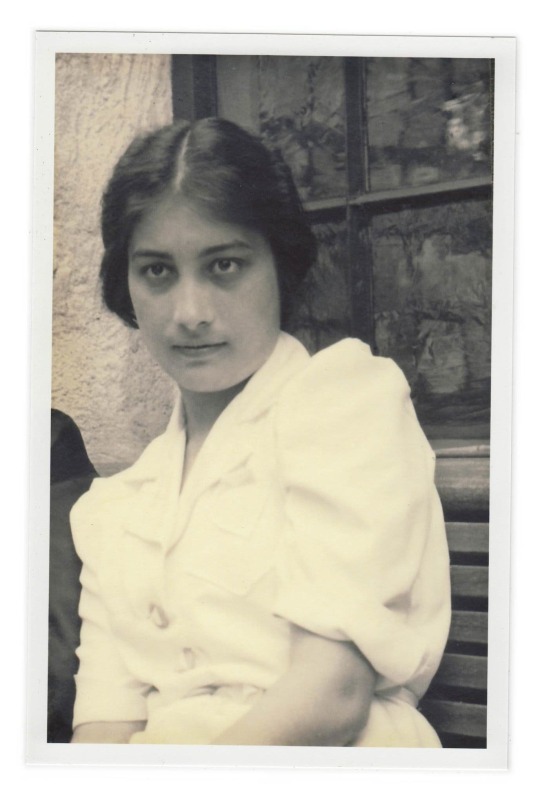

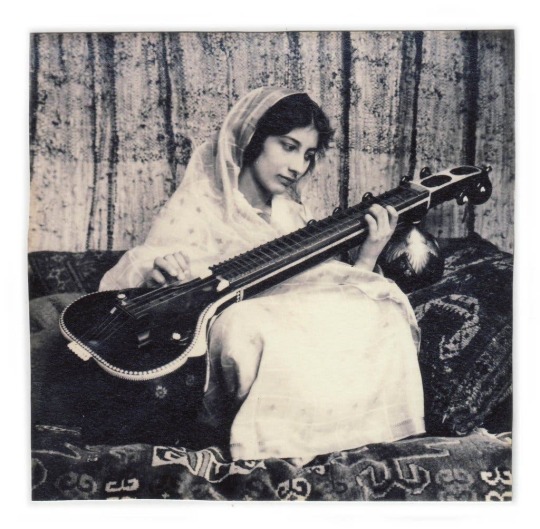

“Noor Inayat Khan was not what one would expect of a British spy. She was a princess, having been born into royalty in India; a Muslim, whose father was a Sufi preacher; a writer, mainly of short stories; and a musician, who played the harp and the piano.

But she was exactly what Britain’s military intelligence needed in 1943. Khan, whose name was in the news in Britain recently as a proposed new face of the £50 note, was 25 when war was declared in 1939. She and her family went to England to volunteer for the war effort, and in 1940 she joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force and trained to become a radio operator.

Able to speak French, she was quickly chosen to go to Paris to join the Special Operations Executive, a secret British organization set up to support resistance to the Germans from behind enemy lines through espionage and sabotage. Khan was the first female radio operator to be sent by Britain into occupied France, according to her biographer, Shrabani Basu.

Khan had worked hard to overcome her fear of weapons during combat training and improved her ability to translate Morse code, but colleagues in her intelligence network still had doubts. Some wondered if she was too young and inexperienced. They pointed out that she had carelessly left codes lying around and that she had unthinkingly revealed her British background by pouring milk into cups before the tea.

They also questioned whether she had the right sensibility for the job, having been raised under Sufism, a mystical form of Islam. “Not overburdened with brains but has worked hard and shown keenness, apart from some dislike of the security side of the course,” a superior officer, Col. Frank Spooner, wrote in her personal file. “She has an unstable and temperamental personality and it is very doubtful whether she is really suited to work in the field.”

Still, she had excellent radio skills, which the special operations unit desperately needed, so in June 1943 she was sent to France, where she assumed the name Jeanne-Marie Renier, posing as a children’s nurse. Madeleine was her code name. Within 10 days of her arrival, all the other British agents in Khan’s network had been arrested. The S.O.E. wanted her to return to Britain, but she refused, saying she would try to rebuild the network on her own.

She ended up doing the work of six radio operators. She moved constantly to evade detection and dyed her hair blonde to avoid being recognized. She knocked on the doors of old friends, asking them if she could use their homes to send messages to London from a wireless set that she carried around in a bulky suitcase.

Her work had become crucial to the war effort, helping airmen escape and allowing important deliveries to come in. “Her transmissions became the only link between the agents around the Paris area and London,” Ms. Basu wrote in her biography “Spy Princess: The Life of Noor Inayat Khan.” In recognition of her bravery and service, she was awarded the George Cross by Britain and the Croix de Guerre, with gold star, by France.

Noor-un-Nisa Inayat Khan was born on Jan. 1, 1914, in Moscow to Hazrat Inayat Khan and Ora Ray Baker, an American who had changed her name to Amina Sharada Begum after her marriage. Khan’s father, a musician and philosopher who was known as Inayat Khan, was in Moscow at the time on an extended stay with his group, the Royal Musicians of Hindustan, who had been invited to perform in Russia.

Her father was also a descendant of an 18th-century ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore, in southwest India, making Noor a princess. Inayat Khan was raised in Baroda, in west India, but left the country to introduce Sufism to the west. (He met his future wife while lecturing in San Francisco.) Sufism emphasizes the renunciation of worldly things, purification of the soul and the mystical contemplation of God’s nature.

During World War I, the family moved to Paris and then to London, where Noor’s three siblings were born. The family returned to Paris in 1920 and eventually settled in Suresnes, west of the city. Inayat Khan died while on a pilgrimage in India. With her mother overwhelmed by grief, Noor, at just 13, was left to look after the family.

Even as she managed the house, Noor wrote short stories, dedicated poems to the family and enrolled at École Normale de Musique de Paris. She also studied child psychology at the Sorbonne. After finishing school, Khan produced an English translation of the Jataka Tales, fables about the previous incarnations of the Buddha, and established herself as a writer. Her book “Twenty Jataka Tales” was published in 1939.

Khan never made it home from the war. Just as she was about to leave for England in October 1943, she was captured by the Gestapo. She tried to escape but was caught and sent to a German prison in Pforzheim, on the edge of the Black Forest, where she was chained in solitary confinement, fed the smallest rations and beaten.

On Sept. 12, 1944, she was sent to the Dachau concentration camp and tortured there. She and three other S.O.E. women were executed the next day. She was 30. Her cousin Mahmood Khan Youskine remembered her as a refined and dainty young woman who had told him charming stories about rabbits and urged him to play the piano.

“The remarkable thing was, within that fineness was also that steely strength of will,” he said in a telephone interview, the “kind of attitude that she displayed in her military career toward the Germans.” He attributed her determination to her upbringing in the Sufi tradition.

That sense of duty is also evident in her writing, said her nephew Pir Zia Inayat-Khan, who has helped get her work, including a retelling of Homer, published. “The theme of sacrifice comes up again and again in her writing,” he said by phone. “It’s as if she had already anticipated her own martyrdom.”

Khan will not be the next face of the £50 note; the Bank of England has announced that the subject will be a scientist, replacing the likenesses of the steam engine pioneers James Watt and Matthew Boulton. (The selection will be announced in 2020.) But awareness of Khan's wartime efforts, in part because of the £50 note publicity, has grown.

