#bamberg witch trials

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

So if my 'calculations' are 'correct,' there would be approximately 450,000-600,000 people alive today that are direct descendants of the people killed in all the witch trials.

No wonder the human race is getting dumber; we killed all the smart people 😒

#salem#witch#witch trials#witch trials of Trier#Bamberg#fulda#würzburg#valais#north berwick#pendle#torsåker#german witch trials#supernatural

1 note

·

View note

Text

German Witch Trials.

I have German in my blood so for next three years I am letting my hair grow naturally while collecting information and ingredients while studying spell work again. A witches real power as well comes from her hair as well because it holds Wisdom as the book of Proverbs says with the scrolls written by Kind Soloman son of King David.

What are the names of the German witch trials? Würzburg witch trials - Wikipedia The Würzburg witch trials were among the largest Witch trials in the Early Modern period: the series was one of the four largest in Germany along with the Trier witch trials, the Fulda witch trials, and the Bamberg witch trials.

This is witch history I am putting on my blog because its in my blood as well, also biggest rule in witch craft. It you don't want to open portals or doors to evil things. Don't use blood. It seals and creates a bond you can't get away from and energy is big in this field of magic no matter what anyone says.

#pagan wicca#spellcraft#traditional witchcraft#paganblr#folk magic#eclectic witch#book of shadows#witches of tumblr#witch stuff#witchcraft community#green witch#witch aesthetic#witches#beginner witch#baby witch#don't insult the witch#moon witch#witch#witch community#witch tips#witch blog#pagan witch#witch vibes#witchcraft#witchcore#witchcraft 101#witchery#witchy#witchy things#witchblr

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Witch Trial Fact Sheet

(Not every individual claim has a source, but the links included will source everything said here - a lot of them have a lot of relevant stuff, so if I linked for everything it would be putting in the same links again and again).

The witch trials were a relatively small-scale affair - modern historians give a range of 30,000 to 50,000 deaths between 1560 and 1660, the witch-hunting century or 30,000-60,000 between 1430 and 1780. That sounds massive - but it's over a century (so 300-600 a year) in a Europe with a population of 100 million (if you're wondering about population growth, it was much lower in the pre-industrial world - about 10% a century, with the demographic disaster that was the Thirty Years War negating much of that). So in any given year, the percentage of the population being killed for witchcraft was ... 0.0003% to 0.0006%.

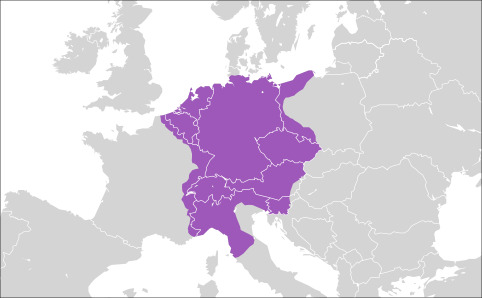

It's even starker when you consider that the trials were very unevenly spaced geographically. Of those 30,000-60,000 people killed for witchcraft, 25,000 to 30,000 of them were in the Holy Roman Empire.

Witch hunting was not a solely or even mostly Catholic phenomenon. The biggest, most famous witch trials - Trier, Fulda, Basque Country, Würzburg, Bamberg, North Berwick, Torsåker and Salem. All of them were experiencing the Reformation, while the places with the fewest witch trials were thoroughly Catholic Ireland, Spain, Portugal and Italy. And the Spanish Inquisition killed only two witches.

It was not exclusively women who were killed for witchcraft; around 10-15% of people killed for witchcraft were men.

Similarly, witch trials were not simply (and I personally don't think primarily) about religious misogyny. The witch trials of Iceland and the Baltic countries were about enforcing Christianity on areas that were still largely pagan - and in an age when men accessed learning and political power far more and more easily than women, it's no coincidence that these witch trials mostly targeted men. In many cases, it was about searching for a culprit for the miseries of the Thirty Years War (remember that the Holy Roman Empire killed more people for witchcraft than everywhere else in Europe combined?) and the Little Ice Age. In many of the German trials, it was about enforcing Catholic or Protestant orthodoxy. My own country's (England's) bloodiest witch trials were in the midst of the English Civil War.

Witch trials were not a medieval phenomenon - large witch trials only began in 1430 and the "witch-hunting century" was 1560 to 1660, and the middle ages are generally agreed to have ended between 1450 and 1500.

Not everyone believed in witchcraft even at the time; both the Malleus Maleficarum and Daemonolgie devoted their opening sections to arguing that witchcraft existed - why would they have done this unless there were numerous, vocal or well-established people saying it didn't? And take the Malleus' word for it; "some curates of souls and preachers of the Word of God feel no shame at claiming and affirming in their sermons to the congregation that sorceresses do not exist." And we even have De Praestigiis Daemonum (1563) and The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584) making the case for the unreality of magic.

The Malleus Maleficarum was not an official Catholic manual at any time; when Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger submitted it to the University of Cologne theology faculty for approval, they rejected it for promoting torture and teaching erroneous theology. Its use was almost entirely by secular courts.

Burning was not universal - in Britain and the American colonies, witches were hanged. As Daemonologie says, "[the execution of witches] is commonly used by fire, but that is an indifferent thing to be used in every country, according to the law and custom thereof."

Midwives were not more likely to be accused - in fact, they were more likely to be accusers.

Even at the height of the witch trials, some occult practices were widely accepted. In the words of Daemonologie "... diverse Christian princes and magistrates, severe punishers of witches, will not only oversee magicians to live within their dominions, but even sometimes delight to see them prove some of their practices." No less a figure than Thomas Aquinas approved of astrology and had some sympathy for alchemy and divination, and there was a sharp line drawn between "natural magic" such as astrology that called upon powers inherent in creation and was therefore morally neutral and the immoral "unnatural magic" of witches, drawing on the devil.

Tabitha Stanmore, historian of magic at the University of Exeter, says in her book Cunning Folk: Life in the Age of Practical Magic that "... In my research I have found reference to more than 380 service magicians practising in England between 1542 and 1670, many of whom were healers and midwives, diviners and goods-finders. Of these, fewer than five were accused of malevolent witchcraft, and only one was eventually found guilty and executed ... For most people at the time, there was a difference between the useful magic generally being practiced and sold by cunning folk and the harmful, vindictive curses dealt out by witches." (p.85, emphases added)

If you've enjoyed this, you can listen to a performance of Daemonologie, complete with definitions of obsolete and Scottish dialect words, here. (If you're wondering how a treatise can be performed, the book is framed as the dialogue of two characters).

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

And this doesn't tell the full story - a lot of the deaths were concentrated in single witch hunts. For example, in the Holy Roman Empire, over 2000 deaths (a significant portion of the total) died in just three witch hunts (Bamberg, Trier, Würzburg) 1581 and 1632.

For more on witch hunts, I wrote this Witch Trial Fact Sheet a while back.

Witch hunt victims

Approximate statistics on the number of executions for witchcraft in various regions of Europe in the period 1450-1750

by Yellowapple1000

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

Die dunklen Lande

(english: The Dark Lands)

Author: Markus Heitz

Genre: Fantasy

Published: 2019

Language: German

Rating: 🔮🔮🔮🔮🔮 (5/5)

Plot:

During the Thirty Years’ War, in the year 1629, young adventurer Aenlin Kane travels to the German city Hamburg with the persian mystic Tahmina at her side to come into her father Solomon Kane’s inheritance. However, first she has to carry out an important mission, before she will be shown any of the heirlooms: Aenlin and Tahmina are to accompany a group of mercenaries and help them escort some protestants safely from Bamberg, away from gruesome witch trials, to Hamburg. None of the group are aware just how much the world’s fate rests on their shoulders, as they set out on their initial quest and are soon dragged into a fight against dark powers.

Content Warnings:

racism, pedophilia/child abuse, death of a child, war, death, violence, torture, (attempted) rape, misogyny, swearing

Opinion & Thoughts:

This is the second book I’ve read so far from Markus Heitz and I can say it’s one of my general favourites. I love his writing style and I believe he has a great way of writing dark content that’s still great to read and captivating. The characters feel like real people and their individual goals, struggles and hopes let me connect to them, fear for them and be happy for them when something finally worked out in their favour.

