#american cancer research center

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

MTV High Priority (1987)

American Cancer Research Center (AMC) Benefit Album with Andy Warhol Cover Art and Breast Examination Tips on Back Cover.

Red variant. This variant has the red shading to the MTV-logo on the front, there is also a variant in which the shading is yellow and the titles along the top of the front cover were in black print instead of white, red and blue.

RCA Records

#my vinyl playlist#mtv#mtv high priority#andy warhol#aretha franklin#the eurythmics#bangles#stevie nicks#whitney houston#cyndi lauper#patti labelle#pat benatar#heart#belinda carlisle#grace jones#american cancer research center#bananarama#rca records#80’s rock#80’s music#record cover#album cover#album art#vinyl records

0 notes

Text

Article | Paywall-Free

"The Environmental Protection Agency finalized a rule Tuesday [October 8, 2024] requiring water utilities to replace all lead pipes within a decade, a move aimed at eliminating a toxic threat that continues to affect tens of thousands of American children each year.

The move, which also tightens the amount of lead allowed in the nation’s drinking water, comes nearly 40 years after Congress determined that lead pipes posed a serious risk to public health and banned them in new construction.

Research has shown that lead, a toxic contaminant that seeps from pipes into the drinking water supply, can cause irreversible developmental delays, difficulty learning and behavioral problems among children. In adults, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, lead exposure can cause increased blood pressure, heart disease, decreased kidney function and cancer.

But replacing the lead pipes that deliver water to millions of U.S. homes will cost tens of billions of dollars, and the push to eradicate them only gathered momentum after a water crisis in Flint, Mich., a decade ago exposed the extent to which children remain vulnerable to lead poisoning through tap water...

The groundbreaking regulation, called the Lead and Copper Rule Improvements, will establish a national inventory of lead service lines and require that utilities take more aggressive action to remove lead pipes on homeowners’ private property. It also lowers the level of lead contamination that will trigger government enforcement from 15 parts per billion (ppb) to 10 ppb.

The rule also establishes the first-ever national requirement to test for lead in schools that rely on water from public utilities. It mandates thatwater systems screen all elementary and child-care facilities, where those who are the most vulnerable to lead’s effects — young children — are enrolled, and that they offer testing to middle and high schools.

The White House estimates that more than 9 million homes across the country are still supplied by lead pipelines, which are the leading source of lead contamination through drinking water. The EPA has projected that replacing all of them could cost at least $45 billion.

Lead pipes were initially installed in cities decades ago because they were cheaper and more malleable, but the heavy metal can wear down and corrode over time. President Joe Biden has made replacing them one of his top environmental priorities, securing $15 billion to give states over five years through the bipartisan infrastructure law and vowing to rid the country of lead pipes by 2031. The administration has spent $9 billion so far — enough to replace up to 1.7 million lead pipes, the administration said.

On Tuesday, the administration said it was providing an additional $2.6 billion in funding for pipe replacement. Over 367,000 lead pipes have been replaced nationwide since Biden took office, according to White House officials, affecting nearly 1 million people...

Environmental advocates said that former president Donald Trump, who issued much more modest revisions to the lead and copper rule just days before Biden took office, would have a hard time reversing the new standards.

Erik Olson, the senior strategic director for health at the Natural Resources Defense Council, said that the Safe Drinking Water Act has provisions prohibiting weakening the health protections of existing standards...

Olson added that the rule “represents a major victory for public health” and will protect millions of people “whose health is threatened every time they fill a glass from the kitchen sink contaminated by lead.”

“While the rule is imperfect and we still have more to do, this is by far the biggest step towards eliminating lead in tap water in over three decades,” he said."

-via The Washington Post, October 8, 2024

#lead#lead pipe#lead poisoning#united states#us politics#epa#clean water#drinking water#public health#environmental protection#child development#biden#biden administration#kamala harris#good news#hope#voting matters

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Also preserved on our archive

by Miles W. Griffis

Atinuki “Tinu” Abayomi-Paul, a prominent writer and disability advocate, died on September 26 at home in Texas. She was 52.

Abayomi-Paul was well known in the Long COVID and disability community for her writing, speaking, and mutual aid organizing. She was the founder of Everywhere Accessible, an advocacy organization which she launched in 2019 to educate the public about accessibility and center the experiences of Black disabled women.

In 2022, she was hospitalized with COVID-19, leading to COVID-induced pneumonia. She later developed chronic lymphocytic leukemia, as well as Long COVID, myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), and other chronic illnesses.

She recently spoke with The Sick Times about her experience with extreme heat and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).

“My fear for the future is that those of us who cannot tolerate the heat will die,” she said. “Another fear I have is that no one will listen.”

Abayomi-Paul frequently wrote about and helped break stigmas about immunocompromised people. She centered the experiences of the most marginalized, who were left behind in the government’s failed response to the continuing COVID-19 pandemic.

“I hope my story humanizes the experience of having COVID for people,” she wrote in an essay following her hospitalization. “Those of us at high risk aren���t abstract people you’ve never met. We’re people you know and love, and we might die because you won’t wear a mask.”

Over the past week, friends, family, and members of the disability community have written tributes to Abayomi-Paul for her leadership, care, and community building.

“She had such giggly personality, but was often so tired from just trying to stay afloat,” disability advocate Imani Barbarin wrote on Twitter/X. “Still, she loved this community and consistently felt like she wasn’t doing enough. Tinu, you were enough.”

“She gave so much of herself and cared about the disability community deeply,” Alice Wong wrote. In another tribute, Sarah Reneé stated that she “advocated with spoons she didn’t have not just for herself, but the entire community.”

“Many of us owe our lives and the evolution of our politics to disabled Black women like [Tinu] and [Shafiqah Hudson],” writer Clarkisha Kent posted.

Like Abayomi-Paul, Hudson died while battling Long COVID and cancer. Hudson passed in February 2024 at an extended-stay hotel in Portland, Oregon; she stated before her death that if she died, Long COVID was the cause.

Abayomi-Paul’s cause of death has not been stated. She wrote on August 3, 2024: “People not masking is literally killing me… If I do die, this is what killed me, people not masking or believing Long COVID lowers your immunity…”

While research has extensively documented the disabling symptoms and scope of Long COVID, science and health institutions have paid less attention to the disease’s potentially deadly consequences.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in early 2024 that over 5,000 Americans have died with Long COVID since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, but experts say this number is likely a significant undercount. Along with improved reporting standards, people with Long COVID need immediate support to prevent further fatalities, experts and advocates say.

Abayomi-Paul’s family and friends are currently fundraising for her funeral, medical expenses, and other costs. They are also planning a service — the date has not yet been released.

#mask up#covid#pandemic#covid 19#wear a mask#public health#coronavirus#sars cov 2#still coviding#wear a respirator#long covid#rest in peace#rest in power

82 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://x.com/lyokangirl/status/1800137471067603338?t=aOY0BrrgBo2CnqzAQrtY4A&s=19

The whole thread 🤔🤔🤔

Disclaimer first: I looked at this tweet when I saw anon's ask super early this morning. The original tweet that started this thread has now been deleted but it was a tweet containing this image from Matta of Fact's instagram stories:

Here is a screenshot with the twitter thread responding to a tweet that posted the above screenshot. I've redacted all the usernames (personal policy) but if you go to the URL in the anon's ask, you'll see them.

(I cut the thread in half so the images would be bigger. Start on the left with the yellow user.)

If it's too difficult to read:

Yellow works close to the hospital in Matta's story (the MD Anderson Center in Houston, Texas), which is probably the best hospital for cancer treatment and research in the world and treats people from all over the world. She thinks it's unlikely that Kate is in Texas getting treatment because she's been spotted in the UK but if she is getting treatment from the US, then strict medical privacy laws prohibit medical staff from talking about her (HIPAA) but it's curious no one else (ie other patients and hotel guests - the St. Regis mentioned in the reddit screenshot is a luxury hotel chain) have seen her.

Red is talking about how Kate and the BRF don't have the same expectation of personal privacy or a social contract here in the US that they would in the UK. In other words, UK media largely doesn't run pap/bystander photos of the royal family when they're not working. That's not true here in the US. Not only would American media print those photos, most Americans wouldn't have any problem taking those photos of Kate in the first place, especially if they can make a quick buck or get social media clout.