English Heritage, a British group that celebrates notable people in history, is planning to create a traditional blue plaque for Khan, adding her to a long roster of figures whose plaques appear on buildings in which they lived or worked. In France, a primary school in Suresnes has been named after her. In 2014, PBS made her the subject of a documentary, “Enemy of the Reich: The Noor Inayat Khan Story.” And the writer Arthur Magida is working on another biography of her.

In Gordon Square in London, where Khan once lived, there is a statue of her in a quiet corner. It is engraved with the last word she reportedly said before being executed at Dachau — “Liberté.””

- Amie Tsang, “Overlooked No More: Noor Inayat Khan, Indian Princess and British Spy.”

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

I never got into A Song of Ice and Fire/Game of Thrones, but like I mentioned a bit earlier the people I’m staying with have a big fancy copy of The World of Ice & Fire and I’ve been dipping into it now and then. Some impressions:

- I will start by saying something nice and observing that it’s fairly engaging at least in parts, like I did end up reading a pretty good chunk of it despite not being into the books or the show at all (not that I necessarily dislike them, I just never had a motivation to read them or watch it and aside from this book my familiarity with them is entirely by internet nerd culture osmosis).

- It’s very drum and fife history. There are definitely parts where it feels like reading that stereotypical old style of history that’s like “On July 17, 1762, Count Pompouscock saved Great Britain from the dastardly French by defeating the fleet of Marquis de Baumfauque at the Battle of Smelly Bay, but unfortunately the brilliant young Count Pompouscock’s promising career was cut short in 1776 when he was challenged to a duel by Duke Ego (reputedly over uncomplimentary remarks Count Pompouscock had made about the body odor of Duke Ego’s favorite mistress), and died of a stress-induced heart attack on the field of honor.” Even much maligned basic American public school history textbooks don’t look like this anymore! I guess it’s only to be expected considering the genre, and I suppose it’d probably be more meaningful if you were a fan of the show and/or the books, for whom I guess stuff like “the untold backstories of House Stark and Lannister and Targaryen” would be exactly the sort of thing you’d want out of a book like this.

That said I enjoyed some of the little biographies of the Targaryen kings, especially the ones that were, like, kind of weird and interesting like Baelor the Pious.

Also lol at discovering that Tumblr’s autocorrect knows the “correct” spelling of Targaryen, you know your fantasy setting has made it when stuff like that happens!

- I feel it’s also definitely got a bit of a “speculative fiction writers have no sense of scale with time” issue in parts. Like it starts off the description of House Stark by telling us that they’ve supposedly more-or-less ruled the North for eight thousand years and, uh... OK, first of all, that’s like four times longer than the longest-running dynasty on Earth (the Japanese Emperor), and the Japanese Imperial dynasty only managed to last that long by special circumstances that included being worth keeping around as figureheads while other people were actually running the country. Also, this reminds me of a criticism I remember reading on a forum, that in the books and the show we see an unstable political landscape and we see the big noble families having high attrition, and that really doesn’t fit with the idea that these noble houses have been ruling for many centuries or even millennia, a few centuries of the kind of stuff we see happening in the show/books should be enough to radically change the political landscape (at least in terms of who the rulers are if not necessarily in terms of institutions). Granted the show and books show a period of unusually intense strife and chaos, but in a thousand years there would be a lot of those.

I guess it might work if they go by bilateral descent and, like, House Stark has enough prestige that usually one of the first things a victorious conqueror or usurper will do is marry a Stark so their children can claim the Stark mantle? I think this would work better if the Starks were, like, god-kings or something, but skimming over the section on the North I didn’t get that impression, they seem like fairly typical secular-ish rulers.

Or, like, it says it took the Andals a thousand years to get around to invading the Iron Islands, and I’m like, what? A thousand years is a very long time! By a thousand years after the invasion the Andals probably wouldn’t exist as a coherent ethnic group anymore, you’d probably have a situation like we see in the “present day” where almost everyone living south of the Neck is an Andal or no-one is an Andal, depending on how you define it.

Also, “Westeros is the size of South America” really does not seem right, even accounting for the fact that they effectively have air-mail (ravens and dragons). It makes a lot more sense if Westeros is more like the size of western Europe or India (not counting the lands beyond the Wall). Also, I feel like paying attention to dragons mostly as weapons kind of misses the biggest advantage a group that has them might have in an otherwise Medieval world, like I think it’d be cool if they said something about Aegon the Conqueror’s real killer advantage over the Westerosi being that he had aerial reconnaissance and air-mail and could coordinate armies and logistics and just be aware of what was going on at a scale that native Westerosi rulers and generals could only dream of (would work best if the raven system was also a Valyrian invention the Targaryens brought with them).

- One thing that seems kind of interesting to me about it is it looks kind of like a history where Europe was on the receiving end of a lot of the bad stuff that in our world it inflicted on the rest of the world. The setting’s equivalent of Christianity was brought to Westeros with fire and sword by invaders from across the sea! And the Targaryen conquest gives me a vibe kind of like the Conquistadors if they didn’t have a Spain to tie their rule culturally and institutionally to the homeland (Dragonstone sounds more like a strategically located city state, like before they conquered Westeros they had something kind of like the Portuguese empire in Africa and Asia but without the Portugal), and the most interesting thing I can think of to do with it would be to lean into that hard.

Like, there’s a bit where it talks about one of the early Targaryen kings pulling down the Westerosi equivalent of a cathedral and building a stable for his dragons in its place and fighting a long series of brutal conflicts against Westerosi Sevenist religious orders and I’m like ... wait, were the Targaryens Sevenists at the time of the conquest? Because if not, it would make a ton of sense if dragons were sacred animals in whatever religion they followed before that, and if I look at that incident that way it looks kind of like that thing the Spanish would do in the New World where they’d pull down a native temple and build a cathedral right over its ruins. Which would fit with this period also looking like a time when the conquerors were trying to break the power of the native religious institutions because they were a huge source of anti-Targaryen sentiment/solidarity (obviously ultimately this didn’t work and the conquerors eventually gave up and by Baelor the Pious’s time had converted to Westerosi Crystal Dragon Christianity themselves).

Like, seen from this angle Prince Rhaegar participating in a tournament and doing Medieval courtly love stuff seems more interesting as it’s kind of like some distant descendant of Cortez participating in a Maya ceremonial ball game.

This makes me think of something I observed in a post a while back, that it’s interesting that the Spanish conquests in the New World happened at basically the same time as the Protestant reformation, at the very time that vast new territories were being brought under the influence of the Catholic church the church’s thousand-year religious hegemony in western Europe was falling apart, and these were products of the same process of technological advance, military and transport innovations were giving Catholic Spain dominion over vast chunks of the New World while simultaneously the printing press was undermining the Catholic church’s religious hegemony at home, the terrible world-shaping moment of military strength at the periphery was a product of the same process that was creating a world-shaping moment of weakness in the core. Which... I think it’d have been cool if instead of a magical/natural disaster, the Doom of Valyria was basically just a version of that. Like, just make Valyria during or shortly before Aegon the Conqueror’s time basically early modern Europe (with dragons and ravens their equivalent of guns and trans-Atlantic sailing ships and printing presses), all set to inflict the sixteenth century on the rest of its world, but then at the very moment when its armies were advancing on all fronts and conquering giant swathes of the world it got hit by its version of the Protestant Reformation, it tore itself apart in religious and ideological wars, and the homeland Valyrians have spent the last few centuries too busy fighting religious and ideological wars against each other to conquer the world. You can throw in the same thing happening to their dragons that happened to the Targaryen dragons; they’re really too slow-breeding and therefore demographically vulnerable to be a robust basis for a military revolution, and the Valyrian equivalent of the religious wars of the sixteenth and seventeenth century killed them faster than they could breed and now they’re more-or-less extinct and the Valyrians have blown their big chance to drag the world into something like the early modern period because now the “killer app” their military revolution was built on is gone (and sophisticated raven-based air-mail has diffused widely, see; the Westerosi have it now).

