#art & literature for dissidents

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Палімпсести. Неначе стріли, випущені в безліт…

Неначе стріли випущені в безліт,

згубилися між обидвох країв,

проваджені не силою тятив,

а спогадом про образи почезлі -

летять понад землею долілиць

пірнають ввись і засягають паді,

і лячно задивляються в свічаддя

людських озер, колодязів, криниць.

Так душі наші: майже неживі

пустилися в осінні перелети,

коли відчули - найдорожчі мети

на нашій окошились голові.

В дорозі довгих самопроминань

під знадою земного притягання

проносяться від ранку до смеркання

сподіючись на всепрощенну длань.

Обабіч - чужаниця - чужина.

Під кожним крилом - чужа чужина.

І даленіє дальня Україна -

тяжка як жито і як синь ясна.

Дивлюсь - і мало очі не пірву:

невже тобі ні племені, ні роду?

За сині за моря лети по воду

однаково - чи мертву чи живу.

Василь Стус

#мистецтво#українська література#ukraine#література#poetry#поезія#ukrainian poetry#art#dissidents#literature#ukrainian history#ukrainian tumblr#ukrainian culture#культура#український tumblr#українська мова

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm thinking about how when certain nation-states commit terrible acts, some circles in the West jumps on them and their entire populations and their entire existences in a way they wouldn't for other nation-states and those nation-states are often the ones with populations that have been heavily stigmatized and racially or culturally othered as less than or untrustworthy.

I see this in reaction to for example, Israel*, Iran*, and China* (famously countries that are majority Jewish, Muslim, and, well, Chinese) and how quickly rightful cries against their governments' violent policies against minorities and/or dissidents turn into rehashing of old prejudices until it's no longer clear if people are protesting against the governments or against the people itself or even against entire cultures.

It leads deep disgust for Israelis and Jews, Iranians, and Chinese people in diaspora who may still feel and vocalize a deep love and connection for their homeland because countries and lands are more than government and military actions.

(I'm thinking of people demanding Jews disavow any ties with ~the Zionist Entity~, including being told not to speak Hebrew or be legitimate targets of harassment, of Iranians (often conflated with Arabs and vice versa) assumed to be violent and dangerous to the point where I know Iranians who have chosen to be called Persian only to escape the stigma, of the demand to completely turn away from Chinese media and literature and business and innovation lest it be the government in disguise. Of people being told their cultures are illegitimate propaganda rather than the accumulation of thousands of years of scholarship and art.)

All of this also, of course, leads to hate crimes domestically against people connected to or perceived to be connected to those countries.

Prejudice, racism, anti-Semitism, and Islamophobia are insidious and they will find their way into how we respond terrible injustices and crises in the world. I don't know how to stop that from happening, but at the very least, we should be sensitive and watchful for it.

*These are three example countries that are and have been in the news a lot recently but this could apply to many, many more.

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Painting in Darkness’, a documentary about Lulzim Beqiri, a painter imprisoned during Communist rule because his art didn’t conform with the ruling party’s ideology, was given its first screening on Thursday in Tirana.

“I feel… very happy, I don’t even know if I deserve this,” Beqiri, now 73, told BIRN.

The film, directed by Elton Baxhaku and produced by BIRN Albania and Barraca Productions, was shown as part of Memory Days, an annual series of events in Albania focusing on the experiences of former Communist countries in dealing with the past.

Beqiri was arrested in February 1977 for “agitation and propaganda” and his paintings were used against him in the trial, representing his opposition to the Communist regime.

Beqiri’s artworks, around 40 canvases that he painted in 1976, were seized by the authorities.

“They didn’t only confiscate these paintings, but literature, translations, various notes, etc,” he said.

Forty-six years later, he was able to get two of his pieces back again, thanks to an archive worker, Astrit Jegeni, who had saved them from an archive.

Asked about how he felt when he finally got the paintings back, so many years later, he responded: “In the beginning, I couldn’t understand when and how I had painted them. Later, while I was reading my files, I could understand why.”

After the two paintings were returned to him, Beqiri was able to hold his first exhibition, which also includes paintings he did while in prison.

Blerina Gjoka, the journalist who wrote the documentary’s script, said the paintings were returned to Beqiri after she got to know the archivist, Jegeni, who told her about the artworks he had at his home.

“Since 1992, [Jegeni] had been trying to find the creator to give the paintings back to him. He knew his name, but couldn’t find him,” said Gjoka.

“Then I found the painter, I found his phone number and made possible for them to meet. We recorded their first meeting on camera and the most beautiful thing is that they have established a friendship between them. Lulzim Beqiri, who wasn’t painting for a long time, has started to paint again,” she added.

Under the dictatorial Communist regime of Enver Hoxha in Albania from 1944-1991, more than 30,000 Albanians were imprisoned for political reasons. Around 50,000 others were interned or expelled from their homes.

Art and culture under Communism was strongly connected to political ideology and every artwork was closely examined by the authorities. The consequences of flouting the ideological rules were imprisonment, internment in labour camps, persecution and in some cases death.

The work of the artists who were imprisoned was confiscated. The Albanian state does not have any inventory or study of the number of works of art that were lost as a result.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Slogans, jokes, objects and colors can stand in for complex sentiments. In Hong Kong, protesters carried yellow umbrellas—also useful to defend against pepper spray—as symbols of their demand for democracy. In Thailand, protesters borrowed a gesture from The Hunger Games series, saluting with three fingers aloft in the aftermath of a military coup. Elsewhere, rainbow flags and the name “Solidarity” have signified the successful fights waged by proponents of LGBTQ and Polish labor rights, respectively.

In some authoritarian nations, dissidents craft jokes and images to build a following and weaken support for the regime. In the Cold War-era Soviet Union, access to typewriters and photocopiers was tightly controlled. But protesters could share news and rile officials with underground samizdat literature (Russian for “self-publishing”), which was hand-typed and passed around from person to person. These publications also used anekdoty, or quips of wry lament, to joke about post-Stalinist Soviet society. In one example, a man hands out blank leaflets on a pedestrian street. When someone returns to question their meaning, the man says, “What’s there to write? It’s all perfectly clear anyway.”

In the early 20th century, generations of Chinese writers and philosophers led quiet philosophical and cultural revolutions within their country. Zhou Shuren, better known by the pen name Lu Xun, pushed citizens to cast off repressive traditions and join the modern world, writing, “I have always felt hemmed in on all sides by the Great Wall; that wall of ancient bricks which is constantly being reinforced. The old and the new conspire to confine us all. When will we stop adding new bricks to the wall?”

