#accipitrimorphae

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Part 2: 2020–2024 Update

WARNING: Spoilers ahead!

If you’ve reached the time skip, you know Oikawa plays for UPCN, an Argentine volleyball club that takes part in Liga Argentina de Voleibol—Serie A1, the top level of the Argentine men's volleyball league system. (And, as is revealed later on, he eventually plays on the Argentina National team as the starting setter.) UPCN is nicknamed Los Cóndores (‘The Condors’), and their official art includes a condor:

Image via UPCN’s Facebook account

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

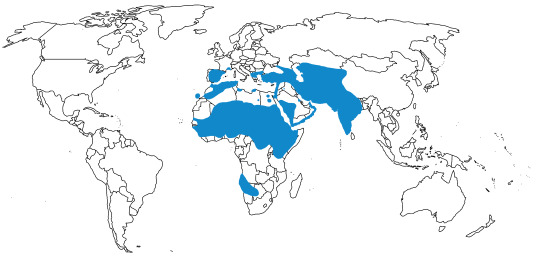

More specifically, the bird here is the Andean Condor, a species of American Vulture (Cathartidae) native to the Andes and Santa Marta mountains, as well as adjacent Pacific coasts along western South America; their range also includes Argentina, where they are found throughout the western portion of the country down to the Tierra del Fuego. This species is also known as Kuntur, Mallku, Mañke, Rey de los Andes (King of the Andes), Rey de los cielos (King of the Skies), and just Cóndor. The symbolism of Oikawa as a condor is HUGE, as it heavily ties back into his role as a royal figure on the court. Iwaizumi is also likely involved here, considering his relation to death.

“Andean Condor (Vultur gryphus) at Cruz del Cóndor in Colca Canyon, Colca Valley, Peru.” (Source)

An adult male Andean Condor in flight at Colca Canyon, Peru.

Credit: Colegota

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Andean Condor is the largest living bird of prey and land bird, with a maximum wingspan of nearly 11 ft (3.3 m or 335 cm), a length (tail tip to beak tip, sorta similar to height) of up to 4 ft 3 in (1.3 m or 130 cm), and a maximum weight of around 15 kg (33 lbs). In fact, by a combined measurement of average weight and wingspan, this is the largest extant flying bird! The Andean Condor is also one of the highest-flying birds recorded (max. 6,500 m (24,000 ft)), as well as one of the longest-living birds, with a lifespan of around 50–60 years in the wild and over 70 years in captivity.

To understand how we define and identify birds of prey/raptors, refer to this article.

We’ll return to the Andean Condor, but first, let’s go over vultures as a whole.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Now, most people reading this probably know the name ‘vulture,’ and are likely aware that a vulture is a type of meat-eating bird. Many may recall some image of a hunched silhouette with a long neck, a bald head, and a hooked beak. There may even be an initial “Wait, what?” in response to almost any mention of vultures outside of throwing their name around as an insult or an ominous metaphor, especially for readers from more western regions. Even so much as talking about vultures as actual living beings, and especially talking about their ecological significance and attributes, seems to evoke an uneasiness in many people.

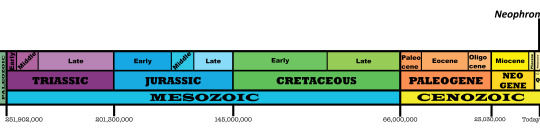

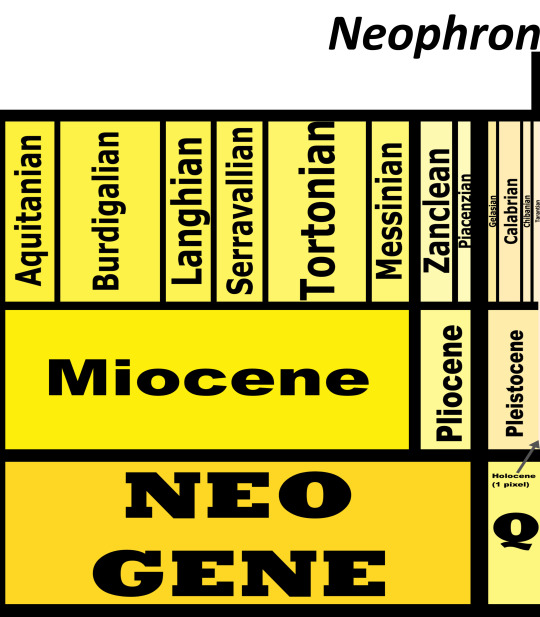

In truth, vultures are nothing like the archetype we’ve created for them, with the exception of their being scavengers and highly social. This stereotypical idea of the sinister and greedy ‘vulture’—this archetype we like to animate in children’s cartoons and accuse politicians, businessmen, and journalists of being—is nothing but just a ‘vulture’ in name, and a human in nearly everything else. It is merely an anthropomorphic amalgamation of misinformation and myths about vultures, a figure framed through our own blatant anthropocentrism (and speciesism—and I don’t use that word very often, so that really says something). When I talk about vultures in this analysis, I mean vultures, the true namesakes of the word, the birds who have been on this earth for several epochs, the beings who were cleaning up carcasses long before our earliest hominid ancestors ever existed.

To get a better understanding of what exactly a vulture is (i.e., how we define one), refer to this document.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

[NOTE, for anyone who thinks condors and vultures in general ‘look like dinosaurs,’ and is unaware of this: Vultures—like all birds—literally are dinosaurs! Not just descended from, are. Birds (Class Aves or clade Avialae, depending on the biologist) make up a subset of the clade Dinosauria, and are specifically defined as feathered, avialan, paravian, maniraptoran, theropod dinosaurs. Overall, birds constitute the only living dinosaurs today. This isn’t just speculation, this is information based around scientific facts which have so much empirical evidence to back them up that you could create a series of textbooks with just the evidence alone.

Karasuno’s mascot is a literal dinosaur, and a smart one, at that. Fukurodani’s mascot is a big-eyed dinosaur with astounding camouflage skills. Shiratorizawa and Kamomedai’s mascots? Water dinos! Ushijima’s animal symbol? Predatory water dino! (I’m pretty sure Ushijima is a species of sea/fish eagle.) UPCN? A big ol’ soaring dino!]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Now, back to our favorite corpse-eaters.

Because there is a lot of misinformation out there about vultures, I’ll cover some basic info and cases of fact vs. fiction. Vultures are obligate scavengers, meaning they rely entirely or near entirely on carrion as a food resource; they are specialist scavengers/carrion specialists, and therefore hypercarnivores or obligate carnivores (though some species have more varied and/or even vegetarian diets). In fact, vultures are the only obligate scavengers of all extant terrestrial vertebrates, which means they are so specialized that no other living terrestrial vertebrates can fill a vulture’s ecological role as efficiently or effectively as a vulture can. Thus vultures are what we know as keystone species, as their presence is key to the structure and health of their ecosystems and the overall environment.

The following are only a few of the main ecological roles vultures play: (1) Contributing to the carbon cycle by recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem; (2) Preventing pollution by keeping body fluids of carcasses from seeping into waterways (including drinking water); (3) Likely helping regulate—or prevent—the spread of diseases and viruses by acting as dead-ends for most pathogenic bacteria in carcasses (thanks to their harsh stomach acids, digestive tracts, and immune systems; see these linked studies for more information); (4) Speeding up the decomposition process, which also helps prevent the spread of disease (vultures are such quick and efficient scavengers that they may reduce and/or prevent the (future) buildup of toxins in exposed dead bodies by stripping carcasses of meat only a few hours after an animal’s death (contrary to popular belief, vultures are not very big fans of rotten meat, and most species generally prefer their food as freshly dead as possible)); and (5) Regulating mesopredator and mesoscavenger populations (many species of which are vectors, not dead-ends, for pathogens and diseases found in carcasses).

Now, in contrast to other birds of prey, the feet of most vultures are flat, with long toes and blunted talons. While a majority have weak feet compared to predatory raptors, Accipitrid/Afro-Eurasian vultures’ feet are still relatively strong, as in notably stronger than those of Cathartids/American vultures (which are often described as ‘chicken feet’ because they’re that weak 😅). Because of this, most vulture species are unable to grip or carry items with their feet, as their feet are much, much better fit for walking on the ground (& carrion) and/or holding down carcasses. I say this because there are stories about various species carrying off livestock and even human children, but that’s just what they are: stories, myths. The reality is this is physically—literally—impossible for a majority of vulture species (including condors), if not all of them. In fact, when caring for young, vultures normally have to fill up their crops (a muscular pouch in the neck which functions as a storage place for food prior to digestion; the crop is only visible when it’s full of food), travel to their nests, and regurgitate the food from their crops to feed their chicks, as they cannot use their feet to carry meals.

