#because i look at these texts as literature from a particular historical context and have no interest or belief in spiritual aspects of it

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Hey, I was wondering if there’s an Irish polytheism equivalent to the Delphic maxims of Hellenic polytheism? I have a lot of Hellenic friends reading into the Delphic maxims a lot and it has me wondering if we have something similar, basically “universal” truths or a list of guiding principles for the Irish polytheistic faith. Kind of scared to look myself because it seems like exactly the thing to fall prey to Celtomanic Victorians and I’m still working on my research skills 😅

I'm afraid I don't know anything about Irish polytheism, since it falls outside of my remit as a medievalist, being primarily a modern phenomenon (because we know virtually nothing about historical pre-Christian Irish beliefs).

There are various medieval Irish 'wisdom' texts, including of the 'mirror for princes' variety which are basically about being a good ruler, but these are all written within the medieval Irish Christian tradition, even if they're sometimes put into the mouths of non-Christian characters. It doesn't sound like that's what you're looking for, though.

To be honest, I'm the wrong person to ask when it comes to religious engagement with this material, as I've never had that kind of relationship to it. I study it as literature, and my main focus is late texts which are very self-consciously constructed as literature and often explicitly as fiction (a concept that isn't really around at the time that the earliest stories are written, but definitely is by the 15th-18th centuries when a lot of my corpus was written). I have no connection to / knowledge of modern polytheistic practices or ideas beyond what I've picked up in passing, I'm afraid.

#anon good sir#answered#i tend to stay out of polytheistic spaces online because frankly they do not want me there#i have got much more tactful over the years but my approach is not always compatible with theirs#because i look at these texts as literature from a particular historical context and have no interest or belief in spiritual aspects of it#and am always very conscious that ireland was christianised centuries before these stories were written

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queer reading of Vulgate pt 2: Intro pt 1

The introduction is written by the translator of The Quest for the Holy Grail, E. Jane Burns. Burns begins by laying out the context of the Vulgate Cycle's structure, its history and development, and the different expectations historical readers have brought to the text.

Which underscores how expectation colors perception.

What happens if we imagine the possibility of multiple writers with different backgrounds, views, progressiveness, and agendas? Instead of assuming heteronormativity, homophobia, toxic masculinity, misogyny, and a single unified author with a singular agenda and vision - what if we stay open to the possibility of a different concept of gender than we're used to? What about possible queer subtext and the possibility of queercoding in medieval fiction, not just in modern fiction?

What if we look for those things, rather than assuming and looking for explanations that match the modern stereotypical assumptions of medieval people/writers/beliefs? (After all, it's those modern assumptions that lead to the phenomenon of "history will say they were roommates," or the all too common error of "woman buried with warrior stuff? must be religious, can't possibly be because she actually fought.")

That's what I mean by reading with a queer lens. Because most of the time, these works are read with a heteronormative, gender-normative lens, just unconscious or subconscious as a bias, and so any queer elements are missed entirely.

(Like. I still don't understand how anyone can read the passages with Galehaut as anything other than Extremely Gay. How do you miss that? Yet so many people assume it's "comrades" and "bros" despite the text going out of its way to say that it's more than companionship. Because of the default, unexamined lens that they're using.)

….anyway. off the soapbox. Back to the intro.

"Many literary historians… have mistakenly sought in Arthurian romance a recognizable ancestor text for the modern novel" and are disappointed in the somewhat disjointed conglomeration of the Vulgate. They then either dismissed it as incoherent and terrible, or defended it as having an underlying coherence and attempted to legitimize it by imagining a singular author (or unifying editor).

"The unwieldy mix of spiritual and chivalric modes that crisscross unevenly throughout… mark the Vulgate Cycle as a product of the emergent social and political tensions in thirteenth-century France," with the popularized chivalric tales of knights from the mid-twelfth-century getting infused with Biblical allusions and Grail mysteries around 1200. Prose had a more religious connotation and association than verse, which was more recreational (condemned sometimes as "vain pleasures").

"Lady readers, in particular, were exhorted after 1200 to abandon the deceptive tales of Arthurian knights." Which supports the idea that one of the primary audiences for these stories were women! Women of the 1200's French court, in the case of the French romances, though I'm sure readership extended beyond that.

This is another example of how expectation shapes perception. There's a tendency for modern readers to assume that medieval literature will be dry, dull, misogynistic, homophobic, etc… and so I've seen people assume that the vast numbers of unnamed ladies/maidens/queens are a product of misogyny, of being seen as too unimportant for distinct names.

And certainly there was systemic misogyny in the culture, just as there is nowadays - but I don't think that's the core reason for the nameless female characters. It doesn't match up with the Vulgate's characterization of these women as clever, competent, independent, and saving knights more often than being saved by knights. (Nor does it match up with how many women are named.)

I've heard a theory (probably on Tumblr somewhere, I can't remember where) that the unnamed women are the equivalent of "y/n" ("your name") in modern fanfic. Reader-insert. Perhaps the author(s) expected women reading the story to project themselves onto the characters, and so made extra room for them to do so.

…But back to the introduction once more. Burns unravels the idea of a single author or even a solid, novel-like coherent narrative for the Vulgate Cycle, and arrives at this:

"The Vulgate Cycle then provides us with a text that is not a text in the modern sense of the term, a text that is always fragmentary but always a composite of more than one text, a text located somewhere and uncertainly in the complex relation between many narrative versions created by many authorial if not authoritative hands.

"The literary map accurately representing this cycle of tales would contrast starkly with Lot’s set calendar. It would be a map that changed continually as we move through the narrative terrain it charts. Although it might incorporate on one level and for the text of the Prose Lancelot in particular the existence of a predictable calendar of events, a map detailing the whole of the Vulgate Cycle would have to reflect a much looser and more flexible narrative structure.

"It would be a map with no fixed perimeter, and no set or authorized format, a map that could shift and reshape itself at successive moments and with successive readings."

A shifting mélange of a narrative, flexible and unbounded, containing multitudes, eluding attempts to define or confine it into one single known element…

…Well. That sounds like the very definition of queer.

(pt 1 here)

#I have a lot of Vulgate feelings okay#arthurian literature#vulgate cycle#vulgate cycle introduction#E Jane Burns#arthuriana#qrv#queer reading of the vulgate#arthurian newbie#not really but that's the tag for my arthuriana read-through atm

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rereading The Fellowship of the Ring for the First Time in Fifteen Years

The previous chapter was all grouchy wizards and atmospheric walking...and this one opens with the return of Professor Tolkien medieval literature scholaring all over the page. So let's just jump in and talk "The Bridge of Khazad-Dum."

So finding the tomb of a comrade always sucks, but context is EXTREMELY required in such cases. Unfortunately, this is the moment where Professor Tolkien rears his ugly head once again. I'm a Shakespeare scholar, and moreover I was a Shakespeare scholar at a reasonably broke school in Alaska, so I designed my thesis to not require me to go look at extant original texts. When I got to my PhD, some fuckery at an administrative level meant that when my first supervisor retired, I was dumped into the lap of a film scholar, so my dissertation because EXTREMELY about film adaptations. So I don't have firsthand experience with extant historical documents and texts, but I am aware of the process. As an undergrad, I once questioned why my text said "safety" while another text said "sanity" (and was very scoffed at before the professor actually understood the question, because I phrased it poorly). The good answer though?

Extant texts from Shakespeare's day and older are PLAGUED with slipperiness that makes them difficult to read and reproduce. They come from a time before standardized spelling, and printers often weren't that careful setting type. If they come from before the printing press, you have issues with handwriting legibility and misspellings. Then there are issues with extant documents being damaged or torn or missing pages or faded by the time we get to them, especially if they've been in private hands without the experience to properly preserve them. So the difference between "safety" and "sanity" was some editor or academic's educated guess because they had a word that started with "s," ended in "y," and was probably about six letters.

Tolkien, as a scholar with an interest in medieval texts, would have understood these issues because I'd be willing to bet hard cash that his academic work required using primary sources and original extant texts. And I'm willing to bet that because we get EVERY SINGLE GODDAMN ONE OF THESE ISSUES with the Book of Mazarbul. In no particular order, here are the issues Gandalf calls out while trying to read this thing:

multiple pages are missing from the beginning

blurred words

burned words

staining (probably blood)

edged blade damage

deteriorated pages that break off

shitty handwriting

partially visible words and guesswork that goes with it

a total lack of context for any of the words you CAN make out

This book is every book scholar's worst goddamn nightmare, because you'll never recreate the whole thing, your guesses are likelier to be wrong than right, and if you don't have plot armor preserving the important stuff, you might literally end up with a description of someone's breakfast but nothing else.