In time, Chinese citizens mastered the art of distributed displeasure against mass censorship and government control. That was certainly the case during the movements that bloomed after Mao Zedong’s death in 1976. At the 1989 protests in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, participants used strips of red cloth as blindfolds. Before the tanks turned the weekslong gathering into a tragedy on June 4, musician Cui Jian played the anthem “A Piece of Red Cloth,” claiming a patriotic symbol of communist rule as a banner of hope for a frustrated generation.

After hundreds, if not thousands, were gunned down by the military, China banned any reference to the events at Tiananmen Square. But Chinese people became adept at filling that void, using proxies and surrogates to refer to the tragedy. Though Chinese censors scrub terms related to the date, such as “six four,” emoji can sometimes circumvent these measures. According to Meng Wu, a specialist in modern Chinese literature at the University of British Columbia, a simple candle emoji posted on the anniversary tells readers that the author is observing the tragedy, even if they can’t do so explicitly. In recent years, the government has removed access to the candle emoji before the anniversary.

As a survivor of the Tiananmen Square massacre spoke to the crowd gathered at Washington Square Park, the undergraduate who called himself Rick expressed concern for a friend who had been taken into custody by police in his home province of Guangdong. Given the government crackdown, Rick suggested that public protests were largely finished for now. Still, he predicted, the movement will “become something else”—something yet to be written.

— The History Behind China's White Paper Protests

#suzanne sataline#the history beyond china's white paper protests#history#current events#totalitarianism#oppression#politics#chinese politics#censorship#journalism#free speech#protests#silent protests#zero covid protests#2019-2020 hong kong protests#2020-2021 thai protests#cold war#1976 tiananmen incident#1989 tiananmen square protests and massacre#china#hong kong#thailand#ussr#lu xun#samizdat

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

WIP Wednesday November 29 2023

You had always intended to visit the Many-steps monastery. Built from the basement of Hocum's museum after it closed, it served as a treasure trove of pre-Thrune art, literature, and history. Its existence was not commonly known in the church of Irori, but Giliys had caught wind of it through contacts with the Bellflower Network, so he passed the information onto you. That is how you came in contact with the Sacred Order of Archivists–the order of Irorian scholars dedicated to preserving Chelish history and culture–a connection that proved fruitful through the years until they suddenly went silent. The only explanation you received was that their sudden silence coincided with "The Night of Ashes" and the late Barzillai Thrune's crackdown on Kintargan dissidents.

If you look closely, you can still see evidence of Thrune's raid: scorch marks on walls, occasional burgundy stains on the floor. For the most part, though, the place seems ready for scholars to return–and based on the Message you received not long after your arrival, they already have. Or, rather, one has.

You find Corvinius Basad in one of the scholar's cells, standing over an open book laid out on the desk in front of him. He holds his hand, glowing pale blue with divine power, over a book, opened to a section where pages have been torn out. He is older than you remember from your days as novices–the long braid looped around his neck, typical of the Irorian priesthood, is streaked with gray, and his face is now lined from age–but that is to be expected. That was a quarter of a century ago, and humans age so much faster than gnomes.

"Just a moment," Corvinius says, not looking up from the mutilated text before him. Before you can reply, the tattered remains of one of the torn out pages begins to shift and then grow. You stare in awe as the book seems to heal before your very eyes, and a single page, ink and all, is restored.

"How did you do that?" You blurt out as Corvinius straightens and wipes a bead of sweat from his brow. He grins.

"Wonderful, isn't it? A little trick from a friend. She uses it for somewhat less altruistic purposes, which is likely why it can only be used to restore a single page at a time." He grimaces. "It's slow going, but the alternative is to allow what the Asmodeans destroyed to be lost forever. In any case, it is good to see you again, Sister." He bows his head slightly in greeting, and you return the gesture with some embarrassment.

"And you as well, Brother. Forgive my rudeness–I did not expect to see a miracle performed today."

Corvinius snorts. "I heal books one page at a time, sister. You heal people with a single spell. Which of us is the miracle worker?"

You nod politely, trying to keep the flare of guilt from your face. You wouldn't be here if you were a miracle worker.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good question! Given the nation-summing implications of Great American Novel, Nightwood—but not Gravity's Rainbow—is an odd choice. Yet it seems to me to be a particularly urgent book right now. As the era of left-identitarian moralism gives way to renewed varieties of right-wing culture, whether revolutionary reaction at the avant-garde fringe or Christian populism in mainstream electoral politics, the political complexity of Nightwood—a lesbian and transgender novel also plausibly described as a fascist one—deserves our attention for conceptual reasons alone. In my almost eight-year-old essay on Nightwood, I tried to sum up its extraordinary complications:

A modernist anti-democrat, like her champion Eliot, Barnes sees the masses as perennial forces of conformity, enemies of art. This is not really surprising; what is surprising is that anybody ever wanted to identify bohemia—sexual and aesthetic—with the political left in the first place. The intention of its various partisans notwithstanding, the left has historically empowered the state and its centripetal agencies. The state, tolerating nothing outside itself, not only threatens to use the masses as justification for the cleansing of bohemia’s cruising-ground pissoirs and carnivalesque circuses, but, as I said above, it also extirpates the tradition against which bohemia necessarily defines itself. It razes the edifice of Christianity, brings the wandering Jew home, and abolishes the night in which Robin Vote and Dr. Matthew O’Connor sport like fauna in the forest. Even internally, bohemia is not democratic: it is, rather, an aristocracy of spirit. For these reasons, Nightwood is among the most reactionary of American classics, despite or even—what will confound the identity politics of today—because of its having nary a straight white male in its cast of characters.

Perhaps now that the American literati, chastened of its moralism, is undergoing a strange fit of Ernst-Jünger-mania—I essayed on The Glass Bees around the same time I wrote on Nightwood; I'll write about On the Marble Cliffs if someone gets it for me from my wish list—they will be prepared to hear out this side of our own homegrown conservative revolutionary, Djuna Barnes.

Your question also gives me a sensory memory, reminding me that literature is not primarily conceptual: the first pandemic summer, when stores and cafés and libraries were still closed, and I would walk around the city for hours and for miles, dripping with sweat—they always tell you how cold Minneapolis gets in the winter but never how hot in the summer—listening to any podcast I could find. My recollection is that Judge said on his show, whatever he would Tweet later, that those were the three greatest works of American prose, which isn't quite the same thing as greatest American novels. Nightwood's prose, the vision it discloses, is incomparable, something like late James in a fever dream:

Like a painting by the douanier Rousseau, she seemed to lie in a jungle trapped in a drawing room (in the apprehension of which the walls have made their escape), thrown in among the carnivorous flowers as their ration; the set, the property of an unseen dompteur, half lord, half promoter, over which one expects to hear the strains of an orchestra of wood-winds render a serenade which will popularize the wilderness.

