#alan hollinghurst

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fave Five: Gay Fiction Set in the 1980s

These are all Adult fiction; YA will be posted separately. My Government Means to Kill Me by Rasheed Newson Disco Witches of Fire Island by Blair Fell Swimming in the Dark by Tomasz Jedrowski The Line of Beauty by Alan Hollinghurst Rent Boy by Gary Indiana Bonus: For books that cover multiple decades including the 80s, check out Tramps Like Us by Joe Westmoreland, A Language of Limbs by Dylin…

View On WordPress

#80s#A Language of Limbs#Alan Hollinghurst#Blair Fell#Disco Witches of Fire Island#Dylin Hardcastle#Gary Indiana#Joe Westmoreland#My Government Means to Kill Me#No Other World#Rahul Mehta#Rasheed Newson#Rent Boy#Swimming in the Dark#The Line of Beauty#Tomasz Jedrowski#Tramps Like Us

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

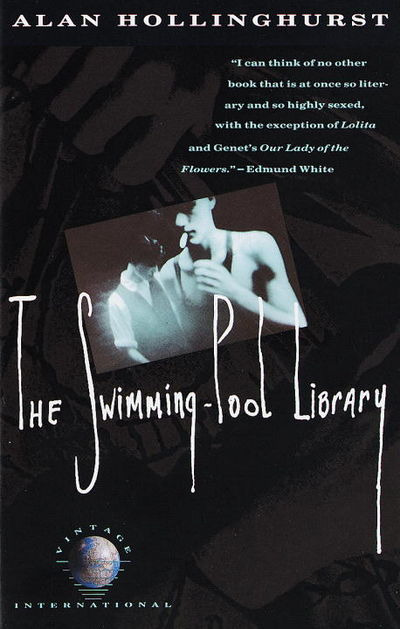

New profile pictures for Isaac and Charlie in season 3 - both photos from Paris

The Outsider by Albert Camus

The Swimming-Pool Library by Alan Hollinghurst

#isaacbookclub#heartstopper#isaac heartstopper#isaac henderson#charlie spring#heartstopper season 3#the outsider#albert camus#Alan Hollinghurst#the swimming pool library

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Updike vs. Gay Literature

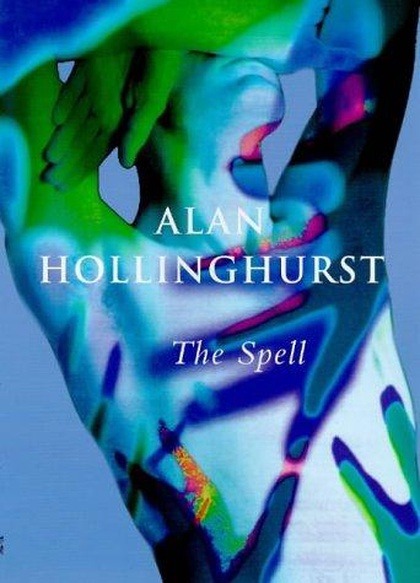

On May 23, 1999, John Updike published a review of The Spell in The New Yorker magazine. Written by Alan Hollinghurst, the novel is another of his tales of the gay underworld, an attribute that clearly displeased Updike:

The novels of the English writer Alan Hollinghurst take some getting used to; they are relentlessly gay in their personnel, and after a while you begin to long for the chirp and swing and civilizing animation of a female character. Save for the briefly and reluctantly glimpsed sister or mother, there are none. Boredom swoops in without hetero clutter to obstruct its advent. Novels about heterosexual partnering, however frivolous and reducible to increments of selfishness, social accident, foolish overestimations, and inflamed physical detail, do involve the perpetuation of the species and the ancient, sacralized structures of the family. Perhaps the male homosexual, uncushioned as he is by society's circumambient encouragements to breed, feels the lonely human condition with a special bleakness: he must take it straight. (Full review)

The backlash, as The New York Observer reported, was almost immediate:

“It really feels like an attack,” said Angels in America playwright Tony Kushner. Writer and activist Larry Kramer circulated an e-mail alert among gay writers on May 31, with certain of Mr. Updike’s lines highlighted. Novelist Sarah Schulman, who is a lesbian, said she wrote a letter to The New Yorker “the second I read the piece. It was so outrageous.” Craig Lucas, the writer of the movie Longtime Companion, also wrote a letter. “What he basically wanted to do is turn up his nose to distasteful sex,” he said. “This coming from the author of Couples! The idea that heterosexual sex is ‘sacralized,’ in his absurd phrase.” Mr. Kushner thought Mr. Updike knew what he was doing. “I have a suspicion that he thought he was being cute and naughty.” Mr. Kushner said Mr. Updike’s review “represents a kind of genteel tradition of disdain for homosexuals,” that has long been present at the magazine, going back to E.B. White and James Thurber. So far, none of the letters have appeared in the magazine; New Yorker editor David Remnick didn’t return calls for comment. A New Yorker spokesman said, “It’s our understanding that Hollinghurst was not displeased by the review.”

