#and the book describs her witness reports to the police to reveal her to be ‘something of a romantic’ (paraphrased)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

buckle up everyone skenp is about to have a daydreaming session like a fucking idiot again

#remember in dr jekyll and mr hyde when that girl witnessed mr hyde beat that old man to death trough the window as she was going to bed#and the book describs her witness reports to the police to reveal her to be ‘something of a romantic’ (paraphrased)#because as part of her nightly routine she would sit by the window and daydream for awhile#remember that? thats how i feel#and i thought this was something everybody did but maybe its that both of my sisters have adhd or something….#but most people i know have told me they arent capable of sitring down and just. thinking for long periods of time#like without doing anything or listening to music or a podcast or anythinf#just kinda. sitting. and thinking and imagining stuff#anyway thats what im gonna do now. only posting this here because i promised id shut up on my main#cherry chats#artgggrghh. wish me fuckin luck kids

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

To track the ‘incel’ diatribes uttered and read by Jake Davison, murdering women can seem like the logical conclusion to their seething hatred.

The hours after a fatal attack on members of the public are harrowing. Confusion reigns, rumours swirl and anxious people try to contact loved ones to make sure they are safe. Last Thursday evening, as reports of gunfire and possible fatalities on a housing estate in Plymouth began to circulate, the question of whether it was a terrorist incident was at the forefront of everyone’s minds. When Devon and Cornwall police announced it was not terrorism-related, I wondered how they could be so sure – and their judgment has been called into question by everything that has emerged since.

We now know that 22-year-old Jake Davison was a misogynist who shot dead his mother, who had recently been treated for cancer, before taking the lives of four others. There are parallels between Plymouth and the Sandy Hook massacre in Connecticut in 2012, when Adam Lanza shot his mother five times before going to a primary school where he killed 20 children and six adults, all women. Not for the first time, the significance of extreme misogyny in the genesis of a fatal attack on members of the public seems to have been missed.

It is hard to see how Davison’s actions fail to meet the government’s definition of terrorism, which includes “the use of threat or action… to intimidate the public”. Examples include serious violence against one or more people, endangering someone’s life or creating a serious risk to the health and safety of the public: tick, tick and tick. But here is the get-out clause. The definition stipulates that terrorism must be “for the purpose of advancing a political, religious, racial or ideological cause” and it is often argued that even the most extreme misogyny does not meet that test.

It seems that its deadly interaction with other forms of extremism is poorly understood, something that struck me forcibly after the Manchester Arena bombing in 2017. Five years earlier, Salman Abedi was already showing signs of being radicalised, but the significance of his assault on a young Muslim woman at college was not recognised. Abedi punched her in the head for wearing a short skirt, almost knocking her out in front of witnesses. It was an act of staggering brutality, displaying a toxic combination of misogyny and allegiance to Islamist ideology, along with a low threshold for violence. Yet Abedi was not charged. Greater Manchester police dealt with the incident through restorative justice and Abedi owned up to anger management issues, avoiding a referral to the Prevent counter-terrorism programme. In what seems to be an example of history repeating itself, it has been revealed that Devon and Cornwall police recently restored Davison’s firearms licence, which he lost in December, after he agreed to take part in an anger management course.

Yet Davison made no secret of his seething resentment of women, posting hate-filled diatribes on YouTube. He compared himself to “incels” – involuntary celibates – angry young men who blame women for their inability to get sex and revealed an obsession with guns. In a video uploaded three weeks before the shootings, he came close to justifying sexual violence. “Why do you think sexual assaults and all these things keep rising?” he demanded in a 10-minute rant, claiming that “women don’t need men no more”. One of the questions Devon and Cornwall police need to answer is if they were aware of the content of Davison’s social media posts when they returned his licence.

In North America, incels have been linked with white supremacy, as well as being held responsible for the murders of around 50 people. In Canada, their ideology has been designated a form of violent extremism following an attack on a Toronto massage parlour last year in which a woman was stabbed to death by a 17-year-old man. It was the second such attack in the city in two years, after a self-described incel drove a van into pedestrians in 2018, killing 10 people.

In the UK, however, misogyny is not even widely recognised as the driving force behind violence against women. Time and again, we hear about men who supposedly “just snapped” and killed their female partners in what the police describe as “domestic” and “isolated” incidents. Not so isolated, given that 1,425 women were killed by men in the UK between 2009 and 2018, but we are expected to believe that such homicides could not be predicted or stopped. In fact, it is rare for a woman to be murdered by a current or former partner without a previous history of domestic abuse.

Hatred of women is normalised, dismissed as an obsession of feminists, even when its horrific consequences are staring us in the face. In June last year, two sisters, Bibaa Henry and Nicole Smallman, were murdered in a north London park by a teenager. Danyal Hussein, now 19, had been referred to Prevent after using school computers to access rightwing websites, but was discharged after a few months with no further concerns. What seems to have been missed is his virulent misogyny, which led him to make a “pact” with a “demon” to kill six women in six months.

Five years ago, I began to notice how many men who committed fatal terrorist attacks had a history of misogyny and domestic abuse – practising at home, in other words. No one would listen so I wrote a book about it, listing around 50 perpetrators who had previously terrorised current and ex-partners. It was published in 2019 and inspired groundbreaking research by counter-terrorism policing, showing that almost 40% of referrals to the Prevent programme had a history of domestic abuse, as perpetrators, witnesses or victims. Project Starlight has produced a number of recommendations, arguing that counter-terrorism officers need to look for evidence of violence against women when they are assessing the risk posed by suspects.

That is a welcome development, but we need to go further. We are all in shock after hearing about the horrific events in Plymouth, while the grief of the victims’ families is awful to contemplate. But Davison’s murderous rampage demonstrates that our understanding of what constitutes terrorism is too restrictive. Extreme misogyny needs to be recognised as an ideology in its own right – and one that carries an unacceptable risk of radicalising bitter young men

186 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Bizarre Disappearance of Cindy Anderson

Cynthia 'Cindy' Anderson was living in Toledo, Ohio in 1980 when she began to complain of nightmares that were plaguing her, this continued for almost an entire year. She once told her mother that in these nightmares a stranger would break into their home and take her away, her mother didn’t think of them as anything other then nightmares.

Cindy was working for a law firm at the time called Rabbit and Feldstein. On August 4th 1981, she had arrived as usual and kept the offices locked as she wasn't expecting anyone in all morning.

At 12pm some co-workers arrived to find the office locked up and Cindy was nowhere to be found. Her co-workers searched the property and found things that made then suspicious she may have been abducted, they immediately called the police department.

It was established early on that whatever had happened to Cindy had likely happened early on the day she disappeared. While it was known she had arrived for work around 9am and had been last seen by anyone in the office at 9:45am, at 10am several phone calls had been made by a client to the office and had gone unanswered.

The days mail was found still in the doors letter slot and the lights and Radio were still on as was the air conditioning which was always turned off when the office was unoccupied. Cindy's car, a 1980 Chevrolet Citation was still parked outside and the doors had been locked and alarmed when her co-workers arrived. The only items missing other then Cindy were her Car Keys and Purse.

Most chillingly, a book Cindy had been reading was left open on her desk on a paragraph that described the character being violently abducted. Police considered that Cindy may have been trying to leave a message her abductor wouldn't have noticed.

A colleague at the office later told Police he had witnessed Cindy receiving phone calls at work that had seemed to distress her just a day before she had disappeared. She didn’t tell him what the calls were about when he asked her though he reported it to the police as soon as he heard of her disappearance.

Ten Months before Cindy vanished, someone had spray painted the words 'I LOVE YOU CINDY - BY GW' on a wall across the street from the office. It took several months before the graffiti was removed and only a few weeks after it was the message was sprayed on the wall again. Police would take this message very seriously during the investigation, they believed it may have been written by the maintenance man who worked at the office and had the initials GW but couldn't place him in the area at the time of her disappearance. In the mid-90's the police revealed that the person who had written the messages had been identified but wasn't believed to have any connection to her disappearance.

A month after Cindy had disappeared, the police received an unusual call from an unknown female that claimed Cindy was being held against her will. The tip told police that Cindy was being held captive in the basement of a White House and that there was two of these houses side-by-side that belonged to one family. The tipster went on to explain that the family were out of town but their son was home and he was the one holding Cindy. The tipster never gave an address and hung up when the police pressed them for information. The same tipster called again a few minutes later but hung up again when they heard another officer pick up an extension to listen in.

A chief suspect in the case was Jose Rodriguez Jr, a local criminal who had been represented at the time by one of Cindy's bosses, Richard Neller. Both Neller and Rodriguez along with 7 other men were arrested as part of a large drug trafficking bust a few years after Cindy had disappeared. During the 1995 trial for drug trafficking a witness testified that Rodriguez had confessed to killing Cindy in order to punish Neller for not adequately representing him at a previous trial. The police could never confirm the story.

There was no sightings of Cindy after her disappearance and no one has tried to access her finances or use her Identity. Cindy has been missing now for almost 40 years and at this point it's unlikely the case could be solved without someone coming forward with new information or further evidence being discovered.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Murder of Elisa Izquierdo

Elisa Izquierdo was a 6-year-old Puerto Rican/ Cuban- American girl. she was born in Brooklyn, New York.

