#bosnian croatian serbian literature

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The growing TBR Pile : 2024 edition

I'm not a fast reader. Case in point : Storygraph has me pinned as someone reading a book in... 2 months. I say this is slander. I think. I'm not sure. There might be some truth somewhere. But I consume a lot of content either via YouTube or Tumblr about books.

The consequences are dire : my TBR pile grows and grows! So here are some of my 2024 discoveries that I want to read (at some point, I don't know when exactly, it's difficult to say - but it will happen?).

First stop : Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian literature.

At the beginning of the year, I happened on a very short article (in an otherwise very dense newspaper) listing some of the latest translations by a single translator of BCS language. She mentioned the similarities and differences between all those languages, leading me to read more and more about her work and those languages. It made me quite curious about translated literature from that region and ended up compiling a few of them.

Source : interview in French of Chloe Billon, the translator in question, in Pages Sauvages.

Na Drini ćuprija - The Bridge over the Drina -, Ivo Andrić (1945)

The town of Visegrad was long caught between the warring Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires, but its sixteenth-century bridge survived unscathed--until 1914 when tensions in the Balkans triggered the first World War. Spanning generations, nationalities, and creeds, The Bridge on the Drina brilliantly illuminates a succession of lives that swirl around the majestic stone arches. Among them is that of the bridge's builder, a Serb kidnapped as a boy by the Ottomans; years later, as the empire's Grand Vezir, he decides to construct a bridge at the spot where he was parted from his mother. A workman named Radisav tries to hinder the construction, with horrific consequences. Later, the beautiful young Fata climbs the bridge's parapet to escape an arranged marriage, and, later still, an inveterate gambler named Milan risks everything on it in one final game with the devil.

Adios, Comboy, Olja Savičević Ivančević (2011)

Dada’s life is at a standstill in Zagreb—she’s sleeping with a married man, working a dead-end job, and even the parties have started to feel exhausting. So when her sister calls her back home to help with their aging mother, she doesn’t hesitate to leave the city behind. But she arrives to find her mother hoarding pills, her sister chain-smoking, her long-dead father’s shoes still lined up on the steps, and the cowboy posters of her younger brother Daniel (who threw himself under a train four years ago) still on the walls.Hoping to free her family from the grip of the past, Dada vows to unravel the mystery of Daniel’s final days.

Second Stop : Polish literature

I learned a lot this past year about Poland (for personal reasons). I started reading about the history of the country, the language, its culture etc. I was at first quite ashamed to be so oblivious to another country from which quite a few of my friends's family come from, and with which French history is so closely linked. Obviously, I started piling up some polish writers in my TBR as a result.

Bezrobotny Lucyfer - Lucifer Unemployed -, Aleksander Wat (1927)

In these nine stories the Polish writer Aleksander Wat consistently turns history on its ear in comic reversals reverberating with futurist rhythms and the gently mocking humor of despair. Wat inverts the conventions of religion, politics, and culture to fantastic effect, illuminating the anarchic conditions of existence in interwar Europe. The title story finds a superbly ironic Lucifer wandering the Europe of the late 1920s in search of a mission: what impact can a devil have in a godless time? What is his sorcery in a society far more diablical than the devil himself? Too idealistic for a world full of modern cruelties, the unemployable Lucifer finally finds the only means of guaranteed immortality. In "The Eternally Wandering Jew," steady Jewish conversion to Christianity results in Nathan the Talmudist reigning as Pope Urban IX. The hilarious satire on power, "Kings in Exile," unfolds with the dethroned monarchs of Europe meeting to found their own republic in an uninhabited island in the Indian Ocean.

Third and Final Stop : under the Influence

I used to watch TikTok at some point, and most of the content left me frustrated, with a hint of dissatisfaction. But sometimes, sometimes, I happened on a great content creator, full of enthusiasm, or a very very avid reader sharing their love for one book. This, unfortunately, doesn't leave me unbothered. And I do admit, witnessing the passion of someone else about a book, made me want to dive into the novels myself !

Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas - The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas -, Machado de Assis (1881)

Machado de Assis is not only Brazil's most celebrated writer but also a writer of world stature. In his masterpiece, the 1881 novel The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas (also translated as Epitaph of a Small Winner), the ghost of a decadent and disagreeable aristocrat decides to write his memoir. He dedicates it to the worms gnawing at his corpse and tells of his failed romances and half-hearted political ambitions, serves up hare-brained philosophies and complains with gusto from the depths of his grave. Wildly imaginative, wickedly witty and ahead of its time, the novel has been compared to works by Cervantes, Sterne, Joyce, Nabokov, Borges and Calvino, and has influenced generations of writers around the world.

The Safekeep, Yael van der Wouden (2024)

It is 1961 and the rural Dutch province of Overijssel is quiet. Bomb craters have been filled, buildings reconstructed, and the war is truly over. Living alone in her late mother’s country home, Isabel knows her life is as it should be—led by routine and discipline. But all is upended when her brother Louis brings his graceless new girlfriend Eva, leaving her at Isabel’s doorstep as a guest, to stay for the season. Eva is Isabel’s antithesis: she sleeps late, walks loudly through the house, and touches things she shouldn’t. In response, Isabel develops a fury-fueled obsession, and when things start disappearing around the house—a spoon, a knife, a bowl—Isabel’s suspicions begin to spiral. In the sweltering peak of summer, Isabel’s paranoia gives way to infatuation—leading to a discovery that unravels all Isabel has ever known. The war might not be well and truly over after all, and neither Eva—nor the house in which they live—are what they seem.

#saintsaens reads 2024 edition#tbr pile#tbr list#books#bosnian croatian serbian literature#(is there a tag that relates to them ???)#polish literature#brasilian literature#classic literature

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In 1941, after a dramatic turn of events, both outside and inside the country, Croatia proclaimed independence, becoming a puppet state of the German Third Reich. The Independent State of Croatia (NDH – Nezavisna Drzava Hrvatska) was born. Almost immediately, racial laws were introduced. Fritz (my grandfather) had just come back from his travels abroad when the new law forced him to return to the town of his birth in order to register as a Jew and get a yellow star on his sleeve. His sisters who stayed in Bosnia were in hiding. Both of them had married Serbs because, even with Serbs being hated and persecuted, it was still better to be a Serb than a Jew.

“It’s still better to be a Serb than a Jew” – I would hear that same exact sentence from a Hungarian consul in London in 1993, while we were applying for a visa. The consul meant it as a joke. But my husband and I, people with no country or passport at the time, did not laugh. We could not understand how this man had managed to identify us as a Serb and a Jew respectively, although we ourselves had never mentioned those facts and our travel documents did not hold that information. Are all racists of this world connected in some unknown, mysterious way? Do they know facts about us that even we don’t know?

Fritz was torn. He had an invitation to emigrate to Israel. My mother would mourn his refusal to take that offer throughout her whole life. Why didn’t he leave? He was a fairly well-known figure in Zagreb. One of his best friends was Bozidar Adzija, a respected leftist writer and politician. A street in Zagreb bore his name until the right wing Tudjman government changed it in the nineties.

This group of young people was infected by progressive ideas about a world without nationalism and religious sectarianism. Fleeing to Israel must have seemed like giving up on those ideas. It meant seeking refuge with your own tribe and thus denouncing the idea of being a citizen of the world. At least I presume that was one of the reasons to stay. There was also the well known human habit of refusing to believe the worst could ever happen. Also, finding solace in the word of the law, even if that law seems wrong (If I obey the law, they would not hurt me, would they? The answer is: yes, they would.)

Fritz obediently returned to his town of Bijeljina and registered as a Jew. He went searching for his sisters who chased him away: he was a danger to them. They were hiding in a Serbian Orthodox church where the authorities didn’t dare to touch them. They both took their husbands’ Serbian names. They didn’t want to risk capture because of their brother. Later on, in discussions with my Jewish family in Belgrade, I would always detect an animosity towards Fritz: how dared he endanger the family? Fritz was on his own, without protection from anyone. He was immediately captured by the Bosnian pro-Nazi Muslim police and transferred to the Croatian Ustashas. And that’s how he found himself in Jasenovac concentration camp.

That beautiful, soft, elegant, educated man was now digging mud from the smelly ditch surrounding the camp, at the mercy of enthusiastic killers. It wouldn’t last long. How old was he when he died? I could never find out. He had disappeared without a trace. Branka spent the war in Zagreb, under the strict antisemitic laws, studying French and Yugoslav literature at the university. She would hide from all the horror behind books. They were saving her life. On the practical front, she started using her biological mother’s name, Savić, because – as I said before – in that time and that place it was still better to be a Serb than a Jew. But what really protected her during the Nazi years in Croatia was her adoptive mother, Ljuba.”

- Mira Furlan, Love Me More Than Anything In the World

#mira furlan#book excerpt#this book is definitely not a light hearted read#this pretty much sets the tone

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Absolutely sick how your own country successfully committed ethnic cleansing in your own living memory and you have nothing to say about it. The primary reason you care about I/P is it allows you to hate Jews openly, on the world scale it's actually a very minor conflict.

Jfc i do care about the first part and i talk about it and i talked about it. If you mean bosnia and in the latter part of the war ethnic cleansing of serbian people. I am croatian and was a baby when this happened, just to clarify it. And my own ethnic background is complex. Grandmother from my bio father’s side was bosnian muslim, my grandfather from my mother’s side was muslim montenegrin. i did talk about in the past. About the war and my own family past. I am upset at these accusations and I am trying to answer this as calmly as I can. No I/P is not a minor conflict nor is it an excuse to hate jewish people as israel the state is not a representative of the jewish population. I have no idea who you are but you obviously follow me elsewhere too. So if you want we can talk this out with relevant literature and experiences brought. I am heartbroken daily. This is not impersonal to me.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Langblr Reactivation Challenge

Week 1 - Day 2 - Goals

Spanish

add as source language

regain confidence speaking

read more Spanish books I own (especially Don Quixote)

watch el ministerio del tiempo

re-read grammar workbook

Romanian

add as source language

read poetry collection and Dracula copy

Finish Teach Yourself

Finish Duolingo course

Yiddish

read classic literature (especially Tevye and Dybbuk)

talk to a native speaker

Finish Colloquial and In Eynem

Finish Duolingo course

Croatian

add as (potential) source language

Finish Teach Yourself

learn more about differences to Serbian, Bosnian and Montenegrin

learn alphabet/pronunciation

Korean

be able to do small talk

be able to order food at Korean restaurant

settle on textbook

finish learning writing system/pronunciation

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

5, 11 and 14 for the ask thing 😌

The ask thing in question

Thanks for the questions! <3

So, I'm a bit of a cheater because I'm Serbian and will probably be choosing Croatian, Bosnian, Montenegrin bits of media as well. Our languages are completely mutually intelligible so I don't care 😎 (also: *is a sucker for Yugonostalgia*, bratstvo i jedinstvo etc.)

5) Favourite song in your native language?

I'm a huge Azra fan so my faves by them include: Ako znaš bilo što; 2.30; Čudne navike; Pit... i to je Amerika; Krvava Meri; Hladni prsti; Balkan; Gracija; Užas je moja furka; Proljeće je 13. u decembru; 3N; (I'm just gonna stop here)

Darko Rundek - Apokalipso; Ruke; Makedo

Miladin Šobić - Đon; Ne pokušavaj mjenjat me; Prođoh gradom; Od druga do druga

From VIS Idoli - Moja si; Maljčiki; Odbrana & Nemo

I'd also recommend the following bands - Dobri Isak, Šarlo Akrobata (one of my favourite bands actually), EKV & Haustor

There are many others, but I'll leave it here for the sake of y'all.

11) Favourite native writer/poet?

Oof, reluctant to admit but I don't read a lot of literature written by native authors (trying to turn this round though!)

Poet - Branko Miljković hands down

Writer - Ivo Andrić (for his short stories and "The Bridge on the Drina" i.e. "Na Drini ćuprija") and Meša Selimović (for "Death and the the Dervish" i.e. "Derviš i smrt")

14) Do you enjoy your country’s cinema and/or TV?

Current state of affairs - Nope. Our TV shows are mass produced, cheap insipid telenovelas.

I do enjoy our cinema of yore though - Profesionalac; Maratonci Trče Počasni Krug (The Marathon Family); Balkanski Špijun are all a great start for getting into Yugo-cinema. I'd be glad to recommend some more

#asks#ask game#“my quotation marks are inconsistent throughout pardon me I'm studying for an exam and dying”#but I'm not really studying now am I?#alas that is the fate of a procrastinating student#answer

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction The Serbs (Serbian: Срби, romanized: Srbi, pronounced [sr̩̂bi]) are a South Slavic ethnic group native to Southeastern Europe who shares a common Serbian ancestry, tradition, historical past, and language. They primarily dwell in Serbia, Kosovo, Bosnia, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Slovenia, Germany, and Austria. In addition, they represent an extensive diaspora with several communities throughout Europe, the Americas, and Oceania. Historical past The Serbs are among the oldest Slavic peoples, whose historical past might be retraced to the sixth century. They first settled in the Balkans in the seventh century, and over the centuries, they performed a significant function within the area's historical past. The Serbs have a wealthy tradition and heritage; their language is likely one of the most generally spoken in Southeastern Europe. Tradition Serbian tradition is a rich and numerous mixture of Slavic, Byzantine, and Ottoman influences. The Serbs are identified for their hospitality, love of music and dance, and robust sense of nationwide id. Serbian delicacies can be famed for their hearty dishes, resembling pljeskavica (a grilled minced meat patty), ćevapi (grilled minced meat sausages), and gibanica (a layered cheese pie). Language The Serbian is a South Slavic language spoken by around 12 million people worldwide. It's intently associated with the Croatian, Bosnian, and Montenegrin languages; these four languages are also known as Serbo-Croatian. Serbian is written within the Cyrillic alphabet, an extremely inflected language with a fancy system of noun circumstances. Faith Most Serbs are Japanese Orthodox Christians, and the Serbian Orthodox Church is Serbia's biggest non secular denomination. The Serbian Orthodox Church has an extended and wealthy historical past and considerably grown Serbian tradition and society. Demographics Round 12 million Serbs worldwide, of whom about 7 million dwell in Serbia. There are additionally critical Serbian populations in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Slovenia, Germany, and Austria. Notable Serbs Many notable Serbs have made essential contributions to the world in various fields, including science, artwork, literature, music, and sports. A number of the most well-known Serbs embrace: Nikola Tesla, a Serbian-American inventor, and engineer, is taken account to be one of the influential figures in the historical past of electrical energy Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, a Serbian philologist and linguist who's credited with standardizing the Serbian language Jovan Jovanović Zmaj, a Serbian poet and youngsters writer Petar I Petrović Njegoš, a Montenegrin prince-bishop and poet who is taken into account to be the best Montenegrin poet of all time Novak Djokovic, a Serbian skilled tennis participant who's extensively thought of to be one of many most significant tennis gamers of all time Conclusion The Serbs are proud and resilient folks with a wealthy historical past and tradition. They've made significant contributions to the world in varied fields and proceeded to play an essential function in the growth of Southeastern Europe. FAQs What's the capital of Serbia? The capital of Serbia is Belgrade. What's the official language of Serbia? The official language of Serbia is Serbian. What are the critical religions in Serbia? The most critical religions in Serbia are Japanese Orthodoxy, Islam, and Catholicism. What are a few of the hottest vacation locations in Serbia? A few of Serbia's hottest vacation locations embrace Belgrade, Novi Unhappy, Niš, and the Fruška Gora mountains. What are a few of the most well-known Serbian meals? Some well-known Serbian meals embrace pljeskavica, ćevapi, and gibanica. I hope this text has answered your questions concerning the Serbs.

0 notes

Text

752. Lejla Kalamujic

Lejla Kalamujic is the author of the novel-in-stories Call Me Esteban, available from Sandorf Passage. Translated by Jennifer Zoble.

Kalamujic is an award-winning queer writer from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Call Me Esteban received the Edo Budisa literary award in 2016 and it was the Bosnian-Herzegovinian nominee for the European Union Prize for Literature in the same year.

Jennifer Zoble translates Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian- and Spanish-language literature. Her translation of Mars by Asja Bakic (Feminist Press, 2019) was selected by Publishers Weekly for the fiction list in its "Best Books 2019" issue. She contributed to the Belgrade Noir anthology (Akashic Books, 2020), and her work has been published in McSweeney's, Lit Hub, Words Without Borders, Washington Square, The Iowa Review, and The Baffler, among others. She's a clinical associate professor in the interdisciplinary Liberal Studies program at NYU.

***

Otherppl with Brad Listi is a weekly literary podcast featuring in-depth interviews with today's leading writers.

Launched in 2011. Books. Literature. Writing. Publishing. Authors. Screenwriters. Etc.

Available where podcasts are available: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, iHeart Radio, etc.

Subscribe to Brad Listi’s email newsletter.

Support the show on Patreon

Merch

@otherppl

Instagram

YouTube

Email the show: letters [at] otherppl [dot] com

The podcast is a proud affiliate partner of Bookshop, working to support local, independent bookstores.

www.otherppl.com

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi ✨ In regards to a recent post of urs stating that Urdu/Hindi aren’t different, I wanted to let you know that the two are admittedly quite different. Although both are derived from Hindustaani, Hindi (due to being spoken primarily by Hindus prior to the division of South Asia) contains more sanskrit (the text used in Hindu holy books) whereas urdu has more Classical Arabic (the text used in the Quran as this language was often spoken by Muslims of the area) & Persian Muslims who (1/3)

conquered the area at a time) influences. The differences are more profound in their respective literature. Not to mention, there are mild differences in pronunciation & the scripts are entirely different. They are some overlaps due to the speakers interacting or being neighbors. However, by suggesting the two languages are essentially the same negates their complexity and their historically rich culture. Although a urdu speaker might understand some Hindi & vice versa, it typically (2/3)

occurs on a basic surface level. In other words, it might be difficult to use more elevated language or vocabulary. It is better to get insight on such languages from native speakers rather than relying on linguists who are confined to an outsider view of the language and it’s culture and history. I hope this made sense- take care 🌷✨ (3/3)

---------------------------------------------------

This is the same with Malay/Indonesian or Bosnian/Serbian/Croatian. There are strong extralinguistic (historical, cultural, political) reasons to treat these as separate entities, the linguistic reasons, however, are much less compelling.

cf Wikipedia

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet the New Class!

It is our pleasure to announce the 17 writers who will join our UNLV community this coming Fall 2019 semester! Congratulations to everyone, and welcome to Vegas!

PHD/BLACK MOUNTAIN INSTITUTE FELLOWS

Robert Ren is a writer and teacher in New York. He has a BA from the University of Chicago and an MFA from Columbia University. Having escaped a corporate career, he currently tutors kids in standardized test prep. He managed to avoid the whole college admissions scandal, but that's only because his photoshop skills are terrible.

Dorothy Solomon (not pictured)

MFA Fiction

Bronwyn Scott-McCharen was born and raised in Jackson, Mississippi and graduated from Hendrix College in 2014 with a degree in Sociology and Anthropology. She then lived in Buenos Aires, Argentina for three years, where she immersed herself in the country's vibrant political culture under the guise of academic research. Her interests outside of writing fiction include travel, photography, international politics and history (especially Cold War history). She is currently hard at work on two novels in distinct stages of development--one completed manuscript in need of polish and another in the earliest phase of drafting and intensive research. She speaks Spanish and Brazilian Portuguese and hopes to soon add Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian to her budding repertoire of languages.

Mir Arif developed the idea of storytelling at an early age from strangers—astrologers, street magicians, herbal medicine sellers and other con-artists—frequenting the quiet alleys of his childhood neighborhood in Comilla, a small town in southern Bangladesh. He graduated from University of Dhaka with a degree in International Relations and worked as a staff writer for Arts & Letters. His short stories have appeared in various magazines and e-zines in the US, Singapore, India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. One of his short stories was longlisted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize 2019. He likes to hike and spend time with parakeets.

Karen Gu's fiction has appeared in Paper Darts and The Margins and is forthcoming in McSweeney's Quarterly. She has been awarded fellowships from Kundiman, the Jack Jones Literary Arts Retreat, and the Loft Literary Center. After five years in Chicago and four years in Minneapolis, she is looking forward to the desert.

Mohammed Jahama often introduces himself as Mo. He likes to write about those kinds of borderland identities and to talk about words. And is excited and grateful for the opportunity to do such things at UNLV.

Sylvia Fox has too many interests and a wandering soul, which is why she writes fiction. Most recently, she spent the last two years in Baltimore, MD, surrounded and inspired by artists. So many aspects of her identity have led her to believe in the subversive power of showing up, taking up space, and creating space for others. She looks forward to continuing to explore this in writing and in community with others.

MFA Poetry

Nick Barnette, an Alabama native, attended Texas Christian University where he received a BA in English and BS in Film-Television-and-Digital Media. Upon graduation, Nick received a Fulbright Fellowship to Greece where he taught ESL in an elementary school in Athens.

Sarah Spaulding is a Tennessee native and a lover of the mountains that raised her. She graduated summa cum laude with her BA in psychology and English with an emphasis in creative writing from Carson-Newman University. There she discovered her penchant for digging around in people’s heads. She often writes poems to dig herself out of her own head. Her work appears in Tennessee’s Best Emerging Poets, Aletheia, Ampersand, The Sigma Tau Delta Rectangle, and soon-to-be a guide to Southwestern Iceland. When she’s not busy exploring the mire of humanity, Sarah enjoys dancing in the sunshine, petting other people’s dogs, and helping her father type his memoir.

Jo O’Lone-Hahn is from rural Pennsylvania, and is now on her way to Las Vegas, continuing on her lifelong mission to see the world. She has a B.A. in poetry, studio art, and religious studies from Hampshire College. She writes poems that focus on misunderstood people, naiveté, and the imagination inherent in remembering. Jo has held jobs such as: social worker, tattoo-shop-front-desk-chick, archivist, and tarot-reader-on-the-streets. She is also a member of the Departure Collective, a literary group which conducts workshops, organizes poetry readings, and creates chapbooks. When she’s not writing, she makes mixed-media artworks, wanders around, and befriends grumpy old men.

Nicholas Gruber is a native of Wisconsin, where he earned a BA in Economics from UW-Milwaukee. He is an emerging poet, and--hand to God--a human.

Kathryn McKenzie is a Las Vegas native with a BA in English. She drinks enough tea to match the annual consumption of the entire country of Ireland, and prefers snuggling up in her reading chair with a book, toast, and tea to almost anything in the world. Beyond her deep love of poetry and literature, her passions include: asking to pet every dog she sees, cracking her back after standing up in the movie theater, planning Halloween costumes years in advance, and talking about all the parties she is going to throw, but never actually throwing them. Her poetry has appeared in Neon Dreams and Unincorporated, and her interest in publishing has led her to work with Interim, Witness, and Helen: a literary magazine.

MFA Nonfiction

Christina Berke is a Libra and a teacher from Los Angeles.

Jordon Smith, raised among the Tetons in Wyoming, is a nonfiction writer who enjoys the pleasures and curiosities of the natural world. She completed her undergraduate degree at Utah State University where she met her husband. After graduating, she and her husband moved to Oklahoma where they welcomed a baby boy. Jordon discovered a love of distance running during her time in Oklahoma and is currently training for a marathon in July. When she is not running, she is working in the public library, taking long car rides, or watching children's television shows.

At first look, Soni Brown's life is a series of parodies. She is an immigrant who planned and spent her first vacation in Dubuque, Iowa in January; a former flight attendant afraid of heights and a classically trained chef who prefers Stouffer's frozen meals. As a nonfiction writer, Soni uses her journalism training to write about women, immigrants, and the vagaries of life. A wife and mom since 2016, she is constantly trying to have it all especially a partner who picks up after himself. At the end of the world, you will find Soni nursing a tumbler of herby gin while recounting the year she spent in Brooklyn with Jay-Z. So what if he doesn't know her.

Alyse Burnside: I am a writer and educator currently living in Minneapolis, Minnesota. I received by B.A in English and Gender Studies from the University of Iowa. While I consider myself primarily an essayist, I am interested in working between the confines of genre, combining poetry, narrative, and speculative nonfiction. I am currently working on a collage project of interviews with spiritualists, metaphysical myth, and the neuroscience behind how one creates their own reality. When I’m not writing or working, I am reading, traveling, or watching reality T.V. I am thrilled to be attending UNLV in the fall and am excited to meet the desert for the very first time.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books, Clitics in the wild

This collective monograph is the first data-oriented, empirical in-depth study of the system of clitics on Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian. It fills the gap between the theoretical and normative literature by including solid data on variation found in dialects and spoken language and obtained from massive Web Corpora and speakers’ acceptability judgements. The authors investigate three primary sources of variation: inventory, placement and morphonological processes. A separate part of the book is http://dlvr.it/SgNvcn

0 notes

Photo

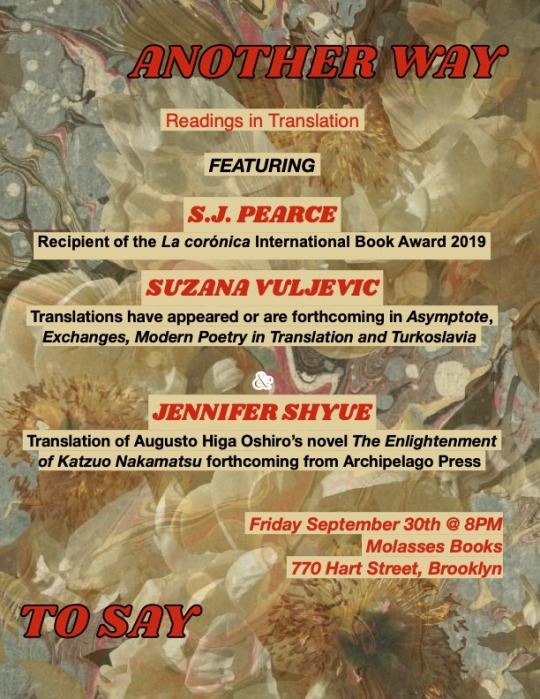

We're ringing out National Translation Month at Molasses Books, September 3oth at 8PM, with an incredible trio of translators-writers. Plugging Asymptote hard here to direct you to both S.J. Pearce's new translation(s) of Psalm 9 that reveals the psalm's many-voiced awe and resentment, and a selection of Suzana Vuljevic's translation of "Airplane Without an Engine" by Ljubomir Micić with a white sharp "Hellooooooooooooooooooo / I leap headlong into my ideoplan". If you had the good fortune to attend Us&Them's November 2021 reading, you'll remember Jennifer Shyue, whose translations of Julia Wong Kcomt's poetry has been published by Ugly Duckling Presse's Señal series as Vice-Royal-ties.

*** S.J. Pearce is a writer and translator who lives in New York City. Her poetry has appeared in The Laurel Review, The Reform Jewish Quarterly, Orotone, and Second Chance Lit, as well as in the anthology Strange Fire (Teaneck, 2021); she has also work forthcoming in Asymptote and The Plenitudes. Her first chapbook manuscript was a finalist for the Laurel Review's 2021 Midwest Chapbook Competition and she was long-listed for the 2021 River Heron Review Poetry Prize. She is a member of the 2022 cohort of the Brooklyn Poets Mentorship Program. In the scholarly realm, she publishes on the history of translation in the medieval Mediterranean world. Her first academic monograph was the recipient of the 2019 La Corónica International Book Award. Suzana Vuljevic is a historian, writer and translator who works from Albanian and Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian. Suzana holds a Ph.D. in History and Comparative Literature from Columbia University. Her writing and translations have appeared in Zenithism (1921–1927): A Yugoslav Avant-Garde Anthology (Academic Studies Press, 2022), AGNI, Asymptote, Eurozine, Exchanges, and elsewhere. She is a 2022 ALTA Travel Fellow and an editor at EuropeNow. & Jennifer Shyue is a translator from Spanish and an assistant editor at New Vessel Press. Her work has appeared most recently in AGNI, Astra Magazine, and Poetry Daily. Her translations include Julia Wong Kcomt’s chapbook Vice-royal-ties (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021) and Augusto Higa Oshiro’s novel The Enlightenment of Katzuo Nakamatsu (Archipelago Books, 2023). She can be found at shyue.co. *** THROUGHOUT THE REST OF SEPTEMBER Trafika Europe Radio's programming will feature international authors and works in translation from the likes of Thora Hjörleifsdóttir with translator Meg Matich, Victor Jestin with translator Sam Taylor, Italian poet and novelist Daniele Mencarelli, and more!

MONDAY SEPTEMBER 19 at Greenlight Bookstore's Fort Greene location, Emma Ramadan presents her translation of Barbara Molinard's Panics in conversation with Kate Zambreno SUNDAY SEPTEMBER 25th at the Parkside Lounge, the Spoken Word Sunday Series presents a special event for National Translation Month featuring Soodabeh Saeidnia and Adriana Scopino.

TUESDAY SEPTEMBER 27th in the virtual realm, Words Without Borders presents World in Verse: a Reading and Celebration of International Poetry with Najwan Darwish, Kareem James Abu-Zeid, Samira Negrouche, Marilyn Hacker, Jeannette Clariond, Samantha Schnee

*** Eager to see you in your sweaters and cords! xoxo, Janet

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Resources Master Post

My General Resources Tag (X)

For Your Bujo

My General Bujo Tag (X)

Cute Quotes To Put In Your Bujo (X)

Inspiration (X)

Layout Printables (X)

Printables & Notes

My General Printables Tag (X)

Foreign Language Learning Printables (X)

Calendars (X)

Planners (X)

Misc Printables (X)

Organizational Printables (X)

Note-taking Printables (X)

Ready Written Notes (X)

Flashcards (X)

Power Points (X)

Resources By Subject

Anatomy & Physiology (X)

Architecture (X)

Art (X)

Art History (X)

Astronomy (X)

Botany (X)

Chemistry (X)

Computer Science (X)

Dental (X)

Dietetics & Nutrition (X)

Ecology (X)

Economics (X)

Engineering (X)

General Math (X)

General Sciences (X)

Geometry (X)

Grammar (X)

History (X)

Law (X)

Linguistics (X)

Literature (X)

Marine Biology (X)

Medical (X)

Music (X)

Mythology (X)

Nursing (X)

Organic Chemistry (X)

Physics (X)

Writing (X)

Zoology (X)

Foreign Language Studies

My General Langblr Tag (X)

Afrikaans (X)

Albanian (X)

Alsatian (X)

American Sign Language (X)

Amharic (X)

Antillean Creole (X)

Arabic (X)

Armenian (X)

Avestan (X)

Basque (X)

BCSM (Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian-Montenegrin) (X)

Bemba (X)

Bengali (X)

Bikol (X)

Breton (X)

Bulgarian (X)

Burmese (X)

Cantonese/Chinese/Mandarin (X)

Catalan (X)

Cebuano (X)

Chewa (X)

Corsican (X)

Crioulo (X)

Croatian (X)

Czech (X)

Danish (X)

Dutch (X)

Egyptian Hieroglyphics (X)

English (X)

Esperanto (X)

Estonian (X)

Farsi (X)

Filipino (X)

Finnish (X)

French (X)

Frisian (X)

Fula (X)

Gaelic Scottish (X)

Galician (X)

Georgian (X)

German (X)

Greek (X)

Guarani (X)

Gujarati (X)

Haitian Creole (X)

Hausa (X)

Hawaiian (X)

Hebrew (X)

Hiligaynon (X)

Hindi (X)

Hungarian (X)

Icelandic (X)

Ilokano (X)

Indonesian (X)

Irish (X)

Italian (X)

Ivatan (X)

Japanese (X)

Kabyle (X)

Kanuri (X)

Kazakh (X)

Kirghiz (X)

Korean (X)

Latin (X)

Latvian (X)

Lithuanian (X)

Luganda (X)

Malagasy (X)

Malay (X)

Maltese (X)

Mandinka (X)

Marshallese (X)

Mongolian (X)

Nepali (X)

Norwegian (X)

Occitan (X)

Ojibwe (X)

Old Norse

Panjabi (X)

Papiamentu (X)

Pashto (X)

Persian (X)

Polish (X)

Portuguese (X)

Punjabi (X)

Quebecois French (X)

Quenya (X)

Romani (X)

Romanian (X)

Russian (X)

Samoan (X)

Sanskrit (X)

Scots (X)

Serbian (X)

Sesotho (X)

Setswana (X)

Sinhala (X)

Slovak (X)

Slovene (X)

Spanish (X)

Swahili (X)

Swedish (X)

Swiss German (X)

Tagalog (X)

Tamazight (X)

Tamil (X)

Tashelheet (X)

Thai (X)

Tok Pisin (X)

Toki Pona (X)

Turkish (X)

Turkmen (X)

Twi (X)

Ukrainian (X)

Urdu (X)

Uzbek (X)

Vietnamese (X)

Welsh (X)

Wolof (X)

Xhosa (X)

Yiddish (X)

Yoruba (X)

Zulu (X)

Books & Textbooks

Textbooks (X)

Books (X)

Health & Beauty

My General Beauty Tag (X)

My General Health Tag (X)

Recipes (X)

Makeup & Skin Care (X)

Self-Care (X)

Vegan (X) (I tag this separately as I know some people may not care for/like veganism)

Misc.

My General Misc. Tag (X)

Art & Pictures (X)

Applications (X)

Bands & Musicians (X)

Master Posts (X)

Stationery (X)

Websites (X)

970 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spring 2017 courses from the Slavic Department

Both of these are optional writing credit courses.

RUSS 323 Modern Russian Literature (1917 – present)

5 credits MTWTh 10:30 – 11:20 EEB 003

RUSS 324 Russian Folk Literature in English

5 credits TTh 12:30 – 2:20 BNS 117

Some of these are also optional writing credit courses.

RUSS 120/420 Russia in Pictures: Exploring a Visual Culture

5 credits MTWTh 11:30 – 12:20 EEB 003 (Optional W)

RUSS 220 Banned in the USSR: Issues of Censorship in 20th C Russian Literature

5 credits MW 12:30 – 2:20 PAR 106

RUSS 240/543 Vladimir Nabokov and James Joyce

5 credits WF 12:30 – 2:20 CDH 109 (Optional W)

RUSS 314 Business Russian

5 credits TTh 1:30 – 3:20 THO 235 (Optional W)

RUSS 323 Modern Russian Literature (1917 – present)

5 credits MTWTh 10:30 – 11:20 EEB 003

RUSS 324 Russian Folk Literature in English

5 credits TTh 12:30 – 2:20 BNS 117 (Optional W)

RUSS 320 Revolutionary Cinema: Eisenstein, Vertov, Pudovkin

5 credits TTh 3:20 – 5:30 ROOM TBD

SLAVIC 351 A History of the Slavic Languages

5 credits TTh 12:30 – 2:20 SAV 164

SLAVIC 370 What’s in a Language Name? The Case of Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin and Serbian

5 credits MW 12:30 – 2:20 CMU 228

SLAVIC 423 East European Film

5 credits MW 2:30 – 4:20 ROOM TBD

1 note

·

View note

Link

Dragoslava Barzut (Crvenka, Novi Sad, 1984) is a writer and activist. She received a degree in comparative literature from the School of Philosophy at the University of Novi Sad, Serbia. Her collection of short stories, Zlatni metak (Narodna biblioteka "Jovan Popović" 2008) was awarded the Đura Đukanov prize in 2012. She received the Carver prize in 2011 for the best short story in the region in the “Izvan koridora” competition. Her poetry and prose has been published in a number of anthologies and journals. She edited the anthology Pristojan život: lezbejske kratke priče sa prostora ex Yu (Labris 2012) and was one of the editors of a collection of contemporary poetry from Novi Sad, Nešto je u igri (Centar za novu književnost – Neolit i Kulturni centar Novog Sada 2008). She is the editor of the web portal of Labris (labris.org.rs), a human rights organization that works to eliminate of all forms of violence and discrimination against lesbians and all women in general and to establish a more egalitarian society.

Paula Gordon (Wilmington, Delaware, 1961) translates from Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian into English. She translated the play Otpad by Ljubomir Đurković (Montenegro National Theatre 2003) and is now translating his trilogy of full-length plays, The Greeks. She is working with Bosnian visual artist Nebojša Šerić “Shoba,” translating a selection of his short stories about growing up in Sarajevo in the 1970s and ’80s, his experiences during the war, and his adventures in the art world. She has translated first-person and critical essays for exhibition catalogs and other publications of arts institutions including the Sarajevo Center for Contemporary Art, the Montenegro Mobil Art Foundation, and the Sarajevo Film Festival. By day she is a medical translator and copyeditor of journal articles, government reports, and research grant applications. She worked closely with lexicographer Svetolik P. Djordjević from 2003 through 2014 as editor of his Serbian- and Croatian-English and English-Serbian medical dictionaries (Jordana Publishing 2009; Jordana Publishing 2014).

0 notes

Link

LARB PRESENTS William T. Vollmann’s introduction to Ivo Andrić’s Omer Pasha Latas: Marshal to the Sultan, translated by Celia Hawkesworth and published by NYRB Classics today.

¤

1.

“If we all had the opportunity, courage and strength to transform just a part of our imaginings […] into reality […] it would be immediately clear to the whole world and to ourselves who we are […] and what we are capable of becoming. […] Fortunately, for most of us, that oppor-tunity never arises. […] But if, by some misfortune, it does happen to someone, that someone finds that we are all merciless judges.” This passage from Omer Pasha Latas is a pretty clear summation of the eponymous protagonist, who lives hated and isolated in the prison of his self-made greatness. It also bears, quite sadly, on various pre-and post-Yugoslav nationalisms.

2.

“I once asked him, ‘What do you feel like, a Croat or a Serb?’ ‘You know,’ he replied, ‘I couldn’t tell you myself. I’ve always felt Yugoslav.’”

The questioner was Milovan Djilas, who had fought the Nazis alongside Tito and afterward became a vice president of Yugoslavia. The answerer he described as “lanky and bony […] the career diplomat […] fettered by convention and tact” — thus a certain Dr. Ivo Andrić. In this context, tact may be defined in terms of what we refrain from saying. As it happens, Omer Pasha Latas is a work of brilliant evasion, in which most identities become bafflingly problematic. Who is Omer Pasha? “I couldn’t tell you myself. I’ve always felt Yugoslav.”

3.

“Right from the war’s end,” relates Djilas, “the government was well organized and firmly in the hands of the Communists. […] Yet though the nation’s younger generation was fired with enthusiasm, its working class loyal, and its party strong and self-confident, Yugoslavia remained a divided, grief-stricken land, materially and spiritually ravaged.” In Djilas’s day, these divisions were most conspicuously ideological — although even then questions of nationalism could break through. After Tito’s death, their ethnic character predominated. In 1994, a Serb explained to me how to express them practically: “It’s easy. In my town all you’d have to do would be to go to where some Serb lived and throw in a hand grenade, then shoot some Croats. A small group of professionally trained people could do it. Then you spread the news and arm the survivors.”

4.

“What do you feel like, a Croat or a Serb?” Once upon a time, when there was a Yugoslavia, its language used to be called Serbo-Croatian. Let me simplify: the Serbs were mostly Orthodox, their script Cyrillic, and they felt what has been called “the mystical Russian bond”; the Croats were predominantly Catholic, used the Roman alphabet, and sometimes turned toward Germany. Both of them claimed Ivo Andrić. In the interests of federalism their differences were repressed, both psychologically and politically. (I remember a Dalmatian Croat from 1981 who in a low voice identified himself as “Christian.” He said that he could and did go to church, but that his career suffered accordingly.) At great cost, the Titoists had reconstructed and maintained some kind of Yugoslav identity. That Serbs, Croats, and most other Yugoslavs shared a common language, or at least were presumed to do so, may be readily verified by the titles of prewar dictionaries. Their successor nations have now elevated dialects into new languages — Serbian, Croatian, Bosniak, Slovenian — which remain more or less mutually intelligible, although during the war I once or twice witnessed the solemn charades of nationalists communicating to their ex-countrymen through interpreters. In Yugoslavia, there used to be highway signs in both alphabets; nowadays one frequently finds one orthography or the other spray-painted out by the zealots of ethnic correctness. For that matter, on the back cover of this publisher’s galley of Omer Pasha Latas, you could read a biographical note in evidence of this bifurcation: “Celia Hawkesworth has translated several books from the Serbo-Croatian. […] She taught Serbian and Croatian at University College London for many years…”

5.

Yugoslavia, then, was a failed attempt to unify separate and sometimes conflicting identities. Its 1918 incarnation was the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. In 1945, it became the Federative People’s Republic of Yugoslavia. In both of those names, other Yugoslavs went unmentioned. But the civil war that destroyed the federation was fought in the name of Serbs, Croats, and a third group, whose anguish would haunt the news for years: Bosnian Muslims.

Among the many infamous metonyms — the fall of Vukovar, the massacre at Srebrenica, the rape camps — of this hideously personal conflict, in which neighbors violated each other’s daughters and cut their throats, the siege of Sarajevo remains prominent. When I think of Sarajevo, the Bosnian capital, I, who never got to see it before 1992, remember the double and triple thuds of shellfire, and then rushing down the almost empty streets, acutely conscious of my neck; tall blocks of buildings, so many broken windows; another row of apartments flecked with bullet holes; journalists paying 250 American dollars to fill a gas tank; soldiers laughing and ducking behind their sandbags, kept company by a woman who was grinding coffee by hand. Andrić’s secondary school was here, and most of Omer Pasha Latas is set either here or in other parts of Bosnia. How unquiet was it then? Remember that Sarajevo was the place where World War I began. But the windows were not always broken, and women ground coffee in peacetime as in war. Then as now, one would have felt the overwhelming influence of Bosnian Muslim tradition. And indeed, Omer Pasha Latas is set in the period of Ottoman rule, about which Andrić appears to have felt, to say the least, melancholy.

He did not live to see the civil war. But during World War II, while he novelized in seclusion, other ethnic massacres of comparably sadistic cruelty had stained Bosnia. [1] Did he take a side? “I couldn’t tell you myself. I’ve always felt Yugoslav.”

From 1463 until 1878, Bosnia was a conquered province of the Turkish Empire, during which time, according to the historian Noel Malcolm, “the main basis of hostility was not ethnic or religious but economic: the resentment felt by the members of a mainly (but not exclusively) Christian peasantry towards their Muslim landowners.” In any event, the previous sentence contains two terms that though not ethnic were in the context nonetheless opposed: Christians and Muslims. In the 1990s, I frequently heard Serbs and Croats harp back on what had become the bad old days, referring to Bosnian Muslims as “Turks.” But was that just war propaganda? Even in Andrić’s “A Letter from 1920” we read: “Bosnia is a country of hatred and fear.”

6.

So. “What do you feel like, a Croat or a Serb?” Why did Djilas not ask “a Croat, a Serb, or a Bosnian”? Indeed, Lovett F. Edwards, the translator of Andrić’s most famous book, The Bridge on the Drina, into English, assures us in his foreword to it that the author is “himself a Serb and a Bosnian.” (Incidentally, the title page of my 1977 copy reads: “Translated from the Serbo-Croat.”)

Why was this third sort of Yugoslav so effaced yet so visible in Yugoslavia itself? (In 1992, a Croatian Muslim assured me: “It was only the Serbs trying to dominate us who forced us into one country.”) Why did the ostensibly progressive Djilas call his language Serbian, not Serbo-Croatian? If you ask a group of ex-Yugoslavs about these matters, you will receive a discouraging plenitude of answers. But as you read Omer Pasha Latas, I urge you to keep wondering and guessing, for this novel is a hoard of shining questions.

7.

Ivo Andrić was born on October 10, 1892 — almost exactly a century before the civil war. At this point Bosnia’s overlords were the Austro-Hungarians, whose architecture still colors Sarajevo. His birthplace was Dolac, “now in Yugoslavia” (the latter according to the 1976 edition of my Encyclopaedia Britannica). Or, if you prefer a slightly different dateline, he was “born in Travnik, Bosnia, on 9th October 1892.” That place also figures in his novels. What that region was like during his childhood I, who was never there before 1992, cannot imagine, but an English observer from 1897 has left us the following highly significant remark on Christian-Muslim relations in Bosnia: “It is strange that they should bear so little hatred to their former oppressors, and the explanation lies probably in the fact that they were all of the same race.”

More necessary but insufficient desiderata: He went to school in Sarajevo, and also in Višegrad, the setting of The Bridge on the Drina. From 1919 until 1941, he was a diplomat. He received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1961 and died on March 13, 1975, in Beograd, which was first the capital of Yugoslavia and then the capital of the Serbian Republic. As one post–civil war Serbian edition of his selected short stories complacently remarks, “his Belgrade funeral was attended by 10,000 people.” Back to the Britannica: “It was his native province, with its wealth of ethnic types, that provided the themes and psychological studies to be found in his works.”

In Malcolm’s history of Bosnia, we read that sometime around 1907 to 1910, the young man “presided over” a student group called “the Croat-Serb or Serb-Croat or Yugoslav Progressive Movement.” In name, at least, this hardly sounds Greater Serbian. But neither does it sound Bosniak. Nor does it have an Austro-Hungarian ring. The translator of The Bridge on the Drina writes: “As other gifted students of his race and time, and as his own students in The Bridge on the Drina, he belonged to the National Revolutionary Youth Organization, and experienced the customary cycle of persecution and arrest.” The Britannica works in this episode equally blandly: “His reputation was established with Ex Ponto (1918), a contemplative, lyrical prose work written during his internment by Austro-Hungarian authorities for nationalistic political activities during World War I.” Meanwhile, continuing to claim him as a native son, that Serbian edition of stories recounts the same event thus: “He was imprisoned for three years during World War I for his involvement in the Young Bosnia Movement which was implicated in the assassination of Archduke Franz-Ferdinand in Sarajevo.” I have been told that the archduke’s killer, Gavrilo Princip, yearned for Greater Serbia. Or did he? Princip has also been called a “Slav nationalist,” which may or may not be the same thing. In Sarajevo, the commemoration simply reads: “Here, in this historic spot, Gavrilo Princip was the initiator of Liberty on the day of St. Vitus, the 28th of June, 1914.”

At any rate, Andrić, along with many others, was arrested almost immediately after the assassination and kept on ice until the general amnesty of 1917. Two years later, as I said, he entered the diplomatic service.

In 1924, he received his doctorate in the Austrian city of Graz. (Per Lovett Edwards, “Of a poor artisan family, he made his way largely through his own ability.”) His thesis evaluated “The Development of the Spiritual Life of Bosnia Under the Influence of Turkish Sovereignty.” What conclusions did it come to? The introduction to that 1977 printing of The Bridge on the Drina contents itself by blandly asserting that “the solid and precise information that underlies” the novel “was thus systemically built up through academic study.” But Malcolm’s history of Bosnia (published in 1994) labels the work “an expression of blind prejudice,” in evidence of which we are given this unfortunate sentence: “The influence of Turkish rule in Bosnia was absolutely negative.”

The reporter Fouad Ajami, who visited Yugoslavia’s bleeding ground in the same year, quoted the same sentence in evidence of Andrić’s “great dread of Islam in the Balkans, his allergy to the four centuries of Ottoman rule in Bosnia.” (By then a commander of Sarajevo irregulars had assured me: “They’re only terrorists now. They were Serbs. Now they’re not Serbs. There are no more legitimate Serbs.”) Meanwhile, Ajami compounded the accusation: “He was anxious to cover up his tracks. […] [He] had been ambassador of (Royal) Yugoslavia to the Third Reich at the time of the signing of the Tripartite Pact; and he was there in Vienna in March 1941, when Yugoslavia capitulated and joined the Axis powers.”

8.

The unfairness of blaming Andrić for being Yugoslavia’s representative to Berlin is obvious. Someone had to try, however vainly, to delay or mitigate the forthcoming oppression, when, as Drina’s translator puts it, “Yugoslavia was desperately playing for time, hoping to postpone the invasion of Hitler and at the same time consolidate her forces to resist it when it inevitably came. I recall waiting tensely in Belgrade for Dr. Andrić to return from Berlin, the one sure sign that an invasion was immediate. He came back only a few hours before the first bombs fell on Belgrade.”

I do grant that “he was anxious to cover up his tracks.” Not only had he treated with Berlin; he’d also stood in for the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, whose memory could not but be obnoxious to the Titoists. In 1951, when a certain government-sponsored historical exhibition was about to open, Andrić learned that among other items would be a photograph of the signing of the Tripartite Pact, in which he could be seen “straight and tall, in full dress, in all his majesty,” right behind the Third Reich’s bullying plenipotentiary Joachim von Ribbentrop, who would meet the noose at Nuremberg for his part in Nazi war crimes. (About the pact we read: “Hitler’s bribe [to Yugoslavia] was the offer of Salonika, and it was taken.”) And so the anxious Andrić of 1951 entreated Djilas, “with a bitter, even savage, twist to his lips,” to be cut out of the picture. Djilas picked up the phone, and the army obligingly excised the entire photo. Had the novelist been a fascist collaborator, the Titoists would surely have stood him against a wall. On the contrary, Djilas remarks that in 1945, “I admired Andrić’s steadfast refusal to deal on any terms with Nedrić’s Quisling regime.”

And so I would discount a footnoted rumor, which “may simply have been propaganda,” that in 1944 “several Serbian writers, including Ivo Andrić […] were ready to join the Chetniks in the mountains.” These latter were anticommunist insurgents, who soon decided that Tito’s bunch were worse than the Nazis, with whom they accordingly made local devil’s deals. The Allies withdrew support, and at the end of the war, the Chetniks’ leader was shot in Belgrade. These would not have been comfortable companions for our tactful, cautious, lanky diplomat.

9.

Why those innuendoes against him? Given the complex antipathies of the Balkans, was it enough to be hated that he was a great writer? Did his comment that “the influence of Turkish rule in Bosnia was absolutely negative” sufficiently damn him? Did his novels bear a discernible anti-Muslim taint? Or was there more to criticize?

Some years after saving Andrić from his embarrassment about the Tripartite Pact, Djilas began openly disagreeing with Tito. Having resigned from the party, with prison and loss of civil rights on the horizon, he asked Andrić for a professional reading of his memoir of Montenegrin childhood, Land Without Justice (which, like his better-known Wartime, I strongly recommend). Andrić replied: “It’s awkward for me […] I’m a party member.” One may well infer a trace of ordinary human resentment in the rejected party’s summation: “As far as I know, he never harmed a soul, though I cannot boast of his having done anyone any good either…”

10.

In its entry on Yugoslavia, the 1976 Britannica concludes: “There are […] only two really major contemporary figures: Ivo Andrić, the Nobel Prize winner in 1961, is a prose master — best known for his Bridge on the Drina (1945) — whose works, as the Nobel committee noted, have been characterized by ‘epic force,’ great compassion, and clarity of style. The other is Miroslav Krleža, a satirist whose [works] […] foreshadow the themes of modern existentialism.”

Djilas again: “Andrić liked living and working in peace. […] His [official] greetings and toasts were far more flattering than Krleža’s, precisely because Andrić was an alien fitting himself into a new situation […] Andrić was simply an opportunist — but not a simple opportunist.”

11.

Yes, he must have been an alien, for his characters are conspicuous in their alienage. Consider, for instance, in Drina, the Christian boy from Višegrad who in 1516 was wrested from his parents for the Turkish “tribute of blood,” and thus “changed his way of life, his faith, his name and his country.” In short, he grew into an alien opportunist — and eventually became one of the sultan’s great viziers. All the while he never escaped a “black pain which cut into his breast with that special well-known childhood pang.” And so he brought into being the eponymous bridge on the Drina to serve his lost home at Višegrad.

To be an alien is to live between — and one longish pre–civil war (1974) history of the Habsburg Empire considers that Andrić “represents a bridge between imperial and royal Habsburg and future Yugoslav Bosnia. Although he portrayed the imperial administration of Bosnia with great sensitivity and knowledge, he […] [was] outwardly directed toward Serbia.” It might be equally appropriate to call him inwardly directed toward the Ottoman culture of his childhood. Let us temporarily set aside his hypothetical political sympathies and consider him as the great literary master that he is.

Faulkner could utter foolish provocations about race war, but only an ideologue would therefore dismiss his magnificent novels and stories about the tragically echoing ambiguities of race relations in the Deep South. Indeed, Andrić’s more slender corpus is as complex and subtle as Faulkner’s. To my mind, his supreme achievement is the understated Bosnian Chronicle, but the more crowd-pleasing Drina likewise veils his reductionist “absolutely negative” judgment of the Ottomans in a brilliant-colored web of nuance. Whatever one might think of the long Turkish occupation of Bosnia, with its gifts and cruelties, nuance positively shines in the novel’s central device: the vicissitudes of that vizier’s bridge and the generations it served. “This hard and long building process was for them [the Višegrad people] a foreign task undertaken at another’s expense. Only when, as the fruit of this effort, the great bridge arose, men began to remember details and to embroider the creation of a real, skillfully built and lasting bridge with fabulous tales which they well knew to weave and remember.” No “absolutely negative” here!

12.

But by now it should be clear that Omer Pasha Latas will be no paean to the Ottoman period. In the very first pages, when our eponymous protagonist comes to Sarajevo in 1850 to implement certain moderately progressive reforms at whatever cost to the local Muslim gentry, “The procession […] was truly impressive and intimidating, but somehow overdone. In front of it and behind it, to the right and left of it, stretched the deprivation of a poor harvest and a hungry spring, the bleakness of crooked, puddle-filled alleys, dilapidated eaves and long unpainted houses, the poorly dressed people and their anxious faces.”

But unlike the vizier of Drina, Omer Pasha, who began his life utterly beyond the Ottoman pale, voluntarily defects to the Turkish Empire. Almost right away “he found good, warmhearted people,” and upon their advice he converts to Islam.

As it happens, there was a real “Omer-paša Latas[,] [b]orn Michael Lattas,” whom Malcolm’s history describes as “one of the most effective and intelligent governors [Bosnia] ever had in this last century of Ottoman rule,” and who implemented certain reforms to the benefit of the Christian minority. In Andrić’s portrayal you will find little testimony of his effectiveness, and even less of his arguable benignity. He is, in a word, lost.

If warmhearted people are less in evidence in Omer Pasha than they might be (Andrić specializes in the envious, the jealous, the lovesick, and above all the disappointed), localism and syncretism remain his affectionate obsessions. One of this novel’s many briefly yet elegantly sketched characters is the eastern Bosnian village headman Knez Bogdan Zimonjić, whose massively silent obstinacy holds its own against Omer Pasha’s seduction and threats. The unpleasant Omer Pasha himself (“I will reduce your entire Bosnia to rubble, so no one will know who is a bey and who an aga”) contains multitudes: for instance, the failed father of his Austrian past, his unhappy wife (another former Christian), and the “traitors’ unit” of kindred converts, with whom he operates in exquisitely delineated uneasy dependence.

“Most were despairing vagrants who had lost one homeland and not found another, damaged by life among strangers, with burned bridges behind them […] condemned to being loyal soldiers because they had nowhere to go” — call them fragmentary fictive representations of a certain post-1945 Dr. Ivo Andrić.

And so let me now quote another war reporter, Aleksa Djilas, writing in the gruesome year 1992: “Though he came from a Croatian family in Bosnia” — I pause to remind you of the claim that “Dr. Ivo Andrić is himself a Serb and a Bosnian” — “Andrić considered himself a Yugoslav — a nationality that encompassed identities of all the different Yugoslav groups. […] [He] believed only a general acceptance of such a Yugoslav identity within a common state could put an end to the ancient conflicts among various Yugoslav groups.” Whether or not the last sentence is a stretch, I believe that Andrić’s literary project is indeed the noble one of encompassing all the identities he knew.

13.

Who and what, then, was an Ottoman, a Muslim, an occupier, a person of the third sort? “Knowing that to be a true Turk meant being naturally hard, haughty, basically cold and unyielding,” the fictive Omer Pasha does his best to live up to this stereotype, but one hallmark of Andrić’s genius is that as we read him we keep wondering about the problematic nature of all identities, let alone assumed ones. Consider this telling observation from the viewpoint of the procurer Ahmet Aga: Omer Pasha “was beginning to lose his sense of proportion, to forget not only what was permissible and natural and what was not, but also what he himself really wanted and could do and what he could not.” That goes for most of the novel’s characters, from the man who loses his sanity after a love-inflaming glimpse of a strange woman, to Omer Pasha’s irresolute and undistinguished brother, whom the great man advises to consider suicide.

And so we should read Andrić with due regard for ambiguity and irony. There are Turks and Turkish masks. When the Croatian-born, European-trained painter Karas, having received a commission to paint Omer Pasha, enters the empire, “the first Turkish junior officer who had examined his passport at the border, though barely able to read, had worn […] a cold, repellent mask. […] And it was the same everywhere.” If you like, take such passages as nail-in-the-coffin proofs of (requoting Ajami) this author’s “great dread of Islam in the Balkans.” But Omer Pasha, the strict cold Turk, is not a Turk. And Karas, a non-Muslim failure wherever he goes, takes comfort in bigoted resentment.

14.

In this strange novel there comes no resolution, if only because the book remained unfinished at the time of Andrić’s death; the bitter epiphanies of minor characters shed but glancing flickers upon the impermeable solitude of Omer Pasha himself, who at the end departs for unknown places with us none the wiser as to his mission’s practical accomplishments. How life will devolve for his raging wife, and whether Karas’s portrait ever turned out well, of these and other matters we are left ignorant.

Omer Pasha Latas consists less of sequential chapters than of vignettes, which in Drina would have transformed themselves into tales out of the folk tradition, and even here sometimes blossom into magical realism, as in the case of a certain Kostake Nenishanu, maître d’hotel of Omer Pasha’s entourage, who unavailingly pursues and finally murders a Christian prostitute: “the story of his crime […] spread in different directions and to a different rhythm, to grow and branch out, present everywhere but invisible as an underground stream,” serving the superficially opposed purposes of wish compensation and didactic morality tale — the more so as they diverge from actuality. Not only does this passage give a tolerable idea of Andrić’s art; it also stands in for alienation’s beautiful escapist dreams. The novel’s characters cannot understand each other or even themselves.

One might say, this is surely the human condition … but then new passages hammer away at the Turks, until it grows more difficult to reject Ajami’s interpretation of Andrić’s politics — difficult, but not impossible.

It is hardly unreasonable to see Bosnia, as Andrić did in Omer Pasha, as “a society where there have long been disorder, violence and abuse.” And at times, certainly in the 1990s and the 1940s, maybe in 1850–1851 when the novel is set, “people could be divided,” as he upliftingly put it, “into three groups, unequal in size, but sharing the same wretchedness: prisoners, those who pursued and guarded them and silent, impotent onlookers.” These observations ring true, but not eternal. And so readers must decide for themselves whether or not Omer Pasha Latas contains bigotry. Perhaps the best compliment they could pay it would be to delve into Bosnian history.

15.

As for “that Serb or Croat (take your pick) monstre sacré Ivo Andrić,” (in the words of Danilo Kiš, another great writer from the region) let me leave you with one last assessment from Djilas: “In Andrić’s cautious and quiet reserve there was something hard and unyielding, even bitter, which any threat to the deeper currents of his life would have encountered. […] In his deepest and most creative self, Andrić tried to live outside finite time.” Good communists could hardly approve of that! And indeed, Djilas went on to insist that “somehow, everyone must pay his debt to his times.” However, he ended the sentence as follows, either to soften the disparagement of Andrić or because he was now considering his own darkening situation: “But the wise man thinks his own thoughts and does things his own way.”

Andrić did pay his debt to his times. He wrote about what formed him. His bitterness was sincere, his descriptions beautiful. Meanwhile, like Omer Pasha, he thought his own thoughts, leaving us with haunting sentences and difficult questions.

¤

William T. Vollmann is the author of three collections of stories, more than ten novels, and many more volumes of nonfiction. His novel Europe Central won the National Book Award in 2005, and he has won the Whiting Foundation Award and the Shiva Naipaul Memorial Award for his fiction. In 2018, he published a two-volume investigation into climate change, Carbon Ideologies.

¤

[1] Readers should be warned that my attempt to express narrative continuity in regard to Bosnia’s multiple tragedies may be controversial or even offensive. Many accounts take the position that the Bosnian genocide of the 1990s was a unique event, like the Holocaust, and that it would not have happened without its Serbian instigators. “The biggest obstacle to all understanding of the conflict [in Bosnia of 1992–1993] is the assumption that what has happened […] is the product […] of forces lying within Bosnia’s own internal history. This is the myth which was carefully propagated by those who caused the conflict.” (Noel Malcolm, Bosnia: A Short History). All I can say is that books written in and about (for instance) the 1940s are sufficiently replete with gruesome slaughters for the greater glory of this creed or that ethnicity as to make me uncomfortable with this reductionist position. If my own conflation (or, if you like, misunderstanding) causes pain to anyone, I am sincerely sorry.

The post The Turk and the Diplomat: An Introduction to Ivo Andrić’s “Omer Pasha Latas” appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2OWi6VS via IFTTT

1 note

·

View note