In addition, vultures are often much bigger and heavier than other raptors, with larger wingspans and broader wing surface areas. They are so large and have such massive wingspans because they evolved in accordance to a lifestyle as obligate scavengers—thus also passive soarers, as obligate scavenging requires soaring for many hours and traveling great distances in search of carrion. Vultures’ wings are adapted for this very purpose, as they help the birds utilize thermals (rising columns of hot air) to gain altitude and soar + travel without expending a great deal of energy. (Hence the classic circling behavior, which rarely, if ever, has anything to do with a dead or dying animal on the ground below. When vultures do spot food, they descend to the ground quickly.) However, due to their size and large wings, vultures tend to be less agile and maneuverable in flight (esp. compared to various predatory raptors), which also limits any hunting abilities. (They are very elegant soarers, though!) Basically, my point here is while vultures may be birds of prey, and while they may occasionally hunt (usually going for weak and/or dying animals, or small animals like certain lizards, snails, etc.), they are not hunting specialists, and most of them are pretty sucky hunters because they’re just not built for it. Vultures are obligate scavengers and scavenging specialists because that is the lifestyle and form of survival they have evolved (physically, behaviorally, neurologically, etc.), because that is what they are physically adapted in accordance to.

[Do keep in mind that scavenger ≠ lazy, just as sucky hunter ≠ weak or bad fighter. Vultures are not scavengers because they’re too lazy to hunt, they are scavengers because—like I said—that is the lifestyle they have physically evolved in accordance to, that is what they are physically adapted and built for. To say a scavenger is ‘too lazy’ to hunt when said scavenger is physically incapable of surviving on a predatory lifestyle is not only to erroneously anthropomorphize the animal, but also to fail to understand ecomorphology and what an obligate scavenging lifestyle is like.]

In summary: As the only obligate scavengers of all living terrestrial vertebrates, these birds are keystone species to their environments/ecosystems, playing vital roles in speeding up the decomposition process, recycling nutrients, preventing pollution (keeping body fluids of carcasses from seeping into waterways, including drinking water), regulating mesopredator + mesoscavenger populations (many species of which are often vectors for diseases found in carcasses, unlike vultures), and (likely) regulating/preventing the spread of disease. The loss of vultures means the loss of a healthy ecosystem, which means the loss of a stable environment that supports us. It’s not just other species who need vultures, it’s humans who need them, too.

We need vultures!

(Just to be clear, non-human animals are not required—and should not be required—to meet our standards, benefit us, or receive our approval in order to be respected and left alone. Unfortunately, this is often overshadowed by the tendency for many to solely view other species through a black and white, resource vs. not resource, us vs. them, type of lens. Therefore, teaching about vultures often involves explaining their importance so that even those with such a perspective are able to open up more and appreciate these birds.)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

So, why have I dedicated part of this post to explaining the importance of vultures and debunking popular myths, instead of just giving a brief and succinct overview and linking other articles with more in-depth explanations? Well, the current situation is rather dire.

Vultures, despite their essential role as (apex) scavengers, are the most imperiled group of birds in the world right now, with 16 of the 23 species red-listed by the IUCN—that’s about 70% of all vulture species. Many species’ global populations have declined by >90% within the past 30 years, and nearly every factor behind the declines is human-caused, from poisons to infrastructure collision and poaching, among many other threats. There have been prominent consequences to the loss of vultures in areas where they were once so common: In India, the catastrophic decline in the vulture population has cost the country up to (in US dollars) $60–70 billion per year; human death rates in these regions also increased by over 4% following the decline. To learn more, I suggest reading up on the Asian and African vulture crises, both of which are heart-wrenching but important to be aware of.

I decided to give a more thorough explanation on the definition and ecological importance of vultures because without these birds, we humans would not have survived for as long as we have. Hence one of the main reasons why it’s not only in poor taste to toss ‘vulture’ around as a degrading label, it’s also spitting on the very barriers which shield us from disease outbreaks. I debunk myths and call out the negative—and, frankly, inaccurate—usage of ‘vulture’ here because these things are incredibly harmful to the birds themselves and, ultimately, to the environment. We cannot afford to continue using ‘vulture’ as an insult, and we especially cannot afford to continue spreading misinformation about vultures as if they are facts—vultures cannot afford this.

My other intention here is to show just how significant it is that Oikawa ends up playing for a team represented by a species of vulture. If Oikawa is a condor, then he is essentially a keystone species on the court, a critical part of any team he plays for. He effectively shapes the environment around him.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Putting the sad things aside, vultures are magnificent birds with tons of personality and beauty—both inside and out. I like to refer to them as the Corvids of birds of prey, as they are widely considered the most intelligent b.o.p. (alongside caracaras) and among the most intelligent birds thus far studied, with some species being part of only a handful of birds known to use tools and even wear makeup. They are also record-breakers: The Rüppell’s Griffon Vulture has held the spot as the highest-flying bird in the world for over 40 years; the Cinereous Vulture is the largest extant Accipitrid, and the Andean Condor is the overall largest living bird of prey; the Bearded Vulture is the only known vertebrate whose diet consists almost exclusively (70–90%) of bone; the Turkey Vulture, along with other species in the Cathartes genus, is believed to have the largest olfactory system of all birds, rivaled only by the Northern Fulmar, and thus is considered to have one of the best senses of smell in the animal kingdom; and I could go on, but I think the point is pretty clear.

All living vulture species.

(Via Birdorable)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Now that all of that is out of the way, let’s get back to the Andean Condor, Oikawa’s animal symbol. As I stated at the beginning, this is the largest living raptor, a bird who makes even the biggest living eagle species look small. Cathartids are also the closest living relatives of the extinct Teratorns (family Teratornithidae), the only other members of the order Cathartiformes. The largest bird of prey known to ever exist was the Teratorn Argentavis magnificens, also called the Giant Teratorn. Oikawa’s animal symbol is one of the largest (and heaviest) living birds and birds of flight, the largest (extant) flying land bird, the largest living raptor, and one of the seven closest living relatives of the largest bird of prey known to exist. Just keep all of that in mind throughout the rest of this analysis. :)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Here is some wonderful fanart of Oikawa with an Andean condor

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

UPCN mainly uses the indoor arena Estudio Aldo Cantoni in the city of San Juan, capital of San Juan Province, Argentina. San Juan is smack dab in the middle of the Andean Condor’s range; the significantly smaller Turkey and (American) Black Vultures can also be found here year-round.

[Something to keep in mind: Hinata ends up playing for Serviço Social da Indústria-SP, also known as SESI São Paulo or SESI-SP, a professional volleyball team based in São Paulo, Brazil, which competes in the Brazilian Super League. São Paulo is within the range of Black, Turkey, Lesser Yellow-headed, and King Vultures. We’ll dig a little deeper into this further down.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Anyway, what makes UPCN, aka Los Cóndores, so prominent in Haikyuu!!, and how exactly does the Andean Condor tie into this whole Oikawa-as-Alexander-the-Great-and-Iwaizumi-as-Hephaestion analysis? Well, let’s do a little bit of digging into the Andean Condor first.

Of all vultures, the Andean Condor is (obviously) the biggest; this is also the largest flying bird in terms of a combo measurement of weight and wingspan, meaning birds with larger wingspans generally have a lower average weight than the Andean Condor, whereas those who have heavier weight averages generally possess smaller wingspans; and, overall, this species’s wings have the largest surface area of any extant bird. The wingspan ranges from 270–320 cm (8 ft 10 in – 10 ft 10 in), and males reach a weight of 11 to 15 kg (24 to 33 lb) whereas females reach 8 to 11 kg (18 to 24 lb). Overall length (aka ‘height’) can range 100–130 cm (3 ft 3 in – 4 ft 3 in). Males are generally larger than females, which is unusual for birds of prey, but not so much for Cathartids; males are also larger than females among California Condors and King Vultures. To get a better grasp on the size of an Andean Condor, here is a lovely video showcasing the size difference between an adult male Andean Condor and an adult female Black Vulture. Black Vultures are not small birds, standing at a height of about 56–74 cm (22–29 in, or 1 ft 10 in – 2 ft 5 in), and with a wingspan of 133–167 cm (52–66 in, or 4 ft 4 in – 5 ft 6 in). However, for vultures, they are one of the smallest species, which puts into perspective just how large vultures are.

The Andean Condor is one of the few vulture species who exhibits sexual dimorphism, with males possessing a comb/crown known as a caruncle on the face, and females having red irises. Like all other vultures, Andean Condors are generally monogamous (though polyamory also occurs) and usually mate for life, with mates forming really close bonds and sticking together outside of the breeding season (and they can be quite affectionate); for condors, this means they may remain together for 50+ years. They are also amazing parents, taking equal part in incubating the egg(s) and raising offspring, who will remain with their parents for up to two years.

