#anti bodin

Text

That very weird feeling when you're talking about the Mandalorian with your mom and she goes 'I really hope Din and Bo-Katan get together!' and you, a hardcore Dinluke Stan/Ace Din truther - gay Bo-Katan believer answer: 😱😱🤮🤮

Mom: why not? They are right for each other and the story seems to hint at it.

Me (in my mind): mom, you don't get it! Din and Luke are mean to be married bringing up Grogu as a Jedi and a Mandalorian and supporting each other's dying community. They're Yin and Yang, the characters seem made for each other, the parallels are beautiful and Din is Luke's way out of the grisly future Disney has painted for him! In the perfect future they rebuild Mandalore better than it ever was, set Grogu to be the future Manda'lor that reigns for a thousand years, they adopt a lot of other cool, weird kids, Din builds Luke a Jedi temple in Mandalorian space and the two of them have coffee every Monday with the in-laws and the neighbours Sabine Wren and Ezra Bridger....... meanwhile hidden in a closet, like two teenagers, Bo slips Ashoka some 👅.

Me (in reality): I just think they're gross....

#star wars#the mandalorian#the mandalorian s3#din djarin#luke skywalker#din and luke#dinluke#grogu#bo katan kryze#anti bodin#ashoka tano#sabine wren#ezra bridger#leia organa#han solo#manda'lor

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

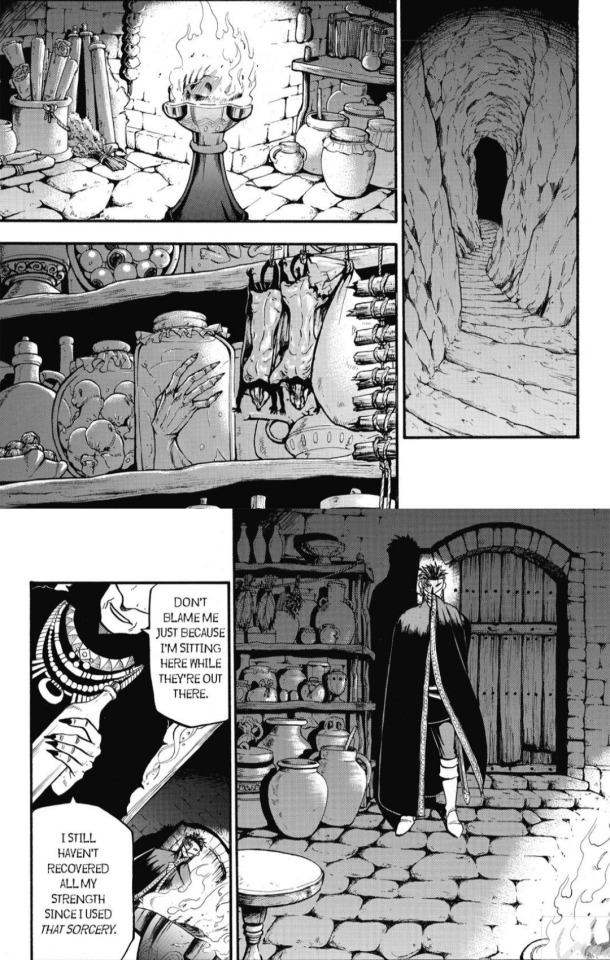

Team Zahhak lair recerence. Very spooky— are those fetuses?

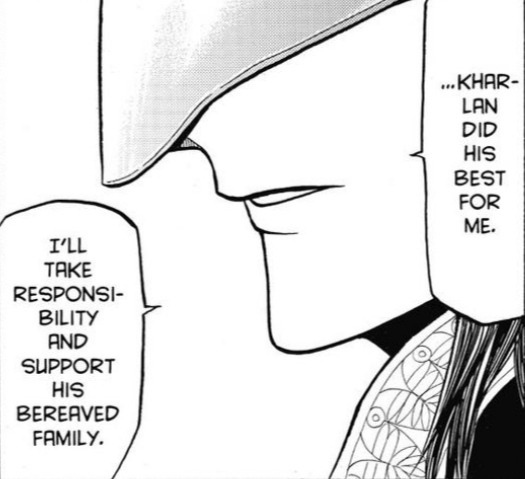

This panel makes my brain go brr bc yes this humanizes Hilmes but also there's a lot of factors contributing to that impression even outside of the dialogue— the panel is relatively small, giving off a vulnerable, subdued feel. His eyes (which often come across as inhuman or burning with an unearthly flame) are not shown, his expression is milder here than before, and the actual dialogue bubbles are also small to give a vibe different from usual: he is not the intense, terrifying man he usually is, he's a grieving person who feels responsible for Kharlan's family after what he's done for him. The result combined with the actual text of the dialogue conveys Hilmes' humanity even before we learn of his backstory. Good. Job.

Also, show us Kharlan's wife, Arakawa. Where is she.

He leaves, and his expression is difficult to see and he's shrouded in shadows. I wonder how he dealt with this loss when he gets truly alone. Does he keep thinking of Kharlan, replaying memories? Imagining an unusually quiet and subdued Hilmes all alone in a big room :(

Before, I used to wonder why the fuck Hilmes was rewarding Team Zahhak with gold of all things— I theorized on whether perhaps precious metals or the like could have a fueling effect on magic but turns out I was overthinking it. It's not bc money is somehow useful to Team Zahhak, no, it's because Hilmes does not understand Team Zahhak and what they're striving for. This scene was meant to convey that they definitely got their thing going on and are likely using Hilmes, and Hilmes is in the dark about a lot of things, including their intentions, going by how the Master dismissively flicks a coin away. It holds no meaning to him, it has no worth.

I kinda feel like a fool, lol.

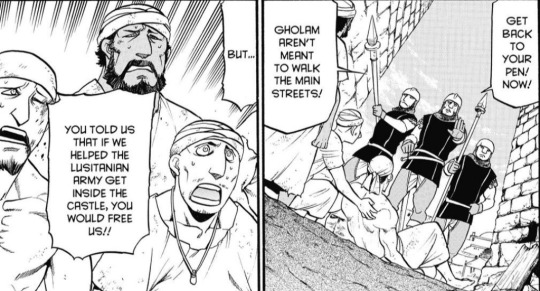

So slaves are not meant to be seen on the main streets? I guess they have their own dedicated pathways? Or is this a Lusitanian invention? Hmm.

Not screencapped but the anklets make an appearance again!

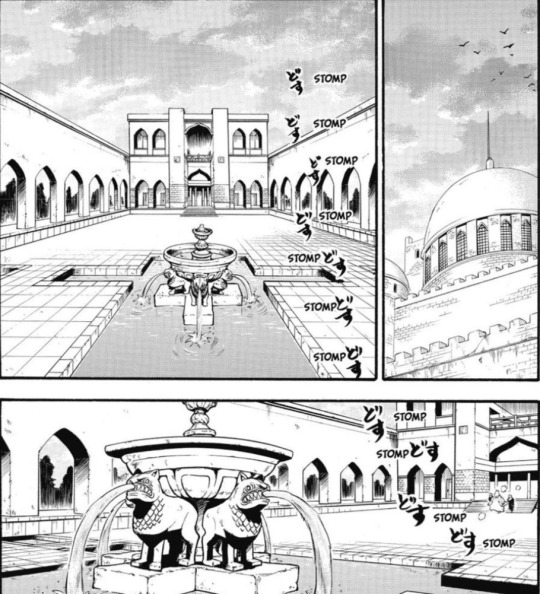

Palace refs! This reminds me of the water garden in Otoyomegatari (which I screencapped in this post) which makes sense considering they're both drawn from the same cultural inspiration.

Yikes.

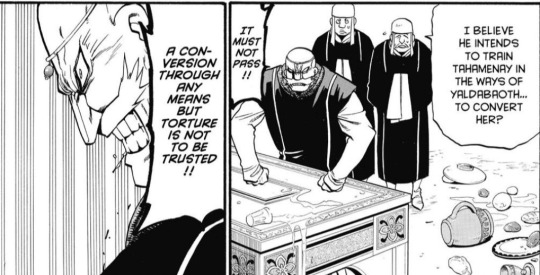

It should be that confessions brought forth by torture should not be trusted bc humans will just say whatever they think their tormenters want them to say just to make the torture end, it's not about obtaining accurate info or confessions at all, has never been. It's about the captors exerting their power over the captive, and it's disgusting.

The same principle applies here. People aren't converting out of genuine faith, they're converting as part of self-preservation. And while I'm not sure Bodin is consciously aware of it or not but it's clear that he just likes flaunting his power over the defenseless rather than wishing to make people see the true glory of Yaldabaoth or whatever.

God I hate this guy.

This must be the royal archives!

The burning of books still boils my blood, it's abhorrent. And Bodin even threw a fellow Lusitanian into the fire just because he suggested a sensible thing of, y'know, not setting these tomes on fire willy-nilly.

It's okay, it's okay, chapter 121 is there for us. It's okay. But god I hate this man.

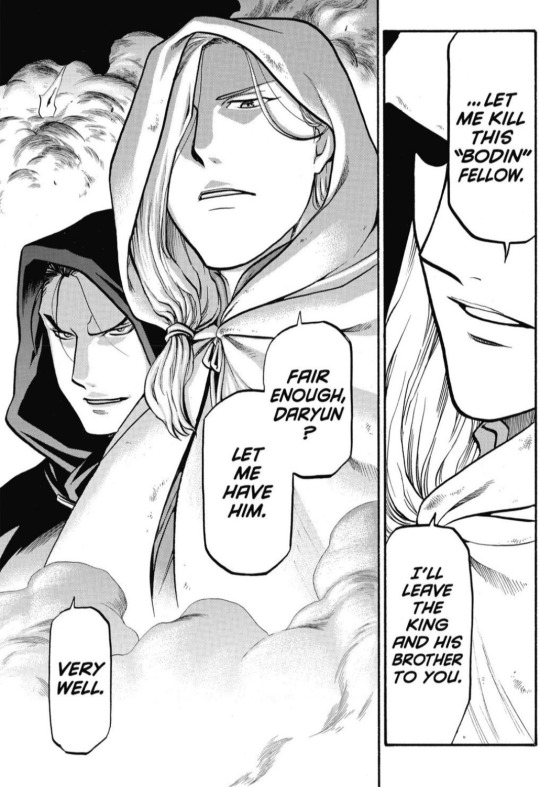

Foreshadowing! :D Rereading Bodin's atrocities gave me even more satisfaction for chapter 121.

I don't really have anything interesting to say about this, just putting it here bc I find it neat.

This is the first we hear of Narsus freeing his household slaves— when we're first introduced to him we only learn that he's a master tactician who pissed off the royal court and left, and though we already had a favorable impression of him (and his anti-slavery sentiments are already apparent) this sheds a newer light on his character.

It is not enough to just flip an old system over like a table and say “there, done, everything's fine and dandy now!”, it doesn't work that way. It is not enough to have an uprising or a revolution or whatever, it is even more important to have a clear vision of what comes after and how to achieve it. Good ruling isn't about winning battles it's about competent administration and resource distribution and all that jazz. It is not enough to just destroy, you must create as well.

The slaves in Ecbatana did not have the means to act on their (supposed) freedom because they hadn't planned for it, they don't have the means to, all they could do was the uprising without the follow-up and... I do not blame them, they didn't know any better, but this just shows how important these sorts of things is.

