#also the fact that people are ignoring the clear protagonists of the film

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Another interesting article about the new Ghibli film Boy and the Heron with great insights into Miyazaki’s relationship with Joe Hisaishi and Toshio Suzuki making films over the years. Again it has a few spoilers

What’s it like to work with Hayao Miyazaki? Go behind the scenes.

News of Hayao Miyazaki’s retirement can’t ever be trusted.

The Japanese animation master’s repeated claims that he’ll give up filmmaking are a response to the strain that creating each of his largely hand-drawn universes entails. At least that’s what Toshio Suzuki, a founder of Studio Ghibli and Miyazaki’s right-hand man for the past 40 years, believes.

"Every time he finishes a film, he’s so exhausted he can’t think about the next project,” Suzuki explains. "He’s used up his energy physically and mentally. He needs some time to clear his mind. And to have a blank canvas to come up with new ideas.”

A decade after 2013’s "The Wind Rises” was heralded as Miyazaki’s final film, the 82-year-old auteur’s newest feature, "The Boy and the Heron,” is being released in the United States after major success in Japan over the summer, where it opened without any traditional publicity.

Though the director hasn’t given any interviews about "The Boy and the Heron,” Suzuki, 75, who is also a veteran producer, and Joe Hisaishi, 72, the longtime composer on Miyazaki’s movies, describe in separate video interviews the master’s working process and how their collaborations have evolved — or not — over the years.

Suzuki is casually dressed and speaking, via an interpreter, from Japan, where he sits next to a pillow emblazoned with Totoro, the bearlike troll that serves as the studio’s logo. He says the new fantasy film is Miyazaki’s most personal yet. Set in the final days of World War II, the tale follows 11-year-old Mahito, who, after losing his mother in a fire, moves to the countryside, where a magical realm beckons him.

"At the start of this project, Miyazaki came to me and asked me, ‘This is going to be about my story, is that going to be OK?’ I just nodded,” Suzuki recalls with the matter-of-factness of someone who’s learned it would be futile to stand in the way of the director.

For a long time, he says, Miyazaki worried that if he made a movie about a young male, inspiration would inevitably be drawn from his own childhood, which he felt might not make for an interesting narrative. Growing up, Miyazaki had trouble communicating with people and expressed himself instead by drawing pictures.

"I noticed that with this film, where he portrayed himself as a protagonist, he included a lot of humorous moments in order to cover up that the boy, based on himself, is very sensitive and pessimistic,” Suzuki says. "That was interesting to see.”

If Miyazaki is the boy, Suzuki adds, then he himself is the heron, a mischievous flying entity in the story that pushes the young hero to keep going. Director Isao Takahata, Studio Ghibli’s third foundational musketeer, who died in 2018, is represented onscreen by Granduncle, a wise but weathered figure who controls the fantastical world Mahito ventures into.

Suzuki first met Miyazaki in the late 1970s, when the animator was making his first feature, "Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro,” an amusing caper. Back then, Suzuki was a journalist hoping to interview him.

But Miyazaki, who was working on a storyboard, had no interest in talking and ignored him. "Out of kindness, I thought it was a good thing to introduce his works to my readers, and for him to be very cranky and disrespectful, I was very angry,” Suzuki remembers.

He stuck around the studio for two more days of silence. On the third, Miyazaki asked him if he knew a term for a car overtaking another during a chase. Suzuki’s reply, a specific Japanese expression for such action, finally broke the ice and kick-started their long-term relationship.

"Miyazaki still remembers that first meeting, too,” Suzuki says. "He thought that I was a person not to be trusted. And that’s why he was very cautious about talking to me.”

Over the years, Suzuki has become increasingly indispensable for Miyazaki. "He always tells me, ‘Suzuki-san, can you remember the important things for me?’ And then he feels that he can forget about all the important things not concerning his films. I have to remember them for him,” Suzuki says.

Best friends more than mere collaborators, Miyazaki and Suzuki talk every day, even if there’s nothing urgent to discuss, and make it a rule to meet in person on Mondays and Thursdays. "What we talk about is very trivial most times, I guess he feels lonely or misses me, but it’s always him who calls me. I never call him,” Suzuki says, adding with a laugh, "Sometimes he even calls me in the middle of the night, like at 3 a.m., and the first thing he says is, ‘Were you awake?’ And obviously I was not. I’m in bed!”

In contrast, Hisaishi, the composer who first worked with Miyazaki on the 1984 feature "Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind,” has a strictly professional relationship with him.

"We don’t see each other in private,” Hisaishi, wearing an elegant sweater, says through a translator. "We don’t eat together. We don’t drink together. We only meet to discuss things for work.” That emotional distance, he adds, is what has made their partnership over 11 films so creatively fruitful.

"People think that if you really know a person’s full character then you can have a good working relationship, but that doesn’t necessarily hold true,” Hisaishi says. "What is most important to me is to compose music. The most important thing in life to Miyazaki is to draw pictures. We are both focused on those most important things in our lives.”

On "The Boy and the Heron,” Miyazaki didn’t provide Hisaishi with any instruction. The musician watched the film only when it was nearly completed but still with no sound or dialogue. At that point Miyazaki simply said to Hisaishi, "I just leave it up to you.”

"I feel he was just thinking that he could rely on me and expected me to come up with something,” Hisaishi says. "I feel like I was very much trusted to do this.”

For all of their previous collaborations, Miyazaki would bring on Hisaishi to discuss once three out of the four or five parts of the storyboard for a new film were ready. That the process changed this time was possible only because of their shared history.

"It’s as if we’ve been Olympic athletes making a film once every four years for 40 years,” Hisaishi says. "It’s been a long time of training and performing. When I look back I’m amazed that I could write music for these very different films.”

In his contemporary classical work, Hisaishi had been working on minimalist compositions with repeating patterns, and he took that approach to the new film.

While he maintains they are just colleagues, every January for the past 15 years, Hisaishi has composed a small tune, recorded it on a piano and sent it to Miyazaki as a birthday present. This tradition has now become the seasoned musician’s lucky charm.

"After about three times I thought, ‘This has probably run its course,’” Hisaishi recalls. "I didn’t send one the following year. That whole year I wasn’t able to work very well. It was sort of a jinx that I had not sent him something, so I started sending him the music again for his birthday,” he adds with a laugh.

Both Hisaishi and Suzuki say their interactions with Miyazaki have not changed much over the decades. On the contrary, the men have become staunch creatures of habit.

Asked why his profound connection with Miyazaki has endured so long, Suzuki says: "I don’t necessarily agree, but he once told me, ‘I’ve never met someone so similar to me. You are the last person that I will meet like that.’”

BY CARLOS AGUILAR

THE NEW YORK TIMES

256 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi!!! i saw ur fall guy ficlet post, and i got so excited because THESE ARE SO CUTE

this is a lot to ask lmao im so sorry but what if

F (friendship) but then its a friends to lovers story with G (gentle) + H (hugs) + J (jealousy)?

THIS IS SO MUCH TO ASK BUT I JUST KNOW YOU'D ROCK THIS

thank youuu and hope ur having a great day!! <33

Hi, thank you for being my first ask!!! And hell yeah you can ask for a mix of prompts, although I wrote more of a very short fic than distinct prompts. I hope that's okay!

Being an intimacy coordinator was a job that constantly kept you on your toes - never more so when the intimate scene you were coordinating involved multiple people.

In this case, the director of this film had this ‘Mr & Mrs Smith’-esque scene in mind where the two protagonists went from fighting to making out back to fighting and then into a sex scene – and since the fight scenes were very intense, that meant you were not only working with the actors, but also their stunt doubles.

Not that you were complaining.

As ‘not actors’, you had been hanging out with a few of the stunt actors while on set – particularly the stunt double for the lead male role in this film, Colt. And Colt was an absolute sweetheart.

