#breadfruit and plantations

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The [...] British quest for Tahitian breadfruit and the subsequent mutiny on the Bounty have produced a remarkable narrative legacy [...]. William Bligh’s first attempt to transport the Tahitian breadfruit [from the South Pacific] to the Caribbean slave colonies in 1789 resulted in a well-known mutiny orchestrated by his first mate [...]. [T]he British government [...] successfully transplanted the tree to their slave colonies four years later. [...] [There was a] colonial mania for [...] the breadfruit, [...] [marked by] the British determination to transplant over three thousand of these Tahitian food trees to the Caribbean plantations to "feed the slaves." [...]

Tracing the routes of the breadfruit from the Pacific to the Caribbean, [...] [shows] an effort initiated, coordinated, and financially compensated by Caribbean slave owners [...]. [During] decades worth of lobbying from the West Indian planters for this specific starchy fruit [...] planters [wanted] to avert a growing critique of slavery through a "benevolent" and "humanitarian" use of colonial science [...]. The era of the breadfruit’s transplantation was marked by a number of revolutions in agriculture (the sugar revolution), ideology (the humanitarian revolution), and anticolonialism (the [...] Haitian revolutions) [as well as the American and French revolutions]. [...] By the end of Joseph Banks’ tenure [as a botanist and de facto leader] at the Kew Botanical Gardens [royal gardens in London] (1821), he had personally supervised the introduction of over 7,000 new food and economic plants. [...] Banks produced an idyllic image of the breadfruit [...] [when he had personally visited Tahiti while acting as lead naturalist on Captain James Cook's earlier voyage] in 1769 [...].

---

[I]n the wake of multiple revolutions [...], [breadfruit] was also seen as a panacea for a Caribbean plantation context in which slave, maroon, and indigenous insurrections and revolts in St Vincent and Jamaica were creating considerable anxiety for British planters. [...]

Interestingly, the two islands that were characterized by ongoing revolt were repeatedly solicited as the primary sites of the royal botanical gardens [...]. In 1772, when St Vincentian planters first started lobbying Joseph Banks for the breadfruit, the British militia was engaged in lengthy battle with the island’s Caribs. [...] By 1776, months after one of the largest slave revolts recorded in Jamaica, the Royal Society [administered by Joseph Banks, its president] offered a bounty of 50 pounds sterling to anyone who would transfer the breadfruit to the West Indies. [...] [A]nd planters wrote fearfully that if they were not able to supply food, the slaves would “cut their throats.” It’s widely documented that of all the plantation Americas, Jamaica experienced the most extensive slave revolts [...]. An extensive militia had to be imported and the ports were closed. [...]

By seeking to maintain the plantation hierarchy by importing one tree for the diet of slaves, Caribbean planters sought to delay the swelling tide of revolution that would transform Saint Domingue [Haiti] in the next few years. Like the Royal Society of Science and Arts of Cap François on the eve the Haitian revolution, colonists mistakenly felt they could solve the “political equation of the revolution […] with rational, scientific inquiry.” [...]

---

When the trees arrived in Jamaica in 1793, the local paper reported almost gleefully that “in less than 20 years, the chief article of sustenance for our negroes will be entirely changed.” […] One the one hand, the transplantation of breadfruit represented the planters’ attempt to adopt a “humanitarian” defense against the growing tide of abolitionist and slave revolt. In an age of revolution, [they wanted to appear] to provide bread (and “bread kind”) [...]. This was a point not to be missed by the coordinator of the transplantation, Sir Joseph Banks. In a letter written while the Bounty was being fitted for its initial journey, he summarized how the empire would benefit from new circuits of botanical exchange:

Ceres was deified for introducing wheat among a barbarous people. Surely, then, the natives of the two Great Continents, who, in the prosecution of this excellent work, will mutually receive from each other numerous products of the earth as valuable as wheat, will look up with veneration the monarch […] & the minister who carried into execution, a plan [of such] benefits.

Like giving bread to the poor, Banks articulated this intertropical trade in terms of “exalted benevolence,” an opportunity to facilitate exchange between the peoples of the global south that placed them in subservience to a deified colonial center of global power. […]

---

Bligh had no direct participation in the [slave] trade, but his uncle, Duncan Campbell (who helped commission the breadfruit journey), was a Jamaican plantation owner and had employed Bligh on multiple merchant ships in the Caribbean. Campbell was also deeply involved, with Joseph Banks, in transporting British convicts to the colonies of Australia. In fact Banks’ original plan for the breadfruit voyage was to drop off convicts in (the significantly named) Botany Bay, and then proceed to Tahiti for the breadfruit. Campbell owned a series of politically untenable prison hulks on the Thames which he emptied by shipping his human chattel to the Pacific. Banks helped coordinate these early settlements [...] to encourage white Australian domesticization.

The commodification and rationalist dispersal of plants and human convicts, slaves, the impoverished, women, and other unwilling participants in global transplantation is a rarely told narrative root of colonial “Bounty.”

---

All text above: Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Globalizing the Routes of Breadfruit and Other Bounties”. Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History Volume 8, Number 3, Winter 2007. DOI at: doi dot org slash 10.1353/cch.2008.0003 [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#incredible story of ecology violence hubris landscape cruelty interconnectivity and rebellion#ecology#multispecies#abolition#colonial#imperial#landscape#caribbean#indigenous#elizabeth deloughrey#breadfruit and plantations#kathryn yusoff#indigenous pedagogies#black methodologies#ecologies

117 notes

·

View notes

Photo

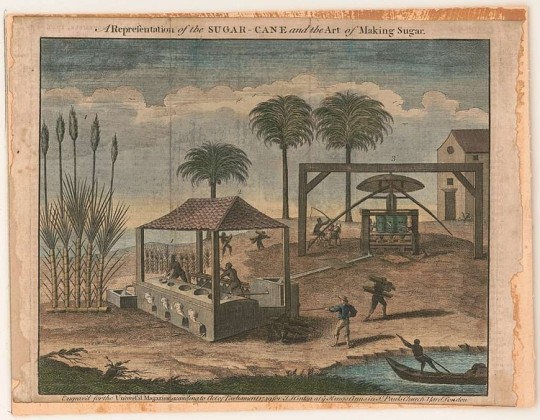

Sugar & the Rise of the Plantation System

From a humble beginning as a sweet treat grown in gardens, sugar cane cultivation became an economic powerhouse, and the growing demand for sugar stimulated the colonization of the New World by European powers, brought slavery to the forefront, and fostered brutal revolutions and wars.

The geographic center of sugar cane cultivation shifted gradually across the world over a span of 3,000 years from India to Persia, along the Mediterranean to the islands near the coast of Africa and then the Americas, before shifting back across the globe to Indonesia. A whole new kind of agriculture was invented to produce sugar – the so-called Plantation System. In it, colonists planted large acreages of single crops which could be shipped long distances and sold at a profit in Europe. To maximize the productivity and profitability of these plantations, slaves or indentured servants were imported to maintain and harvest the labor-intensive crops. Sugar cane was the first to be grown in this system, but many others followed including coffee, cotton, cocoa, tobacco, tea, rubber, and most recently oil palm.

Beginnings of Sugar Cultivation

There is no archeological record of when and where humans first began growing sugar cane as a crop, but it most likely occurred about 10,000 years ago in what is now New Guinea. The species domesticated was Saccharum robustum found in dense stands along rivers. The people in New Guinea were among the most inventive agriculturalists the world has known. They domesticated a broad range of local plant species including not only sugar cane but also taro, bananas, yam, and breadfruit.

The cultivation of sugar cane moved steadily eastward across the Pacific, spreading to the adjacent Solomon Islands, the New Hebrides, New Caledonia, and ultimately to Polynesia. Cultivation of sugar cane also moved westward into continental Asia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and then Northern India. During this advancement, S. officinarum ("nobel canes") hybridized with a local wild species called S. spontaneum to produce a hybrid, S. sinense ("thin canes"). These hybrids were less sweet and not as robust as pure S. officinarum but were hardier and could be grown much more successfully in subtropical mainlands.

