#brevibacterium linens

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Foot cheese

Ah yes, Limburger cheese!

Did you know that Limburger is a cheese that originated in the Herve area of the historical Duchy of Limburg. The cheese is especially known for its strong smell caused by the bacterium Brevibacterium linens, which makes it smell like feet to most people!

#blogsprinkles#in character#splendorman#creepypasta#creepypasta blog#creepypasta characters#creepypasta fandom#grey sprinkles#fun facts with me#limburger cheese

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cheese is often known for being yellow, but the buttery delight can sometimes surprise us by its eye-catching violet hue. The phenomenon occurs when the cheese contains certain bacteria that can produce a blue-violet color: Brevibacterium linens and Staphylococcus carnosus. Numerous studies have been conducted to better understand the color change in cheese.

The growing conditions of cheese present a favorable atmosphere for Brevibacterium linens, as salty and humid environments allow it to thrive. While not all cheeses contain B. linens, some traditional cheeses do, such as Dutch Maasdam, French Vacherin Mont d'Or, Swiss Gruyère, and Italian Bel Paese. When B. linens is present, it can use the amino acids found in the cheese, such as tyrosine, to produce a blue-violet pigment. The microorganism Staphylococcus carnosus has similar effects.

In addition, so-called "smear-ripened" cheeses are ripe with B. linens to form an edible rind, a practice that dates back hundreds of years. Curing the cheese in salt forms a layer of salty brine around the cheese, which gives it a characteristic color that ranges from bright to deep violet.

Lastly, cheese makers can introduce B. linens to the cheese in order to change the colour, as is done with smear-ripened cheeses. The bacteria are applied to the surface of the cheese with a special brush, which deposits the bacteria that leads to the quick ripening process.

All in all, cheese can be a vibrant violet due to certain special bacteria. These amazing microorganisms are at work to make our cheese even more interesting and delicious.

0 notes

Text

I’ll Handle This (13)

In Which There’s Cheese

Ao3 | FF.net

Trigger or Squick warning: Man has done some messed up stuff in the pursuit of perfect cheese. And what is cheese but moldy, rotten milk? This chapter contains some very foul and nasty descriptions of actual cheese that people eat. So if eating rotting food makes you uncomfortable, best skip to the end of this chapter.

(Spoiler: Plagg gives Lila really gross cheese. She eats it, and has to run out of the room to vomit.)

--

“—so the best way to level up is to get a skill up to 100, and then legendary it back down to 15, so then you can use the skill perks on another ability that’s harder to level up. That’s where I’m at right now. I’m on level 106 and trying to fill up all my skill trees by using smithing, speech, enchanting, lock picking, and blocking.”

Day three of Lila’s torment, and there was presumably no end in sight.

Had she known from the beginning that Adrien Agreste was this big of a nerd and completely socially inept, she wouldn’t have talked to him at all.

Funny how people looked less attractive the more annoying they got.

And she had tried. She had sincerely tried to get him to shut up. She told him, “I’m sorry Adrien, I’m just not that interested in this video game.”

“Well, you’ve just never played it before! You should come over this weekend—no, actually, I think we should go to your place. When you aren’t grounded anymore. Your mom seemed to really like me!”

Of course she did. Her mother likes anyone who’s a ‘good influence’ on her precious baby. And nothing like Paris’ golden boy to fill that bubble.

Her mom probably preferred that Adrien was so naïve and oblivious.

The bell rang for lunch, and Lila was up and out of her seat without another word. She was tired of the games. Skyrim, Magic: The Gathering, and trying to salvage a friendship with the dumb blond. But Adrien usually ate lunch at home or with Marinette, at least he had been, so lunch was her time to recharge! She’d take her place in the throne room that was the cafeteria and have everyone’s attention. With an hour of that, she could certainly put up with whatever Adrien had to tell her the next half of the day.

In the cafeteria, most seats were taken. The two open seats were at a table with Alya, Nino, and Marinette. Of course Lila wasn’t thrilled with Marinette, but she’d leave eventually, and someone else would hear her tales and come to sit with them.

“Hey guys! Do you mind if I sit with you?” Lila smiled, all friendly-like.

“Not at all, Lila, take a seat!” Alya welcomed.

Marinette and Nino kept their poker faces as she sat down.

“So Alya, I had this amazing idea for an article for the Ladyblog, and I bet I could get some quotes from Ladybug for it too.”

“Or really?” Alya squealed. “That would be amazing! So what’s the idea?”

“Basically—“

“WHO WANTS SOME CHEESE?!” Plagg sang as he took his spot in the last remaining seat, right next to Lila.

She wanted to die.

“Cheese?” Said Nino, intrigued.

“Yeah! I have been dying to give you guys a cheese tasting, and wouldn’t you know it? All my best buds are all together! So it’s perfect!”

Lila cautiously relaxed. Cheese tastings were just as fancy as wine tastings. Maybe this would be a break and a peek into Adrien’s refinement. She could handle this.

“Okay, so for you three,” Plagg gestured to Nino, Alya, and Marinette, “I have some more...beginner cheeses. They’re still extremely tasty, but more mild for a less refined palette.”

“You calling me unrefined?” Nino glared.

“I see what you eat. And yes.”

“Touché.”

“And for you, Lila, you mentioned that two weeks ago, you had dinner with Wolfgang Puck himself. I assumed you could handle more advanced cheeses.”

Advanced cheeses? “Oh, well, yes of course. I’ve done a few cheese tastings before. Maybe not with the same quality of cheeses as you have...”

“Then this will be a walk in the park.” He unzipped the lunchbox he had brought with him, and handed out three orange cubes to the ‘beginners’. “Alright, so first, we have a whiskey cheddar. Whiskey is fermented in oak barrels that can only be used once. So they’re sold to beer, coffee, and cheese makers. The cheese is stored in the barrels and the remnants of the whiskey seep in and give it almost a spicy flavor.”

They all took a bite, chewing thoughtfully, humming in content.

“Oh wow, I think I can taste the whiskey! That’s really good!”

“I’d put this on crackers and eat a whole box! This is really good!”

“I’m not a huge fan of cheddar,” stated Marinette, “but maybe I just haven’t been trying the right stuff, because this is awesome!”

“I’m glad you like it!” Plagg beamed. “And for Lila,” he opened a container and a smell emanated immediately. It smelled like rotten armpit. “This is finely aged Limburger, aged to three months. It’s imperative that you take in the scent of the cheese first, before eating it. Don’t waft it, just breathe it in.”

Lila took the offered container, sparing it a withering glance before she inhaled.

If her face could have melted off, it would have.

“It…smells like rotten feet.”

“Ah yes, Brevibacterium linens. This is a smear-washed cheese that gets a fresh coating of bacteria that prevents mold and helps the maturing process. As a food connoisseur, you’re getting the peak time of maturity. I usually let it mature longer than this still, so it gets really runny, like camembert~…” At the very name, Plagg moaned in a way that was inappropriate for young ears. He cleared his throat. “Sorry, I got swept away in the moment. Oh right! Limburger, you eat it with your nose. Take another whiff!”

“I’m good.”

“Another whiff I say!”

