#and also nearly became a quaker

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

If the other dude sends me one more message I will commit to blocking him since he’s just been cheating and mooching off some of my other classmates all year (even started sending me messages during the euros finals)

— London anon

BLOCK HIMMMM (or send him incorrect shit or invitations to become a Jehovah's Witness.)

#asks??? in this economy???#london anon#i remember when i nearly became a jehovahs witness#and also nearly became a quaker

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene (1742-1786) was a general of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). One of George Washington's most trusted subordinates, Greene served capably as Quartermaster General before leading the southern American army during the final years of the war. He is often considered the second-best American Revolutionary general, behind only Washington himself.

Early Life

Greene was born on 7 August 1742 on Forge Farm, near Potowomut Creek in the township of Warwick, Rhode Island. He was the third of eight sons born to Nathanael Greene Sr., a prosperous farmer and ardent Quaker; indeed, the father's piety must have been generational, as Greene's ancestors had initially fled England in 1635 to escape religious persecution. Nathanael Greene Sr., lived with his children and second wife, Mary Mott Greene (mother to the younger Nathanael), on the family farm, which had turned into a lucrative enterprise; by the time the younger Nathanael was born, the farm included a farmhouse, a general store, a gristmill, a sawmill, and a forge. The forge, which produced anchors and chains, was by far the most profitable aspect of the family business, employing many workers and eventually becoming one of the foremost businesses in Rhode Island.

As a child, the younger Nathanael had a thirst for education that could not be quenched by his father's strict Quakerism. As Greene would later recall:

My father was a man had an excellent understanding and was governed in his conduct by humanity and kind benevolence. But his mind was overshadowed with prejudices against literary accomplishments.

(quoted in McCullough, 21)

As a result of his father's 'prejudices', Nathanael and his brothers were not sent to school but were instead put to work in the fields. This did not stop Greene from seeking out knowledge on his own; under the guidance of Ezra Stiles, future president of Yale College, Greene became a voracious reader. Anytime he was not required to work in the fields or at the forge, Greene had his nose buried in a book, reading classical literature as well as the more recent philosophical works that defined the Age of Enlightenment. He was also fond of studying mathematics, history, and law.

The autodidactic Greene grew into a handsome, robust man nearly six feet (183 cm) tall, with strong arms, a broad forehead, and "fine blue eyes" (McCullough, 22). A childhood accident left him with a slight limp in his right leg, his right eye was cloudy as an effect of smallpox inoculation, and he often suffered from asthma attacks and poor health. Yet he was nevertheless a charismatic and jolly young man who was often found in the company of women. By 1770, Greene had proved industrious enough for his father to put him in charge of a second family-owned foundry in the town of Coventry, Rhode Island. When Nathanael Greene Sr., died later that same year, Greene and his brothers inherited the entire family business. In 1774, Greene courted and married the pretty 19-year-old Catherine 'Caty' Littlefield, with whom he would have seven children between 1776 and 1786.

Continue reading...

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

G.3.1 Is “anarcho”-capitalism American anarchism?

Unlike Rothbard, some “anarcho”-capitalists are more than happy to proclaim themselves “individualist anarchists” and so suggest that their notions are identical, or nearly so, with the likes of Tucker, Ingalls and Labadie. As part of this, they tend to stress that individualist anarchism is uniquely American, an indigenous form of anarchism unlike social anarchism. To do so, however, means ignoring not only the many European influences on individualist anarchism itself (most notably, Proudhon) but also downplaying the realities of American capitalism which quickly made social anarchism the dominant form of Anarchism in America. Ironically, such a position is deeply contradictory as “anarcho”-capitalism itself is most heavily influenced by a European ideology, namely “Austrian” economics, which has lead its proponents to reject key aspects of the indigenous American anarchist tradition.

For example, “anarcho”-capitalist Wendy McElroy does this in a short essay provoked by the Seattle protests in 1999. While Canadian, her rampant American nationalism is at odds with the internationalism of the individualist anarchists, stating that after property destruction in Seattle which placed American anarchists back in the media social anarchism “is not American anarchism. Individualist anarchism, the indigenous form of the political philosophy, stands in rigorous opposition to attacking the person or property of individuals.” Like an ideological protectionist, she argued that “Left [sic!] anarchism (socialist and communist) are foreign imports that flooded the country like cheap goods during the 19th century.” [Anarchism: Two Kinds] Apparently Albert and Lucy Parsons were un-Americans, as was Voltairine de Cleyre who turned from individualist to communist anarchism. And best not mention the social conditions in America which quickly made communist-anarchism predominant in the movement or that individualist anarchists like Tucker proudly proclaimed their ideas socialist!

She argued that ”[m]any of these anarchists (especially those escaping Russia) introduced lamentable traits into American radicalism” such as “propaganda by deed” as well as a class analysis which “divided society into economic classes that were at war with each other.” Taking the issue of “propaganda by the deed” first, it should be noted that use of violence against person or property was hardly alien to American traditions. The Boston Tea Party was just as “lamentable” an attack on “property of individuals” as the window breaking at Seattle while the revolution and revolutionary war were hardly fought using pacifist methods or respecting the “person or property of individuals” who supported imperialist Britain. Similarly, the struggle against slavery was not conducted purely by means Quakers would have supported (John Brown springs to mind), nor was (to use just one example) Shay’s rebellion. So “attacking the person or property of individuals” was hardly alien to American radicalism and so was definitely not imported by “foreign” anarchists.

Of course, anarchism in American became associated with terrorism (or “propaganda by the deed”) due to the Haymarket events of 1886 and Berkman’s assassination attempt against Frick during the Homestead strike. Significantly, McElroy makes no mention of the substantial state and employer violence which provoked many anarchists to advocate violence in self-defence. For example, the great strike of 1877 saw the police opened fire on strikers on July 25th, killing five and injuring many more. “For several days, meetings of workmen were broken up by the police, who again and again interfered with the rights of free speech and assembly.” The Chicago Times called for the use of hand grenades against strikers and state troops were called in, killing a dozen strikers. “In two days of fighting, between 25 and 50 civilians had been killed, some 200 seriously injured, and between 300 and 400 arrested. Not a single policeman or soldier had lost his life.” This context explains why many workers, including those in reformist trade unions as well as anarchist groups like the IWPA, turned to armed self-defence (“violence”). The Haymarket meeting itself was organised in response to the police firing on strikers and killing at least two. The Haymarket bomb was thrown after the police tried to break-up a peaceful meeting by force: “It is clear then that … it was the police and not the anarchists who were the perpetrators of the violence at the Haymarket.” All but one of the deaths and most of the injuries were caused by the police firing indiscriminately in the panic after the explosion. [Paul Avrich, The Maymarket Tragedy, pp. 32–4, p. 189, p. 210, and pp. 208–9] As for Berkman’s assassination attempt, this was provoked by the employer’s Pinkerton police opening fire on strikers, killing and wounding many. [Emma Goldman, Living My Life, vol. 1, p. 86]

In other words, it was not foreign anarchists or alien ideas which associated anarchism with violence but, rather, the reality of American capitalism. As historian Eugenia C. Delamotte puts it, “the view that anarchism stood for violence … spread rapidly in the mainstream press from the 1870s” because of “the use of violence against strikers and demonstrators in the labour agitation that marked these decades — struggles for the eight-hour day, better wages, and the right to unionise, for example. Police, militia, and private security guards harassed, intimidated, bludgeoned, and shot workers routinely in conflicts that were just as routinely portrayed in the media as worker violence rather than state violence; labour activists were also subject to brutal attacks, threats of lynching, and many other forms of physical assault and intimidation … the question of how to respond to such violence became a critical issue in the 1870s, with the upswelling of labour agitation and attempts to suppress it violently.” [Voltairine de Cleyre and the Revolution of the Mind, pp. 51–2]

Joseph Labadie, it should be noted, thought the “Beastly police” got what they deserved at Haymarket as they had attempted to break up a peaceful public meeting and such people should “go at the peril of their lives. If it is necessary to use dynamite to protect the rights of free meeting, free press and free speech, then the sooner we learn its manufacture and use … the better it will be for the toilers of the world.” The radical paper he was involved in, the Labor Leaf, had previously argued that “should trouble come, the capitalists will use the regular army and militia to shoot down those who are not satisfied. It won’t be so if the people are equally ready.” Even reformist unions were arming themselves to protect themselves, with many workers applauding their attempts to organise union militias. As worker put it, ”[w]ith union men well armed and accustomed to military tactics, we could keep Pinkerton’s men at a distance … Employers would think twice, too, before they attempted to use troops against us … Every union ought to have its company of sharpshooters.” [quoted by Richard Jules Oestreicher, Solidarity and Fragmentation, p. 200 and p. 135]

While the violent rhetoric of the Chicago anarchists was used at their trial and is remembered (in part because enemies of anarchism take great glee in repeating it), the state and employer violence which provoked it has been forgotten or ignored. Unless this is mentioned, a seriously distorted picture of both communist-anarchism and capitalism are created. It is significant, of course, that while the words of the Martyrs are taken as evidence of anarchism’s violent nature, the actual violence (up to and including murder) against strikers by state and private police apparently tells us nothing about the nature of the state or capitalist system (Ward Churchill presents an excellent summary such activities in his article “From the Pinkertons to the PATRIOT Act: The Trajectory of Political Policing in the United States, 1870 to the Present” [CR: The New Centennial Review, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 1–72]).