Sugar cane was for eons just chewed as a sweet treat, and it was not until about 3,000 years ago that people in India first began squeezing the canes and producing sugar (Gopal, 1964). For a long time, the Indian people kept the whole process of sugar-making a closely guarded secret, resulting in rich profits through trade across the subcontinent. This all changed when Darius I (r. 522-486 BCE), ruler of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, invaded India in 510 BCE. The victors took the technology back to Persia and began producing their own sugar. By the 11th century CE, sugar constituted a significant portion of the trade between the East and Europe. Sugar manufacturing continued in Persia for nearly a thousand years, under a revolving set of rulers, until the Mongol invasions of the 13th century destroyed the industry.

Continue reading...

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The rise of plantation capital spawned the drying of the west side of Maui,” said Kamana Beamer, a historian and a former member of the Hawaii commission on water resource management, which is charged with protecting and regulating water resources. “You can see the link between extractive, unfettered capitalism at the expense of our natural resources and the ecosystem.” Drawn to Hawaii’s temperate climate and prodigious rainfall, sugar and pineapple white magnates began arriving on the islands in the early 1800s. For much of the next two centuries, Maui-based plantation owners like Alexander & Baldwin and Maui Land & Pineapple Company reaped enormous fortunes, uprooting native trees and extracting billions of gallons of water from streams to grow their thirsty crops. (Annual sugar cane production averaged 1m tons until the mid-1980s; a pound of sugar requires 2,000lb of freshwater to produce.) Invasive plants that were introduced as livestock forage, like guinea grass, now cover a quarter of Hawaii’s surface area. The extensive use of pesticides on Maui’s pineapple fields poisoned nearby water wells. The dawn of large-scale agriculture dramatically changed land practices in Maui, where natural resources no longer served as a mode of food production or a habitat for birds but a means of generating fast cash, said Lucienne de Naie, an east Maui historian and chair of the Sierra Club Maui group. “The land was turned from this fertile plain – with these big healthy trees, wetland taros and dryland crops like banana and breadfruit – to a mass of monoculture: to rows and rows of sugar cane, and rows and rows of pineapple,” she said.

[...]

In Hawaii, water is held in a public trust controlled by the government for the people. But on Maui, 16 of the top 20 water users are resorts, time-shares and short-term condominium rentals equipped with emerald golf courses and glittering pools, according to a 2020 report from the county’s board of water supply. The 40-acre Grand Wailea resort, the island’s largest water consumer, devoured half a million gallons of water daily – the amount needed to supply more than 1,400 single-family homes.

144 notes

·

View notes

Quote

In the late 18th century, when the Hawaiian Kingdom became a sovereign state, Lahaina carried such an abundance of water that early explorers reportedly anointed it “Venice of the Pacific”. A glut of natural wetlands nourished breadfruit trees, extensive taro terraces and fishponds that sustained wildlife and generations of Native Hawaiian families. But more than a century and a half of plantation agriculture, driven by American and European colonists, have depleted Lahaina’s streams and turned biodiverse food forests into tinderboxes. Today, Hawaii spends $3bn a year importing up to 90% of its food. This altered ecology, experts say, gave rise to the 8 August blaze that decimated the historic west Maui town and killed more than 111 people. “The rise of plantation capital spawned the drying of the west side of Maui,” said Kamana Beamer, a historian and a former member of the Hawaii commission on water resource management, which is charged with protecting and regulating water resources. “You can see the link between extractive, unfettered capitalism at the expense of our natural resources and the ecosystem.”

How 18th-century pineapple plantations turned Maui into a tinderbox | Hawaii fires | The Guardian

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our Last Day In Paradise

Thursday 27th February 2025 – Tahiti (Day 2)

Last night’s dinner in the hotel, being a Wednesday, included a Polynesian floor-show, somewhat akin to the one we saw on the ship in Bora Bora only louder! I must confess though, that when those drums really got going, it was definitely a case of “Stand by for action! We are about to launch Stingray!” (that’s a Gerry Anderson ‘in-joke’ by the way!)

As for the food, I think the Mosquitos or whatever flies here enjoyed me more than I did the Polynesian buffet – but there was lots to choose from, including 101 ways to cook breadfruit!

Today, we took a 3-hour private taxi tour of a few of the sights on the north-east coast.

First stop was the Fa’aruma’i Falls where, because of previous heavy rains, only Vaimahuta Waterfall was accessible.

However, at some 80m, it’s highest of three at this site and it’s a beautiful and romantic spot. The ancient mythology associated with these falls is a sad story, which our lovely guide Nicholas told to us, but once here, you could really feel a special earth-energy at work!

Next stop was at Venus Point, so called because it was where Captain Cook came to observe the transit of Venus in 1769. A lighthouse was later erected here by the French to commemorate it.

English missionaries also landed and settled here in 1797 and there’s a small monument to them.

As well as some popular black sand beaches, there’s also a monument to the notorious Captain Bligh who arrived in 1788 to collect breadfruit plants as a cheap food-source for the slave plantations in the Caribbean. But the terrible conditions in which the crew had to work ultimately led to the Mutiny; and the rest is history! Watch ‘Mutiny on the Bounty’!

There is no coral reef protecting the coast on this side of the island which is exposed to the prevailing trade winds and a number of bays are popular for surfing.

Our last stop was at the Tahara’a Belvedere, a gorgeous viewpoint overlooking Lafayette Bay and the city of Pape’ete.

Our guide, Nicholas, was knowledgeable and really nice; the temperature, compared to yesterday in the upper 90s, was about 80 today, and with lower humidity too, it was much more bearable. In fact, we had a lovely time and came back to our rather plush hotel for a light lunch overlooking its own private lagoon. It’s a hard life being an international tourist!

Our ‘light lunch’ turned out to be the Gourmet Charcuterie sharing platter; they never said is could have fed a small army! We needed a nap after that…..

Tomorrow, we will be up before the cock crows (literally here!) because our taxi pick-up for the airport is at 5.30am!

#south pacific#regent seven seas#seven seas voyager#tahiti#papeete#captain bligh#captain cook#venus point#faarumai waterfalls#vaimahuta falls#taharaa belvedere

0 notes

Text

peer reviewed tags:

see also following post on circa 1914 US and British doctor perception of their role as de facto colonial administrators

wherein president of rock foundation explicitly describes their function as placating workingclass and nonwhite people

through means of basic concessions and piecemeal philanthropy because they acknowledged that outright state suppression at gunpoint

ran the risk of pissing off too many observers and the masses so they needed to be more careful about methods of coercion

which you can extrapolate among other metropolitan benefactors of US and british empires at that time

in how they understood themselves as bastions of modernity or reformism using Modern Science to Sustainably Exploit

similar to arguments about how US New Deal concessions were about extending life of capital and empire in face of broad popular criticism

as scholarly literature on postcolonialism and history of science might call professional technicians like them Agents Of Emire

might also see British infrastructure engineering in India or academic ethnographers in European race science of later nineteenth cent

similar to British imperial botanist Joseph Banks 1790s plan to cultivate breadfruit to prevent famine leading to slave uprisings

or British industrialization of tea plantation in Assam or rubber plantations in Malaya

the compulsion to justify the coercion with argument that Sustainable Exploitation is modern and necessarily therefore benevolent

or 1914ish medical doctors explicitly seeing themselves as entwined with industrial development of tropical resources

post in question:

From their inception, foundations focused on research and dissemination of information designed ostensibly to ameliorate social issues--in a manner, however, that did not challenge capitalism. For instance, in 1913, Colorado miners went on strike against Colorado Fuel and Iron, an enterprise of which 40 percent was owned by Rockefeller. Eventually, this strike erupted into open warfare, with the Colorado militia murdering several strikers during the Ludlow Massacre of April 20, 1914. During that same time, Jerome Greene, the Rockefeller Foundation secretary, identified research and information to quiet social and political unrest as a foundation priority. The rationale behind this strategy was that while individual workers deserved social relief, organized workers in the form of unions were a threat to society. So the Rockefeller Foundation heavily advertised its relief work for individual workers while at the same time promoting a pro-Rockefeller spin to the massacre. For instance, it sponsored speakers to claim that no massacre has happened and tried to block the publication of reports that were critical of Rockefeller. According to Frederick Gates, who helped run the Rockefeller Foundation, the "danger is not the combination of capital, it is not the Mexican situation, it is the labor monopoly; and the danger of the labor monopoly lies in its use of armed force, its organized and deliberate war on society."

INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence, The Revolution Will Not be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hanalei Bay, Kaua'i, Hawai'i.

Located on the mouth of the Hanalei river, the area was very productive with the ancient settlers who grew a bounty of taro, banana, coconuts, yams and breadfruit. With foreigners settling, more introduced crops of cotton, rice, sugar cane, potatoes, various greens and tropical fruits were introduced into the area. Around the 1900s, the area was filled with sugar cane and rice fields from farmers with Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Portuguese and other migrant groups to work the plantation farms.

0 notes

Text

KE AUPUNI UPDATE - AUGUST 2023

Food Sovereignty The tragedy in Lāhainā continues to unfold. A century and a half of reckless resource management, especially land use and water allocation, in favor of commercial greed — first, massive plantations, then massive tourism, then massive developments and land speculation — have put much of Hawaii in grave danger of not only what transpired in Lāhainā, but in other serious ways as well. Add to that the real-time bureaucratic mentality of state officials who put strict obedience to rules and orders before common sense and people’s lives, and you have a formula for disaster. Under the U.S. system, money is the measure of importance. Corporations and companies that generate money are highly favored and receive first priority, even when it comes to law. Ordinary people like you and me are not seen as living, breathing human beings. We are taxpayers, whose labor and energy are revenue streams to feed the system. In that system, nature is something to be exploited, not cared for. Original languages and cultures are only allowed if they have commercial value. (Ironically, our songs, the hula, and our language, like the word Aloha, survived because they were money-makers for the tourism industry) This is the colonial system that has permeated practically every nook and cranny of the world. Not only has it disrupted, polluted and disfigured native habitats, destroyed native economies and social systems, it has altered what we eat — unhealthy processed and ʻjunkʻ food causing catastrophic health problems among native people. Then there is the perilous dependency on importing what we eat. Ninety percent of the food consumed in Hawaii is shipped in from the States. That means, only ten percent is grown in Hawaii. If shipping was to stop, after two weeks, Hawaii will run out of food and things will get very ugly. Hawaii will never be truly independent, unless we can feed ourselves. For the past 20 years those who have been aware of Hawaii’s vulnerability have been sounding the alarm and some progress is being made in planting more food crops. There are many who are answering the call of back to the ‘aina to plant for our future. But there needs to be a concerted effort to not only grow more food, but to change the diet habits of our people to eat the fantastically nutritious traditional foods that our ancestors brought in their canoes, like Kalo (Taro)...ʻUlu (Breadfruit)...Maiʻa (Banana)...ʻUala (Sweet Potato)...Niu (Coconut)...

“Love of country is deep-seated in the breast of every Hawaiian, whatever his station.” — Queen Liliʻuokalani ---------- Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono. The sovereignty of the land is perpetuated in righteousness.

------ For the latest news and developments about our progress at the United Nations in both New York and Geneva, tune in to Free Hawaii News at

6 PM the first Friday of each month on ʻŌlelo Television, Channel 53.

------ "And remember, for the latest updates and information about the Hawaiian Kingdom check out the twice-a-month Ke Aupuni Updates published online on Facebook and other social media." PLEASE KŌKUA… Your kōkua, large or small, is vital to this effort... To contribute, go to:

• GoFundMe – CAMPAIGN TO FREE HAWAII • PayPal – use account email: [email protected] • Other – To contribute in other ways (airline miles, travel vouchers, volunteer services, etc...) email us at: [email protected] “FREE HAWAII” T-SHIRTS - etc. Check out the great FREE HAWAII products you can purchase at... http://www.robkajiwara.com/store/c8/free_hawaii_products All proceeds are used to help the cause. MAHALO! Malama Pono,

Leon Siu

Hawaiian National

#ke aupuni#leon siu#hawaiian kingdom#kingdom of hawaii#koani foundation#free hawaii#washington free beacon

0 notes

Text

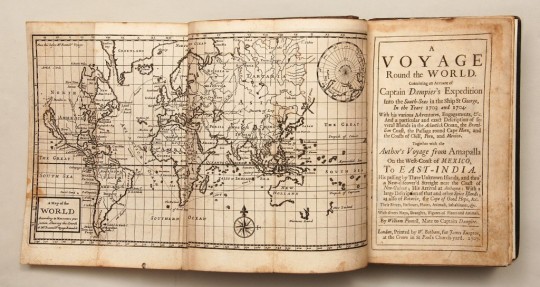

A 1697 oil painting of Dampier holding a book. Credit: National Portrait Gallery / Public Domain.

For all the perceived glamour of piracy, its practitioners lived poorly and ate worse. Skirting death, mutiny, and capture left little room for comfort or transformative culinary experience. The greatest names in piracy, wealthy by the day’s standards, ate as one today might on a poorly provisioned camping trip: dried beef, bread, and warm beer. Those of lesser fame were subject to cannibalism and scurvy. The seas were no place for an adventurous appetite.

But when one gifted pirate permitted himself a curiosity for food, he played a pioneering role in spreading ingredients and cuisines. He gave us the words “tortilla,” “soy sauce,” and “breadfruit,” while unknowingly recording the first ever recipe for guacamole. And who better to expose the Western world to the far corners of our planet’s culinary bounty than someone who by necessity made them his hiding places?

British-born William Dampier began a life of piracy in 1679 in Mexico’s Bay of Campeche. Orphaned in his late teens, Dampier set sail for the Caribbean and fell into a twentysomething job scramble. Seeing no future in logging or sugar plantations, he was sucked into the burgeoning realm of New World raiding, beginning what would be the first of his record-breaking three circumnavigations. A prolific diarist, Dampier kept a journal wrapped in a wax-sealed bamboo tube throughout his journeys. During a year-long prison sentence in Spain in 1694, Dampier would convert these notes into a novel that became a bestseller and seminal travelogue.

Parts of A New Voyage Around the World read like a 17th-century episode of No Reservations, with Dampier playing a high-stakes version of Anthony Bourdain. Aside from writing groundbreaking observations on previously un-researched subjects in meteorology, maritime navigation, and zoology, food was a constant throughout his work. He ate with the locals, observing and employing their practices not only to feed himself and his crew but to amass a body of knowledge that would expand European understanding of non-Western cuisine. In Panama, Dampier traveled with men of the Miskito tribe, hunting and eating manatee. “Their flesh is … [extraordinarily] sweet, wholesome meat,” he wrote. “The tail of a young cow is most esteemed. A calf that sucks is the most delicate meat.” His crew took to roasting filleted bellies over open flames.

Dampier was later smitten, on the island of Cape Verde, by the taste of flamingo. “The flesh of both young and old is lean and black, yet very good meat, tasting neither fishy [nor] any way unsavoury,” he wrote. “Their tongues are large, having a large knob of fat at the root, which is an excellent bit: a dish of flamingo’s tongue [is] fit for a prince’s table.” Of Galapagos penguins, Dampier found “their flesh ordinary, but their eggs [to be] good meat.” He also became a connoisseur of sea turtles, having developed a preference for grass-fed specimens of the West Indies: “They are the best of that sort, both for largeness and sweetness.”

Dampier’s legacy sparked the infamous Mutiny on the Bounty. Credit: National Maritime Museum / Public Domain.

