#after the antis being antis and manufacturing drama against the tv show

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Christopher Sean, who voices Nightwing on the Gotham Knights game (he also voiced Kaz on Star Wars Resistance and Asu in "The Village Bride" on SW Visions 1, btw) giving his support for Natalie Abrams, the WGA and for the Gotham Knights tv series.

#this is especially good to see#after the antis being antis and manufacturing drama against the tv show#Gotham Knights#Gotham Knights CW

70 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the OC ask: Aidan, Niner, Q, Ian, and Lauren, if you please. :)

Full Name: Ian Alan Grayson

Gender and Sexuality: Male, straight

Pronouns: He/him

Ethnicity/Species: White, human.

Birthplace and Birthdate: Undetermined date, somewhere in Tennessee.

Guilty Pleasures: Twinkies.

Phobias: He’s not afraid, exactly, but deep or fast-moving water sometimes sets off a “what if I tripped or something grabbed me” hypothetical scenario in his head. Swimming pools are fine, shallow streams are cool, lakes are usually okay, but oceans or any river that goes deeper than his waist can worry him.

What They Would Be Famous For: He hopes to be reasonably well-known as a musician someday. His inability to sing well is a bit of an obstacle, he’ll admit, but he’s got ideas for an instrumental guitar album of original songs he’s working on.

What They Would Be Arrested For: There’s been a couple times where he’s driven into a restricted area by accident. So far, it’s never been anywhere serious enough to get him in actual trouble, but it’s a concern Lauren has expressed on multiple occasions.

OC You Ship Them With: No one at present.

OC Most Likely to Murder Them: None of them, though Lauren has threatened to once or twice.

Favorite Movie/Book Genre: Ian likes really old classics and comic books -- big epics with larger-than-life characters. He also likes sci-fi or fantasy drama shows.

Least Favorite Movie/Book Cliche: It was all just a dream.

Talents and/or Powers: Music, particularly guitar. Getting lost. Annoying people who are rude or hurtful to others.

Why Someone Might Love Them: Easy-going, funny, a great listener, supportive but won’t take any bull, and willing to step in when someone needs help or someone else is being awful and needs to stop.

Why Someone Might Hate Them: If you deliberately hurt someone, especially one of Ian’s friends, he is very, very good at being obnoxious.

How They Change: Haven’t gotten there yet.

Why You Love Them: At its zenith, Ian’s story had maybe four paragraphs in it, but he has become such a distinctive character anyway.

Full Name: Lauren Eleanor Winston

Gender and Sexuality: Female, straight

Pronouns: She/her

Ethnicity/Species: White, human.

Birthplace and Birthdate: Undetermined, somewhere in Tennessee.

Guilty Pleasures: Cigarettes. It’s not precisely a pleasure, but every time she coughs or sees an anti-smoking ad, she definitely feels guilty.

Phobias: Chasing away everyone and ending up alone.

What They Would Be Famous For: Like Ian, she hopes to be a famous musician someday. She’d rather get into the classical music scene than bluegrass, but for now, it’s what she’s got.

What They Would Be Arrested For: Nothing serious. When she blows up at people, it cools down relatively quick, and she’s got enough of a grip on it that she would never hit someone or throw something dangerous at them.

OC You Ship Them With: No one at present.

OC Most Likely to Murder Them: She’s certainly aggravated more people than Ian has, but not to the point of murder.

Favorite Movie/Book Genre: She doesn’t read a lot, and when she does, it’s usually something she read and liked as a child, so technically Children’s.

Least Favorite Movie/Book Cliche: If you kill this one person, you are as bad as the mass-murdering villain/the villain says “You and I aren’t so different after all” and the hero admits they’re right

Talents and/or Powers: Music, particularly piano. Strategy games. She can also write nice poetry, but she doesn’t see the value in it yet.

Why Someone Might Love Them: Lauren has an instinctive sensitivity to justice, and will get just as angry on someone else’s behalf as her own if she believes an injustice has been committed. She doesn’t let disapproval or confrontation stop her.

Why Someone Might Hate Them: She is not an easy person to get along with, and can take things too personally.

How They Change: Not certain yet.

Why You Love Them: Same as Ian.

Full Name: Niner

Gender and Sexuality: Female, whatever.

Pronouns: She/her, “hey you”

Ethnicity/Species: Werecat

Birthplace and Birthdate: Birthdate, sometime in the summer, twenty-odd years ago. Birthplace … dunno. South of where she lives now. Probably east, too.

Guilty Pleasures: Hot, melted cheese. Batting around a ball of yarn. Snuggling up with Connie in cat-form (he’s so warm).

Phobias: Not a fan of being wet, or thunderstorms. On a deeper level, getting trapped or otherwise losing her independence.

What They Would Be Famous For: Nothing, really. She has no particular talents or skills that lend themselves to fame, and she would actively avoid fame if she did.

What They Would Be Arrested For: To be arrested, she would first have to be caught doing it, and then actually caught. Both of which would be very difficult to do.

OC You Ship Them With: No one at present

OC Most Likely to Murder Them: She and Aidan … have issues sometimes.

Favorite Movie/Book Genre: Not much of a reader or movie-watcher.

Least Favorite Movie/Book Cliche: The occasional TV show or movie has caught her interest for a little while, and none of them lose it faster than those where a character changes themselves for the approval of others. Even if the story ultimately has the moral that you shouldn’t do that, Niner will never know, because she won’t be watching anymore.

Talents and/or Powers: She can turn into a cat. As far as Niner is concerned, she doesn’t need anything else.

Why Someone Might Love Them: Niner has her own ideas of who she is, and takes zero input on who she is supposed to be.

Why Someone Might Hate Them: Niner has her own ideas of who she is, and takes zero input on who she is supposed to be.

How They Change: Not sure yet.

Why You Love Them: I don’t think any of my other OCs are quite so determinedly independent.

Full Name: Quincy Odell Free

Gender and Sexuality: Male, straight

Pronouns: He/him

Ethnicity/Species: White (English), human

Birthplace and Birthdate: Somewhere in England, July 3, 1989.

Guilty Pleasures: There aren’t many things he enjoys he would admit to -- less because they’re guilty pleasures he’s embarrassed about, and more because he is very cautious about opening up to people. That said, there is an animated kids show he really liked that he has episodes of saved on his computer that he will never, ever tell anyone about.

Phobias: Both afraid of being known and manipulated through it, and living his entire life without ever forming a real connection.

What They Would Be Famous For: If he wanted, he could suck up enough to his aunt and uncle to get named the heir to their hundreds of millions of dollars worth of real estate, businesses, corporations, foundations, etc.

What They Would Be Arrested For: Nothing terribly dramatic, and once it happened his aunt and uncle would most likely cover it up or sweep it under the rug as soon as possible.

OC You Ship Them With: No one at present

OC Most Likely to Murder Them: They would never dirty their hands by actually doing it themselves, but if Q was stupid enough to cross his aunt and uncle, there could definitely be an … accident … in his future.

Favorite Movie/Book Genre: Fantasy or adventure stories, the more exciting and epic the better, and with happy endings.

Least Favorite Movie/Book Cliche: Evil twins/evil mentors/bad guys disguised as good guys in general. He has nothing against morally gray characters or believable development from hero to villain or villain to hero, but most of the time the “this guy was evil all along!/the characters are fooled by the villain!” tropes feel like cheating for manufactured drama.

Talents and/or Powers: He’s picked up a lot of odd knowledge and abilities from his education and time spent with his family, most notably an excellent poker face, understanding of human body language, and generally able to persuade people to do what he wants them to -- not that he uses it often.

Why Someone Might Love Them: He’s got that “confused everyman in weird circumstances” thing going on that a lot of people seem to like. If you really got to know him, underneath his bland, indifferent attitude, he’s incredibly loyal.

Why Someone Might Hate Them: Q doesn’t really make enough of an impression on most people to be worth hating.

How They Change: Basically, learns that not everyone is like his aunt and uncle: learns to open up more, accept help, and connect emotionally with other people.

Why You Love Them: He’s got an interesting background that’s shaped him in interesting ways, and he manages to be an everyman compared to his roommates while being an outlier for the rest of humanity.

Thanks for asking!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

News and important updates on POS System Equipment & POS.

Scenes from The Searchers (1956), starring John Wayne and set during the Texas-Indian Wars. The film is considered one of the most influential Westerns ever made.