Lila inhaled, and her whole body shuddered.

“Perfect. Now you can eat it.”

She popped the sample in her mouth, and swallowed quickly, shuddering the whole time.

“Good?”

“Hmm mmm…”

“Oh! I forgot to mention, the bacteria that that cheese is smeared with is the same that grows on your feet, that’s what makes the cheese stink!”

Lila made a face of disgust and turned a little green.

“Great! Round two!” He placed little samples in front of the other three first. “Okay, so this is a little more advanced. This is scamorza, which is much like Mozzarella, but it has a distinct smokey flavor. I think it tastes kind of like wood fired pizza.”

“It does!” Nino cried, savoring each little nibble. “Oh my god this is so good!”

Alya took a bit of tomato out of her sandwich and ate that with the cheese. “Oh, that is just like wood fired pizza. I’d love to try this warm! You have to get more of this!”

Plagg grinned. “And you, Marinette?”

Marinette was still chewing, and just nodded with closed eyes and a contented sigh.

“Awesome! I personally think scamorza is too mild, but it’s still very good. So for Lila I have another advanced taste.” He took out another sealed container and popped the lid. The smell wasn’t as brutal as the Limburger, but it was still potent. “This is Casu Marzu, a Sardinian delicacy. So it should sound familiar to you, since you’re from Italy and all. It’s made from sheep’s milk. Oh! And it’s illegal, so this sample is from a ‘friend’ who will not be named.”

Lila held the container a little away from her face and peered at it with hesitation. Her lip curled up in disgust, before she gave Plagg an apologetic smile. “I’m sorry, Adrien. It looks like this cheese has gone bad.” And she pushed the container back towards him.

He looked in it. “It looks fine to me. They’re alive. That’s a good thing.”

“Adrien, those are maggots.”

“Cheese fly maggots, to be exact,” he corrected. “They’re introduced to the cheese to help break down the fat in the milk.” He pushed the container back in front of her. “I mean, it’s not any more gross than escargot, or caviar, or grasshopper, or tequila worms, you know?”

She looked back at the worms, her lip trembling. “This is a delicacy?”

“Of course! I wouldn’t bring bad cheese in for a laugh.” He took out a spoon and scooped out a little cheese, worms and all, and spread it on a piece of flatbread. Then he ate it. “Ohhh that’s good!”

“I…” She cast one more look at the container and confessed, “I’m sorry Adrien. I just can’t do it. It’s too gross for me.”

“Oh,” said Plagg, with genuine sadness in his voice. “Okay I guess...anyone else want to try?”

Marinette, who was always looking for a chance to show up Lila, offered up, “I’ll give it a try.”

Plagg’s eyes widened with glee. “You will?!”

“Sure. Even if it’s gross, I can say I tried it. Not everyday you get to eat illegal cheese. And you ate some, afterall.”

“Yes! I promise it’ll be worth it! You just have to thoroughly chew it to kill the maggots.”

Marinette scrunched up her nose. “Can I...kind of eat around the worms?”

“You can try.”

So to Marinette’s credit, she did eat some of the cheese, though it was picked through, and she scraped what she could off with a knife. Then she spread a little on a larger piece of bread, more bread than cheese obviously, then chewed her sample thoroughly.

“Well?” Asked Plagg, bouncing in his seat. “I think it’s kind of like Camembert and Gorgonzola had a baby. A rotten, decaying baby.”

“Mmm hmmm.” Marinette nodded, her lips shut tight. Once she swallowed, she downed a huge swig of her water, swishing around in her mouth first.

“That bad, huh?” Asked Alya.

“No no, it actually tasted really really good. And I couldn’t feel the worms or anything. I just couldn’t get over the idea that they were there. You know?”

“It’s scary!” Plagg assured. “I know it freaked me out when I was a kid, but if it wasn’t worth it, they wouldn’t make it!”

“You’re wicked brave, Marinette.” Nino patted her on the back.

She chuckled. “Alright. Do you have any more samples so I can cleanse my palette?”

“Oh yep! Last round!” He set out three more samples. “So this is Cantal. It’s from Cantal, France, obviously. And it’s often thought of as a dessert cheese, as it’s got a sort of spicy sweet taste, or like hazelnuts. Oh, and you’ll want to eat it with these apple slices. This is a young wheel, only two months old.”

Contented hums filled the air as the three munched on the sweet, buttery, fruity delight.

Plagg felt extremely pleased that he convinced Adrien’s friends to eat cheese. And he was especially proud of Marinette for eating the best, most amazing cheese of all time. If casu marzu wasn’t an absolute pain to get ahold of, and if it were more portable, he’d demand Adrien to get him that instead of Camembert.

But, as it was, they had to go with more convenient cheeses.

“I think I’m all cheesed out...” said Lila.

“Dude, you only actually had one sample. You can’t bow out now!”

At this point, especially after the maggots, a small crowd had assembled around the table to observe the tasting. And if anyone would cave under peer pressure, it was Lila.

“Well, I suppose I could try one more...”

“Perfect! Because this last sample is really special!” He placed the little white flecked square in front of her. “This is my take on pepper jack cheese.”

“Wait, you made this?” She asked.

“Yep! I figured that if I love eating cheese so much, I should make my own!”

“So what’s it made of?” Lila asked, hesitant.

“You have to guess! I want to see if you can guess the milk and the pepper. It’s part cow milk, obviously, but I wanted a different flavor that you don’t get with most semi hard cheeses.”

“And there’s no bugs in it?”

Plagg laughed. “Nope, no bugs!”

Feeling a bit better, Lila brought the sample up to her mouth. The smell was subtle, a little spicy, a little milky. Not at all like the last two.

She bit the sample in half, and chewed thoughtfully. “It’s...kind of sweet...but the spice is...” she blinked a few times, her face turning red and eyes watering. “It’s hot. It’s really hot!” She ate the other half, and then regretted it. “Ugh! I shouldn’t have done that!” She swallowed and downed her little carton of milk, but the heat wouldn’t leave. It kept getting worse and worse!

“What did you put in there?! What was that?!”

Plagg looked confused. “It’s really that spicy?”

“My mouth hurts!! It hurts to talk!”

“All it is is Carolina Reaper and Breast Milk.”

Lila was up and out like a bolt, running to the bathroom to hurl.

Marinette likewise, had to leave the room, as her uproarious laughing at Lila’s suffering would have looked really bad.

—

(If you were looking for the cheese free section of the chapter, this is it!)

Lila didn’t return to class immediately. In fact, it was two periods later when she finally returned. Her face was flushed and her eyes bloodshot, and she had a wet spot on her shirt. Before everyone settled in, she claimed Adrien’s old seat, right up front.

“Sorry,” she croaked, her voice hoarse after retching so much. “Vomiting usually exacerbates my tinnitus. I hope you don’t mind if I sit up front, Adrien.”

Nino answered, “oh dude, you can have my spot. That way you and Adrien can still sit together!”

Lila’s eyes widened slightly in horror, but before she could protest, Alya slid into the spare seat. She was unfortunately not in on the plan, and was picking up all the blatant body language Plagg was ignoring. “I think Lila needs a little girl time, after her rough lunchtime experience.”

