#baba yaga bony leg

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The iron-toothed crone with a leg of bone that dwells deep in the woods, Baba Yaga is said to steal and eat young children.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#myth#mythology#fairy tale#baba yaga#baba jaga#baba yaga of the iron teeth#baba yaga bony leg#witch#slavic folklore#slavic fairy tale#crone#hag

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Firebird - Chapter 11

Pairing: Prince Paul (Catherine the Great) x OFC, Fairytale AU

Summary: When Paul, a spoiled young prince, spots a strange bird in the forest near his palace, he impulsively chases after it, hoping to both escape from and prove himself to his disapproving mother. Thus he is plunged into an exhilarating adventure across a magical realm populated by enchanted princesses, dangerous monsters, and powerful wizards, an adventure that may change him more than he can ever imagine.

Chapter warning: none

Chapter word count: 3k

Chapter 1 - Chapter 2 - Chapter 3 - Chapter 4 - Chapter 5 - Chapter 6 - Chapter 7 - Chapter 8 - Chapter 9 - Chapter 10

Chapter 11 - The House on Chicken Legs

It was the strangest sight Paul had ever laid eyes on since his arrival in Lukomorye, and considering he'd seen some pretty strange sights, that really was saying something. An iron mortar was flying into the clearing, carrying inside it an old woman, all bones and sagging skin, with a nose so long and hooked it almost touched her upper lip, a head of stringy white hair, and eyes that glinted within deep sockets under bushy brows that reminded him of a leshy's eyes. She was driving the mortar by beating it with a pestle in one hand, and in the other hand, she held a broom, which she used to sweep away her tracks. It seemed to Paul a rather cumbersome mode of transportation, but Baba Yaga—for he had heard enough tales of her to recognize her on sight, even without an introduction—clearly found it quite efficient.

The mortar stopped, and Baba Yaga stepped off. Her gimlet eyes bore into the four of them, searching, measuring. They all involuntarily cowered, even Ilya, who lowered his bow with an uncertain frown. At this closer range, Paul realized that Baba Yaga's eyes weren't quite like a leshy's. He couldn't tell what color they were, only that they were dark, sharp, and profound—not just physically deep, but containing unfathomable wisdom and age. It was rather like being gazed at by an abyss.

"Well, well, well," Baba Yaga said. "What do we have here? Three Lukomorians and a Russian! By Perun, we are eating well tonight!"

Zhara gently extracted her trembling hand from Paul's and stepped forward. "Please, grandmother," she said, bowing low. "I am Zhara Artyomovna of—"

"I know who you are, girl," Baba Yaga interrupted. "I know who all of you are, except for this one"—she pointed a bony finger at Paul—"but what I don't know is, what you are doing here."

"Please, we don't mean to trespass," Zhara said. "We're here to most humbly ask for your help."

"Help? To bring down your brother?" Seeing their surprised looks, Baba Yaga chuckled. "Yes, I know all about your brother and his scheme, girl. What's it got to do with me?"

"What's it got to do with you?! How could you ask such a thing?" In her shock, Zhara forgot her diffidence and raised her voice. "If my brother gained immortality, he would crush Lukomorye! He would destroy everything, including you!"

Baba Yaga's eyes glittered strangely. "That is not immortality he is striving for," she said. "He is only trying to cheat Death, and believe me, you cannot cheat Death for long. As for destroying me... I am older than these trees around me, older than the river running through that meadow, older than those hills there, older than the land itself. Whatever he can do to me, I shall welcome it." Her words sounded like they were coming from far, far away, and Paul shivered.

"Please, grandmother, you're our only hope—" Zhara said, extending her hands toward Baba Yaga imploringly.

"It is foolish to hope," Baba Yaga said, as cold and unyielding as a mountain. "There is nothing I can do for you."

Zhara looked back at her companions with eyes full of despair. At the sight of her tears and her trembling lips, Paul forgot all his fears. He would not let anyone treat her like this, not even if that person was—well, even if it was his own mother. He could not.

"Come, Zhara," he said, taking her elbow and guiding her away. "Don't degrade yourself. We must have made a mistake. She's clearly not Baba Yaga."

Zhara frowned at him, not understanding.

"What did you say, boy?" the old woman snapped.

He turned around to face her, trying to conjure up his usual expression of contempt, the one he often wore around his mother's lovers or the other sycophants that clung to her skirts. "Well, at least you're not the Baba Yaga that I have heard of back in Russia," he said. "That Baba Yaga was all-powerful and would never stand for any threats, not running away at the first mention of danger like some dotty old bird."

Zhara gasped. Even Ilya and Elena widened their eyes, shocked at such blatant impertinence. Baba Yaga was upon Paul in a flash, her skinny, claw-like hand closing around his throat.

"I know what you're trying to do, boy," she growled. "Think I could be fooled by such a childish attempt to rile me up?"

The horse with the golden mane chose that moment to trot over, perhaps because it was bored with the grass that Baba Yaga's woods had to offer, or perhaps because it noticed that Paul, to whom it had taken a strange liking, was being threatened. The sight of the horse made Baba Yaga drop Paul's neck instantly.

"Is that you, my Voskhod?" she said, her voice becoming tender as she reached for the horse in disbelief. "You have come back to Baba?" The horse gave a soft whinny and rubbed its nose against Baba Yaga's calloused hand. She turned to Zhara and her companions. "Ever since Afron stole him from me, I never thought I'd see him again. What happened to that slimy bastard, by the way?"

"Dead," Ilya said.

Baba Yaga cackled, sounding like she was gargling with a mouthful of rocks. Once she sobered up, she looked at Zhara again, and Paul thought the old woman's eyes softened somewhat. "Since you and your companions have returned my little Sunrise to me, I owe you. My offer is this: I shall take you wherever you wish to go and lend you whatever aid I can in your fight against your brother, but I shall not take part in that fight myself. What is between you and your brother, you must face on your own. Is that understood?"

Zhara almost fell to her knees with relief. "Yes! Thank you, grandmother!"

"Don't thank me just yet," Baba Yaga grumbled. She turned to face the woods and chanted, "Little house, little house, stand the way thy mother placed thee, turn thy back to the forest and thy face to me!"

There was a great rustling sound. The trees shook and groaned, the birds roosting in their tops shot up into the sky, squawking in complaint about being roused from their sleep, as some huge creature moved through the forest. But it was no creature. It was a hut, moving on a pair of chicken legs.

The sight of the hut, so familiar to him from the old tales, made Paul almost laugh out loud in delight. It walked into the clearing, sat down in front of Baba Yaga by folding its chicken legs underneath, and became an ordinary izba.

Or perhaps not quite so ordinary. A little lawn, complete with a fence surrounding it and a gate, had spread out around the hut, but these were not the usual wooden fences and gates. They were white, bone white, for indeed, they were made from human bones—long leg bones for the fence posts, topped with skulls, shorter arm bones for the crossbars. The gate was locked with a set of jaw-bones, sharp teeth still intact. As soon as the hut sat down, an eerie light shone out from the eye sockets of the skulls, illuminating the entire place. Three horses, the white and black they had seen, along with a red one—not chestnut, not bay, but true red, as red as Zhara's plumage—stood grazing on the lawn, under the shade of a great linden tree, quite unfazed by the ghoulish barricade.

"Ho! Ye, my solid locks, unlock! Thou, my stout gate, open!" Baba Yaga shouted. The locks sprang open with a horrible clicking sound, and the gate swung wide on hinges made from the bones of human feet.

The moment the gate opened, the horse with the golden mane, Voskhod, trotted through and joined his family on the other side. They all welcomed him, happily snorting and rubbing their noses into his mane.

