#avant-garde classics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

DJ Wet CupCake: The Beat-Master Narrating Azeroth’s Chaotic Trade Chat Live on KAKE 420 AM

KAKE 420 AM In an era where social media giants dominate the landscape, one voice rises from the cosmic wilderness of Azeroth’s Moon Guard to remind us of a time when Trade Chat was the most raw and authentic social platform on the internet. Enter DJ Wet CupCake, the emcee whose live shows on KAKE 420 AM blend avant-garde beats, quirky commentary, and the unfiltered madness of Moon Guard…

#abstract commentary#alternative radio#avant-garde classics#avant-garde music#Azeroth Trade Chat#cosmic beats#digital beats#Digital Cowgirl#Digital Rebellion#DJ livestream#DJ Wet CupCake#Eat My Cake Records#eGirl4Rent#electronic rave#Empowerment Through Music#fantasy immersion#femcel rizz#gaming culture#high fantasy vibes#immersive experience#immersive role play#Jade Ann Byrne#JadeAnnByrne#KAKE 420 AM#LA DJ#live talk radio#Los Angeles DJ#Moon Guard Alliance#Moon Guard RP#Moon Guard server

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Le Voyage dans la Lune” (A Trip to the Moon), written, directed, and produced by Georges Méliès (1902)

#dark academia#ethereal#vintage#ethereal goth#coquette#silent film#classic cinema#cinema#moon#dark asthetic#dark femme#gothic#fantasy aesthetic#1920s#whimsigoth#whimsicore#witch community#witchcraft#witchblr#witches#dark aesthetic#moon aesthetic#full moon#avant garde#science fiction

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

River Phoenix & Keanu Reeves, 1991.

#river phoenix#keanu reeves#my own private idaho#gus van sant#gay interest#classic movies#avant garde#poetic#beautiful

413 notes

·

View notes

Text

#coquette dollete#girlblogger#makeup#artwork#decor#poetry#coquette#lana del rey#lana del ray aesthetic#cocteau twins#im just a girl#manic pixie dream girl#avant garde#lolita fashion#fashion#y2k aesthetic#y2k#fairy aesthetic#goth aesthetic#aesthetic#music#new music#this is what makes us girls#sweet lolita#gothic lolita#classic lolita#2000s#2010s#2014 tumblr#2015 tumblr

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meshes of the Afternoon

Maya Deren, 1943

#maya deren#short film#old hollywood#black and white#surreal#dream world#avant garde#cinema#surrealism#contemporary art#women filmmakers#eldrich horror#eerie#strange#dreamlike#meshes of the afternoon#classic film

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sun Ra and John Cage

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

At Land (1944)

[letterboxd | imdb | kanopy]

Director: Maya Deren

Cinematographers: Alexander Hammid, Hella Heyman

“In my case I have found it necessary, each time, to ignore any of my previous statements. After the first film was completed, when someone asked me to define the principle which it embodied, I answered that the function of film, like that of other art forms, was to create experience—in this case a semi-psychological reality. But the actual creation of the second film caused me to subsequently answer a similar question with an entirely different emphasis. This time, that reality must exploit the capacity of film to manipulate Time and Space. By the end of the third film, I had again shifted the emphasis—insisting this time on a filmically visual integrity, which would create a dramatic necessity of itself, rather than be dependent upon or derive from an underlying dramatic development. Now, on the basis of the fourth, I feel that all the other elements must be retained, but that special attention must be given to the creative possibilities of Time, and that the form as a whole should be ritualistic…”

— An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film by Maya Deren, The Alicat Book Shop Press, chapbook, 1946

#1940s#1944#Maya Deren#Alexander Hammid#experimental film#avant-garde film#cinema#cinematography#american film#film#my gifs#short film#independent film#women directors#female filmmakers#cinemaspam#filmblr#classic film#classic cinema#classic movies#silent film#silent movies

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maison Martin Margiela line 11 plastic grocery bag with metal handle

A/W 2012

#maison martin margiela#martin margiela#style#archives#art#classic#avant garde#accessories#shopping bag#gross#genius

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tracklist:

Tout petit moineau • Damaged Wig • Absolute Psalm • Cicadidae • Vegetable Soup • Lullaby for a Fat Jellyfish • Grosse Barbe • Corpus Tristis • Scarlatti 2.0 • Toothpaste • Infinite Loop

Spotify ♪ Bandcamp ♪ YouTube

#hyltta-polls#polls#artist: igorrr#language: french#decade: 2010s#Breakcore#Avant-Garde Metal#Western Classical Music#Cybergrind#Opera#Drill and Bass#Black Metal#Glitch

