#amotz zahavi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“These findings were later echoed by the renowned French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu in his 1979 book Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste.

In his body of work, Bourdieu described how “distance from necessity” characterized the affluent classes. In fact, Bourdieu coined the term “cultural capital.”

Once our basic physical and material needs are met, people can then spend more time cultivating what Bourdieu called the “dispositions of mind and body” in the form of intricate and expensive tastes and habits that the upper classes use to obtain distinction.

Corresponding with these sociological observations, the biologist Amotz Zahavi proposed that animals evolve certain displays, traits, and behaviors because they are so physically costly.

(…)

So for humans, top hats and designer handbags are costly signals of economic capacities; for gazelles, stotting is a costly signal of physical capacities.

Veblen, Bourdieu and Zahavi all claimed that humans—or animals—flaunt certain symbols, communicate in specific ways, and adopt costly means of expressing themselves, in order to obtain distinction from the masses.

Animals do this physically.

And affluent humans often do it economically and culturally, with their status symbols.

A difference, though, is that human signals often trickle to the rest of society, which weakens the power of the signal. Once a signal is adopted by the masses, the affluent abandon it.

(…)

The yearning for distinction is the key motive here.

And in order to convert economic capital into cultural capital, it must be publicly visible.

But distinction encompasses not only clothing or food or rituals. It also extends to ideas and beliefs and causes.

In his book WASPS: The Splendors and Miseries of an American Aristocracy, the author Michael Knox Beran examined the lives and habits of upper-class Americans from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century.

He writes that “WASPS” had mixed feelings about their fellow citizens.

These upper-crust Americans viewed ordinary Americans as “sunk in moronic darkness” and that “It is a question whether a high WASP ever supported a fashionable cause without some secret knowledge that the cause was abhorred by the vulgarians.”

This still goes on today.

In the past, people displayed their membership in the upper class with their material accoutrements.

But today, because material goods have become a noisier signal of one’s social position and economic resources, the affluent have decoupled social status from goods, and re-attached it to beliefs.

The upper class craves distinction.

(…)

A 2020 study titled “The possession of high status strengthens the status motive” led by Cameron Anderson at UC Berkeley found that relative to lower-class individuals, upper-class individuals have a greater desire for wealth and status.

In other words, high-status people desire wealth and status more than anyone else.

(…)

Expressing a luxury belief is a manifestation of cultural capital, a signal of one’s fortunate economic circumstances.

There are other examples of luxury beliefs as well, such as the downplaying of individual agency in shaping life outcomes.

A 2019 study led by Joseph Daniels at Marquette University was published in the journal of Applied Economics Letters.

They found that individuals with higher income or a higher social status were the most likely to say that success results from luck and connections rather than hard work, while low-income individuals were more likely to say success comes from hard work and individual effort.

Well, which belief is more likely to be true?

Plenty of research indicates that compared with an external locus of control, an internal locus of control is associated with better academic, economic, health, and relationship outcomes. Believing you are responsible for your life’s direction rather than external forces appears to be beneficial.

Here’s the late Stanford psychology professor Albert Bandura. His vast body of research showed that belief in personal agency, or what he described as “self-efficacy,” has powerful positive effects on life outcomes.

Undermining self-efficacy will have little effect on the rich and educated, but will have pronounced effects for the less fortunate.

It’s also generally instructive to see what affluent people tell their kids. And what seems to happen is that affluent people often broadcast how they owe their success to luck. But then they tell their own children about the importance of hard work and individual effort.

(…)

When I was growing up in foster homes, or making minimum wage as a dishwasher, or serving in the military, I never heard words like “cultural appropriation” or “gendered” or “heteronormative.”

Working class people could not tell you what these terms mean. But if you visit an elite university, you’ll find plenty of affluent people who will eagerly explain them to you.

When people express unusual beliefs that are at odds with conventional opinion, like defunding the police or downplaying hard work, or using peculiar vocabulary, often what they are really saying is, “I was educated at a top university” or “I have the means and time to acquire these esoteric ideas.”

Only the affluent can learn these things because ordinary people have real problems to worry about.

To this extent, Pierre Bourdieu in The Forms of Capital wrote, “The best measure of cultural capital is undoubtedly the amount of time devoted to acquiring it.”

The chief purpose of luxury beliefs is to indicate evidence of the believer’s social class and education.

Members of the luxury belief class promote these ideas because it advances their social standing and because they know that the adoption of these policies or beliefs will cost them less than others.

(…)

Why are affluent people more susceptible to luxury beliefs? They can afford it. And they care the most about status.

In short, luxury beliefs are the new status symbols.

They are honest indicators of one’s social position, one’s level of wealth, where one was educated, and how much leisure time they have to adopt these fashionable beliefs.

And just as many luxury goods often start with the rich but eventually become available to everyone, so it is with luxury beliefs.

But unlike luxury goods, luxury beliefs can have long term detrimental effects for the poor and working class. However costly these beliefs are for the rich, they often inflict even greater costs on everyone else.”

