#anti-fascist photomontages

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

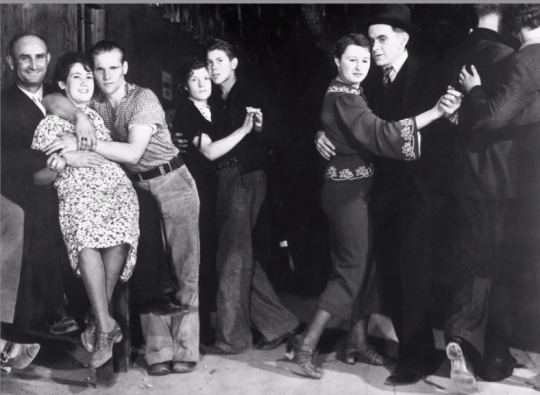

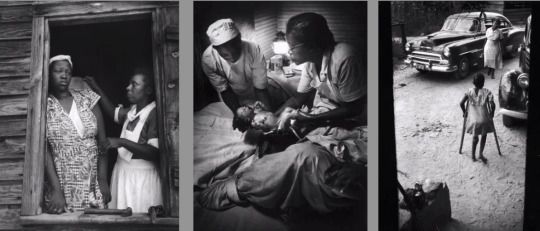

Political and documentary photography posters from the 1970s

In the late 70s, the cash-strapped Half Moon Gallery in London developed an innovative approach to getting its shows seen. Showcasing socially engaged photographers such as Daniel Meadows, Janine Wiedel and Philip Jones Griffiths, it laminated their prints and shipped them by rail as touring exhibitions.

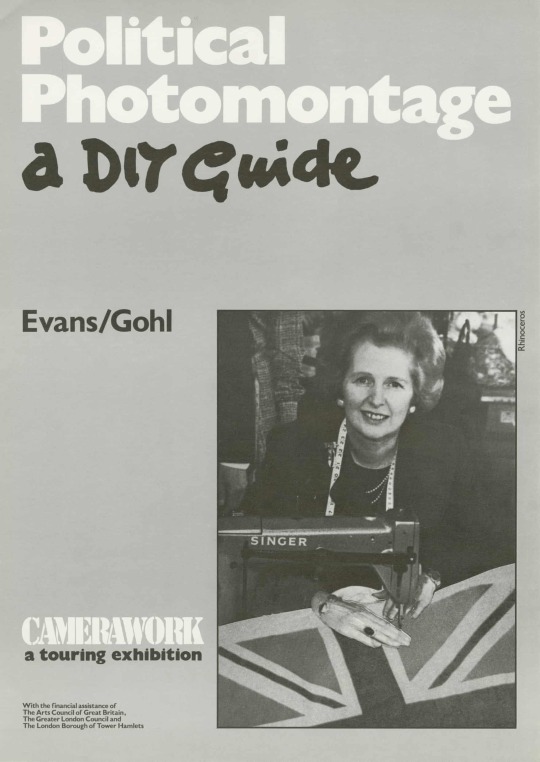

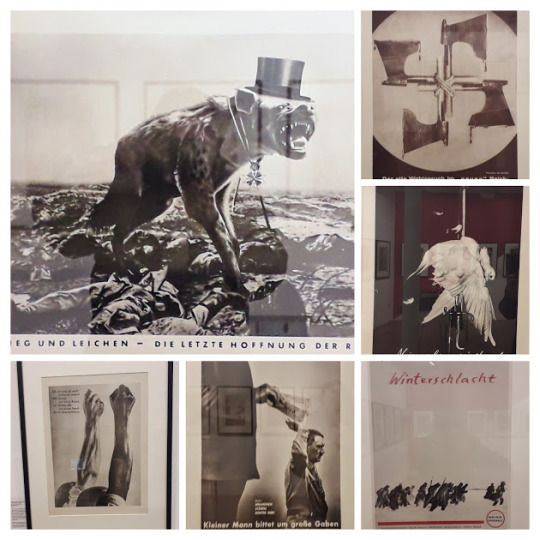

Political Photomontage, a DIY Guide, 1983. The rediscovery of John Heartfield’s anti-fascist photomontages of the 1930s led to new forms of visual protest against Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government. David Evans and Sylvia Gohl played an important part in introducing photomontage theories and approaches to British audiences, with several exhibitions and publications.

Photograph: ©Rhinoceros

#©Rhinoceros#photographer#political and documentary photography posters#half moon gallery#london england#social engaged photographers#political photomontage a diy guide 1983#john heartfelt#anti-fascist photomontages#visual protest#margaret thatcher#conservative government#david evans#sylvia gohl

1 note

·

View note

Text

John Heartfield

John Heartfield made the word

"photomontage" for his famous political art collages. He is one of history's most prolific collage masters, employing art as a weapon to answer fascist and Nazi propaganda. Heartfield lived openly in Berlin during Hitler's rise to power as popular magazines and posters displayed his anti-Nazi antifascist collage throughout the city. - from johnherttfiled.com

I actually really like this work it almost brings a simpler side to the art and the changes as it’s just cutting pictures and adding others that are already printed. I would like to have a go but do running out of time I am unable to.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jhon heartfield

John Heartfield (born Helmut Herzfeld, 1891–1968) was a German visual artist and one of the pioneers of political photomontage. He is best known for his sharp anti-fascist and anti-Nazi art, which he created during the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich. Heartfield’s works were critical of Nazi propaganda and German militarism, using photomontage to create powerful, satirical images that conveyed his political messages.

Heartfield fled Germany in 1933 when the Nazis came to power, relocating first to Czechoslovakia and later to England. After World War II, he returned to East Germany and continued his work until his death in 1968. His politically charged art remains influential and is considered groundbreaking for its use of photomontage to deliver a strong ideological critique.

0 notes

Text

Photomontage Research

The alluring art of photomontage.

Photomontage work includes various types of image editing in which multiple photographs are cut up and combined to form one new image. This can involve cutting up printed images, which is how magazine editors used to design publications before digital design software existed — creating layouts called pasteups. But now, digital design tools like Adobe Photoshop make it easier than ever to bring imaginative scenes to life using existing imagery, without paste or paper cuts. When performed digitally, photomontage can also be called compositing.

Photo collages bring dreamlike visions to life.

Fine art photographer and visual artist Edwin Antonio describes photomontage as “a vision, a dream that an artist has, which takes multiple images to create.” Graphic designer and collage artist Lana Jokhadze agrees. “Photomontage gives you the opportunity to create works of art from anything that’s on your mind,” she says. “I used to imagine that I was sitting on a different planet, looking at the sun and Earth side by side. With digital photo collage, I can transfer a vision like that to the screen.”

Photomontage took off in the early twentieth century.

Collaging might conjure images of a teenager in the nineties, decorating their locker with magazine clippings of mass media stars. But this type of mixed media art has deeper roots that started with subversive German artists in the surrealist movements of the early twentieth century, around the time of World War I.

It all started with combination printing.

Back in the mid-nineteenth century, combination printing, an early type of photo manipulation, paved the way for photomontage. Combination printing was the process of developing one image using multiple negatives. This process was necessary because it was difficult to get various light levels to expose well at the same time, but it soon led to photographers creating more imaginative photographic images than ever before. Art photographer Oscar Rejlander helped pioneer early experimentation in combination printing and went on to create the first well-known photo montage, The Two Ways of life, in 1857.

Modern collages follow in the footsteps of Dadaism.

German Dadaists in the mid- to late 1910s, like Hannah Höch, John Heartfield, Raoul Hausmann and Kurt Schwitters, used photomontage as a way to make images that channeled their anti-fascist beliefs. Similar were the artists in the Russian constructivist movement, such as Alexander Rodchenko and Gustav Klutsis, who incorporated typography and graphic design in their angular collages. During the same era, Man Ray and Salvador Dali were associated with cubism and the surrealist painting movement; they created dream-like photomontages that played with perspective and the human form. Photomontage then became a facet of pop art into the seventies and eighties, adopted by British conceptual artists like John Stezaker and David Hockney, who explored patterns, repetition and the recycling of commercial images. Look up work by these artists for inspiration.

https://www.adobe.com/mt/creativecloud/photography/discover/photomontage.html

1 note

·

View note

Text

And yet it moves john heartfield

AND YET IT MOVES JOHN HEARTFIELD MOVIE

AND YET IT MOVES JOHN HEARTFIELD SERIES

Should Men Fall Again that Shares May Rise?! © The Heartfield Community of Heirs / DACS 2019 By cutting and combining crisp images from newsprint, advertisements, and his own photographs, Heartfield created entirely new images of satire and juxtaposition, using the new form of art to emphasize its political function. During the interwar period, Heartfield was instrumental in pioneering a new form of art that came to define his signature, bitingly satirical style: photomontage. Heartfield believed wholeheartedly that art was intended to shape social change, and his work did that in part by changing art itself. The Four Corners chose its opening date intentionally Britain’s official exit from the EU was a highly political day, and Heartfield’s artwork is decidedly political. That evening in Tower Hamlets, the Four Corners Gallery debuted One Man’s War, an art display dedicated to the photomontage work of John Heartfield, Berlin Dadaist, communist, and a staunch anti-fascist in Weimar and Nazi Germany. In the 2016 introduction to her bestselling novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood quotes a timeless aphorism: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” It appears that the present, indeed, is rhyming with history.Īlso on October 31 st, a new art exhibition opened in London. Another delay prevented the departure, but again, the British public-and the world-had held its breath in anticipation. "L'aspirant habite Javel et moi j'avais l'habite en spirale.On October 31 st, 2019, the UK intended to leave the European Union. "Parmi nos articles de quincaillerie par essence, nous recommandons le robinet qui s'arrête de couler quand on ne l'écoute pas." "Avez-vous déjà mis la moëlle de l'épée dans le poêle de l'aimée?" "Esquivons les ecchymoses des Esquimaux aux mots exquis." "Inceste ou passion de famille, à coups trop tirés." "On demande des moustiques domestiques (demi-stock) pour la cure d'azote sur la côte d'azur." "Si je te donne un sou, me donneras-tu une paire de ciseaux?" "L'enfant qui tète est un souffleur de chair chaude et n'aime pas le chou-fleur de serre-chaude." "Bains de gros thé pour grains de beauté sans trop de bengué." (BenGay was invented in France by Dr.