I first read Nightwood for my oral exams in grad school; when I conferred with my advisor after reading it, her only comment on the novel was, and I quote, "It's a hoot!" I second that.

The virtues of Gravity's Rainbow qua Great American Novel are more obvious. I explored them here:

Gravity’s Rainbow, set in Europe, is a Great American Novel because it criticizes America (or, in the orthography of the period, AmeriKKKa) in the name of universal emancipation. [...] Slothrop, “Providence’s little pal,” descends from the Puritans—his ancestor, William, came over on the Arbella, the ship bearing John Winthrop, though William, a dissident among the elite, stood up for the preterite (the novel’s system of allusions doubling Slothrop with JFK suggests a more historically proximate example of a dissident elite done in by Them). Yet what could be more faithful to Puritanism, to John Winthrop himself, than such a jeremiad? Only a disappointed lover could turn into such a castigating prophet: why rail so furiously against the New World unless you really were expecting a City on a Hill?

Much as Pynchon's brand of stoner comedy sometimes grates on me, much as I find that book harder to read than is strictly necessary even for its radical political purpose, our reclusive author seems to me to have earned the title.

Personally, I wouldn't exclude either book, I would just make a longer list: The Scarlet Letter, The Portrait of a Lady, My Ántonia, Light in August, The Adventures of Augie March, Invisible Man, Song of Solomon, Blood Meridian, Underworld, etc.—each of us can add or subtract.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oleg Orlov, a leading human-rights activist, at the Human Rights Center Memorial in Moscow, Russia, on May 17, 2023.

‘We Are Being Punished for Daring to Criticize the Authority’

‘We Are Being Punished for Daring to Criticize the Authority’ (msn.com)

Opinion by Anne Applebaum

"On February 27, Orlov received a two-and-a-half-year prison sentence for “discrediting the Russian army.” Following in a long tradition of Soviet dissidents before him, Orlov made a courtroom speech, addressed to those in the room and beyond. Joseph Brodsky, who later won the Nobel Prize in Literature, sparred in 1964 with a Soviet judge who asked him by what right he dared state “poet” as his occupation: Who ranked you among poets?” Brodsky replied, “No one. Who ranked me as a member of the human race?” That exchange circulated throughout the Soviet Union in handwritten and retyped versions, teaching an earlier generation about bravery and civic courage.

Orlov’s speech will also be reprinted and reread, and someday it will have the same impact too. Here are excerpts, translated by one of his colleagues:

On the first day of my trial, terrible news shocked Russia and the entire world: Alexey Navalny was dead. I, too, was in shock. At first, I even wanted to give up on making a final statement. Who cares about words today, when we have not recovered from the shock of this news? But then I thought: These are all links in the same chain. Alexey’s death or, rather, murder; the trials of other critics of the regime including myself; the suffocation of freedom in the country; the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian army. So I have decided to speak. I have not committed any crime. I am being tried for writing a newspaper article that described the political regime in Russia as totalitarian and fascist. I wrote this article over a year ago. Some of my acquaintances thought back then that I had exaggerated the gravity of the situation. Now, however, it is clear that I did not exaggerate. The government in our country not only controls all public, political, and economic life, but also aspires to exert control over culture and scientific thought … There isn’t a sphere of art where free artistic expression is possible, there are no free academic humanitarian sciences, and there is no more private life either.

[Read: How I lost the Russia that never was]

Orlov continued by reflecting on the absurdity of his case, of the legalistic rigamarole in Russia that conceals the regime’s lawlessness. In fact, the law is whatever Putin dictates. Everything else, the lawyers, prosecutors, and judges, are just there for show, to pretend that there is rule of law when there is not."

READ MORE ‘We Are Being Punished for Daring to Criticize the Authority’ (msn.com)

0 notes

Text

BLOG-3

Politics in Art: A Personal Exploration

Art has for a long time intrigued me as an art lover. Over the years, different artists have resorted to their creative abilities to voice their political views, defy traditions, and cause a revolution in society. This blog post examines the intricate dynamics that exist between art and politics employing relevant literature and illustrations.

The Role of Political Art

The relationship between art, especially in the Western world, and its social environment was always essential. It had always involved mirroring the society as well as its political circumstances. Art is used politically, providing important messages concerning human rights, societal justice, and government violence. Engaging in political art makes it possible for us to understand more about how the society operates or the forces operating behind our existence.

one of the best known pieces of political art is Picasso’s Guernica (1937) that represents the terrors of the Spanish Civil War an extremely good anti-war statement. Another striking instance is Banksy who is an anonymous graffiti artist associated with controversial politically laden pieces on issues like capitalism, consumerism and squalor.

The Aesthetic Regime and Art's Political Engagement

The essence to politics in art relies on aesthetics of art. The aesthetics regime has since been proposed by the French philosopher Jacques Rancière who distinguishes art from the ethical and poetic regimes, the latter two defining art beforehand. The aesthetic regime insists on art’s capacity to unsettle and remake concepts of self-hood, world-hood, and thus is an immensely political weapon

Comparing Political Artworks

To further illustrate the relationship between art and politics, I will compare two political artworks: The portraiture work of Frida Kahlo “self-portrait on the borderline of Mexico and United states” of 1932 and that of Ai Weiwei called Trace (2014).

In her painting Kahlo addresses subjects of industrialism, colonialism and capitalism as seen in an image of the artist on the border between Mexico and the US. It is a critique on the cultural and political conflicts arising between the countries with the artist also revealing his own sense of alienation.

However, Ai Weiwei’s “TRACE” is a wall installation made from Lego bricks featuring various portraits of global activists and political dissidents. Censorship and societal fragmentation come into focus at the center in this piece of art, provoking the viewer to think about the necessity of freedom of speech and unity today.

The two pieces of arts clearly attest to the ability of art to confront political concerns, promote thoughtful contemplation, and generate conversations.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States, 1932.

Ai Weiwei, Trace, 2014

Personal Reflection and Conclusion

Politics in art has helped me understand the influence of art on how one relates and defines the world around oneself. Political art thus offers us an opportunity of questioning our own belief assumptions thus creating a more open society.

In addition, I learnt on how to support arguments in my assignments with academic sources and examples, and how to cite them in a Harvard referencing style. It has helped in reinforcing my arguments and provided an opportunity for dialogue on art and politics within the academic world.

Therefore, the connection between arts and politics is complicated and multi-sided, for art can reflect or inspire change in politics. The fact that artists have the power to subvert social norms and advocate for fairness excites me as a supporter of the arts, and I eagerly anticipate pursuing this intriguing area further.

