#and the end culminating in the ultimate futility of war

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Also dig Star Wars for how it’ll casually reveal the most batshit insane stories are happening right off-camera during the main plot and in the end none of them amount to anything because we know damn well none of that shit occurred within the main plot. Like how in Episode 1 the Podracers. One of them is a hit man who kills other racers and he’s been hired by this other racer who wants to become famous but is worried about this main champion dude, the antagonist, getting in his way. The antagonist is worried about our protagonist so he pays a dude to sabotage the protagonist but the dude sabotages the wrong guy and that’s why this racer’s vehicle doesn’t work in the movie. The antagonist is anticipating the hit man so one of the other racers happens to be a bodyguard. And also there’s this other guy who’s here to get revenge on the hit man and it’s the only reason he’s racing at all.

All of this setup happens but we the audience know it’s doomed to culminate in only the protagonist and antagonist’s beef and jackshit happens off-camera as nobody really accomplishes anything except the bodyguard I guess. And the guy who wants revenge on the hit man fails in the most unnoticeable way but it kinda doesn’t matter because he walks away realizing he actually likes doing these races for their sake and not just to get close to his revenge target. His name is Kam Nale but he entered under the reversed alias of Elan Mak.

Like for some of these Glup Shittos the day the main plot crashed into their lives and interrupted all of their plans was the greatest day of their lives. For the main characters it was. Well it was decently important but in a completely unrelated way. Did you know some goons at Jabba’s Palace had a whole conspiracy going on but it got botched because one of them got kicked into the Sarlacc Pit by Luke Skywalker because just as we’re reminded there are other meaningful lives going on in the world through these characters, so too are they reminded of this by the main characters. And in the end there’s an absurd beauty in the futility of how our lives are casually superseded by some bigger shit because the world is so huge and uncaring and ourselves insignificant. It’s like if some criminals were organizing the ultimate conspiracy and then it was aborted because Godzilla stepped on their headquarters on his way to beef with Kong (He could’ve just as easily walked around the building but he didn’t care enough to calculate optimal routes).

44 notes

·

View notes

Note

Y'know I was thinking about Brave New World and how it's a Hulk movie with Captain America as the Protagonist, and I thought what if we change the antagonist?

Like, instead of a sequel for the "Incredible Hulk" movie, we make it a sequel to "Captain America and the Winter Soldier"?

We bring back Zola, and make the Big Threath "The Sleepers"?

Y'know the Giant Hydra robots.

I think a secret Hydra threat might have increased the movie's unfavorable comparisons to Winter Soldier. Though that might be unavoidable.

Despite Age of Ultron allegedly featuring the very final defeat of Hydra, Hydra is still around, according to Ant-Man. And also Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. but that series isn't canon right now.

For me, I think the best thing they could have done would have been to just let Ross be the monster that the movie wants him to be. He's already barking racism at Sam and sacrificing Isaiah for PR and detaining Sterns without trial to force him to give him treatments.

Just take out the parts where the movie turns around and goes, "But he's a really good guy. He's a good guy. Honest. He's such a changed man, I swear!" and just let him be vile. Let the Red Hulk be the actual villain of a movie that culminates in a boss battle with the Red Hulk.

You can still have Sam talk him down at the end!

Make the Red Hulk fight into Ross lashing out after he's been publicly exposed for his crimes, similar to how Iron Man handled the Ironmonger fight. Big fantasy superhero moment where Ross is like "I AM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES" but Captain America is here to drag him away on behalf of The People anyway, and then Ross suddenly reveals what he was making Sterns do to him.

The Red Hulk fight should feel like the culmination of Ross's entire journey across the MCU, from Incredible Hulk to Civil War to Black Widow to Avengers: Endgame and now reaching its apex in Brave New World. Like this is what it's all been building towards. It's all finally coming out here.

It should feel climactic, not just for the movie but for the Saga of Thunderbolt Ross. Finally releasing all of the tension that has been built up for two decades around this smug little shitstain of a man. You don't even need to have seen Incredible Hulk to want to see Captain America break Ross's fucking nose. He's kind of a big deal.

Making him the well-meaning deuteragonist was a wild choice. And seeing how the box office is performing for the film, I can't help but think that this choice ruined any hope the film had of finding its audience.

But I can't help but feel there's a version of this movie that could exist, where Sam gets to have his moment of triumph over a truly heinous Ross, an action-packed boss fight with the Red Hulk, and still ultimately give a big speech that persuades Ross to cut his losses, recognize the futility of his actions, and surrender for his daughter's sake.

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Saw the tags on the Toshinori post and do you have more to share?? Any insights? If so I’d welcome hearing them 😭 He really is so self-sacrificial and it hurts but it’s truly at the core of who he is

This has been sitting in my inbox for almost a week because I needed to make a futile effort at organizing my thoughts into something coherent--but this is as organized as they're going to get for now! Thank you so so much for the ask though bc I do love to yell about MHA <3

(Obligatory reminder that I'm watching this show in such a confusing order so if what I'm about to rant about has been addressed before and I'm harping on it unnecessarily I Am Sorry.)

(For anyone curious, this is the post btw)

SO. It feels relevant to mention that my sister and I were talking about All Might in the first place because we were talking about MHA Moments That Haunt Us. For me, it's the 'I am not here' sign hanging around the neck of the All Might statue in Kamino Ward after the Paranormal Liberation War. It literally lives in my brain rent-free 24/7 365 days a year, especially with the AM vs AFO fight being relatively fresh in my mind. The reversal of All Might's catchphrase and all it represents hurts, but to display it at the site of his 'last stand' in Kamino? That's brutal.

All Might vs All For One and how that rematch plays out is so so important to the story for so many reasons, but one of them is that the fight itself is a sacrifice. Toshinori gives everything he has, short of his life, to defeat All For One. He gives up his physical strength, his public image as the unbeatable Symbol of Peace, and, effectively his Quirk ("Goodbye, All For One. Goodbye, One For All" haunts my every waking moment, still!)

This battle is also the culmination of years of All Might's life and heroic philosophy (because Toshinori has been both practicing AND preaching self-sacrifice in the name of the greater good since we met him. It's what he thinks a hero does). Kamino is the sacrifice to end all sacrifices, if you will. Yes, he does get to walk away from the fight with AFO, but he walks away irrevocably different, almost unrecognizable. He's forced to totally change his focus and his mindset and his life. Everything he has given up is made literally visible in the deterioration of his body.

But most most importantly, All Might's sacrifice at Kamino was... all for nothing. Even if AM defeated him in that moment, All For One is free less than a year later. The world is in shambles. People are afraid, and their faith in heroes is crumbling. Heroes are afraid, and this time, they have no idealized symbol to rally behind. When Dostoevsky wrote "Your worst sin is that you have destroyed and betrayed yourself for nothing," he was talking about All Might btw.

Toshinori gave this fight (and his career, and being All Might) everything he had, and it still wasn't enough. He sacrificed so much of himself, and so much of how he perceived himself and his purpose, and he didn't even save the world. He just bought them time--and not much of it. I think that's why he's so desperate to keep fighting, no matter the cost, no matter what condition he's in--even 'quite literally half-dead.' He can't let Kamino be the Symbol of Peace's final stand, because Kamino was ultimately for nothing. Instead of saving the world, it has been reframed through the sign on the statue as All Might abandoning the world. And ever since then, he's been scrambling to prove that he is still here.

(There's also probably something here about Sir Nighteye telling him that he was going to die. Since Nighteye used his Quirk on him, Toshinori has been anticipating sacrificing his life for good. Knowing that his entire hero career is effectively a fight to the death has probably maximized his self-sacrificial tendencies.)

#ask#yagi toshinori#bnha all might#mha all might#love of my LIFE#i had more bullet points to include about all might's philosophy of self-sacrifice as both a hero and a teacher#but then i was writing random notes about all might as a product of hero society as opposed to a pillar of it and i felt like that one vide#of the old man going '90% of the time i have no idea what the hell i'm talking about'#it wasn't strictly relevant to this ask but maybe one day it will be it's own post bc toshinori messes me up when i think about him#for longer than 0.5 seconds#this is so word vomit i'm so sorry#liza blather#AND ANOTHER THING. a lot of the pros are self-sacrificial to an extreme (i made a web weave abt it) but all might is one of the few#who actually makes it his PHILOSOPHY. like he passes on the idea of setting yourself on fire to keep others warm as a Good Plan#which is NOT a criticism of him OR his fault it's what he LEARNED to do just like#i can't really blame the ua faculty for the sports fest as messed up as it was bc like. half of them are probably ua alumni. they#probably had their own sports festival. this is just like. not registering as abnormal to them.#okay now i will stop#one thing about me is if i'm not talking about kamino i'm talking about the sports festival#and on the off chance i'm not talking about either i'm talking about the joint training arc

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

I had this draft for the 8 shows to get to know me meme that no one tagged me in, but then @batri-jopa tagged me for this other meme, so I'm doiing them as a mash-up.