AND YET IT MOVES JOHN HEARTFIELD SERIES

He also added a series of spiraling phrases that are intended to be puns. Duchamp made a series of spirals and filmed them while turning on a phonograph turntable.

AND YET IT MOVES JOHN HEARTFIELD MOVIE

Ordinary objects seem to come to life and have a will of their own in this plotless movie that uses stop action animation in a very original way.Īnemic Cinema, 1926. In this 6 minute film, Richter appears in the movie along with two composers, Darius Milhaud, and Paul Hindemith who wrote the music for the now destroyed soundtrack. The First World War is a largely forgotten conflict for most Americans, but the memory of that war still touches open wounds for a lot of Europeans, even a century later, as you can see in the large attendance at this ceremony and every ceremony at the Menin Gate.Ī film by Hans Richter, 1928. The Menin Gate is a war memorial whose walls are covered with the names of British, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealander soldiers who perished in fighting around Ypres, and whose bodies were never recovered.Įvery evening buglers from the Ypres fire department play The Last Post, and have done so since 1918, except for the years of German occupation during World War II. The First World War: The Menin Gate, Ypres Belgium Marcel Duchamp, The Large Glass (The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even)

0 notes

Text

Reflection on the Heartfield short film

I really enjoyed this film and found the deep dive into this artist to be extremely fascinating; definitely an enjoyable watch. I have quite a few things to say about it so bear with me for a moment.

Firstly, in a slightly unrelated note I just want to say that I’m starting to really get into dada. It’s such a cool and intriguing art movement and I can definitely see how this would inspire the punk movement years later. To me it just really is vintage punk and I love that. I say this seeing how Heartfield was a dada artist, I wanted to just get my opinions on dada out of the way before I discuss his work alone.

Now getting into the film itself, it talks about John Heartfield and his life and how growing up in the world he did, that world being one torn apart be war, influenced his art and his strong anti fascist behavior.

Tragedy and injustice are themes that are both present in Heartfield’s art and his life. As a kid he was forced to leave his home of Berlin and not soon thereafter he and his siblings lost both of their parents. On just a random day his father disappeared which lead his mother to abandon her family as well. For four days heartfield wandered around looking for his parents but couldn’t find them. Truly a heartbreaking and tragic event that most definitely shaped him for the rest of his life. As one of his brothers would later say “ the event left a deep and lasting scar…ever after he was to react to every injustice he witnessed as if it was perpetrated against him personally”. A statement to take in consideration considering the path he would take. It’s very clear this mindset was a major force in influence his politics and his artistic expression. It’s no wonder why he joined the politic dada movement once he returned back to Berlin, or joined the German communist party. Witnessing the war efforts around him truly was were life for him changed, especially with witnessing world war 2 as it happened

Moving on to his art, I would describe it as beautifully haunting. Heartfield is considered the father of photomontage and while for some of his pieces it is used as a satire medium, the serious pieces become much more radical and the medium is used to convey perfectly the certain kind of horror that comes with fascism. Heartfield is truly able to convey to his audiences the rage, sorrow, and injustice he feels in his art. I think the piece that stuck out to me the most was the one titled “ This is the salvation they bring”. His art really does a good job of making the uncomfortable statement about the war without becoming overly gruesome.

Overall I think John Heartfield was a wonderful and extremely important artist, and deserves more recognition then he has gotten.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

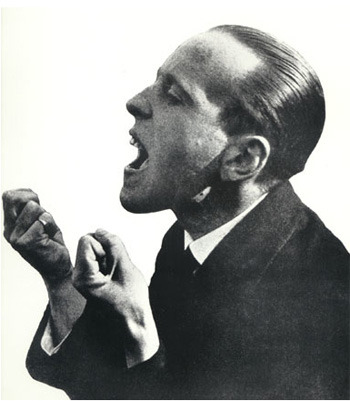

Aleksandr Rodchenko Portrait of German Anti-fascist Photomontage Artist John Heartfiled 1939

“I think that the movements of my brother’s hands, when he is sunk in observation, when he is lost in thought, when he tries to explain something to someone, would produce wonderful futurist pictures, if it were possible to transfer these movements (visually) like temperature or air pressure variations.” Wieland Herzfelde, describing his brother, John Heartfield’s hands.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Research 2.2: Collage approaches

John Heathfield

“A photograph can, by the addition of an unimportant spot of colour, become a photomontage, a work of art…” German Dada & Anti-Fascist Graphic Designer John Heartfield

1. Personal Impression

His work is iconic. Represent the German resistant against one of the cruellest regimes in history. I love his work. I think his work has two different readings, the abstract concept and the current affairs one. What I mean by that. The first time you look at the piece you know what he was trying to warn us about the Nazi regime, the machetes, the blood, the money, the bodies are clear warning sings. The second is the current affair (now historical events), WWII and the holocaust hunt us, we ask ourselves how we got there, how was people capable of doing this, people did not know. He gave us some answers to this.

“A Berlin Saying” by Heartfield

2. Where he finds the images from?

photographs and magazine articles (Heartfield, n.d.)

3. what images do you find more straking?

The political connotation. His images have a vintage feel to it but at the same time, they are timeless. You might not know what this images response to (because Heartfield usually response to current affairs) but you understand the meaning behind the work. You can use his work to represent a lot of other cruel regimes around the word just by changing a few elements.

The picture below is a nice example. When you see the image and read the title you understand that Heartfield is commenting on the horrors of war but when you look at the article behind the image, you can see what he meant specifically and why each element is there. This ability is quite rare. Most of the time artist can achieve one but not both. Or they are abstract and timeless or specific and contemporary.

This is the Salvation They Bring Us! by Heartfield

Julie Cockburn

1. Personal Impression

Perhaps it is the colours or the delicate embroidery, the transformation of a forgotten object into a beautiful new object. Perhaps all those things are the reason I am interested in her work.

2. Where he finds the images from?

They are found objects and textiles.

3. what images do you find more straking?

I am not sure. The colour and the texture are something that normally pull me into a piece of art, but I think that her work is a combination of elements. I also like craftsmanship. I know it is a cliché, but I found handmade objects give me comfort in a cold world and this combine with art is a perfect combination.

4. Relevance in the period that were made? relevance now?

These are contemporary pieces, so the question is more into if the images are relevant now and I think they are. In a society where everything is built to be disposable, that mass production and cheap labour are at the centre of our society progress and the way we perceive ourselves and others. the creation of pieces from recycle materials and handmade process is relevant. It remands us of a different time where everything was unique. Things take time and the last a lifetime.

Hannah Höch

Untitled, From an Ethnographic Museum by Hannah Höch, 1930. Photograph: Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg/Maria Thrun (Cumming 2018).

1. Personal Impression

The disarticulation of the pieces is what is more attractive to me. It take a bit of time to find the narrative.

2. Where she finds the images from?

“spliced together photographs or photographic reproductions she cut from popular magazines, illustrated journals, and fashion publications” (Hirschl, 2014), she also used recycling materials, writing and printing.

3. what images do you find more straking?

It is interesting to see the sense of humour and political satire these pieces have.

4. Relevance in the period that were made? relevance now?

She faced sexism (Hirschl, 2014) (Cumming, 2018) and a condescending attitude by her male counterpart in the dada movement in Germany, so her pieces reflect that reality and evaluate the gender roles in her pieces in a satirical way.

Yes, of course. Women have been battling discrimination, objectification and other forms of dehumanization by a patriarchal society for the last 100 years with some successes, but it is relevant the massage

Hearthfield, J. (1917). Adolf The Superman. Famous Adolf Hitler Portrait. John Heartfield AIZ. [online] John Heartfield Exhibition. Available at: https://www.johnheartfield.com/John-Heartfield-Exhibition/john-heartfield-art/famous-anti-fascist-art/heartfield-posters-aiz/adolf-the-superman-hitler-portrait.

Heartfield, J.J. (n.d.). John Heartfield Biography. [online] john heartfield. Available at: https://www.johnheartfield.com/John-Heartfield-Exhibition/helmut-herzfeld-john-heartfield-life/artist-john-heartfield-biography [Accessed 11 Feb. 2021].

Kimmelman, M. (1993). Review/Art; Hated the Nazis, Loved the Soviets, Created Images to Mock and Admire (Published 1993). The New York Times. [online] 16 Apr. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/1993/04/16/arts/review-art-hated-the-nazis-loved-the-soviets-created-images-to-mock-and-admire.html [Accessed 11 Feb. 2021].

Hirschl Orley, H. (2014). Hannah Höch. [online] The Museum of Modern Art. Available at: https://www.moma.org/artists/2675.

Cumming, L. (2018). Hannah Höch – review. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/jan/13/hannah-hoch-whitechapel-review.

0 notes

Text

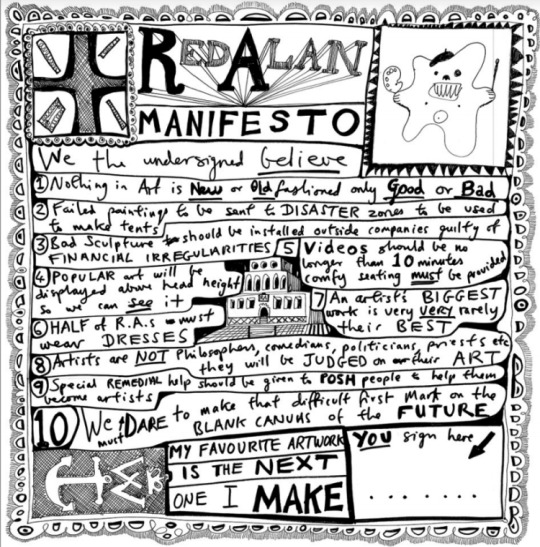

MANIFESTO LAUNCH

Red Alan's Manifesto by Grayson Perry, 2014

Poetry | Political Statement

Possibly Gender Fluid

Documentaries

Write a Manifesto - Create Poster

Manifestos are usually written in a group

Political Ethos

Gender Issues

ASSESS WHAT IS IMPORTANT TO YOU - what do I want to say within my art

A manifesto is a public declaration, often political in nature, of a group or individual’s principles, beliefs, and intended courses of action.