"Those are my Night, Day, and Sun," Baba Yaga said proudly. "Sun is Voskhod's mother."

The humans were much more hesitant to enter. Paul followed the others as Baba Yaga led them inside, afraid he was going to find more gruesome things. To his great relief, it was a perfectly normal izba with its warm stove and simple, sturdy furniture. A mouth-watering smell of fresh baked bread was coming from the stove, and the travelers, their fear and suspicion overcome by the exhaustion of the last two days, sat down at the table to join the most fearsome witch of all the lands in a nice, cozy supper.

But the most extraordinary thing about the house on chicken legs was still to come.

After supper, Baba Yaga barked, "Well, where are we going, girl? Where is your brother?" In a halting voice, Zhara told her about Buyan Island. The old witch nodded solemnly and hit the ceiling with her broomstick a few times, mumbling something under her breath. There was a slight movement, and they felt the floor rise beneath them as the hut unfolded its legs again. This done, Baba Yaga climbed up on the stove to sleep, apparently satisfied, leaving the others to exchange puzzled looks. Then Paul glanced out the window, and his jaw dropped. Following his gaze, the others rushed to the window, and they, too, widened their eyes at the sight.

The landscape was rushing by, as it had when they were on Voskhod's back. The forest was a dark smudge, while the stars were shards of light glancing off of the skull-and-bone fence. However, the lawn with the horses on it and the fence around it remained stationary, and the hut didn't seem to be moving at all, giving the impression that the world was traveling past them instead of the other way around—and perhaps that was exactly what was happening. After a while, Paul felt rather queasy looking at it, so he turned away.

The hut traveled for most of the night, only stopping to rest at dawn, when the horses left to herald the day. They galloped out of Baba Yaga's pasture in reverse order—first Night, then Day, and finally Sun, leaving only Voskhod behind. The skull's eyes went out, and sunlight poured over the lawn like honey. Paul stood by the window, transfixed by it all. Zhara, now in her avian form, hopped about on the windowsill next to him, and he stroked her head and her wings almost absently.

"I can't thank you enough for allowing me to witness such magic," he said, and she gave a little chirp, sounding pleased.

And so it went with the house on chicken legs. It traveled through the land, sometimes fast, sometimes slow, but always moving forward. Paul, Elena, and Ilya worked around the house, and Zhara helped when she could. Paul, who had never had to lift his hand, not even to tie his own cravat, now had to get used to all sorts of manual labor—cooking, washing up, sweeping the floor, cleaning the yard, chopping firewood—but he dared not complain, not when he saw the two princesses and the knight working at these menial tasks as though it was the most natural thing for them to do. None of them ventured outside the bone fence. Baba Yaga was the only one that went out. Most mornings, she left in her mortar, though they knew not where and dared not ask. She left the larder and the cellar well stocked, and Ilya, who turned out to be the best cook of them all, made sure to have supper on the table by the time she returned.

Despite this peaceful routine, life inside the house on chicken legs was not exactly happy. For one thing, Elena remained sorrowful over Dobrynya and would sit for hours in the yard or in front of the fire, staring at nothing. One night, when it was their turn to clean up after supper, Paul whispered to Zhara that he didn't understand why Elena could grieve so much for someone she had only known for a few days.

"You once told me yourself, we cannot decide who we fall in love with," Zhara said with a shrug. "The heart wants what it wants."

Does your heart want me? Paul wanted to ask, but he bit his tongue and held his peace. It was not the time to speak of matters of the heart. Zhara always seemed distracted these days. Paul supposed that the closer they got to her brother, the more tangible the battle ahead became to her, and she could think of nothing else. He wouldn't have worried, except that she ate little and slept even less. As a bird, she would flit about the house or jump from branch to branch on the linden tree in the yard, never staying still, and at night, she would stand by the window looking out. Sometimes, waking on his cot in the corner of the room in the middle of the night, he would see her at the window, gripping the frame white-knuckled, as though by doing so she could make the hut travel faster. His attempts to persuade her to save her strength hadn't been successful, and he could only pray that they reached Buyan soon and face Illarion once and for all.

The only one who remained busy and cheerful was Ilya. He spent his days sharpening his sword, oiling his mace, and fixing and recounting his arrows, trying to see if he could make them last. He had even started to teach Paul how to use the spear, and Paul gained much more sympathy for his soldiers, who'd had to suffer through his drilling exercises.

Some days, Baba Yaga stayed home or returned earlier than usual, and she would watch their work with that same inscrutable glint in her eyes. One night, seeing Elena take off the poultice on Paul's wound, which was completely healed by now, the old witch said, "You have a talent, girl."

Elena blushed. "Thank you. Ever since I was a child, I've always had an interest in healing plants and herbs, and it just comes natural to me..."

"I'd say." Baba Yaga scratched her warty chin, looking thoughtfully at Elena. "How would you like to stay with me and learn more of the art? I could use a helper around the house too."

"Oh, that would be a great honor!" Elena said, her face brightening up for the first time in days. "Thank you, grandmother!"

Another day, after watching Ilya count his arrows again and again, Baba Yaga grunted and went digging in her trunk. She came up with a quiver, which she tossed to Ilya. "Put your arrows in that," she said, "and you shall never run out."

Ilya tested it, and indeed, any arrow he loosed from his bow would return to the quiver a moment later. "I've heard about this!" he said in amazement. "It belongs to Svyatogor the Giant—or used to, anyway. How did it come to be in your possession?"

"I won it, a long, long time ago," Baba Yaga said, her eyes darkening with some distant memory.

Something in her voice, in the way she looked at the quiver, lit a spark of suspicion in Paul's mind. He remembered how adamantly she had refused to help them, and how, in all the days they stayed in her house, they had never seen her perform any feat of magic other than controlling the hut—and even then, the hut seemed to have a mind of its own.

He followed the witch outside, where she sat polishing her mortar and pestle under the linden.

"You don't have any powers, do you?" he asked. "Not any that counts." He was surprised at his own brazenness, but if Zhara was placing her trust in the wrong person, he felt he ought to find out and warn her.

"You're sharp, aren't you?" the witch said without looking up. "So tell me, Russian boy, how do you know which power counts and which doesn't?" When Paul couldn't answer, she gave a little chuckle but didn't seem angry or offended. "Make no mistake, I may not have as much power as I used to, but I still have it."

"What do you mean, 'not as much as you used to'?"

She finally lifted those unfathomable eyes to his face. Harsh lines scarred her features. "You boys, always think of powers that control and destroy. I used to have those as well, until they were taken from me... by my brother."

"Your brother?"

"Koschei."

Paul's mouth dropped open.

"Koschei is—was your brother?"

"Yes, why do you keep repeating everything I said, boy?" She sounded irritated, rather like one of his old nurses or tutors when he kept pestering them with his questions about his father's fate or his mother's coup. "He took my powers from me in his quest for immortality. And look where that led him. Bested by a child. Pathetic."

Her reveal left Paul speechless.

"But—" he stammered, once he regained his train of thoughts, "if Koschei took those powers from you, and Illarion took those powers from Koschei, why do you refuse to help us defeat him? With Illarion gone, you can reclaim your powers!"

"And what would I want with them?" She shrugged. "I have the power to drive my mortar whenever I want to go. I have the power to protect my house and those in it. Don't they count?"

Paul thought about it. "Are they enough?" he asked.

Baba Yaga shook her head, her dark, dark eyes looking at Paul with something almost like pity. "If you think of power that way, nothing will ever be enough, boy." She went inside, leaving Paul to mull over those words.

Chapter 12

There will be a bit of smut in the next chapter. It's non-explicit, as usual with me, but I thought I'd give a heads-up anyway!

