#Why This Economist Wants to Give Every Poor Child $50

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

ezra klein

One of my longtime obsessions as a policy reporter is the question of wealth. Most of American politics, most of American economic policy, I would say, is about the question of income — what wages look like, whether they’re rising or falling, for whom. When we talk about inequality, we’re typically talking about income.

But wealth is as important — I think maybe more important. We don’t measure it as well, but it says more about what a family, what a person can actually do under duress. It says more about how they can invest in their future. It says more — knowing their wealth can often tell you a lot more than their income can — about the long-term prospects of that family.

And wealth has this other quality, again, different than income, which is that it is where the past compounds into the present, where injustices of the past compound into the present, where the benefits of the past, the privileges of the past compound into the present. Wealth is where the long story of a family or a country makes a reality of the moment.

And for that reason, it’s uncomfortable. Wealth is uncomfortable because what does it mean to inherit? What does it mean to ask people to pay up for the sins of those who came before them? But on the other hand, much more so than income, if you don’t do anything about wealth, it just compounds, and the inequalities of a society go greater and become more present every single day.

So for all those reasons, I’ve long been interested in policies that would do something about the wealth gaps we have.

Often, what we do is we make policy to make wealth inequality worse. In the time, I’ve covered politics, we’ve made the estate tax a lot looser. We’ve made the thresholds beneath which it doesn’t apply much higher. You can pass down millions of dollars before you get taxed now.

We also have just a ton of tax policy meant to help people build wealth, which is great. We help people buy homes, and we help people go to college. And we help people do all these good things. The problem is you can only get that policy if you have some wealth to put into these advantaged accounts in the first place.

What we don’t have a lot of is policy that helps people who don’t have wealth build it. And so I’ve been very intrigued by this idea that the economist Darrick Hamilton and others have put forward called “baby bonds,” which would be this proposal to simply give people wealth — everybody. Now, not everybody would get the same amount. You get a lot more if you were poor than if you were rich, if you did not have wealth as a family than if you did. You would not be able to use it for anything. It’s circumscribed. It’s a wealth-building policy, not just a policy to help people spend.

But more so than anything else out there, it has this potential to all in one swoop really shift the wealth distribution of the country, really make sure that everybody has a chance to enjoy the benefits of wealth as opposed to that being something that is reserved for those who got it from generations before them but that those who did not have that luck simply are left without.

Darrick Hamilton is a professor of economics and urban policy at The New School. He served on the Biden Sanders Unity Task Force and was an adviser to Bernie Sanders. His ideas have been picked up into lots of pieces of federal legislation, and baby bonds, in particular, has been introduced by Cory Booker and Ayanna Pressley in Congress, not in its exact form of his but in a pretty close one.

So this is a policy actively under consideration. It’s something you could imagine passing at some point in the future if it were something Democrats prioritized, if it were something that they wanted to make the thing they did if they got power again. So should they? That’s what I wanted to talk to Hamilton about. As always, my email [email protected].

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Darrick Hamilton, welcome to the show.darrick hamilton

Thank you, Ezra. Pleasure to be on with you.ezra klein

We talk a lot in American politics about income, about wages, but something you write that sticks in my head is that, quote, “Wealth is the paramount indicator of economic prosperity and well-being.” Why?darrick hamilton

Think about what you can do with wealth that you can’t do with income. If you have a child that’s about to enter college, chances are your income is not going to be able to afford the choice to send that child to any school that they could actually get into. Some schools just simply might be too expensive.

If you’re faced with a legal challenge and you want to hire a high-priced attorney, the cost will be such that you will have to use some wealth, and income probably couldn’t afford you that attorney. We can think of other things as well.

So even aside from economic security, if you want to do things with your life, suppose I realize that my passion isn’t to be a professor. But I really have this innovative idea, and I want to bring it to market. Well, if I have capital, I’m better positioned to bring that idea to market. If I want to move and purchase a house somewhere, basically the point is that wealth affords you economic agency in ways that income does not.