Marinette silently scooted over into Alya’s spot, so that Plagg could sit right behind Lila. It wasn’t ideal, but it would work. Nino gave them both a silent thumbs up and took the open spot in the back of the room.

Lila let out a sigh of relief.

“You okay, girl?” Alya asked.

“Yeah.” She said shortly. Lila was done with the day. She would have gone home if she thought her mom would believe the cheese story, but as it was, she was already in hot water. She just needed to make it through the last two periods, and she’d be okay. Maybe she could convince her mom that she was sick and stay home tomorrow? I would be worth a try. She just needed some time away from Adrien. He was much too much.

As if reading her mind, Plagg leaned forward in his seat and spoke softly to her. “So I wanted to tell you about Stalhrim. It’s a material they added in the DLC, and you can learn how to craft with it, but it’s triggered by a quest. The first time I played the game, the person who was supposed to give the quest was killed by a lurker. Hold on, let me backup, so there are these huge monoliths call Standing Stones, and they all give you special abilities, like the Steed Stone let’s you carry things and the Apprentice Stone lets you learn magic quicker—“

As he talked, Lila’s fingers curled into the surface of the desk. His words didn’t even make any sense anymore, it was just this droning sound that wouldn’t stop.

“So in the DLC, the stones are totally different, right? And there’s this bad dude named Miraack and he’s also a Dragonborn. You remember what a Dragonborn is, right? Except this one is bad and he’s brainwashing the people on the island of Solstheim. Oh right, the whole DLC takes place on a separate island—“

The whole two weeks had been a camel. And each little rant or pushed boundary Adrien forced was another piece of straw piling up. Just then, it was like that fragile spine snapped, and something in Lila went from ��playing the long game’ to ‘MURDER’.

“SHUT UP!” Lila screamed, pounding her fists on the table. “OH MY GOD JUST SHUT THE HELL UP!” She stood and whirled around to glare at him. “Adrien, you are the single most obnoxious person I have ever met! You just don’t know when to shut up! Are you dense? Are you retarded? How can you not see that I literally cannot give a flying eff about anything you say?! I was trying to be your friend because I thought it would be an easy way to fame. Then I felt sorry for you because of how awkward you are. Now? It’s not worth it. It’s not worth pretending to think you’re interesting when you aren’t. It’s not worth trying to ease back and deal with everyone wondering what happened. Everyone in class would wonder why we weren’t talking anymore, and I’d have to come up with more lies to get away from you, and I just don’t want to deal with that! You’re not worth it, okay? You are so selfish and annoying! Is this why your dad kept you home schooled all your life? Because he needs to lock you right back up! You are a menace!” She swung back around for a moment to gather her belongings. “I can’t even be in the same room as you anymore. I’m so done with you and your stupid rants about stupid video games! And what kind of weirdo is that obsessed with cheese?! You ate maggots for Christ sake! You’re disgusting! If you weren’t attractive, I bet your father would have regretted having you, if he hasn’t already!” She moved to the door quickly. “I’m asking to change classes, effective immediately. I suggest everyone run while you still can!” Then she caught Marinette’s eye. “Listen, I dislike you almost as much as him, but you don’t want him, Marinette. He’s an absolute freak. Look at him! He’s wearing that stupid ramen themed sweat suit! You know what? Forget it! I’m out!” And she left, slamming the door behind her.

No one had the nerve to speak after she left. It was just too big of a can of worms, no one wanted to open it.

The silence was broken by a high pitched whine, followed by a sob.

Though Marinette knew it was Plagg faking it, the sight of tears on Adrien’s face made her heart hurt.

“Oh Adrien...”

“You still like me, right Marinette?” He blubbered.

She hugged him. “Of course, Adrien. I love you.”

That seemed to be the words to break the spell and the classmates descended on him like vultures.

“You’re not annoying, Adrien!” Someone protested.

“You’re the coolest!”

“I love talking video games with you!”

“That cheese testing was really fun!”

“Who cares if you struggle with social cues? We all do! You do better than most, even for being homeschooled!”

“Lila admitted she was in the friendship for fame, her opinion doesn’t matter!”

Marinette whispered in his ear. “Nicely done, but I was not expecting that blow up.”

“Thanks, I was hoping she’d crack soon. That was just as violent as I had expected of her.”

“You okay? Those look like genuine tears.”

Plagg wiped his face as the rest of the class started to back off. “I’m okay,” he whispered. “Just hurts to hear someone be so cruel to my kitten.”

He glanced at the ring, hoping to see the final pad gone, and the one minute wait to switch back initiated.

But alas, no. The third pad was still there.

Lila wasn’t finished yet.

#miraculous ladybug#I'll handle this#fanfiction#adrien and plagg#plagg#adrien agreste#adrienette#ml#chat noir

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

tengo una relación muy tóxica con el roquefort porque odio el olor a culo que tiene pero me encanta el sabor 😔

Bueno eso es porque en efecto, las bacterias del roquefort (Penicillium roqueforti) producen casi los mismos compuestos que los del "mal olor corporal" digamos. Y hay quesos hechos con Brevibacterium linens que es literalmente la bacteria presente en la piel humana que genera el olor a pata.

Por eso es que los mosquitos se sienten atraídos a ciertas variedades de quesos, ya que sienten el mismo aroma que los atrae a nosotros.

Espero que este dato sea de utilidad!

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Apparently the bacteria (Brevibacterium linens) that makes the cheese is also the same one that causes foot odor o_0

15 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Curiosity Daily Podcast: Why Feet Stink, How NASA Knows Where to Dig for Life On Mars, and Why Ice Is Luxurious

Learn about why feet smell bad; how NASA knows where to dig on its next mission to find evidence of life on Mars; and why you associate cold temperatures with luxury.

In this podcast, Cody Gough and Ashley Hamer discuss the following stories from Curiosity.com to help you get smarter and learn something new in just a few minutes:

To Find Evidence of Life on Mars, NASA's Next Mission Knows Where to Dig — https://curiosity.im/2D7ad7H

To Make Products Seem More Luxurious, Retailers Literally Put Them on Ice — https://curiosity.im/34bfas7

Additional sources:

Bacteria, Beneficial: Brevibacterium linens, Brevibacterium aurantiacum and Other Smear Microorganisms | Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences, 2011 — https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780081005965006326?via%3Dihub

How to Get Rid of Foot Odor | HowStuffWorks — https://health.howstuffworks.com/wellness/men/sweating-odor/how-to-get-rid-of-foot-odor1.htm

Curious Kids: Why do feet stink by the end of the day? | The Conversation — https://theconversation.com/curious-kids-why-do-feet-stink-by-the-end-of-the-day-125037

Download the FREE 5-star Curiosity app for Android and iOS at https://curiosity.im/podcast-app. And Amazon smart speaker users: you can listen to our podcast as part of your Amazon Alexa Flash Briefing — just click “enable” here: https://curiosity.im/podcast-flash-briefing.

via https://omny.fm/shows/curiosity-podcast/why-feet-stink-how-nasa-knows-where-to-dig-for-life-on-mars-why-ice-is-luxurious

#why feet stink#smells#smelly feet#stinky bacteria#bacteria#sweat glands#human body#physiology#NASA#Mars#Mars 2020#Mars mission#life on Mars#mission to Mars#why ice is luxurious#luxury#luxury retail#luxury products#luxury items#retail#marketing#marketing tactics#psychology#marketing psychology#eccrine#apocrine#Brevibacterium linens#carbonate#hydrated silica#Jezero crater

1 note

·

View note

Text

Science: The Science Behind Your Cheese! The Food is Not Just a Tasty Snack—It’s an Ecosystem

— Ute Eberle, Knowable Magazine | November 30, 2022 | NOVA—PBS

Fungi and bacteria play a big part in shaping the flavor and texture of cheese. BSIP / Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Some cheeses are mild and soft like mozzarella, others are salty-hard like Parmesan. And some smell pungent like Époisses, a funky orange cheese from the Burgundy region in France.