Blue is worried about Kate and thinks this means the worst because she's trying to read between the lines. Yellow is trying to talk her out of panic.

I don't think this is true, for a number of reasons.

First, I don't trust Matta as a source. Never have, never will. She started out incredibly biased in favor of the Sussexes and while it looks like she's moved her coverage to become more neutral, I still can't shake her start as a Sussex Squaddie. As Maya Angelou said "when someone shows you who they are the first time, believe them."

Second, if it comes out that Kate, the Princess of Wales and the future Queen has abandoned the NHS or British care, she - and the BRF - can kiss the NHS charities, patronages, and support goodbye. Yes, the NHS is currently suffering and there's a whole bunch of controversy, but the royal family has stood by the NHS since the beginning. If it got out that they don't personally support the NHS...well, there's no putting that toothpaste back in the tube.

Third, yes, MD Anderson is considered one of the best, if not the best institution for cancer treatment and research in the world. They're part of the cancer moonshot initiative. People come from all over the world to use their facilities. And they send their people out to consult and teach all over the world as well. Kate, and the BRF, isn't risking her NHS support to fly halfway around the world. Especially if she's immuno-compromised, especially if she doesn't feel she is well enough or healthy-looking-enough for public engagements. Those doctors are coming to her.

Relatedly, Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace have been used as operating theaters and medical treatment spaces before. There's no need for Kate to go halfway around the world to a hospital when literally the hospital can come to her at Windsor Castle.

Now, is it possible she could've gone to Texas anyway? Yes, very much so. But my theory is, if she went in the first place, she went only once, to learn about her cancer and what her treatment options were, and then she went back to the UK. Why do I say this?

Because simply put: she has three school-aged children and kids talk. If Kate was spending all this time in the US, those kids would've said something to someone in that school community and it would've gotten out. After all, if someone's leaking Charlotte's cricket team schedule to social media, someone's going to leak any gossip they've heard about or from the children.

At the end of the day, you can believe whatever you see and however you interpret this. For me, I choose to believe the palace at their word over nameless internet strangers and a gossipmongerer. Maybe that makes me naive but it is what it is. The palace, and William, have said that Kate is doing well and is focused on her recovery and her family. We have no reason to believe that she's anywhere except where they've said she is: with her family in Windsor. We have no reason to believe her health isn't improving and that she isn't recovering because it would have been all over William's face the last few days (the man does not have a poker face at all) and it simply wasn't there.

I know people miss Kate. I know they'd like reassurance from her personally but that's not Kate's priority right now. Her priority is reassuring her children and being with them, as it should be. Let's give her the time, space, and privacy to do what she knows is right for her, and her family, and who knows. Maybe she'll surprise us in the coming weeks.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quelques citations:

«La médecine a pris crédit pour certaines avancées dans le domaine de la santé qu’elle ne mérite pas. Le choléra, le typhus, le tétanos, la diphtérie et la coqueluche, etc., étaient en régression avant que les vaccins spécifiques ne soient utilisés. En fait, cette régression résultait de l’amélioration des conditions d'hygiène, de l'évacuation des eaux d'égout, et de la distribution de la nourriture et de l’eau.»

Andrew Weil, Health and Healing.

«Les vaccins donnent les maladies et en créent de nouvelles. La preuve scientifique qu’une provocation artificielle d’une maladie empêche l’apparition d’une maladie naturelle n’a jamais été établie.»

Dr Paul-Émile CHÈVREFILS.

«Les vaccinations en bas âge ont des effets dangereux sur le système immunitaire de l’enfant, ne protègent pas l’enfant durant sa vie ouvrant la voie à d’autres maladies suite à une dysfonction immunitaire.»

Drs. H. BUTTRAM et J. HOFFMANN.

«La plupart des personnes qui sont mortes de la variole la contractèrent après avoir été vaccinées.»

Dr. J.W. HODGE, The Vaccination Superstition.

«Certaines souches de vaccins peuvent être impliquées dans des maladies dégénératives telles que l’arthrite rhumatoïde, la leucémie, le diabète et la sclérose en plaques.»

Dr. G. DETTMAN, Australian Nurses Journal

«Le risque de souffrir de complications sérieuses provenant des vaccins contre la grippe est beaucoup plus grand que la grippe elle-même.»

Dr. William FROSEHAVER

«Les vaccins peuvent causer l’arthrite chronique, la sclérose en plaques, le lupus érythémateux, le Parkinson et le cancer.»

Pr. R. SIMPSON, American Cancer Society

«Contrairement aux croyances antérieurement établies à propos des vaccins du virus de la polio, l’évidence existe maintenant que le vaccin vivant ne peut être administré sans risque de produire la paralysie.»

Dr. SALK (créateur du vaccin original de la polio dans les années 50).

«Le déclin du tétanos en tant que maladie commença avant l’introduction de l’anatoxine dans la population.»

Medical Journal of Australia, 1978.

«Les personnes vaccinées contre la grippe ont approximativement 10 fois plus de chances de contracter le syndrome de Guillain-Barré que ceux qui n’ont pas été vaccinées.»

Center for Disease Control, 1977.

«Il existe un lien entre l’autisme et la vaccination. Les enfants sont blessés par vaccinations.»

Dr. Bernard RIMLAND, directeur et fondateur du Autism Research Institute of San Diego.

«Pendant 23 ans, j’ai observé que les enfants non vaccinés étaient plus sains et plus robustes que les enfants vaccinés. Les allergies, l’asthme et des perturbations comportementales étaient clairement plus fréquentes chez les jeunes patients vaccinés. De plus, ils souffraient plus souvent ou plus sévèrement de maladies infectieuses que les autres.»

Dr. Philip INCAO.

«Sur les 3,3 millions d’enfants vaccinés annuellement aux États-Unis avec le DCT, 16 038 démontrèrent des crises aiguës et des pleurs persistants ‑‑ ce qui est considéré par plusieurs neurologistes comme l’indication d’une irritation du système nerveux central ; 8 484 eurent des convulsions ou furent en état de choc dans les 48 heures suivant l’injection du DCT.»

Dr. Allan HINMAN et Jeffrey COPELAN, Journal of the American Medical Association.

«Un enfant a huit fois plus de chances de mourir trois jours après avoir reçu le vaccin DCT (diphtérie, coqueluche, tétanos) qu’un enfant non vacciné.»

The American Journal of Epidemiology, 1992.

«Chaque fois qu’un enfant meurt de méningite dans les premières semaines de sa vie, on doit suspecter le BCG.»

Dr Jean ELMIGER, La médecine retrouvée.

«Les campagnes publicitaires en faveur des vaccins représentent un véritable lavage de cerveau : désinformation, trucage des statistiques, amalgame savant de l'effet protecteur du vaccin avec d'autres affections, annonce de possibilité de contagion totalement fantaisiste et enfin banalisation de l'acte vaccinal.»

Dr Alain SCOHY.

«La quasi-totalité des cas de poliomyélite recensés aux USA, de 1980 à 1994, a été causée par l'administration du vaccin oral atténué.»

Dépêche AFP, 1er février 1997.

« Il n'a jamais été prouvé scientifiquement que les vaccins étaient efficaces et sans danger.»

Dr Louis DE BROUWER, Vaccination, erreur médicale du siècle.

«Le système immunitaire est sévèrement endommagé suite aux vaccinations courantes.»

Le Concours médical, 20 janvier 1974.

«On risque sa vie en se soumettant à une intervention probablement inefficace afin d'éviter une maladie qui ne surviendra vraisemblablement jamais.»

Dr. Kris GAUBLOMME.

«Les 2/3 des 103 enfants décédés de la mort subite du nourrisson avaient reçu le vaccin DTP (DCT ?) dans les trois semaines précédant leur mort. Certains même étaient morts le lendemain.»

Dr. TORCH, Neurology, 1982.

«Les vaccinés, loin de constituer un barrage protecteur vis-à-vis des non-vaccinés, sont au contraire dangereux et peuvent contaminer le reste de la population, puisqu'il est prouvé qu'ils peuvent être porteurs et transmetteurs de virus poliomyélitiques par voie intestinale, et peut-être par d'autres voies.»