He’d looked after you since it was your first international shoot: riding with you to set in the mornings, going exploring around the city with you, making sure you got home safely before heading to his own hotel. He was also a bit of a gentle giant: guiding you around with a big hand on the small of your back, slinging an arm around your shoulder to support you on public transport so you didn’t fall over, holding your hand to help you out of the truck he drove to and around set.

Despite him having muscles that were ridiculous impressive, and a rough and tumble nature that meant he was constantly bruised and scraped before he started work, you always felt safe around Colt.

The fact he was easy to look at didn’t hurt, either.

You never voiced that thought aloud; as an intimacy coordinator, especially one who was assisting with scenes involving Colt himself, telling him you found him attractive would be crossing a major line. You didn’t want anyone calling into either of your professionalisms, especially when a lot of this work came about through word of mouth…but that didn’t mean you were blind.

Or adverse to asking him out after filming had wrapped up.

Some people on set, though, were not as firm on professional boundaries as you were.

The male lead for this film, some hot new star named Johnny, had been flirting with you since the first day he’d seen you on set. It wasn’t subtle, but you tried to ignore it as much as you could, striving to remain professional but polite.

Unfortunately, Johnny seemed to interpret ‘polite’ as ‘playing hard to get (but obviously into it)’. He really wasn’t doing anything to dispel the stereotype that good-looking people were stupid, but that wasn’t your problem.

Another week, and filming as set to wrap up – so for now, you continued to ignore Johnny’s thinly-veiled innuendos, and barely-veiled-at-all propositions, and headed over to where Colt was waiting by his truck to see if he wanted to grab dinner at a jungle-themed restaurant you’d seen on Instagram.

“You sure you wouldn’t rather go with Johnny?” he muttered, frowning over your shoulder (presumably at the mouth actor).

You, however, were frowning at him: “God, no. Why would I want to go anywhere with him?”

“You two seem to be friendly, is all.” Colt shrugged, finally looking at you…although he wouldn’t meet your eyes.

“I wouldn’t use the word friendly.” you responded tartly: “Maybe long-suffering on my part, and really annoying when it came to him.”

Colt looked confused: “You’re not into him?”

“No!” you exclaimed, probably too loudly but you needed to make it clear you were not ‘into’ Johnny: “I’m just trying to stay professional while he…does his best to be as gross as possible before I can call it harassment.”

Colt’s shoulders slumped, and after a moment of confusion you realised he looked relieved.

You didn’t get it – surely people didn’t actually think you were reciprocating Johnny’s horndog behaviour. You might not be able to publicly tell him to wind his neck in…but you felt like it was definite subject to your non-responses!

Suddenly concerned people might think you were into Johnny, you turned to storm off and do…literally anything to make it clear to God and everyone that you thought the man was a jerkoff, when a big hand wrapped around your wrist, and yanked you back towards a solid chest.

“Colt, what on earth - !”

You were cut off by Colt spinning you round and pulling you into a bone-crushing hug.

It should have been uncomfortable, but you actually found it…really nice. Colt’s arms were strong around your waist, pressing you close to his warm chest, even lifting you off of your feet a little. It was so easy to melt into his embrace, that familiar feeling of safety leeching the tension out of you, until you almost forgot why you had been about to storm off.

“I thought you were just waiting for filming to wrap up before accepting one of his offers.” Colt murmured into your hair.

“His many, many annoying offers.” you muttered bitterly, before Colt’s words actually sunk in: “But, wait, why would it matter if I was into Johnny?”

You felt Colt swallow, his voice nervous when he answered: “Because if you were into him, then you weren’t going to settle for me.”

“Settle?” you replied indignantly: “Colt Seavers, any woman would be lucky to have you! You’re an amazing guy, and don’t you ever settle for someone you think think that they’re settling for you.”

Colt was uncharacteristically serious when he spoke, his face solemn when he pulled back to look at you: “Even you?”

“Me?” you squeaked.

“Yeah. I was gonna wait until filming was finished, I know you want everyone to see how professional you are, but…I really don’t want to miss my chance. Do you want to go out for dinner tonight? As…as more than friends?”

You didn’t even need to think about it – you grinned up at Colt, happiness bursting through you: “I know the perfect place.”

#colt seavers fanfiction#colt seavers fanfic#colt seavers x reader#the fall guy fanfiction#the fall guy fanfic

63 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'll probably have more to say about this later bc I'm going to sleep soon, but I feel like, you, oliveroctavius, me, and a few other people are like the small minority I've seen anywhere who actually criticize TASM for the eugenics and ableism, and it honestly floors me that no one talks about it when it's so blatant and tumblr loves bringing up disability and ableism otherwise? Like, it's not even a case of how everyone has valid differing opinions and needs/wants when it comes to how the vast range of disabled experiences should be approached in fiction and there's nuance in how to do even tricky, but real experiences like grief and loss - we're talking about a film series where an antagonist meant to be sympathetic makes a speech about disability being a weakness of humanity that must be genetically eradicated to strengthen it (which is never deconstructed or challenged) and has no other characterization beyond sad amputee whose only interest for a decade is his missing arm, and where Peter is some kind of genetic chosen one whose Good Genes give him cool powers, and the whole mess with Harry.

The few other times on tumblr I've seen it brought up is to like, woobify (internalized) ableism even though the films go way beyond realistic personal struggle and straight into eugenics, and as someone with a Lizard niche in the Spidey fandom, I'm floored at how everywhere else, I keep seeing the TASM version of the character topping best adaptation discussions by a huge margin compared to way better takes with zero references of the ableism (this was not the case even a few years ago, idk what happened), and you can correct me on this if I'm wrong bc you would know more about the Harry side of things than me, but I feel like TASM!Harry used to be very popular and be moved, at least until MSM2017 and Insomniac came along.

Hi sorry my brother just graduated college. Anyways, in regards to the Harry side of things, I think a lot of the ableism SHOULD be pretty obvious, but apparently it’s not considering how little critical thought there is with all these villains. There’s the good genes bad genes eugenics of Harry wanting Peter’s blood to cure himself and then it doesn’t work because the spider only worked with Peter’s “good genes” (I don’t care about their in canon excuse, it still buys into this trope) and it reacted so badly with the TERMINALLY ILL CHARACTERS “bad genes” that he turned crazy and evil. And that’s ignoring my general distaste for disability or “insanity” being used primarily as a source of fear for the good, noble, and of course able bodied protagonists.

Something that’s also pretty weird that nobody mentions is the fact that like, Electro in these movies just HAD to talk to nothing. Normally it wouldn’t bother me as much or I might be willing to give it a pass, but it’s these movies, which just love to make their disdain for disabled people clear, so it comes off as super bad taste.

Like… I’m only scratching the surface. Why are there three people who consistently point out how ableist these movies are? Especially when as you said, tasm Harry is pretty popular! Ignoring my beef with him as a Harry Osborn, it’s so odd to me because so much of that is either like, sort of romanticizing his chronic illness and breakdown or getting off on that ableist insanity I mentioned earlier.

And when you bring it up, people get SUPER defensive. I don’t know if like, the amount of invalid criticism just makes people defensive or if it makes people think there’s NO valid criticism but like… these movies aren’t bad for the reasons you think. The issues they have are like… the writing saying that eugenics is cool and fun alongside generally iffy writing.

#I’m gonna tag#tasm ableism talk#for filtering#harryposting#harry osborn#peter parker#curt connors#max dillon#spider man#spiderman#tasm#tasm2#the amazing spider man#the amazing spider man 2

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

I watched this movie just out of curiosity and it's surprising how similar these two are

"Paws of Fury" Released in 2022 and lasting 85 minutes, it is an animated film that tells the story of Hank, a dog who infiltrated a country where dogs are prohibited only to become a samurai. It is a comedy story, there are clichés and at first it does not seem to be a movie beyond seeing it once with the family and that's it, but the thing is that this movie also makes fun of these same clichés, uses absurd humor and breaks the fourth wall often

However, the similarity between Hank and Yuichi stood out to me.

Environment:

Hank is a dog, in a country of cats, where dogs are prohibited and hated, so the difference between the protagonist and his environment becomes clear from the first seconds of the film. Hank wants to become a samurai, going to cat country almost knowing that he probably won't get much help just because he's a dog, and he is even arrested when he tries to enter the country illegally by the Shogun.

Hank doesn't fit into his environment

Yuichi, a rabbit who grew up on a farm, as far as we know, for most of his life, and when he decides to leave the nest, he goes to a city to become a great samurai, a farmer in a big city. Although the difference in this case is not so visible, it is there, Yuichi tries to fit in, talk to the people of the city, and this ended up being ignored by the residents themselves, and this is highlighted when he tries to help Gen, it is noticeable that when at first it didn't fit

Yuichi didn't fit into his environment

Reasons:

They both wanted to be Samurais, and they went far from home and comfort to achieve their goals, and they both have an idol that encouraged them to do this.

Yuichi has his ancestor, Miyamoto Usagi, thanks to the stories he read about him and his adventures, he had the idea of being a samurai just like him.

Hank has Jimbo, The samurai who had saved his life as a child, he never knew who that samurai who saved him was, but he did want to be equal to him and that is why he went to a world where that was impossible for him.

Development:

There is no equity here, it is obvious that the character that has the most development is Yuichi, and that is because Samurai Rabbit is a two-season series where his development can be explored adequately, but with Hank it is not the same, because it is a film that lasts exactly 85 minutes without counting the credits (There is a joke about this in the film in fact)

And although Hank's movie is the typical cliché of the hero's journey, there is still a development, no matter how minimal

Yuichi and Hank were selfish, believing that they could do anything and that they deserved the credit, believing that they were invincible to anyone. This is seen in the part when Hank claims to have defeated Sumo, although it was not really him, his arrogance reached such a point that on his pedestal he forgot and neglected something important, his honor and the village.

The village was attacked, and Hank was not there to defend it, this causes a relapse in the hero's journey.

Although Yuichi may have been arrogant, it is not the same type of arrogance, Yuichi believed that he did not even need a sensei, that what he had already learned on the farm was enough. In the first season, and even more so in the first chapters, Yuichi refuses to look for a sensei to train him properly (Unlike Hank, who looked for one from the beginning) It is when Yuichi makes a mistake that he begins to look for a sensei.

Sensei:

There are many differences between Jimbo and Karasu-Tengu

Jimbo is an overweight cat who laments between catnip and sake, remembering those days when he was a great samurai. Karasu-Tengu is a powerful and intimidating Yokai warrior.

But a similarity that I saw in the two of them is their distrust. Neither of them immediately agreed to train their disciple, they themselves earned the honor of being accepted by their teachers.

Part 2!

#save rottmnt#yuichi usagi#rise usagi#rottmnt#samurai rabbit#the usagi chronicles#rottmnt usagi#usagi chronicles#samurai rabbit usagi chronicles#paws of fury

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

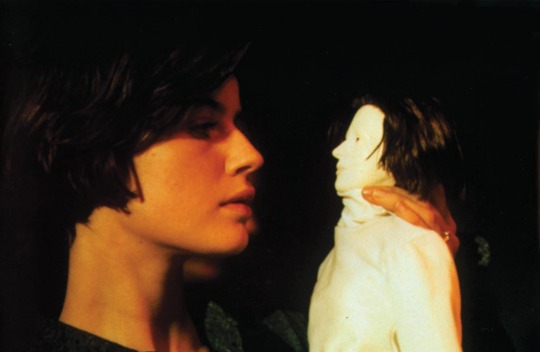

7 Takes on The Double Life of Veronique

You know the thing where you like the same thing as a terrible person?

I guess even Lear-esque cringey edgelords like great movies and Keith McNally is not wrong about Sexy Beast and definitely definitely not wrong about the Double Life of Veronique, a movie I've now seen 3x, 2 of which ended in helpless tears (the only way I know if something is art).

This movie was a selection by McNally at a Roxy Cinema mini-festival in October 2023. As I told the crew who I invited (tricked?) to see the movie: now it's your turn to think about it for 15 years!

I love the moment after the movie when people are asking helplessly -- but what does the movie mean?!? And I really, really love the moment when people get angry at the end of the movie. These are real emotions! What's the last time a movie made you think anything other than "god, that was 45 minutes too long?" (The Double Life of Veronique is under 100 minutes! yessss)

[I didn't hear it cause I was, like, weeping, but my friend said at the end a guy behind us was angrily griping that the movie was too slow? Huh? Stuff is literally happening every moment of the movie? There is not a single wasted scene, line or frame? What even are these senses whose proofs we can so liberally ignore?]

Since it might be another 15 years until I see it again and I don't have the benefit of just having written a college thesis that was mostly about Lacan via Zizek, I thought I would type out a few thought exercises/interpretative frameworks that I think apply to this movie:

The contingent nature of the universe/the senselessness of existense -- probably the easiest to justify, especially in the context of Kieslowski's complete ouevre, in consideration of his personal history, based on the interviews he's given, etc...

What to do about emotional apocrypha — what do you do with and about feelings that seem to come from nowhere? Feelings are "real" and we know now (i.e. the science is now there to tell us, eg Lisa Feldman Barrets's fascinating work) they're not in any way subservient in value or usefulness to "reason"; like if anything the opposite, emotions are the "why" and reason is the very patched together and incomplete "how" behind what we are and what we do. Worth thinking about why it is Kieslowski's most compelling films have female protagonists given the historical association to the binary genders for emotion vs reason.

The duality and dichotomy of post-war East/West Europe -- I think this one is sorta obvious but not less resonant? There's a good article out there about how the film predicted a lot of the consequences of the EU. Elsewhere I've read that Polish critics pilloried Kieslowski for a traitor to his kind over this theme, which reminded me of the story about how Bach's works were sometimes not well received by the church patrons who got to hear a lot of it first because they thought it was too dour -- imagine you have the greatest musician who will ever live as your church musician and your biggest peeve is his music isn't fun enough for Sunday. In any event this is a major theme in Three Colors, and I'm sure there's no accident that this movie and the Trilogy are connected by the same fake composer (key work = "Song for the Unification of Europe"...)

Return to theory in film (Zizek) -- he wrote a whole book about it. I'm not sure I agree Kieslowski's films make the case for the return to Theory (ie I think you can interpret his movies without it.) But the fact that you can so unbelievably seamlessly integrate his films to a Lacanian framework gives me that feeling of the inevitability of Lacan.

Art Cinema's enduring interest in interrogating the limits of its medium -- which of course is also present in art literature for its own medium, and frequently not only present but foregrounded in theatre. The Puppetmaster is a clear analogue to the filmmaker (and of God, lmao...they can't help themselves), but also all the unbelievably uncomfortable sex scenes in this movie are a masterclass on the male gaze and how you constitute and undermine it...etc.

Space-time Travel (Zizek) -- right away, I'm going to say I don't think this one is all that interesting, but it's what Criterion chose to accompany the 15th year re-release of the movie. So...ok 🤷🏽♀️ I'd say that listening to physics podcasts has convinced me of the value of a literary education (those hermeneutical skills come in so handy), so I see the relevance of thinking of these two together, but I also feel like the fake math is the part of Lacan I always found a little too silly to stand.

The agony of art as vocation -- I'm sorta lazily splitting this out from #5 just because when I originally wrote this post I had 7 points and now I can only remember 6 of them, and I like the resonance of 7....There's a Badiou-esque invocation of the four types of truth procedures at work in this movie that could easily fill the pages of another unread senior thesis: science -- the zizek time travel thing, the way the movie is, actually, concerned with the explanation of what is happening and why, rather than just accepting as a premise that there can be doubles in the world; politics -- the scene where Weronika meets Veronique is at a political rally, the east/west thing mentioned above, etc; art and love, obviously.... But the key to the "plot" of Veronique's life is "Does she keep singing, even if it kills her?"

Random closing thoughts:

I'm still thinking about and cannot resolve the mystery of the subplot about Veronique testifying in her friend's divorce(?) trial. What does it mean?

One thing that always bothered me about Kieslowski is a feeling i have that his movies are slightly (high key???) exploitative of his actresses, which seems like shabby repayment for their taking considerable artistic risks. Maybe I'm just getting this feeling from applying Lacan and Zizek to his movies though (that's two dudes who definitely don't understand about women...). I'd like to think I'm wrong about this, his masterworks are all with women and "about" women. I don't think he doesn't get this, though, see again the Puppetmaster (surely one of the creepiest dudes to ever grace an art film and that's saying a lot).

#the double life of veronique#krzysztof kieslowski#kieslowski#film#movies#irene jacob#puppetmaster#zizek#lacan

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

was going to wait to pirate brave new world but my dad bought tickets so ive watched it

spoilers obviously and also i was kinda disappointed so if you don’t want to read some negativity just ignore

- what happened to getting rid of the isreali superhero??

- if they weren’t gonna do it because of the genocide they could at least have done it for the monetary incentive once it became clear she was what i can only describe as a non-character

- i know i can talk as an antonia-dreykov-taskmaster stan but a) she wasn’t put there for a weird attempt at propaganda, b) she was mind-controlled for most of that movie, and c) she had an effect on the plot

- like in brave new world i felt like i was hallucinating the character half the time she just followed them around and disappeared at random points throughout. they made a joke about her being grumpy at the end and i was like wow this is news to me

- speaking of propaganda though i feel like the best way to describe the plot is if you wanted to use the whole “corruption in the government and military” thing in past captain america films but you had to make the government and military come off as the good guys actually

- they did the same thing with sam’s character. that right there is sam wilson if sam wilson had a chip in his brain that would explode if he ever thought the words “maybe the system itself is flawed”

- i hated the way they tried to humanise ross with the relationship with his daughter like dude it’s not like you weren’t there for her emotionally you didn’t just make a couple mistakes in your career you chased the hulk through harlem. you tried to pass the sokovia accords!!

- the fact that they did the whole enemy-within thing but it was just one guy with a grudge mind-controlling people

- and i know this is a marvel film! i wasn’t walking in expecting to see anarchist cinema!! but there’s stuff they were trying to do that other marvel stuff did really well before!

- like how criticising the government is a staple of captain america films and of sam wilson himself

- the mind control worked in the winter soldier because we were watching a character we and the protagonist cared deeply about be tortured and forced into something he wasn’t

- the mind control worked in black widow because we were watching characters deal with the aftermath of having their free will violently stripped away in an allegory to the ways vulnerable people in real life have their autonomy taken from them

- the mind control in brave new world was just “oh no, soldier #378 just got mind controlled. how inconvenient”

- i love love loved sam’s relationship with joaquin and that discussion with bucky. so naturally the character relationships were given minimal priority

- am i remembering wrong or did they fight separately way too much? like they’re a team! they’re best buds! why are they splitting this big group of enemies into two to stand on opposite sides of the room fighting alone?

- joaquin as a whole was awesome actually i want to see more of him and sam being besties as soon as sam gets that brain chip taken out

- this one’s tiny and stupid but that bit at the end where sam’s talking and the camera’s looking down at him from like a 45 degree angle but the pavement isn’t greenscreened in right so it looks like he’s standing knee-deep in a hole dug into a steep hill made me way too mad

- i saw someone saying they cut eli bradley out which was a horrible idea cause he deserved to be there and would have made the film better and it felt kinda weird that he was never brought up with isaiah being imprisoned

- speaking of isaiah i feel like there should have been way more attention to the effects this whole thing had on him cause the poor guy’s going through a lot and the movie just doesn’t seem as interested in him as it wants to be

- i did find it fun that japan was the ‘rich country from The Eastern Half of the Planet that american audiences are reliably familiar with that will probably not start or escalate a real-life conflict by being shown to disagree with the us’ for this film

- someone in the credits had the last name goncharov and i got jumpscared

- a woman in the row in front of me was knitting throughout the whole thing which i thought looked pretty fun

- i got to talk to my dad about the fantastic 4 and thunderbolts trailers from before it on the way back home although i am a little worried about thunderbolts now

- it may have been a technically very good film, idk how films are crafted and these thoughts are all just my opinions

#captain america brave new world#cabnw spoilers#cabnw hate#<- i would not consider this hate but its mainly negative and i feel like anyone who’s blocked the hate tag would also not want to see this

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frankenstein films; Curse of (1957), Revenge of (‘58), Evil of (‘64), Must Be Destroyed (‘69), and the Monster From Hell (‘74)

A doctor makes several attempts to create life by sewing together parts of the dead.

It was good that across several films the studio used the same actor to portray the main character (which is the doctor, not the creature). It’s useful both to connect various installments of the franchise over time but also because Peter Cushing is a good actor and suits the role as he has an educated bearing but clearly enjoys the sinister side of the story.

Each movie is essentially the same narrative with the minor details changed. There are even obvious references to the previous ones, such as Patrick Troughton digging up graves, or at times whole arcs repeated such as a young admirer studying under Frankenstein to assist his work only to be eventually disgusted by the realities of it.

Easily the best version of the creature was Christopher Lee, although it still felt like a bit of a waste as there was little acting he could do in the role. The subtext gets a little better over time as medical ethics is explored or the lore of the science involved and in one religion is a prominent feature but still handled with superstitious context.

The fact that Frankenstein is consistently portrayed as the bad guy in these films but gets the most screen time and then the monster still always steals the show really doesn’t help the misconception that the title character is the creature. There needed to be more clear protagonists because theviolence is almost always resolved by more violence from ignorant people who we shouldn’t route for.

The Curse of Frankenstein: 4/10 -It’s below average, but only just!-

The Revenge of Frankenstein: 4/10 -It’s below average, but only just!-

The Evil of Frankenstein: 4/10 -It’s below average, but only just!-

Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed: 3/10 -This one’s bad but it’s got some good in it, just there-

Frankenstein and the Monster From Hell: 3/10 -This one’s bad but it’s got some good in it, just there-

-The first of these installments held the distinction of the most profitable movie from a British studio, produced in England, for years.

-Troughton originally had a role in Curse but it was cut from the final film.

-Monster from Hell was the last Hammer film sequel until The Woman in Black 2 (2014).

#Film#Review#The Curse of Frankenstein#The Revenge of Frankenstein#The Evil of Frankenstein#Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed#Frankenstein and the Monster From Hell#1957#1958#1964#1969#1974#Science Fiction#Sci Fi#Peter Cushing#Patrick Troughton#Christopher Lee#JasonSutekh#Frankenstein

0 notes

Text

Yep. They want to be the next Game of Thrones, and what they took away from that was contrarian and subversive attitudes toward epic fantasy, plus Shocking Deaths equals smash success and becoming a water cooler topic and a household name. Never mind that Game of Thrones was successful not for the subversion, but because it was closely adhering to a book series that was deconstructing not subverting epic fantasy, while also utilizing the tropes and conventions in new ways, which is basically depending on them, not undermining them. GRRM was saying "there are heroes and villains, and there are worthwhile aspects to chivalry and rulers, but it's not automatic or easy and they are not always what you think". GRRM was saying "look at how awesome, how epic, how grand and beautiful medieval fantasy can be, just don't lose track of the dark sides" GRRM was saying "this is what makes a great hero, this is what makes a lost prince a wonderful story, this is what makes a true knight, a great king, an worthy lord. Being good isn't simple, it isn't a recipe for prosperity and glory, but it's worth doing." D&D were saying "LOL, heroes? Villains? Don't be a child. Everything you love is stupid, we're going to show you why." D&D were saying "We're realistic, look at how dark, grimy, dingy and poverty-riddled pre-modern times were! Also, not being as advanced as us, everyone running around in such settings is a complete bastard, except the characters we want you to like." D&D were saying "Being good is pointless, it's better to win! There is no point to being a good knight, lord or ruler because the ruthless SOB will just kill them and their people. A fighter or leader should be ruthless and smart! Being smart means... um, what was the question? Can we go make Star Wars now?"

Judkins and company looked at GoT's approach, ignored the way it turned out, assuming (as D&D did wrt the heroes of aSoI&F) that they were smart enough to evade the pitfalls and write a better finish, and completely neglected the fact that GoT would never have got off the ground without the vastly superior success, against greater odds, with longer-lasting credibility of the three (and only three) films of LotR, spiritually and thematically faithful to the original work, even if just as flawed in some of their execution efforts as Benioff, Weiss and Judkins, and not remotely making any attempt to subvert anything for more than an occasional momentary in-joke. Peter Jackson took a book series even older, more "outdated" and lacking in feminist themes or fashionable racial/sexual politics, did his best to bring the original author's vision to the screen, and won over the critics, the audiences, the industry and much of the original's fandom, especially considering the amount of cut or altered material.

Wheel of Time, like aSoI&F, pays homage to Tolkien, and is a deconstructive series built on love of, and appreciation for, the genre, that stands out from the legion of imitators and successors of Tolkien (and Howard, White, Lewis, Wells, LeGuin & Leiber, among others), by taking well-known or loved concepts and exploring them in new and different ways. Like Tolkien & Martin, WoT contrasts absolute Evil with abnormally virtuous protagonists, but also makes it clear how virtue is earned, rather than asserted. It shows how the epic heroes rely on the little guy and the everyman to succeed, that the Champion cannot win the day without the man on the street in his corner or at his side. They marry fairy tales written to instruct children, to historical epics describing how our own civilization formed, and explore the origins of mythology in purporting to write a forgotten history of our own world. The success of LotR and the good bits of GoT were very, very possible to duplicate with WoT as the foundational source.

Judkins had two adaptational paths laid out before him, the path of Jackson embracing Tolkien, and the cautionary tale of Benioff & Weiss gradually moving away from Martin. Judkins choose to double down on the failure, by jettisoning Jordan from the outset, ignoring LotR films 1-3, skipping GoT seasons 1&2 and leaping headfirst into 5, 7 & 8.

These people write character deaths as they do, because they don't understand character at all. Their cast of characters is a fungible set of plot mechanisms. Anything a character "needs" to do is an interchangeable plot point that can placed anywhere in the story, as long as it occurs chronologically before other events that rely on it. Anything one character does can be done just as well by another. Any achievement, accomplishment or coolness-enhancing moment is a transferable object or title that they can attach to their favorites characters instead of the one in the book. They can kill off Siuan, because they look down a checklist of plot points in which she is involved, and decide they can have someone else do it (Moiraine or Alanna can get the rebellion started!), or that they can do without Siuan's participation (Egwene can do just fine without anyone's help!), or they don't really care about reproducing that plot point (who cares about Nynaeve Healing Siuan? Egwene or Moiraine can Heal Logain and there will be no difference, really).

Other deaths that illustrate this principle by killing the character in an approximately similar time and place, but strip the death of all meaning, include

Ingtar (zero arc, zero connection to Rand or the MC who replaced Rand in most scenes with him, zero meaning in his death)

Melindhra (Mat who? Their girlpower obsession decided that a woman failing to overcome Mat's thoroughly established luck and quick reflexes was an inferior display of agency to a woman deciding not to kill Lan because of the unsupported-in-the-script choice between her conflicting loyalties)

Ishamael (What, exactly, was he trying to do, and why, in any given scene? How did any of that add up to an explanation of his fight against the "combined" efforts of the Emond's Fielders [sans Nynaeve, of course]? How does paying lip service to his revealed motivations from the later books inform his actions or his death?)

Natti Cauthon (did they expect us to care about the worst thing that happened to Mat, arguably including the Shadar Logoth dagger? Do they realize that a case can be made that Mat's objective inferiority in personal character and quality are the result of Natti's awful parenting?)

Ispan Shefar (Moghedian is now simply a deranged lunatic acting at random, who inexplicably does not kill any of the significant recurring characters)

Dana the Dumpy Darkfriend (the writers think swords are guns and two fit and healthy young men need to run in terror from a visibly unathletic woman holding one; also, the only on-screen Darkfriend to that point in the show is now dead, and not super-competent or on-mission, so they probably are not a problem)

Steppin the Tragic Warder (a Warder losing his Aes Sedai is a Big Deal, just wait to see what Lan has to go through next season ... oh wait, never mind. Also, in his shoes, his options were nonconsensual gay sex or death, and he made his choice)

Kerene (this has created a dangerous and fraught situation, forcing Liandrin to take extreme measures to subdue her killer and prevent the now-untenable program of holding him captive from failing with more tragic results ... until the next episode when we forget that the strongest sister in the party had been killed when they were already having trouble with him, and Liandrin can't defend her actions in response as a response)

Narg (Narg smart. Narg not go down like bitch, turning back on armed opponent)

Marin al'Vere (are we not going to discuss the con artist using her name who has somehow eliminated all the parents & mentors of the main characters and taken over the village in their absence?)

So I haven’t really said anything about Suian’s death. It seems to be very controversial right now but I’ll give my very luke warm two cents which is- I didn’t like it but I also wasn’t surprised by it.

The show has made it Very clear that they use character death for shock value and shock value alone without much forethought of how it’ll impact that plot going forward.

-the wife they invented for Perrin just to fridge her

-Uno

-Ihvon

-Loial

-Sammael

-and now Suian

Look, I think the show does many things well, i will praise the actors and actresses to death, but the show is very very bad at character death. They also do have a horrible shock value habit, I find irritating. Stand outs include setting up Rand’s sword fight with Turak only to unceremoniously and quickly kill him to undercut the moment knowing many book readers anticipated the fight. It shows a lack of commitment to their own story in a lot of ways.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've decided I'm not going to derail a post I ultimately agree with but the fucking level of frustration I feel at a cis person watching a Shrek movie and seeing transmisogynistic jokes - all but ONE of examples they list being from villains which exist in the story to help bolster its fucking themes - and deciding that it makes the movie harmful for kids to watch (and a bunch of idiots in the notes actually claiming that we, in fact, need to throw the whole thing away) makes me fucking insane. The theme of the movie is that society is broken and that it's wrong to judge or mistreat people based on aspects of themselves they cannot control. A good fucking number of DWA movies have that theme, actually. And yeah it's shitty that sometimes a poor-taste joke comes from the protagonists, there is no idealogically pure media out there and I'm not here to argue that, but it's pretty damn clear that there's intentions behind making villains act a certain way especially when the moral of the story is taken into consideration. It becomes willful ignorance being employed to fight on the behalf of a group you're not a part of (that's called talking over us, hon.)

Not to mention the reblog that was like "oh no, now we have to teach kids about the ills of the world and they won't get it", like how laughably fucking privileged. Nope. Some kids learn about the ills of the world from the world itself and not the media they consume. I can totally empathize with how shitty it is to have to explain that a show your kid likes did a really horrible thing and we shouldn't emulate that, but like. Fuck. Films like Shrek exist for the kids who have already been told off and/or dismissed by the world, and they'll actually benefit from seeing them, seeing themselves as good guys, seeing a narrative that goes against their oppressors. Like, Shrek 2 in particular sees the protagonist do everything he can to be palatable for his in-laws and it still isn't good enough. What an important fucking note for someone who's still figuring out respectability politics.

Sometimes a thing that can be harmful in one way can actually be beneficial in another way, who fucking knew??

But also lol at anyone who actually thought that the insane ramblings of the Fairy Godmother and Prince Charming were meant to be considered respectable by the narrative. Holy shit. A child would not make that mistake and yet that's the point of your post.

#Rant#Vent#I was honestly not going to say anything and then I saw that OP was cis and lost my mind#It's one thing to have strong feelings about how you personally were affected by a piece of media#And people should respect your perspective even in the context of it being biased because the matter is#Of course a completely personal one#BUT LIKE LITERALLY READING A FILM FOR FILTH LIKE IN THE MOST BAD FAITH WAY POSSIBLE#AS LIKE SOMEONE WHO CAN'T BE AFFECTED IN SUCH A WAY BY THESE ASPECTS#like way to treat our lived experiences as nothing more than an academic-type argument#Not to play oppression olympics but like as an overweight trans neurodiv person of color#Films like this are fucking important to me and a big reason as to why I want to tell stories#I see myself in these protags in so many different ways like holy fuck#Sorry all you see is a chance to get outrage points on tumblr dot com the rest of your post was good tho#Because yes there absolutely is a point to be made about bad rep and how much it's pushed#Over this bullshit guise of non politicism#But pairing it with your idiotic bad faith takes ain't something I can get behind. You feel?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

To Be Tamed or Not To Be Tamed?

That is the question.

"Masculine and feminine roles are not biologically fixed but socially constructed."

In the 90s and early 2000s, Hollywood offered a counteract to the previous oppression of women and girls in cinema through the emergence of teen literary adaptations of classic novels and plays. These adaptations dismantled what audiences expected of a classic novel or Shakespearean film. Two films I believe stand out are: 10 Things I Hate About You and She’s The Man. 10 Things I Hate About You is an adaptation of one of Shakespeare’s earliest plays “Taming of the Screw” concerned with gender roles and the institution of marriage and She’s The Man follows the narrative of his tragic-comedy “Twelfth Night”, that incorporates androgyny, sexual ambiguity and gender confusion.

10 Things I Hate About You follows the story of two polarising sisters Kat and Bianca Stratford. Kat performs the role of the “shrew” - non-conformist, not afraid to express her opinions (which are compared to “acts of terrorism”), and independent. Whereas Bianca conforms to traditional gender roles this is displayed through the mise-en-scene: her room has lots of accents of pink and flowers, decorated with stuffed animals and dolls creating a certain archetype. Her interests also lie hegemonically in line with her gender - fashion, boys and dating - which are considered mainstream ideals of becoming popular in high school. Bianca is a clear example of the ideals of the Beauty Myth - blonde, slender, and daintily featured - and as a result, she is loved for adhering to its demands. Their father Walter Stratford acts as a vehicle for the concept that things are learnt through different environments, and parents have a distinct influence on gender and how people discover their identity. He does this by developing a rule that Bianca can only date if Kat does too - functioning as a symbol of patriarchal power and influence. 10 things offers a different kind of teen rom-com heroine: Kat’s punk, individualistic outlook, sarcastic tone, will to speak her mind, and sheer fearlessness in challenging the structures around her, embodies the spirit of third-wave feminism of the mid-90s. By making Kat and not the amiable Bianca the main protagonist, the story makes the feminist “shrew” aspirational - who lays the groundwork for other alternative and progressive women and girls paving the way for a generation of feminists.

Similarly, She’s the Man also shows gender can be “performed” in overt ways. The film belittles teen girls and their interests - Viola is shown to be at the mercy of her sexist football coach who believes that “Girls aren’t as fast as boys. It's not me talking, it’s a scientific fact,". This slur of misogyny spurs Viola to pose as her brother Sebastian to prove her worth and talent as a footballer. The film goes further in destabilising gender expectations and subverting gender stereotypes: the women are portrayed as being confident, playing sports and getting into physical fights whereas the men are seen crying, writing poetic song lyrics and screaming at the sight of spiders. By having the characters display behaviours which are contradictory to what is expected of them, the film highlights the arbitrary nature of gender roles and stereotypes. The film also shows how gender roles and expectations are prescribed - through Viola’s engagement with femininity - like 10 things Viola’s mother plays a role in highlighting her desire for her daughter’s conformity to feminine ideals (socialisation of women to be demure and “lady-like”).

Whilst both films subvert previous representations of women: there are still problems within them. Kat’s initial feminism can be rooted in the second wave of feminism where the movement largely ignored women of colour and queer women, focusing on advancing the rights of affluent caucasian women: of which Kat is representative of. This is echoes Bell Hook's idea of intersectionality where it is recognised that social classifications (race, gender, sexual identity, class) are interconnected and that ignoring their intersection created oppression towards women and change the experience of living as a woman in society.

Some critics have interpreted 10 things ending to be Kat subduing to her feminism by settling into a relationship with Patrick and conforming to the social norms of high school. However I think that the ending can be seen in a positive light: Kat is practising third-wave feminism, by marrying her political beliefs to freedom of choice, showing a sign of her growth. Bianca is also shown progressively: by choosing the less popular man for the one who truly cares and will make her happy as well as punching Joey in the face for the objectification of her and Kat. Kat learns to accept the affections of a man who respects her while retaining her beliefs and feminism. She’s the Man introduced a much more fluid concept of gender to a younger audience than was in the current mainstream. It helped unconsciously create a space for transgressive sexualities and gender identities when neither were represented in the mainstream as well as disseminating these concepts into younger audiences eyeline for them to ascribe their own meanings and interpretations. Both films effectively explore the themes of feminism, identity and gender politics in both similar and contrasting ways serving as starting blocks for a journey to equal and progressive representation in film and media.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Favorite History Books || Grand-Guignol: The French Theatre of Horror by Michael Wilson and Richard J. Hand ★★★★☆

The phrase ‘grand-guignol’ has entered the language as a general term for the display of grotesque violence within performance media, but it originates in a specific theatre down an obscure alley in Paris. The Grand-Guignol was a remarkable theatre. For more than six decades it thrilled its audiences with a peculiar blend of horrific violence, the erotic and fast-paced comedy. In its time it achieved international notoriety and became one of the most successful tourist attractions in the French capital.

It is, therefore, all the more extraordinary that, both in its lifetime and since its demise, the Grand-Guignol has been virtually ignored by academics and today has the status of one of the world’s great forgotten theatres. It is not difficult to lay the blame for this neglect at the door of institutional conservatism and general disdain in the past for the serious study of popular theatre in academic circles. For many years the Grand-Guignol was simply deemed unworthy of serious consideration and the very recipe for its success with the public was sufficient to secure its dismissal by theatre historians. It is, therefore, to be welcomed that recent years have witnessed a growing interest in popular culture; the horror genre, in its many forms, has now entered the arena of scholarly debate. This book has been prepared in that context and, partly at least, in response to the lack of material available on the Grand-Guignol, particularly to the English-speaking reader.

The Grand-Guignol emerged at a crucial and exciting time for theatre. It was conceived in the nineteenth century, directly from the groundbreaking work of André Antoine and his fellow naturalist radicals at the Théâtre Libre. In fact, it grew up to become a child of the twentieth century, emerging as a complex and seemingly contradictory mixture of theatrical traditions and genres characterized by its use of both horror and comedy plays, incorporating melodrama and naturalism, and going on to reflect the influence of Expressionism and film. Yet at its heart it always remained a popular theatre and, more crucially, a modern theatre. If the dawn of the twentieth century was a critical period in the development of European theatre, then the same can be said for the horror genre itself. As Paul Wells states: As the nineteenth century passed into the twentieth, this prevailing moral and ethical tension between the individual and the sociopolitical order was profoundly affected by some of the most significant shifts in social and cultural life. This effectively reconfigured the notion of evil in the horror text . . . in a way that moved beyond issues of fantasy and ideology and into the realms of material existence and an overt challenge to established cultural value systems.

The Grand-Guignol only became what it did because it emerged when it did and where it did. When talking of a ‘Theatre of Horror’ one might imagine the monster-iconography and Gothic extravaganzas (ironic or otherwise) on display in Richard O’Brien’s The Rocky Horror Show, Andrew Lloyd-Webber’s Phantom of the Opera, and even Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire. But as a realist form that never strays far from a grounding in Zola-inspired naturalism, “Grand Guignol requires sadists rather than monsters”. Although the Grand-Guignol steers well clear of all things supernatural, it pushes the human subject into monstrosity, extrapolating, as it were, la bête humaine into le monstre humain. André de Lorde sums up this aspect of the Grand-Guignol when he writes in the preface to La Galerie des monstres, ‘we have a monster within us—a potential monster’. The psychological motivation of the Grand-Guignol protagonist/antagonist—in the comedies as much as the horror plays—is dictated by primal instincts, or unpredictable mania, the plots obsessed with death, sex and insanity and exacerbated or compounded by grotesque coincidence or haunting irony.

Aside from a few books on the subject, the Grand-Guignol’s most substantial surviving legacy is the collection of scripts, housed at the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, fifty-five of which are contained in Agnès Pierron’s Le Grand-Guignol. There also exists a number of photographic stills, documentary footage, press cuttings, programme notes and eye-witness accounts. The most useful of these are the memoirs of Paula Maxa, the most celebrated Grand-Guignol actor; what she is able to tell us about performing at the rue Chaptal is invaluable, in spite of her subjectivity and desire to create her own mythology. Apart from this we have very little to tell us about the nature of performance in relation to Grand-Guignol and we are left to our own hypothesizing. To this end we have established a Grand-Guignol Laboratory at the University of Glamorgan to investigate the performative nature of the form. Using student actors, we have attempted to learn more about Grand-Guignol performance through the practical exploration of scripts and themes in the drama studio and many of the conclusions contained in this book are informed by that work. We would agree with Mel Gordon that the Grand-Guignol greatly influenced subsequent horror films, even though it was, ironically, the cinema that contributed largely to the theatre’s demise. In the Grand-Guignol Laboratory we have found films particularly beneficial as an entry point into our speculative study towards understanding performance practice at the Grand-Guignol. At the same time, it would be a grave mistake to make assumptions about the Grand-Guignol based solely on cinematic evidence. Cinema and theatre are different forms and so we have always trodden with great care in this respect. It is a difference recognized by Maxa herself when she says:

“In the cinema you have a series of images. Everything happens very quickly. But to see people in the flesh suffering and dying at the slow pace required by live performance, that is much more effective. It’s a different thing altogether.”

#historyedit#litedit#grand guignol#19th and early 20th#french history#european history#history#horror#history book#nanshe's graphics#tw: blood

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fashion Analysis (Part 2: Outside of Amatonormativity Alone)

[Note: This post is a part of a series analyzing self-expression, fashion, aromanticism, and how they interact with other parts of identity. For full context please read the whole thing!]

Outside of Amatonormativity Alone: Sexism, Homophobia (and/or Transphobia), Racism, Ableism, and Other Factors That can Impact Self Expression

My comic was originally meant to be a light hearted joke. I’d always been told I’d want to dress up one day, be pretty and feminine once I fell in love with a boy (BLEGH). I was so certain that I would never do that, and now … here we are. I put lots of effort into my appearance, present feminine, all in the hopes I’ll impress a very special someone - a potential employer at a networking event. I think there’s a certain irony to all of this, and I do find it funny that I managed to both be wrong and completely subvert amatonormative stereotypes!

But having the chance to think about the whole situation, I realize now that my changes in presentation reflect far more. The pressure I felt to dress differently are still influenced by fundamental forms of discrimination in society, and I would be remiss to not address these inherent factors that were tied with my experiences alongside my aromanticism. So in this section, I will briefly cover some of these factors and summarize how they can influence people’s self expression as a whole, before discussing my own experiences and how these factors all intersect.

Sexism

The pressure on women In This Society to uphold arbitrary norms is ever present and often harmful, and while I wish I had the time to discuss the impacts of every influence the patriarchy has on personal expression, to even try to cover a fraction of it would be impractical at best for this essay. Instead, since the original comic focuses on professionalism and presentation, this is what I will talk about here.

Beauty standards are a specific manifestation of sexism that have a deep impact on how people perceive women. It’s a complicated subject that’s also tied with factors like capitalism, white supremacy, classism, and more, but to summarize the main sentiment: Women are expected to be beautiful. Or at least, conform to the expectations of “feminine” “beauty” as ascribed by the culture at large.

They also tend to be considered exclusively as this idea that "women need to be beautiful to secure their romantic prospects, which subsequently determines their worth as human beings. The problematic implications of this sentiment have been called out time and time again (and rightfully so), however there is an often overlooked second problematic element to beauty standards, as stated in the quote below:

“Beauty standards are the individual qualifications women are expected to meet in order to embody the “feminine beauty ideal” and thus, succeed personally and professionally”

- Jessica DeFino. (Source 1)

… To succeed personally, and professionally.

The “Ugly Duckling Transformation” by Mina Le (Source 2) is a great video essay that covers the topic of conforming to beauty standards through the common “glow up” trope present in many (female focused) films from the early 2000s.

“In most of these movies, the [main character] is a nice person, but is bullied or ignored because of her looks.”

Mina Le, (timestamp 4:02-4:06)

Generally, by whatever plot device necessary, the ugly duckling will adopt a new “improved” presentation that includes makeup, a new haircut, and a new wardrobe. While it is not inherently problematic for a woman to be shown changing to embrace more feminine traits, there are a few problems with how the outcomes of these transformations are always depicted and what they imply. For starters, this transformation is shown to be the key that grants the protagonist her wishes and gives her confidence and better treatment by her peers. What this is essentially saying is that women are also expected to follow beauty standards to be treated well in general, not only in a romantic context, and deviation from these norms leads to the consequences of being ostracized.

The other problematic element of how these transformations are portrayed are the fact that generally the ONLY kind of change that is depicted in popular media is one in the more feminine direction. Shanspeare, another video essayist on YouTube, investigates this phenomenon in more detail in “the tomboy figure, gender expression, and the media that portrays them” (Source 4). In this video, Shaniya explains that “tomboy” characters are only ever portrayed as children - which doesn’t make any sense at face value, considering that there ARE plenty of masculine adult women in real life. But through the course of the video (and I would highly recommend giving it a watch! It is very good), it becomes evident that the “maturity” aspect of coming of age movies inherently tie the idea of growth with “learning” to become more feminine. Because of the prevalence of these storylines (as few mainstream plots will celebrate a woman becoming more masculine and embracing gender nonconformity) it becomes clear that femininity is fundamentally associated with maturity. It also implies that masculinity in women is not only not preferred, it is unacceptable to be considered mature. Both of these sentiments are ones that should be questioned, too.

Overall, I think it is clear that these physical presentation expectations, even if not as restrictive as historical dress codes for women have been, are still inherently sexist (not to mention harmful by also influencing people to have poor self image and subsequent mental health disorders). Nobody should have to dress in conformity with gender norms to be considered “acceptable”, not only desirable, which leads us to the second part of this section.

Homophobia (and/or Transphobia)

So what happens when women don’t adhere to social expectations of femininity? (Or in general, someone chooses to present in a way that challenges the gender binary and their AGAB, but for the sake of simplicity I will discuss it from my particular lens as a cis woman who is pansexual).

There are a lot of nuances, of course, to whether it’s right that straying from femininity as a woman (or someone assumed to be a woman) will automatically get read a certain way by society. But like it or not, right or not, if you look butch many people WILL see you as either gay, (or trans-masculine, which either way is not a cishet woman). This is tied to the fact that masculinity is something historically associated with being WLW (something we will discuss later).

This association of breaking gender norms in methods of dress with being perceived as a member of the LGBTQ+ community has an influence on how people may choose to express themselves, because LGBTQ+ discrimination is very real, and it can be very dangerous in many parts of the world.

I think it’s very easy to write off claims in particular that women are pressured into dressing femininely when it is safer to do so in your area; but I really want to remind everyone that not everyone has the luxury of presenting in a gender non-conforming way. This pressure to conform does exist in many parts of the world, and can be lethal when challenged.

And even if you’re not in an extremely anti-LGBTQ+ environment/places that are considered “progressive” (like Canada), there are still numerous microagressions/non-lethal forms of discrimination that are just as widespread. According to Statistics Canada in 2019:

Close to half (47%) of students at Canadian postsecondary institutions witnessed or experienced discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity or sexual orientation (including actual or perceived gender, gender identity or sexual orientation).

(Source 3)

Fundamentally this additional pressure that exists when one chooses to deviate from gender norms is one that can not be ignored in the conversation when it comes to how people may choose to express themselves visually, and I believe the impacts that this factor has and how it interacts with the other factors discussed should be considered.

Neurodivergence (In general):

In general, beauty standards/expectations for how a “mature” adult should dress can often include clothing that creates sensory issues for many autistic people. A thread on the National Austistic Forum (Source 6) contains a discussion where different austistic people describe their struggles with formal dress codes and the discomfort of being forced to wear stiff/restrictive clothing, especially when these dress codes have no practical purpose for the work they perform. If you’re interested in learning more on this subject, the Autisticats also has a thread on how school dress codes specifically can be harmful to Autistic people (Source 7).

In addition to potentially dressing differently (which as we have already covered can be a point of contention in one’s perception and reception by society as a whole), neurodivergence is another layer of identity that tends to be infantilized. Eden from the Autsticats has detailed their experiences with this in source 5.

Both of these factors can provide a degree of influence on how people choose to express themselves and/or how they may be perceived by society, and are important facets of a diverse and thoughtful exploration of the ways self-expression can be impacted by identity.

Also, while on this topic, I just want to take a chance to highlight the fact that we should question what is considered “appropriate”, especially “professionally appropriate”, because the “traditional” definitions of these have historically been used to discriminate against minorities. Much of what gets defined as “unprofessional” or otherwise “inappropriate” has racist implications - as an example, there is a history of black hairstyles being subjected to discriminatory regulation. Other sources I have provided at the end of this document (8 and 9) list examples of these instances.

Racism (being Chinese, specifically in this case):

For this section, I won’t be going into much depth at all, because I actually have a more detailed comic on this subject lined up.

So basically, if you were not aware, East Asian (EA) people tend to be infantilized and viewed as more childish (Source 10). In particular, unless an EA woman is super outgoing and promiscuous (the “Asian Bad Girl” stereotype, see Source 10), IN MY OPINION AND EXPERIENCE it’s easy to be type casted as the other end of the spectrum: the quiet, boring nerd. On top of this too, I’ve had experiences with talking to other EA/SEA people - where they themselves would repeatedly tell me that “Asians are just less mature”, something about it being a “cultural thing” (Yeah … I don’t know either. Maybe it’s internalized racism?).

Either way, being so easily perceived as immature (considering everything discussed so far) is also tied to conformity to beauty standards and other factors such as sexism and homophobia, which I believe makes for a complex intersection of identity.

[Note from Author: For Part 3, click here!]

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another Sonic ramble

So once again I’m here with one of my rambles about my incredibly subjective view of how the Sonic series should be handled! *Beat*

...anyway.

So, one of the more recurring opinions on the fandom is that Sonic games should be written by Ian Flynn, I have talked before about the gripes I have with his writing and why I disagree with this but this post is not entirely about him, but rather a more general topic that has been bugging me for a long time.

The other day I was watching a video speculating about the upcoming Sonic Rangers, there’s not much to write home since it was pretty well made but there’s a particular part that inspired me to do this post and talk about it with other fans to discuss it.

See, at one point the video critisized the fact that Sonic Forces was written by a Japanese writer because they have to re-write the script in English and that can cause problems with localization, and that it would be better to have western writers from the get-go since Sonic’s main demographic comes from there, while making an off-hand suggestion that Ian Flynn could be a main choice. While I can see where they’re coming from, my response was a simple:

‘‘Absolutely, not’‘

See, I have a lot of issues with this to put it bluntly and I’ll try to break them down and explain them the best I can since they’re pretty subjective in nature, but I’m bringing this up because I want you guys to share your thoughts as well.

So, why does it bug me so much the idea of Sonic being handled by western creators?

In my case, the main reasons are because Sonic loses a core part of it’s appeal because of this, the fact that SEGA of Japan seems to have a better grasp of the franchise’s tone and characters and there’s the very subjective point that, in my eyes, American versions of Japanese franchises were always nothing more than dumbed down products of the source material.

To start with my first point, whenever someone talks about Sonic’s creation, a lot of people are quick to point out that our favorite blue hedgehog and his games were inspired by western pop culture and cartoons, and that is true, however oftenly they forget to mention a core thing that not only inspired, but also formed part of the core identity of this franchise.

Sonic is very inspired on anime, and at heart this franchise is a shonen.

(This image by The Great Lange expresses more clearly what I mean)

Generally, the most acknowledgement anime gets on it’s hand on Sonic is the mentions of Sonic being inspired by Dragon Ball, particularly the Super Saiyan, but there’s so much more than that, as Sonic blatantly takes inspiration from Studio Ghibli films specially in games like Sonic 3, which draws a lot of inspiration from Laputa: Castle in the Sky, this great post shows proof that this is not a coincidence.

And it doesn’t stop there, Shiro Maekawa himself has stated that SA2′s story (and in particular, the characters of Shadow and Maria) draw a lot of inspiration from the manga Please Save My Earth.

Even Sonic’s character design resembles shonen protagonists moreso than the main characters of silent cartoons, don’t believe me?

Sure, Sonic has a cartoony anatomy, no one can deny that, but he also exhibits a lot of traits from shonen characters such as spiky hair/quills (?), dynamic posing, a confident, courageous and energetic personality and most importantly, fighting spirit.

If you compare Sonic’s personality and more specifically, his abilities and moves to, say, cartoon speedy characters like the Road Runner, there’s a pretty big disconnection between him and western cartoon characters. Hell, this disconnection is even just as present if you compare him with a character like The Flash from DC.

Simply put, Sonic acts, moves and more importantly, fights like a shonen anime character. He doesn’t just go Super Saiyan and that’s it. Here’s even a quick comparison if necessary.

And this is important because this doesn’t apply just to him, but the whole franchise as a whole and when it takes a more western approach, all of these details are kinda lost or more downplayed, of course this depends on the artists and there’s YMMV at hand, but I think my point is clear.

My second point is...SoJ has consistently proven they have a much clearer grasp on how Sonic’s world and characters are compared to SoA.

Hear me out, yes, Sonic 06 and ShtH exist and yes, SoJ is not perfect by any means. But hear me out...when did the characters start to get flanderized and turned into parodies of themselves? In the 2010s...and when did SEGA move from Japanese to western writers in the games?

Of course it was more then that since there’s a whole tone shift that came with this decade and the new writers, but it’s not a coincidence that when writing in Sonic started to decay, western writers also happened to get on board with the games.

Besides that, SoA has a wide history of not getting Sonic’s tone and characters, from how they made media without much of Sonic Team’s input, to altering how characters are seen in the west. (Such as how they amped up Sonic’s attitude in their media or how the English scripts of the games featured things like Sonic seemingly barely tolerating Amy while the JP scripts portrayed this as Sonic just not understanding girls all that well instead, or for more recent examples, the addition of the ‘’torture’’ line in Forces). Not only that, but even ignoring obvious infamous writers like Ken Penders, even the ‘’best’’ writers from the western side of Sonic are still not above of giving us Pontaff-esque gems.

Like this one.

Or alternatively, I feel like sometimes western writers on Sonic rely a bit too much on their personal vision about Sonic which may or may not be a good thing, clear examples of this are Ian Flynn himself and Pontaff.

By contrast, while SoJ has it’s own share of notorious inconsistencies when dealing with writing (The 2000s era is a big offender), it seems that for them Sonic hasn’t changed much and this is visible not only on the JP scripts of the Modern games which are for the most part better than the ENG ones, but also things like the Sonic Channel comics and the recent one-shots they made with Sonic interacting with the cast show that for all intents and purposes, the Japanese’s staff vision of Sonic is much more clear and consistent compared to the west. Because of this, I’d rather have a good Japanese writer on Sonic games with the localization being focused on being faithful with the original script than have a more western writers dramatically changing the characters. (I don’t mention the tone since either way, SEGA is the one in charge of that and the writers have to follow that)