Andean Condors are generally the most dominant, or apex, scavengers at food sources, often being the ones to open up carcasses (or tear through the tough hides) of larger animals. Cathartes and Black Vultures, who condors often follow or keep an eye on in their search for food (Cathartes species are great carrion radars because of their advanced sense of smell, so other vultures often follow or watch them in case they find something), don’t have strong or sharp enough beaks to get past the hides of large animals, and thus generally rely on condors—including King Vultures—to fill in the role. This partly plays a role in the Andean Condor’s identity as a king or royal figure: the species is often referred to as ‘Rey de los Andes’ (‘King of the Andes’) and the overall king of vultures (sorry, King Vulture!). Quite obviously, one can see where we begin to make a connection between Oikawa as the Grand King and the huge bird in the sky.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

To better understand the Andean Condor’s place as the king of vultures, let’s go over some general vulture ecology. While vultures are obligate scavengers and scavenging specialists, already surviving on primarily carrion diets, there are also specialists within the scavenger hierarchy, or scavenging/vulture guild. What this means is different species specialize in different feeding strategies, and therefore play different roles at a carcass and in the process of breaking down carrion; in fact, we need the diversity of vultures within an ecosystem to help completely break down carrion. In other words, like in volleyball, each individual plays a different role here. These differences in feeding ecology have been correlated to differences in skull and beak shape (+ beak and bill size), and studies also suggest that they correlate to the number of cervical vertebrae as well. (Vertebrae are bones in the vertebrate spinal column; cervical vertebrae (or CV) are vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Birds have more CV than many other animals). Between the 23 extant vultures, there are three main groups that different species belong to in consuming a dead animal: (1) rippers or tearers, (2) pullers or gulpers, and (3) peckers, pickers, or scrappers.

Rippers, or tearers, like Lappet-faced, Cinereous, Red-headed, White-headed, and King Vultures, feed primarily on tendons and tough tissues—the cartilage and firm skin that other vultures might not be able to consume. Most rippers are among the largest vulture species, with comparatively short necks and narrow but stout and heavy, hooked beaks (which are hella strong), ideal for tearing through tough skin and hides, opening up carcasses, and ripping off tendons from bones and pieces of skin. Rippers are considered the apex scavengers of a guild, and a common vernacular name for a majority of them is ‘King’ or ‘Royal Vulture’: The Andean Condor—not necessarily a ripper, but often fills the niche of one—is the ‘King of the Andes’ and the overall ‘King of vultures’; the Yurok of the Pacific Northwest, who know the California Condor—also not exactly a ripper, but often fills the niche of one—as Prey-go-neesh, consider the bird the king of the skies; the Lappet-faced Vulture is occasionally referred to as the African King Vulture (in Portuguese, one of the vernacular names is Abutre-real: ‘Royal vulture’); the Cinereous Vulture is also known as the Monk Vulture (not royalty, but an interesting name nonetheless), more rarely the Eurasian or European King Vulture, and, occasionally, Jatayu (vulture demigod in Ramayana, also known as ‘King of the Vultures’); a fairly common name for the Red-headed Vulture is the Indian or Asian King Vulture (ex.: Bangla/Bengali এশীয় রাজ শকুন [Ēśīẏa rāja śakuna] and Hindi एशियाई राजा गिद्ध [eshiyaee raaja giddh], ‘Asian King Vulture’; Marathi राज गिधाड [Rāja gidhāda], Gujarati રાજ ગીધ [Rāja gīdha], Assamese ৰজা শগুণ [raja/roza shagun], ‘King Vulture’); in countries like Guinea-Bissau, the White-headed Vulture is known by locals as Jagudi-real (Portuguese and likely Mankanya and/or Mandinka [from ɟi-hudi (jugude), ‘vulture’], possibly a form of Kiriol or Crioulo: ‘Royal Vulture’); and, of course, there’s the King Vulture.

Pullers or gulpers like (most) Gyps vultures (those in the Gyps genus), Andean and California Condors (yes, they are technically pullers), and the Black Vulture, feed primarily on softer flesh and tissues, and viscera (internal organs), eating the bulk of the meat on any given animal. Most are among the medium-sized or larger vulture species, and generally have long, slender necks with minimal feathering, sharp bills, and serrated tongues (which all vultures have, though they are especially pronounced in this group) so that they can literally ‘gulp,’ or ‘suck,’ meat out of carcasses. Pullers account for the largest proportion of vultures by far, and are typically among the most social of vultures (and vultures, as we know, are already social in general), with species such as Gyps vultures often feeding in large groups. Many pullers are also pretty fierce competitors, capable of overtaking more dominant scavengers at a carcass by outnumbering them.

Peckers, pickers, or scrappers like Hooded, Egyptian, Cathartes, and (sometimes) Palm-nut Vultures, primarily feed on scraps and smaller pieces of meat in and around the carcass. They are generally the smallest species, with narrow skulls and comparatively elongated, narrow, pincer-like beaks and bills, suited for reaching into tiny crevices in bone frameworks like the skull, or along a leg bone, eating the morsels that larger vultures and other scavengers cannot access. While pickers are often the first to arrive at a carcass and begin eating, they usually have to wait for rippers to show up and open the carcass, as their beaks are not adapted for tearing through tough skin and hides. Because they are the smallest vultures, pickers usually linger at the edge of the crowd once the larger vultures have arrived (also partly because they get pushed out lmao), waiting until the rippers and pullers have finished to approach the carcass and clear up the scraps (+ pick bones clean).

Unlike the 21 other species, Bearded and Palm-nut Vultures do not specialize in carrion diets, though they are both still obligate scavengers (or at least Bearded is). For one thing, the Bearded Vulture’s diet is 70–90% bone. So, when pickers like Egyptian Vultures—and sometimes Hooded Vultures, where their range overlaps with the more fragmented Bearded Vulture populations in Africa—finish picking the bones of a carcass clean, Bearded Vultures step in to feed on those bones. (Note: Bearded is not the only vulture who eats bones; for many other species, bone fragments make up a small but fairly significant portion of their diet.) The Palm-nut Vulture, on the other hand, is a bit of a rebel: Over half of this species’s diet (>60% for adults, >90% for juveniles) is made up of the fruit-husks and fruits of oil (Elaeis guineensis) and raffia (Raphia sp.) palms, hence the bird’s name (‘palm-nut’ refers to the fruit or seed of a palm tree). However, they do occasionally join in at carcasses to assume the role of pickers.

There is a complex hierarchy to the scavenger/vulture guild: Rippers > Pullers > Pickers, though this may also vary because body size (the larger, the more dominant) plays a significant role in the hierarchy (thus the much larger Andean Condor is above the King Vulture), as does aggression, beak and bill size and strength, and numbers (e.g., the Cinereous Vulture is above the Eurasian Griffon Vulture in the hierarchy, but Eurasian Griffons may overpower/dominate Cinereous Vultures when they outnumber them at a carcass). Between individuals of the same species, hierarchies are based on age, size, and levels of aggression, as well as certain species-specific traits, such as dynamics between sexes (male condors are above females in the hierarchy, partly because they’re larger; for various Accipitrid species, this might be reversed) and skin color/flushing (species like the Lappet-faced Vulture and both condors flush, meaning the skin on their heads and necks change colors via blood flow (like how we blush) as a way to communicate and signify status in the hierarchy).

Keeping all of these things in mind, let’s consider how the feeding hierarchy works between the Andean Condor and other vultures in their range:

Andean Condor > King Vulture > Black, Turkey, and Greater Yellow-headed Vultures > Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture.

[BV, TuVu, and GYH are placed together because they’re all similar in size, and so dominance may shift between them depending on the circumstances (usually based on size, aggression, age, and/or numbers).]

The Andean Condor not only dominates the guild (ehem, king of vultures!), this species also makes food more accessible for smaller vultures and other scavengers by (occasionally) acting as a ripper and opening up carcasses (if the King Vulture hasn’t done so yet, where their ranges overlap). While there is competition with other scavengers and between individual vultures, the scavenging guild and the roles which these species have evolved in the breakdown of carrion create a sort of mutual dependence, or team effort, behind all of the competition and bickering. (Again, this is similar to volleyball, in which each person plays a different role.) Cathartes species and other small vultures help guide larger vultures/rippers to food sources, and these larger vultures/rippers open up the carcasses for everyone. (We’ll return to this little factoid about smaller vultures as guides later on.) As the ‘King’ and the top of the hierarchy, the Andean Condor is the leader of this team effort in their range, the figure who reduces some of the competition by making food more accessible to others. In looking after himself, the ‘king’ also looks after his team.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

“Condor Macho adulto.” (Source)

Adult male Andean Condor.