There are cheeses with fuzzy rinds such as Camembert, and ones marbled with blue veins such as Cabrales, which ripens for months in mountain caves in northern Spain.

Yet almost all of the world’s thousand-odd kinds of cheese start the same, as a white, rubbery lump of curd.

How do we get from that uniform blandness to this cornucopia? The answer revolves around microbes. Cheese teems with bacteria, yeasts and molds. “More than 100 different microbial species can easily be found in a single cheese type,” says Baltasar Mayo, a senior researcher at the Dairy Research Institute of Asturias in Spain. In other words: Cheese isn’t just a snack, it’s an ecosystem. Every slice contains billions of microbes — and they are what makes cheeses distinctive and delicious.

People have made cheese since the late Stone Age, but only recently have scientists begun to study its microbial nature and learn about the deadly skirmishes, peaceful alliances and beneficial collaborations that happen between the organisms that call cheese home.

To find out what bacteria and fungi are present in cheese and where they come from, scientists sample cheeses from all over the world and extract the DNA they contain. By matching the DNA to genes in existing databases, they can identify which organisms are present in the cheese. “The way we do that is sort of like microbial CSI, you know, when they go out to a crime scene investigation, but in this case we are looking at what microbes are there,” Ben Wolfe, a microbial ecologist at Tufts University, likes to say.

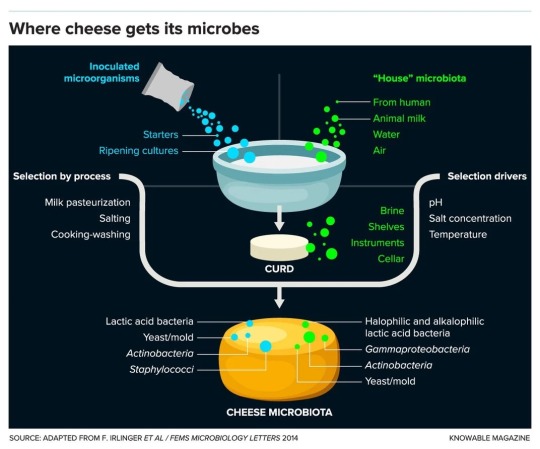

Early on, that search yielded surprises. For example, cheesemakers often add starter cultures of beneficial bacteria to freshly formed curds to help a cheese on its way. Yet when Wolfe’s group and others examined ripened cheeses, they found that the microbial mixes — microbiomes — of the cheeses showed only a passing resemblance to those cultures. Often, more than half of the bacteria present were microbial “strangers” that had not been in the starter culture. Where did they come from?

Many of these microbes turned out to be old acquaintances, but ones we usually know from places other than cheese. Take Brachybacterium, a microbe present in Gruyère, which is more commonly found in soil, seawater and chicken litter (and perhaps even an Etruscan tomb). Or bacteria of the genus Halomonas, which are usually associated with salt ponds and marine environments.

Then there’s Brevibacterium linens, a bacterium that has been identified as a central contributor to the stinkiness of Limburger. When not on cheese, it can often be found in damp areas of our skin such as between our toes. B. linens also adds characteristic notes to the odor of sweat. So when we say that dirty feet smell “cheesy,” there’s truth to it: The same organisms are involved. In fact, as Wolfe once pointed out, the bacteria and fungi on feet and cheese “look pretty much the same.” (An artist in Ireland demonstrated this some years ago by culturing cheeses with organisms plucked from people’s bodies.)

Initially, researchers were dumbfounded by how some of these microbes ended up on and in cheese. Yet, as they sampled the environment of cheesemaking facilities, a picture began to emerge. The milk of cows (or goats or sheep) contains some microbes from the get-go. But many more are picked up during the milking and cheesemaking process. Soil bacteria lurking in a stable’s straw bedding might attach themselves to the teats of a cow and end up in the milking pail, for example. Skin bacteria fall into the milk from the hand of the milker or get transferred by the knife that cuts the curd. Other microbes enter the milk from the storage tank or simply drift down off the walls of the dairy facility.

Every cheese is an ecosystem of bacteria and fungi. These microbes were isolated from the rind of a Vermont blue cheese. The orange colonies with ruffled edges are the bacterium Staphylococcus xylosus and the white ones are S. succinus. The small round colonies are several species of Brevibacterium, and the fuzzy white colony is a Penicillium mold. Courtesy of the Wolfe Lab, Tufts University

Some microorganisms are probably brought in from surprisingly far away. Wolfe and other researchers now suspect that marine microbes such as Halomonas get to the cheese via the sea salt in the brine that cheesemakers use to wash down their cheeses.

A simple, fresh white cheese like petit-suisse from Normandy might mostly contain microbes of a single species or two. But in long-ripened cheeses such as Roquefort, researchers have detected hundreds of different kinds of bacteria and fungi. In some cheeses, more than 400 different kinds have been found, says Mayo, who has investigated microbial interactions in the cheese ecosystem. Furthermore, by repeatedly testing, scientists have observed that there can be a sequence of microbial settlements whose rise and fall can rival that of empires.

Consider Bethlehem, a raw milk cheese made by Benedictine nuns in the Abbey of Regina Laudis in Connecticut. Between the day it gets made (or “born,” as cheesemakers say) to when it’s fully ripe about a month later, Bethlehem changes from a rubbery, smooth disk to one with a dusty white rind sprouting tiny fungal hair, and eventually to a darkly mottled surface. If you were to look with a strong microscope, you could watch as the initially smooth rind becomes a rugged, pocketed terrain so densely packed with organisms that they form biofilms similar to the microbial mats around bathroom drains. A single gram of rind from a fully ripened cheese might contain a good 10 billion bacteria, yeasts and other fungi.