I will say though, there's one thing in here that Tolkien SHOULD have been familiar with in extant texts that isn't represented here. Marginalia. Humans were humans even in the 11-1400s, and scribes and apprentices got bored while copying out books by hand. They doodled. They wrote snarkastic comments in the margins. They had to scratch things out and redo. They had cats around and sometimes little paw prints are found in old manuscripts. Like...ancient books had personality. I get where the dwarves might not have done this in their log book, especially towards the end, but I would have loved some marginalia too.

Because the first few pages of this chapter feel less like Gandalf reading the final account of the attempted Moria colony to me and more like Professor Tolkien having a moment because WHY IS THIS GODDAMN PAGE MISSING I JUST NEED THIS ONE PAGE BUT NOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO, ITS FUCKING MISSING...

Academia some days, I swear.

But we get knocked out of the academic and into the adventurous pretty fast when the drums in the deep start tolling "doom, doom." And everyone loses their goddamn minds, as any reasonable person would, because we just finished hearing about the dwarves being trapped while the drums in the deep boomed.

Aragorn isn't going down without a fight though. He and Boromir get their asses on securing the door from which the immediate danger will come, with a bit of an assist from Frodo and Sting when some ballsy Uruk puts a foot through the door.

We also get badass good guy Samwise Gamgee:

When thirteen had fallen the rest fled shrieking, leaving the defenders unharmed, except for Sam who had a scratch along the scalp. A quick duck had saved him; and he had felled his orc: a sturdy thrust with his Barrow-blade. A fire was smouldering in his brown eyes that would have made Ted Sandyman step backwards, if he had seen it.

Our boy took out an ORC all on his own!!! Sam is more than capable of taking care of business and apparently he gets scary when you back him in a corner. I entirely approve, and I cannot believe we didn't get this in the movie. GIVE ME SAM SINGLE-HANDEDLY TAKING OUT AN ORC, PETER JACKSON!!!

We also get an Orc chieftain stabbing the hell out of Frodo, which was an honor given to the cave troll in the movies. This goes by pretty fast though, even for a Tolkien battle. It's kind of a one-two stab and grab before everyone makes a run for it. We do get Sam freeing Frodo by chopping the spear haft in half, but if you're reading quickly, it's easy to miss that this should ABSOLUTELY have killed Frodo. The language is pretty clear that it doesn't, and Tolkien only kind of tokenly tries a fake-out death here, since we literally just got the mithril reminder at the end of the last chapter. But I guess technically we get a fake-out death here.

It is very quickly confirmed that Frodo is alive though, with everyone being like, "Wait, you're NOT dead?" and Aragorn and Gandalf both going, "jesus christ, hobbits are tough as nail."

As we keep running from the hordes of Orcs, Uruks, and cave trolls, things start to get hot and there is firelight in places firelight SHOULD EXTREMELY NOT BE. But it does cue Gandalf about where they are, and he points everyone toward the titular Bridge of Khazad-Dum, and the exit. Now it's just a matter of hauling ass and getting out.

Unfortunately, when Legolas turns around to shoot some bitches and buy time, this happens:

Something was coming up behind them. What it was could not be seen: it was like a great shadow, in the middle of which a dark form, of man-shape, maybe, yet greater; and a power and terror seemed to be in and to go before it. It came to the edge of the fire and the light faded as if a cloud had bent over it. Then with a rush it leaped across the fissure. The flames roared up to greet it, and wreathed about it; and a black smoked swirled in the air. It's streaming mane kindled, and blazed behind it. In its right hand was a blade like a stabbing tongue of fire; in its left it held a whip of many thongs. "Ai! ai [sic]!" wailed Legolas. "A Balrog!"

And I just need to take a second here, because like I've said, I was more familiar with the movies than the book. And I just need Tolkien to EXPLAIN HIS DAMN SELF with this description. It's maybe man-shaped, but it has a mane? Like that does give adapters a lot of room to get creative, but WHERE THE HELL DID THEY GET HORNED SHEEP LAVA THING from??? Because that ain't in the text. I do love the drama of this description though. Like, the Balrog knows it's freaking magnificent and is going to play to all the drama that being wreathed in fire and smoke gives it. Which...ngl, I love for it. This thing is damn cool.

And I appreciate that we have FINALLY met a foe that makes Gandalf just kind of stop and go "...fuck me." Because he was starting to feel a bit OP and bored, and now he's taking it seriously, which means I as a reader should be FUCKING TERRIFIED right now, and I appreciate that.

From there, this goes down basically as the movie does, with the sliiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiight deviation that Aragorn and Boromir get BACK on the bridge to have Gandalf's back, so they're like, within arm's reach of him as the Balrog falls and drags Gandalf down with it. But even the dialogue was lifted almost exactly from the page, so I don't feel like I need to go over this bit in much detail. It's badass, it's tragic, and it happens FAST.

And then, of course, everyone else has to haul ass out of there because the Balrog just took out your OP wizard with a flick of its wrist.

So they run, and they run a LOT for a LONG time. They run until they're out of bow-shot of the walls. And as readers, we are left with this final image:

They looked back. Dark yawned the archway of the Gates under the mountain-shadow. Faint and far beneath the earth rolled the slow drum-beats: doom. A thin black smoke trailed out. Nothing else was to be seen; the dale all around was empty. Doom. Grief at last wholly overcame them, and they wept long: some stand and silent, some cast upon the ground. Doom, doom. The drum-beats faded.

So my little headcanon here? Those drumbeats stop being harbingers of doom in that final paragraph and transform to metaphorical heartbeats for Gandalf. We know--because Pippin established it--that falls in Moria can be LONG. They take a while. The Fellowship got out of immediate danger range, and Gandalf could still have been falling. But all they have to go on is those faint, distant, slow drum-beats. The heartbeat/drumbeat comparison is so easy it's not a reach, and when they finally fade and stop, the sense is that there is nothing else for the army of evil to attack. That is--as far as anyone knows or can reasonably assume--the end of Gandalf. It's the literary equivalent of a jump cut and sudden stop of the drumroll in film execution scenes. It cues everyone that something has ended.

Well, this chapter was ABSOLUTELY not more atmospheric walking, and even though it cost us our wizard, I appreciated the tension, the fear, and the pacing in the chapter at large. The mix of breakneck action and still or slow moments to let everyone react or comment was really well done, and finally having something that actually managed to shake Legolas and Gandalf was genuinely scary.

We're going to leave it there for now, and next time we'll pick up with the aftermath of almost getting eaten by a Balrog and losing the mentor wizard of the party. We've only got four more chapters to go, so let's see what the pacing and party dynamics do as we head for Lothlorien sans wizard.

#reread#the fellowship of the ring#the lord of the rings#lotr#the bridge of khazad-dum#fantasy books#books and reading#books#books and novels

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

have you read ulysses by james joyce? ive been wanting to for a while but im a bit intimidated by its reputation of being hard to get through

I haven't, but I know a little about it and I do think, as with all difficult works, context & background is going to be your best friend; there's an ask by @days-of-reading from a few years back here that has some very good recs for annotated additions / supplementary material that may help guide you and make the book (or the idea of approaching the book) less daunting since you will know what went into it or the meaning behind various episodes or terms.

That said, I think an important thing to remember, and what has helped me with other challenging books / authors, is to remind yourself that, if they're difficult, they are so for a reason, and that this isn't automatically a bad thing—a book's difficulty isn't necessarily there to alienate you, scare you or threaten you, or make you feel inferior, as though you could never be up to the task (that said, some books probably do want to alienate you & attempt to do so in an aggressive or provocative manner but even then that aggression is a commentary on something; the question they pose is whether you will examine that commentary or not); more often than not it's to invite you into (often radically) different ways of experiencing a text, a language, a way of thinking and digesting / exploring the world. It's asking you to check what you know, what you think you know, and what you expect to know at the door and meet the text on its own terms.