This also sheds a light on Hilmes because... he doesn't have a vision for Pars' future beyond him ruling it. That is not enough.

And look at Daryun looking concerned for Narsus!

#arslan senki#the heroic legend of arslan#heroic legend of arslan#arslan senki reread#the master#hilmes#bodin#narsus#daryun#this post ended up being more thoughts-heavy#I'm not complaining though#this is a part that invites thought after all

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post #84: NM issues 44-45

Legion’s back! He doesn’t do much this time around though. We open with Rahne visiting Moira, when some big science machine falls on her in the lab. To save her, David gives Jack control of the body, allowing him to use his telekinesis and then run off to be evil. Rahne calls out to Dani through their mindlink, and Illyana teleports the team to Scotland. They reunite with Rahne and Warlock tracks Jack to a bar. There’s a long fight sequence, at the end of which Illyana teleports Jack into Limbo, where Berto threatens to leave him if he doesn’t give David back control. And that’s the whole story. It doesn’t hold a candle to the first Legion story, but then again most things don’t. I like that Berto got a spotlight this time around, and the highlight was definitely his relationship with Illyana. A lot of the New Mutants are wary of her, but Berto and Rahne are the only ones who are truly terrified of her. Berto is able to weaponize those fears to scare Jack into submission, but they haven’t gone away. Rahne also got a few interesting moments during the hunt for Legion, when she ran into the abusive Reverend who raised her. In a moment of anger and pain, she declared that Jack could burn down the whole city if he wanted to. It was just an outburst, but it’s a sign that Rahne is becoming a lot less reserved and peaceful. Other than that, not much to say here. This issue and the last kinda just felt like filler, probably because Claremont was busy planning the Massacre crossover. Regardless, it was nice to see the rest of the team meet Legion, even though David was barely in this one.

Issue 45 is about the New Mutants, along with Kitty, attending a dance at the local high school. The dance scenes are fun, and I like the conversation between Max and the other principal about their struggles to connect with their students. The main focus, weirdly, is on Kitty, and a boy named Larry Bodine that she meets. It’s very nice to see her with someone age appropriate, although tragically it can’t last. Larry is a closeted mutant, with the ability to make hard light sculptures. He’s afraid of anyone finding out, so he’s very closed off, which has led some of his classmates to bully him for that instead. He finds friends in the New Mutants, though, until, in an effort to fit in, he tells some anti-mutant jokes, which obviously upset our main characters. He goes home alone and finds a note from his bullies threatening to call X-Factor, a cruel prank that’s more devastating than they intended due to him thinking someone found out his secret. He commits suicide that night. The next morning, Rahne runs into the kitchen, excited- last night, she felt sure that Larry was good at heart, and followed him home, seeing his sculptures and realizing he was a mutant. But she’s interrupted by Max, who enters to tell everyone the sad news. It’s a sign of how Rahne has grown that she doesn’t take the guilt on herself, rather laying it on the bullies who pushed Larry to suicide. She tracks them down and plans to attack them, but Dani stops her. Rahne is still the kind young girl who believes in the good in people, but in this and last issue we’ve seen the vengeful wolf growing in power inside her. The issue ends with Larry’s funeral, where Kitty, the closet thing Larry had to a friend, gives a short speech to the rest of the kids in attendance. This is the third instalment of the Kitty Pryde Uses Racial Slur trilogy, and she ups her game this time by listing like six in a row. Anyway, she talks about how slurs hurt (which is why you shouldn’t say them, Kitty) and how Larry really was a “mutie.” If not for her opening line, it would be a nice speech. This issue was very after school special-y, even more than that weird one about the kid stalking Stevie. But Claremont did a good job setting up Larry as a potential new student before pulling out the rug, which made the death pretty impactful. I don’t really know why he made Kitty the main character, since it’s not her book. It probably would have been better with Rahne. This issue was fine, and I’m ready to move on.

0 notes

Note

Thoughts on BoDin?

Don’t care all that much tbh. Star Wars is the most anti romantic series ever the only times we saw any romance that was real ended with a genocide of the Jedi OR was the definition of Roguish Outlaw/Noble Lady. Ain’t ever seen any romance since

Ship whatever you want. BoDin. BobaDin. DinCob. DinPaz. I do not care 👍

1 note

·

View note

Text

Feminist History

It serves her right

Vice foe’s reaction after N.Y.’s ‘Wickedest Woman’ killed self

By Mara Bovsun new york daily news

On April Fools’ Day, 1878, 66-year-old Madame Restell was found in her bathtub, naked with her throat slashed. She had killed herself.

“A bloody ending to a bloody life,” was the reaction of Anthony Comstock, an anti-vice activist, upon hearing the news.

Comstock, the city’s postal inspector, was behind the passage of a set of laws that made Restell a criminal. He was also responsible for the arrest that sent her into suicidal despair.

Over nearly 40 years, she had accumulated spectacular wealth by using newspaper ads to offer potions and surgeries to prevent and end pregnancies. She had a lively trade among the city’s elites, as well as its many sex workers and poor women who could not afford another baby.

Her first ads appeared in the patent medicine sections of New York newspapers in 1839, about five years before her nemesis was born.

Under the heading of “Female Monthly Pills,” Madame Restell declared that her preparations had “no rivals” in curing and preventing “female obstructions,” among other health problems.

Her work may have provoked horror, but at the time she opened shop on Greenwich St., it was not against the law. Abortions were legal up to the point of quickening, which is when the baby’s movements can first be felt by the mother. Before then, the baby was not considered to be alive. At that stage, an unwanted pregnancy could sometimes be terminated by such natural substances as pennyroyal, cotton root and rue.

Abortion postquickening was ruled second-degree manslaughter, punishable by a $100 fine and a year in jail.

Madame Restell called herself a physician but had no medical degree or proof of any kind of training. What she had a genius for entrepreneurship.

She was born Ann Trow in 1812, the daughter of a farm laborer in Painswick, England. In her teens, she married the village tailor, Henry Summers, who brought her to the U.S. in 1831. Summers died of typhoid two years later, leaving his widow on her own with a young child.

By 1836, she had a new husband and a profession— “celebrated Female physician,” as newspapers called her. She took a French name and called her products “infallible French female pills.” Her office was open 13 hours a day and was always busy.

For about a decade, she encountered little interference. Local newspapers and the authorities left her alone, although anti-abortion sentiments were growing, especially among doctors. Medical journals published articles calling her a monster.

The National Police Gazette, founded in 1845, added fuel to the movement with editorials condemning abortion and its providers. The cover of one 1847 issue has an illustration of “The Female Abortionist”—Madame Restell with a bat-winged demon devouring a baby.

She had several brushes with the law but continued to prosper.

In 1847, Restell was arrested for performing a postquickening abortion without anesthesia and was charged with manslaughter of the baby. Her patient, Maria Bodine, was a young housekeeper from upstate whose boss had put her in a delicate condition.

During the 18-day trial, Bodine was portrayed by the prosecution as an innocent led astray. Defense attorneys painted her as a sex-crazed prostitute. The jury found Restell guilty on a lesser charge, which meant a year in prison on Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island).

She served her time in relative comfort, thanks to gifts from upper-crust friends who had used her services.

After her release, she said she was giving up her prosperous profession, but it was soon back to business as usual.

By the early 1870s, she had accumulated vast wealth, estimated at around $500,000 (more than $11 million today) and moved uptown to a four-story luxury brownstone at Fifth Ave. and 52nd St. She traveled in a carriage, dressed in the finest clothes, and wore glittering diamonds.

The National Police Gazette noted that street urchins would yell at her as she passed by in her carriage: “Your house is built on baby’s skulls.”

In the same decade, a series of federal and state laws were passed to combat the kind of vice and immorality found in New York City’s cesspools like the Five Points.

The “Comstock Laws,” named after their chief proponent, banned sales of “obscene, lewd or lascivious” works of art and “filthy” books. It also explicitly banned contraceptives and products to induce abortion.

In February 1878, Comstock set a simple trap. He visited Restell’s mansion, pretending to be a man desperate to prevent his pregnant wife from giving birth to another baby that he could not support. Restell sold him some powders and a device that she promised would end his problems.

“Arrest of a She Devil” was how one headline described what happened next.

The case against her was strong, and conviction would mean five years, a sentence the elderly woman would be unlikely to survive.

Out on bail, Restell became increasingly anxious, wandering around the rooms in her mansion, wringing her hands and crying, “Why do they persecute me so? I have done nothing to harm anyone.”

Sometime before dawn on the day of the trial, she sat down in a bathtub full of water and slit her throat with a carving knife.

Rumors swirled that she had faked the suicide by murdering a look-alike and fled. But the coroner brought in several people to identify the body until there was no doubt in his mind that the “Wickedest Woman In New York,” as she was widely known, was gone for good.

JUSTICE STORY has been the Daily News’ exclusive take on true crime tales of murder, mystery and mayhem for more than 100 years.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Are You Scared To Get Happy (issue #3)

YEAR: 1986

CREATED BY: Matt Haynes and Mark Carnell

LOCATION: Bristol and Sheffield

SIZE: A4

WHAT'S INSIDE....

Are You Scared To Get Happy was a quintessential and influential mid-1980s indie rock and pop fanzine. Matt and Mark took the name from the lyrics of "Hip Hip" (the second single by Hurrah!) and even went to the trouble of copying the words that made up their zine's name from the label of the single's B side in order to reprint them on the front cover....

Matt later went on to co-found Sarah Records with Clare Wadd (who also published a zine called Kvatch), but he’d already formed a label called Sha La La with a few other fanzine writers for the purpose of releasing flexi discs.

The first two of Sha La La's releases were included in the price of issue #3 of Are You Scared To Get Happy: the "Bring Back Throwaway Pop!" EP, featuring The Clouds and Mighty Mighty (which was also given away with Baby Honey and Simply Thrilled fanzines) and the "Who Needs The Bloody Cartel Anyway?" EP, featuring Talulah Gosh and Razorcuts (which was also given away with Trout Fishing In Leytonstone fanzine). Every Sha La La flexi disc had a catalogue number starting with "ba ba ba-ba ba", which was something else that Matt borrowed from the lyrics of "Hip Hip" by Hurrah!....

Just like his other zine The Sun Shines Here (which was named after the first single by Hurrah!), Are You Scared To Get Happy was a platform for Matt and Mark to rhapsodise about their favourite indie bands and records (not to mention the thrill of becoming a record company), and to share their opinions about life, the universe and everything (and music they didn't like) with a degree of eloquence that was rare in the wonderful world of fanzines. Many of the musicians they featured were too young to have experienced the punk rock explosion first hand, but were now creating a scene of their own with the same kind of amateurish enthusiasm and excitement as their forebears from just a few years before.

In issue #3 the authors acknowledge the influence of the bands associated with Alan Horne's Postcard Records on the contemporary indie crop, and were happy to award the title of "coolest man in the world" to Julian Cope. His 1984 album "World Shut Your Mouth" is one of my favourites of all time (especially a track called "Kolly Kibber's Birthday") but Matt and Mark were more in love with the singles he had released since breaking up The Teardrop Explodes. They also rave about some recent releases on Alan McGee's Creation label, such as "Therese" by The Bodines ("diamond hard polished pop, light glitters and shimmers from every side of these jingly-jangly tunes") while expressing their Bill Hicks-like distaste for the music industry's marketing tactics and endless attempts to maximise revenue by making each new release available in multiple formats - an approach that independent labels like Creation were also starting to adopt. Not surprisingly, Hurrah! (and their lyrics) get regular mentions throughout the zine....

