#and you thought fundamental logic is so abstract exactly because it is more general than just numbers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Surprising absolutely noone except undergraduate math students, it turns out math actually is only about numbers in the end!

#math#mathblr#mathematics#oh so you thought abstract algebra stopped being about numbers to get to more complex structures#and you thought fundamental logic is so abstract exactly because it is more general than just numbers#well guess what#gödel wants to have a word with you#my friend every statement that can possibly be made by humans ever can be made isomorphic to some structure of the natural numbers#even if that structure is a function space of the power set of the power set of the natural numbers#it is possible to write any finite set of axioms as an isomorphism to axioms about the natural numbers#however since the axiomatic definition of the naturals gives you some axioms already it is important to note that for some really fucked up#axiomatic systems you have to explicitly include axioms that prevent you from using thise axioms in sone ways#as in you can't use the set theorethic definition to choose elements of a set for example#you have to choose elements from a set with choice functions constructible from axioms provided#now for making set theory equivalent to the naturals the choice functions you can derive are equivalent to just choosing a natural#but it could be not the case

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 9: Troll Time

Time to get trolled.

https://homestuck.com/story/1527

This is the first of the events that I’ve noticed enough to talk about in Homestuck that alludes to the Alpha Kids. While Roxy on the other side of the scratch is the one actually responsible for the disappearance of Jaspers and the Pumpkins, at this point in the story, we have some pretty good suspects for exactly who disappeared both of them.

I could see myself guessing that Jade’s penpal is one of the trolls, but it wouldn’t be my first guess. I’m going to pay close attention to all of the events on one side of the scratch that are caused by the other side of the scratch, because my theory is that a Scratched Universe, more than anything else, is really terminated rather than truly being retroactively erased. Too much doesn’t make sense from a causal perspective (not necessarily from a temporally linear one) if a scratched universe is actually erased entirely, or even if it is closed off from the rest of existence - why can information enter and leave a Scratched Universe at all from an outside perspective, for example?

Are Side A Side B teleporters, appearifiers, and so on and so on, loopholes? Maybe it has something to do with the nature of Void, the Furthest Ring, and their seeming exclusion from the rules the rest of Paradox Space is required to follow.

The Doylist answer, which in Homestuck is also allowed to be the Watsonian answer, might be that while a Scratched Universe is *materially* erased, information about it is still permitted to propagate through narrative contrivances such as the author. Fenestrated planes can easily be considered narrative contrivances, but if we use this as our theory, it seems like Appearifiers and Sendificators would also have to be Narrative Contrivances (which I’m going to spell with a capital NC from here on out.) I... actually don’t have a problem with this hypothesis, so it’s what I’m going with. Also, since a friend of mine who’s reading this liveblog asked, I’m going to post a link to the tvtropes article on those two terms at the start of this paragraph for anyone who doesn’t know what I’m talking about.

Perhaps, given the proclivity for the Void to preserve lost information in the form of dreams and memories, and given the nature of Space as the medium through which events normally propagate (as well as the fundamental medium of storytelling from which all other storytelling mediums derive their medium-ness), and their proximity on the Aspect Wheel, Narrative Contrivances are objects which have are shared between these two domains - as objects associated with the Void, Narrative Contrivances are permitted to follow their own set of rules which to someone outside of the universe are obvious, but to anyone inside the universe are a complete black box, and as objects associated with Space, Narrative Contrivances function as a means by which to propagate information in such a way as to preserve causality, the logical topology of Paradox Space, and with them, the self-fulfilling nature of Paradox Space. They allow the world-line of objects travelling through the narrative to remain consistent, even when they would violate material geographical conventions.

This description of Narrative Contrivances makes me think a lot of things could be Narrative Contrivances, like First Guardians, for example, who can violate the speed of light.

This is all a lot of silly bullshit, but it’s fun to come up with theories to describe and predict Homestuck (and future Homestuck works, even though I’m not terribly invested in them.)

This has been a long Cold Open. More after the break.

https://homestuck.com/story/1529

John gets cyberbullied!

Man. Cyberbullying has really gone from being an individual concern to being an apocalyptic issue. Who knew? Maybe in writing the trolls and their cyberbullying as being inextricable from the apocalypse, Andrew Hussie predicted this.

I’m not trying to understate John’s issues by comparing them to stuff like massive social media disinformation campaigns - receiving Death Threats as a thirteen year old is terrifying, and on a general level, the fact that this kind of horrible shit was commonplace in the earliest days of social media should have been a big indicator that what was yet to come was going to be so, so much worse.

I’m also not trying to jocularly exaggerate the threat that almost completely lawless social media has on society. If you haven’t already, check out the excellent documentary The Social Dilemma, and then delete your Facebook account if you haven’t already (and since you’re reading my extremely anti-capitalist anti-patriarchy liveblog on tumblr, you’ve probably already done that. If you have, good for you!) And your twitter for good measure, come on, you know who you are. Mabe your tumblr too while you’re at it.

Cyberbullying is part of a larger theme in Homestuck, another one of those things that it’s Capital A About. As a work that is not only about growing up, but specifically about growing up in the information age, Homestuck is repeatedly about the ways that Social Media don’t just bring us together, but keep us apart from one another. Cyberbullying is one of the effects of Social Media pushing people apart - it’s so, so much easier to threaten to kill someone when you don’t have to look them in the eye while you’re doing it, and when you have the anonymity of a string of alphanumeric characters as a name to hide behind.

https://homestuck.com/story/1537

The Black Queen is a very bad woman. It’s always intrigued me that the Queens allow their counterparts’ agents free movement through their territory like this even on the eve (or the advent?) of full-scale war between their kingdoms. PM is just allowed to wander around Derse unsupervised.

I suppose that if even God and Satan can afford each other a bit of token civility while discussing the fates of sinners, so can Prospitians and Dersites.

https://homestuck.com/story/1542

@zeetheus John’s definitely proceeds Rose’s bluh.

Rose sips her Mom’s martini for the same reason that she later falls prey to alcoholism. Trying to grow up without help, Rose interprets the martini as a symbol of parental authority, the same way that she interprets the partaking of beverages in general as being a ritual of intimacy with her Mother. Empty signifiers.

https://homestuck.com/story/1549

Jack Noir’s grating voice is so outrageously distracting that it prevents itself as an intrusive thought in the Narrative for PM.

Actually, come to think of it, *all* of the Carapacians talk pretty much exclusively via narration. I wonder if that’s representative of an altered relationship with their narrative reality, which is the first time ever I’ve had that thought pretty much at all.

I always just chalked it up to one of the quirks of Andrew’s writing style, but especially when we take into account the fact that Homestuck is as metanarrative as it is, and that Carapacians are the only characters in Homestuck Proper who interface with the narrative prompt except for the audience, Andrew, and Caliborn himself, I can’t help but wonder. Maybe as living gaming abstractions, in spite of their limited intelligence and abilities, Carapacians have a unique relationship with the narrative laws of Paradox Space (perhaps in the same way that Narrative Contrivances do?)

https://homestuck.com/story/1569

Riffing a little more on the “Fetch Modus as analogous to thought processes” motif previously introduced, Jade’s excellent visualization abilities and vivid imagination serve her well as a Space Player, but tend to misfire, running wild, and seeing patterns where they don’t exist (intrusive thoughts make her see Johnny 5 in her Eclectic Bass and whatever the fuck mecha she’s about to accidentally imagine, I don’t know, I’m not a weeb.) Jade sure does think about robots a lot.

https://homestuck.com/story/1579

I have to say, I consider Terezi’s manipulative abilities to be genuinely pretty strong. I have never known a better way to strongarm me than by pointing out traits that I don’t know whether I feel good or bad about - it just terminates my thought processes.

Although in John’s case, it helps that he is, in fact, a weenie, a stooge, and most importantly, a nice guy. All these facts make him extra manipulatable.

https://homestuck.com/story/1584

<3

I have no reason to believe everyone in Homestuck’s universe isn’t stupidly badass, but I choose to believe that no one is as stupidly badass as the leads because it makes me happy to imagine that these kids are just ridiculously OP superhumans.