While you won’t find flamingos, penguins, or turtles on too many contemporary menus, several contributions from A New Voyage reshaped our modern English food vocabulary.* In the Bay of Panama, Damier wrote of a fruit “as big as a large lemon … [with] skin [like] black bark, and pretty smooth.” Lacking distinct flavor, he wrote, the ripened fruit was “mixed with sugar and lime juice and beaten together [on] a plate.” This was likely the English language’s very first recipe for guacamole. Later, in the Philippines, Dampier noted of young mangoes that locals “cut them in two pieces and pickled them with salt and vinegar, in which they put some cloves of garlic.” This was the English language’s first recipe for mango chutney. His use of the terms “chopsticks,” “barbecue,” “cashew,” “kumquat,” “tortilla,” and “soy sauce” were also the first of their kind.

One entry, however, would have dire consequences for the Crown and one unfortunate crew in the South Pacific. Dampier wrote passionately of a Tahitian fruit: “When [it] is ripe it is yellow and soft; and the taste is delicious … The inside is soft, tender, and white, like the crumb of a pennyloaf.” He and his men dubbed it breadfruit. For British sugar planters of the West Indies, who struggled to feed their slaves on small plots of land, these broad-branched, fast-growing, nutritious fruits, which required little cultivation and stood up to hurricane winds, rang of an ideal solution. Dampier unknowingly sold the British on breadfruit, which served as the impetus for a British mission to bring a thousand potted breadfruit trees from the South Pacific around the Horn of Africa to the West Indies. With the ship retrofitted to shelter the saplings, the miserably crammed and mistreated crew mutinied, leading to the fiasco, book, and film that came to be known as the Mutiny on the Bounty.

In the years following its publication, A New Voyage became an international bestseller, skyrocketing Dampier to wealth and fame. The first of its kind, the work generated a hunger among European audiences for travel writing, serving as an inspiration for Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. Charles Darwin brought a copy of A New Voyage with him aboard the Beagle’s voyage to South America, having cited the book as a “mine of information.” Noting his keen eye for wind and current mapping, the British Royal Navy consulted him on best practices, later extending him captainship of the HMS Roebuck, on which he was commissioned for an in-depth exploration of South Africa, Australia, and Indonesia.

Despite the popular excusal of his pirating days, Dampier eluded long-term renown due to one entry from A New Voyage. His observations on the aboriginals of Australia were employed, decades after its publication, as justification for the colonization of Oceania and the subsequent genocide of its original inhabitants. In 1697, he wrote that “the inhabitants of this country are the miserablest people in the world. They differ but little from brutes.” And indeed, viewing the aboriginals on a scientific expedition in 1770, Sir Joseph Banks, president of the British Royal Society and advisor to King George III, wrote, “So far did the prejudices which we had built on Dampier’s account influence us that we fancied we could see their color when we could scarce distinguish whether or not they were men.” The later publication of a full transcript of Dampier’s journals does indicate an up-close and far more favorable analysis of the aboriginals, yet by then the Crown’s campaign to colonize was well underway, and his reputation as a bigot was sown. For generations, Dampier was taught throughout much of the Commonwealth as, first and only, a piratical figure.

Other negative testimony accumulated against him in court-martials later on as well: He lost the Roebuck to a leak and was accused of mistreating and even marooning subordinates—par for the course in the life of a pirate. Disgraced and indebted by court fines, Dampier died penniless, and his exploits became mere footnotes between the nary-criminal lives of Sir Walter Raleigh and James Cook. Nevertheless, each time you order avocado toast, call some friends over for a barbecue, or ask for a pair of chopsticks, you are living Dampier’s legacy.

#guacamole#The Pirate Who Penned the First English-Language Guacamole Recipe#cooking#global food#recipes

0 notes

Text

Buccaneer, Navigator and Explorer

William Dampier was born in Somerset, England, in 1652. Orphaned as a teenager, he began his naval career as an apprentice to a ship's captain on a voyage to the fishing grounds of Newfoundland. He hated the cold so much, however, that he spent the rest of his voyages in the tropics, first as a sailor in front of the mast on an East Indiaman to Java. When he returned, he served for a time in the Royal Navy. He then worked, in 1674, as manager of a sugar plantation in Jamaica, after which he found employment with the loggers at Campeachy, Mexico.

William Dampier, by Thomas Murray, about 1697–98 (x)

The dye from the logs was highly prized for textiles, but it was strenuous work. The area was the hotbed of English buccaneers at the time and Dampier was attracted to their free-spirited lifestyle. Much of his life from then on was buccaneering. He never hid his buccaneering voyages btw, but never glorified this activity, describing it as soberly as he did his observations of nature. It was a particularly pretty town with a beautifully decorated church. (...) When they refused to pay us the ransom, we burned it down.

Dampier circumnavigated the globe three times, visiting all five continents and entering regions of the world largely unknown to Europeans. When he wasn't busy pillaging, he made careful notes about the places he visited, their geography, botany, food, zoology and the culture of the local people. He was the first to describe the banana and the flamingo, the breadfruit and the sloth, the barbecue, the avocado and the chopsticks.

He carried his diary in a piece of bamboo sealed with wax at both ends. It was published in 1697 as A New Voyage Around the World and was followed by several other popular books, like Voyages and Descriptions (1699), A Voyage to New Holland (1703), A Supplement of the Voyage Round the World (1705), The Campeachy Voyages (1705), A Discourse of Winds (1705) and A Continuation of a Voyage to New Holland (1709)

A Voyage Round the World (x)

As a result, Dampier was taken up by London society and he gained the fame of the British Admiralty. In 1699 he was sent on a voyage of discovery around Australia with HMS Roebuck. Unfortunately, he lost the ship when it was wrecked at Ascension Island, which precluded further employment with the Royal Navy and he even had to stand trial. He went back to buccaneering in that case more piracy. On 11 September 1703, he set sail with the St George and the Chinque Ports Gallery.

His drawings, in : Continuation of a Voyage to New Holland in the year 1699 (x)

The voyage against French or Spanish ships around the world lasted from 1703 to 1707, but again did not bring the hoped-for success. The St. George soon ran aground and the crew fell into Spanish captivity. Dampier failed due to his inability as captain to keep the crew in line. The voyage resulted in the voluntary abandonment of Alexander Selkirk (Daniel Dafoe later used his life on the island for his novel Robinson Crusoe) on the uninhabited island of Mas a Tierra in the Juan Fern��ndez Archipelago in 1704. This island was renamed Isla Robinson Crusoe in 1966. Dampier experienced a third circumnavigation of the globe in 1708-1711 as navigator on the ship of Privateer captain Woodes Rogers. This capture tour resulted in plentiful booty. During a stopover to replenish fresh water on Isla Mas a Tierra, Alexander Selkirk was found again and taken on board by Rogers. Before the now over-indebted Dampier could be paid his share of the capture proceeds, however, the adventurer died in London in 1715.

Future mariners benefited from Dampier's geographical surveys and observations, especially his A Supplement of the Voyage Round the World 1705

A Supplement of the Voyage Round the World 1705 (x)

This was the world's first integrated account of the direction and extent of the trade wind systems and main currents around the world. His research reports and chart work were to be considered standard works for generations to come and influenced almost all his more famous successors such as James Cook, William Bligh and Admiral Nelson into the nineteenth century: even Humboldt, Darwin and Sir John Franklin carried their Dampier in their shipboard library as a matter of course.

@sanguinarysanguinity

#naval history#buccaneer#explorer#William Dampier#17th-18th century#age of sail#this just a short overview

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

imperialism and science reading list

edited: by popular demand, now with much longer list of books

Of course Katherine McKittrick and Kathryn Yusoff.

People like Achille Mbembe, Pratik Chakrabarti, Rohan Deb Roy, Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, and Elizabeth Povinelli have written some “classics” and they track the history/historiography of US/European scientific institutions and their origins in extraction, plantations, race/slavery, etc.

