#also anti oligopoly

Text

Why did no one tell me Atlas Shrugged is a romance? It's a weird book, but the biggest surprise was the love triangle.

#atlas shrugged#classics#it hits different after business classes#but also#Francisco#is just like that and he probably knkws who John Galt is#it's just so odd#like I know it's supposed to be libertarian#and it kinda is#but its more anti communist#which makes sense for when it was written#also anti oligopoly#reardon needs a divorce

0 notes

Text

The IRS will do your taxes for you (if that's what you prefer)

This Saturday (May 20), I’ll be at the GAITHERSBURG Book Festival with my novel Red Team Blues; then on May 22, I’m keynoting Public Knowledge’s Emerging Tech conference in DC.

On May 23, I’ll be in TORONTO for a book launch that’s part of WEPFest, a benefit for the West End Phoenix, onstage with Dave Bidini (The Rheostatics), Ron Diebert (Citizen Lab) and the whistleblower Dr Nancy Olivieri.

America is a world leader in allowing private companies to levy taxes on its citizens, including (stay with me here), a tax on paying your taxes.

In most of the world, the tax authorities prepare a return for each taxpayer, sending them a prepopulated form with all their tax details — collected from employers and other regulated entities, like pension funds and commodities brokers, who must report income to the tax office. If the form is correct, the taxpayer signs it and sends it back (in some countries, taxpayers don’t even have to do that — they just ignore the return unless they want to amend it).

No one has to use this system, of course. If you have complex finances, or cash income that doesn’t show up in mandatory reporting, or if you’d just prefer to prepare your own return or pay an accountant to do so for you, you can. But for the majority of people, those with income from a job or a pension, and predictable deductions, say, from caring for minor children, filing your annual tax return takes between zero and five minutes and costs absolutely nothing.

Not so in America. America is one of the very few rich countries (including Canada, though this is changing), where the government won’t just send you a form containing all the information it already has, ready to file. As is common in complex societies, America has a complex tax code (further complexified by deliberate obfuscation by billionaires and their lickspittle Congressjerks, who deliberately perforate the tax code with loopholes for the ultra-rich):

https://pluralistic.net/2021/08/11/the-canada-variant/#shitty-man-of-history-theory

That complexity means that most of us can’t figure out how to file our own taxes, at least not without committing scarce hours out of the only life we will ever have to poring over the ramified and obscure maze of tax-law.

Why doesn’t the IRS just send you a tax-return? Well, because the tax-prep industry — an oligopoly dominated by a handful of massive, ultra-profitable firms — bribes Congress (that is, “lobbies”) to prohibit this. They are aided in this endeavor by swivel-eyed lunatic anti-tax obsessives, like Grover Nordquist and Americans for Tax Reform, who argue that paying taxes should be as difficult and painful as possible in order to foment opposition to taxation itself.

The tax-prep industry is dominated by a single firm, Intuit, who took over tax-prep through its anticompetitive acquisition of TurboTax, itself a chimera of multiple companies gobbled up in a decades-long merger orgy. Inuit is a freaky company. For decades, its defining CEO Brad Smith ran the company as a cult of personality organized around his trite sayings, like “Do whatever makes your heart beat fastest,” stenciled on t-shirts worn by employees. Other employees donned Brad Smith masks for selfies with their Beloved Leader.

Smith’s cult also spent decades lobbying to keep the IRS from offering a free filing service. Instead, Intuit joined a cartel that offered a “Free File” service to some low- and medium-income Americans:

https://www.propublica.org/article/inside-turbotax-20-year-fight-to-stop-americans-from-filing-their-taxes-for-free

But the cartel sabotaged Free File from the start. They blocked search engines from indexing their Free File services, then bought Google ads for “free file” that directed searchers to soundalike programs (“Free Filing,” etc) that hit them for hundreds of dollars in tax-prep fees. They also funneled users to versions of Free File they were ineligible for, a fact that was only revealed after the user spent hours painstaking entering their financial information, whereupon they would be told that they could either start over or pay hundreds of dollars to finish filing with a commercial product.

Intuit also pioneered the use of binding arbitration waivers that stripped its victims of the right to sue the company after it defrauded them. This tactic blew up in Intuit’s face after its victims banded together to mass-file thousands of arbitration claims, sending the company to court to argue that binding arbitration wasn’t enforceable after all:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/02/24/uber-for-arbitration/#nibbled-to-death-by-ducks

But justice eventually caught up with Intuit. After a series of stinging exposes by Propublica journalists Justin Elliot, Paul Kiel and others, NY Attorney General Letitia James led a coalition of AGs from all 50 states and DC that extracted a $141m settlement for 4.4 million Americans who had been tricked into paying for Turbotax services they were entitled to get for free:

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/turbotax-to-begin-payouts-after-it-cheated-customers-new-york-ag-says/ar-AA1aNXfi

Fines are one thing, but the only way to comprehensively end the predatory tax-prep scam is to bring the USA kicking and screaming into the 20th century, when most of the rest of the world brought in free tax-prep for ordinary income earners. That’s just what’s happening: the IRS is trialing a free tax prep service for next year’s tax season:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/05/15/irs-free-file/

This, despite Intuit’s all-out blitz attack on Congress and the IRS to keep free tax-prep from ever reaching the American people:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/02/20/turbotaxed/#counter-intuit

That charm offensive didn’t stop the IRS from releasing a banger of a report that made it clear that free tax-prep was the most efficient, humane and cost-effective way to manage an advanced tax-system (something the rest of the world has known for decades):

https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p5788.pdf

Of course, Intuit is furious, as in spitting feathers. Rick Heineman, Intuit’s spokesprofiteer, told KQED that “A direct-to-IRS e-file system is wholly redundant and is nothing more than a solution in search of a problem. That solution will unnecessarily cost taxpayers billions of dollars and especially harm the most vulnerable Americans.”

https://www.kqed.org/news/11949746/the-irs-is-building-its-own-online-tax-filing-system-tax-prep-companies-arent-happy

Despite Upton Sinclair’s advice that “it is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it,” I will now attempt to try to explain to Heineman why he is unfuckingbelievably, eye-wateringly wrong.

“e-file…is wholly redundant”: Well, no, Rick, it’s not redundant, because there is no existing Free File system except for the one your corrupt employer made and hid “in the bottom of a locked filing cabinet stuck in a disused lavatory with a sign on the door saying ‘Beware of the Leopard.’”

“nothing more than a solution in search of a problem”: The problem this solves is that Americans have to pay Intuit billions to pay their taxes. It’s a tax on paying taxes. That is a problem.

“unnecessarily cost taxpayers billions of dollars”: No, it will save taxpayers the billions of dollars (they pay you).

“harm the most vulnerable Americans”: Here is an area where Heineman can speak with authority, because few companies have more experience harming vulnerable Americans.

Take the Child Tax Credit. This is the most successful social program in living memory, a single initiative that did more to lift American children out of poverty than any other since the days of the Great Society. It turns out that giving poor people money makes them less poor, which is weird, because neoliberal economists have spent decades assuring us that this is not the case:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/16/mortgages-are-rent-control/#housing-is-a-human-right-not-an-asset

But the Child Tax Credit has been systematically sabotaged, by Intuit lobbyists, who successfully added layer after layer of red tape — needless complexity that makes it nearly impossible to claim the credit without expert help — from the likes of Intuit:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/06/29/three-times-is-enemy-action/#ctc

It worked. As Ryan Cooper writes in The American Prospect: “between 13 and 22 percent of EITC benefits are gulped down by tax prep companies”:

https://prospect.org/economy/2023-05-17-irs-takes-welcome-step-20th-century/

So yes, I will defer to Rick Heineman and his employer Intuit on the subject of “harming the most vulnerable Americans.” After all, they’re the experts. National champions, even.