Income is largely used to pay your expenses that happen on a periodic basis, whereas wealth gives you the ability to withstand shocks and the ability to make investments. Ultimately, wealth gives you choice in ways that income does not.ezra klein

There’s a line I’ve seen you use that that brought to mind, where you and co-authors talk about wealth as being a way to fully participate in the market. What do you mean by that?darrick hamilton

Think about income. If you are a worker, you can’t just simply decide that you want to leave your job and do something else. But if you have wealth, if you have a stock of assets, it gives you the freedom, the choice to, really, negotiate with whatever it is you bring to market, be it your labor, or your innovation, or some ideas. So wealth with that stock, that provides you, really, agency to make choices.ezra klein

So I think people, particularly who listen to this podcast, are probably somewhat familiar with looking at the American economy through the lens of income and inequality. What changes, either in the data or in the distribution, when you begin to look at it through the lens of wealth inequality?darrick hamilton

Wealth is so concentrated in the United States. Very few people own a great deal of the wealth, and of course, if we look at race, that becomes even more dramatic. So if we compare inequality and domains of income versus wealth, essentially there is no comparison. We can cite statistics, but the gist of it is very few people own most of the nation’s wealth.ezra klein

Well, let me cite some. You cite numbers from 2019 that suggests that the top 10 percent of households own about 70 percent of all wealth, 70 percent, and so that’s twice the net worth of the bottom 90 percent of households combined. This is one of those places where, I think if you marinate in it for long enough, you begin to really feel the unfairness in the economy.

For income, if you want more of it, you have to go out and work for it. You have to go lift a box or have a new idea or write marketing copy or something. But wealth isn’t like that. What you’ve got to do to get more money from wealth is just let your money go out there and make money on its own.

So the number here that, I think, is really striking is real household income, the money people work to get, it grew by about 30 percent between 1989 and 2018. The S&P 500 grew by about 400 percent. So if you’re working a job and getting raises, you can make more money over decades. But if you just had enough money that it could sit there in the S&P 500, it went up by multiples, and you didn’t really have to do anything new to get that at all.

So this gets to something that’s become very famous in policy circles in the last couple of years, which is Thomas Piketty’s famous R is bigger than G equation. So I was hoping, for folks who aren’t familiar with it, you could walk through it.darrick hamilton

R over G, all right, so —ezra klein

You sound excited already. [LAUGHS]darrick hamilton

The rate of return to capital has grown and continues to grow at a much faster rate than overall growth, and that is how society has been structured. And if you don’t have interventions from an entity like the government sector to allow for some redistribution, oftentimes due to tax code, then you end up in a perpetual cycle, where those that have the benefit of capital continue to grow their capital.

And then here’s the other point. That growth rate and capital certainly can transform political situations to benefit capital in the first place. So in other words, it’s not just economic growth that becomes compounded. The power associated with that increased wealth translate into ability to influence the political structure and system so as to have a feedback to grow your wealth even more.ezra klein

Yeah, I was going to get into this later, but maybe we should get into it now, which is that I think can be easy to hear this conversation about wealth and markets and think of this as an automatic process of capitalism. But even putting aside the way we structure markets, there is a huge amount of tax policy — I think the estimate I saw on one of your papers was over $700 billion a year — that is designed to wealth build. And on the one hand, that policy is facially neutral. It’s there for, in theory, anybody, but you need to have wealth to use it.

So do you want to talk a bit about what the tax code is doing here and the way we are manipulating, increasing, and advantaging wealth in the tax code?darrick hamilton

Yeah, the extent to which our tax code incentivizes wealth and capital growth, it centers on existing wealth and capital growth. Now, it need not be that way. We could use the tax code in a way to promote new wealth.

There’s the famous study called “Upside Down” that came out of Prosperity Now that shows that we spend about in excess of $700 billion in promoting asset development in the United States. And what are things associated with asset development? The different ways in which we tax capital gains versus wages, the different ways in which we treat homeowners versus renters — so you’re able to deduct the interest payments on your mortgage from your taxes whereas a renter doesn’t have that access.

So we may even think, as a society, that’s a good thing. Wealth is good for society. But the problem is to whom that tax code benefits. So the more accurate estimate of $700-plus billion: About a third of that will go to people earning over $1 million. The bottom 60 percent of earners will receive about 5 percent of that distribution.

So one could reimagine a tax code that spends similar amounts of money but does it in a more distributionally fair way. Because, as we’ve been talking, a lot of that is associated with having existing capital in the first place. So the government is strategically directing public resources in a way to promote even greater growth of those that have wealth to begin with.ezra klein

And I want to get at one of the dynamics in this, because a lot of this is very well meaning.

So there’s a great statistic in one of your papers about how fewer than 3 percent of Americans have what are called 529s, or Coverdell accounts, which are these tax-advantaged accounts to save for education.

And it’s great, right? Helping people put money away for kids’ college in a tax-free way, helping them build for the future, you don’t have to be running any kind of scheme to make America unequal to think that would be great.