#henderson#rob henderson#luxury beliefs#luxury#psychology#bourdieu#pierre bourdieu#veblen#thorstein veblen#zahavi#amotz zahavi#beran#michael knox beran#class#status#status symbols#peacock

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Rob Henderson

Published: Jun 12, 2022

Let’s start with a question: What do top hats and “defund the police” have in common?

Before we explore it, I’ll very briefly tell you about my unusual background. Currently, I’m a doctoral candidate in psychology at Cambridge and a faculty fellow at the University of Austin. And before this, I studied psychology at Yale as an undergraduate. But before entering these universities, my life was a lot different. I was born into poverty and grew up in foster homes in Los Angeles and all around California. I fled as soon as I could at age 17, enlisting in the military right after high school.

I then attended Yale on the GI Bill. That was a very different environment for me. At Yale, there are more students from families in the top 1 percent of the income scale than from the entire bottom 60 percent.

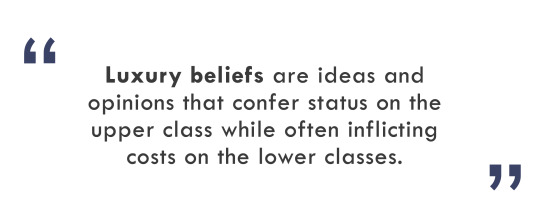

Throughout my experiences traveling along the class ladder, I made a discovery: Luxury beliefs have, to a large extent, replaced luxury goods. Luxury beliefs are ideas and opinions that confer status on the upper class, while often inflicting costs on the lower classes. In 1899, the economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen published a book called The Theory of the Leisure Class. Drawing on observations about social class in the late nineteenth century, Veblen’s key idea is that because we can’t be certain about the financial status of other people, a good way to size up their means is to see whether they can afford expensive goods and leisurely activities. This explains why status symbols are so difficult to obtain and costly to purchase. In Veblen’s day, people exhibited their status with delicate and restrictive clothing like tuxedos, top hats, and evening gowns, or by partaking in time-consuming activities like golf or beagling. These goods and leisurely activities could only be purchased or performed by people who did not work as manual laborers and could spend their time and money learning something with no practical utility. Veblen even goes so far as to say, “The chief use of servants is the evidence they afford of the master’s ability to pay.” For Veblen, butlers are status symbols, too.

In short, his idea was about how economic capital was often converted into cultural capital. These findings were later echoed by the renowned French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu in his 1979 book Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. In his body of work, Bourdieu described how “distance from necessity” characterized the affluent classes. In fact, Bourdieu coined the term “cultural capital.” Once our basic physical and material needs are met, people can then spend more time cultivating what Bourdieu called the “dispositions of mind and body” in the form of intricate and expensive tastes and habits that the upper classes use to obtain distinction.

Corresponding with these sociological observations, the biologist Amotz Zahavi proposed that animals evolve certain displays, traits, and behaviors because they are so physically costly. Many people are familiar with the example of the peacock’s tail. Only a healthy bird is capable of growing such plumage while managing to evade predators. A lesser known example is the behavior of the African gazelle. When these animals spot a predator, the healthy adult gazelles often engage in what is called “stotting.” They repeatedly jump as high as they can, springing vertically into the air with all four feet raised.

The signal this sends to predators is essentially: “I’m so fit that I can afford to expend valuable energy to show you how strong and robust I am compared with the other gazelles.” The predators then direct their attention to less lively and energetic targets. So for humans, top hats and designer handbags are costly signals of economic capacities; for gazelles, stotting is a costly signal of physical capacities. Veblen, Bourdieu and Zahavi all claimed that humans—or animals—flaunt certain symbols, communicate in specific ways, and adopt costly means of expressing themselves, in order to obtain distinction from the masses. Animals do this physically. And affluent humans often do it economically and culturally, with their status symbols. A difference, though, is that human signals often trickle to the rest of society, which weakens the power of the signal. Once a signal is adopted by the masses, the affluent abandon it. There are historical examples of this. For example, in the middle ages, spices were expensive and only the elites could afford them. It was a hard-to-fake signal of one’s social rank and economic resources. But as Europeans colonized India and the Americas, the cost of spices dropped, and the masses were now able to obtain them. As a result of widespread use, spices were no longer a status symbol.

Elites decided they were vulgar, and during the reign of France’s Louis XIV, court chefs banned sugar and spice from all meals except for desserts. Here’s another example. In the U.S., dueling was practiced primarily by the elite for many years. One key reason why it fell out of fashion in the early nineteenth century is because this ritual of dueling was gradually adopted by the lower classes. In response, the upper classes abandoned it because it was no longer prestigious. And then it was outlawed in the late nineteenth century.

The yearning for distinction is the key motive here. And in order to convert economic capital into cultural capital, it must be publicly visible. But distinction encompasses not only clothing or food or rituals. It also extends to ideas and beliefs and causes. In his book WASPS: The Splendors and Miseries of an American Aristocracy, the author Michael Knox Beran examined the lives and habits of upper-class Americans from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. He writes that “WASPS” had mixed feelings about their fellow citizens.