Taglist: @ali-r3n

#prince paul#tsarevich paul#catherine the great#prince paul fic#prince paul x ofc#joseph quinn#joseph quinn fic

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Yaga journal: The road to the otherworld

Baba Yaga as depicted in Mike Mignolia’s “Hellboy”

The first article of this journal was written by Natacha Rimasson-Fertin, and its full title is (when hastily translated by me): “The Baba Yaga on the road to the other world: a crucial meeting for the hero of the fairytale”. As I said previously, I will merely summarize the article and recap some of its important points.

Every reader of Russian fairytales is familiar with the famous chicken-legged isba, the home of the Baba Yaga. But where exactly this home is located is however quite unclear - its position seemingly changing from tale to tale. This article relies on the fairytales collected by Afanassiev to study the places typical of the fairy tales, the travel the hero must undergo to reach the hag, all to try to locate the mysterious but iconic lair of Baba Yaga - which, in hope, will help clarify her “true function and identity”.

It should be mentioned that, while the article focuses on tales about “travelling heroes”, it does mention the existence of another handful of tales where it is the Baba Yaga that invades the world of the humans - it is tales such as “Ivachka” (NRS 108-111) or “The wild geese” (NRS 113). [Note: NRS is the name used to refer to Afanassiev’s classification of Russian fairytales, the same way there is the ATU Index]. And in these tales, the house of the Baba Yaga is not actually located in the “otherworld”, but rather right next to where humans live: by a river side, or in the forest where the heroes regularly go fetch mushrooms. In fact, in these tales, the house of the Baba Yaga misses its chicken legs, and seems to be just a regular isba.

While the reasons for the quests of the heroes in Russian fairytales are varied and multiple, there is a general tendency: heroines usually seek to be set free from something, while the heroes either seek this same “deliverance” or actually seek a wife. In fairytales, space is organized by two oppositions: known and unknown, familiar and foreign/alien. In this context, as Propp highlighted, “the farytale is built around the hero moving in space” - so travel means the breaking of the order of things, and thus a journey is already something extraordinary. In russian fairytales, according to Tatiana Ščepanskaja (in her “The culture of the road in Northern Russia), the road is actually “outside of the divine order” and even opposes this divine order. Traditionally “the road is the world of the non-being, where the custom doesn’t work. By taking the road, the individual is out of the community, he escapes the world of social workings - there is punishment, no public pressure, but also no encouragment and no glory. On the road, one is alone and free, outside of community and its norms.” So the man who travels lose all status - he doesn’t belong to the human society, but to the “other world”. On the road, one leaves the protection of their ancestors behind, and open themselves to numerous dangers - this is why many heroes of Russian fairytales always ask the blessing of their parent before going on the road.

The road itself, as an “open space” is the world of all possibilities. In the last verson given by Afanassiev of the fairytale “Go I don’t know where, bring back I don’t know what” (NRS 212-215), the hero, after hearing that the Baba Yaga wants to eat him, mentions his status as a traveller “Why, you old devil! How could you eat a traveller? A traveller is bony and black, first heat up the tub and bathe me - then you’ll eat me!”. The bathing ritual itself is also a rite of passage.

The frontier of the otherworld is of various natures, depending on the tale. Usually it is a clearing in the woods, which forms a typical liminal space. The Baba Yaga is closely tied to forest, her house often being at the heart of the woods, which isolates her from the world of the men. On top of living in a deep wood, fear also forms a “circle” around the Baba Yaga, as she kills anyone that comes near her house and people avoid it - sometimes the forest even has additional obstacles, such as a deep pit, or a mountain.

In “Ilia of Mourom and the dragon” (NRS 310), we actually do not have a forest, but a mountain, forming a vast plateau. The hero needs to climb a very tall and very steep mountain made of sand - in order to go to the palace of the tsar whose daughter is harassed by a dragon. At the top of said mountain, the hero encounters not one but two Baba Yagas, who tell them how to reach their elder sister, and then the “Nightingale Robber”, whose whistling is so deafening it kills who hears it. The rest of the story seems to happen on the same plateau, since the hero is never said to go back down. The demultiplication of the Baba Yaga, turned into a trio of sisters, each older and more powerful than the next, and the presence of the Nightingale-Robber, embodiment of absolute evil and enemy of the Russian land, expands the “frontier of the otherworld” into a true no man’s land.

A similar phenomenon of “expansion of the liminal area” can also be found in the second version of “The feather of Finist, the fair falcon” (NRS 235), where the heroine has to walk into a deep and dark forest until iron slippers and an iron bonet are “worn out” - only then does she found a “small house made of lead, constantly turning around on chicken legs”. Sometimes the house is said to be found “beyond the three times nine countries, in the three-times-tenth kingdom, on the other side of the fire river” (Maria Morevna, NRS 159). As in the previous tale, the river of fire plays the role of a “last limit” between the world of the humans and the other world - and when Ivan returns, as the Baba Yaga finds herself deprived of her magical scarf, she burns in the flames.

The isba of the Baba Yaga has so many different descriptions that Vladimir Propp used it as the perfect illustration for his “Transformations of the fairytale”. Only two elements stay the same: the house is located near a forest, and has chicken legs. And even then, sometimes the chicken legs are replaced by other animal parts, such as “goat horns” in “Ivan the small bull”. In the second version of “The feather of Finist, the fair falcon” (NRS 235), the heroine finds a “little house of lead, on chicken legs, that was constantly spinning”. Propp explained that actually, the descriptions of the house constantly spinning on itself are oral deformations of what the house could originally do - turn on itself whenever it was commanded to. From “turning back”, the house simply started “turning”, until came the image of a house constantly spinning. In one of the seven versions of “The sea-tsar and Vassilissa the very wise” (NRS 224), the house is not described (”a small lonely isba”) and only two elements allow to identify it as the house of the “Baba Yaga with the bone-leg”. One is the dark, empty forest surrounding the house, and the second is the fact that when Ivan-son-of-merchant tells it “Small house, small house, turn your back to the forest, and turn you door towards me!” the house obeys and moves. And inside waits the Baba Yaga, her body going from one corner of the house to another, and her chest sagging to yet another part of the house.There is one particular case, the one of the NRS 141-142, “The brave Bear, Mustache, Hill and Oak”, in which the Baba Yaga and her daughters live in an underground world, with no mention of the isba.

But what happens inside this house, with this house? Propp did wonder, upon looking at the fairytales - why does the house needs to turn around for one to enter? It is true that Ivan finds himself in front of a wall “without windows or doors”, but why doesn’t he just go around the house, instead of telling it to turn? It seems to be forbidden to go around the house... The house seems to be on a frontier that Ivan cannot cross - one has to go through the house to pass, as it is impossible to cross otherwise. The open side of the house is usually turned towards the “three-times-tenth kingdom” that Ivan must reach, while the closed side is turned towards the realms Ivan comes from - Propp linked this with the Scandinavian custom of never having a door facing the north, because the house of Hel, goddess of the afterlife (Nastrand, the “beach of corpses”), had its door located towards the north. With this element, Propp concludes that the house of the Baba Yaga is actually the limit of the world of the dead - and crossing the house allows to “select” who passes and who doesn’t pass into the afterlife. Thus the meeting of the Baba Yaga is a trial in itself.

Propp sees in the chicken legs a remnant of the pillars on which stood the initiation-cabin, which seems to feed into this idea of the Baba Yaga’s isba being a rite of passage towards death. In his book about ancient Slavic paganism, Boris Rybakov mentions a type of malevolent undeads called the nav’i (nav’ in singular), who are the dead without baptism and that we must appease through offerings. He says that they appear like enormous birds, or feartherless roosters the size of eagles - they leave the footprints of a chicken, and attack pregnant women and children to drink their blood. These elements clearly evoke the myth of the Baba Yaga: is she one of those “wrongly-dead”, turned hostile towards humanity?