But most people don’t have them because most people can’t save that much money in them. And so I think we’re used to thinking about tax policy as being unequal when it’s designed unequally. But you can have a policy or accounts that are totally neutral. Anybody can take advantage of them. But if you don’t have money to put into them, you can’t, and so in effect, they become a way that people are pretty wealthy can keep a lot of money tax free that, if you are not that wealthy, you don’t have access to anything like that.darrick hamilton

Fundamentally, wealth begets more wealth, and if we have a society that uses the tax code the privilege existing wealth, that only enhances that framework, that equation. But again, if we could reimagine the tax code, there’s nothing wrong with promoting wealth for the American people. The problem is how we do it and to whom it’s distributed.

So if we set up structures, incentives, and straight-up grants that allow people to get into an asset that can passively appreciate in a more egalitarian way, that would be better. That same amount of money could be used to facilitate a down payment for somebody to get into homeownership who otherwise wouldn’t get into homeownership. And it’s still growing the nation’s saving and wealth but doing it in, what I would say, a more fair, just, and even productive manner.ezra klein

I’m going to put a pin in that because I want to get to that policy, but I want to go through a couple more pieces of the wealth context first. And one thing here that I want to be careful about — we keep talking about wealth as if it’s one thing, and the examples I’ve used so far are things like stocks and homes. But the composition of wealth, what we measure as wealth, includes a lot of things. And the composition of what wealth people have changes as you go up and down the class ladder.

So could you talk a bit about the different types of wealth and how the wealth that people in the working class have, if they have it, tends to be pretty different than people in the richer segments of society?darrick hamilton

That’s right. If we get into issues of diversified portfolios, we know that it’s better to not have all your eggs in one basket. But one needs to realize that if you have a little egg to begin with, it’s hard to spread it amongst many baskets.

So in the American case, the asset that most people start out with — and again, it’s for those individuals that are able to get into substantive ways to generate wealth and assets — it’s often a home. As such, the composition of their wealth is often primarily in a home in a large percentage way. But as you grow your wealth, you’re able to use that additional wealth to diversify your financial portfolio. Then you start to get into things like stock ownership and potentially even business ownership.ezra klein

And that gets us something, I think, important here, which is, at the beginning, you gave the example of wanting to start a business, or sending a kid to an expensive school, or maybe needing to get a lawyer. If you’ve got a bunch of stocks sitting around and your wealth is in stocks and you need to sell some of them to do that, so be it.

If your wealth is in your home, it’s not that that isn’t real. You can sell your home. But there’s a lot that comes along with selling your home, from having to move to another home to it maybe being a very emotionally important part of your life and the place where your kids grew up. There is a difference, I think, between having your wealth tied up in the place you live and having it invested in a hedge fund.darrick hamilton

If we look at financial wealth as the sole category, these disparities that we started out describing in the beginning, they grow even wider, which is your point. We also think about the benefits of a home, you really need a residence, some place to actually live, and also the attachment that comes along with social ties.

But we offer various other amenities with your home as well, such as the school. The quality of your school is attached to the neighborhood that you live in. Those that can afford affluent neighborhoods in a home to match often are in better school districts so that their kids even end up with a better hand when they become an adult and begin the process of wealth building.

[MUSIC PLAYING]ezra klein

We’ve talked here a bit about wealth inequality and wealth composition. Tell me about the Black-white wealth gap.darrick hamilton

Now, that’s dramatic. The Black-white wealth gap is such that the typical Black household throughout American history has rarely had more than a dime for every dollar as the typical white household, not just wealth as an outcome but its functional role, what it can do for you. So we end up in locked-in inequality, and what makes it more pernicious is that locked-in inequality is often defined by the race that you’re born into.ezra klein

And so this is probably a point to ask. Are we talking here about means or medians? And how are those two measures different? And what does looking at one of them get you that looking at the other one misses and vice versa?darrick hamilton

If we were to look at mean — the differences we’re citing are even more dramatic. If we were to look at the mean wealth difference, Black people as a group own about 3 percent of the nation’s wealth. Black people make up well over 12 percent of the nation’s population but own about 3 percent of the wealth.

I think a fair number is to use the median if we’re thinking about differences across race because then you want to look at what’s typical about a Black experience versus a white experience. But if we look at the mean, the mean is more dramatic because America has a wealth inequality — period. So we have a problem with a concentration of wealth regardless of race. But it becomes more pernicious when we look at race.