So, as can be seen, McElroy distorts the context of anarchist violence by utterly ignoring the far worse capitalist violence which provoked it. Like more obvious statists, she demonises the resistance to the oppressed while ignoring that of the oppressor. Equally, it should also be noted Tucker rejected violent methods to end class oppression not out of principle, but rather strategy as there “was no doubt in his mind as to the righteousness of resistance to oppression by recourse to violence, but his concern now was with its expedience … he was absolutely convinced that the desired social revolution would be possible only through the utility of peaceful propaganda and passive resistance.” [James J. Martin, Men Against the State, p. 225] For Tucker “as long as freedom of speech and of the press is not struck down, there should be no resort to physical force in the struggle against oppression.” [quoted by Morgan Edwards, “Neither Bombs Nor Ballots: Liberty & the Strategy of Anarchism”, pp. 65–91, Benjamin R. Tucker and the Champions of Liberty, Coughlin, Hamilton and Sullivan (eds.), p. 67] Nor should we forget that Spooner’s rhetoric could be as blood-thirsty as Johann Most’s at times and that American individualist anarchist Dyer Lum was an advocate of insurrection.

As far as class analysis does, which “divided society into economic classes that were at war with each other”, it can be seen that the “left” anarchists were simply acknowledging the reality of the situation — as did, it must be stressed, the individualist anarchists. As we noted in section G.1, the individualist anarchists were well aware that there was a class war going on, one in which the capitalist class used the state to ensure its position (the individualist anarchist “knows very well that the present State is an historical development, that it is simply the tool of the property-owning class; he knows that primitive accumulation began through robbery bold and daring, and that the freebooters then organised the State in its present form for their own self-preservation.” [A.H. Simpson, The Individualist Anarchists, p. 92]). Thus workers had a right to a genuinely free market for ”[i]f the man with labour to sell has not this free market, then his liberty is violated and his property virtually taken from him. Now, such a market has constantly been denied … to labourers of the entire civilised world. And the men who have denied it are … Capitalists … [who] have placed and kept on the statue-books all sorts of prohibitions and taxes designed to limit and effective in limiting the number of bidders for the labour of those who have labour to sell.” [Instead of a Book, p. 454] For Joshua King Ingalls, ”[i]n any question as between the worker and the holder of privilege, [the state] is certain to throw itself into the scale with the latter, for it is itself the source of privilege, the creator of class rule.” [quoted by Bowman N. Hall, “Joshua K. Ingalls, American Individualist: Land Reformer, Opponent of Henry George and Advocate of Land Leasing, Now an Established Mode,” pp. 383–96, American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Vol. 39, No. 4, p. 292] Ultimately, the state was “a police force to regulate the people in the interests of the plutocracy.” [Ingalls, quoted by Martin, Op. Cit., p. 152]

Discussing Henry Frick, manager of the Homestead steelworkers who was shot by Berkman for using violence against striking workers, Tucker noted that Frick did not “aspire, as I do, to live in a society of mutually helpful equals” but rather it was “his determination to live in luxury produced by the toil and suffering of men whose necks are under his heel. He has deliberately chosen to live on terms of hostility with the greater part of the human race.” While opposing Berkman’s act, Tucker believed that he was “a man with whom I have much in common, — much more at any rate than with such a man as Frick.” Berkman “would like to live on terms of equality with his fellows, doing his share of work for not more than his share of pay.” [The Individualist Anarchists, pp. 307–8] Clearly, Tucker was well aware of the class struggle and why, while not supporting such actions, violence occurred when fighting it.

As Victor Yarros summarised, for the individualist anarchists the “State is the servant of the robbers, and it exists chiefly to prevent the expropriation of the robbers and the restoration of a free and fair field for legitimate competition and wholesome, effective voluntary cooperation.” [“Philosophical Anarchism: Its Rise, Decline, and Eclipse”, pp. 470–483, The American Journal of Sociology, vol. 41, no. 4, p. 475] For “anarcho”-capitalists, the state exploits all classes subject to it (perhaps the rich most, by means of taxation to fund welfare programmes and legal support for union rights and strikes).

So when McElroy states that, “Individualist anarchism rejects the State because it is the institutionalisation of force against peaceful individuals”, she is only partly correct. While it may be true for “anarcho”-capitalism, it fails to note that for the individualist anarchists the modern state was the institutionalisation of force by the capitalist class to deny the working class a free market. The individualist anarchists, in other words, like social anarchists also rejected the state because it imposed certain class monopolies and class legislation which ensured the exploitation of labour by capital — a significant omission on McElroy’s part. “Can it be soberly pretended for a moment that the State … is purely a defensive institution?” asked Tucker. “Surely not … you will find that a good nine-tenths of existing legislation serves … either to prescribe the individual’s personal habits, or, worse still, to create and sustain commercial, industrial, financial, and proprietary monopolies which deprive labour of a large part of the reward that it would receive in a perfectly free market.” [Tucker, Instead of a Book, pp. 25–6] In fact:

“As long as a portion of the products of labour are appropriated for the payment of fat salaries to useless officials and big dividends to idle stockholders, labour is entitled to consider itself defrauded, and all just men will sympathise with its protest.” [Tucker, Liberty, no. 19, p. 1]

It goes without saying that almost all “anarcho”-capitalists follow Rothbard in being totally opposed to labour unions, strikes and other forms of working class protest. As such, the individualist anarchists, just as much as the “left” anarchists McElroy is so keen to disassociate them from, argued that ”[t]hose who made a profit from buying or selling were class criminals and their customers or employees were class victims. It did not matter if the exchanges were voluntary ones. Thus, left anarchists hated the free market as deeply as they hated the State.” [McElroy, Op. Cit.] Yet, as any individualist anarchist of the time would have told her, the “free market” did not exist because the capitalist class used the state to oppress the working class and reduce the options available to choose from so allowing the exploitation of labour to occur. Class analysis, in other words, was not limited to “foreign” anarchism, nor was the notion that making a profit was a form of exploitation (usury). As Tucker continually stressed: “Liberty will abolish interest; it will abolish profit; it will abolish monopolistic rent; it will abolish taxation; it will abolish the exploitation of labour.” [The Individualist Anarchists, p. 157]

It should also be noted that the “left” anarchist opposition to the individualist anarchist “free market” is due to an analysis which argues that it will not, in fact, result in the anarchist aim of ending exploitation nor will it maximise individual freedom (see section G.4). We do not “hate” the free market, rather we love individual liberty and seek the best kind of society to ensure free people. By concentrating on markets being free, “anarcho”-capitalism ensures that it is wilfully blind to the freedom-destroying similarities between capitalist property and the state (as we discussed in section F.1). An analysis which many individualist anarchists recognised, with the likes of Dyer Lum seeing that replacing the authority of the state with that of the boss was no great improvement in terms of freedom and so advocating co-operative workplaces to abolish wage slavery. Equally, in terms of land ownership the individualist anarchists opposed any voluntary exchanges which violated “occupancy and use” and so they, so, “hated the free market as deeply as they hated the State.” Or, more correctly, they recognised that voluntary exchanges can result in concentrations of wealth and so power which made a mockery of individual freedom. In other words, that while the market may be free the individuals within it would not be.