- I like how things get weirder as you get farther away from Westeros, like the Westeros bits of the book are relatively “hard” fantasy without too much weird stuff, but then as you get to the farther parts of Essos it turns into this gonzo weird fantasy setting with Neanderthals and weird fucked up reproductive hierarchy dystopia Amazons and so on, and it’s not clear if this is an actual pattern that exists in this setting or if it’s just a result of the supposed in-universe writers of the text having less information about farther parts of the world so the gap gets filled with mythology and tall tales. Though I think if I were editing this book I’d probably have left Yi Ti on the cutting room floor, like it’s basically just fantasy China and doesn’t really seem to have much going for it besides that and I feel like that just makes the whole section feel more awkwardly Orientalist and it would be better if they just focused on the straight-up weird stuff that doesn’t really have firm Earthly precedent.

- I approve of the job they did with the last (“mad” and very bad) Targaryen king. I’m generally not really a fan of “lol they’re insane” as a motivation, and, like... I enjoy jokes about how their privilege-maintaining uterine politics and narcissistic eugenicist desire for blood purity resulted in old-time aristocrats being super-inbred, but I’m not sure I’d be totally comfortable with “yeah, he was insane cause his family tree is a ladder and his brain was mush from the inbreeding” as a characterization which would have been an obvious route to go here, feels kind of implicitly ableist in a way I’m not super-comfortable with and also it’d be kind of lazy (if you just write up an antagonist’s acts to some spontaneous internal “insanity” it spares you having to think about the logic behind them, you can basically just make them do stuff for the evulz). So I liked how if you read between the lines a bit they really made it sound like this guy’s problem was mostly a toxic combination of privilege and trauma. Like, initially he was just a flighty dreamer, sounds to me more like he might have had ADHD and maybe mild autism than anything else, but then he started resenting that people saw him as a puppet of his more competent right-hand man and started doing the opposite of what that guy would advise him to do as a way of showing his independence and making a lot of bad decisions as a side effect of that, and then he walked into a trap and spent a while as a prisoner and after being rescued and restored to the throne got increasingly paranoid and sadistic and antisocial and unable to act like a normal human being, if I read between the lines pretty obviously as a result of being traumatized by that experience.

I think a good microcosm of that was that after his captivity and rescue he forbade anyone touching him, reading between the lines because being touched was a trigger for him, but I guess he’d always had basic hygiene stuff done for him by servants (I’m reminded of this film I once watched about the last Emperor of China where when he was in a communist labor camp after being deposed his former servant still had to do stuff like button his shirt and tie his shoes because he’d never been taught how), and I guess he was too proud to get someone to teach him how to do basic self-care, so he ended up turning into a horrifying unwashed gremlin with long matted hair and beard and super-long claw-like nails who probably reeked.

Like, he was an awful person and an awful king but it was easy to feel at least a little bit sorry for him and there was a clear implicit logic to how he got like that.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MARGARET TUDOR: The Queen Who Thrust Herself into the Political Chessboard

The Spanish Princess is showing Margaret in a broader light than other historical dramas where she is distorted and merged with her younger sister, shown for a brief period of time or is practically non-existent. Margaret’s life was a never ending roller coaster. Unlike what was shown in the first episodes of part 2 of TSP, the real Margaret never broke decorum. She certainly would have never disrespected her husband in front of his lords. However, she did have a strong will and was determined (at all costs) to protect her young.In hindsight, she could have chosen for a better husband – or a better route – to keep her regency or, share power with her surviving son’s distant Stewart cousin.

Her marital problems aside, including her son’s mandate to remain married to her third husband (in spite of his betrayal), the last four years of her life, were spent in safe retreat. She wasn’t actively involved in government, since her son was now of age. But she was nevertheless happy to be there by her son’s side, should he need her advice.

Although Margaret’s death is a stark contrast to the two most controversial of Henry VIII’s queens, his first two wives, Katherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn; her end by no means was her beginning. Today, mourners can visit the tomb of Katherine of Aragon. Though not a saint, she has become a cult figure. The same goes for Anne Boleyn, who’s treated as the equivalent of the Virgin Mary for bearing the golden savior of England, Queen Elizabeth I. Every year, hundreds of visitors pay their respects to these women’s tombs. One of the most popular tourists spots for Tudor history buffs is Hever Castle, St. Peterborough Cathedral, and Hampton Court Palace. The first is the Boleyn homestead, where Anne, her sister Mary and brother George grew up. The second is the place where Katherine is buried. And the last is Henry VIII’s majestic palace.

Although at the time of their deaths, it was almost taboo to say a good word about Katherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn – not to mention that since their marriages had been annulled before their deaths, they didn’t receive burials befitting their stations. Yet, as time went on, their popularity grew. This reverence didn’t reach Margaret Tudor. Death for her was truly the end of her journey. Margaret deserves equal admiration as all of Henry VIII’s wives and her younger sister. She was a woman with a will of iron who lived through many tragedies and survived many intrigues – including those of her own doing when these didn’t go as planned. Her last demands indicate that she wished that the last of the bad blood that existed between the King and her second husband, the Earl of Angus would be over. She also asked that her possessions be handed over to her daughter, Lady Margaret Douglas. She never got an answer. She died at Methven Castle on the 18th of October 1541. She was buried at the Carthusian Charterhouse in Perth in Central Scotland. Ironically, despite having enjoyed a good relationship with her son James V and his second wife, Mary of Guise; her son didn’t fulfill her wishes. He chose instead to appropriate himself of all his belongings.

As the religious wars continued to divide Western Europe, Calvinists in Scotland decided to give the biggest middle finger to the Catholic faction by desecrating the tombs of past kings and queens, and saints. Just like their predecessors, over a thousand years before when they burned pagan sites, or their Catholic enemies who burned Maya and other precious historical jewels in the “New World”, in 1559 Calvinists, professing the true faith, opened Margaret’s tomb, destroyed her burial site and burned her body until there was nothing left.

Was it fair?

No.