References

Maria R. (2016). 15 Influential Political Art Pieces | Widewalls. [online] Widewalls. Available at: https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/political-art [Accessed 21 Dec. 2023].

Contributor, A. (2023). Art is Political: Nine Artists Who Used Their Art for Their Politics. [online] Academy of Art University. Available at: https://www.academyart.edu/about-us/news/art-is-political-nine-artists-who-used-their-art-for-their-politics/ [Accessed 17 Dec. 2023].

Anapur, E. (2016). The Strong Relation Between Art and Politics | Widewalls. [online] www.widewalls.ch. Available at: https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/art-and-politics [Accessed 21 Dec. 2023].

0 notes

Text

Boris Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago: A Dissident Masterpiece or Propaganda Tool?

Outline of the Article:

I. Introduction A. Brief background on Boris Pasternak B. Overview of Doctor Zhivago controversy II. Boris Pasternak Boooks III. Early Life and Influences A. Pasternak's formative years B. Influences shaping his literary vision IV. Literary Innovations A. Doctor Zhivago's experimental style B. Complexity in language and structure IV. Notable Works A. Exploration of Doctor Zhivago, key themes B. Other significant works by Pasternak VI. Nobel Prize Nomination A. Pasternak's Nobel Prize nomination B. Consequences of the nomination VII. Political Landscape A. Soviet censorship during the Russian Revolution B. How political context influenced Doctor Zhivago IX. Controversial Article Angle A. Dissident masterpiece perspective B. Propaganda tool allegations X. Reception and Criticism A. Public and critical responses to Doctor Zhivago B. Varied opinions on Pasternak's intentions

XI. Impact on Literature

A. Doctor Zhivago's enduring influence B. Pasternak's contribution to Russian literature

XII. Burstiness and Perplexity in Storytelling

A. Maintaining intrigue through burstiness B. Handling perplexity for a dynamic narrative

XIII. Symbolism in Doctor Zhivago

A. Analyzing symbolic elements in the novel B. Implications of symbolism on the narrative

XIV. Conclusion

A. Summarizing perspectives on Doctor Zhivago B. Emphasizing the ongoing debate

XV. FAQs

A. Addressing common questions and misconceptions

I. Introduction

A. Boris Pasternak, a renowned Russian poet and novelist, left an indelible mark on literature. Born in 1890, his life unfolded against the backdrop of Russia's tumultuous history, influencing his literary endeavors. B. The controversy surrounding Pasternak's masterpiece, Doctor Zhivago, adds layers to his legacy. The novel, exploring love and life during the Russian Revolution, faced both acclaim and condemnation, making it a focal point of literary discourse.

II. Boris Pasternak Boooks

- "Doctor Zhivago" (1957) - Undoubtedly, Pasternak's most celebrated work, "Doctor Zhivago" is a sweeping epic set against the backdrop of the Russian Revolution. It explores the complexities of love, politics, and the human spirit. - "My Sister, Life" (1922) - This collection of poetry is considered a masterpiece of Russian Symbolism. Pasternak's verses showcase his early experimentation with language and his deep reflections on life and art. - "The Last Summer" (1934) - A semi-autobiographical novel, "The Last Summer" delves into the themes of love and creativity. It provides a nuanced glimpse into Pasternak's own experiences and struggles. - "Safe Conduct" (1931) - This collection of essays and reflections offers insights into Pasternak's thoughts on literature, art, and the tumultuous political landscape of his time. It's a valuable exploration of his intellectual depth. - "Selected Writings" (1978) - A posthumous compilation, this volume brings together a variety of Pasternak's works, including poems, essays, and translations. It serves as a comprehensive introduction to the breadth of his literary contributions.

III. Early Life and Influences

A. Boris Pasternak's formative years profoundly shaped his artistic sensibilities. Growing up in a household steeped in the arts and intellectual pursuits, he developed a keen awareness of the complexities inherent in human existence. B. Pasternak's unique literary vision was molded by a diverse range of influences, spanning from the rich tapestry of Russian Symbolism to the nuanced narratives of European literature. His early encounters with revolutionary ideals and profound reflections on the human condition became the foundational pillars of his later literary works.

IV. Literary Innovations

A. Doctor Zhivago stands as a testament to Pasternak's commitment to an experimental style. The novel's narrative structure, a seamless blend of poetry and prose, boldly challenged conventional norms, delivering a reading experience that remains distinctive and memorable. B. The intricate interplay of language and structure within Doctor Zhivago exemplifies Pasternak's unwavering dedication to pushing the boundaries of literary expression. His innovative approach not only defied convention but also invited readers to engage with the narrative on multiple intellectual and emotional levels.

V. Notable Works

A. While Doctor Zhivago holds a central place in Pasternak's literary achievements, exploring key themes within the novel reveals the profound depth of his storytelling prowess. B. Pasternak's literary repertoire extends well beyond Doctor Zhivago, encompassing significant works such as My Sister, Life, and The Last Summer. Each piece contributes to a nuanced understanding of the thematic preoccupations that defined his literary career.

VI. Nobel Prize Nomination

A. The 1958 Nobel Prize nomination brought both acclaim and controversy to Pasternak. Despite recognition by the Nobel Committee, the Soviet authorities' severe backlash underscored the political tensions surrounding his work. B. The far-reaching consequences of the Nobel Prize nomination had a profound impact on Pasternak's personal and professional life, emphasizing the intricate interplay between literature and politics during that period.

VII. Political Landscape

A. The pervasive Soviet censorship during the Russian Revolution cast a shadow over artistic expression. Pasternak's navigations through this politically charged landscape provide profound insights into the challenges faced by intellectuals in an era marked by ideological constraints. B. Unraveling the genesis of Doctor Zhivago within the broader political context sheds light on how Pasternak's portrayal of revolutionary events was both shaped and constrained by the prevailing Soviet ideology.

VIII. Controversial Article Angle

A. Viewing Doctor Zhivago as a dissident masterpiece aligns with Pasternak's intent to present an alternative narrative to the prevailing political ideology, challenging established norms. B. Allegations of the novel being a propaganda tool suggest a calculated intent, implying that Pasternak's work may have been strategically crafted to serve political ends, adding a layer of complexity to the ongoing discourse.

IX. Reception and Criticism

A. Public and critical responses to Doctor Zhivago have been diverse, reflecting the polarizing nature of the novel. While some hailed it as a masterpiece, others condemned it as subversive, contributing to the ongoing debate about Pasternak's intentions. B. Varied opinions on Pasternak's motivations add depth to the discourse, emphasizing the novel's dual role as a work of art and a political statement.