“It just so happens we be Texicans,” says Mrs. Jorgensen, an older woman wearing her blond hair in a tight bun, to rough-and-tumble cowboy Ethan Edwards in the 1956 film The Searchers. Mrs. Jorgensen, played by Olive Carey, and Edwards, played by John Wayne, sit on a porch facing the settling dusk sky, alone in a landscape that is empty as far as the eye can see: a sweeping desert vista painted with bright orange Technicolor. Set in 1868, the film lays out a particular telling of Texas history, one in which the land isn’t a fine or good place yet. But, with the help of white settlers willing to sacrifice everything, it’s a place where civilization will take root. Nearly 90 years after the events depicted in the film, audiences would come to theaters and celebrate those sacrifices.

“A Texican is nothing but a human man way out on a limb, this year and next. Maybe for 100 more. But I don’t think it’ll be forever,” Mrs. Jorgensen goes on. “Someday this country’s going to be a fine, good place to be. Maybe it needs our bones in the ground before that time can come.”

There’s a subtext in these lines that destabilizes the Western’s moral center, a politeness deployed by Jorgensen that keeps her from naming what the main characters in the film see as their real enemies: Indians.

In the film, the Comanche chief, Scar, has killed the Jorgensens’ son and Edwards’ family, and abducted his niece. Edwards and the rest of Company A of the Texas Rangers must find her. Their quest takes them across the most treacherous stretches of desert, a visually rich landscape that’s both glorious in its beauty and perilous given the presence of Comanche and other Indigenous people. In the world of the Western, brutality is banal, the dramatic landscape a backdrop for danger where innocent pioneers forge a civilization in the heart of darkness.

The themes of the Western are embodied by figures like Edwards: As a Texas Ranger, he represents the heroism of no-holds-barred policing that justifies conquest and colonization. While the real Texas Rangers’ history of extreme violence against communities of color is well-documented, in the film version, these frontier figures, like the Texas Rangers in The Searchers or in the long-running television show The Lone Ranger, have always been portrayed as sympathetic characters. Edwards is a cowboy with both a libertarian, “frontier justice” vigilante ethic and a badge that puts the law on his side, and stories in the Western are understood to be about the arc of justice: where the handsome, idealized male protagonist sets things right in a lawless, uncivilized land.

The Western has long been built on myths that both obscure and promote a history of racism, imperialism, toxic masculinity, and violent colonialism. For Westerns set in Texas, histories of slavery and dispossession are even more deeply buried. Yet the genre endures. Through period dramas and contemporary neo-Westerns, Hollywood continues to churn out films about the West. Even with contemporary pressures, the Western refuses to transform from a medium tied to profoundly conservative, nation-building narratives to one that’s truly capable of centering those long victimized and villainized: Indigenous, Latinx, Black, and women characters. Rooted in a country of contested visions, and a deep-seated tradition of denial, no film genre remains as quintessentially American, and Texan, as the Western, and none is quite so difficult to change.

*

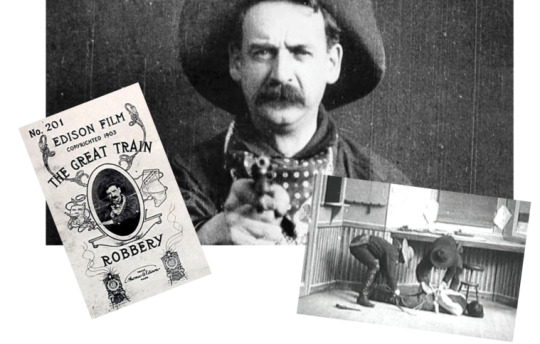

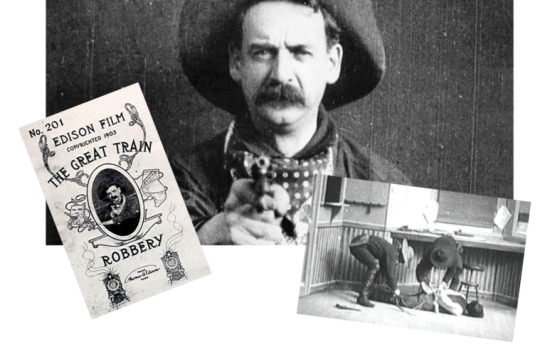

With origins in the dime and pulp novels of the late 19th century, the Western first took to the big screen in the silent film era. The Great Train Robbery, a 1903 short, was perhaps the genre’s first celluloid hit, but 1939’s Stagecoach, starring Wayne, ushered in a new era of critical attention, as well as huge commercial success. Chronicling the perilous journey of a group of strangers riding together through dangerous Apache territory in a horse-drawn carriage, Stagecoach is widely considered to be one of the greatest and most influential Westerns of all time. It propelled Wayne to stardom.

During the genre’s golden age of the 1950s, more Westerns were produced than films of any other genre. Later in the 1960s, the heroic cowboy character—like Edwards in The Searchers—grew more complex and morally ambiguous. Known as “revisionist Westerns,” the films of this era looked back at cinematic and character traditions with a more critical eye. For example, director Sam Peckinpah, known for The Wild Bunch (1969), interrogated corruption and violence in society, while subgenres like spaghetti Westerns, named because most were directed by Italians, eschewed classic conventions by playing up the dramatics through extra gunfighting and new musical styles and creating narratives outside of the historical context. Think Clint Eastwood’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966).

The Great Train Robbery (1903), a short silent film, was perhaps the first iconic Western.

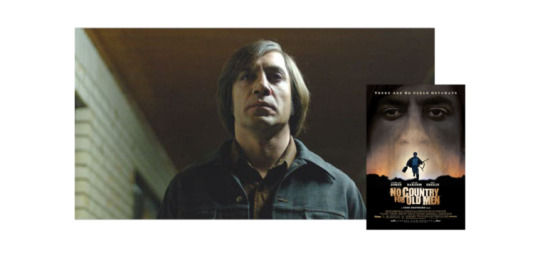

In the wake of the anti-war movement and the return of the last U.S. combat forces from Vietnam in 1973, Westerns began to decline, replaced by sci-fi action films like Star Wars (1977). But in the 1990s, they saw a bit of rebirth, with Kevin Costner’s revisionist Western epic Dances With Wolves (1990) and Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992) winning Best Picture at the Academy Awards. And today, directors like the Coen brothers (No Country for Old Men, True Grit) and Taylor Sheridan (Hell or High Water, Wind River, Sicario) are keeping the genre alive with neo-Westerns set in modern times.

Still, the Old West looms large, says cultural critic and historian Richard Slotkin. Today’s Western filmmakers know they are part of a tradition and take the task seriously, even the irreverent ones like Quentin Tarantino. Tarantino called Django Unchained (2012) a spaghetti Western and, at the same time, “a Southern.” Tarantino knows that the genre, like much of American film, is about violence, and specifically racialized violence: The film, set in Texas, Tennessee, and Mississippi, flips the script by putting the gun in the hand of a freed slave.

Slotkin has written a series of books that examine the myth of the frontier and says that stories set there are drawn from history, which gives them the authority of being history. “A myth is an imaginative way of playing with a problem and trying to figure out where you draw lines, and when it’s right to draw lines,” he says. But the way history is made into mythology is all about who’s telling the story.

Slotkin’s work purports that the logic of westward expansion is, when boiled down to its basic components, “regeneration through violence.” Put simply: Kill or die. The very premise of the settling of the West is genocide. Settler colonialism functions this way; the elimination of Native people is its foundation. It’s impossible to talk about the history of the American West and of Texas without talking about violent displacement and expropriation.

“The Western dug its own hole,” says Adam Piron, a film programmer at the Sundance Indigenous Institute and a member of the Kiowa and Mohawk tribes. In his view, the perspectives of Indigenous people will always be difficult to express through a form tied to the myth of the frontier. Indigenous filmmakers working in Hollywood who seek to dismantle these representations, Piron says, often end up “cleaning somebody else’s mess … And you spend a lot of time explaining yourself, justifying why you’re telling this story.”

While the Western presents a highly manufactured, racist, and imperialist version of U.S. history, in Texas, the myth of exceptionalism is particularly glorified, perpetuating the belief that Texas cowboys, settlers, and lawmen are more independent, macho, and free than anywhere else. Texas was an especially large slave state, yet African Americans almost never appear in Texas-based Westerns, a further denial of histories. In The Searchers, Edwards’ commitment to the white supremacist values of the South is even stronger than it is to the state of Texas, but we aren’t meant to linger on it. When asked to make an oath to the Texas Rangers, he replies: “I figure a man’s only good for one oath at a time. I took mine to the Confederate States of America.” The Civil War scarcely comes up again.

