#argentarii

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

El arco de los argentarios es uno de los monumentos que pasan más desapercibidos en Roma y para mí, es uno de los más espectaculares. Fue construido por los banqueros y comerciantes en el Foro Boario a la familia de los Severos.

Caracalla se encargó bien de quitar las inscripciones en referencia a su esposa y a su hermano Geta. Una Damnatio memoriae en toda regla. En la imagen se aprecia el relieve de Septimio Severo y Julia Domna. Como curiosidad, Julia aparece ligeramente en una posición más alta que su esposo. Y algo más, contemplad los símbolos que les añaden en su parte inferior: el apex, simpulum, el lituus, etc., todo ello en clara representación como máximos exponentes de la religión romana.

#arqueologia#historia#culture#history#archaeology#antiguaroma#restosromanos#roma#travel#emperor geta#emperor caracalla#severo#juliadomna#arco romano#arch#argentarii#argentarios#foroboario

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Clivus Argentarius, Roma, 2nd century BC

(English / Español / Italiano)

Rome, The Clivus Argentarius is an ancient Roman road built in the 2nd century BC between the Capitol and the Roman Forum, partial remains of which are still visible today.

The name 'argentarius' derives from the proximity of the clivo to the area where the bankers and money changers (argentarii) carried out their activities near the Forum.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Roma, El Clivus Argentarius es una antigua calzada romana construida en el siglo II a.C. entre el Capitolio y el Foro Romano, de la que aún hoy pueden verse restos parciales.

El nombre "argentarius" deriva de la proximidad del clivo a la zona donde los banqueros y cambistas (argentarii) desarrollaban sus actividades cerca del Foro.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Roma, Il Clivus Argentarius è un’antica strada romana costruita nel II secolo a.C. situata tra il Campidoglio e il Foro Romano e i cui resti parziali sono ancora oggi visibili .

Il nome “argentarius” deriva dalla vicinanza del clivo alla zona dove operavano i banchieri e cambiavalute (argentarii), che svolgevano le loro attività nei pressi del Foro.

Source: Roma Ieri E Oggi by Elio Minerva

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Uma Perspectiva Histórica sobre a Evolução do Crédito e seu Impacto no Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social

O crédito tem desempenhado um papel crucial na história econômica e social, atuando como um catalisador de inovações, financiando empreendimentos ambiciosos e estruturando dinâmicas de poder. Desde suas origens nas civilizações antigas até sua configuração no sistema financeiro global contemporâneo, a história do crédito destaca tanto seu potencial para impulsionar o progresso humano quanto os riscos inerentes à sua má gestão.

1. Origens e Desenvolvimento Inicial do Crédito

As raízes do crédito remontam a sociedades agrárias, como o Egito Antigo, onde os templos assumiam funções financeiras, concedendo empréstimos lastreados em cereais e metais preciosos. Esses sistemas, fundamentados em confiança e reciprocidade, eram rigorosamente documentados para garantir a segurança das transações (Silver, 1983). É importante lembrar que, embora os cereais fossem usados como unidade de conta, o Egito Antigo já utilizava moedas metálicas, como anéis de ouro e prata. Na Grécia Clássica, contratos de crédito eram cruciais para o comércio marítimo, mas expunham os comerciantes a riscos significativos, como a perda de bens e liberdade em caso de inadimplência (Harris, 2006). Já no Império Romano, instituições como os argentarii estabeleceram a base do crédito urbano, com regulamentações detalhadas no Corpus Juris Civilis para equilibrar as relações entre credores e devedores (Jones, 1974).

2. A Influência de Valores Culturais e Religiosos

Valores culturais e religiosos moldaram profundamente as práticas de crédito ao longo da história. A condenação da usura pela Igreja Católica, que teve grande influência na Europa medieval, não impediu o desenvolvimento de formas de crédito, mas estimulou a busca por alternativas como as letras de câmbio, que disfarçavam a cobrança de juros. No Islã, a proibição do riba levou à criação de modelos financeiros baseados na participação nos lucros e nos riscos compartilhados (Kuran, 2011). Na China Imperial, sistemas de crédito cooperativo emergiram, mas frequentemente reforçavam desigualdades, favorecendo as elites locais (Von Glahn, 1996). Essas abordagens refletem as tensões entre as necessidades econômicas e os imperativos éticos de cada sociedade.

3. Transformações Históricas no Crédito

A história do crédito foi moldada por eventos significativos, como a Revolução Industrial, que reconfigurou profundamente as estruturas financeiras. Durante esse período, o crédito sustentou inovações tecnológicas e a expansão de infraestrutura, transformando economias predominantemente agrárias em sistemas industriais avançados (Cameron & Neal, 2016). As guerras mundiais do século XX levaram a uma mobilização massiva de recursos financeiros, com os Estados utilizando o crédito como ferramenta estratégica. Mais recentemente, crises como a Grande Depressão e o colapso financeiro de 2008 evidenciaram vulnerabilidades do sistema financeiro global, sublinhando a necessidade de regulamentações mais robustas (Reinhart & Rogoff, 2009).

4. Exemplos Regionais no Uso do Crédito

Regiões fora do eixo europeu também apresentaram inovações notáveis no uso do crédito. Na África Ocidental, sistemas tradicionais de poupança e crédito, como os tontines, ajudaram comunidades a superar barreiras econômicas. Na América Latina, iniciativas de microcrédito em países como o Brasil e a Colômbia ampliaram o acesso financeiro para pequenos empreendedores, demonstrando como o crédito pode ser uma ferramenta poderosa para inclusão social (Banerjee & Duflo, 2011).

5. Desafios Contemporâneos do Crédito

Atualmente, o crédito enfrenta desafios complexos. A desigualdade no acesso ao crédito agrava disparidades econômicas e sociais, enquanto o superendividamento ameaça a estabilidade financeira de indivíduos e nações. Além disso, a sustentabilidade ambiental exige que o crédito seja direcionado para financiar iniciativas em energias renováveis e infraestrutura verde (Rockström et al., 2017). Tecnologias emergentes, como blockchain e fintechs, oferecem potencial para democratizar o acesso ao crédito, mas levantam preocupações éticas e desafios regulatórios (Casey & Vigna, 2018). É importante ressaltar que o blockchain, embora tenha ganhado grande visibilidade nos últimos anos, ainda é uma tecnologia em desenvolvimento e sua aplicação em larga escala no sistema financeiro ainda enfrenta obstáculos.

6. Perspectivas Futuras e Recomendações

Para que o crédito continue a desempenhar seu papel de motor do desenvolvimento, são necessárias ações concretas que combinem inovação tecnológica e responsabilidade social. Políticas públicas de inclusão financeira devem ser priorizadas para expandir o acesso ao crédito para pequenas empresas e comunidades marginalizadas. Além disso, a educação financeira é essencial para mitigar o superendividamento e empoderar economicamente os indivíduos. Regulamentações robustas são indispensáveis para proteger consumidores e assegurar a integridade do sistema financeiro. Por fim, a inovação tecnológica deve ser direcionada para criar sistemas de crédito mais inclusivos, transparentes e resilientes.