Two articles I’d recommend as a summary/primer:

Zaheer Baber. “The Plants of Empire: Botanic Gardens, Colonial Power and Botanical Knowledge.” Journal of Contemporary Asia. May 2016.

Kathryn Yusoff. “The Inhumanities.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 2020.

Then probably:

Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Colette Le Petitcorps. “Introduction: Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times.” Global Plantations in the Modern World: Sovereignties, Ecologies, Afterlives. 2023.

Sharae Deckard. “Paradise Discourse, Imperialism, and Globalization: Exploiting Eden.” 2010. (Chornological overview of development of knowledge/institutions in relationship with race, slavery, profit as European empires encountered new lands and peoples.)

Gregg Mitman. “Forgotten Paths of Empire: Ecology, Disease, and Commerce in the Making of Liberia’s Plantation Economy.” Environmental History. 2017, (Interesting case study. US corporations were building fruit plantations in Latin America and rubber plantations in West Africa during the 1920s. Medical doctors, researchers, and academics made a strong alliance these corporations to advance their careers and solidify their institutions. By 1914, the director of Harvard’s Department of Tropical Medicine was also simultaneously the director of the Laboratories of the Hospitals of the United Fruit Company, which infamously and brutally occupied Central America. This same Harvard doctor was also a shareholder in rubber plantations, and had a close personal relationship with the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, which occupied West Africa.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Globalizing the Routes of Breadfruit and Other Bounties.” 2008. (Case study of how British wealth and industrial development built on botany. Examines Joseph Banks; Kew Gardens; breadfruit; British fear of labor revolts; and the simultaneous colonizing of the Caribbean and the South Pacific.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Satellite Planetarity and the Ends of the Earth.” 2014. (Indigenous knowledge systems; “nuclear colonialism”; US empire in the Pacific; space/satellites; the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.)

Fahim Amir. “Cloudy Swords.” e-flux Journal #115, February 2021. (”Pest control”; termites; mosquitoes; fear of malaria and other diseases during German colonization of Africa and US occupations of Panama and the wider Caribbean; origins of some US institutions and the evolution of these institutions into colonial, nationalist, and then NGO forms over twentieth century.)

Some of the earlier generalist classic books that explicitly looked at science as a weapon of empires:

Schiebinger’s Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World; Delbourgo’s and Dew’s Science and Empire in the Atlantic World; the anthology Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World; Canzares-Esquerra’s Nature, Empire, and Nation: Explorations of the History of Science in the Iberian World.

One of the quintessential case studies of science in the service of empire is the British pursuit of quinine and the inoculation of their soldiers and colonial administrators to safeguard against malaria in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia at the height of their power. But there are so many other exemplary cases: Britain trying to domesticate and transplant breadfruit from the South Pacific to the Caribbean to feed laborers to prevent slave uprisings during the age of the Haitian Revolution. British colonial administrators smuggling knowledge of tea cultivation out of China in order to set up tea plantations in Assam. Eugenics, race science, biological essentialism, etc. in the early twentieth century. With my interests, my little corner of exposure/experience has to do mostly with conceptions of space/place; interspecies/multispecies relationships; borderlands and frontiers; Caribbean; Latin America; islands. So, a lot of these recs are focused there. But someone else would have better recs, especially depending on your interests. For example, Chakrabarti writes about history of medicine/healthcare. Paravisini-Gebert about extinction and Caribbean relationship to animals/landscape. Deb Roy focuses on insects and colonial administration in South Asia. Some scholars focus on the historiography and chronological trajectory of “modernity” or “botany” or “universities/academia,”, while some focus on Early Modern Spain or Victorian Britain or twentieth-century United States by region. With so much to cover, that’s why I’d recommend the articles above, since they’re kinda like overviews.Generally I read more from articles, essays, and anthologies, rather than full-length books.

Some other nice articles:

(On my blog, I’ve got excerpts from all of these articles/essays, if you want to search for or read them.)

Katherine McKittrick. “Dear April: The Aesthetics of Black Miscellanea.” Antipode. First published September 2021.

Katherine McKittrick. “Plantation Futures.” Small Axe. 2013.

Antonio Lafuente and Nuria Valverde. “Linnaean Botany and Spanish Imperial Biopolitics.” A chapter in: Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World. 2004.

Kathleen Susan Murphy. “A Slaving Surgeon’s Collection: The Pursuit of Natural History through the British Slave Trade to Spanish America.” 2019. And also: “The Slave Trade and Natural Science.” In: Oxford Bibliographies in Atlantic History. 2016.

Timothy J. Yamamura. “Fictions of Science, American Orientalism, and the Alien/Asian of Percival Lowell.” 2017.

Elizabeth Bentley. “Between Extinction and Dispossession: A Rhetorical Historiography of the Last Palestinian Crocodile (1870-1935).” 2021.

Pratik Chakrabarti. “Gondwana and the Politics of Deep Past.” Past & Present 242:1. 2019.

Jonathan Saha. “Colonizing elephants: animal agency, undead capital and imperial science in British Burma.” BJHS Themes. British Society for the History of Science. 2017.

Zoe Chadwick. “Perilous plants, botanical monsters, and (reverse) imperialism in fin-de-siecle literature.” The Victorianist: BAVS Postgraduates. 2017.

Dante Furioso: “Sanitary Imperialism.” Jeremy Lee Wolin: “The Finest Immigration Station in the World.” Serubiri Moses. “A Useful Landscape.” Andrew Herscher and Ana Maria Leon. “At the Border of Decolonization.” All from e-flux.

William Voinot-Baron. “Inescapable Temporalities: Chinook Salmon and the Non-Sovereignty of Co-Management in Southwest Alaska.” 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “White ants, empire, and entomo-politics in South Asia.” The Historical Journal. 2 October 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “Introduction: Nonhuman Empires.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 35 (1). May 2015.

Lawrence H. Kessler. “Entomology and Empire: Settler Colonial Science and the Campaign for Hawaiian Annexation.” Arcadia (Spring 2017).

Sasha Litvintseva and Beny Wagner. “Monster as Medium: Experiments in Perception in Early Modern Science and Film.” e-flux. March 2021.

Lesley Green. “The Changing of the Gods of Reason: Cecil John Rhodes, Karoo Fracking, and the Decolonizing of the Anthropocene.” e-flux Journal Issue #65. May 2015.

Martin Mahony. “The Enemy is Nature: Military Machines and Technological Bricolage in Britain’s ‘Great Agricultural Experiment.’“ Environment and Society Portal, Arcadia. Spring 2021.

Anna Boswell. “Anamorphic Ecology, or the Return of the Possum.” 2018. And; “Climates of Change: A Tuatara’s-Eye View.”2020. And: “Settler Sanctuaries and the Stoat-Free State." 2017.

Katherine Arnold. “Hydnora Africana: The ‘Hieroglyphic Key’ to Plant Parasitism.” Journal of the History of Ideas - JHI Blog - Dispatches from the Archives. 21 July 2021.

Helen F. Wilson. “Contact zones: Multispecies scholarship through Imperial Eyes.” Environment and Planning. July 2019.

Tom Brooking and Eric Pawson. “Silences of Grass: Retrieving the Role of Pasture Plants in the Development of New Zealand and the British Empire.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. August 2007.

Kirsten Greer. “Zoogeography and imperial defence: Tracing the contours of the Neactic region in the temperate North Atlantic, 1838-1880s.” Geoforum Volume 65. October 2015. And: “Geopolitics and the Avian Imperial Archive: The Zoogeography of Region-Making in the Nineteenth-Century British Mediterranean.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2013,

Marco Chivalan Carrillo and Silvia Posocco. “Against Extraction in Guatemala: Multispecies Strategies in Vampiric Times.” International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. April 2020.

Laura Rademaker. “60,000 years is not forever: ‘time revolutions’ and Indigenous pasts.” Postcolonial Studies. September 2021.

Paulo Tavares. “The Geological Imperative: On the Political Ecology of the Amazon’s Deep History.” Architecture in the Anthropocene. Edited by Etienne Turpin. 2013.