Credit: Skippercba

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

(This may not be connected to anything at all, but the fact that the two species with ‘Condor’ in their vernacular English names are from opposite hemispheres does remind me of Oikawa and Iwaizumi being in opposite hemispheres: One plays for a team in the Southern and Western Hemispheres (Oikawa) whereas the other works with a team in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres (Iwaizumi). Even when Iwaizumi travels to the Americas to meet Ushijima’s father in California, he remains in the Northern Hemisphere while Oikawa stays in the Southern Hemisphere. Andean and California Condors are both avian megafauna and sometimes considered evolutionary anachronisms, just as Oikawa and Iwaizumi represent ancient historical figures from an era so incredibly foreign to (most of) us that it has gained a sort of mystic quality to it.)

[Do keep in mind, however, that we must be careful when we describe condors as evolutionary anachronisms: Both Andean and California Condors responded to vanishing terrestrial megafauna by mainly feeding on the beached remains of coastal mammals, and thus survived the megafaunal extinction by adapting to the changes in their environments. While their large size and slow rate of reproduction may be seen as evolutionary anachronisms, both species lived alongside humans and maintained relatively stable populations for millennia, up until the last few centuries, when human activity significantly escalated to an unsustainable level. Condors are so threatened today, not because they ‘should have gone extinct’ alongside mastodons and the like, but because of harmful, unsustainable human activity which threatens both the birds and us.]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Now, onto vultures across different cultures. Vultures have a deeply-rooted, ancient relationship to humans tracing over 2 million years, all the way to our early, proto-human ancestors. There is evidence to suggest that early humans, in a similar fashion to other mammalian predators and scavengers, followed vultures to food sources. This relationship would eventually evolve into humans leaving deceased livestock out for vultures to eat and clean up, a practice which still takes place today in various regions of the world (Spain, Nepal, Cambodia, etc.). Both Neanderthals and Modern Humans have historically used vulture feathers and talons for clothes and accessories, their wing bones for wind instruments like flutes (and some vulture bone flutes are among the oldest thus far documented), and, on very rare occasion, their meat for food. Vultures are also prominent agents in the ancient funerary practice of sky burial, which is well-documented in archaeological records from around the world, and continues to be practiced today in Tibet, India, Mongolia, and neighboring regions. The earliest artworks and iconography of vultures stretch back over 10,000 years, with sites like Çatalhöyük, Göbekli Tepe, Nevalı Çori, Jerf el Ahmar, Ksar ‘Akil, and Nemrik, and the Chumash rock art, further attesting to this ancient relationship between man and bird. Today, vultures continue to hold sacred status in various indigenous belief systems around the world (Bön, Hinduism, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, Andean belief systems, etc.).

Speaking for mainly Accipitrid species, there is something quite interesting about their connection to Ancient Greek stories and symbols: After a man named Aegypius is tricked by his “friend” Neophron (Aegypius is the lover of Neophron’s mother, Timandre, and Neophron resents the relationship, so he tricks Aegypius into sleeping with his own mother, Bulis, who tries to blind her son once she recognizes him), he and Neophron are both turned into vultures by either Zeus or Apollo, depending on the source and version of the story. Aegypius would eventually become the name of a genus of Accipitrid vultures, of which the Cinereous Vulture is the only extant species; likewise, Neophron became the name of another genus, with the Egyptian Vulture being the only living species in it. Perhaps there isn’t any sort of connection to this story in Haikyuu!!, but I do find it interesting that of all Greek gods, either Zeus—who Ushijima’s animal symbol is linked to—or Apollo—who Karasuno’s animal symbol is linked to—turns these two men into vultures. The fact that Oikawa’s future volleyball club is represented by a species of vulture makes the story even more prominent to me.

If there is a link, what exactly does it mean? That in terms of ancient Greek symbols, Karasuno and Ushijima allude to deities whereas Seijoh simply represents mortality? Or perhaps because Oikawa and Iwaizumi, as birth and death, symbolize the cycle of life, and the plants associated with Seijoh also reflect on this, then vultures represent the cycle as beings who transform death back into life? (UPCN are Andean Condors, but perhaps the rest of Seijoh represent other vulture species, considering their dynamics.)

There is also a certain significance to the representation of vultures in various cultures (Greek, Roman, Celtiberian, Sumerian, Zulu, Nahua, Maya, Moche, etc.) as beings often associated with battlefields, as witnesses to warfare and attendants in sacrifice. We also see vultures represented as honorable warriors in many cultures, including those of the Mandé peoples, the Zulu, and the O’odham. This is likely important as well in Haikyuu!!, especially considering the allusions to Alexander and Achilles and their respective ‘halves,’ all four of whom are warriors in their own right.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

While vultures may not be as heavily linked to Greek gods like crows and eagles (and swans) are, they do represent royalty and deities in other cultures, such as that of the Ancient Egyptians. Multiple Egyptian goddesses are often directly associated with- and represented by vultures (Nekhbet and Mut are the two main vulture goddesses, but Isis and Hathor are also connected to vultures), and there was a prominent vulture crown worn by goddesses, Great Royal Wives, female pharaohs, and high priestesses. In Ancient Egyptian art, Nekhbet is usually depicted hovering in her vulture form, often with her wings spread above the royal image, clutching a Shen symbol (symbol of infinity, representing eternal encircling protection), though sometimes she is shown clutching an Ankh symbol (key of life, aka symbol of life) instead. The other main vulture goddess, Mut, is believed to be married to the solar creator god Amun-Ra, aka Ammon, aka the same deity an oracle claimed Alexander the Great to be the son of. Vultures were even used as hieroglyphs: (1) the Egyptian Vulture hieroglyph was used for the letter ‘A’ or phonogram ‘ah’ in the ‘official’ alphabet (so to speak), and there are at least two other glyphs of this species; and (2) the Eurasian Griffon Vulture hieroglyph, transliterated as ‘nr’ or ‘nrt’, phonetically ‘mwt’ or ‘mt’, is a logogram for the bird itself and for ‘mother’; like the Egyptian Vulture, there are at least two other glyphs of this species, one of which is a logogram of Mut, and the other, with a cobra next to the vulture, being a logrogram of ‘Two Ladies’ (further discussed below). The double crown, worn by the pharaoh, includes the symbols of Upper and Lower Egypt: A white vulture and a cobra. Furthermore, the Lappet-faced Vulture is also frequently depicted in Ancient Egyptian artwork, often interchangeably with the Eurasian Griffon.

“Collier au vautour.” (Source)

Lappet-faced Vulture pectoral from Tutankhamen’s tomb.

Credit: Siren-Com

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Because they were so sacred, vultures received special protections under pharaonic law, and harming or killing a vulture was punishable by death. In fact, the Egyptian Vulture was one of the first animals, and actually likely the first bird, to be legally protected—a factor contributing to the species’s nickname, ‘Pharaoh’s chicken.’

Nekhbet’s counterpart is Wadjet, the goddess of Lower Egypt, whose animal symbol is mainly an Egyptian Cobra. These two are often depicted together as the ‘Two Ladies’ to symbolize the unity between Upper and Lower Egypt, hence the vulture and cobra on the pharaoh’s crown—which is usually the double crown, a combination of the white crown of Upper Egypt (Hedjet) and the red crown of Lower Egypt (Deshret). While Nekhbet is normally a vulture and Wadjet is normally a cobra, they are occasionally portrayed interchangeably or with features of both animals (there is artwork of Wadjet with the body and wings of a vulture and the head of a cobra). Similarly, Isis is typically paired with her sister Nephthys in funerary rites, as they are the two major funerary goddesses. Nephthys is a protective goddess who symbolizes the death experience, just as Isis represents the birth experience. This connection between vultures and pairs of complementary figures is a fairly common motif across various cultures, which is another reason why I feel Oikawa’s ultimate representation as a condor is so important here. Perhaps the significance of condors/vultures in Haikyuu!! also connects back to their role as symbols of Egyptian goddesses who represent both life and death. If so, then surely we can interpret Iwaizumi as also being represented by a vulture, given his association with death in contrast to Oikawa’s association with birth.

[Also, vultures were heavily associated with maternity and motherhood in general in Ancient Egypt, primarily because they are such dedicated, caring parents, and Nekhbet, Mut, Isis, and Hathor are considered major maternal goddesses (as hinted through the hieroglyphs, ‘Mut’ is literally ‘Mother,’ and this was also one of the most common words used to refer to vultures). In fact, ancient Eastern Mediterranean cultures commonly considered vultures to be all females and to reproduce via parthenogenesis, or asexually. (And it turns out that this isn’t as far out there as it seems.) I always laugh a little bit when I remember this because it somehow reminds me of the “Iwa-chan, are you my mom?” scene ggdfdgffyghhgbugjug]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In the Hindu epic Ramayana, there are two demi-god brothers who have the forms of vultures: Jatayu (who is sometimes depicted as an eagle) and Sampati. They are the sons of Shyeni and Aruna, Aruna being the charioteer of Surya (Sun god), personification of the reddish glow of the rising sun, and older brother of the legendary Garuda. When they were young, Jatayu and Sampati used to compete to see who could fly higher. On one such instance, Jatayu flew so high that he was almost seared by the sun's flames. Sampati saved his brother by spreading his own wings, thus shielding Jatayu from the hot flames. In the process, Sampati got severely injured and lost his ability to fly. As a result, Sampati was to be essentially ‘wingless’ for the rest of his life.