Now I want to address the peply guys who are vibrating with excitement to tell me about their 1099 income, the cash money they get from their lemonade stand, the weird flow of krugerrands their relatives in South African FedEx to them twice a year, etc, that means that free file won’t work for them because the IRS doesn’t actually understand their finances.

That’s a hard problem, all right. Luckily, there is a very simple answer for this: use a tax-prep service.

Actually, it’s not a hard problem. Just use a tax-prep service. That’s it. No one is going to force you to use the IRS’s free e-file. All you need to do to avoid the socialist nightmare of (checks notes) living with less red-tape is: continue to do exactly what you’re already doing.

Same goes for those of you who have a beloved family accountant you’ve used since the Eisenhower administration. All you need to do to continue to enjoy the advice of that trusted advisor is…nothing. That’s it. Simply don’t change anything.

One final note, addressing the people who are worried that the IRS will cheat innocent taxpayers by not giving them all the benefits they’re entitled to. Allow me here to simply tap the sign that says “between 13 and 22 percent of EITC benefits are gulped down by tax prep companies.” In other words, when you fret about taxpayers being ripped off, you’re thinking of Intuit, not the IRS. Just calm down. Why not try using fluoridated toothpaste? You’ll feel better, and I promise I won’t tell your friends at the Gadsen Flag appreciation society.

Your secret is safe with me.

Catch me on tour with Red Team Blues in Toronto, DC, Gaithersburg, Oxford, Hay, Manchester, Nottingham, London, and Berlin!

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this thread to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/17/free-as-in-freefile/#tell-me-something-i-dont-know

[Image ID: A vintage drawing of Uncle Sam toasting with a glass of Champagne, superimposed over an IRS 1040 form that has been fuzzed into a distorted halftone pattern.]

#pluralistic#earned income tax credit#eitc#irs#grover nordquist#guillotine watch#turbotax#taxes#death and taxes#freefile#monopoly#intuit

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

Urea Market: Is an Oligopoly Possible?

Given the concentrated nature of its production, there is speculation about whether urea producers could form an oligopoly to control market prices.

In 2023, global urea production reached approximately 185 million metric tons, marking a significant milestone for the fertiliser industry. Without a doubt, urea is the king of fertilisers. It is often said that it is unlikely for urea to be strong while the rest of the fertiliser market is weak, and vice versa. Though there may be divergence, it is seldom sustained. Urea production continues to grow, driven by increasing agricultural demands, particularly in regions with high population growth and food security concerns.

The urea market is characterised by a few large producer countries that dominate global production. Key players include China, Middle Eastern and North African countries, Russia, and the US. These countries possess significant natural gas reserves, the primary feedstock for urea production, giving them a substantial cost advantage.

China, for instance, is not only the largest producer but also a major exporter, usually supplying between 5-5.5 million metric tons annually. Similarly, countries in the Middle East leverage their abundant and cheap natural gas to produce urea at a lower cost, making them significant players in the global market. The concentration of production within a few regions and companies suggests that these producers have the potential to influence market prices.

An oligopoly is a market structure where a small number of firms hold significant market power, enabling them to influence prices. For urea producers, this possibility exists given the market’s concentration. The actions of major producers, particularly in times of market stress, can significantly affect global prices.

For example, China’s recent reduction in urea exports during the first half of 2024, where it only exported 220,000 metric tons compared to its usual 5-5.5 million metric tons, indicates a strategic manipulation of supply. This sharp reduction could be seen as an attempt to influence global prices, especially if done in coordination with other large producers. However, in this particular case, it has had the opposite effect, controlling price increases domestically rather than internationally.

If key producers like China, the Middle East, and Russia were to coordinate their production levels, they could theoretically control supply and, by extension, the market price. Such coordination could involve reducing output during times of excess supply or increasing it to capitalise on high demand periods, thereby stabilising or even raising prices to their benefit.

However, the formation of an effective oligopoly in the urea market faces several challenges. First, the global nature of the market means that any collusion would require cooperation among countries with different economic goals and domestic needs. For instance, while China might reduce exports to influence global prices, it also needs to ensure domestic supply to avoid inflation and food security issues at home.

Second, the entry of new producers and the expansion of production capacities in other regions could dilute the power of established players. For example, Africa has been increasing its production capacity, with countries like Nigeria emerging as significant producers. This diversification of supply sources can reduce the effectiveness of any coordinated effort by traditional producers.

Third, regulatory scrutiny, especially from importing countries, could pose a significant barrier. Countries reliant on urea imports might impose trade restrictions or seek alternative suppliers if they suspect price manipulation. Moreover, international trade organisations might view such collusion as anti-competitive behaviour, leading to sanctions or tariffs that could hurt the producers involved.

While the concentrated nature of urea production suggests the potential for oligopolistic behaviour, several factors limit the feasibility of such an arrangement. The need for domestic stability, the emergence of new producers, and the threat of regulatory intervention make it difficult for urea producers to form a lasting and effective oligopoly.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Navigating the Market Dynamics of Oligopolistic Firms: Strategies for Success

In the vast landscape of market structures, oligopolistic firms stand out as influential players, wielding considerable power and shaping industry dynamics. Defined by a small number of dominant firms competing in the market, oligopolies present unique challenges and opportunities for businesses and consumers alike. Understanding the intricacies of oligopolistic markets is essential for navigating their complexities and devising effective strategies for success.

Unveiling the World of Oligopolistic Firms

Oligopolistic firms operate in markets characterized by a limited number of competitors, each possessing significant market share and influence. These firms often dominate industries such as telecommunications, automotive manufacturing, and consumer electronics, where barriers to entry are high, and economies of scale play a crucial role. Unlike perfect competition or monopolistic competition, where numerous small firms compete or a single firm dominates, respectively, oligopolies feature a small number of large firms vying for market control.

Oligopolistic firms wield considerable power in the marketplace due to their size, resources, and market share. Their dominance often stems from factors such as economies of scale, technological advancements, and strategic alliances. These firms invest heavily in research and development, innovation, and marketing to maintain their competitive edge and strengthen their position in the market. As a result, they exert a significant influence on pricing, product offerings, and industry trends.

The behavior of oligopolistic firms is characterized by strategic interactions and interdependence. Unlike firms in perfectly competitive markets, which operate independently and have no influence over market prices, oligopolistic firms closely monitor and respond to each other’s actions. Decisions regarding pricing, production levels, and marketing strategies are often made with careful consideration of competitors’ responses, as firms seek to maximize their own profits while anticipating and countering rival moves.

One of the defining features of oligopolistic markets is the prevalence of non-price competition. Rather than engaging solely in price wars, oligopolistic firms differentiate themselves through product quality, branding, customer service, and innovation. This focus on non-price factors allows firms to maintain profitability and sustain market share without resorting to drastic price reductions, thereby avoiding detrimental effects on industry profitability.

Despite their advantages, oligopolistic firms face unique challenges and risks. The intense competition among a small number of players can lead to collusion, price-fixing, and anti-competitive behavior, prompting regulatory scrutiny and legal intervention. Additionally, the presence of dominant firms may deter new entrants, stifling innovation and limiting consumer choice. Furthermore, fluctuations in market demand, changes in consumer preferences, and technological disruptions pose ongoing threats to the stability and sustainability of oligopolistic firms.

In conclusion, oligopolistic firms occupy a prominent position in the modern economy, exerting significant influence over markets and shaping industry dynamics. Their strategic behavior, market power, and focus on non-price competition distinguish them from firms in other market structures. While oligopolies offer advantages such as economies of scale and innovation, they also face challenges related to competition, regulation, and market instability. By understanding the intricacies of oligopolistic markets, stakeholders can navigate the complexities of competition, regulation, and innovation to achieve sustainable growth and prosperity.