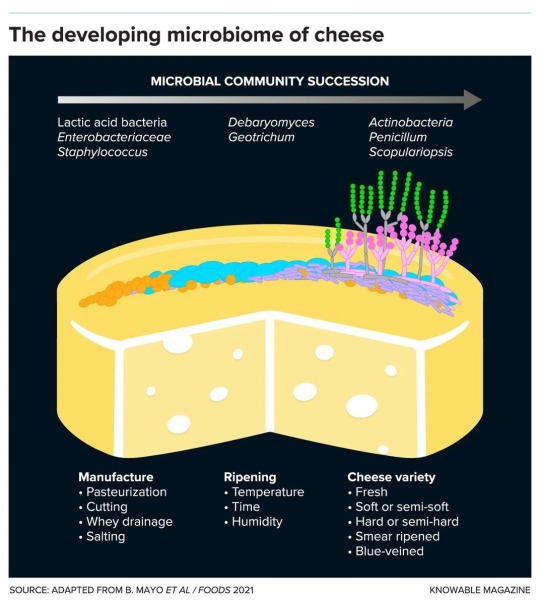

As a cheese matures, the lactic acid bacteria and other early colonists give way to other species of bacteria and, eventually, fungi, in a process known as ecological succession. The details of which species are present depend on exactly how the cheese is made and ripened, and what variety it is. Adapted from B. Mayo et al. / Foods 2021 / Knowable Magazine

But the process usually starts simply. Typically, the first microbial settlers in milk are lactic acid bacteria (LABs). These LABs feed on lactose, the sugar in the milk, and as their name implies, they produce acid from it. The increasing acidity causes the milk to sour, making it inhospitable for many other microbes. That includes potential pathogens such as Escherichia coli, says Paul Cotter, a microbiologist at the Teagasc Food Research Centre in Ireland who wrote about the microbiology of cheese and other foods in the 2022 Annual Review of Food Science and Technology.

However, a select few microorganisms can abide this acid environment, among them certain yeasts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker’s yeast). These microbes move into the souring milk and feed on the lactic acid that LABs produce. In doing so, they neutralize the acidity, eventually allowing other bacteria such as B. linens to join the cheesemaking party.

As the various species settle in, territorial struggles can ensue. A study in 2020 that looked at 55 artisanal Irish cheeses found that almost one in three cheese microbes possessed genes needed to produce “weapons” — chemical compounds that kill off rivals. At this point it isn’t clear if and how many of these genes are switched on, says Cotter, who was involved in the project. (Should these compounds be potent enough, he hopes they might one day become sources for new antibiotics.)

But cheese microbes also cooperate. For example, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts that eat the lactic acid produced by the LABs return the favor by manufacturing vitamins and other compounds that the LABs need. In a different sort of cooperation, threadlike fungal filaments can act as “roads” for surface bacteria to travel deep into the interior of a cheese, Wolfe’s team has found.

By now you might have started to suspect: Cheese is fundamentally about decomposition. Like microbes on a rotten log in the woods, the bacteria and fungi in cheese break down their environment — in this case, the milk fats and proteins. This makes cheeses creamy and gives them flavor.

The microbes that colonize cheese come from many places. Some are intentionally added to the milk, while others drift there from the environment and from the cheesemakers themselves. Details of temperature, salt, acidity and other variables determine which of the colonists survive and dominate as the cheese matures. Adapted From F. Irlinger et al. / FEMS Microbiology Letters 2014 / Knowable Magazine

Mother Noella Marcellino, a longtime Benedictine cheesemaker at the Abbey of Regina Laudis, put it this way in a 2021 interview with Slow Food: “Cheese shows us what goodness can come from decay. Humans don’t want to look at death, because it means separation and the end of a cycle. But it’s also the start of something new. Decomposition creates this wonderful aroma and taste of cheese while evoking a promise of life beyond death.”

Exactly how the microbes build flavor is still being investigated. “It’s much less understood,” says Mayo. But a few things already stand out. Lactic acid bacteria, for example, produce volatile compounds called acetoin and diacetyl that can also be found in butter and accordingly give cheeses a rich, buttery taste. A yeast called Geotrichum candidum brings forth a blend of alcohols, fatty acids and other compounds that impart the moldy yet fruity aroma characteristic of cheeses such as Brie or Camembert. Then there’s butyric acid, which smells rancid on its own but enriches the aroma of Parmesan, and volatile sulfur compounds whose cooked-cabbage smell blends into the flavor profile of many mold-ripened cheeses like Camembert. “Different strains of microbe can produce different taste components,” says Cotter.

All a cheesemaker does is set the right conditions for the “rot” of the milk. “Different bacteria and fungi thrive at different temperatures and different humidity levels, so every step along the way introduces variety and nuance,” says Julia Pringle, a microbiologist at the artisan Vermont cheesemaker Jasper Hill Farm. If a cheesemaker heats the milk to over 120 degrees Fahrenheit, for example, only heat-loving bacteria like Streptococcus thermophilus will survive — perfect for making cheeses like mozzarella.

Cutting the curd into large chunks means that it will retain a fair amount of moisture, which will lead to a softer cheese like Camembert. On the other hand, small cubes of curd drain better, resulting in a drier curd — something you want for, say, a cheddar.

Storing the young cheese at warmer or cooler temperatures will again encourage some microbes and inhibit others, as does the amount of salt that is added. So when cheesemakers wash their ripening rounds with brine, it not only imparts seasoning but also promotes colonies of salt-loving bacteria like B. linens that promptly create a specific kind of rind: “orangey, a bit sticky, and kind of funky,” says Pringle.

Even the tiniest changes in how a cheese is handled can alter its microbiome, and thus the cheese itself, cheesemakers say. Switch on the air exchanger in the ripening room by mistake so that more oxygen flows around the cheese and suddenly molds will sprout that haven’t been there before.

But surprisingly, as long as the conditions remain the same, the same communities of microbes will show up again and again, researchers have found. Put differently: The same microbes can be found almost everywhere. If a cheesemaker sticks to the recipe for a Camembert — always heats the milk to the relevant temperature, cuts the curd to the right size, ripens the cheese at the appropriate temperature and moisture level — the same species will flourish and an almost identical kind of Camembert will develop, whether it’s on a farm in Normandy, in a cheesemaker’s cave in Vermont or in a steel-clad dairy factory in Wisconsin.

Some cheesemakers had speculated that cheese was like wine, which famously has a terroir — that is, a specific taste that is tied to its geography and is rooted in the vineyard’s microclimate and soil. But apart from subtle nuances, if everything goes well in production, the same cheese type always tastes the same no matter where or when it’s made, says Mayo.

By now, some microbes have been making cheese for people for so long that they have become — in the words of microbiologist Vincent Somerville at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland — “domesticated.” Somerville studies genomic changes in cheese starter cultures used in his country. In Switzerland, cheesemakers traditionally hold back part of the whey from a batch of cheese to use again when making the next one. It’s called backslopping, “and some starter cultures have been continuously backslopped for months, years, and even centuries,” says Somerville. During that time, the backslopped microbes have lost genes that are no longer useful for them in their specialized dairy environment, such as some genes needed to metabolize carbohydrates other than lactose, the only sugar found in milk.

But not only has cheesemaking become tamer over time, it is also cleaner than it used to be — and this has had consequences for its ecosystem. These days, many cows are milked by machines and the milk is siphoned directly into the closed systems of hermetically sealed, ultra-filtered storage tanks, protected from the steady rain of microbes from hay, humans and walls that settled on the milk in more traditional times.

Often the milk is pasteurized, too — that is, briefly heated to high temperatures to kill the bacteria that come naturally with it. Then, they’re replaced with standardized starter cultures.