Asked about the controversy, Updike seemed to miss the point of the criticism:

He said he had never read Mr. Hollinghurst before, and that when he did, this was his reaction. “As with all books that you are reviewing, you try to give your impression of the atmosphere within the book, which seemed kind of gloomy and pointless to me,” he said. “So I’ll just have to withstand whatever letters come.” It’s not like he wanted to make generalizations about homosexuality. “I’d be happy not to discuss it,” he said. “Hollinghurst made it kind of tough. It makes it the unavoidable topic of discussion. It’s all about it. And for me to avoid his own emphasis would certainly be not doing my reviewer’s job.”

Colm Tóibín, another notable gay author, further bashed Updike’s views on homosexuality:

If you look at it carefully, that view of his will eventually eat into his reputation. Because his own elaborately confident and super-developed heterosexuality is actually an impediment to the proper writing and it eats at his sentences at times and it eats at his books… If you start reading Updike very carefully you start reading the astonishing boasting about sexual life which I found much more offensive than he does Hollinghurst’s book.

Years later, Hollinghurst himself spoke about the review:

Well, it was deplorable in various ways, but I also remember being very amused by it. There was this person who had gone to rather extraordinary lengths in his details of heterosexual sex and for whom the analysis of sexual behavior seemed to be so fundamental to his work as a novelist. But who was giving the impression in this review that everything he knew about homosexuality he gleaned from my novels, like he had never come across it in real life at all. I thought it was absolutely extraordinary, therefore so absurd, the old way he put it about the animating chirp of the female presence or something that he so missed in my books. It was terribly silly. It showed that he had chosen to emphasize his own failure with this large and interesting aspect of human behavior.

#john updike#alan hollinghurst#tony kushner#colm tóibín#literature#lit#gay literature#lgbt literature#lgbtq literature#history#gay history#lgbt history#lgbtq history#gay books#gay fiction#gay#lgbt#lgbtq#homophobia#books#bookblr#1990s

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

this tumblr post / Alan Hollinghurst, The Line of Beauty (2004) / Sammy Fain and Irving Kahal "I'll Be Seeing You" (1938) / Charles Dickens, Great Expectations (1861) / Julien Baker, "Heatwave" from Little Oblivion's (2021) / Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall (2009)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

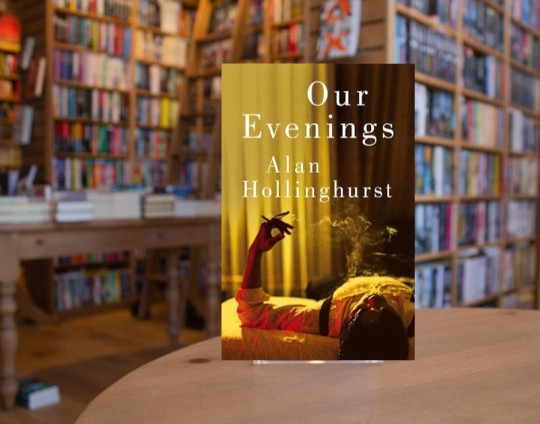

Our Evenings

A Novel

by Alan Hollinghurst

Book Summary

From the internationally acclaimed winner of the Booker Prize, a piercing novel of modern England through the lens of one man's acutely observed experiences.

Did I have a grievance? Most of us, without looking far, could find something that had harmed us, and oppressed us, and unfairly held us back. I tried not to dwell on it, thought it healthier not to, though I'd lived my short life so far in a chaos of privilege and prejudice. Dave Win, the son of a a Burmese man he's never met and a British dressmaker, is thirteen years old when he gets a scholarship to a top boarding school. With the doors of elite English society cracked open for him, heady new possibilities emerge, even as Dave is exposed to the envy and viciousness of his wealthy classmates. Alan Hollinghurst's new novel follows Dave from the 1960s on—through the possibilities that remained open for him, and others that proved to be illusory: as a working-class brown child in a decidedly white institution; a young man discovering queer culture and experiencing his first, formative love affairs; a talented but often overlooked actor, on the road with an experimental theater company; and an older Londoner whose late-in-life marriage fills his days with an unexpected sense of happiness and security. From "one of our most gifted writers" (The Boston Globe), Our Evenings sweeps readers from our past to our present through the beauty, pain, and joy of one deeply observed life.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our Evenings by Alan Hollinghurst

