#arbëresh

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A young Arbëresh girl from Piana degli Albanesi, Italy, wearing a traditional Arbëresh costume, circa 1950.

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

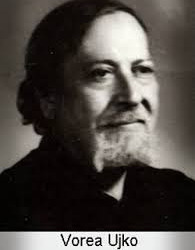

Domenico Bellizzi (1918–1989), also known under the pseudonym of Vorea Ujko, is among the most popular and respected of the Arbëresh poets.

Domenico Bellizzi was a modest priest from Frascineto in Calabria who taught modern literature in Firmo.

Bellizzi died in a car accident in January 1989.

Bellizzi's verse, a refined lyric expression of Arbëresh being, has appeared in many periodicals and anthologies and in seven collections, four of which were published in Italy, two in Albania and one in Kosovo.

Bellizzi is a poet of rich tradition. He is the worthy heir of the great nineteenth-century Arbëresh poets Girolamo De Rada (1814-1903) and Giuseppe Serembe (1844-1901), whom he admired very much.

His verse is intimately linked with the Arbëresh experience, imbued with the gjaku i shprishur (the scattered blood). Though devoid of the lingering sentiments of romantic nationalism so common in Albanian verse, and the standard motifs of exile lyrics, Bellizzi's poetry does not fail to evince the strength of his attachment to the culture of his Balkan ancestors despite five hundred years in the dheu i huaj (foreign land).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

La chiesa del Santissimo Salvatore o S. Omobono a Cosenza, 26 novembre 2023

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Note

Related to The Land Before time

My aunt lived in Brazil when she gave birth, and then moved back to Italy pretty fast to get help with the baby from her family. But she didn't want the child not to grow up speaking Portuguese, but her family was Albanian Italian, so they spoke Arbëresh at home, and outside everyone spoke Italian.

So the solution was making the child watch tv in Portuguese when dvds had the option. And one of the main dvds that could be seen in Portuguese was the first Last Before Time.

So I, the baby's cousin and, by virtue of being two years older, much more aware of my surroundings, spent my childhood watching The Land Before Time in Portuguese.

Neither me or my cousin can understand Portuguese more than any Italian speaker can. It was all for nothing in the end.

HJDSKAGHKDJSGH????

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prende

Prende or Premte is the goddess of dawn, love, beauty, fertility, health and protector of women, in the Albanian pagan mythology. She is also called Afër-dita, an Albanian phrase meaning "near day", "the day is near", or "dawn", in association with the cult of the planet Venus, the morning and evening star. Her sacred day is Friday, named in Albanian after her: e premte, premtja (Gheg Albanian: e prende, prendja). In Albanian mythology Prende appears as the daughter of Zojz, the Albanian sky and lighning god.

Thought to have been worshiped by the Illyrians in antiquity, Prende is identified with the cult of Venus and she was worshipped in northern Albania, especially by the Albanian women, until recent times. Originally a pre-Christian deity, she was called "Saint Veneranda" (ShënePremte or Shën Prende), identified by the Catholic Church as Saint Anne, mother of Virgin Mary. She was so popular in Albania that over one in eight of the Catholic churches existing in the late 16th and the early 17th centuries were named after her. Many other historical Catholic and Orthodox churches were dedicated to her in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Dialectal variants include: Gheg Albanian P(ë)rende (def. P(ë)renda), Pren(n)e (def. Pren(n)a); Tosk Albanian: Premte (def. Premtja), Preme (def. Prema).

Prende is also called Afërdita (Afêrdita in Gheg Albanian) in association with the cult of the planet Venus, the morning and evening star, which in Albanian is referred to as (h)ylli i dritës, Afërdita "the Star of Light, Afërdita" (i.e. Venus, the morning star) and (h)ylli i mbrëmjes, Afërdita (i.e. Venus, the evening star). Afër-dita, an Albanian phrase meaning "near day", "the day is near", or "dawn", is the native Albanian name of the planet Venus. Afro-dita is its Albanian imperative form meaning "come forth the day/dawn".

The Albanian translation of "evening" is also rendered as πρέμε premë in the Albanian-Greek dictionary of Marko Boçari.

In northern Albania, Prende is referred to as Zoja Prenne or Zoja e Bukuris "Goddess/Lady Prenne" or "Goddess/Lady of Beauty".

The Albanian name Premtë or P(ë)rende is thought to correspond regularly to the Ancient Greek counterpart Περσεφάττα (Persephatta), a variant of Περσεφόνη (Persephone). The theonyms have been traced back to the Indo-European *pers-é-bʰ(h₂)n̥t-ih₂ ("she who brings the light through").

The Albanian phrase afro dita 'come forth the day/dawn' traces back to Proto-Albanian *apro dītā 'come forth brightness of the day/dawn', from Indo-European *h₂epero déh₂itis. The theonym Aprodita is attested in Messapic inscriptions in Apulia.

In the Albanian pagan mythology Prende is the goddess of dawn, love, beauty, fertility and health. She is considered the Albanian equivalent of the Roman Venus, Norse Freyja and Greek Aphrodite.

According to some Albanian traditions, Prende is the daughter of Zojz, the Albanian sky and lightning god. Associated with the dawn goddess, the epithet "daughter of the sky-god" is commonly found in Indo-European traditions.

According to folk beliefs, swallows, called Pulat e Zojës "the Lady's Birds", pull Prende across the sky in her chariot. Swallows are connected to the chariot by the rainbow (Ylberi), which the people also call Brezi or Shoka e Zojës "the Lady's Belt".