X. Impact on Literature

A. Doctor Zhivago's enduring influence extends beyond its initial publication. Pasternak's contribution to Russian literature is recognized as a distinctive voice that resisted conforming to ideological constraints. B. Examining how Pasternak's works influenced subsequent generations of writers illustrates the lasting impact of his literary legacy, transcending the confines of time and political ideology.

XII. Burstiness and Perplexity in Storytelling

A. Maintaining intrigue through burstiness ensures that Doctor Zhivago captivates readers. Pasternak strategically employs bursts of emotion and pivotal events, keeping the narrative dynamic and engaging. B. Handling perplexity, characterized by complexity and ambiguity, adds depth to the storytelling, encouraging readers to actively engage with the novel on intellectual and emotional levels.

XIII. Symbolism in Doctor Zhivago

A. Analyzing symbolic elements in Doctor Zhivago unveils layered meanings behind objects, events, and characters. Pasternak employs symbolism to convey nuanced messages within the narrative, enriching the reader's interpretative experience. B. Understanding the implications of symbolism adds a profound layer to the reader's interpretation of Doctor Zhivago's themes and characters, enhancing the overall literary experience.

XIV. Conclusion

A. Summarizing perspectives on Doctor Zhivago requires acknowledging the multiple interpretations that exist. The ongoing debate reflects the novel's enduring ability to provoke thought and discussion, ensuring its place in the literary canon. B. Emphasizing the ongoing debate underscores the significance of Doctor Zhivago as a work that continues to captivate readers and scholars alike, maintaining its relevance and impact over time.

XV FAQs

- Why was Dr. Zhivago controversial? - The controversy surrounding Doctor Zhivago stems from its depiction of the Russian Revolution, challenging Soviet ideologies. - Is Dr. Zhivago a banned book? - At certain points in history, Doctor Zhivago faced censorship, with Soviet authorities suppressing its publication due to its perceived dissent. - What is the message of Dr. Zhivago? - Doctor Zhivago explores themes of love, life, and the human condition against the backdrop of the Russian Revolution, offering a nuanced commentary. - How accurate was Dr. Zhivago? - While Doctor Zhivago is a work of fiction, Pasternak drew inspiration from historical events, providing a perspective on the Russian Revolution. - How did Doctor Zhivago impact Boris Pasternak's legacy? - Doctor Zhivago significantly contributed to Pasternak's legacy, solidifying his reputation as a literary giant and dissident voice in Russian literature. Read the full article

#atruestory#BorisPasternaknovels#ControversialportrayalinRussianliterature#DissentinSovietliterature#DissidentthemesinDoctorZhivago#Doctorzhivagocontroversypdf#Doctorzhivagocontroversysummary#DoctorZhivagopoliticalcritique#doctorzhivagosummary#drzhivagoending#drzhivagosummarybychapter#Historicallovestoriesinliterature#isdrzhivago#Pasternak'sliteraryimpact#Pasternak'srevolutionarynarrative#RussianRevolutioninfiction#RussianRevolutionliteratureanalysis#whathappenedtodrzhivago'sfirstwife#whathappenedtotonyaandsashaindrzhivago

0 notes

Photo

War, identity, irony: how Russian aggression put central Europe back on the map | Jacques Rupnik A 1980s essay by Czech writer Milan Kundera on the peoples trapped between east and west is enjoying a new lease of life“Are you a dissident?”, a journalist asked Milan Kundera, when he had became exiled in France from his native Czechoslovakia in the mid-1970s. “No, I am a writer,” replied the author of The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Not that he was indifferent to the plight of those who were opposing the Czech regime from inside, but he was wary of a political label being attached to a novel, and more generally to literature with a message, to art in the service of a political idea.Yet Kundera, who died last month, was a man of ideas, which he explored particularly in his essays, the most influential being A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe, published in Paris in 1983 and republished in English earlier this year. Central Europe, Kundera argued, belonged “culturally to the West, politically to the East and geographically in the centre”. The predicament of the small nations between Russia and Germany was that their existence was not “self-evident” but remained closely tied to the vitality of their culture, and historically intertwined with that of the west from which they had been “kidnapped” in 1945. Continue reading... https://www.theguardian.com/world/commentisfree/2023/aug/25/war-russian-aggression-central-europe-milan-kundera-east-west

#Europe#Milan Kundera#World news#Ukraine#Russia#Vladimir Putin#Czech Republic#France#Cold war#Jacques Rupnik#The Guardian

0 notes

Text

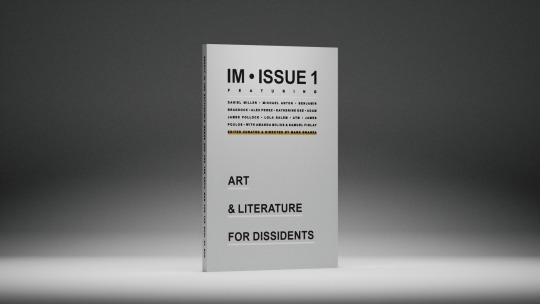

Future of Dissent

#im1776#im 1776#art & literature for dissidents#and#cyberpunk#art#conservative#neoliberal#cypher punk#future of dissent#anarchopunk#anarcho#upwing#upwinger#futurism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

LVIV, Ukraine—One of the most profound images to come from the siege of Sarajevo was the stark image of the cellist Vedran Smailovic playing Tomaso Albinoni’s Adagio in G Minor every day at noon, sitting elegantly and defiantly in black tie in the midst of the wreckage of Bosnia’s National and University Library.

The library had been bombed by Bosnian Serbs on Aug. 25, 1992, destroying 90 percent of its 1.5 million volumes of precious books, including rare Ottoman editions. A 32-year-old librarian was killed that night as she desperately tried to save books. The scene of book pages burning and ashes rising in the air was an indelible image of the cruelty of war and a symbol of cultural destruction.

The beautiful, Moorish-inspired City Hall building, called Vijecnica, which housed the library, was more than a place to find books—it was a potent symbol of multicultural ethnicity. That, above all, is what the Serbs tried to destroy: the cultural ethos of what made up Bosnia.

A similar phenomenon is happening now in Ukraine. Russia seeks to destroy Ukrainian identity, and that includes monuments, libraries, theaters, art, and literature.

In the many conflicts I have covered, art and literature are essential to morale—to civilians struggling to live moment by moment through the attempted destruction of their country, as well as to the soldiers fighting on the front lines to defend their culture and history. It is also the basis of historical memory: what is remembered, what is forever kept.