We have a small few that own an enormous amount of our nation’s wealth, and that small few is overwhelmingly white. So we can have racial justice, where we would have a more fair distribution of wealth, and that would be great. But that still wouldn’t achieve economic justice. So in the dimensions of wealth, we need to be concerned with both economic and racial justice.ezra klein

Just imagine, as a thought experiment, we passed a policy that really solved or deeply narrowed — and we’ll talk about a policy like this — the median wealth gap. So the typical Black household, the typical white household, now they look pretty similar or much more similar, at least, from wealth but does nothing really on the mean wealth gap because your Bill Gates and your Elon Musks and so on, they’re unaffected by this policy.

And so on the one hand, you have really dramatically changed the wealth gap on one measure and barely changed it on another. What have we solved in that world? And what haven’t we solved?darrick hamilton

We haven’t solved economic justice. Now, we’ve redressed racial justice, which, again, would be no small feat. And if I were to flip your framing slightly, Ezra, and say we can close the mean racial wealth gap, hypothetically, by creating simply a class of Black billionaires, so that the mean distribution across race was equal. But that would still leave large racial disparities between the typical experience. In other words, a handful of Black billionaires would not solve our problem but could, at least in theory, close the racial wealth gap.

I’ll add one other thing to make the point crystal clear. The mean wealth of a white family in America is close to $1 million. We know that the typical experience of a white family is not a millionaire experience, but that’s because of that high concentration of wealth that drags the distribution in a skewed way towards $1 million. The more typical experience of a white household is in the hundreds of thousands range. I believe it’s closer to $200,000. So if we were to use the mean and not the median, we would not exactly be using the accurate pinpoint to understand the typical experience between a Black and white household.ezra klein

One of the reasons I think the Black-white wealth gap is unusually important to focus on is a question of racial justice is that it’s where the story of our past compounds into our present. And you’ve done a lot of work on both the shape of it now but the causes of it. So how do you understand how America ended up with a wealth gap like we have?darrick hamilton

Many of us are well familiar with our history, and we know that America has had a sordid history in its treatment of Black people, beginning with slavery. And it’s been characterized as the original sin of America, where you had people literally living in bondage and serving as capital assets for a white landowning plantation class.

We also know — and we led this conversation up — with how wealth is generated. It’s generated mostly passive. We know that it’s intergenerational, that households that have children are able to bequest to their children a capital foundation that allows them to not only have wealth but grow their wealth. So we understand how wealth is created, and we understand the history of America is such that Black people started out in bondage.

And then another pivotal point that should be made is that a white asset-based middle class didn’t simply emerge. It was public policy — policies like the Homestead Act, policies like the G.I. Bill, establishments like fair housing authorities that facilitated long-term mortgages at very low interest rates that provided the capital and the structure so that white families can get into things like a home and, in the case of a G.I. Bill, a college degree without the albatross of educational debt to get into a managerial or professional occupation.

Ira Katznelson has a phenomenal book called “When Affirmative Action Was White,” which really lays this out. What Ira Katznelson also describes in this book is the ways in which that policy was designed — or that set of policies — were designed, implemented, and managed that benefited white people and, to a large extent, excluded Black people.

So let’s give an example. Imagine a Jim Crow context for which one is trying to apply their G.I. Bill to purchase a home in an area. Well, the choice said that you have to purchase a home is much more limited if you’re Black. The access to go to a bank and receive a loan to provide a mortgage associated with that initial capital is very different if you’re Black.

I think the estimate that Ira Katznelson offers when we think simply about higher education and not even homeownership, that the G.I. Bill provided enough capital for Americans to rival that that we spent on the Marshall Plan that played a large part in rebuilding Europe.

So this surge of government resources enabled a population and also enabled institutions that benefited white people at the exclusion of Black people.

When Black people were able to accumulate assets, when they were able to overcome circumstances and actually accumulate wealth, it never received the political codification to be immune from malfeasance, terror, threats and outright theft, the ways that white people property ownership was afforded.

A big example would be Tulsa, Oklahoma when we had the Race Massacre in which a community that was at least working to middle class was decimated overnight.

And then, of course, this was not isolated. There were many examples, where physical destruction, even if it’s not leading to the actual physical terrorism that decimated Tulsa, Oklahoma for Black people, the threat of violence, the fear, the threat that, if you don’t engage in a certain way, if you don’t act a certain way, if you are not kept in your place, you literally could lose your life. That has impacts on a community and on a population’s ability to generate wealth.