It's also no surprise that Matt and Mark were highly unimpressed by the NME's C86 cassette - a rather lame indie compilation that the NME put together and promoted with a lavish, week-long event at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London - and they make a point of aiming their anti-establishment chagrin directly at NME journalist and former punk fanzine writer Adrian Thrills, even though his zine 48 Thrills had helped to start the bandwagon of fanzine culture that they were fortunate enough to be able to jump on.

Issue #3 of Are You Scared To Get Happy was the last one that Mark Carnell contributed to, but Matt managed to churn out three more during the next few months.

Click on the title above to see scans of all the zine's pages....

my box of 1980s fanzines

flickr

#are you scared to get happy#matt haynes#mark carnell#fanzine#indie#indie rock#indie pop#indie fanzine#post-punk#1980s#1986

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

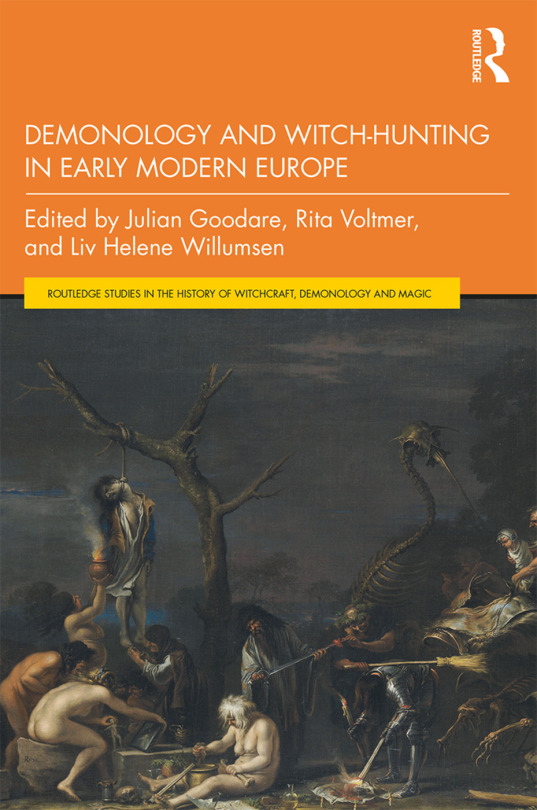

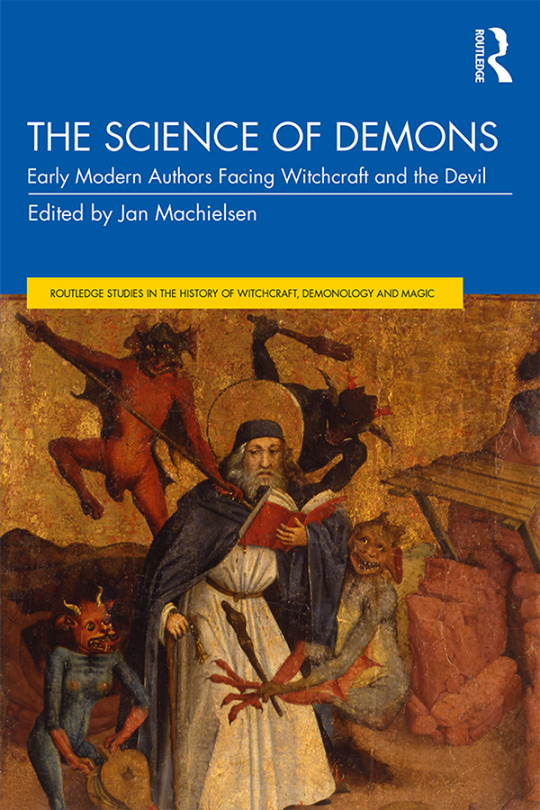

Demonology and Witch-Hunting in Early Modern Europe (Routledge Studies in the History of Witchcraft, Demonology and Magic), edited by Julian Goodare, Rita Voltmer, and Liv Helene Willumsen, Routledge, 2020. Cover painting by Salvator Rosa, info: routledge.com.

Demonology – the intellectual study of demons and their powers – contributed to the prosecution of thousands of witches. But how exactly did intellectual ideas relate to prosecutions? Recent scholarship has shown that some of the demonologists’ concerns remained at an abstract intellectual level, while some of the judges’ concerns reflected popular culture. This book brings demonology and witch-hunting back together, while placing both topics in their specific regional cultures. The book’s chapters, each written by a leading scholar, cover most regions of Europe, from Scandinavia and Britain through to Germany, France and Switzerland, and Italy and Spain. By focusing on various intellectual levels of demonology, from sophisticated demonological thought to the development of specific demonological ideas and ideas within the witch trial environment, the book offers a thorough examination of the relationship between demonology and witch-hunting. Demonology and Witch-Hunting in Early Modern Europe is essential reading for all students and researchers of the history of demonology, witch-hunting and early modern Europe.

Contents:

Illustrations

Preface

Contributors

Introduction: Demonology and Witch-Trials in Dialogue – Rita Voltmer and Liv Helene Willumsen

1. Demonology and the Relevance of the Witches’ Confessions – Rita Voltmer

2. The Metamorphoses of the Anti-Witchcraft Treatise Errores Gazariorum (15th Century) – Georg Modestin

3. "I Confess that I Have Been Ignorant:" How the Malleus Maleficarum Changed the Universe of a Cleric at the End of the Fifteenth Century – Walter Rummel

4. "In the Body:" The Canon Episcopi, Andrea Alciati, and Gianfrancesco Pico’s Humanized Demons – Walter Stephens

5. French Demonology in an English Village: The St Osyth Experiment of 1582 – Marion Gibson

6. English Witchcraft Pamphlets and the Popular Demonic – James Sharpe

7. Witches’ Flight in Scottish Demonology – Julian Goodare

8. Demonology and Scepticism in Early Modern France: Bodin and Montaigne – Felicity Green

9. Judge and Demonologist: Revisiting the Impact of Nicolas Rémy on the Lorraine Witch Trials – Rita Voltmer and Maryse Simon

10. Demonological Texts, Judicial Procedure, and the Spread of Ideas About Witchcraft in Early Modern Rothenburg ob der Tauber – Alison Rowlands

11. To Beat a Glass Drum: The Transmission of Popular Notions of Demonology in Denmark and Germany – Jens Chr. V. Johansen

12. "He Promised Her So Many Things:" Witches, Sabbats, and Devils in Early Modern Denmark – Louise Nyholm Kallestrup

13. Board Games, Dancing, and Lost Shoes: Ideas about Witches’ Gatherings in the Finnmark Witchcraft Trials – Liv Helene Willumsen

14. What Did a Witch-Hunter in Finland Know About Demonology? – Raisa Maria Toivo

15. The Guardian of Hell: Popular Demonology, Exorcism, and Mysticism in Baroque Spain – Maria Tausiet

16. Interpreting Children’s Blåkulla Stories in Sweden (1675) – Jari Eilola

17. Connecting Demonology and Witch-Hunting in Early Modern Europe – Julian Goodare

Index

#book#essay#weird essay#Studies in the History of Witchcraft Demonology and Magic#history of witchcraft#witchcraft#demonology#witch-hunting

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This is one of those “straight up just punch you in the gut” books. This is Larry Bodine who is kinda a weirdo, and because of that everyone from his school picks on him. It turns out Larry is also a mutant, and the threat that all his friends use on him all the time is that he is a freak and they are gonna call X-Factor on him (keep up the good work X-Factor.)

Anyway, one day Larry hangs out with the weird out of town kids (the New Mutants) and he is trying so very hard to fit in so he goes “what do all the cool kids I know do to fit in? I know, I’ll crack some racist anti mutant jokes!” and this obviously goes over just... super well with the group of mutants...

Anyway, Rahne is sure there is something about him, and so she sneaks off to his house only to find out he is in fact a mutant himself, so she rushes home determined to tell all the others in the morning.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

WE JUST SPOTTED (BRAYLAN COHEN) IN PROVIDENCE! DO YOU THINK THEY LOOK LIKE (JAMIE DORNAN)? NAH, (HE’S) A (37) YEAR OLD, (ASTROPHYSICIST), AND CAN BE DESCRIBED AS (INTELLIGENT, WARM, PASSIONATE) BUT CAN ALSO BE (AGGRESSIVE, NEEDY, RUDE ). WHAT ARE THEY DOING IN THE CITY? KEEP AN EYE ON THEM TO FIND OUT.

Vitals

Full Name: Braylan Isaac Cohen

Nickname(s): Bray, Lanny, Bumblebee.

Pronouns: He/Him

Age: 37 years old

Birthday: September 30th

Birthplace: Belfast, Northern Ireland

Occupation: Astrophysicist / Astronaut

Financial Class: Upper Class

Living Arrangement: (x)

Relationships

Nationality: Irish-American

Ethnicity: Irish, English, Other

Mother: Siobhan Turner-Cohen

Father: Bradley Cohen

Children: Bodin Allen-Cohen-Marshall (2) Anais Allen-Cohen-Marshall (2)

Sibling(s): Mary-Claire Jefferson (half-sister)

Extended Family: Marcus Jefferson (Step-dad), Alice Jefferson (Step-sister), Malia Jefferson (Step-sister), Bodhi Jefferson (Step-brother).

Marital Status: Married to @the-doc-wesley + @pearlywhitemarshall

Pet(s): Nadine, the German Shepherd.

Appearance

Hair: Brown & Curly

Eyes: Blue

Build: Athletic

Height: 5′11

Weight: 187 lbs

Wardrobe: (x)

Accent: Irish-American

Mannerisms:

Physical Health: Above Average

Personality

MBTI Type: ENFP-A

Positive Traits: Intelligent, Humble, Charismatic, Gentle, Kind, Empathetic, Welcoming, Honest, Passionate.

Negative Traits: Arrogant, Easily Angered, Mouthy, Bratty, Self-conscious, Awkward.

Likes: Reading, Space, Math, Science, Animals, Fireplaces, Rugs, Candles, Fall, Winter, Spring, Lord of The Rings, Cuddles, Food.

Dislikes: Summer, Injustice, Loud Noises, Blood.

Turn-ons: Intelligence, Passion, Drive, Talent, Paternal Instincts, Neutrality, Kindness, Good Hygiene, Organization.

Turn-offs: Violence, Laziness.

Vices: Sour Candy, Mashed Potatoes.

Mental Health: Average

Sexuality

Gender: Cis-Male

Orientation: Bisexual / Biromantic

Kinks: Foreplay, Public Sex, Group Sex.

Anti-Kinks: BDSM, Violence, Non-sexual Bodily fluids.

Dating Status: Open

Versatility Preference: Verse

Education

School Level Completed: Irish Primary School (3rd Class), Grades 5-12 (American), Graduate Level Studies (University).

School(s) Attended: Dundonald Primary School, HS, MIT

Degree(s): Bachelor of Science (Double Major - EAPS, Physics / Minor in Mathematics), Master of Science (Astrophysics), Ph.D in Astrophysics

Award(s): The Joel Matthew Orloff Award (Research),

Best Subjects: Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Art, Communications, Geography.

Worst Subjects: English Literature, Art History, Biology, History.

Work History: NASA

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

WE JUST SPOTTED (BRAYLAN COHEN) IN PROVIDENCE! DO YOU THINK THEY LOOK LIKE (JAMIE DORNAN)? NAH, (HE’S) A (37) YEAR OLD, (ASTROPHYSICIST), AND CAN BE DESCRIBED AS (INTELLIGENT, WARM, PASSIONATE) BUT CAN ALSO BE (AGGRESSIVE, NEEDY, RUDE ). WHAT ARE THEY DOING IN THE CITY? KEEP AN EYE ON THEM TO FIND OUT.

Vitals

Full Name: Braylan Isaac Cohen

Nickname(s): Bray, Lanny, Bumblebee.

Pronouns: He/Him

Age: 37 years old

Birthday: September 30th

Birthplace: Belfast, Northern Ireland

Occupation: Astrophysicist / Astronaut

Financial Class: Upper Class

Living Arrangement: (x)

Relationships

Nationality: Irish-American

Ethnicity: Irish, English, Other

Mother: Siobhan Turner-Cohen

Father: Bradley Cohen

Children: Bodin Allen-Cohen-Marshall (2) Anais Allen-Cohen-Marshall (2)

Sibling(s): Mary-Claire Jefferson (half-sister)

Extended Family: Marcus Jefferson (Step-dad), Alice Jefferson (Step-sister), Malia Jefferson (Step-sister), Bodhi Jefferson (Step-brother).

Marital Status: Married to @the-doc-wesley + @pearlywhitemarshall

Pet(s): Nadine, the German Shepherd.

Appearance

Hair: Brown & Curly

Eyes: Blue

Build: Athletic

Height: 5′11

Weight: 187 lbs

Wardrobe: (x)

Accent: Irish-American

Mannerisms:

Physical Health: Above Average

Personality

MBTI Type: ENFP-A

Positive Traits: Intelligent, Humble, Charismatic, Gentle, Kind, Empathetic, Welcoming, Honest, Passionate.

Negative Traits: Arrogant, Easily Angered, Mouthy, Bratty, Self-conscious, Awkward.

Likes: Reading, Space, Math, Science, Animals, Fireplaces, Rugs, Candles, Fall, Winter, Spring, Lord of The Rings, Cuddles, Food.

Dislikes: Summer, Injustice, Loud Noises, Blood.

Turn-ons: Intelligence, Passion, Drive, Talent, Paternal Instincts, Neutrality, Kindness, Good Hygiene, Organization.

Turn-offs: Violence, Laziness.

Vices: Sour Candy, Mashed Potatoes.

Mental Health: Average

Sexuality

Gender: Cis-Male

Orientation: Bisexual / Biromantic

Kinks: Foreplay, Public Sex, Group Sex.

Anti-Kinks: BDSM, Violence, Non-sexual Bodily fluids.

Dating Status: Open

Versatility Preference: Verse

Education

School Level Completed: Irish Primary School (3rd Class), Grades 5-12 (American), Graduate Level Studies (University).

School(s) Attended: Dundonald Primary School, HS, MIT

Degree(s): Bachelor of Science (Double Major - EAPS, Physics / Minor in Mathematics), Master of Science (Astrophysics), Ph.D in Astrophysics

Award(s): The Joel Matthew Orloff Award (Research),

Best Subjects: Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Art, Communications, Geography.

Worst Subjects: English Literature, Art History, Biology, History.

Work History: NASA

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

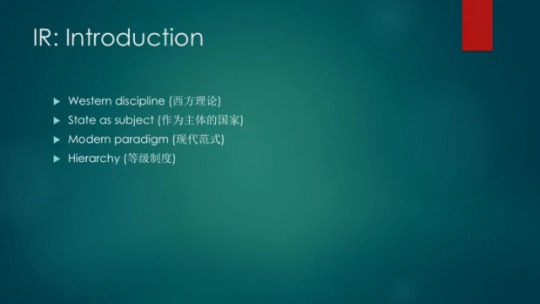

Dugin en Shanghai: Las Relaciones Internacionales y la Geopolítica – Primera conferencia

Traducimos las conferencias del profesor Alexander Dugin en China. Como son conferencias orales, se puede encontrar en el texto múltiples repeticiones y formas entrecortadas de expresión típicas de las exposiciones habladas.

Conferencia dictada en la Universidad Fundan, Shanghai, China, diciembre del 2018

Esta conferencia versará sobre el conocimiento de las Relaciones Internacionales. Será dedicada a la disciplina, la ciencia, de lo que es conocido como las Relaciones Internacionales. El curso completo consta de cuatro conferencias. La primera estará dedicada a las Relaciones Internacionales como disciplina. La segunda a la geopolítica. La tercera a la teoría del mundo multipolar. La cuarta estará dedicada a China en todos estos campos del pensamiento teórico y académico.

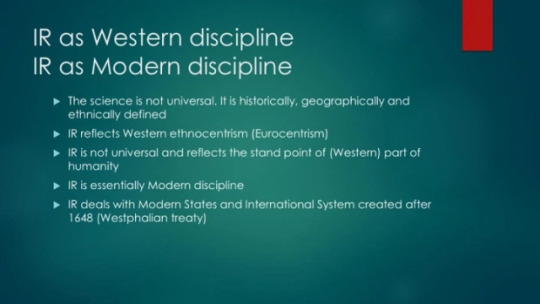

Pero no podemos entender la lógica de este curso sin conocer lo básico de las Relaciones Internacionales, la geopolítica y la multipolaridad. Necesitamos entender que las Relaciones Internacionales son una disciplina Occidental. ¿Qué significa disciplina Occidental” o ciencia Occidental? Ahora, en la actual situación, debemos se cuidadosos, porque conociendo la postmodernidad, la crítica a la modernidad y la antropología moderna, seremos capaces de distinguir lo que es Occidente. La ciencia Occidental y Occidente a menudo intenta imponerse a sí mismos como universales. Este es el aspecto imperialista de la mentalidad Occidental. El pensamiento Occidental es etnocéntrico, y mucho más que etnocéntrico, ni siquiera reconoce su propio etnocentrismo. Esta clase de racismo implícito es peor que el racismo explícito. Los liberales Occidentales dicen que “nosotros definimos los valores universales”, pero cuando preguntamos qué significan esos “valores universales”, comienzan a explicar los valores Occidentales como universales – individualismo, libertarismo, progreso, materialismo. No hay lugar para la metafísica, el espíritu, la creencia en el alma o la vida del más allá. Esto es producto de la civilización Occidental, un producto histórico que pretender ser universal.

Cuando olvidamos que las Relaciones Internacionales, y muchas otras, sino casi todas, las ciencias que estudiamos en las universidades, son Occidentales, entonces estamos desconociendo un aspecto muy importante. Caemos en la trampa de ver estas disciplinas, teorías y ciencias como algo universal. Necesitamos recordar que estamos relacionándonos con una visión Occidental – y sobre todo en la Relaciones Internacionales más que en cualquier cosa. Porque esa es la visión Occidental de como son las cosas.

Además de eso, si hoy día en China o en Rusia, nos consideramos a nosotros mismos como sujetos de la historia, no simples objetos de la historia hecha por otros, entonces deberemos tener presente esta distinción. Eso no significa que debamos negar la ciencia Occidental, resistirnos a la ciencia Occidental, o ignorar la ciencia Occidental. Sino que debemos recordar que es una visión Occidental etnocéntrica. Necesitamos una especie de Muralla China en este campo epistemológico.

Cuando tu conexión de internet se detiene en las fronteras de tu país, tu estas intentando distinguir entre lo que está mal y lo que es posible en la cultura china. Necesitamos establecer la misma muralla en el campo epistemológico.

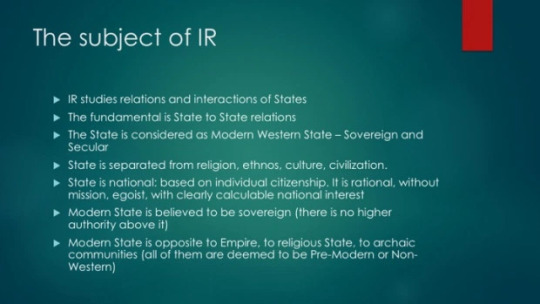

Las relaciones internacionales tratan del Estado como tal. Esto es muy importante. En el centro de esta ciencia, de esta disciplina, se encuentra el concepto de “nación”. Los Occidentales consideran que la nación es un valor político. El Occidente piensa la política en términos del “Estado nación” la cual es la norma desde la paz de Westfalia, y es su actitud formativa. La Nación es un Estado nacional (Etat-Nation), no es ni el pueblo ni el grupo étnico. Las Relaciones Internacionales son relaciones entre Estados. ¿Qué clase de Estados? Estados Occidentales modernos. Este es el primer y más importante principio. Cuando estamos tratando con el concepto de Estado, estamos tratando con un concepto histórico Occidental acerca de cómo la realidad política debe ser organizada y estudiada.

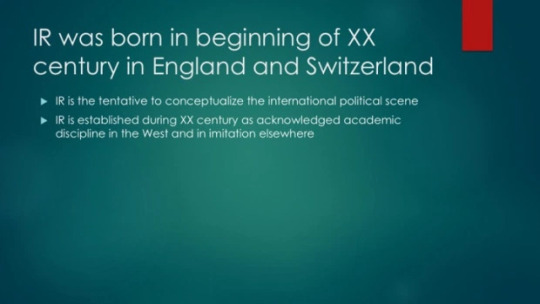

Este es el paradigma moderno. “Paradigma moderno” significa Occidental, pero no toda la historia de Occidente, sino sólo la modernidad. La modernidad transformó la mentalidad Occidental y sólo ha recuperado parte de la mentalidad tradicional Occidental de la Edad Media y la Antigüedad y la ha transformado en algo distinto, una nueva versión. Las Relaciones Internacionales nacieron como disciplina a comienzos del siglo XX. Es Occidental y moderna. La modernidad Occidental es diferente a la premodernidad Occidental. Esto es muy importante desde un punto de vista histórico.

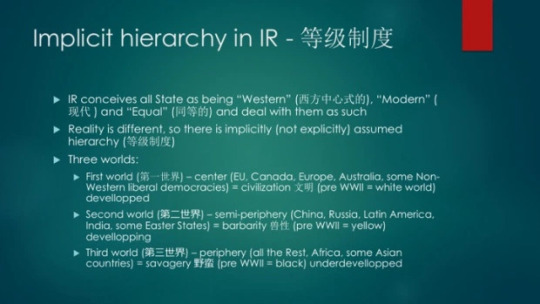

El siguiente punto es que siempre existe una jerarquía implícita en las Relaciones Internacionales. Podríamos decir que es una jerarquía “oculta”. El concepto Occidental de Relaciones Internacionales está basado sobre la idea de que existen ejemplos de Estados “normales” y relaciones “normales”, y son precisamente las del mundo Occidental. Todo el resto se consideran que son subdesarrolladas o no-Occidentales, pero se esfuerzan y tienden a volverse Occidentales. Esta es una clase de jerarquía.

Estos son los cuatro principios que se deberían recordar al estudiar las Relaciones Internacionales, y, sugeriría, también otras ciencias. Las Relaciones Internacionales son una disciplina Occidental y moderna. La ciencia no es universal, sino que esta definida histórica, geográfica y étnicamente. Refleja el etnocentrismo o “Eurocentrismo” Occidental.

Las Relaciones Internacionales no son universales, sino que reflejan un punto de vista de la parte Occidental de la humanidad. Esto nos abre la puerta para preguntarnos como los no-Occidentales debería ver las teorías de las Relaciones Internacionales. ¿Son posibles? ¿Son deseables?

Las Relaciones Internacionales son una disciplina moderna que trata con el Estado moderno y el sistema internacional creado bajo el tratado de Westphalia, cuando se produjo el paso del sistema internacional de la premodernidad a la modernidad, cuando los Estados nacionales soberanos fueron aceptados como actores normativos en la política global. Este no era el caso antes, cuando la religión y las dinastías jugaban un papel esencial. No existía un concepto de calculo puramente racional en los intereses nacionales o del cuerpo del soberano en el Estado. En lugar de ello el Estado tenía una misión, una misión religiosa, una dimensión religiosa – como lo era la política católica en Europa. Con el fin de la Guerra de los Treinta Años, un nuevo sistema político fue establecido y aceptado como universal, normativo, progresivo, y necesario para todo el mundo.

Las R.I. nacieron a comienzos del siglo XX en Inglaterra y Suiza como una “tentativa” de conceptualizar la ciencia política internacional, y ahora está establecida como una ciencia académica reconocida y una disciplina de Occidente, e imitando a Occidente en todas partes. Cuando enseñó Relaciones Internacionales en Rusia es exactamente igual a como son representadas en el resto del mundo.

Entonces, las Relaciones Internacionales estudian las relaciones y las interacciones entre los Estados. El tema fundamental son las relaciones de Estado a Estado, no de persona a persona o de cultura a cultura. El Estado es considerado como el Estado Occidental moderno – soberano y secular. Secular significa que no existe un aspecto religioso o una misión reconocida por el Estado, es completamente racional. La soberanía significa que no existe un gobierno mucho más alto que el del Estado. El Estado es el punto más alto. No existe un dios sobre el Estado y el Estado es el profeta de sí mismo. Esta es la clase de absolutización del Estado que hace cualquier cosa. No existe otra autoridad. Ese es el concepto básico de soberanía. El soberano es quien no es gobernado por nadie más o recibe su legitimidad de alguien más. Esa es la definición de soberanía de Jean Bodin. Fue aplicada primero por los protestantes a la política, y dirigida en contra de la autoridad de la Iglesia Católica, la cual pretendía ser una autoridad supranacional por encima del Estado, y después de eso fue reconocida como norma. La esencia de la soberanía es moderna, y es anti-imperial.

Por ejemplo, en la historia china, de acuerdo con el profesor Zhao Tingyang [1] (赵汀), existe el badoo (霸道) y wangdoo (王道). Badoo (霸道) es el poder basado en la fuerza de la hegemonía, el cual no reconoce ninguna otra autoridad. Wangdoo (王道) es una especie de poder moral y espiritual o místico del emperador. Este no es solamente más grande, sino es completamente diferente, un cambio cualitativo. No es soberanía. Es una misión. Wangdoo (王道) es una misión. La soberanía es moderna y es badoo (霸道).

El Estado es concebido como separado de la religión, las tradiciones étnicas, la cultura y la civilización. El Estado es nacional. ¿Pero qué significa nacional en la política moderna? El Estado está basado en la ciudadanía individual. El concepto de Estado normativo considera al individuo como sujeto del Estado., y todos los individuos, unidos en el Estado nación, son los ciudadanos. Quien no es ciudadano está fuera del Estado. Todos los ciudadanos son políticamente iguales. El concepto de Estado nación es burgués y moderno. No es tradicional. No reconoce clases u otras formas de profesión o diferentes capas de la sociedad – ellas no tienen significado político en el Estado nacional moderno. La nacionalidad está basada en la ciudadanía individual.

El Estado moderno, como sujeto de las Relaciones Internacionales, sin una misión, seria racional, egoísta y tiene un interés nacional claramente calculable. Es un organismo racional. La nación es una creación racional la cual existe en función de organizar a los individuos y proponerles alguna clase de orden y estructura. Si los individuos no son felices con ella, pueden cambiarla. Ese es el concepto de “tratado público social” (contrato). Porque el Estado no tiene nada de trascendental, nada por encima de él, ninguna misión, puede ser rehecho, recreado, destruido, y creado de nuevo, si los individuos o los ciudadanos deciden hacerlo. Está basado en un tratado público o en un acuerdo, esa es la naturaleza contractual del Estado moderno. Es casi como un acuerdo entre, por ejemplo, grupos económicos. Ellos pueden decidir poner su capital junto, y pueden decidir ya no hacerlo y crear una nueva firma. Entonces el Estado es concebido o pensado como una especie de firma comercial. Estas son sus raíces burguesas.

Se cree que el Estado moderno es soberano, entonces no existe autoridad superior a él. Y el Estado moderno es opuesto al Imperio. Es opuesto al Estado religioso, a la comunidad arcaica. Está basado en el concepto de progreso. Es visto como algo que viene históricamente “después” del Imperio, los Estados religiosos y las comunidades arcaicas, todas ellas consideradas como premodernas, mientras que el Estado moderna es la forma de organización política más “novedosa” y “progresista”. Así que el Estado moderno, como concepto burgués, sólo adquiere sentido cuando se lo contextualiza dentro del “progreso”. Si desafiamos el concepto de progreso, todo caerá hecho pedazos. Ningún Estado moderno tiene significado fuera del progreso. Progreso, modernidad y Estado moderno van juntos. El concepto de progreso está contenido en el Estado moderno.

La jerarquía implícita en las Relaciones Internacionales concibe todos los Estados como “Occidentales” o “similares a Occidente”, “modernos” e “iguales”, y cosas por el estilo. La realidad es diferente, porque los Estados, como son, no son como se cree iguales. Existen Estados grandes, Estados enormes y Estados pequeños – todos ellos son soberanos, y todos tienen su lugar dentro de las Naciones Unidas, pero Mónaco y Luxemburgo – Estados soberanos – y China, son incomparables, como un gran sol frente a un diminuto grano de arena. No son iguales.

Pero, curiosamente, la jerarquía de las Relaciones Internacionales contradice que cada Estado soberano es igual a otro [2]. De todos modos, existe y existen debates en las Relaciones Internacionales sobre como explicar y representar esta jerarquía. El viejo racismo Occidental juega un rol importante aquí [3]. El racismo apareció en la época colonial y, poco a poco, paso a paso, clasificó en tres clases humanas. El racismo declara que existe una primera clase de humanidad – la humanidad “blanca”, una segunda clase la humanidad “amarilla”, y una tercera clase la humanidad, la más inferior, la humanidad “negra”. Esto se reflejó en la “antropología” del siglo XIX, en Morgan, por ejemplo, con algunas explicaciones de estos términos. El blanco” significa civilización”; amarillo” significa barbarie” o cuasi-civilizados” y negro” significa salvajismo”, o salvajes” sin ninguna idea de civilización, viviendo en el bosque como recolectores, pequeños campesinos o cazadores.

Podemos ver lo mismo en las Relaciones Internacionales de ahora – aunque formalmente sin racismo, porque fue desacreditado por la Alemania Nazi – donde existe una jerarquía implícita, no oficial que divide todos los países en tres grupos: el Primer Mundo, o el centro del sistema en Wallerstein [4], que es el Norte rico. Es la civilización Occidental, blanca, europea y americana. Es el viejo racismo, en el que los “blancos” son el Primer Mundo porque ellos son más “progresistas”, ricos, “más desarrollados”, tienen más “derechos humanos”, son más liberales, libres y felices. Esta es la vieja historia normativa y etnocéntrica del sistema imperialista, hegemónico y colonial. Aunque ahora no está “conectado” al racismo, el Primer Mundo es un concepto racista. Es la trasposición del antiguo racismo al nuevo plano político liberal. El Segundo Mundo en el sistema de Wallerstein es llamado la “semiperiferia”, representada por China, América Latina, India y algunos Estados orientales, presentados como la “barbarie”. El Occidente dice que ellos son “corruptos”, “autoritarios”, “totalitarios” y no poseen “derechos humanos”. Ellos tienen regímenes cesaristas dictatoriales y corruptos, pero son como “nosotros” – como el Primer Mundo – en la “forma”, y nosotros los “ayudaremos” a desarrollar los derechos humanos, los valores liberales, la transparencia para que algún día nos alcancen y sean también “blancos”.

Entonces existe el Tercer Mundo. Esa es la periferia y, como Thomas Berger y Huntington decían, este es el “resto” de “Occidente y el resto”. Es subdesarrollado y está bajo la influencia de los hegemones del Segundo y Primer Mundo.

Esta es más o menos la jerarquía implícita. Los autores más honestos, como Krasner [5], Hobson [6] y otros reconocen esta jerarquía. Pero este es un momento vergonzoso, porque reconocer la jerarquía implícita en las Relaciones internacionales es lo mismo que reconocer la naturaleza “racista” en la forma liberal de pensar. Este es un problema para la “corrección política”, así que intentan evitar ese aspecto. Pero está implícito, en cualquier caso presente.

Ahora veremos el contenido de la ciencia de las Relaciones Internacionales.

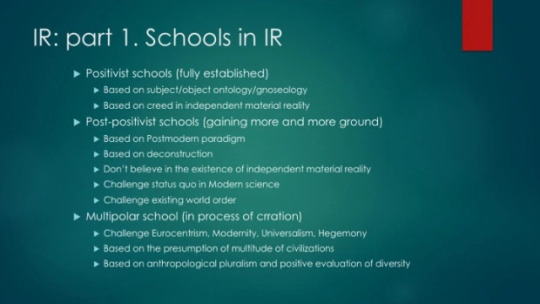

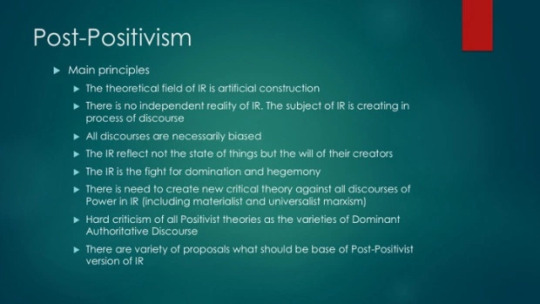

Las Relaciones Internacionales como disciplina tiene diferentes escuelas. Son diferentes en muchas formas. La primera escuela “clásica” que fue establecida fue la escuela positivista. ¿Qué significa “positivismo”? Positivismo significa que esta escuela reconoce la existencia de una realidad “externa” o “material” que es el tema de las Relaciones Internacionales. Existen Estados, interacciones entre los Estados, naciones y economías, y estas existen independientemente de cómo nosotros las describimos. Existen hechos positivos que nosotros observamos, estudiamos y exploramos dentro del tema de las relaciones. Esta es la visión pre-mecánica-cuántica de la realidad. Es el “viejo materialismo” que cree que todo existe por sí mismo, y que la presencia humana describe o trata con esta realidad positiva que siempre está afuera y es independiente de nuestra interpretación. Nuestra interpretación depende de la realidad, la cual no depende de nuestra interpretación, sino que es independiente.

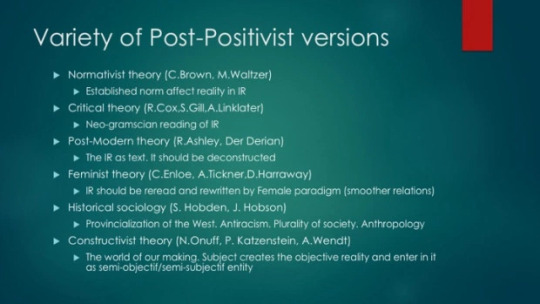

Existe la escuela post-positivista, la cual a ganado más y más importancia en la ciencia de las Relaciones Internacionales. Está basada sobre el postmodernismo, especialmente en la epistemología de Michel Foucault, la cual niega la existencia de los hechos positivos y describe los hechos positivos como una lucha epistemológica. De acuerdo con Foucault la voluntad de saber es la voluntad de poder. Esta es la base ontológica hipercrítica del postmodernismo, que no cree en la existencia de nada fuera de nuestro entendimiento. Esta es la visión de la mecánica cuántica. En la mecánica cuántica la posición del observador está conectada al proceso mismo. Los procesos con o sin observador son diferentes. Este es un concepto introducido por la filosofía postmoderna basada en la deconstrucción del discurso. Según los postpositivistas no existen las Relaciones internacionales. No existe el Estado sin explicaciones, documentos y textos. Todo es escritura, todo es habla y discurso, y al cambiar el discurso cambiamos la realidad. Esto es muy importante. Sugeriría a los estudiantes chinos estudiar con mucha atención la postmodernidad. Es un campo de investigación en crecimiento, y si no comprendemos los principios básicos del postmodernismo, no podremos entender nada del Occidente actual. Porque el Occidente actual nos afecta, no seremos capaces de entendernos a nosotros mismos sí no comprendemos la postmodernidad. La semiperiferia no le presta suficiente atención a la postmodernidad. Necesitamos estudiarla porque, de lo contrario, nos engañaremos fácilmente en muchos aspectos.

La escuela postpositivista no cree en la existencia de la realidad material. Ella piensa que la realidad material es creada en el proceso de hablar, pensar y discutir sobre esta “realidad material”. Esta es la concepción del último Wittgenstein que consideraba que no existen hechos positivos, porque todo hecho positivo estaba cargado de una interpretación. Son los “juegos del lenguaje” los que crean la realidad. Sin sentido, no existen las cosas. Las cosas nacen en el proceso de los juegos del lenguaje. Este es el principio básico de la postmodernidad.

La escuela postpositivista desafía el status quo de la ciencia moderna en general y de las Relaciones Internacionales en particular. Los postpositivistas atacan a la escuela positivista como “idiota” afirmando que pertenece al pasado. Los postmodernistas son también progresistas, pero progresistas críticos. La mayoría de ellos son de izquierda, pertenecientes al marxismo cultural, el trotskismo, el nihilismo y un sinfín de escuelas izquierdistas, socialistas y pro-comunistas. Ese es el porque el postpositivismo desafía el orden existente. Es un tanto revolucionario en la medida en que pretende transformar la epistemología de las Relaciones Internacionales y esto significa transformar la realidad, que es igual al discurso sobre la realidad. Este es el texto en la versión de Derrida. No existe nada además del texto. Si cambiamos el texto, cambiamos la realidad. Este es el aspecto revolucionario de la escuela postmodernista y postpositivista.

La escuela positivista existe desde hace cien años y está establecida con debates, diferentes conferencias y cientos de miles de libros y manuales escritos a favor de una u otra teoría. Y existen controversias.

Pero el postpositivismo en las Relaciones internacionales es nuevo y está ganando cada vez más y más terreno, y tiene que ser tenido en cuenta. En cualquier conferencia de las Relaciones Internacionales habrá un representante de esta escuela. Son escandalosos y pueden parecer marginales, pero ya son parte de la disciplina. En los manuales dedicados a las Relaciones Internacionales, existe una parte dedicada a la exposición de las doctrinas postpositivistas. Ya no son una innovación. Ahora son parte de la disciplina, aunque estén creciendo y desarrollándose, y siguen siendo controversiales y escandalosos, pero son parte de la disciplina.

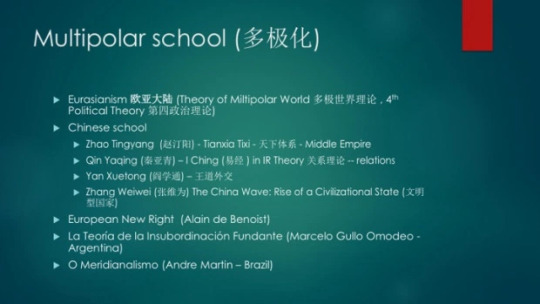

Existe una tercera clase de escuela de las Relaciones Internacionales que no existe aún como una teoría académica aceptada. Pero ha aparecido y comienza a expandirse. Solo ha dado sus primeros pasos. La llamó la escuela multipolar que está en proceso de creación. No existe como una escuela establecida aún, sino que está dando sus primeros pasos. Es precisamente a esta escuela que dedicaré mi tercera conferencia, pero para poseer una visión general de las relaciones internacionales debemos introducirlas primero.

La escuela multipolar desafía el etnocentrismo, la modernidad, el universalismo y la hegemonía global Occidental. Alberga ciertos paralelos con las estructuras postpositivistas. Está basada en la premisa de que existen varias civilizaciones, lo que no afirman los postmodernos. Los postmodernos son universalistas, progresistas y creen en la liberación, la democracia y la ilustración, pero pretender “iluminar la ilustración”, “desarrollar el desarrollo” y “hacer la modernidad más moderna”. Creen que la modernidad no es lo suficientemente moderna. Pretender liberar y llevar a sus últimas consecuencias el proceso de liberación. La postmodernidad es una clase de modernismo futurista.

La escuela multipolar no acepta el progreso lineal ni el estatus normativo de Occidente. El sistema multipolar trata con diferentes civilizaciones, sin ninguna jerarquía. Se basa en la incomparabilidad completa de las diferentes civilizaciones, que debemos estudiar sin tener en cuenta el estado normativo de Occidente. Ese es el nuevo aspecto de la multipolaridad. Se basa en el pluralismo antropológico y en una evaluación positiva de la diversidad. Aquí el concepto del Otro se estudia de manera completamente diferente que en el enfoque occidental tradicional. Podemos decir que el enfoque multipolar no es occidental, y es una escuela de Relaciones Internacionales antioccidental. Eso explica por qué no está tan desarrollado y por qué no está presente en los manuales, y por qué no se menciona durante las discusiones y debates. Se encuentra fuera de lo que se entiende globalmente como occidentalocentrismo. No es el eurocentrismo. Así que no es casual que esta teoría haya sido desarrollada en la semi-periferia. Basado en la nueva antropología de Eduardo Viveiros de Castro y de Eduardo Kohn, que afirma que las tradiciones arcaicas tienen su propia ontología y gnoseología y que debemos aceptarlas como humanas y no como subhumanas, como lo hace la epistemología Occidental progresista y racista.

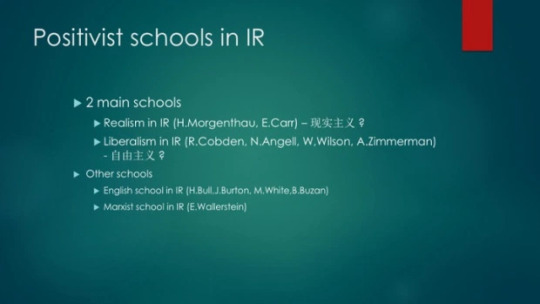

En cuanto a las principales escuelas positivistas en las Relaciones Internacionales, hay dos escuelas principales: el realismo, representado y fundado por Morgenthau y Carr, y el liberalismo, representado por Angell, el presidente estadounidense Woodrow Wilson y Zimmerman. En cualquier universidad normal, se puede aprobar los exámenes si comprendemos el realismo y el liberalismo, porque estos son los principales enfoques que enseñan sobre las relaciones internacionales en las instituciones convencionales, normativas, occidentales (y no occidentales).

¿Qué es el realismo en las relaciones internacionales? El realismo es la idea de que no debe y no puede haber organizaciones supranacionales. Los realistas creen en la soberanía en el sentido que he explicado. Debido a que los realistas creen en la soberanía, piensan que existe un caos en las Relaciones Internacionales. El caos en las Relaciones Internacionales es algo distinto del “caos” en el lenguaje normal. No es desorden, sino la ausencia de un nivel más alto de autoridad que podría obligar legalmente al Estado a hacer cualquier cosa. Los Estados son absolutamente libres, y si no pueden ser obligados a hacer una cosa o impedir que hagan otra o castigarlos legalmente, entonces solo puedes castigarlos y obligarlos ilegalmente. De modo que las relaciones internacionales como campo siempre se basan en este caos, porque la soberanía es soberana, y al reconocer la soberanía como un principio absoluto, solo puede haber relaciones de poder. Si eres más poderoso, puedes obligar a otro, pero no por ley, legalmente, sino por la fuerza. Esto es posible y normal, eso es realismo. Mides fuerzas. Por ejemplo, ¿Cómo pueden sobrevivir los países y los Estados? Siendo el “más grande” o el “más grande” entre los “grandes”. Por ejemplo, hay una pequeña Ucrania y una gran Rusia. Rusia ataca a Ucrania y Ucrania llama a Washington y dice: “Por favor, vengan, los rusos nos atacan”, y los rusos no vienen. Siempre hay una situación abierta. Pero cuando los ucranianos reprimen a los rusos que viven en Ucrania, llaman a Rusia: “Moscú, por favor, ayúdanos, queremos volver a la Madre Patria”. Todo aquí no es “legal” o “igual”, son relaciones de poder. Si puedes hacerlo, hazlo. Invade Crimea, invade Taiwán, invade Hong Kong, si puedes hacerlo. No tienes que esperar cuando eres lo suficientemente fuerte. Esa es la actitud realista. Puedes aceptar que te sentirás decepcionado con alguna posición, y puedes ser un perdedor, o podrías ser un ganador; podrías lamentarlo o podría comenzar una guerra, y puedes hacer la paz. La guerra no es el destino en esa situación, pero es posible, y es real durante toda la historia.

Eso es realismo, la idea de que todo será así para siempre, como en la historia, como ahora y por la eternidad. La mayor parte de los expertos norteamericanos son realistas. Cuando hablamos de Occidente, y sobre todo de los Estados Unidos o Gran Bretaña, al menos la mitad de los expertos, tal vez más, son abiertamente realistas. Eso no es nacionalismo, ni es fascismo, sino que se llama realismo en las Relaciones Internacionales, que representa una escuela de pensamiento que es implícitamente eurocéntrica, y se creó en Europa sobre la base del concepto normativo del Estado y la soberanía.

La otra “mitad” de los expertos son liberales. ¿Qué es el liberalismo en las Relaciones internacionales? Es diferente del liberalismo en las artes, la política y la economía. El liberalismo posee un significado muy concreto y preciso en las Relaciones Internacionales. No es liberal un chico inconformista risueño quien es amigable, mientras que los realistas son halcones malvados y agresivos. ¿Qué significa entonces? Que existe un progreso en las Relaciones Internacionales, que está precedida de un sistema de Estados, o un sistema realista, tendiendo hacia un nuevo sistema con un gobierno mundial. La idea de liberalismo en las Relaciones Internacionales reconoce la necesidad de crear un nivel supranacional de toma de decisiones que deberá ser aplicado legalmente a todos los Estados. Es la creación de otro tipo de Estado – un Estado por encima de los Estados. En este sentido, cuando un gobierno mundial este establecido, todo mundo deberá seguir las órdenes de este gobierno mundial justo como todo ciudadano sigue las órdenes del gobierno de su Estado nación. Es el mismo sistema, pero establecido a un nivel global, planetario. Se explica gracias al concepto de progreso. Tanto los progresistas como los liberales son progresistas, pero los realistas lo aceptan en un sentido relativos, mientras que los liberales creen en él más que en cualquier otra cosa. Existe también el pacifismo entre los liberales, porque ellos tal vez consideren la guerra como un gran mal e intentan evitarla a través de la manipulación y la destrucción de quienes no piensan como ellos. La guerra es para ellos matar a quienes no aceptan el gobierno mundial.

Esta idea, al igual que los derechos humanos, está basada en el liberalismo de las Relaciones Internacionales. Intenta hacer a los ciudadanos y a los humanos iguales, lo cual solo es posible aún nivel supranacional si nosotros reconocemos los mismos derechos de un ciudadano, como parte de un Estado Nación, y al ser humano como un ser con ninguna conexión concreta a un estatuto político, en una versión cosmopolita. Si tu reconoces ambos como legalmente iguales, entonces necesitarás de un gobierno mundial para impulsarlo y obligarlo. Necesitarías de alguna clase de nivel de autoridad para poder obligar a los diferentes Estados Nación a tratar a los seres humanos del modo en que el gobierno global de los liberales piensa que deben ser tratados legalmente. El liberalismo intenta debilitar a los Estados Nación, al reducir su soberanía, e instalar un orden internacional en lugar del caos. esta es la otra mitad de los expertos occidentales de las Relaciones Internacionales.

El liberalismo en las Relaciones Internacionales es globalización, cosmopolitismo, individualismo, ideología de los derechos humanos, progreso, y la idea de destruir los Estados nación y destruir cualquier clase de ciudadanía para crear una “ciudadanía mundial”. Para lograrlo, es necesario disolver los Estados nación, porque ellos pretenden ser soberanos.

El debate de estas dos escuelas representa la historia del siglo XX. La creación de la Liga de Naciones después de la Primera Guerra Mundial, la creación de las Naciones Unidas, el Tribunal de la Haya, la Unión Europea, y la Corte Europea de Derechos Humanos – todos estos fueron intentos de implementar la teoría liberal de Relaciones Internacionales. No se trata de un acuerdo entre los Estados, sino que es el liberalismo en las Relaciones Internacionales. Está basada en el progreso y la afirmación de que el Estado Nación no es perfecto, como dicen los realistas, sino que es una etapa del desarrollo humano social, político y cultural.

El globalismo y la globalización son la primera la primera teoría, en el pensamiento, no en los hechos. Es un discurso representado por los liberales. El liberalismo en las relaciones internacionales abiertamente clama la creación de un gobierno mundial y la deconstrucción de los Estados Nación. No se trata de una teoría conspirativa. Es parte de los manuales, la cual tu puedes ver si lees con cuidado los manuales existentes sobre Relaciones Internacionales en cualquier país. Quizás resulte sorprendente descubrir que el concepto de gobierno global no es una teoría conspirativa o la idea que una pequeña élite pretende imponer, sino que es una teoría abiertamente reconocida – una de las dos principales teorías reconocidas en las Relaciones Internacionales.

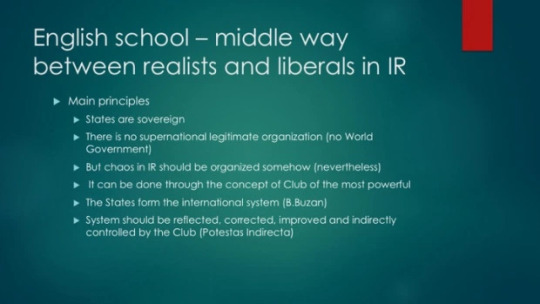

Existen otras dos escuelas también positivistas. Una de ellas es la escuela inglesa que es una especie de “camino intermedio”. Los representantes de esta escuela dicen que debe existir la soberanía de los Estados, y no el gobierno mundial, pero los Estados más desarrollados deben crear un “club” que no castigara, sino que “excluirá” o hará presión sobre los otros – ese sería el G8 que fue transformado en el G7. Rusia fue castigado por el “club” en la escuela inglesa. Fue ilegal. No existen instituciones – solo el club. Ellos pueden aceptar a alguien y excluir a los otros. Esta es una constante de la escuela inglesa – existe el orden, pero está basado en los acuerdos y reglas del club – no en la ley, un gobierno mundial, sino en un club global. Hedley Bull, John Burton y Barry Buzan, quien es el más brillante de los expertos de la escuela inglesa – me gusta mucho – y quien explica la transformación del sistema internacional a través de la historia, es una sociología histórica de las Relaciones Internacionales.

Existe también la escuela marxista de las Relaciones Internacionales. Pero no es conocida por nosotros porque no es estalinista, maoísta o soviética. Es más bien trotskista. Nuestra política china y rusa y las tradiciones en China y Rusia estaban basadas en el realismo, con algunos “detalles” especiales acerca del progreso, socialismo, sistemas sociales, pero eran más o menos abiertamente rusocéntricas o chinocéntricas. Pero la escuela marxista de relaciones internacionales es otra cosa. Afirma que existe un mundo global desde el principio: el capitalismo. El capitalismo es global y la división entre Estados Nación es una especie de formalidad que no representa la realidad. El capitalismo nació en Occidente, y debió expandirse por toda la tierra. Y sólo cuando todo el mundo sea capitalista y sea liberal, ya no habrá más naciones, pueblos o razas, sino solo clases – sólo dos: la capitalista arriba, de naturaleza internacional, y el proletariado abajo, también internacional. Los marxistas en las Relaciones Internacionales están en contra de los ejemplos de Rusia y China porque para ellos son alguna clase de “versión nacional” del comunismo. Ellos insisten que las Relaciones Internacionales – todas – deben ser absolutamente internacionales – sin nacionalidad, sin tradición, sin lenguaje, sólo relaciones de clase entre los burgueses internacionales y el proletariado internacional. Y cuando sean internacionales significará que el capitalismo ganó. Y después vendrá la revolución. Pero antes, debe ser global. Así que ellos son muy cercanos a los liberales: “déjenlos ganar y después vendremos nosotros”. Este es el concepto de multitudes e Imperio de Negri y Hardt [7].

Estas son más o menos las dos principales escuelas, que representan la mayor parte de las Relaciones Internacionales. En los Estados Unidos, por ejemplo, todo mundo es ya sea liberal o realista. Esa es su posición normal, incluso en los debates. Trump es realista y Hillary Clinton es liberal. Entonces puede haber realistas buenos, realistas malos, liberales locos – no importa. Hablamos de ideas.

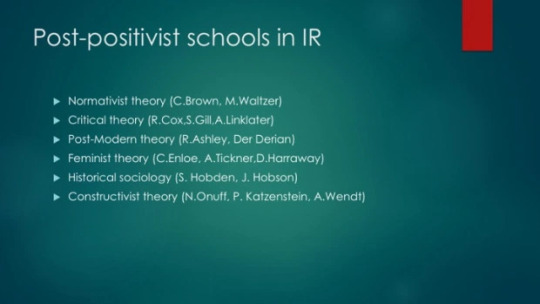

Pero la escuela postpositivista es más interesante en mi opinión. Existen teorías normativas que, si nosotros creamos una norma, ella no refleja la realidad, pero crea la realidad y todos seguirán la norma. Si castigas a alguien en la calle por violar alguna norma, poco a poco esta norma, que no refleja nada, crea en las personas un comportamiento “correctivo” por esta norma. Al cambiar las normas, cambiamos la realidad – esta es la versión modesta del postpositivismo.

La teoría crítica de Cox [8], Gill [9] y Linklater [10], intentan criticar las ideas liberales y realistas que son inconsistentes con un punto de vista postmoderno, mostrando que defienden el status quo y son parciales – política, intelectual y estructuralmente. La teoría crítica muestra cómo el discurso de las Relaciones internacionales es parcial. Ese es su principal propósito. La teoría postmoderna, como la de Ashley [11] y Der Derian [12] dicen que las Relaciones Internacionales consisten únicamente en textos y solo textos. Esta es la aplicación de Derrida a las Relaciones Internacionales. Si deconstruyes los textos, veras que no hay nada detrás de ellos. Todo está basado en información corrompida de los acontecimientos. Si cambias la información de los acontecimientos y reordenas los hechos”, inmediatamente obtienes una imagen distinta de la realidad. Este es el “perro persiguiendo su cola”. El poder suave es una parte aplicada de esta idea. La teoría postmoderna está basada en la deconstrucción de los discursos de las Relaciones Internacionales.

La siguiente sería la teoría feminista de Enloe [14], Tickner [14] y Donna Haraway [15]. El feminismo en las Relaciones Internacionales afirma que todas las Relaciones internacionales han sido hechas, concebidas, descritas, propuestas y promovidas por hombres en una especie de jerarquía… Si ponemos a la mujer en lugar del hombre, ella seguramente creará la paz, la prosperidad, la amistad y las buenas relaciones entre los países. No habrá Estado, ni patriarcado, ni jerarquía, ni verticalidad en las Relaciones Internacionales. Será una descripción completamente diferente de la realidad. Si una mujer no pretende ser un hombre al tratar las Relaciones Internacionales, y si la mujer intenta continuar siendo “la mujer” y describir la realidad desde el punto de vista de la mujer, entonces se producirá una construcción completamente diferente de las Relaciones Internacionales. Es la relativización del dominio masculino en las Relaciones Internacionales. Es una teoría en desarrollo, y sugiero tomar el feminismo en serio. No es un chiste; es parte de la civilización moderna.

En la sociología histórica de las relaciones Internacionales, Hobden y Hobson [16] intentan poner en su contexto el discurso sobre las Relaciones Internacionales. Criticando el punto de vista occidentalocéntrico y eurocéntrico.

Y existe la teoría constructivista de Onuff [17], Katzenstein [18] y Wendt [18]. Afirman más o menos lo mismo que los otros. Parten de que es necesario reconstruir, y no sólo deconstruir, las Relaciones Internacionales. La principal tesis de Onuff es que “nosotros construimos el mundo”. Vivimos en el mundo el cual nosotros hacemos. No existe el mundo. El único mundo que existe es el que nosotros hacemos. Esta es su idea principal. Se trata de una alucinación o imaginación inmóvil y congelada. No existe la realidad positiva, entonces creamos el mundo que soñamos, el mundo que queremos. Es posible ya que vivimos en un orden imaginario.

La escuela multipolar, de la que solo evocaré algunos aspectos, incluye el eurasianismo y la teoría del mundo multipolar y la cuarta teoría política, que es precisamente en lo que estoy trabajando. Hay muchos textos que son más o menos aceptados como la posición de la estrategia rusa en las Relaciones Internacionales y la tradición de realismo ruso. Está ganando popularidad en Rusia. Puedes ver cómo Putin ha creado la Unión Euroasiática. La multipolaridad es muy importante y ha sido abordada por el Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores, Lavrov. Eso es algo en lo que estoy trabajando.

Existe la escuela china, que incluyen a Zhao Tingyang (赵汀阳) [20], Qin Yaqing (秦亚青) [21], Yan Xuetong (阎学通) [22], y Zhang Weiwei (张维为) [23]. El concepto de aproximación de estos autores no es solo el realismo, aunque Yan Xuetong es realista. Sin embargo, todos ellos intentan partir de las singularidades de la civilización china y sobre todo del concepto de Tianxia Tixi (天下体系), la cual remite a las relaciones históricas chinas con otros pueblos como algo no puramente hegemónico, ni por la fuerza ni impuesta. Vietnam es un ejemplo muy interesante. Aceptó la cultura china en todos sus detalles, pero jamás reconoció su control físico directo, por medio de la fuerza bruta, y luchó en contra de China en sus intentos de someterla y al mismo tiempo siendo parte del universo chino, y opuesto al caso de Japón que subyugó a Corea, el imperio de Tianxia (天下), no es sólo China como Estado, sino China como polo de civilización con múltiples aristas. La idea de defenderlo en la situación actual es una idea revolucionaria, porque desafía todos los otros discursos, justo como el Eurasianismo desafía el occidentalocéntrismo. Existen muchas similitudes entre ellos.

Existe también la Nueva Derecha europea de Alain de Benoist, el GRECE francés y la Nueva Derecha francesa. No son liberales, sino antiliberales, no son nacionalistas, sino europeístas, ni católicos ni cristianos, sino paganos, con muy interesantes ideas para recrear la civilización europea premoderna. Porque ellos viven en el interior de la globalización y la civilización moderna Occidental sus observaciones y teorías son muy importantes para los países y culturas fuera de Occidente.

La Teoría de la Insubordinación Fundante [24] es una teoría muy interesante de Marcelo Gullo Omodeo de Argentina el cual representa la idea de que, básicamente, América Latina no debería estar sometida a América del Norte y el orden global mundial. Esta es una idea muy famosa y desarrollada en América Latina. Está creciendo en importancia. Marcelo Gullo Omodeo hace parte del discurso multipolar el cual es completamente nuevo en las Relaciones Internacionales.

Y existe el autor brasileño Andre Martin, con su O Meridinalismo, el cual expone la idea de que el Sur debe ser una unidad alternativa al Norte, no siguiendo o intentando igualar al Norte, sino crear diferentes relaciones entre América Latina y, por ejemplo, África y los países del Sudeste Asiático. Este es un concepto muy importante basado en la multipolaridad.

Lo que es importante en todas ellas es que retan el eurocentrismo. Consideran que las Relaciones Internacionales son provinciales en su Estado presente, conceptos provinciales Occidentales como pretendidamente hegemónicos, universalistas, colonialistas, imperialistas. Intentan reducir la teoría de las Relaciones Internacionales a un contexto mucho más amplio, defendiendo los derechos de los pueblos y civilizaciones en lugar de los Estados Nación o el gobierno mundial. Existen liberales, realistas y postmodernistas.

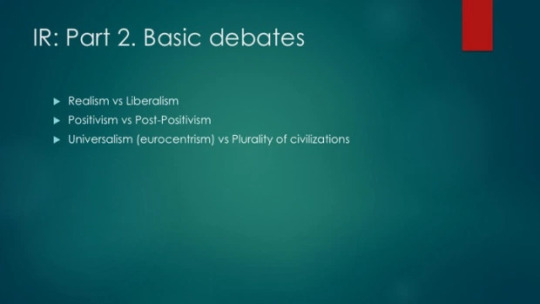

Podemos considerar los debates en las Relaciones Internacionales, entre realistas y liberales en las Relaciones Internacionales. Esa es la mayor parte de la ciencia. La disciplina de las relaciones Internacionales está dedicada a esta pregunta: como los liberales consideran que es posible la paz si reducimos la soberanía de los Estados, y como los realistas responden lo contrario, porque todos intentan usar las instituciones internacionales a su favor. Los realistas dicen que las Naciones Unidas son un fracaso, los liberales dicen que es mejor a que no existan instituciones internacionales. Existen miles de libros al respecto. Claramente lo que es discutido en Occidente al nivel práctico en las Relaciones Internacionales gira alrededor de ello. Los norteamericanos hablan con honestidad acerca de esto y llaman las cosas por su nombre. No tienen vergüenza y hablan acerca de la hegemonía, el realismo, el caos, el internacionalismo, confrontan sus argumentos y se atacan mutuamente. Pero son honestos al respecto y solamente ellos lo son. Cuando se va Europa solo existe la corrección política. No existe el realismo en Europa. Es imposible. En Europa los realistas en las Relaciones Internacionales son “fascistas”, con los que no existe la cordialidad. Existe una cantidad aplastante de liberales en las Relaciones Internacionales en Europa. En las manuales seguramente leerás las disputas de los realistas como Morgenthau, Carr y el caos en las Relaciones Internacionales, pero en los debates oficiales de la diplomacia europea, prevalece exclusivamente el liberalismo en las relaciones Internacionales. Y la práctica de esto es la Unión Europea, la cual es una estructura supranacional que revela cómo el liberalismo en las Relaciones Internacionales es una realidad. No es una broma. Son liberales. Antes existían diferentes posturas, como el gaullismo de Charles le Gaulle por ejemplo. El realismo ha existido en la historia de Europa, y toda su historia moderna fueron luchas, guerras y peleas entre naciones, pero hoy el liberalismo es absoluto y prevalece sobre todo. El realismo no es reconocido. Es hipocresía. Promueven los derechos humanos siempre y en todas partes, incluyendo cuando destruyen un país para robarle sus recursos, como por ejemplo libia, pero todo fue por los “derechos humanos”. Puedes matar en favor de los derechos humanos, invadir, destruir y apoyar a islamistas radicales si eso apoya los “derechos humanos”. Los estadounidenses dicen “es nuestro negocio, y los negocios son negocios, no es nada personal” y cerramos nuestros ojos cuando hablamos de Arabia Saudita en algunas situaciones porque son nuestros aliados, y los abrimos cuando hablamos sobre Rusia y cuando nada pasa en Rusia simplemente lo imaginamos e inventamos una historia.

En ese sentido, reconozco a los Estados Unidos como un ejemplo de un lugar normal y honesto de debate entre realistas, quienes son considerados como una parte completamente normal de la sociedad – la mitad de los estadounidenses son realistas – y la otra mitad son liberales, quienes intentan satanizar a los realistas ahora, y esto es lo que sucede en Europa, con la elección de Trump. Es realista, es honesto, son aliados, América Primero, y los liberales argumentan que “no, no eso es nacionalismo”. Y los liberales han perdido. Eso demuestra que el realismo representa la mitad del espectro político de la elite política de los Estados Unidos, y ellos mismos reconocen que “no es algo personal”. Simplemente es una escuela de las Relaciones Internacionales pura y honesta en los Estados Unidos de América. En la Europa contemporánea no existe claramente esta posibilidad. Los liberales satanizan a los realistas llamándolos “fascistas”, “extremistas”, “agentes de Putin”, “hackers rusos” y demás. Pero ahora, en Italia, Hungría y algunos otros países existen, por ejemplo, gobiernos realistas. Existen realistas de izquierda y de derecha. El realismo existe en Europa a pesar de la corrección política y el globalismo.

El otro debate – mucho más interesante y cargado con ironía y humor – es el que existe entre positivismo contra postpositivismo, el cual es filosófico, pero que en las Relaciones Internacionales adquiere una dimensión especial. Recomiendo a los filósofos, y a los filósofos chinos, prestar atención al postmodernismo en las Relaciones Internacionales al igual que al postmodernismo en su sentido más amplio. No me refiero únicamente a la filosofía abstracta y al jugar con conceptos como las mesetas de Deleuze o Lacan, sino a las Relaciones Internacionales en la vida diaria que veras como funciona el postmodernismo.

Los otros temas de debate son el universalismo y el eurocentrismo contra la pluralidad de civilizaciones. Esta es la teoría multipolar que a penas está en sus primeras etapas de desarrollo.

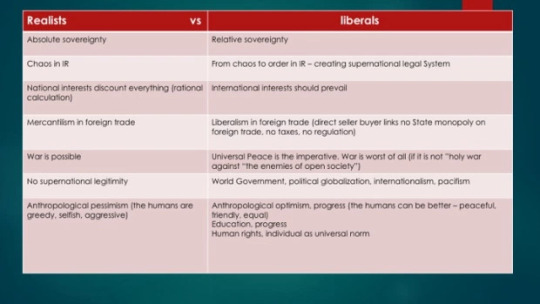

Los principales principios del realismo son:

La soberanía absoluta:

Caos en las Relaciones Internacionales,

El interés nacional completamente basado en el calculo racional,

El mercantilismo en el comercio exterior, lo que significa que el Estado debe controlar el comercio exterior por medio de impuestos,

No existe la legitimidad supranacional,

Pesimismo antropológico.

Es interesante que los realistas digan que el Estado debe existir porque los hombres son “malos”, y para ponerlos en orden debemos tener un Estado – de lo contrario se comportarán de modo impredecible y lo destruirán todo. Así que son pesimistas e intentan poner a los hombres en su lugar basados en un acuerdo mutuo. No creen que los hombres puedan cambiar con el progreso. Permanecerán siendo iguales.

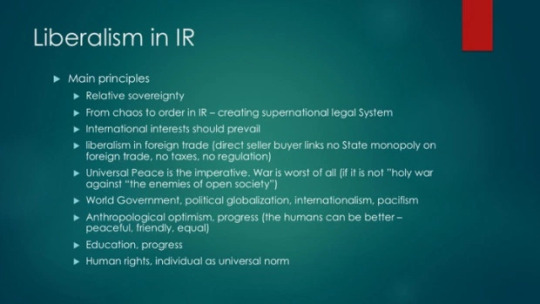

Los principios del liberalismo son:

Soberanía relativa,

Es posible pasar del caos al orden en las Relaciones Internacionales creando un sistema legal supranacional, los intereses internacionales deben prevalecer – lo cual es incomprensible para los realistas, para quienes no existen los intereses internacionales ya que estos no existen,

Liberalismo en el comercio, compra y venta sin ningún vinculo con ningún monopolio estatal en el comercio exterior, y ninguna regulación en la política económica extranjera,

Y la paz universal es un imperativo. La guerra es lo peor de todo, si no se trata de la “guerra santa” en contra de los enemigos de la sociedad abierta,

Gobierno mundial, globalización política, internacionalismo (y algunas veces pacifismo),

Optimismo antropológico, o idea de progreso, que los humanos pueden ser mejores, más pacíficos, más amigables, más risueños, mas iguales,

La educación y el progreso son medios políticos para destruir los Estados Nación usando la epistemología para promover su visión del mundo,

Los derechos humanos y los individuos son norma universal. No existe el concepto de ciudadano como en el realismo, sino el de individuo que es un concepto global.

Si lo observamos en su conjunto, vemos que existe una oposición simétrica – concepto contra concepto, afirmación contra negación. Lo que el realismo afirma y acepta, los liberales se oponen y niegan en las Relaciones Internacionales. Veremos la simetría en este debate y, al decir verdad, podemos encontrar bases intelectuales en ambos. No es el caso de “ignorantes” contra “sabios”. Es una forma de mentalidad en contra de otra forma de mentalidad. Puedes escoger tu posición.

La escuela inglesa o del “término medio”:

Los estados son soberanos: