#and despite the med shortage I’m feeling more like myself than ever

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

In arts and crafts news I went through a gallon of epoxy resin this week, so I guess the next bit is finally buying one of those 5-sided photography light boxes for taking pictures of all the things so I can sell them. I really wish Etsy was a psychic affair and I could just think about it and someone else could just think about it and then the items just show up in someone’s house, but given the restraints of the physical world, FINE, I’ll do the small business things so I’m not filling up my home with beautiful things, because there IS a point at which you have too many cute trinket dishes.

#reluctantly doing small business because i can’t justify all the things I’ve made otherwise#resin craft#creation IS the point#that and love#what am I even talking about#yo I’ve been out of adhd meds for over a week so I’m not hanging onto the thoughts particularly well lol#but i do know I’m making things and want to make more things#and despite the med shortage I’m feeling more like myself than ever#and that friends is a fucking W and a half#cosmic art#cosmic thoughts

1 note

·

View note

Text

s/p first year as a PA

I was hired as a hospitalist primarily for the transplant service. However, in the setting of the pandemic and staffing shortages, I am all over the place now and work in almost everything non-pediatric and non-surgical.

In my first few months as a PA, I was incredibly overwhelmed. I went from being a learner who switches specialties every month to a fully-fledged provider making life-or-death decisions on an hourly basis. Oftentimes I’d find myself in the room of a patient actively crumping, surrounded by the patient’s family and multiple nurses awaiting instructions on what to do to save the patient. I thought that I faced a lot of pressure in school, but it was nothing compared to this.

And just when I started to get a hang of it all, the pandemic hit. What a nightmare. As mentioned above, I was hired to work with with transplant patients. Prior to the pandemic, my transplant colleagues and I were masking and gowning for almost every patient: 1 surgical mask and 1 gown per patient and per patient encounter. But once COVID hit, we were rationing PPE. 1 N95, 1 pair of goggles, and 1 face shield for the pandemic. 1 surgical mask per week, and 1 gown only if a patient had Cdiff or a history of MDRO bacteremia.

What did the pandemic mean for our transplant patients?

Our patients are on immunosuppressant medications to prevent transplant rejection. Unfortunately, this makes it difficult for them to fight infections.

Our department did what it could to prevent COVID. We'd test patients on admission for COVID, regardless of symptoms or exposure history. If they were positive, they went to the COVID team and quarantined on their unit for a period of time and had to test negative before returning to our unit and being transplanted. We took many other measures to reduce COVID risk to the best of our ability.

People still died. To see someone get transplanted successfully and then die of a virus is horrifying. Unfortunately, despite our admission tests, sometimes patients contracted COVID within the hospital. Patients would be happily FaceTiming their family one moment, telling them all of their plans for once they were discharged- then the next day they'd be intubated. We tried Remdesivir, Dexamethasone, prone positioning, etc. But the virus moved through them quickly, and these efforts often were too late. No amount of hoping and praying brought them back.

As a first year PA, I learned to go to an empty conference room, close the door, and remove my mask before calling to the family of the deceased. This way, as they gathered around the phone in their homes, the family could hear me unmuffled as I delivered the news. Also, this way my tears didn't ruin my mask for the rest of the week.

I learned a lot this year. It's been a mixture of crying and laughing. There are times that I question why I ever became a PA, and then there are times when this career feels like home. In addition to transplant, I’ve also been working in the ED, IMC, ICU, inpatient hospice, clinic, and infusion center these past 6 months. I’ve learned quite a lot along the way.

Lessons learned as a first year PA:

1. Check your pager hourly: This is in addition to checking it whenever you get paged. Sometimes I’ll get paged while I’m rounding, read it, and then forget about it. Now I go through my pager at every hour to ensure that I already responded to all my pages and then answer ones that I missed/forgot. On a semi-related note, a while back I wrote about good paging etiquette.

2. Let people know when you're out: I work a rotating schedule. As a result, it’s hard to predict when I’m in or out of the hospital. Sometimes I’ll come back on service and find urgent emails or texts that are a few days old. Now I leave an away message with my return date and my supervisor’s contact information on both email and hospital text. If someone really needs to get a hold of me, my supervisor has my personal cell phone number.

3. Be conscientious of what time you consult: I generally try to get all of my nonurgent consults done before 3pm. Many services have only 1 resident covering after 3pm, so I try not to page/call unless I have an emergency.

4. Call the nurse if something needs to be done urgently: Being a nurse means being the ultimate multitasker. Room 5 is due for his IV Amphotericin, Room 2's Foley is supposed to come out prior to void trial with Urology, Room 1's infusion completed and is beeping, and Room 4 is a bit altered and yanked out her PICC. Now I’m placing an order for Room 3 to get IV Lasix due to concern for pulmonary edema. However, the nurse may be preoccupied with Room 4 and not see the order in the computer for some time. If I really need to the patient to get the Lasix right way, I’ll place the order through EMR and then call the nurse and see what their situation is. If they’re crazy busy with Room 4 and likely to be unable to get to the Lasix within the next 15min, I ask whether they’re okay with me asking another nurse to give the Lasix now. Usually the answer is yes.

5. Value your nurses: Nurses know the patient best. They’re the ones answering call bells, giving meds, doing dressing changes, etc. Unfortunately they oftentimes bear the brunt of everyone’s frustrations, from patients to patients’ families to attendings to managers. Not to mention, they’re the ones doing the dirty work. Bedside nurses are the heartbeat of healthcare, but they also are high risk for burnout. Always support your nurses, whether that’s volunteering to answer a patient’s family member’s 17th phone call of the day or responding to a patient’s call bell yourself.

6. Know how to get a hold of someone quickly: It’s less than ideal to page someone repeatedly. At my hospital, if I need to talk to an attending urgently, I call the operator and ask them to connect me directly to the attending’s cell phone. If a patient is crashing and we’re not in the ICU, I dial the emergency number and call a rapid response, which sends people running into my patient’s room.

7. Plan your discharge meds from Day 1: The goal of every admission is to treat the patient and then discharge them safely. Send medications early for prior auth and call the pharmacy to make sure that they have medications in stock. (One time a patient’s insurance didn’t cover Levofloxacin, of all things.)

8. Keep social work and care coordination aware of all needs from the start: Does your patient looks unsteady? Place a PT/OT consult and let social work and care coordination know that the patient might require home therapy services and/or DME so that they can start looking at services and companies that may be covered by insurance. Does your patient have a central line? They’ll likely need a home health service to teach them how to care for it daily at home. Do they seem to require frequent transfusions? They’ll probably need labs on discharge. Is the patient’s living situation safe (no heat/AC, possible abuse at home, financial difficulties, etc)? They may need alternative housing.