Concerning the well written characters I have to mention how much I loved our two female protagonists. Not only did I like Aenlin’s and Tahmina’s characterizations and how natural their interactions seemed, I was oftentimes wondering whether or not they were only travel partners or maybe more (although Tahmina is stated as Aenlin’s “Freundin”, this word can mean both “platonic female friend” or “girlfriend” in German, which left their relationship slightly ambiguous at the beginning). Throughout the book many (both subtle and obvious) hints are placed to show the reader they’re actually girlfriends. Their relationship and love for each other seemed so genuine during the story, especially when one of both was in danger and the other desperately tried to save her partner. This made the short kiss at the end of their struggles so much more rewarding.

Although I liked many of the characters, of course there are also those I couldn’t stand. Some of them made it quite easy, for example one of the mercenaries, Statius, with his cruelty in fights, blatant sexism and disregard for consent, or one of the main antagonists, der Venezianer (the Venetian) - a very young barmaid, Osanna, around 14 years old, who had travelled around with him and his own group of mercenaries for a bit in their quest to unleash ancient evil upon the world was killed later in the story, which revealed she had been pregnant with his child at that time. On the other hand there were others who started as somewhat dislikeable but grew on you while reading.

All in all I liked how fantasy was merged with history in this book and can recommend it to everyone who fancies a thrilling and dark fantasy novel.

#markus heitz#die dunklen lande#reading#books#book recommendations#fantasy#book review#queer protagonist

0 notes

Text

good morning to the 5 women in my city who got accused of witchcraft in the early 15th century but outsmarted the witchhunter in court so in the end THEY had HIS ass executed instead. girlpower <3

#i want a horror movie about them#good morning to them ONLY#Txt#i love this story because the dude had been in bamberg before which we all know#was a wild ride#they burned the MAYOR (witch trials really were a gender inclusive event <3)#and then he comes here and he's like OHoho let me accuse some influential women of witchcraft#IMMEDIATELY dies#it was in this moment he knew. he'd fucked up.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

JSTOR Articles on the History of Witchcraft, Witch Trials, and Folk Magic Beliefs

This is a partial of of articles on these subjects that can be found in the JSTOR archives. This is not exhaustive - this is just the portion I've saved for my own studies (I've read and referenced about a third of them so far) and I encourage readers and researchers to do their own digging. I recommend the articles by Ronald Hutton, Owen Davies, Mary Beth Norton, Malcolm Gaskill, Michael D. Bailey, and Willem de Blecourt as a place to start.

If you don't have personal access to JSTOR, you may be able to access the archive through your local library, university, museum, or historical society.

Full text list of titles below the cut:

'Hatcht up in Villanie and Witchcraft': Historical, Fiction, and Fantastical Recuperations of the Witch Child, by Chloe Buckley

'I Would Have Eaten You Too': Werewolf Legends in the Flemish, Dutch and German Area, by Willem de Blecourt

'The Divels Special Instruments': Women and Witchcraft before the Great Witch-hunt, by Karen Jones and Michael Zell

'The Root is Hidden and the Material Uncertain': The Challenges of Prosecuting Witchcraft in Early Modern Venice, by Jonathan Seitz

'Your Wife Will Be Your Biggest Accuser': Reinforcing Codes of Manhood at New England Witch Trials, by Richard Godbeer

A Family Matter: The CAse of a Witch Family in an 18th-Century Volhynian Town, by Kateryna Dysa

A Note on the Survival of Popular Christian Magic, by Peter Rushton

A Note on the Witch-Familiar in Seventeenth Century England, by F.H. Amphlett Micklewright

African Ideas of Witchcraft, by E.G. Parrinder

Aprodisiacs, Charms, and Philtres, by Eleanor Long

Charmers and Charming in England and Wales from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Century, by Owen Davies

Charming Witches: The 'Old Religion' and the Pendle Trial, by Diane Purkiss

Demonology and Medicine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, by Sona Rosa Burstein

Denver Tries A Witch, by Margaret M. Oyler

Devil's Stones and Midnight Rites: Megaliths, Folklore, and Contemporary Pagan Witchcraft, by Ethan Doyle White

Edmund Jones and the Pwcca'r Trwyn, by Adam N. Coward

Essex County Witchcraft, by Mary Beth Norton

From Sorcery to Witchcraft: Clerical Conceptions of Magic in the Later Middle Ages, by Michael D. Bailey

German Witchcraft, by C. Grant Loomis

Getting of Elves: Healing, Witchcraft and Fairies in the Scottish Witchcraft Trials, by Alaric Hall

Ghost and Witch in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, by Gillian Bennett

Ghosts in Mirrors: Reflections of the Self, by Elizabeth Tucker

Healing Charms in Use in England and Wales 1700-1950, by Owen Davies

How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants?, by Ronald Hutton

Invisible Men: The Historian and the Male Witch, by Lara Apps and Andrew Gow

Johannes Junius: Bamberg's Famous Male Witch, by Lara Apps and Andrew Gow

Knots and Knot Lore, by Cyrus L. Day

Learned Credulity in Gianfrancesco Pico's Strix, by Walter Stephens

Literally Unthinkable: Demonological Descriptions of Male Witches, by Lara Apps and Andrew Gow

Magical Beliefs and Practices in Old Bulgaria, by Louis Petroff

Maleficent Witchcraft in Britian since 1900, by Thomas Waters

Masculinity and Male Witches in Old and New England, 1593-1680, by E.J. Kent

Methodism, the Clergy, and the Popular Belief in Witchcraft and Magic, by Owen Davies

Modern Pagan Festivals: A Study in the Nature of Tradition, by Ronald Hutton

Monstrous Theories: Werewolves and the Abuse of History, by Willem de Blecourt

Neapolitan Witchcraft, by J.B. Andrews and James G. Frazer

New England's Other Witch-Hunt: The Hartford Witch-Hunt of the 1660s and Changing Patterns in Witchcraft Prosecution, by Walter Woodward

Newspapers and the Popular Belief in Witchcraft and Magic in the Modern Period, by Owen Davies

Occult Influence, Free Will, and Medical Authority in the Old Bailey, circa 1860-1910, by Karl Bell

Paganism and Polemic: The Debate over the Origins of Modern Pagan Witchcraft, by Ronald Hutton

Plants, Livestock Losses and Witchcraft Accusations in Tudor and Stuart England, by Sally Hickey

Polychronican: Witchcraft History and Children, interpreting England's Biggest Witch Trial, 1612, by Robert Poole

Publishing for the Masses: Early Modern English Witchcraft Pamphlets, by Carla Suhr

Rethinking with Demons: The Campaign against Superstition in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe from a Cognitive Perspective, by Andrew Keitt

Seasonal Festivity in Late Medieval England, Some Further Reflections, by Ronald Hutton

Secondary Targets: Male Witches on Trial, by Lara Apps and Andrew Gow

Some Notes on Modern Somerset Witch-Lore, by R.L. Tongue

Some Notes on the History and Practice of Witchcraft in the Eastern Counties, by L.F. Newman

Some Seventeenth-Century Books of Magic, by K.M. Briggs

Stones and Spirits, by Jane P. Davidson and Christopher John Duffin

Superstitions, Magic, and Witchcraft, by Jeffrey R. Watt

The 1850s Prosecution of Gerasim Fedotov for Witchcraft, by Christine D. Worobec

The Catholic Salem: How the Devil Destroyed a Saint's Parish (Mattaincourt, 1627-31), by William Monter

The Celtic Tarot and the Secret Tradition: A Study in Modern Legend Making, by Juliette Wood

The Cult of Seely Wights in Scotland, by Julian Goodare

The Decline of Magic: Challenge and Response in Early Enlightenment England, by Michael Hunter

The Devil-Worshippers at the Prom: Rumor-Panic as Therapeutic Magic, by Bill Ellis

The Devil's Pact: Diabolic Writing and Oral Tradition, by Kimberly Ball

The Discovery of Witches: Matthew Hopkins' Defense of his Witch-hunting Methods, by Sheilagh Ilona O'Brien

The Disenchantment of Magic: Spells, Charms, and Superstition in Early European Witchcraft Literature, by Michael D. Bailey

The Epistemology of Sexual Trauma in Witches' Sabbaths, Satanic Ritual Abuse, and Alien Abduction Narratives, by Joseph Laycock

The European Witchcraft Debate and the Dutch Variant, by Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra

The Flying Phallus and the Laughing Inquisitor: Penis Theft in the Malleus Maleficarum, by Moira Smith