These upper-crust Americans viewed ordinary Americans as “sunk in moronic darkness” and that “It is a question whether a high WASP ever supported a fashionable cause without some secret knowledge that the cause was abhorred by the vulgarians.” This still goes on today. In the past, people displayed their membership in the upper class with their material accoutrements. But today, because material goods have become a noisier signal of one’s social position and economic resources, the affluent have decoupled social status from goods, and re-attached it to beliefs. The upper class craves distinction. The French sociologist Émile Durkheim understood this when he wrote, “The more one has, the more one wants, since satisfactions received only stimulate instead of filling needs.”

And this is backed by recent research. A 2020 study titled “The possession of high status strengthens the status motive” led by Cameron Anderson at UC Berkeley found that relative to lower-class individuals, upper-class individuals have a greater desire for wealth and status. In other words, high-status people desire wealth and status more than anyone else. By now you probably know the answer to the question I asked at the beginning: what do top hats have in common with defunding the police. Well, who was the most likely to support the fashionable defund the police cause in 2020 and 2021? A survey from YouGov found that Americans in the highest income category were by far the most supportive of defunding the police.

They can afford to hold this position, because they already live in safe, often gated communities. And they can afford to hire private security. In the same way that a vulnerable gazelle can’t afford to engage in stotting because it would put them in increased danger, a vulnerable poor person in a crime-ridden neighborhood can’t afford to support defunding the police. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, compared to Americans who earn more than $75,000 a year, the poorest Americans are seven times more likely to be victims of robbery, seven times more likely to be victims of aggravated assault, and twenty times more likely to be victims of sexual assault. Expressing a luxury belief is a manifestation of cultural capital, a signal of one’s fortunate economic circumstances. There are other examples of luxury beliefs as well, such as the downplaying of individual agency in shaping life outcomes. A 2019 study led by Joseph Daniels at Marquette University was published in the journal of Applied Economics Letters.

They found that individuals with higher income or a higher social status were the most likely to say that success results from luck and connections rather than hard work, while low-income individuals were more likely to say success comes from hard work and individual effort. Well, which belief is more likely to be true? Plenty of research indicates that compared with an external locus of control, an internal locus of control is associated with better academic, economic, health, and relationship outcomes. Believing you are responsible for your life’s direction rather than external forces appears to be beneficial. Here’s the late Stanford psychology professor Albert Bandura. His vast body of research showed that belief in personal agency, or what he described as “self-efficacy,” has powerful positive effects on life outcomes.

Undermining self-efficacy will have little effect on the rich and educated, but will have pronounced effects for the less fortunate. It’s also generally instructive to see what affluent people tell their kids. And what seems to happen is that affluent people often broadcast how they owe their success to luck. But then they tell their own children about the importance of hard work and individual effort. Now let’s discuss strange vocabulary. When I was growing up in foster homes, or making minimum wage as a dishwasher, or serving in the military, I never heard words like “cultural appropriation” or “gendered” or “heteronormative.”

Working class people could not tell you what these terms mean. But if you visit an elite university, you’ll find plenty of affluent people who will eagerly explain them to you. When people express unusual beliefs that are at odds with conventional opinion, like defunding the police or downplaying hard work, or using peculiar vocabulary, often what they are really saying is, “I was educated at a top university” or “I have the means and time to acquire these esoteric ideas.” Only the affluent can learn these things because ordinary people have real problems to worry about. To this extent, Pierre Bourdieu in The Forms of Capital wrote, “The best measure of cultural capital is undoubtedly the amount of time devoted to acquiring it.”

The chief purpose of luxury beliefs is to indicate evidence of the believer’s social class and education. Members of the luxury belief class promote these ideas because it advances their social standing and because they know that the adoption of these policies or beliefs will cost them less than others. Advocating for defunding the police or promoting the belief we are not responsible for our actions are good ways of advertising membership of the elite. Why are affluent people more susceptible to luxury beliefs? They can afford it. And they care the most about status.

In short, luxury beliefs are the new status symbols. They are honest indicators of one’s social position, one’s level of wealth, where one was educated, and how much leisure time they have to adopt these fashionable beliefs. And just as many luxury goods often start with the rich but eventually become available to everyone, so it is with luxury beliefs. But unlike luxury goods, luxury beliefs can have long term detrimental effects for the poor and working class. However costly these beliefs are for the rich, they often inflict even greater costs on everyone else.

#Rob Henderson#luxury beliefs#defund the police#status symbol#status seeking#virtue signal#virtue signalling#virtue signaling#psychology#human psychology#luxury goods#cultural capital#woke#wokeism#cult of woke#wokeness#wokeness as religion#religion is a mental illness

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

bio book log: day 7

book: ‘The Selfish Gene’ by Richard Dawkins

starting page: 314

ending page: 333/668

read for: 74 mins (22:23-23:37) (there were like two 5-page-long end notes okay)

comments: just saying Amotz Zahavi’s corroborated theory clearly shows that me not looking like Kim K will actually work in my favour in attracting a partner. Take that beauty standards. (warning: improper use of animal behaviour theory)

#study#study tumblr#studyblr#me#bio#biology#science#animal behavior#reading#book tumblr#bookblr#the selfish gene#richard dawkins#bio book log#bbl

1 note

·

View note

Note

Thoughts on The Handicap Principle? (For example, peacocks having long feathers to signal to potential mates that they can survive even with this disadvantage and so would have good genes) It made sense to me many years ago, but more recently I’ve seen that people are trying to refute it (Penn 2019).