Gay life in England across the decades, from the 1960s to the pandemic, is captured with glowing intensity through an actor’s memories

In what has become one of the defining rhythms of contemporary literature, Alan Hollinghurst’s novels appear at spacious intervals of six or seven years, each a solid architectural structure holding within it fugitive emotions and pungent atmospheres, each managing restraint and amplitude in tandem, each to be read slowly for its craftsmanship and with a greedy plunge of the spoon into the deft social comedy, counterpointed settings, and irresistibly expressive detail.

The Swimming-Pool Library (1988) is firmly established as a modern classic, though The Line of Beauty, which won the Booker prize 20 years ago, is probably his best-known novel: a Jamesian study of sex, class and power in Thatcher’s Britain. Since then, The Stranger’s Child (2011) and The Sparsholt Affair (2017) have brought some of Hollinghurst’s most remarkable writing. Investigations of legacy and memory, they are structurally fascinating in their use of discontinuous stories side-stepping across generations. But some coherence ebbed away in the gaps, and the daringly blank Sparsholt lead characters, for whom other characters felt so much, exerted on me a less certain pull.

Our Evenings leaves no such doubts. This is the story of Dave Win as he tells it himself, in late middle age, recreating with glowing intensity a sequence of formative or quietly significant episodes across six decades, from the 1960s to the pandemic. He is a boy at school, discovering the possibilities of music and drama, finding his own powers, shaken by encounters with prejudice and aggression, filled with unspoken ecstasies as his sensual attraction to men grows. He is a young actor with a subversive touring company in the 1970s; he is a lover, finding joy with his partners. He is an only son to a single mother, their closeness outlasting all change.

Dave is a gay man of a generation reaching maturity soon after decriminalisation, seizing his freedoms wholeheartedly amid intolerance. He is also half Burmese, though he never met the father from whom he inherited his Asian looks, and Burma is an unknown page of the atlas to someone whose familiar terrain sits under the “B” of Berkshire. The novel tracks the currents of gay liberation and race relations, not to mention a modern history of theatre and the arts, but with never a moment’s schematic overview: all is lived and felt idiosyncratically.

Going back, remembering his schooldays “in the far‑off middle of the previous century”, Dave begins among the wind and earthworks of the Berkshire Downs. It’s exhilarating up here, but he’s caught in joyless play with another boy, Giles, who says he owns it all and who’s currently administering a Chinese burn. Dave is 13, a new pupil at Bampton, on a visit to the family who have funded his scholarship. Already he needs to hold off the obtuse, entitled son who will go on being a bully, become a Tory MP and exert his power as minister for Brexit.

Growing older in parallel through the span of the novel, these two contemporaries converge intermittently, their encounters too incidental for any politician’s memoir but charged by Hollinghurst with tragicomic political force. “Tone deaf and proud of it”, Giles attends a concert at Aldeburgh, though his schedule as arts minister won’t stretch to his hearing the whole performance. Dave is on stage as the reciter in Vaughan Williams’s Oxford Elegy, “a strange late piece” for speaker and chorus, when the noise of Giles’s departing helicopter screeches through the hall. Fighting back, filling his voice with colour as he raises the volume, Dave throws his words “like a javelin” to the back of the room.

Yet Dave retains a lifelong respect for Giles’s parents, his sponsors, who are lovers of the arts, people with money “who do nothing but good with it”. Their house, Woolpeck, is a place of beauty, encouragement and refuge, one that Dave revisits in memory on “little mental occasions” that no one else could guess. Going on like frame narratives around the edge, these long enmities and attachments are touchstones, as the decades pass: measures of how imaginative life might be fostered and how it might be squashed under the heel.

Moving spaciously within this frame, Hollinghurst unfolds a sequence of superbly realised scenes. A summer holiday on the Devon coast gleams with the beginnings of erotic excitement as the 14-year-old watches, mesmerised, “the shifting parade of known and unknown men”. It’s bravura writing, quietly done, generously varied in tone as the Fawlty Towers comedy of hotel routine accompanies the beautiful seriousness of desire. It’s collegially reminiscent of other literary comings-of-age and seaside longings, but compellingly fresh page by page; no Proust or Mann or Alain-Fournier would have sent Dave off to the gents behind the esplanade.