McElroy partly admits this, saying that “the two schools of anarchism had enough in common to shake hands when they first met. To some degree, they spoke a mutual language. For example, they both reviled the State and denounced capitalism. But, by the latter, individualist anarchists meant ‘state-capitalism’ the alliance of government and business.” Yet this “alliance of government and business” has been the only kind of capitalism that has ever existed. They were well aware that such an alliance made the capitalist system what it was, i.e., a system based on the exploitation of labour. William Bailie, in an article entitled “The Rule of the Monopolists” simply repeated the standard socialist analysis of the state when he talked about the “gigantic monopolies, which control not only our industry, but all the machinery of the State, — legislative, judicial, executive, — together with school, college, press, and pulpit.” Thus the “preponderance in the number of injunctions against striking, boycotting, and agitating, compared with the number against locking-out, blacklisting, and the employment of armed mercenaries.” The courts could not ensure justice because of the “subserviency of the judiciary to the capitalist class … and the nature of the reward in store for the accommodating judge.” Government “is the instrument by means of which the monopolist maintains his supremacy” as the law-makers “enact what he desires; the judiciary interprets his will; the executive is his submissive agent; the military arm exists in reality to defend his country, protect his property, and suppress his enemies, the workers on strike.” Ultimately, “when the producer no longer obeys the State, his economic master will have lost his power.” [Liberty, no. 368, p. 4 and p. 5] Little wonder, then, that the individualist anarchists thought that the end of the state and the class monopolies it enforces would produce a radically different society rather than one essentially similar to the current one but without taxes. Their support for the “free market” implied the end of capitalism and its replacement with a new social system, one which would end the exploitation of labour.

She herself admits, in a roundabout way, that “anarcho”-capitalism is significantly different that individualist anarchism. “The schism between the two forms of anarchism has deepened with time,” she asserts. This was ”[l]argely due to the path breaking work of Murray Rothbard” and so, unlike genuine individualist anarchism, the new “individualist anarchism” (i.e., “anarcho”-capitalism) “is no longer inherently suspicious of profit-making practices, such as charging interest. Indeed, it embraces the free market as the voluntary vehicle of economic exchange” (does this mean that the old version of it did not, in fact, embrace “the free market” after all?) This is because it “draws increasingly upon the work of Austrian economists such as Mises and Hayek” and so “it draws increasingly farther away from left anarchism” and, she fails to note, the likes of Warren and Tucker. As such, it would be churlish to note that “Austrian” economics was even more of a “foreign import” much at odds with American anarchist traditions as communist anarchism, but we will! After all, Rothbard’s support of usury (interest, rent and profit) would be unlikely to find much support from someone who looked forward to the development of “an attitude of hostility to usury, in any form, which will ultimately cause any person who charges more than cost for any product to be regarded very much as we now regard a pickpocket.” [Tucker, The Individualist Anarchists, p. 155] Nor, as noted above, would Rothbard’s support for an “Archist” (capitalist) land ownership system have won him anything but dismissal nor would his judge, jurist and lawyer driven political system have been seen as anything other than rule by the few rather than rule by none.

Ultimately, it is a case of influences and the kind of socio-political analysis and aims it inspires. Unsurprisingly, the main influences in individualist anarchism came from social movements and protests. Thus poverty-stricken farmers and labour unions seeking monetary and land reform to ease their position and subservience to capital all plainly played their part in shaping the theory, as did the Single-Tax ideas of Henry George and the radical critiques of capitalism provided by Proudhon and Marx. In contrast, “anarcho”-capitalism’s major (indeed, predominant) influence is “Austrian” economists, an ideology developed (in part) to provide intellectual support against such movements and their proposals for reform. As we will discuss in the next section, this explains the quite fundamental differences between the two systems for all the attempts of “anarcho”-capitalists to appropriate the legacy of the likes of Tucker.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grumblethorpe

Had a lovely day visiting the generational home of the Wisters, a Philadelphia family of merchants and Quakers. This was their summer residence in Germantown, built by John Wister in 1744, which stayed in the family for nearly two centuries. Originally known as "John Wister's Big House," it came to be known as Grumblethorpe in the 18th century.

My primary interest in the Wisters surrounds Sarah "Sally" Wister who wrote a journal in 1777-1778 during which many important events of the American Revolution took place - the battle of Germantown, the siege and reduction of the forts below Philadelphia, the surrender of Burgoyne, the maneuvers at Whitemarsh, the march to Valley Forge and winter encampment there, etc etc.

Sally's family fled their home on Market Street (in Philadelphia proper) for the Foulke Mansion in North Wales, where Sally wrote her journal. Meanwhile, the Germantown residence became a headquarters for British Brigadier-General James Agnew, who was shot during the Battle of Germantown. He was taken back to the Wister house and bled to death in the parlor. Apparently his blood stains are still visible in the wooden floor (pictured above - I think it's more likely whatever the servants used to scrub it clean).

Also pictured is the original silhouette of Sally Wister, the face of the main house, and the Wister library. Because the house remained in the family for so long, passing through relatively few hands over the centuries, much of the property retains its original artifacts.

This is a very peaceful place nearly untouched by time. I highly, highly recommend visiting Grumblethorpe for anyone near Philadelphia with an interest in the American Revolution.

#this is so disorganized#i'll add more later#I love the wisters#especially sally#sarah!!!#american revolution#germantown#philadelphia#colonial america

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

For All the Light I Shut Out - FIVE

Chapter Warnings: panic attack

Masterlist (mobile WIP)

“-and I said they were the best damn cookies next to my Ma’s.”

“‘Cause you’re a fuckin’ suck-up.”

“Well, now she won’t stop bringin’ me those damn oatmeal cookies! It’s like she’s got a central line to the fucking Quaker guy.”

Lily stifled her laugh as she passed Sal and Marnie, two of the administrative assistants for the HR and accounting floors. Fawn from the HR department crowed that she had the greatest cookies of all time and insisted on feeding everyone who would talk to her. Most folks learned quickly to avoid her sugary bricks, but it appeared that Sal was her new target.

“Amapola! Get your cute little tush over here.” A hand waved over the heads of the crowd seated in the Wayne Enterprises cafeteria and Lily followed it to find Gloria, Teddy, and Malcolm in their usual seats. Lily set her tray down and slid into her seat, immediately slapping Teddy’s hand away from her slice of pie.

“I���ll beat your ass and you know I will,” she warned. Teddy offered her a sheepish grin which Lily responded with an eye roll.

The administrative assistants tried to get lunch everyday together. It gave them a chance to get away from their bosses and gossip about what was happening on their floors. Lily rarely had something to contribute but she soaked up every bit of information that was offered. She would then help out Lucius by keeping him up to date on office politics. Who was cheating on their spouse, who was possibly embezzling funds, etc.

Assistants saw and heard everything. People forgot that they were present or assumed that they weren’t intelligent enough to understand what was being discussed. Lily had been underestimated and patronized her whole life. She learned to use that to her advantage.

“Hot topic of the day,” Gloria declared. “Bruce Wayne is back and hot as ever.”

“He passed me in the hall earlier and I nearly swooned,” Malcolm gasped. “What do you think his workout routine is?”

“More like, who is…”

“I’m losing my appetite over here,” Lily grumbled. In fact, she didn’t really have an appetite in the first place. For a Fortune 100 company who raked in billions every year, Wayne Enterprises’ employee cafeteria had awful food options. It was free, so she shouldn’t complain, and it was better than when she dug through trash cans for scraps, but still. Was the gray slop on her tray even edible?

“You look like shit,” Gloria observed. “Which is surprising since you average about four hours of sleep a night and still look fresh as a daisy, so what’s up?”

She shrugged and pushed some of the puce-shaded meatloaf across her tray. “Long night.”

Lily could offer up an anecdote about her run-ins with Wayne. She could tell them about how she almost got mugged -- and worse -- last night. She could talk about how her little sister was now in medical school after over a decade of Lily doing everything in her power just to keep Nadia alive.

But she instead deflected.

“Has anyone seen Kallie?”

Kalliope Marks was the only non-assistant allowed in their little group. Where Lily was the science, Kallie was the math. She was a whizz at calculations and quickly became one of the company’s top accountants. But she was a quiet figure who hated being the center of attention. When Gloria asked if she could bring along someone to lunch and Kallie joined them, Lily took one look at the shy woman and decided that they would be best friends.

Gloria grimaced. “Last I heard, Vandeer was chewing her out over a late report.”

James Vandeer, also known as the head of accounting and the biggest asshole of the company. Lily shot out of her seat and tossed the supposed food into the trash. She threw her tray onto the stack growing by the doors and headed for the elevator. Swiping her ID, Lily slammed on the up button repeatedly until the door opened.

The ride to the fortieth floor was agonizingly slow and Lily internally cursed every single dollar that went into the construction of this building. Again, billions of dollars and they couldn’t fund a faster elevator?

The floor was almost silent when Lily stepped out of the elevator. The accounting department occupied two floors and the majority of employees were either in the cafeteria or out at lunch. She swung by Kallie’s cubicle first and swore when she found it empty.

Bathroom, maybe?

Kallie was sweet, but she was also a doormat. She wasn’t a Gotham native, but instead came from Central City after she was offered a job here. Lily’s protective streak ran a mile wide and so when she found out that Kallie wasn’t used to the rough and tumble ways of the city, she took her under her wing. Vandeer yelling at her was bound to make her cry.

