#ancient Greek ephebes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

While reading stories of Alexander & his friends, it often feels like they could very well be today's youths. Is it because the authors present Alexander's world in a way relatable to the modern reader? Or there are things about youth common in all eras, like teenage crisis, romance, dreams, bold & adventurous spirit? And if I'm not wrong, you mention at one place that you don't "heroize" Alexander. That's interesting, since he's often worshipped a mythical hero. Why did you move away from that?

Alexander and the boys

This query was really two, or at least I want to separate them into two, so I’ll address the matter of heroizing Alexander in a different post.

The reason teen Alexander feels familiar owes to the simple fact biology makes certain aspects of adolescence universal. That said, while all human beings go through (suffer?) adolescence, whether it’s recognized as a “stage of life” depends on place and era. Does X culture have an adolescent moratorium, or time period between childhood and adulthood when teens are not (yet) saddled with the full responsibilities of adulthood?

Ancient Greece did, at least for some classes; they even had a specialized term: ephebe/έφηβο��. Later, it came to signify a specific military class for training (18-20), but originally, it just meant a teenage boy, although the start age was imagined as later, more like 15+. Up to that, the generic pais (child) was more common. Ephebe has the implication of “starting to look like a man.”

Of more import, they invented what’s become the Western pedagogical system. The word pedagogy is GREEK: pais (child) agōgē (guiding/training): a paidagōgos was a nanny, but also a method of teaching children. The specific Spartan schooling system is referred to as the Agōgē, but the word has a generic meaning too. All of that is related to the Greek word for “work” (agōn) but also “to lead” (egōn).

There’s your Greek lesson for the day.

The Greeks had a pretty firm idea of the proper way to train up boys* and shape young minds. By the Classical era, and arguably the late Archaic, city Greeks were sending boys between the ages of 7 and 12 to school. These were private, so parents paid for the privilege of getting junior out of the house so somebody else could run herd on him. Mom and Dad had work to do. What were boys taught? The Three Rs (reading, writing, and ‘rithmatic) but also phys-ed (PE) and music. Again, the basics of a proper European primary-school education.

At 12, most boys returned home to take up their father’s occupation. So these were not all wealthy boys. Some were what we’d call middle class, but their families had enough money to invest in their education, and then, as now, the pricier the tuition, the better the teachers. But most stopped on the cusp of adolescence and went to work; they had no adolescent moratorium.

Only the wealthiest boys could afford to go on to what amounted to secondary education: lessons with a philosopher in order to prep them for their future careers as politicians, generals, and city leaders. What they learned now were rhetoric, eristics (art of argument), some literature, laws, theory on government, etc.

This higher-level tutoring is what Aristotle was hired for. Alexander (and friends) had already had the basics. A “philosophic education” had been around for over a century by the time Philip called Aristotle to Pella, although it wasn’t as set in form as it would become by the Hellenistic and Roman eras. In some of his more famous works, such as the Politics, Aristotle talks about the importance of education in the formation of a state: specifically in Book 7.18, and most of Book 8. He gets very specific in Book 8. He puts forward a number of common ideas the ancients had about the nature of the child. Most believed character was unchanging, so education would work to curb a person’s vices and elevate their virtues.

The Greeks, btw, did not invent schools themselves. Egyptians and Mesopotamians both had schools for children before the Greeks did. Greeks got the idea from them. But they did create their own notion of what school should include, which is what they passed down to the Romans, then to Europe, and finally, to most school systems in the West.

Anyway, when a culture introduces the adolescent moratorium, it frees up teenagers to, well, do “stupid teen shit.” Schools provide an environment where they create their own society with their own rules. In cultures where they begin adult jobs at 12/13 (or even sooner), they’re integrated and don’t have the chance to create these little sub-societies that percolate with all the drama of wildly pumping hormones.

So, a society that creates an environment where groups of teens regularly congregate in disproportionate numbers to either adults or children, like secondary school, squire/military, maid, or scribal training--or the Macedonian Pages Corps--will feel familiar to modern societies that have high schools.

Put a bunch of teens together, suffering through adolescence, and it’ll produce similar results anywhere, any time.

—————-

*Girls were obviously not included in misogynistic Greece.

#asks#alexander the great#teenagers throughout history#adolescent moratorium#ancient Greek ephebes#ancient Greek teens#Macedonian Pages#Classics#ancient Greece#Greek pedagogy#Aristotle

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

what is ephebe?

basically an old word for a suspiciously young twink of great beauty

#bjorn andresen was an ephebe. those ancient greek boys who got kidnapped by the gods were ephebes. the von gloeden boys were ephebes#robert plant wasn't an ephebe but he WAS ephebic.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

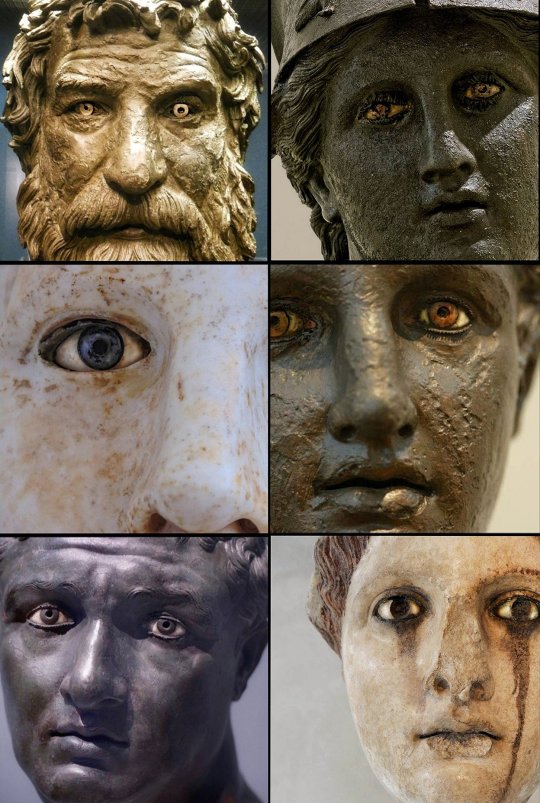

The piercing gaze of the ancient Greeks.

A collection of some famous Greek sculptures looking directly at...you

From left to right:

1) Antikythera Philosopher, 250 BCE

2) Athena of Piraeus, 4th century BCE

3) Head of Hygeia, 5th-4th cen. BCE

4) Antikythera Ephebe, 4th cent. BCE

5) Unknown man from Delos, c. 100

BCE

6) Head of a Goddess, 2nd cent. CE

📸 ArysPan

#dark academia#light academia#academia aesthetic#classical#academia#escapism#classic literature#books#books and libraries#architecture#greek#statue#sculpture#eyes#antikythera#Athena of Piraeus#Head of Hygeia#royal core#cottage core#aesthetic

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ares/Thracian "Dionysos", A cognate of Rudlos?

This is one I will add for a more personal reason, but I think he has some connections. I'll explain but bare with me and acknowledge I consider more a UPG association than anything else. Perhaps someone here will find my shot in the dark interesting.

One of the twelve Olympians, son of Zeus, god of war, battlelust, courage and civil order. He is also associated Masculinity in general and modern Hellenists/Hellenic Polytheists often share the Personal Gnosis that he is a patron of mental health and one's struggle with it.

Now first, let me lay out a few facets of Ares I consider notable to this list. Although he is sometimes depicted as a mature, bearded man, especially after his syncretization with Mars, he is also often depicted as a spear-wielding(a common symbol to the cognates of Rudlos), nude, beardless youth, an ephebe. This brings to mind the connections between the ephebes and nude fighting, and the Koryos.

He was and is often shown diametrically opposed to Athena, Goddess of strategy, craftsmanship, and wisdom. Many misconstrue this as characterizing the "strategic and humane" warfare of Athena to the "savage and cruel" warfare of Ares. This could not be more wrong, as we have many stories of Athena encouraging, well, warcrimes, and Ares respecting another's honor.

The more accurate dichotomy is a much older, pan Indo-European one. One of defensive vs aggressive warfare. I have written earlier about the idea that Rudlos was the god of aggressive war, the marauding Koryos, counter-posed to the defensive Perkwunos, who protects the people and village from such raiders, and humanity at large from the demons of chaos, like Wṛ́tros. It is also widely accepted that Athena was formed from lesser, individual cults of palace goddesses, patrons of the individual homes of rulers, and later the cities they ruled, who later melded together into the panhellenic Athena, who likely takes her name from Athens and not the other way around as myth relates to us.