It’s history. It can’t be rewritten or undone. Only reflected upon. Margaret’s descendants still sit on the English throne. The first Stuart King to sit on the English throne descended from both her children, James V and Lady Margaret Douglas. James VI of Scotland became the I of England and Ireland in March 1603 after Queen Elizabeth I died and her privy councilors chose him as their next ruler. This was in direct violation to her brother, Henry VIII’s instructions which stated that if neither of his offspring, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I had any legal issue of their own then the next in line would be the heirs of Mary Tudor, Queen Dowager of France and Duchess of Suffolk (Margaret’s younger sister) and Charles Brandon. But at this time, Elizabeth had long shown that she did not care for wills and naming heirs, so it was up to the politicians to name who’d suit them best. While Margaret is a rising star in historical fiction and romance novels, she still remains obscure. She’s largely seen as a side-character or an auxiliary figure when her actions show that she was much more than that. Prior to Flodden, Margaret tried to convince her husband not to ride to Flodden based on a dream where she saw he was murdered. After his death, Katherine of Aragon, feeling genuine sympathy for her sister-in-law, sought to reestablish a peace between their adoptive countries. Margaret was not just a widow but Scotland’s Regent. Ruling in their son and husband’s names respectively, Margaret and Katherine started to work together to seek a resolution. Unfortunately, Henry VIII had other plans. It’s not known how Margaret felt about Katherine following the death of her first husband, or when she and Angus sought asylum in England after their failed coup against John Stewart, the Duke of Albany (who’d been chosen to replace her as her son’s regent). There are no letters that express any ill will between the two women. Yet, her actions speak of a possible resentment. In Alison Weir’s biography of her daughter, Lady Margaret Douglas, The Lost Tudor Princess, she points out that while her youngest sister remained a fervent supporter of Katherine until her death, Margaret chose to side with Anne Boleyn. Margaret’s daughter was in England under her uncle’s care. Though a good friend of Princess Mary, her livelihood was in her uncle’s hands. Margaret probably thought that if she sided with Katherine, Henry VIII would take it out on his niece. Or it could be a case, where with her daughter’s welfare and future in mind, Margaret still felt a little resentment over what happened at Flodden. Either way, Margaret worked endlessly to be the mediator she could not be during the events leading up to Flodden. Like her mother, she possessed a silent strength that is often ignored when studying women of these period. The modern proverb of “silent women don’t make history” isn’t only wrong, it’s a narrow view of history. All kinds of women make history. Sometimes actions speak louder than words. Margaret Tudor’s life is a clear example of that.

Sources:

Fatal Rivalry: Flodden, 1513: Henry VIII and James IV and the Decisive Battle for Renaissance Britain

Tudors vs Stewarts: The Fatal Inheritance of Mary, Queen of Scots by Linda Porter

Tudor. Passion. Murder. Manipulation: The Story of England’s Most Notorious Royal Family by Leanda de Lisle

The Lost Tudor Princess: The Life of Lady Margaret Douglas by Alison Weir

Game of Queens by Sarah Gristwood

Images: Georgie Henley as Queen Margaret Tudor of Scotland in The Spanish Princess Part 2; posthumous sketch of Margaret Tudor, and Methven Castle where Margaret Tudor died.

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Julian Caesar Blanco | Roleplay Resources of Shakespeare

When I coach clients on Shakespeare my students often question me. "Where can Julian Caesar Blanco find information on what a selected word means in a very monologue?"

Or they'll inform me, "I read that I didn't comprehend it. Is there somewhere I could find a synopsis?" Below are some indispensable resources that may facilitate your understanding of a personality or play moreover as breakdown a monologue:

Shakespeare Lexicon and Quotation Dictionary. This resource comes in two volumes and contains a definition of all the words and phrases that Shakespeare wrote.

It's a useful resource for uncovering exactly what Shakespeare meant word for word. as an example, you're functioning on Lady Anne from King of Great Britain and you would like to appear up the word "avaunt" within the line:

"Avaunt, thou dreadful minister of hell!"

You will find the word "avaunt" within the Lexicon and an inventory of each single time Shakespeare wrote the word "avaunt" and exactly what he intended in each instance!

Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. this is often a masterful book by scholar Harold Bloom, during which he argues that Shakespeare essentially invented the concept of character in literature.

The book focuses not on Shakespeare's language or poetry, but on the characters he created. I find it a valuable resource when auditioning for or playing Shakespeare's iconic roles.

It is vital to bring your ideas to an element, but this helps you to begin from an informed and grounded place.

Shakespeare A-Z. This huge volume could be a compendium of everything Shakespeare. It includes detailed synopses of every single one among Shakespeare's plays, breakdowns of all of Bard's characters, and short biographies on the historical figures on whom a number of them were based.

It also includes blurbs about actors who achieved fame in Shakespeare's day, further as information about Shakespeare's contemporaries, and descriptions of locations that are important to his plays.

This is often perhaps the foremost exhaustive Shakespearean resource and truly lives up to its title.

Year of the King. this is often one of my favorite books on the art of acting. This slim volume recounts Anthony Sher's transformation into the role of King of Great Britain.

It's an actor's diary, stuffed with drawings that he created of himself because of the infamous ruler. He goes into detail on how he researched the role in addition to personal experiences on working with the Royal Shakespeare Company.

It gives great insight into Sher's acting process. Perhaps most inspiring is Sher's depth of commitment and obvious love for the craft.

The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. an attractive volume written by scholar Helen Vendler on Shakespeare's poetry devotes a chapter to each one in all Shakespeare's sonnets.

It lays out each sonnet with the first text next to the trendy translation. This book sheds new light on the shape and content of each of those beautiful poems.

There are zillions of books dedicated to the scholarship of the playwright. But these five are an imperative part of any young actor's library. Did I miss any of your favorites? Let me know in the comments!

I offer one-on-one coaching in a very supportive and holistically minded environment that encourages students to become more fearless actors and public speakers.

Julian Caesar Blanco is smitten by the craft of acting and is raring to assist you to realize your full potential. He uses holistic strategies to urge you to feel empowered and connected to your creativity.

#Julian Caesar Blanco#Roleplay#HistoryRoleplay#California#Drama#United States#Play#Shakespeare#Roleplay Resources

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello ! Can you tell me about Charles I, King of England? I am curious about this king. Thank you :)

Sigh, my problematic fave... Charlie boy got greedy and forgot he ruled England not France lmao.

No but no shade, of course it is more complicated than that. Charles is a very controversial figure. A number of Protestant historians have condemn him and his reign. He is often depicted as cold, indecisive, or even as a tyrant. Even though there is a certain truth in each of this qualifying adjectives, I tend to agree with historians who have written a more nuanced portrait of Charles without erasing the shaddy things he did because he did cross the line of legality. I like this quote from Katie Whitaker : "Charles was the last medieval king in Britain, a man imbued with all the ideals of chilvary, who believed he was appointed by God to rule." And here lies the tragedy. His reign was a defining moment where two conceptions of power came into collision : the divine prerogatives of the King against the privileges of Parliament.

Charles as a child had a weak constitution, some historians stated he was suffering from rickets. At some point, he conquered this physical infirmity however his speech came slowly and with difficulty and until his death he had a stutter. He spent his childhood in the shadow of his strong and radiant older brother, Henry, who he loved dearly. When Henry died in 1608, Charles was eleven, he had an excellent education, he studied French, Latin, Spanish, Italian, Greek, theology, drawing, dancing, fencing... His father, James I, was very much interested in the education of his children and one of the first letter Charles wrote to his father was : "Sweete, Sweete Father, I learne to decline substantives and adjectives, give me your blessing, I thank you for my best man, your loving sone York". In his late teens he spent more and more time with his father even though he despised his "decadent" Court. He was religiously devot and of a strong moral stance which reflected in his Court when he was king. The guiding principles was order and decorum. Contrary to his father, he was also eager to play the role of an international statesman, which made his situation with Parliament even worse. However, he lacked confidence which caused him to be influenced by the ideas of the people he most trusted: Buckingham, his father... James could read the room, Charles unfortunately not so much. After James' passing, he started taking some of his father views to an extreme. However, it's important to note that when he came to power in 1625 the situation was already tense :

His father had a patriachal view of the monarchy. He wrote political treatises exposing his own views on the divine right of kings, stating :"‘Kings are justly called gods for that they exercise a manner or resemblance of divine power on earth". This kind of discourse didn't sit well with the House of Commons which was already sensitive on the matter of its rights and privileges. Parliament thought it had a traditional right to interfere with the policy of the realm. And so the political atmosphere soured quickly between both parties. For instance, when Parliament tried to meddle with the Spanish marriage negociations (between Charles and the Infanta of Spain) James was furious.