Oh yes, I’m familiar with the Handicap Principle. The debate over its validity largely takes place in more theoretical branches of evolutionary biology than my own research focuses on though, so I suggest reading Penn and Számadó (2020) for a review of how it has been received by the scientific community.

The story is long and complex, but I’ll try to summarize a few take-home points here. The basic gist of why the Handicap Principle, as it was originally proposed, has come under fire is that there is little if any evidence that signaling structures and behaviors in animals evolve because they are handicaps. A preference specifically for handicaps in mates is unlikely to be selected for in the long run, because this would quickly reach an optimum where any fitness benefits compensating for the handicaps can increase no further and such a preference stops being an advantage. In theory, it is possible for sexually selected signals to have negative effects on individual survival, but it is more likely that such signals were favored despite their drawbacks rather than because of them. There certainly isn’t much to suggest that the handicap hypothesis is an overarching principle that can be generalized to a wide range of animal signals.

What appears to have been a major source of confusion in the technical literature is that the same researcher who came up with the Handicap Principle, Amotz Zahavi, also suggested a distinct (but related) idea, condition-dependent signaling. This hypothesis proposed that reliable signals of mate quality can be selected for when the cost of producing them is more affordable to higher-quality individuals. Condition-dependent signaling differs from the handicap hypothesis in that signals are not selected for because they are costly in themselves, but instead because lower-quality individuals have a reduced ability to express them in the first place. It also doesn’t require signals to be handicapping (as long as they are being expressed according to the signaler’s actual condition), nor did it claim to be a general principle explaining all types of reliable signals. Condition-dependent signaling under at least some circumstances has been upheld by several subsequent studies, but it has often been conflated with the Handicap Principle, making the latter appear more strongly supported than it actually was.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bronx Zoo, New York City (No. 12)

Peafowl is a common name for three bird species in the genera Pavo and Afropavo of the family Phasianidae, the pheasants and their allies. Male peafowl are referred to as peacocks, and female peafowl as peahens, though peafowl of either sex are often referred to colloquially as "peacocks." The two Asiatic species are the blue or Indian peafowl originally of the Indian subcontinent, and the green peafowl of Southeast Asia; the one African species is the Congo peafowl, native only to the Congo Basin. Male peafowl are known for their piercing calls and their extravagant plumage. The latter is especially prominent in the Asiatic species, which have an eye-spotted "tail" or "train" of covert feathers, which they display as part of a courtship ritual.

The functions of the elaborate iridescent colouration and large "train" of peacocks have been the subject of extensive scientific debate. Charles Darwin suggested they served to attract females, and the showy features of the males had evolved by sexual selection. More recently, Amotz Zahavi proposed in his handicap theory that these features acted as honest signals of the males' fitness, since less-fit males would be disadvantaged by the difficulty of surviving with such large and conspicuous structures.

Source: Wikipedia

The South African ostrich (Struthio camelus australis), also known as the black-necked ostrich, Cape ostrich or southern ostrich is a subspecies of the common ostrich endemic to Southern Africa. It is widely farmed for its meat, eggs and feathers.

The South African ostrich is found in South Africa, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Angola and Botswana. It lives in south of the rivers Zambezi and Cunene.

It is farmed for its eggs, meat, leather and feathers in the Little Karoo area of Cape Province.

Source:

Wikipedia

#Saffron finch#Butterfly Garden#Bronx Zoo#my favorite zoo#New York City#nature#flora#fauna#animal#original photography#Blue dacnis#peacock#peafowl#South African ostrich#giraffe#blue#head#feather#USA#travel#summer 2018#Bronx#tourist attraction#Northeastern USA#vacation#grass#tree#indoors#outdoors#peahens

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Peacock

Episode page

Click here to listen

Click here to download

This episode is about the peacock, not because it is the national bird of India, which it is. But because it gave rise to the second most important work in evolutionary biology. I speak of course of Charles Darwin’s theory of sexual selection.

Darwin has referred to the Peacock just three times in his magnum opus, the origin of species.…

View On WordPress

#Amotz Zahavi#Charles Darwin#Hindu mythology#Lord Muruga#peacock#peacock&039;s tail#peafowl#Richard Dawkins#Ronald Fisher 0

0 notes

Text

Homo Darwinus: Economia Evolucionária

Jean Tirole (1953- ), ganhador do Prêmio Nobel de Economia 2014, por análise do poder e regulação de mercado, em seu livro Economia do bem comum (1ª.ed. – Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2020), por fim, gostaria de dizer algumas palavras sobre um campo em rápida expansão, a Economia Evolucionária, sobre a qual não fez nenhuma pesquisa.

Um dos fatos mais marcantes dos últimos vinte anos na pesquisa econômica é podermos começar a reconciliar a visão do homem da Economia com a visão de Darwin de sermos todos o produto da seleção natural.