So this is our sordid history. But what is important for this conversation that we’re having, Ezra, is that the paramount indicator of not just economic security but economic agency in one’s life has been structured in America through public policy such that we have this large gap of about one dime for every dollar, which is an implicit economic indicator of our historical past.ezra klein

One statistic I’ve seen you use that I find unbelievably striking here because I think the myth in America, the belief, oftentimes, is, look, you get a college education, get a job, you get ahead. And that’s available to anybody now, even if it always hasn’t been.

But something that you and co-authors have found is that households in America headed by white high-school dropouts have more wealth on average than households headed by Black college graduates. That’s pretty remarkable.darrick hamilton

And that’s the beauty of trying to describe that we have structural racism in America. You can simply point to descriptive indicators that we all associate as the keys to success and find out that not only do we have disparities across race at various indicators of whether you’re married, not married, highly educated, not highly educated, formerly incarcerated, never been incarcerated. But these disparities grow as we move up into higher status indicators.

So the disparities across wealth get larger at higher levels of education. The disparities across wealth don’t subside when people get married. They actually get larger. With the statistic you cited earlier, you can look at the highest status indicator for Black people, like a college degree, like being married or whatever the domain we want to look at, and look at the lower indicator for white individuals and see that, in something like wealth, the disparities are often such that the white person is better off in wealth than the Black person, even though the Black person has the highest status indicator. It dispels this myth, this notion that all you have to do is do these things and you’ll be fine.

Of course, within group, more education is associated with better outcomes, but across groups, the disparities remain and even get larger. And that’s not a coincidence. That’s a structure.ezra klein

One point you’ve made is that one thing you see in the data is that a reason it’s often hard for Black families to build wealth — and this gets to this whole broader context you’re describing — is that, as they do build wealth, there are more people who need their help in their communities and their families, and so there tends to be more — if you’re somebody, who you’re part of a middle-class or upper-middle-class family and you get some money, odds are that people around you don’t need it that much.

But if you’re somebody who’s the only person in your family who’s got into college, and it was a huge effort for the family to put you through college, and now you’re a doctor, let’s say, but a lot of people around you don’t have much and they need help with medical bills, or fall behind on rent, or whatever, and you need to help them, that puts a brake on wealth accumulation that somebody from a wealthier family just doesn’t have as much of.

I was curious if you could talk a bit about that dynamic and what you see of it.darrick hamilton

And of course, that’s personal. I’ve been able to acquire resources in ways that other people in my family have not, both immediate as well as extended family, and I well understand the demands to want to provide for others so that they can have a good economic experience and not be vulnerable. Altruism isn’t the problem. That’s a good thing. But it’s a problem that these structures of inequality extend well beyond the individual but have large spillover effects as well.ezra klein

So one thing I take from all this is that it’s just really hard to change wealth distribution, that you actually need real policy to do it. And this is something we were talking about earlier. We have put a lot of policy into place to do it. We have all these tax breaks. We’ve also cut the estate tax a lot over time, so we’re taxing wealth a lot less than we have at other points in American history. But you have a pretty big policy idea that has been taken up in Congress that would do quite a bit here called baby bonds, so tell me about the baby bonds concept.darrick hamilton

Baby bonds just recognizes the ways in which wealth is generated. Wealth begets more wealth. We know that the difference between low-wealth and high-wealth individuals began with capital.

So what baby bonds does is it provides a birthright to capital. It says, irrespective of the economic situation in which you’re born into, we will endow you with capital, such that, when you become a young adult, you can purchase an asset that provides that passive savings, that passive appreciation, where you get economic security. You get economic agency that comes along with wealth as a birthright.ezra klein

So how much capital are we talking about?darrick hamilton

Conceptually, enough so that the individual, when they become a young adult, can be able to get an education without debt, have a down payment to get into a home or some capital to be able to bridge with a business loan to start a business. That’s the idea.

The program is structured such that the average account would be about $25,000, but they could rise upwards to $50,000 for those that are born into the most wealth-poor family.

Now, that’s the policy described at the federal level. If we think about state-level policies, where they don’t have the purchasing power that the federal government has, they are constrained in an annual way based on their budgets. We’ve seen places like Connecticut be able to come up with an endowment of about $3,200 for all Medicaid-born babies.