The Texas Ranger is a key figure in the universe of the Western, even if Ranger characters have fraught relationships to their jobs, and the Ranger’s proliferation as an icon serves the dominant Texas myth. More than 300 movies and television series have featured a Texas Ranger. Before Chuck Norris’ role in the TV series Walker, Texas Ranger (1993-2001), the most famous on-screen Ranger was the titular character of The Lone Ranger (1949-1957). Tonto, his Potawatomi sidekick, helps the Lone Ranger fight crime in early settled Texas.

Meanwhile, the Ranger’s job throughout Texas history has included acting as a slave catcher and executioner of Native Americans. The group’s reign of terror lasted well into the 20th century in Mexican American communities, with Rangers committing a number of lynchings and helping to dispossess Mexican landowners. Yet period dramas like The Highwaymen (2019), about the Texas Rangers who stopped Bonnie and Clyde, and this year’s ill-advised reboot of Walker, Texas Ranger on the CW continue to valorize the renowned law enforcement agency. There is no neo-Western that casts the Texas Ranger in a role that more closely resembles the organization’s true history: as a villain.

The Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men (2007) ushered in the era of neo-Westerns set in modern times.

Ushered in by No Country for Old Men (2007), also set in Texas, the era of neo-Westerns has delivered films that take place in a modern, overdeveloped, contested West. Screenwriter Taylor Sheridan’s projects attempt to address racialized issues around land and violence, but they sometimes fall into the same traps as older, revisionist Westerns—the non-white characters he seeks to uplift remain on the films’ peripheries. In Wind River (2017), the case of a young Indigenous woman who is raped and murdered is solved valiantly by action star Jeremy Renner and a young, white FBI agent played by Elizabeth Olsen. Sheridan’s attempt to call attention to the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women still renders Indigenous women almost entirely invisible behind the images of white saviors.

There are directors who are challenging the white male gaze of the West, such as Chloé Zhao, whose recent film Nomadland dominated the 2021 Academy Award nominations. In 2017, Zhao’s film The Rider centered on a Lakota cowboy, a work nested in a larger cultural movement in the late 2010s that highlighted the untold histories of Native cowboys, Black cowboys, and vaqueros, historically Mexican cowboys whose ranching practices are the foundation of the U.S. cowboy tradition. And Concrete Cowboy, directed by Ricky Staub and released on Netflix in April, depicts a Black urban horse riding club in Philadelphia. In taking back the mythology of the cowboy, a Texas centerpiece and symbol, perhaps a new subgenre of the Western is forming.

Despite new iterations, the Western has not been transformed. Still a profoundly patriotic genre, the Western is most often remembered for its classics, which helped fortify the historical narrative that regeneration through violence was necessary for the forging of a nation. In Texas, the claim made by Mrs. Jorgensen in The Searchers remains a deeply internalized one: The history of Texas is that of a land infused with danger, a land that required brave defenders, and a land whose future demanded death to prosper.

In Westerns set in the present day, it feels as if the Wild West has been settled but not tamed. Americans still haven’t learned how to live peacefully on the land, respect Indigenous people, or altogether break out of destructive patterns of domination. The genre isn’t where most people look for depictions of liberation and inclusion in Texas. Still, like Texas, the Western is a contested terrain with an unclear future. John Wayne’s old-fashioned values are just one way to be; the Western is just one way of telling our story.

This article was first provided on this site.

We hope you found the article above of help and/or of interest. Similar content can be found on our main site: southtxpointofsale.com Please let me have your feedback below in the comments section. Let us know what topics we should write about for you in the future.

youtube

#Point of Sale#harbortouch Lighthouse#harbortouch Pos#lightspeed Restaurant#point of sale#shopkeep Reviews#shopkeep Support#toast Point Of Sale#toast Pos Pricing#toast Pos Support#touchbistro Pos

0 notes

Text

Jan. 15, 2020: Columns

Magic in plain sight...

By KEN WELBORN

Record Publisher

During the first week of January of each year, the N.C. Association of Agricultural Fairs has a meeting in the Raleigh/Durham area to preview acts, hold seminars, and generally have a great time catching up with old friends and making new ones.

The Rotary Club of North Wilkesboro as you know, has put on the Wilkes Agricultural Fair for the past 40 or so years and the club's Fair Manager, Mike Staley, and me attend the event.

This year was a very special one for our trip as the Wilkes Agricultural Fair received a statewide award from the association in the area of Innovation for the clubs "Wednesday at the Fair." On this day, the club opens the fair at 10 a.m., and hosts over 500 Special Needs children, adults and their caregivers for their special day at the fair. At this past September’s fair, the Rotary Club served 600 meals at the Special Needs Children event. At last week’s meeting, club President Teresa Minton and Staley recognized Rotarian Jim Beckwith for his 27 years of managing the Children's Day event.

The fair convention is a truly special event—you can literally book a full three-ring circus for your kids birthday party if you've got the money. Both ends of the banquet hall had vendor booths and entertainment venue��displays for the attendees to browse and folks to speak with. At each meal, two or three acts would do a brief "showcase" to highlight their particular act or venue and I want to share a bit about one of them today.

This couple was new to the Fair Convention, a pair of Illusionists named Reed and Ashton Masterson. Their showcase event did several sleight of hand and disappearing tricks and was very well received by the audience of convention goers. But it was later in the day as I perused the various booths that I had my eyes opened.

There was a slow spell about mid-afternoon, and I was in the banquet/exhibit hall looking around. After stopping by Michael Garners Gold Medal Popcorn booth and getting a box o the best popcorn in the world--no exaggeration--I stopped to visit with the Mastersons. He was petting a dove he had literally took care of before she hatched--and yes, he could tell the girls from the boys. After a few minutes, Reed asked me if I would like to se a few tricks.

"Of course," I replied and he put the dove away and began to amaze me. He did things I simply couldn't believe--and I was standing less than a foot away from him--not 50 feet like at the lunchtime showcase they put on. But the one that I liked best was a card trick--sort of. Reed showed me a deck of cards, fanning them out. I figured they were all marked, but I was still interested. He then handed me a black Sharpie marking pen, like the one in the photo with this column.

I held it, turned it over and noted the logo on both sides of the barrel of the pen. He then started fanning the deck of cards and told me to say when to stop. I did and pulled a card out and held it next to my stomach with my hand covering it completely. He then held the Sharpie and asked me to give him the card being careful not to let him see which one it was.

I did and he placed the card on the barrel of the pen like the one in the photo and began to slide the card down the barrel of the pen. To my amazement, it did not read Sharpie any more, but instead clearly read Six of Clubs. He flipped the card over and, you're right, it was the Six of Clubs.

I will admit to being a simple guy, but I was less than a foot away from him. I touched the pen and it was dry--as though manufactured with the Six of Clubs on it. Blew me away.

I couldn't help but remember one of the late Bob Gresham's favorite expressions, "How doooo they do that?"

Immigration: Is the ‘Melting Pot’ separating?

By AMBASSADOR EARL COX and KATHLEEN COX

Special to The Record

Many reading this article will recall being taught to understand America as a “melting pot” – a blending of cultures, faiths, hopes and aspirations which, when fully combined, resulted in a delicious American pie where the sum total was more desirable than any of its individual parts. This was during a time when America was proudly defined as a “Christian” nation. However, faith is no longer a key component of America’s identity. So, what does it mean to be American? What defines America’s national soul? It may be possible to begin forming an answer by asking another question, “What does it mean to be Israeli?”

Since the beginning of time, Israel has had to fight just to exist. Many times throughout history the Jews were pushed to the precipice and on the brink of extinction. In AD 70, the armies of Rome destroyed the Temple of Jerusalem, seized the city and captured the entire nation. A small band of Jewish revolutionaries fled to Masada where they took their last stand. Other Jews were left to wander the earth settling in foreign lands and among foreign people. So, how did they manage to stay identifiably connected when separated geographically from their fellow kinsmen? It’s because they retained, whether naturally or supernaturally, a common thread - their Jewish faith and therefore their Jewish heritage and identity.