Time, passing as the sundial says, brings Oxford gardens at sunset, theatrical triumphs, the “brisker tempo” of twentysomething life in London, bright with sex and energy, a potently drawn relationship with Hector, the Black actor who leaves Dave behind, their unlived future together “missed, incalculably”.

At the tender core of this novel lies Dave’s portrait of his mother Avril, a dressmaker, a white woman bringing up a mixed-race boy alone in the market town of Foxleigh. Our Evenings becomes a tribute to her: an intensely private figure, acute in perception, loving her son with a mighty steadiness, and finding her life partner in well‑off, self-possessed local client Esme Croft.

We see what young Dave sees of the way these women establish a home together, neither advertising nor concealing their love, forming a family unit with utmost care, though one so radical that it cannot be named. We glimpse, too, what the older Dave wants to understand and to honour: Avril on her own terms, “tough, unconventional”, creative and courageous. Dave acknowledges forebears of many kinds, from the writers he learns by heart to the old thespian whose secluded baroque acres have hosted “liberties … excitements”. Yet his most enabling and affecting inheritance is here in Foxleigh, in the conifer-shaded garden where, on the evening of his coming out to them and innumerable evenings after, Avril and Esme expressed their loving support with a modest chink of glasses.

Our Evenings forms a deep pattern of connection with its predecessors, while being an entirely distinct and brimming whole. If it’s a long solo, it is a various and populated one. Happily echoing with voices, it stays clear of pastiche. Its chapters feel inhabitable: places to which you might return for sustenance on “little mental occasions” as yet unknown. Hollinghurst is precise about sentiment in ways that put loose sentimentality to shame. And he is above all an appreciator, taking pleasure in the inexhaustible particularity of what people do and make and see. That capacity for appreciation acquires new emotional and political meaning here, in the finest novel yet from one of the great writers of our time.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

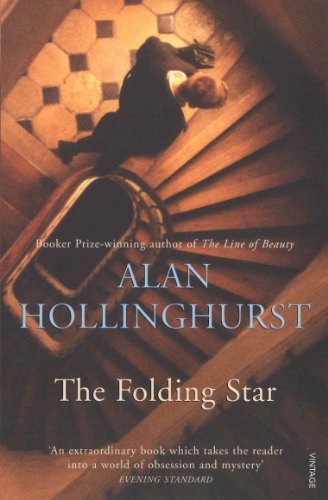

Group E Round 1

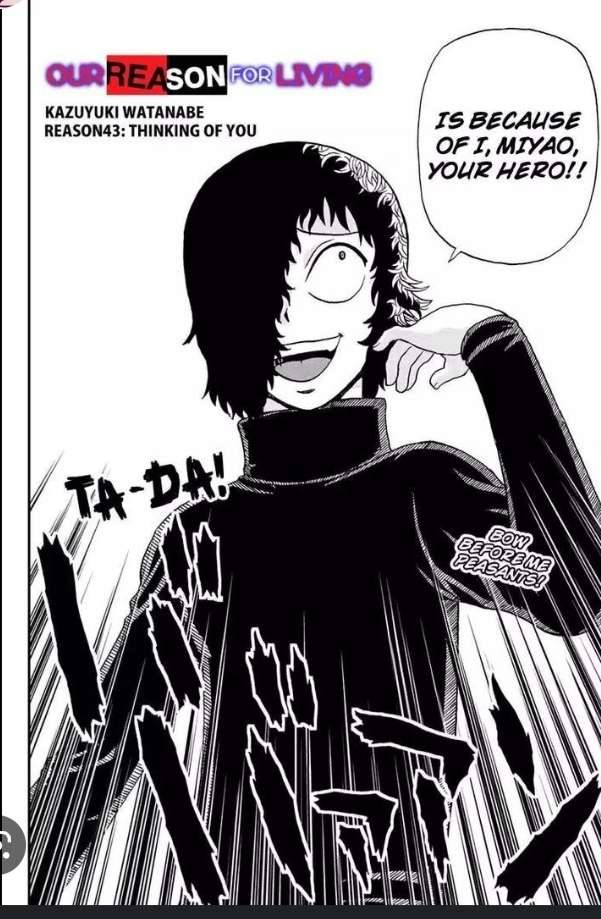

[image ID: the first image is of the book cover of The Folding Star by Alan Hollinghurst. it depicts a man in a suit on a spiral staircase. the stairs are wooden and each landing is black and white tile. it's unclear if he's ascending or descending, but the viewer is looking down at him. the second image is a manga panel of Reo Miyao, a boy with medium length black hair that covers his right eye. he's wearing a black turtleneck sweater, and he's saying: "Is because of I, Miyao, your hero!" outside of his speech bubble is the Japanese onomatopoeia for "Ta-dah" and the words: "Bow before me peasants!" end ID]