So Connecticut, Washington D.C., and various other states, they’re not waiting on the federal legislation. They’re beginning to try to redress intergenerational poverty, given the constraints of their fiscal budgets, with as little as $3,200 at birth. And that $3,200 at birth, it will be managed similar to other state pension programs, where the treasurer of those states or those localities try to grow the accounts as large as possible. And there are estimates that, in the case of Connecticut, a child born into poverty, as measured by being a Medicaid birth, could have about $10,000 when they become a young adult to contribute towards some down payment, some nest egg, so that they can build wealth.ezra klein

Let’s hold on the bigger proposal, the federal proposal, for a minute, the one that could be up to $50,000 for somebody born into the most wealth-poor households. So as I understand it, there’s strictures on what you can use that money for. You can use it to go to college. You can use it to buy a house. You couldn’t use it, I guess, to invest in Bitcoin, or to fund your gaming habit or to buy gym membership or just to help out your family members. I don’t want to put this all as leisure spending. Why? Why not trust people to spend the money the way they need to spend it?darrick hamilton

And let’s be fair. This policy will not be — I’ll use this word again — the panacea to redress all of the economic insecurity that we have. There is the difference between income and wealth, and both are critical and important for individual, family, and community well-being. So the program is restricted not to be paternalistic but to ensure that it’s being promoted in a way to actually build wealth.

We gave the example of being born into families that are not so affluent, thereby might very well require needs on individuals that are able to attain social mobility.

If you would have offered me a baby bond when I was a young adult, when I was coming into the working age of my life, graduating from college, graduating from school, it’s likely I would have had a relative who could have used that money in order to avoid some really detrimental circumstance, like being evicted, like being able to pay a light bill, like being able to address some of their immediate income needs.

Now, those things are critical and important, and I would have been happy to be able to make those contributions if I had the money. However, it wouldn’t have grown my wealth.

So I think we need to restrict the accounts not because we don’t trust people to make astute decisions for themselves, because we need public policies that are really aimed at the attribute for which we want to address. That’s the whole purpose of why you might want to restrict it.

[MUSIC PLAYING]ezra klein

So in the first part of our conversation, we talked about the size of wealth inequality in America. We talked about the Black-white wealth gap in its mean and median forms. Some analyses have been run on this idea. What would this do for those? Which gaps would it close, and which gaps would it not?darrick hamilton

Naomi Zewde, she has this great simulation study that projects the impact of baby bonds on the Black-white wealth gap, and she calculates that, for recipients of the account, the young adults that would actually receive the account, it would cut the racial wealth gap in half, by 50 percent. And that’s one generation.

Imagine what it can do for subsequent generations. It can trend us towards closing the racial wealth gap. And we’ve been focusing on race, but there’s a lot of wealth-poor white individuals in this country as well. And they absolutely would benefit.

So to me, this would be a program that is an automatic stabilizer in the sense that not just for the immediate recipient generation but future generations as well and to the extent that capital grows and generates inequality in America. We have a policy that, in perpetuity, trends us towards a society that affords people regardless of the income that they’re born with, the race in which they’re born to have access to something as critical as capital so that they can actually have an opportunity to build wealth.ezra klein

So the numbers we’re talking about here for the poorest families are pretty big, $50,000, and I think it is reasonable for somebody to hear that and say, yeah, it would be nice. But there’s no way we can afford to functionally have I like to think of this as a universal basic wealth program. What would the cost of it be? And how could it be paid for?darrick hamilton

So I got two lines of critique. One is the universal basic wealth aspect. It’s universal in the sense that everybody would have access to wealth. It would not be basic in the sense that everybody wouldn’t get the same level of wealth as an endowment.

But the main question that you raised, and we should address it. The cost of the program would be $100 billion in total. $100 billion seems like a big number. $50,000 to the most wealth-poor person seems like a big number, but we need to put that number in context.

Let’s put that number into context of one of the ways in which we began this conversation. The Federal Government is already subsidizing the assets of American people to the tune of well over $700 billion a year, so we actually can afford to pay for this. We actually have already spending in effect that’s promoting asset development.

So with the existing pool of resources that we’re using in the tax code, we could take a portion of that and do something that’s dramatic as redress these problems that we started off talking about, this massive wealth inequality that we began with, this racial wealth gap that has been structured in an immoral way since the inception of our country.

So to me, there’s a lot of good news for $100 billion. We really can achieve an egalitarian society that affords everyone the benefits that come along with wealth.ezra klein

I think one worry here would be — so imagine we pass it tomorrow. You have this generation of kids, when they turn 18, they have $50,000 or $50,000 that’s been growing in the markets, more or less, depending on where they started out. And now, all of a sudden, you have this profusion of, say, higher-ed educations that there’s this whole generation that’s about to graduate with more money, particularly people who maybe wouldn’t have had access to places like them beforehand. Or that all these people have money burning in their pockets and they want to try to convert it to money they can use, so somehow maybe they could pull in a house, but they can’t spend it on many things.

You can imagine two things happening here. I think one is a lot of predation, and the other is inflation. And I think that’s a particular concern in higher education, where we’ve seen that before, where, if there’s a lot more money people can suddenly spend on higher education, the higher-ed organizations raise prices and figure out ways to part people with that money without necessarily giving them a lot more for the dollar. So when you’re talking about a big bang policy like this, how do you make sure it doesn’t just get eaten up by highly informed, clever, and not even always malicious, just self-interested actors?darrick hamilton

Ezra, I think you’re spot on with that question, and I think it’s a huge concern. We know history has taught us that two forms — one is, if we know there’s going to be a cash infusion into a population, a great deal of individuals, corporations, and other institutions are going to figure out ways in which they can usurp some of those resources in order to benefit themselves. And that potential biggest predator in this program very well could be universities and colleges that simply inflate their tuition to absorb the accounts in a way that it doesn’t have a real effect.

So to redress that, you will definitely need to include financial protections in the program. One of the benefits of, say, the investments going towards a home, it wouldn’t be enough resources to literally purchase a home. It will require some form of a mortgage, so through federal protections to define what are the criteria to receive that mortgage and the criteria by which banks and other financial institutions could issue that mortgage, that becomes another check by which government can regulate the program in a positive way.

Similarly, if you go get a business loan, you can’t get a loan for just any business. There’s some criteria. So that becomes another implicit check to redress some of the potential financial malfeasance, especially if government regulates the type of loans that can be coupled with the account.

Let me also say that it would be great if this program was coupled with other programs, like tuition-free public education. I think, in the 21st century, we need things well beyond baby bonds. We need a package of public goods aimed at ensuring that people have the essential resource without which they simply are vulnerable, and capital is clearly one.

And in the 21st century, not just a high school degree, but a college degree becomes another essential element. So if you had tuition-free public universities, that would be a constraint on tuition costs that could avoid some of that inflation that you’ve been describing.

And then one other feature of the program, I don’t think we should require people to use the accounts once they turn 18. Indeed, there should be provisions for an account that provides a normal rate of return and be accessible for when the child becomes an adult and also is ready to use the account.ezra klein

So another criticism is wealth inequality is bad. Wealth concentration is bad. But for everything we talked about earlier, there are distinctive dynamics to the Black-white wealth gap that reflect specific historical horrors visited upon Black Americans. And so a race-neutral policy simply isn’t the right way to approach that. How do you think about that?darrick hamilton

I’m an advocate for reparations. I think reparations and baby bonds address complementary things but not the same things. Reparations is a retrospective racially just program that does two things.

It requires atonement. It requires truth and reconciliation. It requires the federal government to take public account and atone for the state-complicit malfeasance that have taken place in the past and led to the conditions that exist today.

So that’s not empty. That’s valuable because a lot of the rhetoric by which we make policy today is grounded in narratives and norms, and it’s often grounded in narratives and norms that position Black people as deadbeats, as welfare queens, as predators themselves, as undeserving, undesirable, as a drain on public budgets. Now, of course, that doesn’t just affect Black people. That limits our ability to deal with white poverty as well.

So that reparations leads to a different framing and understanding of both poverty and inequality, that not only offers dignity to a population that has been stigmatized, that has been demonized throughout American history, but also creates new pathways and understanding in a more accurate and a more just way of thinking about poverty and inequality, not just for Black people but for all people going forward. Whether we’re ready for it today or ready for it tomorrow, we should commit to it and commit to it as a movement because it is the right thing to do.

That should be reason enough. But it will not be enough to really provide for the economic security and the access to wealth in a forward-looking way. It will redress the past, and it will put Black and white people on a far more even keel in both economic and political contexts.

But we know what capital does. Capital consolidates, iterates, and it excludes. In other words, wealth begets more wealth, and wealth builds upon itself.

So even if we redress the past, going forward, capital will concentrate amongst certain entities in American society, and we need a natural stabilizer. We need an automatic stabilizer. We need a public policy that, in perpetuity, ensures that everyone has access to a capital foundation, particularly in their formative years of being a young adult so as to build wealth. We need to go well beyond subsistence programs, which are critical and necessary but really will not build wealth.ezra klein

Let me ask you about one final example before we wrap up here, which you talk about in your paper, which is SEED OK, the SEED for Oklahoma Kids experiment. They were put in for — at least for a treatment group, a $1,000 into a 529 Savings account, the kind of account we talked about earlier for pretty poor kids, and then they tracked what happened to that treatment group and their parents against groups that didn’t get that $1,000. What did they find?darrick hamilton

There are great lessons from that SEED OK experiment that could inform us about baby bonds. In addition to the wealth building attributes associated with baby bonds, the SEED OK showed us that families knowing that their child is going to receive this endowment when they become a young adult invested more in that child, tried to promote that child to double down on their education.