If we read the dialogue between the Baba Yaga and the hero of the tale, we understand better the trial that the Yaga is. In the tale “Ivan Bykovic” (NRS 137), Ivan-small-bull enters the “chicken-legged, goat-horned house”, and sees the Baba Yaga with her bone leg, laying on her stove, stretching from one corner of the house to another, her nose reaching the ceiling. She exclaims that up to this day she never smelled or saw a Russian man, but today she has one “rolling on my spoon, rolling in my maw”. Ivan answers “Hey, old woman, don’t get angry, come down from your stove and sit on the bench. Ask us where we are going, and I’ll answer you kindly.” The Baba Yaga has a similar dialogue to the heroine of the second version of “The feather of Finist, fair falcon” (NRS 234-235), but there she is less aggressive, probably because the maiden calls her tenderly “babusja”, “small grandmother”, to which the Yaga answers with affection “maljutka”, “little one”. These examples prove us that the heroes and heroines have to find the rights word to either intimidate or appease the Baba Yaga, to make her an auxiliary. For a male hero, it is courage that is put to the test, when it a female hero, it is politeness that needs to be used. But always, it transforms the Baba Yaga, from a guardian and an adversary, to a guide and auxliary.

In some tales, the Baba Yaga is much less aggressive, and is immediately a guide to the hero, and even shows some tenderness - like in the first version of the tale “The sea-tsar and Vassilissa the very-wise” (NRS 219-226) where she tells everything the hero needs to know for his quest, and calls him “ditjatko”, “my child”. This role of auxliary and guide is especially present in the tales where the hag is depicted as the mistress of the animals, or of the winds. For example in “The enchanted princess” (NRS 271-272), the hero, a soldier, uses a flying carpet to find where his fiancée is located. He visits successively three Baba Yagas, all sisters. The last one lives “at the end of the world”, in a small house beyond which there is only pitch-black darkness. Beyond the end of the world, there is nothing, the void. This last Baba Yaga is the ruler of all winds, and helps the soldier by summoning them - the south wind ends up revealed to the hero where he will find his bride.

However these are the tales where the stay at the Yaga’s house is brief. Other times, the hero has to stay for a long time at the house, and then the nature of the trial changes: the hero has to fight to keep their life. In “Maria Morevna” (NRS 159), the hero goes to Baba Yaga to obtain a magical horse able to rival the one of Kochtcheï-the-Immortal. The Baba Yaga agrees, but only if he serves her for three days - if he succeeds, he’ll have the horse, if he fails, she will place his head at the top of a pole. The hero manages to overcome the various imposed chores thanks to the help of animals he spared previously in the tale.

Another very interesting example is in the very famous fairytale, Vassilissa-the-very-beautiful (NRS 104), which is also the one where the house of the Baba Yaga is described in the more details - including the spikes covered in human skulls that Ivan Bilibine famously illustrated. After letting purposefully the fire go out in her house, Vassilissa’s wicked stepmother sends her fetch some fire at Baba Yaga’s house. Instead of being devoured, the heroine returns safely, and on top of that, this travel to the otherworld acts as a “reparation” - since justice is re-established through the deserved punishment of the wicked stepmother. The fire Vassilissa brings back destroys the wicked woman, reducing her to ashes. We should also note that, unlike in other tales, there is no need to ask for the house to turn, Vassilissa simply waits for the return of the Baba Yaga by the entrace gate. And on top of overcoming her fear, the girl is faced with much more complex tasks. The first is to do the house chores, but which are impossible by their enormous scope - however Vassilissa manages thanks to a magical doll and her mother’s blessing (the first being the manifestation of the second). The second trial is when the Baba Yaga has a discussion with the girl: she encourages Vassilissa to ask question, while warning her not to ask too much, because “not all questions are good to ask”. This is because the implicit taboo is to not ask the old woman about what is going on INSIDE her house. Vassilissa is victorious, because she knows when she should just observe - she doesn’t ask about the mysterious disembodied pair of hands working inside the house, but about the horsemen riding around the house, in the woods, and the Baba Yaga is very glad she asked about “only what was in the courtyard” - but, as some commentators noted, this is also perhaps the last trial because it is the only one that Vassilissa manages to overcome without the help of her magical doll. Once she saw what she had to saw, and overcame her fear, Vassilisa was initiated to typically feminine tasks of the patriarchal society - cleaning the house, preparing the meal, weaving... But this serves to actually fulfll her destiny - as in the second part of the tale, she arrives at an old woman who creates shirts, and the shirts she makes for the old woman are so good the tsar itself will summon Vassilissa and marry her, thus fulfilling the prophecy of her name (Vassilissa coming from the Greek “basileus”, “king”). The hero becomes a hero because they manage to perform the imposed task - these are “elective trials”.

Russian fairytales contain numerous other characters merely called “old women”, “hags” or “crones”, but that some elements associate with the Baba Yaga and the role of the “initiation-master”. Their old age, the fact they live in a house near the woods, and especially their way of speaking to the hero. We even meet a genderbent Baba Yaga in “ivan-of-the-bitch and the White Faun/Sylvan” (NRS 139) - an old man in a mortar, who pushed himself around with a pestle. Though this character’s behavior does not evoke the Baba Yaga at all.

With all of that being said, again the Baba Yaga is provent to be a deeply ambivalent character. Many different searchers provided many different explanations, but always ended up confronted by the contradictions that made her. According to the author of the article, the most pertinent theory would be the one of Anna-Natalya Malakhovskaya, who sees in Baba Yaga not just “an archaic mother-goddess in a world of good and evil dichotomy”, but rather a “goddess whose many roles fulfill the three functions of Dumezl”. That is to say, 1) wisdom and the link to the sacred, the magical divinities 2) the warrior function and 3) the fertility/fecundity function that is interwoven with death.

So... What sense should one give to these tales about a travel to the other world, to the afterlife, to the world of the dead? Beyond the entertaining nature of fairytales, is there an initiation in these tales? We can remember that Vassilissa the very beautiful, in her tale (NRS 104) is banished by Baba Yaga once she reveals to her the nature of her magical helper - when she speaks of the blessing of her mother, Baba Yaga tells her to leave the house, since she doesn’t want anyone blessed in her house. There seems to be something dadactic at work here - especially when we consider the virtues embodied by Vassilissa: piety (in the traditional sense, religious piety) and filial piety (as she stays faithful to the words of her mother), as well as docility, serviability, and bravery or rather trust. Trust in her mother’s blessing that even the all-powerful Baba Yaga cannot contradict. This last motif, of which the Vassilissa tale is the most emblematic example, highlights how the Baba Yaga is tied to archaid, pre-Christian concepts. We see here the tie to the protecting ancestor-spirits, through the mean of the mother’s blessing, which saves the heroine. This tale maybe illustrates the “double faith” so typical of the folk-Christianity of Russia.

Now, if we return to the tales evoked briefly at the top of the article - the ones where the hero doesn’t visit Baba Yaga’s home, but rather those where Baba Yaga invades our world to kidnap a child. How to explain the appearance of the witch in the world of the humans, either directly, or through intermediaries (the wild geese). If we look at “The wild geese” (NRS 113), we notice that the little brother is actually quite safe in the Baba Yaga’s house - he plays there with golden apples. What causes fear and trouble is the fact that he was kidnapped, more than where he stays. The disturbance in the order comes from the ravishing - and the girl is worried that she will be punished for to not having watched over her brother well enough. It seems here that the appearance of the sinster Baba Yaga, or of her winged servants the wild geese, is here bringing an answer to the phenomenon that reason refused to explain - in this case infant mortality. These “wild geese” that “ravish little childrens” might be agents of death.