9. The attending is not always right: Generally speaking, the attending has the last say on how the team manages a patient. However, I’ve come across situations in which an attending’s decision put a patient in more danger. Sometimes asking them about their decision can help steer the care plan toward better patient care. Other times you just have to stand your ground and be okay with being on the receiving end of an attending’s misdirected rant. Report these instances to your manager and to other higher-ups.

10. Always have gloves in your pocket: You never know when you’ll find a mess. Or which part of the body someone asks you to examine. Or how hygienic a person is (or is not).

11. Verify weird vitals: I was very new when I walked into work, opened a patient’s chart, and promptly bolted down the hallway when I saw a patient’s O2 sats recorded as 15-20s. I found the patient sitting up in bed, eating breakfast, and bewildered by me bursting into the room. Turns out that overnight someone mistakenly recorded his respirations as the O2 sats.

12. Remove whatever tubes you can: Anything entering the body is an infection risk. Does your patient still need that Foley placed by the surgery team? No? Yank it (don’t actually yank because ouch). Is your patient A&O and able to eat without aspirating? Remove the NG tube. Does your patient have good veins and require infrequent transfusions/labwork? Pull their central line.

13. Take a buddy with you to emergencies: Two heads are better than one. Even if you’re a seasoned provider and well-equipped to manage an emergency, you might need another body to help with performing CPR, making urgent calls, grabbing supplies, etc.

14. Ask your patients about premeds for procedures: We all have different levels of pain tolerance. A procedure goes far more smoothly if your patient is comfortable. Note: if you’re going to premed with Ativan or an opiate in the outpatient setting, make sure they have a driver.

15. Be good to your charge nurse and unit secretary: I don’t know how they do it. If I had to manage the unit’s signout, patient complaints, calls from other floor, being yelled at by providers, verifying paper orders, and finding beds for incoming patients- all at the same time - I’d lose my mind.

16. If your patient is mad, just shut up and listen: There are many things that you can’t control: the time it takes for a patient to get a room, the temperature of hospital food, the dismissive attitude of your attending, etc. And oftentimes the patient knows this. My reflex is to want to apologize for things and overexplain why different things are happening. But sometimes the patient just needs to rant. Take a step back and just listen. That can make all the difference.

17. Fact check your notes: The framework for your progress note often is the note from the day prior. It sounds obvious, but make sure that you go through the note and make updates and changes accordingly. If today is 01/15, there’s a good chance that the Fungitell from 12/31 is not still pending.

18. Try to learn some nursing skills: This is one of the areas in which I most envy my NP colleagues. If a patient’s IV pump is beeping or their central line need to be flushed, I oftentimes awkwardly step out of the room and look vacantly into the distance for a nurse. I’ve finally figured out how to spike a bag (albeit I do so very slowly, and it certainly makes the RNs giggle some). I talked to our unit’s nurse manager, and she’s willing for me to learn some nursing skills from the staff during a slow day- we’ll see when thing slow down!

19. Be kind: Generally speaking, being in a hospital is stressful. Patients are feeling out of sorts, and staff are working with constant dinging in the background. I rant plenty on this website, but I’m kind to everyone at work (with few exceptions) because it makes things more comfortable for everyone. Additionally, if you are always kind to your patients and colleagues, your reputation will speak for itself. One time I was walking down a hall with poor reception while on my ASCOM with a notoriously standoffish nurse from another unit. My phone cut out. She called my unit’s nurse manager to complain, and the nurse manager told her that I would never hang up on purpose. My interactions with the nurse going forward were always more pleasant in nature.

20. Support your team: The best colleagues are not the smartest colleagues; the best coworkers are the ones who have your back. Whether it’s a medical emergency or just a strange situation, it’s important to be supported and to give support.

I know that I’ve learned a lot more than this, so I’ll likely be adding to this throughout the year. Happy Snow Day, all!

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life on Intermission

So, for mental health reasons, I have decided to put my law studies on hold for six months while I gather myself. The thing I am supposed to be mostly doing is resting (which is the hardest thing in the world for me - I always need something to do). I think the main reason why it is difficult is because for the majority of my life I have had too much cortisol running through my body. When I was a kid (and teenager), I grew up in a tumultuous household with a narcissistic mother and an enabler for a father. I had to parent and counsel my mother day and night for her unresolved issues surrounding her own traumatic upbringing and stressful early life, which led to a transference of generational trauma from herself to me. I was both psychologically, (and one time) sexually abused by her. Adding to this, there was a constant money shortage, sometimes to the point of relying on food stamps, and I was bullied terribly at school. At 16 years of age, I was raped by a guy who had been my boyfriend of 3 months, and unceremoniously dumped shortly afterwards. I had to see him every day at school for the rest of my time there. The loneliness I felt, with both what was going on at home and what was going on at school, led me to try to take my own life with pills, but obviously, this was unsuccessful, because my parents came home early and I was rushed to the hospital unconscious and had my stomach pumped. My mother refused me a counselor and medication, so my depression (which was later diagnosed as Bipolar I) just got worse. and unceremoniously dumped shortly afterwards. I had to see him every day at school for the rest of my time there. The loneliness I felt, with both what was going on at home and what was going on at school, led me to try to take my own life with pills, but obviously, this was unsuccessful, because my parents came home early and I was rushed to the hospital unconscious and had my stomach pumped. My mother refused me a counselor and medication, so my depression (which was later diagnosed as Bipolar I) just got worse. and unceremoniously dumped shortly afterwards. I had to see him every day at school for the rest of my time there. The loneliness I felt, with both what was going on at home and what was going on at school, led me to try to take my own life with pills, but obviously, this was unsuccessful, because my parents came home early and I was rushed to the hospital unconscious and had my stomach pumped. My mother refused me a counselor and medication, so my depression (which was later diagnosed as Bipolar I) just got worse. because my parents came home early and I was rushed to the hospital unconscious and had my stomach pumped. My mother refused me a counselor and medication, so my depression (which was later diagnosed as Bipolar I) just got worse. because my parents came home early and I was rushed to the hospital unconscious and had my stomach pumped. My mother refused me a counselor and medication, so my depression (which was later diagnosed as Bipolar I) just got worse.

I graduated from school with a relatively good result, and thus was able to gain entry into the university program of my choice. Or rather, it was my parent's choice. I had won a few poetry competitions which had been published in some anthologies. I wanted to study creative writing, but my parents thought it would be better I learned something "more stable" (which is ironic), so I "decided" to study psychology, my third choice. Regardless, I thought this would be a way to start over, and leave the horrors of high school behind me. But because of my family's lack of money, it was impossible to move out on just the income I was getting from the casual job I had whilst supporting myself at university. And then, along came my first love, who I had a tumultuous relationship with. We were on again, off again for many months, in fact, many years. We first met in 2003, and parted ways for the last time at the beginning of 2006. In hindsight, I think he loved me, but just couldn't say it. At the time though, it was devastating. I moved states and universities to get away from the situation, first to Canberra (but I have followed me there), and then to Brisbane (but I have kind of followed me there too).