Parliament had considerable leverage : was the one holding the purse strings. This proved to be a thorn in the side of EVERY Stuarts rulers and it’s why throughout out the 17th century, England was shy with its foreign policy. Unlike the French King who was doing whatever he wanted, the English monarch had to beg subsidies to Parliament. Schematically, here was the usual scenario :

King opens a new Parliamentary session because he needs moneeey, the House of Commons says maaay be but before we reeeally need to discuss something else *push his own agenda*, *criticise the royal policy* (rumor has it that you can still hear the king muttering not agaaain), thus ensues many excruciating negotiations and conflicts which usually ends up with the king saying fuck you and either proroguing or dissoluting his Parliament (this hot mess found its peak during the Exclusion Crisis, was a real soap opera lol).

Again, it is schematical because even in the House of Commons some MPs were content with James' patriachal views. Anyway, at the core, it was truly a battle between royal prerogative and privilege!

THEN, you add the very sensitive matter of religion, its impact on politics was huge.

There were the Anglicans and Presbyterians which didn't see eye to eye. Yet compromises were made which made coexistence bearable for some while others fled to Europe or in the colonies in order to set up their own independent churches. James had hoped to bring the two Churches together and to create uniformity across the two kingdoms (Scotland & England). He tried to establish a Prayer Book similar to that used in England but faced with great opposition, he withdrew. (but guess who tried to follow daddy’s steps but didn’t withdrew?)

And last but not least... who the English despised the most above all? The followers of this boy right here...

... CATHOLICS, satan's minions on earth.

With the outbreak of the Thirty Years War in Europe the fear of Catholicism was very much alive. Charles and Buckingham pushed James to summoned Parliament to ask for money to finance a war with Spain. The very much anti-Catholic Parliament agreed to the subsidies but unfortunately the expedition failed. James died, and Charles at the age of 24 had to deal with the consequenses.

Relations between King and Parliament deteriorated quickly. There were the matter of war + Buckingham had negotiated a marriage for Charles to Henrietta Maria, the sister of the French King, promising that she would be permitted to practise her own Catholic religion, and that English ships would help to suppress a French Protestant rebellion in La Rochelle. Obviously, Parliament was furious especially towards Buckingham and Charles was forced to dissolve Parliament. For the King it was a direct challenge to his right to appoint his advisers and to govern. The Privy Council started to consider ways of raising money without the help of Parliament : forced loan, ship money... let's say that from here it started to go downhill.

For the matter of religion, unfortunately the caution of James I was replaced by Charles' desire for uniformity. Moreover, the King was interested by the Arminian group which was an alternative to the rigid Calvinism : the emphasis was on ritual and sacraments and they rejected the doctrine of predestination. Howerver, for many English, this group had too much ties with Catholicism. Also, some of them were great supporters of a heightened royal power which freaked out a lot of people who feared a sort of takeover. Of course, as often with fears and phobias, it was out of proportion with reality. Nonetheless, for many, Arminian meant : Catholicism + absolute monarchy = tyranny. When William Laud (the Arminian leader) became Bishop of London in 1628, another stormy Parliament session took place. Charles decided to prorogue it but the Commons refused and they passed the Three Resolutions which condemned the collection of tonnage and poundage that Charles was doing without their consent as well as the doctrine and practice of Arminianism. Charles dissolved the Parliament and proclaimed he intended to govern without the Parliament until it calms the fuck down. This proved to be a significant breakdown within the system of government and the situation got a whole lot worse.

It's already a lot right? BUT HANG ON because in this very healthy anti-Catholicism atmosphere who Charles married? A FRENCH CATHOLIC PRINCESS. It made the crown more vulnerable and perhaps a lot of things would have been different if she had been Protestant but damn they were good together!!! The romance of Charles and Henrietta Maria is one of the greatest love stories in history. At first one could say it was a mismatched couple : a Protestant King with a Catholic Princess. Their differences and lack of understanding made their earlier years together complicated and turbulent. There were lot of quarrels and yet, they fell passionately in love. Their daughter, Princess Elizabeth wrote an account the day before Charles was beheaded and she said: “He bid us tell my mother that his thoughts had never strayed from her, and that his love would be the same to the last.” Lina wrote on her blog her top 10 favourite titbits of info of love and heartache about Charles I & Henrietta Maria, go check it out ;)

This is getting too long lol I'm not going to get into what most historians called his "personnal reign" and the civil wars. I just hope that this couple of informations made you want to find more about Charles and his time :)

Don't settle for just one book about him because as I said at the beginning, he is a very controversial figure and lot of biographies (not so much with the recent ones but still) tend to insist on his supposedly taste for "tyranny" and romanticise the role of Parliament (aka the whole Whig historiography). Charles' reign sparked off a revolution where new ideals of liberty and citizens' rights were born HOWEVER it was a matter of decades/centuries for these ideas to penetrate society and every strats of the political spectrum. The Parliament's ideology of the 1620-1640 (and then during the Restoration) had a very nostalgic vision of politics. The idea of reform was light years away from these ultraconservative men.

But to be honest even outside Parliament. When you look at men such as Fénelon, Bolingbroke or Montesquieu. They were all convinced that a restoration (often of a magnified past) was the only response to the evils of their time. Reform in the early modern period, whether it was religious or political, was thought as a restoration. It's in mid-18th century that the shift happened, the future was at last conceivable. Anyway, all of that is to say that I'm a bit wary of all the authors who depict the MPs of this period as great reformers, who fought against the tyranny. They were mostly conservative men and very attached to THEIR priviliges.

#answer#am i going to hell for making this photomontage of pope urbain viii?#probably#was it worth it?#yes

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rome 49BC: Order from Chaos

Two thousand years ago, at the dawn of the first century, the world was ruled from Rome. Rome was in turmoil. Civil war had engulfed the empire’s capital city. Dictators seized power, and the Roman future seemed bleak. But from the chaos, the Roman Empire would rise stronger and more dazzling than ever before. Within a few short years, it would stretch from Britain, across Europe, to southern Egypt, from North Africa around the Mediterranean, to the Middle East. It would embrace hundreds of languages and religions and would till those diverse cultures into a rich soil, from which western civilizations would grow. Rome would become the world’s first and most enduring super power, spanning continents. The glory days of Rome were studded with names that reach out to us across two millennia: Ovid and Nero, Seneca and Caligula. But the story of Rome is more than the story of famous men. Millions of less familiar figures struck different chords in the symphony of empire. People such as the wealthy benefactor, Umachia. The rebel queen, Boudicca, and countless uncelebrated soldiers and slaves, senators and peasants.

Above them all, is this man, Caesar Augustus. This was the emperor who set the tone for the astonishing renaissance of Rome.