[There are various stories similar to this across the globe: A vulture shields someone or something from the sun, and is killed or permanently injured, often losing a great deal of feathers (often on the head), as a result. For example, see the Lenape story of the Turkey Vulture moving the sun back from the earth.]

According to the Ramayana, the demon and Lanka king Ravana is abducting the goddess Sita when Jatayu tries to rescue her. Jatayu fights valiantly with Ravana, but as Jatayu is very old, Ravana soon defeats him, clipping his wings, and Jayatu falls onto the rocks in Chadayamangalam. Sita’s husband and Vishnu’s avatar, Rama, and his younger brother, Lakshmana, are searching for Sita when they discover the stricken and dying Jatayu, who informs them of his battle with Ravana, and tells them that Ravana is heading south. Jatayu then dies of his wounds, and Rama performs his final funeral rites.

Later on in the epic, Sampati appears to an exhausted search party consisting of: Hanuman, the Hindu god and divine vanara (a forest-dwelling people, generally depicted as humnanoid apes or monkeys) companion of Rama; Angad, a vanara and the son of a powerful vanara king; Jambavan, the divine-king of bears (depicted as an Asian Black Bear or a Sloth Bear), created by the god Brahma to assist Rama in his struggle against Ravana; Nala, a vanara and the son of Vishwakarma (craftsman deity and the divine architect of the gods in contemporary Hinduism); and Nila, a vanara chieftain in the army of Rama, Nala’s brother (though with a different father: Agni, the fire god of Hinduism, one of the five inert impermanent elements (fire), and the guardian deity of the southeast direction), and commander-in-chief of the monkey army under the monkey king Sugriva. The group, thirsty and depressed, reach the southern end of the land, where they have the endless sea before them, and still no sign of Sita. They collapse in the sand, disappointed, and unable and unwilling to move or act any further. When Sampati finds them, he openly talks about his luck in having so many easy meals right before him. It is at this point that Jambavan laments out loud, comparing the morals of a vulture who would prey on the weak and helpless (which...I mean...I get the morality and sentiment behind this, but—despite the fact that vultures rarely ever hunt to begin with—how else is a flightless vulture supposed to survive? Perhaps I shouldn’t interpret this too literally lmao) with the vulture Jatayu, who sacrificed his life defending Sita from Ravana.

Upon hearing his brother’s name, Sampati freezes, then asks to be told the story of Jatayu’s battle with Ravana. After he learns of Jatayu’s fate, Sampati weeps and reveals that he is Jatayu’s brother, and that the two hadn’t been in contact or talked to each other in a long time. Grateful to the party for sharing Jatayu’s story, Sampati informs them that Sita had been taken south to Sri Lanka; because of this, Sampati becomes an instrumental part of the search for Sita. As a reward for his assistance and selflessness, Sampati’s wings are healed, and he is once again able to fly.

Like Nekhbet and Wadjet, and Isis and Nephthys, Jatayu and Sampati are a pair of (often) opposing associations: flighted vs. flightless, ‘king of vultures’ and well-off vs. starving and desperate. Yet the two are famous for their selfless acts, for both each other and Sita.

“Sampati’s Find.” (Source)

Sampati points the search party towards Lanka.

Painting by Balasaheb Pant Pratinidhi

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In various Olmec, Maya, and Nahua cultures, those of high and/or even royal status were often buried with (jade) pendants depicting vultures (a King Vulture, more specifically). Like the Ancient Egyptians, the Maya, Nahua (the Mexica in particular), Zapotec, and Mixtec, among a few others, developed glyphic writing systems in which vultures—namely the King Vulture—are used as glyphs. In fact, the King Vulture is one of the most frequently represented birds in the Maya codices.

Throughout the Americas, vultures feature prominently as beings connected to fire, the sky, agriculture, rain, fertility, and purification. They are the keepers of fire and bright things in general, the shamanic birds of transformation. Among the Menominee, the Turkey Vulture, known as Apaeskasiw, is the figurehead of the Turkey Vulture or Turkey Buzzard clan, as well as a Thunderer. Turkey Vultures are especially sacred to the O’odham peoples, who refer to the species as Ñui; according to the O’odham, Ñui was present at the inception of the world, and his wings helped shape the desert, making water flow possible. For the Cherokee, the Turkey Vulture, known as ᏑᎵ (Suli), created the Appalachian Mountains with his wings when he flew too close to the ground. The Bribri consider Turkey Vultures to be bringers of food to orphans and the honorable, whereas vultures in general are healers, protectors, teachers, and dancers, as well as messengers of Sibö (God). One story frequently told across cultures is that of a man who, assuming vultures have an easy life, decides to switch places with a vulture, only to discover that the opposite is true.

As for condors, the name ‘Condor’ comes from the Quechuan Kuntur, which is one of the indigenous names for the Andean Condor. Quechua, known as Runasimi (‘language of the people’) or Qhapaq Runasimi (‘great language of the people’) in Quechuan languages, is a language family thought to have originated from Indigenous Peoples in the southern and/or central highlands of Peru around 2,000 years ago; it was also the official language family/lingua franca of the Inca Empire, though not an original language (family) of the Inca, as (1) Quechua originated and was spoken in Peru 1,000+ years before the Inca rose to power, and (2) many of the high-ranking officials/upper-class people and founders of the Kingdom of Cusco, and then the Tawantinsuyu (Inca Empire), spoke Puquina, not Quechua, as a first language. Kuntur is what the Quechua and Quechuanized peoples—any Indigenous Peoples of the Andes mountains who speak the Quechuan languages—have called the Andean Condor for centuries, likely millennia (for the Wanka, Chanka, etc.). Not all species in the Americas retain English and/or Spanish vernacular labels derived from one of their indigenous names, but the Andean Condor has, largely because condors are so deeply embedded into the frameworks of Andean cultures, to the degree of being biocultural keystone species in South America.

The Andean Condor is so deeply sacred to the cultural landscape of South America that the species is regarded as a national symbol of seven countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela), is the designated national bird of four countries (Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, and Ecuador), and is displayed on the national shields, flags, stamps, and coins of Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.

Condors are central to various Andean and Amazonian cultures, and both the Andean Condor and King Vulture are extremely prominent in indigenous belief systems/world views, rituals, kinship systems, astronomy, medicine, place names, literature, and politics. Among the Akurio people, for example, King Vultures, known as Akalanti, are physical manifestations of deceased Akurio people’s souls, the direct common ancestors of all Akurio. A closely related group, the Kalina, hold a similar view, except they call the King Vulture Anuwana. Condors have also appeared in indigenous artwork for millennia, from the textiles and ceramics of the Moche and Nazca in coastal Peru, to the Temple of the Condor at Machu Picchu, the rock art of the Chinchorros and their descendants (the Changos) in the Atacama desert, the musical instruments of the Yotoco in Colombia, and the ceramics of the Paraná river. The condor occasionally appears on the Chakana, the Quechua name of a three-stepped Andean symbol (possibly representing the three stages of Andean life), alongside a snake and a puma. For various Andean peoples, the snake symbolizes the lower or underworld, the puma represents the middle world of earth, and the Andean Condor stands for the heavenly/upper world in the sky (hanan pacha or Jananpacha). Condors connect the Jananpacha to life on earth, and they carry the dead on their wings to the Jananpacha. For many Indigenous Peoples of the Andes, the condor is the immortal representation of the Jananpacha: the upper world, sky, and future. Friendly reminder that Oikawa is prominently connected to immortality!

“Earflare with condor.” (Source)

Moche ear flares with condors, likely either King Vultures or stylized condors (i.e., condors with traits of both Andean Condors and King Vultures).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Furthermore, the Andean Condor is heavily tied to the sun god Inti, often considered a sort of messenger for said god. In Andean cosmology and culture, the sun serves as the centerpiece, and only the condor has the royal charge of tending to it; every day, the condor is to carry the sun out of the sacred lake of Wynaqocha to the highest point in the sky, release it, and let it fall back to earth. Similar to their connection with Inti, the Andean Condor is considered a manifestation of a mountain deity, and acts as a representative or messenger of mountain deities or protectors/guardians. The condor is also the totem of the clan condori.