Quiet voices in the hallway to the left caught her attention and Lily headed that way. She paused at the sight before her and anger flared in her chest. Bruce fucking Wayne was towering over a shaking, sobbing Kallie. Lily saw red.

She didn’t give a flying fuck if he was her boss or her boss’s boss. As far as she was concerned, he was just a rich trust fund bitch baby who was about to learn a few new insults.

“What the hell do you think you’re doing?” she snarled as she approached them. Lily placed herself directly between them and glared up at Bruce, her dark eyes flashing something fierce. He blinked in surprise and held his hands up to show his innocence. Lily jabbed her finger in his chest, her rage superseding her rationality.

“I don’t know what they teach you rich fucks at Yale and shit, but where I come from, we don’t terrorize innocent people.”

A hand tugged on the hem of her skirt and Lily looked down into the wide, tear filled eyes of her best friend. “He was helping me, Lils. It’s okay. I…I’m just not feeling that great.”

Her hand fell from where she was currently poking Bruce Wayne in the tie and Lily glanced between them. She didn’t have time to feel embarrassed before she kneeled down next to Kallie.

“What’s going on? Gloria told me about Vandeer. Is it okay if I touch you?” At Kallie’s nod, Lily started to rub her back.

“Mac broke up with me this morning and kicked me out of the apartment,” Kallie whispered. Lily’s jaw tightened and she sucked in a tight breath. She hated Kallie’s shitty boyfriend and this was a clear example why. Mac would come crawling back tomorrow, begging for Kallie to come back, and the rose-colored glasses would go right back on. Lily had been urging her to leave him for months now.

“I can key his car,” Lily offered, earning a watery laugh. “I’m not kidding.”

“Should we really be discussing you committing a felony in front of our boss?”

Lily glanced up at Mr. Wayne and found him looking at them with an almost amused smile on his lips. She shrugged and turned back to her friend. “It’s more of a misdemeanor, really.”

“Oh my god, that’s not the point.” The tears had stopped flowing and Lily grinned, wiping off some moisture from Kallie’s cheek with the edge of her sleeve.

“The breakup, Vandeer being a dick as per usual, and being homeless for the day all came bubbling up, huh?”

“Yeah. Mr. Wayne found me sitting here like an idiot trying to do my breathing exercises. It’s so stupid. I had a panic attack over work. I like my job, I swear!” Kallie’s breathing picked up again when she realized who exactly she had been interacting with.

And then Bruce fucking Wayne surprised the hell out of Lily by crouching down in his Armani suit and offering Kallie a charming smile.

“If I’m being honest…some days I don’t like work either. And it sounds like you’ve been dealt a bad hand today. Why don’t you take the rest of the day off? I’ll let Vandeer and Fox know that you’ll be gone for the day because you’re running an errand for me. Miss Amapola can be excused as well.”

Mr. Wayne reached into his pocket and extracted a wallet. He flipped it open, pulled out a crisp hundred, and handed it to Lily who grasped it gingerly, as if it might spontaneously combust when her fingers touched it.

“Use that to buy some lunch,” he explained.

“I’ll leave the change with Ernie at the front desk tomorrow morning,” Lily replied. He met her gaze with an unreadable expression in his blue eyes.

“Keep it. It’s yours to do with what you want.”

“Thank you, sir,” Kallie murmured.

“Feel better, Miss Marks. Wayne Enterprises is lucky to have you and we want to make sure you enjoy your time here.” Mr. Wayne stood and began to walk away, but Lily darted after him and grabbed his arm with the hand not currently occupied with the biggest bill she’s ever held in her life.

“I’m sorry, sir. For assuming.”

He flashed that charming, tabloid ready smile and waved her off. “It’s fine, Miss Amapola. It’s good to see that my company is protected by strong individuals.”

“I was out of line and I really hope it doesn’t reflect poorly on Mr. Fox or Kallie. I was just conc-”

“Miss Amapola.” He held her gaze and Lily felt herself freeze. There was something about his stare that locked her in place, something that didn’t exist for the cameras. “People rarely go toe to toe with me and tell me what to do.”

Her mouth went dry and Lily shut her eyes, praying that he didn’t fire her. She needed rent money for this month.

“It was refreshing and I hope you don’t start to censor yourself because of me. Sometimes I need to be put in my place.”

She opened her eyes and felt her lips curl into a hint of a smile. Mr. Wayne stepped back from her and nodded in farewell before departing for the elevator. Lily turned back to face Kallie and held out her hand for her friend to pull herself up with.

“You got some bags at your desk? C’mon, let’s grab them and you’ll stay with me for a bit. What do you want for lunch? We’re about to make somebody’s day with the size of this tip.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phillis Wheatley: The Unsung Black Poet Who Shaped the US

She is believed to be the first enslaved person and first African American to publish a book of poetry. She also forced the US to reckon with slavery's hypocrisy.

— Rediscovering America | Black History | New England | USA | North America | Tuesday February 21st, 2023 | By Robin Catalano

(Image credit: Paul Matzner/Alamy)

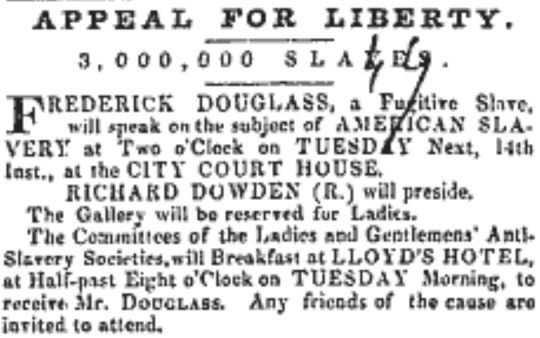

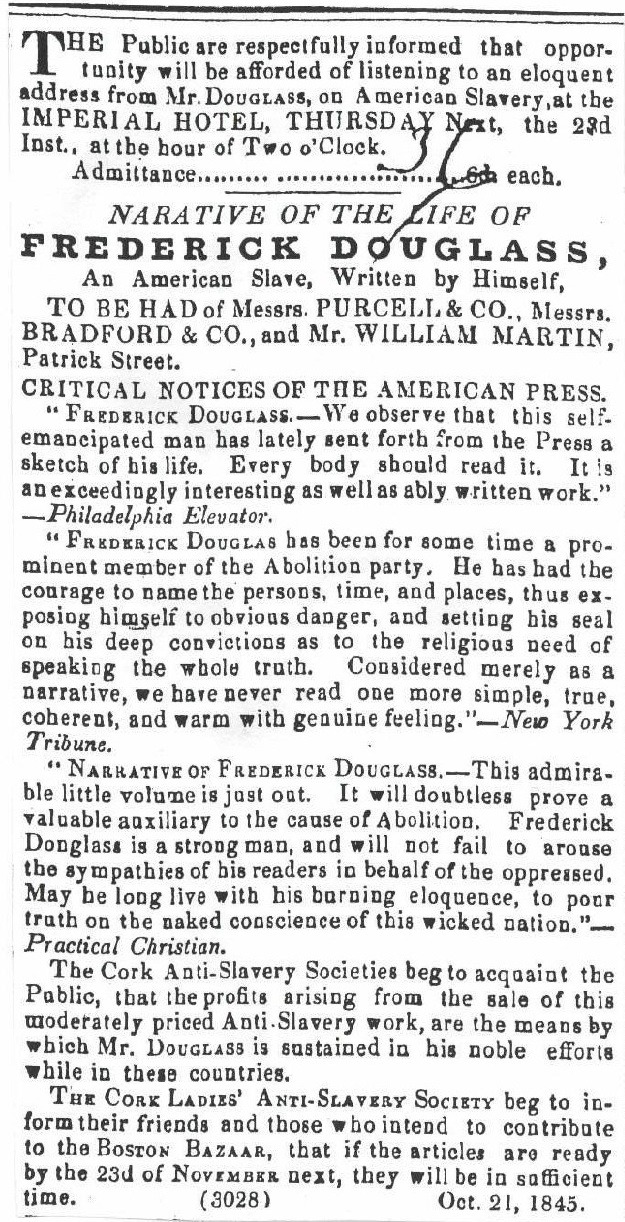

When the Dartmouth sliced through the frigid waters of Boston Harbor on 28 November 1773, the Quaker-owned whaler carried a cargo that included 114 chests of British East India Company tea. Eighteen days later, the tea, along with 228 additional trunks from the soon-to-arrive Beaverand Eleanor, would play a starring role in the US Colonies' most iconic act of resistance, which ultimately led to the Revolutionary War.