Dr Yves COUZIGOU.

«Depuis 1957, l'OMS ne recense dans les statistiques que les formes paralytiques de poliomyélite, alors qu'avant la vaccination, toutes les formes de polio étaient incluses, ce qui permet de faire apparaître une régression des cas qui est loin d'être vérifiée.»

Dr. SCHEIBNER, expert australien.

«Après l'échec retentissant du vaccin Salk (au Massachusetts, 75 % des cas paralytiques avaient reçu trois doses ou davantage du vaccin), une parade géniale fut trouvée pour sortir l'industrie du médicament du pétrin : on décida de nouvelles normes pour l'établissement du diagnostic de la polio.»

Pr. GREENBERG.

«Si le principe de la vaccination était concevable au début du 20e siècle du fait que le monde médical et scientifique ignorait pratiquement tout de la biologie moléculaire, des virus et rétrovirus endogènes et même exogènes et du principe de la recombinaison de ces derniers, il en va tout autrement depuis quelques décennies. Continuer à vacciner des populations entières -- des centaines de millions d'individus depuis 1978 -- constitue une erreur monumentale et un quasi-génocide.»

Dr Louis de Brouwer, Sida, le vertige.

«La vaccination est le modèle de l'incertitude, des interactions et relations imprévisibles. Elle se situe aux antipodes de l'esprit scientifique.»

Dr Jacques KALMAR.

«Dans plusieurs pays en voie de développement, la fréquence de ces maladies a augmenté, allant même jusqu'à quintupler depuis la vaccination.»

Pr Lépine, Médecine praticienne, n° 467.

«En réalité, la baisse de nombreuses maladies provient d’une meilleure hygiène et d’une meilleure nourriture qui ont permis de développer le système immunitaire.»

Peter Duesberg, professeur de biologie moléculaire et cellulaire à l'Université Berkeley.

«Un virus, même atténué, peut reprendre sa virulence; c'est notamment le cas du virus polio vaccinal, qui redevient pathogène après son passage dans l'intestin et contribue à contaminer l'entourage. Les cas de polio chez les contacts des vaccinés par le vaccin oral sont bien connus.»

Dr Garcia Silva, Le Maroc médical, n° 43.

«L'introduction volontaire et non nécessaire de virus infectieux dans un corps humain est un acte dément qui ne peut être dicté que par une grande ignorance de la virologie et des processus d'infection. Le mal qui est fait est incalculable.»

Pr R. Delong, virologue et immunologue de l'Université Toledo aux États-Unis.

«En 1945, la Hollande était le pays d'Europe le plus touché par la tuberculose. En 1974, sans jamais avoir eu recours au BCG, la maladie y était totalement éradiquée. A l'inverse, la tuberculose reprenait de la vigueur partout où le BCG est encore pratiqué.»

Bulletin statistique du ministère de la Santé publique et de la Sécurité sociale, n° 1, 1974.

«La présence d’un œdème cérébral chez des enfants en bas âge qui meurent peu de temps après une vaccination contre l’hépatite B est inquiétante. Les enfants de moins de 14 ans ont plus de chance de mourir ou de souffrir de réactions négatives après avoir reçu le vaccin de l’hépatite B que d’attraper la maladie.»

Dr. Jane ORIENT, médecin, directrice de l’Association des médecins et chirurgiens américains

«Une vaccination est toujours, biologiquement et immunitairement parlant, une offense contre l'organisme.»

Pr R. Bastin, Concours médical, 1er février 1986.

«Toute vaccination peut provoquer une encéphalite légère ou grave.»

Dr. Harris COULTER, Vaccination Social Violence and Criminality.

«Le pire vaccin de tous est celui contre la coqueluche. Il est responsable d'un grand nombre de morts et d'un grand nombre de dommages cérébraux irréversibles chez les nouveau-nés.»

Dr. Kalokerinos, Sunwell Tops, 24 mai 1987.

«Peu de médecins sont disposés à attribuer un décès ou une complication à une méthode qu’ils ont eux-mêmes recommandée et à laquelle ils croient.»

Pr. Georges DICK, British Medical Journal, juillet 1971.

«Les micro-organismes inoculés à travers toutes les barrières naturelles entra��nent chez la majorité des individus des pathologies chroniques dont les symptômes ne sont pas faciles à rattacher à leur cause initiale.»

Dr Jacqueline Bousquet.

«Ne vous hâtez pas de faire tomber la fièvre de votre malade ; s’il souffre d’une affection virale, vous risquez de compromettre sa guérison.»

Pr André LWOFF Prix Nobel de médecine.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shannen Doherty’s Untimely Death Sparks Important Conversations About Healthcare Access And Equity

By Janice Gassam Asare

Shannen Doherty, the actress best known for her roles in Beverly Hills, 90210 and Charmed has died after a long battle with cancer, at the age of 53. In a 2015 statement to People magazine, the actress revealed her breast cancer diagnosis, stating that she was “undergoing treatment” and that she was suing a firm and its former business manager for causing her to lose her health insurance due to a failure to pay the insurance premiums. According to reports, in a lawsuit Doherty shared that she hired a firm for tax, accounting, and investment services, among other things, and that part of their role was to make her health insurance premium payments to the Screen Actors Guild; Doherty claimed that their failure to make the premium payments in 2014 caused her health insurance to lapse until the re-enrollment period in 2015. When Doherty went in for a checkup in March of 2015, the cancer was discovered, at which time it had spread. In the lawsuit, Doherty indicated that if she had insurance, she would have been able to get the checkup sooner—the cancer would have been discovered, and she could have avoided chemotherapy and a mastectomy.

Under the IRS, actors are often classified as independent contractors, which comes with its own set of challenges. Although it is unclear what Doherty’s situation was, for many independent contractors, obtaining health insurance can be difficult. Trying to get health insurance as an independent contractor can be a costly and convoluted process. A 2020 Actors’ Equity Association survey indicated that “more than 80% of nonunion actors and stage managers in California have been misclassified as independent contractors.” A 2021 research study revealed that self-employment (which is what independent contractors are considered to be) was associated with a higher likelihood of being uninsured.

Doherty’s tragic situation invites a larger conversation about healthcare access and equity in the United States. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as “Obamacare,” was signed into law in 2010 and revolutionized healthcare access in two distinct ways: “creating health insurance marketplaces with federal financial assistance that reduces premiums and deductibles and by allowing states to expand Medicaid to adults with household incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level.” The ACA helped reduce the number of uninsured Americans and expanded healthcare access to those most in need. It also helped close gaps in coverage for different populations, including those with pre-existing health conditions, lower-income individuals, part-time workers, and those from historically excluded and marginalized populations.

Despite strides made through the ACA, healthcare access and equity are still persistent issues, especially within marginalized communities. Research from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) examining 2010-2022 data indicated that in 2022, non-elderly American Indian and Alaska Natives (AIAN) and Hispanic people had the greatest uninsured rates (19.1% and 18% respectively). When compared with their white counterparts, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islanders (NHOPI) and Black people also had higher uninsured rates at 12.7% and 10%, respectively. The Commonwealth Fund reported that between 2013 and 2021, “states that expanded Medicaid eligibility had higher rates of insurance coverage and health care access, with smaller disparities between racial/ethnic groups and larger improvements, than states that didn’t expand Medicaid.” It’s important to note that if a Republican president is elected, Project 2025, the far-right policy proposal document, seeks to upend Medicaid as we know it by introducing limits on the amount of time that a person can receive Medicaid.

When peeling back the layers to examine these racial and ethnic differences in more detail, the Brookings Institute noted in 2020 that the refusal of several states to expand Medicaid could be one contributing factor. One 2017 research study found that some underrepresented racial groups were more likely to experience insurance loss than their white counterparts. The study indicated that for Black and Hispanic populations, specific trigger events were more likely, as well as “socioeconomic characteristics” that were linked to more insurance loss and slower insurance gain. The study also noted that in the U.S., health insurance access was associated with employment and and marriage and that Black and Hispanic populations were “disadvantaged in both areas.”

