#as much as they do (people whose lives and problems and societal marginalizations ACTUALLY matter)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

sometimes you see a bad tweet and it makes you upset all day but you cant interact with it in any way because then twitter will just be encouraged to show you more bad tweets. but it did ruin my whole fucking day

#anime life#the tweet was something like#'MAYBE when trans women talk about how bad testosterone is its because of their own trauma#and its not about trans men because literally nobody was talking about you guys oh my god'#like... ok...?#but trans men can still HEAR you tho....#i don't think its fair to act like trans men are self obsessed professional victims or whatever just because you said something shitty#like yes it's from your trauma and not about trans men but. yknow.#if i post about how ugly my fat body is#just because its coming from a place of trauma and societal abuse doesnt mean my comments don't hurt the other fat people who hear it#anyway i think part of why it's stuck with me all day is because it made me feel so sad#sometimes it feels like no one cares about me but me yknow?#like no one cares about trans mascs but other trans mascs#and no one cares about fat people but other fat people#and no one cares about disabled people but other disabled people#i KNOW that isn't true!!!#factually that is false#but sometimes it really feels like people only care about me in as much as they care about telling me i better not start thinking i matter#as much as they do (people whose lives and problems and societal marginalizations ACTUALLY matter)#and then if you try to talk about your problems to explain how theyre real you just get made fun of#oh well. time to get under my weighted blanket and get real small#and try not to get entirely black pilled by the world lol

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Chibi! I’m kind of obsessed with your blog. I’ve loved Kuro for a long time so it’s nice to see someone make very thoughtful posts about it. I was reading some of your posts about the kuro anime and was wondering. What is your opinion of the season 2 OVA The story of Will the reaper? I love the reapers so getting to know about their world is great, but will kicking grell’s ass was not great 😖.

【Response to: “are there any S1 or S2 OVAs you enjoyed?”】

Dear Dagonl,

Thank you very much for your interest! I’m happy you like my content, and it’s always nice to hear that somebody is interested in long-winded posts deep-analyses! ^^

Short answer:

As for my opinion on ‘The story of Will the Reaper’: as I said in the original post, in my opinion “[a]ll OVAs for the second season were (almost) as awful as the season itself, save for ‘The Making of [Kuroshitsuji]’.” Though, ‘the story of Will the reaper’ is actually the one that made me add the ‘almost’ in the previous sentence, meaning that it’s marginally better than the rest.

Click for Full Answer: The good things and the... awful things.

1. The good things

The reason I found this OVA marginally better is because I do respect the ambition and (attempt at) creativity the makers have shown. At the time of release the manga had not revealed anything yet about reaper origins. So I guess they could be forgiven for their artistic liberties (unlike the spoiler-revelation of Undertaker’s nature that ruined his big revelation in the manga.)

1.1. Fair world-building

The world-building works well with the idea of Yana’s satire on the Japanese Salaryman through William. As William is something of a self-proclaimed ‘model’ and so unforgivingly rigid, it gives us reason to believe the Reaper Dispatch Society is built on this type of ideal; aka the Japanese office environment. We have also seen that the technology of the Death Scythes is a century more advanced than Kuroshitsuji’s contemporaries, so the 1980s setting was well done in my opinion.

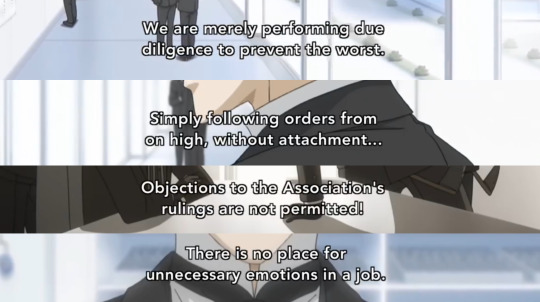

1.2. Fair reflection on reaper/Salaryman doctrine

The biggest critique on Salaryman culture is the robotic attitude employers demand. The Japanese Salaryman™ is expected to be no more than silent executors of the will from above. As explained by William, reapers don’t actually do all that much; all they do is meaningless double-checking JUST IN CASE something might be off.

As a satire this OVA is not ‘complete’ because you do need the information from the manga that came out many years later to understand why the reaper world is a satire in the first place for the actual punch. But in the very least the OVA pays adequate lip-service and does not disrespect the satirical origins of Yana’s design.

One thing this OVA does arguably better than even Yana is showing that most reapers are robotic work zombies like Will, rather than that the Dispatch Office is filled with eccentric youngsters as the named reapers of the series might suggest. (Though there is a downside that I will discuss in section 2.2.)

2. The awful things

So, to me this OVA has two good things, but they are insignificant in the face of the awful things that’s the rest of this OVA.

2.1. Raging homo and transphobia, etc.

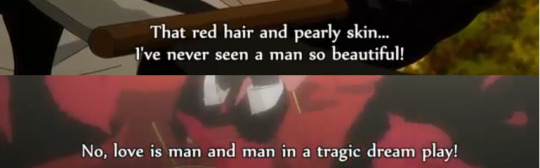

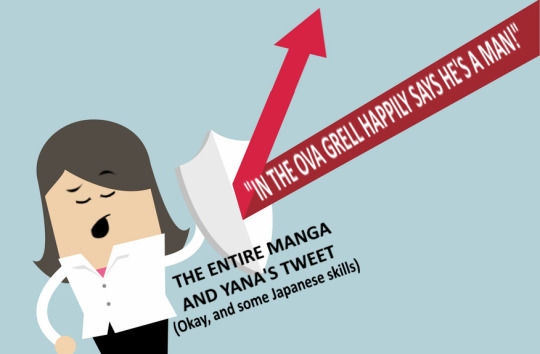

This OVA handles Grell extremely poorly. First of all, this OVA makes it explicit that Grell is a homosexual man, blatantly defying both canon and Yana’s explicit statement of her female gender. Why? Because the most obnoxious shippers want their Yaoi, and this sells. This one literally needed to sell because it’s an OVA.

As explained in more detail in this post, Grell was called a man and she eagerly responded “oh, yes”, and later she herself confirms this statement by making it explicit that she dreams of herself in a m/m relationship. (Yes, these subs are accurately translated. Click the link for a Japanese to English breakdown).

Some fans have explained this as Grell’s words before she realised her own identity, and I understand why. We all want something to not be this gross and try to make sense of the nonsensical, and some actual identity discovering journey would have been nice. For Grell as a character however, it only serves to give Man!Grellers more ammo (even though they have the destructive power of cotton wads).

As I said in the post linked above, “[if this statement] used to be [Grell’s] thoughts that are no longer relevant in present time, the script should have addressed that in present-timeline of the story. As it is now, it is clear as day that the writer Nemoto Toshizou did not take that into inconsideration.”

Secondly, this OVA is desperately trying to cater to Grelliam shippers. Fans have always come up with different reasons to ship this, but this OVA had to choose the most toxic one to capitalise on. Why make Grell so shitty to Will for no reason? Being degrading to him is one thing, but Grell was outright deadly violent to William for trying to do his job. And then Grell only stopped being so hostile because she got beaten back and therefore fell in love?

Yes, people justify this by saying that it’s charming to Grell because she’s a masochist, “whatever”. This however, paints a very askew image of real people who enjoy masochism as a kink. Any responsible adult in the SM community would tell you how painfully shallow Grell’s masochism is portrayed as, and how this portrayal takes away all accountability from someone who harms a kink-masochist if something went wrong.

This OVA would ironically have been more effective as an anti-Grelliam story, except that it sells itself as the opposite. With just the manga, people could just say: “oh, Grell doesn’t respect William’s personal boundaries, and William is very aggressive to Grell, but they can sort that out...eventually.” Add this OVA however, suddenly William is an indisputable abuse victim, and Grell is just an “in your face gay” (as the gay stereotype dictates...)