(That said, it’s kind of fucked up the level of violence that these literal children are involved in, maybe I shouldn’t get so excited about it. Should we be enthusiastic about the kids’ triumph over their dangerous enemies? Horrified by the travails they are being put through? Probably both motherfuckin’ things.

https://homestuck.com/story/1588

I think about this page a lot.

Rose Lalonde is a very dangerous young lady. She is ruthless, pragmatic, calculating, and cool. She’s even a killer, and literally just killed two imps before fighting this Ogre!

Why is she choosing to show mercy to it now? Is she just trying to get Dave’s goat? Maybe the answer is, deep down, she doesn’t really want to hurt anyone or anything.

https://homestuck.com/story/1589

Kanaya and Dave have a great relationship and I love them as friends very much. I wish dearly that there was more of them in the webcomic. They have approximately the same relationship with authenticity, which is to say that they don’t have an insincere bone in their respective bodies, but practice insincerity nonetheless to impress someone they care about.

For Kanaya relating to Rose, I think it’s a lot more innocent.

https://homestuck.com/story/1590

The least eloquent character in Homestuck has his brief, and I’m pretty sure only encounter with the most eloquent character in Homestuck.

Poor, poor Tavros. While Rose is pretty much always on this level, it seems a lot more innocuous when she’s talking to her friends, or the more mean-spirited and (relatively) competent trolls, the way she treats Tavros almost feels like bullying because of how obviously pathetic he is.

That said, he turns right around, and invokes exactly what’s coming to him. Y’know as much as Tavros is an authentic abuse victim and Vriska gaslights him into thinking a lot of the bad things that happen to him are his fault, there are a lot of times where he does stupid shit that invokes the justifiable wrath of the people around him.

https://homestuck.com/story/1592

While I could pontificate about the fact that Kanaya and Rose are my favorite couple, and squee enthusiastically, instead I will call attention to the fact that, by way of mixing her metaphors, Kanaya has been the victim of an authorial pun - she’s a Fruit Ninja. (Unless Fruit Ninja didn’t exist at the time of writing? It may very well not have.)

https://homestuck.com/story/1596

As the Page of Breath, Tavros sucks at communicating. Here, he sucks at communicating because in spite of his objectively pretty sick rhymes... he is talking to someone who just can’t be arsed.

https://homestuck.com/story/1602

This is one of those absurd moments that at first blush seems meaningless, but I think helps to decipher the kinds of things that John Egbert cares about. It’s one of the moments where he ritualizes an action that one of his heroes takes - John Egbert thinks that Nic Cage is cool, and wants to be like him, so he roleplays Nic Cage for a little while.

https://homestuck.com/story/1603

We’ve barely met the trolls, and they are *already* using the humans as a convenient method to troll each other instead of staying on task.

Karkat also establishes his love of RomComs before his introduction even rolls around.

https://homestuck.com/story/1618

Conceding ground to implacable enemies is generally the correct means to win in Homestuck, usually by getting them to destroy themselves or each other purely by their own unsustainably wicked or stupid conduct. Only a being as powerful as Lord English is sufficient to destroy the Significance-hoarding antagonist that is Vriska, as she threatens to overshadow everyone else in the universe by her own inflated self-importance. Only Vriska, so arbitrarily lucky, could possibly get into position to destroy Lord English. They were made for each other. They deserve each other.

One of my favorite dialogues in the whole comic. Man, I sure love Act 4. There’s something indescribable about the dialogue Andrew writes for this part of the comic. Homestuck at its best whiplashes from silly to scary to heartbreaking to heartwarming, and back to silly again, from beautiful to ugly, and I don’t think that even Act 5, as it piles up layers upon layers, well past the number of parts needed to make a whole, captures the essence of Homestuck as well as does Act 4.

Homestuck is different in every part, of course, and for everyone who says that Act 4 is peak Homestuck you will meet someone who says that Acts 1 through 3 were peak Homestuck, or who says that Act 5 was Peak Homestuck, or that Act 6 was Peak Homestuck. I do not mean to demean any portion of the work by saying that Act 4 is my favorite. The things I like in Homestuck the most are just the most themselves in this portion of the story.

https://homestuck.com/story/1627

I’m feeling less and less intelligent as I read more and more of Homestuck, because honestly, my theories read less like honest-to-god insights, and more like somebody who just wasn’t paying any fucking attention. Here, Jade spells out basically what I’ve been saying.

https://homestuck.com/story/1640

We’ll pause here for the evening. Reading was a little sparse today, but it’s a good place to leave off, especially since for some of these I wrote just stacks of theorizing.

Until tomorrow, Cam signing off, Mostly alive except for a bit of a cough, and not alone.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflecting the Author

Ok, now referencing this post and, more importantly, the video behind it for a broader subject, the opening quote gets me thinking.

I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations… I much prefer history - true or feigned - with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader and the other in the purposed domination of the author.

-JRR Tolkien

This dovetails nicely with other opinions I have heard that trying to force a meaning on readers tends to malfunction. Along with the idea that trying to make a direct reference to current events tends to only last as long as the current events while making something more universal can reflect current events and then go on to reflect other later events as well.

The problem, I suspect is in the definition of allegory though I also suspect JRR Tolkien is right now turning over in his grave to snap at me, “Did I F*ing Stutter?”

Allegory can be the metaphorical recreation of other culturally significant stories by characters, figures, or events as a reference within a narrative, drama or picture. Aslan acts out the Christian narrative of Christ’s sacrifice. It’s not meant to be interpreted any other way. That is the purposed domination of the author as in the quote. C.S. Lewis has a specific interpretation that he wants the reader to walk away with.

But Allegory can also be the broader representation of just abstract ideas or principles by characters, figures, or events in narrative, dramatic, or pictorial form. A form put in to the story by the author without a demand for a specific interpretation.

This is one of the things I fold under the idea of MORAL. That if I make my text reflect the idea that “Power Corrupts,” then any time the real world throws up that truth - and I wouldn’t use it if I didn’t think it was true - then the story incidentally mirrors the real life events and feels more real because of that. The abstract representation and the real world events mesh to create something stronger than I feel I could create with purpose.

And here I think this may be what Tolkien might mean by applicability. That instead of trying to reproduce a unique event in metaphor, it may be a stronger tactic much of the time, to apply the lesson of the event. In the video about the ring, Power is Corruptive as a statement of principle. The internal logic of the story states that as fundamentally true and hews close to it.

One of the things I loathe about the Peter Jackson movies is that Faramir succumbs to the corruptive influence of the ring rather than being resistant as he is in the books. I get why the movies did it. Philippa Boyens has been clear that they did it to preserve dramatic tension that they didn’t think they could keep if Faramir simply helped Frodo. And it doesn’t actually contradict this principle. Faramir is corrupted by the opportunity for power, it’s just interpersonal social power, the capability to force his father’s affections by deeds, rather than a desire for rulership or military might. And that has merit and is a good discussion.

But I loathe it because it takes away one of the very few contrary sophistications of that moral. What Tolkien himself expresses is much closer to the idea that power corrupts but that also the refusal of power insulates you from corruption in an unequal way. You may still get power thrust upon you but the lack of corruption makes it possible then to be a “good” wielder of power. Tolkien shows over and over again that those who wish power the least are the most effective at wielding it.

That’s not terribly controversial. But Tolkien goes the extra mile with it, particularly with Faramir, changing it from a vague moral based on a general truism to something he actually personally believes. And I think that’s a fair part of Tolkien’s authorial power. Tolkien is a monarchist, he did believe in the concept of the good king and what made one, which means the application of his ideals ring true not only in the work but also as applied to the real world. It’s fairly difficult to work oneself around from reading about Faramir and Aragorn to the idea that the very idea of monarchical power is bad.

Which I think is the other element: the more you, as the author, buy it, the more you, as the author, delve into the idea to the spaces where you do not share the general opinion, the more polished your reflection will be because it is brightened by specific application.