Existem muitos exemplos de polinização cruzada entre Economia e Biologia Evolutiva. Por exemplo, as preferências sociais, cruciais para um economista, como mostra este capítulo, também são examinadas do ângulo da evolução.

Os biólogos também contribuíram para a Teoria dos Jogos. Por exemplo, o primeiro modelo da “guerra de atrito”, descrevendo a irracionalidade coletiva de situações como uma guerra ou uma greve, quando cada parte sofre, mas permanece firme na esperança de a outra capitular antes, é devido ao biólogo Maynard Smith, em 1974, enquanto o paradigma foi posteriormente refinado pelos economistas.

A Teoria dos Relatórios é uma terceira preocupação compartilhada por biólogos e economistas. A ideia geral da teoria é relatar ser benéfico para um indivíduo, animal, planta, estado ou empresa sob a ameaça de desperdiçar recursos comuns, se convencer outras pessoas a se comportarem de maneira conciliatória.

Os animais usam uma série de sinais dispendiosos e até disfuncionais (como penas de pavão) para atrair parceiros ou evitar predadores, assim como os humanos correm riscos para impressionar seus rivais ou alguém desejada de eles atrair. Uma empresa pode vender com prejuízo, na tentativa de convencer seus rivais de seus custos serem baixos ou de sua base financeira ser tão sólida a ponto de fazê-los sair do mercado.

Logo após a publicação do famoso artigo do economista Michael Spence sobre reportagem, o biólogo Amotz Zahavi publicou análises sobre o mesmo assunto. Esses artigos retomam e formalizam o trabalho do sociólogo Thorstein Veblen (The Theory of the Leisure Class, 1899) e das abordagens francesas à diferenciação (Jean Baudrillard, La Société de Consumer, 1970; Pierre Bourdieu, La Distinction, 1979).

As ideias sobre reportagem têm origem em Darwin, The Descent of Man (1871), muito antes de economistas ou sociólogos se interessarem por ela. Portanto, não há mais elo entre a Economia e as Ciências Naturais do que entre a Economia e as outras Ciências Humanas e Sociais.

Todos esses elementos são, obviamente, apenas uma introdução breve e seletiva a um campo disciplinar vasto e em evolução. Estamos testemunhando uma reunificação progressiva das Ciências Sociais.

Essa reunificação será lenta, mas inevitável: de fato, como Jean Tirole disse na introdução deste capítulo, antropólogos, economistas, historiadores, juristas, filósofos, cientistas políticos, psicólogos e sociólogos est��o interessados nos mesmos indivíduos, nos mesmos grupos e para as mesmas empresas. A convergência existente até o final do século XIX deve ser restaurada e exigirá esforços por parte das várias comunidades científicas para se abrir às técnicas e ideias de outras disciplinas.

Homo Darwinus: Economia Evolucionária publicado primeiro em https://fernandonogueiracosta.wordpress.com

0 notes

Text

How Advertising Signals Brand Power

In the nineteenth century Charles Darwin was struck by a number of oddities in the natural world that contradicted his theory of evolution. The peacock, for example, with its huge cumbersome tail baffled him to the extent he wrote to Asa Gray on April 3rd 1860:

“The sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick”.

The peacock troubled Darwin because his theory suggested it should have evolved a shorter tail that made fleeing from predators easier.

The peacock wasn’t the only troublesome example. The male bowerbird spends thousands of hours building extravagant nests. Again, a seeming contradiction to survival of the fittest. Surely, birds that spent less time nest-building would have a better chance of finding the food necessary to survive?

Darwin’s conundrum was answered in 1975 by Amotz Zahavi, a biologist at Tel Aviv University, who developed the theory of costly signaling. According to Zahavi costly signals are harder to fake and are therefore, more believable.

The ability to survive despite a cumbersome tail or hours spent nest-building conveys genuine genetic fitness to potential mates. Less fit specimens don’t have the time available to build a palatial nest or the agility to avoid predators when handicapped with a long tail.

The Advertising Application

A similar effect occurs in advertising. John Kay, an economist at Oxford University, suggests that advertising works not because of the explicit messages, but because it’s a costly signal. Advertising known to be expensive signals the volume of the resources available to the advertiser. As Kay says in his landmark paper:

“The advertiser has either persuaded lots or people to buy his product already, a good sign, or has persuaded someone to lend him lots of money to finance the campaign.”

Just as in the natural world, advertising works, not despite its perception of costliness, but because of it.

Kay further states that since advertising tends to recoup its costs in the long term only a company with substantial commitment to their brand would invest significant sums of money in advertising. A poor-quality brand can advertise to generate trial but no amount of spend can deliver repeat purchase to disgruntled customers.

In his words, advertising, therefore, acts as a screening mechanism that:

“convincingly signals the quality of a product by displaying the producer’s sincere faith in his own output, reflected by the money spent promoting it.”

This theory neatly explains why famous sponsorships are effective. They demonstrate a costly and, therefore, honest belief in the strength of the advertised product.

Of course, this theory relies on an awareness of the price of sponsorships. Is this the case? A study I conducted along with Jenny Riddell suggests that consumers are well aware how costly sports sponsorship can be. We surveyed 333 nationally representative consumers about the cost of the Real Madrid shirt sponsorship. Of those who gave a figure, 89% thought it cost more than £30 million per year, the rough cost.