The Framework for Scottish Witch-Hunting for the 1590s, by Julian Goodare

The Imposture of Witchcraft, by Rossell Hope Robbins

The Last Witch of England, by J.B. Kingsbury

The Late Lancashire Witches: The Girls Next Door, by Meg Pearson

The Malefic Unconscious: Gender, Genre, and History in Early Antebellum Witchcraft Narratives, by Lisa M. Vetere

The Mingling of Fairy and Witch Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Scotland, by J.A. MacCulloch

The Nightmare Experience, Sleep Paralysis, and Witchcraft Accusations, by Owen Davies

The Pursuit of Reality: Recent Research into the History of Witchcraft, by Malcolm Gaskill

The Reception of Reginald Scot's Discovery of Witchcraft: Witchcraft, Magic, and Radical Religions, by S.F. Davies

The Role of Gender in Accusations of Witchcraft: The Case of Eastern Slovenia, by Mirjam Mencej

The Scottish Witchcraft Act, by Julian Goodare

The Werewolves of Livonia: Lycanthropy and Shape-Changing in Scholarly Texts, 1550-1720, by Stefan Donecker

The Wild Hunter and the Witches' Sabbath, by Ronald Hutton

The Winter Goddess: Percht, Holda, and Related Figures, by Lotta Motz

The Witch's Familiar and the Fairy in Early Modern England and Scotland, by Emma Wilby

The Witches of Canewdon, by Eric Maple

The Witches of Dengie, by Eric Maple

The Witches' Flying and the Spanish Inquisitors, or How to Explain Away the Impossible, by Gustav Henningsen

To Accommodate the Earthly Kingdom to Divine Will: Official and Nonconformist Definitions of Witchcraft in England, by Agustin Mendez

Unwitching: The Social and Magical Practice in Traditional European Communities, by Mirjam Mencej

Urbanization and the Decline of Witchcraft: An Examination of London, by Owen Davies

Weather, Prayer, and Magical Jugs, by Ralph Merrifield

Witchcraft and Evidence in Early Modern England, by Malcolm Gaskill

Witchcraft and Magic in the Elizabethan Drama by H.W. Herrington

Witchcraft and Magic in the Rochford Hundred, by Eric Maple

Witchcraft and Old Women in Early Modern Germany, by Alison Rowlands

Witchcraft and Sexual Knowledge in Early Modern England, by Julia M. Garrett

Witchcraft and Silence in Guillaume Cazaux's 'The Mass of Saint Secaire', by William G. Pooley

Witchcraft and the Early Modern Imagination, by Robin Briggs

Witchcraft and the Western Imagination by Lyndal Roper

Witchcraft Belief and Trals in Early Modern Ireland, by Andrew Sneddon

Witchcraft Deaths, by Mimi Clar

Witchcraft Fears and Psychosocial Factors in Disease, by Edward Bever

Witchcraft for Sale, by T.M. Pearce

Witchcraft in Denmark, by Gustav Henningsen

Witchcraft in Germany, by Taras Lukach

Witchcraft in Kilkenny, by T. Crofton Croker

Witchcraft in Anglo-American Colonies, by Mary Beth Norton

Witchcraft in the Central Balkans I: Characteristics of Witches, by T.P. Vukanovic

Witchcraft in the Central Balkans II: Protection Against Witches, by T.P. Vukanovic

Witchcraft Justice and Human Rights in Africa, Cases from Malawi, by Adam Ashforth

Witchcraft Magic and Spirits on the Border of Pennsylvania and West Virginia, by S.P. Bayard

Witchcraft Persecutions in the Post-Craze Era: The Case of Ann Izzard of Great Paxton, 1808, by Stephen A. Mitchell

Witchcraft Prosecutions and the Decline of Magic, by Edward Bever

Witchcraft, by Ray B. Browne

Witchcraft, Poison, Law, and Atlantic Slavery, by Diana Paton

Witchcraft, Politics, and Memory in Seventeeth-Century England, by Malcolm Gaskill

Witchcraft, Spirit Possession and Heresy, by Lucy Mair

Witchcraft, Women's Honour and Customary Law in Early Modern Wales, by Sally Parkin

Witches and Witchbusters, by Jacqueline Simpson

Witches, Cunning Folk, and Competition in Denmark, by Timothy R. Tangherlini

Witches' Herbs on Trial, by Michael Ostling

#witchcraft#witchblr#history#history of witchcraft#occult#witch trials#research#recommended reading#book recs#jstor

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

poisonwasthecure:

Woodcut illustrating types of torture used in Bamberg witch trials.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Würzburg Witch Trials: The Germany Witch Hunts

https://historytheinterestingbits.com/2016/06/11/bamberg-germany-the-early-modern-witch-burning-stronghold/

The Würzburg witch trials of 1625–1631, which took place in the self-governing Catholic Prince-Bishopric of Würzburg in the Holy Roman Empire in present-day Germany, is one of the biggest mass trials and mass executions ever seen in Europe, and one of the biggest witch trials in history.

The 15th and 16th century had prominent witch hunts, but no one in America talks about them nearly as much as they talk about Salem. Salem, evidently, has become a sort of attraction. There is nothing wrong with bringing up topics as this for educational purposes and getting people interested and excited about learning of history, however it is undeniable that America, specifically the United States, widely ignored the Germanic witch trials. It even barely acknowledges the trials done in England, which were small in comparison to the atrocities committed in Germany during those witch hunts.

“ The height of the German witch frenzy was marked by the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum (“Hammer of Witches”), a book that became the handbook for witch hunters and Inquisitors. Written in 1486 by Dominicans Heinricus Institoris and Jacobus Sprenge, and first published in Germany in 1487, the main purpose of the Malleus was to systematically refute arguments claiming that witchcraft did not exist, to refute those who expressed skepticism about its reality, to prove that witches were more often women than men, and to educate magistrates on the procedures that could find them out and convict them. The main body of the Malleus text is divided into three parts; part one demonstrates the theoretical reality of sorcery; part two is divided into two distinct sections, or “questions,” which detail the practice of sorcery and its cures; part three describes the legal procedure to be used in the prosecution of witches.“ - Witch Trials in Early Modern Europe and New England

https://streetsofsalem.com/2011/10/24/german-witches/

“... [The] clerical/political leaders of territories like Eichstätt, Bamberg, Würzburg, Mainz, or Cologne harshly hunted witches, often by violating civil rights of the accused. Torture could be carried out on hearsay evidence from as few as two witnesses, and contrary evidence by equally valid eyewitnesses could be ignored. Although imperial legal codes were supposed to prohibit repeated torture, professors and lawyers argued that further bouts of torture were a mere continuation of the first application. Tortured victims produced fantastic stories and accusations that fed the frenzy of the hunts. By about 1630 this wave of persecutions petered out. Many critics had raised voices against the entire practice of hunting witches. Friends of the persecuted had appealed to the emperor and institutions of imperial government like the Imperial court in Speyer or the Diet which in turn called for a halt. And many of the biggest foes of witches simply died. Witch hunts throughout the empire would continue to sporadically break out until the witch laws were revoked in the eighteenth century. Authorities legally executed the last witch in the empire, Anna Maria Schwägelin, in 1775.” - A Witchy Hunt: Germany 1628

Here is an educational game about the Germanic witch hunts: https://departments.kings.edu/womens_history/witch/hunt/index.html

It goes into detail into what the torture was like and what the logic of the time was. Here is an example of some of what it tells in the story you partake in.

“The judge in the middle says, "We need to be more sure about your connection to witchcraft. You will be examined for the devil’s mark." The armed men take you to a small room. They take off all your clothing. You are too frightened to protest. An official takes a long needle and begins pricking you.He pokes it into your skin. You are too afraid to say something wrong. You barely flinch, even when he sticks it into unmentionable parts. Blood spots your skin.

The man with the pricker says to the guards, "I have incontrovertibly found the devil’s mark on this person!"They allow you to put your clothing back on. Then they escort you into the courtroom again. You stand before the judges. The judge in the middle says, "We now have serious and certain evidence that you are a witch. Further questioning on the matter will be done by our appointed magistrate. Guards, take the prisoner to a cell."The armed men take you by the arms and lead you out of the courtroom, through the courthouse, to stairs that lead down.“

https://departments.kings.edu/womens_history/witch/hunt/whbg.html

https://www.law.berkeley.edu/research/the-robbins-collection/exhibitions/witch-trials-in-early-modern-europe-and-new-england/

#witches#witchcraft#witchlife#witch coven#witchblr#beginner witch#baby witch#green witch#wicca#witches of the world#black witches#witchywoman#witchy spells#witchy things#Witchy Business#witchy#witchcraft practice#witchcraft elements#witch community#witchcraft herbs#witchcraft help

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…There is a real belief on behalf of a not insignificant subset of society that the medieval Church was a shadowy organisation dedicated solely to suppressing knowledge and scientific advancement. This is not true.