I was able to make a life for myself in Brisbane for a time, despite still living with my parents (who had followed me up there), but then the loneliness I felt, mixed with being given the wrong meds, led to my first full -blown manic episode. I was spending money I didn't have, and wracking up a debt on 3 credit cards and 2 personal loans. In 2005, I tried to take my life again, which (again) was unsuccessful. Towards the tail end of this spending spree, I met my future husband. This was a brief reprieve. I decided to take a year off uni and work full-time to pay my debt back, and my future husband and I moved in together. Within 7 months, I was pregnant with our first son, and, even though I went back to university, I kept having to defer because of money issues. After giving birth, I went though a pretty bad bout of postpartum depression,

In 2010, we got married, and things went well for a couple of months, until the financial situation became critical. We decided to move back to Norway, my husband's home country, despite me never even visiting, as he could get a better job there. I graduated with just one half of my double-degree, and off we went. Initially, things were good when we moved; I worked toward my master, learned the language, got a few jobs which allowed me to focus on practicing the language, and was of the impression that I would be able to study psychology in Bergen once I finished my language courses. But then, in 2012, I found out that I had been given the wrong information about this, and it was no longer an option. I wanted to leave, as there were no jobs available in my specialized area. I was hospitalized for suicidal thoughts for the first time ever in 2012, but there would be another 3 times after that over my time in Norway. In 2013, I gave birth to my second son, which was truly a joy, and for which I didn't get any postpartum depression, but, at that time, my actual Bipolar was bad enough. My husband's career was taking off, and I felt my problems were ignored, and that he was leaving me behind. We didn't move back to Australia (my home country) until 2017. Again, there was another promise of a fresh start.

After working with my degree for a few months, I decided to do my PhD, which was awful (I covered that in a previous post). I loved teaching and participating in conducting research, though. With my income from these gigs, and my husband's income, we were living the high life. Until the teaching dried up and my husband's company folded at the beginning of 2019. The pressure of all of this led me to be hospitalized again in the psychiatric ward 2019 for 3 months. Afterwards, as soon as I came out, I had to look for work, due to our dire financial situation. We had been in the throes of building a new house when times were good, and now we were in more debt than we had ever been. My husband found work, but was now earning half of what he was earning before. I've applied for 600 jobs before I've got to his first job interview. I ended up getting casual work, but couldn't find anything permanent, and it didn't pay enough. I started my law degree, which got off to a prosperous start, but I was also diagnosed with Lupus, which would explain why I not only felt mentally shit, but also physically shit. And that takes my biography more or less up to the present (with some stuff most likely left out).

But now, I am taking a break. I am, for the first time, deciphering what happened to me, trying to process all of the trauma, in order to become a better version of myself. Here are just some of the things I am doing during this coronavirus lockdown to self-improve:

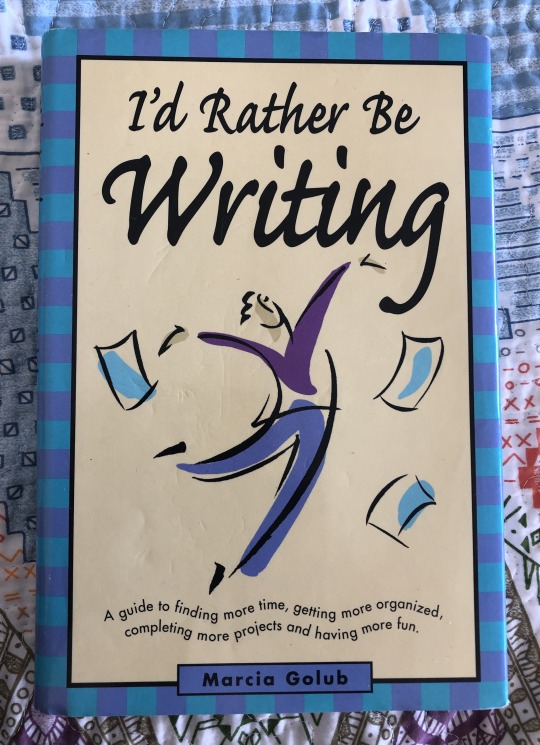

^ Here is book I need to read whilst in the throes of finally finishing my first novel. It's only taken me 13 years. Not biggie. I need to procrastinate less. But also be less harsh on myself. I've had some really dark periods in-between that have lasted years. Sometimes, I just feel like I lose so much time when the depression is particularly bad. It makes me overdo myself when I actually feel OK for once.

^ This is a picture of my jewelery projects and couch-side workroom for when I am on hiatus. I'm going to try to get my jewelry business in order during my time off, but it's all about moderation, as my jewelry-making sometimes becomes obsessive because I get a rush of ideas. For example, yesterday I made 3 necklaces and 4 bracelets in a trance-like state. It might be impending mania, and I have to try to keep track of it, and approach it in a healthy way.

^ My fitness and health has been a personal concern of mine for a while now. Due to being diagnosed with Lupus last year, the sedentary life of being a student, and having to take mood stabilizers and anti-psychotics for my Bipolar, I have put on a little bit of weight that I want to shed, but because of the physical pain I experience due to the flares, sometimes it's difficult to do anything but light exercise. It's all about baby steps. Daily walks are also good for boosting my mood.

There is also a number of boxes awaiting my attention in the garage, which I suppose could be seen as symbolic of me unloading both emotional and literal unwanted baggage / rubbish. Its a long road, but at least I am finally taking the necessary steps for dealing with unresolved trauma and ridding myself of painful secrets that have haunted me for the longest time. All I have to do now is to remind myself to breathe.

#trauma#childhood trauma#mental health#mental illness recovery#mental illness#bipolar i#just breathe#on hiatus#dealing with trauma#trauma recovery#just create#exercise#just write#be creative#live in the now#live in the moment#healing yourself#lockdown#coronavirus lockdown#creativityisrebellion

1 note

·

View note

Text

I just wanted to say that I’m proud of myself, because I definitely don’t tell myself that enough. I’ve been really tough on myself, hating myself for what I perceived as my flaws, feeling like I was not good enough.

I trained a new shift, the TPN shift, at work Mon-Wed last week, then have been staffing it solo ever since (I had my seventh solo TPN shift today.)

I had dosed TPN per Pharmacy throughout my internship and residency so felt very comfortable with writing adult PNs. But the TPN shift at my current job in a pediatric hospital is completely different. The major difference being that prior to my first day of training this shift, I had never written a pediatric PN before. And now I am clinically assessing (and in some cases, writing) PNs for patients who are 1 day old and born very prematurely to patients who are big teenagers. There were 43 patients on PN in our hospital today. This shift is responsible for verifying PNs and modifying orders, coordinating the compounding/checking/packaging/delivery of the PNs, answering the dedicated phone line for any provider with questions about PNs, troubleshooting any compounding issues that arose, managing the prepacking of lipids with this severe shortage going on, etc. Essentially making sure that all 43 PNs are clinically optimal and reach the patients. This is a demanding shift and I had been intimidated by how tough it seemed.