In 1948, Israel was reborn as a nation. Prior to and ever since, the Jews have been returning to their homeland in droves from every corner of the earth. Today, Israel is fighting hard for their right to exist as a Jewish state. Those Jews making Aliyah (immigrating) to Israel are from France, Germany, Ethiopia, Spain, Nigeria, Australia, Uganda, China, Japan, the Americas, Russia and just about every other place on the map. Yes, they are bringing with them their various cultural identities, but they are embracing and strengthening that which unites them as a nation – their Jewish faith and heritage. And, they are learning and adopting their ancient and once common language, Hebrew.

Ironically, the concept of America being a “melting pot” was created back in 1909 by a British Jew who wrote a play about a fictional Russian-Jewish immigrant intent on moving to the United States after his family died violently in an anti-Semitic riot in Russia. It dramatized how people around the world were aspiring to come to America because it was a place that offered promise and possibility. It was a place where diverse cultures blended in a joyful marriage forming a public national identity called “American.” But, what does this mean today?

At the turn of the century, the answer would have been similar to defining what it means to be Israeli. Americans were a people who culturally identified as believing in God, the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and who viewed the practice of Christianity as the hub of the wheel. After all, America’s first immigrants arrived on her shores seeking a place of refuge from religious persecution.

But, in today’s world, definitions are becoming blurred. America’s growing population is viewed in terms of multiculturalism void of any common core identity. People from a great number of ethnic and religious backgrounds have set up shop in the United States. The common threads which once held us together as a nation and formed the foundation upon which “united we stand,” are being stretched to the brink and are unraveling. We’ve diluted or deleted our core values in favor of “y’all come.”

America is plagued by great divisions among her people and leaders. Immigration is a very important issue requiring vision, foresight, maturity and agreement in order to formulate a solution. Yes, we welcome “the tired, the poor and the huddled masses yearning to be free,” but we must have clear guidelines and safeguards. Not everyone who comes to America has good intentions. Many even distain our Western culture and reject our traditional values. For instance, to whom do those immigrating pledge their allegiance? For Muslims, their first allegiance is to Allah. What does this mean should America be forced to fight against an Islamic foe? Will we be undermined from within much like the story of the Trojan horse? It is for this very reason that Israel will not compromise on her right to exist as a Jewish state nor give an inch on the Palestinian demand for the fictitious “right of return.” They know the dangers inherent in, “y’all come.” ”We the people” must agree on what it means to be an American and understand what we would be fighting for and against should the situation arise. There are already a few Trojan ponies feeding in U.S. government stables. When election time rolls around, cast your vote as though America’s very existence depended on it ... because it does.

Radio Talk

By CARL WHITE

Life in the Carolinas

It was a good week to talk with storytellers. We had an on-camera visit with Francene Marie Morris, better known as Francene Marie on the Beasley Broadcasting (formerly CBS Radio) stations in the Charlotte Region. With 23 years in the broadcast industry, she has clearly established herself as an extraordinaire storyteller for a broad and diverse audience.

The Francene Marie Show is on multiple stations and brings to life community stories that are important to almost everyone. People in the broadcast are unique, they see life a bit different than others do

When you spend much of your wakening hours developing stories around the lives of others, over time you see and hear just about everything. The good and the bad.

I have great admiration for radio people because they bring everything to life with words and sounds. TV people have the benefit of the visual. However, radio people are faced with the task of captivating listeners with their voice talents and the drama support of suitable music.

On-air talents often make their way out of the studio for community events. It’s all about connecting with listeners and further building the relationship. Sometimes it’s for a sponsor, and sometimes it’s for charity. No matter the reason entertainment is undoubtedly the objective.

Francene is not one to shy away from the public appearance. She has a solid foundation; her mother was an elementary school teacher and classical pianist. While Francene learned many things from her mother, the piano was not among them. However, she did learn to present herself properly.

This awareness served her well as she became a model and eventually discovered the broadcast world. Born in Illinois, later lived in Kansas City Missouri, where with much delight she discovered BBQ which she says, “must be ribs.” Francine ultimately moved to the Charlotte area where she found the radio business.

While she has not interviewed everyone in the Carolinas the numbers are in the thousands. It’s a Who’s Who list of community people. Her guest love being on her show and I am glad we showed up with cameras to share a bit of her story.

As it turns out our editor for the segment on Francene Marie also has an 18-year history in Radio Broadcast. Tim Vogel first set behind the big board at the age of 13. He would work part-time while in school and later full time.

Tim shared the story of meeting Charlie Daniels at a performance the station was sponsoring. That meeting would come in handy when Tim was at WHHO AM/FM in Hornell, NY. Tim pitched the station manager on an idea for a show. He was given the go ahead if he could sell the show to advertisers.

With this challenge, Tim went to work on producing his first show. He called Charlie Daniels and asked him to be in the show, he said yes. The studio call was made, the planned 30-minute call turned into 3 hours. Tim said they just talked and talked, it was when Charlie was working on the Blue Moon Album.

The recording was not a digital file like today, it was on Reel to Reel and editing was done with a razor blade and tape. A 30-minute show as produced, and the advertisers loved it. Tim was forever hooked on the creative process, and I am glad.

We have many friends in the Radio world, and it is a beautiful part of the Carolinas. There is something for everyone. While things have changed a great voice is hard to beat.

Thank You Francene for the great stories.

Signing off till next time.

Carl White is the Executive Producer and Host of the award-winning syndicated TV show Carl White’s Life In The Carolinas. The weekly show is now in its 10th year of syndication and can be seen in the Charlotte market on WJZY Fox 46 Saturday’s at noon and My40. The show also streams on Amazon Prime. For more information visit www.lifeinthecarolinas.com. You can email Carl at [email protected].

0 notes

Text

The TV Show Trials - Law & Order

Set and filmed in New York City, Law & Order follows a two-part approach: the first is the investigation of a crime (usually murder) and apprehension of a suspect by New York City Police Department detectives; the second is the prosecution of the defendant by the Manhattan District Attourney’s Office. Plots are often based on real cases that recently made headlines, although the motivation for the crime and perpetrator may be different.

The episodes that I chose for this month’s TV Show Trials are specifically ‘Ripped From The Headlines’ episodes from this list.

Reality Bites

The father of several adopted special needs children is accused of killing his wife over her reluctance to sign off on a reality show based on their family, and the subsequent trials threatens to turn into a media circus.

While it is not based on a specific crime and more so the reality stars/show Jon and Kate Plus Eight, this is an entertaining episode and was a great introduction to Law & Order and its characters. My only issue is that the ending line references a character that I didn’t know about from previous seasons, which made the ending more than a little confusing.

In Vino Veritas

A washed up, anti-Semitic actor is arrested with blood on his clothes. Detectives later discover that a Jewish television producer he has connection to has been murdered. But what role, if any, did he play in it?

The main character of this episode, Mitch Carroll is a stand-in for Mel Gibson who was arrested with a DUI and was also witnessed making anti-Semitic remarks. As for similarities to the real-life case, what has been previously mentioned is all there is. This episode features highly entertaining court procedures as a young boy confesses to killing a woman on his father’s behalf.

The Serpent’s Tooth

A businessman and his wife are killed. The couple’s two sons emerge as the most likely suspects, but detectives later find business ties to the Russian mob.

This episode leaves no ambiguity towards its connection to the Menendez brothers case, all the way down to one of the brothers calling 911 after ‘coming home from a night out’. It seems to be that the episodes with mob related plot lines are my least favourite; as a later episode will prove. This episode spends too much time investigating, for my taste, over showing the court proceedings, which are easily my favourite part.

Baby, It’s You

Baltimore Homicide detectives Munch and Falsone help Briscoe and Curtis with a murder investigation. However, the victim’s family attorney interferes with the investigation by leaking information and offering rewards.

Though it’s not clear by the synopsis, this episode is heavily influenced by the infamous JonBenet Ramsay case. While the real-life case has gone cold, with no conclusion as to who killed the young girl, this episode heavily insinuates that it was the father that killed his daughter. I really enjoyed this episode, especially the cameo from Richard Belzer as Detective Munch, who is easily one of my favourite character from Special Victims Unit.

Smoke

The child of a popular comic dies after he is reportedly thrown out of a window during a fire. However, the investigation also uncovers allegations that the comic molested an 11-year-old by years earlier.

This episode clearly references two cases, both surrounding Michael Jackson. The first is when he held his 9-month-old child over the edge of a balcony back in 2002, and the second being the multiple allegations of child grooming and sexual abuse against his name; both topics I won’t be expressing my opinions on here. My main issue with this episode is that, with both cases being covered, the episode changes course halfway through the episode and we aren’t provided with a conclusion to the first case.