In Andean belief systems, the Andean Condor was present at the inception of the world and the Andean sphere, as well as at the founding of Quito. According to legend, Quitimbe, the founder of Quito, arrived at the city’s present location after fleeing from giants. His wife, bitter at being abandoned, tried to kill their son, but a condor rescued the child and took him to the mountains.

The condor’s connection to the upper world is further enhanced through other indigenous stories. For example, a native legend from the Department of Ancash in Peru tells of a fox that longed to have the bright and clean markings of the condor. He pleaded with the condor to divulge the secret of the whiteness in his plumage, until the condor finally relented and agreed to help the fox change the color of his coat. At midnight, he took the fox to the snow fields of the Cordillera Blanca and left him there. When the condor returned several hours later, the fox was dead. The story illustrates a typical position of the condor as a bird with an immortal-like character able to withstand the elements of any altitude, a being worthy of respect.

According to another legend, when condors feel old and nearly out of strength, they fly to the highest mountain peak, fold their wings, pull in their feet, and plummet down to the depths of the canyons, where their reigns end. These deaths are symbolic, as with this act, the condors return to their ‘nests’ in the mountains, where they are reborn into new cycles, new lives. (Unlike Accipitrid vultures, American vultures don’t actually build nests, so this probably refers to a cave, crook, or rocky overhang where the eggs are laid and the chicks are raised.) In some variations of this legend, it is not age that drives the condor off a cliff, but the death of the bird’s life-long mate.

Moche vessel in the form of a condor. (Source)

Credit: Thesupermat

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

So, how exactly does this legend of death and rebirth link back to Alexander and Hephaestion, and even Achilles and Patroclus? Well, for one thing, there’s the variation in which condors plummet off the cliffs after losing their mates; this act itself can be seen as a sort of parallel to Achilles and Alexander in their grief up until their own deaths. Their pillars—their internal ‘hearts,’ souls/spirits, and mortal halves—are dead, and so they eventually spiral down into death as well.

As for the condor’s rebirth, when in connection to the relationship itself, I personally interpret this as a parallel to a sort of reincarnation, or repetitive existence, of the ‘royal’/‘immortal’ and the pillar throughout history, mythology, literature, and storytelling. We have Achilles and Patroclus, Alexander and Hephaestion, and Oikawa and Iwaizumi, but we also have various similar parallels outside of these three pairs: Gilgamesh and Enkidu; Cycnus and Phylius (who actually seem a bit closer to Shiratorizawa, considering the animal symbols associated with them, though vultures do happen to also appear in their story: Cycnus challenges Phyllis to capture two ‘man-eating’, ‘dangerous’ (🙄🤦♀️) vultures, and bring them to him); Heracles and Abderus or Heracles and Hylas; Apollo and Hyacinth; Roman emperor Hadrian and his lover Antinous (who died young and unexpectedly, resulting in Hadrian having him deified (without the permission of the Senate, might I add), founding an organized cult devoted to his worship, founding the city of Antinoöpolis close to Antinous's place of death (which became a cultic center for the worship of Osiris-Antinous), and having so many sculptures and other artworks of Antinous created that he’s now one of the most common faces archaeologists unearth in the region (and they are still finding Antinous sculptures!)); Cúchulainn and Ferdiad or Cúchulainn and Láeg in the Ulster Cycle; Minamoto no Yoshinaka and Imai Kanehira in the Japanese epic The Tale of the Heike; and the list goes on. Vultures themselves also often connect to pairs of binary yet complementary figures, so Oikawa’s ultimate representation as a condor further reinforces this parallel.

While not all of these pairs are exact parallels of each other, they still have a lot in common regarding the ‘royal’/‘immortal’ and close childhood friend/pillar/mortal relationship. With each pair’s deaths (aka one dies, the other metaphorically dives off the cliff in response), they are reborn into another pair (returning to the nest). A single life is not immortal, but the continuation of life, the constant transformation of death back into life (what vultures primarily represent), and the cycle which pulls at existence have yet to become anything else but immortal. Achilles and Alexander the Great were not immortal, but their names, stories, and legacies are still widely known and spoken of today, as are Patroclus and Hephaestion’s. Neither the ‘royal’/‘immortal’ nor the pillar/mortal are immune to death, but both have essentially become immortal, or at least long-lived, in name, in repetition, in storytelling.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The condor’s connection to Inti is also extremely important here. Why? Because Inti is a solar deity, and various cultures perceive vultures as heavily connected to the sun.

In terms of Egyptian mythology, after the rebellion of Thebes against the Hyksos and with the rule of Ahmose I (16th century BCE), the god Amun acquired national importance, expressed in his fusion with the Sun god, Ra, as Amun-Ra or Amun-Re. Friendly reminder that (1) the vulture goddess Mut is often believed to be married to Amun, and (2) Alexander was proclaimed the son of Ammon (but not the son of Mut, btw). In addition, while the god Horus was said to be the sky, he was considered to also contain the Sun and Moon. The Sun was believed to be his right eye while the Moon was believed to be his left, and they traversed the sky when he, a falcon, flew across it. Horus is the son of Isis, one of the goddesses known to take on the form of a vulture; in other myths, he is the son or husband of Hathor, another goddess connected to vultures and the sun. Mut, Nekhbet, Isis, and Hathor have all been portrayed acting as the Eye of Ra, a being that functions as a feminine counterpart to the sun god Ra. The Eye is an extension of Ra's power, equated with the disk of the sun, but she also behaves as an independent entity. She is his partner in the creative cycle in which he begets the renewed form of himself that is born at dawn. The Eye defends Ra against the agents of disorder that threaten his rule. She is usually portrayed as a snake or a lioness, but there are occasions in which she may be associated with other animals, including vultures, who the Egyptians admired for their ability to locate food by sight.

In addition, remember that the vulture brothers Jatayu and Sampati of the Hindu epic Ramayana are the sons of Aruna, the charioteer of Surya (Sun god) and personification of the reddish glow of the rising sun. Let us also not forget the various stories in which a vulture shields something or someone from the sun, as well as legends of a vulture retrieving fire from the sun for humans. For many Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, vultures, as keepers of bright things and beings of the sky, regularly interact with the sun. Vulture behavior is even heavily tied to the sun, as vultures frequently sunbathe—to the degree of there being a name for their sunning posture: the horaltic pose—and rely on the sun to travel vast distances, as the thermals vultures utilize to soar typically form through solar radiation.

Why is all of this important?

Because crows are solar symbols.

Now, in terms of their relationship in real life, crows and vultures have a sort of scavenger-scavenger rivalry mixed in with some mutual dependence/symbiosis. Corvids like crows, ravens, jackdaws, rooks, magpies, etc. are often the first to arrive at a carcass, and their presence and activity (calling to mates and flocks) alerts other scavengers, including vultures, that there is food. Corvids generally do not have the beaks and bills strong and/or sharp enough to open up a carcass (especially a large animal with a thick hide), so they rely on larger scavengers like vultures to make carrion more accessible.

At the same time, crows and vultures share many similarities: Both are scavengers, and can often be seen together at carcasses; both are highly intelligent, with some species documented using tools; both are highly social and family-oriented, with communal roosts and pairs generally mating for life and being bi-parental (i.e., both mates equally contribute to raising offspring); both tend to contradict the general expectations and stereotypes of their respective groups (vultures for birds of prey, crows/Corvids for songbirds); both are comparatively large for their groups (birds of prey and songbirds); both have ancient relationships with humans stretching back millions of years; both are heavily connected to the sun in various cultures; both are psychopomps in various cultures; both are also considered guides, whether of the living or the dead; both often feature prominently in creation narratives and stories about the origin of fire; and the list goes on. It is not surprising that there is a lot of overlap between them culturally, but these overlaps are especially significant in Haikyuu!!, in which they may be intentionally referenced on Furudate’s part. In other words, it is likely that Furudate is not only aware of the parallels between crows and vultures, but has also utilized them to further develop the parallels between Karasuno and Seijoh; this is especially true of the various parallels between Oikawa and Kageyama, their relationship with their ‘other half,’ and the dynamics of their teams.

Let’s not forget the fact that Hinata, like both crows and vultures, is heavily tied to the sun, and likely represents it as well, through his appearance, name, and overall personality.

This is exceedingly important when we consider another significant fact about Karasuno’s mascot: There are no living crow species native to South America, which means UPCN in Argentina and Hinata’s team in Brazil are outside the range of all crows. In their absence, caracaras, American Blackbirds (grackles, oropendolas, etc.), and the smaller Cathartid species fill in similar niches in these ecosystems. Why is this significant? Well, ‘crow’ is also a common name for all Cathartids except the Andean and California Condors. Let’s look at some of the vernacular names of various American vultures in a few South American countries and the Caribbean. (NOTE: ‘Vernacular name’ does not necessarily mean it is the most common name for a species in an area or a language, or that it is even very common at all, it just means that it is one of the vernacular names listed by authorities. The names below are those with connections to crows, so more common terms including Urubú, Zopilote, Jote, Gallinazo, and Buitre are not listed because there’s no connection.) Below are a few examples:

(American) Black Vulture

Firstly, William Bartram writes of the Black Vulture in his 1792 book Bartram’s Travels, giving the species the Latin name Vultur atratus, and calling them ‘Black Vulture’ (translation of the Latin name) or ‘Carrion Crow.’