Early this month, shortly before Russia began its latest wave of terror in Ukraine—featuring missile and Iranian-made kamikaze drone attacks on civilians in Kyiv, missile strikes on civilian infrastructure in Lviv, and other assaults elsewhere in the country—I went to one of the most remarkable literary festivals I have ever attended: the three-day Lviv BookForum.

Lviv, in western Ukraine, is a glorious baroque city that over the years has been part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Poland, and the Soviet Union, as well as having been besieged by the Nazis. Throughout it all, this wondrous city has endured.

The idea to have a literary festival in the midst of a vicious war is representative of Ukrainians’ defiance. Among the many who gathered in Lviv to attend in solidarity were Ukrainian writers such as the former political prisoner Stanislav Aseyev and Diana Berg, who lost her home twice in Mariupol; the Ukrainian novelist and human rights activist Victoria Amelina; and the British barrister and author Philippe Sands, who wrote one of the most powerful books on the origins of genocide, East West Street.

Also attending were the historian Misha Glenny; the disinformation expert Peter Pomerantsev and his father, Igor Pomerantsev, a dissident Soviet poet; the French American novelist Jonathan Littell; the award-winning nonfiction writer Nataliya Gumenyuk; and two extraordinary British doctors, Henry Marsh and Rachel Clarke, who came to Ukraine to bear witness to the atrocities. There were many others: philosophers, bloggers, activists.

It was an interesting mix of cultures, but the stars of the event were by far the Ukrainian writers, who read and told stories with courage and brutal honesty. The literary scholar Oleksandr Mykhed told the audience that on Feb. 24, the day of the Russian invasion, he realized: “You could not protect your family from a rifle with your poems. You could not hit someone with a book—you could try, but it won’t work with the crazy occupiers from Moscow. I lost belief in the power of culture, lost interest in reading.”

Shortly after that realization, Mykhed enrolled in the army; a week later, he lost his family home to a bomb.

But even in Lviv—relatively peaceful until the recent attacks—the war was not far away. In between sessions, we wandered the cobblestoned streets, passing the historic Garrison Church of Sts. Peter and Paul, honoring the fallen soldiers. One night, on my way home from dinner, I saw a crowd of young people gathered around a guitar player, who was belting out the Ukrainian national anthem. It was powerfully emotional. Everyone stood with their hands on their hearts, under an enormous full moon, singing at the top of their lungs in Ukrainian: “Ukraine’s freedom has not perished, nor has her glory. … Upon us, fellow Ukrainians, fate shall smile on us once more.”

The next day, one of my fellow panelists was Amelina, the Ukrainian novelist and author of the books Fall Syndrome and Dom’s Dream Kingdom. I first met Amelina in Berlin at a conference for human rights monitors. Since the war started, she stopped writing novels and started investigating war crimes. In her backpack, she carries tourniquets—her work often takes her to front lines throughout the country.

“While Russian occupiers try to destroy the Ukrainian elite, including writers, artists, and civil society leaders, the free world needs to hear and amplify the Ukrainian voices,” she said. “Then we have a chance not only to defend Ukraine’s independence this time in history but also truly implement the ‘never again’ slogan for the continent.”

Amelina told me of a recent visit to Izyum, in eastern Ukraine, after the Ukrainian Armed Forces had liberated it. She met with the parents of Volodymyr Vakulenko, a Ukrainian children’s book author who was abducted from his house during the Russian occupation.

Volodymyr’s father mentioned to Amelina that before being abducted, his son hid his war diary under the cherry tree in the garden. Amelina helped the grieving father dig the diary up and later brought it to the Kharkiv Literary Museum.

“I chose the museum because it holds the first editions and manuscripts of my favorite writers executed by the Soviet regime in the 1930s,” she said. “I hope Volodymyr Vakulenko is still alive and his diary [doesn’t] start the collection of manuscripts of another generation of Ukrainian writers murdered by the empire.”

During one of our panels, we were joined on Zoom by a 27-year-old poet named Yaryna Chornohuz, who called in from the front line. As well as being a gifted writer, Chornohuz is a reconnaissance soldier and combatant in the 140th Reconnaissance Battalion of the Ukrainian Marine Corps.

“My position now is a combat medic of the reconnaissance combat group,” she said. “I’ve been on the front line since 2019. Now it’s my 14th month of rotation in [the] Luhansk and Donetsk region.”

She proudly told us that her unit took part in the defense of Severodonetsk, Bakhmut, and Popasna. In March, she took part in engagements in villages north of Mariupol. Now she’s participating in a counteroffensive on Lyman and Yampil.

Listening to her, I thought of how when I first went to cover a war, long ago in Bosnia, I carried with me a pocket-sized book of poems by the World War I poets Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, and Robert Graves. Somehow, the poignancy and pain of the poetry helped me understand the brutality of war in a more profound way.

In Lviv, I felt an intense solidarity among the writers who had gathered. “Intellectuals from all over the world coming together in Ukraine to discuss how justice and truth can prevail is already part of the solution,” Amelina told me.

That night, some of us boarded an overnight train to Kyiv in high spirits, carrying bags of fruit and bottles of whiskey. We arrived after dawn in the capital, unaware that we would soon witness Russian President Vladimir Putin’s wrath: missile attacks on Lviv, Kyiv, and other Ukrainian cities. We were sent to bomb shelters, waiting it out with locals along with their children and pets. Plates of cookies and tea were brought out; people pulled out books and computers. A seminar that was meant to take place in the hotel upstairs carried on in a corner of the parking garage that was our new home for the time being.

And I kept thinking of something that Mykhed had told listeners only a few days before in Lviv. “More talented writers of the next generations will take this raw material and make a beautiful novel about it,” he said. “But being in the center of the hurricane, you just try to grab the tiniest moments of your grief, the tiniest moments of your scream.”

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lawrence Ferlinghetti 1919-2021

We are sad to announce that Lawrence Ferlinghetti, distinguished American poet, artist, and founder of City Lights Booksellers and Publishers, has died in San Francisco, California. He was 101 years old.

Ferlinghetti was instrumental in democratizing American literature by creating (with Peter D. Martin) the country’s first all-paperback bookstore in 1953, jumpstarting a movement to make diverse and inexpensive quality books widely available. He envisioned the bookstore as a “Literary Meeting Place,” where writers and readers could congregate to shares ideas about poetry, fiction, politics, and the arts. Two years later, in 1955, he launched City Lights Publishers with the objective of stirring an “international dissident ferment.” His inaugural edition was the first volume of the City Lights Pocket Poets Series, which proved to be a seminal force in shaping American poetry.

Ferlinghetti is the author of one of the best-selling poetry books of all time, A Coney Island of the Mind, among many other works. He continued to write and publish new work up until he was 100 years old, and his work has earned him a place in the American canon.