I can see this in my own work. One of my constant struggles is getting into the morality of my character JJ. I love JJ. AND I am under no delusions that she is a good person. JJ was originally designed to be a monster and she is. So, the question becomes, what do I say morally about her. And I feel that the application, the reflection that peers deepest into me, even where I am very uncomfortable, so that it will reflect brightest to others is putting in my own actual attitude toward her. That she is awful AND she gets away with it. JJ doesn’t get punished. JJ isn’t defeated. JJ gets loved, treated like a hero, and vindicated. Which I honestly feel guilty about. And would not want expressed as a moral, little m. I dislike that monsters just get away with it. That they might even succeed because of it. But that statement also feels true. And by looking at how she gets pardoned that to me gives a greater reflection of who we are if not who we would like us to be. It also generally means that what I produce will not look like what someone else produces because I’m not quite falling in line with either usual camp.

And for many others, who might be trying to depict thinly veiled political leaders, that deep dive might be better reflective for you as well. I am definitely not saying to excuse them in your work. But by getting deep into where you are uncomfortably comfortable with how they run things if it were somebody else and by getting deep into where you might be uncomfortably comfortable with how their opposition acts, even though it might not be exactly that political leader, it might end up reading as many more and reflecting better how you view it all.

The point, I think, is that by delving deep into what you personally deeply feel, good or bad or both, you’ll generate something much more resonant than you will by taking the prepackaged allegory of someone else’s story that most people might already have made their moral decision on.

It’s a thought anyway. Or at least a ramble.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

happy sunday, everyone! keeping in the vein of characters, we’d like to give you all a sneak peek of our member groups!

the member groups of zero sum are based off the infinity stones. in general, these groups are rooted in a fundamental concept that is important to the character. for this reason, it’s paramount to think about the character’s motivations when choosing a group, rather than personality traits which may not always line up perfectly. if you have any questions about these groups, feel free to message and admin and we’ll help you pick out one for your characters!

MIND

these are the most cerebral of the group, bound by their desire and pursuit of knowledge. these are individuals who are rational to a fault, completely guided by their need to learn and figure everything out. they can’t settle for ‘close enough’ or ‘maybe.’ these are individuals who think faster than they speak, who have a better grasp of language than most, who sometimes get lost in themselves searching for answers. they are introspective, thought provoking individuals whose depths are boundless. they live in a world of definites - sometimes contradictory ones. they don’t see gray, only one shade or black or white. these are individuals who appreciate closeness and the nuisance and knowledge that comes with it. they value lasting friendships, because figuring people out can be hard, time consuming, difficult even if some of these individuals are known for enjoying a good challenge. these are individuals who are calm under pressure, rational to the end, and always analyzing situations to discern a plan. at their worst, they become consumed by their quest for knowledge. at best, they freely share it and know exactly how to walk away from a problem they can’t solve even if reluctantly. aesthetics: firewood, smoke, loves the sea but hates lakes, contradictive, articulate, well-read, introvert, wants to live in a cabin, tea over coffee, game of thrones, smiles at strangers, inside jokes

POWER

people who belong in the power member group are those who are both longing for or seeking power as much as those to win the respect and admiration of those around them, creating power. at their best, these individuals are focused, pragmatic leaders who know how to rally people to their side and inspire those around them. at their worst, they are tyrannical controlling individuals who seek power for power’s sake. these individuals tend to be ambitious individuals who will not fall short of their goals regardless of the obstacles in their way. theirs is the will and power to drive through them and reach their destination. loyalty is optional and many have fallen by the wayside as individuals have sought more of that very thing that yearn for and the very thing that could easily be their downfall. power is a fickle thing, it can be given and it can also be taken away. these individuals often struggle with relinquishing that control and as such, are often controlled individuals themselves - individuals who will never let you see them break, not even for a moment. sometimes, they have a reputation of being heartless individuals, but nothing could be further from the truth. they may be driven, but they are driven by something. whatever that singular source might be - an idea, an event, or even a person. power cannot come from nothing. aesthetic: blood, spearmint gum, morning person, plays to win, dinner parties, high connections, direct flights, red lips, doesn’t smile, will break for their dream.

REALITY

reality is often disappointing. for these individuals, they know that best of all. While some reject the reality in front of them, vehemently, some relish in the possibilities available to them. they are unafraid of hard truths and much prefer to see the ugliest, dirtiest parts of the truth rather than be blinded by the beautiful lie. these are people that strive to see beyond the illusions and smokescreens people put up, because they’ve been lied to. because they’ve been hurt by the beautiful lie and know that pain well enough to never desire to see it happen again. these are individuals who appreciate and respect the fine arts, more so than other groups, because these individuals see the beauty in absolute creation - new realities, new ideas, new developments. at their worst, they can be cold, brutally honest people whose bluntless leads to friction with others, who determine that living without lies is better than finding truth. at their best, these individuals are creators, confidants, who relish wit, intelligence, and honesty above all. aesthetic: sleeping in, space dust, believes in aliens, misses vine, laughs loud, would marry their best friend, surrealist/abstract art, museums, they’ve been hurt before but are still so full of love

SOUL

those in the soul member group are emotionally driven individuals. some recognize this and have mastered their emotions, using them as a guide. others are a slave to them, unable to break away from it. they are emotional, sometimes temperamental individuals who feel deeply, whether it’s healthy or not. they are people attracted to the simple pleasure of things, chasing experiences and pursuing meaningful, lasting relationships. these are loyal individuals who value those around them, immeasurably, and will do anything for those around them. these are the true empaths of our groups, who instinctively discern the feelings of others and naturally come to their sides to comfort and console. at their worst, these individuals are entirely ruled by their emotions to the point of self-destruction - too kind, too gentle, too breakable. they are gossamer strands against the wind. at their best, they are the greatest supporters of those around them who have rich, well-developed ties. most of the time, they are somewhere in between. aesthetic: feels everything too deeply, sensitive, loyal, sunflower fields, late afternoon sun, dancing under a full moon, decent grades, pretty handwriting, small towns, old cathedrals

SPACE

we define space by how much they create around them. how little or how much, it doesn’t matter, but they are marked by it. these are individuals who either share too much of themselves - vulnerable to a crippling point, clingy, unable to let go of those they love even if the sentiment is not returned or they are those who have created too much space, built too many walls, and hide in their ivory towers away from those that could harm them. these are people who live for moments of sheer freedom, who thrive in dangerous situations and come alive in the dark. they can be smart and logical or spontaneous and free, but they all crave to create more space or remove it. sometimes, they are stuck between the two. these are individuals who cannot be contained or controlled, maintained or immobilized. they don’t always follow orders well and have a habit of breaking more than a couple of rules without much fear of the consequences that wait for them on the other side. they are the stargazers, the dreamers, the individuals constantly looking up at the sky and thinking about how they’re going to get up there, planning their next trips, and striving to make each day a little bit better than the last. aesthetic: thunderstorms, hair slicked back with an insane amount of product, new york at night, adrenaline, early morning jogs, physics, fast cars, doesn't know where they are going until they get there

TIME

those ruled by time are individuals who can be completely stagnated - held and imprisoned by some idea or themselves or an event that refuses to let them go. they are, effectively, stuck. while, they can also be forward-thinking futurists who lack be ability to live in the present or look back for any reason ranging from the horrors they’d rather not face or a place they simply do not fit. these are individuals who can be loners, isolated for one reason or another. they rally around the things that bring them joy, sometimes too much. these are wise individuals who have seen much and learned even more. at their worst, they are cynical individuals who can’t see the joy between the horror and at their best, positive forward thinkers who strive to create change, but all are never naive. even if their lives have been short, none know what it means to live “easy.” aesthetic: ancient souls, audrey hepburn movies, dusty books, classical music, soft smiles, natural makeup, probably plays piano, bakes, walks so softly you can barely hear them, trying their best to be happy

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

How do you think Zant and Ghirahim would interact? Likewise, how do you think Ganon would treat the two in a setting where we could explore such a relationship?