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

🕸✨🦇🔮🪄

#women#music#underground#alternative#goth#classic#gothic#elegant#aesthetic#stage#performance#avant-garde#patricia morrison#intimate

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Post-Minimalism#Experimental#Film Score#Avant-Garde Jazz#Dark Ambient#Modern Classical#2010s#2020s#USA#Canada#poll

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay so yesterday i arrived to wroclaw

and today i randomly entered a book cafe cuz it was the closest nearby when i needed to wait somewhere

and upon entering i see giant rows of bookshelves with every single book IN UKRAINIAN

I'M GOING FERAL

i never want to leave this place

#personal#books and reading#ukrainian literature#i haven't been around so many ukrainian books in years it's a blessing upon my soul it's heaven on earth#they have справа Василя Стуса and за перекопом є земля and Дзвінка (which i just bought)#and poetry so much poetry#classical poetry of 19-20 centuries and modern poetry like zhadan and sooo much more#i'm so going broke in here#books on early 20 century avant-garde ukrainian artists#and traditional embroidery manuals

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

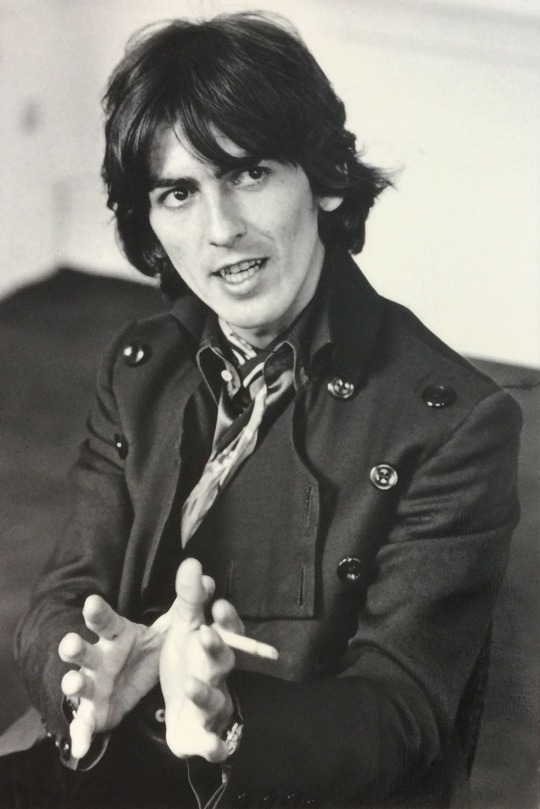

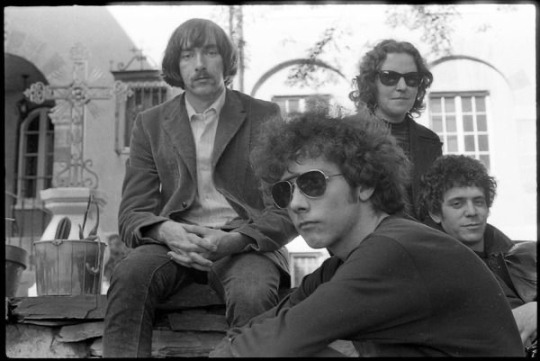

and happy OTHER late birthdays to both george and doug <33

#AGAIN im a lazy ass mf#george harrison#the beatles#john lennon#paul mccartney#ringo starr#doug yule#the velvet underground#loud reed#sterling morrison#moe tucker#60s classic rock#psychedelic rock#british invasion#avant garde#alt rock#60s music#60s

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Billy James: Necessity Is ... The Early Years of Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention (2001)

There have been countless books written about musical iconoclast Frank Zappa and I've read (almost too) many of them, but Billy James' Necessity Is … is the only one focused specifically on his original group, The Mothers of Invention.

Thus named because The Motherf***kers wasn't passing muster with record label A&R reps (and, as we know "necessity is the mother of invention"), the ever-expanding freaks who backed Zappa between 1964 and 1970 were, unlike most of his future groups, a lot more than sidekicks.

Rather, they were true Freak accomplices, who quickly evolved from basic rock and R&B combo to a free-form proposition able to play and improvise jazz, soul, doo wop, psychedelia, classical, and avant-garde music at their taskmaster conductor's beck and call.

At the same time, the band's irreverent approach to it all and Frank’s brutally cynical intellect were so innovative and unprecedented that their musical and personal antics influenced countless future bands and contemporaries -- even The Beatles, whose Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band The Mothers parodied, in turn, with We're Only in it for the Money, pictured above.