In the Dartmouth's hold was another precious cargo: freshly printed copies of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, a collection by Phillis Wheatley, the first enslaved person, first African American woman and third female in the US colonies to publish a book of poetry. Her life and work would become emblematic of the US struggle for freedom, a tale whose most visible representation – the Boston Tea Party, when American colonists protested Britain's "taxation without representation" by dumping tea into the harbour – celebrates its 250th anniversary this year.

Evan O'Brien, creative manager of the Boston Tea Party & Ships Museum, said, "Our mission, especially this year, is to talk not just about the individuals who were onboard the vessels, destroying the tea, but everyone who lived in Boston in 1773, including Phillis Wheatley."

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral is believed to be the first book of published poetry by an enslaved person in the US (Credit: SBS Eclectic Images/Alamy)

Actor Cathryn Philippe, who interprets Wheatley at the museum, connected with the poet's remarkable accomplishments. "You often hear about the tragedy of enslavement, which is a part of history that needs to be understood. But we don't hear much about the joy or successes of enslaved or formerly enslaved Africans."

Wheatley was born in what is now Senegal or Gambia and was abducted in 1761 when she was just seven or eight years old. Forced, along with 94 other Africans, aboard the slave-trading brigantine Phillis, she survived the treacherous Middle Passage, which claimed the lives of nearly two million enslaved people – including a quarter of the Phillis' "cargo" – over a 360-year period, and arrived on Boston's shores that summer.

“We Shouldn't Hesitate To Call Her A Genius”

Frail after eight weeks at sea, the girl caught the attention of wealthy merchant and tailor John Wheatley. He purchased the child as a gift for his wife, Susanna, and renamed her after the vessel that had spirited her away from her home.

Phillis showed a natural aptitude for language. David Waldstreicher, professor of history at the City University of New York and author of the forthcoming biography The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley, said, "She became fluent and culturally literate and able to write poems in English so quickly that we shouldn't hesitate to call her a genius."

Despite Wheatley's connection to the Boston Tea Party, her legacy remains largely unknown (Credit: Robin Catalano)

Although the Wheatleys were not abolitionists (they enslaved several people, and segregated Phillis from them) they recognised Phillis' talents and encouraged her to study Latin, Greek, history, theology and poetry. Inspired by the likes of Alexander Pope and Isaac Watts, she stayed up at night, writing heroic couplets and elegies to notable figures by candlelight. She published her first verse, in the Newport Mercury, at age 13.

While many New Englanders took note of the poet's gifts, no American printer would publish a book by a Black writer. Poems on Various Subjects was eventually financed by Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, and published in London. As a 19-year-old in 1773, Phillis travelled to the city, escorted by the Wheatleys' son. She was an instant sensation. Her celebrity, along with England's criticism of a new nation that simultaneously subjugated her while comparing its own relationship to the Crown as slavery, led the Wheatleys to manumit her in 1774.

A keen observer, Phillis frequently wrote about significant moments in America's fight for independence, carefully walking a fine line between being overtly political or critical of the colonial government as a Black woman. As a 14-year-old in 1768, she praised King George III in the poem To the King's Most Excellent Majesty for repealing the Stamp Act. Two years later, in On the Death of Mr. Snider Murder'd by Richardson, she memorialised the killing of 12-year-old Christopher Snider by a Massachusetts-born Loyalist during a protest over imported British goods.

Soon after, in 1770, a skirmish between Colonists and British soldiers erupted in front of the Old State House, not far from where Phillis lived on King Street, culminating in the Boston Massacre. Today, a circle of granite pavers, its bronze letters dulled by age and thousands of footsteps, marks the spot where blood was spilled. Following the incident, Phillis was inspired to write the poem On the Affray in King Street, on the Evening of the 5th of March, 1770.

The Boston Massacre took place near Phillis' residence (Credit: Ian Dagnall Computing/Alamy)

Scholars estimate that Phillis produced upwards of 100 poems. Because her work makes few references to her own condition and is often couched in Christian concepts and the extolling of popular figures of the day, she has sometimes been dismissed as a white apologist.

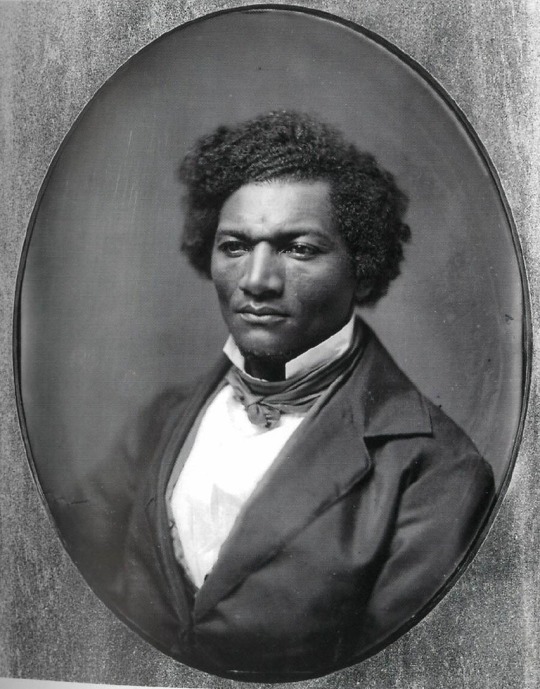

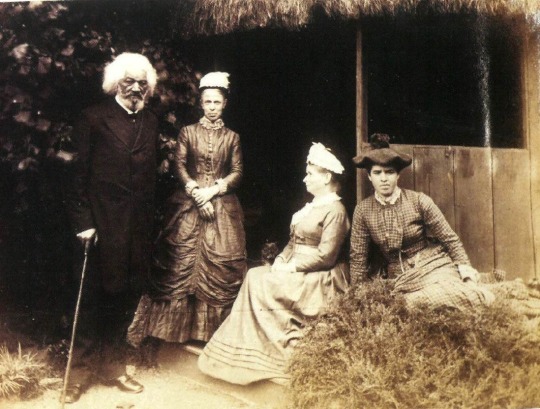

Ade Solanke, a writer and Fulbright Scholar whose play Phillis in London will be performed in Boston later this year, said, "I think the biggest misconception about her is that she wasn't an abolitionist. You think of Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, people who were explicitly condemning slavery and going to war against it. But the act of writing poetry as a Black woman in this time period was pretty radical."

Wendy Roberts, a University at Albany professor who recently discovered a lost Wheatley poem in a Quaker commonplace book in Philadelphia, agrees. "I don't think any deep reader of Wheatley comes away thinking she's an apologist. She was asserting herself, her agency, her wish for freedom, her presence as a person."

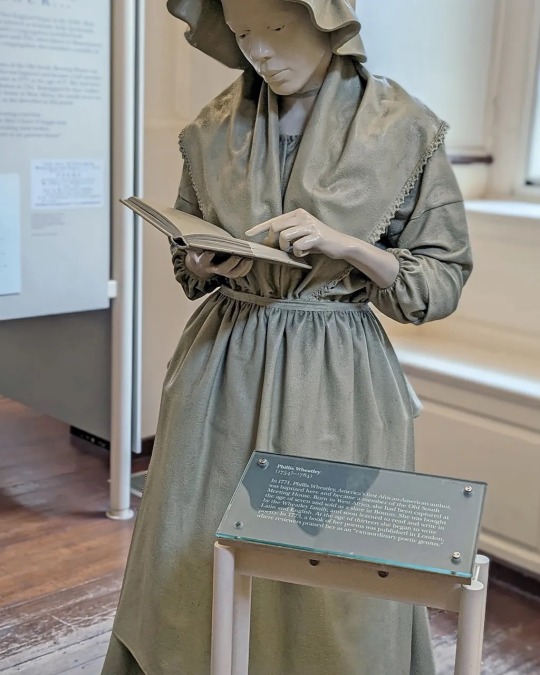

Most buildings in Boston with a direct connection to Phillis' life no longer stand. Some were razed by a pair of fires in the 18th and 19th Centuries, and others have been replaced by urban renewal in the mid-1900s. The Old South Meeting House, a stately Georgian red-brick church built in 1729 and tucked between glass-and-concrete skyscrapers on Washington Street, is an exception. Besides being Phillis's place of worship, it was a cradle of philosophical debate, and served as planning headquarters for the Boston Tea Party. It now operates as a museum, with a statue of the poet flanked by exhibits on other ground-breaking figures from the pre- and post-Revolutionary eras.