Kathryn Yusoff. “Geologic Realism: On the Beach of Geologic Time.” Social Text. 2019. And: “The Anthropocene and Geographies of Geopower.” Handbook on the Geographies of Power. 2018. And: “Climates of sight: Mistaken visbilities, mirages and ‘seeing beyond’ in Antarctica.” In: High Places: Cultural Geographies of Mountains, Ice and Science. 2008. And:“Geosocial Formations and the Anthropocene.” 2017. And: “An Interview with Elizabeth Grosz: Geopower, Inhumanism and the Biopolitical.” 2017.

Mara Dicenta. “The Beavercene: Eradication and Settler-Colonialism in Tierra del Fuego.” Arcadia. Spring 2020.

And then here are some books:

Frontiers of Science: Imperialism and Natural Knowledge in the Gulf South Borderlands, 1500-1850 (Cameron B. Strang); Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Londa Schiebinger, 2004);

Africa as a Living Laboratory: Empire, Development, and the Problem of Scientific Knowledge, 1870-1950 (Helen Tilley, 2011); Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar (Jonathan Saha); Fluid Geographies: Water, Science and Settler Colonialism in New Mexico (K. Maria D. Lane, 2024); Geopolitics, Culture, and the Scientific Imaginary in Latin America (Edited by del Pilar Blanco and Page, 2020)

Red Coats and Wild Birds: How Military Ornithologists and Migrant Birds Shaped Empire (Kirsten A. Greer); The Black Geographic: Praxis, Resistance, Futurity (Hawthorne and Lewis, 2022); Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture (Britt Rusert, 2017)

The Empirical Empire: Spanish Colonial Rule and the Politics of Knowledge (Arndt Brendecke, 2016); In the Museum of Man: Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France, 1850-1960 (Alice Conklin, 2013); Unfreezing the Arctic: Science, Colonialism, and the Transformation of Inuit Lands (Andrew Stuhl)

Anglo-European Science and the Rhetoric of Empire: Malaria, Opium, and British Rule in India, 1756-1895 (Paul Winther); Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Sadiah Qureshi, 2011); Practical Matter: Newton’s Science in the Service of Industry and Empire, 1687-1851 (Margaret Jacob and Larry Stewart)

Pasteur’s Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World (Aro Velmet, 2022); Medicine and Empire, 1600-1960 (Pratik Chakrabarti, 2014); Colonial Geography: Race and Space in German East Africa, 1884-1905 (Matthew Unangst, 2022);

The Nature of German Imperialism: Conservation and the Politics of Wildlife in Colonial East Africa (Bernhard Gissibl, 2019); Curious Encounters: Voyaging, Collecting, and Making Knowledge in the Long Eighteenth Century (Edited by Adriana Craciun and Mary Terrall, 2019)

The Ends of Paradise: Race, Extraction, and the Struggle for Black Life in Honduras (Chirstopher A. Loperena, 2022); Mining Language: Racial Thinking, Indigenous Knowledge, and Colonial Metallurgy in the Early Modern Iberian World (Allison Bigelow, 2020); The Herds Shot Round the World: Native Breeds and the British Empire, 1800-1900 (Rebecca J.H. Woods); American Tropics: The Caribbean Roots of Biodiversity Science (Megan Raby, 2017); Producing Mayaland: Colonial Legacies, Urbanization, and the Unfolding of Global Capitalism (Claudia Fonseca Alfaro, 2023); Unnsettling Utopia: The Making and Unmaking of French India (Jessica Namakkal, 2021)

Domingos Alvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World (James Sweet, 2011); A Temperate Empire: Making Climate Change in Early America (Anya Zilberstein, 2016); Educating the Empire: American Teachers and Contested Colonization in the Philippines (Sarah Steinbock-Pratt, 2019); Soundings and Crossings: Doing Science at Sea, 1800-1970 (Edited by Anderson, Rozwadowski, et al, 2016)

Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai’i and Oceania (Maile Arvin); Overcoming Niagara: Canals, Commerce, and Tourism in the Niagara-Great Lakes Borderland Region, 1792-1837 (Janet Dorothy Larkin, 2018); A Great and Rising Nation: Naval Exploration and Global Empire in the Early US Republic (Michael A. Verney, 2022)

Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment (Daniela Cleichmar, 2012); Tea Environments and Plantation Culture: Imperial Disarray in Eastern India (Arnab Dey, 2022); Drugs on the Page: Pharmacopoeias and Healing Knowledge in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Edited by Crawford and Gabriel, 2019)

Cooling the Tropics: Ice, Indigeneity, and Hawaiian Refreshment (Hi’ilei Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart, 2022); In Asian Waters: Oceanic Worlds from Yemen to Yokkohama (Eric Tagliacozzo); Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans (Urmi Engineer Willoughby, 2017); Turning Land into Capital: Development and Dispossession in the Mekong Region (Edited by Hirsch, et al, 2022); Mining the Borderlands: Industry, Capital, and the Emergence of Engineers in the Southwest Territories, 1855-1910 (Sarah E.M. Grossman, 2018)

Knowing Manchuria: Environments, the Senses, and Natural Knowledge on an Asian Borderland (Ruth Rogaski); Colonial Fantasies, Imperial Realities: Race Science and the Making of Polishness on the Fringes of the German Empire, 1840-1920 (Lenny A. Urena Valerio); Against the Map: The Politics of Geography in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Adam Sills, 2021)

Under Osman’s Tree: The Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and Environmental History (Alan Mikhail, 2017); Imperial Nature: Joseph Hooker and the Practices of Victorian Science (Jim Endersby); Proving Grounds: Militarized Landscapes, Weapons Testing, and the Environmental Impact of U.S. Bases (Edited by Edwin Martini, 2015)

Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World (Multiple authors, 2007); Space in the Tropics: From Convicts to Rockets in French Guiana (Peter Redfield); Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850 (Andrew Togert, 2015); Dust Bowls of Empire: Imperialism, Environmental Politics, and the Injustice of ‘Green’ Capitalism (Hannah Holleman, 2016); Postnormal Conservation: Botanic Gardens and the Reordering of Biodiversity Governance (Katja Grotzner Neves, 2019)

Botanical Entanglements: Women, Natural Science, and the Arts in Eighteenth-Century England (Anna K. Sagal, 2022); The Platypus and the Mermaid and Other Figments of the Classifying Imagination (Harriet Ritvo); Rubber and the Making of Vietnam: An Ecological History, 1897-1975 (Michitake Aso); A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Kathryn Yusoff, 2018); Staple Security: Bread and Wheat in Egypt (Jessica Barnes, 2023); No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic (Keith Pluymers); Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1768-1941 (Lynn Hollen Lees, 2017); Fish, Law, and Colonialism: The Legal Capture of Salmon in British Columbia (Douglas C. Harris, 2001); Everywhen: Australia and the Language of Deep Time (Edited by Ann McGrath, Laura Rademaker, and Jakelin Troy)

Subject Matter: Technology, the Body, and Science on the Anglo-American Frontier, 1500-1676 (Joyce Chaplin, 2001); Mapping the Amazon: The Making and Unmaking of French India (Jessica Namakkal, 2021)

American Lucifers: The Dark History of Artificial Light, 1750-1865 (Jeremy Zallen); Ruling Minds: Psychology in the British Empire (Erik Linstrum, 2016); Lakes and Empires in Macedonian History: Contesting the Water (James Pettifer and Mirancda Vickers, 2021); Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity (Pratik Chakrabarti); Seeds of Control: Japan’s Empire of Forestry in Colonial Korea (David Fedman)

Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination (Julie Cruikshank); The Fishmeal Revolution: The Industrialization of the Humboldt Current Ecosystem (Kristin A. Wintersteen, 2021); The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (Ralph O’Connor); An Imperial Disaster: The Bengal Cyclone of 1876 (Benjamin Kingsbury, 2018); Geographies of City Science: Urban Life and Origin Debates in Late Victorian Dublin (Tanya O’Sullivan, 2019)