Edward Manners

the definition of Bad Gay Rep. he's an english tutor who becomes obsessed with his student and with a dutch symbolist painter whose past love affair parallels his own. this is general propaganda for this book READ IT NOW IT WILL MAKE U SEE GOD

Reo Miyao

Miyao is a noodly little chuuni boy who believes that his third eye is open to the supernatural, and thusly, that this makes him incredibly hot shit. However, when he and his classmates become trapped in their school and begin turning into puppets, he turns out to be a horrible little coward that will not hesitate to throw everyone under the bus and start whining when they get mad at him for it. He's largely a comic relief character and a lot of the time it might seem like he's just making things worse, but because of his interest in the occult, he's actually really genre savvy and ends up lasting a lot longer than a lot of the more "normal" characters one might expect in a manga like this. He sucks (affectionate), but he's surprisingly useful, and he's just really entertaining to watch.

#obscurecharactershowdown#group e round 1#obscure poll#edward manners#the folding star#alan hollinghurst#reo miyao#bokutachi no ikita riyuu#our reason for living

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 Days of Literary Pride 2023 - June 24

The Swimming-Pool Library - Alan Hollinghurst

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“As so often he had the feeling that an artistic disagreement, almost immaterial to the other person, was going to be the vehicle of something that mattered to him more than he could say.”

Alan Hollinghurst, The Line of Beauty

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Stranger's Child is so much fun and so good. I am so in love with the relationship between the story of the fictional queer poet and the very real history of poetry, queer studies and the very real recent historical developments. As I was reading it, I could kind of map the story out on real moments in queer literary history but at the same time it was still surprising and even kind of tense (the disappearing letters, the sudden reappearance of Hubert in the plot) and just deeply funny.

Especially the final section (closest to the present moment) contained so much that was just utterly familiar (the kind of snooty, literary, older gay men at the funeral.... I know some of these guys! The discussion about the ethics of outing someone conducted by people in the 21st century, but discussing a guy who is long dead and was outed at the height of the gay rights movement of the 20th c).

And the theme of memory!!! Everyone fighting over memories of Cecil (who remembers what, who gets to publish what memory?). And then the two women in his life get turned into memory keepers and they forget it all... his mother consults a medium and builds a marble effigy-neither of which reflects Cecil-as-he-really-was, and instead replace memory with fantasy. And Daphne can't remember it all because it's too long ago, but she creates memories out of stories, publishes them, and watches them become canon (so to speak). In the end, the only real memory comes from George, suffering from dementia, but the only one to have any kind of clear recollection....

0 notes

Text

Well this, towards the end of The Stranger’s Child, is unexpectedly devastating

0 notes

Text

Four Authors, Clockwise: Adrian McKinty, Alan Hollinghurst, Matt Haig, John Scalzi

0 notes

Text

Did I have a grievance? Most of us, without looking far, could find something that had harmed us, and oppressed us, and unfairly held us back. I tried not to dwell on it, thought it healthier not to, though I’d lived my short life so far in a chaos of privilege and prejudice.

Dave Win, the son of a Burmese man he’s never met and a British dressmaker, is thirteen years old when he gets a scholarship to a top boarding school. With the doors of elite English society cracked open for him, heady new possibilities emerge, even as Dave is exposed to the envy and viciousness of his wealthy classmates.

Alan Hollinghurst’s new novel follows Dave from the 1960s on—through the possibilities that remained open for him, and others that proved to be illusory: as a working-class brown child in a decidedly white institution; a young man discovering queer culture and experiencing his first, formative love affairs; a talented but often overlooked actor, on the road with an experimental theater company; and an older Londoner whose late-in-life marriage fills his days with an unexpected sense of happiness and security.

From “one of our most gifted writers” (The Boston Globe), Our Evenings sweeps readers from our past to our present through the beauty, pain, and joy of one deeply observed life.

#givebooks#bookswelove#aycarambabooks#shopsmall#alan hollinghurst#historical fiction#gay fiction#literary

1 note

·

View note

Text

“For a moment a London sensation, unnoticed and perpetual as the throb of traffic, came clear for him: of order and power, rhythmic and intricate, endlessly sure of obedience.”

0 notes