The common Albanian name nepërkë for the venomous snake adder, viper appears in the Arbëresh variety of Calabria as nepromtja, probably based on Prende / Premte.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

NASCE IL FESTIVAL PER SALVARE LE MINORANZE LINGUISTICHE IN ITALIA

In Italia esistono 12 minoranze linguistiche riconosciute e tutelate dalla legge, comunità storiche parlanti idiomi ascritti a varie famiglie linguistiche che vivono nel territorio del nostro Paese. Queste realtà hanno una forte identità e tradizioni spesso antiche che conservano e tramandano al di fuori di confini dei Paesi da cui sono provenute, a volte uniche superstiti di culture che si stanno perdendo. Per salvare questi scrigni di storia è nato in Basilicata ‘Il borgo dei suoni’ un progetto che a San Costantino Albanese, un piccolo Comune in provincia di Potenza, sta recuperando cultura e folklore di tante comunità linguistiche a rischio di scomparsa.

Tutto è iniziato intorno a una comunità arbëreshe (albanesi d’Italia) sorta a metà Cinquecento da un insediamento di popolazioni albanesi in fuga dall’invasione ottomana che conserva tratti ed elementi fondamentali della cultura di provenienza ma che, allo stesso tempo, si è rivelata ricettiva e sensibile alle influenze dell’area circostante da risultare anche un’espressione specifica della cultura della Val Sarmento. Qui è nato ad agosto 2024 il primo festival delle minoranze linguistiche, un incontro di gruppi da tutta Italia e un programma di iniziative che prevede, tra le altre, una scuola internazionale di etnografia audiovisuale realizzata con l’Università di Milano, la realizzazione di un archivio sonoro, incontri culturali, concorsi per le scuole e molta musica e canti tradizionali. Minoranze delle popolazioni albanesi, catalane, germaniche, greche, slovene e croate e di quelle parlanti il francese, il franco-provenzale, il friulano, il ladino, l’occitano e il sardo condividono le proprie radici.

___________________

Fonte: Regione Basilicata; Diffusioni musicali; foto di Wojciech Pedzich

VERIFICATO ALLA FONTE | Guarda il protocollo di Fact checking delle notizie di Mezzopieno

BUONE NOTIZIE CAMBIANO IL MONDO | Firma la petizione per avere più informazione positiva in giornali e telegiornali

Se trovi utile il nostro lavoro e credi nel principio del giornalismo costruttivo non-profit | sostieni Mezzopieno

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Bukurìa arbëreshe' by Italian Angelo Crazyone (@angelocrazyone) for iArtfivas 2023 in Piana degli Albanesi, Italy #angelocrazyone #streetart #lamolinastreetart | photo via artist mysl.nl/XbObC

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

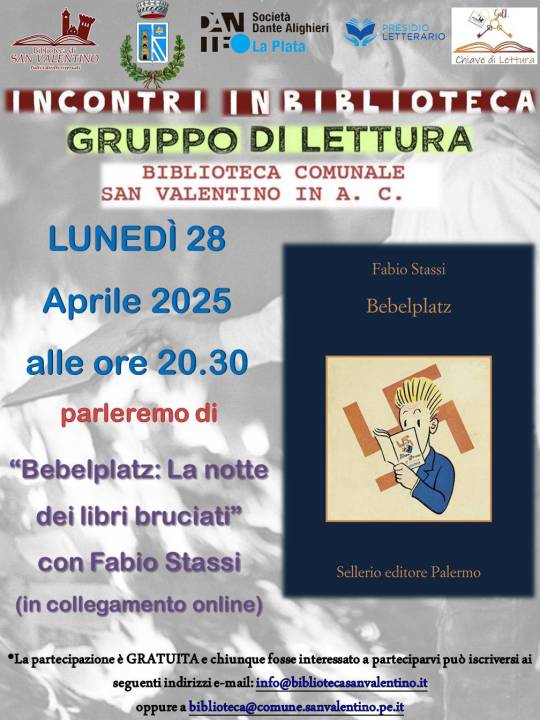

Lunedì 28 Aprile 2025 alle ore 20.30 il GdL "Chiave di Lettura", presso i locali della Biblioteca San Valentino, si incontrerà, per discutere insieme del libro “Bebelplatz. La notte dei libri bruciati”, con l’autore Fabio Stassi, che sarà in collegamento online.

10 maggio 1933. A Bebelplatz, nel centro di Berlino, allo scoccare della mezzanotte migliaia di libri vengono dati alle fiamme. Joseph Goebbels proclama: «L’uomo tedesco del futuro non sarà più un uomo fatto di libri, ma un uomo di carattere». Su tutta l’Europa si sparge un odore di benzina e di cenere.

24 febbraio 2022. La Russia invade l’Ucraina, e di lì a qualche mese un nuovo conflitto devasterà la striscia di Gaza. Durante un tour negli istituti di cultura italiani da Amburgo a Monaco, Fabio Stassi attraversa le piazze delle Bücherverbrennungen, i roghi di libri, e risale a ritmo incalzante la memoria del fuoco e delle censure, dei primi bombardamenti aerei sui civili, del saccheggio di librerie e biblioteche. Studia mappe e resoconti, si interroga sul ruolo della cultura e sulla cecità della guerra, indaga l’istinto di sopraffazione degli esseri umani. Alla fine compone un piccolo atlante della letteratura «dannosa e indesiderata» e rintraccia cinque scrittori italiani destinati alle fiamme dai nazisti: Pietro Aretino, il cantore della libertà rinascimentale; Giuseppe Antonio Borgese, cittadino del mondo e inguaribile utopista; Emilio Salgari, antimperialista amato in Sudamerica; Ignazio Silone, antifascista radicale, e Maria Volpi, unica donna della lista, disinibita narratrice del piacere e dell’indipendenza femminile.