Dynamics of Oligopolistic Markets

The unique structure of oligopolistic markets gives rise to distinctive dynamics and strategic interactions among firms. Key features of oligopolies include:

1. Interdependence

Oligopolistic firms are acutely aware of the actions and strategies of their competitors, leading to a high degree of interdependence. Each firm’s decisions regarding pricing, product differentiation, and marketing initiatives can significantly impact its competitors’ behavior and overall market outcomes.

2. Strategic Behavior

Firms in oligopolistic markets engage in strategic behavior, carefully considering their rivals’ responses when making business decisions. Pricing strategies, for example, often involve strategic pricing to anticipate and counter competitors’ moves while maximizing profitability.

3. Non-Price Competition

While pricing strategies are important in oligopolies, non-price competition also plays a significant role. Firms differentiate their products through branding, innovation, customer service, and advertising to gain a competitive edge and enhance market share.

4. Barriers to Entry

Oligopolistic markets typically feature high barriers to entry, such as substantial capital requirements, economies of scale, and regulatory hurdles. This barrier to entry limits the number of firms entering the market, allowing existing oligopolistic firms to maintain their dominance.

Strategies for Success in Oligopolistic Markets

Navigating the complexities of oligopolistic markets requires astute strategic planning and a deep understanding of market dynamics. Several strategies can help oligopolistic firms thrive in competitive environments:

1. Strategic Alliances and Collaborations

Oligopolistic firms may form strategic alliances or collaborations with competitors to pool resources, share technology, and access new markets. Joint ventures and partnerships can enhance competitiveness and drive innovation.

2. Differentiation and Innovation

Investing in product differentiation and innovation is essential for standing out in oligopolistic markets. By offering unique features, superior quality, or innovative solutions, firms can capture consumer loyalty and command premium prices.

3. Price Leadership

In some cases, a dominant firm may emerge as a price leader, setting the benchmark for prices in the industry. By strategically adjusting prices, the price leader can influence competitors’ pricing decisions and market dynamics.

4. Focus on Customer Experience

Oligopolistic firms can gain a competitive advantage by prioritizing customer experience and satisfaction. Providing exceptional service, personalized offerings, and seamless purchasing experiences can foster customer loyalty and differentiate the firm from competitors.

5. Anticipating and Responding to Competitor Actions

Vigilance is key in oligopolistic markets, where competitors’ actions can have significant repercussions. Oligopolistic firms must continuously monitor competitors’ strategies and market trends to anticipate changes and respond effectively.

Challenges and Considerations

Despite their strategic advantages, oligopolistic firms face several challenges and considerations:

1. Antitrust Regulation

Oligopolistic markets often attract regulatory scrutiny due to concerns about anti-competitive behavior and market dominance. Firms must navigate antitrust regulations and ensure compliance to avoid legal repercussions.

2. Risk of Collusion

The high level of interdependence among oligopolistic firms raises concerns about collusion and cartel behavior. Engaging in anti-competitive practices such as price-fixing or market allocation can lead to severe penalties and damage to the firm’s reputation.

3. Dynamic Market Conditions

Oligopolistic markets are characterized by rapid changes and uncertainties, driven by technological advancements, shifting consumer preferences, and regulatory developments. Oligopolistic firms must adapt quickly to evolving market conditions to maintain their competitive edge.

Conclusion

In conclusion, oligopolistic firms occupy a central position in the economic landscape, wielding significant influence and shaping market dynamics. Understanding the unique characteristics and strategic considerations of oligopolistic markets is essential for firms seeking to thrive in competitive environments. By leveraging strategic alliances, differentiation strategies, and a focus on customer experience, oligopolistic firms can navigate challenges, seize opportunities, and achieve sustainable growth in dynamic and evolving markets. As competition intensifies and markets evolve, the ability to anticipate, adapt, and innovate will be paramount for oligopolistic firms aiming to maintain their competitive advantage and drive success.

Also Read: Unlocking Success Through Effective Stakeholder Engagement Strategies

0 notes

Text

Rising Unaffordable Healthcare Cost

Name: Peter Ou

ID: 16066938

I. Introduction:

Ask anyone living in the United States of America and there would be a consensus among almost every single individual that the cost of many essential medical practices are unattainable to a large swab of the population. Although there are fierce debate over how to solve this issue through a means of either complete privatization of nationalization of the industry, the reason behind as to why the cost of healthcare is so high to begin with is often not nearly discussed enough as it should be.

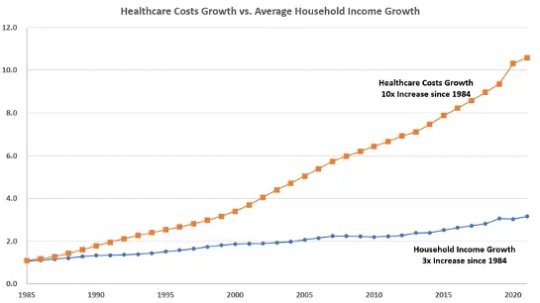

Increase in income vs healthcare cost since 1984 Income: 3x Healthcare: 10x

II. Inelastic Demand

It is to no one's surprise that the salaries people receive dramatically fails to keep up with the cost necessary to pay for the medical expense they or their family may need. One of the most important factors behind this rampant rise in price with no pushback is due to the nature of the services/goods being exchanged in this market.

The market would displays a nearly perfect inelastic demand.

A major reason as to why the price can keep rapidly expand is because the medical industry does not function in the same ways that a regular good or product does. It only takes a very brief analysis to realize that no matter how high the cost is set for consumers to get their healthcare needs, the price will never to be balanced out by the market regardless of whether a monopoly or oligopoly exists or not. This is because if the medical practice is dire and otherwise would result in the death or mortality of people, the cost is not a factor people would consider to receive treatment even if meant making bad financial decisions, going into debt. People are not able to bargain and view which hospitals or clinics offer the best prices if they are in need of a medical emergency. Also most institutions are not transparent about the expenses needed for patients' treatment. The "invisible hand" would not be applicable if the industry does not follow market principles.

III. Monopoly/Oligopoly

Due to the inherent nature of healthcare having a barrier of extremely high cost of entry and stringent regulations, the formation of corporate giants in the form of an oligopoly is inevitable without government interference. Even when anti-trust policies are enforced, every medical firm engages in price leadership since they often have control over the sale of medication and chemical compound formulas through exploitation of the patent system in courts. The barrier to entry is also caused through the amount of capital needed to be invested for a company to have success in having its own research and market share. Important regulations that ensure the safety behind the products being produced also add extra cost to the development of new drugs and practices.

Larges medical companies by market cap.

IV. Opportunity Cost

Since the risk behind formulating new medication is high in comparison to the payout, many companies will choose to make slight alterations to previous products in order to regain patent access. There is no incentive for pharmaceutical firms to invent permanent cures because it would reduce their total marginal revenue and profits. The opportunity to create new breakthroughs and boundaries in healthcare is limited due to the market and profit seeking organization of the industry. A more efficient structure would need to be put in place to maximize productivity and operate at a socially optimal equilibrium. In the end, the loss is place back into the hands of the consumers as we experience more expensive increases in the rate we pay to afford services needed for the health and overall output of the workforce in the economy.

0 notes

Text

Legal Challenges in Sports

The world of sports, where passion and competition intertwine, can also be a complex legal landscape.

‘From contract disputes to doping scandals, athletes, teams, and organisations face a wide range of legal challenges that can affect their reputation, finances, and future,’ says Michael Gorman Attorney. Navigating these complexities requires a clear understanding of relevant laws, proactive strategies, and the ability to collaborate with experienced legal professionals. Read on as Michael Gorman Attorney, renowned Portland attorney and sports experts explores the common legal sports issues and how to navigate them.

For instance, The NFL faced numerous lawsuits from former players suffering from long-term health consequences, including concussions. This case resulted in changes to game rules, medical protocols, and financial settlements for affected players, Michael Gorman Attorney explains.