My particular read on Zant is he’s not wild about social interaction unless he’s already decided the person is okay; I interpret him as the specific flavor of autistic where he’s only really comfortable in a social situation by shadowing a particular person for comfort’s sake. In which case I think he’d have a lot of sideways interactions with other people, but, not a lot of super direct engagement.

Ghirahim superficially is much more polite, but, given his particular complex relationship with his master and his childhood (a friend of mine, @golvio draws a lot of comparisons between how they imagine Ghirahim’s treatment under Demise and the Pearls in Steven Universe) it’s just that- superficial. He wants to be well-mannered because he feels keeping up aristocratic airs is an imperative he has to justify avoiding, but unless something really catches his intellectual curiosity, he, scientifically speaking, tends to not give a shit.

So I feel like you could have Ghirahim and Zant cohabiting in the same area and just sort of operating with a mutual regard to not say anything to each other unless the other’s hair is on fire and someone else isn’t already intervening. They could absolutely take more interest in each other, but, they’d need to at least get shoved into some kind of buddy cop adventure story to shake the topic loose. Just leaving them around each other, they’d never get anywhere. They would politely ignore each other. You would ask Ghirahim what he thought of Zant and after asking you to clarify who you’re talking about, he would make an idle note of “So that’s what his name is.”

With regards to Ganon and Zant, I sort of like the vein that Hyrule Warriors took with it in the sense that Ganon seems to regard Zant as a protege and student- not something as warm as “like a son” but that’s because Ganon’s not exactly the type to hand out familial affection very easily if at all. I imagine him taking a sort of scholarly, educational angle; Zant is his apprentice. Even if the guy lives for centuries, he’s significantly younger than Ganon himself, so there would be a certain degree to which Ganon looks towards Zant as someone in need of guidance, rather than a peer and equal.

That’s not to say Zant doesn’t impress him, or ever surprise him; Ganon might have a certain compassion for the downtrodden but he doesn’t seem the type to have patience for slackers or the talentless in his inner circle. But there’s definitely a distance between them, that would be altogether reinforced by the overly-reverent pedestal Zant puts Ganon on, though I think as time goes by and they had more time to interact with each other, or even just Zant operating on his own for a time because Ganon hasn’t been resurrected yet, he’d become a little less starstruck by Ganon, for the better- creating an environment where they can actually talk to each other and Zant isn’t fountaining the glories of his god, because Ganon might be cocky but I think the last thing he’d want to be is someone’s deity.

That would also affect Ghirahim; not the mentorship, because Ghirahim is one person who can not only match Ganon in age but actually surpass him- though I think this would average to them seeing each other as peers because the gaps in Ghirahim’s resurrections are much larger and they’re both at a certain level of time abyss where what’s a century give or take, actually- but the thing where Ganon has no particular desire to be regarded as a god. Distant reverence is fine on paper- it certainly flatters his ego- but in practice it just means people project a lot of expectations and perceptions onto him and that would make him shift a little uneasily in his skin considering the whole situation he had as king of the Gerudo.

It also doesn’t help that the person Ghirahim would be reminded of looking at Ganon is Demise- there’s no way to ignore that Ghirahim would be comparing Ganon to Demise. And the thing about Demise is, they are, in brief, an abusive tyrant; Ghirahim is someone deeply marked by the fact that he was raised from the cradle to disregard his personhood and feelings for Demise’s benefit.

This is completely counter to how Ganon operates, and would be a wall he would inevitably run into hard, dealing with Ghirahim- Ganon’s nice and cozy with Zant as a protege because Zant has all of his hopes and desires right there on the surface. All Ganon has to do is play the genie in the bottle, feed those hopes, encourage them, and, when Zant becomes more of a favored student than a useful tool, he can still use them to prop Zant up. Zant wants to feel powerful, Zant wants to feel valued, heard, supported- Ganon knows exactly what words to cook up to feed a flagging spirit.

Ganon operates selfishly on a certain level, and, he also works best with others who are also operating selfishly- not necessarily maliciously, but, what do they want? They want something for themselves.

Ghirahim is a standout among many Zelda antagonists in that he really doesn’t want anything. His resurrection of Demise is because he sees it as his responsibility. If he attaches emotions to it, it’s that he’s pleased to feel like he belongs, like the world makes sense, like he’s filling his role, and then, slowly, that he’s actually a bit curious about this person who’s so good at thwarting him.

But that’s one selfish desire, and it’s clear Ghirahim writes it off as a petty and ridiculous thing. Him, wanting things for himself, even if it’s something as simple as having the pleasure of figuring out who the hell this twerp in his way is.

And I think Ghirahim’s sense of self-denial would logically be a lot harsher any context in which he’s interacting with Ganon- because Ghirahim would have to deal with the keen awareness that Demise threw him away. He is not alive now because of Demise’s grace, but as an oversight, in a world Demise may well be incapable of returning to, and the sense is that this is just fine to them; they don’t need him or want him back.

I can see Ghirahim falling into step behind Ganon if he’s at a particularly low point and just needs to feel like someone actually wants him to be here, whoever that is, but I also feel like Ganon would galvanize Ghirahim in interesting directions- because coming from someone who is inevitably going to superficially remind Ghirahim of Demise, Ganon’s entire stance is going to be “but you’re a person, you’re made of metal and you’re a sword, that’s great, I’m largely made of meat slime that grows eyes, physiological construction is completely irrelevant here, the point is, you think, you have opinions, and no matter how hard you’re trying to pretend you don’t, you want something.”

Ganon focuses on the idea that people want things. He himself is so driven by this you could argue that his less-corporeal forms are basically one big grudge spirit. While textually, Ganon’s dying words in Ocarina of Time and Demise’s curse intend to mirror each other, it’s worth noting how Ganon’s words are basically pure spite- while Demise’s curse is methodically, systematically worded, functionally aloof; it’s the patient explanation of an adult to someone they perceive as a none-to-bright child that no, actually, you haven’t won anything of meaning. You’ve inconvenienced them. And they will not forget that you did that.

So Ghirahim would inevitably initially see Ganon as an entity similar to Demise, and that perception would inevitably come utterly torn down around the edges because Ganon and Demise are such fundamentally different people.

Frankly, my perception of Ganon and Demise is their relationship is comparable to that between Hylia and Zelda- the first Zelda was bodily born out of Hylia, making her a sort of mortal-incarnated demigod, but, the more Zelda became aware of Hylia, the less she was able to stand Hylia and was repulsed by Hylia’s thought process and the way she viewed Link. That’s continued through all of her descendants; Breath of the Wild Zelda suffers a huge amount of misery trying to connect with Hylia only to be given a repeated cold shoulder, and even awakening her powers, it’s only to be a pawn in the face of Hylia’s scheme.

Hylia is, in short, Zelda’s sort-of removed divine mother, and, she’s also an incredibly cold, neglectful parent.

I think the same goes for Demise and Ganon- they in a sort of abstracted manner had a hand in Ganon’s origin, but, this isn’t a family that could so much as sit through a very uncomfortable holiday dinner. And this is relevant to Ghirahim, because Demise’s treatment of Ghirahim obviously aligns with a lot of Demise’s attitude as a creator and towards the world in general- an attitude they actually share with their sworn enemy, Hylia. (both Fi and Ghirahim are ultimately discarded once they’ve “served their purpose” in the eyes of their respective creators)

Ganon, conversely, is heavily drawn towards the suffering outcast, and, as I talked about in my long post about what Ganon’s healing power means about him, that draw isn’t “I can exploit this” nearly as much as it appears to be genuine compassion. A lot of his narratives and behavior suggest that he feels that way himself- that as someone who has spent much of his life marked as a pariah, he has a certain visceral empathy for the discarded.

More than Ganon would not want to treat Ghirahim the way that Demise did, he would be loath to tolerate someone who treats fully loyal servants like Demise does. If Ganon stabs someone in the back, it’s because he’s either sure they would do the same in a heartbeat or because from his perspective they’ve already put a dagger in him. He’s not the kind of person who gets rid of someone he knows would never betray him, or has no reason to believe they’d do so.