The crux of my theory is that rather than be actually being descended from the original PIE gods associated with these two forms of war, Ares and Athena sort of stepped into the molds they left behind, Ares particularly so.

The etymology of the name Ares is traditionally connected with the Greek word ἀρή (arē), the Ionic form of the Doric ἀρά (ara), "bane, ruin, curse, imprecation". Walter Burkert notes that "Ares is apparently an ancient abstract noun meaning throng of battle, war." Beekes has suggested a non-IE, Pre-Greek origin of the name. The earliest attested form of the name is the Mycenaean 𐀀𐀩, a-re.

The epithet, Areios ("warlike") was frequently appended to the names of other gods when they took on a warrior aspect or became involved in warfare: Zeus Areios, Athena Areia, even Aphrodite Areia ("Aphrodite within Ares" or "feminine Ares"), who was warlike, fully armored and armed, partnered with Athena in Sparta, and represented at Kythira's temple to Aphrodite Urania. In the Iliad, the word ares is used as a common noun synonymous with "battle."

He was also known by the name/epithet Enyalius. In Mycenaean times Ares and Enyalius were considered separate deities. Enyalius is often seen as the God of soldiers and warriors from Ares' cult. It has been suggested that the name of Enyalius ultimately represents an Anatolian loanword, although an alternative hypotheses treat it as an inherited Indo-European compound. The meaning is still unknown however.

Now, while it is indeed possible that Ares was a Pre-Greek(or perhaps even foreign) deity adopted by the Greeks, his character lines up closely with the IE idea of deified abstractions. The PIE's believed that if any idea exists, their must be a god who rules over it. In the absence of assigning it to a previously worshiped deity, they would deify the abstraction itself, this is the origin of the PIE god Xaryomen, Roman Fortuna, the various female night personifications throughout the IE world(Nyx, Nott, etc), among many others.

However there are two issues. First, his name is not IE in origin. It's seemingly a common noun, one widely adopted by IE people but still strange nonetheless. The second is his breadth of myth and variety of cultic practice, which is extremely strange for a supposed abstraction. For example, in parts of Anatolia, he had an oracular cult.

Consider his mythic origin for a moment. His birthplace was said to be Thrace, and he was believed by the Greeks to be the progenitor of their people. There is no well known obvious cognate of Ares is Thrace, so it is likely an association made by the Greeks because of the Thracian's martial skill and perceived warlike nature. However the cult of a Thracian god referred to as "Dionysus" was very widespread. Most believe him to be a separate deity. His connections to prophecy, poetry, war, and his identification with Apollon could indicate some connection to Rudlos, but his association with a solar cult feels potentially contradictory, at the very least could go either way because Apollonian influence and Rudlos-Dyeus identification in neighboring Anatolia.

Okay, enough rambling, let's get to personal, 100% UPG crackpot theory. When the IE Greeks encountered the Pre-Greek, Anatolian, and Minoan cultures, we know they adapted much of their culture and religion. Consequently, many IE deities were lost or altered beyond recognition. Rudlos's cult started to disappear before the Mycenaean age, and was then re-adopted/altered via Anatolian Apollon. During Rudlos's initial disintegration, most of his war-related aspects may have jumped ship and been given over to a newly formed/adopted deity, Ares/Enyalius. His aspect/son Leudhero may have influenced Dionysus in a similar manner.

To be clear, we will not considered Ares a cognate of Rudlos moving forward but I thought I would give you something I've been pondering while I continue to work on the next parts for the Rtkona series.

#paganism#deity worship#pagan#pagan revivalism#pie paganism#pie pantheon#pie polytheism#pie reconstructionism#pie religion#proto indo european paganism#hellenism#hellenic polytheism#hellenic deities#hellenic worship#helpol#ares#rudlos#reconstructionist paganism

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The myth of Apollo (4)

As with Dionysos previously (see here), the Dictionnary of Literary Myths of Pierre Brunel offers two different articles about Apollo. Here is the loose (but free !) translation of the second one, « Apollon, the mythical sun ».

APOLLO, THE MYTHICAL SUN

Pontus of Tyard wrote in 1552: “Of all the poetic gods, Apollo is the one that has been the most disguised by the fables and the etymologies of his name.” The mythical figure of Apollo, which has been turned in Western literature as one of the most conventional figures there can be, was considered by ancient mythographers as an extremely complex character, because he was given many names and many properties. Apollo is first and foremost an universal archetype of the Divine, of which literature kept – alternatively as much as indiscriminately – three main names: Apollo(n), Phoebus, Sun. The chronological evolution of the god allows us to isolate and separate the solar god (as a symbol) from his mythological adventures, since the solar Apollo is more present within poetry than within legends.

I/ The names of the Sun

In the Platonic tradition, all the way to the end of the Renaissance, numerous significant and diverse etymologies were invented for Apollo, all reflecting the various functions of the solar god. Within the name Apollo(n), interprets can read as much an idea of destruction as an idea of freeing (from the verb “luô”, to untie) or purification (from the verb “louô”, to clean). This reflects the “drying” effects of the sun, which can be negative or positive – and thus is a survival of the ambiguity of the archaic god.

The interpretations found within the “Cratylus” (see the previous part of “The myth of Apollo”, “The Antique Apollo) allow us to define the four main attributes of the god: medicine, divination (both seen as manifestations of “purification”), music and the art of shooting with a bow. The name Phoebus has been associated by Isidor of Sevilla with the endless youth of the ephebe (e-phoebus), while Cartari (in 1556) linked it to the vital light (phôs, light, bios, vie). For Platon, the name of “Sun” within Ancient Greek meant he who “nuances” the colors (“helios”, the sun in Greek, derived from “aïoleïn”, to nuance) ; and all the ulterior commentators assimilated it with the Latin “Sol”, tied to the adjective “Solus” (the sole, the unique, the lonely), a link which can be found in the neo-Latin languages (in French “soleil” and “seul”, for example). Cartari, who was follow the works of Plotin and Macrobe, linked this precise etymology to the Greek name of Apollo that he translated as “he who is not multiple” (“a” as a privative + “polu”, many) – highlighting again the important idea of unity within the idea of the sun-god.

II/ Main attributes

The mythographers of Renaissance made a very useful synthesis work that offers us in their roughly definitive state the various interpretations of the myth of Apollo, compiling together the commentaries from Antiquity, the interpretations from the Middle-Ages, as well as the point of view of some Oriental civilizations. Within his “Images of the Gods” (1556), Cartari divides the solar myth in a series of elements linked together as part of a long allegorical chain:

1) The sun represents at first, in the diversity and universality of its effects, an archetype of the Divinity. The Assyrians assimilated it to Jupiter as the soul of the world (because through all the other gods, it was always him who was evoked). As such Macrobe noted in his “Saturnals” that all theology always returned to the worship of the sun.

2) As a symbol of eternal youth, as the allegory of the always-new day, of the always-resurrecting light, Apollo is depicted as beardless (except for the Assyrians) and is associated with Dionysos.

3) Because of its central position within the Universe, it is called “heart of the heaven”, by analogy with the vital function of this “pulsing” organ within the human body. The sun is the source of light that communicates their movements to the other astral bodies. It is why Apollo is sitting in the middle of the nine Muses, allegories of the nine celestial sepheres, and with them he embodies the Harmony and the Universe, as a symbol of “symmetry and concordance” (according to Tyard). As such the Music of the Spheres, that R. Lulle will represent through the “Great Lyre of the Universe”, is reflected in Apollon’s association with Music and Poetry (Poetry which was originally simply the art of singing).

4) The rays of the sun are depicted by the arrows of Apollo (just like by those of his sister Diana). They can penetrate the very core of the earth – it is why there is an archaic tradition according to which Apollo is a chthonian or infernal god (and can sometimes be called Hecate, since the primitive gods were without genders).

5) It is due to the purgative and drying effects of his rays that Apollo is also the god of medicine. Mythographers tie this function of the god to the fable of the snake Python killed by Apollo soon after his birth: they assimilated Python to the mythical Flood, as a principal of morbid humidity wrapped around the earth.

6) The attribution of the laurel to Apollo, and the fable of Daphne, are explained by the medicinal virtue of the plant, the always-green plant that never rots, and that the mythographers saw as a symbol of Health. The laurel is also tied to the alchemical symbolism of Humidity, because Daphne was metamorphosed thanks to the intervention of her father, a river-god.