Contractual Matters:

At the heart of many legal challenges in sports lie contractual disputes. Athletes, coaches, and sports organisations engage in agreements that delineate responsibilities, compensation, and terms. Breaches of contract, whether related to sponsorship deals, player contracts, or endorsement agreements, often lead to legal proceedings. Negotiating and drafting clear, enforceable contracts is essential to preempt such challenges.

Player Discipline:

Sports leagues and governing bodies maintain codes of conduct to ensure fair play and uphold the integrity of the game. Legal challenges arise when disciplinary actions, such as suspensions or fines, are contested. Players may challenge decisions based on procedural errors, inconsistencies, or disproportionate penalties. The delicate balance between maintaining order and respecting players’ rights requires careful legal navigation.

Doping and Performance Enhancement:

The battle against doping remains a prominent legal issue in sports. Athletes accused of using banned substances contest allegations, questioning testing methods and challenging sanctions. Legal frameworks must continually adapt to advancements in doping detection technology, necessitating a dynamic approach to regulating and enforcing anti-doping rules.

Intellectual Property Rights:

Sports teams and athletes often rely on their brand image for financial success. Protecting trademarks, logos, and other intellectual property becomes crucial in a world where unauthorised use and infringement are prevalent. Legal battles over branding, merchandise, and sponsorship rights underscore the importance of a robust intellectual property strategy in the sports industry.

Health and Safety Concerns:

In recent years, the legal landscape in sports has grappled with issues related to player safety and health. Concussion-related lawsuits, for instance, highlight the evolving understanding of the long-term impact of sports-related injuries. Sports organisations face legal challenges in implementing and enforcing measures to safeguard the well-being of athletes.

Discrimination and Equality:

The push for inclusivity and equality has led to legal challenges addressing discrimination based on race, gender, and sexual orientation in sports. Athletes, coaches, and administrators increasingly challenge discriminatory practices, pushing for fair treatment and opportunities for all. Courts play a pivotal role in shaping policies that promote inclusivity and combat discrimination.

Technology and Surveillance:

Advancements in technology have introduced new legal challenges in sports. From the use of performance-enhancing wearables to privacy concerns related to surveillance cameras in sports venues, the legal framework must adapt to these technological shifts. Striking a balance between innovation and safeguarding individual rights is an ongoing challenge.

Antitrust Issues:

Sports leagues often operate as monopolies or oligopolies, leading to antitrust concerns. Legal challenges may arise when leagues impose restrictive rules that limit players’ mobility or when they engage in practices that stifle competition. Antitrust litigation in sports aims to ensure a fair playing field for athletes and promote healthy competition among teams.

Media and Defamation:

Sports figures are often in the public eye, vulnerable to defamation through inaccurate or misleading media coverage. Protecting one’s reputation requires understanding defamation laws and seeking legal counsel when necessary.

Strategies for Navigating Legal Challenges

Michael Gorman Attorney suggests strategies that can help tackle legal challenges in the dynamic world of sports.

Proactive Risk Management:

Implementing preventative measures, such as clear policies, regular compliance audits, and training programs, can minimise legal risks and mitigate potential issues before they arise.

Open Communication and Dispute Resolution:

Fostering open communication and utilising alternative dispute resolution methods like mediation or arbitration can often resolve issues effectively before resorting to litigation.

Seek Legal Counsel:

Consulting with experienced sports law professionals is crucial for navigating complex legal situations. Attorneys can provide legal advice, draft contracts, represent clients in court, and guide them through legal processes.

Stay Informed:

The legal landscape in sports is constantly evolving. Athletes, teams, and organisations must stay updated on new regulations, court rulings, and best practices to stay compliant and proactive.

Conclusion

Navigating legal challenges in sports requires a multifaceted approach. Proactive risk management, open communication, seeking legal counsel, and staying informed are key strategies for athletes, teams, and organisations to ensure compliance, mitigate risks, and protect their interests. By understanding the legal landscape and adopting strategic approaches, the world of sports can strive for fairness, integrity, and sustainable success.

0 notes

Photo

Get smart with 'Cyberfeminism Index,' Mindy Seu's galvanizing (to say the least) 608-page compendium of radical techno-critical activism by hackers, scholars, artists and activists of all races, religions and sexual orientations, published by the big-picture-thinkers at @inventorypress @mindyseu writes, “As of this printing, the 'Cyberfeminism Index' traces three decades of global cyberfeminism. But, like cyberfeminism itself—permeable, malleable, and anti-canonical—the index is still in progress. More than a historical overview, this publication was initiated by and is being released into a specific context, one in which platform oligopolies reign supreme, surveillance capitalism commodifies us, and techno-dystopia looms. Its existence reflects that reality. The book is also imperfect: the version printed here is messy, with blindspots and selected truths. Despite my collaborators’ and my attempted thoroughness in gathering the entries herein, many voices are left unaccounted for. Still, as a compilation of a wide sample of techno-critical works, the 'Cyberfeminism Index' might reveal potential for acts we can take to reclaim cyberspace not as a utopia, but as a space for skepticism, growth and entanglement. Here, multiple histories diverge, juxtaposing and complementing their varying ideologies and motivations, and they will continue to beyond these pages. This is not the index of cyberfeminism, but a document of—and another moment of—its mutation.” Contributors include: @skawennati Charlotte Web, Melanie Hoff, Constanza Pina, Melissa Aguilar, Cornelia Sollfrank, Paola Ricaurte Quijano, @marymaggic Neema Githere, Helen Hester, Annie Goh, @vns_matrix Klau Chinche / Klau Kinky and Irina Aristarkhova. Read more via linkinbio. #mindyseu #cyberfeminismindex #cyberfeminism #technoactivism #cyberactivism https://www.instagram.com/p/CpnUoF6uYn9/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

The American DreamUnit 1 OverviewAs you consider the concepts that we have dealt with in this first unit, implicit in these free market ideas is the conclusion that markets measure scarcity and allocate scarce resources through the pricing mechanism. In addition, consumers dictate to markets what and how much to produce and income and wealth is determined by individual productivity/ingenuity. Adam Smith saw competition as the “invisible hand” that would keep the playing field level for everyone. It was believed, at least in the beginning of a market economy, that these mechanisms—over time--will always maintain a stable, growing, full employment economy. It also assumes that you don’t tamper with free markets and that the proper incentive is present to reward all who are providing resources, i.e., capital, labor or entrepreneurs.Historically, we have seen an evolution of economic and political thought as we have dealt with the many changes and challenges that have occurred. These challenges have prompted a closer examination of our basic assumptions about our market economy. Our founding fathers saw government as having a very limited role—maintain an army and a navy to protect our shores and a political/legal system to make and enforce laws and to settle disputes. This would seem to support the argument today that government should be much smaller and that the private sector always has the better answer.The reality is that our economic/political system today has evolved and changed as result of the many historical events has occurred. Our reaction to these events have suggested that, although a market economy has worked very well for us, there may be a few inherent problems that do not have a built-in answer.The Sherman Anti-Trust act of 1890 marks the first of these worries. Given the growth and power of certain industries (such as Standard Oil of New Jersey) we saw markets being dominated by one firm (monopoly) or a small number of firms (oligopoly). Conclusion: it is hard to have a market economy without competition. The question, of course, is how to deal with this kind of economic/market power. The approach that was used in the late19th century was to turn the Federal government was the only entity that had enough power to break up these giant trusts and return to a competitive market. The legislation did just that, although it took nearly two decades.By the late 1800s and early 1900s we were seeing an additional problem…the exploitation of labor. Working conditions, especially in industries such as mining and heavy manufacturing, was extremely difficult. Low pay, long hours, the danger to workers and the impact on their overall health was increasingly an issue. To deal with this problem, we again turned to government to pass laws that would mitigate some of these problems. Whether this was consistent with a market economy is still being debated.The 1930s presented the most difficult economic challenge that we have ever faced. It meant that we had to re-examine another fundamental belief about our free market system, i.e. the belief that it will always return to a stable and full-employment state because of certain built-in market devices. As we waited from 1928 to 1932 for this to take place our economy literally imploded. GDP dropped by almost 50% and employment was at least 25%. Given this kind of crisis, we turned again to government. Rugged Individualism and the American DreamPresident Herbert Hoover is credited with the term “rugged individualism” and felt that it described a spirit and energy that was unique to the United States. It was a belief in individual initiative, personal freedom and responsibility which he felt was at the heart of our system. It also suggested that everyone had equal opportunity for personal success if they were willing to work hard. The general belief was that government had no role or responsibility in this process.Here is an excerpt