I studied a good amount for it in the weeks leading up to my training, in my hotel room while I was on vacation, on the plane back from vacation, trying to get some reading in in bed before sleeping. On my first day of training, it took me like an hour or maybe even more than an hour to assess one PN order. It was hard for me to fathom how I was supposed to reach that point where I was going to be able to staff solo. But I kept practicing and studying and by the end of the last day of training, I felt ready to take on my solo shifts. I had to stay overtime on a number of my solo days, and I couldn’t help but feel like a failure. I criticized myself for not being able to finish the workload by the scheduled end time of my shift.

Today, I actually got a lot of phone calls and messages from providers with questions and issues. I was able to answer them and provide my recommendations. That slowed me down a lot, but I also was still able to do the other work faster so that I reached the goal number of PNs to verify, despite a number of them being new patients and initiations. I also finished assessing the last order maybe around 4:45pm or so (when I was training I was finishing that around 6pm).

I didn’t treat myself the best these past two weeks. I’ve focused more on the work than taking any breaks. This morning before my alarm rang, I had already woken up out of anxiety 3 hours before I had to be at work and immediately went to my computer to check one of my patient’s labs out of fear that I might have made a mistake on dosing this 5-week-old infant’s PN. I was extremely relieved to see all of her labs were within normal limits, because I had been picturing the terrible things that could have happened if I had accidentally made a mistake. It’s been exhausting. But honestly, it feels like it was all worth it after how today went and I noticed that I’ve grown so much since training. What seemed daunting before became something that I could manage.

I had also trained and staffed other shifts, and I have been really negative and toxic to myself, focusing on things I didn’t know, ways I wasn’t good enough. But I wanted to take a moment for once to focus on my growth. I have an even more intimidating shift I’ll be training next week; I think what will make it tough is the patient and order load, the large number of med errors in the orders (many providers are learners), and all of the clinical question phone calls I’ll get. But I now believe that I CAN do it, like how I learned so much for this TPN shift. Not only can I do it, but the whole process and journey is SO rewarding precisely because I once struggled and then I got to a point when I realized I’m actually comfortable with the shift and can handle dilemmas the shift throws at me.

I spent my years as a student and resident building confidence in my clinical knowledge and skills, all for adult patients. I knew the answers and I felt competent (except for when the attending physician grilled me during my last rotation when I had had two hours of sleep the night before and didn’t get to study that topic ahead of time, but that’s a whole ‘nother story). Since I started working at a pediatric hospital last year, that confidence was replaced with... just feeling like I know so little. Pediatrics is a whole different world, so I feel like I’m starting from scratch again. I’m a student again learning everything for the first time, and I don’t like the feeling of insecurity in my lack of experience with pediatric patients. But I’ve also always sought being out of my comfort zone, so I feel very fulfilled too. I am learning so much, which is exactly what I wanted. I don’t like feeling like I don’t know the answers. I’m used to being comfortable with clinical shifts and answering drug info questions from providers. Now I need to continue to channel my discomfort of feeling inexperienced in pediatrics to studying hard and working really hard to become a better pediatric clinician. If I hate this feeling of lacking, then I’d better work harder. Again, I want to remind myself that how I did today is proof to myself that I am capable.

0 notes

Note

Hospital alarkling au! Yes!!!

omg, ok, here we go. this is like, half crack.

Alina blinked, fidgeted. Coughed into her white sleeve. Maybe he hadn’t heard her, maybe she should say it again – but his countenance, as brutally beautiful as it was, didn’t invite repetition. He stared down at her, unamused.

She’d thought the stories about him were overblown – no one with standing job offers around the world would choose to work at a teaching hospital and be that much of a misanthrope.

She had apparently been wrong.

When he did choose to respond, it wasn’t exactly the first words she’d hoped to hear from the doctor who would be her mentor for the next year. “You’re my intern.”

“Yup!” she replied, far too brightly.

He looked her over, his gaze traveling down the white coat she was so proud of and back up in quick dismissal. “Do you have any surgical experience?”

“Um, no, sir – er, doctor. I just graduated medical school, you know, last week.” She mentally chastised herself for her timidity and wished, not for the first time, that she had the same unreasonable self-confidence that all the other surgical interns seemed to.

Disbelief and dismay warred across his features. “And before that?”

If only the last conversation she’d had with her parents before they died had been about her being a dermatologist, or a professor, or a dog-walker – if only they’d told her to go into anything but surgery. But she’d busted her butt for years and here she finally was, intern to a surgeon who was a worldwide legend. Damn if she was going to let him get the better of her on her first day.

She snorted. “What, you think I spent my childhood cutting open my friends?”

She’d been expecting him to disavow the idea, but he just lifted an eyebrow in an expression she couldn’t read. It was uniquely disconcerting. “So I’m going to have to teach you everything.”

“Not everything,” she countered. “I did go to med school.”

“Did you.” His gaze sharpened to a scalpel’s edge and she got her first glimpse of the surgeon Morozova, ready to carve open a living subject. “Then let’s see what you know, shall we?”

*

“Dr. Starkov.”

Alina bent her head towards the linoleum floor, trying to stifle the smile that threatened to erupt across her features any time she was called that. She hadn’t quite gotten control of the grin by the time she turned around, but the steel gaze that met hers made quick work of the kill.

This seemed like a bad way to begin her second day.

“My office, please.” Dr. Morozova gestured to down the hallway. She marched ahead of him and entered, sitting in the chair in front of his desk as he sat behind it. He leaned back, elbows on his armrests and fingers steepled in front of his chest, and stared at her.

For a while. She could only return the look for a few seconds before diverting her eyes to the bookshelf behind him. The books were worn, each shelf bookended by bones hinged together with wire. It wasn’t unusual for a surgeon’s office to have skeletons interspersed with the decor, but there were significantly more bones in the room than she’d expected.

“Um,” she said, finally tired of looking anywhere but at him and hoping he’d say something. “Am I in trouble?”

“Do you know what I read this morning?”

“The newspaper?” she guessed.

“Your file.” He leaned forwarded, rested his forearms on the desk. “You graduated first in your class. From the best medical school in the country.”

She blinked, unsure of where he was going but pretty sure she wasn’t going to like it. “I already knew that?” she asked, her nervousness forcing her snark into a question.

Dr. Morozova sneered. “There it is again.”

“There what is?”

“That appalling lack of confidence. I grilled you for three hours yesterday. Based on your tone alone, I would have said you had no idea what you were talking about – yet you answered every question I asked perfectly. You don’t seem to know what it is you know, let alone have the ego to slice into someone else.”