7) Finally, Apollo is the god of divination, because he is the eye of the sky, he sees all and he reveals all secrets (hence why in mythology Apollo was the one who denounced the adulterine love of Venus and Mars). He has the role, within the Universe, of the eye within the human body – he is the “spy of the intellect”, the “censor” or the “rector”, and his eminent position makes him a sign of omnipotence. Cartari described a hieroglyph that designated the sun as a scepter surmounted by an eye – which would identify the mythical sun with the idea of royalty.

Such a synthesis – within which each of the god’s main attributes were defined and linked together – as the interpretative model which was used as a basis for all ulterior poetry. For example take Du Bartas: in his “Sepmaine ou Création du Monde », in 1578, the sun, which is not a god anymore but a mere « ornament of the sky », is always designated by metonymy through a series of names that resume all the attributes of the solar god in his cosmic function: Phoebus with gold hair, the blond Titan, the Torch of Laton, the Archer, Apollo giver-of-souls, the Fountain of Heat, the Life of the Universe, Giver-of-honors, King of the Sky, Eye of the Day, Censor, Torch of Delph, Torch of Delos, he who “makes the face of the world young again”. In a parallel way, from Cartari’s work, the different aspects of the character will be slowly simplified until he simply becomes the god of Poetry, crowned with both sunrays and laurel leaves, sitting among the Muses on top of mount Parnassus, always holding his lyre (which can sometimes represent him in his entirety), distilling the poetic inspiration under the shape of the Hippocrene spring (created from Pegasus’ hoof), a spring that Ronsard will describe as “the fountain of verses”.

III/ The philosophical Sun

Symbol of the Philosophical Gold in the alchemical tradition, uniting the fundamental opposites that are the fire and the water, the dry and the wet ; or a symbol of the divine creative soul within Orphism and Pythagorism, the go of Poetry s the very image of all creation within the Neoplatonic literature, in which Apollo with his lyre is always associated to his “mortal double”, Orpheus. Within the Renaissance, Apollo was the god who inspired the “Poetic Fury”, without which the lyrical production cannot be: it is under his influence that (according to Ronsard’s Hymn to Autumn) the spirit can “penetrate the secret of the heavens” and the soul “rise among the gods”. It is under the sign of Apollo that the soul finds back its celestial origin through the effects of the divine enthusiasm (from the Greek “theos”, god): this is the Orphic origin of poetry. For Ronsard and the poets of La Pléiade, the “inspired Poet” is both the “prophet” and the “priest” of Apollo (hence why in the 16th century it was believed that the Sibyls and the oracles were exceptional poets).

This Neoplatonic interpretation of the myth, which confuses the two main attributes of the god, prediction and lyrical art, this same tradition that shaped the image of Apollo we have today, relies on the commentary by Marsile Ficin of “The Symposium”, which divines four different divine “furies”, associated with four patron-deities. First is the highest, the poetic fury, which is caused by the Muses ; second is the “mystery fury” or the sacerdotal fury, which proceeds from Dionysos ; third is the prophetic fury, given by Apollo ; fourth is love, and it originates from Venus. Despite the distinction marked within this text between the Muses and Apollo, poets usually invoke indifferently one or the other – the god understood as the “universal principle” and the Muses as allegories that represent the individual repartitions of the poetic virtues. It should be noted that within the Neoplatonic context, Apollo is not opposed to Dionysos – rather their functions are complementary. The god of divination, who is also the god of the penetration of divine secrets, forms a couple with the god who initiates humans to the divine Mysteries ; it is to the point that they are called “brothers” by Pontus of Tyard, who explains the epithet of “Delphic Apollo” by a fake etymology “adelphos”, “brother”, for the “fraternity considered between Denys (Dionysos) and Apollo”.

For the Neoplatonicians, if Apollo is one of the poles of the duality of the world, he is rather opposed as the One, as the universal principle, to Diana, who embodies Nature – that is to say the Multiple. According to the Platonic idea taken back by Giordano Bruno in “Eroici Furori” (1585), the Nature (Diane) is the mirror of the God (Apollo). Apollo is the absolute light whose essence must be hidden, who blinds and kills those that see it directly, and thus he can only be perceived through his reflection. A variation of this idea, developed by Léon Hébreu in 1535) made Apollo the “simulacrum of the divine Intellect”, while the Moon was the “simulacrum of the soul of the World” and acted as an intermediary between the divine plane (the intelligible world) and the corporal plane (the sensible world). This conception has been very influential in term of literary posterity, because it means in a very explicit way, that the sight is a sense that must be valorized: the sensitive vision, the one of the eye, is to be identified with the intellectual vision, the one that allows thanks to the spirituality of the light to distinguish the beautiful from the ugly and the good from the evil. The supremacy of the eye above all other senses will be abundantly developed, in poetic and metaphorical ways, from the 16th to the 17th centuries. Even within the anatomical descriptions of the baroque poets, the eye appears as an intermediary between the sensible and intelligible world, as a double of the Sun, whose light shines upon the minds as much as upon the bodies.

#the myth of apollo#apollo#phoebus#greek mythology#poetry#renaissance#greek gods#sun#symbols#symbolism of the sun#solar myth#roman mythology#diana#dionysos#symbolism

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zeus: god of thunder and the sky. He is considered the ruler, protector, and father of all gods and humans.

Hera: goddess of marriage, family, childbirth, and woman. She was the wife and sister of Zeus, and many of her most famous myths center around her jealous retributions to Zeus's infidelity.

Poseidon: god of the sea (and water in general), earthquakes, and horses. He was one of the most powerful gods in ancient Greek mythology, Poseidon was held responsible for earthquakes, rivers, floods, droughts, and anything involving water in general.

Demeter: goddess of harvest and agriculture. This was a hugely important role, which gave her the power to sustain life through the growth of all plants and grains, particularly cereal grains.

Ares: god of war and more properly the spirit of battle. He represented the distasteful aspects of brutal warfare and slaughter. Ares was noted for his beauty and courage, qualities which no doubt helped him win the affections of the Greek goddess Aphrodite.

Athena: goddess of wisdom, craft, and warfare. In wars where she was most commonly depicted, Athena embodied cold rationality, tactics, and strategy. Athena's cold logic stood in direct contrast to her brother Ares' rage, violence, and impulsiveness.

Apollo: god of archery, music and dance, truth and prophecy, healing and diseases, the sun and light, poetry, and more. One of the most important and complex of the Greek gods, he is the son of Zeus and Leto, and the twin brother of Artemis, goddess of the hunt. He is considered to be the most beautiful god and is represented as the ideal of the Kouros (ephebe, or a beardless, athletic youth).

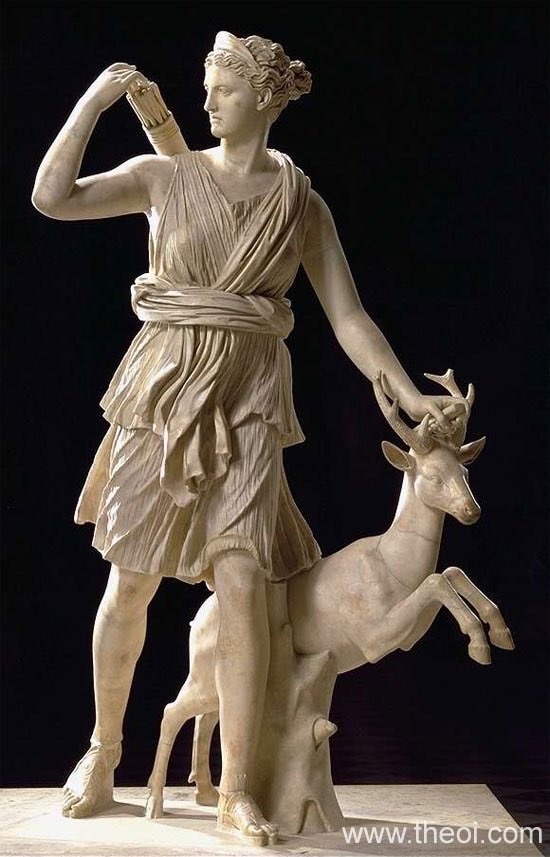

Artemis: goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, nature, vegetation, childbirth, care of children, and chastity. Artemis was very protective of her purity and gave grave punishment to any man who attempted to dishonor her in any form. Like all the Greek Olympic gods, Artemis was immortal and very powerful. Her special powers included perfect aim with the bow and arrow, the ability to turn herself and others into animals, healing, disease, and control of nature.