10 game-changing art manifestos

By Harriet Baker (Royal Academy)

Published 10 April 2015

Some time between 1966-76, Richard Diebenkorn wrote ten notes on beginning a painting. Described by the critic John Elderfield as a set of “artistic intentions,” they are a valuable insight into the mind of the artist, revealing some of the ways that Diebenkorn challenged himself in his work. Diebenkorn, of course, was not the first artist to lay out his beliefs. From Joshua Reynolds’s lofty Discourses to the impassioned manifestos of the early 20th-century’s avant- garde, artists have laid out pages of their visions for art, many of which changed the course of art history. And while contemporary artists continue to set their objectives on paper, it is often done with a more wry and humorous touch. The result is a collection of imperfect but fascinating ideas about what art should be.

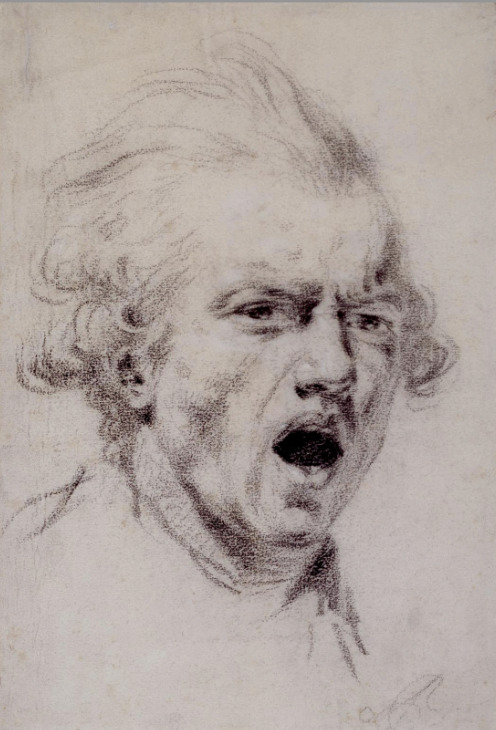

Discourses on Art, Sir Joshua Reynolds,

1769-1790

I wished you to be persuaded, that success in your art depends almost entirely on your own industry; but the industry which I principally recommend, is not the industry of the hands, but of the mind... We may go so far as to assert, that a painter stands in need of more knowledge than is to be picked off his pallet, or collected by looking on his model, whether it be in life or in picture. He can never be a great artist, who is grossly illiterate... He ought to know something concerning the mind, as well as a great deal concerning the body of man.

Sir Joshua Reynolds PRA, Discourses VII, 1769

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Self-Portrait as a Figure of Horror, c.1784

Reynolds Discourses on Art, now considered to be the founding text of British painting theory, elevated art as an activity of the mind, not the hand, and called on painters to imbue their work with much more than simply what they saw in front of them.

The Discourses were very influential, but controversial too; William Blake annotated his copy furiously, noting his “indignation and resentment” at Reynolds’s ideas, while the Pre-Raphaelites accused Reynolds of ignoring the truth in favour of ideal beauty.

ART HISTORY

The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism, FT Marinetti, 1909

1. We intend to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness.

2. Courage, boldness, and rebellion will be the essential elements in our poetry.

3. Up to now, literature has extolled a contemplative stillness, rapture and reverie. We intend to glorify aggressive action, a restive wakefulness, life at the double, the slap and the punching fist.

F.T. Marinetti, 1909

THE FUTURISTS

The Futurists published a huge number of different manifestos, using them to communicate their aesthetic, political, and social ideals. The scale with which the Futurists created and disseminated their manifestos was unprecedented, allowing them to transmit their ideas to a wider audience.

Many Italian Futurists supported Fascism and parallels can be drawn between the two movements. Like the Fascists, the Futurists were strongly patriotic, excited by violence and opposed to parliamentary democracy. When Mussolini took power in 1922 it brought Futurism official acceptance, but, later, this adversely affected many of the artists as they became tainted by association.

The Art of the Manifesto (or Art Manifestos)

By Eulàlia Iglésias

“We want to sing the love of danger, the habit of danger and of temerity.” Thus begins the Futurist Manifesto that Filippo Tommaso Marinetti published in French newspaper Le Figaro on February 20th, 1909.

A spectre haunted European art during the first years of the 20th century. Imbued with the spirit of the new age, fascinated by the technological innovations shown in different fields, and sympathisers of the many social and political revolutions that were arising throughout the continent, a generation of youngsters decided to break with the academic legacy and canon in force since the Renaissance to create art more in harmony with their own times: the avant-gardists. And the way to proclaim this new art was through the use of manifestos.

Up to Marinetti’s, manifestos had been circumscribed to the political sphere. By putting pen to

paper to define their intentions and affinities, these young artists declared the pragmatic character of the avant-garde. They created and destroyed in order to show their rejection of tradition and their longing to change life and transform society. The term ‘avant-garde’ has a clear military connotation, and manifestos were a war declaration of sorts against the world as they knew it.

Futurism was an Italian art movement that aimed to capture the dynamism and energy of the modern world in art. The Futurists were well versed in the latest developments in science and philosophy, and particularly fascinated with aviation and cinematography.

Futurist artists denounced the past, as they felt the weight of past cultures was extremely oppressive, particularly in Italy.

The Futurists instead proposed an art that celebrated modernity and its industry and technology.

Elasticity (detail), (1912), Umberto Boccioni.

Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), Umberto Boccioni

Giacomo Balla Abstract Speed, The Car has Passed 1913

Mario Sironi’s 1918 drawing ‘Uomo Nuovo’ (New Man)

Jacques-Henri Lartigue, 1913

László Moholy-Nagy Light Prop for an Electric Stage

László Moholy-Nagy- Dual Form with Chromium Rods

As early as 1922, László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946) began to make metal sculptures. He believed that new materials called for a new kind of art, and metal was appealing for its connection to industry and modern machinery.

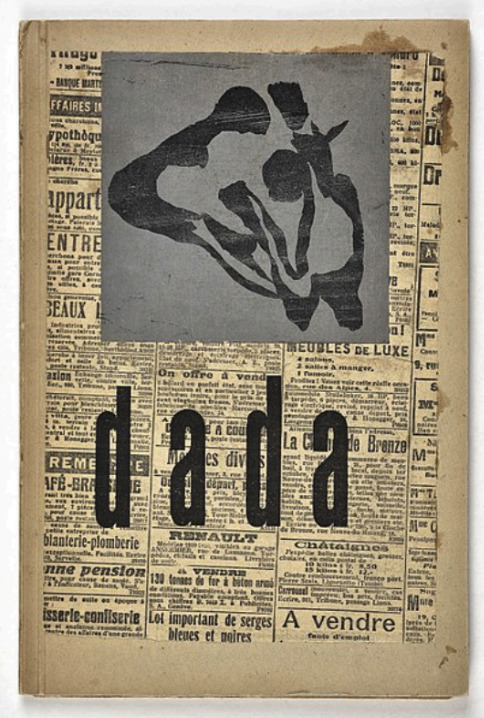

Dada manifesto, Tristan Tzara, 1918

Tristan Tzara was a French poet and essayist, famous for founding Dada in Zurich in 1916 and writing the founding manifesto.

Spanning a wide variety of mediums and forms – from photography and performance art to painting and collage – the Dada movement was born out of a reaction against nationalism and rationalism, which these artists believed to have caused the First World War.

Though the movement was far from coherent, its key figures – including Hans Arp, Kurt Schwitters and Hannah Hoch – produced highly political and irreverent works influenced by Cubism, Futurism and Constructivism.

Jean Hans Arp, bois gravé et collage pour la couverture de Dada 4-5, 1919

Hannah Höch

Known for her incisively political collage and photomontage works, Dada artist Hannah Höch appropriated and rearranged images and text from the mass media to critique the failings of the Weimar German Government.

Höch drew inspiration from the collage work of Pablo Picasso and fellow Dada exponent Kurt Schwitters, and her own compositions share with those artists a similarly dynamic and layered style.

She rejected the German government, but often focused her criticism more narrowly on gender issues, and is recognized as a pioneering feminist artist for works such as Das schöne Mädchen (The Beautiful Girl), (1920), an evocative visual reaction to the birth of industrial advertising and ideals of beauty it furthered.

Hannah Höch, Das schöne Mädchen (The Beautiful Girl), (1920)

Hannah Höch, Für ein Fest gemacht (Made for a Party) 1936

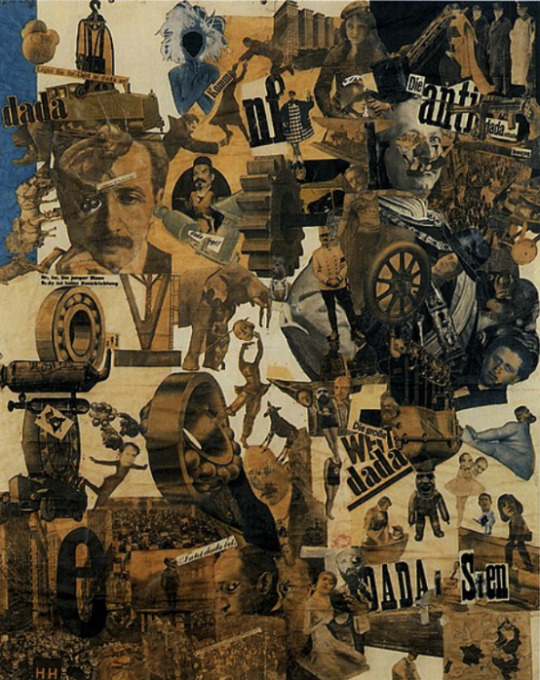

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, 1919

Man Ray, Rayograph, 1922

Man Ray. Untitled Rayograph, 1922.

Surrealism was an artistic, intellectual, and literary movement led by poet André Breton from 1924 through World War II. The Surrealists sought to overthrow the oppressive rules of modern society by demolishing its backbone of rational thought. To do so, they attempted to tap into the “superior reality” of the subconscious mind. “Completely against the tide,” said Breton, “in a violent reaction against the impoverishment and sterility of thought processes that resulted from centuries of rationalism, we turned toward the marvellous and advocated it unconditionally”.

Many of the tenets of Surrealism, including an emphasis on automatism, experimental uses of language, and found objects, had been present to some degree in the Dada movement that preceded it. However, the Surrealists systematized these strategies within the framework of psychologist Sigmund Freud’s theories on dreams and the subconscious mind.

In his 1924 Surrealist Manifesto, Breton defined Surrealism as: “Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express...the actual functioning of thought...in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.”