So, if names like Ray Collins, Roy Estrada, Jimmy Carl Black, Don Preston, Bunk and Buzz Gardner, Billy Mundi, Art Tripp, Euclid James 'Motorhead' (no umlauts) Sherwood, Ian and Ruth Underwood, Flo and Eddie, elicit your fond affection, this book is for you.

James interviews many of them, finally giving them a chance to tell their stories, their perspectives, and to reminisce about each album, each wild adventure, each other, and, of course, their brilliant and (now and then) beneficent dictator, Frank Zappa.

Featured Record:

The Mothers of Invention: We’re Only in it for the Money (1968)

Buy from: Amazon

#frank zappa#mothers of invention#classic rock#jazz#avant garde#doo wop#r&b#captain beefheart#roy estrada#ray collins#jimmy carl black#buzz gardner#billy mundi#ruth underwood#ian underwood#captain beefhearr#motorhead sherwood#art tripp#bunk gardner#little feat

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

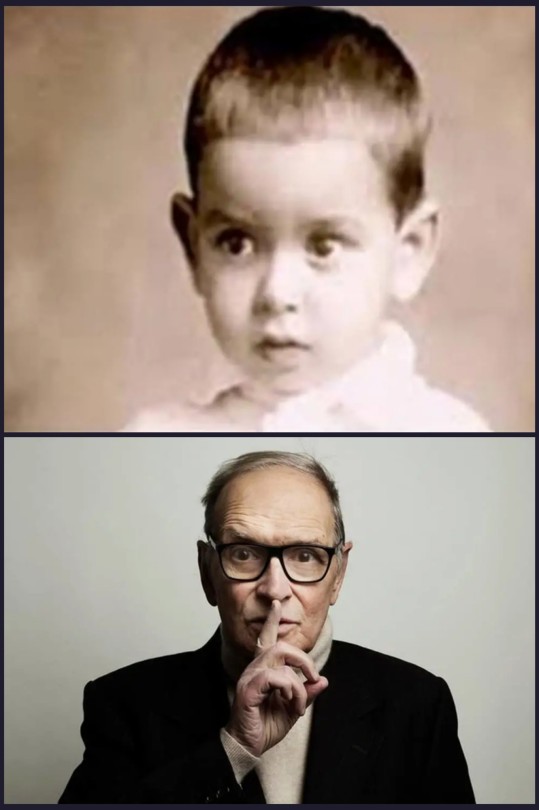

#On this day

#happy birthday

On November 10, 1928, Ennio Morricone was born, an Italian composer, arranger and conductor. Grand Officer of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic. Winner of two Academy Awards: for outstanding achievements in cinematography (2007) and for best music — for the "Disgusting Eight" (2016), 9-time winner of the Italian National Film Award "David di Donatello" for best film music, three-time winner of the Golden Globe Award, 6-time winner of the award BAFTA and many others.

Ennio Morricone was born in Rome, the son of professional jazz trumpeter Mario Morricone and housewife Libera Ridolfi. Ennio was the eldest of five children. When he was 12 years old, he entered the Conservatory of St. Cecilia in Rome, where Goffredo Petrassi became his teacher. At the Conservatory, Morricone received 3 diplomas — in the class of trumpet (1946), instrumentation and composition.

When Morricone turned 16, he took the place of the second trumpet in the Alberto Flamini ensemble, in which his father had previously played. Together with the ensemble, Morricone worked part-time playing in nightclubs and hotels in Rome. A year later, he got a job at the theater, where he worked as a musician for one year, and then as a composer for three years. In 1950, he began arranging songs by popular composers for radio. He worked on processing music for radio and concerts until 1960, and in 1960 began arranging music for TV shows.

He began writing film music only in 1961, when he was 33 years old. He started with spaghetti westerns, a genre with which his name is now firmly associated. He became widely known after working on the films of his former classmate, director Sergio Leone. Later he worked with the largest Italian film directors — Bernardo Bertolucci, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Dario Argento, Salvatore Samperi and many others.

Since 1964, Morricone has worked at the RCA record company, where he arranged hundreds of songs, including for such celebrities as Gianni Morandi, Mario Lanza, Miranda Martino.

Having become famous in Europe, Morricone was invited to work in Hollywood cinema. In the USA, he wrote music for films by such famous directors as Roman Polanski, Oliver Stone, Brian De Palma, Mike Nichols, John Carpenter, Barry Levinson, Terrence Malick and others.