2.2. Contradicting Canon

I am actually not all that harsh about this OVA contradicting canon history because at the time of release nothing about the reapers had been revealed yet. Like I said above, I even respect the creativity to some extent. The only real problem is because this fandom tends to conflate canon with anime information by using cross-media information to understand Kuroshitsuji.

As discussed in section 1.2., the glimpses of the Reaper office are interesting, but the downside to this is that it suggests reapers are a race one is born into because all newbies are approximately the same age. Without the manga, this information in a vacuum is fine. Later however, Yana reveals that all reapers are suicides and are being punished for this sin. If a fan accepts both pieces of information and tries to piece them together, then suddenly this bit of creativity becomes a totalitarian nightmare.

People of all ages commit suicide. If a fan were to try shoehorn the OVA info into canon material (for lack of more stories), then we get: 1. reapers are suicides who get punished, and 2. all reaper newbies are approximately the same age and able bodied. The only conclusion we can draw then is that only able-bodied suicides who fit the ‘newbie age’ are punished. What happens to people who fall outside this norm? Is becoming a reaper and ‘paying off’ your sin the only way to “serve your term”? If so, then do suicides who fall outside this norm never get a chance to redeem themselves?😱 Or...... do only able-bodied youngsters get punished for committing suicide because they still had “societal value” but wasted it? Either way would be f*cked up!

But again, none of this is a real problem as long as a fan can distinguish canon from non-canon information ^^ So, moving on

2.3. Are reapers God Almighty?

Unlike the second, the third issue I have with the OVA is actually something I am quite harsh on. In this OVA we see that even trainees like William and Grell have apparent power to judge over somebody’s life and death based on their intellectual value. However, this begs for an urgent question!

Under section 3 of this post I discussed whether the law of “a human dies because a reaper says so” according to Grell would be feasible. It’s a relatively long discussion, so please click the link if you’re interested in the details. If you just want it to be quick then just ask the following question: “why give trainees/reapers with human subjectivity an almighty God’s** power to decide over life and death of others?” If we then add the manga’s canon information that reapers are being punished for having committed suicide, then why give people whose sin was ‘deciding over life and death wrongly FOR THEMSELVES’ the power to do so for OTHERS????

Still, even if we disregard the manga and view this OVA in a vacuum, it is still VERY alarming that trainees are given this power. Perhaps if a trainee misjudges there will be due consequences from above, but why give a trainee this power in the first place? Are human lives just test objects to this “reaper race”?

This third issue is so awful to me because it shows how little the OVA creators thought through matters and just wanted a quick money grab by selling the most toxic version of the Grelliam ship.

**TLN: A ‘shinigami’ is Japanese for ‘Death (shini) God (gami/kami)’, but please note that in Japanese definitions, a ‘kami’ is not ‘god’ in the same way it is in the Abrahamic sense. A ‘kami’ is more similar to a ‘spirit’, and is therefore not a supreme being. Entirely accurately, a ‘shinigami’ would be more similar to ‘death angel’ or ‘death spirit’.

Related posts:

Why would Sascha have committed suicide? Rutger, Will and the JP Salaryman

How does a scythe kill a reaper? A discussion of MBD musical’s horrible writing of universe laws, and canon reaper laws

Can reapers teleport?

A reaper’s dormitory

#Shinigami#reapers#reaper#Grell Sutcliff#William T. Spears#William#Shinigami Will's story#The story of Will the Reaper#OVA#Kuroshitsuji 2#Season 2#Black Butler OVA

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

I figured for you fine folks playing Persona 5 Royal, I'd take some time to write about some Japanese cultural features I learned while researching the game that might help some folks to contextualize the game's themes. I hope that this knowledge might enhance others' experiences with the game that way it has enhanced mine. Before I start, though, I'd like to start with two disclaimers: First, it's important to remember that while these cultural features might hold different levels of importance in our own respective cultures, that doesn't mean they're entirely alien to us, either. Bong Joon-ho said of the success of his film, Parasite, that "we all live in the same country now: that of capitalism," and that sentiment similarly applies to many of these other concepts. Much of what I'm writing about here are simply the Japanese flavor of power dynamics and societal structures we all live in, and I'm neither looking down on Japanese people nor claiming that my own culture is free of these power dynamics and societal structures when I identify them. Second, I'm not Japanese, and thanks to the Covid outbreak, I actually missed my shot to visit Japan. I have a close friend from Japan with whom I've discussed much of the research I've done, but I'd love to hear from other folks who are more familiar than I am. If I say something here that's inaccurate, or doesn't line up with your own experiences, let me know in the comments, or direct message my page! I've pulled much of this from a bunch of different academic sources, but unfortunately I've only got the one personal source with whom I can regularly discuss what I've learned, and he obviously can't be an expert at everything I've read about. The most central theme to Persona 5 is that of seki, which Joanna Liddle describes in "Rising Suns, Rising Daughters: Gender, Class, and Power in Japan" as "the idea that there is no proper place in society for a person who is not registered in an institution or organisation." Persona 5 is a game in which all of its characters are stuck on the margins of society, and playing it through the lens of seki helps to place this into sharp focus. Seki is best understood as the organization of society into in-groups and out-groups. In Yasuo Aoto's "Nippon: The Land and its People," he notes that this very strong consciousness of who is and isn't in groups can be attributed to historical factors, citing the need for joint cooperation in rice cultivation, the long history of feudalism, and the Confucian emphasis on belonging to a clan. The most clear example of a seki is the koseki family registration system, an outdated holdover from a bygone era, maintained for so long essentially to maintain some form of codified oppression of women after the current constitution bestowed them full rights. The koseki was once a fully public document that displayed the names of every member of a specific family. Women who married were stricken from their family's kosekis and written into their husband's kosekis instead, while women who divorced were stricken from those, finding themselves and any children they took with them without a family to which they officially belonged. Women who married into families without kosekis (to foreigners, for instance, or to a "mukosekisha," a person whose birth wasn't registered) were stricken from their own kosekis but weren't written into new ones, essentially making them less Japanese. Now, kosekis aren't accessible to the public, but they still legally enforce that certain people are less legitimate as citizens. In some ways, not being in a koseki provides similar issues as not having a birth certificate or social security number would in the states. This is a major factor in the stigma against divorcees, as it is common knowledge that a divorced woman and her children are not logged in any koseki. Most of the characters in Persona 5 are from broken families, which means that many of them are not in kosekis, and therefore on a cultural and legal level are less legitimately Japanese for it. Only one of Ann's parents is Japanese; Ryuji's mother divorced her husband; Yusuke, Futaba, and Akechi are orphans. However, seki as a concept is broader than this. One's family is a seki, but so is the company for which they work, their group of friends, their group of coworkers, their classmates, clubs or social groups to which they belong. Sataka Makoto writes in "105 Key Words for Understanding Japan": "There are only a very few people who hop jobs or religions. Job-hoppers are criticized as unstable characters and 'isshakenmei,' [or] devotion to one company, is considered better than 'isshoukenmei,' [or] trying one’s best (....) The Japanese companies are still very much like feudal clans. The top position is often hereditary, like that of a feudal lord, but the employees don’t complain strongly." This strong devotion to one's company has been purposely cultivated to suppress class consciousness. It's commonly believed in Japan that over 90% of Japanese people are middle class. Nakane Chie states that social stratification in Japan is broken up vertically, between companies, rather than horizontally, between classes, saying that, "it is not really a matter of workers struggling against capitalists or managers but of Company A ranged against Company B (...) [they] do not stand in vertical relationship to each other but instead rub elbows from parallel positions." Obviously, it's not true that Japanese is almost entirely middle class; Liddle notes that the economists who argued this defined members of the same class as "homogeneous in lifestyle, attitudes, speech, dress and other status dimensions," but that there is still much variance in assets and vulnerability to economic change. On top of this, the ruling class does still function as a bloc, acting with much more class unity than the working class does. Persona 5 discusses the drastic amount of worker exploitation in the Okumura dungeon. The game shows us "karoshi," a term that literally just means dying from working too much, which is a common occurrence in Japan, and absolutely a result of exploitation of the proletariat by the ruling classes. It's hard to fight back against this exploitation, though, because of the vertical stratification of workers into different corporations. It's a major barrier to class solidarity when workers from two different companies see themselves as being members of different sekis, and therefore not really meant to interact all that much. There's more I'd like to write, especially about the single-party system and just how much Shido is mean to represent Shinzo Abe, but it's almost 4 AM, so I'd better hold off on that. Anyone who's interested in the Koseki can read at least parts of Gender and the Koseki in Contemporary Japan on google books: https://books.google.com/books?id=gR9WDwAAQBAJ This article from 2016 on the koseki system is a quicker read and helps to bring to light some of the system issues: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2016/07/10/issues/japans-discriminatory-koseki-registry-system-looks-ever-outdated/ Part of Rising Suns, Rising Daughters is on google books, and it's a fascinating read if you're interested in class, gender, and the intersections between the two: https://books.google.com/books?id=X7h_6gCRuAUC This article was a good jumping-off point to start seeing some of the real issues discussed in Persona 5: https://www.usgamer.net/articles/the-real-world-problems-behind-persona-5