from his last speech before he was elected President in 1928:…And what has been the result of the American system? Our country has become the land of opportunity to those born without inheritance, not merely because of the wealth of its resources and industry but because of this freedom of initiative and enterprise. Russia has natural resources equal to ours.... But she has not had the blessings of one hundred and fifty years of our form of government and our social system.:…By adherence to the principles of decentralized self-government, ordered liberty, equal opportunity, and freedom to the individual, our American experiment in human welfare has yielded a degree of well-being unparalleled in the world. It has come nearer to the abolition of poverty, to the abolition of fear of want, than humanity has ever reached before. Progress of the past seven years is proof of it....The greatness of America has grown out of a political and social system and a method of [a lack of governmental] control of economic forces distinctly its own our American system which has carried this great experiment in human welfare farther than ever before in history.... And I again repeat that the departure from our American system... will jeopardize the very liberty and freedom of our people, and will destroy equality of opportunity not only to ourselves, but to our children....”When financial markets virtually collapsed in 1929 and 1930 these words did not sound quite the same.Another important term was coined during this same prolonged period of economic, political and social turmoil. Historian James Truslow Adams wrote of “the American dream” in his 1931 book, The Epic of America. He could not have anticipated the impact of this phrase would have and how it would endure. Although the phrase was similar to Hoover’s “rugged individualism” idea the “American Dream” described a belief that related more to our personalized expectations of opportunity and success. Although we have come to associate this phrase more with money and possessions, Adams defined this phrase quite differently. Here is the original quote from the Library of Congress:“It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position.”Apparently, Adams originally intended "the American dream" to describe equality across all classes of people. The phrase has changed somewhat over the years and would probably be defined by most today in purely economic terms—opportunity, a good job, advancement, security, a home and car, etc. Although difficult to define, and even more difficult to measure, the “American dream” has become an important part of our culture.Although most of our problems during the middle and latter part of the 20th century were not as severe as the 1930s, we continue to struggle with economic instability and the inevitable consequences that it brings. For most of our history, however, there has been one constant in all of this change—the belief that everyone in this country should have the opportunity for a better life and that hard work was the key to success. For many generations this perception and hope brought many people to our shores from throughout the worldThe role of government in all of this has been vigorously debated for most of our history. In Unit 2 we will discuss the economic functions of government in much more detail and also examine the impact of public policy and taxation on this issue.In this first discussion board I am asking you to focus more on the individual. As citizens, what do we have a right to expect—if anything? Is the American Dream still a reality for all or is it only a reality for some?Grading GuidelinesDiscussion Board # 1These same guidelines will be used on all of the discussion board (reaction paper) assignments.

I have attached the URL for the PBS video on this topic as well as some additional sources. You are invited and encouraged to review other sources on this topic. Please review all of these before you begin and use them to support your own conclusions.Questions: Answer fully and in detail.1. How would you define the American Dream? How important is money as a measure of success?2. Is this idea unique to the USA? Is there a Canadian, British or Scandinavian dream? Was it originally intended to be unique to the USA?3. As individuals, do we have a right to expect certain things to be provided by the system, such as health care, education, minimum level of subsistence, food/ shelter, etc.?4. Is the American dream still a possibility for those who are new to this country?5. Is it still realistic to think about becoming wealthy in this country?6. How would you answer critics who say that the “American Dream” has become the “American Daydream” with hopes of a lottery win or TV show fame rather than hard work?7. What role—if any—should government assume in keeping the dream alive?8. The American Dream is almost impossible to separate from our work ethic…should we pay more attention to the non-work part of our lives? The Europeans say that we live to work and they work to live. Who comes closer to the ideal?9. Are you happier if you are wealthier?This video is a bit dated but still provides wonderful insight into the development of the American Dream—especially after the Coronavirus and the unrest that has swept most of the country.The video may require some time to buffer but there is also a written transcript below the viewing window.Video: http://billmoyers.com/segment/angela-glover-blackwell-on-the-american-dream/#.UEo1tzoYfLw.emailArticles:https://www.brookings.edu/articles/is-the-american-dream-really-dead/https://www.aei.org/economics/american-dream-mobility-opportunity-or-redistribution/https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017/jun/20/is-the-american-dream-really-deadHappiness and the Dreamhttps://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2019/03/21/americans-are-unhappiest-theyve-ever-been-un-report-finds-an-epidemic-addictions-could-be-blame/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.83e54f2d8045

0 notes

Text

Amazon’s Greatest Weapon Against Unions: Worker Turnover

The Seattle Times conducted its own analysis of Amazon’s workforce data last year, putting the company’s turnover at 111% during the pandemic. A New York Times investigation published this week put the figure even higher, at 150%, showing that Amazon was shedding 3% of its workers every week before the pandemic began.

A turnover rate above 100% doesn’t mean every single worker quits or gets fired in a year: It means the number of workers who leave is greater than the average number of workers employed during the same time period. So while some workers may last years, others last days. Under a turnover rate of 100%, every theoretical position inside the warehouse would turn over once in a year, on average.

That has huge implications for organizing.

Before the National Labor Relations Board schedules an election, a union must secure signed union authorization cards from at least 30% of the workers in an expected bargaining unit. In reality, a union wants far more than that ― ideally two-thirds or greater ― since they will need to win a majority of votes cast, and the employer may launch an anti-union campaign that weakens support.

At an Amazon warehouse, high turnover means a union would be losing cards every day as workers leave and new employees unfamiliar with the campaign replace them. Even if the union manages to win an election, high turnover could hurt its position at the bargaining table if some of the most active organizers have quit or been fired. And churn could even help the employer purge the union from the facility by convincing newer workers to decertify it....

On a more fundamental level, high turnover makes it harder to build solidarity. Those who come to see the warehouse as just a place to get a paycheck for a few months would feel less invested in the job, or a campaign to improve it. Workers who barely know one another would be less likely to trust each other or take risks together.

Gene Bruskin, a longtime labor organizer, said Amazon’s turnover also creates basic logistical hurdles as workers try to establish networks. Bruskin is in regular touch with Amazon workers who are trying to organize their warehouses.

“When you’re trying to build a committee and sort of track leadership, map the place out and figure out where your good connections are, you just can’t count on that,” Bruskin said. “The best you can do, knowing that you’re going to lose a lot of folks, is to try and create a culture of solidarity and activity … so that when somebody [new] comes in they sort of pick up the vibe. You just can’t be as dependent on a particular group of people.”...

Amazon openly encourages some of the turnover, offering employees annual buyouts to leave the company if they believe Amazon isn’t right for them. Under the pay-to-quit program, workers with a year under their belts are eligible for $2,000 or more to leave under the condition they can never return.

this is a good article, but there’s another one in harper’s with numerous anecdotes that speak to just what amazon has done to workers: Hard Bargain How Amazon turned a generation against labor

the article mentions that turnover is a big issue, but adds that this is compounded because most young people don’t have any experience with being in a union in the first place and don’t know what it is or does:

Members of Ananias’s generation are often described as digital natives. It’s a compliment—and well earned for their effortless technological fluency. But they’re also plutocracy natives, tech-oligopoly natives, and gig-economy natives who have never known an America where profitable companies are expected to offer stable, remunerative careers. Which is why, perhaps, the union divide in Bessemer felt generational. Older people of all races and political persuasions were reflexively pro-union. Younger people, even progressives, weren’t exactly anti-union but held no strong opinions. And all of a sudden they found themselves as the protagonists in the most significant union organizing drive in decades.