Excalibur

While preparing a murder case, the DA’s office stumbles upon a potential scandal involving a prostitution business and the governor of New York, and it could have serious implications on Jack McCoy’s future as District Attorney.

My main issue with this episode, which is based on former New York Governor Eliot Spitzer, is that it’s very reliant on plot elements from previous episodes. This makes it hard to watch as a stand-alone due to my unfamiliarity with the parties in play. Other than that, it is a fairly average episode.

The Reaper’s Helper

A gay man with AIDS is accused of murdering another gay man. However, he claims that the victim also had AIDS, and that it was a mercy killing.

This episode brings up the interesting topic of assisted suicide in the medical industry as the episode is based on Dr Jack Kevorkian, who assisted the terminally ill in committing suicide by euthanasia. The acts of suicide are enlarged in terms of violence and drama, as the victims are shot in the head by the perpetrator. I didn’t really enjoy this episode, apart from the last five minutes.

Indifference

A child’s collapse in school from mortal injuries leads to an investigation that uncovers a family steeped in horrific abuse.

Uniquely, this episode has an end card and voiceover explaining the similarities between this episode and the Joel Steinberg/Hedda Nussbaum case; which it is based on. I am torn between this episode and another one further on, as to which one was my favourite out of all fifteen that I watched. This episode has extremely interesting and satisfying court proceedings, as well as some amazing synth cop music.

Remand

A convicted rapist in a high-profile trial from 30 years earlier receives a new trial because of legal technicalities. In addition, prosecutors must try to convict this time without a confession.

I would say that this episode is perfectly average in terms of quality. To be completely honest, I don’t remember much about this episode, and not in a good way, so I don’t have much to comment on.

Gunshow

After Jack is forced to settle with a man who committed a mass murder in Central Park, he decides to go after the gun manufacturer.

I’m not going to talk too much about gun control, nor the crime (real or fictionalised) due to the recent events in Christchurch. This is the other episode that ties for my favourite, it features entertaining investigation and court proceedings as well as genuine uncertainty about how the trail will end.

Fools For Love

A man is accused of raping and killing his girlfriend’s sister and another victim. Prosecutors make a deal with the girlfriend for her testimony against the accused, but they also suspect that she was a willing participant in the murders.

This episode is memorable to me mostly because it features a crossover with Special Victims Unit as we get to see Detectives Benson and Stabler assist in the investigation. This episode is a somewhat entertaining interpretation of the crimes of Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka or ‘The Ken and Barbie Killers’.

Born Again

A therapist is charged with murder after an 11-year-old girl dies during a “rebirthing” procedure.

This episode is clearly inspired by the horrific murder of Candace Newmaker, with a slight twist. Instead of it being somewhat of an accident on the mothers half, this episode paints the mother as the killer as she purposely causes her daughter to have an allergic reaction and suffocate. This episode even goes as far as to use direct quotes from the real-life crime in its script. It is an episode that had me hating both the mother and the therapist both in the fictionalised version and the real perpetrators of this crime.

Hubris

A charming conman acts as his own defence during his murder trial. During the trial, he deliberately tries to taint the jury by flirting with the forewoman.

This episode was pretty boring, as it consisted of a lot dialogue and speculation compared to solid evidence. I also don’t remember much about this episode other than thinking that the forewoman of the jury was an absolute idiot.

Myth of Fingerprints

A fingerprint analyst’s error put an innocent man in prison. Detectives discover that this may not have been the only error she has made in favour of prosecutors.

Similar to a previous episode I had watched, this episode derails from its original crime to focus on another but, unlike Smoke, this time it’s for the better. I didn’t really enjoy this episode, mainly because the crime didn’t appeal to me and I didn’t feel much sympathy for the criminals that were trying to gain justice due to lack of characterisation.

The Torrents of Greed

Stone makes a deal with a group of low-level mobsters when they offer to testify that a crime box murdered a missing union leader. However, the prosecution’s case unravels at trial, causing all parties involved to walk.

After a crime boss Frank Masucci’s murder case gets thrown out, Stone turns up the heat on the witnesses who played him in order to find charges against Masucci that will stick.

This is the only two-part episode that I watched over both series, and god was it boring. Subjectively, I think these episodes sucked, I couldn’t keep up with all the connections and thus the entire plot was lost on me.

Overall, Law and Order was a good experience to watch. But, if I had to pick one series or the other, I would pick Special Victims Unit. Am I likely to watch this again, probably not, but I wouldn’t turn it off if it was on.

0 notes

Text

Kamen Rider 45th Anniversary File:Drive

2014-2015:

Godzilla returns for his 60th birthday to theaters in an American film adaptation reboot simply titled Godzilla. Unlike last time America did this stunt, the film was well done and was a success.

Fans celebrate and sing with Moon Pride with Pretty Guardian Sailor Moon Crystal, a modern reboot that fully adapts the original manga for the franchise’s 20th anniversary.

Ultraman Ginga got a sequel season on TV, Ultraman Ginga S. Ultraman X would come the following year and Tsuburaya would sign an exclusive streaming and simulcast deal with the California-based internet streaming company Crunchyroll to broadcast entries of the Ultra Series legally on the web. (despite Chaiyo being jerks and trying to stop the deal with the fake “We own Ultraman” thing again)

Zing Zing, AMAZING! As long as there is love in the world, Cure Lovely is invincible! Pretty Cure celebrates its 10th Anniversary with HappinessCharge Precure, which introduces the concept of non-super mode form changing to the shoujo series thanks to Kamen Rider writers on the staff.

The Super Sentai Series hits a rough patch with ratings and toy sales as ToQger and Ninninger come and go. Super Sentai celebrates its 40th year of existence on April 5, 2015 and for the first time ever, a Power Rangers actor cameos in a Sentai!

Japan finishes switching to full digital HD TV broadcasting. Now we can see all the pretty lasers, sparks and explosions in glorious high definition!

Shout! Factory shocked Ranger Nation with a bombshell, Kyoryu Sentai Zyuranger was coming to DVD in the United States! Due to positive reception by fans and sales, the company would become the official distributor of Super Sentai DVDs in America!

Power Rangers celebrated 20 years of the franchise. The Mighty Morphin’ Red Ranger gets a spot in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade as a balloon!

Power Rangers Super Megaforce frustrates longtime fans of the series, with reviews ranging from “meh, it’s okay” to fan rage of the highest caliber for the mishandling of such a special occasion as the 20th anniversary. It really is a divisive season.

Kikaider Reboot attempts to relaunch Kikaider for its 40th anniversary, but later Shotaro’s son and president of Ishimori Pro Akira Onodera would put the Kikiader’s licensing to Japanese filmmakers under indefinite lockdown as he was unhappy with the direction the film took.

Cyborg 009 comes to America again with a graphic novel adaptation in 2013, intended to be the first of a series of graphic novels featuring Shotaro Ishinomori’s super heroes (”The Ishinomori Universe Books” as they were to be called). After a year of waiting for the next one, fans are disappointed to hear from F.J. DeSanto that the next set of books were put on hold and then cancelled indefinitely due to Ishimori Pro’s “cultural issues” with the project. Thus, the planned Skull Man and Kikaider novels are cancelled during their early draft phase.

The Garo Series turns 10 years old and a vast array of projects are announced and debut on TV, video and in theaters, increasing the franchise’s media output to levels never seen before.

The Patlabor franchise gets a series of live action films with Erina Mano (Kamen Rider Nadeshiko) as one of its stars.

When Drive was being planned; the producers had an idea of utilizing aspects of another cult favorite “Rider” show: Glen A. Larson’s cult 1980s TV show Knight Rider. In an interview, producer Takahito Omori even outright stated that Drive would be “Kamen Rider meets Knight Rider”.

Now imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but you need to be subdued to avoid lawsuits when you are dealing with TV. (Especially with tyrannical copyright strikedowners and suers like NBC Universal if you are simply doing a tribute). But the overall feeling is there in some regard: Rinna is Bonnie, we have a KARR expy on two accounts and a sentient A.I. in a car that accompanied a law enforcer. But that is where the some of the Knight similarities end as Drive tries to be its own thing, a quirky, sometimes goofy, sometimes serious show with sentient Hot Wheels cars, special tires that give the heroes super powers and a talking belt.

The planning involved Riku Sanjo, who fans remember from the beloved Kamen Rider W. He wanted a police procedural drama integrated into the action. Oddly enough, the original concept was to make the hero a former criminal and then revised into a crook turned cop! This idea was bounced around before the TV Asahi network executives got into a hissy fit about an anti-hero as a lead and said/demanded that the hero should be “pure”. So they decided to just make the show about cops with the main hero being an officer of the leu. (as Peter Sellers used to say).

A second concept idea was the use of games but the staff thought the age demographic they were aiming for was “too young for that”. This will still come... eventually in another Rider show years later.

Another aspect that chose the direction of the show was a more somber one, the choice of a car as the main Rider Machine. Ishinomori famously claimed in an SIC story that “cars didn’t work” for Kamen Rider the last time they tried it. But according to the Asahi Shimbun in 2014, with the dwindling population and low birth rate of Japan, motorcycles are becoming less and less common in number on Japan’s roads. No extra babies being born means less future rebellious youngsters and some of those who have bikes registered are getting older and greyer.

So the staff chose a car as 1: Cars are steadily beginning to rise in number on Japan’s roads and 2: small car toys like Hot Wheels are and always will be popular with the young male demographic. Plus the staff thought it would be “innovative” as unlike with Black RX, the car would be the main hero’s sole vehicle. Also helping the car motif was Carranger director Ryuta Tasaki being on the show as a consultant and episode director, who wanted to “break a few conceptions about Heisei Kamen Rider”.

So after the decision, the production crew took a used 1992 Honda NSX, got some custom seating, racing style safety belts and trim from TS Tech, took her to a body shop and went to work. Several months of hard labor and custom parts made in-house and spare/modified parts donated from Honda later.....

We got a souped-up custom super machine! Sure, Tridoron doesn’t have a style that is to everbody’s taste, but in the show it can fly like a certain Delorean, turbo boost, shoot lasers and can go a little over 340MPH and drive itself!

The cars and speed didn’t stop with the main hero, as we got a TRON-lined high tech Mercedes-Benz AMG GT (the first non-Japanese manufactured car in the Kamen Rider series) and a modified Mazda Miata with machine guns as villain cars for the movies.

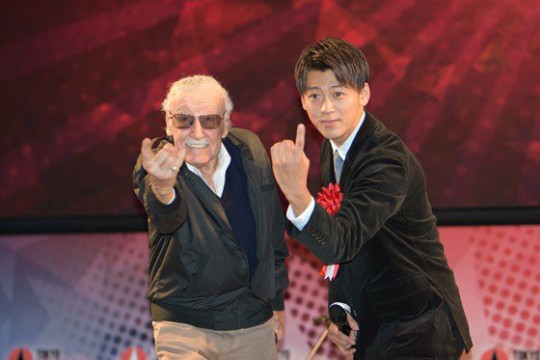

Another cool aspect of Drive is the indirect Marvel connection, the main lead actor Ryoma Takeuchi is a fan of Marvel Comics. This shows as his portrayal as Drive is a sometimes Spider-Man-esque snarky superhero. But Ryoma also studied hard to learn English really for one purpose: To meet Stan Lee and tell him how much he loved Marvel. A year after his show ended, he did!

(Yes, even in other superhero fandoms, Stan ”The Man” Lee will make that cameo! 94 and still awesome and kicking, God bless him!)

Word is Ryoma’s now trying to get into Hollywood to be a Marvel superhero on the American big screen or TV. If that doesn’t prove Ryoma is One of Us, what will? (Good luck Ryoma! We’ll be cheering for you and we hope your dream comes true!)

Chris Peppler, a Japanese-American radio DJ was chosen to be the other half of Kamen Rider Drive: the KITT-esqe Mr. Belt. Since he was fluent in both Japanese and English, it gave him room to play around as an actor and his performance even spawned a Rider meme or two.

But now, let’s START OUR ENGINES! Cuz’ ALL WE NEED IS DRIVE!

DRIVE! TYPE: 45 File!

The First Kamen Rider (Proto) Drive

Real Name: Roidmude Proto-Zero

“Those who are about to die do not need to know my name”

A scientist named Dr. Krim Steinbelt was working on a device called Core Driviars which he hoped could be used to benefit mankind.

His colleague Dr. Banno had borrowed his invention when his own research on advanced A.I. androids called Roidmudes hit a dead end. Krim wanted to help his friend and aided in the development of Banno’s research. But then Banno had other ideas and used the androids human mimicry ability to enact his revenge fantasies of destroying those who mocked or didn’t support his research without Krim’s knowledge. But Krim found out about Banno’s petty and sadistic behavior and ended their partnership.

Banno then intended to implant the negative emotions of humans into his creations so they would understand the concept of hate and violence and be used as his military force to conquer the world.

However, Banno’s plan seemingly went awry as the 108 Roidmudes he built gained sentience and rebelled against their cruel creator and like so many films and TV about AI, they decide we fleshy meatbags are not worth protecting or keeping around.

However, Krim had a contingency plan if Banno’s evil work bore fruit. After his home was attacked and he was killed by a Roidmude, a protocol was activated to download his consciousness into a belt-like device and he reactivated an early Roidmude that didn’t have Banno’s programming installed into him. The evil Roidmudes initiated a disaster later referred to as the Global Freeze, where a large quarter of the Earth was slowed down by the Heavy Acceleration phenomenon the Drivairs in the Roidmudes created. Many people were hurt or died and thousands of buildings were destroyed, but then a savior came in the form of a black Kamen Rider. The Rider drove away the evil forces but could not destroy the Cores that keep them alive. The Rider eventually fell in battle when one of the stronger Roidmudes defeated him and discarded a helpless Krim aside. Some say he is dead....but is he really?

The second and current Kamen Rider Drive (Officer Tomari circa 2015)

Real Name: Shinnosuke Tomari

When all the Global Freeze ruckus was about to go on, two police officers were in pursuit of a suspect of the terrorist cell Neo-Shade. When one of the suspects tried to ambush Officer Tomari’s partner Hayase by cornering him, Tomari panicked and pulled out his gun intending to disable the crook. But then the Global Freeze wave hit and slowed Officer Tomari down, causing his bullet to miss and hit a flammable generator near Hayase. The generator exploded and Hayase fell with steel pipes threatening to crush him after he fell. Tomari tried to save his partner but was slowed down again unable to reach him. Thankfully, due to the slowdown, Hayase was still alive after the pipes fell but was badly hurt. But being the cause of his best friend’s injuries haunted Officer Tomari and he became a broken man, unable to focus on work and losing all motivation.

He was transferred to a special investigations unit as Krim had a friend in the Police force who could pull the strings to find a candidate worthy of being the next Kamen Rider and formed the unit. Half a year later, Shinnosuke is still in that department but has a lax motivation to do anything at first, constantly being scolded for his slacking by his co-worker Kiriko. Upon hearing there may be a Heavy Acceleration case, he gets interested at first but is easily discouraged by his low self esteem. He keeps hearing a voice coming for the red car he drives telling him to not give up and offers him a chance to be a “warrior”. Shinnosuke is a bit weirded out by this but tells the voice he still refuses as he is a has-been. But the voice tells him he knows he has greater potential and then when Shinnouske finds where the voice is coming from, Krim attaches himself to Shinnouske which freaks him out. After investigating another attempted murder with Heavy Acceleration in the area, they find the suspect: Roidmude #029. Unable to save a bystander as even with the Shift Cars help, he cannot do much as he is ambushed by more Roidmudes.

Kiriko tells him he must use Krim and transform and the Shift Cars give him a brace and a red car to go with the belt. He uses it to become Kamen Rider Drive Type Speed. After a bit of a learning curve, Drive makes quick work of the Roidmudes using his new powers. (though at least one survived the attack via his Core escaping to antagonize the hero next episode)

When the day is saved, Kiriko shows him their base of operations under the Kuruma Driver's License Center: the Drive Pit. She tells Shinnosuke they must keep the base a secret from the Special Investigation Unit and the Tokyo Metropolitan Police. So Shinnosuke must investigate the cases of the Roidmudes to stop and eliminate them as the secret Kamen Rider of law enforcement and supported by his allies in the Special Investigations Unit. Many twists and tuns happen along the way, with new allies, new powers and new dangers and mysteries around every corner!

Gear:

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Core_Driviars

The Drive Driver aka “Mr. Belt” - Krim’s current form and Shinnosuke’s partner. Unlike KITT from Knight Rider whom partially inspired his character, Krim can leave the car and be mobile to help his partner whenever and wherever he is needed and is a vital part of the Drive System’s functions.

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Shift_Brace

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Shift_Cars

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Shift_Car_Holder

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Tridoron Its full “Format Number” is the Tridoron-3000.

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Tire_Specific_Items

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Handle-Ken

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Door-Ju

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Trailer-Hou

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Ride_Booster_Set - Go karts which combine with the Tridoron to change into hover conversion tech! Best of all, they were a free gift from Rinna, no $39,999.95 worth of body work needed!

Powers:

Super Speed, enhanced strength and reflexes, weapons proficiency, Immunity to singularity events such as Heavy Acceleration if Shift Cars are on his person or his Core Driviar in his Rider Suit is active.

The Shift Cars give a wide variety of powers:

Flame Generation and projectiles

Ninja based-powers such as cloning jitsu and throwing shuriken construct projectiles

Spike projectile shooting

Entrapment of an enemy via a cage.

Twin Shields, Playing card projectiles and smokescreen/Coin projectiles, the coin ones depend on Drive’s luck though.

Teleports a fraction of Drive’s Body to another area or creates portals.

Enhanced power and defense

Gives Drive analytical power, enhanced reflexes and the ability to multitask and detect enemies from behind him.

Enhanced Super Speed with rocket boosters and more power. Able to resist Super Heavy Acceleration.

Healing Factor, albeit a very painful one.

Self-repair to Drive’s armor

Nitro power boost to enhance speed

Hologram projections

A Drill that can pierce the Roidmudes!

Light projection to blind enemies

Grappling hook!

Spanner fist

chomping claws and elastic “tongue” on the claws.

freezing blast ability

Cement gun

Fire extinguisher and extendable robotic arm

Acme 10 ton weight and gravity distortions

lifting jack

Able to fuse the power of 3 Shift cars into one super ability or all of them. Able to resist all forms of Heavy Acceleration. Energy Shield

Also, like Fourze, Wizard and Deacde, Drive’s powers are compatible with Super Sentai powers as he can use a Ninninger Nin Shuriken to turn Tridoron into a Zord. Though that was just a one-off thing.

Signature Finishers:

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Full_Throttle_(finisher)

Weaknesses:

A big one is Shinnosuke needs Mr. Belt to transform and given that he is an A.I., that means he is vulnerable to hacking or tampering to make the once friendly scientist into a violent killing machine via evil programming and use Drive’s body in Type Tridoron to hurt others.

The Shift Cars can be captured, immobilized or damaged. In some cases, the villains could even control them and use them against Drive.

Shinnosuke can be killed, even when in Rider form as the battle with Freeze seemingly showed. Meaning a more powerful opponent with devastating firepower can kill Drive if enough effort is put in or he somehow has no access to his defensive abilities. Despite being protected from singularities, he is not entirely immune to distortions in time and can be affected by them. (Though this was a bit inconsistent as he somehow remembered being a hero later when this happened.)

Stronger Heavy Acceleration waves can severely damage Drive or slow him down. But modifications and successions to his base Core Driviar system thanks to Dr. Hendrickson and Rinna in newer forms slowly negates this weakness to the point it is not an issue as he can maintain his movement.

Enemies:

Roidmudes:

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Category%3ARoidmudes

Androids created by Tenjiro Banno and Krim Steinbelt who possess sapient, advanced level intelligence, human mimicry abilities and a wide variety of powers as well as the ability to generate Heavy Acceleration.

In a nice nod to the original Kamen Rider, the low level types of Roidmudes are divided into three of the classic Rider mythology monsters: Bat Type, Spider Type and Cobra Type.

Roidmudes are capable of evolving to even stronger forms: Advanced, Giant, and the rare Super Evolved State, which grant Roidmudes new abilities and greater power and stronger Heavy Acceleration effects. Their goal is to create a utopia for their race by attaining The Promised Number of evolution.

Among the Advanced Roidmudes are several generals/leaders:

Heart

Brain

Medic

Freeze

And their enforcer/reaper: the mysterious Mashin Chaser.

And secretly pulling the strings of these events from the shadows is.....

Tenjuro Banno/Gold Drive:

(The KARR to Krim’s KITT)

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Tenjuro_Banno

Tenjuro Banno was a horrible and insane human being and even worse as an A.I.. An abusive, petty, cold, manipulative, ego-driven, sadistic and narcissistic black soul who believed the world owed him tribute to his “genius”. Seeing those that help him as nothing but pawns, even his own family as his two kids need a therapist after all the stuff he pulled. He is the cause of the first Global Freeze as a “ test experiment” and planned everything, as the rebellion of the Roidmudes was no accident but planned by him.

Like Krim, he uploaded his consciousness into an A.I. after being killed and slowly let his schemes come to fruition, even faking helping and reforming when reunited with his son and Krim to steal more tech Team Drive used and render it useless against him. He even managed to kill a Kamen Rider fans came to like over the course of the series. (I won’t say who though.)

He truly was a villain fans loved to hate for how dirty he played and demented he was, helped by the fact he was played by voice actor Masakazu Morita whom anime fans know can play crazy in a way that gives you shivers. He also was formidable as an evil Kamen Rider as he could pull off a wide array of powers, including swiping the weapons of the heroes away from them via teleport!

Neo-Shade:

http://kamenrider.wikia.com/wiki/Neo-Shade

A Terrorist group that Shinnouske was trying to track down before the series, they resurfaced in the final episode and were dissolved as their leader was captured. No seeming relation to the real Shade from Kamen Rider G other than its name.

Remember, the world has a drive that goes faster than ever, but as long as you yourself have a drive in life, you can be in Top Gear and go along for the Ride!

Shinnosuke Tomari: A Kamen Rider’s flight into a dangerous world ...the world.... of the Drive Rider. *1980s synth music*

#kamen rider#45th anniversary#kamen rider drive#mr. belt#knight rider#cars#motorcycles#cops#android#kamen rider mach#kiriko shijima#tire koukan#chris peppler#top gear#like a spinning wheel#mashin chaser#roidmudes#stan lee

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

News and important updates on POS System Equipment & POS.

Scenes from The Searchers (1956), starring John Wayne and set during the Texas-Indian Wars. The film is considered one of the most influential Westerns ever made.

“It just so happens we be Texicans,” says Mrs. Jorgensen, an older woman wearing her blond hair in a tight bun, to rough-and-tumble cowboy Ethan Edwards in the 1956 film The Searchers. Mrs. Jorgensen, played by Olive Carey, and Edwards, played by John Wayne, sit on a porch facing the settling dusk sky, alone in a landscape that is empty as far as the eye can see: a sweeping desert vista painted with bright orange Technicolor. Set in 1868, the film lays out a particular telling of Texas history, one in which the land isn’t a fine or good place yet. But, with the help of white settlers willing to sacrifice everything, it’s a place where civilization will take root. Nearly 90 years after the events depicted in the film, audiences would come to theaters and celebrate those sacrifices.

“A Texican is nothing but a human man way out on a limb, this year and next. Maybe for 100 more. But I don’t think it’ll be forever,” Mrs. Jorgensen goes on. “Someday this country’s going to be a fine, good place to be. Maybe it needs our bones in the ground before that time can come.”

There’s a subtext in these lines that destabilizes the Western’s moral center, a politeness deployed by Jorgensen that keeps her from naming what the main characters in the film see as their real enemies: Indians.

In the film, the Comanche chief, Scar, has killed the Jorgensens’ son and Edwards’ family, and abducted his niece. Edwards and the rest of Company A of the Texas Rangers must find her. Their quest takes them across the most treacherous stretches of desert, a visually rich landscape that’s both glorious in its beauty and perilous given the presence of Comanche and other Indigenous people. In the world of the Western, brutality is banal, the dramatic landscape a backdrop for danger where innocent pioneers forge a civilization in the heart of darkness.

The themes of the Western are embodied by figures like Edwards: As a Texas Ranger, he represents the heroism of no-holds-barred policing that justifies conquest and colonization. While the real Texas Rangers’ history of extreme violence against communities of color is well-documented, in the film version, these frontier figures, like the Texas Rangers in The Searchers or in the long-running television show The Lone Ranger, have always been portrayed as sympathetic characters. Edwards is a cowboy with both a libertarian, “frontier justice” vigilante ethic and a badge that puts the law on his side, and stories in the Western are understood to be about the arc of justice: where the handsome, idealized male protagonist sets things right in a lawless, uncivilized land.

The Western has long been built on myths that both obscure and promote a history of racism, imperialism, toxic masculinity, and violent colonialism. For Westerns set in Texas, histories of slavery and dispossession are even more deeply buried. Yet the genre endures. Through period dramas and contemporary neo-Westerns, Hollywood continues to churn out films about the West. Even with contemporary pressures, the Western refuses to transform from a medium tied to profoundly conservative, nation-building narratives to one that’s truly capable of centering those long victimized and villainized: Indigenous, Latinx, Black, and women characters. Rooted in a country of contested visions, and a deep-seated tradition of denial, no film genre remains as quintessentially American, and Texan, as the Western, and none is quite so difficult to change.

*

With origins in the dime and pulp novels of the late 19th century, the Western first took to the big screen in the silent film era. The Great Train Robbery, a 1903 short, was perhaps the genre’s first celluloid hit, but 1939’s Stagecoach, starring Wayne, ushered in a new era of critical attention, as well as huge commercial success. Chronicling the perilous journey of a group of strangers riding together through dangerous Apache territory in a horse-drawn carriage, Stagecoach is widely considered to be one of the greatest and most influential Westerns of all time. It propelled Wayne to stardom.

During the genre’s golden age of the 1950s, more Westerns were produced than films of any other genre. Later in the 1960s, the heroic cowboy character—like Edwards in The Searchers—grew more complex and morally ambiguous. Known as “revisionist Westerns,” the films of this era looked back at cinematic and character traditions with a more critical eye. For example, director Sam Peckinpah, known for The Wild Bunch (1969), interrogated corruption and violence in society, while subgenres like spaghetti Westerns, named because most were directed by Italians, eschewed classic conventions by playing up the dramatics through extra gunfighting and new musical styles and creating narratives outside of the historical context. Think Clint Eastwood’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966).

The Great Train Robbery (1903), a short silent film, was perhaps the first iconic Western.

In the wake of the anti-war movement and the return of the last U.S. combat forces from Vietnam in 1973, Westerns began to decline, replaced by sci-fi action films like Star Wars (1977). But in the 1990s, they saw a bit of rebirth, with Kevin Costner’s revisionist Western epic Dances With Wolves (1990) and Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992) winning Best Picture at the Academy Awards. And today, directors like the Coen brothers (No Country for Old Men, True Grit) and Taylor Sheridan (Hell or High Water, Wind River, Sicario) are keeping the genre alive with neo-Westerns set in modern times.

Still, the Old West looms large, says cultural critic and historian Richard Slotkin. Today’s Western filmmakers know they are part of a tradition and take the task seriously, even the irreverent ones like Quentin Tarantino. Tarantino called Django Unchained (2012) a spaghetti Western and, at the same time, “a Southern.” Tarantino knows that the genre, like much of American film, is about violence, and specifically racialized violence: The film, set in Texas, Tennessee, and Mississippi, flips the script by putting the gun in the hand of a freed slave.

Slotkin has written a series of books that examine the myth of the frontier and says that stories set there are drawn from history, which gives them the authority of being history. “A myth is an imaginative way of playing with a problem and trying to figure out where you draw lines, and when it’s right to draw lines,” he says. But the way history is made into mythology is all about who’s telling the story.

Slotkin’s work purports that the logic of westward expansion is, when boiled down to its basic components, “regeneration through violence.” Put simply: Kill or die. The very premise of the settling of the West is genocide. Settler colonialism functions this way; the elimination of Native people is its foundation. It’s impossible to talk about the history of the American West and of Texas without talking about violent displacement and expropriation.

“The Western dug its own hole,” says Adam Piron, a film programmer at the Sundance Indigenous Institute and a member of the Kiowa and Mohawk tribes. In his view, the perspectives of Indigenous people will always be difficult to express through a form tied to the myth of the frontier. Indigenous filmmakers working in Hollywood who seek to dismantle these representations, Piron says, often end up “cleaning somebody else’s mess … And you spend a lot of time explaining yourself, justifying why you’re telling this story.”

While the Western presents a highly manufactured, racist, and imperialist version of U.S. history, in Texas, the myth of exceptionalism is particularly glorified, perpetuating the belief that Texas cowboys, settlers, and lawmen are more independent, macho, and free than anywhere else. Texas was an especially large slave state, yet African Americans almost never appear in Texas-based Westerns, a further denial of histories. In The Searchers, Edwards’ commitment to the white supremacist values of the South is even stronger than it is to the state of Texas, but we aren’t meant to linger on it. When asked to make an oath to the Texas Rangers, he replies: “I figure a man’s only good for one oath at a time. I took mine to the Confederate States of America.” The Civil War scarcely comes up again.

The Texas Ranger is a key figure in the universe of the Western, even if Ranger characters have fraught relationships to their jobs, and the Ranger’s proliferation as an icon serves the dominant Texas myth. More than 300 movies and television series have featured a Texas Ranger. Before Chuck Norris’ role in the TV series Walker, Texas Ranger (1993-2001), the most famous on-screen Ranger was the titular character of The Lone Ranger (1949-1957). Tonto, his Potawatomi sidekick, helps the Lone Ranger fight crime in early settled Texas.

Meanwhile, the Ranger’s job throughout Texas history has included acting as a slave catcher and executioner of Native Americans. The group’s reign of terror lasted well into the 20th century in Mexican American communities, with Rangers committing a number of lynchings and helping to dispossess Mexican landowners. Yet period dramas like The Highwaymen (2019), about the Texas Rangers who stopped Bonnie and Clyde, and this year’s ill-advised reboot of Walker, Texas Ranger on the CW continue to valorize the renowned law enforcement agency. There is no neo-Western that casts the Texas Ranger in a role that more closely resembles the organization’s true history: as a villain.

The Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men (2007) ushered in the era of neo-Westerns set in modern times.

Ushered in by No Country for Old Men (2007), also set in Texas, the era of neo-Westerns has delivered films that take place in a modern, overdeveloped, contested West. Screenwriter Taylor Sheridan’s projects attempt to address racialized issues around land and violence, but they sometimes fall into the same traps as older, revisionist Westerns—the non-white characters he seeks to uplift remain on the films’ peripheries. In Wind River (2017), the case of a young Indigenous woman who is raped and murdered is solved valiantly by action star Jeremy Renner and a young, white FBI agent played by Elizabeth Olsen. Sheridan’s attempt to call attention to the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women still renders Indigenous women almost entirely invisible behind the images of white saviors.

There are directors who are challenging the white male gaze of the West, such as Chloé Zhao, whose recent film Nomadland dominated the 2021 Academy Award nominations. In 2017, Zhao’s film The Rider centered on a Lakota cowboy, a work nested in a larger cultural movement in the late 2010s that highlighted the untold histories of Native cowboys, Black cowboys, and vaqueros, historically Mexican cowboys whose ranching practices are the foundation of the U.S. cowboy tradition. And Concrete Cowboy, directed by Ricky Staub and released on Netflix in April, depicts a Black urban horse riding club in Philadelphia. In taking back the mythology of the cowboy, a Texas centerpiece and symbol, perhaps a new subgenre of the Western is forming.

Despite new iterations, the Western has not been transformed. Still a profoundly patriotic genre, the Western is most often remembered for its classics, which helped fortify the historical narrative that regeneration through violence was necessary for the forging of a nation. In Texas, the claim made by Mrs. Jorgensen in The Searchers remains a deeply internalized one: The history of Texas is that of a land infused with danger, a land that required brave defenders, and a land whose future demanded death to prosper.

In Westerns set in the present day, it feels as if the Wild West has been settled but not tamed. Americans still haven’t learned how to live peacefully on the land, respect Indigenous people, or altogether break out of destructive patterns of domination. The genre isn’t where most people look for depictions of liberation and inclusion in Texas. Still, like Texas, the Western is a contested terrain with an unclear future. John Wayne’s old-fashioned values are just one way to be; the Western is just one way of telling our story.

This article was first provided on this site.

We hope you found the article above of help and/or of interest. Similar content can be found on our main site: southtxpointofsale.com Please let me have your feedback below in the comments section. Let us know what topics we should write about for you in the future.

youtube

#Point of Sale#harbortouch Lighthouse#harbortouch Pos#lightspeed Restaurant#point of sale#shopkeep Reviews#shopkeep Support#toast Point Of Sale#toast Pos Pricing#toast Pos Support#touchbistro Pos

1 note

·

View note

Text

News and important updates on POS System Equipment & POS.

Scenes from The Searchers (1956), starring John Wayne and set during the Texas-Indian Wars. The film is considered one of the most influential Westerns ever made.