Secondly, for the Black Vulture’s official binomial name, Coragyps atratus, the genus Coragyps means ‘Raven-vulture’ or ‘Crow-vulture’ from a contraction of the Greek corax/κόραξ (‘Raven,’ ‘Crow’) and gyps/γὺψ (‘Vulture’; when going back over vulture species, note how a large majority of them have ‘Gyps,’ ‘Gyp,’ or ‘Gryph’ somewhere in their scientific names). The specific epithet, atratus, is from the Latin ãtrãtus, meaning ‘Clothed in black (for mourning)’ or ‘Darkened/Blackened,’ from ãter, ‘Black.’ Coragyps atratus can therefore be translated as ‘Raven-vulture/Crow-vulture clothed in black.’

Two vernacular names are Cuervo negro (Spanish, ‘Black vulture’, lit. ‘Black crow’ or ‘Black raven’) and Cuervo cabeza negra (Spanish, ‘Black-headed vulture,’ lit. ‘Black-headed crow’ or ‘Black-headed raven’) in Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguay, and various other countries.

Another name is Corvo-de-cabeça-preta (Portuguese, ‘Black-headed vulture’, lit. ‘Black-headed crow’ or ‘Black-headed raven’) in Brazil, though Urubú or Urubu is often used instead of Corvo.

Yryvu (Guaraní, ‘Vulture’ or ‘crow’; the origin of Yryvu is unclear, though sources in Spanish do liken it to Cuervo) and Yryvu hû (Guaraní, ‘Black vulture,’ ‘Black crow’) are common vernacular names in Paraguay, southern Brazil, and northeastern Argentina.

Known as Cuervo de Juan (Spanish, ‘John Crow’) and Cuervo carroñero (Spanish, lit. ‘Scavenger crow/raven,’ ‘Carrion crow/raven,’ or ‘Vulturelike crow/raven’) in some areas of the Caribbean.

Some other vernacular names include Rabengeier (German, ‘Black vulture,’ lit. ‘Raven vulture’) and Ravnegrib (Danish, lit. ‘Raven vulture’).

Turkey Vulture

One vernacular name is Cuervo cabeza roja (Spanish, ‘Red-headed vulture,’ lit. ‘Red-headed crow’ or ‘Red-headed raven’) in Uruguay, Paraguay, parts of Argentina, and various other countries.

Another is Corvo-de-cabeça-vermelha (Portuguese, ‘Red-headed vulture,’ lit. ‘Red-headed crow’ or ‘Red-headed raven’) in Brazil, though Urubú or Urubu is often used instead of Corvo.

Yryvu akâ virâi (Guaraní, ‘Bald-headed vulture’) in Paraguay, southern Brazil, and northeastern Argentina.

Like the Black Vulture, this species is known as Cuervo de Juan (Spanish, ‘John Crow’) and Cuervo carroñero (Spanish, lit. ‘Scavenger crow/raven,’ ‘Carrion crow/raven,’ or ‘Vulture-like crow/raven’) in some areas of the Caribbean.

In anglophone regions of the Caribbean, the species is colloquially known as ‘John Crow.’

The John Crow Mountains of Jamaica, suggested to have also once been known as the ‘Carrion Crow Ridge,’ are named for the Turkey Vulture, which is fairly abundant in the area.

Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture

Known as Cuervo cabeza amarilla (Spanish, ‘Yellow-headed vulture,’ lit. ‘Yellow-headed crow’ or ‘Yellow-headed raven’) and Cuervo sabanero (Spanish, ‘Savannah vulture,’ lit. ‘Savannah crow’ or ‘Savannah raven’) in Paraguay, Uruguay, and parts of Argentina.

Also Corvo-de-cabeça-amarela (Portuguese, ‘Yellow-headed vulture,’ lit. ‘Yellow-headed crow’ or ‘Yellow-headed raven’) and Corvo-menor-de-cabeça-amarela (Portuguese, ‘Lesser yellow-headed vulture,’ lit. ‘Lesser yellow-headed crow/raven’) in Brazil, though Urubú or Urubu is often used instead of Corvo.

Yryvu akâ sa’yju (Guaraní, ‘Yellow-headed vulture’) in Paraguay, southern Brazil, and northeastern Argentina.

Greater Yellow-headed Vulture

One name is Mayor cuervo cabeza amarilla (Spanish, ‘Greater yellow-headed vulture,’ lit. ‘Greater yellow-headed crow/raven’). This isn’t used very often, though, as GYHVs usually occur outside of the areas where vultures are more commonly referred to as Cuervos.

Another is Corvo-maior-de-cabeça-amarela (Portuguese, ‘Greater yellow-headed vulture,’ lit. ‘Greater yellow-headed crow/raven’), Corvo-da-mata (Portuguese, ‘Forest vulture,’ lit. ‘Forest crow’ or ‘Forest raven’), and ‘Corvo-amazónico’ in Brazil, though Urubú or Urubu is often used instead of Corvo.

[ALSO: In Uruguay, the name of the landmark Quebrada de los Cuervos (Spanish, lit. ‘Crows’ Ravine/Ridge’ or ‘Ravens’ Ravine/Ridge’) refers to the various ‘crow-like’ vultures—Black, Turkey, and Lesser Yellow-headed—who roost and breed on its cliffs.]

King Vulture

Cuervo real (Spanish, ‘Royal vulture,’ lit. ‘Royal crow’ or ‘Royal raven’) and Cuervo blanco (Spanish, ‘White vulture,’ lit. ‘White crow’ or ‘White raven’) in Paraguay.

Corvo-branco (Portuguese, ‘White vulture,’ lit. ‘White crow’ or ‘White raven’) in Brazil, though the species is more commonly known as Urubu-rei (Portuguese, ‘King vulture’), Urubu-real (Portuguese, ‘Royal vulture’), Urubu-branco (Portuguese, ‘White vulture’), Urubutinga (Old Tupi and Portuguese, ‘White vulture’), Urubu-rubixá (Tupian languages and Portuguese, ‘Chief of the vultures’), and/or Iriburubixá (Tupian languages and Portuguese, ‘Chief of the vultures’).

Yryvu ruvicha (Guaraní, ‘Chief of the vultures’) in Paraguay, southern Brazil, and northeastern Argentina.

This is significant because it further highlights the parallels and overlaps between vultures and crows. Since vultures and crows are so similar ecologically, when one is absent from a region, the other often fills in a similar niche. Not only can this be seen in South America, where Cathartid vultures play similar roles as crows, but also in areas absent of vultures (northern Europe, Japan, Australia, etc.), where crows (and ravens) fill in somewhat similar roles as vultures. In fact, these similarities have even been noted in folk taxonomy and indigenous classification systems, in which vultures are often placed in a category between crows and eagles, classified as a sort of mix between the two. Among the Desana people, for example, vultures are known as ‘ancient eagles’; among the Cherokee, one of the names for the Turkey Vulture is said to be ‘peace eagle,’ though I’m not sure of the validity of this claim due to the lack of sources on it. For the Nahua, the King Vulture is known as Cozcacuauhtli, ‘Jewel-collared eagle.’

What does this have to do with Hinata? Refer back to the story of the two crows or ravens who helped guide Alexander the Great through the Egyptian desert to Amun’s sanctuary (where the oracle of Siwah declared him the son of Zeus-Ammon). In a similar way, vultures have also acted as guides for people, mainly in guiding humans to food sources. Furthermore, vultures will utilize both crows and other (smaller) vultures as guides to food. In terms of Haikyuu!!, Hinata and Kageyama, as crows, both act as external guides of sorts for Oikawa, just as Iwaizumi and the rest of Seijoh, as possible vultures, also act as his guides, except from the same side.

For example, consider the interactions between Oikawa and Hinata in the final arc. They form a stronger relationship when they play beach volleyball together, and it has been interpreted that Hinata helps Oikawa rediscover the joys of playing volleyball. This interaction between Oikawa and Hinata can be interpreted in a few different ways, and is likely meant to have double meanings. One is that even when Hinata is outside the range of crows, he still acts as one by being a guide of sorts for Oikawa; but briefly, he falls in that place between crow and eagle, in the position of a vulture. This is all the more prominent when we remember that all Cathartid species are known by the name ‘condor’ (コンドル, ‘Kondoru’) in Japanese. In other words, ‘condor’ in Japanese refers to any of the seven Cathartid species, and there is no vulture vs. condor dichotomy among Cathartidae as there often is in English. Thus the five vulture species of Brazil (Black, Turkey, Lesser Yellow-headed, Greater Yellow-headed, and King Vultures) are all condors in Japanese; these species in particular are both ‘crows’ and ‘condors’ in a vernacular manner. When he briefly falls in the position of a vulture, Hinata becomes both ‘crow’ and ‘condor,’ someone on the same team as Oikawa. Another interpretation is that Hinata is the sun himself, and where there is no Kageyama—no crow—to be his messenger and ‘other half,’ there is Oikawa to fill in a similar niche; where there is no crow to assist the sun and act as a solar messenger, there is a vulture.