In conclusion, the Baba Yaga is at the same time the guardian of the frontier to the other world, but also the ferryman (or ferrywoman) leading to it, the guide to this other place - for she is a liminal being between the world, half-living, half-dead, half-animal, half-human. It seems that layers and layers of cultural meanings, symbolism and interpretations have accumulated themselves onto the Baba Yaga more than on any fairytale character, resulting in a complex and tangled knot creating a divinity as spiritual as chtonic, ruling over the fate of mortals.

As for the geography of the fairytales, we can clearly have a three-part map with the Baba Yaga tales: our world, the other world, and the in-between-world. In the in-between world, passage can go either way. Under the aspect of simple, entertaining stories, these tales are initiation rites, describing through images and pictures the changes happening when one “passes” into the adult age, as much on an individual level as on a social one.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Image ID: A tall metal construct like a teapot with two gangly legs is striding across a craggy landscape, beneath a cloudy sunset sky. Warm light shines out through porthole windows, and steam emerges from the spout. End ID.

This could be the home of Baba Yaga's cousin! The bony leg joints are certainly a bit spooky, and despite the steam I think magic has to be involved in the operation... Idea: the mechanical tea shop of Baba Meiga clicks and clanks through the hinterlands of a half dozen worlds, seeking out solitude and melancholy scenery. This witch does have a sense of hospitality, though, and sells her unique tea blends to all kinds of visitors. There's a tea that cures forgetfulness, a tea that creates overconfidence, a tea that makes the drinker incredibly fast, and countless others. Baba Meiga chooses one with a flavor profile and magic effect suited to each patron. She also has a jar on the top shelf for rude customers, and tea blends with this mixture turn the drinker into a bird.

Your party might encounter the Wandering Teapot just when they need a place to rest in the wilderness, or just when they have a lot of money to spend after looting a dungeon. Baba Meiga charges a lot for her brews, but it would be rude to complain about the price...

A Never Ending Walk by by Waltjan Prints available here : Waltjan

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

A lively story that successfully combines two well-loved characters from Russian folklore--the firebird and Baba Yaga--into the story of a tzar overcoming his fear of the unknown. Upon his coronation, Prince Yaroslav gives a magnificent banquet, but fails to invite the bony-legged witch, Baba Yaga. She crashes the gathering and presents Yaroslav with her gift, a magnificent firebird, warning that if any harm comes to it, he will be banished to the Outermost Edge of the World. Although he fears punishment, Yaroslav grows careless and the firebird droops. True to her word, Baba Yaga banishes Yaroslav; spurred by his deep fear of that dreadful place, he completes a perilous journey to reclaim the firebird, only to realize that he no longer needs it.

#givebooks#vintage#bookswelove#aycarambabooks#shopsmall#finegifts#rare books#picture books#Ann Tompert#fear

1 note

·

View note

Text

RED MOON

She looked at each of them, watching those pleading eyes. The man, as if he knew what she knew, knelt before her in search of her motherly mantle; the woman on the other hand remained static, not knowing exactly what to do. Ah, two lovers, escaping the death clutches of the tyrant husband who sought revenge with his lackeys. The crimson rays of the moon were perfect, staining the half-naked bodies a passionate red. Her silver teeth gnashed in annoyance as her blue nose sniffed the atmosphere, filling with satisfaction as she smelled the fear emanating from the lovers. The skulls were beginning to tremble in an attempt to alert.

"Baba Yaga, please. We'll do anything, we just want to be happy." The man held his position, not looking directly into her eyes. The atmosphere felt too heavy, breathing was getting harder and harder as those bony fingers of the old woman touched the locks of his hair." We begged."

Oh, young souls begging for salvation, what blessing had she received to have great entertainment? She circled the couple, her white hair hanging down her shoulders as an idea crossed her mind, drawing from her robes a small dagger sharp enough to cut the flesh of those who looked appetizing. The Lovers looked at each other in confusion, the metal gleaming furiously in that dim light as the woman's trembling hands held it. Baba Yaga stepped back, pulling out a pair of grapes.

"Their bodies must be consumed in the heat of passion, once they are at the climax they must open a wound and join their bloods together." She recited an old chant, declaring since then that whoever did as she indicated from now on would get the same wishes. Her smile is hidden by her hair, watching as the lovers fell to life's oldest lesson: Don't trust strangers." They will eat the grapes and drink of the wine at the same time."

That metallic smell was delicious, making his mouth fill with saliva as the bones in his leg quivered with anticipation. Wasn't it fun to play with innocent minds? As soon as the lovers placed their order she could feel the change, watching mischievously as the tyrant's lackeys arrived just in time, just as she had anticipated. Souls had changed.

To her amusement the two lovers were punished in the opposite body, she suffered his punishment and vice versa, watching as her body was bruised by the lackeys and the tyrant but instead of it being her suffering those pains it was him. Some things came with a price, salvation in them could never be completed. She handed them the opportunity to see how they could have died and that was enough.

"Both hearts cannot be separated, cannot be hurt or denied until they reach the end that the universe arranges to return to the original bodies." She murmured, sealing the pact as she was ignored by the men. Her silver smile being the last thing to be seen as she hid in the darkness of the forest.

A little sketch of what will be my new fic Red Moon XD I hope you like it, I've been thinking about it a lot.

#ao3 fanfic#putvedev#ruspol#vladimir putin#dmitry medvedev#body changes#sketch#idk what im doing#idk what else to put in the tags