If anything, this makes me wonder if Ghirahim would initially find Zant revoltingly whiny and needy- he can’t imagine why Zant would utterly humiliate himself and Ganon both by drawing Ganon’s attention to his needs and wants, or even just openly expressing distress in front of Ganon.

And then after a while Ghirahim starts to feel a little weird watching them interact because the fact that Ganon actually responds to Zant and encourages him, or even just, irritably orders someone to see Zant to his bed after the latter’s magically overworked himself, would just sort of start to contextualize for Ghirahim the gaping void of affection or even basic care that he received in his own development.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

SNK 115 - “OMW”

I mean...

Let’s be real. As far as Deus Ex goes, I’ve seen more preposterous this week.

If any of you are wondering why this post took so long, it isn’t for lack of time I assure you. This chapter was…a lot. And god damn, Isayama, I wasn’t expecting to dig up my Junior Year debate notes for this one blog post but here we are lads. Quick recap before we get into writers’ mumbo-jumbo.

Flashback

Deus EX

#HeelFloch

Sad Hange

RESURRECTION

We all know Isa loves his religious imagery. He isn’t quite as egregious as Zack Snyder (who is, tbh?) but it’s definitely a thing. He also loves mythology of all types. And while Norse mythology seems to be his area of expertise, it isn’t mine - which is why seeing Stupid Sexy Zeke emerge from his Titan Incubator made me think of another Stupid Sexy God from the Ancient Greek Canon.

I speak of the Goddess Aphrodite, who has dominion over love, beauty and its various trappings. Admittedly, this comparison is drawn in relation to aesthetics only. Zeke’s aloof temperament doesn’t really mirror that of the Greek goddess. Even though Aphrodite did technically help start the Trojan War but that’s neither here nor there.

Zeke’s appearance from the steam of the felled Titan is nearly identical to the foam that appeared during Aphrodite’s spontaneous conception in the Ionian Sea. For the sake of transparency, I must point out that long ago, a fanfic author by the name of Homer relayed to us that Aphrodite was the daughter of Zeus and Dione. This is not technically wrong but it is quite boring. And it was also pre-dated (shout-out to Hesiod). Uranus, the primordial god of the sky, got into a spat with his children as deities are wont to do. This particular dust-up ended in Uranus being castrated by his son – the Titan, Cronus – who usurped the throne. The disembodied testicles fell into the sea like a pair of primordial bath bombs and out of the resulting effervescence appeared a full-grown Aphrodite in all of her Tumblr-banned glory.

Zeke, with nothing left of him after the explosion than a head and torso, was taken into the gut of a waiting Titan. Let me clarify, here. He was not eaten, no. The mindless titan scooted itself along the river banks and inserted the dying Zeke into its stomach cavity. Then OG Ymir with her trademark PATHS Magiks, crafts the golden boy a brand new body and sends him on his merry way.

Like I said up top: of all the examples of Deus Ex, this isn’t even the third-most severe I’ve seen. The implications of it are…a lot. And it actually makes sense if you consider what we know about Titan Biology.

Back to the beginning. Once upon a time, the Founder Ymir Fritz made a deal with the Devil of All Earth that gave her untold power after coming into contact with the “source of all living matter.” With that power, Ymir became the Progenitor of Titan Power. Upon her death 13 years later, her soul was split into nine pieces and connected via a metaphysical system known only as PATHS. These PATHS transcend space and time and bind together every subject of Ymir, even those who have been long dead.

We also know that the Titans themselves are a conundrum of theoretical physics. Their mass and energy are created from nothing. They generate massive amounts of heat, but don’t appear to need fuel. They have no digestive system and regurgitate the contents of their stomach when it becomes full. Even though they are huge creatures, their actual limbs and body parts are incredibly light. Even though Zeke has little recollection of what happened to him post-explosion, he’s likely smart enough to infer, as we can, exactly how and why he emerged from the carcass of a Titan with a brand new body.

This is all before we mention that Zeke Jaeger is a part of the Fritz family tree. The Royal Family line that descends directly from Ymir herself.

I also thought about Lazarus of Bethany while reading this section. Lazarus was a good friend of Jesus, the lad from Bethlehem. Maybe you’ve heard of him. Jesus was told that Lazarus had fallen ill, but has business and doesn’t set out until a few days later. Jesus and his crew arrive in Bethany only to discover that Lazarus has already passed away. This leads to the Gospel’s shortest verse.

Jesus wept. [John 11:35, KJV]

Perhaps the better comparison for her is to Abraham (with the whole “making a great nation” stipulation). But! I’m trying to do something pithy here, so bear with me.

The story of Lazarus might be the Good Book’s most well-known resurrection (besides that other one). The idea here is that the world’s most Holy Figure decided that this man’s time on Earth wasn’t done. Jesus was too late to heal Lazarus and felt so guilty as to weep. Lazarus was then called forth from his tomb, still wrapped in his death robes.

For the Eldian Empire, no figure is more Holy than Ymir Fritz. She’s the Founding Titan and, if this chapter is to be inferred upon, her spirit still influences the will of her subjects to the day. An entire cult has formed with the sole purpose of returning her to her former glory. I should also point out that Zeke essentially committed suicide.

Like, yeah, maybe the injuries were a bit too extreme for an old shifter to be able to regenerate from, but even if that’s the case there would have been the telltale signs of an attempt to do so, like Pieck in Liberio. There wasn’t even that. He was so tired of the fight – so done with Levi torturing him – that he was willing to abandon his years-long plan entirely and sacrifice his powers to the shadows of death. He chose to die; the Founder chose differently.

The rainstorm clearing to make way for the sun. The beautification of Zeke Jaeger. The visage of his tall, strong frame standing firm as his hated rival lays broken and mutilated at his feet. It’s all very hard to miss. Who knows where his head is at following this? I do, however, finally know why I get so many Spidey Sense tingles whenever Zeke opens his mouth.

The name is Immanuel Kant: German scholar and one of the godfathers of modern philosophy. I first learned of Kant and his teachings as a teenager on my high school debate team as I prepared my cases for the Lincoln-Douglas competition. It was my first tournament and I placed second out of dozens of students. After I was done for the day, a girl came up to me and gave me congratulations for understanding Kant. I thanked her, but the truth was that I didn’t fully grasp Kantian philosophy until I got home that night and studied a bit more. Kantian ethics can be hard to grasp because they are often in conflict with each other. (Gee, that sounds familiar.)

Kant’s ethics are deontological in principal. This is a fancy way of saying that the main concern is the Deed That Must Be Done. It is a separation of morals from emotion. Kant rejected the Utilitarians of the day and their schools of thought regarding the inherent “goodness” of an action. Specifically, he had a big problem with Determinism, saying that things like free will were inherently unknowable; also, basing the morality of a decision around perceived outcomes was impossible, because consequences existed outside of physical existence and therefore could not be quantified. Kant set out to quantify the question of moral relativism with his most famous work: The Categorical Imperative.

This is a terribly complex system that has been repurposed and reinterpreted countless times over the past two centuries so I’ll spare you any ballywho. Basically, CI is the inverse of Consequentialism where everything but the consequences matter. Saving a person from drowning isn’t inherently a good action unless there is a logical reason for doing so. This is admittedly a very simplified summation, but even the expanded version leads to some dissonance of reason.

If we look at the Abstract of Categorical Imperative, it tells us: “Do not impose on others what you do not wish for yourself.” This line is very similar to the Golden Rule, which Kant famously opposed. The American scholar Peter Corning pointed this out, saying, “Kant’s objection is especially suspect because the Categorical Imperative sounds a lot like a paraphrase…of the same fundamental idea. Calling it a universal law does not materially improve on the basic concept.” To borrow an idea myself, it’s like playing the Super Mario theme in a minor key. It’ll sound more dour than usual, but it’s still the Mario theme. Joking aside, what’s important here is that the whole point of CI is to quantify the question of morality and it appears to do that in part by using the qualitative philosophy of the Golden Rule.