American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe (John Krige, 2006); Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule (Ann Laura Stoler, 2002); Rivers of the Sultan: The Tigris and Euphrates in the Ottoman Empire (Faisal H. Husain, 2021)

The Sanitation of Brazil: Nation, State, and Public Health, 1889-1930 (Gilberto Hochman, 2016); The Imperial Security State: British Colonial Knowledge and Empire-Building in Asia (James Hevia); Japan’s Empire of Birds: Aristocrats, Anglo-Americans, and Transwar Ornithology (Annika A. Culver, 2022)

Moral Ecology of a Forest: The Nature Industry and Maya Post-Conservation (Jose E. Martinez, 2021); Sound Relations: Native Ways of Doing Music History in Alaska (Jessica Bissette Perea, 2021); Citizens and Rulers of the World: The American Child and the Cartographic Pedagogies of Empire (Mashid Mayar); Anthropology and Antihumanism in Imperial Germany (Andrew Zimmerman, 2001)

The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century (Multiple authors, 2016); The Nature of Slavery: Environment and Plantation Labor in the Anglo-Atlantic World (Katherine Johnston, 2022); Seeking the American Tropics: South Florida’s Early Naturalists (James A. Kushlan, 2020)

The Colonial Life of Pharmaceuticals: Medicines and Modernity in Vietnam (Laurence Monnais); Quinoa: Food Politics and Agrarian Life in the Andean Highlands (Linda J. Seligmann, 2023) ; Critical Animal Geographies: Politics, intersections and hierarchies in a multispecies world (Edited by Kathryn Gillespie and Rosemary-Claire Collard, 2017); Spawning Modern Fish: Transnational Comparison in the Making of Japanese Salmon (Heather Ann Swanson, 2022); Imperial Visions: Nationalist Imagination and Geographical Expansion in the Russian Far East, 1840-1865 (Mark Bassin, 2000); The Usufructuary Ethos: Power, Politics, and Environment in the Long Eighteenth Century (Erin Drew, 2022)

Intimate Eating: Racialized Spaces and Radical Futures (Anita Mannur, 2022); On the Frontiers of the Indian Ocean World: A History of Lake Tanganyika, 1830-1890 (Philip Gooding, 2022); All Things Harmless, Useful, and Ornamental: Environmental Transformation Through Species Acclimitization, from Colonial Australia to the World (Pete Minard, 2019)

Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Setller Colonialism (Jarrod Hore, 2022); Timber and Forestry in Qing China: Sustaining the Market (Meng Zhang, 2021); The World and All the Things upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration (David A. Chang);

Deep Cut: Science, Power, and the Unbuilt Interoceanic Canal (Christine Keiner); Writing the New World: The Politics of Natural History in the Early Spanish Empire (Mauro Jose Caraccioli); Two Years below the Horn: Operation Tabarin, Field Science, and Antarctic Sovereignty, 1944-1946 (Andrew Taylor, 2017); Mapping Water in Dominica: Enslavement and Environment under Colonialism (Mark W. Hauser, 2021)

To Master the Boundless Sea: The US Navy, the Marine Environment, and the Cartography of Empire (Jason Smith, 2018); Fir and Empire: The Transformation of Forests in Early Modern China (Ian Matthew Miller, 2020); Breeds of Empire: The ‘Invention’ of the Horse in Southeast Asia and Southern Africa 1500-1950 (Sandra Swart and Greg Bankoff, 2007)

Science on the Roof of the World: Empire and the Remaking of the Himalaya (Lachlan Fleetwood, 2022); Cattle Colonialism: An Environmental History of the Conquest of California and Hawai’i (John Ryan Fisher, 2017); Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819-1942 (Timothy P. Barnard, 2019)

An Ecology of Knowledges: Fear, Love, and Technoscience in Guatemalan Forest Conservation (Micha Rahder, 2020); Empire and Ecology in the Bengal Delta: The Making of Calcutta (Debjani Bhattacharyya, 2018); Imperial Bodies in London: Empire, Mobility, and the Making of British Medicine, 1880-1914 (Kristen Hussey, 2021)

Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950 (Jeannie N. Shinozuka); Coral Empire: Underwater Oceans, Colonial Tropics, Visual Modernity (Ann Elias, 2019); Hunting Africa: British Sport, African Knowledge and the Nature of Empire (Angela Thompsell, 2015)

#multispecies#ecologies#tidalectics#geographic imaginaries#book recommendations#reading recommendations#reading list#my writing i guess

425 notes

·

View notes

Note

What kind of plants do you grow in the greenhouses? Do any ghost types from before they were renovated still live there?

The greenhouses are a joint project between us and the university actually. Because there's an usual amount of Yerette's energy on Sanctuary grounds, the university’s agriculture faculty funded the greenhouses and we maintain them. Over there we've got experimental cultivars of local plants, mostly fruit trees. Mangos, Plums, Pommecythere, Zaboca (Avacados for you non-Yerettes), hmm Pomerac, Breadfruit for sure, and of course some special Cocoa plants in there, separate from the crop.

Our grass type expert, Moni, maintains them and has a whole crew of assistants, usually post-grad students from the university. They monitor how fast the energy can make the plants grow and what the yield is like. They're trying to up production and harvest sizes with a end goal of better food security for the region. It's looking very promising and the wild pokemon tend to stay away from the area so that's a plus.

As for ghost types, we've got tons of them from before renovation and even before the plantation. There's our copse of Yeretten Trevenant led by a very old Trev we've named Clyde (after the mountain). He'll usually keep the rest in line though he's not above some tricks of his own. He’s been here since the cocoa estate days.

We've got Laggie, the Laghoul that roams the land and helps us whenever poachers show up, she’s probably the youngest “old” ghost on the land. She’s at least as old as the region’s independence, her first sighting being noted by the first grounds’ keeper of the land. And of course, our oldest ghost, Midnight the Marabeau who's been protecting the land since before we even know.

Most of the older ghosts tend to keep to themselves but we do have the one or two oddballs. Josie a Yeretten Yamask for instance, lives in the renovated On-Site quarters. She's a sweetheart but we have to careful when we walk past windows because she loves to knock up against them and scare us. We think she was either belonged to, or was related to, the original plantation owner, William Merton.

And oh! Can't forget Laj our Yeretten Gardevoir. She may or may not have been the one to scare old William Merton to death, reports on that are inclusive and I’ve never asked her one way or another. If she did though, I don’t think she was wrong to do it.

When Laj isn’t with us, she’ll usually be hanging around with the troop of Misdreavous and Yeretten Mismagius that live further up the mountain. She likes to go singing with them.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

For all the perceived glamour of piracy, its practitioners lived poorly and ate worse. Skirting death, mutiny, and capture left little room for comfort or transformative culinary experience. The greatest names in piracy, wealthy by the day’s standards, ate as one today might on a poorly provisioned camping trip: dried beef, bread, and warm beer. Those of lesser fame were subject to cannibalism and scurvy. The seas were no place for an adventurous appetite.

But when one gifted pirate permitted himself a curiosity for food, he played a pioneering role in spreading ingredients and cuisines. He gave us the words “tortilla,” “soy sauce,” and “breadfruit,” while unknowingly recording the first ever recipe for guacamole. And who better to expose the Western world to the far corners of our planet’s culinary bounty than someone who by necessity made them his hiding places?

British-born William Dampier began a life of piracy in 1679 in Mexico’s Bay of Campeche. Orphaned in his late teens, Dampier set sail for the Caribbean and fell into a twentysomething job scramble. Seeing no future in logging or sugar plantations, he was sucked into the burgeoning realm of New World raiding, beginning what would be the first of his record-breaking three circumnavigations. A prolific diarist, Dampier kept a journal wrapped in a wax-sealed bamboo tube throughout his journeys. During a year-long prison sentence in Spain in 1694, Dampier would convert these notes into a novel that became a bestseller and seminal travelogue.

Parts of A New Voyage Around the World read like a 17th-century episode of No Reservations, with Dampier playing a high-stakes version of Anthony Bourdain. Aside from writing groundbreaking observations on previously un-researched subjects in meteorology, maritime navigation, and zoology, food was a constant throughout his work. He ate with the locals, observing and employing their practices not only to feed himself and his crew but to amass a body of knowledge that would expand European understanding of non-Western cuisine. ********

In the Bay of Panama, Damier wrote of a fruit “as big as a large lemon … [with] skin [like] black bark, and pretty smooth.” Lacking distinct flavor, he wrote, the ripened fruit was “mixed with sugar and lime juice and beaten together [on] a plate.” This was likely the English language’s very first recipe for guacamole. Later, in the Philippines, Dampier noted of young mangoes that locals “cut them in two pieces and pickled them with salt and vinegar, in which they put some cloves of garlic.” This was the English language’s first recipe for mango chutney.

Read more…

1 note

·

View note

Link

In the months before Hurricane Maria hit, Puerto Rico was experiencing an agricultural renaissance. The island territory had long imported the majority of its food, but local farms were booming, sending more produce, coffee, and milk to market than ever before. But by the end of October 2017, more than 80 percent of the island’s crop value had been destroyed, leaving the island’s people not only destitute, but vulnerable as they awaited food shipments from the continental United States.

In many rural areas, just one tree was left standing—breadfruit.

For thousands of years, breadfruit grew in the Pacific Islands, where it was a staple in locals’ diets. Shaped like a dimpled green grapefruit, breadfruit belongs to the fig family and is one of the most productive foods in the world, with a single tree yielding upwards of 150 fruits each season.

As islanders expanded across Oceania, it’s believed they ferried breadfruit plants in boats between low-lying atolls, unsure of what food they would find in their new locales. Spanish voyagers who arrived in the late 1500s documented the prolific plant for the first time in their journals. And in the late 1700s, the British Empire established breadfruit plantations in Caribbean colonies to use as food for slaves, where it gained a notorious reputation. By the mid-20th century, thanks in large part to this association and environmental changes, the fruit was falling out of favor, with large agroforests of breadfruit disappearing entirely.

[Continue Reading]

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

one metre of calico, 5 shades of green 100% cotton colourfast thread, 3 plants converging in the Caribbean for the purposes of the expansion of Empire, enrichment of the British Monarchy, the development of a very modern England, especially London, the creation of an extremely at risk Caribbean with climate crisis because of plantationocene, (nature never intended for plantation agriculture, enslavement and plantation created a very vulnerable region highly susceptible to climate disasters) economic scarcity, cultural devastation as coloniality still tells us we're no good and never will be. The Caribbean remains a scene of continual extraction and exploitation. This work was developed during the residency. It will be completed hand embroidered (so you already know, this might be finished some months from now when i am back in Belize) #plantationocene #handembroidery #wrappedbackstitch #colonialism #breadfruit #sugarcane #plantain #wip id: calico fabric in a bamboo embroidery hoop, drawing of a breadfruit blossom embroidered with green cotton thread (at Gasworks) https://www.instagram.com/p/CbfHVFQtoGB/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

Kiribati, officially Republic of Kiribati, island country in the central Pacific Ocean. The 33 islands of Kiribati, of which only 20 are inhabited, are scattered over a vast area of ocean. Kiribati extends 1,800 miles (2,900 km) eastward from the 16 Gilbert Islands, where the population is concentrated, to the Line Islands, of which 3 are inhabited. In between lie the islands of the Phoenix group, which have no permanent population. Total land area is 313 square miles (811 square km).

The capital and government centres are at Ambo, Bairiki, and Betio, all islets of South Tarawa in the northern Gilberts. Kiribati and Tuvalu were formerly joined as the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony. The name Kiribati is the local rendition of Gilberts in the Gilbertese, or I-Kiribati, language, which has 13 sounds; ti is pronounced /s/ or like the word see—thus Kiribati, pronounced “Ki-ri-bas.”

A few of the islands are compact with fringing reefs, but most are atolls. The largest atoll (and one of the largest in the world) is Kiritimati (Christmas) Atoll in the Line group, which has a land area of 150 square miles (388 square km) and accounts for almost half of the country’s total area. Kiritimati was used for U.S. and British nuclear weapons testing in the 1960s; it now has a large coconut plantation and fish farms as well as several satellite telemetry stations. Banaba reaches 285 feet (87 metres) above sea level, the highest point in Kiribati. Its rich layer of phosphate was exhausted by mining from 1900 to 1979, and it is now sparsely inhabited. The rest of the atolls rise no higher than some 26 feet (8 metres), making them vulnerable to changes in ocean surface levels. By 1999 two unpopulated islets had been covered by the sea; the threat of rising sea levels, a theoretical result of global warming, would be disastrous for the islands of Kiribati. Average precipitation in the Gilbert group ranges from 120 inches (3,000 mm) in the north to 40 inches (1,000 mm) in the south, though all of the islands experience periodic droughts. Most rain falls in the season of westerly winds, from November through March; from April to October, northeast trade winds prevail.

Coconut palms dominate the landscape on each island. Together with the products of the reef and the ocean, coconuts are the major contributors to village diet—not only the nuts themselves but also the sap. The gathered sap, or toddy, is used in cooking and as a sweet beverage; fermented, it becomes an intoxicating drink. Breadfruit and pandanus also are grown. Cyrtosperma chamissonis, a coarse tarolike plant, can be cultivated in pits, but plants such as taro, bananas, and sweet potatoes are scarce. Pigs and chickens are raised.

The people are Micronesian, and the vast majority speak Gilbertese (or I-Kiribati). English, which is the official language, is also widely spoken, especially on Tarawa. More than half of the population is Roman Catholic, and most of the rest is Kiribati Protestant (Congregational). There are small minorities of Mormon and Bahāʾī followers.

For many years the population of most islands has remained fairly static because of migration to the rapidly growing urban centres of South Tarawa, where more than two-fifths of the population lives. South Tarawa, including Betio, the port and commercial centre of Tarawa, has an extremely high population density. Most people live in single-story accommodations. The rural population of Kiribati lives in villages dominated by Western-style churches and large open-sided thatched meetinghouses. Houses of Western-style construction are seen on outer islands and are common on Tarawa.

Until 1979, when Banaba’s deposit of phosphate rock was exhausted, Kiribati’s economy depended heavily on the export of that mineral. Before the cessation of mining, a large reserve fund was accumulated; the interest now contributes to government revenue. Other revenue earners are copra, mostly produced in the village economy, and license fees from foreign fishing fleets, including a special tuna-fishing agreement with the European Union. Commercial seaweed farming has become an important economic activity.

An Exclusive Economic Zone of 1,350,000 square miles (3,500,000 square km) is claimed. A small manufacturing sector produces clothing, furniture, and beverages for domestic consumption and sea salt for export. The country’s proximity to the Equator makes it a desirable location for satellite telemetry and spacecraft-launching facilities; several national and transnational space authorities have built or have proposed building facilities on the islands or in surrounding waters. Such projects bring capital, additional employment, and infrastructure improvements, but Kiribati continues to depend on foreign aid for most capital and development expenditure. Food accounts for about one-third of all imports, most of which come from Australia, Japan, and Singapore; Japan and Thailand are the major export destinations. Although South Tarawa has an extensive wage economy, most of the people living on outer islands are subsistence farmers with small incomes from copra, fishing, or handicrafts. These are supplemented by remittances from relatives working elsewhere. Interisland shipping is provided by the government, and most islands are linked by a domestic air service. Tarawa and Kiritimati have major airports.

Finally, I will leave a link which includes all companies and enterprises in Kiribati, for those who want to research and discover more about this country. Thanks for reading.

All businesses address in Kiribati: https://findsun.net/KI

0 notes