0 notes

Text

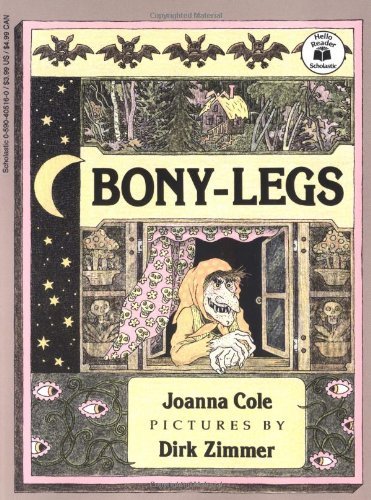

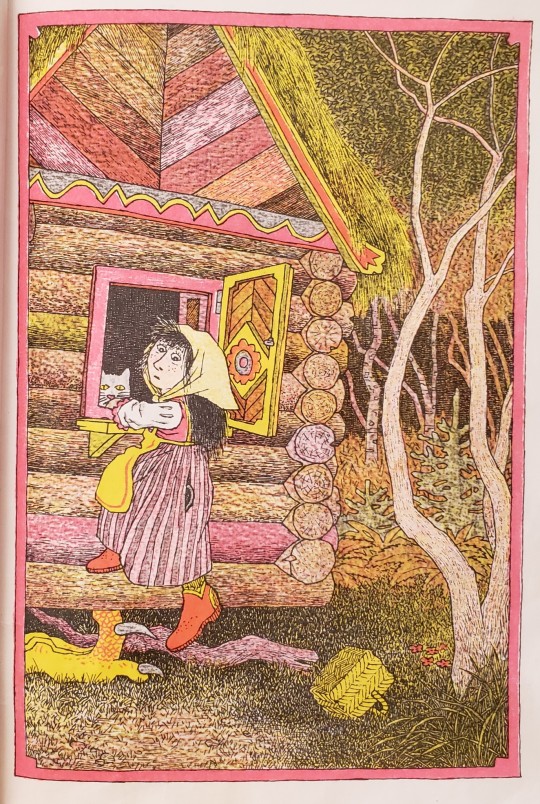

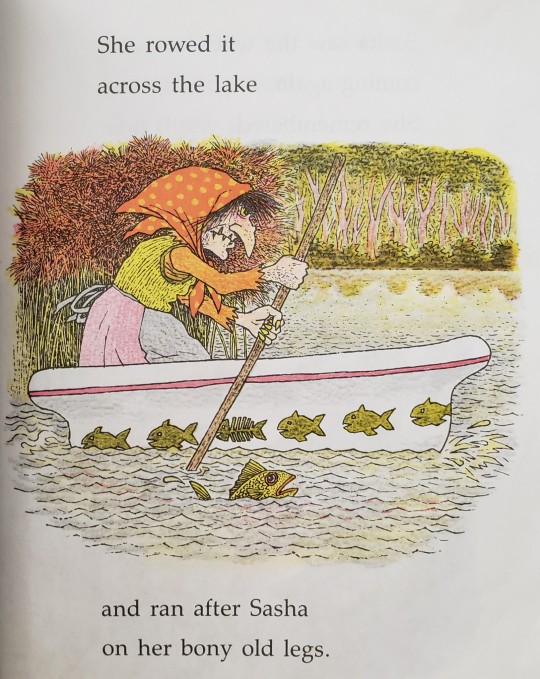

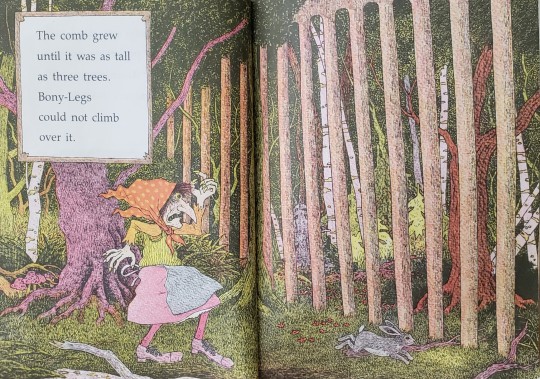

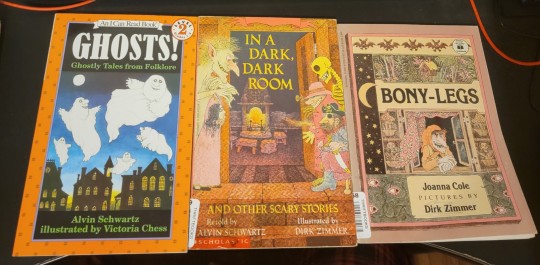

Bony-Legs (1983)

Story: Joanna Cole -- Art: Dirk Zimmer

#bony-legs#bony legs#baba yaga#witches#dirk zimmer#in a dark dark room#joanna cole#picture books#kid books#kidlit#children's books#children's literature#chicken leg hut#fairytales

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

bony legs, like baba yaga’s house!

33. the last adventure you’ve been on?

i bought a baby chicken from an old lady on saturday and clipped her wings before trying to introduce her to our other chicken :)

25 notes

·

View notes

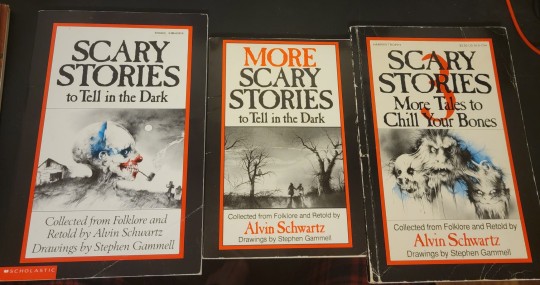

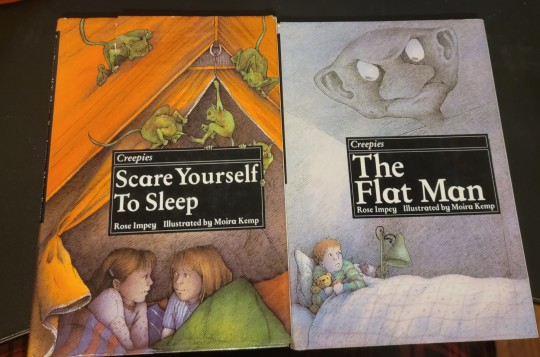

Text

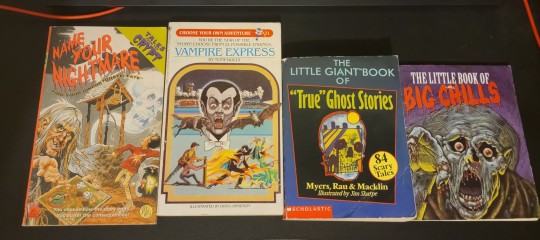

Got some old scary story books from my childhood. Bony Legs was the first time I'd see Baba Yaga even if they didn't use that name. Dark Room has the infamous green ribbon story, and of course Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark. These and others were a good part of introducing me to horror as a kid.

#bony legs#scare yourself to sleep#scary stories to tell in the dark#the flatman#dirk zimmer#moira kemp#alvin schwartz#baba yaga#horror#Halloween

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This book terrified me as a kid.

0 notes

Text

Magical summer: Baba-Yaga

BABA-YAGA

Category: Slavic folklore / Russian fairytales

Western fairytales (French or German) have recurring archetypes: there’s always a dumb hero, a princess in need of rescuing, a witch, a hungry beast… In Russian fairytales, it is much simpler, they have recurring characters that fill these archetypes. For example Vassilissa, who is all the pretty young girls faced with dangerous threats ; or Ivan Son of the Tsar, who is all the brave young princes setting on a quest… And whenever there is a need for a witch in the woods or an ogre in a fairytale, it is always the job of one character: Baba-Yaga, a fascinating and important figure of Slavic folklore and Eastern European legends.

Baba-Yaga is, as I said, a cross between a witch and an ogre – she might seem a bit human at first, but she is not. Baba-Yaga looks like an old woman, but a repulsive, deformed, ferocious one. In fact her very name indicates that she is an old hag or an ancient crone: “baba” can be understood in many ways, either as a diminutive of “babouchka” (grandmother), either as an impolite way to designate a “common woman/vulgar woman”, but mostly it is understood as a designation for any kind of older woman in general. As for Yaga it is a proper name (so you could call Baba-Yaga, “Old Yaga”, “Mother Yaga”, “Granny Yaga”, etc…) – though its origins are uncertain, and it could be for example of the same root as “hag” (meaning Baba-Yaga name could literally mean “Old Hag” or “Granny Hag”). Sometimes she is said to have a nose so long it touches the ceiling ; sometimes she is said to have breasts so long and flat she can wrap them around her stove ; and very often she is said to be “bony-legged” (as in, one of her leg being just bones), or to be “one-legged”.

You can recognize Baba-Yaga through a series of iconic traits. For example her house: she lives in a wooden hut deep in the woods, and the particularly of this house is that… it stands on chicken legs. This allows Baba Yaga to move her house whenever she wants, in order to travel through the woods. (One unique variation depicts her as not living in her isba, but right under it, in tunnels underground – and whenever someone stays or enters in the empty isba, thinking they can spend the night there, she comes out of the ground and kill or torture them). Like all witches she also flies into the sky, but not with a broom: rather she uses a giant mortar and a giant pestle. She hops in and flies into the sky! Sometimes she is also depicted holding a broom while travelling with her mortar/pestle, using it to better “direct” the flying objects – it is actually a leftover of the original way of travelling of Baba-Yaga : in the original tales and legends, it was said her giant mortar actually walked, moving like a horse – she used the pestle like one would use a whip on a horse, and she used the broom to erase her tracks behind her so that no one could find her back. But as time went by, people understood that the mortar was actually flying, and it is what stuck into popular culture.

Baba-Yaga is a mostly feared and dreaded figure in Russian fairytales, due to her playing most of the time an antagonistic role. You see, she is well-known as a child-eater and child-killer (that’s her “ogre” role) : as a result sometimes a child lost in the wood will end up by mistake in her house and have to escape before being cooked ; other times nasty people will send the innocent protagonist to Baba-Yaga’s house without the latter knowing ; and yet other times Baba-Yaga actively hunts down children that she kidnaps to devour. Another ogre element of her character is how, like a regular ogre or a fairytale giant, she can sniff out the smell of human children, or of “Russian flesh”. Her devouring actions are made even more fearsome when you take into account several stories says that she has sharp teeth made of IRON. And even when she doesn’t actively try to eat and devour people, she is often depicted as a very hostile and aggressive creature that tries to kill anyone who happens to meet her or stumble upon her house. However, the hero always ends up defeating her, escaping her or tricking her (as typical heroes do to witches and ogres).

Despite being generally an antagonist, Baba-Yaga is actually a bit more ambiguous as she can fill the role of a “helper”. Many fairytales depict her as someone that the protagonist actively seeks, or from who the hero gets big advantages. In these versions, Baba Yaga is depicted as a knowledgeable woman keeper of many important secrets, as a keeper and giver of numerous useful magical items, as a powerful magical force of the woods that can be helpful… but she is not a kind figure. To get her help, already one has to find her house (usually well hidden) and find a way to enter (sometimes the house has no doors, other times it spins endlessly on the chicken legs and you have to find a way to stop the spinning). Inside, the hero usually has to find ways to avoid being eaten by Baba-Yaga, and/or has to answer a given set of precise questions that, if answered wrong, will lead to the hero’s death. One sure way to be safe from Baba-Yaga is to point out that, after entering the house, she hasn’t offered you food or drinks – it invokes the ancient law of hospitality, and Baba Yaga is forced to treat you as a guest (aka not eat you). Other times Baba-Yaga can put the hero through trials and tasks in exchange for her help (for example she can ask the hero to wash her “children”, who turn out to be a bunch of venomous snakes, poisonous toads and ugly worms).

Overall, Baba-Yaga is a very ambiguous and symbolic figure… On one side the fairytales clearly depict as a “mistress of the woods” and a “spirit of nature” : she is a fantastical witch that lives deep in the woods, to escape her the hero usually has to get out of the woods, and often she is depicted as being able to command all the wild animals (or she is seen having in/around her house a whole lot of wild familiars and beast-servants that the hero has to appease). On the other side, it is also pretty obvious that Baba-Yaga is actually a force of death and a symbol for the afterlife: her house is often surrounded or decorated with human bones, sometimes the isba is described as without windows and doors and small enough for just one person to fit (making it look like a coffin), and other times her house is said to be at the edge of a “thick darkness with nothing in it” or another sort of dark, empty landscape – making it seem like she is the guardian of the afterlife.

Another important thing to note is that, while half of the fairytales depict Baba-Yaga as living all alone, isolated in the woods, without any kind of family or friends, the other half of the Baba-Yaga stories always depict her surrounded with other entities: sometimes her house is filled with servant beasts, other time she has one or several daughters (that will either assist her mother, only to end up being killed by the hero through a trick ; either will help the hero and oppose their mother), and that’s without mentioning the times where Baba-Yaga is depicted with supernatural servants (or even leading an entire army!). One very famous tale, “Vassilissa-the-Beautiful”, notably shows her having three servants taking the form of horsemen: the first rider is white, and is the embodiment of the day ; the second horseman is red, and the embodiment of the sun, and her third servant is black, and the embodiment of the night. This great mastery of natural elements tends to show up in other tales, where she is depicted going to war using a “shield of fire” and throwing/spitting fire all around her. Other times she is said to have as servants disembodied hands, or living shadows.

- - -

Baba-Yaga is such a multi-faceted being that many theorized she actually is the result of a fusion of various witch figures from Russian and Slavic legends - which would explain why she appears as both a villainous ogress and a helpful magical being. Due to the traces of Baba-Yaga in very old tales and legends across various Slavic cultures and literatures, many people believe and have theorized that she actually started as a Slavic goddess, or as a powerful spirit of old mythology, before devolving into a fairytale witch and legendary sorceress. Some tales actually seek to explain the duality of the character. For example one tale claims that she only eats those that are too curious - and leaves the others alone (another tale backs this up by claiming that Baba-Yaga does not naturally age, but ages of one year every time someone asks her a question). A second version rather claims that she can only eat and kill naughty children, and that she can't harm good children - as a result she is often depicted enslaving good children, and giving them all sorts of hard and difficult tasks (so that if they fail to obey her, she can consider them "naughty" children and eat them). But on the flipside, if a hero performs all the tasks and passes all the trials she puts them through, she is forced to let them go unharmed. Ultimately, many legends decided to solve the multiplicity of behaviors of Baba-Yaga by actually claiming that there isn't just ONE Baba-Yaga but many. One famous tale depicts the Baba-Yaga as three identical sisters, living in three identical houses at three different corners of the wood - but while the first one is very helpful, and the second a bit less so, the third is the very aggressive, hostile, man-eating Baba-Yaga everybody knows. Other tales keep saying that a hero goes or meet "a Baba-Yaga", one even saying that there is an entire species or race of baba-yagas out there.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Then she came to the hut of Baba Yaga, the bony-legged, the witch. There was a high fence made of human bones, and just beyond was the house, standing on hen's legs and walking about the yard.“

#art journal#mixed media journal#grimoire#magic book#spell book#art magick#art magic#illustrator#folklore#folk witchcraft#folk magic#baba yaga#illustration#whatpennymade#artwitch

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Baba Yaga

He journeyed onwards, straight ahead .. and finally came to a little hut; it stood in the open field, turning on chicken legs. He entered and found Baba Yaga the Bony-legged. "Fie, fie," she said, "the Russian smell was never heard of nor caught sight of here, but it has come by itself. Are you here of your own free will or by compulsion, my good youth?"

#baba yaga#russian#russia#russian folklore#folklore#russian fairy tales#fairy tales#fairytaleedit#folkloreedit#mythedit#q

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mythological figures in Slavic folklore

Here is a very short list with brief descriptions of the main figures found in Slavic mythology (in particular, the early Rus’ people and later Russian folklore). Art not mine🌲

Zmei (Змей)

Zmei is a three-headed fire-breathing dragon with claws made of iron. If the hero chops off one of his heads, two more (in some stories, three more) will grow back in its place. Zmei is often seen around remote locations such as mountains and forests, but has also been known to terrorise villages and kingdoms.

Domovoi (Домовой)

Domovoi (meaning ‘man of the house’) is a house spirit in the form of an old man, around the same size as a gnome (~2-4 feet tall). Domovoi keeps the home organised, sweeps the floors, and helps in the kitchen. Some can be grumpy, but become friendly once you offer them food or clothes. In return, they will protect the house, take care of the animals, and ensure abundance within the house. To attract Domovoi into the home, Slavic witches used to leave a boiled egg on their doorstep as an offering.