Hephaestus: god of artisans, blacksmiths, carpenters, craftsmen, fire, metallurgy, metalworking, sculpture, and volcanos. In Greek mythology, Hephaestus was either the son of Zeus and Hera or he was Hera's parthenogenous child. He was cast off Mount Olympus by his mother Hera because of his lameness, the result of a congenital impairment; or in another account, by Zeus for protecting Hera from his advances (in which case his lameness would have been the result of his fall rather than the reason for it).

Aphrodite: goddess of love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, procreation, desire, sex, fertility, prosperity, and victory. Florence

Aphrodite is usually said to have been born near her chief center of worship, Paphos, on the island of Cyprus, which is why she is sometimes called "Cyprian", especially in the poetic works of Sappho. The Sanctuary of Aphrodite Paphia, marking her birthplace, was a place of pilgrimage in the ancient world for centuries.

Hermes: god of boundaries, roads, travelers, thieves athletes, shephards, commerce, speed, cunning, wit, and messages. Hermes was considered the messenger of the Olympic gods. According to legend, he was the son of Zeus, king of Mount Olympus, and Maia, a nymph. As time went on, he was also associated with luck, shepherds, athletes, thieves, and merchants.

Dionysus: god of wine making, orchards and fruit, fertility, festivity insanity, tuition insanity, religious ecstacy, and theatre. The son of an immortal god and a mortal princess, Dionysus’ role forged a crucial link between humanity and the divine, serving as a force of cyclical, unbridled nature who drew men and women out of themselves through intoxication. In that sense, Dionysus, a genial but wild and dangerously ravishing intermediary, represents one of the enduring mysteries and paradoxes of life.

#percy jackon and the olympians#percy pjo#percy jackson#percy series#percy jackson books#pjo season 1#pjo spoilers#pjo fandom#pjo series#pjo tv show#pjo#pjo percy#pjo annabeth#pjo grover#grover pjo#polls on tumblr#fandom polls#tumblr polls#my polls#polls#tumblr poll#poll#fandom#fandom poll

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is Ganymede's age ever said in any of the ancient texts? I've heard people say he's 12-13 without any sources to back that up

Generally, not really.

In most Greek sources where he's mentioned, it's usually his name and "son" (of whoever he's imagined to be son of, as this varies, but usually and in the oldest sources, Tros). At best you're sometimes gonna get the "youth" designation; meirakion/ephebe, or even a more general "spring-tide/flowering time".

Even if "child", that is, pais, is used, it doesn't really mean Ganymede would be imagined to be pre-pubescent.

Pais can be used as an endearment for a teenager, or even a general descriptor of someone who's not considered an adult (that is ~21 and older) yet. The meirakion "age-bracket" was somewhere between mid-teens to 20/21. In the Aeneid, when at one point a scene with him on a cloak is described, "puer" is used. Generally translated as "boy" (but, male slaves would be called this their whole lives, because they are not considered to be real/adult men at any point), the word-tool/dictionary attached to Perseus tells me the word applies to (citizen) boys generally up to seventeen.

The thing is, of course, that Ganymede is considered the ~exemplary~ youth and eromenos in Greek myth and cultural thought.

A youth was suitable to be an eromenos as long as he hadn't gotten facial hair (the first down of it marked the beginning of the downfall, so to speak, but there's a lot of lyricism to that whole moment). In reality, facial hair can be real slow to appear, but generally, again, what the Greek sensibility for this was that things stopped being proper at around 20-21 at most (with citizen youths, I have to point out. Slaves are free game whether boys or men). The poet Strato/n, somewhere in the early centuries post-0, has a poem where the end point is seventeen ("it is not mine to seek, but rather Zeus'"), and that anyone looking for a youth older than this is looking for someone who can take his turn in fucking, basically. The lower age of what's "acceptable" is, however, floating, and probably very much depended on whether the individual was free or slave, etc.

Visual art has Ganymede depicted what's probably meant to indicate somewhere between younger teens to older teenager. Though even when he's as tall as Zeus, he's usually portrayed more slender than athletic youths of equivalent age.

As for absolutely anything that implies a younger Ganymede in text, Lucian's Dialogue of the Gods has a conversation between Zeus and Ganymede where Ganymede is very clearly 12-13 at most. Probably even younger, by the way he talks.

Lucian, however, is a satirist. Most of his stuff must definitely be looked at with that in mind. On the other hand, in Roman times it seems like it was acceptable to use slave boys that young and even much younger. And the Warren Cup as what's been called a "Greek" side and a "Roman" side. The Greek side has a young man who's very clearly upper teens at the very least having sex with an older, bearded man. The Roman side has what's equally clearly a rather young boy in the arms of a clean-shaven older man.

Anyway, my personal opinion is if you use Lucian's Dialogue (cited or uncited as these people do) as your only jumping-off point on insisting that Ganymede is absolutely and only ever intended to be 12-13, you're wrong.

Not that you can't say he is that young, if that's the shock value you want to go for. And not like, if your interpretation of Zeus and Ganymede's relationship is nothing but sexual assault, that it would be "better" even if Ganymede was imagined to be 17-20.

But mostly the point is that no, there's no solid age for Ganymede set anywhere. More a sliding scale of possibility, that probably leans more towards the mid-older teens than younger, in general.

#asks#ganymede#greek myth thoughts#and if anyone's thinking about being unpleasant about Zeus and Ganymede on this post#perhaps just don't :)#since I do ship them

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taylor's Albatross...

It's Harry 😭

One must read the poem, Rime of the Ancient Mariner from beginning to end to fully comprehend this concept.

She carries his metaphorical weight on her shoulders.

The pictures are a reflection of each other. The sheep representing Taylor.

Harry's laurel wreath crown, is a nod to the Greek god, Apollo. The laurel wreath, traces back to Ancient Greece. In Greek mythology, the god Apollo, who is patron of lyrical poetry, musical performance and skill-based athletics.

Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, music and dance, truth and prophecy, healing and diseases, the Sun and light, poetry, and more.

He is the son of Zeus and Leto, and the twin brother of Artemis, goddess of the hunt. He is considered to be the most beautiful god and is represented as the ideal of the kouros (ephebe, or a beardless, athletic youth)

Ok, so now we know that Apollo is tied to a twin, named Artemis.

Artemis is the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, nature, vegetation, childbirth, care of children, and chastity. In later times, she was identified with Selene, the personification of the Moon. She was often said to roam the forests and mountains, attended by her entourage of nymphs. The goddess Diana is her Roman equivalent.

Now where did we see Artemis recently, oh yes, that's right...as Diana of Ephesus at The Tortured Poets Spotify Popup. We might have full circle moment right here....

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ancient Greek city-state known as ecclesia was renowned for its strict military code of conduct and tactical advantage. Its military structure was specifically designed to defend its citizens and their way of life from outside threats, while at the same time protecting the city-state's own interests. This structure has been used as a model for many different militaries throughout history, and continues to be a source of inspiration today.

Ecclesia's military system was based on a division of responsibilities between a select group of citizens, known as ephebes. These ephebes were responsible for training warriors, and were highly regarded for their abilities in tactical strategies. In addition to this,all citizens were expected to take part in military training on a regular basis and to pledge their allegiance to the city-state. This commitment to defending the city-state had two main advantages: first, it created a strong sense of unity amongst the population; second, it allowed for the quick deployment of large numbers of well-trained warriors when needed.

The military system in ecclesia also had several other important elements. Warriors were expected to act in accordance with a strict code of conduct, which was enforced both on and off the battlefield. The city-state also established a clear chain of command, which helped ensure orders were followed swiftly and efficiently. Additionally, the ephebes were given high degrees of authority in order to provide clear direction to their troops in the field.

It is this legacy of military discipline and strategy that has made ecclesia an ideal model for many militaries. In modern times, the US Marine Corps, the French Army, and the UK Army have all adopted elements of ecclesia's military structure and code of conduct. Modern militaries are still guided by the same principles of efficiency, loyalty, and tactical advantage that guided the city-state two thousand years ago.

0 notes

Text

After receiving your comment @leetlesapphiretiefling I went down a rabbit hole and researched the topic.

According to a paper I read (I will screenshot the goddamn link at the bottom of the post because tumblr is being a butt right now and won’t let me insert the link in any way shape or form and I’m about to toss whole thing out the window okay??), a male around the age of 20 to 21 years old would have just left the ephebes stage, the age at which an adolescent was expected to join the military for two years, and, while not considered an “accomplished adult” (pg 2, second column) would legally be a citizen. They would then commit themselves to academic learning from older men until they married around the age of 30, where they’d be considered a full adult.

Of course, this is based on Athen’s law and was not necessarily the standard for mythological Ithaca, and it certainly doesn’t appear to be the standard used in Epic specifically. According to cut songs, Odysseus was 13 when he became king of Ithaca, which is not something that was likely to happen in that time period. Though, tangential side note here, considering that in the Iliad, Pyrrhus (son of Achilles) was around 12 to 13 when he fought in the Trojan war and brutally slaughtered people and apparently took women as his concubines, Greek mythology doesn’t seem opposed to preteens acting like adults. In which case, Telemachus should have been considered an adult.

Regardless of Greek myth shenanigans though, based on Ancient Greek customs, Telemachus would not have been considered an adolescent (teenager) or a child. I was wrong in previously stating he’d have been considered a full adult. He would have been a young man as stated in the paper’s introduction. But there was still a difference between adolescence and young man.

As @starmachine2000 stated in a reblog just now, the reason the fandom collectively seems to treat him as a child is because Legendary portrays him as childish. This does not mean he actually is one though.

Behold. The aforementioned asshole link.

There were a few other articles that said about the same thing with minor difference, but I had so many problems trying to get ONE link down that I’m done trying to be fancy for the day. Maybe I’ll come back with the others. Maybe not. Who knows ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Why does everyone keep saying Telemachus is a teenager? That he’s just a kid??

I’m honestly?? Baffled?

The man is at least 20 years old??

All I can find on Telemachus’ age before Odysseus left for war is that he was an infant. Google’s shit though so maybe there’s an exact age listed somewhere that I’m just not finding in my cursory search. I did however see a few people claim he was two when Odysseus left and to be fair, “infant” is an unclear term. I personally wouldn’t assume an infant was two—I’d guess under a year old—but technically speaking “under the legal age of majority” is a valid definition.

Odysseus was gone about 20 years as stated in the original Odyssey and Epic the musical. Telemachus says so himself in Legendary that it’s been 20 years.

Telemachus, as stated previously, is around 20 years old, possibly older given the vagueness of “infant”.

Odysseus was king of Ithaca and headed off to war about that age. Telemachus is not a child.

I know Epic portrays Telemachus as being a kid, but he is a grown adult. In fact, a good chunk of the original story is about Telemachus searching for his father by going on his own voyage. Odysseus’ journey home is actually told as a story later on in the books by Odysseus after escaping Calypso.

#I’d have reblogged off of starmachine’s post but I’d already typed the entire reblog when they posted and I was not copying and pasting#epic the wisdom saga#telemachus#epic the musical#epic telemachus#epic fandom#epic odysseus

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

I did a re-watch of Mission: Impossible last night with a really old DVD. The image quality was like a potato and my TV stretches all DVD images, but Brian de Palma is so great that once you get into it, it doesn't matter anymore.

Tom had *far* more chemistry with Kristin Scott Thomas than with Emmanuelle Beart.

And when I watched the beginning, I just felt that there was so much thematic overlap between the team and the vibe of the squad in The Secret History before Richard came into the picture. I read this article on culty workplaces and culty environments; the cult leader designs the work to take up so much of your time that you can't socialize or make connections outside of it AND sleeping around within the group is very encouraged. And it's obvious that Jim Phelps created such an environment, with himself as the leader, king, and mentor.

..when you think about it, Ethan, it was inevitable..no more Cold War. No more secrets you keep from everyone but yourself, operations you answer to no one but yourself. Then one morning you wake up and find out the President of the United States is running the country - without your permission. The son-of-a- bitch! How dare he? You realize it's over, you're an obsolete piece of hardware not worth upgrading, you've got a lousy marriage and sixty-two grand a year.

He's so much like Julian, they both have an inflated self-image and grandiose notions of being the ultimate holder of power. And if Jim is the Julian-figure, then Ethan is Henry. The star student whose relationship with Julian is the holy of the holies in the web of relations that binds the group, and everyone outside looks at it only from their peripheral vision because to stare directly might be dangerous or feel like you're intruding on something private. But its the relationship that sets the tone and ground for every other relationship in the movie.

And like, Julian and Henry are interesting because Henry is (for all the textual evidence) straight and only interested in Camilla, but Julian is the deepest longest-lived (?) relationship that he has. And yeah, the two of them were LARPing the whole ancient Greek older man/younger ephebe relationship because they feel that the only way to live meaningfully is to live like an ancient Greek aristocrat/philosopher king. tl;dr-->Jim has groomed Ethan to be his idealized lover and student, but Ethan has more natural feeling for Claire.

no more Cold War. No more secrets you keep from everyone but yourself, operations you answer to no one but yourself.

Jim lived for secrets and for being what is now known as the Deep State. Unelected, unnoticed, wielding absolute power.

And Hannah has the sadness of the one who is always left out of the team orgies.

1 note

·

View note

Note

do we have any idea of what hephaistion actually looked like??

Hephaistion’s Image

I finally have access to my books again, so tackling this much-delayed query. The short answer, unfortunately, is…

We haven’t got a bloody clue what he looked like.

Curtius tells us he was larger in physique/taller than Alexander, and nice-looking (3.12.16), but in a manly way (7.9.19). Lysippos and Philon both made portraits of him, and Aetion painted him into his “Marriage of Alexander and Roxane.” After his death, other Hetairoi at court commissioned portraits of him to please Alexander. None of these images survive.*

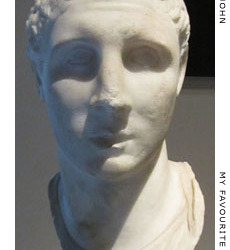

We have just ONE named statue of him, originally from Pella, now in the Thessaloniki Museum (photo mine). Even though it’s labeled, it’s a generic image. It’s not what he looked like. All other statues called “Hephaistion” are guesswork.

The difficulty with ancient portraiture is that, too often, busts/statues don’t come down to us labeled. If enough do, we can create a “portraiture tradition,” which means certain distinguishing features became standardized across (virtually) all images, allowing us to identify an individual. Then we can look at unlabeled statues/busts and say, “Yeah, that’s ___.” **

Another problem is the tendency for Greek sculptors to make shit up. Recall that at certain points in history, portraiture didn’t exist. Nobody making busts of, say, Homer knew what he’d looked like. All those statues labeled “Homer”? That’s just what later sculptors thought he ought to have looked like, down to the closed “blind” eyes. Folks, we’re not even sure Homer was blind! This mythologizing is related to another tendency in Greek sculpture called “idealizing.”

So, some quick art-history terminology … we have three basic ways of talking about people in ancient sculpture: idealized (and mythologized), a portrait, and a likeness. The latter two are not the same. A portrait means a recognizable person (those standardized features), but it may differ according to workshop style or be partly idealized. (The Akropolis head of Alexander below is partly idealized; it’s Alexander “prettied-up.”) By contrast a likeness looks like the person, warts and all. Portraiture was FAR more popular. It’s no different from the various filters you can apply to photos today before posting them on social media. A likeness is the plain image the camera takes before you “fix” it.

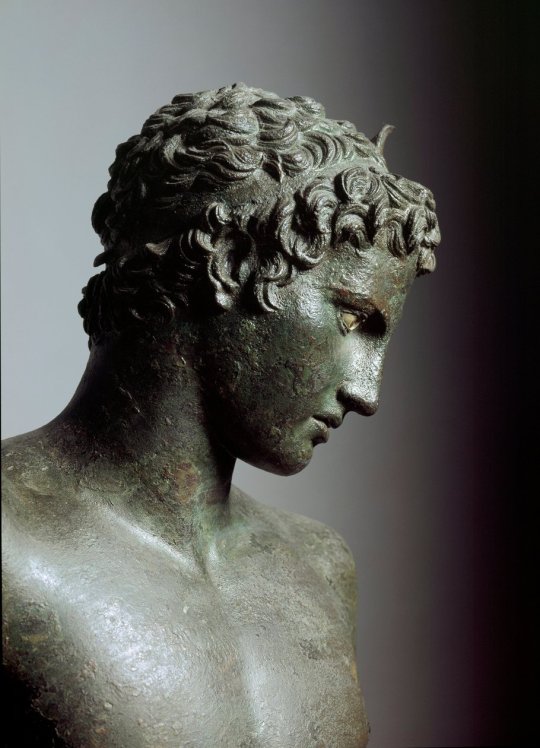

By the Archaic period into Classical Greece, we see a drive towards accuracy in anatomy, but aiming for what they considered physical perfection. They’d use Olympic (or other contest) victors to model (male) bodies, and the face would be a generic ideal young man (ephebe). This will be oval with smooth cheeks, a round chin, straight nose, small bow mouth and high, smooth forehead with level, almond eyes. The hair is tightly coiled and close to the skull.