After all, what do we mean when we say a book is "difficult"? "Difficult" compared to what logic, whose logic? What does that logic demand, and is that demand always reasonable? Is this logic actually as inviolable as we think it is? Let's say a work "doesn't make sense", but is that a problem with the work, or what we've demanded it be, without pausing to consider what it actually is, in its own words? Why has the author decided to construct their narrative like this, when they easily could have done it differently—and the natural follow-up to that question being: could they, really, have done it differently? The option was there but they chose not to. Texts that are trying to break the limits we impose on works of literature are often a commentary on those very limits themselves. Why are they there and who put them there? But most crucially: what's on the other side?

Understanding the social, cultural, and historical context that informs a particular writer's view of the world and they way that expresses itself in their work is obviously massively important, but I think there's also a lot to be said for surrendering yourself to a particular work's own logic and letting that take you wherever it will. That means accepting some parts will feel utterly nonsensical (some are meant to be) or understanding that maybe you will only read it at a pace of 3 pages an hour, or that one page will be re-read 10 times before you feel ready to move on. And it means taking that as an inherent trait of the work and learning to examine and move through it as it is exists because without it, it would be a completely different book altogether; and if you are treating / reading it as though it should be or you want it to be a different, easier, book then why are you reading it in the first place? The question of "what does it all mean?" is not necessarily the question that you have to answer when reading something, and not having an answer isn't a bad thing; sometimes finding an answer isn't even the point. Sometimes I think it's not unlike when a toddler finds something utterly benign looking—like a pebble, or a stick, and runs excitedly towards you in order to present what, to them, is probably something immensely fascinating. And maybe you don't see what they see but you kneel down and accept what they give you regardless and take part in the experience with them, because that is what the real intention behind that gesture is.

I don't know if any of this will help, but I hope you get something out of it, anon x

#anyone who has more concrete advise for ulysses specifically please do add it in!#ask#anonymous#book talks

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's... really nothing that weird or crazy about those books though. They're both perfectly coherent narratives that tie into the broader literary trends at the turn-of-the-century. They're much better understood as products of their social and literary context than as..... arsenic wallpaper fever dreams.

Common themes in horror/gothic fiction during the 1890s were fear of regression and a duality between civility and the Other: the thoroughly modern Mina vs the "devolved" vampire hordes; Dorian vs his portrait; also throw in Jekyll & Hyde as another contemporaneous example. You'll note all three involve anxiety about degeneration within the self.

These texts are written in a period wracked with social anxieties related to rapid technological innovation, the decline of the British Empire, the New Woman, and a preoccupation with "degeneration." (Though it's worth noting that Stoker and Wilde were both queer Irish writers, which influenced their writing as well.)

Dracula reflects many of these social anxieties of the 1890s. It can be interpreted as an early example of invasion fiction, representing the fear of the foreign "other" as threat; or about the feudalism of a declining aristocracy vs the modern London; or as a complicated depiction of women's sexuality and the New Woman; or reflecting Stoker's own sexual anxieties, given that he was likely queer and that Dracula was written in the wake of Wilde's trial which had a significant impact on literary circles. Note, too, that in period marked by rapid technological innovation, many then–cutting-edge technologies such as the typewriter and the phonograph act as tools to fight the ancient Dracula. (For more on different readings of Dracula and their historical context, see Maud Ellmann, preface to Dracula, Oxford World's Classic edition.)

While nowadays Dracula might be the most widely known early vampire text, it certainly wasn't the first, and Stoker "came up with" much of it not by licking the wallpaper but by studying folklore and expanding upon earlier vampire stories that were already shifting the vampire figure into the cunning aristocratic archetype we know today.

Oscar Wilde was a prominent figure in both the Aesthetic and Decadent literary movements, which challenged Victorian values of art needing "moral instruction" by instead valuing beauty, intensity, excess, artifice, and "art for art's sake." The Picture of Dorian Gray is part of that tradition and draws on the works of his Aesthetic predecessors such as Walter Pater. Dorian Gray's dramatization of Aesthetic values and exploration of themes such as excess, the role of art, duality, and Faustian bargains were probably more inspired by Wilde's active involvement in the Aesthetic literary circle and as a known social commentator than it was by, y'know, lead poisoning or whatever.

I know this was just meant to be a "funny ha ha not that serious" tweet, but why do we have the impulse to dismiss art as the kooky byproduct of wallpaper and cough medicine, rather than look at works of literature for their actual content and in the context in which they were written? Why do we blame it on ~bonkers nonsense from people high on cocaine because they didn't know better~ instead of actually engaging with the works?

The less pithy truth is that they got their ideas by being... writers who lived in a particular context, whose works contain the influences of their contemporaries and predecessors, and who were writing in a particular social climate and belonged to specific literary schools of thought.

I realize the internet would prefer to believe the curtains are just blue or whatever and that literary criticism should be replaced with YA novels, but there is actually merit to analyzing a text for both its content and its context.

#the amount of Factually Incorrect things people are saying in the notes......#I know actual op is on twitter and will never see this#but unfortunately they picked as examples two works where I know a LOT about the historical context#and this take is so.......... how shall I put this. bad.#dracula#picture of dorian gray#literature#.pdf#1890s

72K notes

·

View notes

Text

3.2 Significant Form

Approaching Clive Bell’s theory of significant form as someone who has both a Bachelor’s and Master’s in English and has taught literature courses for five years (and counting) was actually quite easy once I made the connection between his significant form and formalism. In literary theory, formalism is a type of analysis that has to do with the structural purposes of a text, essentially viewing the piece in a cultural vacuum in order to pick out its modes, genres, discourse, and forms. It looks to the structures of the plot, the characters, the settings, and the themes as they are wholly within the text, ignoring the author’s cultural, economic, and historical context as acting upon the work. To give a very simplified example, a formalist analysis of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird would focus primarily on the characters, the narrative structure, and the themes inherent in the text without connecting the experiences of the characters and events with Lee’s childhood growing up in Monroeville, Alabama in the 1930s and 1940s. Formalism implies that the author’s lived experiences have no effect upon the impact and messages of a text.

Bell’s theory states that the significant form of a piece of art is its potential to provoke aesthetic emotion in the viewer. For the sake of expounding upon his theory, aesthetic emotions are the emotions that are felt during an aesthetic activity or appreciation which can include the base, everyday variety like fear or wonder or they can refer to more complex aesthetic contexts. Aesthetic contexts take the emotions a step further and compound them into experiences like the sublime or the kitsch. Bell specifically delineates significant form from beauty, stating that an object doesn’t need to be beautiful in order to elicit the emotional response that signifies significant form. For Bell, it is the composition of a piece that gives it the ability to evoke emotions; it is the “lines and colors combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms, that stir our aesthetic emotions.”

While it still seems to view the works in a manner that excludes the artist’s intent and contextual experience, the significant form seems to approach art in a manner more emotive than formalism approaches literature. This is probably due to the fact that art and aesthetics operate on a different cerebral level than literature. While literature can evoke aesthetic emotions (gothic literature attempts to explore the sublime by triggering fear responses), it is a drawn-out process that takes the length of the piece, which even in the shortest of stories can be several minutes to an hour. Art, on the other hand, is able to trigger aesthetic emotions almost instantly, so there isn’t a period of waiting to experience significant form.

Let’s look at the difference between formalism and significant form, especially in the immediacy of the aesthetic emotional response. In order to do this let’s look at Pablo Picasso’s 1937 painting Guernica and Stephen Vincent Benét’s 1937 post-apocalyptic short story “By the Waters of Babylon.” I specifically chose this short story because I know for a fact it was written in response to the exact same April 1937 bombing of Guernica, a town in northern Spain, by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy at the request of the Spanish Nationalists that inspired Picasso to paint his piece.