Ennio Morricone is one of the most famous composers of our time and one of the most famous film composers in the world. During his long career, he has composed music for more than 400 films and television series in Italy, Spain, France, Germany, Russia, and the USA.

As a film composer, he was nominated for an Oscar six times, and in 2007 he received an Oscar for outstanding contribution to cinema. In addition, in 1988, he was awarded a Grammy Award for the music for the film "Untouchables". In 1996, Morricone, together with photographer Augusto De Luca, received the "Cities of Rome" award for the book "Our Rome".

Contrary to popular belief, Morricone created not only soundtracks, he also wrote chamber instrumental music, with which he toured Europe in 1985, personally conducting the orchestra at concerts.

Twice during his career, he starred in films for which he wrote music, and in 1995 a documentary was made about him.

The American band Metallica has been opening every concert since the mid-1980s with the composition "The Ecstasy Of Gold" from the classic western "The Good, the Bad, the Evil". In 1999, she was played in the S&M project for the first time in a live performance (cover version).

Ennio Morricone was married and has four children:

Andrea — conductor, composer;

Marko works for the Copyright Society;

Alessandra is a surgeon;

Giovanni works for Universal.

He was seriously interested in chess, and repeatedly played with world champions.

Ennio Morricone died on July 6, 2020 at the age of 92 in a hospital in Rome, where he had been hospitalized a few days earlier with a fractured femur sustained as a result of a fall.

youtube

youtube

youtube

youtube

"It always hurts me when talented people die, because the world needs them more than heaven."

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg

#On this day#happy birthday#Ennio Morricone#film score#classical#absolute music#jazz#pop#avant garde#music#my music#music love#musica#history music#spotify#rock music#rock photography#my spotify#rock#Youtube

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

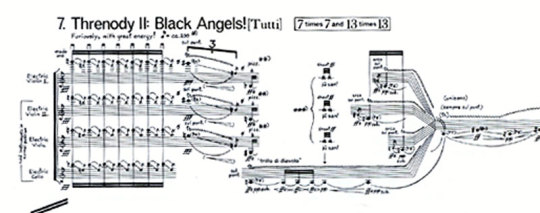

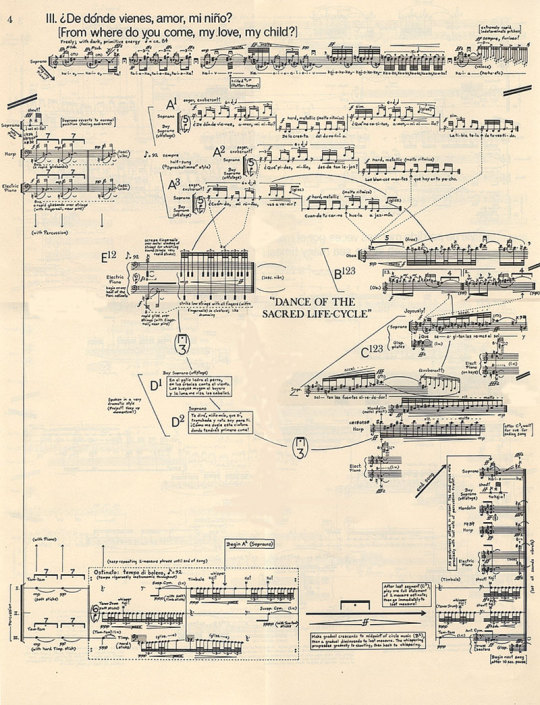

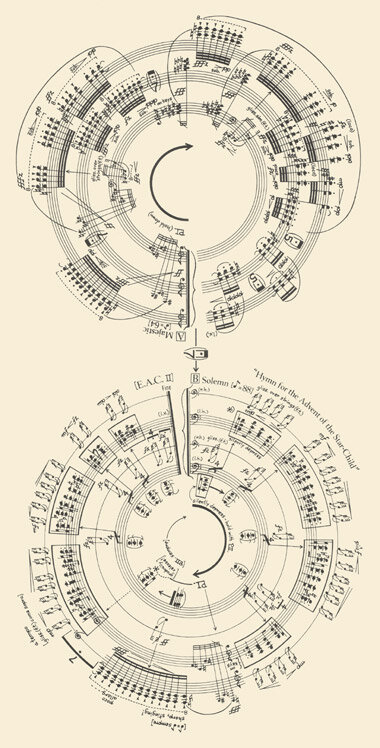

George Crumb (1929 - 2022) was known for his use of Graphic Musical Notation. Here are a few more

1K notes

·

View notes