How Can Brands Capitalize On These Findings?

Brands must recognize that much of advertising’s impact comes from implicit communication. There is a role, even in the era of procurement, for bold brand statements. The occasional extravagance displays a confidence that mere ad claims cannot emulate.

You can find more ideas like this in my new book The Choice Factory: 25 Behavioral Biases That Influence What We Buy

Meet me in New York City on June 4th for an in-depth discussion on how to apply behavioral science to advertising.

The Blake Project Can Help: Differentiate Your Brand In The Brand Positioning Workshop

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Licensing and Brand Education

FREE Publications And Resources For Marketers

0 notes

Link

The handicap principle is a hypothesis proposed by Amotz Zahavi to explain how evolution may lead to "honest" or reliable signalling between animals which have an obvious motivation to bluff or deceive each other.[1][2][3] It suggests that costly signals must be reliable signals, costing the signaller something that could not be afforded by an individual with less of a particular trait. For example, in sexual selection, the theory suggests that animals of greater biological fitness signal this status through handicapping behaviour, or morphology that effectively lowers this quality. The central idea is that sexually selected traits function like conspicuous consumption, signalling the ability to afford to squander a resource. Receivers then know that the signal indicates quality, because inferior quality signallers are unable to produce such wastefully extravagant signals.

0 notes

Text

How Advertising Signals Brand Power

In the nineteenth century Charles Darwin was struck by a number of oddities in the natural world that contradicted his theory of evolution. The peacock, for example, with its huge cumbersome tail baffled him to the extent he wrote to Asa Gray on April 3rd 1860:

“The sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick”.

The peacock troubled Darwin because his theory suggested it should have evolved a shorter tail that made fleeing from predators easier.

The peacock wasn’t the only troublesome example. The male bowerbird spends thousands of hours building extravagant nests. Again, a seeming contradiction to survival of the fittest. Surely, birds that spent less time nest-building would have a better chance of finding the food necessary to survive?

Darwin’s conundrum was answered in 1975 by Amotz Zahavi, a biologist at Tel Aviv University, who developed the theory of costly signaling. According to Zahavi costly signals are harder to fake and are therefore, more believable.

The ability to survive despite a cumbersome tail or hours spent nest-building conveys genuine genetic fitness to potential mates. Less fit specimens don’t have the time available to build a palatial nest or the agility to avoid predators when handicapped with a long tail.

The Advertising Application

A similar effect occurs in advertising. John Kay, an economist at Oxford University, suggests that advertising works not because of the explicit messages, but because it’s a costly signal. Advertising known to be expensive signals the volume of the resources available to the advertiser. As Kay says in his landmark paper:

“The advertiser has either persuaded lots or people to buy his product already, a good sign, or has persuaded someone to lend him lots of money to finance the campaign.”

Just as in the natural world, advertising works, not despite its perception of costliness, but because of it.

Kay further states that since advertising tends to recoup its costs in the long term only a company with substantial commitment to their brand would invest significant sums of money in advertising. A poor-quality brand can advertise to generate trial but no amount of spend can deliver repeat purchase to disgruntled customers.

In his words, advertising, therefore, acts as a screening mechanism that:

“convincingly signals the quality of a product by displaying the producer’s sincere faith in his own output, reflected by the money spent promoting it.”

This theory neatly explains why famous sponsorships are effective. They demonstrate a costly and, therefore, honest belief in the strength of the advertised product.

Of course, this theory relies on an awareness of the price of sponsorships. Is this the case? A study I conducted along with Jenny Riddell suggests that consumers are well aware how costly sports sponsorship can be. We surveyed 333 nationally representative consumers about the cost of the Real Madrid shirt sponsorship. Of those who gave a figure, 89% thought it cost more than £30 million per year, the rough cost.

How Can Brands Capitalize On These Findings?

Brands must recognize that much of advertising’s impact comes from implicit communication. There is a role, even in the era of procurement, for bold brand statements. The occasional extravagance displays a confidence that mere ad claims cannot emulate.

You can find more ideas like this in my new book The Choice Factory: 25 Behavioral Biases That Influence What We Buy

Meet me in New York City on June 4th for an in-depth discussion on how to apply behavioral science to advertising.

The Blake Project Can Help: Differentiate Your Brand In The Brand Positioning Workshop

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Licensing and Brand Education

FREE Publications And Resources For Marketers

from WordPress https://glenmenlow.wordpress.com/2018/05/14/how-advertising-signals-brand-power/ via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

Indian peafowl India, Rajkot, Sep-2017. The Indian peafowl or blue peafowl (Pavo cristatus), a large and brightly coloured bird, is a species of peafowl native to South Asia, but introduced in many other parts of the world. The male, or peacock, is predominantly blue with a fan-like crest of spatula-tipped wire-like feathers and is best known for the long train made up of elongated upper-tail covert feathers which bear colourful eyespots. These stiff feathers are raised into a fan and quivered in a display during courtship. Peahens lack the train, and have a greenish lower neck and duller brown plumage. The Indian peafowl lives mainly on the ground in open forest or on land under cultivation where they forage for berries, grains but also prey on snakes, lizards, and small rodents. Their loud calls make them easy to detect, and in forest areas often indicate the presence of a predator such as a tiger. They forage on the ground in small groups and usually try to escape on foot through undergrowth and avoid flying, though they fly into tall trees to roost. The function of the peacock's elaborate train has been debated for over a century. In the 19th century, Charles Darwin found it a puzzle, hard to explain through ordinary natural selection. His later explanation, sexual selection, is widely but not universally accepted. In the 20th century, Amotz Zahavi argued that the train was a handicap, and that males were honestly signalling their fitness in proportion to the splendour of their trains. Despite extensive study, opinions remain divided on the mechanisms involved. The bird is celebrated in Indian and Greek mythology and is the national bird of India. The Indian peafowl is listed as of Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).Wikipedia].[Photo© - Raju Karia]. #birdsinflight +Birds In Flight +Andy Brown #WildlifeInTheCity +WILDLIFE in the City curated by +Edith Kukla #birdloversandwildlife#Animalia +Animalia #birdsofindia #beautifulbeautifulbirds #beautifulbirds #birdsinfocus #birdsociety #birdsoftheworld #birdlovers #birdphotography #birdphotographs #birds #bird #amazingbirds #naturelovers #wildlifephotography #wildphotogra

#wildlifeinthecity#bird#birdphotographs#birdsofindia#beautifulbirds#birdsinfocus#wildphotogra#birdsinflight#birdlovers#birds#birdsoftheworld#naturelovers#beautifulbeautifulbirds#animalia#birdsociety#amazingbirds#wildlifephotography#birdphotography#birdloversandwildlife

0 notes

Text

New Post has been published on THIẾT BỊ KHOA HỌC CÔNG NGHỆ

New Post has been published on http://thietbikhoahoccongnghe.com.vn/ethology-phan-6.html

Ethology - Phần 6

Lợi ích và chi phí của cuộc sống nhóm Một lợi thế của cuộc sống nhóm có thể làm giảm sự ăn thịt. Nếu số lượng các cuộc tấn công của loài săn mồi vẫn giữ nguyên như nhau mặc dù gia tăng số lượng con mồi, mỗi con mồi có thể giảm được nguy cơ tấn công của loài săn mồi thông qua hiệu ứng pha loãng. Thêm vào đó, một con săn mồi bị nhầm lẫn bởi một khối lượng cá thể tìm thấy nó khó khăn hơn để chỉ ra một mục tiêu. Vì lý do này, sọc của ngựa vằn không chỉ mang tính ngụy trang trong môi trường sống của cỏ cao, mà còn là lợi thế của việc trộn lẫn vào một đàn ngựa vằn khác Theo nhóm, con mồi cũng có thể chủ động giảm rủi ro ăn thịt của mình thông qua các chiến thuật phòng thủ hiệu quả hơn, hoặc thông qua việc phát hiện trước đó của loài săn mồi thông qua tăng cường cảnh giác.

Một ưu điểm khác của cuộc sống nhóm có thể là tăng khả năng thức ăn gia súc. Các thành viên của nhóm có thể trao đổi thông tin về các nguồn thức ăn giữa người khác, tạo điều kiện thuận lợi cho quá trình định vị nguồn tài nguyên Honeybees là một ví dụ đáng chú ý của việc này, sử dụng vũ điệu chư hầu để truyền đạt vị trí của hoa tới phần còn lại của hive . Người săn mồi cũng nhận được lợi ích từ việc săn bắt theo nhóm, thông qua việc sử dụng các chiến lược tốt hơn và có khả năng hạ bệ con mồi lớn hơn

Một số bất lợi đi kèm theo trong các nhóm. Sống gần các loài động vật khác có thể tạo điều kiện cho việc lây truyền ký sinh trùng và bệnh tật, và các nhóm quá lớn cũng có thể gặp sự cạnh tranh lớn hơn về nguồn tài nguyên và bạn tình

Kích thước nhóm Về mặt lý thuyết, động vật xã hội cần phải có kích cỡ nhóm tối ưu nhằm tối đa hóa lợi ích và giảm thiểu chi phí cho cuộc sống nhóm. Tuy nhiên, về mặt bản chất, hầu hết các nhóm đều ổn định với kích cỡ lớn hơn một chút so với kích cỡ tối ưu. Bởi vì nó thường mang lại lợi ích cho một cá nhân tham gia vào một nhóm có kích cỡ tối ưu, mặc dù giảm nhẹ lợi thế cho tất cả các thành viên, tăng kích thước cho đến khi thuận lợi hơn để duy trì một mình hơn là tham gia một nhóm quá đầy đủ.

Tinbergen của bốn câu hỏi cho ethologists Bài chi tiết: Tinbergen của bốn câu hỏi Niko Tinbergen lập luận rằng đạo đức luôn cần bao gồm bốn loại giải thích trong bất kỳ trường hợp hành vi nào:

Chức năng – Làm thế nào để hành vi này ảnh hưởng đến cơ hội sống sót và sinh sản của con vật? Tại sao động vật phản ứng theo cách đó thay vì một số cách khác? Nguyên nhân – Các kích thích gây ra phản ứng, và nó đã được sửa đổi bằng cách học gần đây như thế nào? Phát triển – Làm thế nào để hành vi thay đổi theo tuổi, và kinh nghiệm ban đầu là cần thiết cho động vật để hiển thị các hành vi? Lịch sử tiến hóa – cách hành xử này so sánh với hành vi tương tự ở các loài liên quan, và làm thế nào nó có thể bắt đầu qua quá trình tiến hoá? Những lời giải thích này bổ sung chứ không phải là loại trừ lẫn nhau – tất cả các trường hợp hành vi yêu cầu giải thích ở bốn mức này. Ví dụ, chức năng ăn uống là để có được các chất dinh dưỡng (giúp cơ thể sống còn và sinh sản), nhưng nguyên nhân trực tiếp của việc ăn là đói (nguyên nhân). Sự đói và ăn có tính tiến hóa cổ xưa và được tìm thấy trong nhiều loài (lịch sử tiến hóa), và phát triển sớm trong vòng đời sinh vật (phát triển). Thật dễ dàng để nhầm lẫn những câu hỏi đó – ví dụ như để cho rằng người ta ăn vì họ đói và không nhận được chất dinh dưỡng mà không nhận ra rằng lý do người ta cảm thấy đói là bởi vì nó gây ra các chất dinh dưỡng.

Danh sách các nhà ethologists Những người đã có những đóng góp đáng kể về đạo đức học (nhiều người được liệt kê ở đây thực sự là những nhà tâm lý học so sánh):

Robert Ardrey Jonathan Balcombe Patrick Bateson Marc Bekoff Ingeborg Beling John Bowlby Donald Broom Wallace Craig Charles Darwin Marian Stamp Dawkins Richard Dawkins Viktor Dolnik Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt John Endler Jean-Henri Fabre Dian Fossey Karl von Frisch Douglas P. Fry Birutė Galdikas Jane Goodall James L. Gould Chùa Grandin Judith Hand Clarence Ellis Harbison Heini Hediger Oskar Heinroth Robert Hinde Bernard Hollander Sarah Hrdy Julian Huxley Julian Jaynes Erich Klinghammer John Krebs Alistair Lawrence Konrad Lorenz Aubrey Manning Eugene Marais Peter Robert Marler Patricia McConnell Desmond Morris Martin Moynihan Ivan Pavlov Irene Pepperberg Kevin Richardson George Romanes Thomas Sebeok Barbara Smuts William Homan Thorpe Niko Tinbergen Jakob von Uexküll Frans de Waal William Morton Wheeler E. O. Wilson Charles Otis Whitman Amotz Zahavi

0 notes

Text

Amotz Zahavi, Israeli evolutionary biologist, Died at 89

Amotz Zahavi, Israeli evolutionary biologist, Died at 89

Amotz Zahavi was born on January 1, 1928, and died on May 12, 2017. He was an Israeli evolutionary biologist. Zahavi was a Professor in the Department of Zoology at Tel Aviv University, and one of the founders of the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel (known as the “SPNI”). Amotz Zahavi’s main work concerned the evolution of signals, particularly those signals that are indicative of…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Peafowl, Bronx Zoo (No. 1)

Peafowl is a common name for three bird species in the genera Pavo and Afropavo of the family Phasianidae, the pheasants and their allies. Male peafowl are referred to as peacocks, and female peafowl are referred to as peahens, even though peafowl of either sex are often referred to colloquially as "peacocks".

The two Asiatic species are the blue or Indian peafowl originally of the Indian subcontinent, and the green peafowl of Southeast Asia; the one African species is the Congo peafowl, native only to the Congo Basin. Male peafowl are known for their piercing calls and their extravagant plumage. The latter is especially prominent in the Asiatic species, which have an eye-spotted "tail" or "train" of covert feathers, which they display as part of a courtship ritual.

The functions of the elaborate iridescent colouration and large "train" of peacocks have been the subject of extensive scientific debate. Charles Darwin suggested that they served to attract females, and the showy features of the males had evolved by sexual selection. More recently, Amotz Zahavi proposed in his handicap theory that these features acted as honest signals of the males' fitness, since less-fit males would be disadvantaged by the difficulty of surviving with such large and conspicuous structures.

Source: Wikipedia

#peacock#peahen#Peafowl#African Plains#Bronx Zoo#my favorite zoo#USA#travel#bird#animal#flora#fauna#meadow#grass#lawn#outdoors#original photography#summer 2019#tourist attraction#landmark#vacation#fence#New York City#Eastern USA#cityscape

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The term "peacock" is properly reserved for the male. The functions of the elaborate iridescent coloration and large "train" of peacocks have been the subject of extensive scientific debate. Charles Darwin suggested they served to attract females. More recently, Amotz Zahavi proposed these acted as honest signals of the males' fitness, since less fit males would be disadvantaged by the difficulty of surviving with such large and conspicuous structures. The female also displays her plumage to ward off female competition. (at Los Angeles County Arboretum & Botanic Garden)

0 notes