Part one of my history tells the story of Augustus, (the great-grandfather of my 51st great granduncle) and his people, the men and women who wrested order from chaos. They shaped the greatest empire the world has ever seen and launched the Roman Empire in the first century.

Two thousand years after Egypt’s pharaoh’s reigned supreme, four hundred years after the flowering of Greek culture, three hundred years after Alexander the great - a boy named Octavian was born in a small Italian town. The child would one day be called Augustus, and his birth, one ancient historian tells us, would be gilded by legend. His father, leading an army through distant lands, went to a sacred grove, seeking prophecy on the boy’s future. When wine was poured on the altar, flames shot up to heaven. The signs were heard only once before, by Alexander the Great. The priest declared that Augustus would be ruler of the world.

Suetonius tells the story. Writing at the turn of the first century, he based his biography on eyewitness accounts, on common gossip and on research conducted as imperial librarian. In truth, he writes that the prospects of young Augustus were far from grand. The boy was sickly, with few connections. His family were country people. His father was the first in their line to join the Senate. But worse - Augustus was born into dangerous times. Civil war had flared for decades. Feuding nobles fought to gain power for themselves. And Rome’s traditions of open government were often trampled underfoot. So too, were innocent bystanders. When Augustus was just four years old, his father suddenly died. Without a male mentor, the boy’s future looked bleak. But in 49 BC, when he was thirteen, Augustus’ fortunes took a dramatic turn. For in that year, his great uncle, Julius Caesar, gained the upper hand on the battlefield. Leading an army across the Rubicon River, Caesar declared himself master of Rome and ruler of an empire still aspiring to greatness. At the time of Julius Caesar, the Roman Empire was a bit like a boy who has reached six feet tall, yet he’s only fourteen or fifteen years old. He’s not yet a man. The externals of empire were there - the armies were there. The Romans governed most of the coast of the Mediterranean, with the exception of Egypt. However, they had not yet learned to bring that into a functioning organism. The past decades of internal fighting had weakened the empire. Northern tribes harried the borders. Enemies were confronting Rome in the east. And the province of Spain threatened to break free. Julius Caesar moved quickly to bolster the frontiers, and his own legacy. Caesar had no heir, so when Augustus completed a dangerous mission, Caesar adopted the teenager in his will. Karl Galinsky, Professor of Classics, University of Texas, Austin:

“Augustus realized this was a tremendous opportunity. Mind you, he had no military training, but he was the heir of the greatest political figure that was under the Roman sky at that time - and he cashed in on it.”

It was a heady opportunity for Augustus, but also a perilous challenge. For in 44 BC, foreigners were not the only threat to stability. There were enemies within Caesar’s small circle of advisors. They murdered Caesar at a meeting of the Senate. For the second time in his life, Augustus lost a father. Now, on the verge of manhood, he thrust himself into the maelstrom of Roman politics. Keith Bradley, Professor of Greek and Roman Studies, University of Victoria:

“The death of Julius Caesar was not just a turning point in Augustus’ life, it was a turning point in world history. Augustus was extremely young at this time, only in his nineteenth year. Yet when he knew that he had been made Caesar’s heir, he immediately took up the political legacy of Caesar. He entered the mainstream of Roman politics. He didn’t hesitate to try to avenge his father. That meant, of course, stepping onto the stage of politics, raising an army and immersing himself in a contest for supreme political power in Rome.”

He displayed brutality against enemy prisoners. Once, when a father and son were begging for their lives, he ordered that they should draw lots to determine which one should be executed. The father offered himself and was killed. Because of this, the son committed suicide. Augustus watched them both die. Suetonius describes the crisis as “trial by fire” and Augustus didn’t flinch from the task. He formed a strategic alliance with Marc Antony, a powerful general, who also wanted supremacy. Together they massacred their enemies in the capital. Then they pursued their rivals to the shores of Greece, where they fought and won two of the bloodiest battles in Roman history. When the carnage ended, the empire was theirs. Augustus and Antony divided the spoils of war. Augustus remained in Rome. But Antony took control of Egypt, a land not formally joined to Rome, but firmly under the empire’s command. There, he joined forces with Egypt’s queen. Ancient historians, like Cassius Dio, believed that was a fateful move. When Antony fell deeply in love with his new ally, many feared the ambitious queen was scheming to rule Rome herself. Her name was Cleopatra. Cleopatra’s brazen desire for passion and wealth was insatiable. By love, she had made herself queen of Egypt. But she failed in her goal to become queen of the Romans. Judith P. Hallett, Professor of Classics, University of Maryland, College Park:

“Cleopatra did not enjoy a good press in Rome. What really irritated people about Cleopatra was that she was a powerful woman from the east, and from a very wealthy country with a monarchic system of government. She therefore symbolized lack of moderation, lack of control, frenzied fury, everything that Rome tried not to be. Cleopatra and Antony were cast as leaders of the evil empire.” Antony’s alliance with Augustus withered. But Augustus struck first. The poet, Virgil, later cast the battle as an epic struggle of east against west. “Standing high on the stern, Augustus leads the Italians into battle. Carrying with him the bite of the Senate and the people. Opposing him, with barbarian wealth, is Antony, suited for battle. He carries with him the powers of the orient. And to the scandal of all, his Egyptian wife, their monstrous divinities raised weapons against our noble, Roman gods.” Three quarters of the Egyptian fleet was destroyed. Anthony and Cleopatra committed suicide - and the land of the pharaohs was formally annexed to the Roman Empire. Judith Hallet:

“The annexation of Egypt for Augustus was immensely important. It was the equivalent of Hitler’s troops marching through the streets of Paris. Here was a wealthy country that was going to be providing food, that was going to be providing land. But above all, it was a country of great cultural prestige, and once Rome had Egypt as part of its empire, they had truly arrived.”

A Voice:

“There is nothing that man can wish from the gods, nothing the gods can do for men which Augustus, when he returned to the city, did not do for the public, the Roman people, and the entire world. Civil wars were finished - foreign wars ended and everywhere the fury of arms was put to rest.” Upon Augustus’ return to a war torn Rome in 29 BC, the city went wild with enthusiasm. The triumphant general vowed to restore peace and security. It was a promise he would keep. The victory of Augustus launched a period of stunning cultural vitality, of religious renewal and of economic well being that spread throughout the empire. It would be called the ‘Pax Romana’ - the peace of Rome. To many, it marked the return of Rome’s mythic and glorious past. But Augustus himself would never return to the past. He was now a hardened thirty-two-year-old man - the sole ruler of the Greco-Roman world, Rome’s first emperor. Victory had been costly, but the greatest challenge still lay ahead, for to avoid the fate of Julius Caesar, Augustus must disarm the Senate and charm the masses. He must do better than win the war. He must win the peace. That challenge would occupy the rest of his life. A Voice:

“Let me step forward, clear my throat, and announce that I am a native of Soula, a few days’ journey eastward from Rome.” While Augustus fought his way to the pinnacle of power, a boy named Ovid was coming of age under less demanding circumstances. Ovid Speaks:

“I was the second son, a year to the day younger than my brother. We always had two cakes on the birthday we shared, and were close in other ways as well. We studied together, and then went up to Rome to seek our fortunes. I used to waste my time trying to write verses. My father called it waste. He disapproved of any pursuit where you could not turn a decent living, and always used to say, ‘Homer died poor.’” Ovid came from the same stock as Augustus. They were both landed gentries, and like Augustus, the young man found his identity and his ambitions moulded by his demanding family.