Quello di Stassi è un appassionato discorso in difesa di tutto ciò che trasgredisce la norma, un viaggio ricco di corrispondenze, colpi di scena e nuove interpretazioni, da Ovidio a Cervantes, da Arendt a Canetti, Sebald, Morante, Bernhard: un invito a disseppellire la biblioteca di Don Chisciotte. Perché la ribellione si impara leggendo, e ogni lettore, per qualsiasi potere, «è sempre una minaccia».

Fabio Stassi (1962) è uno scrittore e paroliere italiano di etnia arbëresh. È bibliotecario presso la Biblioteca di Studi Orientali della Sapienza. Ha scritto i suoi libri viaggiando in treno fra Viterbo, Orte e Roma. Ha esordito con “Fumisteria” con cui ha vinto il "Premio Vittorini opera prima 2007". A fine ottobre del 2012 esce per Sellerio “L'ultimo ballo di Charlot”. Il romanzo, ancora prima di essere pubblicato, diventa un caso editoriale al Salone del Libro di Francoforte, gli editori stranieri ne acquistano i diritti e verrà tradotto in diciannove lingue. L'anno dopo, il libro vince il Premio Selezione Campiello 2013 e ottiene molti altri prestigiosi riconoscimenti. Collabora con vari quotidiani e riviste e nel 2024 gli viene assegnato il Premio Hermann Kesten dal Pen Deutschland per la difesa della libertà di parola.

Se volete partecipare, contattateci all'indirizzo mail: [email protected] oppure all'indirizzo, sempre mail, [email protected] e riceverete, in prossimità dell’incontro, il link di riferimento.

Vi aspettiamo per conoscere e confrontarci con l’autore, non mancate!!!

#gdl#gruppolettura#gruppodilettura#gruppodiletturachiavedilettura#gdlchiavedilettura#gdlbibliosanvale#chiavedilettura#lunedìsera#lunedìletterario#incontriinbiblioteca#confrontarsisuilibri#bebelplatz#lanottedeilibribruciati#sempredilunedìsera#fabiostassi#diariodiviaggio#societàdantealighieri#laplata#presidioletterario#bibliotecacomunale#bibliosanvale#passioneperilibri#condividereletture#condivisionelibri#10maggio1933#potenzadeilibri#bibliotecasanvalentino#biblioteca#bibliosanvalentino#libri

0 notes

Text

A ishte Frank Sinatra Shqiptarë ?

Babai i Frank Sinatra, Antonino Martino Sinatra, ishte nga Lercara Friddi, një qytet në provincën e Palermos, Siçili, Itali. Lercara Friddi ka lidhje historike me komunitetin arbëresh (shqiptar) në Siçili. Ndonëse nuk është një nga vendbanimet më të njohura arbëreshe, disa arbëreshë u vendosën në këtë zonë. Siçilia ka disa fshatra arbëreshe, kryesisht në provincat e Palermos, Katanias, Mesinës…

0 notes

Text

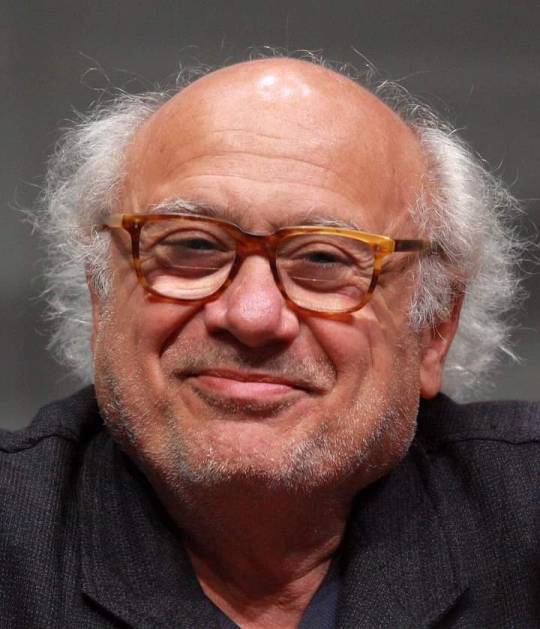

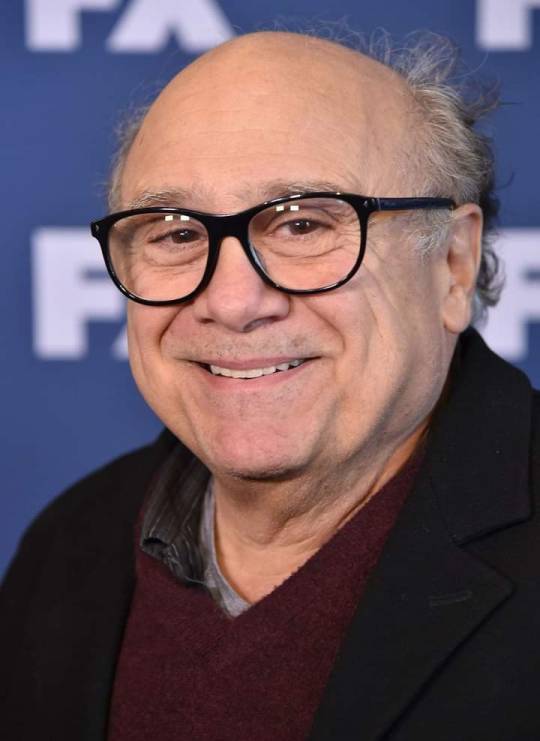

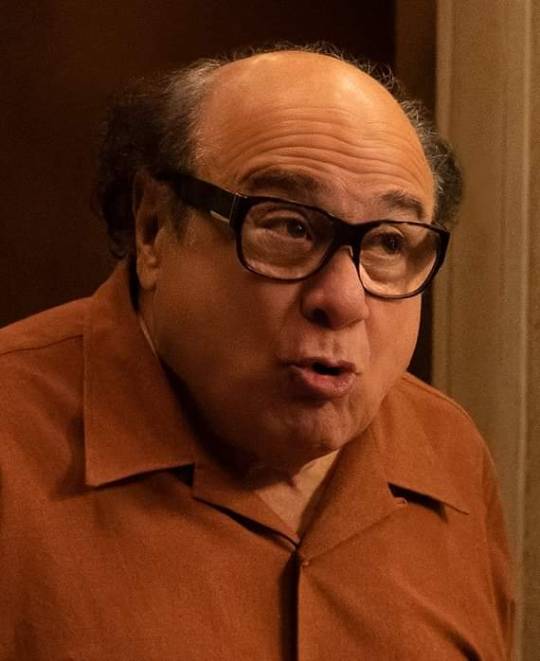

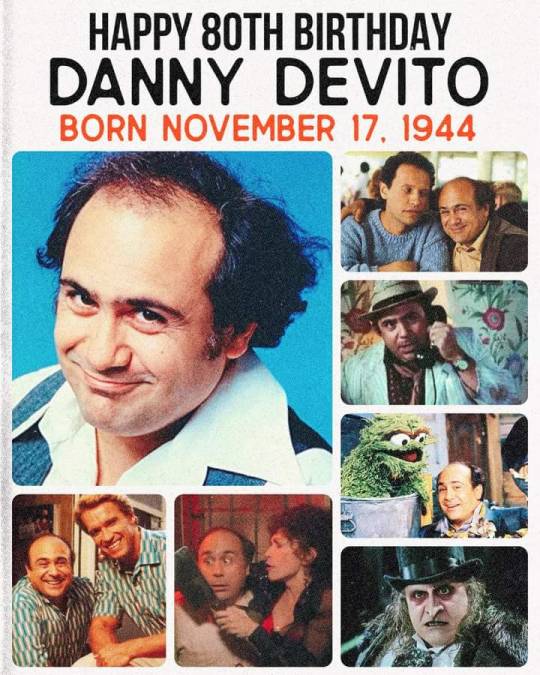

Happy Birthday 🎂 🥳 🎉 🎈 🎁 🎊 🎂 To You

The Legendary & Iconic Funniest Short 🤣 Man On 👨 👴Earth 🌎 & Actor Of All Times

Born On November 17th, 1944

He is an American actor and filmmaker. He gained prominence for his portrayal of the taxi dispatcher Louie De Palma in the television series Taxi (1978–1983), which won him a Golden Globe Award and an Emmy Award. He plays Frank Reynolds on the FXX sitcom It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia (2005–present).

DeVito was born at Raleigh Fitkin-Paul Morgan Memorial Hospital in Neptune Township, New Jersey, the son of Daniel DeVito Sr., a small business owner, and Julia DeVito (née Moccello). He grew up in a family of five, with his parents and two older sisters. He is of Italo-Albanian descent; his family is originally from San Fele, Basilicata, as well as from the Arbëresh Albanian community of Calabria.

He is known for his film roles in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975), Terms of Endearment (1983), Head Office (1985), Ruthless People (1986), Throw Momma from the Train (1987), Twins (1988), The War of the Roses (1989), Batman Returns (1992), Jack the Bear (1993), Junior (1994), Matilda (1996), L.A. Confidential (1997), The Big Kahuna (1999), Big Fish (2003), Deck the Halls (2006), When in Rome (2010), Wiener-Dog (2016), and Jumanji: The Next Level (2019). He has voiced roles in such films as Hercules (1997), The Lorax (2012), and Smallfoot (2018).

PLEASE WISH THIS LEGENDARY ICONIC SMALL BUT LIVING LARGE HUMOROUS ACTOR OF ALL TIMES

A VERY HAPPY BIRTHDAY 🎂 🥳 🎉 🎈 🎁 🎊

YOU ALL KNOW HIM, BOTH YOUNG & OLD

EVERYONE LOVES HIS ACTING 👋 FOR MANY YEARS

& HIS ICONIC HUMOR IS 🤣 ALWAYS A DELIGHT TO HAVE AROUND

THE 1 & ONLY

MR. DANIEL MICHAEL DEVITO JR. 👴

HAPPY 80TH BIRTHDAY 🎂 🥳 🎉 🎈 🎁 🎊 TO YOU MR. DEVITO 👴 & HERE'S TO MANY MORE YEARS TO COME

#DannyDevito

1 note

·

View note

Text

59) Albania (CD)

Szkodra. Flaga podzielona pionowo

2. Wcześniejsza flaga Szkodry. Gmina Szkodra (wł. Scutari; tur. Uskudar; crng. Skadar; 86 200 mieszkańców w 2008 r.) jest ekonomiczną stolicą północnej Albanii i czwartym co do wielkości miastem w kraju. Szkodra znajduje się w najbardziej wysuniętym na południowy wschód punkcie Jeziora Szkoderskiego, największego jeziora na Bałkanach, dzielonego z Czarnogórą (169 km kw. w Albanii; 199 km kw. w Czarnogórze). Szkodra była w III wieku p.n.e. stolicą iliryjskiego plemienia Ardejczyków, którego ostatni król, Genthius, bił własne monety. Genthius zawarł sojusz z macedońskim królem Perseuszem (179-168 p.n.e.) i został pokonany w 168 r. p.n.e. podczas trzeciej wojny iliryjskiej przez generała Lucjusza Emiliusza Paulusa (228-160 p.n.e.). Tytus Liwiusz donosi, że stolica Genthiusa była chroniona murami, wieżami i twierdzami. Zdobyta i splądrowana przez Rzymian, Szkodra została później odbudowana i stała się centrum prowincji Praevalitania. W wyniku podziału Cesarstwa Rzymskiego w 395 r. Szkodra została przydzielona do Cesarstwa Wschodniego (Cesarstwa Bizantyjskiego). W XI wieku została przekazana serbskim władcom z Zeta (dzisiejsza Czarnogóra), którzy rozwinęli gospodarkę miasta. Szkodra została następnie przekazana albańskiej rodzinie Balshaj, władcom całej północnej Albanii i części Czarnogóry. Zagrożeni przez Osmanów, Balshaj sprzedali miasto Wenecjanom w 1396 r.; Szkodra stała się wysuniętą placówką chrześcijaństwa. Miasto zostało zajęte w 1474 i 1478 r. przez Osmanów, którzy nie mogli go utrzymać. Ostatecznie zdobyli je i splądrowali w 1479 r. po rocznym oblężeniu przedstawionym na słynnym obrazie Paolo Veronese (1528-1588). Upadek Szkodry spowodował wygnanie kilku jego mieszkańców do Włoch, gdzie utworzyli społeczności Arbëresh/Arbaresh w Kalabrii, Sycylii i gdzie indziej. Pod rządami Imperium Osmańskiego, Szkodra odrodziła się w XVII-XVIII wieku; w tym czasie (1767-1773) zbudowano Meczet Ołowiany, pokryty liśćmi ołowianymi. W 1756 r. Mehmed Pasza Plaku założył w Szkodrze, dynastię Bushati, która ustanowiła własne rządy i nawiązała stosunki dyplomatyczne z innymi państwami europejskimi. Za Kara Mamouda Paszy Bushatiego, Szkodra miała 70 000 mieszkańców i słynęła ze swoich rzemieślników. W 1831 roku sułtan zorganizował wyprawę wojskową, aby pozbyć się rządów Bushati. Podczas albańskiego odrodzenia narodowego (Rilindja) w Szkodrze wybuchały powstania przeciwko Turkom w latach 1876, 1880, 1910, 1911 i 1912. Serbowie i Czarnogórcy oblegali miasto podczas wojen bałkańskich, ale bezskutecznie. Podczas I wojny światowej, Szkodra znalazła się pod międzynarodową administracją, następnie była okupowana przez Austriaków, następnie przez Francuzów (1918-1920), a ostatecznie została włączona do nowego państwa albańskiego. W 1990 roku Szkodra była jednym z głównych i najwcześniejszych ośrodków buntu, który spowodował upadek reżimu komunistycznego w Albanii.

Twierdza Rozafa została zbudowana na wzgórzu dominującym nad zbiegiem rzek Buna i Kiri; ma owalny kształt, obwód 600 m i powierzchnię 6 ha. Twierdza i jej siedem wież zostały kolejno przebudowane przez Wenecjan i Osmanów na fundamentach wczesnoiliryjskiej twierdzy. Budowa twierdzy jest związana z legendą Rozafy. Trzej bracia odpowiedzialni za budowę zauważyli, że ich codzienna praca zawsze była niszczona następnej nocy; pewien starzec doradził im, aby zamurowali kogoś żywcem, aby uspokoić demony, które niszczyły ich pracę. Bracia postanowili poświęcić pierwszą ze swoich żon, która miała przyjść następnego dnia, aby przynieść im lunch. Dwóch najstarszych braci ostrzegło swoje żony, a Rozafa, żona młodszego syna, została poświęcona. Przyjęła to, ale poprosiła, aby w murze zrobiono małą szparę, aby mogła karmić piersią swojego młodego syna. Fontanna Rozafy, a właściwie przesiąkająca woda wapienna, nadal jest widoczna w murze bramy wejściowej twierdzy. Jest to miejsce pielgrzymek dla kobiet w ciąży. Ten rodzaj legendy, rozpowszechniony na Bałkanach, został zilustrowany przez znanych pisarzy, takich jak Ismail Kadare (Trzy łukowe mosty) i Ivo Andrić (Most nad Driną).

Ze względu na swoje położenie geograficzne i kontakty z zagranicą Szkodra zawsze była głównym ośrodkiem kultury albańskiej, szczególnie przed założeniem państwa albańskiego. Historyk Marin Barleti (zm. 1512) mieszkał w Szkodrze podczas trzech oblężeń przez Osmanów; po klęsce przeniósł się do Włoch, gdzie opublikował po łacinie De obsidione Scodrensis (Oblężenie Szkodry, Wenecja, 1504) i Historia de vita et gestis Skanderbegi (Historia życia i czynów Skanderbega, Rzym, 1508). Ta ostatnia książka została przetłumaczona i rozpowszechniona w całej Europie i znacząco przyczyniła się do sławy Skanderbega. Gjon Buzuk, pisarz z północnej Albanii o niemal całkowicie nieznanej biografii, opublikował w 1555 r. w Wenecji Meshar (Mszał), serię kazań wygłoszonych na podstawie Ewangelii. Ta 188-stronicowa książka jest najstarszą znaną książką opublikowaną w języku albańskim. Powieściopisarz Ernst Qoliki (1903-1975), urodzony w Szkodrze, studiował we Włoszech i wrócił do Albanii po utworzeniu rządu regencyjnego w 1920 r. Po zamachu stanu Zogu w 1924 r. Qoliki został zesłany do Jugosławii wraz z przywódcami albańskich plemion górskich. Wrócił do Albanii w 1930 r., ale został ponownie zesłany do Włoch w 1933 r. Qoliki przyczynił się do popularyzacji albańskiej kultury i literatury we Włoszech i został mianowany profesorem języka albańskiego na Uniwersytecie w Rzymie. Przyjął mussolińskie poglądy ekspansjonistyczne i został mianowany ministrem edukacji Albanii podczas włoskiej okupacji (1939-1941). W 1943 r. przewodniczył Wielkiej Radzie Faszystowskiej w Tiranie. Po zwycięstwie komunistów uciekł do Włoch, gdzie spędził resztę życia. Najsłynniejszym pisarzem ze Szkodry jest poeta i powieściopisarz Migjeni (Milosh Gjegj Nikolla, 1911-1938). Urodzony w rodzinie prawosławnej, studiował w Barze (Czarnogóra) i Bitoli (Macedonia). Wrócił do Szkodry w 1932 r. i został nauczycielem szkolnym. Zmarł na gruźlicę we włoskim sanatorium 26 sierpnia 1938 r. Jedyny tom wierszy Migjeniego, Vargjet e lira (Wiersze wolne), powstał w ciągu trzech lat od 1933 do 1935 r. Pierwsze wydanie tej smukłej, a jednak rewolucyjnej kolekcji, w sumie trzydziestu pięciu wierszy, zostało wydrukowane przez wydawnictwo Gutemberg Press w Tiranie w 1936 r., ale zostało natychmiast zakazane przez władze i nigdy nie trafiło do obiegu. Drugie wydanie ukazało się dopiero w 1944 r. Głównym tematem Wolnych wierszy i prozy Migjeniego jest nędza i cierpienie. Chociaż nie opublikował ani jednej książki za swojego życia, dzieła Migjeniego, które krążyły prywatnie i w prasie tamtego okresu, odniosły natychmiastowy sukces. Migjeni utorował drogę nowoczesnej literaturze w Albanii. Jego seria opowiadań zatytułowana Tregimet nga qyteti i Veriut (Kroniki miasta północnego) daje żywy opis Szkodry pod feudalnym reżimem Zogu, kładąc nacisk na prostytucję, coś, co było wówczas całkowitym tabu w Albanii. Flaga Szkodry, używana poziomo lub pionowo, jest podzielona na niebiesko-białe z herbem miejskim pośrodku

3. Flaga kibiców Vllaznia Shkodër. KF Vllaznia Shkodër został założony w 1919 roku jako Bashkimi Shkodran, pierwszy klub piłkarski w historii Albanii. Klub wygrał dziewięć razy Albańską Ligę i sześć razy Albański Puchar. Kibice klubu używali różnych kombinacji barw klubu, czerwonego i niebieskiego, które są również barwami miasta. Poziomo podzielona na czerwono-niebiesko-czerwony

4. Flaga kibiców Vllaznia Shkodër. j. w. Pionowo podzielona na czerwono-niebieski

5. Flaga kibiców Vllaznia Shkodër. j. w. Podzielona poziomo niebiesko-czerwony-niebieski-czerwony-niebieski-czerwony

6. Flaga Fushë-Arrëz. Niebieska z herbem gminy w środku

7. Flaga Malësi e Madhe. Podzielona pionowo na niebiesko-zielone paski, a pośrodku znajduje się herb gminy

8. Flaga Pukë. Podzielona pionowo na kolory czerwony i zielony, a pośrodku znajduje się herb gminy

9. Flaga powiatu Tirana. Niebieski z herbem hrabstwa w środku

10. Flaga Tirany. Niebieska z herbem miejskim w środku

11. Kam. Nowa flaga

12. Kam. Stara flaga

13. Flaga Kavajë. Gmina Kavajë (82 835 mieszkańców w 2011 r.; 19 881 ha) znajduje się 25 km na południe od Durrës. Gmina została utworzona w 2015 r. w wyniku połączenia byłych gmin Kavajë, Golem, Helmas, Luz i Vogël oraz Synej. Flaga Kavajë jest niebieska z herbem gminy w centrum. Na herbie znajduje się wieża zegarowa Kavajë, uważana za najwyższą w Albanii, wzniesiona obok meczetu Kubelie

14. Flaga Vorë. Niebieska z herbem gminy w środku [1]

15. Flaga Vorë. Niebieska z herbem gminy w środku [2]

16. Flaga powiatu Vlorë. Biała z herbem powiatu w środku. „Quarku” oznacza „powiat”

17. Flaga Wlory. Niebieska z herbem miejskim pośrodku. Posąg przedstawiony na godle jest górną częścią Pomnika Niepodległości Wlory, wspólnego dzieła rzeźbiarzy Kristaqa Ramy, Shabana Haderiego i Muntaza Dhramiego. Pomnik, poświęcony w 1972 r. z okazji 60. rocznicy wydarzeń, ma 17 m wysokości. Niepodległość Albanii została proklamowana we Wlorze 28 listopada 1912 r. (rok jest wyryty na pomniku), kiedy grupa 83 patriotów pod wodzą Ismaila Qemala (przedstawionego przed pomnikiem) podniosła flagę narodową

18. Flaga kibiców Flamurtari Vlorë. KS Flamurtari Vlorë zostało założone 23 marca 1923 roku jako Shoqeria Sportive Vlorë. W 1935 roku klub przemianowano na Shoqata Sportive Ismail Qemali, a 22 czerwca 1946 roku na Klubi Sportiv Flamurtari Vlorë. Klub wygrał Albańską Ligę w 1991 roku i Puchar Albanii w 1985, 1988 i 2009 roku. Pozostał sławny dzięki w Pucharze UEFA w latach 80., przegrywając z FC Barcelona w 1986 r. (1:1 u siebie; 0:0 na wyjeździe) i eliminując w kolejnym sezonie Partizan Belgrad (2:0 u siebie; 1:2 na wyjeździe) i Wismut Aue (0-1 na wyjeździe; 2-0 u siebie), ostatecznie pokonane w trzeciej rundzie przez FC Barcelona (1-4 na wyjeździe; 1-0 u siebie). Kibice Flamurtari Vlorë używają czerwonej flagi z trzema pionowymi czarnymi pasami, podobne do koszulki zawodników. Czerwony i czarny to kolory flagi albańskiej (flamur), przypominające, że Ismail Qemal proklamował niepodległość Albanii we Wlorze, znanej od tamtej pory jako „Miasto Flagi”

19. Flaga Finiq. Gmina Finiq (11 862 mieszkańców w 2011 r.; 44 120 ha) położona jest 130 km na południowy wschód od Wlory i 15 km na północny wschód od Sarandy. Gmina została utworzona w 2015 r. z połączenia byłych gmin Finiq, Aliko, Dhivër, Livadhja i Mezopotam. Finiq, położona w północnym Epirze, 20 km na północ od granicy greckiej, jest zamieszkana głównie przez etnicznych Greków. Flaga jest biała z herbem gminy w centrum. „BASKIA” / „Δημος” oznacza „Gmina”. Na godle znajduje się teatr starożytnego miasta Fenice (Phoenike / Foinike). Fenike odgrywało strategiczną rolę z punktu widzenia administracyjnego i politycznego w regionie Epiru, dzięki swojemu położeniu geograficznemu i rozwojowi gospodarczemu, początkowo jako centrum Chaonii, a następnie jako stolica Federacji Epiru (w latach 230-168 p.n.e.), państwa federalnego utworzonego przez unię terytoriów Epiru i niektórych z najważniejszych sąsiednich regionów (Chaonii, Tesprotii i Molosów). Polibiusz (200-118 p.n.e.) nazwał Fenike miastem o najsilniejszych murach obronnych w całym Epirze. Świadczą o tym również odkrycia archeologiczne, które uwypukliły system fortyfikacji i zabytki reprezentujące wszystkie fazy historyczne miasta. Liwiusz wspomniał o pokoju fenickim, który zakończył pierwszą wojnę macedońską (214-205 p.n.e.). W III wieku p.n.e. Fenike osiągnęła szczyt swojego rozwoju politycznego, administracyjnego i architektonicznego. W okresie rzymskim rola Fenicjów zmalała, ale teatr został przebudowany, a w centralnej części miasta zbudowano obiekt publiczny (jego wielkość i zasięg są nadal niejasne), a także zbiorniki na wodę. Jednym z najważniejszych zabytków późnej starożytności w Fenicjach jest wczesnochrześcijańska bazylika z trzema nawami i atrium z przodu (V-VI w.). Teatr jest punktem orientacyjnym starożytnego miasta Fenicjów, odzwierciedlającym okres hellenistyczny i rzymski. Jego bardzo duże wymiary (scenee frons mierzą ponad 30 m długości) świadczą o znaczeniu miasta jako stolicy politycznej. Orkiestra zajmuje duży sztuczny taras na zachodnim zboczu wzgórza. Cavea jest całkowicie osadzona w naturalnym terenie, który tworzy półkolistą belkę, idealną do budowy miejsc siedzących. Teatr był wykorzystywany do występów i prawdopodobnie do spotkań politycznych Federacji Epirote. Teatr powstał na podstawie struktur architektonicznych i materiałów archeologicznych, składających się z ceramiki pokrytej czarną glazurą i dzieł sztuki zdobiących scenę. Powstał w połowie III wieku p.n.e., a drugi okres budowy miał miejsce w II wieku p.n.e. Teatr został przebudowany w okresie rzymskim (III wiek). Zabytek został po raz pierwszy wykopany w 2000 r. przez albańsko-włoską misję kierowaną przez Shpresę Gjongecaja (Instytut Archeologiczny w Tiranie) i Sandro De Marię (Uniwersytet Boloński)

20. Flaga Sarandy. Niebieska, a herb miasta znajduje się pośrodku

0 notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

I knew they would do well because it's as close as these duo gets to carrying the Arbëresh soul, considering their background and all. And Arbëresh music is fire. Pun intended, but also coincidentally the imagery of the song is dark and light/fire like a pagan Ilyrian dance especially towards the end.

Albania please vote zjerm for Eurovision

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The major linguistic groups of Albanians. The Arbëresh of Italy are Tosks, generally.

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

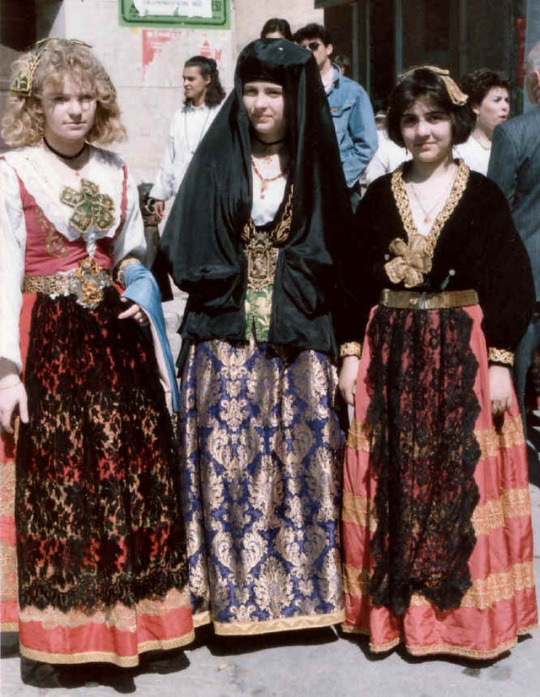

Women in Albanian dress - Piana degli Albanesi, Sicily, Italy.

284 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drangue

The drangùe (definite Albanian form: drangùa, drangòni) is a semi-human winged divine hero in Albanian mythology and folklore, associated with weather and storms. Babies destined to become drangue are born with their heads covered in caul and with two or sometimes four wings under their arms. The drangue hold supernatural powers, especially in the wings and arms. He is made invulnerable by the singular conjunction produced at his birth, and can die only if this conjunction is repeated once again. The main goal of the drangue is to fight the kulshedra in legendary battles. He uses meteoric stones, lightning-swords, thunderbolts, piles of trees and rocks to defeat the kulshedra and to protect mankind from storms, fire, floods and other natural disasters caused by her destructive power. Heavy thunderstorms are thought to be the result of their battles. The drangue and their myth are extensively and accurately portrayed in the Albanian folk tale "The Boy who was Brother to the Drague".

Standard Albanian form of the name is dragùa. A common dialectal variant is drangue. Durham recorded the form drangoni.

The Albanian term drangùe/dragùa is related to drangë, drëngë, drëngëzë, "a small fresh-water fish that does not grow very big", and to Gheg Albanian drãng, "kitten, puppy, cub", generally used for a "wild baby animal", most likely related to the singular birth conditions of this mythological figure. In Albanian tradition, there are two semantic features of the term dragùa. Some of the earliest Albanian works includes the term dragùa to describe a dragon or hydra-like monster, such as found in Roman mythology and in Balkan folklore. With the same meaning other old sources use instead the term kulshedra. The other semantic sense of the term dragùa, which is widespread in collective Albanian beliefs, is that of a hero battling the Kulshedra, a mythological tradition already attested in the 17th century Albanian texts, such as the 1635 Dictionarium Latino-Epiroticum by Frang Bardhi. The term drangue is also used in some Albanian dialects (including also the Arbëresh) with the meaning of "lion" and "noble animal".

The legendary battle of a heroic deity associated with thunder and weather, like drangue, who fights and slays a huge multi-headed serpent associated with water and storms, like kulshedra, has been preserved from a common motif of Indo-European mythology. Similar characters with different names but same motifs representing the dichotomy of "good and evil" – mainly reflected by the protection of the community from storms – are found also in the folklore of other Balkan peoples.

Babies destined to become dragùa are born "wearing shirts" and qeleshes, with two or four wings under their arms. This notion that the predestined hero are born "in a chemise" does not refer to them literally wearing articles of clothing; rather, these are babies born with their heads covered in caul, or amniotic membrane.

In some regions (such as Celza parish), it is said that dragùa babies are only born to parents whose lineage have not committed adultery for three generations, or from mothers who were kulshedras.

The drangues are semi-human warriors with extraordinary strength, giving them the ability to tear trees out of the ground and throw large boulders at their enemies. They can also cast lightning bolts and meteors, or whole houses.

The wings and arms of a dragùa are thought to be the source of his power and if their bodies are dissected, a golden heart with a jewel in the middle of it will be found.

As warrior fighting the kulshedra, he is armed with the "beam of the plow and the plow-share", or a "pitchfork and the post from the threshing floor, and with the big millstones". He also employs his cradle as a shield to parry blows from the kulshedra.

These heroes may live unnoticed among humans and are thought to be "invulnerable, untouchable, and undefeatable". They have "supernatural powers which become apparent while they are still babies in their cradles. When thunder and lightning strike Dragùas assemble with their cradles at the Dragùa gathering place".

In southeastern Albanian regions of Pogradec and Korça, the dragùa is "envisaged.. as a beautiful strong horse with wings, who defends civilization and mankind".

"Male animals can also be born as dragùas. Black rams will attack a Kulshedra with their horns, and black roosters will furiously pick out its eyes. Only billy goats can never be dragùas".

Thunderstorms are conceived as battles between the drangues and the kulshedras, the roll of thunder taken to be the sounds of their weapons clashing. This shares many similarities with chaoskampf, a mythological trope of the Proto-Indo-European religion, where a Storm God battles a many-headed Sea Serpent. Drangues are believed to perpetually battle with the Kulshedra. Or he is said to have slain her for good, having knocked her unconscious by throwing trees and boulders at her, and afterwards drowning her in the Shkumbin River, according to the localized lore of central Albania.

In the Lahuta e Malcís (English: Highland Lute)—one of the most important heroic epics of Albania—the drangues are presented as the personification of the Albanian Highlands heroes, and are the central figures of the 16th and 17th cantos. In the 16th canto a kulshedra escapes from a cave in Shalë to take revenge on Vocerr Bala, a drangue. A force of drangues gather and defeat the kulshedra. After the battle they are invited by oras, female protective spirits, to celebrate their victory.

In the 17th canto the central figures are two drangues named Rrustem Uka and Xhem Sadrija. After preparing for a wedding ceremony, they travel to Qafë Hardhi (English: Grapevine Pass) to rest. While cleaning their weapons and smoking, they discover that eight Montenegrin battalions, consisting of three hundred soldiers led by Mark Milani, are marching against Plava and Gucia. The two drangues, with the help of local shepherds, defend Qafë Hardhi and force the Montenegrins to retreat at Sutjeska.

The belief that a dragùa can be born every day has persisted among Albanian mountain folk until recently, and there are still elderly people alive who espouse the belief.

In Malësia, a region in northern Albania and southern Montenegro inhabited mostly by Albanians, the locals believe that the drangues exist and live among them.

In Albanian folklore, Saint George and Saint Elias (also identified with the Old Testament prophet Elijah, possibly due to confusion with the Greek “Helios” as a translation of Late Ancient deity Sol Invictus) both have stories in which they fight (and defeat) a Bolla/Kulshedra. Saint Elias, in particular, is identified in some regions with the Dragùa and is also a weather god and provides protection against storms and fire.

9 notes

·

View notes