#antiquarian book Catalogue

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

New catalogue Fascicule 52

Early Printed BooksSpring 2024. Part A These 19 books are the authors whose names begin with A from Fascicule Nº 52 1) 508J Thomas, à Kempis, 1380-1471, attributed name.The following of Christ. Writen in Latine by Thomas of Kempis Canon regular of the order of St. Augustin. Translated into English and in this last edition, reviewed compared with several former editions. Together with the…

View On WordPress

#antiquarian book Catalogue#Aristotle#early printed books#Free catalogue#Incunabula#Natural history#Rare Book

0 notes

Text

Both the architecture of and the human being Oscar Niemeyer are very dear to my heart and so I was very positively surprised when I found the present German language book at an antiquarian bookshop for 5€: „Oscar Niemeyer - Selbstdarstellung, Kritiken, Oeuvre“, edited by Alexander Fils and published by Frölich & Kaufmann in 1982. It isn’t a monograph but rather a compilation of texts by Niemeyer about himself and his works, texts and criticisms by others and a rather interesting work catalogue. In view of the scarcity of German language literature about Niemeyer the compilation of mostly essays and articles makes total sense and provides rare insights into the architect‘s design principles as well as his personality. The latter shows in his deliberations about his relationship to communism and the Brazilian communist party PCB and again manifests his deeply humane and humble attitude to life. My personal highlight is a 1981 interview conducted by a German architecture journalist who tries to draw a connection between Niemeyer and German organic architects Hugo Häring and Hans Scharoun (both of whom Niemeyer has never heard of) and whom he gives a dry but hilarious runaround. To all my German readers: this book is a good value way to familiarize yourself with Niemeyer’s architecture, personality and design principles. Warmly recommended!

#oscar niemeyer#monograph#architecture book#architecture#brazil#architectural history#vintage book#book

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

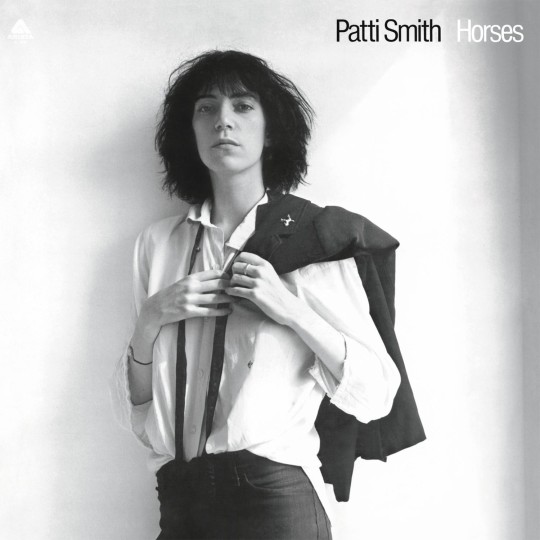

365: Patti Smith // Horses

Horses Patti Smith 1975, Arista

There’s a man named Nicky Drumbolis who lives up in Thunder Bay, Ontario, in an apartment that doubles as perhaps Canada’s greatest bookstore almost no one has ever seen. The septuagenarian Drumbolis is short and nearly deaf, a master printmaker and eccentric autodidact linguist. For years he ran a second-hand shop on Toronto’s Queen St. called Letters, until push (the size of his collection) came to shove (skyrocketing rent) and he went north, where he could afford a sufficiently large space to spread out. Unfortunately, Thunder Bay has little market for antiquarian books and micro press ephemera, and his shop is located on one of the most crime-ridden streets in the country. And so, the transplanted Letters has no storefront—in fact, the building looks derelict, its windows boarded up and covered with what at first glance seems to be graffiti but on closer inspection resembles a detail from the cave paintings at Lascaux. Letters’ patronage is limited to the online traffic in rare first editions that brings him a small income, and the occasional by-appointment adventurer willing to make the long, long 1,400 km drive from Toronto or further abroad.

When you enter, you find yourself in what appears to be a well-kept single room used bookstore, the kind there used to be dozens of in every major city. Books of every type and topic line the shelves, neatly arranged by category, and a long glass display features more delicate items, nineteenth century broadside newspapers and the like, some so fragile they seem on the verge of crumbling into dust. But this is not, Drumbolis warns you as soon as you attempt to take a book off of the shelf, a bookstore: this room is a facsimile, a tribute exhibit to as he calls it, “the fetish object formerly known as The Book.” The real bookstore lies in the chambers beyond this front room, the full catalogues of bygone presses, the one-of-one personal editions he’s assembled over decades of following his personal obsessions, the stacks which crowd his own modest sleeping quarters.

To Drumbolis, the original utility of the book as a container and mediator of information is now effectively passed; virtually every popular book in existence has been digitized, their contents instantly available in formats that are better-indexed, more easily parsed, and more readily transferrable than the humble physical book ever allowed. To desire a book is to desire possession of the thing rather than its contents, this edition, this printing, perhaps this particular copy that once passed through the hands of someone significant. He can show you the copy of John Stuart Mills’ On Liberty that was owned by Canada’s founding father John A. MacDonald, and argue convincingly that this object helped set the course of a nation’s history; or a set of Shakespeare’s complete works bearing Charles Dickens’ ex libris, which sets off a long anecdote about how Dickens liked to troll his houseguests with a collection of fake bookshelves. Drumbolis’s collection is threaded through his life like an old wizard in a fantasy novel whose flesh has fused with the roots of a tree: he eats with his books and he sleeps with them; collecting fuels his arcane research and dictates where and when he travels; 25 years ago he uprooted his life when his collection bade him, and though he’s starved for company in the frozen city it chose for him, he abides.

youtube

My own case of collectivitis is not so advanced, though Lord only knows what I’ll be like when I’m Old (I’m currently 47). And despite the conceit of this blog, I’ve seldom spent much time in these reviews dwelling on the physical properties of my records, evaluating the relative merit of pressings and the like (or even mentioning which one I’ve got). But as I sit here listening to my copy of Patti Smith’s Horses for the first time, I feel a small but definite sense of wonderment. It’s an early ‘80s Canadian pressing, so near-mint I might’ve stepped back in time and bought it new, still with what I take to be the original inner-sleeve, pale azure (to match the Arista disc label) with a texture almost like crepe paper.

It’s a delightful, surprising contrast to the iconic black and white cover portrait of Smith by her former paramour Robert Mapplethorpe. Generations of fans have stared at this image as they listened, not simply because Smith is hot (though this is undeniably true) but because the music’s visionary qualities demand an embodied locus. That a record, unlike a book, can speak aloud, has always primitively fascinated me; that this one contains what I can only describe as rituals makes it magical, this physical copy that is unique because it’s this one that is speaking to me in this moment.

Smith writes on the back of the sleeve:

“…it’s me my shape burnt in the sky its me the memoire of me racing through the eye of the mer thru the eye of the sea thru the arm of the needle merging and jacking new filaments new risks etched forever in a cold system of wax…horses groping for a sign for a breath…”

“charms, sweet angels,” she concludes. “you have made me no longer afraid of death.” The record becomes an extension of Smith’s body as it existed in that time—I think here of the physicality of the moment in “Break it Up” where you can faintly hear her striking her own chest with the flat of her palm to make her voice quaver. It makes me wonder how anyone could sell this thing once they have it: not because it is particularly rare or difficult to acquire, but because it’s hard for me to imagine the experience of slipping the lustrous black disc from its dressing and setting the needle down upon it as anything but a personal one. It is poetry and waves; the subliming of the idea of a rave-up; Tom Verlaine shedding his earthly mantle in an explosion of birds; John Cale; Kaye, Král, Daugherty, and Sohl; one of my boys from Blue Öyster Cult; the pounding of hooves and the Mashed Potato.

I suppose what I’m describing is a fetish, my pleasure in acquiring these things and writing these reviews the hard and strange work of finding life’s joy in its dusty corners. This year has run through my fingers like water, as it seems they all do now. But on my good days, all these words behind me and the records in front of me seem like a document of abundance.

youtube

365/365

#patti smith#horses#john cale#lenny kaye#ivan král#blue oyster cult#tom verlaine#punk rock#art rock#female singer#poetry#collecting#music review#vinyl record#'70s music#the end

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wenzel Coebergher - Preparations for the martyrdom of St Sebastian - 1599

oil on canvas, height: 288.5 cm (113.5 in); width: 207.5 cm (81.6 in)

Museum of Fine Arts of Nancy, France

Wenceslas Cobergher (1560 – 23 November 1634), sometimes called Wenzel Coebergher, was a Flemish Renaissance architect, engineer, painter, antiquarian, numismatist and economist. Faded somewhat into the background as a painter, he is chiefly remembered today as the man responsible for the draining of the Moëres on the Franco-Belgian border. He is also one of the fathers of the Flemish Baroque style of architecture in the Southern Netherlands.

Born in Antwerp, probably in 1560 (1557, according to one source), he was a natural child of Wenceslas Coeberger and Catharina Raems, which was attested by deed in May 1579. His name is also written as Wenceslaus, Wensel or Wenzel; his surname is sometimes recorded as Coberger, Cobergher, Coebergher, and Koeberger.

Before being known as an engineer, Cobergher began his career as a painter and an architect. In 1573 he started his studies in Antwerp as an apprentice to the painter Marten de Vos. Following the example of his master, Cobergher left for Italy in 1579, trying to fulfil the dream of every artist to study Italian art and culture. On his way there he stayed briefly in Paris, where he learned about his illegitimate birth from seeing the will of his deceased mother. He returned to Antwerp right away to settle some legal matters relating to this discovery. Later in the year, he set forth again to Italy. He settled in Naples in 1580 (as attested by a contract) and remained there till 1597.

In Naples he worked under contract for eight ducats together with the Flemish painter and art dealer Cornelis de Smet. He returned briefly to Antwerp in 1583, buying goods with borrowed money for his second trip to Italy. He is mentioned again in Naples in 1588. In 1591 he allied himself with another compatriot, the painter Jacob Franckaert the Elder (before 1551–1601).

He moved to Rome in 1597 (as attested in a letter to Peter Paul Rubens by Jacques Cools). During that time he had also been preparing a numismatic book in the tradition of Hendrik Goltzius. He must also have built up a reputation as an art connoisseur, since in 1598 he was asked to make an inventory and set a value on the paintings of the deceased cardinal Bonelli.

After the death of his first wife Michaela Cerf on 7 July 1599, he married again, four months later and at the age of forty; his second wife was Suzanna Franckaert, 15-year-old daughter of Jacob Franckaert the Elder, who was also active in Rome. He would have nine children with his second wife, while his first marriage had remained childless.

During his stay in Rome Cobergher became much interested in the study of Roman antiquities, antique architecture and statuary. He was also much interested in the way in which Romans represented their gods in paintings, bronze and marble statues, bas-reliefs and on antique coins. He gathered an important collection of coins and medals from the Roman emperors. These drawings and descriptions were gathered in a set of manuscripts, two of which survive (Brussels, Royal Library of Belgium). He was also preparing an anthology of the Roman Antiquity (according to the French humanist Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc) that was never published. Sometimes the "Tractatus de pictura antiqua" (published in Mantua, 1591) has been ascribed to Cobergher, but this was based on an erroneous reading of an 18th-century catalogue.

At the same time he was witness to the completion of the dome of St. Peter's Basilica in 1590. The architecture of several Roman churches made also a deep impression on him; among them most influential were the first truly baroque façade of the Church of the Gesù, Santa Maria in Transpontina and Santa Maria in Vallicella. He would use their design in his later constructions.

During his stay in Italy he painted, under the name "maestro Vincenzo", a number of altarpieces and other works for important churches in Naples and Rome. His style is somewhat mixed, incorporating Classical and Mannerist elements. His composition is rational and his rendering of the human anatomy is correct. A few of his altarpieces still survive: a Resurrection (San Domenico Maggiore, Naples), a Crucifixion (Santa Maria di Piedigrotta, Naples), a Birth of Christ (S Sebastiana) and a Holy Spirit (Santa Maria in Vallicella, Rome). One of his best known paintings is the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, originally in the Cathedral of Our Lady (Antwerp), but now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nancy. This painting was commissioned by the De Jonge Handboog (archers guild) of Antwerp in 1598, while Cobergher was still in Rome. His Angels Supporting the Dead Lord, originally in the Sint-Antoniuskerk in Antwerp, can now also be found in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nancy, while his Ecce Homo is now in the museum of Toulouse.

Cobergher died in Brussels on 23 November 1634, leaving his family in deep financial trouble. His properties in Les Moëres had to be sold, as well as his house in Brussels. Even his extensive art and coin collection was auctioned off for 10,000 guilders.

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

pick three oc's to assign to book shop owner, cafe owner, flower shop owner! tell us about their shops!

oohohhoho

bookshop owner - bee.

she loves books, especially ones that are rare and difficult to acquire, so i think she'd run an antiquarian bookstore. it would be cluttered, cramped and dark, but in a somewhat cozy way, with the smell of freshly-baked pastries permeating the air (bc she loves baking). it would be difficult to find, but worth it - the rumor goes, there isn't a book she can't track down.

cafe owner - polina.

alright, it wouldn't be a cafe, per se, but instead like a space somewhere between a bar, a cafe, an art space and a squat. pretty dingy, but a well-loved and cared-for hangout spot for everyone who feels like an outsider in the wider society or just anyone craving a sense of community. she'd host really popular karaoke nights weekly.

flower shop owner - dario.

he may be better with animals than plants, but one of his favorite activities while living in a manor in baldur's gate was walking through the gardens as dawn would break. the plants and flowers really calmed them, and so i think their flower shop would strive for a similar vibe - a really quiet and bright space. with a very neatly catalogued selection and very long and specific caring instructions for each plant, lmao.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On November the 4th 1966, the river Arno flooded into Florence burying hundreds of thousands of books, manuscripts and artwork beneath mud, debris and putrid water. Due to this massive cultural and historical devastation, countries responded quickly with financial aid and restoration research. It became imperative to combine modern science with historical book making techniques in order to save and restore the damaged antiquarian books and manuscripts. Experimental research was used from The Institute of Book Pathology in Rome, and The Imperial College of Science and Technology in association with The Royal College of Art in London.

Damaged books were given emergency washing and drying treatments and then sterilised against bacteria and mould. The edges of a lot of books were badly stuck with mud, gelatine and sawdust. The covers/boards, spines, headbands and everything surrounding the text block were removed and catalogued in envelopes. Once the spine was clear the sewing was cut from the spines and the sections separated carefully. Mud was scraped from the leaves of the book, and especially bad books were soaked in an alcohol and water mixture and then interwoven with wet strength paper and washed again. Coloured plates and prints were sprayed with a solution of soluble nylon in alcohol to preserve them. Any oil that may have damaged the books was removed with a solution of xylene and trichloroethylene. Fuller’s Earth was applied delicately and brushed off to remove excess chemical solution and oil.

Thermostatically controlled, stainless steel, sinks were used to wash the books leaf by leaf in a fungicide solution. Some particularly fragile leaves were resized. pH tests were conducted and if a book had too much acidity, it was deacidified. Bleach staining is not considered good practice, and was limited to the leaves that were so stained that the text was illegible. The individual leaves were dried at controlled temperatures in specially made drying cabinets. Once dry, the leaves were checked and put in order. (Plates and prints were handled separately to the main text blocks as extra care had to be taken due to the colours.)

Before sewing and binding could take place, repairs were made to the leaves caused by the flood and early binding techniques. Lens tissue was used for small tears, and Japanese tissue paper was used for serious tears and missing sections of leaves.

Books were sewn back together with thread and techniques dependent on their size and publication date. Appropriate bindings were also chosen depending on the use of the book and its time period. The majority of the damaged Antonio Magliabechi manuscripts and volumes from the National Library of Florence were bound in limp vellum. Other rare books required new leather bindings.

The restoration of books, manuscripts, art and historical artefacts from the 1966 flood is still an ongoing process today. Many people had to be trained specially to restore books on site in Florence, as shipping damaged books to experts across the world was deemed to be impractical and quality could not be controlled. There was also the risk that the books would be lost or damaged further in transit.

Floods and natural disasters cause widespread damage but are fortunately not that common. Some books are damaged over time due to use and age. Working in a second-hand bookshop, I see a lot of old books that are damaged; missing spines and boards, detached boards, bumped corners, missing labels and stained. Modern books are notoriously poor quality and tend to fall apart easily in comparison to their sewn, medieval ancestors. There is a genuine calling for restoration and book binding experts. Some old books are scarce, and some books have signatures or notes in their margins from historically important people which make them unique and irreplaceable. For the individual, books passed down through the generations hold significant sentimental value and may need repairs or complete new bindings. If history teaches us anything, it is that we need to continue to find methods and solutions to protect and save items of historical importance.

References:

The Restoration of Books: Florence – 1968. – YouTube

The Disaster that Deluged Florence’s Cultural Treasures – HISTORY

The great flood of Florence, 50 years on | Art and design | The Guardian

https://blog.outletpublishinggroup.com/2023/02/23/blog-156-the-importance-of-book-restoration/

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

Once Upon a Tome | Oliver Darkshire

This was a delightful read. Who wouldn’t enjoy a book about booksellers, particularly antiquarian booksellers? This memoir describes how the author became an apprentice bookseller at an old bookshop in London. It was a clever and interesting look into the antiquarian book trade. Well written and packed with intriguing book-related information. I enjoyed his stories about cataloguing, book…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

Do you know of any pop culture stuff that has an at least semi-accurate portrayal of Mesopotamian history?

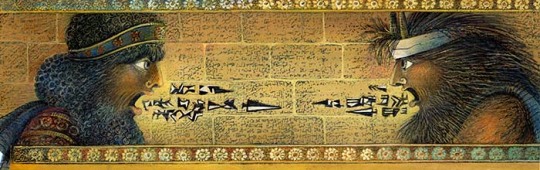

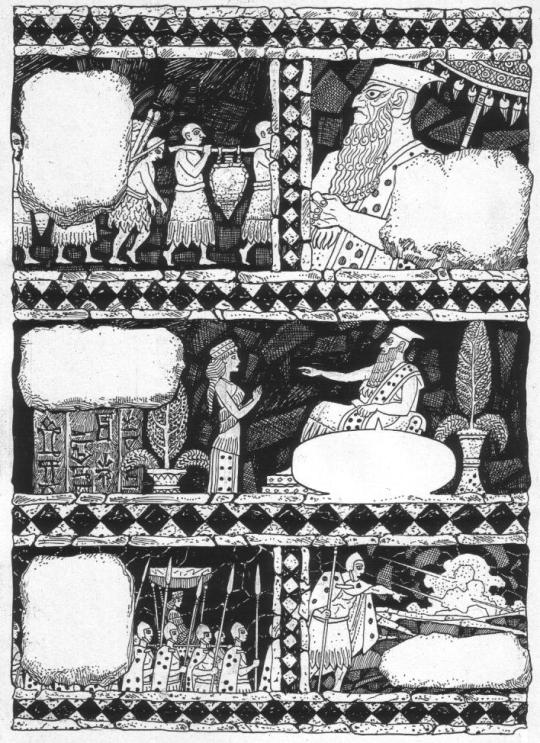

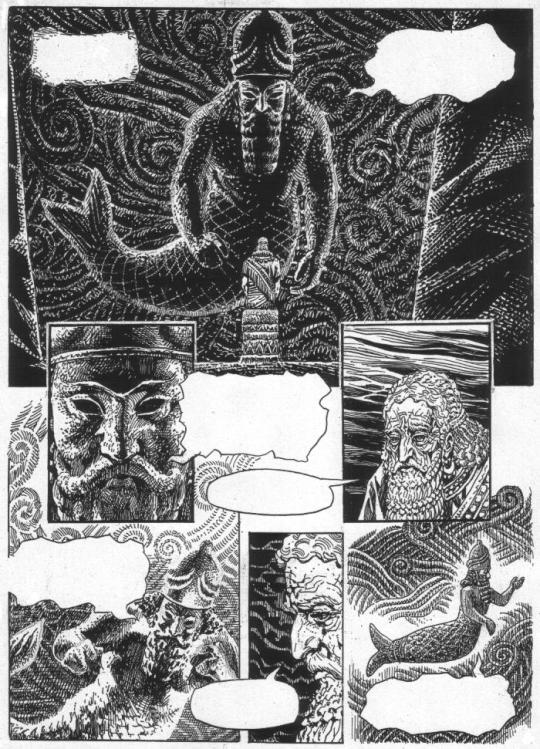

Well, not quite popculture, I suppose, but there actually is a fair share of genuinely great Gilgamesh-based art, two examples I personally like are M. Żuławski's (left; you can find an exhibition catalogue here) and L. Zeman's (right; you can find more of these illustrations here, I believe they come from an adaptation aimed at children?). There are actually many others, these are just the two sets of illustrations I remember the best rn. I also think that trailer for an animated Gilgamesh movie from a few years ago looked fine, I really like the Siduri design apparently made for it too (she's not in the trailer though, I believe) - I think this is the first time I see a work of media acknowledge she's actually meant to be a goddess and not a random mortal woman like many people seem to assume, lol.

There is also Enrique Alcatena's comic Ziggurat which looks breathtaking but I was not able to read it (yet). It's obviously using art from more than one period as inspiration (also, Elamite and even Oxus Civilization art shows up as obvious inspiration for a few monster designs), but I enjoy that, and arguably given how "antiquarianism" and purposely vintage-styled art were both in the vogue in ancient Mesopotamia it adds to the authenticity in a way.

What surprises me is that, mythological fantasy aside, there seem to be no historical novel set in like, the Ur III period. Most of what I can think of is Bible-based fiction, in which Mesopotamians are obviously one-dimensional villains (just like Egyptians tend to be in this genre, lol) and the familiarity of the authors with history is... more than limited. I think I've seen more detective novels set in Tang period China than I've seen novels set in ancient Mesopotamia, and considering how I actually work with books that's... probably saying something. In terms of games it's... not much better. Megaten has a few genuinely great designs - Mushussu, Apsu, Tiamat, Nergal, both Anzus, I actually even sort of like Pabilsag as a scorpion man design; the Civilization series has a cool Gilgamesh from what I've seen (should've gone with Shulgi though smh... getting 0 respect due to being overshadowed by Sargon and Hammurabi) but I genuinely can't think of many more examples. Straying more from popculture, but I've seen some old Iraqi postage stamps (I think like... 1960s?) with art related to the country's antiquity, I can't find them rn but they were very pretty. Commercial art is popculture too, right? As a side note, if anyone from the Iraqi Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Antiquities is reading this, please consider an app with cutesy cartoony versions of famous artifacts like the haniwa one the Gunma prefecture board of tourism made a few years ago, please. I would play it 100% ALSO does graffiti count as popculture? Because I’ve seen a photo of an Inanna mural which is probably one of my favorite Inannas overall a few months ago (source; the link is not nsfw but iirc some of the other photos on this account are) Also, this is not strictly Mesopotamian, but one episode of the French cartoon Papyrus featured traveling priests from Ebla and as far as I can tell their portrayal did match what was known about the city in the 1990s: NI-da-KUL is not really read as "Nidakul" today, but usually as "Hadabal," but the moon god theory is still valid (his cult center was later "repurposed" for Yarikh whose lunar credentials are not to be doubted), and they even managed to build the episode around the worship of this god involving a regular pilgrimage, though obviously its course shown (Ebla->Ugarit->Byblos->Tyre->Ashkelon->Egypt) is entirely fictional (I don't think any kid would be interested in seeing a cartoon about an old dude traveling through Bronze Age countryside though so it's fine).

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Scottish archaeologist and scholar Daniel Wilson was born on January 5th 1816 in Edinburgh.

Wilson attended Edinburgh High School before being apprenticed to a steel engraver. Between 1837 and 1842 he worked in London as an engraver and popular writer, but returned to Edinburgh to run an artist’s supplies and print shop.

Although Wilson developed an interest in history and matters antiquarian from a relatively early age, it was not until he was invited to help turn the collections of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland into a modern national museum that he turned from antiquarianism to archaeology. In reorganising the collection he adopted the Danish model of ordering the artefacts according to the Three Age System, it is due to his work we have The National Museum of Scotland, as we know it today.

He wrote Memorials of Edinburgh in the Olden Time in the 1840s, a book I have perused online many times, scouring for information for many posts over the years.

Wilson’s arrangement presented an evolutionary approach to viewing the artefacts, and this also came across in the catalogue that he wrote to go with the exhibition. Later, in 1851, he published an extended version of the catalogue as Archaeology and prehistoric annals of Scotland, his was the first comprehensive treatment of early Scotland based on material culture and the first time that the term ‘prehistoric’ was used in English, so he basically invented the word!!

Although Wilson received an honorary degree from the University of St Andrews, he was unable to get an academic position in Scotland. In 1853, with help from friends in Edinburgh, he was appointed to the Chair of History and English Literature in University College, Toronto, Canada. Wilson enjoyed teaching in Canada and continued his interest in archaeology, but all the while expanded his interest in anthropology and ethnography. Throughout his life he was a talented landscape painter, having worked with J. M. W. Turner studio during his time in London.

In 1888 Wilson was knighted for his services to education in Canada, and in 1891 given the freedom of the city of Edinburgh. He died in Toronto on August 6, 1892. The Sir Daniel J. Wilson Residence at the University College in University of Toronto is named in his honour.

You can find Edinburgh in the Olden Time on the link below

http://edinburghbookshelf.org.uk/volume10/

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I feel like I don’t wanna do something

I start writing my blog. It helps me refreshing and that helps me a lot sometimes.

Or sometimes when I feel I don’t want to write, Copying a well written article is another great choice. When I copy a well written article, it makes me to dream that I can be a great writer like she,or he does.

Being a great writer is like being a great baker. Every piece of article brings me hundreds and thousands of flavours and motivation. Sometimes it makes the reader to swim in the ecstasy.

Today, I am going to copy an article from The Newyorker by Max Norman.

- Memoir=전기.실록.

- alter = 바꾸다, 개조하다

- humdrum =단조로운, 평범한

- venerable =존경할 만한

- idiosyncratic= 특���한

(This is a short aritcle by me using the key words that I think are emphasized in the original article)

I am a person with my own idiosyncratic view, which people thinks that I am little bit odd. Depends on how a person is living- how successful they are, people call one with all the different names. “sir”, “witch”,or maybe guy who is little bit “insane”. I want to be a venerable person who writes a memoir. However, to be a person with a glory in whatever way it is, that person should endure a very humdrum life, which can be extremely monotony at the same time.

What We Gain From a Good Bookstore.

It’s a place whose real boundaries and character are much more than its physical dimensions.

“Will the day come where there are no more secondhand bookshops?” the poet, essayist, and bookseller Marius Kociejowski asks in his new memoir, “A Factotum in the Book Trade.” He suspects that such a day will not arrive, but, troublingly, he is unsure. In London, his adopted home town and a great hub of the antiquarian book trade, many of Kociejowski’s haunts- including his former employer, the famed Bertram Rota shop, a pioneer in the trade of first editions of modern books and “one of the last of the old establishments, dynastic and oxygenless, with a hierarchy that could be more or less described a s Victorian”-have already fallen prey to rising rents and shifting winds. Kociejowski dislikes the fancy, well-appointed bookstores that have sometimes taken their places. “I want chaos; I want, above all, mystery,”he writes. The best bookstores, precisely because of the dustiness of their back shelves and even the crankiness of their guardians, promise that “somewhere, in one of their nooks and crannies, there awaits a book that will ever so subtly alter one’s existence.” With every shop that closes, a bit of that life-altering power is lost and the world leaches out “ more of the serendipity which feeds the human spirit.”

Kociejowski writes from the “ticklish underbelly” of the book trade a s a “factotum” rather than a book dealer. His memoir is a representative slice, a core sample, of the rich and partly vanished world of bookselling in England from the late nineteen-seventies to the present. As Larry McMurtry puts it, in his own excellent (and informative) memoir of life as a bookseller, “Books,” “the antiquarian book trade is an anecdotal culture,” rich with lore of the great and eccentric seller and collectors who animate the trade. Kociejowski writes how “the multifariousness of human nature is more on show” in a bookstore than in any other place, adding, “I think it’s because of books, what they are, what they release inn ourselves. and what they becaome when we make them magnets to our desires.”

The bookseller’s memoir is, in part, a record of accomplishments, of deals done, rarities uncovered-or, in the case of the long-suffering Shaun Bythell, the owner of the largest secondhand bookstore in Scotland, the humdrum frustration and occasional pleasures of running a big bookshop, While Kociejowski recounts some of the high points of his bookselling career (such as cataloguing James Joyce’s personal library of briefly working at the fusty but venerable Magg Bros., the anitiquarian booksellers to the Queen), he above all remembers the character he came to know. “I frimly believe the fact of being surrounded by books has a great deal to do with flushing to the surface the inner lives of people,” he writes.

Some of them are famous, like Philip Larkin, who, as the Hull University librarian, turned down a pricey copy of his own first book, “The North Ship,” as too expensive for “That piece of rubbish.” Kociejowski tells us how he offended Graham Greene by not recognizing him on sight, and once helped his friend Bruce Chatwin (”fibber thought he was”) with a choice line of poetry for “On the Black Hill”’ how he bonded over Robert Louis Stevenson with Tatti Smith, and sold a second edition of “Finnegans Wake” to Johnny Depp, of all people, who was “trying incredibly hard not to be recognised and with predictably comic results.” But more precious are the memories of the anonymous eccentrics, cranks, biliomanes, and mere people who simply, and idiosyncratically love books. “Where is the American collector who wore a miner’s lamp on his forehead so as to enable him to penetrate the darker in asking not for books but the old bus and tram tickets often found inside them? Where is the man who collected virtually every edition of The Natural History of Selborne by Reverend Gilbert Whitie? Where is everybody?” Kociejowski’s tone, though mostly wry, cerges on lament. “I cannot help but feel something has gone out of the life of the trade,” he writes.

And there are more paragraphs down below that but I have decided not to write. I new see how The Economics is more accessable to all variety of people compare to The Newyorker, Next time, I am going to more prefer to cite from The Economics. Well,, It does not means I learns nothing by copying the articles from The Newyorker but I guess I will be able to learn more if it’s The Economics instead.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fascicule #50 is still available!

50 fifteenth & sixteenth century books : arcane, sacred, sublime & practical. Please email me for a printed copy [email protected] Many of these books were on display at the Toronto Antiquarian Book show and the Boston Antiquarian Book Show, in October. TO see it before the printed copy arrives follow this link Fascicule #50 will soon be in the…

View On WordPress

#Annotated#antiquarian book Catalogue#Aquinas#Arcane#Aristotle#Book of Hours#demonology#Emblem book#Emblem Books#Fascicule 50#free catatlogue#FREE rare book catalogue#Heures#Illustrated#Illustrated catalogue of incunabula#Incunabula#Witchcraft

0 notes

Text

The present book is an antiquarian treasure: „Beck-Erlang“, edited by Gisela Schultz and Frank Werner and published by Hatje Cantz in 1983. It is the first and for a long time only work catalogue of Wilfried Beck-Erlang (1924-2002), one of Germany‘s most interesting postwar architects. Beck-Erlang was an individualist whose work isn’t characterized by a signature style but a continuous search for the right solution for each building task. Projects like the Zürich-Vita-Haus or his own house and studio, both located in Stuttgart, are built manifestos of his sophisticated approach to architecture. Although the book only includes a short introduction by Frank Werner it provides, based on extensive plan and photographic material, an exciting overview of the work of an immensely creative architect. For deeper insights into Beck-Erlang’s life and work I strongly recommend Carsten Wiertlewski’s dissertation „Beck-Erlang - Das Werk des Architekten Wilfried Max Beck“ from 2012 which can be downloaded for free via e.g. the German National Library’s catalogue.

#wilfried beck-erlang#architecture book#monograph#architecture#germany#nachkriegsarchitektur#nachkriegsmoderne#book#vintage book

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Will the day come where there are no more secondhand bookshops?” the poet, essayist, and bookseller Marius Kociejowski asks in his new memoir, “A Factotum in the Book Trade.” He suspects that such a day will not arrive, but, troublingly, he is unsure. In London, his adopted home town and a great hub of the antiquarian book trade, many of Kociejowski’s haunts—including his former employer, the famed Bertram Rota shop, a pioneer in the trade of first editions of modern books and “one of the last of the old establishments, dynastic and oxygenless, with a hierarchy that could be more or less described as Victorian”—have already fallen prey to rising rents and shifting winds. Kociejowski dislikes the fancy, well-appointed bookstores that have sometimes taken their place. “I want chaos; I want, above all, mystery,” he writes. The best bookstores, precisely because of the dustiness of their back shelves and even the crankiness of their guardians, promise that “somewhere, in one of their nooks and crannies, there awaits a book that will ever so subtly alter one’s existence.” With every shop that closes, a bit of that life-altering power is lost and the world leaches out “more of the serendipity which feeds the human spirit.”

Kociejowski writes from the “ticklish underbelly” of the book trade as a “factotum” rather than a book dealer, since he was always too busy with writing to ever run a store. His memoir is a representative slice, a core sample, of the rich and partly vanished world of bookselling in England from the late nineteen-seventies to the present. As Larry McMurtry puts it, in his own excellent (and informative) memoir of life as a bookseller, “Books,” “the antiquarian book trade is an anecdotal culture,” rich with lore of the great and eccentric sellers and collectors who animate the trade. Kociejowski writes how “the multifariousness of human nature is more on show” in a bookstore than in any other place, adding, “I think it’s because of books, what they are, what they release in ourselves, and what they become when we make them magnets to our desires.”

The bookseller’s memoir is, in part, a record of accomplishments, of deals done, rarities uncovered—or, in the case of the long-suffering Shaun Bythell, the owner of the largest secondhand bookstore in Scotland, the humdrum frustrations and occasional pleasures of running a big bookshop. While Kociejowski recounts some of the high points of his bookselling career (such as cataloguing James Joyce’s personal library or briefly working at the fusty but venerable Maggs Bros., the antiquarian booksellers to the Queen), he above all remembers the characters he came to know. “I firmly believe the fact of being surrounded by books has a great deal to do with flushing to the surface the inner lives of people,” he writes.

Some of them are famous, like Philip Larkin, who, as the Hull University librarian, turned down a pricey copy of his own first book, “The North Ship,” as too expensive for “that piece of rubbish.” Kociejowski tells us how he offended Graham Greene by not recognizing him on sight, and once helped his friend Bruce Chatwin (“fibber though he was”) with a choice line of poetry for “On the Black Hill”; how he bonded over Robert Louis Stevenson with Patti Smith, and sold a second edition of “Finnegans Wake” to Johnny Depp, of all people, who was “trying incredibly hard not to be recognised and with predictably comic results.” But more precious are the memories of the anonymous eccentrics, cranks, bibliomanes, and mere people who simply, and idiosyncratically, love books. “Where is the American collector who wore a miner’s lamp on his forehead so as to enable him to penetrate the darker cavities of the bookshops he visited? Where is the man who came in asking not for books but the old bus and tram tickets often found inside them? Where is the man who collected virtually every edition of The Natural History of Selborne by Reverend Gilbert White? Where is everybody?” Kociejowski’s tone, though mostly wry, verges on lament. “I cannot help but feel something has gone out of the life of the trade,” he writes.

Like many memoirs, “A Factotum in the Book Trade” is a nostalgic book, wistful for the disappearance of bookselling—antiquarian books in particular, but also new titles—as a dependable, albeit never very remunerative, profession. The Internet dealt a major blow by creating a massive single market for used books, undercutting the bread-and-butter lower end of the secondhand market. Amazon, in turn, depressed the prices of new books. And then there are rising rents, which have devastated small businesses of all kinds. What dies with each bookstore isn’t just a valuable haven for books and book people but also “a book’s worth of stories” like Kociejowski’s, a book full of characters, of the major passions that heat up our minor lives. The fact that bookstores have been allowed to close, Kociejowski writes, represents “an overall failure of imagination, an inability to see consequences.”

While Kociejowski mourns bookselling’s past, Jeff Deutsch, the head of the legendary Seminary Co-op Bookstores, in Chicago, thinks through its future in his new book, “In Praise of Good Bookstores.” “This book is no eulogy,” Deutsch writes. “We can’t allow that.” Free from Kociejowski’s charming, twilight-years saltiness, Deutsch’s tone is an earnest, even idealistic consideration of what we gain from a good bookstore, and what we risk losing if we don’t overcome the failure of imagination—and of economics—that has allowed so many bookstores to close.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In this catalogue of rare books for sale, item 511 is of particular note. It lists for sale a certain Necronomicon as written by Abdul Alhazred. Philip C. Duschnes, the antiquarian bookseller responsible for arranging the catalogue, included this entry as a prank. (The catalogue dates from approximately 1946, I think.)

I’ll admit, though, I would have immediately paid the asking price of $375, as it seems a wonderful bargain in exchange for such forbidden eldritch knowledge…

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

antiquarian circle but it's not just fieldwork, you get such exciting minigames as:

cataloguing antiquities!

finding the right books for research!

transcribing and proofreading others' research!

translating inscriptions on some antiquities with a fun linguistic puzzle!

fill in the blanks in essays from clues about the antiquities!

unironically, I would enjoy this

I think I miss studying

5 notes

·

View notes