For over sixty years, those of us who have worked with him at City Lights have been inspired by his knowledge and love of literature, his courage in defense of the right to freedom of expression, and his vital role as an American cultural ambassador. His curiosity was unbounded and his enthusiasm was infectious, and we will miss him greatly.

We intend to build on Ferlinghetti’s vision and honor his memory by sustaining City Lights into the future as a center for open intellectual inquiry and commitment to literary culture and progressive politics. Though we mourn his passing, we celebrate his many contributions and give thanks for all the years we were able to work by his side.

…

For media inquiries, contact Stacey Lewis: [email protected]

Source: citylightsbooks

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Cause you know Logo and Kantbot, I assume you know that Giant Gio guy. Any thoughts on him? To me he kinda seemed to be very conformist in a way - what I mean that even if he tries to cover his language in esoteric language it seems he at the end resorts to the standard e-right talking points, hell compare his twitter feed to logos - the latter even if he says something stupid atleast says something novelle or interesting while Gio just seems to retweet dunks on "libtards" and just whine using 4chan memes that got stale in 2016 (and the newer ones he uses make it look more like he is tying to fit in)

I'm going to have to rebrand this site as The New York Review of 2010s Right-Wing Dissidents. Anyway, I can't help but like Gio on an affective or aesthetic level. He's sort of the opposite of Kantbot: under whatever the politics are, the personality is sound, at once jovial and passionate. And the politics in his case are based on so particular a wound, one I understand by virtue of not quite having had to suffer it: if I recall his life story properly, his people come from Italy by way of Latin America and ended up in...Canada, which is to say, or as he would say, not quite anywhere. As someone with a similar heritage but who has by luck of geography been able to inherit the very rich somewhere that is the United States, I can understand how he got where he did even if I can't approve. He's capable of genuine imaginative sensitivity and sympathy, though—listen to what he's actually saying under the shock-jock bluster on the Nin episode of Art of Darkness, which inspired me to finally read carefully, as literature and not as pornography, my father's old copy of Delta of Venus that I've been carrying around for decades—and he doesn't actually hate women for all that he's philosophically anti-feminist or rooted in the incel-manosphere. He's studied the Marxists and postmodernists and therefore doesn't have the dunderheaded "Adorno started Black Lives Matter" type of attitude so common on the right. I'm not versed in everything he's said and done and don't endorse any or most or all of it, I'm sure; this is just an aesthetic evaluation. You're correct that he's obviously marinated in the old 4chan style, which could stand to be updated or discarded, and that he's invested in a coarse political polemic that does his art and intellect no favors. I would rather see him become an apolitical artist-theorist than a conservative pundit, even of the mainstream variety.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Today we present a preview of a major new biography of Sylvia Plath, Red Comet, coming this fall. Through committed investigative scholarship, Heather Clark is able to offer the most extensively researched and nuanced view yet of a poet whose influence grows with each new generation of readers. Clark is the first biographer to draw upon all of Plath's surviving letters, including fourteen newly discovered letters Plath sent to her psychiatrist in 1961-63, and to draw extensively on her unpublished diaries, calendars, and poetry manuscripts. She is also the first to have had full, unfettered access to Ted Hughes's unpublished diaries and poetry manuscripts, allowing her to present a balanced and humane view of this remarkable creative marriage (and its unravelling) from both sides. She is able to present significant new findings about Plath's whereabouts and her state of health on the weekend leading up to her death. With these and many other "firsts," Clark's approach to Plath is to chart the course of this brilliant poet's development, highlighting her literary and intellectual growth rather than her undoing. Here, we offer a passage from Clark's prologue to the biography, followed by lines from one of Plath's celebrated "bee poems."

from Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath

The Oxford professor Hermione Lee, Virginia Woolf’s biographer, has written, “Women writers whose lives involved abuse, mental-illness, self-harm, suicide, have often been treated, biographically, as victims or psychological case-histories first and as professional writers second.” This is especially true of Sylvia Plath, who has become cultural shorthand for female hysteria. When we see a female character reading The Bell Jar in a movie, we know she will make trouble. As the critic Maggie Nelson reminds us, “to be called the Sylvia Plath of anything is a bad thing.” Nelson reminds us, too, that a woman who explores depression in her art isn’t perceived as “a shamanistic voyager to the dark side, but a ‘madwoman in the attic,’ an abject spectacle.” Perhaps this is why Woody Allen teased Diane Keaton for reading Plath’s seminal collection Ariel in Annie Hall. Or why, in the 1980s, a prominent reviewer cracked his favorite Plath joke as he reviewed Plath’s Pulitzer Prize–winning Collected Poems: “ ‘Why did SP cross the road?’ ‘To be struck by an oncoming vehicle.’ ” Male writers who kill themselves are rarely subject to such black humor: there are no dinner-party jokes about David Foster Wallace.

Since her suicide in 1963, Sylvia Plath has become a paradoxical symbol of female power and helplessness whose life has been subsumed by her afterlife. Caught in the limbo between icon and cliché, she has been mythologized and pathologized in movies, television, and biographies as a high priestess of poetry, obsessed with death. These distortions gained momentum in the 1960s when Ariel was published. Most reviewers didn’t know what to make of the burning, pulsating metaphors in poems like “Lady Lazarus” or the chilly imagery of “Edge.” Time called the book a “jet of flame from a literary dragon who in the last months of her life breathed a burning river of bale across the literary landscape.” The Washington Post dubbed Plath a “snake lady of misery” in an article entitled “The Cult of Plath.” Robert Lowell, in his introduction to Ariel, characterized Plath as Medea, hurtling toward her own destruction.

Recent scholarship has deepened our understanding of Plath as a master of performance and irony. Yet the critical work done on Plath has not sufficiently altered her popular, clichéd image as the Marilyn Monroe of the literati. Melodramatic portraits of Plath as a crazed poetic priestess are still with us. Her most recent biographer called her “a sorceress who had the power to attract men with a flash of her intense eyes, a tortured soul whose only destiny was death by her own hand.” He wrote that she “aspired to transform herself into a psychotic deity.” These caricatures have calcified over time into the popular, reductive version of Sylvia Plath we all know: the suicidal writer of The Bell Jar whose cultish devotees are black-clad young women. (“Sylvia Plath: The Muse of Teen Angst,” reads the title of a 2003 article in Psychology Today.) Plath thought herself a different kind of “sorceress”: “I am a damn good high priestess of the intellect,” she wrote her friend Mel Woody in July 1954.

Elizabeth Hardwick once wrote of Sylvia Plath, “when the curtain goes down, it is her own dead body there on the stage, sacrificed to her own plot.” Yet to suggest that Plath’s suicide was some sort of grand finale only perpetuates the Plath myth that simplifies our understanding of her work and her life. Sylvia Plath was one of the most highly educated women of her generation, an academic superstar and perennial prizewinner. Even after a suicide attempt and several months at McLean Hospital, she still managed to graduate from Smith College summa cum laude. She was accepted to graduate programs in English at Columbia, Oxford, and Radcliffe and won a Fulbright Fellowship to Cambridge, where she graduated with high honors. She was so brilliant that Smith asked her to return to teach in their English department without a PhD. Her mastery of English literature’s past and present intimidated her students and even her fellow poets. In Robert Lowell’s 1959 creative writing seminar, Plath’s peers remembered how easily she picked up on obscure literary allusions. “ ‘It reminds me of Empson,’ Sylvia would say . . . ‘It reminds me of Herbert.’ ‘Perhaps the early Marianne Moore?’ ” Later, Plath made small talk with T. S. Eliot and Stephen Spender at London cocktail parties, where she was the model of wit and decorum.

Very few friends realized that she struggled with depression, which revealed itself episodically. In college, she aced her exams, drank in moderation, dressed sharply, and dated men from Yale and Amherst. She struck most as the proverbial golden girl. But when severe depression struck, she saw no way out. In 1953, a depressive episode led to botched electroshock therapy sessions at a notorious asylum. Plath told her friend Ellie Friedman that she had been led to the shock room and “electrocuted.” “She told me that it was like being murdered, it was the most horrific thing in the world for her. She said, ‘If this should ever happen to me again, I will kill myself.’ ” Plath attempted suicide rather than endure further tortures.

In 1963, the stressors were different. A looming divorce, single motherhood, loneliness, illness, and a brutally cold winter fueled the final depression that would take her life. Plath had been a victim of psychiatric mismanagement and negligence at age twenty, and she was terrified of depression’s “cures,” as she wrote in her last letter to her psychiatrist—shock treatment, insulin injections, institutionalization, “a mental hospital, lobotomies.” It is no accident that Plath killed herself on the day she was supposed to enter a British psychiatric ward.

Sylvia Plath did not think of herself as a depressive. She considered herself strong, passionate, intelligent, determined, and brave, like a character in a D. H. Lawrence novel. She was tough-minded and filled her journal with exhortations to work harder—evidence, others have said, of her pathological, neurotic perfectionism. Another interpretation is that she was—like many male writers—simply ambitious, eager to make her mark on the world. She knew that depression was her greatest adversary, the one thing that could hold her back. She distrusted psychiatry—especially male psychiatrists—and tried to understand her own depression intellectually through the work of Fyodor Dostoevsky, Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Virginia Woolf, Thomas Mann, Erich Fromm, and others. Self-medication, for Plath, meant analyzing the idea of a schizoid self in her honors thesis on The Brothers Karamazov.

Bitter experience taught her how to accommodate depression—exploit it, even—in her art. “There is an increasing market for mental-hospital stuff. I am a fool if I don’t relive, or recreate it,” she wrote in her journal. The remark sounds trite, but her writing on depression was profound. Her own immigrant family background and experience at McLean gave her insight into the lives of the outcast. Plath would fill her late work, sometimes controversially, with the disenfranchised—women, the mentally ill, refugees, political dissidents, Jews, prisoners, divorcées, mothers. As she matured, she became more determined to speak out on their behalf. In The Bell Jar, one of the greatest protest novels of the twentieth century, she probed the link between insanity and repression. Like Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, the novel exposed a repressive Cold War America that could drive even the “best minds” of a generation crazy. Are you really sick, Plath asks, or has your society made you so? She never romanticized depression and death; she did not swoon into darkness. Rather, she delineated the cold, blank atmospherics of depression, without flinching. Plath’s ability to resurface after her depressive episodes gave her courage to explore, as Ted Hughes put it, “psychological depth, very lucidly focused and lit.” The themes of rebirth and renewal are as central to her poems as depression, rage, and destruction.

“What happens to a dream deferred?” Langston Hughes asked in his poem “Harlem.” Did it “crust and sugar over—/ like a syrupy sweet?” For most women of Plath’s generation, it did. But Plath was determined to follow her literary vocation. She dreaded the condescending label of “lady poet,” and she had no intention of remaining unmarried and childless like Marianne Moore and Elizabeth Bishop. She wanted to be a wife, mother, and poet—a “triple-threat woman,” as she put it to a friend. These spheres hardly ever overlapped in the sexist era in which she was trapped, but for a time, she achieved all three goals.

They thought death was worth it, but I Have a self to recover, a queen. Is she dead, is she sleeping? Where has she been, With her lion-red body, her wings of glass?

Now she is flying More terrible than she ever was, red Scar in the sky, red comet Over the engine that killed her— The mausoleum, the wax house.

from “Stings” by Sylvia Plath

More on this book and author:

Learn more about Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark

Learn more about Heather Clark

Share this poem and peruse other poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series

To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link

146 notes

·

View notes

Photo

LAWRENCE FERLINGHETTI

March 24, 1919 (Yonkers, NY) - February 22, 2021 (San Francisco, CA

)

We are sad to announce that Lawrence Ferlinghetti, distinguished American poet, artist, and founder of City Lights Booksellers and Publishers, has died in San Francisco, California. He was 101 years old.

Ferlinghetti was instrumental in democratizing American literature by creating (with Peter D. Martin) the country's first all-paperback bookstore in 1953, jumpstarting a movement to make diverse and inexpensive quality books widely available. He envisioned the bookstore as a "Literary Meeting Place," where writers and readers could congregate to shares ideas about poetry, fiction, politics, and the arts. Two years later, in 1955, he launched City Lights Publishers with the objective of stirring an "international dissident ferment." His inaugural edition was the first volume of the City Lights Pocket Poets Series, which proved to be a seminal force in shaping American poetry.

Ferlinghetti is the author of one of the best-selling poetry books of all time, A Coney Island of the Mind, among many other works. He continued to write and publish new work up until he was 100 years old, and his work has earned him a place in the American canon.

For over sixty years, those of us who have worked with him at City Lights have been inspired by his knowledge and love of literature, his courage in defense of the right to freedom of expression, and his vital role as an American cultural ambassador. His curiosity was unbounded and his enthusiasm was infectious, and we will miss him greatly.

We intend to build on Ferlinghetti's vision and honor his memory by sustaining City Lights into the future as a center for open intellectual inquiry and commitment to literary culture and progressive politics. Though we mourn his passing, we celebrate his many contributions and give thanks for all the years we were able to work by his side.

- City Lights Books

7 notes

·

View notes