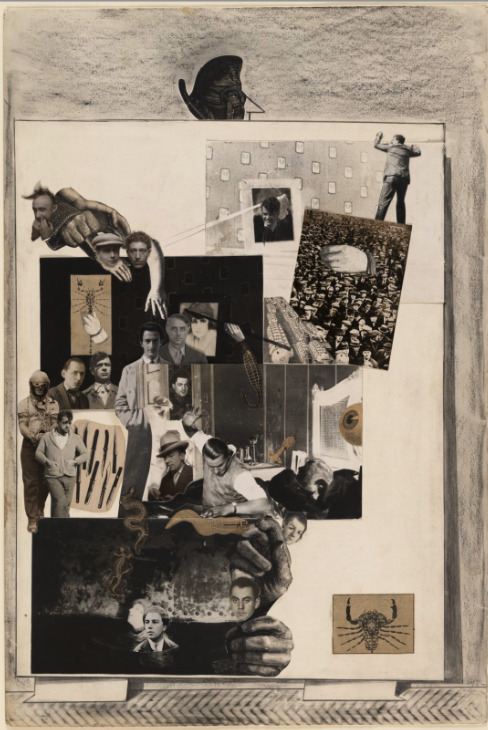

Max Ernst. Loplop Introduces Members of the Surrealist Group. 1931

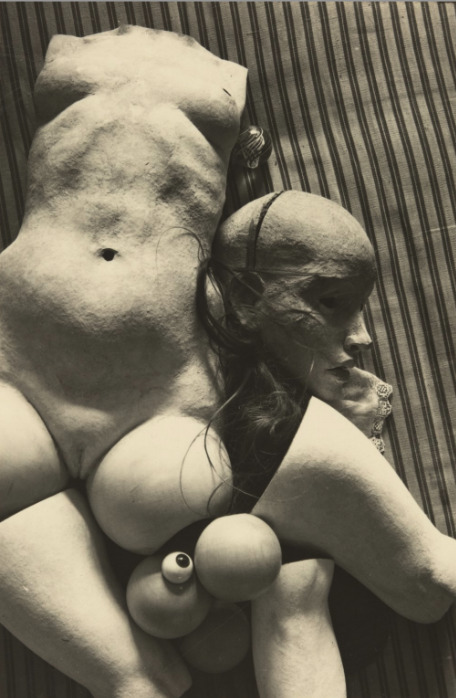

Hans Bellmer. Plate from La Poupée. 1936

Lee Miller, Portrait of Space, Nr Siwa, Egypt, 1937.

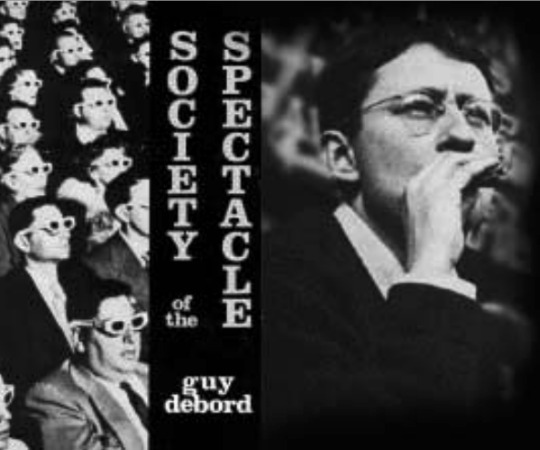

SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL (IS)

Were a revolutionary alliance of European avant- garde artists, writers and poets formed at a conference in Italy in 1957.

The Situationist International brought together experimental poetry, avant-garde art, and radical social criticism to explore new techniques of engagement in cultural protest and revolutionary praxis.

When the Situationist International was first formed, it had a predominantly artistic focus; Gradually, however, that focus shifted more towards revolutionary and political theory.

It was anti-capitalist, and left-leaning, but was also committed to the disruption of the hegemonic politics of Europe in the late 20th century through artistic praxis as well as political agitation. Although eventually fracturing, SI provided a blueprint for rebels and artistic dissidents still followed today.

The notion of "Spectacle", originally outlined by Guy Debord in various Situationist writings, is key to understanding both the conceptual underpinnings of SI and its enduring legacy. The idea of a permanently distracting and preoccupying spectacle, which obfuscates the oppressive nature of capitalism, has been adopted by artists, activists, critics and academics as a key philosophical concept in the current moment of late capitalism.

Although a collaborative and supposedly open movement, SI adhered relatively rigidly to the direction of Guy Debord and the key ideas and artistic strategies he identified. This is somewhat ironic, as it was actually the wider dissemination and public take up of their ideas that ensured their longevity long after the group fragmented.

Asger Jorn experimented with spontaneous line and semi- figurative representation in paintings he called “modifications.” His works attempted to change people’s behaviours towards art, writing, and the spaces they lived in.

“A creative train of thought is set off by the unexpected, the unknown, the accidental, the disorderly, the absurd, the impossible”

Asger Jorn

Jorn was one of the few artists who identified themselves as Situationists during the main period of the movement’s activity but the political rhetoric surrounding the movement and it’s manifesto influenced the work of many future artists.

Asger Jorn, Modification with Brittany Woman, 1962.

Situationism as an art movement did not produce too many artworks as a matter of fact, with the exception of Asger Jorn, the movement’s output is next to none.

However, Situationism is credited with providing some of the most revolutionary theories at the time, concepts that heavily impacted the art scenes for decades.

Many of their game-changing ideas can still be found in today’s contemporary art.

The political background of SI influenced the evolution of music, Punk in particular. Also the political aspect of the movements is recorded as being instrumental in the origins of street art (graffiti), performance, and installation art.

Protests in Paris during May ’68

Peter Kennard, Haywain with Cruise Missiles 1981 & Defended to Death 1983

“Never Again’, Peter Kennard

Crushed Missile (1980) by Peter Kennard

Krzysztof Wodiczko, Hirschhorn Museum Washington DC 2018 and Projection on to South Africa House 1985

The Guerilla Girls, 1985-90

In 1984, a group of anonymous women, wearing gorilla masks, picketed the Museum of Modern Art in New York. MoMA was opening a show which purported to be a definitive survey of contemporary art, and yet out of the 169 artists featured in the show, only 13 were female. Since their inception, the group have worked to expose the under- representation of women in the art world by targeting galleries, art dealers and critics. Their manifesto comes in the form of their famous slogan artworks.

Guerrilla Girls, no title, 1985-90

Since their inception in 1984 the Guerrilla Girls have been working to expose sexual and racial discrimination in the art world, particularly in New York, and in the wider cultural arena.

The group’s members protect their identities by wearing gorilla masks in public and by assuming pseudonyms taken from such deceased famous female figures as the writer Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) and the artist Frida Kahlo (1907-54).

Guerrilla Girls, The Advantages of Being A Woman Artist, 1988

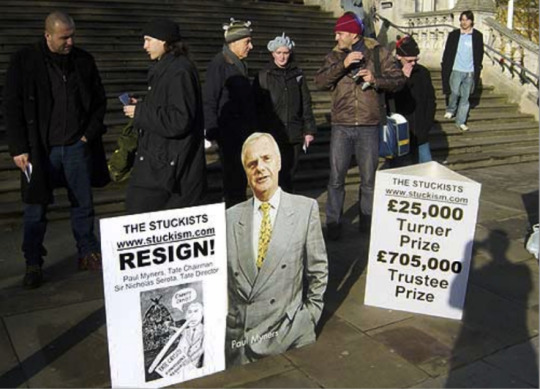

The Stuckist Manifesto, 1999

Established in 1999, the British group the The Stuckists proclaimed themselves to be “Against conceptualism, hedonism and the cult of the ego-artist.” The movement was formed by Billy Childish and Charles Thomson to celebrate and promote figurative painting in a reaction to the proliferation of conceptual art. Every year, the Stuckists famously demonstrate outside Tate Britain as the winner of the Turner Prize is announced.

1. Stuckism is the quest for authenticity.

2. Painting is the medium of self-discovery.

3. Stuckism proposes a model of art which is holistic.

4. Artists who don’t paint aren’t artists.

5. Art that has to be in a gallery to be art isn’t art.

The Stuckists, 1999

"Your paintings are stuck, you are stuck! Stuck! Stuck! Stuck!”

Tracey Emin

Billy Childish, Hand on Face, oil on canvas, 2000

Possibly the best-known recent example of an artistic manifesto in the digital age is that of The Stuckists – an art movement established in the UK 1999, which has now grown to at least 233 groups in 52 countries.

Its founding members, Billy Childish and Charles Thomson, rejected conceptual art, instead advocating a return to figurative paintings with ‘spiritual value’.

The success of this movement (members of which continue to demonstrate against The Turner Prize at London’s Tate Britain every year), has spurred other contemporary artists into creating their own manifestos. For example, The Resurrection Of Beauty, written by philosopher and photographer, Mark Miremont, calls for a rejection of what he describes as “The sarcastic relativism of dada”.

Outside the Turner Prize, Tate Britain, 2005: Stuckists demonstrate against the purchase of Chris Ofili's The Upper Room. The cutout is Tate chairman Paul Myners.

Manifestos within Photography

Brett Weston, Garden Apartment, New York

Group f/64

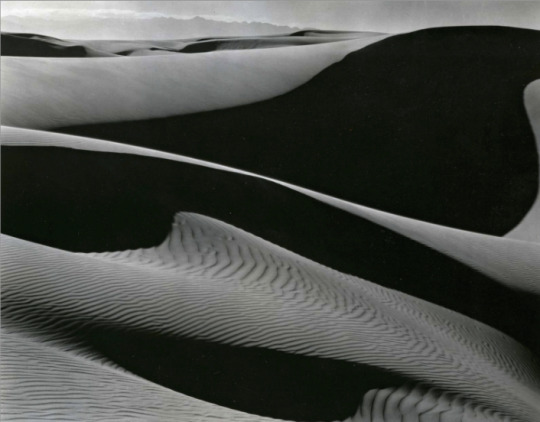

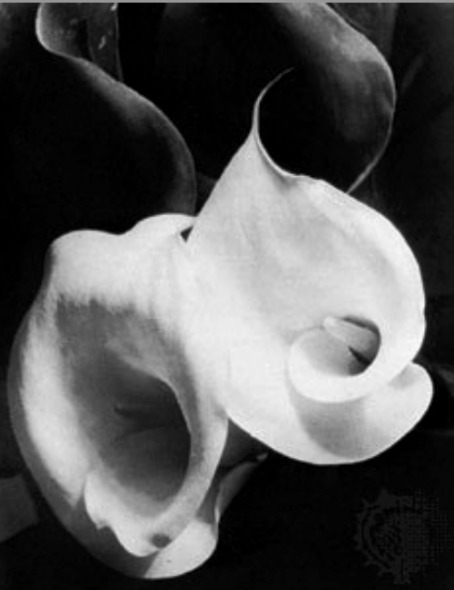

Formed in 1932, Group f/64 this group of so-called 'straight' photographers focused on the clarity and sharp definition of the un-manipulated photographic image. Committed to a practice of "pure photography",

Group f/64 encouraged the use of a large-format view camera in order to produce grain-free, sharply-detailed, high value contrast photographs. Group f/64 mounted a revolt against the dominant fashion within the art of photography which was to ape the painterly and graphic techniques associated with Bay Area Pictorialism. The members' preference was for a style of art photography that would fully promote the camera's unique mechanical qualities.