If Hinata had played volleyball in any other country, perhaps the parallels and overlaps between vultures and crows would not have stuck out so much to me, but the fact that he plays in Brazil makes it all the more special. Brazil is home to around 40% of the Black Vulture’s global population, and the species is so common here that they are considered a sentinel species for the health of the environment. In fact, an entire sports club, Flamengo, has designated the Black Vulture—Urubu—as their official mascot. Flamengo has the most popular football team in Brazil, with over 40 million fans. Vultures in general feature prominently in cultural traits across the country, and, as previously explained, are sacred to various Indigenous Peoples of the region.

(Another interesting tidbit is the mascot for Hinata’s Brazilian team, SESI-SP, is a puma/cougar/mountain lion, which represents the middle world of earth for many Andean peoples. There’s also this cool little factoid: Andean Condors have been documented harassing pumas off of food sources. Hinata’s other team, MSBY, is represented by a jackal (most likely a Black-backed Jackal), a type of Canid mesopredator and mesoscavenger who also regularly interacts with vultures at food sources, and who is also prominent in Ancient Egyptian belief systems (through the god of funerary rites and the guide to the underworld, Inpu/Anpu, aka Anubis). I’m not as knowledgeable on Felids and Canids in different cultures, so if anyone would like add onto this, feel free to!)

“I feel pretty.” (Source)

Turkey Vulture sunbathing in the horaltic pose at Lake Los Carneros, California, USA. (Look at that sweet little face!!!! TuVus are the best ^.^)

Credit: Steve Colwell

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

While each of the stories discussed in this analysis come from different cultures and have different origins, the ongoing parallels between solar deities and animal symbols in these stories, and the connection Haikyuu!! has to said deities and symbols, are quite clear.

While Oikawa may be connected to the vulture goddesses of Egypt, I personally feel like he more-or-less represents the pharaoh or royalty that the deities protect, primarily because Furudate depicts Oikawa through allusions to Alexander the Great, who we know was a pharaoh of Egypt. Oikawa is the condor, the king of vultures, and he shares a greater connection to the condor in Andean beliefs through the concept of power, royalty, and immortality, which both Alexander and Achilles are also closely linked to.

Iwaizumi, as the pillar, is likely more related to the vultures as guides and messengers, and to vulture deities as protectors and bringers of life and death. Why a bringer of life and death? Oikawa and Iwaizumi both equally represent life and death: A beginning is also an end, and an end is also a beginning. Let us also remember that Iwaizumi connects both aspects because his day of birth is the day of Alexander the Great’s death; he is both a beginning and an end. Birth on the day of a death also implies rebirth, which both characters—but especially Iwaizumi—are linked to as well. Iwaizumi is the bird hovering above the pharaoh with spread wings, the one who protects the king, not necessarily by guarding him from threats, but by consistently reminding him of his own mortality, advising him to take breaks and not overdo himself, and challenging him.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

There is so much on the cultural significance of vultures that I have yet to cover, so I will just leave a brief list of some other topics regarding vultures in different cultures:

Romulus and Remus and the founding of Rome (the augury competition over who spots more vultures). More sources can be found here.

The relationship between vultures and ancient armies, particularly the ancient Greeks and Romans, the latter of whom often considered the presence of vultures on the battlefield a positive thing (as they play a prominent role in the founding of Rome). When the Roman commander Marius (157–86 BCE) was leading campaigns against the Germanic tribes (the Cimbri, Teutones, Ambrones) in Europe, two vultures made a habit of hovering over his armies as they marched to victories. One day, the troop’s blacksmith forged two bronze collars, and the soldiers managed to capture the vultures, place the metal bands around their necks, and release them (note: I do not recommend doing this lmao). Whenever the soldiers spotted the birds and saw the collars flashing in the sun, their spirits were raised, and they would cheer their soaring escorts. This anecdote, which happens to be a description of the earliest documented bird banding, was first reported by the zoological historian Alexander of Myndus, and cited by Plutarch in his Life of Marius.

Vultures and other birds in the Iliad. (Hector literally tells a dying Patroclus the vultures will pick at his bones where he lies, which doesn’t actually happen. It’s basically Hector’s way of insulting Patroclus and Achilles’s dignity, hence one of the reasons why Achilles gets so pissed.) Here’s a fantastic study on all birds which appear in the epic.

Vulture constellations and planets: Lyra (including Vega), Shani, Anuwanayuman, Kurumuyuman, etc.

The Greek queen Phene, who Zeus turns into a Bearded Vulture (yes, Zeus has a thing for turning people into birds).

Nasr

More on sky burials: The dakhma, or Tower of Silence, for Zoroastrians (refer to the Parsis of India); for Celtic peoples, particularly the Celtiberians; and for Bönpo and Buddhists—Vajrayana Buddhists, specifically—of Tibet, Mongolia, Bhutan, parts of India (Sikkim and Zanskar), and neighboring regions. Vultures play a HUGE role in this funerary practice. I honestly want to have a sky burial when I die; it sounds more promising than being pumped full of chemicals and placed six feet under, sealed away in a box, to slowly rot. Might as well go back into the cycle of life.

In Bön, Buddhism, etc., vultures are referred to as manifestations of Ḍākinīs (sky dancers), or female spirits/deities/angels (in some cultures, Ḍākinīs are demons, but this doesn’t seem to be the case here). Beliefs and funerary practices vary depending on the location, ethnic group, and religion or religious branch, so some simply view the dead body as empty and see feeding it to the vultures as both a charitable and ecological act, whereas others believe that the soul remains with the body for 3 days (and it can take a soul 49–100 days, sometimes even as long as 7 years, to be reborn), and the vultures, as Ḍākinīs, help carry the soul to the heavens/enlightenment/a new life, usually on days 4–10 (which is typically when the sky burial is held).

Milarepa and Drüpthob Tashi Rinpoche

The Bearded Vulture as the Huma bird (هما) and a possible version of the mythical Phoenix.

Vultures in the Tanakh and Torah: The Eurasian Griffon Vulture, aka נשר מקראי (Nesher Mikra’ei); basically, the Griffon vulture as Nesher; the Bearded Vulture; and the Egyptian Vulture.

One of the names for vultures in Zulu is Izingwony zenkosi, ‘Birds of the Lord/King.’

Vultures as lenong among the Tswana.

Duga (‘The Vulture’), a song among the Mandé peoples of Western Africa, particularly the Mandinka and Bambara.

The Asakyiri, one of the eight major abusua (clans) of the Akan peoples.

Cocopah and vultures (see the vulture glyph of Cerro Prieto), creator god twins Sipat and Komat.

Condors/American vultures and Teratorns as possible inspirations behind certain variations of the Thunderbird.

The California Condor among Indigenous Peoples of western North America. Like other condors (i.e., the Andean Condor and King Vulture, who, together with the California Condor, make up the ‘condor clade’ in Cathartidae (see the document on defining vultures for more info)), this species has an ancient relationship with Indigenous Peoples stretching back millennia, and holds a sacred place in various cultures. For example, California Condors are prominent figures in Chumash rock art, belief systems, cosmology, and rituals, and their feathers are traditionally used for various ritualistic and accessory purposes.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Back to the vultures-and-eagles topic, many vulture species easily outsize eagles, and even the largest eagles look small next to a condor or a Griffon Vulture. In fact, at least five vulture species are generally listed within the top ten largest living raptors, and they are usually the top five. Contrary to popular belief, many eagle species are facultative scavengers, and they will feed on carrion if given the opportunity; but when vultures arrive on the scene, the eagles will often either step aside or be shooed away, especially if the vultures outsize them. While they lack the feet, talons, and other characteristics and skills which make eagles such powerful hunters (and fighters), vultures more than make up for that in size, soaring capabilities, powerful digestive tracts, beak strength and sharpness, sociability, and, above all, intelligence (besides being social, compared to many other birds of prey, vultures have waaaayyy less space in their skulls and brains taken up by senses (eyes and ears, which take up SO MUCH space in an owl’s skull ghffhhffhf) and instinctual behaviors and responses (hunting), and so there’s much more room for them to observe the world around them, acquire new, learned behaviors, and be playful).