Another big beef came from Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard. He felt that Kantian autonomy was insufficient in holding people to the standards of CI’s universal truths. In his words: “Kant was of the opinion that man is his own law – that is, he binds himself under the law which he himself gives himself. Actually, in a profounder sense, this is how lawlessness or experimentation are established.” In other words, if the only thing that matters is reasoning, you can justify almost anything to serve your immediate reasoning.

EXAMPLE

Here is where the dubious nature of the Categorical Imperative fully rears its head, as it displays BOTH the morality and immorality of Zeke’s plan.

On one hand, this plan is fucking awful. There are numerous and many arguments to be made against it; working solely in the context of Kantianism, it is irrational to presume that sterilizing the Eldian people will lead to a more peaceful world. It relies on a ludicrous number of assumptions – the least of which isn’t that Marley will one day stop being a total bell end. Besides that shit, it violates the nature of Kantian philosophy by attempting to foresee the outcome of the situation.

The other hand? It actually makes sense. CI says that only reason matters. It’s ethics through the lens of rational thought. No matter your thoughts about the Great Titan War, how it started and ended, whether or not the Eldians’ preceding subjugation was just or not, it’s a fact that the Titans have caused a great deal of suffering for many people. Only one race of people can transform into these beasts, so the idea of stripping their ability to reproduce isn’t a great leap to make. It is rational specifically in the context of this universe.

(Apologies for any details missed. I haven’t read any Kant in several years and this is a very condensed version of a concept I would encourage you to look into further. Thinking about this all now, the fact that I ever made it to out-rounds while arguing any of this is frankly absurd.)

It makes sense then, finally, why Yelena is so devoted to Zeke’s plan. Titans destroyed her home and slaughtered her people. The rational course of action is to remove this weapon from the hands of those (Marley) that would abuse them. And if those same perpetrators get screwed over during the course of this plan then…[Shrug Emoji]. She claims what she wants is justice. What she really wants, of course, is revenge. Just like her sensei, Jaeger-san, who wants revenge still. Which Jaeger, you ask? The answer is yes.

Situations have been reversed. The volunteers (and Onyankopon) are seated at the head of the table while the officers of the Garrison and Military Police that held them captive are under their thumb. Color-coded armbands are divvied out to the Eldian forces, juuuuust in case you forgot which period of history we’re sending up here. Armbands are assigned based upon when a person surrendered to the Jaegerists. Those higher ups (and Falco) that partook of the wine get their own special armband, because Everything Is Awesome!!

Then there’s this fucking guy. Before I revisited the world of epistemology, I had a much less astute take prepared about character psychology and the concept of the “Double Turn.” I may still write that as a separate post; it won’t do any good here. Reiner didn’t appear, firstly (even though it appears that he and the Warrior Unit are on Paradis), and the visage of a disembodied child using Titan Magiks to bring Zeke back from the precipice of death brings up some very real questions about how real the Curse really is. We don’t know how Ymir Fritz died originally. Given the way mythology tends to work, I’d say patricide is highly plausible.

As usual, all we can do is speculate. One thing that doesn’t need speculation is Pieck. As usual, she’s right on time. As expected, she’s exactly right.

Stray Thoughts

- As I noted last time, Levi was sent flying into the river. Evidently, he had enough strength to make it back to shore, just not much more than that. I suspect he’s alive for now but, goddamn did he get messed up. Levi underestimated Zeke’s suicidal tendencies, just as Zeke underestimated Levi’s tenacity. For two fellas that spent months in direct contact with each other, they have almost no clue.

- Not to stir the pot here but, here’s an in-story example of Kantian Ethics in case you’re still not quite sure. On the roof in Shiganshina – if Kant had been there (lol) – he would have disputed Levi giving the serum to Armin. Not for the reason you think. Categorical Imperative is all about reason. The reason Levi chose to save Armin is because he refused to rob his loved one of their humanity and instead chose to let him rest as opposed to reviving him for the sake of continuing a senseless, endless war. As Momtaku has said before: Levi chose Erwin over Armin. This was a choice made on emotional, borderline selfish, grounds and thereby irrational, which in Kant’s eyes makes it immoral. Just a little extra nugget for you. Discuss, friends!

#snk meta#shingeki no spoilers#snk 115#zeke jaeger#levi ackerman#hanji zoë#floch forster#floch is even deeper in the bag#eren jaeger#gabi braun#pieck#still exactly right#yelena#onyankopon#philosophy#snk speculation#ymir fritz#question mark#kant and friends#mythology#'that's a neat trick mr. zeke!'

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pure waste of bandwidth

A few Girard-inspired, mathematical-theological stories for my friends.

Voting for itself. Girard dismisses the Hilbert’s programme, comparing the attempt to prove mathematics using mathematics to “the parliament voting for itself”. It is a correct comparison, yet its value as a criticism is ambiguous. As a french logician, Girard might actually know that the French Republic – and arguably the modern politics – has actually been founded with the parliament voting for itself. In 1789, the new-founded National Assembly of France was concerned with the question, whether it actually does represent the general will? This question was resolved affirmatively by the notorious Abbé Sieyès, who took the structure of his argument from the catholic thinker Nicolas Malebranche.

Malebranche was concerned with proving prothestants wrong, as catholics usually are. The problem was, whether the Catholic Church, that is, its body of cardinals was the one, unique representation (in the yet religious sense, from which we will later found the legal concept of representation) of God on Earth – as opposed to the possibility of the multiple, partial, conflicting representations of his will favored by the protestants. His thought experiment was simple: “Say we gather all of the cardinals together and let them take a vote, whether they, together, do or do not represent the god’s will. The ones who say ‘no’ are obviously not real cardinals: you can’t be a cardinal if you don’t believe in the institution. So everyone who is a real cardial will say ‘yes’, thus determining by unanimous vote that the Catholic Church is indeed the one and unique representant of God”.

Now let us postpone the matter of the obvious begging-the-question; let us also not indulge for now in the beautiful ways with which Malebranche tries to fix it; let’s focus on how this argument is still at work in our very lives. Abbé Sieyès used this very same argument to prove that the Assembly is the real representative: if your particular will is against it, you’re just not of the Republic and your will doesn’t count. The whole seeming ridiculousness of the argument pales in comparison with its incredible effectiveness: the modern politics was born with all its representative-democratic weirdness. There’re likely philosophical ways to ground this idea onto something more fundamental, yet the notoriousness of such an ouroboric event is clear, and the break that happened here is on the level of a new self-supporting thought from which, however, the ‘real things’ are being created on a daily basis.

Can’t we say that Hilbert’s programme is the same type of event, just imposed kind of retrospectively onto the history of mathematics? The mathematics voting for itself, let the naysayers be damned into luddistic hell? In this case we can go on living with its theological form while embracing the fruitful mathematical content it gave us. And then our next move, the move of the ones who dares to respect and use mathematics without believing in it, should obviously be to look for the heretics and the heretical thoughts. We should not be content with those who just dismisses mathematics altogether (the boring, impotent atheists) – the real heretic is the one who is of the mathematical practice, but questions its belief structure. How do you call the hagiography but about heretics? Heretography?

Hysterizing the computer. Now one of those heretics is Brouwer, whose whole project was about questioning the givenness of the a priori. Insane idea, completely against Kant, of course, as it questions the very distinction between thinking and praxis. A priori as something completely given assumes some kind of a collapse of the process of thinking in time, with all of the theorems already there somewhere, indeed nothing more than Anselm’s ontological argument, but about mathematics. Brouwer scouted this a priori and found his own fixed point theorem, which states that there’s something that exists but can’t be found. Now that’s unsettling for Brouwer who is, by the way, of a Schopenhauer’s persuasion. To question the whole thing, Brouwer looks for the most extreme point of this a priori givenness, and it’s nothing else but the law of the excluded-middle: it’s only there if you can always do the anselmnian jump to the farthest conclusion. Brouwer slows down this seemingly instantaneous jump by denying it, inventing the intuitionistic logic, and actually somehow manages to get pretty far with it, reformulating even a part of topology in this new light. However this heresy was not approved by his holiness Hilbert, already too influential on the continent – isolated Brouwer loses his mind and dies, never seeing any hope of his work being useful.

A different development was up at the same, however, concerned a piece of metal to be called computer. There were a few of those machines already, and it was obvious that there’s going to be more. On the other hand, it didn’t actually take very long for people to notice how incredibly useful the intuitionistic logic was for this machine: much more than the ‘classical one’. The computer became the redeeming object of Brouwer’s logic – he never saw one, never even thought of one, yet turned out to provide the most important concept for its study. The depth of Brouwer’s premature contribution to Computer Science is beyond the wariness of tertium non datur: his work predicted the notorious problems with the floating-point numbers, and his topology turned out to be a weird tool to study computable functions, which is a cross-sub-disciplinary link of strange awesomeness for the easily excitable people like me.

So if we’re desperately looking for any escape from the horrible weight of the Kantian-Hilbertian mathematical theology, shouldn’t we look into the computer? One of the weird things about the computers is how easily we all were persuaded, not so long ago, that everything in the computer is “virtual” (not in the sense in which philosophers use the epithet, but in the sense the marketers use it), that is, not exactly material… Which is nonsense, a structure of disavowal, which has to be thoroughly contradicted on all the levels, starting on the level of primitive processor instructions which, according to the simplest laws of thermodynamics, can’t perform any destructive operation – can’t forget any value of any variable – without wasting some energy, emanating some heat. This kind of thought is as material as it can be.

Right here, right now, I can show you how the materiality of computer affects our everyday life in a very noticeable, annoying fashion. Let us recall that to study the whole population of computers a special concept was invented, ‘the Turing machine’. It was a strange abstraction, seeking to provide an ideal type for those machines, a link between their real bodies and the computable functions which are performed by them. It is used in science, yes, but it is also used too much in the arguments between the adolescent programmers, if you ever dared to talk to them – “C and Lisp are the same thing because of the Turing machine”... But let’s leave them be. Where’s the Turing machine’s fault?

Turing machine is imagined to have an infinite time and an infinite memory space. That’s what we can sometimes believe about our computers. When our computers run out of time – that is, we subjectively feel that they are slow – we’re annoyed and happy to fix it. The existence of the computer as a time-consuming device is obvious and we’re perfectly equipped to notice it; every second it’s slowing down we’re feeling it, I think, already at the level of our bodies; yet there’s no realistic limit to how long a computer can run. What is harder to notice, yet much more objective, is the limit of its memory: the computer runs just happily, using as much memory as it can, until there’s no more memory at all. Then strange things begin to happen.

What does exactly happen when the computer is out of memory? Of course, it can just kill the hungry program: it’s not part of the algorithm’s mathematical abstraction, but at least predictable. Usually, however, stranger things happen. One of the ways the computer pretends to have more memory than it actually does is by “swapping”: using the HDD instead of the RAM to store whatever is to be stored in memory. HDD is 10k times slower than RAM: when it’s used for memory too much, nothing crashes, but everything is suddenly very slow. We hear strange noises. The computer starts misbehaving. Random things crash because of the timing issues brought by the lack of speed.

Now we can allow ourselves to see this “lack of memory” in the aristotelian-lacanian light, as something that is material by being actively opposed to the (mathematical) form, not-reducible to it (if only to escape the attempt to inscribe the whole OS, other programs and the hardware into one big ad hoc mathematical structure making any mathematical study of the algorithms pretty much useless). I say “lacanian”, faithfully to Lacan (his Real was Aristotle’s matter), because this is indeed the very point where the subjectivity of computer in the lacanian sense is obvious: it lacks memory (desire) – it acts out (hysteria). If we consider how hackers use a similar problem, the buffer overflow, to do whatever they want to the computer, the analogy becomes rich enough.

The materiality of the neural network. In 1892, one W. E. Johnson described “symbolic calculus” as “an instrument for economizing the exertion of intelligence” (btw, Johnson is described by Wikipedia as “a famous procrastinator”). Far from enabling new types of intelligence by itself, the thing was to save on the wasted expenditure of the old ones. With this I want to introduce another dimension of the materiality of the computer: the one which I’ll describe from a paranoid-marxist perspective, following the Adorno’s belief in the truth of the exaggerations.

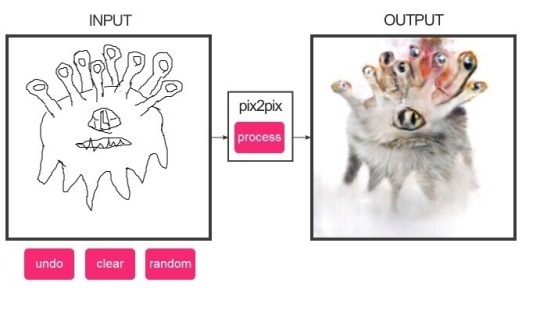

Neural network is an amazing shiny new thing, it economizes our exertion of intelligence all right, yet the weirdest part of it all is that we kinda have no idea how it works. We can describe the output (in our terms which we impose on it), and we can describe the inner structure (it’s all matrix multiplication), but there’s no translation between the output and the inner structure except for the one that is by running the neural network themselves. The neural network’s thinking, in general, lacks the conceptual content we’re so much used to, it doesn’t exactly distinguish the parts of bodies and stuff like that. It operates on a belated, not-yet-conceptual level. We can actually through pain identify some general things that it actually notices on the images and stuff like that, but only partially and constantly recognising that it’s we who’s pulling the vague ideas of the NN to this conceptual level.

To illustrate how the NN works there’s no better example than the notorious network which draws cats upon sketches of cats: http://affinelayer.com/pixsrv/index.html . Try it out, you can do it online. Now, what are the concepts with which the neural network thinks about cats? It’s… well, it knows an eye, but that’s more-or-less it. Everything else is more like a texture of a cat, in a very weird sense of a texture, the one available to us after we discovered the 3D rendering.

So there’s knowledge of things in the NN, yet it’s either not on the human level, or it’s somehow hidden. To explain this, Schopenhauer comes to mind: “an entirely pure and objective picture of things is not reached in the normal mind, because its power of perception at once becomes tired and inactive, as soon as this is not spurred on and set in motion by the will. For it has not enough energy to apprehend the world purely objectively from its own elasticity and without a purpose”. That is to say: NN understands cats exactly as much as it needs to (with the need imposed by its operators, most of the time the Capital), and no more.

Now the paranoid-marxist intervention: what is this lack of knowledge? Who has it? Is it not the proletariat? If we have a training set of thousands of pictures, on which a neural network is trained to recognize dozes of features, those features had to be tagged beforehand by some pure workers (most likely from India, am i right?), who themselves were likely constructed through a cheap-labor marketplace such as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (the name familiar from Walter Benjamin), pretending to be machines to create a neural network which pretends to do the human work. Can’t we say, exaggerating, that the neural network is a labyrinth of numbers in which anyone looking for the human [labor] is to lose his track?

1 note

·

View note

Text

BNHA Chapter 165: Thoughts and Spoilers

This chapter is lacking on action, so bombastic commentary won’t be present, sorry, but this chapter is interesting to think about, and I did do quite a bit of thinking. Anyway, getting into it (this chapter is a gold mine for background character faces, so I recommend going through it once just to see them).

This test is exactly like what we thought it would be, a test of personality. The teacher fears for her students, because they are going through the years that form who they will be, and right now they are turds. The high school students are here to set an example and to help settle the kids and make them more understanding, though the people suppose to be setting the example are not exactly.... ummm... role models? That is probably the best term, and we’ll get more into that later.

Bakugou immediately devises a plan, and I love seeing this, it really solidifies his character for me. In the past he has been described as a ball of instincts, reflexes and battle knowledge, and his standing in class also proves his intelligence. Due to his personality however, I came to the conclusion that he thinks like this: “What? Of course I got the answer right. Show my work? Well isn’t it obvious?” This kind of intelligence seems to sprout straight from the mind, but Bakugou’s plan showed that his thoughts are grounded in logic. He immediately realizes that they lost the initiative, and that there is a “boss” lurking within the crowd somewhere. This knowledge was probably gained from first hand experience of being the “boss,” but the fact that he understands and can verbalize this dynamic impressed me greatly. Knowing and verbalizing are two very different skills, and I assumed that Bakugou could not verbalize his intentions quite like that before. It is possible that this is proof of growth, that he is actually talking with comrades and setting down some base work (even though his ultimate plan is to humiliate the boss... he still has a ways to go). Though I personally believe that the boss is, pretty obviously, that weird side-part kid who has already dissed Bakugou. Bakugou is put on the side after the supposed boss says that violence won’t work and accurately guesses about his upbringing, stealing the advantage once again.

Inasa then tries, and he makes considerable progress compared to Bakugou. He starts with something safe, heroes, and works from there. His personality is much better for this type of thing (as the meat grinder guy says in his 100% necessary narration), and starts telling the kids what type of people they should be. This gets shot down too however, since the kid he was talking too pointed out that he wasn’t in any place to talk from either. This made me think some. Inasa took a good approach, no B.S. and just told them what a good person should do and two thoughts hit me. 1.) If Inasa admitted his mistake and continued to push the thought, would he have succeeded? Would humility work in this scenario or would the kids see that as completely destroying his credibility? And 2.) Was lecturing them in the first place a good idea? This could very well be showing that lecturing about something good with good intentions is still lecturing and no one really has any moral high ground, so a fundamentally flawed approach. Inasa apologizes for overstepping his bounds and he tags out (with a fiery flare).

Then we get a handful of panels that show... something. Bakugou wants to settle this with violence (shocker), but Todoroki stops him, and says that there is a better way. Bakugou claims this was how he was raised, but he remembers when he accidentally eavesdropped on Todoroki confessing to Deku about the abusive upbringing he had and the overwhelming hatred that Todoroki still carries. Bakugou stops, and lets Todoroki do it his way. This is improvement, this is consideration and empathy. Bakugou has impressed me twice this chapter, and his growth and improvement may appear small, but it is certainly there, he is growing and learning.

Endeavor is also growing in the stands slightly. He admits to All Might that he understands the difference between them as heroes, but in his words it shows that he also rejects the part of All Might that made him the Number One Hero, Endeavor rejects the so-called “crowd-pleasing,” because he wants to be the strongest. I have already shared my opinions on why All Might was ranked higher (a general feeling of security), but All Might took the conversation in an unexpected direction (at least it was nothing I predicted, though it makes sense). All Might states what made him want to be the symbol that he was, he spoke about wanting to be hope for the innocent and a warning (”warning,” is not aggressive) for criminals. He spoke about the sacrifices that he made for it, which Endeavor knows about Sir Nighteye, but he says it passively, with no meaning, for such a terrible guy, being respectful of the dead was surprising. All Might also shares some understanding, he knows the situation Endeavor is in and tells him this, “you don’t have to be the same type of symbol.” This struck me. I always wanted Deku to grow into something different than All Might, but I feared him falling into All Might’s legacy, but here is All Might, telling a man who hated him for years to be a different symbol. A different symbol was something I hadn’t imagined for anyone other than Deku, I suppose I imagined a symbol-less place until Deku matured. As much as everyone hates Endeavor, I see genuine potential from him. He is already growing and maturing and seeking advice, he won’t be any symbol of hope, but he certainly could become a symbol of strength. If he mellows out, becomes calm, confident, swift and determined, he could set people at ease, or at least ward off crime for a time. A good analogy would be this: Endeavor is a standing army, scary yes, but it would be comforting to know that it stands with you rather than against you. We might have a couple symbols before Deku takes the stage, and I am okay with that, plus, the fan art could be really cool. Blue background All Might, “Peace,” Red background Endeavor, “Strength,” some other primary or secondary color background hero, “some abstract idea.” It could be cool.

Unfortunately, Endeavor does not comprehend the word “chill,” and whips around when Todoroki steps up to bat and screams his support once more. Todoroki understands the generals of what you have to do to get people to trust you, but he can’t seem to execute it. He basically gives a character description of himself and the kids lose interest, or they are amazed by his total lack of social skills. Todoroki is forced to retire and try again later.

The next idea is brought up by Camie, and Bakugou agrees. Show off our quirks and show them who we are. This is a good take, “lead by example,” but those leading kinda don’t know restraint... so this could get rough. But once again, the kids steal the initiative. They activate their quirks as well, but only after a brief discussion that explains where all this confidence comes from. The live in a world where they hear all the criticisms of heroes all the time, and with the fall of the symbol of peace, the raise of the League of Villains, and several other social factors, to them, this generation of heroes can not be trusted or that they are unreliable, thus, they believe that they can be better. This is good in moderation, but it seems that the presence of this “boss” has jacked up their pride one hundred-fold. The boss probably took advantage of this social criticism of heroes to wreck havoc, meaning, the boss is a turd. The display of quirks by the high schoolers is the best way to show that they are competent and that their unease and pride are... unfounded? That seems a little harsh, maybe just the realization that they are safer than they believed will settle their spirits.

Well, that’s all. I said this my last post, but I am glad that this arc is right after the raid arc. It is a good change of pace and it looks more closely at the specifics and technicalities of what it means to be a hero instead of just punching villains. The only other comment that I want to make is this: I am curious as to what Camie’s quirk is, we haven’t seen her use it yet since last time we saw her do anything was actually Toga. So I am curious as to what it is, how well she can control it, and what her role will be in appeasing the children. Thank you for reading this and I hope you have a great day, and happy new year.

#bnha#bnha spoilers#bnha thoughts#katsuki bakugou#yoarashi inasa#todoroki shouto#All Might#endeavor#deku midoriya

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

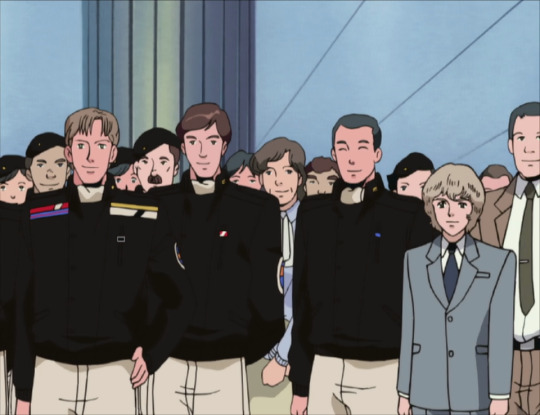

Episode 7: Iserlohn Taken!

May 14th, 796/487. Infiltrating Iserlohn fortress in the guise of a damaged Imperial ship, the Rosen Ritter swiftly overpower the control room. The quick thinking of one Imperial soldier temporarily locks them out of the fortress computer, forcing Yang to stall for time while Schenkopp and co. rush around Iserlohn kicking ass and taking names—names and computer passwords, I guess, since they unlock the system and allow Yang’s ship to dock. The Thor Hammer makes quick work of a large chunk of the Imperial fleet, although Oberstein flits away like the cockroach he is.

Technical Aside: Character Redraws

As I mentioned, when LoGH was released on DVD the episodes were remastered. By and large this involved evening out the colors, fixing the lighting when it was too washed out, sharpening lines, etc., and it’s beautifully done and deserves a lot of credit for making this show such an aesthetic joy to watch.

However. For reasons lost to the sands of time (at least, unknown to us) some scenes were entirely reanimated, primarily in the first and early second seasons. These redraws go beyond the touchups of other episodes—sometimes in ways that have little consequence (changing backgrounds, slightly different positioning of the characters in the scene), but sometimes in ways that significantly alter the emotions conveyed on the characters’ faces. This poses a problem for us, since the whole thesis of this project is that the animators of LoGH intentionally conveyed a ton of important information about emotions, thoughts, and relationships of the characters specifically via the details of the expressions and body language.

As an example of an inconsequential but unfortunate change, they made this random dude’s hair way more boring. Poor guy.

The original here conveys much more character though the body language.