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

It has been hard to measure the effects of the novel coronavirus. Not only is COVID-19 far-reaching — it’s touched nearly every corner of the globe at this point — but its toll on society has also been devastating. It is responsible for the deaths of over 905,000 people around the world, and more than 190,000 people in the United States alone. The associated economic fallout has been crippling. In the U.S., more people lost their jobs in the first three months of the pandemic than in the first two years of the Great Recession. Yes, there are some signs the economy might be recovering, but the truth is, we’re just beginning to understand the pandemic’s full impact, and we don’t yet know what the virus has in store for us.

This is all complicated by the fact that we’re still figuring out how best to combat the pandemic.Without a vaccine readily available, it has been challenging to get people to engage in enough of the behaviors that can help slow the virus. Some policy makers have turned to social and behavioral scientists for guidance, which is encouraging because this doesn’t always happen. We’ve seen many universities ignore the warnings of behavioral scientists and reopen their campuses, only to have to quickly shut them back down.

But this has also meant that there are a lot of new studies to wade through. In the field of psychology alone, between Feb. 10 and Aug. 30, 541 papers about COVID-19 were uploaded to the field’s primary preprint server, PsyArXiv. With so much research to wade through, it’s hard to know what to trust — and I say that as someone who makes a living researching what types of interventions motivate people to change their behaviors.

As I tell my students, if you want to use behavioral science research to address real-world problems, you have to look very closely at the details. Often, a simple question like, “What research should policy makers and practitioners use to help combat the pandemic?” is surprisingly difficult to answer.

For starters, there are often key differences between the lab (or the people and situations some social scientists typically study as part of our day-to-day research) and the real world (or the people and situations policy-makers and practitioners have in mind when crafting interventions).

Take, for example, the fact that social scientists tend to study people from richer countries that are generally highly educated, industrialized, democratic and in the Western hemisphere. And some social scientific fields (e.g., psychology) focus overwhelmingly on whiter, wealthier and more highly educated groups of people within those nations.

This is a major issue in the social sciences and something that researchers have been talking about for decades. But it’s important to mention now, too, as Black and brown people have been disproportionately affected by the coronavirus — they are dying at much higher rates than white people and working more of the lower-paying “essential” jobs that expose them to greater risks. Here you can start to see very real research limitations creep in: The people whose lives have been most adversely affected by the virus have largely been excluded from the studies that are supposed to help them. When samples and the methods used are not representative of the real world, it becomes very difficult to reach accurate and actionable conclusions.

Additionally, the things we have participants do, or report that they are going to do in the laboratory, do not always map onto how they behave in real life. Take, for example, wearing face masks — something many Americans are still not doing. Convincing people to wear masks sounds like it should be easy to fix, but understanding why they’re not wearing masks in the first place is pretty complicated. It might be a risk perception problem (they don’t perceive COVID-19 to be that risky, or they underestimate their likelihood of getting infected). Or maybe it’s a perceived efficacy problem (they don’t think wearing the masks will actually reduce their risk). Or maybe it’s even a norm perception problem (they don’t think anyone else is wearing masks).

Understanding why people are choosing not to wear masks is important because if the goal is to design a successful intervention to change this behavior, we then as social scientists must first figure out which of these reasons — or more likely, which combination of them — is the root of the problem. Until we know what is driving much of the behavior we see, we cannot generate effective solutions for changing that behavior. And all this doesn’t even take into account that we now live in a world where everything — including the pandemic — is politicized, which also affects whether people are willing to pay attention to the messages in an intervention.

Research on other infectious diseases has shown that who is doing the intervening (i.e., who is delivering the message) matters, as experts are often more effective than non-experts. Studies have also shown it helps if the person doing the intervention shares characteristics, such as gender or race, with the people for whom the messaging is targeted. Additionally giving people laundry lists of things they can’t do is less helpful than providing them with a reasonable number (e.g., two to three) of things they can do.

Lastly, researchers need to address the seemingly cold and calculating question of whether an intervention is cost-effective. Resources are limited — especially in a situation like a pandemic — so social scientists are also trying to factor in which interventions are likely to have the biggest societal effect. To do that, we have to look at things like “effect sizes” of previous studies and translate them into pandemic-relevant metrics.

For instance, if we developed a message to increase mask-wearing and persuaded policymakers to buy air time in all 210 U.S. media markets, how much of an increase in mask-wearing should we expect? One percent? Five percent? The answer to that matters a great deal, because we have to decide whether that is a better or worse use of (limited) resources than investing in other strategies, such as more COVID-19 tests — something the U.S. also doesn’t have enough of.

Ultimately, figuring these things out often takes time, and it’s important for scientists and policymakers to acknowledge that. We need to say what we don’t know and when we need more time. After all, there’s a risk of acting too quickly, before we actually understand the problem or the effects an intervention might have. Being overconfident and wrong can come with very real costs: We in the scientific community lose future credibility and trustworthiness (not to mention the costs associated with any harm done between the initial flawed intervention and the eventual correct one). Think about the early messaging around face masks, which was fairly opaque. As some countries mandated masks, figures like the U.S. surgeon general tweeted that masks are “NOT effective.” Of course, scientists and policymakers later had to backtrack when studies showed that wearing masks is effective for reducing transmission of COVID-19.

And that brings me to one last thing I want to discuss: the ethics of scientific research. Data can be instructive, but it does not speak for itself. Behind every data point is a person. And with something like the coronavirus, where people are so deeply affected, we have to think about the ethics of intervening in people’s lives. Those ethics again involve considering things like who is represented in, versus missing from, the data we use and whose lives will be affected by those decisions.

Extreme levels of inequality in the U.S. and around the world have created power imbalances that often result in uneven distribution of the risks and benefits of interventions. Some groups are subject to disproportionate risks so that other groups reap disproportionate benefits. As a result, policy decisions often have winners and losers, and in both historical and modern society — including the COVID-19 era — the people who lose are usually those already on the margins of society. We have to remember that, and be vigilant in our efforts so that we do not reproduce these patterns.

I was reminded of this when I read a FiveThirtyEight article on changes in public opinion about reopening the economy. The article noted that between March and June, polling data showed a 22 percent increase in the share of Americans who said the government should allow businesses to open back up, even if it meant putting some people at risk. On its surface, that looks like a large increase in support for reopening the economy, and thus reopening might seem supported by the public. But looking closer, it becomes clear why it may be unwise to act on that evidence on its own: The observed trend was largely among white Americans. Eighty-two percent of Black Americans still thought that public health should be prioritized over the economy — roughly unchanged from March. White Americans had changed their minds: 49 percent thought the government should reopen the economy, even if it means putting some people at risk, compared with 24 percent in March.

This is an important reminder that the pandemic has not been the “great equalizer,” as it was initially described. The racial disparities in the pandemic have been so stark that early estimates suggest that about one in 2,000 of the entire Black population in the U.S. has died from COVID-19. It is therefore imperative we consider these different experiences of the coronavirus when considering what research we should use when responding to the pandemic.

Who is included in the data we’re using? And who isn’t? If we heavily weigh the opinions and other data gathered from one group as we design interventions, what happens to other groups? These real-world differences matter, and matter greatly. We have to ask ourselves those questions as scientists and remember that — especially in times like the pandemic era we’re living in — we’re betting people’s lives on the answers to those questions.

0 notes

Link

“We think of capitalism as being locked in an ideological battle with socialism, but we never really saw that capitalism might be defeated by its own child — technology.”

This is how Eric Weinstein, a mathematician and a managing director of Peter Thiel’s investment firm, Thiel Capital, began a recent video for BigThink.com. In it he argues that technology has so transformed our world that “we may need a hybrid model in the future which is paradoxically more capitalistic than our capitalism today and perhaps even more socialistic than our communism of yesteryear.”

Which is another way of saying that socialist principles might be the only thing that can save capitalism.

Weinstein’s thinking reflects a growing awareness in Silicon Valley of the challenges faced by capitalist society. Technology will continue to upend careers, workers across fields will be increasingly displaced, and it’s likely that many jobs lost will not be replaced.

Hence many technologists and entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley are converging on ideas like universal basic income as a way to mitigate the adverse effects of technological innovation.

I reached out to Weinstein to talk about the crisis of capitalism — how we got here, what can be done, and why he thinks a failure to act might lead to a societal collapse. His primary concern is that the billionaire class — which he’s not a part of, but has access to through his job — has been too slow to recognize the need for radical change.

“The greatest danger,” he told me, is that, “the truly rich are increasingly separated from the lives of the rest of us so that they become largely insensitive to the concerns of those who still earn by the hour.” If that happens, he warns, “they will probably not anticipate many of the changes, and we will see the beginning stirrings of revolution as the cost for this insensitivity.”

You can read our lightly edited conversation below.

Sean Illing

The phrase “late capitalism” is in vogue these days. Do you find it analytically useful?

Eric Weinstein

I find it linguistically accurate and politically provocative. I don’t think that what is to follow is going to be an absence of markets. I don’t think the implications are that capitalism is failing and will be replaced by anarchy or socialism. I think it’s possible that this is merely the end of the beginning of capitalism, and that its next stage will continue many of its basic tenets, but in an almost unrecognizable form.

Sean Illing

I want to ask you about what that next stage might look like, but first I wonder if you think market capitalism has outlived its utility?

Eric Weinstein

I believe that market capitalism, as we’ve come to understand it, was actually tied to a particular period of time where certain coincidences were present. There’s a coincidence between the marginal product of one’s labor and one’s marginal needs to consume at a socially appropriate level. There’s also the match between an economy mostly consisting of private goods and services that can be taxed to pay for the minority of public goods and services, where the market price of those public goods would be far below the collective value of those goods.

Beyond that, there’s also a coincidence between the ability to train briefly in one’s youth so as to acquire a reliable skill that can be repeated consistently with small variance throughout a lifetime, leading to what we’ve typically called a career or profession, and I believe that many of those coincidences are now breaking, because they were actually never tied together by any fundamental law.

Sean Illing

A big part of this breakdown is technology, which you rightly describe as a child of capitalism. Is it possible the child of capitalism might also become its destroyer?

Eric Weinstein

It’s an important question. Since the Industrial Revolution, technology has been a helpful pursuer, chasing workers from the activities of lowest value into repetitive behaviors of far higher value. The problem with computer technology is that it would appear to target all repetitive behaviors. If you break up all human activity into behaviors that happen only once and do not reset themselves, together with those that cycle on a daily, weekly, monthly, or yearly basis, you see that technology is in danger of removing the cyclic behaviors rather than chasing us from cyclic behaviors of low importance to ones of high value.

Protesters march during the G20 summit. Getty Images

Sean Illing

That trend seems objectively bad for most people, whose work consists largely of routinized actions.

Eric Weinstein

I think this means we have an advantage over the computers, specifically in the region of the economy which is based on one-off opportunities. Typically, this is the province of hedge fund managers, creatives, engineers, anyone who’s actually trying to do something that they’ve never done before. What we’ve never considered is how to move an entire society, dominated by routine, on to a one-off economy in which we compete, where we have a specific advantage over the machines, and our ability to do what has never been done.

Sean Illing

This raises a thorny question: The kinds of skills this technological economy rewards are not skills that a majority of the population possesses. Perhaps a significant number of people simply can’t thrive in this space, no matter how much training or education we provide.

Eric Weinstein

I think that’s an interesting question, and it depends a lot on your view of education. Buckminster Fuller (a prominent American author and architect who died in 1983) said something to the effect of, “We’re all born geniuses, but something in the process of living de-geniuses us.” I think with several years more hindsight, we can see that the thing that de-geniuses us is actually our education.

The problem is that we have an educational system that’s based on taking our natural penchant for exploration and fashioning it into a willingness to take on mind-numbing routine. This is because our educational system was designed to produce employable products suitable for jobs, but it is jobs that are precisely going to give way to an economy increasingly based on one-off opportunities.

Sean Illing

That’s a problem with a definable but immensely complicated solution.

Eric Weinstein

Part of the question is, how do we disable an educational system that is uniformizing people across the socioeconomic spectrum in order to remind ourselves that the hotel maid who makes up our bed may in fact be an amateur painter? The accountant who does our taxes may well have a screenplay that he works on after the midnight hour? I think what is less clear to many of our bureaucrats in Washington is just how much talent and creativity exists through all walks of life.

What we don’t know yet is how to pay people for those behaviors, because many of those screenplays and books and inventions will not be able to command a sufficiently high market price, but this is where the issue of some kind of hybridization of hypercapitalism and hypersocialism must enter the discussion.

“We will see the beginning stirrings of revolution as the cost for this continuing insensitivity”

Sean Illing

Let’s talk about that. What does a hybrid of capitalism and socialism look like?

Eric Weinstein

I don’t think we know what it looks like. I believe capitalism will need to be much more unfettered. Certain fields will need to undergo a process of radical deregulation in order to give the minority of minds that are capable of our greatest feats of creation the leeway to experiment and to play, as they deliver us the wonders on which our future economy will be based.

By the same token, we have to understand that our population is not a collection of workers to be input to the machine of capitalism, but rather a nation of souls whose dignity, well-being, and health must be considered on independent, humanitarian terms. Now, that does not mean we can afford to indulge in national welfare of a kind that would rob our most vulnerable of a dignity that has previously been supplied by the workplace.

People will have to be engaged in socially positive activities, but not all of those socially positive activities may be able to command a sufficient share of the market to consume at an appropriate level, and so I think we’re going to have to augment the hypercapitalism which will provide the growth of the hypersocialism based on both dignity and need.

Sean Illing

I agree with most of that, but I’m not sure we’re prepared to adapt to these new circumstances quickly enough to matter. What you’re describing is a near-revolutionary shift in politics and culture, and that’s not something we can do on command.

Eric Weinstein

I believe that once our top creative class is unshackled from those impediments which are socially negative, they will be able to choose whether capitalism proceeds by evolution or revolution, and I am hopeful that the enlightened self-interest of the billionaire class will cause them to take the enlightened path toward finding a rethinking of work that honors the vast majority of fellow citizens and humans on which their country depends.

Sean Illing

Are you confident that the billionaire class is so enlightened? Because I’m not. All of these changes were perceptible years ago, and yet the billionaire class failed to take any of this seriously enough. The impulse to innovate and profit subsumes all other concerns as far as I can tell.

Eric Weinstein

That’s curious. There was a quiet shift several years ago where the smoke-filled rooms stopped laughing about inequality concerns and started taking them on as their own even in private. I wish I could say that change was mediated out of the goodness of the hearts of the most successful, but I think it was actually a recognition that we had gone from a world in which people were complaining about inequality that should be present based on differential success to an economy which cannot possibly defend the level of inequality based on human souls and their needs.

I think it’s a combination of both embarrassment and enlightened self-interest that this class — several rungs above my own — is trying to make sure it does not sow the seeds of a highly destructive societal collapse, and I believe I have seen an actual personal transformation in many of the leading thinkers among the technologists, where they have come to care deeply about the effects of their work. Few of them want to be remembered as job killers who destroyed the gains that have accumulated since the Industrial Revolution.

So I think that in terms of wanting to leave a socially positive legacy, many of them are motivated to innovate through concepts like universal basic income, finding that Washington is as bereft of new ideas in social terms as it is of new technological ones.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg delivers the keynote address at Facebook’s F8 Developer Conference on April 18, 2017, at McEnery Convention Center in San Jose, California. Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Sean Illing

But how did we allow things to get so bad? We’ve known for a long time that political systems tend to collapse without a robust middle class acting as a buffer between the poor and the rich, and yet we’ve rushed headlong into this unsustainable climate.

Eric Weinstein

I reached a bizarre stage of my life in which I am equally likely to fly either economy or private. As such, I have a unique lens on this question. A friend of mine said to me, “The modern airport is the perfect metaphor for the class warfare to come.” And I asked, “How do you see it that way?” He said, “The rich in first and business class are seated first so that the poor may be paraded past them into economy to note their privilege.” I said, “I think the metaphor is better than you give it credit for, because those people in first and business are actually the fake rich. The real rich are in another terminal or in another airport altogether.”

It seems to me that the greatest danger is that the truly rich, I’m talking nine and 10 figures rich, are increasingly separated from the lives of the rest of us so that they become largely insensitive to the concerns of those who still earn by the hour. As such, they will probably not anticipate many of the changes, and we will see the beginning stirrings of revolution as the cost for this insensitivity.

However, I am hopeful that as social unrest grows, the current political system of throwing the upper middle class and lower rungs of the rich to the resentful lower middle class and poor will come to an end if only for the desire of the truly well-off to avoid a genuine threat to the stability on which they depend, and the social stability on which they depend.

Sean Illing

I suppose that’s my point. If the people with the power to change things are sufficiently cocooned that they fail to realize the emergency while there’s still time to act, where does that leave us?

Eric Weinstein

Well, the claim there is that there will be no warning shots across the bow. I guarantee you that when the Occupy Wall Street demonstrators left the confines of Zuccotti Park and came to visit the Upper East Side homes of Manhattan, it had an immediate focusing on the mind of those who could deploy a great deal of capital. Thankfully, those protesters were smart enough to realize that a peaceful demonstration is the best way to advertise the potential for instability to those who have yet to do the computation.

“We have a system-wide problem with embedded growth hypotheses that is turning us all into scoundrels and liars”

Sean Illing

But if you’re one of those Occupy Wall Street protesters who fired off that peaceful warning shot across the bow six years ago, and you reflect on what’s happened since, do have any reason to think the message was received? Do you not look around and say, “Nothing much has changed”? The casino economy on Wall Street is still humming along. What lesson is to be drawn in that case?

Eric Weinstein

Well, that’s putting too much blame on the bankers. I mean, the problem is that the Occupy Wall Street protesters and the bankers share a common delusion. Both of them believe the bankers are more powerful in the story than they actually are. The real problem, which our society has yet to face up to, is that sometime around 1970, we ended several periods of legitimate exponential growth in science, technology, and economics. Since that time, we have struggled with the fact that almost all of our institutions that thrived during the post-World War II period of growth have embedded growth hypotheses into their very foundation.

Sean Illing

What does that mean, exactly?

Eric Weinstein

That means that all of those institutions, whether they’re law firms or universities or the military, have to reckon with steady state [meaning an economy with mild fluctuations in growth and productivity] by admitting that growth cannot be sustained, by running a Ponzi scheme, or by attempting to cannibalize others to achieve a kind of fake growth to keep those particular institutions running. This is the big story that nobody reports. We have a system-wide problem with embedded growth hypotheses that is turning us all into scoundrels and liars.

Sean Illing

Could you expound on that, because this is a foundational problem and I want to make sure the reader knows exactly what you mean when you say “embedded growth hypotheses” are turning us into “scoundrels and liars.”

Eric Weinstein

Sure. Let’s say, for example, that I have a growing law firm in which there are five associates at any given time supporting every partner, and those associates hope to become partners so that they can hire five associates in turn. That formula of hierarchical labor works well while the law firm is growing, but as soon as the law firm hits steady state, each partner can really only have one associate, who must wait many years before becoming partner for that partner to retire. That economic model doesn’t work, because the long hours and decreased pay that one is willing to accept at an entry-level position is predicated on taking over a higher-lever position in short order. That’s repeated with professors and their graduate students. It’s often repeated in military hierarchies.

It takes place just about everywhere, and when exponential growth ran out, each of these institutions had to find some way of either owning up to a new business model or continuing the old one with smoke mirrors and the cannibalization of someone else’s source of income.

Sean Illing

So our entire economy is essentially a house of cards, built on outdated assumptions and pushed along with gimmicks like quantitative easing. It seems we’ve gotten quite good at avoiding facing up to the contradictions of our civilization.

Eric Weinstein

Well, this is the problem. I sometimes call this the Wile E. Coyote effect because as long as Wile E. Coyote doesn’t look down, he’s suspended in air, even if he has just run off a cliff. But the great danger is understanding that everything is flipped. During the 2008 crisis, many commentators said the markets have suddenly gone crazy, and it was exactly the reverse. The so-called great moderation that was pushed by Alan Greenspan, Timothy Geithner, and others was in fact a kind of madness, and the 2008 crisis represented a rare break in the insanity, where the market suddenly woke up to see what was actually going on. So the acute danger is not madness but sanity.

The problem is that prolonged madness simply compounds the disaster to come when sanity finally sets in.

Original Source -> Why capitalism won’t survive without socialism

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

Since Donald Trump won the US presidential election one year ago, the games sector has tried to work out how to use our medium to resist the rise of the far right. In March, Resistjam brought game developers together around the world to create consciousness-raising works of political art. Rami Ismail is one developer who has used his platform as a respected public speaker at games conferences to speak out against Trump’s discriminatory travel ban and elevate the voices of developers whose work has been affected. Games criticism outlet Waypoint’s remarkable first year included a week-long special feature on the prison-industrial complex.

Videogames and neoliberalism

Class politics of digital media

Art as political response

How to use games politically

References

One year on, it may now be a good time to evaluate the cultures of resistance that are growing in games. What does it mean to resist fascism with games and tech? How can the videogames and technology industries confront our role in fostering cultures of isolated young men who become radicalised? Does it still make sense to focus on videogames at a time like this?

Videogames and neoliberalism

“Duke Nukem’s Dystopian Fantasies” appeared on Jacobin on April 20th, marking a debut post for writer and artist Liz Ryerson on the leftist commentary site. In it, she makes the affirmative case for looking at videogames as historical and cultural artefacts while judging them on their own merits, and makes the connection between the male power fantasy the game embraces, the alienation people feel under late capitalism, and how that can translate into reaction without a coherent understanding of history.

“This is the power of the fantasy Duke Nukem as a cultural figure represents: that through raw machismo, the series of oppressive neoliberal forces that form the framework of our society can be conquered and transcended. Duke cannot exist in a rational world. He can only exist in a one filled with internal contradictions, crossed wires, and broken down buildings.

“His world is never stable. It can only ever be dominated by irrational fears of the unknown and one-dimensional, cartoonish archetypes. His world never resolves any of its cognitive dissonances, and sometimes even seems to be aware of its own self-destructiveness.”

Liz Ryerson (2017) “Duke Nukem’s Dystopian Fantasies”, Jacobin

For the most part, Ryerson’s piece received praise from leftist partisans whether or not they were particularly committed to videogames as a craft. But not everyone felt it was appropriate for a socialist journal like Jacobin to have published a close reading of something like Duke Nukem 3D.

https://twitter.com/garliccorgi/status/855241007692210177

It’s not as if they’d ever previously published pieces on the art, culture and business of games or tech, to relatively little backlash:

Les Simerables, Eva Koffman “SimCity isn’t a sandbox. Its rules reflect the neoliberal common sense of today’s urban planning.”

Empire Down, Sam Kriss “The player in Age of Empires II doesn’t take on the role of a monarch or a national spirit, but the feudal mode of production itself.”

“You can sleep here all night”: Video Games and Labour, Ian Williams “Exploitation in the video game industry provides a glimpse at how many of us may be working in years to come.”

In my own experience occupying the art fringe of the videogame industry–which is admittedly a highly reactionary space–I’ve learned that while there are a lot of young people pouring a lot of energy into their craft, it’s easy to feel lonely and beholden to a lost cause. I’ve worked as a writer and small-time artist and developer for almost a decade, focusing primarily on indie and alternative development communities and agitating in my limited capacity for more of a spotlight on them, their histories, and the labour involved in them. My political activity outside of my work consists largely of anti-fascist organizing in my city–that means participating in teach-ins, free food events, as well as protests and counter-demonstrations against the far-right. This work is voluntary, but can sometimes feel much more fulfilling than my actual profession. It’s easy to feel like no one really cares about fringe technical arts because, well, most people don’t. If the industry’s flagship mainstream titles give us very little to seriously engage with, then why bother digging any deeper?

[bctt tweet=”Political critique of AAA games is a lot of work, for something juvenile at worst, and culturally peripheral at best.” via=”no”]

As the Jekyll that is liberalism has once again fallen into crisis and gives way to its Mr. Hyde that is fascist reaction, I’ve felt increasingly insecure about the nature of my work and why I chose it. I laugh nervously and tell people what I do is bullshit before going any further. Luckily, most of the people I’ve encountered while organizing, or even just through having had a political affinity online, have expressed genuine interest in the medium, the inner workings of our opaque and cloistered industry, and its potential as an expressive and communicative tool. Still, I have met those who think of things like social media as “inappropriate technology”, who automatically assume that anyone who has any interest in videogames is a pepe nazi, or who think of any engagement with new media as a cultural and political dead end.

That said, some of the most personally influential leftist thinkers I’ve come across are also writers, artists and academics in this incredibly weird field. More often than not we organize and march together. This is not an attempt to scapegoat anyone specific or to do as so many desperate thinkpieces did after the election and try to reaffirm the dubious political importance of games as an artform through headlines such as “Trump as Gamer-in-Chief”.

I don’t think that making videogames, no matter how fringe or alt, should be conflated with tried and true forms of street activism. Game jams about the immigration ban are not a form of direct action in the way shutting down a consulate or doing an hours-long sit-in at an airport are. Your app is not saving the world.

ResistJam was an online game jam about resisting authoritarianism. Over 200 games were made by participants.

The dominant ideological expression of late capitalism is liberalism, or more specifically, neoliberalism. Liberalism prefers to try to diversify the middle class of the currently existing system, rather than try imagining something that might liberate greater masses of people. According to this view, capitalism fundamentally works, only needing a slight tweak here or there to make it more “accessible” to those who are deserving. A major way it seeks to accomplish this is by centering symbolic representation of various marginalized identities while also depoliticizing things like technological progress, framing them as inherently good and proof of societal advancement. All actual material concerns and real struggle can then be ironed away in favour of simply trying to optimize the level of participation for marginalized groups, as one would fiddle with a dial. This isn’t to say symbolic representation doesn’t matter, but to fixate on it strips us of the ability to think in terms of collective political power, and cultivate a real political program that fights for material improvements to people’s lived conditions.

Class politics of digital media

Media consumption doesn’t determine political outcomes, at least not in a direct sense, but it does help shape people’s political imaginations. Taking the time to unpack the media we consume can tell us a lot about the conditions of production–that is to say, the ways in which labour power is exploited in order to produce entertainment commodities. This may include the mining of cobalt to make computer hardware, or the manufacturing of consoles and other devices at Foxconn plants, or developers coerced into overwork in order to meet production quotas. There is a potentially international struggle of exploited workers even just when it comes to videogames, yet hardly a labour movement to speak of. That there’s hardly a union presence in the technical arts or in tech work broadly, and that these industries tend toward meritocratic, libertarian or even fascist thinking that tends to be expressed ideologically via their major cultural properties, is not an accident.

Conversely, if politics are the “art of the possible”, then media creation allows us to expand the conceptual scope for what’s possible. Most of the art we consume is conservative in character–even works we consider liberal or progressive are often deeply reactionary in their base assumptions. For example, David Grossman explains why diverse Brooklyn Nine-Nine can’t avoid being apologia for the NYPD, and why using progressive representation to paper over the faults of repressive institutions is indefensible.

Earlier this year, the Vera Institute of Justice polled young people in high-crime areas of New York, and found that only four in ten respondents would feel comfortable seeking help from the police if they were in trouble, and eighty-eight percent of young people surveyed didn’t believe that their neighborhoods trusted the police. Forty-six percent of young people said they had experienced physical force beyond being frisked by a police officer.

“Brooklyn Nine-Nine” tries to get around this problem by pretending the actual Brooklyn doesn’t exist.

David Grossman (2013) “If you think the NYPD is like Dunder Mifflin, you’ll love ‘Brooklyn Nine-Nine'”, New Republic

Videogames in particular have their own sordid history of using diversity rhetoric as a way to deflect criticism of unwieldy, increasingly shoddy games produced under highly exploitative conditions, and reflect profoundly disturbing ideological tendencies (sometimes with the help of the arms industry or the U.S. military.) This has led some leftists to believe that the interactive arts as a craft are inherently reactionary and devoid of creative potential. I sympathize to an extent with this position, but having spent significant time in tech and games spaces, I believe these problems arise from the same historical conditions that render most art conservative, as well as specific ones owing to the opaqueness of the industry itself. I think these are things that can be overcome, not without some effort, and part of what keeps me interested in games is its creative fringe, where artists are finding ways to use the medium to capture as well as suggest alternatives to our current predicament.

[bctt tweet=”Videogames have matured entirely within the context of late capitalism and neoliberalism.” via=”yes”]

Videogames have barely a labour movement to speak of, and are an appendage of the tech-libertarian culture of Silicon Valley. An important aspect of their heritage resides in engineers meddling with MIT military computers. They have never, in their production or conception, been entirely separate from the state or the military-industrial complex or from corporate interest, and as a result often exist as an ideological expression of these institutions.