The union divide in the Deep South is often portrayed along racial lines, between pro-union African Americans and anti-union whites. But the generation gap I sensed seemed not to respect racial boundaries. At W.T.’s Restaurant & Lounge on the outskirts of downtown, the sign posted above the bar read,

in this place we always

salute our flag

support our troops

buy american

say “merry christmas”

say “one nation under god”

respect our law enforcement

if this offends you there’s the door

The establishment seemed particularly hung up on the Christmas thing; they still had their tree up, lights and all, in March. When I asked the bartender, a late-middle-aged white woman, what she thought about the union drive, she told me plainly, “I don’t see why they wouldn’t want it.” A pale, portly retiree sitting to my right piped up, “I was raised on union money. My daddy was a union steelworker.”

Assumptions were different at a vegan soul-food joint across town called Good Health To Be Hail. As I waited for my barbecue jackfruit sandwich to arrive, I noticed a wall calendar from the harrowing lynching memorial in Montgomery, the state capital, and a shelf full of anticorporate documentaries on DVD, including Food, Inc. and Sicko. A black graduate student who stopped in for takeout told me she’d been following the union fight on Twitter. She’d seen awful stuff, including the leaked documents about delivery drivers peeing in bottles. But she didn’t have a strong opinion on the union question. “I think that I’m not really informed,” she said.

The restaurant’s tall, fit cook told me that a few weeks earlier, a group of activists had come by and asked whether they could put up a pro-union sign out front. “I told them I’m not necessarily for it or necessarily against it, so they can use the edge of the property.”

amazon is very apt in speaking to other aspects of workers’ identities:

Amazon’s most effective union-busting tactic was requiring employees to attend so-called captive audience meetings. The presentations were a study in psychological projection. Amazon, a publicly traded for-profit corporation that maximizes shareholder value and refers to its employees as “associates,” was presented as a “family.” Meanwhile, unions—nonprofit organizations whose members call each other “brother” and “sister” and who elect their own leaders—were framed as businesses run by “bosses.” The workers were told that the union, being a business, had come to Bessemer only to squeeze a profit out of them, whereas Amazon, being a family, had arrived to aid a struggling community....

All over the fulfillment center, pro-union voices were silenced while those of no-voters were amplified. Near the main entrance, flatscreen monitors on a red carpet were cordoned off with a velvet rope. The screen on the left showed testimonials from employees who had pursued health-care and IT jobs through the company’s Career Choice program. On the right was a Black History Month salute to the first African-American woman to ever serve as a U.S. ambassador. Taking center stage on screen was a certain cherubic Amazon worker with a speech bubble next to his mask-covered mouth: “We don’t need a union. . . . We have all the necessities and everything we need to be cared for here.” The quote was signed, “Carrington, Associate.”...

His chief ambition was to expand his nascent business, Carrington Cosmetics, whose name was printed in a black gothic font on his gray T-shirt. He hoped to use Amazon’s Career Choice program, which provides employees who have worked at the company for at least one year with up to $3,000 in annual tuition costs, to enroll in a cosmetology program, though that field is not typically covered. “I used to want to be a music teacher,” Carrington said. “But now I want to be a cosmetics entrepreneur. And I want to get my brand into Amazon.”...

Working at Amazon wasn’t like being a lunch lady. It wasn’t like his job at McDonald’s or at the nursing home, either. Amazon wasn’t a dead-end job; it was a gig—a stepping-stone, really. “Everybody there is family-based,” Carrington told me. “Out of everywhere I’ve worked, this is the only place where my managers are helping me, guiding me through my ventures that I want to pursue outside of Amazon. This is the only place I’ve ever been where they want you to become somebody.”...

His employer proffered different advice. “When things got serious with the union stuff, Amazon started having classes,” Carrington told me. “Amazon was very successful in educating us.” When company-produced vote no pins were made available at the warehouse, he took a public stance, attaching one to his lanyard, which was stitched with the logo of Amazon’s Black Employee Network.

As was the custom at the warehouse, Carrington had decorated his lanyard with an array of pins depicting the company’s mascot, Peccy—a neckless orange creature with the Amazon smile for a mouth. (His name derives from management’s insistence that “Amazonians” are proudly “peculiar” individuals.) Carrington still hoped to snag the rainbow gay-pride Peccy and the Black History Month Peccy, which sported an Afro.

in turn, this means workers fail to identify themselves as workers and lose class consciousness, instead thinking like bosses:

When he returned to work, Carrington observed his colleagues’ behavior. Frankly, the surveillance seemed justifiable to him. “We have people in there who’d rather be in the bathroom on their phone for fifteen to twenty-five minutes. Dozens of packages could have been processed in that time you were in the bathroom on your phone.” As an entrepreneur, he sympathized with Amazon. “If I was the boss and it was my makeup company, I would be ticked off if somebody spent this much time on their phone and a customer didn’t receive their order on time.”...

Technically, Carrington confessed, he didn’t attend church anymore. On Sundays, from 7:45 am to 6:15 pm, he was in the warehouse, on the clock. But he still tithed, contributing 10 percent of his after-tax income—about $40 a week.

“There’s a saying that what you do for God and do for his house,” he told me as we walked back to the car, “he will bless you back tenfold, whether that’s through money or a job promotion.”

To me, it seemed kind of like paying union dues. He disagreed with a vehemence that took me aback. “These fools taking money from me. What good does that do me?”

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

That’s Not Capitalism: Lightning Round

1) Cost Externalization

One of the most basic principles of Capitalism is cost should go along with risk. If a company externalizes their costs onto an uninvolved party, they are rent-seeking.

The most basic example of this is pollution, because pollution causes the financial and health costs of an enterprise on people who happen to be living nearby. Unfortunately, pollution is not as good of an example as it used to be, as pollution-capture is becoming the standard in many industries, a trend I really hope continues, but also one that is supported by Capitalism.

But, another great example is welfare. There was a city in Texes, (Houston I believe), that was having a problem, all of the new jobs in the city were not being created in the area where the poor people were who needed those jobs. They didn’t bother to try and find out WHY people were building there, they didn’t ease zoning restrictions to allow new residences to be built in the new boomtown, they jumped straight to subsidization. They wanted to make the bus between the two areas a) cheaper, and b) and express. Now, and express between two high-traffic points makes a lot of sense, and I was actually in favour of bus subsidies, until Bill Whittle pointed this out to me.

If the companies in the booming area couldn’t get enough workers, what do you think they would do? Increase pay. Increase the pay to the point that workers could afford cars, but by subsidizing the bus, (and remember, buses are already heavily subsidized in Canada and the US), they were allowing the company to pay their employees less.

Walmart is also another great example, as they have an in-house call centre who’s sole purpose is to help their employees get on welfare. Walmart moves into an area, drives wages down. They then use their monopolistic position to force their suppliers to supply them at sub-cost, forcing them to also slash their wages. Walmart could be pointed to as one of the primary causes of US wages stagnating, compared to both inflation, and also the massive increases in productivity we’ve seen.

Yes. Workers in North America are making less than they used to, despite their productivity increasing fantastically. Walmart and offshoring to China are two of the primary causes of wage stagnation in North America. Seriously, everyone complains about Amazon, but Amazon literally pays everyone at least $15/hr (USD). And this is allowed because Walmart, LITERALLY, is using the government to pay their own employees.