All of this has made cheesemaking more controlled. But alas, it also means that there’s less diversity of microbes in our cheeses. Many of our cheddars, provolones and Camemberts, once wildly proliferating microbial meadows, have become more like manicured lawns. And because every microbe contributes its own signature mix of chemical compounds to a cheese, less diversity also means less flavor — a big loss.

0 notes

Text

I decided to sample Limburger as The Cheese Of The Day because I was curious about its infamy. And it is true, it smells VERY strong. Just now I was googling it to find any interesting facts and

Once it reaches three months, the cheese produces its notorious smell because of the bacterium used to ferment Limburger cheese and many other smear-ripened cheeses.[8]This is Brevibacterium linens, the same one found on human skin that is partially responsible for body odor and particularly foot odor.[3]

guys

it literally smells like feet

#cheesy tasty tales#i don't think it smells too bad actually just super strong#the traditional german way to eat it is on rye bread with raw onion slices

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Limburger cheese is especially known for its strong smell caused by the bacterium Brevibacterium linens. Dimethyl trisulfide should be responsible for that odor. #chemistry #KingDraw #science

0 notes

Text

By now you might have started to suspect: Cheese is fundamentally about decomposition. Like microbes on a rotten log in the woods, the bacteria and fungi in cheese break down their environment — in this case, the milk fats and proteins. This makes cheeses creamy and gives them flavor.

Mother Noella Marcellino, a longtime Benedictine cheesemaker at the Abbey of Regina Laudis, put it this way in a 2021 interview with Slow Food: “Cheese shows us what goodness can come from decay. Humans don’t want to look at death, because it means separation and the end of a cycle. But it’s also the start of something new. Decomposition creates this wonderful aroma and taste of cheese while evoking a promise of life beyond death.”

Exactly how the microbes build flavor is still being investigated. “It’s much less understood,” says Mayo. But a few things already stand out. Lactic acid bacteria, for example, produce volatile compounds called acetoin and diacetyl that can also be found in butter and accordingly give cheeses a rich, buttery taste. A yeast called Geotrichum candidum brings forth a blend of alcohols, fatty acids and other compounds that impart the moldy yet fruity aroma characteristic of cheeses such as Brie or Camembert. Then there’s butyric acid, which smells rancid on its own but enriches the aroma of Parmesan, and volatile sulfur compounds whose cooked-cabbage smell blends into the flavor profile of many mold-ripened cheeses like Camembert. “Different strains of microbe can produce different taste components,” says Cotter.

All a cheesemaker does is set the right conditions for the “rot” of the milk. “Different bacteria and fungi thrive at different temperatures and different humidity levels, so every step along the way introduces variety and nuance,” says Julia Pringle, a microbiologist at the artisan Vermont cheesemaker Jasper Hill Farm. If a cheesemaker heats the milk to over 120 degrees Fahrenheit, for example, only heat-loving bacteria like Streptococcus thermophilus will survive — perfect for making cheeses like mozzarella.

Cutting the curd into large chunks means that it will retain a fair amount of moisture, which will lead to a softer cheese like Camembert. On the other hand, small cubes of curd drain better, resulting in a drier curd — something you want for, say, a cheddar.

Storing the young cheese at warmer or cooler temperatures will again encourage some microbes and inhibit others, as does the amount of salt that is added. So when cheesemakers wash their ripening rounds with brine, it not only imparts seasoning but also promotes colonies of salt-loving bacteria like B. linens that promptly create a specific kind of rind: “orangey, a bit sticky, and kind of funky,” says Pringle.

Even the tiniest changes in how a cheese is handled can alter its microbiome, and thus the cheese itself, cheesemakers say. Switch on the air exchanger in the ripening room by mistake so that more oxygen flows around the cheese and suddenly molds will sprout that haven’t been there before.

— The Science Behind Your Cheese

#ute eberle#the science behind your cheese#food and drink#science#microbiology#chemistry#genetics#bacteriology#mycology#cheese#curd#geotrichum candidum#butyric acid#streptococcus thermophilus#brevibacterium linens#brie#camembert#parmesan#mozzarella#cheddar cheese

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fromage Dauphin (France).

Spécialité des Hauts de France, et plus précisément de la Thiérache, le Dauphin est un dérivé de la fabrication du maroilles, déjà évoquée dans ce blog. En synthèse, le maroilles est un fromage à pâte molle, fabriqué exclusivement avec du lait de vache, à croûte lavée de couleur rouge-orangée (due uniquement aux ferments naturels du rouge appelés brevibacterium linens). Le lait peut être…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

036 (3) – BITÁCORA JAC – EL BRIE, EL REY DE LOS QUESOS -

Hace muchos siglos, el queso brie era uno de los tributos que los súbditos tenían que pagar a los reyes de Francia.

Lo más seguro es que el Brie de Meaux, uno de los dos tipos de queso Brie certificados por el gobierno francés, fue fabricado en la provincia de Brie, a las afueras de París, alrededor del 770.

Aparece mencionado en el Gargantúa y Pantagruel de Rabelais, pues Gargantúa regala un queso de brie a sus padres.

El brie (pronúnciese «bri») es un queso de pasta blanda elaborado con leche cruda de vaca. Se denomina así por la región geográfica francesa de la cual procede, la Brie. Su área de producción se extiende al este de París, en la región Isla de Francia.

Se elabora con leche cruda de vaca, salvo en USA y Australia donde se usa leche pasteurizada. Está cubierto con una suave capa completamente comestible, formada por el moho Penicillium candida (y a veces por otras bacterias como la Brevibacterium linens) que aparece durante el periodo de curación.

La pasta es de color pálido, marfil o amarillo claro. La textura es cremosa y el sabor delicado, aunque éste va adquiriendo un sabor más fuerte conforme madura. Se elabora en forma de rueda, pudiendo comercializarse entero o en cuñas triangulares.

Puede tomarse como aperitivo o como postre, en tabla de quesos, en sándwich, y acompañado por pan. Marida bien con vino tinto, especialmente con: Bourgueil, Brouilly, Saint-Émilion o Pinot Noir.

El término «brie» es genérico para designar este tipo de queso, que se elabora hoy en día por todo el mundo, admitiendo algunas variedades poco ortodoxas como los brie que incluyen hierbas o los que añaden doble o triple de leche.

Producción. La temperatura ideal para el modelado del queso se varía en el proceso. Inicialmente, se trabaja a 33°C, y se mantiene esa temperatura durante 4 horas, después se mantiene a 24°C durante 6 horas y finalmente se baja a 19°C. Después, el queso se escurre sobre esteras de caña.

El proceso finaliza con el salado y la maduración del queso trabajada por el maestro afinador, quien ajusta el punto de curado, volteando los quesos de forma artesanal y manteniéndolos en constante vigilancia aproximadamente durante 8 semanas hasta que están listos para el consumo.

Características y morfología del queso Brie - Se trata de un queso artesanal de pasta blanda hecho con leche cruda, y que tiene forma aplastada, corteza delgada y mohosa de color blanco, algo aterciopelada. Tiene denominación de origen protegida, desde 1980. Se elabora en forma de rueda, pudiendo comercializarse entero en piezas circulares, o en cuñas de forma triangular.