Ovid:

“I tried to give up poetry, to stick to prose on serious subjects, but frivolous minds like mine attract frivolous inspirations, some too good not to fool with. I kept returning to my bad habits, secretive and ashamed. I couldn’t help it, I felt like an impostor in serious matters, but I owed it to my father and my brother to try to do my duty.” By Roman law, a father wielded absolute control over his children. Those who displeased him could be disowned, sold into slavery or even killed. The young Ovid tried to meet his father’s expectations. He married, studied law - but the strain proved unendurable. Miserable, Ovid and a friend set out on a journey of self-discovery. Ovid:

“We toured the magnificent cities of Asia. We watched the flames of Mount Etna light up the heavens. We ploughed the waves in a painted ship, and also travelled by wagon. Often the roads seemed short, as we were lost in conversation. When we walked, our words outnumbered our steps - and we had too much to say, even for the long evenings of supper.” Eighteen months later, Ovid settled in Rome, older and more self-confident than before. He resolved to become a poet. He cultivated new friends in Roman literary circles, and soon, Ovid made a name for himself as Rome’s reigning poet - of stolen kisses. Ovid:

“So your husband is coming to this dinner party? I hope he gags on his food. Listen - and learn what you must do. When he settles on his couch to eat, go to him with a straight face. Look modest and lie back beside him. But secretly touch me with your foot. Don’t let him drape his arms around your neck, don’t rest your gentle head against his chest - don’t welcome his fingers to your lap or to your eager nipples. Most of all, no kissing. When dinner is done, your husband will close the bedroom door. But whatever the night shall bring, tell me tomorrow - you refused.”

Keith Bradley:

“It’s a mistake to think that Ovid’s poetry can be read very literally in purely autobiographical terms. That wouldn’t be true, I think, of any poetry from antiquity. But at the same time, Ovid is writing of subjects of which he has some sort of experience and he certainly, through the love poetry, opens up a world that is very different in tone and quality from the official atmosphere.”

While Ovid bloomed as a man of words, the new emperor thrived as a man of action. He rebuilt Rome - and his own family. Divorcing his wife, Augustus married his heavily pregnant mistress - Livia. The move raised eyebrows and hackles, as love was not the only motive. Although Augustus shunned the trappings of absolute power, many suspected he was building a dynasty - a line of heirs to rule Rome for generations to come. Augustus knew it was a dangerous move. He knew that Julius Caesar had been murdered for appearing as a king. Augustus would not make the same mistake. He relinquished high office and struck a delicate balance between fact and fiction.

Augustus writes:

“Having, by universal consent, acquired control of all affairs, I transferred government to the Senate and the people of Rome.” Judith Hallet:

“Augustus was a very cagey political leader because he pretended to be restoring all of these republican political traditions. In fact, what he was running was a full-fledged dynastic monarchy.” A Voice:

“Augustus conquered Cantabria, Aquitania, Pannonia, Dalmatia and all of Illyricum, as well as Raetia.” Augustus not only changed the empire, he expanded it. Egypt had been added early in his career. Soon, Northern Spain was joined. Augustus drove across Europe, into Germany, and he united east and west by adding modern Hungary, Austria, the Balkans and central Turkey. These victories employed Roman soldiers and senators and offered welcome distractions to the city’s poor. When Augustus wasn’t staging chariot races or gladiator shows, he displayed exotic animals, the quarry of Rome’s far-flung empire. A rhinoceros appeared in the arena, Asian tigers in the theatre and a giant serpent in the forum.

Karl Galinsky:

“One key constituency for Augustus was the plebeian population of Rome, and that is basically the city mob. You have several hundred thousand folks here who have no jobs, and to put it very simply, who need to be kept off the streets, and kept from making trouble, because it’s a very volatile, combustible mixture.” The volatile mix that made up Rome stayed quiet for the first four years of Augustus’ rule. Then, in 23 BC, events took a critical turn. Cassius Dio writes that a series of disasters convinced the people that Augustus needed not less power, but more. “The city was flooded by the over flowing river and many things were struck by lightning. Then a plague passed through Italy and no one could work the land. The Romans thought these misfortunes were caused because Augustus had relinquished his office. They wished to appoint him dictator. A mob barricaded the Senate inside its building and threatening to burn them alive, forced the Senate to vote Augustus absolute ruler.” The demands threatened to unsettle the emperor’s precarious political balance. Augustus fell to his knees before the riders. He tore his toga and beat his chest. He promised the mob that he would personally take control of the grain supply. But Augustus refused to be called a dictator. The crowd disbanded, but the lesson was clear. Augustus was riding a tiger. To keep order on the frontiers, the streets and the Senate was a super human task. Super human skills were needed. Luckily for Rome, Augustus had them. Karl Galinsky:

“Then something very fortuitous happens: Halley’s Comet shows up and the word is given out by Augustus that this is the soul of Julius Caesar ascending into heaven. So from this point on he is called Julius Caesar the divine. Politically it became very potent, because what does Augustus do at this point? On all his coinage on all his writings, on all his symbols, whatever, he puts on the words “DF”, meaning Son of the Divine. And it’s really quite an asset in politics to be the Son of the Divine. There are modern politicians I think would be very jealous of being able to do that.”

Augustus enhanced his pious new identity with stories of his lean habits. It was said that he slept in a modest house, and slept on a low bed, that he ate common foods, coarse bread, common cheese, and sometimes, even less.

Augustus:

“My dear Tiberius, not even a Jew observes a fast as diligently on the Sabbath as I have today. I ate nothing until the early hours of evening when I nibbled two bites before my rub down.”

Moral change, Augustus began to argue, was the enemy of Rome. He believed that its future ran through its past, through the restoration of the values he thought had first made Rome great. Augustus:

“I renewed many traditions which were fading in our age. I restored eighty-two temples of the gods, neglecting none that required repair at the time.” In public, Augustus led by example. He sacrificed animals in traditional rituals and he re-established traditional social rules. New laws assigned theatre seats by social rank. Women were confined to the back rows. Adultery was outlawed; marriage and children were encouraged. To many, Roman society had recovered its true course. The son of a god was building an empire for the ages. Augustus:

“Who can find words to adequately describe the advancements of these years? Authority has been returned to the government, majesty to the Senate, and influence to the courts. Protests in the theatre have been stopped, integrity is honored, depravity is punished.” But amid the applause, there were also cries of protest. The emperor’s new traditional values rankled friends and enemies alike. It even rankled his own daughter, Julia. Long a pawn of family politics, Julia assumed that she was exempt from her father’s stringent views. She was wrong. And in the coming years, Augustus, son of a god, would have to confront Augustus the father.

“If there is anyone here who is a novice in the art of love, let him read my book. With study, he will love like a professional.” As the emperor, Augustus firmly charted a course of moral rigor. The poet Ovid staked out different ground. He was now Rome’s most famous living poet, and his boldness grew in step with his reputation. Having all but exhausted the conventions of love poetry, he decided to stretch them. He began composing a manual of practical tips on adultery.