2) Monopoly

Monopolies (single supplier) and oligopolies (a small number of suppliers in a cartel), are almost worst-case-scenarios in Capitalism. The only thing worse than a monopoly is stagflation. What exactly to do about monopolies is a bit of a question, and anti-monopoly laws creates monopolies, paradoxically. But one of the things you can do is eliminate corporate welfare.

3) Corporate Welfare

Also not Capitalism. It’s actually Fascism. And I’m not exaggerating, it’s literally one of the primary things the major Fascists did. Again, risk is supposed to go along with rewards, and if you don’t have corporate welfare, major corporations can be utterly destroyed as quickly as small businesses. All it takes is a major corporation overexpanding at the wrong time to make their corporate model completely unsustainable. Even worse, if a competitor is able to pick up the market share, they don’t even have to expand to have their corporate financial model utterly destroyed.

What about the workers?, you might ask. Well, most of them will likely get hired by the competitors who just gained the market share. Competition is THE fundamental part of Capitalism.

4) Being Chained to a Job

The fundamental aspect of Capitalism is competition, not just on what to purchase, but where to work. If you can’t leave your job for another, that’s a monopoly.

5) Inflation

Inflation is part of Keynsian economics. They are purposefully making it hard for you to save money, and this has the effect of making it difficult for a family to carry money over time, to the point that most wealth is gone in a generation.

But, when you retire, you can’t make any more money. You are on a fixed income. Well, the government found a solution to it’s own problem, pensions, which are basically a pyramid scheme.

You see, the money you get out of a pension is not the money you put into it. The money you put into the pension fund goes to people who are currently retired. When you retire, the money you get from the pension fund will be paid by those currently working. This system barely works, so long as there is no major change in population demographics. And one thing demographers can tell you is that populations always change. We have the retiring Boomers, with subsequent generations having less kids. So, who’s going to pay for their pensions?

We honestly haven’t answered this question yet, and any semblance of sanity we have is from a massive government shell game as they move money and debt around.

6) Rising Rent Costs

If the market can respond properly, then housing will increase with demand for housing, keeping the market relatively stable. But, what we have is a system designed to prevent people from building, which is why we have cities with century-old buildings that cost an absolute fortune to live in. If a city wants to make that choice, it’s really their choice, (a choice I fundamentally disagree with), but if you do that, housing costs are going to skyrocket, and you’re going to get houses that are incredibly energy efficient, and not designed for modern living.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monopoly power and political corruption

As antitrust awakens from its 40-year, Reagan-induced coma, there’s both surging hope that we will tame corporate power, and a backlash that says that antitrust is the wrong framework for reducing the might of giant corporations.

Competition itself won’t solve problems like digital surveillance, pollution or labor exploitation. If we fetishize competition for its own sake, we could end up with a competition to see who can violate our human rights most efficiently.

https://pluralistic.net/2021/08/24/illegitimate-greatness/#peanut-butter-in-my-antitrust

Even if we do care about competition, a lack of antitrust enforcement isn’t the sole cause of concentration: patent abuse, DRM lock-in, criminalizing terms of service violation and other anticompetitive tactics suppress rival market entrants, but don’t violate antitrust.

But I’m here to say that a lack of antitrust enforcement is the way to understand the source of harms like environmental degradation and labor exploitation, and anticompetitive tactics like copyright abuse.

To explain why, I’ve published a new editorial for EFF’s Deeplinks, called “Starve the Beast: Monopoly Power and Political Corruption.”

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/08/starve-beast-monopoly-power-and-political-corruption

Here’s my core thesis: monopolized industries have high profits, which they can spend to legalize abusive conduct.

And!

Monopolized industries also have a small number of dominant companies, which makes it easier to agree on a lobbying agenda.

In other words, when an industry is reduced to just a handful of companies, they have more ammo and it’s a lot easier for them to agree on their targets — deregulation, expansions of proprietary rights, and regulatory capture.

Which is why monopoly begets monopoly! Remember the Napster era, when tech had almost no lobbying muscle and got its ass routinely handed to it by the much smaller entertainment cartel, who were represented by a handful of wildly profitable companies with lobbying armies?

Tech was disorganized and dynamic, with today’s giants becoming tomorrow’s also-rans, more concerned with fighting each other than inter-industry rivalries.

Today, with the web reduced to five giant sites filled with screenshots from the other four, it’s easy for tech leaders to agree on a common agenda, and they have So. Much. Money. to spend on lobbying to make it reality.

https://corporateeurope.org/en/2021/08/lobby-network-big-techs-web-influence-eu

Think of the absolute tsunami of fuckery the telco industry unleashed to kill net neutrality, from sending 1m anti-net neutrality comments that purported to come from Pornhub employees (!) to having those comments counted by the world’s most captured regulator, Ajit Pai.

That was an expensive war, and the way Big ISP was able to afford it was because it uses regional monopolies to screw customers and workers and amass a vast warchest of lobbying dollars — and because the industry is composed of so few companies that they all can all agree.

If we want to smash corporate power and free our lawmakers and regulators to do the people’s business, without the corrupting influence of a flood of corporate money, we have to starve the beast. Corporations deprived of monopoly profits can’t afford to lobby.

What’s more, if we demonopolize our industries — smashing the oligopolies of 1–5 companies that dominate ever sector — so that each industry is a squabbling rabble of hundreds of companies, they won’t be able to agree on how to fuck us over anymore.

Critics of Big Tech antitrust are right that it’s not enough to attack Big Tech. If we demonopolize tech without smashing the rest of its supply chain — ISPs and entertainment — then those monopolists will divide Big Tech’s share among themselves.

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/09/bust-em-all-lets-de-monopolize-tech-telecoms-and-entertainment

But that’s not a reason to leave Big Tech alone. That’s a reason to expand the antitrust agenda to every industry, to treat the fight against tech monopolies as the start, not the goal, as a way to create momentum for smashing monopolies in every sector.

We can’t afford another mistake like the one that led to the passage of 2019’s EU Copyright Directive, with its Article 17, a rule set to destroy every small EU tech platform and replace them with a Googbook-dominated filternet with our lives at the mercy of copyright bots.

During that fight, advocates for creative workers made the mistake of assuming that by advocating for entertainment monopolies against tech monopolies, they’d improve their own lives.

That’s not how it works.

The only way to improve labor’s side of the bargain is to make capital weaker. Allowing Big Tech to consolidate its position by exterminating all EU competitors in exchange for sending a few billion to Big Content will not make creative workers any richer.

Rather, it makes both industries’ monopolies stronger, and further weakens creative workers’ leverage over corporate entertainment behemoths, guaranteeing that virtually all the windfall profits from the Directive will go to shareholders, not workers.

The world deserves better than being allowed to choose which giant, abusive corporations we support in inter-industry battles — none of the giants give a shit about us, except as human shields for their own battles.

For workers, users, learners and others to come out ahead, we don’t need to pick the right source of corporate power to ally ourselves with. We need to shrink corporate power — all corporate power — until it fits in a bathtub.

And then drown it.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just planning out some ideas for a iCivics WhiteHouse's playtrough video

Hya comrades of the world, I am Klara Kér, better known as Olyvier Bouchard. We are gonna have alot of fun here, so enjoy your stay.

Beware though that as we dive deeper and deeper into the topics at hand, some of you may believe I am against the United States of America or against Republicans. Be sure that as long as you are civil in our conversation I am gonna keep a listening type of ear. Fair, is it clear now? Good, because we got alot to unpack here.

So for the Democrat policies, I stand some official ones as well as some more that are quite niche really.

Federal funding of Education: I agree upon letting some room for a private education market but I cannot stress enough how a well-funded public schools system helps the common folk into jobs and into fuller lives as well. Especially over colleges and universities where the cost of entry has expanded to ludicrous prices. So ya, get your shit together America.