The original 11 members of Group f.64 were Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston, Willard Van Dyke, Henry Swift, John Paul Edwards, Brett Weston, Consuelo Kanaga, Alma Lavenson, Sonya Noskowiak, and Preston Holder.

"Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form." —Group f/64 Manifesto, August 1932

Dunes, Oceano, Edward Weston, 1936

Half Dome, Apple Orchard, Yosemite, Ansel Adams, 1933.

Two Callas, Circa 1925, Imogen Cunningham

Group f/64 displayed the following manifesto at their 1932 exhibit:

The name of this Group is derived from a diaphragm number of the photographic lens. It signifies to a large extent the qualities of clearness and definition of the photographic image which is an important element in the work of members of this Group. The chief object of the Group is to present in frequent shows what it considers the best contemporary photography of the West; in addition to the showing of the work of its members, it will include prints from other photographers who evidence tendencies in their work similar to that of the Group.

Group f/64 is not pretending to cover the entire spectrum of photography or to indicate through its selection of members any deprecating opinion of the photographers who are not included in its shows. There are great number of serious workers in photography whose style and technique does not relate to the metier of the Group.

Group f/64 limits its members and invitational names to those workers who are striving to define photography as an art form by simple and direct presentation through purely photographic methods. The Group will show no work at any time that does not conform to its standards of pure photography. Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form. The production of the "Pictorialist," on the other hand, indicates a devotion to principles of art which are directly related to painting and the graphic arts.

The members of Group f/64 believe that photography, as an art form, must develop along lines defined by the actualities and limitations of the photographic medium, and must always remain independent of ideological conventions of art and aesthetics that are reminiscent of a period and culture antedating the growth of the medium itself.

The Group will appreciate information regarding any serious work in photography that has escaped its attention, and is favourable towards establishing itself as a Forum of Modern Photography.

‘Magnum is a community of thought, a shared human quality, a curiosity about what is going on in the world, a respect for what is going on and a desire to transcribe it visually.’

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare, Henri Cartier-Bresson, 1932

n 1947, following the aftermath of the Second World War, four pioneering photographers founded a now legendary alliance.

Combining an extraordinary range of individual styles into one powerful collaboration, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, George Rodger and David Seymour started, the most important artists’ cooperative ever created: The Magnum Photos agency.

Robert Capa US troops assault Omaha Beach during the D-Day landings (first assault), 1944.

“Capa was the boss because, for one thing, he kept on the lookout for stories for all the Magnum photographers. But equally vital were his experience, generosity, connections, aggressiveness, and the vision he had for Magnum, which kept us going. Since few of us were married, we had much time to spend together. We talked a lot, but rarely about photography. Our discussions were more often about politics or philosophy or racehorses, pretty girls, and money. We constantly looked at each other’s work, and criticism could be tough if the work did not measure up to the expected standard.”

Inge Morath

Magnum Photos represents some of the world’s most renowned photographers, maintaining its founding ideals and idiosyncratic mix of journalist, artist and storyteller. Our photographers share a vision to chronicle world events, people, places and culture with a powerful narrative that defies convention, shatters the status quo, redefines history and transforms lives. Magnum has documented most of the world’s major events and personalities since the 1930s; covering industry, society and people, places of interest, politics and news events, disasters and conflict.

Marc Riboud

An American young girl, Jan Rose Kasmire, confronts the American National Guard out the Pentagon durning the 1967 anti-Vietman march. (1967)

In planning the weekly news magazine, publisher Henry Luce circulated a confidential prospectus, within Time Inc. in 1936, which described his vision for the new ‘'Life'' magazine, and what he viewed as its unique purpose. ''Life'' magazine was to be the first publication, with a focus on photographs, that enabled the American public: “To see life; to see the world; to eyewitness great events; to watch the faces of the poor and the gestures of the proud; to see strange things — machines, armies, multitudes, shadows in the jungle and on the moon; to see man’s work — his paintings, towers and discoveries; to see things thousands of miles away, things hidden behind walls and within rooms, things dangerous to come to; the women that men love and many children; to see and take pleasure in seeing; to see and be amazed; to see and be instructed…”

On November 23, 1936, the first issue of the pictorial magazine Life is published, featuring the work of photographer Margaret Bourke-White.

Life was an overwhelming success in its first year of publication. Almost overnight, it changed the way people looked at the world by changing the way people could look at the world.

What the editors got from Bourke-White was a human document of American Frontier life & the photo essay format was born.

Photographer Margaret Bourke-White had been dispatched to the Northwest to photograph the multimillion dollar projects of the Columbia River Basin. What the editors expected were construction pictures as only Bourke-White could take them. What the editors got was a human document of American frontier life which, to them at least, was a revelation.”

(time.com)

Workers on Montana’s Fort Peck Dam blow off steam at night, 1936

Luce, and Life magazine gave photographers the opportunity to delve into the stories of extraordinary people with the magazine’s photo essay series format which endured for years.

Across a dozen pages, and featuring more than 20 of the great W. Eugene Smith’ pictures, the story of a tireless South Carolina nurse and midwife names Made Callen opened a window on a world that, surely, countless LIFE reader had never seen - and perhaps, had never even imagined.

Cindy Sherman Interview 2019

What are your three top tips for becoming an artist?

Try to forget everything you learned about making art. Find a group of like-minded artists or creative people to hang out with. Take chances with what you do, make things that no one but

you will ever see, unless it turns out so good you want to share it.

Why do you make art?

It’s my life and it’s what I’m most passionate about. And it’s fun!

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever been given?

Find inspiration in reading

Cindy Sherman, Untitled A 1967

Anthropcene

Anthropocene is a multidisciplinary body of work by Edward Burtynsky, Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier, which includes a photobook, a museum exhibition, a feature-length documentary film, and an interactive educational website.

The project’s starting point is the research of the Anthropocene Working Group, an international body of scientists who argue that the Holocene epoch ended around 1950, and that we have officially entered the Anthropocene in recognition of profound and lasting human changes to the Earth’s system.

The Holocene is the name given to the last 11,700 years of the Earths history- the time since the end of the last ‘ice age.’ Since then, there have been small-scale climate shifts notably the ‘Little Ice Age’ between about 1200 and 1700 A.D but in general, the Holocene has been a relatively warm period in between ice ages.

My earliest understanding of deep time and our relationship to the geological history of the planet came from my passion for being in nature.

Coal Mine #1, North Rhine, Westphalia, Germany, 2015

As a collaborative group, Jennifer, Nick and I believe that an experiential, immersive engagement with our work can shift the consciousness of those who engage with it, helping to nurture a growing environmental debate. We hope to bring our audience to an awareness of the normally unseen result of civilization’s cumulative impact upon the planet.

This is what propels us to continue making the work. We feel that by describing the problem vividly, by being revelatory and not accusatory, we can help spur a broader conversation about viable solutions.

We hope that, through our contribution, today’s generation will be inspired to carry the momentum of this discussion forward, so that succeeding generations may continue to experience the wonder and magic of what life, and living on Earth, has to offer”

Edward Burtynsky

Lithium Mines #1, Salt Flats, Atacama Desert, Chile, 2017

Gregory Crewdson is a photographer, but he calls himself a storyteller. He has spoken of his belief that “every artist has one central story to tell,” and that the artist’s work is “to tell and retell that story over and over again,” to deepen and challenge its themes. True to this, Crewdson’s most recent body of work, Cathedral of the Pines, shares the aesthetic that has defined his career”

Sylvie McNamara , Paris Review, 2016

The Shed, 2013, Cathedral of the Pines, Gregory Crewdson

The writers that are still influential to me are the writers that shaped me as I was coming of age as a young photographer. The ones I feel most aligned with would be, first and foremost, Raymond Carver and John Cheever. That brand of American realism. There are many more, but those are the ones I would say really shaped me in terms of storytelling.

Above all it’s their exploration of the ordinary, the familiar. I think with Carver in particular it’s the idea that you can find this sense of drama in a small domestic event, and it can be magnified and made transformative in some way. I see my pictures as being very much aligned with that, taking a familiar situation and making it dramatic, in my case through gesture and colour and light. And then, of course, giving the impression that everyday life is unsettled in some way, or made mysterious or wondrous somehow. I guess the story I most identify with is Cheever’s “The Swimmer.”

It’s realism meeting a psychological strangeness—it’s all located in a sort of familiar landscape and terrain, but it’s transformed. The irrational activity of swimming home through the neighbours' swimming pools is similar, in my mind, to the act of making the dirt piles in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. It’s that same attempt to find meaning in a world that feels alien, trying to make sense of a world that you feel disconnected from.

Gregory Crewdson

What is the purpose of an Artistic Manifesto in the 21st Century?

The Futurist manifesto was to provide the blueprint for many subsequent art movements, including the Dadaists, Surrealists and Situationists.

The document, published first in Italian newspaper Gazzetta dell’Emilia before being translated and appearing in French tabloid, Le Figaro, outlined the aims of this emerging art and social movement in dynamic, bold, revolutionary and often incendiary language.

Upon reading it, no-one was left in any doubt as to Futurism’s rejection of the past and its celebration of industry, precision, speed, youth and violence. As part of its vision for a better future, the manifesto advocated the modernization and complete cultural rejuvenation of Italy.