En cuanto a los aspectos visuales, la corteza, es una capa comestible, formada por el moho Penicillium candida que aparece durante el periodo de curación. La pasta del interior es de color pálido, marfil o amarillo claro. Al tacto, la textura es cremosa y a temperaturas superiores a 20º, intenta salir de la corteza. Se nota la elasticidad de la pasta. En nariz, se perciben aromas leves de amoniaco, y se adivina el sabor, en especial en piezas con más larga maduración. En boca, se detectan sabores lácticos delicados y se percibe el aroma y el sabor delicado del queso, aunque éste se percibe con más fuerza conforme madura el queso. Desprende un ligero aroma característico. [email protected]

0 notes

Text

Factoide #1300

El olor de los pies y el del queso son producidos por la misma bacteria

La mayoría de los olores corporales desagradables son causados por bacterias, incluyendo el del sudor, el mal aliento y el típico “olor a patas”. En este último caso, la responsable es la bacteria Brevibacterium linens, que consume células muertas de la piel humana, convirtiendo aminoácidos en metanotiol, el compuesto al que pertenece este aroma.

La misma bacteria también se utiliza en la elaboración de muchos tipos de quesos, como el port-salut, para la lograr la fermentación que les da su sabor único. En este caso, una levadura usa la energía del lactato para elevar la acidez del queso hacia el nivel necesario para que se desarrolle la bacteria

[Publicado originalmente el 27 de Mayo del 2015]

0 notes

Text

The Monks Who Accidentally Invented Washed-Rind ‘Stinky’ Cheese

Those who have walked into a cheese shop and thought, “It smells amazing in here! And also kind of like feet!” have smelled the glory of washed-rind cheeses. Sometimes called “stinky cheese,” these are the cheeses like Époisses, Taleggio, Munster, and Ardrahan that can smell as gentle as yeasty bread dough, or as strong as a teenage athlete’s dirty sock — or even death itself.

In fact, in the 19th century, the process of making this style of cheese was called “putrefactive fermentation” — in other words, “death-like fermentation.”

In order to create these sometimes atrocious-smelling cheeses, makers take a cheese that would have otherwise become a Brie-style cheese and gently scrub it down with a brine solution or a diluted solution of wine, beer, or another alcoholic beverage. In doing so, a new host of bacteria starts growing on the cheese, including one called Brevibacterium linens (often shortened to B. linens).

B. Linens, explains Michelle Vieira, Certified Cheese Professional, cheesemonger at Whole Foods, and creator of Instagram-based blog Columbus Curd Nerd, is “the same bacteria found in the sweaty, smelly zones on the body, which is why washed rinds often smell like dirty socks. This bacteria likes warm and wet areas.”

Especially for those of us who grew up with yellow cheddar slices that don’t smell like much at all, feety washed rinds are a real stretch. Why would anyone choose to put that in their mouth?

Well, most of these cheeses don’t taste nearly as strong as they smell, and “they often boast salty, meaty notes,” explains Vieira.

And, depending on who’s telling the story, that was either an incredible invention or a wonderful accident. According to “The Oxford Companion to Cheese,” the first washed-rind cheese on record, in the 7th century, was Munster, made by monks in Alsace-Lorraine. The name is said to come from the Latin monastarium, meaning “monastery.”

“Monastic life is ideally suited to cheesemaking,” explains “The Oxford Companion to Cheese,” “with its rigorous and repetitive daily routines.”

“The Rule of St. Benedict,” a book written in 516 to guide monks living under an abbot, proclaims, “Idleness is the enemy of the soul. The brethren, therefore must be occupied at stated hours in labor … for then are they truly monks when they live by the labor of their hands.”

Often, the monks would fast from meat, for both logistical and religious reasons.

How, though, did they discover this method of washing down cheese to bring out its funky side? One way that it may have happened (and the story that many cheesemongers tell inquisitive customers) is this:

Benedictine monks in the Middle Ages made many wonderful, often-fermented food products, including bread, cheese, wine, and beer. At some point, alcohol was put to use as an effective sanitizing solution, as was brine.

As the story goes, there was a young, pious monk on cheese duty one day who noticed a new mold growing on his cheeses. Not one to be bested by scary new molds, he grabbed his sanitizing bucket (which would have held a diluted alcohol or brine solution) and scrubbed down the moldy cheeses.

A few days later, the mold was back, so he scrubbed down the cheeses again. He did this several more times over the course of the next few weeks.

To his horror, the cheeses he scrubbed down did not turn into the Brie-style rounds he was expecting — they were sticky, tinged red-orange, and stank to high heaven. He pulled aside a more experienced monk for guidance, but he had never seen such a thing, either. Those monks pulled aside yet a more experienced monk, and he was similarly perplexed.

Because this was the Middle Ages and food could not be wasted, someone had to taste it. The young monk took a little taste and, to his surprise, the cheese was savory and unctuous, like a meat custard. He offered it to the other monks, who tried it and enjoyed it also. They liked the meatiness of it so much, they started using it as a meat replacement during fasting.

Soon, the volume explains, the cheeses “became an important source of income to the monastery.” From there, the technique spread, eventually leading to the range of washed rinds we have available today.

For those looking to try this historic style but are wary of the funk, there are mild versions available. These include Taleggio, Morbier, and Von Trapp Oma. On the younger side (ask your cheesemonger!), these washed-rind cheeses will be less funky and more mushroomy.

The article The Monks Who Accidentally Invented Washed-Rind ‘Stinky’ Cheese appeared first on VinePair.

source https://vinepair.com/articles/monks-accidentally-invented-washed-rind-cheese/ source https://vinology1.tumblr.com/post/612023999064571904

0 notes

Text

The Monks Who Accidentally Invented Washed-Rind Stinky Cheese

Those who have walked into a cheese shop and thought, “It smells amazing in here! And also kind of like feet!” have smelled the glory of washed-rind cheeses. Sometimes called “stinky cheese,” these are the cheeses like Époisses, Taleggio, Munster, and Ardrahan that can smell as gentle as yeasty bread dough, or as strong as a teenage athlete’s dirty sock — or even death itself.

In fact, in the 19th century, the process of making this style of cheese was called “putrefactive fermentation” — in other words, “death-like fermentation.”

In order to create these sometimes atrocious-smelling cheeses, makers take a cheese that would have otherwise become a Brie-style cheese and gently scrub it down with a brine solution or a diluted solution of wine, beer, or another alcoholic beverage. In doing so, a new host of bacteria starts growing on the cheese, including one called Brevibacterium linens (often shortened to B. linens).

B. Linens, explains Michelle Vieira, Certified Cheese Professional, cheesemonger at Whole Foods, and creator of Instagram-based blog Columbus Curd Nerd, is “the same bacteria found in the sweaty, smelly zones on the body, which is why washed rinds often smell like dirty socks. This bacteria likes warm and wet areas.”

Especially for those of us who grew up with yellow cheddar slices that don’t smell like much at all, feety washed rinds are a real stretch. Why would anyone choose to put that in their mouth?