Maybe this was unavoidable, the forces underlying the technical arts world too strong to ever be meaningfully opposed by a few dissenting voices, but I struggle to think of anything in the modern world for which this is not true. Maybe a game jam, or a book fair, or a block party should not be the centerpieces of our activism. These things have their place, but should not be confused for things like street actions (protests, counter-demonstrations against the far-right), grassroots electoral activism, coalition-building between social and economic justice groups, public disobedience (like the destruction of hostile architecture), accessibility and anti-poverty efforts, workplace organizing and so on. This work can be thankless and grueling, but it’s absolutely vital. Still, engaging with media and culture in a way that actually resonates with alienated people is a good way to let them know there’s something else available to them than resigned helplessness. Perhaps it seems like too much effort for too small and marginal a community, but going to any independent games site will bring up literally thousands of entries, much of it being made by people under the age of 30. Many of these people work multiple jobs while making their art for free or almost free, or work under precarious conditions (employment instability, contract work, etc,) and scrape by on crowdfunding, and many–as I’ve experienced both by playing their works and by actually building relationships with them–lean acutely left and hunger for more robust progressive spaces that reward creative experimentation, but often lack the time, energy or organizational guidance that would help them achieve those goals.

But even more broadly, more people play games than identify strictly as “gamers.” Plenty of people who do work in the industry recognize this term as a corporate invention, and don’t actually resemble the stereotype of the socially-awkward, emotionally stunted, self-pitying bourgeois recluses that so much of the industry has historically built its marketing around. While mainstream ideologies in the subculture tend to range from milquetoast liberalism to right-wing libertarianism to cryptofascism, quite a lot more people consume media like games, comics and even anime than are intimately involved with the worst elements of these subcultures. Snobbishly refusing to make any use of these “deviant” or “degenerate” new forms and reacting with hostility at anyone who tries to strikes me as missing an opportunity, and as needlessly ceding cultural ground to people we seek to oppose at every level.

Art as political response

Though GamerGate is nearly incomprehensible to anyone who hasn’t been following it closely, it’s unusual in that it captured the attention of people who have nothing all to do with video games when it’s ostensibly preoccupied with whether certain online blogs have properly disclosed their writers’ ties to indie game developers. A recent post at Breitbart, however, helps to explain GamerGate’s appeal: It’s an accessible front for a new kind of culture warrior to push back against the perceived authoritarianism of the social-justice left.

Vlad Chituc (2015) “Gamergate: A culture war for people who don’t play video games”, New Republic

Reactionaries–from bog standard republicans to the fractured jumble of fascoid revanchists that make up the so-called “alt-right”–have for a long time viewed nerd culture as part of the broader culture war. This is why Gamergate attracted conservative figures like Christina Hoff Sommers, Todd Kincannon and Milo Yiannopoulos (both disgraced), Paul Joseph Watson, Mike Cernovich and so on. I don’t think gaming or memes really impacted, say, the election, and I tend to think the way we talk about Gamergate–as though it’s the cause of, rather than a product of, the resurgence of the far-right��misses the forest for the trees. I don’t think leftist and labour activists ought to go out of their way to address these hard-identified gamers either. There’s no reason for us not to remain critical of the industry and the ideologies it reproduces.

But it’s obvious that this is a group that gets really anxious when they start to feel like they don’t have control over “nerd culture” anymore, and who have in many ways acted as shock troops to dissuade people from asking too many questions about the industry’s inner practices. In retrospect, there was an opportunity with Gamergate for those in and around the industry to really interrogate the relationship between its issues with labour and its issues with incubating angry reactionary nerds, and for the most part that didn’t happen. It couldn’t, because those who were most likely to suffer professional and personal attack weren’t organized, and still aren’t. It’s no wonder so many YouTube celebrities turn out to be fascists. Actually embracing those who work in or around these fields and who are desperately trying to inject a little grace and intelligence into the medium may help weaken that stranglehold. Not such a terrible idea considering how many kids are watching the likes of PewDiePie and JonTron.

https://twitter.com/liberalism_txt/status/894978105021956096

We’ve seen this work to an extent: bots that tweet out liberal self-owns and dank communist memes can help bring together people who feel their concerns aren’t otherwise being articulated and addressed, and find if nothing else in this a bond with other like-minded souls. I don’t think these things are necessarily directly persuasive, but they do allow us to give voice to that which both invigorates us and that which causes us to despair.

https://twitter.com/ra/status/828686383623593985

Tim Mulkerin (2017) Nazi-punching videogames are flooding the internet, thanks to Richard Spencer

They’re also a natural consequence of a diverse mass of people all feeling the same disillusionment and disgust in their everyday lives, needing solidarity but also craving catharsis. Taking a second look at these commodities we mindlessly consume may not in itself be movement building, but it can help put things in perspective. (And if these things are in your estimation not meaningful, why waste time getting angry at the people who do find value in them, especially if those people are your comrades in every way that does matter? Don’t we value a diversity of skills and tactics?)

We know this can work with podcasts, publications, flyers, banners, zines, comics, and music, despite the problems endemic to all creative industries. Not only can these things let people know that in fact they aren’t alone, but they also give us an opportunity to craft a compelling alternative vision. Unfortunate though it is that the most visible videogames tend to express the vilest characteristics of the industry, certain indie critical darling games have proven that the same tools can be used to vividly illustrate the daily grind of making ends meet while working a minimum wage job, the dehumanizing procedure of immigration bureaucracy, or the desperate, soul-crushing banality of office work.

Games of labour and the avant-garde

Richard Hofmeier Cart Life

Lucas Pope Papers, Please

Molleindustria Everyday The Same Dream

The Tiniest Shark Redshirt

Jake Clover Nuign Spectre

micha cárdenas Redshift and Portalmetal

Paloma Dawkins, Gardenarium

Colestia Crisis Theory

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Even more avant-garde works like Nuign Spectre or Redshift and Portalmetal use mixed media aesthetics to illustrate the grotesqueness of prevailing ideologies and conditions, while the dreamy work of an artist like Paloma Dawkins allows us to envision worlds which are seemingly impossible but nonetheless worthy of imagining. Colestia’s Crisis Theory subverts the tech world’s own obsession with Taylorism and systems, specifically using flow chart representation of capitalism to lay bare its inherent instability.

This isn’t to repeat the canard about games being more inherently capable of producing empathy than other art forms, or that we ought to focus on one art form to the exclusion of others. But I do think the exercise of ranking different art forms according to how sophisticated they are is inherently reactionary, arbitrarily limits the scope of expression, and constrains our ability to cultivate the new and different when it’s staring us right in the face.

As film critic Shannon Strucci pointed out in her video “why you should care about VIDEO GAMES”–which was made in response to the very attitude I’m describing–no conservative holdout in the history of the arts has ever been vindicated by a wholesale dismissal of a new form or movement as delinquent and therefore not worth engagement.

All efforts to render politics aesthetic culminate in one thing: war. War and war only can set a goal for mass movements on the largest scale while respecting the traditional property system.

Walter Benjamin (1936) The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction

But this is just regular old art criticism. Not all art is or should be explicitly used toward political ends, and games are no different. Walter Benjamin famously warned about confounding aesthetic with politics, and how doing so creates space for fascism. Grossman’s piece mentioned above ultimately links the dopey neoliberalism of Brooklyn Nine-Nine to an underlying apologia for a racist police state; this sort of prioritization of representation and aesthetics is commonplace in liberal bourgeois rhetoric (the fixation, for example, liberal pundits have with condemning bigotry as being a “bad look” rather than being actively harmful in calculable ways). The tech world, too, is remarkably consumed with style over substance–it’s a world where rainbow capitalism and tokenism reign supreme while the oligarchs who run it not only would be too happy to work on behalf of fascist governments, but have in the past and are in the present.

make this into a footer link

rainbow capitalism

tokenism

“IBM ‘dealt directly with Holocaust organisers'”, The Guardian

“Peter Thiel, Trump’s tech pal, explains himself”, The New York Times

In Ways of Seeing, art critic John Berger tracks the history of the reification of dominant ideologies through art, from colonialism to sexism to capitalism. Berger describes the nostalgic yearning for more “legitimate” forms of art displaced by newer technology as fundamentally reactionary and regressive, writing:

“The bogus religiosity which now surrounds original works of art, and which is ultimately dependent upon their market value, has become the substitute for what paintings lost when the camera made them reproducible. Its function is nostalgic. It is the final empty claim for the continuing values of an oligarchic, undemocratic culture.”

How to use games politically

Suffice it to say, there is little in the history of games or the arts generally that should stop them from expressing reactionary tendencies. It can’t really be helped, after all, if art is to be a reflection of current and historical conditions. By extension, the most regressive elements of gaming culture tend to value only those games that functionally and aesthetically resemble classic games, and classical forms of art. If games are a reflection of an industry full of people who literally want to suck the blood of the young and think unions are a trick of the devil, that’s at least in part true because art forms that preceded them, like oil painting, are a reflection of an inbred aristocracy that believed in the divine right of the propertied classes to rule and thought that they were justified in pillaging entire peoples because of their superior skull shape. That doesn’t mean we ought to deny subversive art where it exists, and it’s a piss poor reason for refusing to support its cultivation in new forms which are as-yet barely understood.

I want socialist, feminist, anti-racist, anti-fascist art to exist anywhere art is being produced, even if it’s with computers, and especially if its core demographic is young people and kids.

Supporting bold, avant-garde and subversive art is a much bigger social project than simply using what exists toward political ends, but I think if we are going to use what exists for political ends it’s useful to think about how what we create can reconfirm our reality. It’s also worth pointing out that plenty of political art is embarrassing, ineffectual or just plain preachy. The same has been true for lots of “serious” games (maybe even some of the ones I listed above), which may be accused of being boring, simplistic, or worse at conveying their overall point than a book or article on the same subject. (I would counter that games should not try to be like articles or books, but more like paintings, where being simple and straightforward isn’t such a big deal. I would also caution that it’s possible to engage serious subject matter while maintaining a sense of humour.) Conversely, when political operatives try to make use of games–rather than game developers trying to portray current events–this also runs the risk of coming off as condescending, tin-eared and trite. For example, the Clinton campaign made use of a “game-style app” called Hillary 2016 that Teen Vogue described as like “FarmVille but for politics”.

https://twitter.com/emily_uhlmann/status/757570149490761728

But I don’t think this is a bad way to approach politics because they used a game–it’s a bad way to approach politics because it avoids addressing constituents and answering simple policy questions. It betrayed a valuing of data over people that so many find bloodlessly reptilian about tech evangelism. Also, Christ does it sound boring.

A politically meaningful use of interactive art could mean the creation of workshops for marginalized communities, similar to the Skins Workshop for indigenous kids run by AbTec, a research network based in Montreal. Or, it could mean the kind of partnerships like the one Subaltern Games had with Jacobin to promote their game No Pineapple Left Behind, thereby using games as yet another way to engage people about issues like colonialism and capitalism in the global south. I’ve personally recently become involved with the Montreal collective behind Game Curious, an independent annual gaming showcase and workshop that seeks to bridge the gap between the medium, non-gamers, and radical activist groups organizing around real-world political struggles.

Initiative for Indigenous Futures | Workshops: Bringing Aboriginal Storytelling to Experimental Digital Media The Skins workshops aim to empower Native youth to be more than just consumers of new technologies by showing them how to be producers of new technologies.

Subaltern Games | Jacobin sponsorship “We are proud to announce that we will be collaborating with Jacobin Magazine to help promote our upcoming game, No Pineapple Left Behind. […] Jacobin will tell all of the leftists about our upcoming Kickstarter campaign (even YOU). They are also providing copies of their book Class Action: An Activist Teacher’s Handbook as backer rewards.”

Game Curious | Are you game curious? “Game Curious Montréal is a free, 6-week long program all about games, for people who don’t necessarily identify as “gamers.” Sessions are two hours long and will provide an introduction to a wide variety of games, as well as open discussions and group activities, in a zero-pressure, beginner-friendly environment.”

Likewise, mainstream gaming symbolism can be subverted toward leftist messaging–the appropriation of famous imagery or characters for “bootleg” leftist art could be a means for engaging youth culture and kids. Even having something like a YouTube channel or Twitch stream to engage young people on their interests from a left perspective could help shape healthier, more progressive perspectives. And, although the use of incubators and game jams are not inherently radical, and in many ways benefit the industry by training new exploitable workforces, there’s still no reason we can’t sometimes use some version of them for social and teaching events in the future.

[bctt tweet=”Why should we use games to engage and give voice to people, when other art forms exist?” username=”meminsf”]

There remains the question of why we should use games when we can use any other art form–and especially literature–to engage people on ideas and give exploited or marginalized communities more tools for making themselves heard. My answer may not be satisfying, but it’s this: why not?

I want to use all of these tools and more. I want to use whatever’s available to me and whatever works. I want to go wherever there’s movement and culture, and especially where there’s a mass of alienated, unorganized young people looking for an alternative. I see no reason to leave that on the table, or to throw fledgling modes of expression to people who post videos of themselves drinking a gallon of milk to prove their manhood and long for the Fatherland to cleanse itself in the blood of the degenerate races, or the corporations that love them.

Of course it means more to me because it’s my regrettable industry and subculture, and I don’t blame anyone if they read this and still can’t find it in themselves to give a shit. Still, these cultural properties aren’t going away, so we might as well engage with them. More than that, we can make good on the promise of so many oleaginous tech disruptors that Gaming is revolutionary in how it makes possible different and exciting new worlds. Isn’t a new world what we want?

References

ResistJam brings game devs together against authoritarianism

Your app isn’t helping the people of Saudi Arabia

George Monbiot on neoliberalism (a fantastic article that both introduces neoliberalism to those unsure what the word means, and gives those who have been using the word for years an enriched perspective)

Eleanor Robertson (2016) Get Mad and Get Even, Meanjin Quarterly

Jonathan Ore (2017) “Viewer discretion advised? Your child’s favourite YouTuber may be posting offensive content”, CBC News

Laura Stampler (2016) “Hillary Clinton campaign launches ‘Hillary 2016) game app”, Teen Vogue

The Gamer Trump Trope

Patrick Klepek (2017) “The power of video games in the age of Trump”, Vice

Christopher J. Ferguson (2017) “How will video games fare in the age of Trump?”, Huffington Post

Asi Burak (2017) “Trump as Gamer-in-Chief”, Polygon

Back to text

Labour issue examples

Children as young as seven mining cobalt used in smartphones, The Guardian

Chinese university students forced to manufacture PS4 in Foxconn plant, Forbes

Back to text

Otto von Bismarck, Wikiquote

Prince Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, Duke of Lauenburg (1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), was a German aristocrat and statesman; he was Prime Minister of Prussia (1862–1890), and the first Chancellor of Germany (1871–1890).

Die Politik ist die Lehre vom Möglichen. Politics is the art of the possible.

Interview (11 August 1867) with Friedrich Meyer von Waldeck of the St. Petersburgische Zeitung: Aus den Erinnerungen eines russischen Publicisten. 2. Ein Stündchen beim Kanzler des norddeutschen Bundes. In: Die Gartenlaube (1876) p. 858 de.wikisource. Back to text

Politically meaningful games under neoliberalism Since Donald Trump won the US presidential election one year ago, the games sector has tried to work out how to use our medium to resist the rise of the far right.

1 note

·

View note

Link

By Maria Hill

I see a lot of depression around me.

Perhaps you do, too.

But it is a strange kind of depression, the kind of depression that comes when everything around us seems wrong.

Depression and Culture

What I am seeing is a fairly complex depression that comes from a number of sources – like an octopus messing with our inner well-being. I am calling it cultural depression.