When Elisa was born her mother was addicted to crack cocaine and full custody was awarded to her father. Elisa's father was a doting dad who rose to the challenge, taking parenting classes and celebrating Elisa's birthdays happily with her. He would refer to Elisa as his 'princess.'

The year Elisa began preschool, Elisa's mother, Awilda, was described as successfully beating her addiction and marrying a maintenance worker. Carlos Lopez. In November 1991, Awilda got the rights to unsupervised visits with Elisa. Reportedly during these visits, Elisa would be beaten and neglected by her mother and stepfather. Both Elisa's father and her teachers noted Elisa had bruising and signs of mistreatment when she returned from these visits. She said her mother had hit her repeatedly and that she did not wish to see her mum again. In the lead up to Elisa's visits with her mother, Elisa would wet the bed and have frequent nightmares, she would also vomit upon her return from these trips. Elisa's father reported this abuse to the authorities and applied in 1992 for Awilda's visitation rights with Elisa to stop however the courts ruled the visitations could continue but warned Awilda not to hit her daughter.

In 1993, Elisa's father made plans to relocate with Elisa to Cuba, he bought airline tickets for both of them for May 1994. The story took a tragic turn when Elisa's father was admitted to the hospital with respiratory complications and was diagnosed with lung cancer. On the very day he booked the plane tickets for he died. Upon hearing about his death, Elisa's teachers contacted a court judge expressing concerns about Elisa's care if her mother was to gain full custody.

Awilda applied for full, permanent custody of Elisa. Elisa's paternal aunt attempted to challenge this custody and asked for custody of Elisa herself but was denied. Awilda's application for full custody of Elisa was granted in September 1994.

When Awilda was given full custody she changed Elisa's school to a public school. Elisa was observed as withdrawn, disturbed and uncommunicative. In March 1995, an anonymous letter was sent to Child Welfare Authorities informing them that Awilda had been cutting off Elisa's hair and locking her in a dark room. Six days later, Elisa was admitted to hospital with a fractured shoulder that had not been treated for 3 days. Elisa's school continued to report concerns but were told their worries were 'not reportable' due to lack of evidence. Awilda eventually fully withdrew Elisa from school.

Elisa was repeatedly locked in her bedroom and not allowed to talk to others. Neighbours reported hearing the young girl pleading with her mother not to be beaten and crying late into the night. She was sexually violated, forced to eat faeces and burned among other horrific abuses.

On 15th November, Elisa is thought to have died after being thrown against a wall days earlier. The police were called by a concerned neighbour and Awilda and Elisa's step-father were both taken into custody. An autopsy revealed a catalogue of traumatic and horrific injuries including broken fingers, damage to organs, deep welts and burns and evidence of sexual assault. The injuries had been sustained over a prolonged period.

Awilda Lopez pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was offered a deal in which she would become eligible for parole after serving 15 years in prison. Carlos Lopez, Elisa's stepfather, was sentenced to one-and-a-half to three years in prison. Elisa's siblings were removed from the family home and raised in separate foster homes, all five suffered from severe psychological trauma due to the extreme violence they had been forced to witness.

The case was described by New York City authorities as to the 'worst case of child abuse they had ever seen.

#murder#homicide#childkiller#child killer#awilda#awildalopez#lopez#carlos lopez#carloslopez#crime#true crime

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter Three: The Cover

Table Of Contents

Fic summary: Owning a bookstore in downtown D.C. came with its fair share of downsides. You never thought that being the target of a serial killer would be one of them. Luckily, a nice FBI agent by the name of Spencer Reid is assigned to watch over you. What's the worst that could happen?

Pairing: Spencer Reid/Reader

Words: 2,332

MASTERLIST

~

As soon as the hospital would allow you to leave, Emily and her team drove you to the FBI headquarters where they’d brief you on the plan, whatever that meant.

By the time you’d gotten there, you’d heard more about serial killers and their behavior than you’d ever like to. It took a while for you to calm down enough to properly listen, so when you were ready, everyone was as gentle as possible.

“This unsub has killed three other women at the least,” the bald man from the hospital, Morgan, his name was, said.

“Unsub?” you asked quietly.

“Unidentified subject,” a tall, wiry man said. He seemed a little young to be working for the FBI. “He’s been targeting women of your approximate appearance, same hair color, same height.”

The man flipped over a large whiteboard to reveal pictures of women that looked remarkably like you. It was unnerving in the first place, but downright terrifying when you considered the fact that those women were dead.

“But, I mean, there’s a ton of girls who look like me,” you stuttered. “Just because I look like that doesn’t make me a target, right?”

“All the victims have been discovered wearing elaborate costumes, clothes from many different eras. With each of them, a copy of a classic book accompanied the body.” Morgan looked over the police report the officer had been taking from you. “You said you own a bookstore?”

“Yes, but that doesn’t mean there’s a killer after me!”

There was an uncomfortable silence as the team looked at each other, clearly unsure of what to say.

“What?” you prompted.

The leader spoke, Hotch.

“We have evidence that this particular unsub has been displaying stalking behavior on an unknown woman in town. Based on your recent break-in and physical appearance, we believe you may be that woman.”

“That’s a pretty big leap,” you said, doubtful. Someone just broke into your house. It didn’t mean there was a crazy stalker killer after you.

“Actually, the theft of a personal item, something that has value to you and only you: the locket, your hairbrush, signifies that the perpetrator cares less about monetary value and more about what you value. This suggests obsession and stalking behavior.”

If a dictionary could talk that’s what it would sound like.

“So, someone’s gonna kill me?”

The team hesitated.

“Unlikely,” Morgan said after a moment, “Most stalker-killers don’t intend to murder the subject of their obsession. Instead, this particular one seems to be taking it out on women who look like you.”

“So, someone is killing because of me.”

The silence was answer enough.

You weren’t sure what you had planned on doing today, but it certainly wasn’t this. Sitting in the middle of an FBI conference room surrounded by agents telling you that there was a killer obsessed with you.

“What’s gonna happen?”

A blonde woman who hadn’t spoken yet came and knelt by you.

“We���re going to place a protective detail on you. An agent will be with you at all times while the investigation continues. We’d like you to continue your routine as normal. Any change in your schedule will prompt a change in the unsub’s behavior. He’s comfortable right now and we want him to stay that way.”

Comfortable. They wanted to keep your stalker comfortable.

“Okay. What do I do first?” You just wanted them to catch this guy so you could move on with your life.

“What do you normally do on Saturdays?” Emily asked.

“It depends. It’s the only day I have off from work. Sometimes I hang out with my friend Steve, go to the park, or just stay home and chill.”

“Well, what does the rest of your week look like?”

“I’m at school from seven to three, then work immediately after. Usually, I close up at eleven so I’m home by midnight.”

A stunned silence followed this summary of your schedule.

“What?”

The skinny man spoke, “What you’ve described is roughly an eighty-eight hour work week not factoring in all the hours doing homework.”

“Fast math,” you muttered. “But, yeah, pretty much. I’m either in school, doing homework, or at work. I don’t even know why anyone would want to stalk me. I don’t do anything.”

“Nevertheless, there is someone after you,” the blonde woman said. “We’re going to have to assign someone from the team to be your protector.”

“Meaning one of you is going to have to follow me everywhere?”

It was an uncomfortable situation already and every question you asked seemed to raise the tension in the room.

“Which of you is it gonna be?” Again, the team looked around at each other, seemingly not sure, themselves.

“Why is this happening to me.”

It wasn’t a question. And they all knew it.

~

You waited patiently in the next room while the agents discussed what the cover would be. Finally, alone with your thoughts, you found you weren’t as scared as you probably should have been.

Sure, it was frightening to think there was someone obsessed with you, but you’d been in scary relationships before. And when your last ex decided to break in over a year ago, you certainly didn’t get an FBI detail. You wondered if this was at all related, making a mental note to bring it up later.

In the office next door, their voices were muffled but loud. You considered each member of the team, thinking about which one would be the best protector.

Emily was the one you’d talked to the most, Morgan seemed strong, as did the leader, Hotch. You didn’t know who the older gentleman with the goatee was, but he was probably your last choice. The blonde woman had made a nice impression. The tall skinny guy was quick-witted and you would have laughed at his demeanor if not for the serious situation you were in.

Your train of thought was interrupted by the doors opening and the team coming back in, somber but determined looks on their faces.

Hotch spoke first, surprisingly gently.

“We’ve created a protection program. There will be a surveillance team parked outside your apartment and your workplace at all times. You’ll need to stop going to school during the investigation. In the meantime, you’ll need someone to move into your apartment with you to keep a closer eye.”

“How many bedrooms is your apartment?” The skinny man asked.

“One,” at your answer, the skinny man went pink. “Why?”

“The cover we’ve created places, Doctor Reid, here—“ Hotch gestured to the skinny man “—as your boyfriend who’s just moved in with you. That way he can keep you safe in your apartment.”

“Boyfriend?” You looked at him — Doctor Reid — and he met your eyes. Upon the contact, his eyes went wide and he dropped his gaze to the floor, cheeks reddening.

“It’s the best cover to place him in your apartment,” Emily assured you.

“Okay.”

It would be strange to live with a man. Sure, you’d had guys crash on your couch before and one very short relationship where you’d moved in together. But that was after a year together. Could you deal with a strange man living in your home so suddenly?

“You should probably get going,” Morgan said, making you and Doctor Reid jump slightly.

“Of course,” the doctor said, standing. “Um, I don’t have a car.”

You felt yourself smiling for the first time all day. He’s actually rather handsome, you found yourself thinking. That thought was quickly shooed away and you responded.

“Neither do I. I like walking places. Anywhere I can’t walk, the bus is much cheaper.”

He gave you a soft, awkward smile and ran his hand through his scruffy hair.

“Well, you’ll have to use a government-issued vehicle,” Hotch said, breaking the spell between you and the doctor. “It’s safer for you to drive. Now, I want you and Reid to head over to his place now so he can collect his things to move into yours. We have a limited time frame to work in so as not to arouse the suspicion of our unsub. Remember, a security detail will be following you at all times.

“When you get back to your apartment, Reid will send the team a text. We’ll continue the investigation from afar and keep you both updated frequently. Any questions?”

He had spoken so fast, it was a lot to take in.

“Where’s he gonna sleep?” you said, feeling a blush creep up your neck.

Hotch looked at Reid, then back at you. He opened his mouth, about to say something, then thought better of it.

“I’m sure you’ll figure something out,” he said briskly and left the meeting room.

You turned to Reid and forced a smile. This morning did not go how you thought it was going to, but something about this man cheered you up whether you wanted it to or not.

“Shall we?” he said, motioning to the door and clearing his throat.

Nodding softly, you followed him out of the building and into the parking lot. He led you to a small green car that looked too . . . normal to be in the FBI car park.

“Who’s car is this?”

“It's a government issue. They have a bunch of extra cars down here for undercover work. I grabbed the keys to this one on the way out.” Then, more to himself, “I’ve kinda always had my eye on it anyway.”

He was a strange man. Not the type you expect to work for the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Even more startling was catching a glimpse of the gun on his hip as you both climbed into the car.

Reid must have noticed your sudden uncomfortability because he said, “I’m sorry about the gun, I know it can be unnerving, but it's a standard-issue. It’s to keep you safe.”

“I know,” you said shortly. You’d never liked guns. But Reid seemed to know what he was doing and, strangely enough, you found yourself trusting him.

Several minutes of total silence later, you were outside his apartment, helping him load a box of his things into the trunk.

“You really didn’t need to carry that,” he said, getting back in the driver's seat.

“I know, I don’t mind. I figure it’s the least I can do for you after all . . . this.”

He looked for a moment as though he were about to say something, then rethought it and started the car up, driving toward your apartment.

“We have to take the elevator,” you said, steering him towards the lift. He’d placed his bag on top of the box despite your protest you didn’t mind carrying something. Even though the pile was stacked so high he could barely see over the top.

“The elevator?” he groaned.

“I know, I hate it too, but the stairs are broken so we have to.”

“Isn’t it usually the other way around?” he grumbled as you rode the lift up to your floor. There was barely enough room for the two of you. It was less like an elevator and more like a small closet.

“This is mine,” you said, unlocking the door and stepping into your flat, regarding it very differently now that a stranger was with you.

“Sorry, let me just—“ quick as you could, you cleared some space on the coffee table for him to set down his things, took some dishes to the sink, and shoved a pile of dirty laundry into a basket.

He set the box down and took in his surroundings. You waited patiently for his judgment.

“Woah!” He pointed to your bedroom door where a huge Doctor Who poster was. You cringed. If you’d known you’d be having . . . company, you’d have tidied up a bit, hid some nerdy memorabilia. At least you’d closed your bedroom door.

“Oh, yeah, just ignore that. Guilty pleasure.”

He looked at you, eyes wide and smiling.

“I love Doctor Who!”

Shocked, you let a smile slip, earning one from him in return.

“Cool! Well, there’s something to do with our time together.”

Reid looked away for a moment, then regained himself.

“So, about the sleeping situation. . ?”

“Right, of course,” you grabbed some blankets from the linen closet and walked over to the couch. “Um, it folds out. Is that okay?”

“Oh, yeah, yeah!” He perked up, slumping down on the couch and getting comfortable. “I can fall asleep pretty much anywhere, it’s no problem.”

“Okay! Well, I think I’m gonna take a nap. Feel free to help yourself to any food or whatever. The bathroom is just right there. If you need anything let me know. Just make yourself at home, really.”

“Thank you, oh, um . . .” he seemed more flustered than an FBI agent should. Actually, it was kind of comforting. “We haven’t really technically met.”

Oh yeah. You hadn’t introduced yourself to anyone back at Quantico.

“Right! Um, I’m Y/N Y/L/N. I guess I assumed you already knew that. You’re Doctor Reid?”

You held out your hand for him to shake, but he just stared at it awkwardly.

“Spencer! Please, call me Spencer. Sorry for not shaking hands, but the amount of germs passed through a single handshake is astronomical. It’s amazing it’s still in practice. It’s actually safer to kiss.”

He blanched, then backtracked.

“I mean, not that that’s what I’m suggesting. I just thought it was interest— Let me try again. Call me Spencer. Please.”

He flashed you a pitiful smile, seemingly desperate for a fresh start. It wasn’t necessary though, because you delighted in the way he babbled.

“Alright, Spencer,” you smiled warmly at him. “I’m going to sleep now.”

“Sweet dreams.”

Once you’d gotten comfortable in bed, you realized there was no way you’d be able to sleep. Not with everything that happened today.

Then you thought of the handsome, smart, strong man in the next room who was dedicated to protecting you from any possible threat.

You were asleep within minutes.

~

Taglist: @aperrywilliams @mjloveskids666 @dolanfivsosxox @criesinreid @fanficsrmylife @racerparker @sammypotato67 @lukeskisses @reidcrimes @you-had-me-at-hello-dear @l0ve-0f-my-life

#spencer reid smut#spencer reid#spencer reid x reader#spencer reid gifs#spencer reid fic#fanfiction#fanfic#reid#criminal minds

274 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Zodiac Killer

The self-proclaimed Zodiac Killer is an unidentified American serial killer. He took credit of several murders in the San Francisco Bay Area between 1968 and 1969, but only five are directly linked to him. He taunted police and made threats through letters sent to newspapers in the area from 1969 to 1974. The police never caught him. The mystery surrounding the murders has inspired numerous books and movies, like Dirty Harry, in 1971, Zodiac, in 2007, and Awakening of the Zodiac, in 2017.

Zodiac Killer’s murders timeline

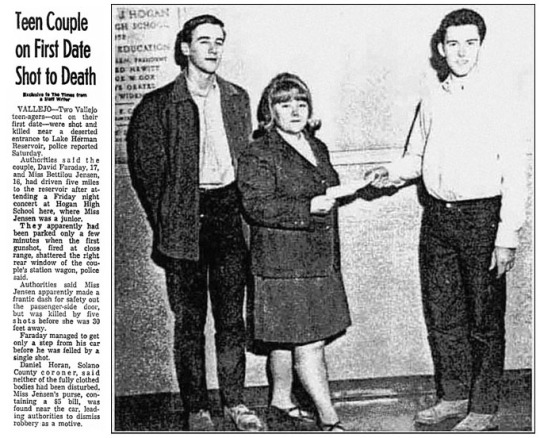

DEC. 20, 1968 The first confirmed murders attributed to the Zodiac Killer took place on the night of December 20, 1968, on Lake Herman Road, just inside Benicia city limits. The victims were high school students David Faraday and his girlfriend Betty Lou Jensen, who were shot to death in their car; shortly after 11:00 p.m., their bodies were found by Stella Borges, who lived nearby.

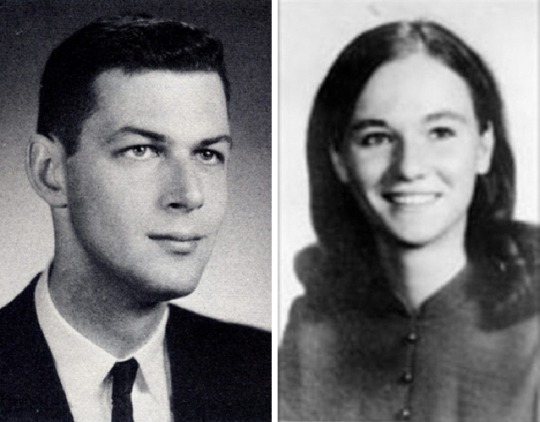

Newspaper page about the murders of David Faraday and Betty Lou Jensen

JULY 4, 1969 Just before midnight on July 4, 1969, Darlene Ferrin and Mike Mageau, her boyfriend, were sitting in a parked car in Blue Rock Springs Park, Vallejo. A car parked beside them, almost immediately drove away, and then came back after 10 minutes; the driver exited the vehicle and approached the couple with a flashlight. He shot them seven times each. Within an hour, a man called the Vallejo Police Department to report and claim responsibility for the attack; he also took credit for the murders of David Faraday and Betty Lou Jensen of six and a half months earlier.

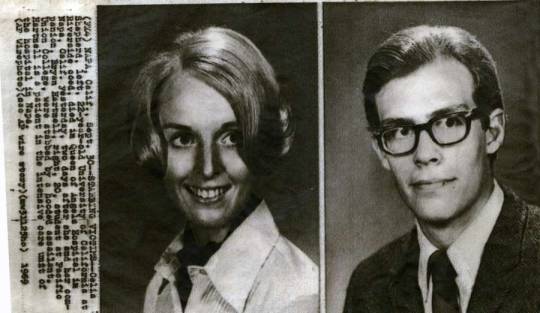

Photos of David Faraday and Betty Lou Jensen

SEPT. 27, 1969 On the evening of September 27, 1969, the Zodiac Killer approached Cecelia Shepard and her boyfriend Bryan Hartnell as they were picnicking on a shore of Lake Berryessa, in Napa County. The man was wearing a black hood with clip-on sunglasses over the eye-holes, and a bib-like device on his chest that had a circle-cross symbol on it. He approached them with a gun, claiming to be an escaped convict from a prison, and told Shepard to tie up Hartnell, before tying her up. The man drew a knife and stabbed them both repeatedly, badly injuring the couple, then went back to their car and drew the cross-circle symbol with the inscription "Vallejo/12-20-68/7-4-69/Sept 27���69–6:30/by knife". At 7.40 p.m. on the same day, he called the Napa Police Department, to report and claim responsibility for the attack. When the police arrived, Shepard was still alive and described the attacker; she died two days later at the hospital, while Hartnell survived.

Photos of Cecelia Shepard and Bryan Hartnell

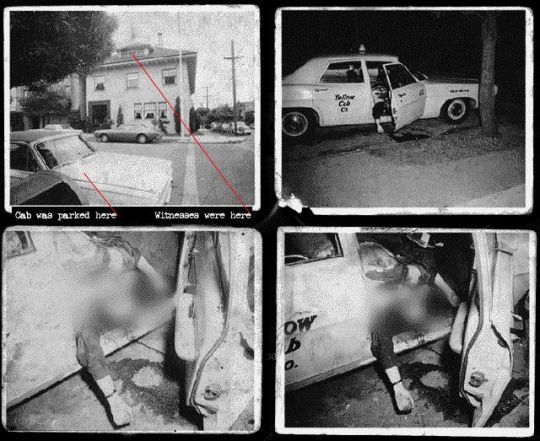

OCT. 11, 1969 Two weeks later, on October 11, 1969, taxi driver Paul Stine was found dead inside his taxi. He was shot in the head by a white male passenger, who had requested to be taken to Maple Street; for strange reasons Stine did not stop there but one block after, in Cherry Street. Three teenagers that lived across the street witnessed the passenger shooting Stine, and called the police while the crime was still occurring; they also stated that before running away, the man wiped the cab down. In the meantime, two policemen, Don Fouke and Eric Zelms, noticed a white man walking and entering inside one of the houses in the street; the suspect they were looking out for was supposedly black, and since the man they witnessed was white they did not stop him. As the murder did not seem to fit the Zodiac’s pattern it was initially thought to be a robbery, until the San Francisco Chronicle received a letter from the Zodiac Killer claiming the crime.

Crime scene of Paul Stine’s murder

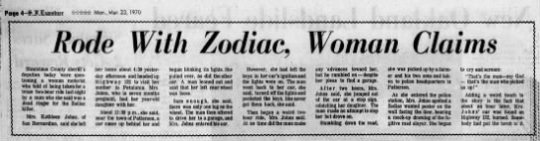

MARCH 22, 1970 On the night of March 22, 1970, Kathleen Johns was driving with her newborn daughter on Highway 132 near Modesto, when a driver flashed his headlights at them. Johns pulled off the road and stopped, and so did the man; he told her that her right rear wheel was wobbling, and offered to tighten the lug nuts. After doing such, the man drove off, and when Johns pulled forward to re-enter the highway, the wheel almost immediately came off the car. The man came back and offered to drive her and her daughter to the nearest gas station. He drove them around for a long time, passing several gas stations, and when he stopped at an intersection Johns jumped out the car with her daughter and hid in a field. She later identified her kidnapper as the man depicted in a wanted poster for Paul Stine's murder, the Zodiac. Police never officially attributed the incident to the Zodiac.

Newspaper talking about Kathleen Johns kidnapping attempt

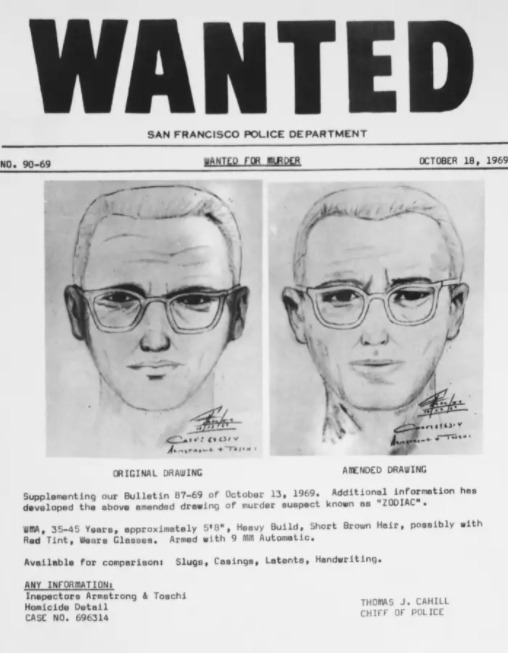

During the 1990s, many investigators claimed to have identified the Zodiac Killer; the most likely and most often cited suspect was Arthur Leigh Allen, a Vallejo schoolteacher who had been institutionalized for child molestation. The police were able to create a sketch of the Zodiac, using the descriptions of several witnesses; for example, the three teenagers who saw the man leaving the scene of Paul Stine’s murder, and Kathleen Johns, who identified the man that tried to kidnap her from the sketch of the Zodiac. Despite the mounting evidence and the numerous suspects, the killer remained at large.

Sketch of the Zodiac Killer made by the San Francisco police department

Letters and cyphers

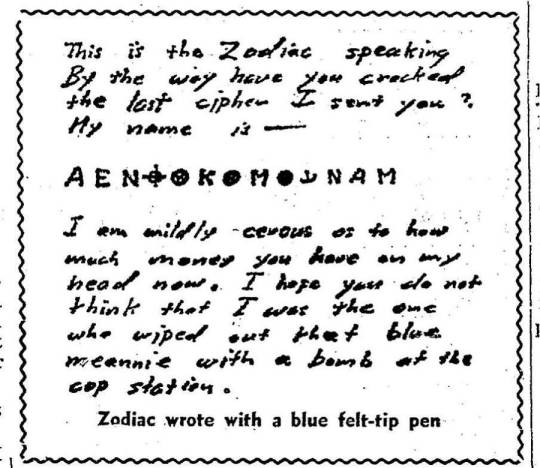

The Zodiac sent several letters containing cyphers to various newspapers located in San Francisco, the San Francisco Examiner, the San Francisco Chronicle and the Vallejo Times-Herald. The newspapers received the first letter on August 1, 1969, where the killer took credit for the Benicia and Vallejo murders. To convince the police that he was the author of the murders, he included details that only the killer could have known. Each letter was closed by a circle with a cross through it, that would later become the Zodiac Killer’s symbol. High school teacher Donald Harden and his wife, Bettye, were able to solve the first cypher.

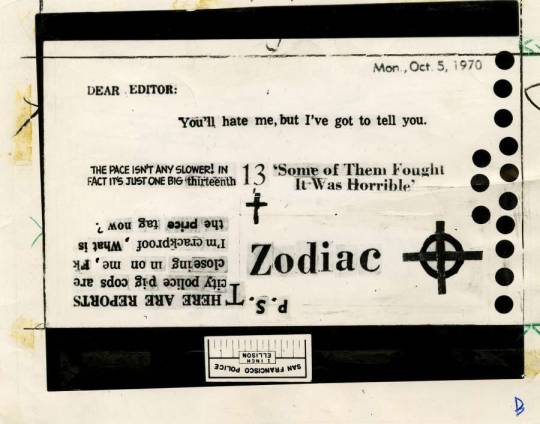

A couple of days after the murder of Paul Stine, on October 15, 1969, the San Francisco Chronicle received another letter from the Zodiac, where he took credit for the murder; this is also the first letter in which the killer uses the name “Zodiac”. At the end of the letter, the killer mused that he would next shoot out the tire of a school bus and "pick off the kiddies as they come bouncing out". The Zodiac Killer continued sending letters to the San Francisco Chronicle, where he claimed to have committed several more murders and mocked the police for their inability to catch him. The letters stopped in 1974.

In 2020, after 51 years, one of the messages written in code and attributed to the Zodiac Killer has been solved. The cypher does not reveal the killer's identity, however, it confirms his image as an attention-seeking killer who revelled in terrorizing the Bay Area in the late 1960s.

The three men who decrypted the code are David Oranchak, a software developer in Virginia, Sam Blake, an applied mathematician in Melbourne, Australia, and Jarl Van Eycke, a warehouse operator and computer programmer in Belgium. The F.B.I., which employs a team of code-crackers in its Cryptanalysis and Racketeering Records Unit, said they had verified Mr Oranchak’s claim of having broken the code.

It read: “I hope you are having lots of fun in trying to catch me that wasn’t me on the TV show which brings up a point about me I am not afraid of the gas chamber because it will send me to paradice all the sooner because I now have enough slaves to work for me where everyone else has nothing when they reach paradice so they are afraid of death I am not afraid because I know that my new life is life will be an easy one in paradice death.”

Though he had claimed to be responsible for 37 deaths, no Zodiac victims have been discovered since 1969, and in both the known and presumed Zodiac murders no suspect was ever arrested. Since the Faraday-Jensen murders, the inability to identify the Zodiac Killer has continued to frustrate law enforcement.

Sources:

Zodiac Killer - Biography

The coded message has been solved - New York Times

Zodiac Killer - Wikipedia

Zodiac Killer Timeline - San Francisco Chronicle

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Betsy Aardsma

May 09, 2021

Betsy (born Elizabeth Ruth) Aardsma was the second born in a family of four children. She was born in Holland, Michigan on July 11, 1947 to parents Esther and Richard Aardsma and grew up in a religious conservative household. Esther worked as a housewife and Richard was a salesman.

When Betsy was a child she found a love for art, poetry and developed a concern for the underprivileged. She went to Holland High School and was quite a good student, graduating with honours in 1965. Betsy had a dream of becoming a physician.

After high school, Betsy enrolled at the Hope College in the fall of 1965, to become a medical student. In the fall of 1967 Betsy enrolled at the University of Michigan to study art and English. She then began to date a medical student named David Wright, who was her first serious boyfriend. Betsy graduated from the University of Michigan with honours in the summer of 1969.

Once Betsy had graduated from university she planned to join the Peace Corps and travel to Africa, however she decided to enrol at Pennsylvania State University (known as Penn State) when she realized her boyfriend, David, would be attending there and he told Betsy he could not guarantee he would be faithful to her if she travelled abroad.

Betsy enrolled at Penn State in early October of 1969 and she lived in Atherton Hall, a residence on campus with her roommate Sharon Brandt, who said that Betsy spent her free time either studying or hanging with her boyfriend.

Thanksgiving 1969 came around and Betsy was supposedly very stressed out due to the fact that she was behind on an English assignment. She spent the day with her boyfriend, David, his roommates and their girlfriends before she returned to her dorm the following day with plans of meeting some professors for advice on the assignment.

On November 28, 1969 Betsy left her dorm with her roommate to visit the Pattee Library to get research material for her English paper. At one point her and her roommate parted ways, agreeing that they would catch up later that afternoon to watch a movie.

At around 4 pm Betsy spoke with one of her professors, Nicholas Joukovsky, where she stated she wanted to visit the Stack Building. Shortly after that she encountered two of her friends, Linda Marsa and Robert Steinberg where she had a brief conversation before entering the library. Betsy then placed her purse, jacket and book inside a carrel before walking towards a card catalog.

When she found the reference she was looking for, she began to walk down a flight of stairs to the Level 2 core stacks, around 4:30 pm. The last potential sightings of Betsy occurred minutes after 4:30 pm, when an assistant supervisor named Dean Brungart saw a girl wearing a red dress standing alone in an aisle. Dean also noticed two young men talking quietly to each other in a nearby aisle.

About 10 minutes later another witness, named Richard Allen, overheard a conversation between a male and female in the general direction of where Betsy was standing as he was using the photocopier. Richard told police he couldn’t hear what the two were saying but it didn’t sound like anything alarming to him or give off the notion that it was anything other than a normal conversation.

A few moments later Richard heard a metallic crashing noise before he saw a young man “barrel” past him. Somewhere between 4:45 and 4:55 pm Betsy Aardsma had been stabbed one time through the left breast with a knife while she was standing between rows 50 and 51 in the Stack Building of the Pattee Library.

After she had been stabbed, Betsy slumped to the ground close to the end of the aisle, falling on her back. Two other students, Joao Uafinda and Marilee Erdley observed a man running from the direction of the stabbing, concealing his right hand, and yelling, “that girl needs help!” Marilee said the man was dressed in knaki washable slacks, was wearing a tie and a sports jacket. He had well kept brown hair, was around 6 feet tall and about 185 pounds. He may have been wearing glasses.

The man apparently led Joao and Marilee into the Core, where he pointed to Betsy. Marilee began checking for signs of a pulse and Joao noticed the man leaving the library, so he followed him upstairs and aw the man run out of the library. Joao said he tried to chase the man, but was outpaced. This man was last seen running in the direction of Recreation Hall. The identity of this man has never been found.

Marilee was joined by other bystanders, including a librarian as they attempted first aid on Betsy. They called the campus hospital at 5:01 pm, and responders were initially told that a “girl had fainted” in the library. Two student paramedics came to the scene moments later and Betsy was placed on a gurney and taken to the Health Centre as paramedics tried to perform CPR on her.

Everyone, including the responders thought she had fainted at first, because she had urinated where she fell and she was wearing a white turtleneck sweater, with a red sleeveless dress over the sweater and there was only small amount of visible blood. The sweater was very thick so it wasn’t obvious that there had been a tear in her sweater.

Shortly after being transported to the Health Centre, a senior medical individual noticed the blood and they cut through Betsy’s clothes to reveal the single stab wound. Betsy was pronounced dead at 5:19 pm.

Because everyone initially thought Betsy had fainted, there was no reason to think that the library was a crime scene and the janitor had already cleaned up the urine on the floor of the aisle. Police found that about 440 students had entered the Pattee Library between 4:30 and 5 pm that day.

Multiple factors led police to believe that Betsy knew her murderer personally as she had likely been approached by this individual and had not attempted to scream or run away. Police didn’t believe she had been stalked and she had been expected to be at Penn State that day, she was supposed to be spending the day elsewhere with her boyfriend. They also found Betsy’s diary, where not once had she indicated that she felt uncomfortable by anyone at Penn State in the 8 weeks she had gone there.

Another theory is that Betsy possible saw a homosexual encounter or witnessed a man masturbating In the library and was killed to silence her. More than two dozen pornographic magazines were found concealed between books where Betsy had been murdered and there was traces of semen on the floor, shelves and walls. It seemed as though people were using this area to engage in sexual activities without being caught.

Another theory is that a Penn State professor by the name of Richard Haefner was responsible for Betsy’s murder. Haefner was born in 1943 and was described as well respected but socially awkward. He had obtained a doctoral degree in Geology from Penn State and was extremely intelligent. However, Haefner was known to have bouts of explosive anger, accusations of pedophilia and molestation and was accused of stealing the university’s rock collection.

Apparently Haefner had dated Betsy but she ended it whatever they had in October 1969 because she was becoming more serious with David. Apparently when asked, Haefner claimed he had not known about Betsy’s death until November 29, the day after it happened. However, apparently Haefner showed up at another professor’s house hours after Betsy had been murdered and said, “Have you seen the papers?” Betsy’s death had not yet been reported in the papers. This professor said Haefner’s behaviour was so strange that after he had left the professors and his wife wondered if he had had anything to do with it, though the professor never reported this to police.

Haefner was never charged and died from a heart attack in 2002. His cousin, Chris Haefner believes that he was involved in Betsy’s murder. Chris claimed one night in 1975 he overheard Richard Haefner and his mother having a conversation where he heard them talking about “what Rick had done to that girl at Penn State.”

Derek Sherwood, a man who runs the website “whokilledbetsy.org” also believes Richard Hafener was responsible. “He was there, he had intimate knowledge of [the crime], he was interviewed by police and he lied to them,” said Sherwood.

“I think that the Aardsma murder may have both burdened and emboldened Rick, if he truly committed it,” said Sherwood. “Burdened in the sense that he probably always felt that he had to watch his back for police and his past, so to speak, and emboldened in the sense that once you’ve gotten away with murder, everything else is small potatoes.”

Betsy Aardsma’s murder remains unsolved 60 years later but the Pennsylvania State Police are still actively seeking any information about the case. The above photo is that of Professor Richard Haefner and Betsy Aardsma.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Double murder in Tulilahti camping site

On 18th of July 1951, 23 years old office employee Riitta Aulikki Pakkanen and 21 years old nursing student Eine Maria Nyyssönen decided to go to a summer holiday trip, cycling from Jyväskylä to Savo and North Karelia. Eine sent a postcard on 25th of July in Koli, where she told they will additionally visit Varkaus and promised to return home on the 30th of July. On 3rd of August there were still no sign of them and people in Riitta’s work place started to get worried since her job was supposed to have started and she hadn’t come. Missing persons report was done quite quickly. The last known sighting of the women was from 26th and 27th of July when they had spent a night in a hostel/inn.

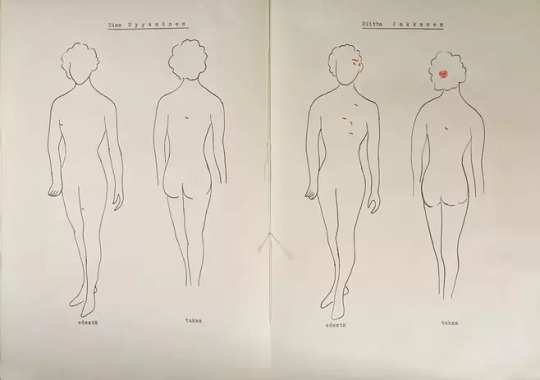

The search was started from Varkaus, the last place Eine had told they will visit, but the search wasn’t successful. On 21st of August a draftee who was part of the searching party found Riitta’s and Eine’s bodies. The women were found hidden in a swamp that was near Tulilahti camping site in Heinävesi. Eine was undressed and therefore found naked, but authorities say it wasn’t a sexual crime since the two girls were still untouched.

Riitta and Eine had arrived to the camping site on the 27th of July and put their tent on place. During the same night two local boys had arrived with a boat and hung out with them. From the same night there were sightings of a man riding a motorcycle, who appeared to be stalking the women.

The murder had to have happened on the night between 27th and 28th, because in the morning of 28th the camping site was empty. Riitta had been murdered by hitting her on the head with something heavy, and Eine was brutally stabbed. The belongings of both of them were stolen and hidden. The murderer(s) had hidden their belongings carefully and some of them are still missing today. The murderer(s) also hid the bodies to a swamp that was 200 meters away from their camp, putting logs over the grave and also placing some sort of a tree branch on the grave so it wouldn’t be obvious that the ground had been disturbed.

The police were able to find their tent, sleeping bags, underwear, a watch etc. On 4th of September they found their bikes from the deepest part of Tulilahti lake.

Riitta and Eine were laid to rest in Jyväskylä. This case touched many people, so it is no surprise that thousands gathered for their funeral. Eine was carried by her fellow nursing students, and Riitta was carried by her close relatives.

Suspects

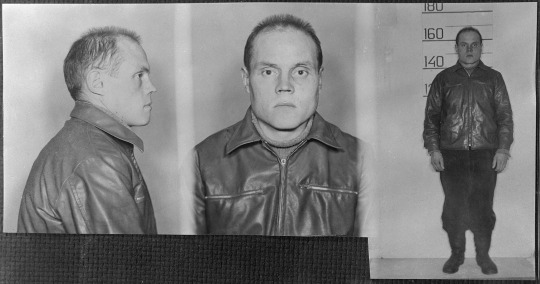

For this case there was one primary suspect whose life this case changed forever. Whether he did the murders or not, he remained guilty till the day he died.

Runar Holmström (1923 - 1961) was arrested on 6th of November when people suggested that the guy following the women with a motorcycle could be Holmström. The police found a knife from Holmström and considered it as an evidence, because they found out that the knife fit the cutting marks left on the branch that was left on top of the grave. Holmström was seen as a suspect also because he was acting nervously when the police took him to the murder scene. At first he confessed on travelling around Heinävesi, observing the girls companied by the two local boys and then continuing his journey to Varkaus. Afterwards he withdrew his confession. According to the police Holmström had told in his confession things he could not have known without being present in the camping site during the murders. They also found a pistol from Holmström that was loaded and the safety was off, although Holmström didn’t try to use it when resisting the arrest.

In this case there were also a lot of things pointing towards Holmström being innocent. He was right handed; the one who cut the branch for the grave were suspected to being left handed. Holmström also was small in stature and was only 164 cm (5,4) tall so the police thought it was impossible he was able to carry two bodies in rough roads to the swamp, bury and cover them well.

The shovel used in the burying had been fetched from a farm house nearby where usually a feisty dog hadn’t been barking. The police did a reconstruction where they managed to do the burying and hiding the belongings in the time the police suspected all had been done, but the problem was the police already knew what had been done and where. This led the police to think the murderer had to know the camping site area well. Holmström was from Ostrobothnia (region in western Finland), that was about 429,4 km away from Heinävesi (town in eastern Finland). This fact spoke for Holmström being innocent, but at the same time he was the only person who was seen as the only possible suspect. Later it was revealed that the prosecutor for this case, Viljo Laaksonen and the judge believed Holmström to be innocent.

In the spring of 1961 near Varkaus was found women’s underwear and two hats which were brought there during the same spring according to investigation. Holmström had already been behind bars for 1,5 years so this also pointed to him being innocent. The hats and underwear weren’t faded in color so it was impossible they had been in nature over the winter.

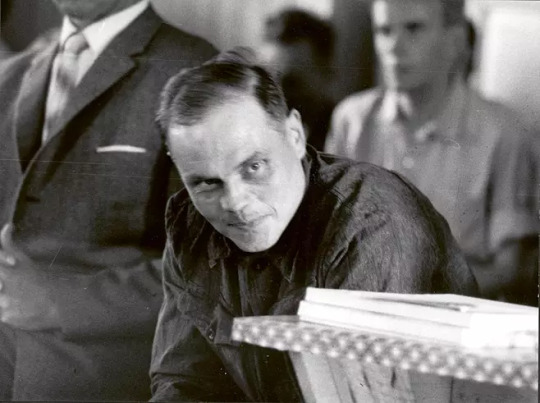

The Trial

The trial in Heinävesi was a public happening. It started on 8th of June 1960 in Hasumäki school, three days after the murders in the lake Bodom. During the trial (that lasted over a year) Holmström hanged himself in his cell with a rope he made from sheets on 8th of May 1961. He had tried to kill himself two times before the last one, first time leaving behind a note stating “I am innocent”. That time he had tried to kill himself with barbiturate that had been prescribed for him because of insomnia.

The second time Holmström’s brother had sent him the Bible containing 2,266 grams of codeine. The codeine was found before the Bible was given to Holmström.

The suicide wasn’t really a surprise. At that time everyone in prison were afraid they would be sent to forced labor which had a reputation of workers being “buried alive”. (Possibly just describing the horrible working conditions the prisoners were put in; “working themselves to death.)

Hans Assman

One other person seen as a possible suspect is German-born immigrant Hans Assman (1923 - 1998), who was also the suspect for the murders at the lake Bodom. He has never been an official suspect, but former detective inspector and a editor-in-chief of Alibi (Finnish crime magazine) Matti Paloaro and doctor of medicine and surgery Jorma Palo have suggested in their books him possibly being the murderer.

There were multiple eye witnesses for two men speaking German visiting a kiosk in Punkaharju (close to Heinävesi), two days before the murders, and purchasing a map for the Tulilahti camping site. One of the men fitted the description of Assman. The men were travelling with Volkswagen passenger car. Assman’s wife told that Assman and his driver were in Heinävesi during the murders and that Assman had visited Heinävesi couple times before, also getting to know the area, including Tulilahti camping site.

There has been a lot of critique towards police work because when Holmström was found to possibly be the perpetrator, the police buried all other investigation routes, meaning they did not pay much attention to locals living in Heinävesi who very possibly could’ve been the perpetrators. They were so sure that Holmström was the murderer that they thought they don’t need to investigate other people further. After the death of Holmström, the police also considered this case to be solved that has gained a lot of critique in public. After all these years however this case remains officially unsolved and the police are still accepting tips for it.

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

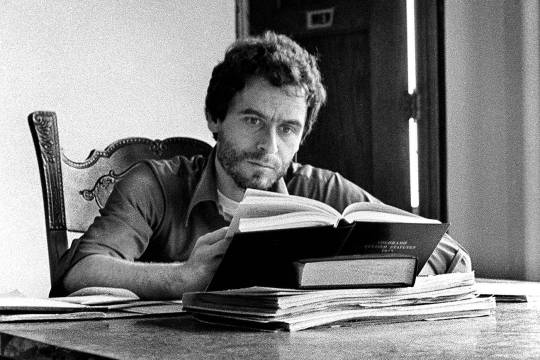

Ted Bundy's Murder Timeline

February 1974

Bundy abducted Lynda Ann Healy, 21, from the University District of Seattle, where the main campus of the University of Washington is located. She was known in the community for giving the weekday ski report on the radio. He abducted and strangled her.

March 1974

Bundy kidnapped and murdered Donna Gail Manson, 19, a student at Evergreen State College in Olympia. Her body was never recovered.

April 1974

Bundy abducted and killed Susan Elaine Rancourt, 18, a student at Central Washington University in Ellensburg.

May 1974

Bundy abducted Roberta “Kathy” Parks, 20, from Oregon State University around 11 p.m. He claimed to have raped and killed her at Taylor Mountain, more than 25 miles southeast of Seattle.

June 1, 1974

Bundy abducted Brenda Carol Ball, 22, in the town of Burien, south of Seattle. Her skull was later found at Taylor Mountain.

June 11, 1974

Bundy kidnapped and killed 18-year-old Georgeann Hawkins from the University District of Seattle. In an interview with King County Sheriff's Office Detective Robert Keppel, he claimed to have knocked her unconscious and strangled her.

July 1974

On a beautiful summer day at the popular Lake Sammamish, Bundy abducted Janice Anne Ott, 23, and Denise Naslund, 19. Witnesses described a handsome young man who called himself "Ted." Police were beginning to identify Bundy’s strategy of luring women by wearing his arm in a sling and asking for help.

September 1974

A grouse hunter discovered the remains of Ott, Naslund and Hawkins, one mile east of an old railroad trestle just outside Issaquah, Washington. According to Keppel the site was a “multi-use environment” for Bundy.

Oct. 18, 1974

Bundy abducted, raped and strangled Melissa Smith, 17, from Midvale, Utah. Her body was discovered just over a week later.

Oct. 31, 1974

Bundy kidnapped, raped and murdered Laura Ann Aime, 17, from Lehi, Utah. Her remains were found that Thanksgiving Day in a mountainous area.

November 8, 1974

Bundy attempted to abduct Carol DaRonch, 18, at the Fashion Place Mall in Murray, Utah. He posed as a police officer.

At 10:15 p.m. that same day, Debra Jean Kent’s father gave her the keys to the car to pick up her brothers from a roller skating rink. She never got to her parents’ car. She was 17. Bundy claimed in an interview with Salt Lake County Sheriff's Detective Dennis Couch that he left her body in a grave, but her body has never been found.

January 1975

Bundy abducted Caryn Eileen Campbell, 23, from the Wildwood Inn in Snowmass, Colorado. Thirty-six days later, her body was discovered three miles from the inn with evidence of blows to her head.

March 1, 1975

While Bundy was in Salt Lake City, Utah, the remains of Healy, Rancourt, Parks and Ball were found on Taylor Mountain in Washington. Their skeletal remains showed they suffered severe blunt force trauma.

March 15, 1975

Bundy abducted and killed ski instructor Julie Cunningham, 26, from Vail, Colorado. Her body was never found.

April 1975

Bundy killed Denise Lynn Oliverson, 24, from Grand Junction, Colorado. He said he left her body in the Colorado River and it has never been recovered.

May 1975

Bundy kidnapped and drowned Lynette Dawn Culver, 12, in a bathtub, then later said he discarded her body in the Snake River. Her remains have never been found.

June 1975

Bundy kidnapped and killed Susan Curtis, 15, when she was attending the Bountiful Orchard Youth Conference at Brigham Young University. Bundy claimed he buried her body near a highway, but her remains have never been located.

August 16, 1975

At 2:30 a.m., Bundy was arrested for the first time in Granger, Utah, after a chase by high way patrol officer Bob Hayward. Police found masks, gloves, rope, a crowbar and handcuffs in his car. He was released on bail the next day.

October 1975

Bundy was identified in a line-up by Carol DaRonch, whom he tried to abduct in November 1974.

Carol DaRonch testifies at a pre-sentencing hearing for convicted murderer Ted Bundy as Judge Edward Cowart looks on in Miami, July. 28, 1979.AP

Bundy was arrested and charged with the aggravated kidnapping and attempted criminal assault of DaRonch. He was held in Salt Lake County Jail.

February 1976

Bundy’s trial began. He waived his right to a jury trial. On March 1, he was found guilty of aggravated kidnapping. He was sentenced to a minimum of one to a maximum of 15 years in a Utah state prison.

October 1976

Bundy was charged with Caryn Campbell's murder.

January 1977

Bundy was moved to Aspen, Colorado, to face charges for Campbell’s 1975 murder.

May 1977

Bundy pleaded not guilty to Campbell’s murder.

June 1977

Bundy assisted in his own defense in the case, and was allowed to access the Pitkin County jailhouse law library. He escaped from the second story window of the library, 25 feet above the ground. He was captured five days later, after spending that time in the nearby mountains and back in Aspen. He went back into custody at a facility in Glenwood Springs, Colorado. On June 15, 1977 he was charged with escape, burglary and felony theft.

On June 7, 1977, Ted Bundy jumped from the second-story window of the Pitkin County Courthouse, seen here in this recent photo, and ran straight for the mountains.ABC News

December 1977

Bundy escaped from his jail cell through a light fixture opening in the ceiling. He stored books and other belongings on his bed below a blanket to appear as if he were in bed sleeping.

This 1977 file photo shows the jail cell from which serial killer Ted Bundy escaped on Dec. 30, 1977, in Glenwood Springs, Colo.Ross Dolan/Glenwood Springs Post-Independent via AP

January 1978

After flying to Chicago, then taking a train to Ann Arbor, Michigan, and driving a stolen car to Atlanta, Bundy arrived in Tallahassee, Florida, by bus. He signed a rental agreement at a building called “The Oaks.”

Jan. 15, 1978

At 3 a.m., Bundy entered the Chi Omega sorority house near Florida State University and killed Margaret Bowman and Lisa Levy. They were both beaten severely and strangled to death.

Chi Omega Sorority members Lisa Levy, 20, and Margaret Bowman, 21, were killed by Ted Bundy at Florida State University, Jan. 15, 1978.Bettmann via Getty Images

Karen Ann Chandler and Kathy Kleiner suffered severe injuries after Bundy bludgeoned them while they slept, but survived.

Kathy Kleiner was a member of Chi Omega and living in the sorority's house in Tallahassee, Florida, when Ted Bundy entered the house on Jan. 15, 1978. He attacked Kleiner and three others, killing two women.ABC News

Shortly after the Chi Omega attacks, Bundy broke into the apartment of Cheryl Thomas, a student at FSU, and attacked her. Her housemates who lived on the other side of the wall, Debbie Ciccarelli and Nancy Young, heard the noise and called Thomas’ apartment, but she didn’t answer. Ciccarelli and Young then called police. Bundy escaped before authorities arrived. Thomas survived the attack.

Cheryl Thomas was attacked in her home, blocks from the Chi Omega sorority house. A neighbor called 911 after hearing pounding and Thomas? whimpering.ABC News

Feb. 9, 1978

Bundy kidnapped and murdered 12-year-old Kimberly Leach. She was a junior high school student who disappeared in the middle of the school day. Leach was one of Bundy’s youngest victims. It was his last murder.

Kimberly Dianne Leach was 12 when she was abducted and murdered by Ted Bundy in 1978.Lisa Little, Ruby Bedenbaugh and Sheri McKinley

Feb. 15, 1978

At 1:34 a.m. David Lee, a patrolman with the Pensacola Police Department, noticed a suspicious car loitering and driving erratically. The officer ran the plates and discovered the car was stolen. Bundy refused to give his name and resisted arrest. The officer was able to subdue Bundy after a struggle and arrested him.

Back at the police station, Bundy gave officers a stolen ID and said he was an FSU student named Kenneth.

Feb. 17, 1978

Bundy reveals his true identity to police officers.

April 1978

Kimberly Leach’s body was found near Suwannee River State Park.

July 1978

Bundy was indicted for the murders of Margaret Bowman and Lisa Levy and the attempted murders of Cheryl Thomas, Kathy Kleiner and Karen Chandler.

Florida State University student Margaret Bowman, one of Ted Bundy's murder victims, is shown in an undated photo.AP

May 1979

Bundy rejected a plea deal that would have allowed him to avoid the death penalty if he admitted to murdering Bowman, Levy and Leach.

July 24, 1979

Bundy was found guilty of murdering Levy and Bowman and attempted murders of Kleiner, Chandler and Thomas. One week later, he was sentenced to death for the murders.

Kimberly Leach, 12, was a victim of serial killer Ted Bundy.Acey Harper/LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images

Feb. 1980

Bundy was found guilty of Leach’s kidnapping and murder and was sentenced to death.

July 1986

After Florida Gov. Bob Graham signed two death warrants for the Chi Omega case, the 11th Circuit Court signed a permanent stay of execution fifteen minutes before Bundy was scheduled to be executed.

Jan. 17, 1989

Gov. Bob Martinez signed the second death warrant in the Leach case.

Jan. 21, 1989

Over the next several days, Bundy confessed to various law enforcement agents. Bundy told FBI Special Agent Bill Hagmaier he killed 30 people in California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Utah, Colorado, and Florida between 1973 and 1978.

Jan. 24, 1989

Around 7 a.m., he was strapped into the electric chair. He was later pronounced dead.

#Ted bundy#Tcc#True crime#True crime community#Dylan klebold#Eric harris#Columbine#Murder#Murder case#Serial killers#Serial killer#Killer#Murderer

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The fantasy of a woman exhibiting and disciplining another woman’s body attained its most spectacular form not in the visual images but in the printed pages of England’s leading fashion magazine. In 1868, almost every fashion plate in the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine included a girl alongside two adult women, and that same year a debate raged in letters to the editor about whether parents, especially mothers, should use corporal punishment to discipline children, particularly girls past puberty. The fashion plate’s image of the quietly contained, fashionable girl who worships her female elders became a story of unruly daughters and stern mothers. The fashion image’s obsession with dressing and covering the body became the reader’s drive to expose it; the proud mien of the plate’s figures mutated into narratives of humiliation and shame.

Only one element remained constant from image to text: the world in which both rituals were staged was dominated by female actors and objects. “I put out my hands, which she fastened together with a cord by the wrists. Then making me lie down across the foot of the bed, face downwards, she very quietly and deliberately, putting her left hand around my waist, gave me a shower of smart slaps with her open right hand. . . . [R]aising the birch, I could hear it whiz in the air, and oh, how terrible it felt as it came down, and as its repeated strokes came swish, swish, swish on me!” This description of a girl being birched by a woman first appeared in an 1870 supplement to the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine that extended a debate about corporal punishment raging in the journal since 1867.

Editor Samuel Beeton justified publishing the monthly supplements, each consisting of eight large, double-columned pages of small type, by citing the overwhelming volume of letters received on a topic “which, of late years,” had “aroused . . . intense, not to say passionate interest.” Beeton priced the supplement at two shillings and made it available by post, thus guaranteeing its accessibility to middle-class readers. Like the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, a respectable family publication that advertised in the pages of Cobbin’s Illustrated Family Bible, the supplement presumed an audience of housewives who would be drawn to its advertisements for Beeton’s Book of Home Pets and The Mother’s Thorough Resource Book.

The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, as its title announced, was aimed at the middle-class women whose homes defined the nation. By the 1860s, the thirty-two-page monthly cost sixpence and reached roughly 50,000 readers per issue. With two color fashion plates in each issue, a republican editor who supported women’s employment and suffrage, and articles on “The Englishwoman in London,” “Great Men and Their Mothers,” and “Can We Live on £300 a Year?” the journal combined fashion, feminism, and thrift. Fashion magazines had always had heterogeneous content—astronomer Mary Somerville first encountered algebra while reading “an illustrated Magazine of Fashion”—and the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine prided itself on being learned and political as well as practical and stylish.

The magazine had both women and men on its staff, and Isabella Beeton codirected it with her husband until her death in 1865, soon after she completed a best-selling opus on household management. The publication of correspondence revealing women’s preoccupation with corporal punishment and its overlap with pornography might surprise us today, but only because we erroneously assume that Victorians imagined women and girls to be asexual unless responding to male initiative. Victorians themselves did not set such limits on female desire, and many found the letters on corporal punishment published in the eminently respectable Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine provocative, with their use of onomatopoeia, teasing delay, first-person testimony, and punning humor, all typical of Victorian pornography.

A letter from “A Happy Mother,” published in 1869, explained that the author put cream on her children before whipping them, so that punishing them produced whipped cream: “I scream—ice cream.” Some readers denounced the correspondence as indelicate and indecent, warning that it might arouse male readers, and accusing women who flogged children of improper motives. In the 1870 supplement, a “mother” worried about how a gentlemen might respond to finding an otherwise “useful” publication marred by “immodest” descriptions of punishments by “ladies.” One letter fulminated against “people who take pleasure in giving . . . exact details of the degrading way in which they punish their children.”

A correspondent signing “A Mother Loved By Her Children” condemned “the indelicacy in which every disgusting detail is dwelt on” by a woman who described a punishment she had received from another woman. “A Lady” protested “the offence to decency and propriety in publishing vulgar details” about “the removal of clothes and ‘bare persons.’” Readers who protested the indecency of the letters recognized that reading about punishment could provoke sexual sensations in both men and women. The voluminous correspondence began as a short query in 1867: “A Young Mother would like a few hints—the result of experience—on the early education and discipline of children.” The first two published responses opposed whipping, arguing that mothers who resorted to physical punishment would lose the self-control needed to discipline children properly.

Though Beeton himself opposed corporal punishment, he published many letters in favor of it. The debate quickly became more specific: whether it was proper for adult women to punish girls, especially those past puberty, by whipping them on the “bare person.” Whether writing for or against corporal punishment, correspondents provided detailed accounts of inflicting, receiving, and witnessing ritual chastisements in which older women restrained, undressed, and whipped younger ones. Letters described mothers, aunts, teachers, and female servants forcing girls and young women to remove their drawers, tying girls to pieces of furniture, pinning back their arms, placing them in handcuffs, or requiring them to count the number of strokes administered.

…Corporal punishment is where pornography, usually considered a masculine affair, intersects with fashion magazines targeted at women. Both types of publications were mass-produced commodities that created an aura of luxury, and both depended on the relative democratization inherent in an economy organized around consumption and leisure. Pornographic publications and monthly women’s journals had similar formats: both combined short stories, poems, historical essays, serial fiction, current events, and letters to the editor; both featured detachable color prints that could be sold separately; and both released special Christmas issues. Their common interest in corporal punishment led to even more concrete links between pornography and fashion magazines.

John Camden Hotten, the publisher of many pornographic works, advertised a pseudoscientific study of Flagellation and the Flagellants in the supplement to the Englishwomen’s Domestic Magazine. Other pornographic publications actually reprinted verbatim material first published in fashion magazines. In his exhaustive bibliography of pornography, Henry Spencer Ashbee mentioned the “remarkable and lengthened correspondence” about flagellation in “domestic periodicals” alongside his discussion of flagellation in “bawdy book[s]” such as Venus School-Mistress and Boarding-School Bumbrusher; or, the Distresses of Laura. The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine was more available to women readers than pornography, but Victorian pornography was not the exclusively male province it is often assumed to be.

Like the fashion press, pornographic literature expanded during the middle decades of the nineteenth century; between 1834 and 1880, the Vice Society confiscated 385,000 prints and photographs, 80,000 books and pamphlets, and 28,000 sheets of obscene songs and circulars. Who wrote and read pornography remains a mystery: publishers falsified dates and places of publication; authors wrote under pseudonyms; and individuals left few public traces of their purchases and reading experiences. The scant evidence we have suggests that pornography was a predominantly but not entirely male domain.

Newspapers reported women publishing and selling obscene books and texts; one woman has been documented as the author of a French pornographic novel that circulated in England; and women of all classes frequented the Holywell Street area where obscene books and prints were sold and often visible in shop windows. After publisher and bookseller George Cannon died in 1854, his wife ran the business for ten more years; in 1830 a police officer testified that Cannon hired women who “went about to . . . boarding schools . . . for the purpose of selling” obscene books, “and if they could not sell them to the young ladies, they threw them over the garden walls, so that they might get them.”

Women did not have to purchase pornography directly to read it, however, since they might easily find any sexually explicit books that male family members brought home. Women did not need to turn to pornography to encounter sexually arousing descriptions of older women disciplining younger girls; they could read material in the pages of a ladies’ home journal that would be reprinted as pornography. The correspondence about corporal punishment blurred distinctions not only between pornography and the women’s press but between male and female readers. Some worried that the magazine had become so obscene that it needed to be hidden from both; Olivia Brook wrote in 1870 that she now put the magazine “out of reach of any casual observer, and where especially no gentlemen can read it.”

…In The Other Victorians, Steven Marcus influentially argued that all pornographic accounts of whipping, even those that represent women birching or being birched, were nothing but displaced versions of repressed fantasies about father-son sex. That interpretation assumes that erotic desire between women was irrelevant to Victorian society, and that sex between men or family members was impossible to represent directly. In fact, the only impulse Victorian pornography repressed was repression itself. Victorian pornographers represented same-sex acts of all kinds and freely indulged their obsession with incest, including sex between fathers and sons.

…Victorian pornography helps to explain how the family could simultaneously be organized around sexual difference and be a site of homoerotic desire, for in it the family is a hotbed of sex, but same-sex acts do not imply fixed sexual identities. Representations of sex between men and sex between women were never confined to specialized publications. Sex between women was regularly featured in pornographic texts and in images that depicted two or more women engaging in tribadism, oral sex, anal sex, digital penetration, mutual masturbation, and sex with dildos. Flagellation literature described women achieving orgasm from punishing girls and penetrating girls with fingers and dildos while birching them.

…The convergence of pornography and women’s magazines on the topic of flagellation points to their common origins in nineteenth-century liberal democracy, which promoted the free circulation of ideas among individuals who could demonstrate self-control and tasteful judgment. Pornography had affinities with Enlightenment and utilitarian ideals regarding the empirical investigation of nature and quests for knowledge, increased well-being, and merit-based rewards. Fashion was a feminized version of liberal democracy, for it depended on a woman’s ability to train her taste and accommodate her individual style to fluctuating group rules.

By following fashion codes, women learned to fit their bodies into a social mold; by improvising on those codes, as fashion itself demanded, women developed the kind of restricted autonomy associated with liberal subjectivity. As Mary Haweis explained in The Art of Beauty (1878), clothing was a form of individual aesthetic expression and therefore had to follow “the fundamental principle of art . . . that people may do as they like.” The liberty underlying the art of dress also upheld of liberalism’s ideal of personal freedom as a source of originality and political renewal. The correspondence columns of fashion magazines allowed women to participate in the public discourse central to liberal politics.”

- Sharon Marcus, “Dressing Up and Dressing Down The Feminine Plaything.” in Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The circumstances surrounding Breonna Taylor’s killing by police in Louisville, Kentucky, are by now well known. When plainclothes officers executed a no-knock warrant at the medical technician’s apartment in March, her boyfriend fired at the police, thinking they were intruders, and three officers returned fire, killing Taylor.

These facts were enough to help spark the ongoing wave of protests for racial justice, but earlier this month, lawyers for the Taylor family made troubling new claims about the context of the police raid.