Conclusão

A história do crédito é um testemunho de sua capacidade de moldar economias e sociedades. Contudo, seu impacto depende de como é administrado e direcionado. Para garantir que o crédito continue a promover a prosperidade e reduzir desigualdades, é essencial equilibrar inovação e responsabilidade. Apenas um sistema financeiro ético, inclusivo e sustentável pode enfrentar os desafios do século XXI, transformando o crédito em uma força para o bem comum.

Referências

Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2011). Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty. PublicAffairs.

Cameron, R., & Neal, L. (2016). A Concise Economic History of the World: From Paleolithic Times to the Present. Oxford University Press.

Casey, M. J., & Vigna, P. (2018). The Truth Machine: The Blockchain and the Future of Everything. St. Martin's Press.

Harris, E. M. (2006). Democracy and the Rule of Law in Classical Athens: Essays on Law, Society, and Politics. Cambridge University Press.

Jones, A. H. M. (1974). The Roman Economy: Studies in Ancient Economic and Administrative History. Blackwell.

Kuran, T. (2011). The Long Divergence: How Islamic Law Held Back the Middle East. Princeton University Press.

Le Goff, J. (2010). Your Money or Your Life: Economy and Religion in the Middle Ages. Zone Books.

Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2009). This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton University Press.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., & Noone, K. (2017). Sustainability Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Nature Publishing Group.

Silver, M. (1983). Economic Structures in Antiquity. Croom Helm.

Von Glahn, R. (1996). Fountain of Fortune: Money and Monetary Policy in China, 1000-1700. University of California Press.

0 notes

Text

Roma, Il Clivus Argentarius è un’antica strada romana costruita nel II secolo a.C. situata tra il Campidoglio e il Foro Romano e i cui resti parziali sono ancora oggi visibili .

Il nome “argentarius” deriva dalla vicinanza del clivo alla zona dove operavano i banchieri e cambiavalute (argentarii), che svolgevano le loro attività nei pressi del Foro.

1 note

·

View note

Text

SPIRITUS, CLASIS, SOCIETATIS INTERACTION

operarii mercenarii, qui pro illis laborant et operarii qui praedia colunt, quartum praedium seu proletarium sic dictum constituent.

Non est credendum id, quod superioris ordinis est, semper superiorem statum oeconomicum in tuto collocare. Magna pars clericorum et minorum nobilium nulla locupletior est quam legati tertii status et opifices, professionales, mercatores et argentarii maiorem semper potentiam oeconomicam acquirunt. Haec una ex maximis causis motus revolutionarios oritur (primum Revolutionem Anglicam, deinde Americanam et Gallicam).

Pauperes ditari

Nuper Medii Aevi tempus est in quo municipia et urbes elaboraverunt, urbes quae in primo Medio Aevo plena declinatione erant. Novus bourgeoisis mercantilium narum civitatis communitatis constituit et novam progressionem oeconomicam dabit. Unde nova mercatura bourgeoisie venit? Henricus Pirenne historicus Belgicus (1862-1935), postquam exclusis ex colonis qui sedem stabilem in magnis praediis possessionibus habent, proferre potest hypothesin suggestivam quam hoc loco referimus.

"Ut mirum hoc videri potest, restat ergo sola solutio: mercatores habent maiores pauperes, id est homines sine terra, massam fluctuantem quae percurrit regionem, quae in messe locatur, rebus dicatum." Exceptio venetorum, quorum lacunas fecerunt piscatores et conflatores salis ab initio, qui mercatum byzantinum suppeditant. omnia lucrari qui non habet terram homo est homo qui sibi soli innititur et qui de nullo sollicitus est sed sunt periti et periti homines qui viderunt mundum qui sciunt linguas et qui noverunt diversas consuetudines et quem paupertas facit ingeniosum. Ex hac faece dubitamus, pi- prima.

sanus et Januensis. In septentrione vero Europae isti Scandiani qui Constantinopolim proficiscebantur, quid erant nisi homines sine possessionibus et fortuna quaererent?

Fortunam quaerens - hoc verbum est. Multi non invenerunt, et in praeliis interierunt, vel paupertate exstirpati sunt. Sed alii successerunt. Cum nihil, hoc est, in nihil nisi virtute, mente, audacia fortunam suam reddiderunt. […] Successit aliquis in expeditione piratica, portum Musulmanum diripuit, navem onerariam captam. Reversus est, et subito potest aliquos pauperes daemonia conducere et inire, vel aliquod vile frumentum alicubi emere et illud capere, ubi saevit fames, multo pretiosius vendere […]. Negotiatores professionales nondum sunt, sed unum facti sunt. Ita fiunt, cum commercium decisive transformat ut vita quaedam in se fiat, extraneus ab hodierno adventurous vita. Inde mansiones perpetuas capiunt. Residentiae indigent, quia revera in operationes negotiationis normales ingressi sunt. Ad eorum conversationem consistunt in loco. Iuxta portum, locus receptui navium, in civitate episcopali bene situata».

(Sumpta ab: Henri Pirenne, Historia Europae ab incursionibus usque ad saeculum XVI, Sansoni, Firenze 1956, pp. 148-149).

0 notes

Photo

Yet another sketch of R’phael’s Garlean half-brother, Lucius.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Los imperios pasan

Voy a tratar de contar un cuento. Que no parezca verdad ni mentira, sino todo lo contrario. Desde la creación y conquista de Roma por parte de los etruscos, estuvo regida por Reyes y por la República, periodo de la historia de Roma como forma de gobierno que se extiende desde el 510 a.C., cuando se puso fin a la monarquía con la expulsión del último rey, Lucio Tarquino el Soberbio, hasta el 27…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Romulus - The Dreaded One

Yesterday Romulus turned six so maybe it was time to give him a small bio and the scene he deserves? Romulus is a black market banker, lawyer and a senator. One of the members of Sapientia Paucis, one of the local gangs. No one looks forward to him knocking on the door...

Like most cities Civitas Aurorae does have an official bank, open week days and where people can get service from Daedalos. It’s open, easy and public. Everything is done in the light. Romulus tends to work more in the grey zone. His business hours are all hours of the day. He stores money that you want to keep secret. He lends money to those in need, most of them desperate. And if you can’t pay back in time he most definitely will send one of his fellow gang members to beat you up. Don’t worry, he would never kill you since he needs you to pay him back. Every last gem. Apart from being an unscrupulous argentari he is also a superb lawyer. Romulus has a way with words and always studies his opponent, which is usually one of his fellow senators or a Praetorian guards. No one has ever been able to prove that Romulus is a member of SP which is probably one of the reasons why he is still a senator. Oh gosh, yeah, he is also very well connected. Like any decent politician should be. He enjoys the company of Argentum but wouldn’t trust him around his money. Actually he doesn’t really trust any of them except for Naevia, at least not concerning money. According to him, Naevia and Angerona are the ones most trustworthy yet they are still questionable characters. Money-changers or the argentarii who worked at the tabernae argentariae which were the equivalent of banks exchanged coins (foreign coins to Roman ones).

11 notes

·

View notes

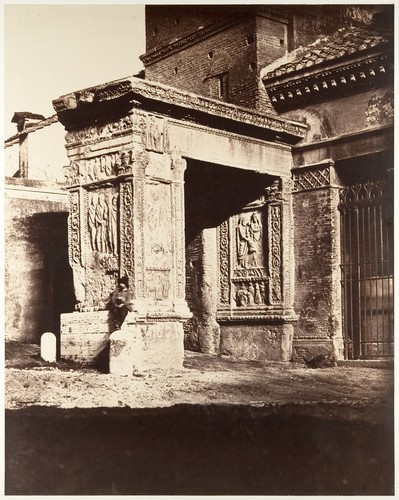

Photo

[Arch of the Argentarii, or, Goldsmith's Gate, Rome] by Unknown, Metropolitan Museum of Art: Photography

Purchase, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1987 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY Medium: Albumen silver print from glass negative

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/265076

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Todos estos objetos los manufacturaban los artesanos (argentarii artífices) en las fabricae del comitatus del emperador o del palatium, dependientes del Comes sacrarum largitionum. Una norma del Codex Justinianus lo especifica: ornamenta regia intra aulam meam fieri a palatinis artificibus debent «los ornamentos regios se deben hacer en mi palatium por los artifices [artesanos] palatinos». Una multitud enorme de personas estaba encargada de ocuparse continuamente de los insignia imperiales, así como de los yelmos, corazas, decoración de los carros, vestimenta, etc., para que estuvieran siempre a su disposición.

Javier Arce.

0 notes

Photo

Las obligaciones en general

Objeto de los contratos

Es la manera en que se da la obligación, es el requisito al que deben sujetarse los sujetos para que exista el contrato. La forma era la manera de comprobar la relación contractual, de este modo, se podía, en un futuro, obligar a cumplir con lo prometido en el contrato, de lo contrario, el pretor tenía que dar validez a lo dicho entre las partes. Objeto de los contratos.

El objeto es toda realización de determinada conducta por parte de uno de los sujetos, consistente en un dar, hacer o prestar

Este tercer elemento, esencial de los contratos, debía reunir los siguientes elementos para ser válido: posible, lícito, determinado y apreciable en dinero.

Posible. Respecto a que estuviera dentro del comercio, tanto físico como jurídico.

Lícito. La cosa debe de ser permitida en ley y si estuviera fuera de ésta es ilícita.

Determinado. Desde el momento que los sujetos contraten, el objeto debe ser definido, o después de que se contrajera la obligación se podía cambiar, siempre y cuando, sea ligado con la misma obligación, como se verá en el próximo ejemplo.

Apreciable en dinero. Como su nombre lo dice, la obligación deberá ser pagada en dinero, por ejemplo, cuando se obligaba a realizar una permuta de algunos animales, si uno o varios, objeto de la permuta se perdían, era factible que se pagara en dinero.

Causa de los contratos

Ya se vio que la validez de los contratos depende de la forma, ahora bien, la causa es lo que impulsa a las personas para realizar el negocio jurídico. Un ejemplo claro, es en un contrato de compra-venta, la causa por la que se quiere vender el objeto es el tener dinero, y la causa del deudor, es adquirir la cosa. Aquí, la conducta del deudor podía marcarse ilícitamente, llegando a convalidarse el fraude a la ley, fraus legis, en contra del acreedor, o bien, viceversa, o la simulación. Por ejemplo, fraude sería cuando el acreedor vende un esclavo y el deudor no paga lo acordado. Por otro lado, simulación es el realizar un acto jurídico fingido, disfrazado, por ejemplo, en época romana las donaciones en determinados casos estaban prohibidas, siendo que podían fingir una compra-venta de un esclavo, pero en verdad lo donaban.

Forma de los contratos.

Es la manera en que se da la obligación, es el requisito al que deben sujetarse los sujetos para que exista el contrato. La forma era la manera de comprobar la relación contractual, de este modo, se podía, en un futuro, obligar a cumplir con lo prometido en el contrato, de lo contrario, el pretor tenía que dar validez a lo dicho entre las partes.

Pactos vestidos.

Pactos nudos: En los inicios sólo daban origen a obligaciones naturales. Pactos vestidos: Son los pactos dotados por el praetor y por la legislación, de eficacia procesal. Pactos pretorios: figuraban:

Constitutum. Acuerdo de las partes por el cual una de ellas, prometía a la otra, pagar en fecha determinada, una deuda preexistente propia o ajena.

Receptitium argentarii. Cuando el banquero prometía pagar a un tercero una suma de dinero por cuenta de su cliente.

Receptitium arbitrarii. Cuando una persona aceptaba ser árbitro para decidir un litigio.

Receptitium nautarum, Cauponum et stabularis. Se daba cuando armadores, posaderos y estableros se hacían responsables de las cosas confiadas a su guarda.

Pacto de juramento. Las partes convenían en que una futura controversia fuera decidida mediante juramento.

Elementos accidentales de los contratos.

Son aquellos que las partes establecen por cláusulas especiales, que no sean contrarias a la ley, la moral, las buenas costumbres, o el orden público. Por ejemplo: el plazo, la condición, el modo, la solidaridad, la indivisibilidad, la representación, etc. En consonancia con la autonomía de la voluntad, los contratantes pueden establecer los pactos, cláusulas y condiciones que tengan por convenientes, siempre que no sean contrarios a la ley, la moral, los buenos usos y costumbres, o el orden público. Estos elementos se conocen bajo el nombre de modalidades.

La condición

Es un hecho futuro e incierto, del cual depende el nacimiento o extinción de un derecho. Por ejemplo: “ Te regalo mi paraguas si llueve mañana”. De ello se colige que los elementos constitutivos de la condición son dos:

Es necesario que el hecho sea futuro.

Es necesario que el hecho sea incierto.

El término.

Es la fecha cierta para cumplir con el negocio jurídico. El plazo puede ser suspensivo o inicial, y resolutorio; el primero se interpreta que desde que se crea el consentimiento de celebrar el acto jurídico, se inicial la fecha, ex die, para cumplir con la obligación. El segundo es cuando el negocio termina, in diem, o sea, la obligación estará vigente hasta que se cumpla el plazo.

Modo o carga.

Consiste en un gravamen impuesto al beneficiario en un acto de liberalidad, pero tan solo en una donación, legado o manumisión, por ejemplo, en paterfamilias dejaba como herencia un terreno a su hijo, siempre y cuando construya una vivienda para su familia.

Interpretación de los contratos.

Es la acción o efecto de explicar o declarar el sentido de una cosa, y principalmente el de textos faltos de claridad.

Interpretación Legal: Jurídicamente tiene importancia la interpretación dada a la ley por la jurisprudencia y por la doctrina, así como la que se hace de los actos jurídicos en general y de los contratos y testamentos en particular, ya que en ocasiones sucede que el sentido literal de los conceptos resulta dubitativo o no coincide con la que se presume haber sido la verdadera intención de los contratantes o del testador; interpretación indispensable para hacer que, como es justo, la voluntad de los interesados prevalezca sobre las palabras.

Las Leyes de Partidas definían la interpretación como la verdadera, recta y provechosa inteligencia de la ley según la letra y la razón.

La interpretación de la ley recibe varias denominaciones teniendo en cuenta su procedencia.

Es auténtica: cuando se deriva del pensamiento de los legisladores, expuesto en los debates parlamentarios que la sancionaron;

Es usual: cuando consta en la jurisprudencia de los tribunales, sentada para aplicar la norma a cada caso concreto, y que tiene especial importancia en aquellos países en que las sentencias de los tribunales de casación obligan a los tribunales inferiores a su absoluto acatamiento, y es,

Doctrinal: cuando proviene de los escritos y comentarios de los jurisperitos, siempre discrepante entre sí y sin otro valor que el de la fuerza convincente del razonamiento.

Invalidez.

Un negocio jurídico al que, por defectos en su constitución, el ordenamiento jurídico no le reconoce efectos, se dice que es inválido. Las causas de ello estarán en faltas o vicios graves recaídos en requisitos esenciales, o se deberán a prohibiciones expresas en las leyes

La doctrina moderna distingue dos figuras principales de invalidez: la nulidad y la impugnabilidad o anulabilidad.

Es nulo el negocio que adolece de un vicio tal que priva a dicho negocio totalmente del efecto a que tiende. Para el ordenamiento jurídico es como si no existiese. Es inválido por sí, sin necesidad de que nadie pida que así se declare. Tanto las partes que en él intervinieron como los terceros y los órganos judiciales, en su caso, obrarán rectamente desconociéndole, procediendo, en cuanto a las situaciones que con dicho negocio se querían modificar, como si no se hubiese celebrado nunca.

El negocio jurídico impugnable o anulable, como estas expresiones indican, es un negocio que alguien tiene el poder de atacar y privar de eficacia; pero si esa facultad de derribarle no se ejercita, la construcción sigue enhiesta, no obstante su imperfección, y el negocio produce sus efectos. Su invalidez no es actual, sino potencial. Se necesita una reacción contra el negocio, operada por quien tiene el derecho de hacer valer judicialmente el defecto del cual adolece; a falta de tal reacción, el negocio desarrollará todas sus consecuencias

Incumplimiento y consecuencias.

El incumplimiento de una obligación corresponde a la no realización de la prestación debida por parte del deudor al acreedor, y tal incumplimiento puede prestarse en los siguientes casos.

La prestación debida no es realizada en absoluto por el deudor (inejecución de las obligaciones)

La prestación debida es realizada incompletamente o en forma defectuosa.

La prestación debida es realizada fuera del tiempo originariamente acordado

El efecto propio y natural de toda obligación es el cumplimiento de ella por parte del deudor. Lo común y ordinario es que el deudor satisfaga el objeto de la obligación, una vez que esta sea exigible. Se dice entonces que el deudor paga y la obligación queda extinguida por este hecho. En algunos casos la inejecución de obligación o el retraso de su ejecución traen como consecuencias el pago de daños e intereses.

Las obligaciones no se cumplen o ejecutan por tres causas principales: primera, por caso fortuito o fuerza mayor; segunda, por el dolo del deudor, y tercera, por la culpa del mismo.

Consecuencias

Las consecuencias de la inejecución de las obligaciones varían según el objeto. Si este consiste en una suma de dinero u otra cosa in genere, el deudor queda obligado, cualquiera que sea el acontecimiento que le haya impedido pagar lo que debe.

Si el objeto recae sobre un cuerpo cierto o un hecho, las consecuencias de la inejecución dependen de la causa de la misma, si fue por un caso fortuito, por dolo o por falta.

CASO FORTUITO Y FUERZA MAYOR

Se entiende por caso fortuito, en materia de inejecución de las obligaciones, todo hecho imprevisto e independiente de la voluntad del deudor, que trae como consecuencia la imposibilidad de cumplir la obligación. Si este hecho era de tal naturaleza que el deudor no pudiera resistirlo, se denominaba fuerza mayor. Ejemplos: incendio, inundaciones, ataque a mano armada.

Si el incumplimiento total o parcial se debió a fuerza mayor o caso fortuito, el deudor quedaba liberado de su obligación, pues la concurrencia de la fuerza mayor o del caso fortuito extinguía la obligación, y en consecuencia, quedaba eximido de toda responsabilidad. De tal manera que se podía decir que el riesgo de la fuerza mayor o del caso fortuito, en principio, era asumida por el acreedor. Esto es, la equidad exige que el deudor no sea responsable, si la ejecución de la obligación se hizo imposible por caso fortuito o por fuerza mayor. Pero puede modificarse por cláusula contraria.

El dolo

En términos generales el dolos era precisamente lo opuesto a la buena fe, y suponía una voluntado o intención positiva dirigida a obtener un resultado y una acción con dicha voluntad destinada a conseguir el dicho resultado, resultado que podía consistir en un perjuicio en las cosas, o en una frustración de las legitimas expectativas creadas en la contraparte, de modo tal que resultaba engañada. En este contexto, consiste en los actos u omisiones que llevan en sí la intención de causar perjuicio al acreedor y que producen como consecuencia del incumpliendo de la obligación. El elemento esencial en el dolo es la intención de causar daño al acreedor.

El deudor siempre es responsable de su dolo, y las partes contratantes no podían convenir, en ningún caso, en que el deudor no respondiera de este.

La culpa o falta

Se considera como culpa todo acto u omisión del deudor, que sin llevar en si la intención de causar perjuicio al acreedor, produce, sin embargo, el incumplimiento de la obligación por no poderse satisfacer el objeto propio de ella.

En Derecho Romano se han considerado en la culpa de deudor diferentes grados. En primer lugar, se clasifica la culpa en grave o lata y leve.

Culpa grave: Era aquel hecho u omisión del deudor en que no incurrían ni aun las personas negligentes o descuidadas.

Culpa leve: Era aquel acto u omisión imputable al deudor en que no habría incurrido un buen administrador de negocios

En los contratos de buena fe el deudor era responsable tanto de su culpa grave como su culpa leve, si este contrato producía beneficios para el acreedor y para el deudor. Si este contrato no beneficiaba al deudor, este solo respondía de su grave.

En los contratos de derecho estricto, si la obligación era de hacer, el deudor era responsable de toda culpa, ya fuera por acción u omisión. Solo el caso fortuito y la fuerza mayor podían eximirlo de la obligación. Sin embargo, si la obligación era de dar o entregar una cosa determinada, el deudor no era responsable de sus omisiones o negligencias, solo era responsable de sus acciones o hechos.

TEORIA DE LA DEMORA

Es el retraso del cumplimiento de la obligación exigible. Existen dos tipos de mora o demora:

Mora Debitoris (mora solvendi – mora de pagar-) o mora del deudor: Puede definirse como el retraso culpable o doloso por parte del deudor, respecto del cumplimiento de su deber.

Para que exista la mora del deudor son necesarios los siguientes elementos:

Que la obligación fuera exigible; para ello, a su vez, la obligación debía reunir las siguientes circunstancias:

Que fuera una obligación civil y no natural.

Que no existiera una excepción que pudiera oponerle el demandado

Que si se trababa de una obligación sujeta a condición ella se hubiera cumplido o fallado en su caso.

Que si se trataba de una obligación a plazo él se hubiera cumplido

Que hubiera culpa o dolo

Que el acreedor haya requerido del deudor el cumplimiento de la obligación.

Efectos:

Si el objeto de la obligación es un cuerpo cierto , el deudor soportaba los riesgos, es decir, si este cuerpo llegaba a perecer, así fuera por caso fortuito o fuerza mayor, estaba obligado a indemnizar al acreedor por la falta de cumplimiento de la obligación.

Si el objeto consistía en sumas de dinero, el deudor estaba obligado al pago de daños e intereses al acreedor, por los perjuicios que el incumplimiento de la obligación le había causado.

Mora Creditoris o mora del acreedor:

Si el acreedor no quería aceptar el objeto de la obligación que le ofrecía el deudor, se hacía responsable de daños y perjuicios, siempre que su negativa careciera de justa causa y el deudor ofreciera exactamente el objeto convenido en el lugar señalado.

La mora del acreedor no liberaba al deudor de su cumplimiento.

En este caso el deudor queda libre de toda responsabilidad, si la cosa cierta perece los riesgos son para el acreedor; el deudor solo responde de su dolo o su culpa grave. Si el objeto de la obligación recae sobre sumas de dinero el acreedor no podía pedir el pago de intereses.

Extinción de las obligaciones.

El pago

Las obligaciones se extinguen por una serie de hechos que han sido reunidos bajo el título de modos de extinción de las obligaciones, que no tiene un carácter uniforme y que no poseen toda una eficacia igual.

El Vínculo de derecho entre el acreedor y el deudor no estaba llamado a perpetuarse indefinidamente. Debía llegar un momento en que el deudor se libertara de la carga de su obligación y entonces esta última quedaba extinguida.

El medio propio y natural de extinguirse toda obligación era el pago, es decir, la satisfacción del objeto de aquella por parte del deudor.

La novación

Es la extinción de una obligación preexistente y la simultanea creación de otra, jurídicamente distinta de la primera y que a ella sustituye; debiendo tener la nueva obligación un elemento diferente de la anterior.

Este elemento nuevo o diferente podía ser:

Cambio de naturaleza de la obligación

Cambio de acreedor

Cambio de deudor

Adición o supresión de una modalidad

EL MUTUO DISENTIMIENTO

Es cuando el deudor y el acreedor voluntariamente acuerdan hacer desaparecer la obligación. Este tipo de medio de extinción se aplicaba solo en los contratos consensuales, que se perfeccionan por el solo consentimiento de las partes; en virtud de que si el acuerdo de las partes era suficiente para crear la obligación, también era suficiente para extinguirla.

LA CONFUSION

Para que la obligación exista es indispensable la concurrencia de dos elementos personales: un elemento activo, llamado acreedor, y un elemento pasivo, deudor. Si uno de estos desaparece, la obligación no puede subsistir. La confusión se da cuando se reúnen en una sola persona las calidades de acreedor y de deudor, desaparece la dualidad de sujetos del vínculo jurídico, y la obligación queda extinguida de pleno derecho.

ACCEPTILATIO (ACEPTILACION)

Es un modo de disolver las obligaciones nacidas de una stipulatio o de una dictio dotis que básicamente consiste en la realización del acto contrario a aquel por el cual se constituyo la obligación. Así pues, en ella el deudor pregunta al acreedor si tiene por cumplida la prestación debida, a cuya pregunta responde congruentemente el acreedor, de tal manera que concluido el acto se tiene por liberado el deudor ipso iure.

REMISION DE DEUDA (PACTUM DE NON PETENDO)

El pactum de non petendo (pacto de no pedir – remision de deuda -) consistía en un acuerdo informal entre deudor y acreedor en virtud del cual este último declaraba que no reclamara el cumplimiento del deudor, o una declaración de recibo simulado de pago..

COMPENSACION

Por esta se entiende la extinción simultanea de dos deudas, hasta por su diferencia (o sea, la cantidad de la mayor, menos la cantidad de la menor), por el hecho de que el sujeto pasivo de la primera y es el activo de la segunda, y viceversa. Se trata, pues, de una imputación reciproca de lo que dos personas se deben mutuamente.

La compensación es un medio de extinguir las obligaciones en que el deudor y el acreedor son recíprocamente deudores y acreedores entre sí.

0 notes

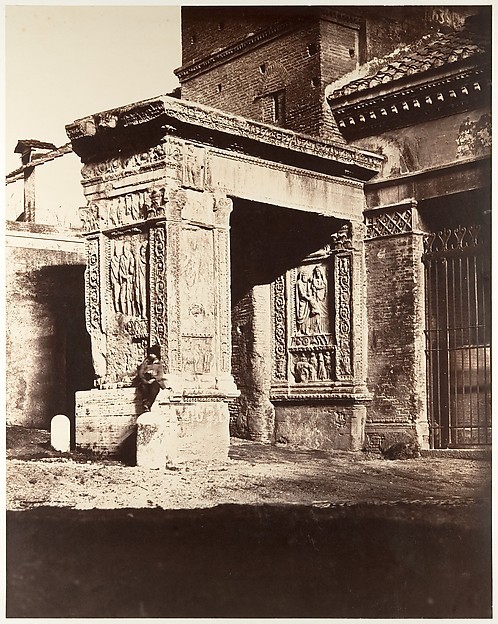

Photo

Arch of the Argentarii, Rome (unknown photographer)

On display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as part of “Paradise of Exiles: Early Photography in Italy,” now through 13 August.

Source

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

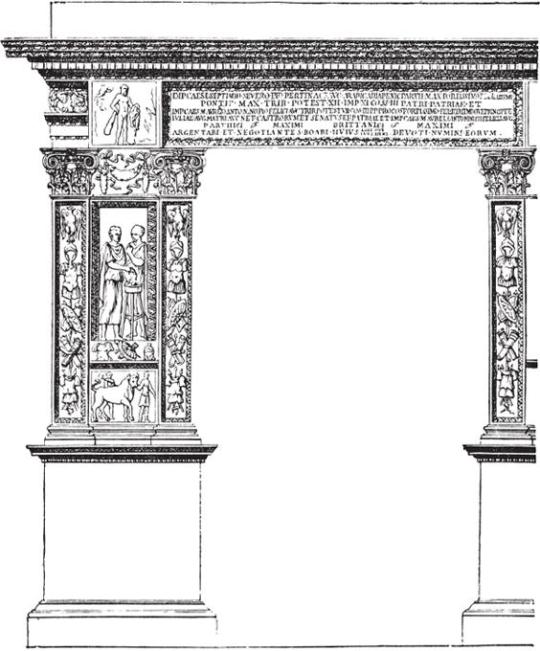

Arcus Argentariorum (Money-changers)

Rome

204 CE

6.15 m high, 3.3 m wide

Its actual purpose is unknown, but the most probable scenario is that it formed a monumental gate where the vicus Jugarius entered the Forum Boarium. As the dedicatory inscription says, it was commissioned not by the state or emperor, but by the local money-changers (argentarii) and merchants (negotiantes), in honour of Septimius Severus and his family. The top was possibly once decorated with statues of the imperial family, now long gone.

It is built of white marble, except for the base which is of travertine. The dedicatory inscription is framed by two bas-reliefs representing Hercules and a genius. The panels lining the passage present two sacrificial scenes - on the right/east, Septimius Severus, Julia Domna and Geta, on the left/west side Caracalla with his wife and father in law Fulvia Plautilla and Gaius Fulvius Plautianus.

The figures of Caracalla's brother, father in law and wife on the passage panels and on the banners on the outside, and their names on the dedicatory inscription, were chiselled out after Caracalla seized sole power and assassinated them.

These sacrificial scenes gave rise to the popular but incorrect saying about the arch that

Tra la vacca e il toro, troverai un gran tesoro

(Between the cow and the bull - i.e., within the arch - , you'll find a great treasure).

This led past treasure-hunters to drill many holes in it, which are still visible.

Above the main reliefs, are smaller panels with Victories or eagles holding up victors' wreaths, and beneath them more sacrificial scenes. The external decoration of the pillars includes soldiers, barbarian prisoners, military banners (with busts of the imperial family) and a now damaged figure in a short tunic

#art#Architecture#travel#history#roman#rome#roma#italy#italian#europe#corinthian#arch#gate#2 ce#septimius severus#roman architecture#roman art

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Banco di San Giorgio la potentissima banca genovese = la sua filiale di Ventimiglia: Argentarii, Nummarii, Banchieri, Tosatori, Alleggeritori, Falsari. L'eccezionalit del 'Principato Ecclesiastico di Seborga'"

Banco di San Giorgio la potentissima banca genovese = la sua filiale di Ventimiglia: Il discorso vale comunque sia per la classicità romana che per il medioevo che per il rinascimento ed oltre basta seguire i link = Argentarii, Nummarii, Banchieri, Tosatori, Alleggeritori, Falsari. L'eccezionalità del 'Principato Ecclesiastico di Seborga' http://ift.tt/2pzg8y7 from Tutto Sapere http://ift.tt/2pzg8y7 via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Exhibition: To Rome and Back: Individualism and Authority in Art, 1500–1800 On view: June 24, 2018–March 17, 2019 Location: Resnick Pavilion

(Los Angeles—May, 2018) The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) is pleased to present To Rome and Back: Individualism and Authority in Art, 1500–1800. Assembled almost entirely from LACMA’s permanent collection, this examination of Rome presents gifts from years of support to the museum’s departments of Costume and Textiles, Decorative Arts and Design, Latin American Art, and Prints and Drawings, in addition to European Painting and Sculpture. The exhibition features 130 objects across a wide range of media, including painting, sculpture, paper, decorative arts (such as ceramics, glass, and cork), tapestries, and costumes. Collectively, these works reveal the importance of Rome to artists and audiences operating in a variety of contexts from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment.

For more than 2,000 years, Rome has occupied a central place in the cultural imagination: as a proud republic, as a powerful then decadent empire, as the seat of Catholicism, and above all, as a link to antiquity and the classical world. While its fortunes may have waxed and waned over its long history, its classical epithet—the Eternal City—reflects the enduring power of its legacy and its unceasing ability to inspire thinkers, writers, and artists in Italy and beyond.

“We’re excited to present an exhibition that highlights collaboration across multiple museum departments,” says Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “By including collection objects and meaningful input from five curatorial areas, we are able to show how the importance of Rome as a source of inspiration is not just about European painting.”

“To Rome and Back is essentially LACMA’s first opportunity to display a significant portion of its European material in a narrative outside of our permanent collection galleries, and effectively showcase some of the museum’s great highlights,” says Leah Lehmbeck, acting department head of European Painting and Sculpture at LACMA and curator of the exhibition. “At the same time, we are providing context with lesser- known objects within the museum’s collection, some of which have rarely been on view.”

Related Programming: Visit lacma.org for the latest on exhibition-related programming. Curator-written tours are available at the beginning of the exhibition. Visitors may choose from three guides focusing on different themes. This exhibition was organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Unknown, Triumph of Peace, 16th century, Wool, silk, and linen tapestry weave, 82 3/4 × 232 in. (210.19 × 589.28 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Giles W. Mead in memory of her husband Giles W. Mead (50.24)

Unknown, Roman copy after Greek original Sometimes attributed to Skopas, The Hope Hygieia, 2nd-century copy, circa 130–161, after a Greek original of circa 360 B.C., Roman, Marble, 75 × 25 × 18 in. (190.5 × 63.5 × 45.72 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, William Randolph Hearst Collection (50.33.23)

Pierre Le Gros II, Saint Thomas, 1703-1704, Terracotta, 27 3/8 × 18 1/2 × 10 3/4 in. (69.53 × 46.99 × 27.31 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Purchased with funds provided by William Randolph Hearst by exchange, The Ahmanson Foundation, Chandis Securities Company, B. Gerald Cantor, Camilla Chandler Frost, Anna Bing Arnold, an anonymous donor, and Duveen Brothers, Inc., Mr. and Mrs. William Preston Harrison, Mr. and Mrs. Pierre Sicard, Colonel and Mrs. George J. Dennis, and Julia Off by exchange (84.1), photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Pompeo Batoni, Portrait of Sir Wyndham Knatchbull-Wyndham, 1758-1759, Oil on canvas, Canvas: 91 3/4 × 63 1/2 in. (233.05 × 161.29 cm), Frame: 107 × 79 × 4 1/2 in. (271.78 × 200.66 × 11.43 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of The Ahmanson Foundation (AC1994.128.1)

Unknown, Cope, 1700-1725, Silk, chenille, and metallic thread embroidery on silver-shot silk taffeta ground, Center back length: 57 7/8 in. (147 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Costume Council Fund (AC1996.62.1), photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Michael Sweerts, Plague in an Ancient City, circa 1652-1654, Oil on canvas, Canvas: 46 3/4 × 64 1/4 in. (118.75 × 163.2 cm), Frame: 62 × 84 × 5 in. (157.48 × 213.36 × 12.7 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of The Ahmanson Foundation (AC1997.10.1), photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Domenico Moglia, The Colosseum, circa 1850, Glass micromosaic on marble, Glass micromosaic on marble, Long-term loan from The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Photo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London / V&A Images

Unknown, Archangel Raphael, circa 1600, Polychromed and gilded wood, 68 1/2 × 36 1/4 × 36 in. (173.99 × 92.08 × 91.44 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Anna Bing Arnold (M.77.52a)

Georges de la Tour, The Magdalen with the Smoking Flame, circa 1638-1640, Oil on canvas, Canvas: 46 1/16 × 36 1/8 in. (117 × 91.76 cm), Frame: 57 1/4 × 47 1/2 × 4 1/2 in. (145.42 × 120.65 × 11.43 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of The Ahmanson Foundation (M.77.73), photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Clodion (Claude Michel), Bacchic Scene, 1773, Terra-cotta, 13 × 14 × 2 in. (33.02 × 35.56 × 5.08 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Art Museum Council Fund (M.80.127), photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Francesco Picano, Circle of Domenico Antonio Vaccaro, Lorenzo Vaccaro, Saint Michael Casting Satan into Hell, 1705, Polychromed wood and glass, 52 1/2 × 27 1/4 × 24 3/4 in. (133.35 × 69.22 × 62.87 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of The Ahmanson Foundation (M.82.7), photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Ludovico Mazzanti, The Death of Lucretia, c. 1730, oil on canvas, 71 × 56 in. (180.3 × 142.2 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of The Ahmanson Foundation (M.82.75), photo © Museum Associates / LACMA

Unknown, Cope, 1700-1725, Silk, chenille, and metallic thread embroidery on silver-shot silk taffeta ground, Center back length: 57 7/8 in. (147 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Costume Council Fund (AC1996.62.1), photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Carl May, Model of the Arch of the Argentarii, circa 1792-1795, Cork, tinted stucco, and sand on modern wood base, Base (On base): 18 × 19 1/2 × 10 1/2 in. (45.72 × 49.53 × 26.67 cm), Overall: 18 x 19 1/2 x 10 1/2 in. (45.72 x 49.53 x 26.67 cm), Case (Glass presentation case): 17 1/8 x 18 x 9 1/8 in. (43.4975 x 45.72 x 23.1775 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Purchased with funds provided by Cary Grant by exchange (M.2004.33), photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Ludovico Lombardo, Bust of Lucius Junius Brutus, c. 1550, bronze, 30 × 27 × 11 in. (76.2 × 68.58 × 27.94 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of The Ahmanson Foundation (M.2005.60) photo © Museum Associates / LACMA

Unknown, Woman’s Dress, circa 1795, Cotton plain weave, Center back length: 65 in. (165.1 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Purchased with funds provided by Suzanne A. Saperstein and Michael and Ellen Michelson, with additional funding from the Costume Council, the Edgerton Foundation, Gail and Gerald Oppenheimer, Maureen H. Shapiro, Grace Tsao, and Lenore and Richard Wayne (M.2007.211.868)

Giovanni Baratta, Allegorical Figure of Wealth, from Palazzo Giugni, Florence, circa 1703-1708, White carrara marble, on later statuary marble pedestals set with panels and sections of green serpentine marble, Figure: 71 × 29 × 22 in. (180.34 × 73.66 × 55.88 cm), Base: 41 1/4 × 31 × 22 in. (104.78 × 78.74 × 55.88 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of The Ahmanson Foundation (M.2011.81.1), photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Portrait of a Gentleman, circa 1670-1675, Marble, a) Sculpture: 21 7/16 × 21 1/16 × 10 5/8 in. (54.5 × 53.5 × 27 cm), Base: 6 11/16 × 9 7/16 × 7 7/8 in. (17 × 24 × 20 cm), a-b) Overall: 28 × 22 × 13 in. (71.12 × 55.88 × 33.02 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of The Ahmanson Foundation in honor of the museum’s 50th anniversary (M.2015.4-b), photo © Museum Associates / LACMA

Giambologna, Flying Mercury, probably 1580s, Bronze, including base: 36 × 9 × 11 1/4 in. (91.44 × 22.86 × 28.58 cm), Promised gift of Lynda and Stewart Resnick in honor of the museum’s 50th anniversary (PG.2014.7.4)

Giovanni Baratta, Allegorical Figure of Prudence, from Palazzo Giugni, Florence, circa 1703-1708, White carrara marble, on later statuary marble pedestals set with panels and sections of green serpentine marble, Figure: 71 5/8 × 29 × 22 in. (181.93 × 73.66 × 55.88 cm), Base: 41 1/4 × 31 × 22 in. (104.78 × 78.74 × 55.88 cm), Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of The Ahmanson Foundation (M.2011.81.2), photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

About The Exhibition: To Rome and Back explores Rome as place, idea, and as a center of artistic patronage and production through three centuries. The exhibition follows the city from around 1500, when its classical structures and forms permeated art and architecture during the Renaissance, through the Counter-Reformation, when a resurgent Rome re-emerged as a powerhouse of patronage and artistic innovation, to the eve of the industrial age in the 18th century, when the city’s ancient glory seduced an increasingly mobile continent. Even at the height of its influence in the 17th century, Rome harbored deep contradictions—between ancient and novel, pagan and Christian, individualism and authority—and these tensions contribute to the dynamism of the city’s artistic legacy and its continued resonance.

The exhibition reveals Rome’s impact through seven thematic sections, which are organized in loose chronological order. The exhibition begins with a section entitled Meanings Of Rome. Reeling from the devastating one-two punch of the city’s spiritual collapse in the wake of the Protestant Reformation in 1517 as well as its physical sack in 1527, 16th-century Rome was a city piecing itself together. Despite these setbacks for the city itself, physical manifestations of the ancient empire, the characteristics that came to evoke “Rome”—both real and imagined—were already visible in cultural production occurring elsewhere in Italy. This section of the exhibition presents a selection of 16th-century Italian paintings, sculptures, and decorative arts that were produced outside of Rome but incorporate references or allusions to the ancient city. For example, at the entrance to the exhibition, Archangel Raphael, sculpted of wood and exquisitely painted, wears a uniform inspired by Roman military garb. In a large devotional picture of the Holy Family by Giorgio Vasari, the Virgin wears garments inspired by antique dress, while the ancient ruins at Tivoli are visible in the background. The vitrines at the center of the gallery include both ancient Roman glasswork and 16th-century examples that emulated ancient Roman techniques.

The practice of Identifying and Collecting objects and works of art associated with Rome is explored in the next section. During the 16th-century, the papacy and Roman aristocracy commissioned new masterworks by artists like Raphael and Michelangelo; images of these new monuments, as well as ancient ones, were circulated through prints and contributed to a growing interest in Roman history, art, and architecture. Ancient material, as well as tapestries, painting, sculpture, furniture, and other domestic objects referencing the classical world through technique, subject, or style, were widely collected in patrician homes and served to bolster the collector’s status and legitimacy. LACMA’s portrait of Marino Grimani, by the Venetian artist, Tintoretto, depicts one such collector, and while his powerful and wealthy family fought to reduce the influence of the Roman papacy in and around Venice, they assumed the heritage of ancient Rome as their own.

The following section, entitled A Roman Style, examines a powerful moment of stylistic innovation that emerged in Rome at the dawn of the 17th century, just as the city was benefiting from a reinvigorated papacy, and emphasized physical and emotional realism. Largely associated with the painter Caravaggio, its influence can be detected in pictures emphasizing the quiet drama of religious and humanist figures, or in the portrayal of everyday subjects. While the style’s popularity in Rome lasted only a few decades, it had a lasting impact on painting in Italy and beyond. More recently, the modern interest in realism has contributed to the popularity of this material in public collections, including LACMA’s.

The next section gathers painting, sculpture, decorative arts, and textiles around the theme of Inspiration and Awe. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Catholic Church and other patrons commissioned works of art designed to inspire audiences with their vibrant colors, drama, and theatricality, while new conceptions of time and space contributed to the adoption of illusionistic pictorial techniques. These stirring compositions and techniques are visible in religious works of art and objects, such as altarpiece paintings and ecclesiastical textiles, as well as domestic furniture and other decorative objects.

The works in the following gallery speak to the Classical Authority of Rome. As the city established itself as an increasingly powerful cultural and artistic center, it continued to attract artists from beyond Italy, who absorbed the city’s monuments, forms, and styles, then returned home or continued their travels to France, Belgium, Holland, Spain, and even New Spain. The concentrated and calculated use of mythological stories, antique models, and rhetorical and theatrical gesture flourished in 17th-century Rome, and these modes of art making came to signify institutional authority well beyond the borders of the Italian peninsula.

The next section explores a preference and Taste For The Antique among newly mobile Europeans, particularly young, British aristocrats on the “Grand Tour,” who arrived in Rome to complete their educations and establish their reputations. Such men of means, such as Sir Wyndham Knatchbull-Wyndham, whose portrait by Pompeo Batoni is featured in this section, commissioned portraits with references to popular classical motifs and recognizable antique sculpture, and collected antiquities as well as modern replicas of classical Rome. Their presence contributed to a growing market in decorative objects showcasing loosely classical themes, as well as the incorporation of ancient forms into contemporary dress.

Finally, A Sense Of Place includes objects produced as Rome’s power began to wane in the mid-1800s, in part due to the emergence of enlightenment thought. Many of these works of art, in their references to Rome’s monuments and ancient past, harbor an air of nostalgia that is new to these visions of place. Visitors commissioned or purchased prints, drawings, and small collectibles, as well as painting and sculpture that were produced for an increasingly globalized market. While many of these objects reference the Roman cityscape and countryside, their function is not simply documentary. Hubert Robert, for example, created a monumental and fanciful combination of 18th-century France and ancient Rome, while Piranesi circulated countless prints of actual sites alongside imagined ruins.

The exhibition’s thematic approach and its inclusion of spectacular works of art across many different media and curatorial departments will allow museum visitors to appreciate the myriad ways in which Rome inspired artists and patrons during a critical period in its history.

To Rome and Back: Individualism and Authority in Art, 1500–1800 #LACMA #Art Exhibition: To Rome and Back: Individualism and Authority in Art, 1500–1800 On view: June 24, 2018–March 17, 2019…

0 notes

Text

Thesauri

Abundantia: from Latin ăbundo ăbundans abundantis meaning “overflowing, abundant, plenty, riches” - Divine personification of abundance and prosperity.

Aphnology or Aphenology from Aplnios, Aphcnos, Afthnos, or Aphenos: Expresses wealth in the largest sense of general abundance and well-being. Rare the science of wealth.

Argentarius and Argentarii: Derived from argent(um) (“silver”) + -ārius (“dealer in”). Private individuals (or individuals of a private organization) that served as bankers (depositories), and money changers. Such individuals were members of a collegium, or guild. Many individuals entrusted all their capital to them. Individuals could deposit funds with a banker, and pay their debts using a draft or check from the bank. If both the debtor and creditor had an account with the same bank it was easy for the bank to internally transfer the funds between the accounts.

Bank Banco: In early Ancient Rome Money-lenders would set up their stalls in the middle of enclosed courtyards called macella on a long bench called a bancu.

Bancherius: [from Latin Bancum Banchus] In Genoa meant money changer, the name referring to the carpet covered table or bench at which the money changer conducted his business of exchanging foreign and domestic coins.

Chrematistics: [from Greek, from khrēmatizein to make money, from khrēma money] the art of getting rich, as coined by Thales of Miletus. The study of wealth, any theory of wealth as measured in money.“la gran crematística […] maximizar la riqueza y el dinero.“

Chrysology: [from Ancient Greek khrusós Gold] Rare the branch of political economy relating to the production of wealth. The study of the production of wealth, especially as attained from precious metals.

Copia: [From co- + ops, opis “power, ability, resources”] Roman Goddess of Abundance or Plenty.

Cornucopia: [from Latin cornu copiae Horn of Plenty] Symbol of abundance and nourishment, commonly a large horn-shaped container overflowing with produce, flowers or nuts. The horn of Amalthea, the goat that suckled Zeus. Attribute of several Greek and Roman deities, particularly those associated with the harvest, prosperity, or spiritual abundance, such as personifications of Earth (Gaia or Terra); the child Plutus, god of riches and son of the grain goddess Demeter; the nymph Maia; and Fortuna, the goddess of luck, who had the power to grant prosperity. In Roman Imperial cult, abstract Roman deities who fostered peace (pax Romana) and prosperity were also depicted with a cornucopia, including Abundantia, “Abundance” personified, and Annona, goddess of the grain supply to the city of Rome. Hades, the classical ruler of the underworld in the mystery religions, was a giver of agricultural, mineral and spiritual wealth, and in art often holds a cornucopia.

Denarius: [from the Latin dēnī "containing ten"] Origin of several modern words such as the currency name dinar; it is also the origin for the common noun for money in Italian denaro, in Slovene denar, in Portuguese dinheiro, and in Spanish dinero.

Dis Pater or Dis also Father Dis (The Wealthy One): [from dives], suggesting a meaning of “father of riches” or “Rich Father”. Originally a god of riches, fertile agricultural land, and underground mineral wealth, he was later commonly equated with the Roman deities Pluto and Orcus.

Economic development is the process by which a nation improves the economic, political, and social well-being of its people.

Economic mobility is the ability of an individual, family or some other group to improve (or lower) their economic status—usually measured in income.

Gentleman thief: A gentleman or lady thief usually has inherited wealth and is characterised by impeccable manners, charm, courteousness, and the avoidance of physical force or intimidation to steal. As such, they do not steal to gain material wealth but for the thrill of the act itself, often combined in fiction with correcting a moral wrong, selecting wealthy targets, or stealing only particular rare or challenging objects.

Goldsmith: Accepted jewellery and plate for safekeeping. They also accepted deposits of coin. Coins of the same nominal value varied greatly in weight, because many had been clipped or "sweated" to remove some of the gold. They sorted through the coins deposited with them for the ones nearest full weight. They then melted these down and exported them as Gold Bullion. Since this activity was quite profitable, they were happy to pay interest on deposits of coin. By 1660, the receipts that goldsmiths issued for deposits of coin had become transferrable, and they began to circulate informally as money. The goldsmiths took advantage of this and started to issue receipts with the express intention that they circulate.

Moneta: [from Latin monēre] which means to remind, warn, or instruct, or more likely from the Greek “moneres” meaning “alone, unique”.

Money changer: weighed, tested, sorted and exchanged foreign and domestic coins.

Money scrivener: Originally public letter writers and copyists, they evolved into legal practitioners who specialized in drawing up documents, including loan contracts. This work naturally led them into brokering loans, especially mortgages. As part of this business, clients would deposit money with them until they found a suitable investment

Nouveau poor: ["new poor"], refers to a person who had once owned considerable wealth, but has now lost all or most of it. These people may or may not actually be poor, but compared to their previous rank, it seems as if they are. Also Nouveau Pauvre.

Other People’s Money (OPM): A common expression used when talking about the multiplying effect of using borrowed funds to purchase property rather than paying all cash. Informal term for the use or investment of borrowed funds

Pecunia: [from pecū "cattle"] Flocks were the first riches of the ancients.

Pluto: Mythology The god of the dead and the ruler of the underworld, identified with the Greek Hades. Not only a god of the dead, he is identified as a god of the earth’s fertility, because he ruled the deep earth that contained the seeds necessary for a bountiful harvest. He was also called the God of Wealth due to the precious metals hidden in the earth. plutology Geology the study of the interior of the earth. / Latin, from Greek Ploutōn, literally: the rich one.

Plutus: [from Ploutos wealth:] from the belief that the underworld was the source of wealth from the ground.

Plouton: giver of wealth.

Plutology: [ploutologie “Science de la richesse”] Economics.the scientific study or theory of wealth; the branch of economics that studies wealth. Also called plutonomy Economics the study of economics or the production of wealth

Plutonomics: the study of wealth management.

Plutologist: Economics obsolete a person who has expertise in plutology

Political economy: Obsolete “In the late 19th century, the term economics gradually began to replace the term political economy.”

Temple of Juno Moneta: it was the place where Roman coins were first minted. Thus, moneta came to mean mint.

Thrift: Wise economy in the management of money and other resources.

Sources: Google Books, TheFreeDictionary.com, Wikipedia, Wiktionary.

0 notes