Her anger at being insulted finally eclipsed her anxiety. “I figured if I ever needed extra ego, there would be no shortage of surgeons to borrow it from. And here I am, paired up with you, giving me a convenient lifetime supply.”

He leaned forward even further, nearly in her face despite the desk between them. “I have the ego,” he said, voice tense but even, “because I’m the best at what I do. If I second-guessed myself all the time, I couldn’t be.”

Her brain generated a number of responses to that, but she bit her tongue, not trusting herself to not make a bad situation worse.

“You could be an excellent surgeon if you believed in yourself.”

“Just because I don’t think I’m the best doesn’t mean I don’t believe in –”

“You don’t,” he interrupted. Then he leaned back in his chair, picked up a file of case notes and began leafing through them, dismissing her. “I hope you’ll decide to one day, though. Preferably soon.”

*

There were leaves on the trees. And birds. Alina blinked slowly, allowing her brain to reacclimate to sunlight and the fact that a world existed beyond the walls of the hospital. Her first week as an intern had been brutal but she hadn’t killed anyone – a low bar but a good start. She inhaled deeply and mentally gave herself a gold star as she began the walk to her car. Good job not murdering your patients, Alina.

“Leaving already, Dr. Starkov?”

Alina startled and stopped, turning towards the voice. Her mentor sat on a bench outside the hospital, a stack of files in his lap.

They’d spoken almost not at all since their meeting in his office several days prior, though he’d been conspicuously present as she went about her rounds, hovering in the shadows, watching, waiting – though for what, she wasn’t sure. She had returned the favor during his surgeries, positioning herself in the corners of the room to watch as he sliced, examined, and arranged with a deftness and confidence that she would never be able to muster. She hadn’t killed any humans her first week, but she was getting ready to bury her hope of becoming even a mediocre surgeon in a shallow grave.

She sighed and rubbed a hand across her face, trying to hide both her fatigue and her caffeine shakes. “Yeah, it’s … I’m off, now. I’ve been working for twenty-four hours straight.”

“Is that all.” His gaze was even and clear though Alina could have sworn he’d been at the hospital at least as long as she had. “They let interns get by with so little these days.”

This was too much. Half the reason his reputation was what it was was that he was impossibly young himself – while there were other surgeons that approached his skill level, none were within even a decade or two of his age. “It can’t possibly be that different from when you were a medical student,” she snapped.

“You’d be surprised at what’s changed.”

His medical school must have had a class in non-answers or else he was just a prodigy at those, too. “How old are you, anyway?

“One hundred and twenty.”

She lowered her lids halfway. “You expect me to believe that?”

“Yes,” he turned back to his files. “I count in surgeon years. If you can ever be bothered to become a decent surgeon, you will too, soon enough.”

*

Dr. Morozova materialized seemingly from nowhere as Alina was making herself coffee in the breakroom. She avoided spilling it all over her white coat, but it was a close call.

He leaned against the counter in front of the sugars she’d been about to grab, a case file dangling carelessly from one hand. “There’s a surgery I want you to take tomorrow.”

That was enough to almost make her forget her coffee. “What? Why?”

“Because I’m a surgeon and you’re my intern.”

“You don’t even like me.” One of these days, Alina would remember that she didn’t always have to say what she was thinking.

One brow raised a millimeter. “I don’t have to like you.” A beat, considering. “I saw how you handled Mrs. Bratslov’s case yesterday.”

“You saw that?” she whispered. It had not been her finest hour; she’d been performing a routine examination when the woman had gone into cardiac arrest. Alina had screamed for backup, grabbing the defibrillator and giving the first person into the room the instructions that happened to pop into her head. They hadn’t been the ones she’d learned in medical school, though at the time she said them they seemed correct; she still hadn’t figured out why.

“I did.”

“She almost died.”

“But she didn’t.” He straightened and walked towards her, his head tilted down to look her in the eyes. “You made a call –”

“A bad one,” she interrupted, though he had to have known it.

“The only bad calls are the ones that don’t work. Something went wrong and you handled it, well. There is confidence buried somewhere in there. You just need the right thing to bring it out.”

“And you think this is the way to do it?”

He handed her a file. “Read this tonight. Surgery is tomorrow.”

*

She scrubbed her hands viciously, trying to project the confidence she knew she should feel, attempting to hide the shaking that betrayed her intense nerves over her very first surgery.

“This is straightforward,” Dr. Morozova said from the sink next to her. “Simple patellar fix. In and out.”

“Right, right.” Alina nodded her head, scrubbing under her fingernails. “I just don’t want to forget the plan.”

“You remember the plan.”

“Sure I do.” She swallowed. “But could we maybe just go over it one more time?”

He cut her a glance. She was worried he might call off the surgery right now, send her home, kick her out of the program – but whatever he saw in her face, he relented. “One more time: we’re going to go in there. I’m going to pick up a scalpel and get the site prepared for you. That means that I will strip away all of the skin, all of the flesh, until you have no surface but knee. All you have to do is take it from there.” He lifted his foot from the pedal, turning off the faucet. “Ready?”

She rinsed her forearms and did the same. “As I’ll ever be.”

“You need to believe in yourself. For what it’s worth,” he continued as he shook the excess water from his fingers in the sink, “I do.”

He headed towards the operating room before she could respond. When he reached the door he turned, hands held in front of him, ready to push it open with his back. “Wait,” she said. “What are you wearing?”

“Scrubs,” Dr. Morozova replied.

“They’re black.”

A corner of his lips quirked, not quite a smile. “Hides the blood.”

He leaned back into the door, letting it swing shut behind him. Alina took a deep breath and followed suit, entering the operating room for her first surgery.

*

Her hands had stopped shaking by the time her mentor handed her the scalpel and she made her first cut into a living human. It had gone better than she anticipated – not only had she done well, but, to her horror, she’d enjoyed it. Dr. Morozova had stood as he had for most of the week prior – unmoving, silent, just watching – and she had been grateful for the mask that had hidden her smile as she sewed the final stitches into place.

Her fourth day as an intern, she had put in an inquiry to the anesthesiology department to see if a transfer might be possible. She’d heard the saying in medical school before, and they had repeated it to her then: “If your favorite place in the hospital is the operating room, be an anesthesiologist. If your favorite place in the world is an operating room, be a surgeon.”

After the surgery, as the two of them made their way through the maze of corridors to their lockers, shoes squeaking on the linoleum floor, she felt it acutely: she was walking away from her favorite place in the world.

Her mentor looked down at her. Even without the safety of a mask, she found that her smile couldn’t be constrained.

“I told you,” was all he said.

*

Her fifteenth surgery made her feel as invincible as the first. “Did you see that?” Alina practically screamed, jumping into the air. “I crushed that tendon!” She furrowed her brow. “In a good way.”

“That you did,” Dr. Morozova agreed. “But the surgery ended minutes ago. Take some of that youthful exuberance and direct it towards the problem at hand.”

“You’re no fun at all,” Alina complained. He’d become a more active mentor over the last month; she had thought she might find some humanity underneath his all-work-no-play exterior, but she’d only found an interior that was no-play-all-work.

“You’re not the first person to point that out.”

She sighed, not wanting to let go of the post-surgical high, but finally turned around. She was face to face with a tumor on a backlit scan. She examined it a while, trying to focus.

“Well?” Dr. Morozova asked from behind her. “What’s your diagnosis, doctor?”

She’d been working with him on straightforward cases so far, building up, but this was the first time he’d let her see what the whole department referred to as a Morozova Surgery. The tricky surgeries, the ones only he could handle.

The answer hit her. She lifted her hand to her mouth. “We’re going to have to take the whole thing out.” The surgery was going to be horrifyingly invasive – this was not a part of the body she was looking forward to rooting around for cancer cells in, but there was no other choice.

“What about cutting off the blood supply? Finding some way to starve it?”

He was testing her, and she shook her head, transfixed with the image, beginning to mentally step through the incisions. “We’re not going to be able to control the tumor, it’s too much. We’re going to have to cut it out completely.” She whirled around, more confident than she could ever remember being before. “This is going to be fun.”

He smiled at her for a moment, then looked at the desk he sat on and moved a paper to one side. “Yes,” he said. “It will be.”

*

The next week, Alina high-fived the head of surgery after he had watched them perform the operation – flawlessly. She was walking down the hall with her mentor, still smiling to herself when Dr. Morozova leaned closer and spoke.

“We don’t high five over surgeries, Alina.”

“You don’t,” she replied. “Maybe people just like me more.”

“If you keep up that sort of behavior,” he continued, his voice casual and more serious for it, “you’ll kill both of our careers.”

“My career will be just fine.” They reached a turn in the hallway where Alina would head back to her locker and Morozova to his. “And if your whole career is built on being an unrelenting asshole, maybe it’s time to rethink your strategy.”

He lifted an eyebrow. “It’s half the reason I went into surgery in the first place.”

“What’s the other half?” she asked, but he just continued down the hallway. “Wait,” she called after him, “where are you going?”

“Home,” he replied over his shoulder without breaking his stride.

She hadn’t really thought that he lived at the hospital, but as she watched him walk away she realized she’d never actually seen him leave. She stood dumbly as his black clad figure disappeared into the parking structure, a strange loneliness settling in her chest. She’d never been in the hospital without Dr. Morozova before.

She blinked a few times, shook her head, then headed to her locker. Whatever she was feeling, it was nothing that a hot shower and a good night’s sleep wouldn’t cure.

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Its not personal

The last two weeks have been incredibly stressful. I haven’t felt this pressured since, lets see, 2018. No one told me this job was ever going to be easy, but at least leave me the right to crib about it. I don’t usually though. You might ask “Well, isn’t that what this blog is all about?” No. This blog is an outlet in my journey towards self realization, so don’t be a douche about it. This post is a tale of personal trial and tribulation and how this has had a profound impact on how I treat my patients. Needless to point out, like every other blog post, this is fairly long, so brace yourself.

I had just come back from an evening shift and was catching up on season 2 of The West Wing, nothing different from the usual post shift nights. It was around 1 am when my neighbor knocked on my door. His father who lived 3 hours away from the city was taken to a nearby hospital with complaints of severe retrosternal chest pain. The doctors there diagnosed it as a cardiac event and did not have the facilities to handle the patient. My visibly worried and flustered neighbor, who is other wise one of the most calmest people I know, had come to me for counsel. I spoke to the doctors over the phone and their diagnosis was clear - ST depressions in the ECG and typical nature of the pain - this was likely an NSTEMI or Unstable Angina. I asked for a cardiac enzyme panel and an immediate transfer to my hospital in Hyderabad. The cardiac enzymes came negative in the time they were arranging for the ambulance, So most likely an unstable angina. I asked my neighbor to relax and bring him to Hyderabad immediately. This should be pretty straight forward to handle. We both left to my hospital in anticipation of his arrival. I spoke to the managers on duty before hand so we could get the financial conversations out of the way early. This was around 3 AM in the morning and I was in the ER following up lab and radiology reports of the patients I admitted the previous night as I awaited their arrival and my neighbor waited at the hospital entrance. The ER door slammed open with a trolley being wheeled in in a rush and a patient lying in a pool of vomit, semi conscious, and then right behind the trolley, I saw my neighbor running in breathless, looking for me. Shit. This patient was my neighbor’s father. Something had gone very very wrong.

We moved him to Priority 1, me and two other ER docs took charge. The patient was now coming around and writhing in chest pain radiating to his back. He was incredibly restless, bouncing up and down the trolley to a point where we had to physically restrain him just to get the ECG. Pain score easily at 9/10. Non medically speaking - imagine being awake watching a bear maul your guts. The cardiologist was right by side, ecg now showed a qRBBB pattern - this is bad, very bad. I was holding the patients hand trying to calm him down as pain meds were being pushed in in rapid succession, and then it happened. I was talking to him, calming him down, and in that moment, he stopped talking, his eyes rolled up, he protruded his tongue, clenched his jaw, squeezed my hand in a death choke, started seizing and crashed. My colleagues crash intubated him and as I looked away in despair, my eyes met with my neighbors.

I was at a loss of words to explain the turn of events over the last five minutes. Most likely vasovagal, but this was unanticipated. I felt responsible and I felt helpless. A 70 year old in cardiogenic shock on mechanical ventilator and likely aspiration - I knew the odds. I knew I was staring down a barrel of potential complications most likely ending in death, but little did I know there was far worse in store. For now though, I tried to explain to my neighbor that we’re doing whatever we possibly can, that we’re taking him to the cath lab and I’m going to be there by his fathers side through all this. One look at his father lying motionless on the bed with an Endotracheal tube down this throat, he held my hand and broke down crying.

We rushed him to the cathlab, angio showed double vessel disease with stenosis but it didn’t explain the pain. This was not an infarct and the flow to myocardium was still intact. It had to be something else. We took the cue of the severe tearing type of pain radiating to the back he complained of on presentation and took him to CT aortogram to rule out a dissection, also because there was some disagreement over how his distal pulses were. It was negative for dissection but I noted a mildly bulky pancreas and asked for a serum amylase and lipase to cover that base. It was 6 am by now and there was nothing more to be done than wait and hope the vasopressors held on to dear life. I walked out of the Cardiac ICU, mustered all my courage and told the family that this is looking bad. We’re doing our best, but with no concrete diagnosis, I had little to offer. The neighbor drove me and his family back home. His sister and his completely unaware mother sat in the back seat worried and . The silence on the way back home was defeaning.

I hadn’t felt a depressive episode like this, not in the last 8 years. I tried to sleep it off, but that was futile. I was responsible. It was my decision to treat him at my hospital and he was my responsibility. Despite doing everything we possibly could, I was going to lose him. The very thought that I would have to face my neighbor everyday, and be seen in his eyes as the guy who couldn’t save his father, broke me. I came home at around 6 30 am and got a call from my HOD at 8 am that there’s an acute shortage in the ER and they needed me to come in to work and help out. If this were my older self, I would have been there in a jiffy, but on this morning, I could not get myself out of bed. I felt despair, I felt pain and I felt hopeless. I did not want to disappoint my HOD and I also wanted to know how my patient was doing, so I pushed myself and got to work to one of the most messed up shifts I’ve done in a while. May be it was just my depression, but it was a one hell of a busy republic day morning. Why oh why do people save their illnesses just for the holidays?! My patient was still on the ventilator, high inotropic support, an unreasonable no. of ectopics on the ecg and pretty bad lungs, but negative amylase and lipase. I still had no hope to offer and everything seemed so futile. I don’t even recall how the next few days passed. I barely ate, barely slept and I still put up a face at work, try and be the most pleasant doctor you could find in the ER.

On the third day, he started improving rapidly. No more vasopressor support, no more ectopics, resolving TLC. On day 4, he was extubated and I finally breathed a sigh of relief. I finally slept peacefully. I finally smiled at home and spoke up to my worried sick mother. I haven’t seen her this helpless before. She knew I only had the best intentions, she liked to believe that I did nothing wrong at all, that I was their best hope. Can’t blame her. Mothers are like that. Unconditional love, unshakable confidence in you and blind faith. She could not do or say anything that would make me feel better. She knew how much I cared about this, how much I’ve put myself into this, but for now, she was helpless. That all changed like I said. The patient was off the ventilator and on his way to a full recovery.

He came home today. After two full weeks in the Cardiac ICU, he came home today. I paid him a visit and he himself pulled up a chair to offer me a seat. Today is a good day. I smiled with all my heart and a sense of satisfaction I haven’t felt in ages. I cannot take credit for all the hardwork put in by some of the finest cardiologists, intensivists, emergency physicians and nurses to bring him back. I am proud that I can look up to these people at times of despair and I am lucky. As for his loving wife and caring son, I can only feel happy and thankful. I did give him a thorough dressing down for popping NSAIDs like tic tacs and trusting his local pharmacist more than his doctor, but that’s just most Indians.

The purpose of this post is not to talk about a very odd presentation or a difficult case management lesson. The purpose of this post is to talk about physician wellness. The toll that the responsibility of someones life in your hands takes on your mental state of being is indiscernible to someone who has never faced it before. I spent the last two hours on this particular sentence trying to come up with a way to explain it and I’ve failed. Writers block? No. It is a sense of duty and privilege we can never fathom fully.

This is a tale of a very personal emergency. I went the extra mile with this patient. This made me ask myself if I’m not doing to this every patient. Is it humanly possible to feel this deeply about all of my sick patients and live a normal life without going absolutely mad?. It’s like having 40 to 60 of your family members fall incredibly sick in a span of 6 hours and all come to you for treatment. That’s my ER’s average foot fall in a day. I will most definitely die an early death , not that i’m not going to now. It is tough, what we do. It breaks us and yet, we keep going. It takes a different kind of crazy to go back to all this, everyday, every patient. It is my hope through this blog that my people realize that these heroes don’t wear capes or don’t have billboards. They’re fighting a system rigged against humanity in general and doing their part as best they can. Cut them some slack, because they’re walking a thin line - to feel, yet not to feel.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pravāsiga: The First of Many Blog Posts

June 7, 2017

ಪ್ರವಾಸ��ಗ (Pravāsiga): (n.) the Kannada word for 'traveler', or at least according to Google Translate.

It's been a week since I've left my room an absolute mess in my last-minute haste to pack for a two-month long trip to Mysore, India. (Shout out to my mother, who understandably, is not pleased about aforementioned mess). In that time since, I have found myself in two countries, three cities, and several wonderful experiences with an incredible team and the absolutely amazing staff at the Swami Vivekananda Youth Movement, the NGO that all of us in the Cornell ILR/Global Health Global Service Learning team will be working with. I've been itching to write about my time here ever since I landed, and the most that I can truly capture is that no matter how I write this, I will never be able to entirely describe what it's been like to be here, but it's worth a shot.

Just a warning, I haven't written in a long time. This post is going to be long, meandering, and more importantly, it's about to get sappy and basic and full of love for a beautiful country, full of inspiring people. It's (kind of) worth a read, I promise!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

My first real glance at India happened from the window of a moving van at 5 in the morning, careening through the lines of State Highway 17, connecting Bangalore to Mysore. Still drowsy from almost two days of travel, I caught glimpses of roadside temples, decorated ornately with statues and idols. Through sleepy eyes, I watched as people woke up to start their day. Children playing with their siblings, adults opening small stands to sell food or helmets or shoes. I saw everything in a whirlwind of greens, browns, and blues - a flash of sky, a stretch of field and trees, and patches of ground and homes and road. I drifted in and out of sleep, still caught in disbelief that I was all the way across the world, the furthest I've been from home on my own. In between dreams and short periods of sleep, I processed about three important things:

1) There were few traffic rules here (a thought I later expressed, to which Anant told me that lane lines were more like suggestions rather than boundaries).

2) I had never seen so many free-roaming cows in my entire life

3) My tailbone was falling asleep more than I was and I couldn't do anything about it for at least another three hours.

*

Later, I was to learn and experience that India was a colorful, bustling, and dynamic country, full of movement and noise and liveliness. The next few days were even more of a blur than the very first van ride. Running around Big Bazaar (aptly described as 'Walmart, but with Indian clothing') trying to find kurtas that would fit was by far one of the most stressful shopping trips I had ever endured. I was not prepared for the narrow, straight cuts of the kurtas or that finding good salwar kameez color combinations would be such a herculean task. I am still struggling to find a good way to keep my dupatta on correctly without it flying into my face or becoming lopsided. Forgetting that the exchange rate stands at about 60 rupees to 1USD has left me flabbergasted for a few seconds every time I've gone up to the cashier and seen my total climb into the hundreds and thousands. I'd like to take this time to apologize to my dad for incurring a few foreign credit card transaction fees because I didn't bring enough rupees with me the first time.

Then from Big Bazaar to Chamundi Hills, where our bus took us far above the city and into the lush green forest. The line (though everyone here calls it a queue!) wrapped around the Chamundeshwari Temple, preventing us from going inside, but we were treated to the sight of (and warned about) several monkeys who lived near the temple grounds. I was to learn that they were incredibly clever and were adept at opening zippers and searching pouches in their hunt for food. Here, I also learned that locals will want to take selfies with all of us American tourists who probably look completely out of place.

We witnessed services at St. Philomena's Church, one of the tallest churches in Asia. We ventured into the underground catacombs to visit St. Philomena's relic. We visited Lalitha Mahal Palace Hotel and Mysore Palace. I officially tried mango lassi in India. We had a photoshoot on a balcony. I was caught in the rain when Mysore Palace was completely illuminated, sending a flock of roosting birds rising to the sky. I came back to the hostel tired, ready to sleep before 10pm every night.

I couldn't get enough of India.

*

I have wanted to visit India for years now, and nothing can still quite make me believe that I am actually here. But even more than that, that I am here, pursuing the chance to work in the field that I have grown passionate about and with an organization that has exemplified excellence in so many initiatives to better the health, education, and community development of many of India's poor.

My interest in public health grew from my increasing frustration with the rigidity that most of my STEM course work presented in its curriculum. I had long been in love with the intricate and fascinating nature of biology and human physiology, but when it came to keeping my medical aspirations in perspective, I found that I was not satisfied with how narrow and exclusively STEM-focused my future was looking. Courses on medical anthropology, sociology, inequality, and health care had captured my attention with its holistic approach to understanding the socioeconomic and environment determinants to health. I found that I was beginning to become interested in more than just the biomedical body, but that the same passion that had once driven me to study neurobiology was now enveloping a new desire to understand health and all that impacts it, on a global scale. If you want to hear more about my pre-med existential crisis, feel free to hit me up about it because there's still plenty more episodes to come!

SVYM has been instrumental in working to improve health conditions in communities all across Karnataka state for over thirty years. Their attention to detail, commitment to grassroots initiatives and raising the voices of tribal communities, and understanding of the vast complexities that exist in a rapidly developing country has continued to amaze and stun me. For the next two weeks, we are incredibly fortunate to be taking classes from the Vivekananda Institute of Indian Studies with SVYM on everything from Indian Culture and Civilization, Gender Studies, Global Health and Labor Economics, and Kannada.

My favorite by far, has been the Global Health classes. Each lecture has been incredibly eye-opening and informative about the public health system in India. For a country of 1.3 billion people, there exists a system designed to serve the primary, secondary, and tertiary level health care needs that strives to deliver free, accessible, and quality treatment. I'm not going to go into the entire structure, but at the primary level, there are three main lines of defense: ASHAs (Accredited Social Health Activists), sub-district centers, and primary health centers (PHC). These institutions and the staff that run them are responsible for overseeing tens of thousands of people who otherwise cannot afford private health care.

We had the privilege of visiting an urban PHC and talking with the medical and nursing staff, as well as the ASHAs. The medical officer (the senior doctor who runs the PHC) sees anywhere from 70-100 patients per day and provides diagnostics, basic lab services, immunizations, and other basic treatment services. However, it was the ASHAs, all women dressed in pink saris that caught my attention. Their work had been described to us in class as being the first resources for any community. They were members of the communities they were chosen to serve and were responsible for an enormous amount of responsibilities. ASHAs are all married mothers, who bear the task of acting as health educators, messengers who remind patients of upcoming check-ups, consultants, and maternal health workers. For so much work, ASHAs are guaranteed no pay. They only receive incentives for successfully completing tasks, like ensuring a mother attends pre- and ante-natal care with the public system, as well as delivering the baby with the public institution. A growing trend of mothers utilizing ASHA services but ultimately delivering their children at private institutions has negatively impacted many of these ASHAs - for if they will not be paid if the mother does not ultimately stay within the public system. All five ASHAs present at the PHC expressed their discontent with the salary and payment system - and revealed to us that they had organized and were fighting to receive better financial security.

These were not the only issues with the public health system. All along the public health institutional structure, there are staff and supply shortages that need to constantly be met. We learned the extent of these shortages - particularly with doctors, specialists, and health staff - in class and it brought up several questions: what has the Indian government done so far to encourage more medical students to take up these posts? Are we seeing more medical students express and pursue interests in public health?

Despite plans to make public service compulsory for medical graduates and a growing need for public health health workers, the current answer is that we will always be looking at these shortages unless something changes. Commonly, the private sector or international opportunities lure talent and brainpower away from these public positions. I felt frustration at this until I realized that all around the world - including the US - this is a phenomenon that occurs over and over. I had entered into the premed track with the intention of pursuing a medical career in neurosurgery that would take me to the top, cutting-edge hospitals. The thought of it is alluring and hard to resist. No matter how strong your conviction is in medicine and helping to save lives, the very real need to be practical can't be ignored. With rising tuition bills, increased concerns over getting into medical schools, and general economic worries, it would be ridiculous to not admit that financial stability was an enticing factor.

But this work is important, irregardless of the money it pays or doesn't pay. Public health is the active fight to protect and ensure the health of our communities. It is concerned with every determinant of health that exists, beyond the biomedical lens. Public health is involved in politics, in social justice, in environmental issues, in the ways that we treat each other on a day to day basis. The gravity of this work is not lost on me - we learn from SVYM and VIIS every day about the complexities of delivering and supporting initiatives that have not reached communities that need it most. Beyond all the sight-seeing and colorful tourism, I don't feel that I am mistaken in saying that the strongest impression that my experience in India will leave me with is the reaffirmation of my passion for service and healthcare. Only a week in, and I've been given an amazing chance to work alongside one of the most amazing NGOs I've ever heard of, and I can't wait to see what comes next.

I will continue to document the next two months and keep you all updated on my embarrassing experiences and all that I will learn. I am just as, if not more, awkward of an international tourist/student as I am a domestic citizen/student. Until the next extravagantly long post in which I will probably say something cliche and sappy again, I'm wishing all of you love and happiness.

Matte siguva (See you again), Winnie

PS: I've never flown Emirates before this trip, but after flying Emirates, it's all I want to fly again. This has little relevance to the rest of my experience but I finally watched Dr. Strange, Tangled, and Up and yes, I did cry during Up even though I've seen Carl and Ellie's story like 87 times because I am an utter wreck of emotions and a hopeless romantic at heart.

PPS: How on earth I got through this entire post without mentioning food is beyond me. The food is delicious and I am adjusting to going vegetarian for the summer. My spice tolerance is slowly building but I am slightly scared because apparently my next work site, the food is spicier than it is here and no matter how much I like the food here, I am currently craving grilled cheese sandwiches and my mother's cooking. Please send food.

PPPS: I am V MAD because Tropicana has been holding out on us because did you know they have lychee juice here??? I did not. Also Tropicana Slice Mango juice is to DIE for and you will catch me drinking this by the gallon if I could.

PPPPS: This is my last post-script, for now.

0 notes