Benét’s story is presented through a non-linear plot where the reader is grasping at straws trying to place the events in the historical timeline. The narrator, John, is the son of a priest and is training to be a priest himself, though priests in their society are simply those who can handle the metal collected from the Dead Places belonging to the long-dead gods. He ventures on a spiritual journey without revealing his destination is the Place of the Gods because it is a forbidden place. As he reaches the ruins, he sees a statue of a “god”-- a human-like figure that says “ASHING” on its base; he continues through the ruins and is chased by wild dogs into a large building where he finds the body of a dead god. **SPOILERS** That night John has a waking dream of a bustling city, bright with neon lights, and humans living their lives before they are destroyed by fire raining down on them from the skies. John realizes that the gods were just humans whose technologically advanced society led to their own eradication. The short story finishes by stating:

“Nevertheless, we make a beginning. it is not for the metal alone we go to the Dead Places now—there are the books and the writings. They are hard to learn. And the magic tools are broken—but we can look at them and wonder. At least, we make a beginning… We shall go to the Place of the Gods—the place newyork… They were men who were here before us. We must build again.”

The piece creates a feeling of unease and foreboding that emphasizes the theme of advancing technology past our ability to compromise and cohabitate on the planet. Taken in a vacuum as formalism dictates, the aesthetic emotions of fear and unease are developed over the course of the short story, roughly forty minutes. Thus there is significant form, but the story does it over a longer period of time.

Contrast this with Picasso’s Guernica, which is instantly unsettling upon viewing it. The chiaroscuro of the piece emphasizes the sharp lines created by the forms which configure in a confusing and unsettling composition evoking the aesthetic emotional response of fear and despair. The figures in the piece include a gored horse, a bull, several screaming women, a dead baby, a dismembered soldier, and flames all rendered in black, grey, and white. While the primary emotion evoked is fear, the lack of color emphasizes the despair at the violence wrought.

While both of these pieces are inspired by the horrors of the same bombing of Guernica, the aesthetic emotions evoked by each piece happen in different ways over different lengths of time for the audiences. Thus significant form can be applied across the full range of artistic expression be it visual, auditory, or written.

0 notes

Text

The Aftertaste of all Sweetness

posted Wed, 29 Mar 2006 00:40:28 -0800 On March 28h, 2006, the famous Internet journo-dadaist shashkin (aka jadbalja) was interviewed by Wintermute from the webzine forlorn.envy.nu. This is an excerpt from the transcript. Wintermute (W): Thanks for coming. Let's start with your latest work, You Incomplete Me just out with Medium publishing. It seems to depart from your previous oeuvre. Does this signal a move into more character and dialogue-led explorations? Shashkin (S): Great to be here. The piece you mention has actually been referred to by some as an 'epistolary novel'. Though, neither are emails really epistolary, nor is it of novel length. It could be a 'micro-' or pico- novel. Novel, novela, the magazine short story, and then the micro-novel, I suppose tracking the shrinkage of our collective attention span in the wash of pop-culture. This isn't meant to be derisive though - I've always believed that pathos can and will be conveyed if required from the most succinct of prose, and a character can be fleshed in sentences rather than chapters. Whether that's successful or not - you'll all tell me, right. Going back to the idea of the 'epistle', it's always been a literary device which writers have used to peel back layers of intimacy between characters. Anything which wouldn't be rendered adequately in common dialogue. Then you have the entire collections of the letters of historical figures, say Virginia Woolf, or Sylvia Plath. There has been a certain valorization of the literary and sentimental value of the physical letter, what we now call snail mail, though to me that image spoke of a trail of slime rather than emotion. So, my challenge here, or what I've felt challenged to do, is to see if that similar significance in terms of intimacy, and as a literary device could be extended to the most banal of communications, though I guess less banal than chatting - the email. How dada would I be if I didn't raise something utilitarian to an artform? So, to really answer your question, I'm not actually moving into 'novel' territory, if you pardon the involved pun, that is, I'm not doing anything new in terms of characters. Just trying to tell stories in new ways, with new methods. As I think you see, just a few emails is all it takes for Vahe to make a very long personal journey and there's enough hidden context and substance, I hope, in the added details. W: What kind of detail should we be looking at? S: I can't give too much way...haha. You're asking me to give a normative reading of your subjective experience of the piece! But I think, if I were to go back to it again today - and I don't really re-read what I write except when I feel the mood strike me which resonates with each work, because to me every work is the aborted child of a particular moment and mood - well, then I'd look at the dates, and the arcana of the structure of the email, the error messages. The project of uplifting emails to literature isn't easy, and the language - which I at least try to instinctively keep to what we might think is 'business English' slants heavily to the utilitarian and the prosaic, so to add what I feel are the important elements, deepening the fiction in time and in mordancy I have to play with what is happening outside the text. So, in a sense, my canvas is both the email text and its attendant trappings. But sometimes, as in the stolen 'real' exchange between Pat and idali [Ed: entry 'Nevertheless, dear'], the people writing the emails provided me with everything I'd need in the texts themselves, so when I put them together, edited in a certain way, they transcend, i.e., I have the gestalt. W: I think I see. This is a continuing theme though, for you - this experimentation with the 'trappings' of our communication culture, mediated as it is by machines and software? I was thinking especially of the piece about the French girl and the hacker.. S: Yes, The Girl and her Hacker [Ed: entry 'Arpanet']. I am very interested in the linguistics of software interfaces, the way there is a new grammar in online forms, and checkboxes and other widgets and knobs of our surfing experience. I think that story isn't the best example of that kind of experimentation though. It just happens that I chose to present certain communications in the text in what I think are approximations of actual software interfaces. But in a sense, what I am saying is that checkboxes, buttons and scrollbars are now ubiquitous in our reading of the electronically generated word, but we don't see them as part of our language because we still think in sentences and paragraphs and these elements are outside those modular linguistic forms. So, what happens when I insert them in a sentence with an attempt at syntax, and fill them with a word, or emboss them with some meaning, do they become just placeholders for letters, independent semiotics, or a blend? This is for me the continuing element of evolution in the way we conduct the business of writing... W: There's another theme, isn't there - not in terms of subject or experimental focus, but the emotional core of your work, that is, the sense I get that you're really the only poet of urban alienation of a certain kind, of apartments and chatrooms and cubicles. It resonates with me, and I'm sure with anyone who lives alone in a metropolis, it's really an unique kind of vibe. I know you've said before that your work is not directly autobiographical - but do you want to explain if it is indirectly, that is, where are you channeling this from? S: Haha, I hope you're not feeling this resonance only because you're a figment of my imagination, or well - my creative imagination. W: No, please don't trivialize my response - I think there is individuality even in those who are not individuals. S: I'm sorry, I didn't mean that you're not self-contained. Well, this really brings me to an interesting response, because I was going to talk of the author-text-character-reader distances, and the whole system of reflected selves, but that would all get too post-structuralist a discussion and I like to keep it more general. What you are right about is that the sense of alienation which I am definitely channeling is a deeply felt thing, even if I didn't feel all that those in my pieces feel. In the apartment arc of texts [Ed: entries 'Department of Ennui' & 'Chaque Jour'] I was involved in a particular kind of funk, a Los Angeles moment which I haven't quite tapped ever again. But I am sure in some way, what that protagonist is saying in first person is vocalizing some of my interiority, and that is the kind of schizophrenia - Whitman's 'I am large, I contain multitudes'- kind of thing that I revel in. You, me, we're all split off from the same deep core of shashkin-itude, that frothing bubble of textual gold. Though, in retrospect, a good schizo is someone who isn't aware he/she is schizophrenic, so I guess I've overanalyzed myself out of the real fun. W: Over analysis is always a dreadful shame. Still, there is this amazing diversity in your published work, which is startling. You've covered ground as an urban fantasist, symbolist poet, 'found text' artist and something which I can only term as 'conceptual blogging'. But in general, even amidst the diversity, there is more than just the alienated apartment-dwellers, but a sense of genuine sadness, and loss. Were you abused as a child? S: Sadly, I had a reasonably content childhood and terrorized the local neighborhood children as a bully, so there's not much material there. As an adult male I think have more troughs than I have crests, but I think all artists choose over a certain emotional territory that which they feel most comfortable in. I'd be wary though if you find me only working with the sad bricks. You only get typecast into a certain emotional bracket if you're a bad artist. I guess I'd produce happy work if I felt happier, but I'm not sure if that would be readable. Sadness is a more complex emotion than happiness, isn't it? I just read somewhere that as humans we're more evolved to be sad than happy.. W: Perhaps what I meant was wistful, or longing. Something the Germans call 'sehnsucht'. The addiction to longing. S: I like that word. There is definitely a lot of longing in my characters, but sometimes it's just involved satire or allegory, as in the God in the Midwest piece [Ed: entry 'Neon Summer']. I think allegory is sorely underappreciated in literature today. I am tired of dry conceptual formalism. I thought Dada was fun when it was happening - and the recent exhibition in the city sort of goes into that - but rebels aren't always the most emotionally sensitive. The rabble aren't roused by weeping. I think some of those political-artistic battles are won, but to continue the war, I think the emotional core is important in today's conceptual prose, or whatever goes as the avant-garde. In fact, since so much of the stylized conceptual art is so diminished of the sensual or the emotive, to show that one has sentiment as a writer, the affliction of 'humors' as Victorians would call it, is positively revolutionary. And I like that. W: Sensitive, but without becoming a neo-confessional. We don't want you to be the male Anne Sexton.. S: No worries. W: We're nearly done here, but I did want to hear more about your process of creation. You're hardly regular in your output and some of us wonder what process you've got there, as a writer? You mentioned moods, and how they reflect in the pieces, and you're right, you do have some of those angry pieces tucked away, and the prose poems, and also the stuff I can't categorize, like the incomparably beautiful Howling for Sade.. S: Thank you. I'm not sure how I wrote that one, because it seems uncharacteristic in retrospect. I'd also reconsider the gratuitous French today, especially since I don't speak it, but at the moment I was very into Messiaen and it seemed to stick. All my titling, at both levels, are matters of serendipity that way. I don't have a set process, and the days you could just sit down before a typewriter and bang away for some hours and have something just doesn't work. Working with a laptop is somehow more organic, though Baudrillard has argued for the opposite, about how he feels there is a distance between the electronic text and him, which lacks the immediacy of the paper, the typewriter hammers and the pins.. Sometimes my moments of greatest lucidity - when my muse is closest to me - are when other voices fall silent, when my inner horror at myself stops singing its Lethean hymn, and I stop doing - everything. A moment of stillness. Mostly when I am lying in bed, curled and heart stopped because that ineffable thing has happened, the idea has sparked. That's how I get my poems. And I haven't 'received' a poem for a long time. For prose, I do need to sit down and work through it, and I usually do not make many changes. Something about the moment has to be right. W: Yes, when the moment is right, just like sometimes when I am reading one of your pieces - like some of the shorter ones we published on forlorn.envy, which, in the atmosphere of the right music, the right hour, fills me with such a strange and overwhelming sensation of kinship, of shared experience. I feel very giddy telling you this, but considering you are my creator... I do feel that we are thinking the same great thought. My face gets that first flush of heat, that rushing behind your eyes which makes me wonder if I'll break into tears, how delicious it is to feel moved by a work of art - S: Ssh. You have to stop. W: Excuse me.. Even though I don't exist, I feel quite animated. S: It's a good thing. W: Just one more thing. Are you going to complete that 'Crossing' story [Ed: entry 'Strange light in your eyes']? What about new poetry? S: I'm not sure about that one. I never introduced the girl, and that had to have a poignant ending. I have the story in sight, but I think it's more useful to me right now, to let it spool out in the imaginations of the readers, the "hypocrite lecteurs".. Ah well, poetry. I only write poetry in the throes of mortal sadness, and I must not have been feeling it - so nothing has descended to me from the muse Calliope. Maybe I've crossed some threshold into apathy and apathy just doesn't do it for poetics. W: Fine. Thanks for the interview. Are you going to snuff me out of existence, since this conceptual farce is concluded? S: I was thinking about it. Do you mind terribly? W: No go ahead, after all I [Ed: end of transmission]

0 notes

Note

Do you know of any fossil words in Spanish, words that used to be common but fell out of use and are now only preserved in idioms? I tried looking on Google but all the results were English-only examples

I'll try and think of some others but here are the ones that come to mind; and I’m not sure all of these will be what you’re looking for.

si fuere menester = "in the event of" el menester used to be fairly common especially in the Medieval period, where it was another word for "need" or "necessity". Today you only see menester in si fuere menester which is an unusual construction as it is, since fuere is the future subjunctive - which is an obsolete tense - and so it literally means "should it be necessary". This expression only now shows up in contracts and legal contexts normally as "in the event of"

donde fueres haz lo que vieres = "when in Rome... (do as the Romans do)" Again, this is future subjunctive; literally "wherever you go, do what you see".. but in a more obtuse future subjunctive way "wherever you should happen to go, do whatever you may happen to see"

la urdimbre y trama = "warp and weft" The idea of this is related to "weaving", and though this phrase is rather antiquated or particular, it occasionally shows up as something like la urdimbre y trama de la sociedad or something where that's "the fabric of society". It's not the way you say that so much now [el tejido or la tela are more common], but urdir "to warp" was related to working a loom. You still do use tramar but it's not often that you see it related to weaving anymore... tramar is "to plot" or "to hatch a scheme", but you can see how "weaving" would go into "plotting"

so pena de = "under pain of" You don't often see so used in Spanish today, since it's a more direct link to Latin and Italian. And today la pena rarely means "pain" in the physical sense, it usually means "sorrow" or "anguish"... but again in legal cases, so pena de muerte is "under pain/penalty of death"

a diestra y siniestra = "all over the place" This expression literally means "to the right and left". The word diestro/a is still "right-handed" (also means "skillful" or "dexterous"), but siniestro/a used to mean "left-handed"... the idea that the left hand was more evil and "sinister", and "under-handed". In older contexts, siniestro/a means "left-handed", but in modern contexts you say zurdo/a for "left-handed"

al tuntún = "impromptu", "improvise", "on the fly", "by ear" This expression is derived from Latin, ad vultum tuum which is literally "to your face" in Latin. You never see tuntún anymore unless something is done al tuntún but it might be more regional; it just means you're making it up as you go

dormir como un ceporro = "to sleep like a log" Most people today say dormir como un tronco which is the same idea; el ceporro is a variation but it's extremely unusual to see it. Most people will use tronco if they have to

tuerto/a = one-eyed I'm actually not sure if people use tuerto/a still, since there are other ways to say "blind in one eye" or "one-eyed". In older Spanish, tuerto could show up as a "grievance", but in the expression en el reino de ciegos el tuerto es rey is still used sometimes, literally "in the kingdom of blind people, the one-eyed man is the king"

(el) haba = bean [technically haba is feminine] Not common to see el haba used much anymore except in certain contexts, and it's the root of la habichuela "bean". In Spain, sometimes haba is "idiot" so if you see el tonto del haba it's like "the biggest idiot that ever lived"

Vuestra Merced = "Your Lordship/Ladyship" This is the original form of it, but it eventually turned into usted "you" used for polite things. The title was Vuestra Merced and it was how you addressed someone without knowing their title, so it became very polite. In older Spanish you'd abbreviate it as Vd. which eventually became Ud. as the abbreviation for usted. Keep in mind that at a certain point in time, Spanish wrote the U sound as a V, and it followed more of the Latin pronunciation where the V had a softer U/W sound at times. Outside of Spain and works set in older time periods, you're unlikely to use vuestro/a - it even became informal plural "you all" in Spain - but you rarely ever see merced used. Chances are you're only going to see it was vuestra in front of it. But just know that vos has a very different meaning today than it did in the Middle Ages

meter/sembrar cizaña = "to sow discord" You're never going to see cizaña used in any other context unless you happen upon some botanical book. The literal translation is "darnel" which is sometimes called "false wheat"; basically la cizaña looks like trigo "wheat", and it grows close to wheat but it often has a fungus that's poisonous so you need to separate it. The idea behind it is that if you're deliberately planting cizaña you're actively trying to poison someone or make things worse

la celestina = "a go-between, a mediator" This word comes directly from La Celestina a novel written in Spain's Golden Age by Fernando de Rojas. In it there's a woman named Celestina who sets up meetings between women living in convents (who weren't always nuns) and men; acting as a go-between and chaperone for love affairs basically. The term was also la alcahueta but became celestina after the character in the book. Certain characters in literature are considered celestinas like the Nurse in Romeo and Juliet; basically the girl/woman can't risk her reputation so she has her maid or chaperone working to arrange things, and they're often the catalyst for things going wrong. In other contexts, celestina or una alcahueta is a "pimp" or "madame", or sometimes "a gossip"

pardo/a = brown, brownish-gray Today you’re only really going to see pardo/a used with animals. Specifically, el oso pardo is a “grizzly bear”, and pardo/a can be used with horses as “dun”. I don’t know if “grizzly bear” counts as an expression but anyway. In older Spanish pardo/a was another word for “brown” when it came to people too. Today, if you’re describing hair color as “brown/brunette” you’re using castaño which is literally “chestnut”, either castaño claro “light brown” or castaño oscuro “dark brown”. When it comes to things that are brown, the typical word is now marrón or sometimes you see it as color café which is “coffee-colored”

ser un caco = to be a thief Not commonly used as ladrón, ladrona “thief”, but un caco literally means “a Cacus”. Basically, Cacus was a mythological figure who stole some cattle and Hercules killed him. In some places people use un caco to mean “thief” as a euphemism

la Parca = the Grim Reaper Orginally, las Parcas were the Parcae in Roman (originally Greek) mythology. They were the sisters of fate who would measure someone’s life and eventually cut the thread. Today, it’s just one Parca and it’s typically a male figure, skeletal, with a scythe as the “Grim Reaper”, rather than it being a woman with scissors. That’s because during the Plague, people thought of Death as being a skeletal figure that held a scythe, the symbol for “reaping” wheat that was ripe.

manjar de los dioses = “nectar of the gods” / a delicacy el manjar is used in some places in certain contexts but it originally came from Italian as “food” or something “to eat”. Today, manjar is usually a “snack”, or in some cases it’s dulce de leche, but most of the Spanish-speaking world doesn’t use manjar so much. It is sometimes “delicacy”, but in older contexts it was code for “ambrosia”, the thing that the Greek gods couldn’t get enough of. The world manjar still feels very antiquated to me, but when it’s used it’s some kind of good food or eating a lot of food

valer un potosí = “to be worth a fortune” un potosí is pretty antiquated, but it came from the city Potosí in Bolivia which was famous for its silver mines that the conquistadores exploited. There are still some places that will use potosí as “something of great value”, though it’s not so common anymore unless you’re talking about the actual city.

moros y cristianos = “beans and rice” Usually it’s black beans and white rice, though this is literally “Moors and Christians”. You still use cristiano/a today but typically you only use moro/a in a historical sense

Also there’s the expression más sordo/a que una tapia where it means someone is really hard of hearing; literally “as deaf as a garden wall”, but I’ve never seen people use tapia ...only a muro or a cerca as “wall” or “fence”. The idea of tapiar is related to “mortar” and “masonry”

There are also some expressions related to metal and older words for it. For example, saturnino/a is an older word for “gloomy”, though it now refers to “lead-poisoning”. Saturn was linked to “moodiness” in alchemical society, and the symbol for Saturn was the older symbol for “lead”.

This is similar to how áureo/a is “gold” but also linked to the “sun” because the Sun and gold are linked.

Another is el azogue which is the older word for mercury so it’d be “quicksilver”. You may see azogarse in some texts where it means “to be fidgetty” and it’s related both to mercury-poisoning, and probably to the idea of Mercury/Hermes being the messenger god so always on the move.

There is also hidalgo/a which doesn’t have quite the same meaning it did originally. Today, hidalgo/a is sort of like “having noble blood”. It literally means “son of something/someone”, where originally in Spain hidalgos were the children of nobles - specifically, it tended to refer to the children of nobles who weren’t the firstborn male. Firstborn sons often got about 2/3 of the money and were expected to run the estates. The second or third or fourth children were usually on their own. It became a running joke that the firstborn became the lord, and the others would either join the army or the clergy. In Cervantes’s time, hidalgos could be among the poorest of society, even poorer than slaves in some cases. They were still “noble” in terms of blood though, and hidalgos couldn’t be tortured by the Inquisition because of it. So they were afforded certain rights, but usually tended to be poor or lower than you’d expect a noble to be. Today it just means “of nobility”, but in Cervantes’s time a hidalgo was the symbol of Spain under the Holy Roman Empire - wealthy and noble and glorious in theory, much poorer in reality.

I'd also add the phrases levar ancla "to raise anchor" or "anchors aweigh/away", where levar is rarely used today aside from nautical terms. Similarly, izar la bandera is "to hoist the flag"... not a lot of chances to use izar if it's not related to "flags" or la vela "a sail"

I also would say errar is less common today in Spanish. It's still used, but you normally say cometer un error "to make a mistake". Still, errar es humano, perdonar es divino "to err is human, to forgive divine". Also errar is weirdly irregular at times, it turns into yerro as present tense yo

And I’m also going to include when la manzana means a “city block”. Today manzana is not rare, it means “apple”. But manzana as a “city block” was originally mansana where it meant a “collection of manses/houses arranged in a block on a grid”. So there’s that. If you ever see manzana used for blocks in a city, it’s technically a separate word

Also depending on context el mar “sea” will be la mar with the feminine article. That’s usually more particular, usually meaning “open water” or deeper waters like alta mar “high seas”. The more poetic or open the water is, the more likely it is to be feminine, and so la mar isn’t quite so antiquated but it’s a little special

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another aspect of this I'd like to see used more is considering how the reader/viewer/audience augments the interpretation with the unique psychosocial setup that they bring to the table.

The way that we, as consumers of fiction, have lived in particular geographical, historical, social, political etc contexts shapes us and our mental makeup (situatedness) in such a way that makes interpretations of literature different person to person. Austen for me is very different to Austen for you.

I think early 'decoding authorial-intent' approaches were partly about counteracting the influence of situatedness; remove reader bias to get to the 'true' meaning. Then post-Barthes works started to say no, we don't need the authorial intent, we can have just the text.

But I still find few instances where literary criticism, or media interpretation generally, is humble enough to say 'look I interpreted it this way probably because of these experiences of mine'.

Lay people talking about representation are actually better at doing this. Like, it matters to me the hero is female bc so am I, etc.

But I think a lot of media critics still see their job as above that. Like to be a pro, you have to transcend your own subjectivity and situatedness and justify critique with evidence directly from the text. It's a sort of hubris we see often when intellectuals presume their rationality can just strongarm its way out of subjectivity.

But I think it would be very interesting for critics to instead note the elements of their own situatedness that made a text poignant for them, or if they catalogued their own biases for or against the text as part of critical rigour.

I tend to believe that art is not the text or the painting itself - is a statue sunk to the ocean floor still being art? - but that art exists in the multivalent interactions between creator, text, and viewer. So I'd like to see literary critics consider where they, themselves, interact with the text, because I think that is part of the generative activity of art.

When I took my literary criticism theory class in undergrad the professor told us that in modern literary criticism “The author isn’t dead but they are a ghost breathing down your neck”

Basically, the old way of thinking was that the point of literary criticism was to find the true original intentions of the author. Then death of the author was introduced and literary criticism swung hard the other way, saying that what the author thinks and the context they were in doesn’t matter.

Nowadays, it’s somewhere in between. Yes the author had intentions and yes the work had context. But the work also has context right now and a history of people reading it and interpreting it and sometimes an author puts meaning in something that they didn’t realize they were.

I can’t sit down and interview Jane Austin about every little decision she made in Pride and Prejudice but I can look at what we know about her life and the era and place she lived in. I can also ignore all that and look at what the book means right now to modern people. I can compare Austin to writers in her own time as well as writers now. I can speculate on what I think was on purpose and what wasn’t.

A lot of people go on about death of the author like that’s the only correct way to interpret fiction when modern lit crit moved past it years ago. Reading critically is a conversation between the author, the reader, and the various contexts surrounding both of them. Nothing exists in a vacuum but at the same time nobody can anticipate every interpretation their work might present with.

The question of analysis and separating art from artist isn’t a simple cut and dry issue. It never has been and it never will be.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

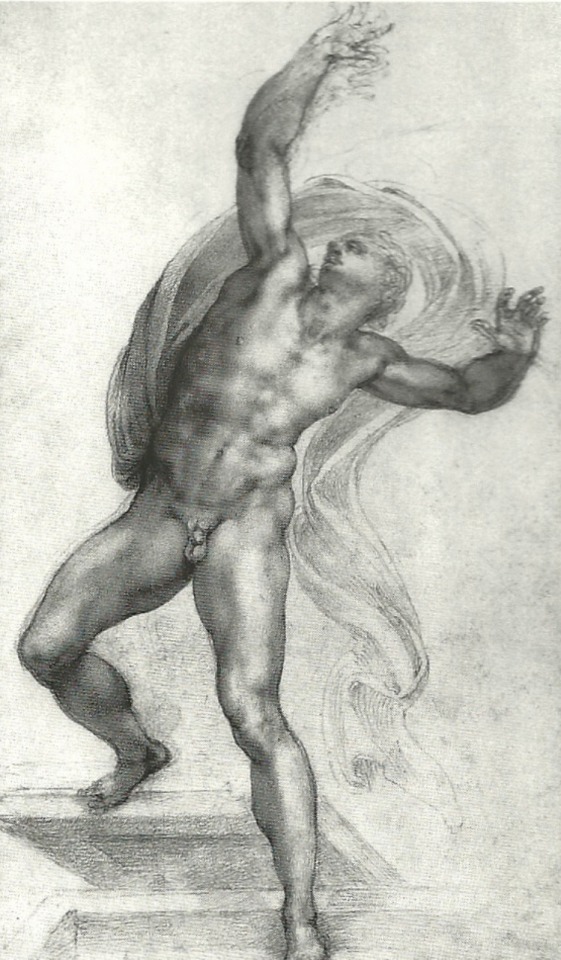

Michelangelo’s The Risen Christ: Discovering the sacred in the profane.

The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.

- Michelangelo Buonarroti

While a visit to Rome’s grand squares like Piazza Navona is at the top of everyone’s list, there is much more to the Eternal City. The Piazza della Minerva, is one of Rome’s more peculiar squares and is a must-see for lovers of Bernini’s work.

As one of the smaller squares in Rome, Piazza della Minerva holds some interesting sites. Built during Roman times, the square derives its name from the Goddess, Minerva, the Roman Goddess of wisdom and strategic warfare. During the 13th Century, the decision was made to build a Christian Church on top of what was once a square dedicated to a pagan Goddess – and so the church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva was born, a beautiful example of Gothic architecture and Rome’s only Gothic church.

In fact this is the only Gothic church in Rome. It resembles the famous Church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. There are three aisles inside the church. The soaring arches and the ceiling in blue are outstanding. The deep blue colours dominate the structure while the golden touches promote the intricate design. There are paintings of gold stars and saints. The stained glass windows are beautiful too.

In the centre of the Piazza is an elephant with an Egyptian obelisk on its back, one of Bernini’s last sculptures erected by Bernini for Pope Alexander VII and possibly one of the most unusual sculptures in Rome. There are several theories which aim to decipher Bernini’s inspiration for the sculpture, some of which point to Bernini’s study of the first elephant to visit Rome, while others point to a more satirical combination of a pagan stone with a baroque elephant in front of a Christian church.

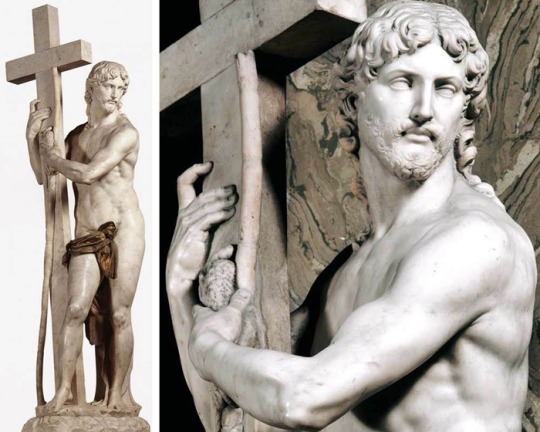

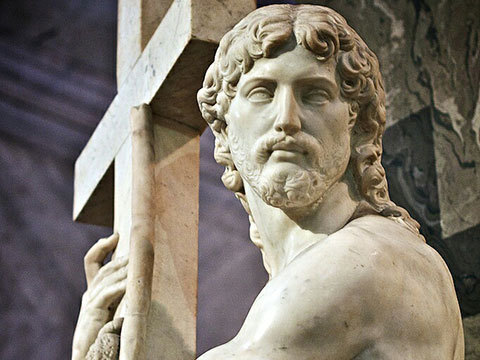

Tourists flock to see the elephant but more often than not they miss out visiting an almost forgotten marble masterpeiece by Michelangelo himself inside the church. This controversial statue has resided in the Santa Maria sopra Minerva Church in Rome for almost five hundred years. Indeed The Risen Christ by Michelangelo is one of the artist's least admired works. While modern observers frequently have found fault with the statue, it satisfied its patrons enormously and was widely admired by contemporaries. Not least, the sculpture has suffered from the manner in which it is presently displayed and from biased photographic reproduction that emphasises unfavorable and inappropriate views of Christ.

Around 2017 I was fortunate on a visit back to London to see once again Michelangelo’s marble masterpiece, The Risen Christ, which was being displayed in all its naked glory at an exhibition at the National Gallery.

This was another version of this great sculpture that no one has got round to covering up. It has just come to Britain. Michelangelo’s first version has been lent to the National Gallery, in London, for its exhibition Michelangelo and Sebastiano del Piombo in 2017. It came from San Vincenzo Monastery in Bassano Romano, where it languished in obscurity until it was recognised as Michelangelo’s lost work in 1997.

I found it profoundly moving then as I had seen the other partially clothed one on several visits to the church in Rome. It has always perplexed me why this beautiful work of art has been either shunned to the side with hidden shame or embarrassment when it holds up such profound sacred truth for both art lover or a Christian believer (or both as I am).

Michelangelo made a contract in June 1514 AD that he would make a sculpture of a standing, naked figure of Christ holding a cross, and that the sculpture would be completed within four years of the contract. Michelangelo had a problem because the marble he started carving was defective and had a black streak in the area of the face. His patrons, Bernardo Cencio, Mario Scapucci, and Metello Vari de' Pocari, were wondering what happened when they hadn't heard for a while from Michelangelo. Michelangelo had stopped work on The Risen Christ due to the blemish in the marble, and he was working on another project, the San Lorenzo facade. Michelangelo felt grief because this project of The Risen Christ was delayed. Michelangelo ordered a new marble block from Pisa which was to arrive on the first boat. When The Risen Christ was finally finished in March 1521 AD Michelangelo was only 46 years old.

It was transported to Rome and this 80.75 inches tall marble statue was installed at the left pillar of the choir in the church Santa Maria sopra Minerva, by Pietro Urbano, Michelangelo's assistant (Hughes, 1999). It turns out that Urbano did a finish to the feet, hands, nostrils, and beard of Christ, that many friends of Michelangelo described as disastrous). Furthermore, later-on in history, nail-holes were pierced in Christ's hands, and Christ's genitalia were hidden behind a bronze loincloth.

Because people have changed this sculpture over time; many are disappointed with this work of art because it is presently different than the original work that Michelangelo made. The Risen Christ had no title during Michelangelo's lifetime. This sculpture was given the name it has now, because Christ is standing like the traditional resurrected saviour, as seen in other similar works of art.

It was in discussion with an art historian friend of mine currently teaching I was surprised through her to discover the sculpture’s uncomfortably controversial history. There is no doubt Michelangelo’s marvellous marble creation has raised robust debates about where beauty as an aesthetic sits between the sacred and the profane. And nothing exemplifies that better than the phallus on Michelangelo’s The Risen Christ.

For the majority of its time there, however, the phallus has been carefully draped with a bronze loincloth - incongruous at best, and prudish at worst, but either way a less than subtle display of the historic Church’s discomfort with the full physicality of Christ.

Indeed, it is worth noting that this attitude prevails, at least in some sense, into the twentieth-century: the version of the statue in Rome remains covered to this day, and much of the critical attention the sculpture has received after Michelangelo’s death has been grating. Romain Rolland, an early biographer, described it as ‘the coldest and dullest thing he ever did’, whilst Linda Murray bluntly dubbed the work ‘Michelangelo’s chief and perhaps only total failure’. But Michelangelo himself saw no such mistake. The censored statue seen in Santa Maria sopra Minerva is what we might call his second draft.

It’s interesting to note that when artist was originally commissioned to sculpt a risen Christ in 1514, he had all but completed it before realising that a vein of black marble ran across Jesus’ face, marring the image of classical perfection which he so wished to emulate. It had nothing to do with the phallus. Furious, Michelangelo abandoned this Christ - the one I saw at the National Gallery - and began again. Even given a fresh chance, he chose to retain Christ’s complete nudity.

Why was this of such importance to Michelangelo? Why did he so strongly wish to craft the literal manhood of Christ, as never depicted before? Part of the answer may lie in his historical context: the Renaissance in Italy was driven in the part by the remains of Roman antiquity discovered there; study of the classics became commonplace, and scholars tended to consider the Graeco-Roman world as a cultural ideal, with ancient art in particular being emblematic of a lost Golden Age. Famously, classical sculpture was almost always nude.

In his interview with The Telegraph in 2015, Ian Jenkins, curator of the British Museum exhibition “Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art”, attempted to explain this tradition. ‘The Greeks … didn’t walk down the High Street in Athens naked … But to the Greeks [nudity] was the mark of a hero. It was not about representing the literal world, but a world which was mythologised.’

We see evidence for this trend in Greek literature as well as sculpture: Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, considered by some to be the earliest known works of Western literature, were likely written between the 8th and 7th centuries BC, but their setting is in Mycenaean Greece in the 12th century. The Greeks believed that this earlier Bronze Age was an epoch of heroism, wherein gods walked the earth alongside mortals and the human experience was generally more sublime. In setting the texts at this earlier stage in Greece’s history, Homer echoes the belief held within his contemporary society that mankind had been better before (what we might now call nostalgia, or, more colloquially, “The Good Old Days syndrome”). There is a real feeling of delight present in the distance Homer creates between his actual, flawed society, and the idealised past.

Indeed, it calls to mind a line I once read in an introduction to L.P. Hartley’s The Go-Between, by Douglas Brookes-Davies: ‘Memory idealises the past’. Though modernist texts such as The Go-Between problematise this, in antiquity it was not only commonplace but celebrated to look back to a more perfect existence and relive it through art. The very fact that Michelangelo abandoned his sculpture after years of work on account of a barely noticeable flaw in the marble is evidence that he, too, was striving towards the classical ideal of perfection. ‘Unfortunately,’ Hazel Stanier has commented, ‘this has resulted in unintentionally making Christ appear like a pagan god.’

This opens up another question – why does such a rift exist between the way ancient cultures envisaged their divinity and our own conceptions of a Christian God? Why are we not allowed to anthropomorphise the deus of the Bible in the same way that the Roman gods were?

Christ, of course, makes this somewhat confusing, given that he is described in the Bible as ‘the Word made flesh’, a physical and very human incarnation of the spiritual being that we call God. Theology tells us that he is fully human and fully divine, and yet the Church have excluded him from many aspects of life that a majority of us see as typifying a human being. Christ has no apparent sexual desires or romantic relationships, and though not exempt from suffering, he does not play any part in sin (which, as the saying goes, is ‘only human’). I think that the enormous controversy caused by films such as The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), which explore the possibility of Jesus having a sex life, is reflective of the possibility that - though in theory the Christian messiah is fully human - we feel significant discomfort at the notion that he may have explored particular aspects of the human experience.

Purists and the prude and liberals rush to opposite sides of the debate. If purists run one way to completely deny Christ had any sexual desires or even inclinations as all humans are want to do, liberals commit the sin of rushing to the other extreme end and presuppose that Jesus did act on sexual impulses simply because it was inevitable of his human nature.

I think the truth lies somewhere between but what that truth might actually be is simply speculation on my part. It doesn’t detract for me the life and saving mission of redemption that Jesus was on - to suffer and die for our sins as well as the Godhead reconciling itself to sacrificing the Son for Man’s sins and just punishment.

Of course, it is well-known that the classical gods had no qualms about sexual activity. It is difficult to make retrospective judgements about citizens’ opinions on this but, as it was the norm, we might assume that they felt it was rather a non-issue. I can empathise with some critics who reason that the Christian God is not entitled to sexual expression is because of the traditional Christian idea that sex is inherently sinful – that original sin is passed on seminally and so by having sex we continue to spread darkness and provoke further transgression. It is from this early idea that theological issues such as the need for Mary to have been immaculately conceived (she was not created out of a sexual union, much like her son) have stemmed. But here - the immaculate conception - the critics are profoundly wrong in their theological understanding of why God had to enter the world as Immanuel in this miraculous way.

Some Christian critics - and I would agree with them - assert that the vision of a naked Christ might make a powerful theological point in a world where sex still carries these connotations. They rightly point out that clothing - and I might extend this to mean the covering-up of the sexual parts of our body - was only adopted by humankind after the Fall, the nudity of Christ is making a statement about his unfallen nature as the second Adam. In other words, Christ has no shame, because he is sinless and has no need for shame. Perhaps what Michelangelo intended was actually to disentangle nudity from its sexual, sinful associations, instead presenting us with a pre-lapsarian image of purity taking the form of the classical Bronze Age hero.

There is another, less theological explanation for the sculptor’s obvious use of the classical form. It reminds us of a time when gods walked the earth alongside us, when they were fully human – us, only immortal. Maybe he wanted to emphasise that fully human aspect of Christ’s being. Questionable as much of their behaviour was, the classical gods were certainly easy to identify with. For Michelangelo, this may have been his own way of embodying John 1:14 in marble: ‘The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us’.

It is here critics may have gotten hold of the wrong end of the stick with The Risen Christ when they point out the odd proportions of the figure: that it has a weighty torso, or the broad hips atop a pair of tapered and rather spindly legs, or even a side or rear view of the figure that show Christ’s buttocks.

For a start, this ungainly rear view was not supposed to be seen. The statue was meant to go in a wall niche, so that the back of the statue was hidden. Michelangelo of course knew this, and shaped the statue so that it would appear well proportioned from the front. If we view the sculpture from the front left, perhaps its best side, then Christ is no longer a thickset figure. Rather, his body merges with the cross in a graceful and harmonious composition.

The turn of Christ’s body and his averted face suggest something like the shunning of physical contact that is central to another post-Resurrection subject, the Noli me tangere (“Touch Me Not”). The turned head is a poignant way of making Christ seem inaccessible even as the reality of his living flesh is manifest.

We are encouraged to look at not Christ’s face, but the instruments of his Passion. Our attention is directed to the cross by the effortless cross-body gesture of the left arm and the entwining movement of the right leg. With his powerful but graceful hands, Christ cradles the cross, and the separated index fingers direct us first to the cross and then heavenward. Christ presents us with the symbols of his Passion – the tangible recollection of his earthly suffering. Behind Christ and barely visible between his legs we see the cloth in which Christ was wrapped when he was in the tomb. He has just shed the earthly shroud; it is in the midst of slipping to earth. In this suspended instant, Christ is completely and properly nude.

We must imagine how the figure must have appeared in its original setting, within the darkened confines of an elevated niche. Christ steps forth, as though from the tomb and the shadow of death. Foremost are the symbols of the Passion, which Christ will leave behind when he ascends to heaven.

Why was Michelangelo compelled to portray Christ completely naked in a way that was bound to trouble some Christians? It was not out of a desire to blaspheme. On the contrary, this genius – poet, architect and painter as well as the greatest sculptor who has ever lived – was not only a faithful Christian but someone who thought deeply about theology. You can bet he had good religious reasons to depict Christ in full nudity.

But it would be complacent to think there was no tension in showing Christ nude. The fact that The Risen Christ in Santa Maria still has its covering proves how real those tensions are. The fundamental reason Michelangelo could get away with it was that he was Michelangelo. By the time he created this statue, he had the Sistine Chapel ceiling (with all its male nudes) under his belt and was the most famous artist in the world.

For centuries, the faithful have kissed the advanced foot of Christ, for like Mary Magdalene and doubting Thomas, they wish for some sort of physical contact with the Risen Christ. To carve a life-size marble statue of a naked Christ certainly was audacious, but it is also theologically appropriate. Michelangelo’s contemporaries recognised, more easily than modern viewers, that the Risen Christ was a moving and profoundly beautiful sculpture that was true to the sacred story.

#the risen christ#michelangelo#marble#church#christian#beauty#aesthetics#statue#religious#renaissance#history#rome#bernini#art#arts#culture#society#religion#sculpture

201 notes

·

View notes

Text