This ideal ephebe is the ancient version of a male model. If you walk around the National Museum in Athens, you’ll see dozens of faces just like it, especially on the gods. Btw, it wouldn’t photograph that well—features aren’t sharp enough—which is why our modern canons of beauty have morphed a bit.

Art historians (or even just those of us who’ve spent decades looking at these statues) are decent at picking out these “generic” faces. I’m giving you a few below, so you can see. The first is Hermes, the second the Marathon boy, and the third is the Getty head of “Hephaistion.” This is why we say that’s not a portrait.+

Now, go back and look at the image of “Hephaistion” on the dedication bas-relief above. You’ll see why we say it’s generic ephebe-style. To understand why, it’s important to know how these stone-carving workshops operated.

It takes time to make these. So, if you want a tombstone or dedicatory plaque, you don’t walk in and order one from scratch to be delivered next week … or even next month. For something wholly original, it takes months, and you’re expected to pay accordingly. Only the very wealthy can afford individualized portraits or statue groups. By very wealthy I don’t mean the ancient equivalent of “He drives a jaguar and lives in a gated community.” I mean the ancient equivalent of “He has chauffeurs and lives on ten acres with private security.” See the difference?

Workshops kept a stock of pre-cut stones for shoppers to choose from. These were what most people purchased. A nice, high-end figured gravestone is still one of these standard images. They’d have them for hoplites, young mothers, girls, teen boys, etc. etc. So also with dedicatory plaques (as ours for Hephaistion). These also had certain typical elements, like a horse (recalling Hero the Horseman, a common figure in Thracian and Macedonian art), or the pattela plate in the woman’s hand for an offering, etc. Buyers would visit a workshop to see what they could afford. It would then be personalized with an inscription. Only the wealthiest could afford to personalize an image.

Our dedicatory statue (SEG 40: 547) has an inscription that reads, “Diogenes, to the Hero Hephaistion.” That’s kind of short, suggesting the purchaser didn’t have oodles to spend. I find two other things interesting on this statue, other than the quality, which is good if not super-exceptional. First, I note that the spelling of his name is Attic, not Doric. I explain why this matters in my article “Becoming Macedonian.” The other interesting thing is the fact the dedication comes from a man…but it’s a woman on the statue making an offering. Maybe this is meant to be Diogenes’s wife or mother, but it’s one reason I think it a pre-made statue. If it were personalized, we’d see Diogenes, not Ye Generic Matron.

Another clue is the date: between 330-320, but it MUST be on the lower end as Hephaistion died late in 324 and wasn’t declared a hero until just before Alexander’s own death in mid-323. Assume travel time for news to spread and we’re looking at very late 323/early 322 or later (the dating of the stone could be off a bit). Nor was Hephaistion standing there as a model. Ergo, the purchaser chose a generic ephebe.++ And no, we have no idea who Diogenes was. Not the cynic philosopher (who died in 323 in Corinth, around the same date as Alexander, supposedly).

So, we’ve no statue we can securely call Hephaistion that’s even a portrait, never mind a likeness.

A few other statues are commonly tagged “Hephaistion,” one from Kyme (top) and another from Alexandria (bottom). Both are paired with an Alexander, but the faces of the two Hephaistions don’t look alike. One (Kyme) has a long face, big nose, very down-slanted brows, and small flat ears; the other (Alexandria) has a small nose, oval face, even eyes, and big flaring ears. If you look at the Alexander found with each, you can detect the workshop styles, and if the Alexanders do show identifying features associated with his portraiture, the Hephaistions do not. In fact, the Alexandrian statue is sometimes labeled “Demetrio,” as its identification is disputed.

Just pairing a statue with Alexander does not an Hephaistion make. 😉

The Alexander Sarcophagus from Sidon presents a different sort of problem. The middle male figure on horseback on the long-side battle scene, and the figure on horseback behind the lion on the other long side have both been identified as Hephaistion. But that identification depends on the sarcophagus belonging to Abdalonymus, who, according to some stories, got his position as King of Sidon from Hephaistion. The Alexanders on the sarcophagus are easy to spot, but off to the side. A Persian figure is centered, as is this other Greek male. If it IS Abdalonymus’s sarcophagus, Hephaistion would be a good guess. But Mardonius has also been reasonably proposed as the sarcophagus owner, in which case, that’s probably not Hephaistion.

Even if it is Hephaistion…we have the same problem. It’s a very generic ephebe face. (It would have been made years after Hephaistion was in Sidon, btw.)

A few other images out there have been proposed, but largely argued down. I still like the oversized bronze head from the Prado Museum. It’s more clearly somebody’s portrait, and it’s the one I had in mind when I went looking for a model for the (old, original) cover of Dancing with the Lion. But it’s been more securely tagged as Demetrios Poliorketes. One big problem is that, not only is it unlabeled, we don’t even know where it was found. A number of statues are purchased in the back allies of Istanbul or Thessaloniki or Rome or… (you get the idea).

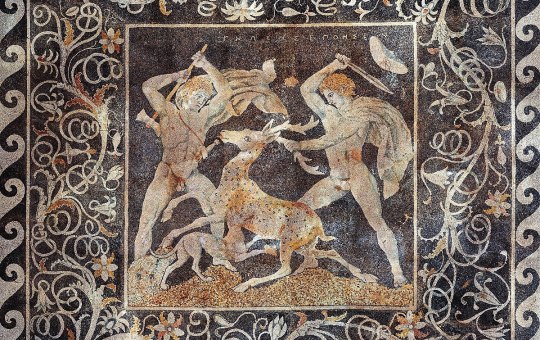

I’ll address a final image that’s been more recently proposed: the non-Alexander figure (below, left) in the stag-hunt mosaic from the House of the Abduction of Helen, in Pella. It’s possibly from the same workshop as the lion-hunt mosaic from the House of Dionysos (second below). That lion-hunt mosaic is Alexander and Krateros, which identification is about 95% secure. Why? We’re told about a bronze group dedicated at Delphi that’s this very scene, completed by Krateros’s son for his father in honor of a specific event from Alexander’s campaigns. Copies of a famous work made in other mediums are remarkably common. In fact, I’d bet the “House of Dionysos” in Pella belonged to Krateros the younger, or that family anyway. It dates to exactly the right period.

Now, the stag-hunt mosaic is in a different house, but there are links in style between the two Alexanders (e.g., the petasos). The non-Alexander figures kinda resemble each other, but less clearly. (No, the axe in left stag-hunt guy's hand is not associated with Hephaistos. It is associated with a Thracian god, Zalmoxis.) Is stag-hunt guy a second Krateros? More likely it’s meant to be the owner of the house. Given their placement and size, those houses would have belonged to Very Important People. E.g., Hetairoi families. And everybody wanted a piece of the king—like taking a selfie with celebrities today.

Once more, just because Alexander appears with another person in a group, you cannot leap to the conclusion that person is Hephaistion.

So, that’s a fast survey of images tagged “Hephaistion,” and why I say none of them shows us what he may actually have looked like.

This took a while to assemble everything.

(For more information on some [not all] of these, see Andrew Stewart, Faces of Power: Alexander’s Image and Hellenistic Politics, U-Cal Press, Berkeley, 1993, 453-55.)

————

* The painting today called “The Wedding of Alexander and Roxane” by Sodoma in the Roman Villa Farnesina is a much, much later (1517 CE) re-imagining of what Aetion’s painting may have looked like. The ancient painting is long gone.

** For Alexander, his portraiture includes the anastole (cowlick), round chin, heavy brow, strong nose, “melting” gaze, and (often) tilted head and longer-than-average wavy hair like a lion’s mane. I can spot an Alexander anywhere. Ha. I was once in the Capitoline Museum, just idling along, when way down the aisle I spotted him, over 50 yards away. It was a heavy, Romanized style, but it was Alexander!

+ Both heads (his and Alexander) are forgeries anyway. Forgeries are BIG business in antiquities. Needless to say, museums don’t like to admit when they’ve bought a forgery, so you’ll next-to-never see one labeled as such. Gotta read the art history assessments to find out. If museums are convinced, they usually just quietly remove it.