The Church was in all actuality the medieval period’s largest benefactor of scholars of all stripes. Initially, in the early medieval period much learning was focused in monastaries in particular. Because monks took a vow to eschew idleness, they were always looking for new ways to work for the greater glory of God, or whatever. Sometimes this took the form of doing manual labour to feed themselves, but as monasteries such as Cluny rose to prominence they did more and more work in libraries as well.

Monks copied and embellished manuscripts and kept impressive libraries. Sometimes this work took place inside what we call “scriptoria” where more than one scribe is working at a time. They saw themselves as charged with transmitting knowledge. A lot of that knowledge was, of course, pagan, because they were extremely into classical thinkers. They were also reading this work of course, and writing their own commentaries on it. Many of them took the medical texts and used them to set up hospitals within their monasteries, as we have talked about before.

Lest you think this is all one big sausage fest, women were also very much about that book life within nunneries. They also had their own scriptoria and were busy scribbling away, reading, writing, and thinking. If you wanted a life where you strove for new scholarly heights, odds were that in the early medieval period you did that inside a monastery on nunnery.

As the medieval period moved on, scholarship eventually moved out of the cloister and into cities when the medieval university was established. The first degree awarding institution to call itself a university was the University of Bologna established around 1088, though teaching had been going on there previously and students had been going to Bologna from at least the late tenth century. Second was the University of Paris, which was established in 1150. Again teaching had been happening there from much earlier, and at least 1045.

Medieval universities weren’t like universities now, in that they didn’t have established campuses or anything like that. They were, more or less, a loose affiliation of scholars who would provide lessons to interested students. The University of Paris, for example, described itself as “a guild of teachers and scholars” (universitas magistrorum et scholarium).

In Paris there were four faculties: Arts, Medicine, Law, and Theology. Everyone had to attend the Arts school first where they would be asked to learn the trivium, which was comprised of rhetoric, logic, and grammar. Basically that meant all undergrads spent their time learning to argue, which is how the whole Abelard thing comes about. Then if they wanted more they could go do medicine, law, or theology. Theology was considered the really crazy good stuff, as medieval theologians were sorta held up in the way we worship astrophysicists like Neil de Grasse Tyson (ugh) or Stephen Hawking now. But if you wanna be a dick and super modern about it and think that nothing is more important than science, you will note that medicine is there and actively pursued.

So what, what does all of this have to do with the Church not being suppressive? Well literally everyone, both scholars and students in a medieval university was a member of the clergy. That’s right. Are you a Christian and you wanna learn about medicine? Well you need to take holy orders first. So every single scientific advancement that came out of a medieval university (and there were plenty) was made by a man of the cloth.

The quick among you might have spotted that the thing about unis is that they were just for dudes though, and that is lamentably true. Women weren’t able to take the same orders as men, which means they were excluded from university training. Plenty of them got tutored if they were rich. (See poor Heloise who just had Abelard, like, do himself at her.) Otherwise there was plenty of sweet stuff going on in nunneries still and always, as the visionary natural biologist Hildegard of Bingen can attest. Monasteries were also still producing good stuff as Thomas Aquinas would be happy to let you know from the comfort of his Dominican order.

Given that all of this is the case, it’s hard to square that circle of “the Church is intentionally suppressing knowledge!” with the fact that everyone actively working on acquiring and furthering knowledge was a member of it and all. The Church was a welcoming home to scholars because it was a place where you got the time needed to contemplate subjects for a long time. If you have your corporeal needs taken care of, then you can go on to think about stuff. The Church offered that.

Having said all of this, there were, of course, plenty of Jewish and Muslim scholars at work in medieval Europe as well. The thriving Jewish communities of the medieval period had their own complex theological discussions about the Talmud, and produced their own truly delightful sexual and scientific theory that I will never tire of reading.

I’ve also talked at length about how Islamic medical advances were very much taken on board by medieval Christians in Europe. The fact that the Christians in holy orders beavering away at the medical faculties of universities across Europe were very much looking to a Muslim guy called Ibn Sinna for medical knowledge makes it hard to see the Church as an oppressive hater of all things non-Catholic. I’m just saying.

What else is at play here? Meh, society writ large. A lot of us in the English as a first language speaking world, and in northern Europe more generally have been raised in a Protestant context even if we ourselves are not Protestant. The thing about that is Protestants, famously, is that they are not huge fans of the Church. Big news, I know. In the Early Modern period this could get kinda wild, with things like the Great Fire of London being blamed on a nefarious “Papish plot”, for example, becoming a nice early example of a conspiracy theory. (That conspiracy theory was still written in Latin at the based of The Monument built to commemorate the fire until 1830 when the Catholics were officially emancipated in Britain. LOL.)

When the whole Enlightenment thing went down, generalised distrust of Catholics was then later compounded by the fact that “serious” thinkers aka Voltaire’s ridiculously basic self began to categorise the accumulation of knowledge specifically in opposition to religious thought. This is the old “Age of Reason” which we currently allegedly reside in, versus the “Age of Faith” idea. The Church as an overarching institution from the age of faith was therefore thought of as necessarily regressive, and it became assumed that it has always been actively attempting to thwart advantage for vaguely sinister reasons that are never fully articulated.

…Now, plenty of people were killed for witchcraft because they were doing medicine. The witch trials were a very real thing, and you know when and where they happened? In the modern period, and usually with a greater regularity in Protestant places. Witchcraft trials peak in general from about 1560-1630 which is the modern period. The most famous trials with the biggest kill count took place in Trier, Fulda, Basque, Wurtzburg, Bamberg, North Berwick, Torsåker and Salem. You know what was going on in most of the places? The Reformation. Witch trials sort of reflected various confessions of Christianity’s ability to effectively protect their flocks from evil. Did Catholics kill “witches” oh you bet your sweet ass they did. So did Protestants, and it was all fucking ugly.

What is important to note is that in countries where Catholicism was static witch trials were largely unheard of. Ireland, the Iberian Peninsula, and Italy, for example, just didn’t go in for them even though they were theoretically in the clutches of a nefarious Church bent on destroying all medical knowledge or something.

Now, none of this is to excuse the multifarious sins of the institutional Church over the years. In many ways my entire career as a medieval historian is a product of the fact that I was frustrated with the Church after 16 years of Catholic school. If you had to go to a High School named after the prosecutor in the Galileo trial, you might also end up devoting yourself to picking intricate theological fights with the Church, OK? (Yes, this is my origin story.)

And that brings us to the crux of the matter: if you make up a bunch of stuff that the Church did not do it makes it harder to critique them of the manifold things they actually did do and are doing right fucking now. We need to be critiquing the Magdalene Laundries; the international cover up of pedophile priests; signing an actual concordant with Nazi Germany; the regressive attitudes towards abortion and contraception that happen still, now, and endanger the lives of countless women. All of this is real, and calls for the strongest possible condemnation.”

- Eleanor Janega, “JFC, calm down about the medieval Church.”

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red, Wild and Free. Nordic/Scottish lines definitely showing today. Amongst other ones but lovin the red witch..

History of the Red Haired Witch

Even today, witches and women with magical abilities are often portrayed as having red tresses; from Hocus Pocus’ Winnie Sanderson to Melisandra ‘The Red Woman’ in Game of Thrones.

Societies have had a love/hate relationship with redheads throughout history. We have been worshipped and revered, but also degraded and feared, depending on the era, with the notion that we possess supernatural abilities either stemming from or causing that fear in many cultures:

1. IN SOME CULTURES TODAY, PARTICULARLY IN AFRICA, WHERE VOODOO AND MAGIC ARE STILL CENTRAL TO THEIR BELIEF SYSTEMS, REDHEADS ARE STILL THOUGHT TO BE WITCHES.

Probably due to our rarity in those regions.

2. THE CELTS IN WESTERN EUROPE, WHOSE TRADITIONS WERE STEPPED IN MAGIC, HAD FLAME-COLORED HAIR, WHICH THEY BELIEVE CONTRIBUTED TO THEIR POWERS AND STRENGTH.

Latin writings from the thirteen hundreds claim that redhead blood could turn copper into gold.

3. IT IS A WIDESPREAD FOLK BELIEF THAT REDHEADS ARE WITCHES, PROBABLY BECAUSE OF THEIR RARITY.

According to the Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca, there is even “evidence that some ancient pagan sorcerers dyed their hair red for certain rituals”.

As we are aware though, to be associated with magic or supernatural power was not always a favorable position to find yourself in.

4. IT IS REPORTED THAT MANY CHRISTIANS IN THE SIXTEENTH TO THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES BELIEVED THAT REDHEADS WERE AFFILIATED WITH THE DEVIL AND SATANIC PRACTICES.

Because of this, red hair was a marker of witchcraft and magical abilities, and during witch hunts, redhaired people were often suspected and found guilty by witch hunters.

This was no light accusation, as between 40,000 to 60,000 people were sentenced during the witch trials, many of whom were drowned or burned at the stake, in attempt to cleanse society of all witches. Perhaps the large numbers of redheads reported to have been murdered during the trials are due to the fact that a large portion of the trials were held in Scotland, where red hair would have been more common, and so a larger percentage of redheads would have stood trial.

Similarly, in the German witch trials which took place in Würzburg, Trier, Fulda and Bamberg, ginger-haired people were said to have been put on trial, tortured and murdered, under the assumption that those who possessed red tresses must have been witches. During the Spanish Inquisition, it was believed that red hair was a result of its wielder stealing fires from hell, and so many were branded as witches and burned to death.

5. IN SCOTLAND AND IRELAND FISHING COMMUNITIES AND TOWNS, IT USED TO BE BELIEVED THAT IF YOU WERE TO SPOT A RED-HAIRED WOMAN, YOU WOULD CATCH NO FISH THAT DAY.

It is still considered unlucky to take a redhaired woman on board a boat – a bias that I have come up against myself!

6. WE SHOULD REMEMBER THAT WOMEN WHO WERE INTELLIGENT OR DIFFICULT TO CONTROL WERE OFTEN ACCUSED OF WITCHCRAFT BECAUSE THEY INTIMIDATED AUTHORITIES OR THOSE AROUND THEM.

It was because it was rare or unusual for a woman to stand her ground or rebel against societal norms that they were singled out as witches.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The usual witch trial narrative is horrendously inaccurate and simplistic - but, @tlaquetzqui, replacing it with an inverted inaccurate and simplistic narrative isn't the way to go. It's going to be a long post, so I'm putting in a "keep reading".

So I'm a nerd about witch trials, and just read Tabitha Stanmore (historian of magic at the University of Exeter)'s Cunning Folk: Life in the Era of Practical Magic about, well, "cunning folk"; folk magic practitioners in late medieval and early modern England. So I've got a lot to say here.

Firstly, I'll agree with you about the numbers, and that's definitely a point in your favour.

Misogyny absolutely played a role in the witch trials. King James' Daemonologie, the definitive witch-hunting manual of the English-speaking world, said: "What can be the cause that there are twenty women given to the craft when there is one man? ... The reason is easy, for that sex is frailer than man is, so is it easier to be entrapped in these gross snares of the Devil, as was over-well proved to be true, by the Serpent's deceiving of Eve at the beginning, which makes him the homelier with that sex sensine." (Book 2 Chapter 5, spelling modernised). Cunning Folk notes that "... there was clearly a growing perception in the sixteenth and early seventeenth century that cunning women bordered on witchcraft, while cunning men belonged to an intellectual elite" (Stanmore p.223)

King James was, of course, male, as was Matthew Hopkins, the deadliest witch-hunter in my country, and the authors of the Malleus Maleficarum.

There were a multitude of motives for witch trials: religious tension, regions were Christianity was weak, weak court systems (32:40 to 33:55) or attempts to purge Anabaptism (35:27 to 38:01) and so on.

Witch trials were a primarily Protestant phenomenon, but it's sheer fantasy to say Roman Catholics took no significant part in it - Trier, Fulda, Würzburg and Bamberg all show this wasn't the case. Heinrich Kramer, author of the Malleus, was a Dominican friar (albeit one with a tendency to portray his own idiosyncratic opinions as Church teaching). Because, then as now, many Roman Catholics either didn't understand or dissented from Church teaching.

Finally, in pre-Reformation England (and, I presume, elsewhere in western Europe), belief in the efficacy of magic was found across all social classes and regions. To pick a few examples from Stanmore's book:

In 1390, Lady Constance Despenser, Countess of Gloucester, responded to the theft of a fur-trimmed scarlet mantle by consulting a diviner named John Berkyng, and was so satisfied by the results that she recommended Berkyng to her father, Edmund de Langley, Duke of York, when he lost two silver dishes (pp.16-17)

John of Kent's confessional manual (c.1215) tells priests to ask parishioners if they have used love magic (p.41)

Another early 13th century confessional manual, Thomas of Cobham's Summa Confessorum, relates as fact a woman in Paris inducing impotency in a man by saying a chant over a lock and key and throwing them down separate wells. (pp.92-93)

The Compendium Medicinae, a medical manual written in the 1230s by King John's* personal physician Gilbertus Anglicus, includes a cure for snakebite that consists of saying the Our Father, a Kyrie Eleison and the words "poto pata zene zebete" over the wound. (pp.117-118)

The popular Glastonbury pilgrimage site included a crypt in the Lady Chapel where ill pilgrims would hang a wax effigy of the infected part from the roof and expect to be cured by the time the wax melted (pp.119-120)

... and so on.

*King John was such a disaster that no subsequent kings were named John; hence, he's just John.

I'll link my Witch Trial Fact Sheet, for anyone who wants to read it and to find sources for further reading.

oh btw the existence of real witches with magical powers destroys any commentary toh was trying to make about the witch trials.

because guess what? the witch trials were just a glorified form of misogyny. it wasn't directed towards people with actual magical powers (obviously) or even people with any power or autonomy at all. the witch trials was a way to make sure that women stayed powerless and any attempt to be an individual, outside of social expectations, would get them killed.

so applying all of that to a setting where witches are real and can defend themselves defeats the whole point. yes, these witches are still nice people (mostly) but the commentary about puritan dogma and the witch trials doesn't really hold up because they're mixing it with fantasy. witches aren't an oppressed group, they are not helpless and tortured in the way women were in the era of witch trials.

i think real world social commentary could definitely be applied to a fantasy setting and carried out efficiently, but not in this instance. toh trashes the direct connection between witch trials and misogyny, and makes it seem like people who publicly burned women at the stake or hanged them.. kind of had a point because witches exist and are naturally stronger than human beings. it doesn't matter if the witches are good or not because this is no longer an act of discrimination and oppression, as it was in the real world.

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

BRUXAS NA IDADE MÉDIA: A VERDADE POR TRÁS DAS ACUSAÇÕES

Dezenas de milhares queimaram sob a acusação de bruxaria. Haveria algo de real por trás do pânico?

RAPHAEL TSAVKKO PUBLICADO EM 07/08/2019, ÀS 09H00 - ATUALIZADO ÀS 21H00

Já entrado nos 50, o burgomestre (prefeito) de Bamberg estava em profunda depressão quando decidiu passear pelo campo de sua propriedade. Sentou-se no chão para chorar. Então foi interrompido por uma estranha aparição, um súcubo, um demônio que se fantasia de mulher para seduzir os homens. Que então perguntou por que estava tão triste. Ele respondeu que simplesmente não sabia. Então a criatura se aproximou. E se transformou num bode, que falou: Agora você sabe com quem está lidando.

O bode exigiu a Johannes Junius — esse era seu nome — que se entregasse a ele, ou seria morto. O burgomestre gritou “Deus, me salve disso!”, e o monstro sumiu. Apenas para retornar com mais demônios. Junius então cedeu, negou a Deus e passou pelo batismo negro. Depois disso, uma rede de satanistas na cidade de Bamberg se revelou a ele, e o convidou a celebrar sabás negros.

A história acima Junius contou a seus inquisidores, em 5 de julho de 1628, após uma semana sendo pendurado pelos punhos com as mãos para trás, tendo os dedos apertados até sangrarem, e as pernas pressionadas até quase seus ossos se partirem. Segundo ele próprio, na carta final à sua filha, apenas uma história que ele inventou para parar o suplício.

Junius sabia o que os caçadores de bruxas queriam ouvir. Sua colorida narrativa foi aceita como realidade. Mas seus acusadores não estavam satisfeitos. Queriam nomes, quais eram esses satanistas que encontrou, ou haveria mais tortura. E nomes ele teve de dar.

Foi por essa mesma armadilha viciosa que o próprio Junius havia caído. Sua esposa e um amigo o haviam denunciado antes de queimarem. Bamberg arderia por mais três anos, até que a população começou a questionar o tribunal, pois ninguém estava seguro. A loucura terminaria quando tropas protestantes invadiram a cidade, em meio à Guerra dos 30 Anos.

Ninguém esperava a inquisição

O prefeito em desgraça não era o caso mais típico — ele era homem e rico. A grande maioria dos até 100 mil mortos acusados de bruxaria era de mulheres, muitas delas pobres.

Bruxas, mulheres com poderes mágicos e más intenções, são parte do folclore de quase todas as culturas, dos astecas aos zulus. Na Europa, em meio ao declínio do feudalismo, a partir do século 13, inicia-se um processo de êxodo para as cidades, que duraria séculos, acompanhado por uma série de revoltas camponesas por toda a Europa, que alteram a relação entre servos e senhores feudais. E a relação das mulheres com as normas sociais vigentes.

À medida que os camponeses passam a conquistar mais liberdades — seja passando de uma relação feudal a uma relação dinheiro-aluguel, seja funcionando como contratados, e não como semiescravos a serviço perpétuo de um senhor —, as mulheres passam a conquistar mais liberdades também. O que não necessariamente significava uma vida materialmente melhor, pois com ela vinha a perda de garantia de alimentos e moradia. Daí as revoltas.

O processo de substituição do modelo feudal pelo capitalista, como explica a historiadora ítalo-americana Silvia Federici em seu livro Calibã e a Bruxa: Mulheres, Corpo e Acumulação Primitiva, levou ao êxodo das aldeias para as cidades e, nesse ínterim, mulheres começaram a exercer funções e profissões para além das casas e terrenos familiares, seja como pedreiras, seja até mesmo como cirurgiãs. E comumente como prostitutas. Essa aparente liberdade das mulheres, que mesmo exercendo em geral atividades inferiores estavam menos sujeitas ao controle dos homens, não passou desapercebida pela Igreja.

A Inquisição havia nascido no século 12 como forma de eliminar heresias como o catarismo e o valdismo. Mais de um século depois, passou a olhar para a bruxaria como uma forma de heresia. Até então, muitos dos próprios papas poderiam ser acusados de tal prática, dado o enorme interesse de alguns deles pela alquimia e pura e simples magia.

As primeiras medidas que dariam início à Inquisição começam a ser postas em prática em 1184 com o papa Lúcio III (a chamada Inquisição Episcopal). Com o papa Inocêncio II acontece a primeira cruzada inquisitória, contra os cátaros (também chamados albigenses), em 1198. O Tribunal do Santo Ofício, ou a Inquisição Papal, é criado oficialmente em 1229-1230 pelo papa Gregório IX durante o Concílio de Toulouse. Em 1320, finalmente, o papa João XXII inclui a bruxaria no hall de heresias.

As bruxas passam a ser o alvo preferencial da Inquisição a partir do século 14, após o surto de Peste Negra, que dizimou um terço da população europeia e foi lido por líderes religiosos como uma forma de punição pela leniência a heresias e comportamentos não cristãos. Obra indireta e direta de bruxas e magia negra.

O best-seller assassino

A criação da prensa de Guttenberg é comumente vista com um instrumento de elucidação das massas. Uma visão idílica. Veja o caso do clérigo católico Heinrich Kramer. Em 1487, ele lançaria Malleus Maleficarum. Um livro que deveu seu sucesso ao revolucionário método de reproduzir livros e, por dois séculos, o segundo mais vendido na Europa após a própria Bíblia.

É um guia de caça às bruxas e heresias afins. Nele, Kramer endossa o extermínio, valendo-se de detalhadas análises legais e teológicas, louvando a prática da tortura para obter confissões. E, um ponto central, afirma que mulheres têm tendência natural a se tornarem bruxas.

O Malleus, diz Diarmaid MacCulloch no livro Reformation: Europe’s House Divided, foi escrito como uma forma de vingança e autojustificação por Kramer ter sido impedido de levar adiante um dos primeiros processos contra bruxas na região do Tirol. Kramer foi expulso da cidade de Innsbruck e, após apelar ao papa Inocêncio VIII, este lhe atendeu com uma bula, em 1484, a Summis Desiderantes Affectibus, que lhe garantia jurisdição para atuar na Alemanha.

Até a publicação do livro, a bruxaria era considerada um crime menor, punido com castigos físicos diversos. Uma esquisitice folclórica de velhinhas mal-orientadas pelos padres. Após a publicação do Malleus, autoridades católicas e protestantes passaram a usá-lo no julgamento e condenação de suspeitas de bruxaria, tornando mais brutal a perseguição.

O livro não era usado por inquisidores, mas sim por tribunais seculares, em especial durante a Renascença. Quem queimava os acusados de bruxaria era o Estado, não o clero — o governo da Espanha, Portugal, dos vários Estados alemães etc. Só nos Estados Papais, onde a Igreja também era a autoridade secular, a Inquisição tinha poder para executar — como no célebre caso do teólogo Giordano Bruno, que queimou em Roma, em 1600.

Simpatia pelo Diabo

Não era só a negação a Cristo que movia a fúria contra as bruxas. O escândalo andava de mãos dadas com a fé em ceifar vidas inocentes.

Acusações de sexo com demônios eram lugar-comum durante o auge da perseguição à mulheres consideradas bruxas, entre os séculos 14 e 17, uma época em que sexo era um tabu, como conta o historiador David M. Friedman, em Cultural History of the Penis.

Não era incomum que os juízes nos julgamentos das bruxas exigissem detalhes minuciosos das alegadas práticas sexuais. Quanto mais inventivos os atos, maior a sensação nas seções de tortura a que submetiam as acusadas e que prenunciavam o auto de fé.

Além de curandeiras, aquelas mulheres que não seguiam à risca normas sociais da época (como se portar de maneira recatada, obedecer aos pais e marido etc.) eram alvos dos inquisidores, assim como as mentalmente insanas ou perturbadas. Ou, sem fazer nada, as que tivessem o azar de serem denunciadas por inveja, ciúme ou, como no caso do prefeito, alguém forçado a dar um nome.

Também escandalosa é a origem do veículo favorito das bruxas, a vassoura. Atestado por múltiplas fontes e em múltiplas receitas, o unguento voador era um composto tradicional alucinógeno feito de plantas venenosas como a mandrágora, a beladona e a figueira-do-diabo. Provável vestígio da era dos druidas, era usado em rituais noturnos, que envolviam vassouras de um jeito peculiar. No julgamento da nobre irlandesa Alice Kyteler, em 1324, é mencionado que as bruxas confessaram besuntar o cabo com o unguento e cavalgá-lo até o ponto de encontro, ou ungirem-se nas axilias e em outros locais peludos. Não ria. Alice foi queimada viva.

Histeria e Hecatombe

O livro European Witch Trials: Their Foundationsin Popular and Learned Culture, de Richard Kieckhefer, traz uma longa e assustadora lista de julgamentos de bruxas a partir do século 14, como por exemplo o julgamento de 600 pessoas acusadas de bruxaria na cidade de Toulouse entre 1320 e 1350, sendo 400 delas condenadas e executadas. Ou 400 pessoas julgadas e 200 condenadas e executadas na vizinha Carcassonne, na mesma época.

Além das torturas, havia ainda os métodos práticos para encontrar bruxas. O mais comum era o teste da água. Uma mulher era arrastada para um lago ou rio, despida e amarrada. Ao ser atirada, se flutuasse, era bruxa. Se afundasse, eles até tentavam puxar de volta. A explicação é que bruxas repeliam a água por terem rejeitado seu batismo ao aceitarem Satã. Mas não era a única: também disseram que era por serem anormalmente leves. E assim surgiu o teste do peso: se a ré pesasse menos do que se imaginava normal, era bruxa.

A Alemanha do fim do século 16 e começo do 17 viu alguns dos maiores autos de fé registrados na História. Junto a Johannes Junius, pelo menos mil pessoas foram executadas em Bamberg (1626- 1631) e em Trier (1581-1593). Na mesma época, mais 250 em Fulda (1603-1606) e 900 em Würzburg (1626-1631).

No século seguinte, a caça às bruxas se tornou a peça número um da denúncia dos iluministas aos abusos da religião e superstição. Aos poucos, a loucura iria se arrefecendo. A última pessoa a ser morta por acusação de bruxaria foi Anna Göldi, na Suíça. Foi acusada de materializar magicamente vidro e agulhas no pão e leite da filha de Jakob Tschudi, para quem trabalhava como doméstica. Torturada, falou ter feito um pacto com o diabo, na forma de um cachorro preto que se materializou do nada.

A caça às bruxas então já era bem desmoralizada. Göldi foi acusada formalmente de envenenamento, não bruxaria — ainda que a lei não prescrevesse pena de morte para tentativa de envenenamento. Era 1784, oito anos após a morte de David Hume, seis anos da de Voltaire e Rosseau, um após a de D’Alembert e o mesmo da de Diderot, filósofos anticlericais que dariam origem ao jeito moderno e secular de pensar. Antes do fim do século, em 1798, os Estados Papais seriam capturados pela França, restaurados em 1800 e novamente capturados sob Napoleão, em 1808.

O total de mortos por acusações de bruxaria desde a Idade Média é controverso. A cifra mais baixa, 35 mil, é defendida pelo historiador William Monter, da Northwestern University (EUA). Em seu livro Witchcraze (sem tradução), de 1994, a historiadora Anne Llewellyn Barstow chegou a 100 mil.

¿Las Hay?

Mas, afinal, tudo isso foi mesmo por nada? As bruxas existiam? A resposta é sim. Havia de fato satanistas na Idade Média. Ao menos um caso é bem registrado: o dos luciferianos, um grupo derivado dos cátaros que viveu na Alemanha do século 13. Acreditavam que Satã havia sido injustiçado e na verdade era o lado bom da guerra com Deus.

Mesmo se satanistas reais fossem raros ao ponto da irrelevância, o que não faltava era candidatos a mago. Alquimistas ganhavam fortunas não só por fórmulas como por rituais secretos. Os grimórios, livros de feitiços, circulavam por mãos cobiçosas por toda a Europa. O Grimório de Honório, do século 13, era atribuído a um papa. Ele ensinava como escapar do purgatório e invocar demônios, entre outras.

A diferença entre alquimistas e bruxas é que os primeiros eram homens, ricos, educados e próximos ao poder, conselheiros de reis e papas, justificando sua atividade como uma manipulação da natureza. As bruxas eram conhecedorasde ritos e poções de tempos pagãos, sem entender como isso poderia ser visto como adoração a Satã.

Como os alquimistas, todas (ou quase todas) deviam se ver como boas cristãs. Certamente, algumas delas e alguns deles usaram seus poderes — bem reais, no caso de venenos — para o mal. Mas quem teve uma vovozinha tradicional, daquelas que fazem rezas, simpatias e garrafadas, conheceu a bruxa típica.

Fonte: Aventuras na história

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 52 of 100: Days of Productivity

Tasks:

Went to a really interesting program about Dual Enrollment at 3 FL universities

Finish writing a Hamilton parody about the Bamberg Witch Trials (not gonna lie, it slaps)

Took 10 pages of typed AP Euro notes on Absolutism and Constitutionalism

Went out on a walk (it was only like, a quarter of a mile to pick up my brother, but it was nice to be outside)

Worked on my Long-Term Drawing project

Reviewed for my Algebra quiz retake

Reviewed Indirect and Direct Object Pronouns for Spanish

To Do:

Chemistry work that I missed 'cos of the DE program

Finish Long-Term Drawing

Present Bamberg Witch Hunt/Hamilton project

Mid-Chapter 1 Retake

Talk to Mr. Pauling about the 4-6 Vocab Test

Work on the Scholastic Writing Science Fiction short story

Finish the city drawing project

Take some extra studyblr pictures

Finish AP Euro Chapter 15 Notes by Wednesday

AP World Chapter 17 Notes due Tuesday

History Bowl Work tomorrow night

Currently Listening to Don't Lose Your Head from Six

10 October 2019

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part 5: Wrapping Up Europe

(Holy Roman Empire)

I am not gonna lie, that last section exhausted me. It took some time to get back into a researching worthy headspace. Regardless, this section will be much shorter and will put us up to speed so that we can end with the Salem Witch Trials, and perhaps some modern witch hunts and why that terminology is confusing for the U.S. President to use.

These next trials have casualties numbering in the thousands and occur during one of history’s most tumultuous time periods. Beginning with the Würzburg Trials in 1626, the executions lasted through 1631 with only 219 taking place within the city proper. By comparison, Bamberg, a city with the largest death count, numbered in the thousands. A bit of background before we dive in—the Holy Roman Empire (800-1806) encompassed much of central and western Europe, including all of what is now Germany. During the late 16th/17th centuries the world experienced a period of atypically cold temperatures that caused crop failures, deep freezes, poor survival of livestock, and a higher risk of disease. This is referred to as The Little Ice Age, and as you can imagine pushed tensions to a precipice and made people suspicious. Quickly, all of the calamity that had befallen the common man was blamed on the mystical, and it was believed that only a supernatural force could account for the loss a normal way of life. As we progress through a few decades, there were sporadic executions for witchcraft under each prince-bishop’s rule in Bamberg; however, the real trouble starts with Johann Georg Fuch von Dornheim in 1626. One night a severe frost decimated crops and livestock in a large area, and the slowly fizzled-out witch hunts resumed their prior intrigue—this time with a few major changes. Times were tough, and officials needed a better way to execute witches without wasting precious firewood, so a large crematorium was constructed in the epicenter of the executions. Additionally, Bamberg constructed a large prison to house the insurmountable number of accused. The prison called a Drudenhaus or Malefizhaus, were large structures built with single cells for individuals as well as larger cell sections that could house larger groups of prisoners. The structure in Bamberg, has been all but completely destroyed in our current time, and we have little information on what it actually looked like, but what we do know comes from prints that were illustrated within a pamphlet distributed during the time of the executions. In the prints we can see some of the layout of these prisons as well as some inscriptions on plaques above the entrance.

“And at this house, which is high, every one who passeth by it shall be astonished and shall hiss; and they shall say, ‘Why hath the Lord done thus unto this land and to this house?’

9 And they shall answer, ‘Because they forsook the Lord their God who brought forth their fathers out of the land of Egypt, and have taken hold upon other gods, and have worshiped them and served them; therefore hath the Lord brought upon them all this evil.’”(1 Kings 9:8-9)

The other passages were in a medieval dialect of German that was difficult to translate, so I did not, but there were also passages from the Bible covering the walls within the hallways. Those accused of witchcraft were held here and tortured. I don’t know if any of this is starting to sound really familiar or not, but it seems to me as if it shares a few similarities to a large-scale genocide that occurred about three centuries after these events.[1]

(Picture Public Domain)

One of the most important sources of information that we have regarding the torture of prisoners is the letter that one of the victims, Johannes Junius, had written to his daughter explaining his confession of practicing witchcraft. He mentions in the letter that he had already been tortured, and that some kindly executioner told him that if he didn’t confess in some way that he would continue to be tortured until it killed him. Since Johannes had already faced severe torture, he decided to take the less painful route and confess to the crimes that he was falsely accused of. In the margins of the note he details that some of his accusers apologized to him because they were also forced to accuse him with the threat of torture.[2] The executions and torture went on for quite some time until the working class began to realize that no one was safe from the accusations which were synonymous with execution at this point, and began to refuse to contribute fire wood, or other important materials that were needed to perform the executions. The final nail in the coffin, after the chancellor of Bamberg himself, was the execution of a wealthy woman named Dorothea Flock. She was the second wife of the city’s councilor whose first wife was also executed for witchcraft. Dorothea’s family quickly tried to have her released and every effort was thwarted. Eventually, her husband entreated the highest council of Germany known as the Hofrat to send release documents to have her taken out of the prison and returned home. However, the witch hunters were tipped off about the arrival of the letters, and they executed Dorothy before they had a chance to be delivered. This did have a positive outcome, though, and the trials were halted pending an investigation by the Hofrat in 1630, leading the Catholic Church to blame the bishop for the issue. There remained a small trickle of executions for two more years until the Swedish Protestant troops arrived in Bamberg and released the remaining prisoners asking that they refrain from divulging information regarding the activities taking place inside the prison walls.

The last European trial I wanna talk about is not so much a trial as it is a giant historical scandal which are by far the most fun topics to research when sifting through a ton of material. It is called the Affair of Poisons, and it took place in France during King Louis XIV’s rule between 1677-1682. This is not a prominent number of casualties; however, it is one of the closest occurrences to the trials that occurred in the American Colonies. I find this particular event especially interesting because this is the only case where some essence of a realistic explanation is the root cause of the accusations and consequential executions. It all began with a tale as old as time—an arbitrary case of a woman conspiring to poison her father and two brothers so that she and her lover could inherit the estates and money. The accused, Marie Madeleine d’Aubray, marquise de Brinvilliers, was a part of a Parisian fad to dabble in the spiritual and exciting aspects of magic, and she visited her regular spiritual councilor to procure the poison that she used to murder her family. Often this popular fad would include seances, fortune-telling, and love potions that were very très chic at the lavish parties that the French aristocracy was widely known for, and its popularity spanned the gap between classes including bourgeoisie and poorer peoples of France.

The fun was short-lived, however, and Marie’s trial drew a lot of attention and spurred the anxieties of other nobles who were afraid something similar might happen to them. A special court was instituted to help quell these panic-driven accusations. Known as chambre ardente, or burning court, the court held 210 sessions over three years and issued 319 arrests.[3] Once fortune tellers were arrested for providing poisons to murderers, they gave up lists of their clients—these lists gave no distinction between those who might have had a spiritual reading versus those that had purchased a poison with the intent to murder someone. The most famously known execution is that of Madame Monvoisin, whose client list included marquises, family of clergy members, military heroes, and many more of France’s most elite members of society—including, Madame de Montespan, mistress to the king. Montespan was accused of having won the king’s love via potions and other nefarious and manipulative magical means, but it is important to note that she was interrogated while intoxicated and was never proven to have taken part in these dealings. The tribunal that was established to deal with these cases is notable because it is one of the only witch hunts to have been conducted so professionally, and with far less of the hysterics that were typical of other trials on this scale. There were only 36 people sentenced to death and many others were not even brought to trial.

So concludes our European adventures, and I think that we can without a doubt say that it doesn’t even begin to end there. There are still so many other cases that I didn’t look into because of the sheer amount of information that needed sorting through, but I hope that the important information about this topic was conveyed clearly and in a memorable way. I know that I certainly learned a lot from this part of the project, and I’m looking forward to finishing it with the conclusions we can draw, the historical implications of these events, and the parallels that we can draw from these events that reflect on recent and current events. See you guys in America circa 1692!

[1] That would be the Holocaust that I’m referring to here. You know, the one where they built prisons that they tortured people in on massive scales? Wait, wasn’t that about religious intolerance too? It’s almost like it’s always about religious intolerance….weird

[2] (History Muse, 1628)

[3] (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2010)

#witches#witchcraft#witch trials#european witch trials#bamberg#bamberg witch trials#the affair of poisons#king louis xiv#france#germany#madame monvoisin#history#european history#the little ice age#early modern period#holy roman empire#itshistoryyall

0 notes

Note

I do indeed! I did a pretty extensive dive into witch trials in Western Europe and North American back in 2021 as part of a study on the history of witchcraft-related laws and how they changed over time.

The thing about witch panics and witch trials is that they are, historically speaking, never about witches as we would define the term today. (This also holds true for current issues facing many countries in South America, Africa, and South Asia today.) Sure, we have the witch-cult hypothesis that Margaret Murray popularized, which claimed that Western European witch trials were the result of the Church trying to stamp out the remnants of a pre-Christian feminist pagan cult, but that was fringe theory even in its' heyday and has since been thoroughly debunked.

What we do know from the historical record is that charges of witchcraft were often bound up in superstition, religious zealotry, politics, or some combination thereof. There was never one single cause of a witch panic, only prevailing factors such as hardship, war, famine, poverty, or political instability that made conditions ripe for fear and scapegoating. While it's true that the victims of the most well-known trials were largely women, and that superstitions regarding witchcraft sometimes skewed along gender lines, any social or political other and anyone disadvantaged by poverty, illness, disability, or reputation was at risk.

One might point in particular to the Bamberg Witch Panic in Germany (1627-1632) and the "Great Noise" in Sweden (1668-1676) wherein men and women alike were accused of and executed for alleged witchcraft, with no protection given for gender, class, or age. Even in the famous Salem witch trials in the United States (1692-1693), six of the twenty people who were executed were men. (Personally, I consider Giles Corey's death by torture an execution.)

Many witch trials between 1500-1700 were also bound up in ongoing political struggles between the Catholic and Protestant churches. During this time, we often see accusations witchcraft bundled in with charges of heresy or treason, particularly in high-profile cases. Many times, the alleged crime of the accused person wasn't the practice of witchcraft or the observance of pagan customs as we know it today, but simply being part of a religious denomination that was out of favor or in conflict with the current monarchy in their country, with the prevailing opinion gradually shifting to a firmly anti-Catholic stance.

And, because it needs to be said, rampant anti-semitism played a role in these trials as well, just as colonization and the intrusion of evangelists have played a role in modern witch panics. (These things are not the same, but they bear mentioning.)

The modern witchcraft movement began around the same time as first-wave feminism, so the cultural and political tenets of the modern witchcraft community have been bound up with it from the start. This intensified when both movements gained speed around the mid-20th century and revisionist pseudohistory sought to make feminist pagan martyrs of thousands of people who never would have identified themselves as witches.

Until the rise of modern paganism, the word "witch" was pretty much universally regarded as a pejorative, an insult, something one would never want to be called. There were actual legal statutes that allowed people to take their neighbors to court for slander over being called a witch in public, since the word was so heavily charged with negative associations that it could lead to social ostracization, harm to a business, or even legal charges. (In the case of Grace Sherwood in 1705, prior accusations of witchcraft were considered as evidence during her trial, even though she'd sued for slander on three separate occasions and won twice.) In much of the world, the word retains a negative connotation.

As OP noted above, there is a lot of terfy bullshit wrapped up in the view of past victims of witch trials as mostly or entirely female, and the idea that witchcraft accusations were something that only happened to women as a tool of patriarchal oppression. "We Are The Granddaughters Of The Witches You Couldn't Burn" is a catchphrase that grates on me like sandpaper on a sunburn, as is the ridiculous insistence by certain bigoted sections of the community that only "real women" can be witches.

So to bring it back around to Anon's original question, the victims of witch trials are now, as they were then, not actual witches. They're just whoever is convenient. Whoever is ostracized, whoever is othered, whoever is not in favor, whoever makes the best scapegoat for a community's fear and paranoia.

Like I said at the top of the post, witch trials are never about witches.

(If you'd like to know more, I've talked about the history of witch trials and the witch-cult hypothesis a few times on my podcast, Hex Positive. You can check out Eps. 20-21, "Witchcraft and the Law" / "Witchcraft and Modern Law" and Ep. 36, "Margaret Effing Murray" for more information.)

Hi miaro... I wanted to ask you about witch craft...

I was reading a book on feminism recently, I read something on how women where harmed in the europe during medieval times as "witches and evil" And beaten up and killed by a mob, and how even in these days especially in South Asian countries people harm women and kill them calling they are "witches" And harm people and stuff...

But the book tried to dismantle it by saying how due to extreme poverty and food shortages and climatic conditions, people were not capable of providing themselves and their families basic necessities and in order to reduce the competition they used to target women esp who are old and single, widowed, sick by calling them witches and by spreading fake news about how they harm others....

The book didn't focus on the witch craft but only on exploitation of women...

So who are these "witch" Like what's their true identity like? You have mentioned in your bio that you are training so i thought you would be a better person to answer??

Most likwly these witches were never witches. If you take England for example, King James had a huge thing agaisnt witches, to the point of altering the bibles translation.

Just as the book said, they were likely harming widowed, older women or spinsters. Especially if those were of a different religion (think catholics vs protestants, folklore believers etc).

I dont know about South Asia, but currently in Madagascar , there is quite an ambivalence about witchcraft. There are thee types of witches (healers, astrologers/divinatory, maleficient) in our folk beliefs. But with colonization, poverty etc opinions have shifted towards a more Christian one, so people can become more and more reluctant to follow their traditions of asking a witch to check the the ghosts of your ancestors are okay withvyou moving in for example. There is a real fear about witchcraft.

There is a lot of misinformation about the subject in general, as it has been altered a lot by white witches, terf witches etc.

I think @breelandwalker must know more about this ?

49 notes

·

View notes