LGBTQ+ rights: As of the latest anti-LGBTQ+ bills in southern America I simply can't stand how primitive some lawmakers are in the USA. It really goes to highlight how much Wilsonism has destroyed alot of potential for America as of human rights and all. When some black-colored inhabited towns are literally getting no clean water in a supposedly fist world nation that is quite the statement of ours backwaters this country is at times.

Global cooperation: We all know Trump has destroyed foreign relations with pretty much the rest of the world making it the joke it is as of today. But that ain't new really. As far back as the infamous Woodrow Wilson, we can see how America has sabotaged itself for long-term longevity barely held together by the vast quality of it's geography. America has lost Russia's trust on WW1, lost France's on WW2-Cold War period, and it is soon gotta fall because of all those poor decisions done starting from Wilson and continued by all the other folks since then.

Climate change: Sooner than later if not already, we are living in a global climate crisis that is gonna make pretty much everybody in the future hate our decision-making quite deeply. And the effects are only gonna get way worse for every second we stay in the current capitalism-induced consumerist status quo. So ya, alleviating the effects of the crisis at a incredibly deep level is pretty much what should be a main focus at the moment. And like I said, the third and second world are gotta pay for most of it whilst we are gonna pay some but definitely gonna profit more than anytihng. Make no mistake, because the steep divide and hatred of those nations towards the West is mostly of our shared society's fault and is probably gonna get real profound in no time at all.

Campaign finances Transparency: Deliberately hiding information that concerns our citizens' policies is quite bad honestly. Get your shit together Biden and answer the call of your country rising left movement caused by your predecessors' stubborness and by yourself alike. Not solving nor trying to solve the issues we got since like forever is quite fighting back against America, the World, Liberty and Progress overall.

More cultural FLOSS-ness: More affordable culture and much more proper lefty-licenced works to use would greatly benefit not simply America but the world as a whole. I mean, the situation over copyrights and reserved permissions only to big corporations is just insane. It really has to let go from those older works and we really deserve some damn free licenced works upon on hands with much easier access, also for the metadata information as well.

Adoption of FLOSS hardware and software into Government: As a Linux user over my server desktop at home besides Windows 10 over my laptop and iOS for my smartphone, I really put a emphasis upon a freer open and libre experience with governmental as some countries do elsewhere. I know the entire governmental tech situation is quite a bit slow most of the time but I think we got alot to win with minimalistic blob-free experience inside government. Especially as we can't trust big corporations to not put backdoors of their own everywhere they can.

Regulating further mega corporations and their oligopolies + encouraging smaller businesses / individuals into innovation and sustainability: I know we live in a digitalized world where big corporations seems better to offer such costful services and all but I think you underestimate the balance with the small businesses and individuals. Seriously, you should reconsider such a balance as whenever a new innovator comes by to challenge authority or even just to bring new innovative products into the market it just fails to deliver long term as they often get bought by those bigger corporations simply to bring profits and not to enhance the products really. Capitalism and consumerism 101 become also big issues with big corporations too as they are not so concerned to sustainability as smaller bodies by law are.

Supporting and legalizing Labor Unions and Cooperatives: I don't know how has America taken so long to go without supporting unions and cooperatives while the rest of the world has but this is a big problem. I know a bit about the Ben Shapiro's but are we seriously gonna trust big corporations to properly protect their employees? Of course in a ideal world we would but this Earth ain't like that my quite a margin. So ya, just looking at Desjardins, especially back in the early 20th century, you can see how decentralized and advantageous this is.

So... what's my whole opinion about the Republicans, especially as of the Trump administration? Well, I have a single word to describe it's entirety and beyond: Wilsonism. Modern 'republicans' and Conservatives could make it count but honestly all you are doing right now is pretty much fueling alot of the bad in this world really. I am building off a fantastical world of my very own for a reason. And it is to get a overall less toxic and more enjoyable world to live in. So ya, Trump and all conservatives of the world, get your entire ideology together and start building up something smarter and way more useful than just whining upon modern progress and liberal policies. I may actually help for that bit if you are sincere and honest about it but meanwhile I am gonna prepare my damn safety exit out of this really mad world. (including the details of such a better Post-Conservative movement)

And before somebody asks why I am writing all those walls of text, no worries, I have some cute animated drawings and edits on it's way as well so ya.

Still Work.In.Progress but I am gonna get there eventually with more visuals and content.

Cya mates.

1 note

·

View note

Link

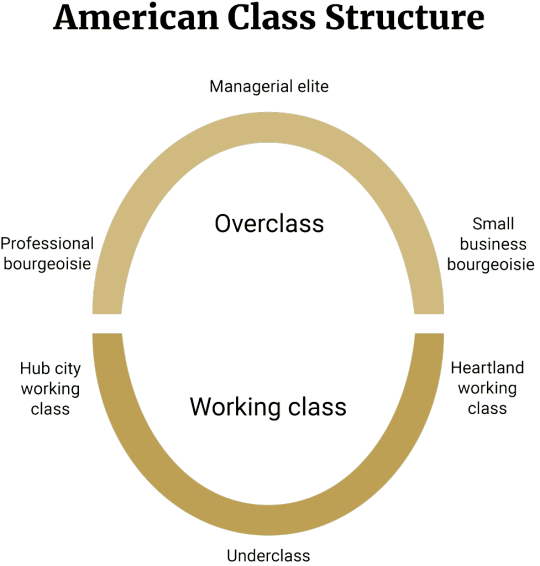

In The New Class War: Saving Democracy from the Managerial Elite (2020), building on my argument in The Next American Nation (1995), I offered an answer. I proposed that, while the proletariat is still the proletariat, James Burnham, Bruno Rizzi, John Kenneth Galbraith and other thinkers were correct that by the mid-twentieth century power had passed from individual bourgeois business owners to a new ruling class of technocrats or bureaucrats, whose income, wealth, and status is linked to their positions in large, hierarchical organizations, (i.e. nonprofits, government agencies, industrial and financial firms, and so on).

I use the term “overclass” to describe this group. A similar though not identical concept is what is known, after Barbara Ehrenreich, as the “professional-managerial class” (PMC). Whatever terminology you prefer to use, generalizations about all Western elites need to be accompanied by more granular analysis at the level of each country. Referring only to the U.S., I think it is helpful to go beyond the basic distinction between the overclass and the working class and identify distinct groups within each.

…

But the American elite includes three other groups, in addition to these bureaucratic managers. One consists of hereditary rentiers—heirs and heiresses, born into rich families. Old money types should be distinguished from tycoons like Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos, who tend to be products of upper-middle-class or modestly rich families who happened to become incredibly rich. Only the most primitive Marxists believe that a tiny group of individual capitalists—to the manor born or self-made—controls modern societies from behind the scenes. I will not pay further attention to old money in this essay.

In German a distinction has long been made between the Besitzbürgertum (propertied bourgeoisie) and the Bildungsbürgertum (educated bourgeoisie). The equivalents of these two groups exist in the U.S. today. They are distinct from the big-organization managers and important in American politics out of all proportion to their numbers. Lumping them together as “PMC” confuses matters. Let us call them the professional bourgeoisie and the small business bourgeoisie.

The professional bourgeoisie—made up of lawyers, doctors, professors, K-12 teachers, journalists, nonprofit workers, and many of the clergy—is concentrated in the teaching, helping, and research sectors. Their jobs often pay modestly but provide both status and a degree of personal autonomy that the frequently better-paid managerial functionaries in more hierarchical occupations do not possess.

The small business bourgeoisie consists of the owner-operators of small businesses and franchises, along with genuine contractors (as opposed to proletarian “gig workers”), both those who are self-employed and those who employ others.

…

The working class in the U.S. is divided as well. First, there is the heartland working class—those who work in the industries located in the low-density exurban heartland. These industries include manufacturing, agriculture, energy, retail distribution and warehousing.