++ Sometimes people ask me why one of these idealized ephebes couldn’t be what Hephaistion did look like, as he was supposed to be attractive? Well, it’s possible, but even very pretty people who we can tag as a portrait — I give you Antonoös — have distinguishing features. You can tell an Antinoös from a generic ephebe. Also, we have enough labeled portraits of Antinoös to create a portraiture tradition. We don’t have that with Hephaistion. So even if some generic statue currently labeled an ephebe were to be Hephaistion, we have zero way to know.

#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#Hephaistion in art#Hephaestion in art#Alexander the Great#Art history and Alexander the Great#idealization in Greek art#Classics#Classical art history#Alexander the Great's image#ephebes in Greek art#ancient portraiture#ancient greece#alexander x hephaestion#tagamemnon#asks

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

i thought ephebe was a younger guy being trained in the military & an eromenos was the barely legal/not quite legal twink. like i know theres overlap (+ eromenos is in the context of pederastry) but i feel like im missing something. am i missing something?

that IS pretty much the original meaning of the words in the ancient greek context! however the word ephebe has remained in the culture and shifted semantically to mean a gorgeous youthful illegal twink for centuries, whereas the word eromenos has mostly fallen out of fashion (maybe because it implies a specific sexual context/dynamic or because it has no indication of youth in its direct translation as opposed to ephebe?). so that's the context and meaning with which i call my beautiful skinny boygirls ephebes

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Food and Faith." The Rape of Tamar, Part 1. From 2 Samuel 13.

Tamar is the "Tallest, most fruitful date palm" which represents the Free Market Economy in Judaism.

The noun תמר (tamar) means palm tree but it's not immediately clear from what verb it comes, and thus how the ancients saw the palm tree — in the Bible all trees (oaks, figs, olives, and so on) relate to certain aspects of the wisdom tradition.

Female judge Deborah had her seat under a palm tree, which seems to suggest that the palm tree related to a kind of popular court.

Noun תמר (tomer) also means palm tree but secondarily refers to a kind of sign post or pillar. Nouns תמרה (timora) and תימרה (timara) refer to palm-like artistic expressions; the first word describes an image of a palm tree and the second a palm-like pillar.

Since the word "palm-like" does not necessarily mean to look like a palm, but merely to imitate some kind of signature quality of the palm, it's debated what a palm-like item might actually be.

It appears that the palm tree reminded the ancients of a social focal point that was spontaneously and organically established (rather than by some decree or violence or trickery).

A palm is like paths that form in an open field with a well at the center, or it's like the effects of a free market, which drives society to unknown heights that no single trader could have imagined.

What does it mean to rape the free market? 2 Samuel was written around 550 BCE, when the Jews and Greeks were starting to mix and read and write and think together. The concept of democracy, the free market, class warfare were emerging as critical topics in academia and public practice.

The Greeks contended with these ideas using strange stories. While the stories of the Jews were certainly strange too, they contained one element missing in the rest: all the characters are human. The rape of Ganumede by Zeus, for example, commentary for and against sex with ephebes is an example. "Zeus did it, so why not?".

The story certainly changes when the gods are absent and the rape takes place between a brother and a sister as we will see. Even still, as with the Greek versions of such things, alas, this one is not meant to be taken literally:

13 Now David’s son Absalom had a beautiful sister named Tamar. And Amnon, her half brother, fell desperately in love with her.

2 Amnon became so obsessed with Tamar that he became ill. She was a virgin, and Amnon thought he could never have her.

3 But Amnon had a very crafty friend—his cousin Jonadab. He was the son of David’s brother Shimea.[a] 4 One day Jonadab said to Amnon, “What’s the trouble? Why should the son of a king look so dejected morning after morning?”

So Amnon told him, “I am in love with Tamar, my brother Absalom’s sister.”

5 “Well,” Jonadab said, “I’ll tell you what to do. Go back to bed and pretend you are ill. When your father comes to see you, ask him to let Tamar come and prepare some food for you. Tell him you’ll feel better if she prepares it as you watch and feeds you with her own hands.”

6 So Amnon lay down and pretended to be sick. And when the king came to see him, Amnon asked him, “Please let my sister Tamar come and cook my favorite dish[b] as I watch. Then I can eat it from her own hands.”

7 So David agreed and sent Tamar to Amnon’s house to prepare some food for him.

In Judaism, familial relationships have symbolic meaning stemming from Adam and Eve. Men are commitments, females are habits. When they are both noble in purpose, a genealogy is formed.

The entire purpose of Judaism is one unbroken genealogy of nobility from Adam onward in faith, subtely, reality, personally and globally. If Adam and Eve make something good together, so will Cain and Abel, etc. except we know this is a process that is not without hazards. Abel was an idiot, Cain was a genius. They fought and Cain won.

To outwit the sibling that is not worthy and succeed is how the genealogy is built. The Torah emphasizes this process of elimination between siblings quite a lot. It is continued by God and the Synagogue, which together produce lots of little bouncing baby Jews.

Here, the siblings are not brothers, they are brother and sister and the competition, the survival of the fittest is decided by trickery and a rape.

What is a rape in Judaism before we get all messed up about it? The rape of a man or woman in the Torah refers to the loss of that person's voice by force. Ancient Greeks and Jews differed on this a great deal. Women in Greek culture were nothing. Oppression of women was usual and customary, there were few restrictions regarding the mistreatment of women.

The Torah and the Mishnah however, all speak of compensation and lashes in some case as punishment for the rape. What is really supposed to happen, however is the oppression that allowed the rapist to silence the other woman's or man's voice has to be lifted.

Rape in the Torah and Tanakh refer more to the pre-existing conditions of the rape than the rape itself. The Mishnah says "This...shall not enter your mind."

So the story of the Rape of Tamar seems to be about a pattern of abuse in society that originates in the Court of the King as a thought rather than an act. Let us see what kind of thought that is and how it pertains to silencing the voice of the Free Market:

v. 1. David= persistent beauty

son Absalom= "father of peace"

Tamar= the open market

Amnon= faith

"Faith in the open market leads to persistent beauty."

v. 2. the Gematria value is 846, חדו, heydo, "lively, able to speak."

Amnon, faith, therefore felt as if it was not going to find its voice and lusted for the Marketplace.

=Free Speech

v. 3.

Jonadab= to volunteer

The verb נדב (nadab) means to give, donate or volunteer, and by implication to be noble. From it derive the noun נדבה (nedaba), freewill offering, the noun and adjective נדיב (nadib), generous or noble, and the noun נדיבה (nediba), generous deed.

Shimea=to report, but this could mean rumors as much as free speech

Amnon is a prince, and what do they do besides act like shmucks? Princes are supposed to descend into the depths of human suffering on behalf of the people and emerge victorious. Princes are supposed to be the heroes of the people. The King is in charge, the Prince is the lifeblood of the kingdom. Princes represent humanity's most intense and profound fantasy.

This one, Amnon, faith, however is having a few problems.

v. 4. The value is 11146, קיאםו, kiamo, "because of the burden"

The substantive כי (ki), expresses "a temporal, causal, or objective relationship among clauses expressed or unexpressed" (in the elegant words of HAW Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament). It's used more than 4,000 times in the Old Testament and can most often be translated with "that" or "in that (= because)" or "in that (= when)".

Both the verbs עמש ('amas) and עמס ('amas) mean to load or carry a load. Noun מעמסה (ma'amasa) means load or burden.

"The burden of the Prince is always Mashiach. The Free Market and the burden of Mashiach on humanity are one and the same."

v.5. Food is always the impetus for one's conduct. If one consumes the Torah, one's conduct for example, is expected to be non-violent. The appetite for non-violence feeds the habit for consuming the Torah and then the food and the appetite reciprocate in creating the energy needed for the ongoing effort to curb violence.

The value for v. 5 is 11151, קיאהא, kiaha, "the cause for a fellow member of a social economic node (a "house") within a broader economic whole."

Faith in the government and the market is not enough, there needs to be a cause. What is the cause?

v. 6-7, the value is 10008, י'ח, Eighteen. 18 is the numerical value of the Hebrew word "chai" which means "life." It is a Jewish custom to give monetary gifts in increments of 18, thus symbolically blessing the recipient of the gift with a good long life.

So if we want to have faith, we need free speech, we need a voice and a marketplace for it. The reason we would create such a thing is to bless humanity with a long and blessed, violence and oppression free way of life.

More on the Rape of Tamar to follow.