The Old South Meeting House where Phillis worshipped is one of the few buildings in Boston that remain with a connection to her life (Credit: Ian Dagnall/Alamy)

The writer almost certainly strolled through 50-acre Boston Common, the country's oldest public park (and site of the newly unveiled, and controversial, statue honouring Civil Rights icons Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King). Phillis may have conducted the Wheatley family's shopping at Faneuil Hall, once the city's main marketplace for household goods – and located next to where enslaved people were once sold. It's now a retail centre, where visitors can pick up souvenirs, sample a variety of foods, or take a tour with a guide outfitted in 18th-Century breeches, waistcoat and tricorne hat.

Some experts speculate that Phillis participated in funeral processions for Snider and the five victims of the Boston Massacre, in which their coffins were paraded from Faneuil Hall to the Granary Burying Ground – also the final resting place of Revolutionaries like Samuel Adams, John Hancock and Paul Revere. Sombre and quiet, the cemetery bears more than 2,000 slate, greenstone and marble gravestones, many carved with traditional Puritan motifs like blank-eyed death's heads and frowning angels.

Phillis, who died in poverty after developing pneumonia at age 31, is thought to be buried in an unmarked grave, with her deceased newborn child, at Copp's Hill, in Boston's North End neighbourhood. An elegant statue of her, alongside renderings of women's rights advocate Abigail Adams and abolitionist Lucy Stone, holds court over the Commonwealth Avenue Mall. This year, when a replica of the Dartmouth sails into the Boston Tea Party & Ships Museum on Griffin's Wharf, it will host a permanent exhibit on the poet.

In addition to a statue of Wheatley at the Boston Women's Memorial, a second statue of her is located inside the Old South Meeting House (Credit: Robin Catalano)

Phillis's legacy is perhaps best experienced in the work of contemporary artists. As part of the 250th anniversary celebrations, Revolution 250, a consortium of 70 organisations dedicated to exploring Revolutionary history, will host a variety of performances and exhibits, including a full-scale re-enactment of the Tea Party on 16 December. Several events will honour the poet, among them a photography exhibit by Valerie Anselme, who will recreate Phillis' frontispiece that adorned the original publication of Poems on Various Subjects.

Artist Amanda Shea, who frequently hosts spoken word events and poetry readings around the city, explained that, in many ways, she is carrying on a legacy pioneered so long ago. "I feel like I'm part of the continuum of Phillis Wheatley. It's really important to be able to write and tell our stories. It's our duty as artists to reflect the times in which we live."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

for anyone who wants to claim that jim's story was unrealistic, that nonbinary people didn't exist in the 1700s, i'd love to introduce them to one of my favourite queer icons:

the public universal friend

so the puf was born in 1752 in cumberland, rhode island. their parents were quakers, and they grew up surrounded by religon. they were quite smart, athletic, good with horses, and could quote the scripture from memory.

in 1776, at the age of 24, they fell ill and became bedridden. they nearly died but made a miraculous recovery, and insisted that their soul was taken to heaven where god sent down a new spirit, tasked with preaching his word. this spirit was named the "publick universal friend" and was entierly genderless, rejecting the women's clothes worn by their body before and refusing to respond to their old name or any gendered pronouns. they dressed androgynously or leaned to masculine styles.

many people found this strange, but for the most part, the friend was respected in terms of their prefrence. when asked if they were male or female, they would simply respond "i am that i am". in text, people would either avoid using pronouns at all with the friend or simply use "he".

they began to travel just as they had been assigned, preaching the word of god and gathering followers as they did. they did not bring a bible with them, but preached from memory, just as they did as a child. they grew a group of followers known as the "universal friends" as they traveled, which makes them the first american to found a religous community.

they beleived that anyone with free will, regardless of gender, could gain access to god's light, and they preached celibacy, though in the end they expressed the right of their followers to choose whether or not to marry or obstain from sex. they valued peace and humility to everyone, and in this they condemned slavery, urging those who followed them to free their slaves. many followers were also black.

they said that women should "obey god rather than men", and there were four dozen women amongst the universal friends known as the faithful sisterhood who remained unmarried and took on leadership roles usually reserved for men.

in 1785, the friend met sarah richards and her husband. her husband died shortly after and sarah began to live with the friend, dressing in a similar androgynous fasion and dubbing herself "sarah friend". sarah friend continued to live with the puf for the rest of her life, eventually dying and leaving her daughter in the friend's care.

at 2:25 on july 1st, 1819, at the age of 67, the friend died after a long period of illness. it's often debated on whether or not the friend would have identified as nonbinary or even trans in any fasion, but their legacy remained one of peace, tollerance, oportunity, and equality regardless of sex or race.

our flag means death takes place in 1717, and though it's before the birth of the puf, there's no doubt that gender non-conformity (or gender fuckery, if you will) has existed in some fasion for a very, very long time. i don't find the way people treat jim unrealistic for the time period at all. people love to nit-pick when it comes to history that they know nothing about.

this is only a fraction of the friend's story, so if you're interested i highly reccomend looking into it further. they were a very interesting person, and trans history is undertaught yet so, so important to know.

#sorry for the long post#i just have Feelings about the friend#and so many other trans people in history#our flag means death#ofmd#jim jimenez#the public universal friend#trans history

218 notes

·

View notes

Note

Well, I just read through the Pale Horse Thread on Alternate history while procrastinating work I need to be doing. Any other threads on there that you'd recommend?

Oh, glad you liked it!

So nothing very recent, but I did spend waaaay too much time reading this stuff when I was a teenager, so in terms of older stuff (in more or less descending order of how sure of my own recomendation I am)...

Fight and Be Right by Ed Thomas: Late 19th century UK, following the alternate career of Lord Randolph Churchill if his career wasn't derailed in a royal scandal as he remakes British politics around his new ideology of 'Tory Democracy', everything spirals well out of control from there. There's an excellent series of epilogues set in 1936 in the form of a series of interviews for FACTS magazine by Italian-American journalist 'Benny Moss'. Actually complete! Though I can't find live links to the polished pdfs and image links in the thread are mostly dead, but still one of my favorites, if only for all the truly wild bit of historical trivia in the footnotes (the world circa 1936 as described by the epilogue is also just an amazing pulp setting imo).

The Bloody Man, also by Ed Thomas: Intertwined histories of the England (sprawling to Scotland, Ireland, France, etc) and New England following Cromwell having a different sort of religious experience and emigrating to the new world, ending up as the leading figure of what in our world became Connecticut, and one of the dominant personalities of mid-17th-century New England generally. More importantly, without his leadership and influence, the English Revolution (and it's pretty indisputably a revolution this time) gets quite a bit messier, and the parliamentarian cause a good deal more radical. Also: the Quakers instead end up going by 'terrorists', the 'Salvation Army' goes down in history as a fanatical band of millenariens who cut a bloody swathe through the countryside awaiting the end time, contains the absolutely amazing line 'freedom was for all men, even Papists'.

Fear Not The Revolution, Habibi by Azander12: Asking what if Salah Jadid beat out Hafez al-Assad for control of the Syrian baathist party in 1970, leading to a much more ideological and meaningful arab nationalist state. Shit mainly hitting the fan when said state takes more than a passing interest in an alternate Black September in Jordan. Focused on Syria, Jordan and Israel in particular, and to a lesser extent the middle east in general, though there's some blowback to the superpowers as well, of course.

Male Rising, by Johnathan Edelstein: Following a nearly-successful slave revolution in Brazil, an army of ten thousand maroons and rebels are given passage to west Africa as a peace agreement (the rebellion's leader being Fulani and rather interested in going home). Unsurprisingly, this upends Sahelan politics something fierce, with effects eventually spreading throughout the world. (probably the only rec on this list to go beyond 'not dystopian' to 'actively better than real life'.

A World of Laughter, A World of Tears, by Statichaos: Taking the crack premise of 'what if Walt Disney was elected president' and gong from there (Eisenhower declines to run, gets drafted by the GOP as a complete hail mary compromise after a deadlock). Despite that very well written and tries to make everything believable - leading to something of a soft dystopia, what with having a vociferous anti-communist and strong believer in States Rights in the White House with of all Disney's eccentricities, and all.

No Spanish Civil War in 1936 by Dr. Strangelove: This one's pretty self-explanatory - the Republic's leaders are better at politics and intrigue than OTL, and Franco is bought off rather than leading the coup attempt which started the civil war otl. Spain remains a left-wing democracy as WW2 begins, and is predictably dragged into it as the nazis speed towards the Pyrenees.

A Cat of a Different Color: China After Mao by Rediv: As the name might imply, about an alternate fallout to Mao's death in 1976, specifically one where Deng Xiaoping's rise to power gets thoroughly derailed and there's quite a bit more intrigue and turmoil over the future course of Chinese politics.

All About My Brother: A Taiping Rebellion Timeline by subersivepancakes: Again, as the name might imply, about an alternate result of the Taiping Rebellion in 19th century China - specifically one that results in a partition between a Taiping Heavenly Kingdom in the south and a surviving Qing Empire in the north. More than a little bit memey, from what I recall, but more in the fun way than the eye-rolley way.

Sooo yeah, hopefully at least one of those decade-old forum threads catches your interest!

#reply#circletofcircles#alternate history#recomendations#in this essay i will#there's also a really good one about an alternate post-decolonization Somalia I can't find atm#but it died after 3 chapters so

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

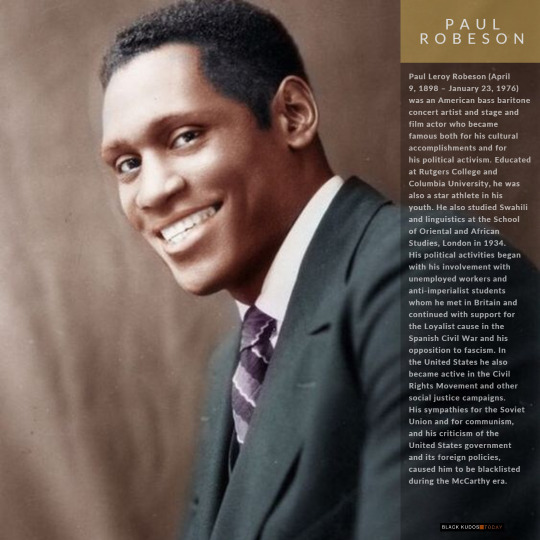

scandalous star: paul robeson - an analysis

“My father was a slave and my people died to build this country and I am going to stay here and have a part of it just like you.” - Paul Robeson

He was the man the US government tried to erase from history. From the 1920s through the early 1960s legendary bass-baritone Paul Robeson was a musical giant on the world stage but from the late 1940s he was almost unknown within his own country. He was a large man who lived a large life. He was proud to be Black and practiced and preached race pride when it wasn’t cool. He was a Renaissance man who spent most of his life fighting injustice, for which he was roundly persecuted. The son of a former slave turned preacher, Robeson attended Rutgers University, where he was an All-America football player. Upon graduating from Rutgers at the head of his class, he rejected a career as a professional athlete and instead entered Columbia University. He obtained a law degree in 1923, but, because of the lack of opportunity for blacks in the legal profession, he drifted to the stage, making a London debut in 1922. He was also a singer; a linguist, he sang songs promoting world peace and human rights in 25 languages, including Russian, Chinese and several African languages. They were often traditional spirituals or folk songs telling of struggle, resilience and survival. Part folk hero, part star of stage and screen, Robeson became an unlikely celebrity at the peak of Jim Crow and segregation; he was a 6'3" black man in a world where most people were 5'4" and most white Americans were afraid of blacks. Despite the everyday racism of the society he lived in, he was renowned for his charismatic warmth, as well as the rare beauty of his voice. It was a voice that people could feel resonating inside them and the intensely personal connection that deep sound made with an audience allowed Robeson to cross racial boundaries and be both loved and respected as a performer.

Paul Robeson, according to astrotheme, was an Aries sun and Scorpio moon (the moon is speculative). Princeton, New Jersey, Paul Robeson was the youngest of five children. His father William was a runaway slave who went on to graduate from Lincoln University and become a minister, and his mother Maria came from an abolitionist Quaker family. Robeson's family knew both hardship and the determination to rise above it. A disagreement between Robeson’s father William and white financial supporters of the church he ministered arose and he found himself ousted from the church. The loss of his position forced him to work menial jobs until he found stable parsonage at the another church. When Paul was six, his mother, who was nearly blind, died in a house fire. His own life was no less challenging. In 1915, Paul Robeson won a four-year academic scholarship to Rutgers University. Despite violence and racism from teammates, he won 15 varsity letters in sports (baseball, basketball, track) and was twice named to the All-American Football Team. He received the Phi Beta Kappa key in his junior year, belonged to the Cap & Skull Honor Society, and graduated as Valedictorian. At Columbia Law School (1919-1923), Robeson met and married Eslanda Cordoza “Essie” Goode, who was to become the first Black woman to head a pathology laboratory. He took a job with a law firm, but left when a white secretary refused to take dictation from him.

He left the practice of law to use his artistic talents in theater and music to promote African and African-American history and culture. In November 1927, his namesake son was born, Paul Robeson, Jr. He also performed in Eugene O'Neill's All God's Chillun Got Wings in London then returned to the United States to star as Brutus in the film The Emperor Jones—the first film to feature an African American in a starring role, a feat not repeated for more than two decades in the U.S. His 11 films included Body and Soul (1924), Jericho (1937), and Proud Valley (1939). Robeson's travels taught him that racism was not as virulent in Europe as in the U.S. At home, it was difficult to find restaurants that would serve him, theaters in New York would only seat Blacks in the upper balconies, and his performances were often surrounded with threats or outright harassment. In London, on the other hand, Robeson's opening night performance of Emperor Jones brought the audience to its feet with cheers for twelve encores. The success of his acting placed him in elite social circles and his ascension to fame, which was forcefully aided by Essie, had occurred at a startling pace. In London, Robeson earned international acclaim for his lead role in Othello, opposite Peggy Ashcroft as Desdemona. Essie had learned early in their marriage that Robeson had been involved in extramarital affairs, but she tolerated them. However when she found out that her husband and Ashcroft were having an affair, she decided to seek a divorce and they split up. As well as advancing the cause of black Americans, he used his music to share the cultures of other countries and to benefit the labour and social movements of his time.

Robeson became known as a citizen of the world, equally comfortable with the people of Moscow, Nairobi, and Harlem. Among his friends were future African leader Jomo Kenyatta, India's Nehru, historian Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, anarchist Emma Goldman, and writers James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway. During the 1940s, Robeson continued to perform and to speak out against racism, in support of labor, and for peace. He was a champion of working people and organized labor. He spoke and performed at strike rallies, conferences, and labor festivals worldwide. As a passionate believer in international cooperation, Robeson protested the growing Cold War and worked tirelessly for friendship and respect between the U.S. and the USSR (now modern-day Russia). In 1945, he headed an organization that challenged President Truman to support an anti-lynching law. In the late 1940s, when dissent was scarcely tolerated in the U.S., Robeson openly questioned why African Americans should fight in the army of a government that tolerated racism. Because of his outspokenness, he was accused by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) of being a Communist. Robeson saw this as an attack on the democratic rights of everyone who worked for international friendship and for equality, an accusation that nearly ended his career. Eighty of his concerts were canceled, and in 1949 two interracial outdoor concerts in Peekskill, N.Y. were attacked by racist mobs while state police stood by. Defiant, Robeson responded,

"I'm going to sing wherever the people want me to sing...and I won't be frightened by crosses burning in Peekskill or anywhere else."

In 1950, the U.S. revoked Robeson's passport, leading to an eight-year battle to resecure it and to travel again. During those years, Robeson studied Chinese, met with Albert Einstein to discuss the prospects for world peace, published his autobiography, Here I Stand, and sang at Carnegie Hall. Two major labor-related events took place during this time. In 1952 and 1953, he held two concerts at Peace Arch Park on the U.S.-Canadian border, singing to 30-40,000 people in both countries. In 1957, he made a transatlantic radiophone broadcast from New York to coal miners in Wales. In 1960, Robeson made his last concert tour to New Zealand and Australia. In ill health, Paul Robeson retired from public life in 1963. He died on January 23, 1976, at age 77, in Philadelphia.

Next, I’ll talk about a somewhat tragic and quite interesting individual that blurred the lines of race whose brilliance burned bright, but whose demons were dark: Leo Philippa Schuyler.

STATS

birthdate: August 2, 1898*

*note*: due to the absence of a birth time, this analysis will be even more speculative.

major planets:

Sun: Aries

Moon: Scorpio

Rising: unknown

Mercury: Taurus

Venus: Taurus

Mars: Pisces

Midheaven: unknown

Jupiter: Libra

Saturn: Sagittarius

Uranus: Sagittarius

Neptune: Gemini

Pluto: Gemini

Overall personality snapshot: He was a forceful individual with drive, energy and tenacity. He knew what he wanted and found ways, direct or indirect, of achieving it. But he could become torn between an impatient, up-front, naive, trusting approach to the world and a suspicious, distrustful doubt; between a self-denying, intense, slow-burning determination and a go-for-it pizzazz. When these two sides of himself worked against each other he may have found himself becoming embroiled in bitter conflicts which seem to be none of his making. Relationships fell apart, and those he thought of as friends stabbed him in the back. When he got his act together, however, he became unstoppable, a courageous, humorous, charismatic, co-operative leader, prepared to push himself to the limit and beyond in his determination to set the world to rights, and to leave his mark. People may have seen him as cynical, brash, self-assured and pushy, or as somewhat private and quietly purposeful, but none doubted his sincerity and commitment to his chosen path. Most would, however, be surprised at how much he cared about others’ good opinions. For though he wanted to make a real and lasting impact upon the world by one route or another, he especially wanted and needed the approval, appreciation and loud applause of his peers and could even brood, get bitter and self-destructive if his path is blocked, or his plans are crossed. His secret weapon, when he found it at his center, was his belief in his own abilities. This gave him a formidable will to win. Equally it gave him a great capacity to help others stand on their own two feet, and to motivate and encourage them. To bring out this creative core he needed demanding projects and ambitions to occupy his energies, especially when young.

Life for him was a drama, and self-dramatization was his forte. This drew him towards the theater or any arena, such as sports, where there was an opportunity to shine. No matter what career he followed, however, he made a career out of his life. He believed in himself and made a natural leader, but at the same time he wanted to be thought well of, and could become withdrawn and even bitter if his enthusiastic ideas met with resistance. His was a sharp, clear-headed, penetrating approach to life. He identified what he wanted to achieve and he went about achieving it with a natural gift of strategy and leadership. He had many of the qualities of the natural leader: an ability to put himself and his cause first single-mindedly; dedication; charisma; force; a talent for research, probing into hidden corners, which was excellent for military campaigning tactics and maneuvers, but also for campaigning journalism; and a gift for psychological insights and penetrating analysis. He was attracted to physical exercise and sport. If he did not consciously channel his physical, emotional and mental aggression in a purposeful way he could become very bitter, frustrated and self-destructive. He could take a real disliking to people, and could be arrogant, irascible, rude and bloody-minded. Yet he was a person of integrity. He was frank, honest and liked to tell it as he saw and felt it. This refreshing honesty kept him young and open-minded, always ready for new ideas and experiences. His forceful, sharp, biting wit and wry cynicism about human weaknesses made him an excellent humorist and comedian.

He was practical, steady and patient, but he could be inflexible in his views. One thing he did have was plenty of common sense and good powers of concentration, although he tended to think that purely abstract thought was a waste of time. His thought processes weren’t as quick as others, but his decisions were made with a lot of thought behind them. He also had a gloriously resonant speaking-voice. He knew how to make people feel at ease and instinctively knew how to resolve conflict. He was easy-going, frank and optimistic. He was quite sociable and expected other people to behave well at all times. He was eager for close personal relationships, so he tended to have a wide circle of friends. Self-indulgence could have been a problem for him, as could laziness and conceit in relationships. He was to be impatient with superficial details, preferring large-scale situations, and he disliked being tied down by obligations over which he had little control. It was often difficult for him to maintain his self-confidence and optimism, and he was easily discouraged. However, he was very intelligent. He tended to feel that there was no problem that cannot be resolved, as long as he was sufficiently informed. He could be quite cynical and fearless in his speech, but he could also be tactless. Although he was popular, periods of seclusion were necessary for him. He always tried to make sure that he was acting for the noblest of motives, and he may have had a tendency to moralize at times. However, he had a contradictory side to his nature in that whilst he accepted challenges that stretched him, he also liked to stick with the tried and true. This made his attitudes seem erratic at times.

He belonged to a generation with fiery enthusiasm for new and innovative ideas and concepts. Rejecting the past and its mistakes, he sought new ideals and people to believe in. As a member of this generation, he felt restless and adventurous, and was attracted towards foreign people, places and cultures. As a member of the Gemini Neptune generation, his restless mind pushed him to explore new intellectual fields. He loved communication and the occult and was likely also fascinated by metaphysical phenomena and astrology. As a Gemini Plutonian, he was mentally restless and willing to examine and change old doctrines, ideas and ways of thinking. As a member of this generation, he showed an enormous amount of mental vitality, originality and perception. Traditional customs and taboos were examined and rejected for newer and more original ways of doing things. As opportunities with education expanded, he questioned more and learned more. As a member of this generation, having more than one occupation at a time would not have been unusual to him.

Love/sex life: He was a doubly sensuous lover, capable of making sex both physically pleasurable and emotionally fulfilling. More importantly, he was also a very practical and grounded lover. He did not let his emotions run away with him and conducted his sex live in a reasonable and generally cautious manner. Of all the lovers of this type, he was the one most likely to make his sexual allure and emotional sensitivity work for him and not against him, revealing the true depth of his luscious sensuality only to a chosen few who, through loyalty, commitment and proven honesty, have paid the price of admission. The problems in his sexual nature were rooted less in his emotional vulnerability than in his self-indulgence. His sexual impulses were so immediate, so intense and so deeply entangled with his emotions that they tended to absorb him completely. Even though he was very sensitive to the emotional needs of others, it was nearly impossible for him to think of anyone but himself when his own sexuality was engaged. He needed to guard against letting the power of his desires drive him to unwise and selfish extremes.

minor asteroids and points:

North Node: Capricorn

Lilith: Gemini

His North Node in Capricorn dictated that he needed to develop the more caring and compassionate side to his personality and try to place less emphasis on the materialistic aspects of his life. His Lilith in Gemini ensured that he was dangerously attracted to women with a kaleidoscopic psyche who were wily, witty, and able to best anyone in a debate and weren’t above flirting, cajoling, wiring, and talking their way to the top.

elemental dominance:

fire

water

He was dynamic and passionate, with strong leadership ability. He generated enormous warmth and vibrancy. He was exciting to be around, because he was genuinely enthusiastic and usually friendly. However, he could either be harnessed into helpful energy or flame up and cause destruction. Ultimately, he chose the former. Confident and opinionated, he was fond of declarative statements such as “I will do this” or “It’s this way.” When out of control—usually because he was bored, or hadn’t been acknowledged—he was bossy, demanding, and even tyrannical. But at his best, his confidence and vision inspired others to conquer new territory in the world, in society, and in themselves. He had high sensitivity and elevation through feelings. His heart and his emotions were his driving forces, and he couldn’t do anything on earth if he didn’t feel a strong effective charge. He needed to love in order to understand, and to feel in order to take action, which caused a certain vulnerability which he should (and often did) fight against.

modality dominance:

mutable

He wasn’t particularly interested in spearheading new ventures or dealing with the day-to-day challenges of organization and management. He excelled at performing tasks and producing outcomes. He was flexible and liked to finish things. Was also likely undependable, lacking in initiative, and disorganized. Had an itchy restlessness and an unwillingness to buckle down to the task at hand. Probably had a chronic inability to commit—to a job, a relationship, or even to a set of values.

planet dominants:

Venus

Mars

Uranus

He was romantic, attractive and valued beauty, had an artistic instinct, and was sociable. He had an easy ability to create close personal relationships, for better or worse, and to form business partnerships. He was aggressive, individualistic and had a high sexual drive. He believed in action and took action. His survival instinct was strong. He wanted to take himself to the limit—and then surpass that limit, which he often did. He ultimately refused to compromise his integrity by following another’s agenda. He didn’t compare herself to other people and didn’t want to dominate or be dominated. He simply wanted to be free to follow his own path, whatever it was. He was unique and protected his individuality. He had disruptions appear in his life that brought unpleasant and unexpected surprises and he immersed herself in areas of his life in which these disruptions occurred. Change galvanized him. He was inventive, creative, and original.

sign dominants:

Taurus

Sagittarius

Aries

His stubbornness and determination kept his around for the long haul on any project or endeavour. He was incredibly patient, singular in his pursuit of goals, and determined to attain what he wanted. Although he lacked versatility, he compensated for it by enduring whatever he had to in order to get what he wanted. He enjoyed being surrounded by nice things. He liked fine art and music, and may have had considerable musical ability. He also had a talent for working with his hands—gardening, woodworking, and sculpting. He was a physically oriented individual who took pride in his body. He sought the truth, expressed it as he saw it—and didn’t care if anyone else agreed with him. He saw the large picture of any issue and couldn’t be bothered with the mundane details. He was always outspoken and likely couldn’t understand why other people weren’t as candid. After all, what was there to hide? He loved his freedom and chafed at any restrictions. He was a physically oriented individual who took pride in his body. He was bold, courageous, and resourceful. He always seemed to know what he believed, what he wanted from life, and where he was going. He could be dynamic and aggressive (sometimes, to a fault) in pursuing his goals—whatever they might be. Could be argumentative, lacked tact, and had a bad temper. On the other hand, his anger rarely lasted long, and he could be warm and loving with those he cared about.

Read more about him under the cut: