#anne bauchens

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

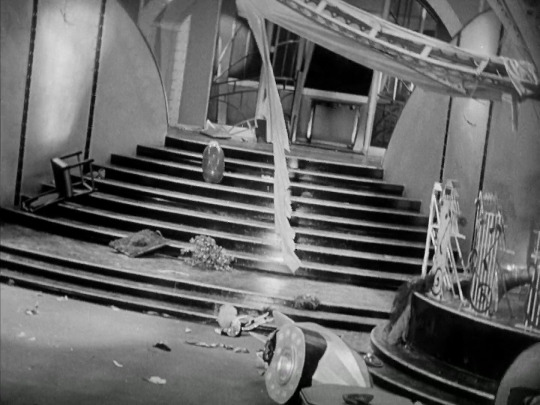

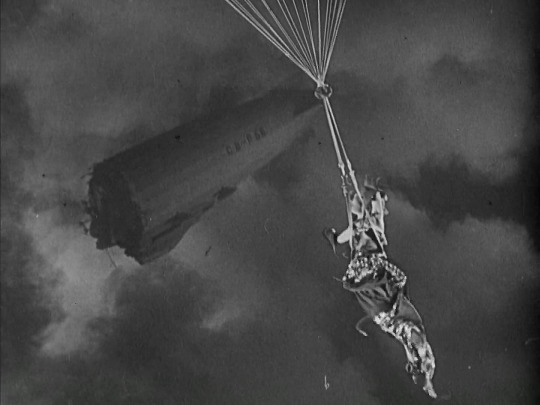

Madam Satan (Cecil B. DeMille, 1930).

#madam satan#cecil b. demille#kay johnson#reginald denny#harold rosson#anne bauchens#cedric gibbons#mitchell leisen#adrian

114 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Victor Varconi and Majel Coleman in The King of Kings (Cecil B. DeMille, 1927)

Cast: H.B. Warner, Dorothy Cumming, Ernest Torrance, Joseph Schildkraut, James Neil, Joseph Striker, Jacqueline Logan, Rudolph Schildkraut, Victor Varconi, Majel Coleman, Montagu Love, William Boyd, Michael D. Moore, Kenneth Thomson, Alan Brooks. Screenplay: Jeanie Macpherson. Cinematography: J. Peverell Marley. Production design: Dan Sayre Groesback, Anton Grot, Julian Harrison, Edward C. Jewell, Mitchell Leisen. Film editing: Anne Bauchens, Harold McLernon. Music: Hugo Riesenfeld.

Director Cecil B. DeMille always had a fondness for unintentionally hilarious dialogue. Think of Anne Baxter's Nefretiri purring to Charlton Heston's Moses in The Ten Commandments (1956), "Oh, Moses, Moses, you stubborn, splendid adorable fool!" I'm almost sorry that The King of Kings is a silent film, so that we can't hear Mary Magdalene (Jacqueline Logan) utter the line: "Harness my zebras -- gift of the Nubian king! This Carpenter shall learn that he cannot hold a man from Mary Magdalene!" After the intertitle card fades, she swans off to rescue her lover, Judas Iscariot (Joseph Schildkraut), from the clutches of Jesus (H.B. Warner). It seems that Judas has become a disciple of Jesus because he believes that he has a chance at a powerful position in the new kingdom that Jesus is planning. This isn't the only hashing-up of the gospels that the credited scenarist, Jeanie Macpherson, commits, but it's the most surprising one. It also gives director DeMille an opportunity to introduce some sexy sinning before he gets pious on us: The Magdalene is vamping around a somewhat stylized orgy and wearing a costume (probably designed by an uncredited Adrian, who was good at that sort of thing) that leaves one breast almost bare. This opening sequence is also in two-strip Technicolor, as is the Resurrection scene some two and a half hours later. Yes, it's an enormously tasteless movie. Warner's Jesus is the usual blue-eyed blond in a white bathrobe found in vulgar iconography, and the actor has little to do but stand around looking wistful and sad at the plight of the world, occasionally giving a little smile that, with Warner's thin, lipsticked mouth, verges dangerously on a smirk. The film goes heavy on the miracles, even recasting one of the gospel writers, Mark, as a boy (Michael D. Moore) cured of lameness by Jesus. (When he throws away his crutch, it accidentally strikes one of the Pharisees standing nearby, only adding to their enmity to Jesus.) Unfortunately, DeMille stages the revival of Lazarus (Kenneth Thomson) in a way that enhances its creepiness, having him emerge from a sarcophagus swathed in bandages like a horror-film mummy. Still, there's entertainment to be had, if you're not too demanding. Schildkraut's Judas is fun to watch at times: Once, he even skulks away like Dracula with his face hidden by his cloak. His father, Rudolph Schildkraut, plays the sneering high priest Caiaphas, Victor Varconi is a suitably conflicted Pontius Pilate, and William Boyd, soon to make his name as Hopalong Cassidy, is Simon of Cyrene, who helps Jesus carry the cross. The storm and earthquake after the Crucifixion is a DeMille-style special-effects extravaganza. The cinematography by J. Peverell Marley leans heavily on filters and screens to cast halos around Jesus, but does what it can to bring DeMille's characteristic tableau groupings to life. Fortunately, the movie also goes out of its way to avoid arousing antisemitism: The crowds calling for crucifixion are shown to be largely made up of bribed bullies who are suppressing those who want Jesus released, and one man furiously rejects the bribe by saying that as a Jew he cannot betray a brother.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

HEDDA HOPPER’S HOLLYWOOD

January 10, 1960

Directed by William Corrigan

Written by Sumner Locke Elliott

Original Music by Axel Stordahl

Hedda Hopper (1885-1966) was born Elda Furry in Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania. She was one of Hollywood's most powerful and influential columnists. She appeared on “I Love Lucy” and “The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour.” Among her hundreds of films as an actress, she did two with Lucille Ball: Bunker Bean (1936) and That's Right – You're Wrong (1939). Hopper was best known for her flamboyant hats. She was also a well known conservative, Republican, and staunch supporter of blacklisting suspected communists. In films and television, Hedda Hopper has been portrayed by such actors as Fiona Shaw (RKO 281), Jane Alexander (Malice in Wonderland), Katherine Helmond (Liz: The Elizabeth Taylor Story), Helen Mirren (Trumbo), Tilda Swinton (Hail, Caesar!), and Judy Davis (“Feud”), to name a few.

Special Appearances By (in alphabetical order)

Jerry Antes (uncredited) was an actor with the Desilu Workshop who also appeared with Lucille Ball and Hedda Hopper on the Christmas Day 1959 “Desilu Revue” presented as part of the “Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse.”

Lucille Ball (1911-89) was finishing her run as Lucy Ricardo with the final episode of “The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour” airing in April 1960. She announced that she was divorcing Desi that very month.

John Barrymore (uncredited, archival footage)

Anne Bauchens (1882-1967) was Cecil B. DeMille's film editor for forty years. She won an Oscar in 1941. Bauchens edited Reap the Wild Wind (1943) and played herself in Sunset Boulevard (1950), just as Hopper did.

Stephen Boyd (1931-77) was an Irish-born actor best known for Ben Hur (1959), which won him a Golden Globe Award in 1960. In 1966 he played the leading role in The Oscar, which featured Hedda Hopper as herself.

Francis X. Bushman (1883-1966) was a silent film actor who received an honorary Golden Globe in 1960 as well as getting a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Coincidentally, Bushman played the same role as Stephen Boyd in the 1925 silent version of Ben Hur. Even more coincidental, Bushman was mentioned as Mrs. McGillicuddy's favorite movie stars in the same “I Love Lucy” episode that starred Hedda Hopper!

John Cassavetes (1929-89) was an actor and director who was then starring in the series “Johnny Staccato.” Later in his career, he was nominated for three Academy Awards.

Gary Cooper (1901-61) co-starred with Hedda Hopper in the 1927 films Wings and Children of Divorce, as well as the 1930 film The Stolen Jools. In 1942 he was featured in the third newsreel version of this TV special. In “Lucy Meets Harpo Marx” (1955) Lucy Ricardo dressed up in a Gary Cooper mask to fool her nearsighted friend Caroline Appleby. His name was also mentioned in two other episodes of “I Love Lucy.”

Ricardo Cortez (1900-77) was an actor / director who (like Bushman) got his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960. His final appearance was an episode of “Bonanza” which aired a week before this special.

Robert Cummings (1910-90) appeared on television with Hopper in “The Colgate Comedy Hour” (1955) and “Disneyland '59”, a celebration of the park's fifth anniversary. Cummings guest-starred in “The Ricardos Go To Japan” (1959, above) and on two episodes of “Here's Lucy.”

William H. Daniels (1901-70) was cameraman for 24 out of 26 of Greta Garbo's films.

Georgine Darcy (uncredited) was an actor with the Desilu Workshop who also appeared with Lucille Ball and Hedda Hopper on the Christmas Day 1959 “Desilu Revue” presented as part of the “Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse.”

Marion Davies (1897-1961) acted with Hopper in 1925's Zander the Great. This TV special marked the first filmed appearance by Davies since she had retired from the screen in 1937. It was also her last.

Walt Disney (1901-66) is the founder of Disney Motion Pictures and the Disney theme parks. He appeared on television with Hopper (and Bob Cummings) on “The Colgate Comedy Hour” (1955) and “Disneyland '59”, a celebration of the park's fifth anniversary. In 1956 he was on “The Ed Sullivan Show” with Lucille Ball.

Janet Gaynor (1906-84) won an Oscar in 1929. Between 1925 and 1930 she was in four films with Hedda Hopper. She was part of the group of 1960 recipients of a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Bob Hope (1903-2003) and Hedda Hopper first worked together in the film Thanks for the Memory (1938), the title tune of which became Hope's theme song for the rest of his career. In addition, they were together in “Hedda Hopper's Hollywood #4” (1942), “The Colgate Comedy Hour” (1955), three episodes of “The Bob Hope Show” and the film The Oscar in 1966. Hope and Lucille Ball did four films together as well as episodes of both Lucy and Bob's television shows.

Hope Lange (1933-2003) appeared in a 1957 episode of “Playhouse 90” hosted by Hedda Hopper. She was nominated for an Oscar in 1958 for Peyton Place.

Mario Lanza (uncredited / voice only)

Harold Lloyd (1893-1971) was considered one of the great silent film clowns of film history. He directed Lucille Ball in A Girl, A Guy, and a Gob in 1943.

Harold Lloyd Jr. (uncredited) was the only son of Harold Lloyd. He died after a massive stroke at age 34.

Suzanne Lloyd (uncredited) is the granddaughter of Harold Lloyd. She became a film producer nominated for a primetime Emmy.

Jody McRea (1934-2009) was the son of actor Joel McRea. He was most famous for his work in beach party movies.

Liza Minnelli (born 1946) was the daughter of Judy Garland and Vincente Minnelli, who directed Lucille Ball in The Long, Long Trailer. In the 1970s, she dated Lucille Ball's son, Desi Jr. She won an Oscar in 1973 for Cabaret. She was just 14 years old when this special was filmed.

Don Murray (born 1929) appeared with Hope Lang (his then wife) on Hedda Hopper's “Playhouse 90” in 1957, the same year he earned an Oscar nomination in 1957 for Bus Stop, also starring Lange.

Ramon Navarro (1899-1968) was a Mexican-born actor who appeared with Francis X. Bushman and Stephen Boyd in the 1925 silent version of Ben-Hur. He also acted with Hedda Hopper in The Barbarian (1933). Along with Bushman, Navarro was mentioned as one of Mrs. McGillicuddy's favorite movie stars in the “I Love Lucy” episode “The Hedda Hopper Story” (ILL S4;E20).

Anthony Perkins (1932-92) is probably best remembered as Norman Bates in Hitchcock's Psycho (1960).

Tyrone Power (uncredited / voice only)

Debbie Reynolds (1932-2016) is best remembered for the musicals Singing in the Rain (1952) and The Unsinkable Molly Brown (1964). Reynolds and Hedda Hopper both played themselves in the 1960 film Pepe. Lucille Ball and Reynolds appeared on talk and awards shows together. Her photograph was prominently seen on the cover of a movie magazine read by Lucy Ricardo on “I Love Lucy,” although her name was not spoken. Ironically, Hedda Hopper’s chief rival Louella Parsons is mentioned on the same cover!

Teddy Rooney (1950-2016) was the son of Mickey Rooney and Martha Vickers. In 1960 he did a number of television shows and films. He is the youngest participant in this special at age 10.

Venetia Stevenson (born 1938) is a British-born starlet whose career ended just one year after this special.

James Stewart (1908-97) was one of Hollywood's most treasured actors. He was an Oscar winner who was nominated again in 1960. Stewart and his wife Gloria were friends and neighbors of Lucille Ball's. He appeared on shows tributing Ball such as “All-Star Party for Lucille Ball” (1984) and “CBS Salutes Lucy: The First 25 Years” (1976). Celebrity voice artist Rich Little imitated Stewart on an episode of “Here's Lucy.”

Gloria Stewart (uncredited) was married to James Stewart in 1949.They had twin daughters, Judy and Kelly. Gloria also had two boys from her first marriage, Ronald and Michael McLean. Stewart starred in Roman Scandals (1933) which featured a young Lucille Ball. She later became famous again for appearing in James Cameron’s Titanic (1997).

Gloria Swanson (1899-1993) was a silent film star whose career managed to transition to talkies, something typified in the 1951 film Sunset Boulevard, which earned her a third Oscar nomination. Hedda Hopper played herself in the film.

King Vidor (1894-1982) was a film director who directed Hedda Hopper in the 1924 silent film Happiness.

Perc Westmore (1904-70) did make-up for The Life of Emile Zola (1937) and The Virgin Queen (1955). He made up Hedda Hopper on the 1932 film The Man Who Played God and did Lucille Ball's make-up for The Big Street (1942).