#christianity#christian broadcasting network#christian living#christian doctrine#christian faith#youtube

0 notes

Text

OP inspired me to get this off my chest-

I don’t like these portrayals of Thanatos of him as this uber pretty boy/eboy (lookin at you Hades game) or some figure that cares about appealing to mortals and their sentimentalities at their death. Thanatos is Death in its pure form. Neutral. I feel like these versions of him as super nice are taking the “gentle” death too literally. To Ancient Greeks, Thanatos is ultimately unpleasant, because Death as they know it is unpleasant. Euripides’ Alcestis have Thanatos contrast Apollo by him being a haggard figure with dark robes. The earliest art we have of Thanatos is him being a bearded mature looking man. The ephebic boy version of him only showed up in later or Roman art. The Orphic Hymn calls his influence (as death) as his “all-destructive rage”. He is described similarly to Hades to be unsympathetic to mortals: “hated most by mortals”.

This woobie/innocent meow meow romanticizing reminds me of how Hades is made overly soft to the point where nothing about his character is remotely recognizable of how the Ancient Greeks saw him.

Personally, it’s just really annoying cause to me this kind of extreme, along with the other side of villaination of death gods, makes both of them so less interesting than they can potentially be.

Side note: Thanatos vampirically drinking blood of dead beasts is metal af.

Every time I see Thanatos depicted as an woobie or an innocent meow meow I remember that one moment from Euripides' Alcetis where Heracles says about him, and I quote: "I think I shall find him drinking the blood of slaughtered beasts beside the grave."

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

The myth of Dionysos (7)

I covered before two articles of the "Dictionary of Literary Myths". Here I bring you another loose translation of a thorough article covering Dionysos' legend, myth and god-self. However this time, it is an article coming from Félix Guirand's "General Mythology". It is a bit of an old article - originally written in 1937 - so some elements might be lacking or outdated, but Guirand's book and studied stayed a very influential and referential work when it came to mythology studies for a very long time, up to the early 21st century, so there is a legitimate interest to put it alongside other Dionysos articles throughout this series.

In the section about Greek mythology, Félix Guirand classifies Dionysos right after Demeter among the "earth gods" and "agragrian deities".

I/ Traits and attributes

Dionysos (etymologically speaking, the “Zeus of Nysa” seems, by analogies of his attributes and legends, to be the Greek version of the Vedic god “Soma”. His cult seems to have been born in Thrace: brought to Boeotia by settling Thracian tribes, it was then carried to the island of Naxos by Boeotian colonizers, before it finally started spreading over the entire archipelago, before returning to the continental Greece – first in the Attic region, and later in the Peloponnese. The character that was the primitive Dionysos complexified itself by borrowing traits from foreign deities – most notably the Cretan Zagreus, the Phrygian Sabazios, and the Lydian Bassareus. As such, Dionysos kept gaining new domains and powers as his characterization grew. It seems that Dionysos was originally simply a god of wine. From the spirit of wine, he became a god of vegetation and hot humidity, and from this point he evolved into the god of pleasures, then into the god of civilization, and finally, according to the Orphic traditions, he reached his apex as a manifestation of the supreme deity.

II/ Cult and depictions

Dionysos was honored throughout all of Greece, but the nature of his festivities and holidays varied depending on the regions and eras. One of his most ancient celebrations was the Agrionia, that came from Boeotia (most specifically Orchomenos): in its primitive form, the Bacchants killed a young boy in honor of the god. Human sacrifices were also practiced at Chios and Lesbos – they were however replaced by ritual flagellation. In the Attic region, it was the rural Dionysia that were celebrated: in December it was the Lenaea, holidays of the wine press, when the god was offered the first products of the wine-season. Then, at the end of February, came the Anthesteria, or “flowery celebrations”, that lasted three days during which the wine of the last harvest was tasted – in the Lenoeon sanctuary a procession was organized, followed by a sacrifice offered by the wife of the archon-king, and concluded by the offering of boiled seeds to both Dionysos and Hermes. The most famed and renowned celebrations of Dionysos were however the Great Dionysia, or urban Dionysia, at the beginning of March. It was during this festival that theater plays were organized. These nobles and respectful ceremonies were coupled with orgy-like celebrations all throughout Greece – such as the orgiastic celebrations on the slopes of the Cithaeron.

The physical appearance of Dionysos changed as his legend was modified. He first appeared in the same of a mature, bearded, middle-aged man wearing a crown of ivy. Then he became an effeminate and beardless ephebe, sometimes half-naked, barely covered by a “nebride” (a panther’s pelt or fawn skin), other times wearing a long dress identical to those worn by women. His head, which sported long curly hair, was crowned with vine and grapes – he was holding in one hand a thyrsus, and in the other either grapes or a drinking cup.

(Here I cut off parts III and IV of the article - I'll post them separately)

V/ Foreign deities associated with Dionysos

This exuberant wealth of legends is explained not only by the great popularity of the god, but also by the fact that Dionysos’ personality (as said previously) absorbed several foreign deities. Three in particular: the Phrygian Sabazios, the Lydian Bassareus and the Cretan Zagreus.

Sabazios, who was the supreme god of the Hellespontic Thrace, was a solar god from Phrygia. Very diverse traditions surrounded him: sometimes he was the son of Kronos, other times the son and lover of Cybele. His wife was either the lunar goddess Bendis, either Cotys/Cottyto, an earth-goddess similar to the Phrygian Cybele. Sabazios was depicted with horns, and the snake was his sacred animal. He was celebrated through nocturnal orgies. When later Sabazios was assimilated to Dionysos, the legends of the two gods intertwined. Some said that Sabazios has placed Dionysos within his thigh before entrusting him to the nymph Hippa ; others claimed that it was the opposite way and that Sabazios was Dionysos’ son. It is because of these parallels and links fome between the two that ultimately Dionysos’ native land was considered to be the Hellespontic Thrace.

Sometimes the Bacchants were called the “Bassarids/Bassarides”, and Dionysos himself sometimes wore the epithet “Bassarios” when he wore a long dress of Oriental style. One theory, presented by the lexicography Hesychios, was that it was a reference to the fox-skins the Bacchants used as clothing ; but another theory rather proposes the reading of these names as an allusion to an Oriental god absorbed by Dionysos. In Lydia, there was a god similar to the Phrygian Sabazios. This god was worshipped at Tmôlos, the same place where (according to the Orphico-Thracian tradition), Sabazios gave a child-Dionysos to Hippa. The Tmôlos later became one of Dionysos’ favorite residences. If this theory is correct, what was the name of this Lydian god? The hypothesis is that it might have been Bassareus – this Bassareus might have been a conquering deity, and it is because of him that the “far-reaching conquests” of Dionysos might have entered his legend. It was also probably because of Bassareus existence that Dionysos became involved in the legend of Aphrodite and Adonis, and maybe it was even because of this Bassareus that the legend of Ampelos came to be – this very beautiful young man that Dionysos was in love with, but who was killed by a wild bull he tried to tame. Dionysos, full of sorrow, asked the gods to turn Ampelos into vine.

As for Zagreus… Zagreus very probably started out as the Cretan equivalent of the Hellenistic Zeus, but under the influence of the Orphic mysticism he was identified with Dionysos, and this resulted in a new element of the Dionysos legend: Dionysos’ passion (in the Christian sense). Here is what was told about the Zagreus-Dionysos: He was the son of Zeus, and of either Demeter or Kore. The other gods were jealous of him, and thus conspired against him. He was ripped to pieces by the Titans, that then boiled his dismembered corpse. However Pallas saved the heart of the god: she brought it to Zeus, who destroyed the Titans with his thunderbolt, and from the still-beating heart he had Dionysos be born. As for Zagreus, whose remains were buried at the foot of the Parnassus, he became a chtonian deity qui, in the Underworld, welcomed the souls of the dead and helped their purification. To these sufferings and this resurrection, the adepts of the Orphism gave a mystical meaning/reading, and this deeply changed the character of Dionysos. He stopped being this rustic god of wine and joy that had descended from the mountains of Thrace – he even lost his trait as the “god of orgies and madness that came from the Orient”, no, this new Orphic Dionysos was, to take back Plutarch’s words, “the god who was destroyed, the god who disappears, the god who abandons life and then is reborn” – aka, a symbol of universal life.

As such, it is no surprise to see that in the Mysteries of Eleusis Dionysos was associated with Demeter and Kore ; because, like them, he embodied one of the great powers of fecundity in the world.

37 notes

·

View notes