Equity in and access to healthcare is fundamental, but bias is omnipresent. Age bias, for example, is a pervasive issue in breast cancer treatment. Research also indicates that racial bias is a prevalent issue—because the current guidelines in breast cancer screenings are based on white populations, this can lead to a delayed diagnosis for women from non-white communities. Our health is one of our greatest assets and healthcare should be a basic human right, no matter what state or country you live in. As a society, we must ensure that healthcare is available, affordable and accessible to all citizens. After all, how can a country call itself great if so many of its citizens, especially those most marginalized and vulnerable, don’t have access to healthcare?

#shannen doherty#breast cancer#health#health care#equity#usa#obamacare#affordable care act#project 2025#2024 shannen doherty#universal healthcare#poc#minorities#vulnerable people#first nations#marginalized people#medicaid#charmed#beverly hills 90210#health system#united states of america#article#2024 article#opinion

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

One-third of American kitchens have gas stoves—and evidence is piling up that they’re polluting homes with toxic chemicals. A study this summer found that using a single gas stove burner on high can raise levels of cancer-causing benzene above what’s been observed from secondhand smoke.

It turns out gas stoves have much more in common with cigarettes. A new investigation by NPR and the Climate Investigations Center found that the gas industry tried to downplay the health risks of gas stoves for decades, turning to many of the same public-relations tactics the tobacco industry used to cover up the risks of smoking. Gas utilities even hired some of the same PR firms and scientists that Big Tobacco did. Utilities were advised to “mount the massive, consistent, long-range public relations programs.”

Earlier this year, an investigation from DeSmog showed that the industry understood the hazards of gas appliances as far back as the 1970s and concealed what they knew from the public. The new documents fill in the details of how gas utilities and trade groups obscured the science around those health risks in an attempt to sell more gas stoves and avoid regulations—tactics still in use today.

The investigation comes amid a culture war over gas stoves. Towns across the country have passed bans on natural gas hookups in new buildings, and the federal Consumer Product Safety Commission is looking into their health hazards. The commission has said it doesn’t plan on banning gas stoves entirely after the mention of the idea sparked a backlash last December. That same month, a peer-reviewed study found that nearly 13 percent of childhood asthma cases in the United States were linked to using gas stoves. But the American Gas Association, the industry’s main lobbying group, argued that those findings were “not substantiated by sound science” and that even discussing a link to asthma was “reckless.”

It’s a strategy that goes back as far back as 1972, according to the most recent investigation. That year, the gas industry got advice from Richard Darrow, who helped manufacture controversy around the health effects of smoking as the lead for tobacco accounts at the public relations firm Hill + Knowlton. At an American Gas Association conference, Darrow told utilities they needed to respond to claims that gas appliances were polluting homes and shape the narrative around the issue before critics got the chance. Scientists were starting to discover that exposure to nitrogen dioxide—a pollutant emitted by gas stoves—was linked to respiratory illnesses. So Darrow advised utilities to “mount the massive, consistent, long-range public relations programs necessary to cope with the problems.”

The American Gas Association also hired researchers to conduct studies that appeared to be independent. They included Ralph Mitchell of Battelle Laboratories, who had also been funded by Philip Morris and the Cigar Research Council. In 1974, Mitchell’s team, using a controversial analysis technique, examined the literature on gas stoves and said they found no significant evidence that the stoves caused respiratory illness. In 1981, a paper funded by the Gas Research Institute and conducted by the consulting firm Arthur D. Little—also affiliated with Big Tobacco—surveyed the research and concluded that the evidence was “incomplete and conflicting.”

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

The FDA hasn’t approved them for gender dysphoria, and their effects are serious and permanent.

The fashion for transgenderism has brought with it a new euphemism: “gender-affirming care,” which means surgical and pharmacological interventions designed to make the body look and feel more like that of the opposite sex. Gender-affirming care for children involves the use of “puberty blockers”: one of five powerful synthetic drugs that block the natural production of sex hormones.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved those medications to treat prostate cancer, endometriosis, certain types of infertility and a rare childhood disease caused by a genetic mutation. But it has never approved them for gender dysphoria, the clinical term for the belief that one’s body is the wrong sex.

Thus the drugs, led by AbbVie’s Lupron, are prescribed to minors “off label.” (They are also used off-label for chemical castration of repeat sex offenders.) Off-label dispensing is legal; some half of all prescriptions in the U.S. are for off-label uses. But off-label use circumvents the FDA’s authority to examine drug safety and efficacy, especially when the patients are children. Some U.S. states have eliminated the need for parental consent for teens as young as 15 to start puberty blockers.

Proponents of puberty blockers contend there is little downside. The Department of Health and Human Services claims puberty blockers are “reversible.” It omits the evidence that “by impeding the usual process of sexual orientation and gender identity development,” these drugs “effectively ‘lock in’ children and young people to a treatment pathway,” according to a report by Britain’s National Health Service, which cites studies finding that 96% to 98% of minors prescribed puberty blockers proceed to cross-sex hormones.

Gender advocates also falsely contend that puberty blockers for children and teens have been “used safely since the late 1980s,” as a recent Scientific American article put it. That ignores substantial evidence of harmful long-term side effects.

The Center for Investigative Reporting revealed in 2017 that the FDA had received more than 10,000 adverse event reports from women who were given Lupron off-label as children to help them grow taller. They reported thinning and brittle bones, teeth that shed enamel or cracked, degenerative spinal disks, painful joints, radical mood swings, seizures, migraines and suicidal thoughts. Some developed fibromyalgia. There were reports of fertility problems and cognitive issues.

The FDA in 2016 ordered AbbVie to add a warning that children on Lupron might develop new or intensified psychiatric problems. Transgender children are at least three times as likely as the general population to have anxiety, depression and neurodevelopmental disorders. Last year, the FDA added another warning for children about the risk of brain swelling and vision loss.

The lack of research demonstrating that benefits outweigh the risks has resulted in some noteworthy pushback in the U.S. and abroad. Republican legislatures in a dozen states have curtailed or banned gender-affirming care for minors. Finland, citing concerns about side effects, in 2020 cut back puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to minors. Sweden followed suit in 2022 and Norway this year. Britain’s National Health Service shuttered the country’s largest youth gender clinic after 35 clinicians resigned over three years, complaining they were pressured to overdiagnose gay, mentally ill, and autistic teens and prescribe medications that made their conditions worse.

Still, the U.S. and most European countries embrace a standard of care that pushes youngsters toward “gender-affirming” treatments. It circumvents “watchful waiting” and talk therapy and diagnoses many children as gender dysphoric when they may simply be going through a phase.

Gender-affirming care for children is undoubtedly a flashpoint in America’s culture wars. It is also a human experiment on children and teens, the most vulnerable patients. Ignoring the long-term dangers posed by unrestricted off-label dispensing of powerful puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones, combined with the large overdiagnosis of minors as gender dysphoric, borders on child abuse.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m not sure how reliably I’ll be able to keep up with it, but I’ve been wanting to start posting weekly or monthly Good News compilations, with a focus on ecology but also some health and human rights type stuff. I’ll try to keep the sources recent (like from within the last week or month, whichever it happens to be), but sometimes original dates are hard to find. Also, all credit for images and written material can be found at the source linked; I don’t claim credit for anything but curating.

Anyway, here’s some good news from the first week of March!

1. Mexican Wolf Population Grows for Eighth Consecutive Year

““In total, 99 pups carefully selected for their genetic value have been placed in 40 wild dens since 2016, and some of these fosters have produced litters of their own. While recovery is in the future, examining the last decade of data certainly provides optimism that recovery will be achieved.””

2. “Remarkable achievement:” Victoria solar farm reaches full power ahead of schedule

“The 130MW Glenrowan solar farm in Victoria has knocked out another milestone, reaching full power and completing final grid connection testing just months after achieving first generation in late November.”

3. UTEP scientists capture first known photographs of tropical bird long thought lost

“The yellow-crested helmetshrike is a rare bird species endemic to Africa that had been listed as “lost” by the American Bird Conservancy when it hadn’t been seen in nearly two decades. Until now.”

4. France Protects Abortion as a 'Guaranteed Freedom' in Constitution

“[A]t a special congress in Versailles, France’s parliament voted by an overwhelming majority to add the freedom to have an abortion to the country’s constitution. Though abortion has been legal in France since 1975, the historic move aims to establish a safeguard in the face of global attacks on abortion access and sexual and reproductive health rights.”

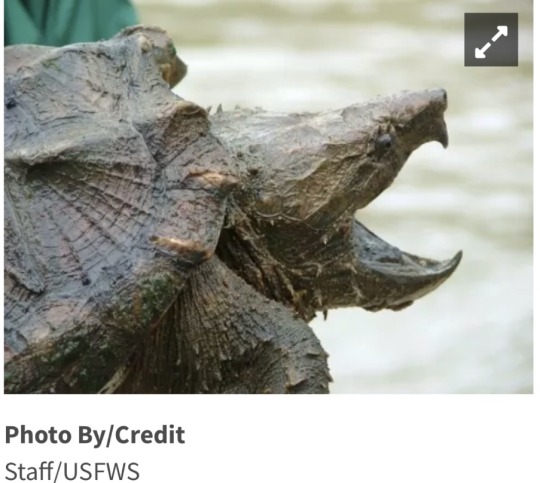

5. [Fish & Wildlife] Service Approves Conservation Agreement for Six Aquatic Species in the Trinity River Basin

“Besides conserving the six species in the CCAA, activities implemented in this agreement will also improve the water quality and natural flows of rivers for the benefit of rural and urban communities dependent on these water sources.”

6. Reforestation offset the effects of global warming in the southeastern United States

“In America’s southeast, except for most of Florida and Virginia, “temperatures have flatlined, or even cooled,” due to reforestation, even as most of the world has grown warmer, reports The Guardian.”

7. Places across the U.S. are testing no-strings cash as part of the social safety net

“Cash aid without conditions was considered a radical idea before the pandemic. But early results from a program in Stockton, Calif., showed promise. Then interest exploded after it became clear how much COVID stimulus checks and emergency rental payments had helped people. The U.S. Census Bureau found that an expanded child tax credit cut child poverty in half.”

8. The Road to Recovery for the Florida Golden Aster: Why We Should Care

“After a five-year review conducted in 2009 recommended reclassifying the species to threatened, the Florida golden aster was proposed for removal from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Plants due to recovery in June 2021, indicating the threats to the species had been reduced or eliminated.”

9. A smart molecule beats the mutation behind most pancreatic cancer

“Researchers have designed a candidate drug that could help make pancreatic cancer, which is almost always fatal, a treatable, perhaps even curable, condition.”

10. Nurses’ union at Austin’s Ascension Seton Medical Center ratifies historic first contract

“The contract, which NNOC said in a news release was “overwhelmingly” voted through by the union, includes provisions the union believes will improve patient care and retention of nurses.”

This and future editions will also be going up on my new Ko-fi, where you can support my art and get doodled phone wallpapers! EDIT: Actually, I can't find any indication that curating links like this is allowed on Ko-fi, so to play it safe I'll stick to just posting here on Tumblr. BUT, you can still support me over on Ko-fi if you want to see my Good News compilations continue!

#hopepunk#good news#wolf#wolves#mexican wolf#conservation#solar#solar power#birds#abortion#healthcare#abortion rights#reproductive rights#reproductive health#fish and wildlife#turtles#alligator snapping turtle#snapping turtle#river#reforestation#global warming#climate change#climate solutions#poverty#social safety net#flowers#endangered species#cancer#science#union

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

A novel radiation treatment for cancer with a 100-percent success rate in its pilot trial is now in Phase 3 pivotal trials ahead of receiving Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval.

Jerusalem-based startup Alpha TAU is expanding its trials of the treatment for skin and other cancer, after its first trial of 10 patients succeeded beyond the company’s expectations.

“Those patients got 100 percent CR [complete response],” Sofer says.

The pilot trial, conducted at multiple locations in the US last year, examined whether Alpha TAU’s DaRT (Diffusing Alpha-emitters Radiation Therapy) technology could successfully deliver targeted radiation therapy to patients with malignant skin and superficial soft tissue tumors that had returned or could not be removed surgically.

Alpha TAU had hoped that the treatment would be successful in at least seven of the 10 trial participants, but instead registered successful delivery to all 10. CT scans showed a 100 percent complete response rate at 12 weeks after the treatment and again at 24 weeks, with no evidence of the disease recurring in any of the subjects.

The results showed only mild or moderate side effects related to the device, and no systemic toxicity from it.

Radiation therapy for cancer normally uses beta and gamma particles. Alpha particles, while proving deadly for cancer cells in a tumor, are not traditionally used as they cannot travel far in solid masses.

Alpha DaRT, however, delivers the alpha particles directly into the tumor via a narrow device, inserted under local anesthetic, for a period of two to three weeks. The device is then removed and the patient monitored.

The findings of the pilot trial were published this month in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), months after submitting the results to the FDA.

The treatment is now undergoing its pivotal trial – the final one before the American agency gives it approval.

“We submitted the results that you see now to the FDA, and the FDA told us that we can submit the protocol for the last phase, the pivotal,” says Sofer.

A pivotal trial is required by the US and European Union drug agencies in order to receive approval to market a new form of medication; studies can involve thousands of subjects and test the efficacy and impact of a drug.

Sofer says that the successful findings of the trial has led to medical institutes around the world clamoring to work with Alpha TAU, but for now research is limited to just a handful of locations for the pivotal trial.

“Many, many, many centers all around the world want to participate,” he says. “We are working with 20 centers in the US, two or three centers in Canada and another four in Israel that are going to participate in this trial.”

youtube

Sofer says Alpha TAU will be ready to submit the findings of the pivotal trial in around a year and a half from now.

“We will have six months of follow up, then we will analyze the results and send it to the FDA,” he says of the current trial. “The submission to the FDA can be in about 18 months from now.”

The revolutionary treatment is also being tried on other cancers, according to Sofer, who clarifies that, “right now it’s only for solid tumors.”

“We’re working on pancreas and lung and breast [cancer],” he says, explaining that the company is currently at various stages of testing for these other forms of malignant tumors.

The device itself is easy to use and does not require specialized and often costly equipment in order to treat patients.

“When it is approved, it will be for any hospital, medical cancer center, all over the world,” Sofer explains.

“You don’t need any special equipment, and you don’t need the shielding,” he says, referring to the protective gear used in other forms of radiation therapy but are not needed for alpha particles.

“It will be very simple to implement. You don’t need special equipment or investment in capital expenditure or something like that, [just] regular tools.”

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Rachel Poser

Published: May 4, 2024

Ibram X. Kendi has a notebook that prompts him, on every other page, to write down “Things to be grateful for.” There are many things he might put under that heading. First and foremost, his wife and two daughters, and his health, having made it through Stage 4 colon cancer in his 30s — a diagnosis with a 12 percent survival rate. Tenure at Boston University, where Martin Luther King Jr. earned his doctorate in theology. A National Book Award, and a MacArthur “genius” grant for “transforming how many people understand, discuss and attempt to redress America’s longstanding racial challenges.” Then there were the millions of people who bought “How to Be an Antiracist,” the first of five of his books to take the No. 1 spot on the New York Times best-seller list. But he was particularly grateful to the readers who wrote to him to say his work changed them for the better.

These days, he could use the reminder. Four years have gone by since George Floyd was murdered on the pavement near Cup Foods in Minneapolis, sparking the racial “reckoning” that made Kendi a household name. Many people, Kendi among them, believe that reckoning is long over. State legislatures have pushed through harsh antiprotest measures. Conservative-led campaigns against teaching Black history and against diversity, equity and inclusion programs are underway. Last June, the Supreme Court struck down affirmative action in college admissions. And Donald Trump is once again the Republican nominee for president, promising to root out “the radical-left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country.”

Kendi has become a prime target of this backlash. Books of his have been banned from schools in some districts, and his name is a kind of profanity among conservatives who believe racism is mostly a problem of the past. Though legions of readers continue to celebrate Kendi as a courageous and groundbreaking thinker, for many others he has become a symbol of everything that’s wrong in racial discourse today. Even many allies in the fight for racial justice dismiss his brand of antiracism as unworkable, wrongheaded or counterproductive. “The vast majority of my critics,” Kendi told me last year, “either haven’t read my work or willfully misrepresent it.”

Criticism of Kendi only grew in September, when he made the “painful decision” to lay off more than half the staff of the research center he runs at Boston University. The Center for Antiracist Research, which Kendi founded during the 2020 protests to tackle “seemingly intractable problems of racial inequity and injustice,” raised an enormous sum of $55 million, and the news of its downsizing led to a storm of questions. False rumors began circulating that Kendi had stolen funds, and the university announced it would investigate after former employees accused him of mismanagement and secrecy.

The controversy quickly ballooned into a national news story, fueled in large part by right-wing media, which was all too happy to speculate about “missing funds” and condemn Kendi — and the broader racial-justice movement — as a fraud. On Fox News, the conservative activist Christopher Rufo told the host John Roberts that the center’s “failure” was “poetic justice.” “This is a symbol of where we have come since 2020 and why that movement is really floundering today,” he said. In early October, a podcast affiliated with the Manhattan Institute, the conservative think tank where Rufo works, jubilantly released an episode titled “The End of Ibram X. Kendi?”

In December, I met Kendi at the Center for Antiracist Research, which was by then mostly empty, though I caught signs of its former life: Space heaters sat idly under desks, and Post-it notes lingered around the edges of unplugged monitors. On the frame of one cleared-out cubicle, a sticker in the shape of Earth read “Be the change.” Kendi welcomed me into his office in a pink shirt and a periwinkle blazer with a handkerchief tucked neatly in its pocket. He was calm on the surface, but he seemed to me, as he often did during the conversations we’d had since the layoffs, to be holding himself taut, like a tensile substance under enormous strain. The furor over the center, he said, was a measure of how desperate many people were to damage his reputation: “If this had happened at another center, it would either not have been a story or a one-day story.”

In “How to Be an Antiracist,” his best-known book, Kendi challenges readers to evaluate themselves by their racial impact, by whether their actions advance or impede the cause of racial equality. “There is no neutrality in the racial struggle,” he writes. “The question for each of us is: What side of history will we stand on?” This question evinces Kendi’s confidence that ideas and policies can be dependably sorted into one of two categories: racist or antiracist.

Kendi is a vegan, a tall man with a gentle, serious nature. “He’ll laugh at a joke — he’ll never crack one,” Kellie Carter Jackson, the chair of the Africana studies department at Wellesley and someone who has known Kendi for years, told me. He considers himself an “introvert and loner” who was chased down by the spotlight and is now caught in its glare. “I don’t know of anybody more ill suited for fame than Ibram Kendi,” said Stefan Bradley, a longtime friend and professor of Black studies at Amherst. There is a corniness to Kendi that’s endearing, like his use of the gratitude notebook — a thick, pastel-colored pad with gold spiral binding — or the fact that his phone email signature is “Sent from Typoville aka my iPhone.” Though he is always soft-spoken, volume sometimes seems to be a gauge of how comfortable he feels. The first time I met him in person, he greeted me so quietly that I worried my recorder wouldn’t pick up his voice.

Kendi had hired a pair of crisis-P.R. consultants to help him manage the fallout from the layoffs, a controversy that he believed had fed into dangerous, racist stories about Black leaders, and about him in particular. In the fun-house mirror of conservative media, Kendi has long loomed as an antiwhite extremist trying to get rich by sowing racial division. Kendi told me he received regular threats; he allowed me to come to the center only on the condition that I not reveal its location. “When it comes to the white supremacists who are the greatest domestic terrorist threat of our time, I am one of their chief enemies,” he told me.

Boston University had recently released the results of its audit, which found “no issues” with how the center’s finances were handled. The center’s problem, Kendi told me, was more banal: Most of its money was in its endowment or restricted to specific uses, and after the high of 2020, donations had crashed. “At our current rate, we were going to run out in two years,” he said. “That was what ultimately led us to feel like we needed to make a major change.” The center’s new model would fund nine-month academic fellowships rather than a large full-time staff. Though inquiries into the center’s grant-management practices and workplace culture were continuing, Kendi was confident that they would absolve him, too. In the media, he’d dismissed the complaints about his leadership as “unfair,” “unfounded,” “vague,” “meanspirited” and an attempt to “settle old scores.”

In the fall, when I began talking to former employees and faculty — most of whom asked for anonymity because they remain at Boston University or signed severance agreements that included nondisparagement language — it was clear that many of them felt caught in a bind. They could already see that the story of the center’s dysfunction was being used to undermine the racial-justice movement, but they were frustrated to watch Kendi play down the problems and cast their concerns as spiteful or even racist. They felt that what they experienced at the center was now playing out in public: Kendi’s tendency to see their constructive feedback as hostile. “He doesn’t trust anybody,” one person told me. “He doesn’t let anyone in.”

To Kendi, attacks from those who claim to be allies, like attacks from political enemies, are to be expected. In his books, Kendi argues that history is not an arc bending toward justice but a war of “dueling” forces — racist and antiracist — that each escalate their response when the other advances. In the years since 2020, he believes, the country has entered a predictable period of retrenchment, when the force of racism is ascendant and the racial progress of the last several decades is under threat. To defend antiracism, to defend himself, he would simply have to fight harder.

Not so long ago, Kendi thought he saw a new world coming into being. “We are living in the midst of an antiracist revolution,” he wrote in September 2020 in an Atlantic cover story headlined, “Is This the Beginning of the End for American Racism?” Nearly 20 percent of Americans were saying that “race relations” was the most urgent problem facing the nation — more than at any point since 1968 — and many of them were turning to Kendi to figure out what to do about it. They were buying his memoir and manifesto, “How to Be an Antiracist,” much of which he wrote while undergoing chemotherapy. “This was perhaps the last thing he was going to write,” Chris Jackson, Kendi’s editor, told me. “There was no cynicism in the writing of it.” (Jackson was the editor of a 2021 book based on The 1619 Project, which originated in this magazine in 2019; Kendi contributed a chapter to that book.)

Kendi confesses in the introduction that he “used to be racist most of the time.” The year 1994, when he turned 12, marked three decades since the United States outlawed discrimination on the basis of race. Then why, Kendi wondered as an adolescent, were so many Black people out of work, impoverished or incarcerated? The problem, he concluded, must be Black people themselves. Not Black people like his parents, God-loving professionals who had saved enough to buy a home in Jamaica, Queens, and who never let their two sons forget the importance of education and hard work. But they were the exception. In high school, Kendi competed in an oratory contest in which he gave voice to many of the anti-Black stereotypes circulating in the ’90s — that Black youths were violent, unstudious, unmotivated. “They think it’s OK to be the most feared in our society,” he proclaimed. “They think it’s OK not to think!” Kendi also turned these ideas on himself, believing that he was a “subpar student” because of his race.

Kendi’s mind began to change when he arrived on the campus of Florida A&M, one of the largest historically Black universities in the country, in the fall of 2000 to study sports journalism. “I had never seen so many Black people together with positive motives,” he wrote at the time. Kendi was disengaged for most of high school, as concerned with his clothes as his grades. His friends at the university teased him for joining a modeling troupe and preening before parties, particularly because once he got to them he was too shy to talk to anyone. “He would come out, and you could smell the cologne from down the hall,” Grady Tripp, Kendi’s housemate, told me. But experimenting with his style, for Kendi, was part of trying on new ideas. For a while, he wore honey-colored contact lenses that turned his irises an off-putting shade of orange; he got rid of them once he decided they were a rejection of blackness, like Malcolm X’s straightening his hair with lye.

Over long hours spent reading alone in the library, Kendi found his way to some unlikely conclusions. In “How to Be an Antiracist,” he describes bursting into his housemate’s room to declare that he had “figured white people out.” “They are aliens,” he said. Kendi had gone searching for answers in conspiracy theories and Nation of Islam theology that cast whites as a “devil race” bred by an evil Black scientist to conquer the planet. “Europeans are simply a different breed of human,” he wrote in a column for the student newspaper in 2003. They are “socialized to be aggressive” and have used “the AIDS virus and cloning” to dominate the world’s peoples. Recently, the column has circulated on right-wing social media as evidence of Kendi’s antiwhite extremism, which frustrates him because it’s in his own memoir as an example of just how lost he had become.

Kendi went on to earn a Ph.D. in African American studies from Temple University. The founder of his department was Molefi Kete Asante, an Afrocentrist who has called on the descendants of enslaved people to embrace traditional African dress, languages and religions. Kendi eventually changed his middle name to Xolani, meaning “peace” in Zulu; at their wedding, he and his wife, Sadiqa, adopted the last name Kendi, meaning “loved one” in Meru. Kendi has called Asante “profoundly antiracist,” but Kendi remained an idiosyncratic thinker who did not consider himself a part of just one scholarly tradition; he knew early on that he wanted to write for the public. In a 2019 interview, when asked about his intellectual lineage, Kendi named W.E.B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells and Malcolm X.

Kendi became part of a cohort of Black writers, among them Nikole Hannah-Jones and Ta-Nehisi Coates, who, through the sunset of the Obama presidency and the red dawn of the MAGA movement, argued that anti-Blackness remains a major force shaping American politics. They helped popularize the longstanding idea that racism in the United States is systemic — that the country’s laws and institutions perpetuate Black disadvantage despite a pledge of equal treatment. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended de jure white supremacy, but President Lyndon B. Johnson, who signed it into law, acknowledged that it wouldn’t uproot a racial caste system grown over centuries.

“The next and the more profound stage of the battle for civil rights,” he said, would be to achieve “not just equality as a right and a theory but equality as a fact.” Kendi and others wrote bracingly about the failure of that promise. Far from economic redress, Black Americans were met with continued discrimination in every realm of life, while being told the country was now “colorblind.” Kendi and others argued that remedying the impact of hundreds of years of subjugation would require policies that recognize, rather than ignore, that legacy, such as affirmative action and reparations.

Far too many Americans, Kendi felt, still thought of racism as conscious prejudice, so conversations got stuck in cul-de-sacs of denial, in which people protested that they were “not racist” because they harbored no anti-Black animus. To convey this, he landed on the binary that would become his most famous and perhaps most controversial idea. “There is no such thing as a not-racist idea” or a “race-neutral policy,” he wrote in “How to Be an Antiracist,” published in 2019. “The opposite of ‘racist’ isn’t ‘not racist.’ It is ‘antiracist.’”

Black activists have long used the word “antiracist” to describe active resistance to white supremacy, but “How to Be an Antiracist” catapulted the term into the American lexicon, in much the same way that Sheryl Sandberg turned “Lean In” into a mantra. After George Floyd’s death, the book sold out on Amazon, which was “unheard-of,” Kendi said. Media coverage of Kendi in those days made him sound nearly superhuman. In a GQ profile, for example, the novelist ZZ Packer describes Kendi as a “preternaturally wise” Buddha-like figure, “the antiracist guru of our time” with a “Jedi-like prowess for recognizing and neutralizing the racism pervading our society.”

During the summer of 2020, Kendi sometimes appeared onstage or onscreen alongside Robin DiAngelo, the educator whose book “White Fragility” was also a No. 1 best seller. Kendi and DiAngelo write less about the workings of systemic racism than the ideas and psychological defenses that cause people to deny their complicity in it. They share a belief in what Kendi calls “individual transformation for societal transformation.” When Kendi took over Selena Gomez’s Instagram, for example, he urged her 180 million followers to “1. Acknowledge your racism,” “2. Confess your racist ideas” and “3. Define racism and antiracism.” Then they would be ready for Steps 4 and 5, identifying and working to change racist policies.

Kendi and DiAngelo’s talk of confession — antiracism as a kind of conversion experience — inspired many people and disturbed others. By focusing so much on personal growth, critics said, they made it easy for self-help to take the place of organizing, for a conflict over the policing of Black communities, and by extension their material conditions, to become a fight not over policy but over etiquette — which words to use, whether to say “Black Lives Matter” or “All Lives Matter.” Many allies felt that Kendi and DiAngelo were merely helping white people alleviate their guilt.

They also questioned Kendi’s willingness to turn his philosophy into a brand. Following the success of “How to Be an Antiracist,” he released a deck of “antiracist” conversation-starter cards, an “antiracist” journal with prompts for self-reflection and a children’s book, “Antiracist Baby.” Christine Platt, an author and advocate who worked with Kendi at American University, recently co-wrote a novel that features a Kendi-like figure — a “soft-spoken” author named Dr. Braxton Walsh Jr., whose book “Woke Yet?” becomes a viral phenomenon. “White folks post about it on social media all the time,” rants De’Andrea, one of the main characters. “Wake up and get your copy today! Only nineteen ninety-nine plus shipping and handling.”

Those who thought of him as a self-help guru, Kendi felt, simply hadn’t read his work. Like most scholars of race, Kendi believes that Blackness is a fiction born of colonial powers’ self-interest, not just ignorance or hate, meaning that combating racism today requires upending the economic and political structures that propagate it. But Kendi doesn’t like the term “systemic racism” because it turns racism into a “hidden and unknowable” force for which there’s no one to blame, so he prefers to talk about “racist policies.”

In The Atlantic, he warned against the country going down a path of symbolic change where “monuments to racism are dismantled, but Americans shrink from the awesome task of reshaping the country with antiracist policies,” like Medicare for All, need-based school funding and reparations. Changing policy was exactly what he aimed to do at Boston University. During the protests, in the summer of 2020, the university named Kendi the Andrew W. Mellon professor of the humanities, a chair previously held by the Nobel Peace Prize winner Elie Wiesel, and announced the creation of a center on campus to put his ideas into action. Donations came pouring in, led by an anonymous $25 million gift and a $10 million gift from the Twitter founder Jack Dorsey, which the provost said would give Kendi “the resources to launch the center like a rocket ship.”

Kendi started the center from his home in Boston, while Sadiqa, a pediatric E.R. doctor, came and went from the hospital in full protective gear. Kendi ran a research center as part of his old job at American University, but he felt unable to make a meaningful impact because the resources were modest and he was diagnosed with cancer just four months after its founding. Now, granted tens of millions of dollars to enact his most ambitious ideas, Kendi was determined to create an organization that could be a real engine of progress. “We’ve got to build an infrastructure to match what the right has created,” he later told a co-worker. “We’ve got to build something equally powerful.”

Kendi’s two centers were part of a wave of racial-justice spaces being founded at universities, like the Thurgood Marshall Civil Rights Center at Howard or the Ida B. Wells Just Data Lab at Princeton, that pledged to work in partnership with activists and community groups to achieve social change. Kendi envisioned an organization that supported people of color in campaigning for policies that would concretely improve their lives.

To reflect that mission, he designed a structure with four “pillars” or offices: Research, Policy, Narrative and Advocacy. He recruited data scientists, policy analysts, organizers and educators and brought in faculty members working on race from across the university. They set up a model-legislation unit, which would draft sample bills and public-comment notes; an amicus-brief practice, which would target court cases in which race was being overlooked as an issue; and a grant process to fund research on racism by interdisciplinary teams elsewhere at the university, among other programs. Kendi also struck up a partnership with The Boston Globe to revive The Emancipator, a storied abolitionist newspaper. “It was a really exciting time,” he told me.

That summer, however, Kendi found himself on the defensive beyond Boston as Republican book-banning campaigns revved up. On Fox News, Tucker Carlson denounced “How to Be an Antiracist” as “poisonous,” plucking out Kendi’s summary of the case for race-conscious policymaking, which sounded particularly maladroit when taken out of context: “The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination,” Carlson read in mock disbelief. “In other words, his book against racism promotes racism.” This was around the same time that Rufo, the conservative activist, started to position Kendi as a leading proponent of critical race theory, a school of thought, Rufo told The New Yorker, that he discovered by hunting through the footnotes of “How to Be an Antiracist.”

Critical race theorists were a group of legal scholars in the 1970s and ’80s who documented ways that the American legal framework of racial equality was nevertheless producing unequal treatment. They elaborated the idea of systemic racism and the critique of “colorblindness” that inform much of the writing of Kendi’s cohort. Rufo wrote on Twitter that his goal was to change the meaning of the term “critical race theory” — to “turn it toxic” by putting “all of the various cultural insanities under that brand category.” In his attacks on Kendi, Rufo also amplified the left’s critique of Kendi’s corporate-friendliness, caricaturing Kendi as a grifter out to enrich himself by raking in speaking fees. The number of threatening messages Kendi received began to rise. “I don’t feel safe anywhere,” Kendi later told a colleague. “I’m constantly looking over my shoulder.”

By the time the academic year began, in the fall of 2021, Kendi decided to take extraordinary measures. Before the center began in-person work that September, Kendi sent the staff an email about “security protocols,” instructing them to conceal the location of the center even from other Boston University faculty members and students. “It is critical to not share the address of the center with anyone or bring anyone to the center,” Kendi wrote. The email included a mock script to be used in the event of an inquiry about the center’s location, which ended abruptly with, “I gotta go.”

Though such precautions felt necessary to Kendi, they were met with incredulity and frustration by some employees who were starting to question his leadership. Problems emerged within the first six months, according to more than a dozen staff and faculty members I interviewed. Some told me they had gone to the center because they considered Kendi a visionary; others had reservations about or flat-out disagreements with his work but believed he had brought much-needed attention to issues they cared about. They would be able to find common ground, they thought. They were ready for some chaos as they tried to spin up a new organization remotely, but they quickly ran into difficulty as they tried to execute some of Kendi’s plans.

Kendi emphasizes in his books that policies alone are the cause of racial disparities today. In “Stamped From the Beginning,” his 2016 history of anti-Black ideas from the 15th century to the Obama presidency — which won the National Book Award and was recently made into a Netflix documentary that made the Oscar shortlist — Kendi writes that blaming Black people for their own oppression, by implying that Black people or Black culture are inferior or pathological, was one of the oldest cons in America. He had witnessed it again during the early days of the pandemic, when the numbers suggested that Black people were dying from Covid faster than every racial group save Native Americans. Some pundits speculated about the “soul food” diet or posited that Black communities weren’t taking the virus seriously, even though a Pew survey found that Black respondents were most likely to view the coronavirus as a major threat.

Kendi wanted the center to build “the nation’s largest online collection” of racial data to track disparities like this one and do analytical work to understand each policy responsible. In the case of Covid, for example, Black Americans are disproportionately likely to work in low-income essential jobs, to live in crowded conditions and to lack access to high-quality insurance or medical care. The center might research these conditions and propose targeted interventions, like changes to Medicaid coverage, or more transformative measures, like a universal basic income. One faculty member involved told me that she was “initially incredibly enthusiastic” about the idea. “It seemed like an opportunity to do rigorous, well-funded social-science research that would be aimed at real policy change on issues that I cared about,” she told me.

Like Kendi, his staff believed that historical oppression and ongoing discrimination explained why Black Americans fared comparatively poorly on so many measures of well-being, from education to wealth to longevity, and that centuries of injustice demanded a sweeping policy response to remedy. But understanding that past and present racism is the underlying cause of Black disadvantage is different from the work of assessing its role in any single policy, let alone figuring out how to change the policy to eliminate it. That takes careful analysis. “You have to have specificity,” the faculty member said, “or you can’t measure.”

Kendi pushed back at staff members who argued that the center should constrain its focus. There were plenty of academic centers and researchers that tracked data on racial disparities in one policy area or another, he said; he wanted to convene that pre-existing data, bringing it together in one place for easy access by the public. In a 2022 meeting, when the team tried to get a better sense of his vision, Kendi told them that he wanted a guy at a barbershop or a bar to be able to “pull up the numbers.” To many employees with data or policy backgrounds, what Kendi wanted didn’t seem feasible; at worst, they thought, it risked simply replicating others’ work or creating a mess of sloppily merged data, connected to too many policies for their small team to track rigorously. In the midst of the pandemic, the center struggled to hire a director of research who might have been able to mediate the dispute.

In November, a confidential complaint was filed with the university administration raising concerns about Kendi’s leadership. The anonymous employee told a university compliance officer that Kendi ran the center with “hypercontrol” and created an environment of “silence and secrecy” that was causing low morale and high turnover, claiming that “when Dr. Kendi is questioned, the narrative becomes that the employee must be the one with the ‘problem.’” The employee warned the university that the situation “is potentially going to blow up.”

One of Kendi’s refrains is that being antiracist demands self-criticism. “If I share an idea that people don’t understand, I’m to blame,” he told an interviewer in 2019. “I’m always to blame.” Kendi told me that his most productive conversations with critics of his ideas often happened in private, including one with a prominent Black thinker who inspired him to make a change in the revised edition of “How to Be an Antiracist.” “This person talked about how the goal should not just be equity,” Kendi said. “The goal should not be the same percentage of Black people being killed by police as white people. The goal should be no one being killed by police.” But some Black scholars, as the right-wing backlash strengthened, debated whether to make their criticisms in public. The philosopher Charles Mills, after listening to a graduate-student presentation about Kendi and DiAngelo at a conference in 2021, asked the presenter: “Are their views now sufficiently influential, or perhaps sufficiently harmful, that we should make them a part of the target?”

Kendi was frustrated to be constantly lumped in with DiAngelo, whose ideas diverge from his in important ways. DiAngelo considers “white identity” to be “inherently racist,” while Kendi argues that anyone, including Black people, can be racist or antiracist. That puts him at odds with an understanding — common in the academy and the racial-justice movement — that Black people can’t be racist because racism is a system of power relations, and that Black people as a group don’t have the structural means to enforce their prejudice; this notion is often phrased as a formula, that racism is “prejudice plus power.”

Kendi thinks of “racist” not as a pejorative but as a simple word of description. His reigning metaphor is the sticker. Racist and antiracist are “peelable name tags,” Kendi writes; they describe not who we are but who we are being in any particular moment. He says he opposes the censoriousness that has become the sharp edge of identity politics, because he doesn’t regard shame as a useful social tool. But he has no intention of taking the moral sting out of “racist” completely. “I wouldn’t say that a person is not being condemned when they’re being called a racist,” he told Ezra Klein in a 2019 interview.

Rather than replacing one definition of racism with another, Kendi is really joining two senses into one. For much of the 20th century, the white mainstream considered racism a personal moral issue, while Black civil rights activists, among others, argued that it’s also structural and systemic. In his definition, Kendi aims to connect the individual to the system. A “racist,” he writes, is “one who is expressing an idea of racial hierarchy, or through actions or inaction is supporting a policy that leads to racial inequity or injustice.”

Kendi’s focus on outcomes is not new. For decades, civil rights activists have brought lawsuits based on the legal theory of “disparate impact,” which holds that unequal outcomes prove that certain practices (by, for example, an employer or a landlord) are racially discriminatory, without evidence of malicious intent. Kendi’s definition urges us to perform this sort of disparate-impact analysis all the time. In Politico in 2020, Kendi proposed the creation of a federal agency that would clear every new policy — local, state or federal — to ensure that it wouldn’t increase racial disparities. But as his team at the center knew well, policies can have complicated effects. Let’s say that a local environmental policy would improve the air quality in Black neighborhoods near factories but would also lead to hundreds of lost jobs and worsen the area’s racial wealth gap. Should it be cleared? Is such a policy racist or antiracist?

The question is made even trickier by the fact that the racial impact of many policies might not become clear until years later. The legacy of desegregation, for example, shows that even a profoundly antiracist policy can be turned against itself in its implementation. This is what the term “systemic racism” captures that can be lost in Kendi’s translation of “racist policies.”

In “Stamped From the Beginning,” Kendi writes that “racist policy is the cause of racial disparities in this country and the world at large.” Mary Pattillo, a sociologist at Northwestern, told me that Kendi’s focus on race didn’t fully capture the complexity of social life — the roles of class, culture, religion, community. “No one variable alone explains anything,” she said. But she thought there was value in simplifying. She understood Kendi not as an official making policy but as a thought leader making a “defensible, succinct provocation.” “We live in a country whose ideology is very individualistic, so the standard response to any failure is individual blame,” she said. “Those of us who do recognize the importance of policies, laws and so on have to always push so hard against that that we have to make statements like the one that Kendi is making.”