Since then, the artistic manifesto has lived on, even though other ways of broadcasting ideas began to become more prominent. In the 21st century, and the manifesto is enjoying something of a renaissance among artists, thanks in no small part to the advent of the internet and the opportunity of reaching large numbers of people more easily than ever before.

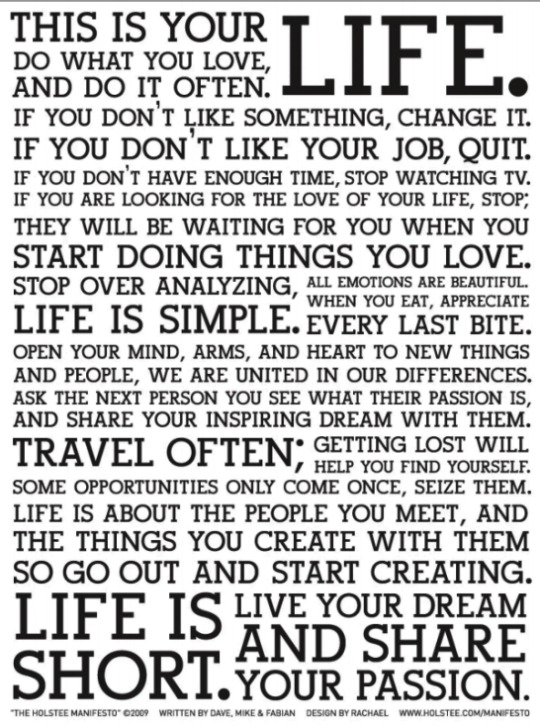

The Holstee Manifesto

The manifesto began as the guiding ideas behind Dave and Mike Radparvar's company, Holstee, which was launched in the summer of 2009 after quitting their corporate jobs. The brothers, along with their friend Fabian Pfortmüller, wanted to start a business that gave back and incorporated their social and environmental values.

To be sure, they were clear about what they were doing with their new company when they wrote the manifesto and published it on their site.

“Mike and I sat down with our best friend and co-founder, Fabian, to reflect and write down why we were starting Holstee. We sat on the steps of Union Square in New York City and, together, defined what success would look like. Not the typical kind of success — based on extrinsic motivators like wealth or status — but a different kind, based intrinsic motivators like putting energy into things that feed our soul and spending time with the people we care about.

Dave Radparvar.

The document has been viewed online more than 50 million time and translated into 12 languages. When Holstee turned the message into a $25 poster - printed on recycled paper, it became one of the company’s top sellers.

The Holstee Manifesto - Life Cycle

youtube

WRITING YOUR OWN MANIFESTO

A manifesto is a declaration of aims and policy

This task asks you to articulate and commit to a statement regarding your work in that arts and its intent

Ask yourself the question, ‘What do you believe?’

0 notes

Text

Fourcorners Gallery till Feb 8th https://www.fourcornersfilm.co.uk/another-eye

https://www.fourcornersfilm.co.uk/another-eye

Biography from https://www.johnheartfield.com/John-Heartfield-Exhibition/helmut-herzfeld-john-heartfield-life/artist-john-heartfield-biography

Bertolt Brecht: “John Heartfield is one of the most important European artists.” John Heartfield is known:

As the founder of modern photomontage (photo montage), a form of collage. Living in Berlin, he risked his life to used his art “as a weapon” to combat fascist propaganda, Adolf Hitler, and The Third Reich. As the inventor of 3-D book dust jackets, book covers that told a “story” from the front cover of the book to the back. For his groundbreaking use of typography as a graphic design For his innovative theater collaborations with Bertolt Brecht. Work that lead the world-famous playright and composer to develop a new form of theater. German artist John Heartfield is a clear example of artistic genius combined with a heroism going far beyond the required courage of any great artist.

John Heartfield Biography John Heartfield’s Art Saved Lives

Heartfield’s anti-fascist anti-Nazi art became famous on both sides of the Atlantic before and during WW2. Heartfield used fascists’ own words and images against them. His message was clear: “You must oppose this madness, escape, or do both.”

John Heartfield Biography The Photomontages Of The Nazi Period

A John Heartfield biography must begin by highlighting the years when Heartfield’s genius reached its zenith. His famous political art, which he labeled “photomontages” expressed his hatred of fascists, especially Adolf Hitler and The Third Reich. From 1930 to 1938, Heartfield designed 240 pieces of anti-Nazi art for the AIZ [Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung], a magazine published by the New German Press, which was run by the political activist Willi Münzenberg. The AIZ had a significant readership in Weimar-era Germany. It may easily have had the second highest circulation in Germany in the early nineteen thirties. After the National Socialists took control, the AIZ was published for German readers in Czechoslovakia, Austria, Switzerland, and Eastern France.

To fully understand a John Heartfield biography, it’s vital to remember his artistic courage was equal to his physical courage. Heartfield was a resident of Berlin until 1933. His vehemently anti-fascist collages appeared on the covers of the AIZ on newsstands throughout the city. This is a vital point. From 1930-1933, Heartfield’s scathing anti-Nazi montages were clearly visible on Berlin Streets. Supporters also pasted posters of his montages on walls and surfaces for any passersby to see.

Although he shined in several other mediums, such as stage sets and book covers, there’s no doubt that Heartfield is best known for the satiric political montages he created during the 1930s to expose the insanity of Adolf Hitler, Herman Göring, and the entire Nazi philosophy. To battle the Third Reich with art, Heartfield created some of his most famous montages.

Adolf der Übermensch and Goering: der Henker are two examples of photo montages Heartfield produced and had widely distributed while he remained under constant threat of assassination by Hitler’s Third Reich.

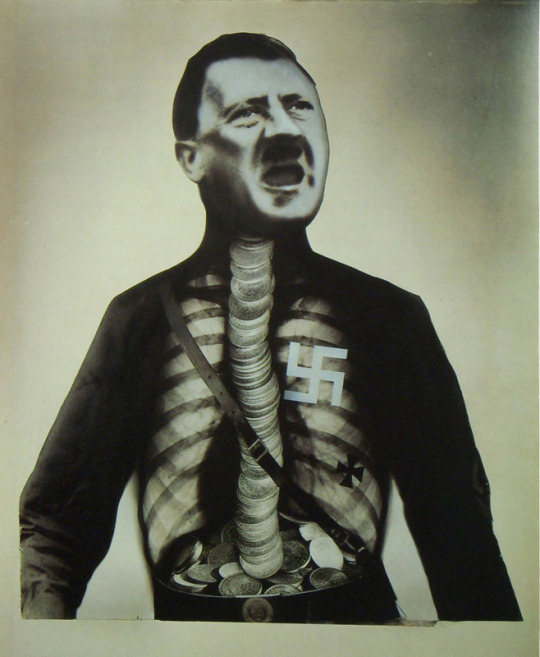

This 1932 John Heartfield portrait of Adolf Hitler In Adolf The Superman: Swallows Gold and spouts Junk appeared all over Berlin corners placed in newsstands in 1932 on the cover of the popular AIZ magazine. Heartfield used an X-ray to show gold coins in the Führer’s throat leading to a pile in his stomach. Hitler changes his supporter’s gold to lies.

Adolf Der Übermensch: Schluckt Gold und redet Blech (Adolf The Superman: Swallows Gold and spouts Junk)

The famous political artist who created famous WW II anti-Nazi art against Adolf Hitler

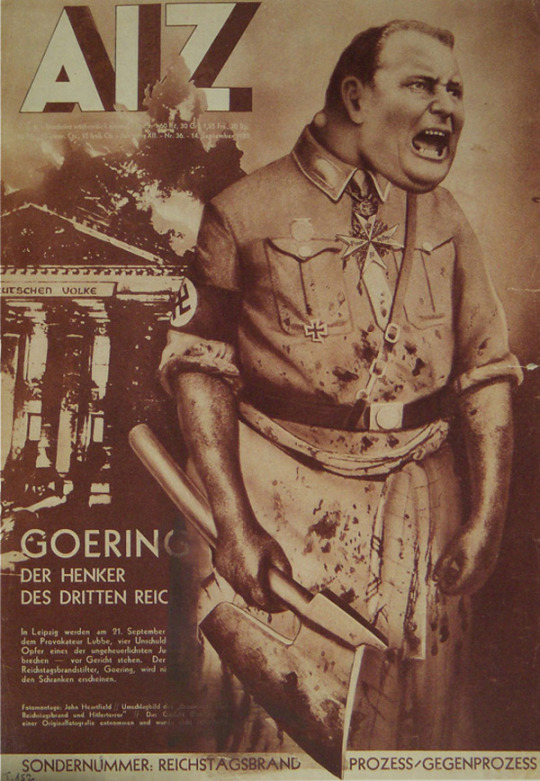

In the photomontage Göring: The Executioner of the Third Reich, Hitler’s designated successor is depicted as a bloody butcher. In 1934, Heartfield created this famous AIZ cover that exposed Hermann Goering as The Third Reich’s executioner. Goering had blamed the Reichstag fire that helped Hitler seize power as the work of Jews and communists.

Göring: Der Henker des Dritten Reichs (Goering: The Executioner of the Third Reich)

AIZ Magazine Cover, Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1933 The artist who created famous WW II anti-Nazi art

From 1930-1938, he created an astounding 240 photomontages for covers of the AIZ magazine (circulation around 300,000 to 500,000 at its height). These 240 brilliant works of art were a complete description of the rise of fascism in the 20th century.

Heartfield’s AIZ covers appeared on street corners all over Adolf Hitler’s Berlin. His “Photomontages of the Nazi Period” are a feat of political art that has never been duplicated.

Heartfield lived in Berlin until Easter Sunday, April 1933, when he narrowly escaped assassination by the SS. He fled across the Sudeten Mountains to Czechoslovakia where he rose to number-five on the Gestapo’s most wanted list.

Below is an excerpt From David King’s book, John Heartfield, The Devastating Power Of Laughter. It describes the 1933 Easter Sunday Evening when Hitler’s jackboots came for John Heartfield.

“Berlin, April 14, 1933: They came for him in the night. The paramilitary SS burst into the apartment block and headed straight for the raised ground floor studio where John Heartfield was in the middle of packing up his artwork, knowing that his only chance left of survival was a life in exile; he was on their most wanted list. Hearing them dislocating his heavy wooden door, he dived through his french windows and leapt over the balcony into the darkness. He landed badly and sprained his ankle.