Well, most of these cheeses don’t taste nearly as strong as they smell, and “they often boast salty, meaty notes,” explains Vieira.

And, depending on who’s telling the story, that was either an incredible invention or a wonderful accident. According to “The Oxford Companion to Cheese,” the first washed-rind cheese on record, in the 7th century, was Munster, made by monks in Alsace-Lorraine. The name is said to come from the Latin monastarium, meaning “monastery.”

“Monastic life is ideally suited to cheesemaking,” explains “The Oxford Companion to Cheese,” “with its rigorous and repetitive daily routines.”

“The Rule of St. Benedict,” a book written in 516 to guide monks living under an abbot, proclaims, “Idleness is the enemy of the soul. The brethren, therefore must be occupied at stated hours in labor … for then are they truly monks when they live by the labor of their hands.”

Often, the monks would fast from meat, for both logistical and religious reasons.

How, though, did they discover this method of washing down cheese to bring out its funky side? One way that it may have happened (and the story that many cheesemongers tell inquisitive customers) is this:

Benedictine monks in the Middle Ages made many wonderful, often-fermented food products, including bread, cheese, wine, and beer. At some point, alcohol was put to use as an effective sanitizing solution, as was brine.

As the story goes, there was a young, pious monk on cheese duty one day who noticed a new mold growing on his cheeses. Not one to be bested by scary new molds, he grabbed his sanitizing bucket (which would have held a diluted alcohol or brine solution) and scrubbed down the moldy cheeses.

A few days later, the mold was back, so he scrubbed down the cheeses again. He did this several more times over the course of the next few weeks.

To his horror, the cheeses he scrubbed down did not turn into the Brie-style rounds he was expecting — they were sticky, tinged red-orange, and stank to high heaven. He pulled aside a more experienced monk for guidance, but he had never seen such a thing, either. Those monks pulled aside yet a more experienced monk, and he was similarly perplexed.

Because this was the Middle Ages and food could not be wasted, someone had to taste it. The young monk took a little taste and, to his surprise, the cheese was savory and unctuous, like a meat custard. He offered it to the other monks, who tried it and enjoyed it also. They liked the meatiness of it so much, they started using it as a meat replacement during fasting.

Soon, the volume explains, the cheeses “became an important source of income to the monastery.” From there, the technique spread, eventually leading to the range of washed rinds we have available today.

For those looking to try this historic style but are wary of the funk, there are mild versions available. These include Taleggio, Morbier, and Von Trapp Oma. On the younger side (ask your cheesemonger!), these washed-rind cheeses will be less funky and more mushroomy.

The article The Monks Who Accidentally Invented Washed-Rind ‘Stinky’ Cheese appeared first on VinePair.

Via https://vinepair.com/articles/monks-accidentally-invented-washed-rind-cheese/

source https://vinology1.weebly.com/blog/the-monks-who-accidentally-invented-washed-rind-stinky-cheese

0 notes

Text

The Monks Who Accidentally Invented Washed-Rind ‘Stinky’ Cheese

Those who have walked into a cheese shop and thought, “It smells amazing in here! And also kind of like feet!” have smelled the glory of washed-rind cheeses. Sometimes called “stinky cheese,” these are the cheeses like Époisses, Taleggio, Munster, and Ardrahan that can smell as gentle as yeasty bread dough, or as strong as a teenage athlete’s dirty sock — or even death itself.

In fact, in the 19th century, the process of making this style of cheese was called “putrefactive fermentation” — in other words, “death-like fermentation.”

In order to create these sometimes atrocious-smelling cheeses, makers take a cheese that would have otherwise become a Brie-style cheese and gently scrub it down with a brine solution or a diluted solution of wine, beer, or another alcoholic beverage. In doing so, a new host of bacteria starts growing on the cheese, including one called Brevibacterium linens (often shortened to B. linens).

B. Linens, explains Michelle Vieira, Certified Cheese Professional, cheesemonger at Whole Foods, and creator of Instagram-based blog Columbus Curd Nerd, is “the same bacteria found in the sweaty, smelly zones on the body, which is why washed rinds often smell like dirty socks. This bacteria likes warm and wet areas.”

Especially for those of us who grew up with yellow cheddar slices that don’t smell like much at all, feety washed rinds are a real stretch. Why would anyone choose to put that in their mouth?

Well, most of these cheeses don’t taste nearly as strong as they smell, and “they often boast salty, meaty notes,” explains Vieira.

And, depending on who’s telling the story, that was either an incredible invention or a wonderful accident. According to “The Oxford Companion to Cheese,” the first washed-rind cheese on record, in the 7th century, was Munster, made by monks in Alsace-Lorraine. The name is said to come from the Latin monastarium, meaning “monastery.”

“Monastic life is ideally suited to cheesemaking,” explains “The Oxford Companion to Cheese,” “with its rigorous and repetitive daily routines.”

“The Rule of St. Benedict,” a book written in 516 to guide monks living under an abbot, proclaims, “Idleness is the enemy of the soul. The brethren, therefore must be occupied at stated hours in labor … for then are they truly monks when they live by the labor of their hands.”

Often, the monks would fast from meat, for both logistical and religious reasons.

How, though, did they discover this method of washing down cheese to bring out its funky side? One way that it may have happened (and the story that many cheesemongers tell inquisitive customers) is this:

Benedictine monks in the Middle Ages made many wonderful, often-fermented food products, including bread, cheese, wine, and beer. At some point, alcohol was put to use as an effective sanitizing solution, as was brine.

As the story goes, there was a young, pious monk on cheese duty one day who noticed a new mold growing on his cheeses. Not one to be bested by scary new molds, he grabbed his sanitizing bucket (which would have held a diluted alcohol or brine solution) and scrubbed down the moldy cheeses.

A few days later, the mold was back, so he scrubbed down the cheeses again. He did this several more times over the course of the next few weeks.

To his horror, the cheeses he scrubbed down did not turn into the Brie-style rounds he was expecting — they were sticky, tinged red-orange, and stank to high heaven. He pulled aside a more experienced monk for guidance, but he had never seen such a thing, either. Those monks pulled aside yet a more experienced monk, and he was similarly perplexed.

Because this was the Middle Ages and food could not be wasted, someone had to taste it. The young monk took a little taste and, to his surprise, the cheese was savory and unctuous, like a meat custard. He offered it to the other monks, who tried it and enjoyed it also. They liked the meatiness of it so much, they started using it as a meat replacement during fasting.

Soon, the volume explains, the cheeses “became an important source of income to the monastery.” From there, the technique spread, eventually leading to the range of washed rinds we have available today.

For those looking to try this historic style but are wary of the funk, there are mild versions available. These include Taleggio, Morbier, and Von Trapp Oma. On the younger side (ask your cheesemonger!), these washed-rind cheeses will be less funky and more mushroomy.

The article The Monks Who Accidentally Invented Washed-Rind ‘Stinky’ Cheese appeared first on VinePair.

source https://vinepair.com/articles/monks-accidentally-invented-washed-rind-cheese/

source https://vinology1.wordpress.com/2020/03/08/the-monks-who-accidentally-invented-washed-rind-stinky-cheese/

0 notes