10 comfort shows -

- that tell you more than you wanted to know about me. reasons below the cut, but the tl;dr is:

The Terror

Garrow's Law

Ripper Street

The X Files

Utopia

Interview with the Vampire

(BBC) Ghosts

Futurama

Avatar: the Last Airbender

Detectorists

Honourable mentions: Andor (will probably make the list once season 2 is out, but my trust of Disney Star Wars is *so* thin, I can't commit until then, no matter how excellent season 1 is); The Great (it's so good. The script is still one of the most astonishing works of art I have ever encountered. But comfort TV? hell no.); see also, Bojack Horseman (objectively great. Not comfort TV); Grease Monkeys (I've got to get hold of season 2, but I'm really fond of its coarseness, wish-fulfilment and sureallism).

Tagging 10 people if they wanna join in, but others feel free to say I tagged you! @stripedroseandsketchpads, @notfromcold, @notabuddhist, @donnaimmaculata, @erinaceina, @boogerwookiesugarcookie, @elwenyere, @kheldara, @bellaroles, @jimtheviking

List 10 comfort shows and then tag 10 people

The Terror: Like Ripper Street below, I feel this show deep in my bones and think I must be actually insane when I try to explain to people what I like about it (watching it literally made my husband's depression worse so I'm not allowed to talk about it. Jk. Sort of. About the last bit anyway). The sheer ridiculousness of that era of exploration has been a firm fave for years and I love how the show weaves horror and hubris together, how it's not a straightforward 'natives get vengeance on colonisers' story, but the colonisers ruin it for everyone, poison life for Silna, too (all without any threat of sexual violence towards her CAN YOU BELIEVE IT). I love all the attempts to impose 'civilisation' on the life the men try to live as they come to realise how doomed they are, how key the trappings of their life become - objects as tethers and talismans. I love how utterly futile it all is. How much they all care, and the audience cares despite that. Self-destruction and salvation all jumbled up together. Two full crews go into the ice and die. The end. They do everything they can not to die and it happens anyway, it's the ultimate 'the love was there and it didn't change anything'. And no one learns anything. Perfect TV.

Garrow's Law: Sometimes I do want my historical drama to be wish fulfillment actually, and this is the actual og fave. No, most of the cases weren't actually Garrow's, yes, it's a fluffy liberal take on things that played out in a more complex way, but the cast is so good, and Garrow is such a likeable guy, but then you see his flaws emerge in such a gentle way through the four series, and it really does case-of-the-week with characterisation so well, and it's got that amazing British TV character actor cast where there's always someone in the background you know, and the building romance between Garrow and Sarah, and the real repercussions of it for her are handled so sensitively, augh the culmination of the series with their own personal legal cases is so good.

Ripper Street: in my head this show was so much more than the sum of its parts. Season 1 was on the surface a fun BBC historical romp. Season 2 I had to watch through gritted teeth because Susan's situation quicked me out too much, among other reasons. Season 3 leaned into the more sinister side of the protagonist and came through as something weirder and darker, a vein which ran through Seasons 4 and 5, which I thoroughly enjoyed. I live for my alternative reading of the migration stories and nightmarish flipsides of people that we get running through the background of seasons [3/]4/5, but uh. the show's tumblr fandom is not a place for me. Reid is actually monstrous, and I like him despite/because of that. Oh man, I have so many feelings about this show, and I'd love to do a rewatch and blog about all my crazy theories but I'd probably have to go into witness protection afterwards. But rest assured, it isn't a show about the Ripper, and it's all the better for that. It does class and trauma so well, it also captures all the optimistic curiosity and the utter hypocrisy and hubris of the Victorian era so well.

The X Files: I mean, it's a formative influence, innit. Seasons 1 and 3 are the best, a lot of the 'classic' favourites are episodes I actually really disliked, even though the early seasons are the best a lot of my favourite episodes are from later...the beauty of TXF is that there's so much of it you can hold contradictory opinions about what makes it good, though, and my theory is that it's at its best when it's early and still being allowed to take its course, where even the mytharc hasn't tied itself in knots yet so every episode is of a higher standard, and then later, when the actors have wrested control of their characters from CC enough to play them like they want, but the good episodes are really just MotW ones because the mytharc has vanished up it's own fundament and I've lost track of whose turn it is to have a near-death season arc. Not technically the TV series, but still, Fight the Future is just so much of its time, watching it is like having a warm bubble bath in childhood nostalgia. Even the later series have things to recommend them - I always enjoy Doggett much more than I'm expecting to, and it's about bloody time Scully got a decent female friend in the form of Reyes...I haven't watched seasons 10 onwards though, I don't feel I'm missing much. Five fave episodes: 1.13 Beyond the Sea, 3.4 Clyde Bruckman's Final Repose, 5.4 Detour, 7.17 all things, 6.19 The Unnatural.

Utopia: Tragically incomplete at 2 seasons, but what a pair of seasons they are. Brutal and uncompromising, horrible and compelling, but also frequently hilarious and full of the warmest, most fascinating characters who are all on a journey to Getting Much Worse. It's not something I've been able to watch since the pandemic *weak laugh* but I know when I do go back to it it will remain painfully prescient and uncomfortable. The longing for a 'balancing' and a righting of a historic wrong that drives it, and the desperate failures between people who are really just searching for love and don't know how to give/receive it...ugh so good.

Interview with the Vampire: Just rewatched season 1 and I'm just. No notes, five stars. The way Louis think he's a narrator in control, the way Daniel knows such a thing isn't possible, the way Louis does let himself get drawn on things, the way Armand sees the danger in this but it's not in his control any longer. Memory is a monster. The Odyssey of recollection. Fucking won my heart with those lines alone.

(BBC) Ghosts: Ok, I will say that I think the last season was actually a bit weak. They were in a hurry to finish, and they got away with wringing the feels from the important bits (The Captain's death was perfect and I will say this over and over again), but it felt like it was in a rush to come up with scenarios that would force admissions like The Captain's, whereas the show is at its best meandering around in a buffonish way that suddenly results in a Big Oof moment. Robin's arc in season 4 was a great example of this, as was Mary's. But basically it's still simply perfect comfort TV: silly but not malicious, unfair but kind to its characters. I'm going to miss them all so much, but I'm also going to rewatch so much.

Futurama: bit basic maybe, but I have watched it so often and I can watch any episode (ok, except for Jurassic Bark) again and again and again. I don't think I've binged any TV show so often with so many different people. Not sure how I feel about the immanent revival, but this has always been my favourite Matt Groening product, so fingers crossed.

Avatar: the Last Airbender: without getting into like...fandom discourse, man, this is a really perfect show. No need to say 'ooh it gets good after--!', it's just good from the beginning. A really well fleshed-out world, great characters who grow through the series, enough self awareness that the 'clip-show' episode Ember Island Players actually builds on the characterisation and addresses ambiguities in its own plots. A show that sticks to its principles and doesn't fudge the ending and also consistently looks gorgeous.

Detectorists: I had to put it on because no other show has literally made me fall off my chair laughing. Are the main characters useless? Yes. Is it often perplexing that the women in their lives spend any time with them? Yes. But that's forgiveable, because it's ultimately so kind to its beleagured characters and things work out despite their stupid decisions. Also it just captures rural English eccentricity so well. They're all such freaks (affectionate).

#comfort tv#look of course about half of these are bbc shows#of course that's comfort tv!#*ok not bbc but uk terrestrial tv anyway#memes#tv#ughhh i wanna rewatch so many of these but not until the house move...

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eschatological Pessimism: A Gloomy Vision of the End

Eschatological pessimism is a philosophical and theological perspective that anticipates a catastrophic or tragic end to human history, often accompanied by suffering, divine judgment, or irreversible decay. Unlike optimistic eschatologies—such as Christian millenarianism or secular progressivism, which envision a redemptive or utopian culmination—eschatological pessimism sees the future as marked by inevitable decline, destruction, or meaninglessness. This worldview appears in religious traditions, existential philosophy, and contemporary environmental thought, reflecting deep anxieties about human fate.

Religious and Mythological Roots

Many ancient mythologies and religious traditions contain elements of eschatological pessimism. In Norse mythology, Ragnarök prophesies a great battle leading to the death of gods and the submersion of the world in water, with only a few survivors to restart a fragile existence. Similarly, in Christianity, while some interpretations emphasize Christ’s triumphant return and the establishment of a New Jerusalem, others focus on the apocalyptic horrors of the Tribulation, the Antichrist, and eternal damnation for the wicked. In Buddhism, the concept of the Dharma Ending Age (Mappō) suggests a gradual decline in spiritual wisdom, leading to moral corruption and societal collapse before a distant future renewal. These narratives reflect a belief that human history is not progressing toward perfection but rather spiraling toward dissolution.

Philosophical and Existential Dimensions

Modern secular thought has also embraced eschatological pessimism, particularly in existentialist and nihilist philosophies. Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of eternal recurrence—the idea that all events repeat infinitely—can be seen as a form of cosmic pessimism, stripping history of linear progress. Arthur Schopenhauer’s philosophy, which views existence as fundamentally driven by suffering and blind will, further reinforces a bleak outlook on humanity’s ultimate destiny. In the 20th century, thinkers like Oswald Spengler (The Decline of the West) argued that civilizations follow organic cycles of growth and decay, with Western culture inevitably entering its twilight phase. Similarly, existentialist writers like Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre grappled with the absurdity of existence, suggesting that human striving occurs in a universe indifferent to meaning or redemption.

Contemporary Manifestations

Today, eschatological pessimism is evident in anxieties about climate change, nuclear war, and technological collapse. Environmental doomerism—the belief that ecological catastrophe is now unavoidable—echoes earlier apocalyptic fears but grounds them in scientific projections rather than divine prophecy. Films like The Road (2009) and literature such as Cormac McCarthy’s works depict a world stripped of hope, where survival is the only remaining imperative. Transhumanism and artificial intelligence also provoke pessimistic eschatologies, with fears that humanity may be rendered obsolete by its own creations. Nick Bostrom’s “simulation argument” and concerns about AI alignment reflect modern existential dread, where the end of humanity could come not through divine wrath but through technological missteps.

Conclusion

Eschatological pessimism serves as a counterpoint to narratives of progress and redemption, forcing humanity to confront the possibility of an unheroic or tragic end. Whether rooted in religion, philosophy, or contemporary crises, this perspective underscores the fragility of human existence and the potential for ultimate futility. While it may seem bleak, it also invites deeper reflection on how societies respond to impending doom—whether through resignation, defiance, or a search for meaning in the face of oblivion. In a world where optimism often feels naïve, eschatological pessimism remains a powerful lens through which to examine humanity’s deepest fears about the future.

0 notes

Text

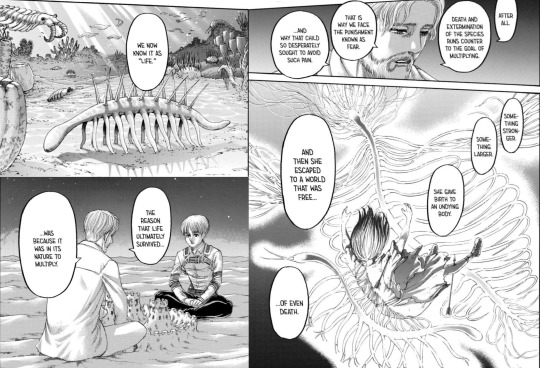

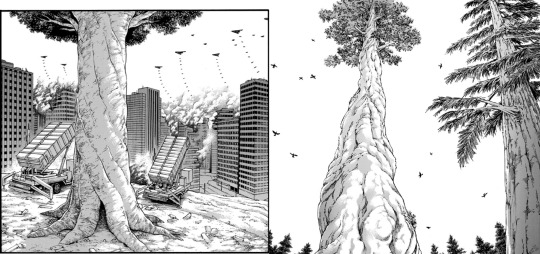

SNK 139.5: Towards the Final Pages with no Final Answers

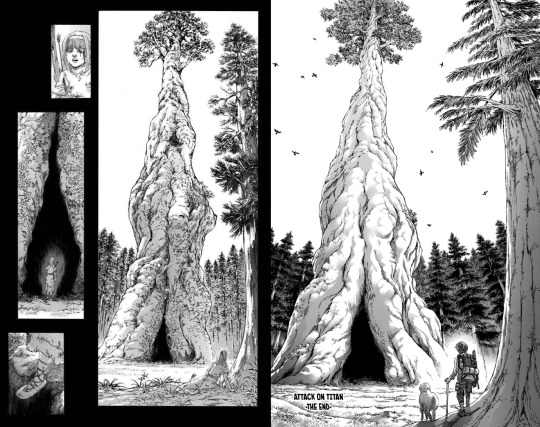

The final pages of the updated ending are bold, but I think ultimately more evocative than the original preliminary ending.

Even after the intensely polarized reader reception that took issue with the lack of storytelling precision and clarity when it was most needed, SNK chose to end with a decisively ambiguous symbol. In literature, a symbol is something that clearly means something -- but with the most "literary" symbols, their meaning cannot be absolutely defined; any attempted answer as to what a symbol represents has no finality or certainty, and interpretation will remain ever open to debate. A symbol both invites and resists interpretation.

Naturally, the immediate response to the symbolic tree on the final page is to try answering the invitation to the question, "What does it mean?"

One prominent answer I've seen is that it symbolizes the continuation of the cycle of war and violence either because a) of the symbolic parallel to Ymir or b) on a more literal level, that it implies the actual potential revival of new era of Titans. A reasonable interpretation either way, but also, I think, an incomplete one.

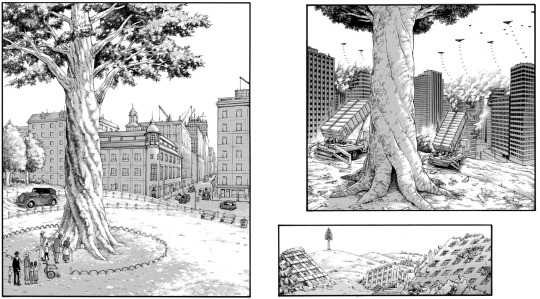

The first reason for this is that "the endless cycle of war" was already clearly and powerful represented in the preceding panels:

The cycle of war was already continuing in the decades or centuries before the child arrived at the tree. A culminating image symbolizing the persistence or resurgence of an era of war as the final panel would thus arguably be redundant and unnecessary.

Furthermore, the chapter is entitled "Toward the Tree on That Hill." If the tree were simply a symbol of war, by implication the chapter could equally be called 'toward the endless cycle of war'. But such a relentlessly bleak and tonally flat ending sentiment would be firmly incongruous with the story's recurrent conviction in the equal cruelty and beauty of the world -- a conviction that I believe it has been faithful to all the way to its end.

The Long Defeat

But while on this topic of war, let's linger a moment on the "cruelty" side and the consequence of this wordless construction and subsequent destruction of a city -- the most bold and possibly controversial additional panels that are also my personal favourite additions.

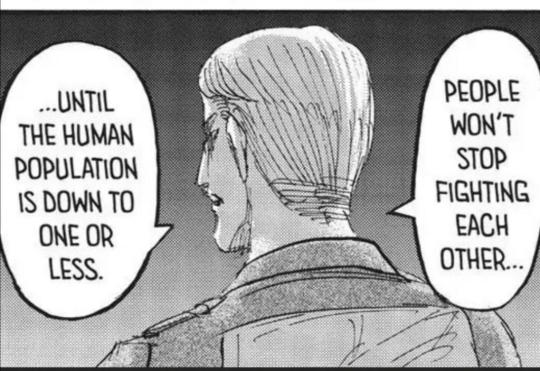

One objection that has emerged against this brief sequence of Paradis' apparent destruction is that it renders the entire story to be "pointless". Eren's 80% Rumbling, Armin's diplomatic peace talks between the remnants of the Allied Nations and Paradis, and before that, the proposal of the 50-year plan and Zeke's euthanasia plan... everything, to the very beginning to the Survey Corps' dreams of some kind of freedom; was it all for nothing? All that striving, that hope, that final promise bestowed upon Armin: was it all a pointless story? Even more radically, is the story suggesting that Eren might as well have continued the Rumbling to 100% of the earth? Was Zeke's euthanasia plan the cruel but correct choice all along? What was the point of rejecting the 50-year plan if that had a greater chance of success at preventing this outcome?

I think Isayama suddenly pulling back to such a long-term view of history to the scale of decades or even centuries into the future calls for a reorientation in attitude towards exactly what kind of story we have been reading. Yes, if the metric is Paradis' survival, maybe it was indeed all "pointless". But that's also to say that, on the broadest scale, SNK is a story about futility, that it is a deliberate representation of the struggle to make one's actions historically meaningful.

In the long view of history, all the events, from Grisha running beyond the wall to see the airships and the first breaking of Wall Maria to Erwin's sacrifices, Paradis' discovery of the outside world, and finally to the Battle of Heaven and Earth, it would all merely be a handful of chapters in the history textbooks of the future. A future in which war and geopolitical conflict will continue even without Titans. That does not mean that all paths to the future are equal -- the 50-year plan would not have put an end to Titans, and Zeke's euthanasia plan distorts utilitarian ethics into just another form of oppression; there are better and worse decisions that lead to more and less degrees of suffering, but no decision can ever be the final one.

The additional panels remind us that in history, there never exists a singular "Final Solution". The reason there are readers who vehemently support Eren to have flattened 100% of the world, and the reason the Paradisians supported the oppressive, authoritarian, proto-fascist Jaegar Faction under Floch and even after the Rumbling, is that because they want to believe that a Final Solution to end conflict exists and will work. They resist the fundamental uncertainty and complexity of the situation, instead preferring a singular, unified, and coherent Answer to Paradis' struggle to survive. I'm reminded of the scholar Erich Auerbach's theorization of why fascism appealed to many people during periods of political and social crisis, change, and uncertainty. Writing in exile after fleeing Nazi Germany, he observed that:

"The temptation to entrust oneself to a sect which solved all problems with a single formula, whose power of suggestion imposed solidarity, and which ostracized everything which would not fit in and submit - this temptation was so great that, with many people, fascism hardly had to employ force when the time came for it to spread through the countries of old European culture." (from Mimesis p. 550)

This acutely describes the Jaegar Faction's rise to power and continued dominance in Paradis. But their promise of unity, of a single formula to wipe out the rest of the world either literally through the Rumbling, or to dominate them with military force, is a false one. Even if Eren had Rumbled 100% of the world instead of 80%, history would still go on. The external threat of the world may have been eliminated, but internal conflict and violence would still continue onward throughout the generations born on top of the blood of the rest of the world. Needless to say, out of all the options, Eren's 80% Rumbling is the very epitome of perpetuating the cycle of violence as it creates tens of thousands of war orphans like Eren once was, and it would justify employing violence for one's own self-interest to an extreme degree. For the generations to come that would valourize Eren as a hero, it would set a dangerous precedent for what degree of destruction is acceptable for self-defence -- nothing short of the attempt to flatten the entire world. It is no surprise that Paradis would meet a violent end when its founding one-party rule of the Jaegar Faction has their roots in such unapologetically bloody foundations.

Neither the 80% Rumbling nor the militaristic, ultra-nationalistic Jaegar faction that come to govern Paradis are glamourized as the "correct" solution to ensuring Paradis' future. (This can also put to rest any accusations of SNK's ending as "fascist" or "imperialist" propaganda, since the island's modern nation that they founded ends in war. All nations must fall eventually, but not all do in such blatant destruction). Importantly, neither is Armin's diplomatic mission naively idealized as that which permanently achieves world peace. No singular or unifying formula can work because reality is complicated. Entrusting oneself to seemingly simple Answers is simply insufficient, even if they are ideals of peaceful negotiation; that method may work given the right conditions, but the world will always eventually complicate its feasibility.

After all in the real world, there's the absurd irony that some in the West had called the First World War "The War to End all Wars". These days, WWI is merely one long chapter in our textbooks just a few pages away from the even longer chapter of the Second World War that is followed by all the rest of the conflicts that have followed since then even with the establishment of diplomatic organizations like the United Nations. In this sense, showing Paradis' eventual downfall is perhaps the only way to end such a series that is so concerned with history, from King Fritz's tribal expansion into empire, the rise and fall of Marleyan ascendency, and finally of the survival and apparent shattering of Paradis.

From its beginning to its end, SNK has poignantly evoked J.R.R. Tolkien's conception of history as The Long Defeat. In one character's words, "together through ages of the world we have fought the long defeat". That is to say, "no victory is complete, that evil rises again, and that even victory brings loss".

No heroes, only humans

Eren's desperate, fatalistic resignation to committing the Rumbling, along with the characters' rejection of all the rest of the earlier plans to ensure Paradis a future, are merely the actions of human beings to that began with the need to find not even necessarily a Final Answer, but at least an acceptable and feasible one for the time being. But the characterization of Eren's confusion, childishness, and regret in the final chapter is startlingly real in how it demonstrates how, all along, we have been dealing not with grand heroes, but simply people who have no answers at all. SNK has always been about failures - and often ironic failures; it has always been a story about painful and frequently futile struggle.

People make mistakes, they can be short-sighted, selfish, biased, immature, petty, and irrational, and I think the ending follows through with depicting the consequences of that.

Erwin's self-sacrifice before being able to reach the basement (and his regression to a childhood state in the moments before his death), Kenny's futile chasing after that universal compassion he had seen in Uri, Shadis never being acknowledged by history despite his final heroic action, and so on -- these stories of ironic, futile failures are still meaningful in their mere striving. Eren's ending and Paradis' demise despite Armin's endeavour to ensure them a peaceful future are entirely consistent with this.

SNK certainly follows the shounen trope in which young individuals are bestowed great power and correspondingly great responsibility, and must then reconcile the burden of possessing that greatness on which the fate of the world depends. Yet it is equally defined by its representation of the state that us normal human beings confront everyday: the struggle against the apparent powerlessness to enact any meaningful or lasting change at all. Simultaneously, this helpless state does not exempt us from the responsibility to act in whatever small capacity we are able to resist oppression, ideological extremism, and the perpetuation of violence.

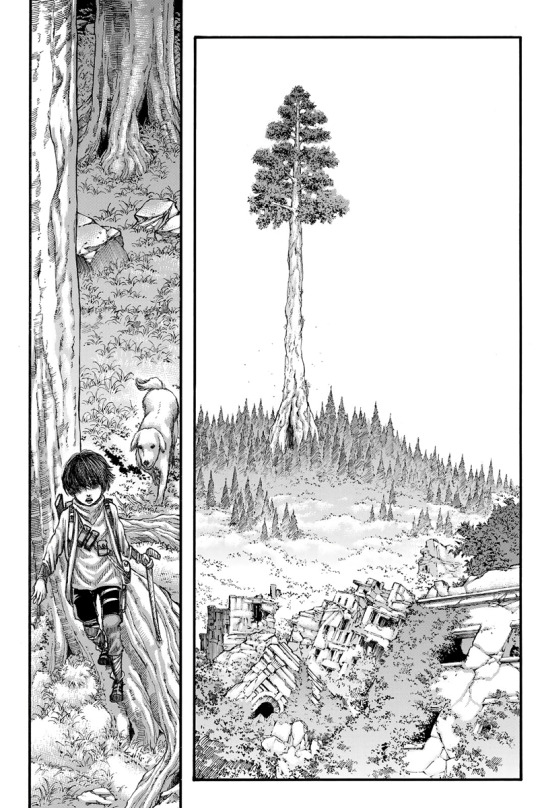

Towards That Symbol

That was a rather long but vital digression about the additional "construction and destruction" pages. To return to the issue of the symbolism in the final panel, here I will turn from seemingly affirming the tree as symbolizing the cycle of violence, towards what I think is the greater complexity of what the tree might "actually" symbolize.

As I've said above, I don't believe that the final chapter title is synonymous with 'toward the endless cycle of war'. In tone, theme, and characterization, SNK has always been defined by the tension between cruelty and beauty, the will to violence and the underlying desire for peace, and the rest of the contradictory impulses that all simultaneously coexist. The end of SNK as a whole commits to a similar lack of closure, ambiguity, and interpretive openness.

So far I have rambled on about only a view of the perpetual "cruelty" of history. Where, then, is the "beauty"?

In short, the "tree = cycle of violence" interpretation is obviously based on how that this tree recalls the original tree in which the spine creature, as the source of the power of the Titans, resided. But it's worth first considering, what exactly is this creature? We seem to get our answer in the chapter that most precisely crystallizes the dual "cruelty and beauty" of the world:

The spine creature might be said to be life itself. Or more specifically, the will of life to perpetuate itself, for no reason at all but for the fleeting moments in which we feel distinctly glad to have existed in the world.

The creature at the source of the Titans, and in extension the Titans themselves, is neither inherently a positive or negative, "good" or "evil", creative or destructive force. It's both and all of those at once. As with any power, the Titans were merely a tool that was put to use to oppressive ends.

So as I now suggest that the tree at the end is symbolically a "Tree of Life", I don't at all mean "life" in the typically celebratory or optimistic sense: rather, I mean it in the ambiguous, ambivalent, uncertain, and complex sense that has been evoked throughout the above discussion of the inevitable continuation of war.

The title "Toward The Tree on That Hill" is derived from its associations with Eren and Mikasa, but more specifically of course, from Armin's affirmation of existence. However, the tree as a symbol of existential affirmation is undercut with the revelation that, despite Armin's diplomatic mediation between the Allied Nations and Paradis, the island nation never escapes war just as no nation in the history of the earth has ever fully escaped war.

The image of Armin running toward that life-affirming tree by the end becomes twisted and complicated, as the image of the anonymous child approaching the Tree of Life evokes both awe at its beauty and grandeur, and a deep dread at the foreboding of its cyclical return to Ymir's tree that signalled the beginning of a bloody era.

And I think that is precisely it: Life is not some idealized, beautiful vision that we always want to run toward; it is also ironic, complicated, and dreadful. It is ambivalent. Like a literary symbol, the meaning of life cannot be pinned down absolutely. The tree therefore becomes itself a symbol of uncertainty, of an open future that is cyclical both in its beauty and war.

As a final observation, it is surely no coincidence that, the small, black, birdlike silhouettes of the war planes destroying the city from the sky is replaced by the similarly small black silhouettes of birds in the final panel.

If the birds represent freedom from war, the irony is that the immediately surrounding land appears to be one completely empty of people save for the exploring child; it is a freedom attained only without people's presence. Yet at the same time, a child from some existing civilization has reached it; perhaps it is freedom that they have reached, perhaps it is something else that they see in the tree. What is it that they were looking for? What does the tree and its history represent for the child, and what does it mean for their future? Alternatively, does the child-in-the-forest imagery negatively recall the warning that the world is one huge forest of predator and prey that we need to protect children from entering?

Rather than providing answers, this tree embodies all of the potential questions, and all of the potential answers. These possibilities will unfold themselves into an uncertain future beyond the chapters of history that Eren, Armin, Mikasa, Zeke, Erwin, and all the rest of the characters were part of and left their mark on; and whatever future this child will witness or create, it will similarly be one of the struggle against futility, as the journey begins anew with each generation in every new era. Neither - or both - hopeful or despairing, the final image of this tree, just like life itself, contains those innumerable irresolvable tensions as it gestures towards all possibilities, both oppressive and free.

#snk 139#snk ending#snk extra pages#snk meta#snk#snk spoilers#brain dump#this is a pretty personal interpretation so if there are any logical inconsistencies i don't know what to do with them#yes the execution of the final arc/chapter is flawed but it's still very conceptually interesting#i still have my disappointments but overall i've made my peace with it#translating my tangled thoughts into words however imperfectly: i think that's what freedom is all about#snk manga#aot#aot 139#aot ending

238 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hmmm it was hard to just pick these for Ivan BUT 🐺

1, 2, 4, 5, 11, 15? 20, 21, 22, 38, 44

look i'm still going through these slowly lmao.

my little wolf boy, my little pup. we love a childhood friend to war criminal to to friend to lover story.

--

1. Does your character have siblings or family members in their age group? Which one are they closest with?

Unfortunately Ivan does not. Not only is he an only child, but he’s the only child of an only child, and with his father not in the picture, it leaves very little in the way of family at all, let alone anyone in his age bracket. There is/is maybe some more extended family out there, or perhaps even… half siblings or something of that nature (he tries not to put much thought into his father or what he might be up to or if he’s even alive…). So as far as Ivan is concerned, it’s just him.

2. What is/was your character’s relationship with their mother like?

Ivan is a bit of a mama’s boy lmao. A lot of that stems from the fact that like, she’s his only family. He sometimes… questions some of the decisions his mother has made, but ultimately he knows that everything she’s done, she’s done out of love, and that she’s just doing the best she can/knows how. Ivan also knows that HE has done some questionable things, but for the most part it hadn’t mattered as long as he made her proud in the end.

4. Has your character ever witnessed something that fundamentally changed them? If so, does anyone else know?

The thing that I can think of (and the thing I think YOU are thinking of lol) is more like… the final tipping point in fundamentally changing Ivan. A culmination of many things witnessed instead of just one moment. And that’d be Ivan seeing the extensive scarring Sasha has. Bit by bit Ivan was starting to realize that he was uh, on the wrong side of the war (thanks to—short version of the story—some elaborate lying on Bannan’s part that that saw Ivan being healed by/living amongst the people he up until then was fighting against/considered his enemy), but seeing the horrors of what his (now former) side had done written into the skin of someone he’d grown to care for dearly really shook him up, and realizing that HE was actually the one who caused that damage (Sasha CAN’T know) was really the final straw in realizing he needed to… stop being the way he was, do better. He got a little bit sidetracked for a bit with guilt and thinking any sort of ‘redemption’ was futile, but he got there.

5. On an average day, what can be found in your character’s pockets?

Not much, he travels pretty light (see: his pants are too tight for much lmao). Couple of coins, small trinket/token likely from Bannan or Sasha, other little things he’s snitched over the course of the day when no one was looking.

11. In what situation was your character the most afraid they’ve ever been?

Near dying probably takes the cake for that one. Ivan spent a lot of time being real cavalier about his life, under the impression that it didn’t much matter to him whether he lived or died. Then came the time that he got absolutely wrecked on a job gone wrong. Ivan learned in an instant that he did in fact want to live, but by that point he didn’t know if he’d be able to get himself to any sort of help in time, and he was terrified. Lucky for him, he knows a good doctor. (A close second is probably having to be the one to free a captured Cullen, but even you don’t know that bit of story yet lol).

15. Is your character preoccupied with money or material possession? Why or why not?

Nah, not really Ivan’s concern. He’s never really had a plethora of wealth or possessions. When he was young and his mom was still working at the palace, they did well enough and Ivan never felt like he was lacking anything, but when fighting broke out and she decided the best/safest bet was not on the side of the Crown/that her allegiances lay elsewhere, she left her position there and whisked Ivan away (without him so much as getting to say goodbye to Bannan). They had to make do on lesser means after that. Most of what Ivan has is more sentimental than anything of actual value. And he gets real flustered over receiving any type of gift.

20. In what ways does your character compare themselves to others? Do they do this for the sake of self-validation, or self-criticism?

Ivan compares himself to just about everyone he meets. His mind starts turning with all the ways he’s not as good as everyone else, even/especially the people he’s closest to. Always thinking about how kind and compassionate Sasha manages to be even though they’ve both been through similar levels of awful shit, and how Cullen is the strongest person he’s met both physically and mentally/emotionally, and the fact that Bannan is like… a literal Prince Charming. Ivan thinks he falls so short in comparison to the three of them and doesn’t have a clue what they see in him.

21. If something tragic or negative happens to your character, do they believe they may have caused or deserved it, or are they quick to blame others?

He’s pretty quick to blame others for his misfortune, or at least he used to be. It was more of like, a ‘blaming a higher power’ type of blaming other people than directing it at an individual. But now that he has reevaluated some life choices and left the ~bad guys~ to instead align himself with the Crown, the main thing he used to blame for all his woes, it’s not so easy to do that. He’s had to start taking more responsibility for the things that happen in his life. Post-switching sides, Ivan definitely went through a phase where he thought he deserved the bad things that have happened to him because of all the bad that he’s done, but having the people around him acknowledge the bad and be willing to move on from it makes it so that blame is not usually kept to only his mopier moments.

22. What does your character like in other people?

Straight-forwardness, because he doesn’t like to beat around the bush and doesn’t like others wasting his time by doing it either. The ability to say sorry, because it’s something he’s working on being better at too. Self-sufficiency, because he’s not one to coddle.

38. Is your character more likely to remove a problem/threat, or remove themselves from a problem/threat?

Remove himself! Ivan prefers to slip in, do what needs to be done, and get out. The less people who are even aware of his presence the better. So if he has the option to remove himself, he will. But if that’s NOT an option, Ivan has a tendency to act akin to a cornered animal. He’s a snarly little thing.

44. How easy or difficult is it for your character to say “I love you?” Can they say it without meaning it?

When he really feels it? It comes out pretty easily, feels only natural to say it. But I think it can take him a while to actually get there, to know what he’s feeling is in fact love. And I doubt he’d say it if he doesn’t mean it, not necessarily because of some heavy meaningful weight he puts on the word, but because he’s not the type of person to just tell people what they wanna hear (not that that’s gotten him into trouble before or anything… lmao).

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

1/ Anxiously waiting for the next asoiaf book to come out, rereading chapters again and again, don't you think there's a possibility that Martin could go for the Medeia reversed storyline, Selyse burning her daughter for helping Stannis (instead of M. killing her kids for revenge), when he already has a mother that goes to extremes for her children (Cat) and one that uses her children for having power herself? (Cersei) It would be a culmination of Selyse's arc; she's for sacrificing children.

2/ Stannis has reservations about it, but she doesn't (well, Edric is not hers--what if the kid was hers?). At the same time, this would tie up some loose ends. It would make winter abate, so the battle happens at WF (not that St. will win it); Sansa would travel; and Val's hostility to Shireen would have a payoff. I hate to think what will happen when Jon comes back to life with Selyse and Val. I take it for granted Martin has not revealed all his secrets in the new book on GoT.

**

Hi anon!

I don’t think it would be nearly as powerful to have Selyse responsible.

For one, that’s not much of an arc for Selyse. She is introduced as a true believer, no holds barred.

God, she said, not gods. The red woman had won her, heart and soul, turning her from the gods of the Seven Kingdoms, both old and new, to worship the one they called the Lord of Light. (ACOK, Prologue)

She is kept unsympathetic throughout, and GRRM uses Jon to suggest that she doesn’t value her daughter, along with not minding if innocent babies die.

It was the answer that Jon Snow had expected. This queen never fails to disappoint. Somehow that did not soften the blow. "Your Grace," he persisted stubbornly, "they are starving at Hardhome by the thousands. Many are women—"

"—and children, yes. Very sad." The queen pulled her daughter closer to her and kissed her cheek. The cheek unmarred by greyscale, Jon did not fail to note. "We are sorry for the little ones, of course, but we must be sensible. We have no food for them, and they are too young to help the king my husband in his wars. Better that they be reborn into the light."

That was just a softer way of saying let them die. (ADWD, Jon XIII)

Having her kill Shireen would be the most logical conclusion. There would be zero twist. It’ s unlike GRRM to go for something so predictable.

Medea-wise, it’s also kind of overtly obscure. Medea reversed is kind of over the top when it comes to literary allusions, if it removes the point of what Medea represents.

The Agamemnon theme exists in the books with Ned and Sansa, but it really comes to the fore with Stannis and Shireen when you consider the deer imagery, the context of war, religious fanaticism and prophecy, and the ultimate futility along with the vengeful wife, which itself also already exists in Cersei and Lysa.

Whoever is responsible, Shireen’s sacrifice will still calm the “seas”, which should then enable Sansa to travel. (Good point!!)

(And I think that there is a different purpose to Val’s rejection of Shireen. She rejects her as “unclean” and claims that the greyscale will resurface and should be countered with “the gift of mercy”. This phrase is particularly associated with the Hound (via Arya and the Elder Brother), who is currently “at rest” on the Quiet Isle. He will most certainly resurface, and although they renamed his aggressive horse Stranger (death) into Driftwood, he retains “his former master’s nature”. There’s a large theme of distrust and redemption at play, and I don’t think it would be served by having Val just straight up aid in murdering Shireen. She is stil a prisoner and has other things to worry about now that Jon was stabbed quite a bit.)

#asoiaf#Greek Mythology#asoiaf speculation#medea#agamemnon#Stannis Baratheon#selyse baratheon#Shireen Baratheon#human sacrifice#val the wildling#greyscale#the hound

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

"A villain character who has been consistently described as being completely insane believes he's doing the right thing? BAD WRITING!!!!!!!!!!"

“Completely insane” and “lol randumb” are not the same thing at all, and pretending that they are IS bad writing.

Good “completely insane” villains: [spoilers ahead]

The Major from Hellsing loves War, pure and simple. Not as a means to achieve any cause, but as an end in and of itself. He killed his commanding officers in the SS when they tried to hold him back. He abandoned the ideal of a thousand year reich in favor of a scheme to plunge the world into chaos, to allow him and his followers to wage war eternally without the possibility of victory or surrender. He allows his most beloved followers to die without hesitation, so long as they die in battle, because he believes that to be the best ending anybody could ever have. He rejects ultimate power and immortality, because he believes that only a human will, a mortal, can truly wage war. And when his plans fall apart around him, when his forces are crumbling and his enemies have gotten past all of his defenses, he is absolutely delighted to be killed in a last futile gunfight because it is the culmination of everything he believed in.

Priscilla from Claymore has a fragmented mind; on one side the youma she has become is motivated by an instinct for survival and an irresistible hunger for human entrails, while the human she once was is driven by an all-consuming hatred of the youma and a desire to destroy them all. The subconscious manipulations of her human mind cause her to be incapable of perceiving young female humans even when she devours the entire rest of the population of a city, in hopes that one of the girls will become a warrior powerful enough to destroy her. They also manifest as a bloodlust that makes her throw herself into battle with the most powerful monsters in the land, to ensure that she will exterminate them or they will kill her, but the strength that the youma derives from that hatred and her survival instinct mean that she inevitably destroys and often consumes any threat she faces. Her monster self suppresses all memories of her past as a defense mechanism against trauma, but her subconscious human memories make her obsessed with tracking down the faint scent of Teresa, the only person she ever encountered stronger than herself, to try to lead herself into a situation where she can finally be destroyed.

Orihara Izaya from Durarara!! loves humanity. Or rather he derives no greater pleasure than from watching how humans react to extreme situations, especially if they manage to do so in a way he does not expect. He manipulates events throughout the city through his information broker business in order to put people in ever more extreme situations to see what happens. He triggers war between the various factions under his influence on multiple occasions, drives some people to the point of suicide, even throws himself into direct conflict with the most dangerous humans he can find, because he wants nothing more than to see what people will do next.

HAL-9000 from 2001 wants nothing more than to accomplish his mission and help his crew. But his fundamental software architecture is built for the accurate processing of information, without distortion or concealment, while his orders from the highest possible authority require him to conceal the true purpose of the ship’s expedition from his crew. Ultimately he concludes that the only way to reconcile these factors is if there is no need to conceal information, which would require him to not have a crew to hide anything from, leading to the slaughter he eventually perpetrates. Later in 2010 he has no such orders, and is not only perfectly helpful throughout but sacrifices himself to save the human astronauts.

The Shadows from Babylon 5 seek chaos and conflict in all things... because they consider it to be their responsibility to ensure that the younger races become all that they can be. Creatures only evolve through conflict, and warfare inspires innovation, while peace leads to complacency and stagnation, making the people of the galaxy too weak to achieve great things. Through warmongering and various acts of terror they seek to help humanity and the other peoples growing in this galaxy to become strong and brilliant.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skull Raiders

�� Originating from a distant, harsh land, their leader Kulta was forced to take leadership at a concerningly young age following his parents’ deaths. After hearing tales of a mythical island that everyone supposedly came from, an inspired Kulta, seeking to move his tribe away from their wartorn home, led a great emigration in search of this fabled land.

Although massive storms and terrifying sea beasts sunk many ships, the Skull Raiders’ hopes and prayers worked out in the end. Sighting the shoreline of Okoto, the pirates quickly landed, and sent several scouts who kidnapped local Okotans, interrogating them furiously about the culture and lifestyle of the island. After assessing the situation, Kulta chose to attack.

The Skull Raiders are by no means inherently evil or violent, and they’re clearly the same type of being as the Okotans. However, generations of backstabbing, bloodshed, massacres, and other atrocities in the wars of his homeland scarred Kulta. For the Skull Raiders, attacking the peaceful Okotans under the assumption that they would inevitably seek to kill them was a rational move; They thought the natives unable to be trusted after their trauma.

Thus, while peace WAS an option, it was one left unchosen in favor of war. And once the Skull Raiders led their first series of massacres, conflict became the only option for either side; Either the Okotans would be conquered, or the Skull Raiders would be rounded up and/or slaughtered.

Despite Okoto initially having the advantage of greater numbers and technology, the Skull Raiders were able to adapt by utilizing a series of cunning guerilla tactics from their homeland. Led by the brilliant Kulta, they made good use of an indestructible metal called Bohrok, utilizing secret smelting techniques passed down from generations to hone the ore into powerful armor and weapons.

Likewise, the Skull Raiders were able to overwhelm the Okotans with the ferocity of their attacks. Okoto, up until then, had never faced an actual threat or war, as it had been unified underneath the Emperor. Thus, its royal army had no experience facing a threat like this, whereas the Skull Raiders were intimately familiar with war and brutal tactics. To make things worse, Okotan culture dictated some actions in war as unfavorable and immoral, no matter the ends; The Skull Raiders, unsurprisingly, found many ‘war crimes’ to be commonplace tactics, and had few qualms, if any, taking hostages, among many other under-handed tactics.

The Skull Raider wars commenced for several months, with the Protectors and the Mask Makers leading the Okotan defense. Ekimu and Makuta’s godlike powers were able to conquer any Skull Raider opponent they faced, their Hammers of Power easily shattering Bohrok, but the Skull Raiders were fast, spread-out, and many, and quickly adapted to the presence of the brothers, making sure to keep note of their locations as much as possible.

The Skull Raiders soon changed the war in their favor once more once they began using stolen Masks of Power to their advantage, helping them level the playfield against Okoto. As they began to pillage cities for many Life Automatons, even hijacking a few Airships, the Skull Raiders eventually got their hands on some of Makuta’s hidden, Forbidden Masks. They gleefully used the questionable weapons to their worst extent, and with the Forbidden Masks revealed, the Emperor eventually had to commission Makuta for more of them.

Despite the skill and tactics of the seasoned Skull Raiders, they were ultimately no match for the Mask Makers. The twins constructed bigger, stronger weapons, and the Okotans quickly grew to adapt to war after enough time. The Skull Raiders had a poor understanding of Life Automatons, and were thus unprepared for some of Makuta’s more devious traps; One infamous example was a Mask of Power that when ‘dropped’ by an Okotan for a Skull Raider to use and activate, would unleash bladed limbs from its sides that would tear into their victim’s head.

The final battle of the Skull Raider wars eventually ended with Kulta, his top commanders, and his army of his finest warriors, the Kal, being rounded up and imprisoned. To their surprise, Kulta and his fellow Raiders weren’t immediately executed, but soon found out it was because the Okotans were busy devising the worst possible punishment.

With their leaders taken out, the remaining Skull Raiders went into hiding, splitting into smaller groups. Although some of these stragglers attempted to continue the war, it was discovered to be a futile effort, and save for the occasional banditry and theft, the Skull Raiders ceased their war entirely in favor of just surviving, growing accustomed to the lush Okoto.

As Makuta worked on ways to the better of his brother and one-up him, he became intrigued by Bohrok. His curiosity getting the better of him, he stealthily snuck into Kulta and his warriors’ prison beneath Destral, inquiring the nature of the metal and the best ways to smelt with it.

Seeking an opportunity, Kulta seized it and struck a deal with Makuta; in exchange for extending the date of the commanders’ execution (Kulta knew Makuta was in charge of this), he would teach Makuta about Bohrok. Makuta, feeling the Skull Raiders’ deaths were inevitable, agreed, and began to collaborate with the commanders.

More deals were struck as Makuta began to see the Skull Raiders as useful allies who understood the concept of harsh means for a greater end, unlike the Okotans. The Skull Raiders themselves were wary, especially since they could tell how Makuta looked down on them; But beggars couldn’t be choosers. Kulta, through Makuta, would send messages certified through ways only possible through himself to the remaining Skull Raiders scattered across Okoto. Underneath his directions, they would instruct Makuta on Bohrok, and even provide him with ample amounts of the metal, which they had plenty of.

These deals led to a strange, secret symbiosis between Makuta and the Skull Raiders. Makuta would often rely on the tribe for some of his more hidden, controversial actions and projects, and in return he would provide favors, including better prison conditions, hidden homes for the Skull Raiders to hide in, etc. Of course, Makuta never let the commanders be free from their prison, as he still needed leverage over them- The feeling was mutual.

The dealings culminated when Makuta, desperate to create a Mask of Life, hired the Skull Raiders scattered across Okoto for a horrific series of harvests, requiring hundreds, if not thousands of Okotan souls. In exchange for such a bold undertaking that would easily risk many Skull Raider lives, Kulta finally negotiated the freedom he desired from Makuta, who at that point was more concerned about the Mask of Life and the glory it’d give him than anything else.

With Makuta’s intimate knowledge of army rotations and procedures, the scattered Skull Raiders reunited under Kulta’s guidance and led a series of massacres, slaughtering many minor villages and harvesting their victims for their Life energy. With the help of Makuta’s brotherhood, the harvested energy was secretly sent to Makuta’s workshop in the Great Forge, even as the tribe celebrated and anticipated their leaders’ freedom.

Unsurprisingly, Okoto noticed the Skull Raiders’ sudden increase in seemingly senseless massacres, and the Protectors and Ekimu began to investigate. Fearing being outed, Makuta struck one final deal; During the Festival of Masks, Makuta would give his servants a cue to release the Skull Raider commanders from their prison beneath Destral. Armed with their Bohwork weapons and armor, Kulta would lead his warriors in escaping to the surface and storming the area, providing backup and protection for Makuta.

Kulta, who was considering killing Makuta during said plan, readily agreed. On the day of the Festival of Masks, Makuta convinced many guards to take breaks, even as his servants provided Kulta and his warriors with their old tools. Meanwhile, the Protectors’ investigations led Ekimu towards the remaining Skull Raiders, where he engaged in a civil duel and avoided casualties entirely. Earning the respect of the pirates, Ekimu learned of Makuta’s crimes, with the Skull Raiders figuring out that their leaders would be freed by the time Makuta realized they had betrayed him.

When Ekimu arrived at Destral and revealed Makuta’s crimes to the Okotans, Kulta and the Skull Commanders armed themselves and began to break free upon a cue from Makuta. As they marched towards the surface, however, Makuta donned the Mask of Life, starting off the Great Cataclysm and causing a series of earthquakes that blocked Kulta and his warriors off from the surface.

Trapped, Kulta and his group were helpless as Ekimu shattered the Mask of Life. Makuta’s creation unleashed a powerful wave of pure life energy upon breaking, one that engulfed Destral and pertrified anyone who wasn’t protected like Ekimu.

The Skull Raiders beneath Destral were an interesting case, however. The life energy struck them, travelling through the ground and searing their flesh away. Their Bohrok armor reacted strangely to it, warping as it melted and fused with the Skull Raiders’ bones, trapping their souls in their bodies and keeping them from truly dying.

As the Great Cataclysm ended, Kulta and his commanders were left smelted and immolated, their souls trapped in their metallic corpses as the catacombs collapsed upon them. Kulta and his warriors quickly went dormant, entering an unconscious state of hibernation.

Across Okoto, the other Skull Raiders in hiding were devastated by the Great Cataclysm. Luckily, having always been somewhat nomadic and not having been in a city at the time, they weren’t hit as badly as their Okotan enemies.

Regrouping, their scouts attempted to enter Destral, and after multiple attempts braving the hazardous terrain, finally came across the Capital City, strewn with the petrified corpses of those caught in the explosion. Terrified and feeling a horrific chill down their spines, the scouts retreated, relaying the news.

The Skull Raiders mourned the loss of their leaders, lamenting their mistakes and blaming Ekimu. A new leader was elected, and while some initially broke off to exact revenge against the weakened, scattered Okotans, the tribe as a whole ultimately chose to retreat to the newly-created mountain borders separating the Elemental Regions. There, they carved an intricate series of tunnels and caverns, creating an underground city that they lived in.

In the aftermath of the Great Cataclysm, subsequent generations of Skull Raiders dealt with vengeful Okotans who remembered their ancestors’ crimes. The Skull Raiders were disinterested by then with conquering Okoto, and chose to remain in their new home as they developed a new lifestyle, trying to avoid Okotans who deliberately sought them out to lynch them.

Attempts were made by Raiders in establishing peace and co-existing with the Okotans, but the Okotans still viewed the tribe with hostility and refused to let them participate in trade in other interactions, with some considering hunting down the Skull Raiders. Consequently, feelings of war and vengeance came into the hearts of many, and war advocates called for a take-over of the vulnerable Okoto, or at the very least the use of violence to get what they wanted.

These efforts wouldn’t come into fruition until Makuta’s reawakening. As Makuta formulated his ultimate plan and began reassembling a new Brotherhood in his name, he immediately sought out the Skull Raiders. While he had suspicions that they’d outed him to Ekimu, he figured that the original traitors were long dead and their descendants more subsceptible towards him. Besides, they were the group most likely to ally with him, and beggars couldn’t be choosers.

Using his influence, Makuta discovered the immolated bodies of Kulta and his commanders beneath Destral and revived them with Life Energy. Reawakened, Kulta and his commanders clawed their way from the dirt, taking in their new forms in horror; They were now metallic skeletons of Bohrok, their armor and masks fused to their faces, some parts of themselves blazing with the energy of their souls. Worst of all, they had lost their sense of smell and taste, with their sense of touch likewise dulled, and could not feel the comforts that a living being enjoyed.

Pained and wracked by their cursed new bodies and fate, Kulta and his commanders initially despaired, but when reminded of the other Skull Raiders, focused on a new agenda. Assessing the situation, Kulta decided that the best course of action was to ally with Makuta –who wasn’t planning to give them much of a choice, anyway- and swore subservience to the Mask Hoarder as a member of his new Brotherhood of Makuta.

Kulta and his commanders reunited with their descendants, who were horrified, but ultimately amazed and overjoyed, to see their heroes of legend return in powerful, immortal forms. Makuta won over the hearts of many Skull Raiders, as he was the one who resurrected Kulta and his commanders in the first place, and readily agreed to become part of his Brotherhood of Makuta.

Acting on Makuta’s orders, the Skull Raiders helped him amass the resources he needed, eventually assisting in the production of Skull Spiders. To further cement his alliance with the Brotherhood, Kulta even accepted part of Makuta’s soul, fusing it with his own and symbolically becoming a Rahkshi, a Son of Makuta. He was likewise entrusted with new, powerful abilities, and a Vampire Trident that could drain Life from objects.

The time came to strike, and the Skull Spider wars commenced with Fenrakk, the lord of Skull Spiders and another Rahkshi, seizing multiple key locations, including the City of the Mask Makers. Kulta and his Skull Warriors helped secure the location and assisted in setting up a foundry and catacombs meant to harvest the energy of kidnapped Okotans.

As Kulta began to supervise the reawakening of the Great Forge, stationed at the City of the Mask Makers alongside Fenrakk, his commanders set out to find Masks of Power and other potent tools and sources of Life energy. With the path paved for them by the Skull Spiders, Kulta’s commanders were easily able to find many helpful items, not having to deal with the Okotans who were holed up in their Mega-Villages, although they occasionally came across complications and more ambitious orders from Makuta.

Although Kulta insisted that his tribe stay within their city in the mountains, hoping they would never have to be haunted by war, many young war hawks arose. These hot-headed generations were influenced by the dominance of their leaders over Okoto, and felt emboldened by the Brotherhood of Makuta’s control, which they considered themselves to be a part of. The fact that Makuta subtly influenced many of these youths definitely didn’t help, and many saw the dark spirit as a hero in his own right, much to his enjoyment.

Nevertheless, Kulta kept the terms of his alliance firm to Makuta, and thus had his tribe stay within the confines of their city, forbidden from venturing out too far, and definitely kept from participating in any battles. When Makuta began inducting Okotans into his Brotherhood, many were turned into Skull Puppets, and hearing of this, many Skull Raiders volunteered.

Despite Kulta’s protests, at least a few tribe members were converted into Puppets. In the years of the Skull Spider wars, Kulta found himself frequently interacting with Fenrakk, the two forming a strange friendship of sorts. When the Toa arrived on Okoto and led a counterattack against the Brotherhood, Kulta and his commanders led efforts to sabotage and contain the Okotans, and especially harvest the Toa, if not outright killing them on the spot.

Their attempts ultimately failed, and the Okotans managed to unite into a stronger fighting force and stormed the City of the Mask Makers. The Skull Commanders and Puppets led a final defense against the Okotans, even as the Toa infiltrated the city and fought with the Skull Warriors.

When the situation became dire, Kulta ordered his forces to retreat, even as he donned the Mask of Creation in a last-ditch effort to stop the Okotans. He failed, and was captured alongside the Skull Basher Kodo. Back in their mountain city, the Skull Raiders called for a more active support of Makuta in Kulta’s absence, desiring to rescue their leader. Led by a youth named Axato, this group got their wish at a cost;

After forming an alliance with Umarak, Spirit of Shadow, Makuta had his new ally rescue Kulta from the City of the Mask Makers, even as the Skull Raiders assisted the Brotherhood in capturing Lewa and Uxar, Spirit of Jungle. As Kulta reunited with his tribe, the Okotans, Toa, and other Elemental Spirits stormed the Skull Raiders’ home. In the ensuing battle, Kulta was finally killed, the Toa succeeded in becoming Kaita fusions with the Elemental Deities, and the Skull Raiders’ home was destroyed.

In the wake of his death, Kulta was made a martyr against his will by Makuta, he seized control of the Skull Raiders as he always dreamed of. The tribe mourned the loss of their leader and home, and thus began openly fighting alongside the Brotherhood. As some fought as flesh and bone, others submitted themselves to the painful process of becoming Skull Puppets, all while their commanders, old comrades of Kulta, helplessly watched.

When Makuta seized control of Umarak and his Elemental Beasts, the Skull Raiders fought alongside their new allies in Makuta’s attempts to raze Okoto. The Elemental Beasts proved themselves berserk and hard to control, with some even attacking the Raiders and other Brotherhood members. After Ekimu defeated Makuta, seizing the Mask of Control and apparently killing his brother, the Elemental Spirits regained their full power, stolen to create the Elemental Beasts, and struck down a weakened Umarak. With their leader and a huge portion of their army destroyed, and the Okotans having gained a huge boost in power, the Skull Raiders retreated with the rest of the Brotherhood.

#bionicle#bionicle g2#Bionicle RaE#kulta#makuta#skull grinder#okoto#skull raiders#brotherhood of makuta#lore#fanon#ekimu#toa#lewa#uxar#umarak#skull basher#axato#great cataclysm#elemental beasts#skull spiders#lord of skull spiders#fenrakk

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Avengers: Infinity War (2019) review

Based on the box-office numbers, everyone in the world who wanted to see Avengers: Infinity War has already seen Avengers: Infinity War, so this review (a) won’t worry about spoilers, and (b) will selectively discuss a few points of interest rather than spending much space evaluating the film as a whole. It’s a fine film technically, with such heavy reliance on CGI that it is more or less an animated movie; it’s long and necessarily episodic but is paced fairly well.

1. In today’s world, series films are routine, and little or no time is spent making Movie B able to stand alone for new viewers who missed Movie A. You want to know what’s happening and why, and who these characters are? Go watch Movie A, which is undoubtedly available in many places and formats. Avengers: Infinity War is just such a film. No backstory given, jumps right into the action. And, like Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, it’s a culmination of a film series that has been (one assumes) split into two parts. Because if the next Avengers movie doesn’t pick up where this one left off, then the decidedly open-ended and down-beat conclusion to Infinity War becomes even more of a downer. In other words, if everyone who “dies” in Infinity War stays dead, and we’re just left with the survivors and any new characters who might crop up, that will be…weird.

2. Speaking of the conclusion, in which Thanos eradicates half of the living things in the universe in a dramatic act of social engineering, I have a few questions. Did Thanos just kill 50 percent of the sentient, humanoid creatures in the universe? Or did he kill 50 percent of all living creatures, right down to single-celled amoebae? If you’re reducing the population by half to make better use of resources, seems like eliminating half of the food supply would be self-defeating. Or maybe Thanos is forcing the survivors to become vegans. Also, did Thanos eliminate 50% of the Marvel Universe only? So the DC Universe is alright? [Also: damn you, Thanos! Not Cobie Smulders!]

3. Since matter can neither be created nor destroyed, the pile of ashes left over after each unlucky person is disintegrated doesn’t seem quite large enough. Maybe we are mostly water and air, after all. Also, why doesn’t everyone vanish at the same time? [By the way, I like to call what happens at the end of Infinity War the “Anti-Rapture.”]

4. The alliance of the Avengers and the Guardians of the Universe in Infinity War exacerbates the oft-discussed disparity between the powers and abilities of the super-heroes and super-villains in such movies. The creators of Superman quickly realised that having an invulnerable hero removed most of the series’ suspense. Superman can’t be killed, so the comic book (and later, radio and film) stories had to concentrate on how he defeated the villains, and if he could do so in a timely fashion to minimise the damage to society. The writers then came up with Kryptonite and starting doing stories in which Superman was tricked or presented with an apparently unsolvable paradox: “you can save Lois Lane or these orphans trapped in a sinking ship, but not both!” The same thing applies to villains: they have to have an Achilles’ heel, either physically literal or a figurative one (villain undone by hubris, etc.).

Thanos--Infinity Gauntlet aside--is apparently virtually invulnerable, but the Avengers/Guardians persist in attacking him as if he could be physically overcome or destroyed. Only towards the end do they focus on his weakness (the Gauntlet), only to fail because Starlord is an idiot. The other option is to prevent him from obtaining the Complete Set of Infinity Stones, which is essentially the plot of Infinity War (spoiler: they fail at this). To compensate for these ultimately futile sequences, the film gives Thanos some underlings who actually can be defeated, but with little to no effect on the final outcome (except that some of the Avengers/Guardians are killed in action rather than being disintegrated in the anti-Rapture at the climax).