Koschei the Deathless (Кощей Бессмертный)

The name ‘Koschei’ comes from a combination of the words ‘кость’ (meaning ‘bone’) and ‘тощий’ (meaning ‘thin’ or ‘skeletal’). Koschei is a thin, bony figure, a grumpy and sometimes cruel old man, the King of Death; he rides a horse who can run faster than the wind, and in some stories he is described as having a throne made of human bones. Koschei generally has a friendly relationship with Baba Yaga, although in some stories Baba Yaga gives the hero advice on how to kill him. Koschei is not truly deathless; in fact, his entire life force is contained within a golden needle, which is hidden inside an egg, the egg is inside a duck, the duck is inside a rabbit, and the rabbit is in a chest bound with chains, which hangs on the branches of an ancient tree by the sea. The only way to defeat Koschei is to snap this needle in half.

Baba Yaga (Баба Яга)

Baba Yaga is an old and wise witch, taking the form of the hag, with a hooked nose and white hair. She is the mistress of the forest, the animals, and of darkness; she is a true hedge witch of wisdom, walking the fine line between physical and magickal reality. She often has a familiar such as a cat, a raven, or a frog. She travels in a flying mortar, using her broomstick to sweep herself along in the air. Her house is a hut that has chicken legs which can move and walk around on their own, and bury themselves in the ground to hide the true form of the hut from mortals. The house is also surrounded by a fence made of human bones and skulls. If a mortal hero visits Baba Yaga’s hut, she can offer to give them advice to help with the journey ahead. If you are disrespectful to Baba Yaga when visiting her, however, she will eat you and use your bones as decoration for her home.

Leshy (Леший)

Leshy is a forest spirit who can come in different forms; sometimes in the form of an old man who has grown out of a tree, and sometimes in the form of a small elf. Leshy is the keeper of the woods and the woodland creatures; he is respectful of Baba Yaga and they are mostly on civil terms with one another. While Baba Yaga is in charge of creating potions and teaching humans the art of magick, Leshy is the protector of the forest and is often surrounded by creatures of the woods. Amongst mortals, Leshy disguises himself as a tree or as another part of the forest scenery to avoid being seen.

Vodyanoi/The Water Spirit (Водяной)

The word ‘водяной’ literally means ‘man of the water’. He is often portrayed as a merman with facial hair made of moss or kelp. He dwells in bodies of fresh water such as rivers, lakes, and swamps, and he is the protector of all aquatic creatures, including rusalki (mermaids). Vodyanoi has been known to give advice to mortals passing by.

#witchcraft#magick#spirituality#slavic witchcraft#slavic witch#mythology#slavic shamanism#slavic mythology#russian folklore#slavic folklore#culture#mythical creatures#magic#stories

721 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russian Fairy Tales Test Prep: Baba Yaga

Baba Yaga likes to travel in a mortar and pestle, with a broom to sweep away her tracks.

Baba Yaga has a habit of breaking & entering in order to count a household’s spoons. The correct ratio is 1 spoon per person. If you have more or less, or if you interrupt her count, you’re in trouble.

Baba Yaga’s hut. It can travel, but it mostly just rotates to grant/deny visitors access.

There is also a fence of glowing skulls around her property. She lives in the heart of the woods, and many stories start with being *sent* to her hut.

Baba Yaga, as depicted by Ivan Bilibin (1900)

The heroine Vasilisa outside Baba Yaga’s hut, as depicted by Ivan Bilibin (1899)

Baba Yaga, as depicted by Viktor Vasnetsov (1917)

Hut on Chicken Legs, built by Viktor Vasnetsov (1883)

Baba Yaga in Dubai, as sculpted by Irina Lagoshina (2018)

Miyazaki’s take on Baba Yaga in Mr. Dough & the Egg Princess (2010)

Mike Mignola’s Baba Yaga in Hellboy (1996-)

Baba Yaga in Neil Marshall’s Hellboy (2019)

Baba Yaga is very old, unnaturally so, and frail in appearance (she is sometimes described as “bony-legged”) but she is STRONG. She can smell Russians, and she will eat them.

Her powers derive from nature; she is said to have animal familiars and an ill wind portends her arrival. She is associated with both poison and medicine.

Her gender presentation is somewhat ambiguous; she has a number of stereotypically masculine traits, as well as a number of stereotypically feminine traits. Her numbers are also ambiguous; she is sometimes called THE Baba Yaga, sometimes a Baba Yaga. There are tales where she has sisters and/or daughters.

Baba Yaga works in mysterious ways. Sometimes she’s the villain of the story, often in an “evil stepmother” role. Other times, she’s more of a “fairy godmother.”

Baba = “grandmother” - in Polish, it means “woman” (pejorative) - in Russian, it means “timid/unmanly man” (pejorative) - in Ukrainian, it is the plural form of a word referring to an autumnal funeral feast.

Yaga = “witch” - in other Slavic languages... - “horror/shudder/chill” - “evil woman” - “fury” - “disease/illness” - to abuse, belittle, or exploit

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'll bite:

Tell me about your RWBY OCs especially Dove

Yeah!

So Dove Pepper is the first RWBY character I created. She's the leader of Team DRRK, which was once Team DARC, but I changed it. She's based off of Snow-Daughter, from Snow-Daughter and Fire-Son, which prompted me to change her cloak and her Semblance ever so slightly.

She's a deer Faunus, with little deer ears, and her weapon is a large battle axe, which is also a shield and a sniper rifle. She also has a dagger, which is also a pistol, just in case. They are called Homage and Pity. Her Semblance is that she is able to summon a herd of icy deer, which do her bidding. A downside to her Semblance is that she is always radiating cold air (but doesn't notice).

I'm still working on the rest of Team DRRK, but they aren't as important to the story I'm working om because after graduation they all disagree on how to do their job, and split up, but it consists of, Reice Norma (formerly Amber), Rebecca "Ray" Rain, and Kameron Moone.

Next up is Jay McIntyre, a cat Faunus with a fluffy white tail, based on the Step Daughter from Baba Yaga the Bony-Legged Witch. Her team was Team JADE, which she lead rather poorly because of her tendency to get distracted and run off to do other things and pick random stuff up. Her Semblance is that she is able to make a copy of any inanimate item she has touched, skin to item. For instance if she grabbed Homage in axe form, she can make a copy, but the copy would not be able to turn into shield or sniper form. Her weapon is a double headed bullhook, which is also a pair of shotguns, called Demon's Veil, which she can separate into two.

Monochrome Watcher is up next! He is also a cat Faunus, but with ears, and was a part of Team MMPL. He is based off of Puss from Puss in Boots. His weapon is called Euthanasia, and is a scythe, ray gun, and shotgun (although he calls it a shot booster because he only uses it to propel himself). I've not settled on his Semblance, although I'm thinking maybe he can hear the thoughts of those around him.

Finally from this story is Fallow Heath, who is based off of the Soldier from the Magic Tinder Box. She is a dog Faunus, with a tail. Her main weapon is a gattling gun, flamethrower, cleaver sword, called Betrayal, and she has secondary pistol daggers called Traitor and Revenge. Her Semblance allows her to summon up to three dogs from any source of fire, which do her bidding.

Notice how all the main characters from this are Faunuses? I wanted this story to tackle the prejudice against Faunuses, so by having all the main characters, one from each kingdom (Dove from Vale, Jay from Mystral, Monochrome from Vacuo, and Fallow from Atlas), be Faunus, it makes it more clear.

I do have another story, with different characters, but I wanted to talk about this one specifically, because I love my girl Dove.

#demon whispers about nonsense#rwby#Dove Pepper#Jay McIntyre#Monochrome Watch#Fallow Heath#my characters#fun fact Jay was originally Dove's daughter#years ago I mean#jesus christ I was cringy#i mean Dove could turn into a dove and Jay was experimented on#so I guess I was also edgy#and Fallow and Monochrome are honestly knew versions of old characters#like how Reice was once called Amber and was a typical straight white girl human on a team of Faunuses#although I'm still very fond of Ray

2 notes

·

View notes