Ovid writes:

“Step one - stroll under a shady colonnade. Don’t miss the shrine of Adonis, but the theatre is your best hunting ground. There you will find women to satisfy any desire, just as ants come and go, so the cultured ladies swarm to the games. They come for the show - and to make a show of themselves. There are so many I often reel from the choice.” Many Romans yearned to follow their emperor back to the good old days of stern Roman virtue. But others reveled in the promises of Rome’s newfound peace. Ovid was one of them. To the youthful poet, old limits seemed meaningless. “Do not doubt you can have any girl you wish. Some give in, others resist but all love to be propositioned. And even if you fail, rejection doesn’t hurt. Why should you fail? Women always welcome pleasure and find novelty exciting.” Indeed, the earlier civil wars had unleashed enormous social change. Some women had gained political clout, new rights, and new freedoms. Tradition holds that one such woman was Julia, the emperor’s only child.

“Julia had a love of letters and was well educated - a given in that family. She also had a gentle nature and no cruel intentions. Together these brought her great esteem as a woman.”

Julia didn’t reject traditional values wholesale. She had long endured her father’s overbearing control. She dutifully married three times to further his dynastic ambitions, and she bore five children. Her two boys, Guyus and Luccius were cherished by Augustus as probable heirs. But like Ovid, Julia expected more from the peace. She was clever and vivacious, and she had an irreverent tongue that cut across the grain of Roman convention. Her legendary wit was passed through the centuries by a late Roman writer called Macrobius.

Macrobius writes:

“Several times her father ordered her in a manner both doting and scolding to moderate her lavish clothes and keep less mischievous company. Once he saw her in a revealing dress. He disapproved but held his tongue. The next day, in a different dress, she embraced her father with modesty. He could not contain his joy and said, ‘Now isn’t this dress more suited to the daughter of Augustus?’ Julia retorted, ‘Today I am dressed for my father’s eyes. Yesterday I dressed for my husband.’

But apparently Julia’s charms were not reserved for her husband alone. The emperor’s daughter took many lovers.

Judith Hallet:

“Her dalliances were so well known that people were actually surprised when her children resembled her second husband, who was the father of her five children. She wittily replied, “Well that’s because I never take on a passenger unless I already have a full cargo.” The meaning here is that she waited until she was already pregnant before undertaking these dalliances, so concerned was she to protect the bloodlines of these offspring.“

Julia, like Ovid, was a testament to her times. But neither of them were average Romans. The life they represented shocked traditional society to the core. And as Julia entered her thirty-eighth year, crisis loom

"In that year, a scandal broke out in the emperor’s own home. It was shameful to discuss, horrible to remember

One Roman soldier voiced deep revulsion at Julia’s extraordinary self-indulgence. "Julia, ignoring her father Augustus, did everything which is shameful for a woman to do, whether through extravagance or lust. She counted her sins as though counting her blessings, and asserted her freedom to ignore the laws of decency.” Julia’s behavior erupted into a full-blown political crisis, which was marked by over-blown claims. The emperor’s daughter was rumored to hold nightly revels in Rome’s public square. She was said to barter sexual favors from the podium where her father addressed the people. When the gossip reached Augustus, the emperor flew into a violent rage. He refused to see visitors. Upon emerging, Suetonius reports, he publicly denounced his only child. “He wrote a letter, advising the Senate of her misbehavior, but was absent when it was read. He secluded himself out of shame, and even considered a death sentence for his daughter. He grew more obstinate, when the Roman people came to him several times, begging for her sake. He cursed the crowd that they should have such daughters and such wives.” As a father, Augustus could not abide Julia’s behavior. As an emperor, he could not tolerate the embarrassment. Augustus banished Julia for the rest of her life. “I was going to pass over the ways a clever girl might elude a husband or a watchful guard. But since you need help - here is my advice.” Soon after Julia’s exile, Ovid released his salacious poem. It couldn’t have been more poorly timed. “Of course a guard stands in your way, but you can still write. Compose love letters while alone in the bathroom and send them out with an accomplice. She can hide them next to her warm flesh, under her breasts or bound beneath her foot. Should your guard get wind of these schemes, she can offer her skin for paper and carry out notes written on her body.” Ovid’s poetry extolled behavior for which the emperor’s daughter was banished. Her fate loomed large as a warning. For the present, the emperor remained mute towards Rome’s most gifted rebel. Ovid turned his hand to less provocative forms of poetry. He remarried, and he embraced a new appreciation for discretion.

“Enjoy forbidden pleasures in their place. But when you dress, don’t forget your mask of decorum. An innocent face hides more than a lying tongue.” Ovid was on notice. The order of Augustus had firm bounds of propriety and Ovid had tested them to the fullest. “Now consider the dangers of night. Tiles fall from the rooftop and crack you on the head. And the drunken hooligan, spoiling for a fight, cannot rest without a brawl. What can you do when a raving madman confronts you? Or tenants throw their broken pots out the window? You’re courting disaster if you go to dinner before writing your will.” At the turn of the first century, the poet Juvenal, was writing verses, which exposed much of Rome to scorn. He was acerbic and had a keen eye for the gritty realities of urban life. Juvenal writes:

“Our apartment block is a tottering ruin. The building manager props it up with slender poles and plasters over the gaping cracks. Then he bids us sleep safe and sound in his wretched death trap.” Ronald Mellor, Professor of History, UCLA:

I don’t think our notion of Rome bears much relation to the Rome of every day life. Because what is left today are the big public buildings, not the squalid hovels without plumbing and sanitary conditions that ordinary people lived in. That’s precisely the reason members of the elite preferred to withdraw up into the hills, and to have their villas up on the hills, a little bit away from the noise and away from the stench and away from that incredible hoard of people pressing close together. Juvenal writes:

“I would love to live where there are no fears, in the dark of night. Even now, I smell fire and hear a neighbor cry out for water as he struggles to save his measly belongings. Smoke pours out from the third story as flames move upwards, but the poor wretch who lives at the top with the leaking roof and roosting birds, is oblivious to the danger, and sure to burn.” In the year 4, in the imperial palace, the emperor, Augustus also lost sleep, but not from fear of fire. Now an old man of sixty-six, Augustus has lost much of his youthful vigor. “His vision had faded in his left eye, his teeth were few, widely spaced and worn down, his hair wispy and yellowed. His skin was irritated by scratching and vehement scraping, so that he had chronic rough spots, resembling ring worm.” As the emperor neared death, plots to succeed him sprouted. His grandsons and intended heirs had both died, unexpectedly. And the emperor himself lived under constant threat of assassination. Speaking for Augustus, one ancient historian voiced his dilemma: “Whereas solitude is dreadful,” he wrote, “company is also dreadful - the very men who protect us are most terrifying.” Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Director, British School, Rome:

“In many ways, Augustus looked so solid, and what he created looked so solid you forget the fragility. I think contemporaries were very aware of that fragility. And surely Augustus was, he was - over anxious, in a sense, to provide a secure system after he’d gone.”

At this time, there were unusually strong earthquakes. The Tiber pulled down the bridge and flooded the city for seven days. There was a partial eclipse of the sun, and famine developed. Ancient historians report that natural disasters predicted political ones. In the year 6, soldiers, the backbone of the empire, refused to re-enlist without a pay rise. New funds had to be found. Then, fire swept parts of the capital. A reluctant Augustus turned to taxation. It was a dangerous tactic, and the emperor knew it. Fearing a coup, Augustus dispersed potential enemies. He recessed the courts and disbanded the Senate. He even dismissed his own retinue - Rome remained on edge.