Bud Westmore (1918-73) did make up for Mr. Peabody and the Mermaid (1948) and Man of a Thousand Faces (1957). He did make-up for “The Jack Benny Show” when Lucille Ball appeared in 1964.

Wally Westmore (1906-73) did make-up for Barbara Stanwyck in The Great Man's Lady (1943). He also did make-up for Lucille Ball's films Sorrowful Jones (1949) and Fancy Pants (1950), as well as a 1968 episode of “The Lucy Show.” He also did make-up for four films starring Hedda Hopper.

Frank Westmore (1923-85) claims he put hair on Yul Brynner. It was for the 1958 film The Buccaneer.

In 1938, actress Hedda Hopper was given a chance to write a gossip column for the LA Times. It was called “Hedda Hopper's Hollywood.”

This also the title given to a series of six 9 or 10-minute documentary short films that accompanied feature films from December 1941 to October 1942.

In the second entry, Desi Arnaz was seen at the Mocambo. Although Lucy was mentioned, she didn't get any camera time.

The title was also given to a 1964 episode of “The Beverley Hillbillies” which featured Hopper playing herself.

In 2011, author Jennifer Frost used the title for her book Hedda Hopper’s Hollywood: Celebrity Gossip and American Conservatism.

Throughout the hour-long special, Hopper is never in the same frame with the celebrities. Rather she introduces 'talking heads' segments and uses voice-over narration to link them together.

The special was presented as part of NBC's “Sunday Showcase” (1959-1960), an anthology series of specials. In 1959 the series presented a “The Lucy-Desi Milton Berle Special” which featured Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz as Lucy and Ricky Ricardo, visiting Las Vegas. It was only one of two times Lucille Ball played Lucy Ricardo on NBC, rather than CBS. Their presentation of "The Sacco-Vanzetti Story" earned a 1961 Emmy nomination for Program of the Year. Richard Adler composed the opening theme music, titled "Sunday Drive."

The special opens with Hedda Hopper wearing one of her trademark big hats, strands of pearls and a fur stole, sitting on a scenic layby overlooking Hollywood in the valley below.

Hedda: “This is a story of my town. There's no town like it on the face of the earth. Because it's business is make-believe. And for over fifty years the people in this town have been getting up and going to work to to to tell the world a story. Down in that valley, some of them are busy crowning an emperor and some others are fighting the Civil War again. Somewhere else a band of cattle thieves are shooting it out with the sheriff's posse and two people who only met this morning are being married in front of an army of cameramen and crew for this – is Hollywood.”

Hopper says she's been in Hollywood for 21 years.

The scenes switches to a studio gate where Lucille Ball drives up. This is Desilu, formerly RKO, where Lucille Ball got her start. After phenomenal success on television, she and husband Desi Arnaz eventually bought the studios. The car stops in front of the Desilu Workshop, which Lucy says was inspired by the RKO workshops she attended as a young contract player, conducted by Ginger Rogers' mother, Lela. Lucy calls out to a few of the students waiting for her – Jerry [Antes] and Georgine [Darcy]. At the time, the group was preparing for a TV variety show to be broadcast on Christmas Day 1959 as part of “The Westinghouse-Desilu Playhouse,” the same anthology series that would present the very last “Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour” episode just four months later, bringing the end to an era. In return for this appearance, Hopper made a brief appearance as herself in the show, titled “The Desilu Revue.”

Lucy (about the Desilu Workshops): “We have paid audiences, because I feel a paid audience is a more demanding audience.”

Lucille Ball is also just weeks away from formally divorcing husband Desi Arnaz. Lucy talks about the special in the past tense as the special will air a week after the Workshop.

Getting into a golf cart, Lucy says she is on her way to “The Untouchables” set, where Nick Georgiadi is a series regular, and also a member of the workshop. She says she also has to visit stage 3 where Ann Sothern is rehearsing in order to convince her to use some of her workshop students. Sothern, a great friend of Ball's, was filming “The Ann Sothern Show.” Finally, Lucy says she has to check on some costumes at wardrobe.

Bob Cummings sits on a sound stage telling the story of how he was discouraged from pursuing an acting career. Despite this he got an opportunity that turned into the film Three Smart Girls Grow Up (1939). While filming this story for Hedda Hopper, his second TV series “The Bob Cummings Show” had just finished a five season run on CBS. A year earlier, he guest-starred in “The Ricardo’s Go To Japan”, a 1959 installment of “The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour.”

On another stage (actually the same set, slightly redressed), Anthony Perkins talks about young actors trying to carve a unique niche in Hollywood.

Four (of the six) Westmore Brothers, make-up artists from the Westmore dynasty, sit in front of a dressing room mirror. Perc, Wally, Bud, and Frank all reveal one of their famous make-up credits.

The scene shifts to the western street of a back lot. Jody McRae sidles up to disclose that he's working with his father (Joel McRae) on a series called “Wichita Town” (1959-60). Unfortunately for father and son, the series was canceled after just one season.

Inside a western street saloon sits Gary Cooper, who says his first talking picture was The Virginian (1929). The show assumes that viewers know who he is on sight, so Cooper does not introduce himself, nor does Hopper's voice-over. Cooper says some of his favorite films were The Pride of the Yankees (1942), Sergeant York (1941), Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), and High Noon (1952).

Cooper: “We used to wonder when the Western story material would peter out. Seems like it never will.”

In 1960, that may have seemed true, but by the mid-1970s the Western genre had gone out of fashion on screens big and small.

Cooper ends his segment with his trademark “yep” something he memorably did in the 1949 Warner Brothers picture It’s a Great Feeling. Hopper's voice over says that one of the best westerns he did was The Plainsman (1936), directed by Cecil B. DeMille. This leads to a visit to DeMille's library where we he planned “the dividing of the red sea” - a reference to The Ten Commandments (1956). We are introduced to his editor Anne Bauchens. DeMille died just one year before this program was filmed.

Hopper (voice): “Spectacle was Hollywood's cup of tea. From the San Francisco earthquake to William Wyler's chariot race.”

Hopper is referring to the films San Francisco (1936) and Ben-Hur (1959). At a table at The Brown Derby (actually a reasonable facsimile), Stephen Boyd, Ramon Navarro, and Francis X. Bushman discuss the spectacle of shooting chariot races in both the 1925 and 1959 films of Ben-Hur.

Bushman is strategically positioned sitting in front of a line drawing of Hedda Hopper. Both “I Love Lucy” and “The Lucy Show” set scenes at The Brown Derby. After their stories, the camera pans over to the next booth, where Hedda Hopper is sitting, listening. She is positioned in front of a line drawing of Mickey Rooney.

Hopper: “Thirty five years has passed between the first Ben-Hur and the one you're seeing today. You know, it wouldn't surprise me if they made another Ben-Hur sometime.”

Hopper's prediction came true in 2016 – 56 years later - when a brand new Ben-Hur was released starring Jack Huston as the title character.

Hopper (in front of her home): “You know, every morning when I go to work, I thank the good Lord I'm still alive. Like everybody else in this town I go to work and come home at night. There are many kinds of homes in Hollywood. This is mine. I bought it 17 years ago, and oh, I love it. I hope to go on living in it for the rest of my life.”

Paparazzi-style film captures Jimmy and Gloria Stewart leaving their homes and getting into the family car to go to out on a Sunday afternoon.

Next, the camera goes inside the home of Hope Lange and Don Murray, who is putting on a puppet show for their two children, Christopher and Patricia. Their marriage broke up the following year.

The camera takes the long trip up the driveway of the Greenacres, the palatial home of Harold Lloyd. The silent film star strolls out onto the portico with his son Harold Jr. and his granddaughter Suzanne (by his daughter Gloria) to wave for cameras. Hopper's voice over describes some of the home's charity events and parties with famous silent film stars.

Lloyd's wife, Marion Davies, dressed to the nines, says a few words of welcome. It marked her final filmed appearance. Davies was fighting cancer when she appeared on this show. It was her final film appearance.

Hopper: “Yes, there are still many great houses that belong to the glorious gilded days – before income tax.”

From real Hollywood homes, we are now on the back lot at MGM where the homes were used in the filming of Meet Me in St. Louis (1944) starring Judy Garland.

Ten year-old Teddy Rooney (son of Mickey Rooney) is discovered on Carville Street, where the Andy Hardy pictures were made by his father. Teddy says he is about to start shooting his first television series “Man of the House.” The show co-starred his real life mother, Martha Vickers, but only a pilot episode was ever shot.

Hopper is found sitting in a box at the Paris Opera House set from the original 1925 film version of The Phantom of the Opera starring Lon Chaney. Hopper hears voices from the past like John Barrymore, Tyrone Power, and Mario Lanza. While Hopper is listening to the voices, director John Cassavetes appears on the stage to tell her that they will need the set to rehearse a scene from his series “Johnny Staccato.”

Producer King Vidor talks about location shooting taking over for back lots. Downsizing of background artists is also the way of the future.

Gloria Swanson talks about the way films have changed for audiences and actors.

Debbie Reynolds (in the same dressing room occupied by Swanson) tells us how busy she's been and how she craves to get away.

As an example of how young starlets conduct themselves today [1960] Venetia Stevenson drives onto the studio lot in a tiny sports car, casually dressed, grabs her script and runs into the soundstage. Right behind her is a chauffeur driven Rolls Royce. A maid gets out holding a puppy wearing a huge bow. Hedda Hopper steps out of the car, bedecked in jewels and furs. “This is the way they used to do it!” The maid holds the train on Hopper's gown as she heads into the soundstage.

Hedda Hopper (without her trademark hat) says that only one person has the right to be called a Hollywood legend: Greta Garbo. Hopper shows still photos of Garbo in Anna Karenina (1935), Mata Hari (1931), Queen Christina (1933), and Camille (1936). Hopper played Garbo's sister in As You Desire Me (1932) and says that the reclusive star briefly let down her guard with her to reveal a warm and intelligent person.

William Daniels, Garbo's cameraman on 24 of her 26 pictures, says he hopes that she will return to the screen someday, to let a new generation appreciate her beauty and talent. Her last film before going into self-imposed retirement was in 1941. Hopper tells of Garbo's first (silent) picture, The Torrent (1926), where her leading man was Ricardo Cortez.

Cortez (above) recalls that Garbo was sensitive and shy, but a hard worker.

Walt Disney talks about Mickey Mouse, the first mouse ever to win an Oscar. Disney shows a still of Mickey's premiere in Steamboat Willy (1928) for $1,200. To balance out Mickey, Disney created a more mischievous character, Donald Duck. From there, Disney was able to produce Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), their first feature length animated film. That first Mickey Mouse cartoon also led to Disneyland and their upcoming animated feature 101 Dalmatians (1961).

Sitting in a void, 14 year-old Liza Minnelli sings “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” a song her mother Judy Garland introduced in 1939's The Wizard of Oz.

Janet Gaynor talks about winning the very first Academy Award in 1928 for Seventh Heaven, Sunrise, and Street Angel. These were her first three roles. Ever since, it has only been given for one performance.

Standing amid a pile of suitcases, Bob Hope talks about Hollywood in general, presenting almost a monologue on the subject. He riffs on make-up artists and then starts to joke about the investigations surrounding the quiz show scandals, which came to a head in 1959.

Hope: “I think they're going too far with this honesty thing. The other night on 'Wells Fargo' the heavies held up the stagecoach and gave back all the money from the week before.”

Hope: “Hedda has a fabulous fund of Hollywood knowledge. She knows whose who, who's where, where's what, and how, when, and where there's going to be some hoo-hooing. Hedda's a listener in the largest party line in the world. She has to wear those big hats to keep the secrets from leaking out.”

Hope: “I think Hedda's gowns are very colorful tonight. She makes the NBC peacock look like a beatnik seagull.”

Although this program may have been filmed and aired in color (most “Sunday Showcase” episodes were), it only remains in monochrome kinescope copies.

Back on the scenic overlook as the sun sets, Hopper sums up her feelings about “her” town – Hollywood.

Lucy Ricardo and Hedda Hopper

In 1952's “The Gossip” (ILL S1;E24) Lucy calls Ricky and Fred “Hedda and Lolly” after hearing them indulge in gossip about the Tropicana hat check girl. Lolly refers to Hopper's chief competition, gossip columnist Louella Parsons. Ricky usually pronounced her name Hedda Hooper.

In 1955′s “The Hedda Hopper Story” (ILL S4;E20), Lucy comes up with an elaborate plan conspire to get into Hopper’s column and get some much-needed publicity for Ricky. Little do they know that Lucy's mother has invited her over for tea.

Ricky: “Mother, darling. Why didn't you tell us it was Hedda Hooper?” Mrs. McGillicuddy: “You didn't ask me!”

To kick off “The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour,” a flashback to how Lucy and Ricky met was framed by an interview with Hedda Hopper in “Lucy Takes a Cruise to Havana” (1957). Desi convinced the network to extend the show by fifteen minutes for this episode. As a result, Hedda Hopper's framing interview is usually cut for syndication. Here Ricky finally learns how to pronounce Hopper’s name. Unfortunately, the apple doesn’t fall far from the Latin-American tree: Little Ricky greets her by saying “How do you do, Miss Hepper!”

This date in Lucy History – January 10th

"California, Here We Come!" (ILL S4;E13) – January 10, 1955

"Lucy and Art Linkletter" (TLS S4;E16) – January 10, 1966

"Lucy and the Chinese Curse" (HL S4;E18) - January 10, 1972

#Hedda Hopper's Hollywood#Hedda Hopper#Lucille Ball#I Love Lucy#The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour#Bob hope#Liza Minnelli#Jerry Antes#Anne Bauchens#John Barrymore#Stephen Boyd#Francis X. Bushman#John Cassavetes#Gary Cooper#Ricardo Cortez#Robert Cummings#William H. Daniels#Greta Garbo#Cecil B. DeMille#Georgine Darcy#Marion Davies#Walt Disney#Mickey Mouse#Donald Duck#Janet Gaynor#Steamboat Willy#Hollywood#Hope Lange#Mario Lanza#Harold Lloyd

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

<strong>Manslaughter (1922 / Paramount) (Sweden) <a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/klaatucarpenter/">by KlaatuCarpenter</a></strong> <br /><i>Via Flickr:</i> <br />The poster illustration is by Eric Rohman.

#Eric Rohman#Leatrice Joy#movie poster#Thomas Meighan#Lois Wilson#John Miltern#Julia Faye#George Fawcett#Edythe Chapman#Cecil B. DeMille#Jeanie Macpherson#Alice Duer Miller#L. Guy Wilky#Alvin Wyckoff#Jesse L. Lasky#Paul Iribe#Clare West#Anne Bauchens#silent#black & white#movies#illustration#fashion#1920s#advertising

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women Make Film – In More Ways Than One By Kim Luperi

“There is a forgotten history of cinema,” the trailer for Mark Cousins’ 14-hour documentary WOMEN MAKE FILM (2018) expounds, reminding viewers that thousands of women have directed movies over the past 13 decades. Today, TCM kicks off “Women Make Film,” an extraordinary three-month series framed around Cousins’ documentary showcasing the breadth of women’s contributions to cinema through 100 diverse films and filmmakers from 44 countries.

All of the directors represented exhibited the passion, drive and talent to cultivate their own vision in a male-dominated business. But it wasn’t always male-dominated; women have been there in all respects from the start, despite the fact that for decades historians, and even Hollywood’s own collective memory since the 1930s, have almost wholly neglected their contributions.

Here’s a look at three areas in which women made early inroads that deserve more recognition today. These are just the tip of the iceberg; many great resources are out there to learn more.

Editing

“One of the most important positions in the motion-picture industry is held almost entirely by women,” The Los Angeles Times wrote in 1926. Indeed, through the era of one-reelers, the technical and monotonous task of editing often fell to the deft hands of uncredited young women. With the advent of features (and later, sound), editing required a more intricate, creative technique, and the new technology brought more men into the fold, but women still contributed in big ways – see: Barbara McLean editing Mary Pickford’s first sound picture, COQUETTE (‘29).

The year the Academy established the Best Film Editing category, Anne Bauchens was one of three nominees (for 1934’s CLEOPATRA), and six years later, she’d become the first woman to win for NORTH WEST MOUNTED POLICE (‘40). Bauchens asserted in a 1941 interview, “Women are better at editing motion pictures than men,” alluding to their patience and a strong emotional sense that allowed women to connect with different stories and understand what audiences want. Many women held high-level supervisory editing positions at studios, including Margaret Booth (MGM, 1936-1969) and Viola Lawrence (Columbia, 1925-1960), opening the doors for later accomplished editors like Dede Allen, Thelma Schoonmaker and Anne V. Coates. Several directors represented in this series, including Dorothy Arzner, Leontine Sagan and Chantal Ackerman, worked as editors during their career, either cutting their teeth in the department on the way up or cutting their own work.

Cinematography

As opposed to editing, camera work has long been a male-dominated area. That said, the Women Film Pioneers Project online (WFPP) points out a “women with cameras” trend in the 1910s in which movie magazines highlighted actresses/camerawomen Grace Davison and Francelia Billington as rarities in this field. “I suppose that it is still a novelty to see a girl more interested in a mechanical problem than in make-up,” Billington remarked a 1914 Photoplay piece.

However, women in the newsreel and documentary worlds like Dorothy Dunn, Katherine R. Bleecker and Osa Johnson didn’t hesitate to pick up a camera and film. Outside Hollywood, Angela Murray Gibson, who ran her own production company in North Dakota, shot all of her own movies. But these women were among the few who engaged in such work for decades. As J. E. Smyth observes in Nobody’s Girl Friday, the American Society of Cinematographers accepted its first female member, Brianne Murphy, in 1980, and as of 2018, women make up only 4% of its membership. Progress is being made though, as Rachel Morrison recently became the first woman nominated for a Best Cinematography Oscar for MUDBOUND (2017).

Producing

Producers do a little bit of everything in the movie business, and the same could be said for women working during the medium’s early days. In an effort to gain creative control and develop the stories they wanted to see, several women set up their own production companies during the 1910s and early 1920s; in fact, according to the WFPP, more independent film companies were named after women – actresses, writers, director, producers – than men at that time. Though most of these companies were gone by 1923 due to a variety of factors, select notable films remain, like Marion E. Wong’s THE CURSE OF THE QUON GWON (’17), the first Chinese-American feature, produced by Wong’s Mandarin Film Company.

Women also held powerful producing positions at studios during the silent era, from Lois Weber running Universal’s Rex brand with her husband to June Mathis, who discovered Rudolph Valentino. Flash forward to the 1940s and 1950s, however, and only a handful of female producers operated in the studio system, including Joan Harrison, who produced on her own after working with Alfred Hitchcock, and Virginia Van Upp, best remembered for GILDA (’46). The tides have been changing, though: According to The Los Angeles Times, as of 2020 women make up 43% of the Producers Guild of America. Many directors included in this celebration have also produced their own work, including Jacqueline Audry and Lucrecia Martel.

#Women Make Film#female filmmakers#female director#editors#Cinematography#Dorothy Arzner#Coquette#Virginia Van Upp#Dede Allen#Thelma Schoonmaker#Anne V. Coates#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#Kim Luperi

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

"THE TEN COMMANDMENTS" (1956) Review

"THE TEN COMMANDMENTS" (1956) Review It has been a long time since I saw Cecil B. DeMille's 1956 movie, "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS". A long time. When I was young, my family and I used to watch the film on television, every Easter Sunday. By the time I reached my early to mid-twenties, I stopped watching the movie.

I spent the next decade or two deliberately ignoring "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS". One, I had pretty much burned out on the 1956 film by then. Two, I had very little interest in Biblical films. I still do to a certain extent. And three, my opinion of DeMille's movie had pretty much sunk over the years. By the time, I reached my thirties, I came to the conclusion that it was an overrated film. So . . . what led me to change my mind for a recent viewing of "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS"? To be honest, the recent release Ridley Scott's Biblical film, "EXODUS: GODS AND KINGS". Both the 1956 and 2014 movies pretty much told the same story - the exodus of Hebrews from Egypt, under the leadership of Moses. I eventually plan to watch "EXODUS: GODS AND KINGS". But out of curiosity, I decided to watch "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS" first. Anyone who has seen or heard about "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS" knows the story. Pharaoh Rameses I of Egypt orders the death of all firstborn Hebrew males upon hearing a prophecy in which a "Deliverer" will lead Egypt's Hebrew slaves to freedom. A Hebrew woman named Yochabel saves her infant son by setting him adrift in a basket on the Nile River. The Pharaoh's daughter Bithiah, who recently lost her husband, finds the child and adopts him as her own, despite the protests of her servant Memnet. Prince Moses grows up to be a part of Egypt's royal family. He becomes a successful general who wins a war against Ethopia and forms an alliance with the country. Moses falls in love with loves Nefretiri, who is the throne princess and must be betrothed to the next Pharaoh. He also becomes in charge of constructing a new city in honor of Pharoah Sethi's jubilee. But when his rival for the throne and Nefretiri's hand, Prince Rameses accuses him of being the Hebrew slaves' "Deliverer" after he institute reforms in regard to the slaves' treatment. Moses responses by showing the completed city and claiming that he wanted the slaves more productive in order to finish the project. Despite being on top of the world following his construction of the new city, Moses' privileged world is threatened when Nefretiri learns from a royal slave named Memnet that Moses is the son of a Hebrew slave. I now realized why I had stopped watching "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS" for so many years. I had simply burned out on the film. My refusal to watch the movie for so many years had nothing to do with its quality. I am not saying that "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS" is one of the best films ever made. Not by a long shot. "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS", quite deservedly, is known for its over-the-top melodrama, bombastic style and preachiness. But the one thing the movie is known for is the turgid dialogue that seemed to permeate the film. I cannot help but wonder if the screenwriters had disliked actress Anne Baxter or her character, Nefretiri. After hearing her spout lines like - "You will be king of Egypt and I will be your footstool!" - throughout the entire film, I am beginning to suspect that I may be right. Even the other performers - including Charlton Heston, Yul Brenner, Yvonne DeCarlo, Edward G. Robinson, Vincent Price, Debra Paget, John Derek, Judith Anderson, John Carradine, Martha Scott, Nina Foch and Sir Cedric Hardwicke - spoke their lines with a ponderous style that left me wondering if this movie had been shot at a slower speed. And to think, movie fans had to endure this ponderous style and turgid dialogue for slightly over three-and-a-half hours. Whew! However, my re-watch of "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS" made me appreciate it a lot more. I appreciated the epic feel of DeMille's movie, as he guided audiences into Moses' life - from Moses' birth to his glory years as an Egyptian prince, to his years as an outcast and shepherd and finally to his years as a prophet and conflicts with Rameses - all in great detail and glorious Technicolor. DeMille even took the time to delve into the romance of supporting characters like Joshua and Lilia. There are some epic films that can bore me senseless with a ponderous style and equally ponderous pacing. Yes, the dialogue for "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS" can be quite ponderous. But I cannot say the same for DeMille's pacing. I found his direction well-paced, despite the movie's 220 minutes running time. One of the aspects of "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS" that I found truly impressive was Loyal Griggs' cinematography for the film. Shot in glorious Technicolor, Griggs' Oscar nominated photography left me breathless, especially while viewing scenes such as those shown below:

I was also impressed by other technical aspects of the film. That last scene, which featured the parting of the Red Seas, led to an Academy Award for John P. Fulton, who had created the movie's special effects. That scene hold up pretty damn well after 62 years. "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS" earned Oscar nominations for Edith Head's colorful costume designs, Anne Bauchens' film editing, Sam Comer and Ray Noyer's set decorations; and for art directors Hal Pereira, Walter H. Tyler, and Albert Nozaki. What can I say about the movie's performances? Despite the ponderous dialogue, the performances seemed to hold up . . . okay. Charlton Heston earned a Golden Globe nomination for his portrayal of Moses. Granted, Heston projected a strong presence in his performance. But honestly . . . I would not regard Moses as one of his greatest performances. I merely found it solid. I was a little more impressed by Yul Brenner's portrayal of Ramses. He won the Best Actor National Board Review Award for his performance. Then again, Ramses proved to be a more complex and ambiguous character than Moses. As much as I liked Brenner's performance, it did not exactly blow my mind. Anne Baxter, who was already an Oscar winner by the time she did "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS", was saddled with some of the movie's worst dialogue. And there was nothing she could do to overcome the bad dialogue . . . well, except in two particular scenes. One of those scenes featured Nefretiri's discovery of Moses' origin as a Hebrew slave. And the other featured her character's angry goading of Ramses to take action against the Hebrews, following their son's death. I read that Paramount had submitted Yvonne De Carlo, John Derek, and Debra Paget as possible nominees for a supporting Academy Award. All gave pretty good performances; especially Yvonne De Carlo, who portrayed Moses' wife Sephora, and Debra Paget, who portrayed Lilia, the slave woman who seemed doomed to attract the attention from the wrong kind of men. But none of them received any acting nominations for their work. There were other solid performances from the likes of Judith Anderson, Sir Cedric Hardwicke, Nina Foch, John Carradine, Martha Scott, Henry Wilcoxon and Woody Strode. But two particular performances really caught my attention. Ironically, they were portrayed by Vincent Price and Edward G. Robinson, who portrayed characters that proved to be the bane of Lilia's life. Both gave interesting performances as two very oily men who use Lilia as their personal bed warmer - Price as the well-born Egyptian architect Baka and Robinson as the ambitious Hebrew overseer Dathan, who later proves to be a thorn in Moses' side. "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS" proved to be the last film directed by Cecil B. DeMille to be seen in movie theaters. The last in a career that by 1956, had spanned forty-two years. The director passed away over two years following the movie's release. Frankly, "THE TEN COMMANDMENTS" struck me as a nice high note for DeMille to end his career. Yes, one has to endure the extremely long running time, occasional bouts of over-the-top drama and ponderous dialogue. But the movie's visual style, first-rate story, excellent direction in the hands of a legend like DeMille and solid performances from a cast led by Charlton Heston; makes this Hollywood classic worth watching over and over again.

#the ten commandments#the ten commandments 1956#cecil de mille#charlton heston#old hollywood#anne baxter#yul brynner#yvonne de carlo#debra paget#john derek#vincent price#edward g. robinson#judith anderson#martha scott#john carradine#woody strode#henry wilcoxan#nina foch#sir cedric hardwicke

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Look up the history of film editing. It’s a literal example of all this shit happening in real life and it makes my blood boil.

Example from the Wikipedia on film editing

All those women at the end have passed away FYI. Women editors were the norm when it was considered technical work. Then once it started to be seen as creative with the ability to win awards most women got shouldered the fuck out. Like bye. Have fun on unemployment.

You might be thinking ‘cha that was like 60 years ago. It’s different now.’

Editing is still extremely dominated by men. Don’t believe me? Good. Never take shit at face value. That’s why I come with receipts.

Some of the most memorable films were edited by women. Example: Wizard of Oz was edited by Blanche Sewell. Also, as someone who knows the method they used to edit back then and just how WoO was done let me tell you. IT WAS A NIGHTMARE. A real kick to the face if you weren’t a canonized saint with patience given by a god.

She also died before it was released in theaters.

This is direct from her wiki:

“Noted by John Stanley Donaldson, protégé of Herbert Ryman, as having an “intuitive ability for cinematic pacing to strike the proper tempo and temperament.”

She was an influential woman of film during her lifetime.”

Never fucking heard of her though, huh?

Others that you might recognize are; Blue Lagoon edited by Thelma Connell, The Ten Commandments (yup with that gun fucker Heston) edited by Anne Bauchens, and Lawrence of Arabia edited by Anne V. Coates.

Yes there are a few, a fucking few women editors of note today. Maryann Brandon and Mary Jo Markey are JJ Abrams editors of choice. One of his only redeeming Hollywood choices of late it seems. They’ve done some amazing movies and no I’m not biased because of Star Trek!Reboot.

Awards for film editing have been given out since 1935 which was the start of it all. Some of the larger production houses started phasing out women as it was now deemed creative work not mere grunt work which LET ME TELL YOU until it went digital it was a pain in the DICK!

Have you ever had to do the dual VHS tape method? Ever spend 2 days editing a fucking 10 minutes skit only to find out you cut a clip too fucking long towards the beginning or used the wrong clip or the audio is fucked? Now you have to start from scratch. This makes you want to go full rage fiend thus giving you the ability to throw that junking usual machine out the nearest window.

ANYWAYS

Majority of editors back then were women yet majority of the awards were won by men. This still holds true. In the 84 years they’ve been given this award only 9, fucking 9 different women have won. Thelma Schoonmaker has won 3 times because she is a badass.

Overall editing is STILL a hard fucking industry to get into if you’re a woman. Because some shitbags deemed it a creative job and women just don’t know art. 🖕🏻

one thing that has always bothered me about theatre, and broadway especially, is that ever since i was little theatre has always been “a girl’s things”. it’s shown as girly and young boys who are interested in theatre are assumed to be gay or are made fun of. and yet, in major theatre productions, you hardly ever see women. women aren’t known producers, they aren’t recognized playwrights and composers, and plays- mostly musicals- hardly ever have more than two female characters in the spotlight. it’s yet another “girl’s thing” that’s dominated by men.

#dont at me and my film editing degree#was told by one of by professors that I was an extremelt talented editor but Id never get an editing job#this is why i sign all emails when talking to video editing clients with my initals#are they a Larry or a Laura#bet you 20 bucks you thought i was a Larry#i love film editing and im damn good at it#too fucking bad asshats won’t hire me#now im working on an 11 year compuyer with a program thats 8 years out of date#and i can still edit circles around some of the bastards hired in my stead#delirium speaks#film#angry rant#angry feminist#🖕🏻

83K notes

·

View notes

Link

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY LINDA TRAN TUTOVAN / GETTY IMAGES MAR. 2, 2018 AT 3:03 PM Why Did It Take So Long For The Oscars To Nominate A Female Cinematographer? By Walt Hickey Filed under 2018 Academy Awards At the second Academy Awards, in 1930, Josephine Lovett and Bess Meredith each received nominations for writing — the first women nominated for nonacting Oscars. It would be a few more years — the seventh Academy Awards in 1935 — until a woman was nominated for film editing (Anne Bauchens for her work on “Cleopatra”). Eventually women were recognized in other categories too, including art direction (1941), music scoring (1945) and costume design (1948). In 1973, at the 46th Academy Awards, Julia Phillips became the first woman to be nominated for producing a best picture nominee, “The Sting.”1 A few years later, in 1976, Lina Wertmüller became the first woman nominated for best director. Women were first nominated in the 1980s and 1990s in new categories for makeup (1982) and sound editing (1984) and old categories like visual effects (1986) and sound (1995). But before this year, cinematography held out — the last category with zero women among the nominees.2 According to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences database, 238 people received nominations in cinematography for their work on 638 different films from the first through 89th Oscars. And not a single one of them was a woman. That changed this year. Rachel Morrison, who was nominated for her work on “Mudbound” — and whom popular audiences around the world are now meeting thanks to the blockbuster “Black Panther” — has broken the last glass ceiling at the Oscars. That achievement is massive, but what on earth is wrong with cinematography that it took so long? The first part of the answer is easy, and we already have it: Hollywood’s gender parity behind the camera is even worse than in front of the camera. In December, a team of us at FiveThirtyEight wanted to find a new way to evaluate how diverse and inclusive movies are on gender and race ��� a “Bechdel Test” for the next generation — so we reached out to professionals and creators who work in the movie business to ask what they thought audiences should be looking for in films. We graded films across a whole suite of metrics — how female characters were treated or developed, how supporting casts were built, how the extras and crowds were framed, how films portrayed black women and Latinas. But no metric made Hollywood look worse than the gender composition of behind-the-scenes and on-set crew. Here’s the test from Jen White, a director of photography:

1 note

·

View note

Text

Female Editors From the “Talkies” Era (1929-1940s)

The editors mentioned previously who began in the silent era, Margaret Booth and Anne Bauchens, continued to work all the way through the “talkies” and into the 50s/80s. Dorothy Spencer and Barbara McLean are two more female editors renown for their work. The transition into the “Talkies” was a tough change for editors - it meant you had less flexibility with the edit in order to keep the sound in sync. The style of editing during this period was predominantly continuity editing.

Dorothy Spencer

Birth/Death: 1909 - 2002

Years Active: 1929 - 1979

Nationality: American

Editing Career: At the age of 15 she got into the film industry doing entry-level jobs (shadowing negative-cutters and serving tea/coffee) at the Consolidated-Aller Lab in 1924. Between 1926 and 1929 she was uncredited assistant editor for several directors, such as Frank Capra (who later directed Its a Wonderful Life 1946) and Raoul Walsh (Founding member of AMPAS, and described as a “Hollywood Legend” by IMDb). She joined Fox studios’ editing department in 1929. in the 1940s Spencer took on a solo editing role where she worked with Hitchcock and other directors. She has a total of 75 credits.

Notable Works: Stagecoach 1939; Foreign Correspondent 1940; Lifeboat 1944; Cleopatra 1963; A Tree Grows in Brooklyn 1945; Earthquake 1974.

Awards/Nominations: Nominated for Best Film Editing four times - Earthquake 1974, Cleopatra 1963, Decision Before Dawn 1951, Stagecoach 1939. She Won a Career Achievement Award in 1989.

Notes: She was known for a traditionalist approach adhering to the classic rules of continuity editing.

Barbara McLean

Birth/Death: 1903 - 1996

Years Active: 1924 - 1969

Nationality: American

Editing Career: In 1924 McLean married a film projectionist and cameraman, where soon after, she found a job as an assistant editor at ‘First National Studio’ in LA. Fist National Studio became 20th Century Pictures in 1933, and in the same year McLean got her first credit as editor. In 1935, 20th Century Pictures became 20th Century Fox, and subsequently McLean was promoted to editor-in-chief. McLean remained with 20th Century Fox until her retirement in 1969. In that time, she was granted full authority over the studio’s film edits, and has a total of 64 credits.

Notable Works: Les Miserable 1935; Alexander’s Ragtime Band 1938; The Rains Came 1939; Jesse James 1939; The Black Swan 1942; Wilson 1944; All About Eve 1950.

Awards/Nominations: 6 Nominations for Best Film Editing - Les Miserable 1935; Lloyds of London 1936; Alexander’s Ragtime Band 1938; The Rains Came 1939; The Song of Bernadette 1943; All About Eve 1950. Winner for Best Film Editing for Wilson 1944.

Notes: A 1940 issue of the Los Angeles Times declared, “Barbara McLean, one of Hollywood’s three women film editors, can make stars — or leave their faces on the cutting room floor.” This shows how much influence she had as a film editor.

0 notes

Photo

Zelig (1983) was edited by Susan E Morse. Susan has 41 editing credits so far, from 1978 to 2017. She worked with Woody Allen from his Manhattan to Celebrity and was Oscar nominated for Hannah and Her Sisters.

Throughout Hollywood film history, the technical department most likely to employ women is in editing. From Anne Bauchens (63 editing credits 1915-1956 and an Oscar winner for Northwest Mounted Police (1940)), Viola Lawrence (99 editing credits 1916-1960, two Oscar nominations and work with Orson Welles (The Lady from Shanghai and Howard Hawks (Only Angels Have Wings), Anne V Coates (54 editing credits from 1952 to 2015 and an Oscar winner for Lawrence of Arabia), Verna Fields (1960-75 and an Oscar winner for Jaws), through Thelma Schoonmaker’s work with Martin Scorsese (three Oscars for Raging Bull, The Aviator and The Departed) and Joi McMillon (25 editing credits so far and an Oscar nomination for Moonlight (2016).

Google “female film editors” for numerous articles and many more names.

1 note

·

View note

Video

instagram

VFX breakdown of parting red sea The ten commandments (1956) Directed and produced by Cecil B. DeMille Editing :Anne Bauchens Cinematography :Loyal Griggs Budget :$13 M Box office : $122.7M #vfx #vfxstudio #vfxshowreel #vfxanimation #vfxsupervisor #vfxfestival #vfxbreakdowns #tencommandments #vfxindia #vfxindonesia #vfxjapanaward2018 #vfxcompositing #vfxmakeup https://www.instagram.com/p/B4GmpI9nzA2/?igshid=1e6qjw6w9ec24

#vfx#vfxstudio#vfxshowreel#vfxanimation#vfxsupervisor#vfxfestival#vfxbreakdowns#tencommandments#vfxindia#vfxindonesia#vfxjapanaward2018#vfxcompositing#vfxmakeup

0 notes

Text

The Editor Behind Scorsese’s Classic Movies

Thelma Schoonmaker is an editor – perhaps the editor, in this case. She’s won three Oscars, and she just received an honor at the BAFTAs. Though she’s happy about the push for more diversity in Hollywood, she says, “People think there were fewer women in Hollywood than there were. … After all, Cecil B DeMille’s editor, Anne Bauchens, actually won an Oscar, and DW Griffith worked with Margaret Booth, and Alfred Hitchcock’s films were edited by his wife, Alma.” – The Observer (UK)

Article source here:Arts Journal

0 notes

Text

Hedda Hopper's Hollywood (1960)

Hedda Hopper’s Hollywood (1960)

Hedda Hopper’s Hollywood (1960)

Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper takes us on a tour of Hollywood and interviews the stars of past and present. Featuring appearances by: Lucille Ball, Anne Bauchens, Stephen Boyd, Francis X Bushman, John Cassavetes, Gary Cooper, Ricardo Cortez, Bob Cummings, William Daniels, Marion Davies, Walt Disney, Janet Gaynor, Bob…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

#WHM2018 Day 1 • ANNE BAUCHENS Film Editor 1882-1967 Anne Bauchens was one of the early pioneering women editors in Hollywood. After moving to New York to pursue a career in acting, she worked for playwright William de Mille and later for his younger brother Cecil B. DeMille. DeMille taught Bauchens how to edit film in 1915, and after 1918 she edited all of his films for the next 38 years. At the time of her retirement in 1956 with her last film ”The Ten Commandments,” Bauchens had edited more than 60 films over the course of her career. • #AnneBauchens #editor #filmeditor #WomensHistoryMonth #womenshistory #WHM #history #film #filmmaking #filmmaker #filmhistory #Hollywood #OldHollywood #GoldenAge #womeninfilm #womeninentertainment #entertainment #entertainmentindustry #bosslady #womenkickass #girlpower #representation #representationmatters #passion #dreambig #aimhigh #workhard

#bosslady#womeninentertainment#whm2018#whm#goldenage#history#aimhigh#workhard#editor#filmmaker#representation#filmeditor#girlpower#womenkickass#representationmatters#oldhollywood#womenshistorymonth#hollywood#entertainmentindustry#womeninfilm#annebauchens#film#passion#entertainment#womenshistory#filmmaking#dreambig#filmhistory

0 notes

Text

Made it home in time to watch the Mutiny on the Bounty outro and idk I think it’s a missed opportunity to highlight other movies under the Trailblazing Women banner. I’m a big proponent of shining a light on behind the scenes artists who aren’t directors of course but it still feels odd that their schedule is borderline/not so borderline male centric.

On the TCM Trailblazing Women homepage there’s like a link to join the 52 Films by Women campaign on twitter which is great but unless I missed something none of the movies they chose were directed by women! I know they abandoned focusing on that aspect of filmmaking last year too but gee whiz! I’m surprised they didn’t want to close out really, really strong. Also I’m 97% sure the first series they did was done twice a week. I lost interest last year when they only concentrated on actresses which to me mostly meant they were just gonna show their usual catalog of films but with a concentration on certain actressses which is I feel is something they do a lot.

I thought the first series was a real breathe of fresh air that featured a solid number of tcm premieres. Now it’s the likely the last time they’ll do this sort of thing and they’re gonna show Taxi Driver (one of three Scorsese movies in the series!!!), Back to the Future, and the Elephant Man. Yes, women did do excellent work on those movies but do we really have to see those movies on TCM again?

On the bright side, the previously mentioned Madam Satan played earlier tonight which was not only edited by a woman (Anne Bauchens) but the screenplay was written by a woman (Jeanie Macpherson), the dialogue by two women (Gladys Unger, Elsie Janis) and starring Kay Johnson. Yes, now if you’re gonna show a movie directed by a dude then that’s the kind of movie that should be highlighted!

They will show the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) and They Won’t Believe Me (1947) later this month. Two great gems.

Overall it still seems like a missed opportunity and this is a minor pet peeve but if you click on main homepage and then click on Month Highlights neither link mentions Trailblazing Women which despite this wtf thankfully has its on web page but still! There’s a big banner saying 34 classic horror films!! I won’t even dare count how many movies they’re gonna show during this LAST run of Trailblazing Women series but I’m guessing it’s less than 34. Just a real wtf.

#also after listening to like five intro and outros I wish they had a historian on the panel too#hell a panel panel would’ve been nice#they have couches and I’m sure they have a table so include more than one guest#without the historian you have guests and hosts being saying I think this happened way too many times#anyway it’s a small thing compared to what’s going on in the world but it’s still something

0 notes