The Nazis made a flashlight sweep search of the darkened courtyard below yet failed to focus on an old metal bin in the far corner on which were displayed some enamel signs, the sort that advertise motor oil, or soap, or an aperitif. Under its battered lid, one of Hitler’s greatest enemies, far from having vanished into the ether, crouched in torment, squashed in a box full of the local residents’ garbage. For the next seven hours he hid there, toughing it out as he heard the nightmare sounds of the barbarians ransacking his studio and destroying his work.

When the raid was over, Heartfield quietly and unobtrusively opened the lid, climbed out of the bin, exited the courtyard and began his nerve-racking flight to Prague. Germany was now enemy territory, there was a high price on his head and he had nothing.”

After his narrow escape from the SS, Heartfield walked around the Sudeten Mountains to Czechoslovakia.

[Below: John Heartfield In Mountain Gear. Credit: John J Heartfield Collection.]

The artist persecuted by The Nazis

Heartfield had been beaten by Hitler’s supporter’s and thrown from a streetcar in Berlin. The artist who openly attacked Adolf Hitler and The Nazi Party while living in Berlin was five-foot-two inches tall, with red hair and blue eyes. His “weapon” was his imagination, scissors, glue pots, dabs of paint, and stacks of photographs and magazine articles. He insisted his montages contained both literal and ethical truth.

From his early work as fledging painter to his embrace of Dada to the anti-fascist montages that made him a Nazi target, Heartfield’s life and work was a profile in courage.

Forced to flee Nazi Germany a step ahead of the SS, Heartfield attacked the Nazi Party from Prague.

You can find more of Heartfield’s collages in ART AS A WEAPON has more of John Heartfield’s anti-fascist collages with historical perspective.

John Heartfield Biography The Frail Artist Who Stood Up To Hitler

Heartfield was born into poverty June 19, 1891 in Berlin-Schmargendorf. He was named “Helmut Franz Josef Herzfeld.” The photo above of a young Helmut Herzfeld with a moustache was taken in 1912. Under the photo at the top of this page is a scan of what Herzfeld wrote on its back [Credit: John J Heartfield Collection].

When he was eight, Heartfield’s parents abandoned him, his younger brother, Wieland, and their two even younger sisters, Charlotte and Hertha, in a cabin in the woods. The children were separated and raised in a series of foster homes. Throughout his life, Heartfield maintained a close relationship with his brother, Wieland. In 1913, Wieland Herzfeld also changed his name, less dramatically to “Wieland Herzfelde.”

It was in 1916, while he was living in Berlin, that Herzfeld became disgusted with the shouts of “God Punish England!” that were so common in the streets of the city. As a protest against the anti-British fervor sweeping Germany, he informally changed his name from Helmut Herzfeld to John Heartfield to become, as David King later described him, “the greatest political artist and graphic designer of the twentieth century.”

It was not until August 27, 1964, that his name was legally changed to John Heartfield.

In 1912, after studying arts and crafts in Munich and Berlin, he found work as a commercial artist. From the beginning, Heartfield was infused with a passionate belief that the purpose of art was not to glorify the artist, but to serve the common good.

In 1916, Heartfield met the eccentric genius, George Grosz. Shortly afterwards, Heartfield destroyed all his paintings [mainly landscapes] except one entitled, The Cottage In The Woods.

Grosz had opened his eyes. Heartfield saw his oil paintings did not reflect his passion for honesty and change. He joined Berlin Club Dada in 1917 and became a central figure in the German Dada art movement. Dada has had a profound effect upon culture, advertising, politics, and society. Early one morning in 1916, Heartfield and George Grosz experimented with pasting pictures together. From this exercise grew Heartfield’s lifetime obsession with “photomontage.”

In 1917, John Heartfield founded the Malik-Verlag publishing house in Berlin. At that time, his beloved brother, Wieland, was serving near the front. The brothers were soon to become partners in Malik-Verlag, with John being responsible for the majority of the graphics.

Heartfield invented the concept of three-dimensional wrap-around book dust jackets. The book dust jackets told a story from the front cover to the back. There’s speculation that Malik-Verlag sold more publications because of Heartfield’s covers than the actual content of the books.

In 1920, Heartfield helped organize the Erste Internationale Dada-Messe [First International Dada Fair] in Berlin. Dadaists were the young lions of the German art scene, rebels who often disrupted public art gatherings and made fun of the participants. They labeled traditional art trivial and bourgeois. Heartfield was a vital member of a circle of German titans that included Hannah Höch, George Grosz, Kurt Schwitters, Richard Huelsenbeck, Raoul Hausmann, and others.

During the 1920s, Heartfield had produced a great number of photo montages for Malik-Verlag Publishing. He created groundbreaking dust jackets for books by Upton Sinclair, Kurt Tucholsky, and many other progressive writers.

In January of 1918, Heartfield joined the newly founded German Communist Party (KPD). The KPD, eventually blamed by the Nazis for the burning of the Reichstag, was the only serious political threat to the rise of Adolf Hitler and The Third Reich. From many of his montages, it is clear that Heartfield blamed the greed of capitalists, especially those that manufactured steel and munitions, for the horrors he had witnessed firsthand during World War I.

It is essential to note that the vast majority of his work demonstrates that Heartfield was a devoted pacifist. CURATOR’S NOTE: My own conversations with my grandfather made it clear to me that he never supported violence in any form. He had faith in people and the truth. He was certain if he brought the two together the result would be a better life for all.

John Heartfield Biography Artistic Genius In The Weimar Republic

The work of Weimar Republic artists, writers, composers, and playwrights had a profound effect upon Heartfield. He, in turn, deeply influenced their work. His theater sets were vital elements in the early works of Bertolt Brecht and Erwin Piscator.

The Alienation Effect [Verfremdungs-effekt] Heartfield played a major role in helping Brecht to realize the concept of the “Alienation Effect” [Verfremdungs-effekt]. The playwright used Heartfield’s simple props and stark stage set. Heartfield’s streetcar broke down one night on the way to the theater. He had to carry his screens for the Brecht’s play through the streets. He arrived after the play had begun. Brecht stopped the play and asked the audience to vote on whether Heartfield should be allowed to put up his sets.

Brecht developed this technique to remind spectators that they were experiencing an enactment of reality and not reality itself. Brecht interrupted his plays at key junctures to let the audience to be part of the action and not lose themselves in it. It’s a form of theatre that continued through decades in shows such as those by The Living Theater and Joe Papp’s Shakespeare productions.

The “Engineer” Heartfield Heartfield preferred reality to artistic pretension. While he referred to himself as a “monteur,” he preferred the title “engineer.” A George Grosz painting The Engineer Heartfield hangs in MOMA, The Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Although he did not wish to be labeled an artist, Heartfield had a full measure of an artist’s passion. His Dada contemporaries tied him to a chair and enraged him just to experience the unbridled intensity of his emotions. John Heartfield Biography. Club Dada Founder

John Heartfield Biography A Fighter For World Peace

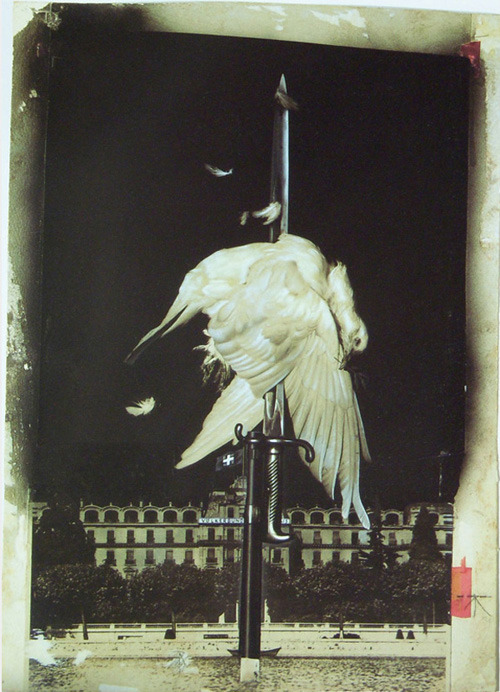

One of Heartfield’s most famous montages, The Meaning of Geneva, Where Capital Lives, There Can Be No Peace!, shows a dove of peace impaled on a blood-soaked bayonet in front of the League of Nations, where the cross of the Swiss flag has morphed into a swastika. John Heartfield’s love of all animals and nature is well documented. This image can be considered an especially deep emotional expression.

Der Sinn von Genf The Meaning of Geneva AIZ Cover, Berlin, Germany, 1932 John Heartfield Biography. Most famous political art Never Again! dove on bayonet

You can learn more about this montage and many others, along with historical perspective, in the ART AS A WEAPON section of the exhibition.

Heartfield’s artistic output was enormous and widely display. It was through rotogravure—an engraving process whereby pictures, designs, and words are engraved into the printing plate or printing cylinder—that he was able to reach this audience he coveted.

CURATOR’S NOTE: I’m certain my grandfather would be pleased and fascinated to see his work reproduced throughout the Internet and on this Digital Exhibition.

Forced to flee from Berlin, he continued to use the National Socialists’ own words to expose the truth behind their twisted dreams. In 1934, he montaged four bloody axes tied together to form a swastika to mock The Old Slogan in the “New” Reich: Blood and Iron (AIZ, Prague, March 8, 1934).

In 1938, he had to again run for his life before the imminent Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. There were over 600 people on the Gestapo’s Most Wanted List. John Heartfield was number five. He settled in England. He was interned several times in England as an enemy alien. He was released as his health began to deteriorate. His brother, Wieland, was refused an English residency permit in 1939 and, with his family, left for the United States. John wished to accompany his brother, but was refused entry.

John Heartfield Biography East German (GDR) Persecution

In 1941, Heartfield made it clear that he wished to remain in England and did not wish to return to East Germany [see John Heartfield Letter, 1941]. He and his third wife, Gertrud, found themselves with limited options.

Humboldt University in East Berlin offered Heartfield the position of “Professorship of Satirical Graphics” in 1947.

His response was, “Do I have to be a professor?”

Eventually, his brother Wieland convinced Heartfield to join him in East Berlin. He wanted his brother to take the apartment next to him. Wieland convinced Heartfield that he’d been well treated because Wieland had a comfortable position at a university.

In 1950, John Heartfield joined his brother in East Berlin. The artist who had held such strong beliefs in communist philosophy in his youth was greeted with nothing but suspicion because of the length of his stay in England. He was interrogated by the Stasi and nearly tried for treason against the state. For six years, Heartfield was denied admission to the East German Akademie der Künste. He was unable to work as an artist and denied health benefits.

After six years of official neglect by the East German Akademie der Künste [Academy of Arts], Bertolt Brecht and Stefan Heym intervened on Heartfield’s behalf. He was admitted to the GDR AdK in 1956. However, his health never improved. The later years of life were devoted to designing brilliant costumes, stage sets, and stage projection for the East German Theatre.

John Heartfield died on April 26, 1968 in East Berlin, German Democratic Republic.

Almost all of John Heartfield’s surviving original art is held within the Heartfield Archiv, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Germany. The David King Collection is stored in the Tate Modern London. Hopefully, there will be free public exhibitions soon.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

THE ANTI-FASCIST ARTIST WHO USED HIS WORK AS A WEAPON Miss Rosen for Huck

Armed with scissors, paste, and stone cold nerve, German artist John Heartfield (1891-1968) used art as a weapon to fight Adolf Hilter’s rise to power in the 1930s. His acerbic photomontages, which subverted Nazi imagery to reveal the rising political threat, appeared on the cover of communist magazine Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung – they were seen by millions of people on the newsstand, and in their homes.

Now, thanks to a new exhibition, a new generation of audiences are set to be introduced to his work. Titled Heartfield: One Man’s War, the show explores how the artist risked his life in a propaganda war where he played the part of the anti-Leni Riefenstahl. Trained in advertising, he understood better than most the power of image and text held in swaying public thought.

Read the Full Story at Huck

Art: John Heartfield. The Hand Has Five Fingers, 1928

0 notes

Photo

John Heartfield was a German visual artist who pioneered the use of art as a political weapon. Some of his most famous photomontages were anti-Nazi and anti-fascist statements. Heartfield's formative training in advertising and experiences with Dada theatricality provided him with the visual tools to affect and persuade viewers to action and critical thinking. Heartfield's pro-communist, anti-capitalist photomontages emerge in a moment of war and revolution, and in dialogue with the late Weimar Republic's commodity culture. His provocative photomontages aroused both critical acclaim as well as controversy at the time - especially famous are his anti-fascist montages, for which he was persecuted by the Nazis and spied on by Gestapo agents. The capacity of Heartfield's photomontages to provide a technique through which to conceive alternative views of reality is his contribution to artistic practice across the media arts. Heartfield caused the times to speak for themselves through cut-out fragments from everyday materials, such as advertisements, newspapers, and illustrations. He provoked reality to snap its own picture through excerpts taken from popular mass media products, as a variation on a cameraless photographic process. Heartfield's name is synonymous with his 1930s antifascist photomontages. He became known for his one-man battle against Hitler due to his concentrated critique of this dictator as a liar, backed by the big industrialists. Personally, I felt that I needed to research Heartfield’s work because as an artist he is very inspirational to me and I really admire his work and how he conveys messages about government and politics. Due to his work being very influential, I created my own photomontages as a credit to his work and the passion he had within his art as well as his aspiration for change.

0 notes

Photo

John Heartfield / ‘A Berlin Saying’

Heartfield was well known in the 1930s for his anti-fascist photomontages. “He became known for his one-man battle against Hitler due to his concentrated critique of this dictator as a liar.” [ https://www.theartstory.org/artist-heartfield-john.htm ]

The visual space that was altered and retouched throughout many of his works produced various levels of meanings, whilst providing the audience with further insight and encouraging the viewer to question their own consumption of propaganda and commercial processes.

I enjoy the anti-aesthetics of the images Heartfield uses and how these were developed to challenge the impact the authorities had on societies views during this time period. Heartfield’s practice was considered as playing a large role in The Dada Movement, which was part of the European avant-garde art movement in the early 20th Century. Dadaism expressed discontent with violence, war and nationalism, rejecting the modern Capitalist society. As well as promoting anti-bourgeois protest in their words.

0 notes

Text

Dora Maar

Henriette Theodora Markovitch, pseudonym Dora Maar (November 22, 1907 in the 6th arrondissement of Paris – July 16, 1997 in Paris), was a French photographer, painter, and poet. She was a lover and muse of Pablo Picasso.

Biography Henriette Theodora Markovitch was the only daughter of Joseph Markovitch (1875–1969), a Croatian architect who studied in Zagreb, Vienna, and then Paris where he settled in 1896, and of his spouse, Catholic-raised Louise-Julie Voisin (1877–1942), originally from Cognac, France. In 1910, the family left for Buenos Aires where the father obtained several commissions including for the embassy of Austria-Hungary; His achievements earned him the honor of being decorated by Emperor Francis Joseph I, even though he was "the only architect who did not make a fortune in Buenos Aires. " In 1926, the family returned to Paris. Dora Maar, a pseudonym she chose, took courses at the Central Union of Decorative Arts and the School of Photography. She also enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Julian[2] which had the advantage of offering the same instruction to women as to men. Dora Maar frequented André Lhote's workshop where she met Henri Cartier-Bresson. While studying at the École des Beaux-Arts, Maar met fellow female surrealist Jacqueline Lamba. About her, Maar said, 'I was closely linked with Jacqueline. She asked me, “where are those famous surrealists?" and I told her about cafe de la Place Blanche.' Jacqueline then began to frequent the cafe where she would eventually meet Andre Breton, whom she would later marry.[3] When the workshop ceased its activities, Dora Maar left Paris, alone, for Barcelona and then London, where she photographed the effects of the economic depression following the Wall Street Crash of 1929 in the United States. On her return, and with the help of her father, she opened another workshop at 29 rue d'Astorg, (8th arrondissement of Paris).[4] In 1935 she was introduced to Pablo Picasso and she became his companion and his muse.[5] She took pictures in his studio at the Grands Augustins and tracked the latter stages of his work, Guernica.[5] She later even acted as a model for his piece titled Monument à Apollinaire.

Dora Maar the photographer Maar’s earliest surviving photographs were taken in the early 1920s with a Rolleiflex camera while on a cargo ship going to the Cape Verde Islands.[3] At the beginning of 1930, she set up a photography studio on rue Campagne-Première (14th arrondissement of Paris) with Pierre Kéfer, photographer, and decorator for Jean Epstein's film, The Fall of the House of Usher (1928 French film). In the studio, Maar and Kefer worked together mostly on commercial photography for advertisements and fashion magazines.[3] She met the photographer Brassaï with whom she shared the darkroom in the studio. Brassai once said that she had, “bright eyes and an attentive gaze, a disturbing stare at times.”[3] Dora Maar also met Louis-Victor Emmanuel Sougez, a photographer working for advertising, archeology and artistic director of the newspaper L'Illustration, whom she considered a mentor. In 1932, she had an affair with the filmmaker Louis Chavance. Dora Maar frequented the October group, formed around Jacques Prévert and Max Morise after their break from surrealism. She has her first publication in the magazine Art et Métiers Graphiques in 1932.[6] Her first solo exhibition was held at the Galerie Vanderberg in Paris.[7] After the fascist demonstrations of February 6, 1934, in Paris along with René Lefeuvre, Jacques Soustelle, supported by Simone Weil and Georges Bataille, she signed the tract "Appeal to the struggle" written at the initiative of André Breton. Much of her work is highly influenced by leftist politics of the time, often depicting those who had been thrown into poverty by the depression. She was part of an ultra-leftist association called “masses,” where she first met Georges Bataille,[3] an anti-fascist organization called "The Union of Intellectuals Against Fascism"[8] and a radical collective of left-wing actors and writers called October.[3] She also was involved in many Surrealist groups and often participated in demonstrations, convocations, and cafe conversations. She signed many manifestos including one titled 'when surrealists were right' in august of 1935 which concerned the congress of Paris which had been held in march of that year.[3] In 1935 she took a photo of fashion illustrator and designer Christian Berard that was described by writer and critic Michael Kimmelman as, “wry and mischievous with only his head perceived above the fountain as if he were john the baptist on a silver platter.”[3] At the end of 1935, Dora Maar was hired as a set photographer on Jean Renoir film , The Crime of Monsieur Lange. On this occasion Paul Eluard introduced her to Pablo Picasso.[9] Their liaison would last nearly nine years, without Picasso nevertheless breaking his relationship with Marie-Thérèse Walter, mother of his daughter Maya. Dora Maar photographed the successive stages of the creation of Guernica,[10] painted by Picasso in his studio in the rue des Grands-Augustins from May to June 1937; Picasso used these photographs in his creative process. At the same time, she is the principal model of Picasso, who often represents her in tears, she, herself produced several self-portraits entitled: La Femme qui pleure – The Weeping Woman.[11] It is, however, the gelatin silver works of the surrealist period that remain the most sought after by amateurs: Portrait of Ubu (1936), 29 rue d'Astorg, black and white, collages, photomontages or superimpositions.[12][13][14][15] The photo represents the central character in a popular series of plays by Alfred Jarry called Ubu Roi. The work was first shown at the Exposition Surréaliste d’objets at the Galerie Charles Ratton in Paris and at the International Surrealist Exhibition in London in 1936. She also participated in Participates in Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, at the MoMA in New York the same year.[16] Maar met Picasso in 1936 at the Cafe des Deux Magots. The story of their first encounter was told by the writer Jean-Paul Crespelle, "the young women serious face, lit up by pale blue eyes which looked all the paler because of her thick eyebrows; a sensitive uneasy face, with light and shade passing alternately over it. She kept driving a small pointed pen-knife between her fingers into the wood of the table. Sometimes she missed and a drop of blood appeared between the roses embroidered on her black gloves... Picasso would ask Dora to give him the gloves and would lock them up in the showcase he kept for his mementos."[3] Her liaison with Picasso who physically abused her and made her fight Marie-Therese Walter for his love[17] ended in 1943, although they met again episodically until 1946. Thus, on March 19, 1944, she played the role of Fat Anguish in the reading at Michel Leiris' place of Picasso' first play, Desire Caught by the Tail, led by Albert Camus. In 1944, through the intermediary of Paul Éluard, Dora Maar met Jacques Lacan, who took care of her nervous breakdown by administering her electroshocks,[18] which were forbidden at the time. Picasso bought her a house in Ménerbes, Vaucluse, where she retired and lived alone. She turned to the Catholic religion, met the painter Nicolas de Stael who lived in the same village and turned to abstract paintings.