Children had better grades, as a result, from that endowment than they otherwise would have without that endowment. Children had better outlooks on life. They had higher aspirations, knowing that they were going to receive that account when they became an adult.

The good thing about baby bonds is it has spillover effects well beyond promoting the wealth of an individual that receives the account.

It can literally change the horizon by which poor families and Black families engage with the state. These are groups that are often engaged in punitive ways with the state — where the state is imposing a fine, where the state is saying you can and can’t do this.

If the state were to offer an endowment, I think it will promote civic engagement.

I think that Black families, poor families, and other marginalized families will see the state in a different light, and it will lead to more civic engagement, which will benefit us all as a society.

It will also change the horizon of that child with regards to things like education. If you’re going to receive an endowment, you very well might be incentivized to invest in attributes like schooling such that you’ll benefit to a greater extent from that endowment when you become a young adult.

In addition to changing the horizon by which a family thinks of the state so as to promote civic engagement, it also can create more touch points in a positive way by which the state can engage with families in a productive way.

I suspect that prenatal care will become greater utilized amongst low-income families as a result of baby bonds. If an expectant mother understands that this account is being established, well, it creates an opportunity where we literally could send out literature promoting these are the types of steps that you should pursue in order to have a healthy child, which could promote more healthy children and greater lifestyles going forward.

But it need not end at prenatal care. Just like Social Security, where we get estimates of our Social Security accounts periodically, and it provides a point in which the state can send literature and information to households, we can use the point of baby bonds to have positive interface of the state and the population so as to promote more healthy living for the recipients and our society at large.ezra klein

I think that’s a great place to end, so I’ll ask our final question. What are three books you’d recommend to the audience?darrick hamilton

Three books, well, you heard me talk about “When Affirmative Action Was White” by Ira Katznelson. That is foundational for me. It’s foundational for me because it demonstrates what government can do in order to promote the human rights of all of us, to promote a great society for all of us. The lesson from “Affirmative Action Was White” was that, if we’re going to do it this time, we need to make sure that we design, implement and manage the policies not in an exclusive way but in an inclusive way.

The second book, which is foundational for me, is “Racial Conflict and Economic Development” by Arthur Lewis. Anybody trying to understand the intersections of politics, economics and identity group stratification or racial disparity, I highly recommend that you read that book.

And then finally a book that I’ve read more recently by Natalie Diaz, who is an Indigenous poet. The book is called “Postcolonial Love Poem.” Natalie has this incredible way of presenting social theory in prose in ways that link people to the environment. It has had huge impact in my understanding about society in general, and it did it with poetry in a way that words themselves matter in our understanding and are critical if we want to come up with social policies to move to a better society.ezra klein

Darrick Hamilton, thank you very much.darrick hamilton

Ezra, I appreciate you so much. Love your podcast. Thank you.

0 notes

Text

Taking UBI seriously part 6: Dolan

This is the sixth in a serious of posts looking for a serious proposal for universal basic income. Previous posts:

A Budget-Neutral Universal Basic Income by Jensen et. al.

Basic Income – Why and How in Difficult Economic Times: Financing a BI in Ireland by Healy et. al.

Andrew Yang’s proposal as part of his presidential campaign

A variety of indicators evaluated for two implementation methods for a Citizen’s Basic Income by Malcom Torry

It’s Time to Think BIG! How to Simplify the Tax Code and Provide Every American with a Basic Income Guarantee by Allan Sheahen

In this post I will be looking at a UBI proposal by Ed Dolan, an economist and Senior Fellow at the Niskanen Center. He set out his plan in a series of posts on the EconoMonitor blog (part 1, part 2, part 3) . The meat of the proposal is in part 2.

tl;dr: Not a serious plan. Vague on some of the tax measures, penalties to seniors on Social Security make the plan politically untenable, and worst of all, it’s a massive transfer of wealth AWAY from the poor

Like most UBI proposals, Dolan’s idea is to replace most current welfare spending, although he would leave health care spending (Medicaid and CHIP). Unlike most proposals, though, he replaces this with a benefit that falls far short of enough to live on, which calls into question whether this should be called a basic income at all.

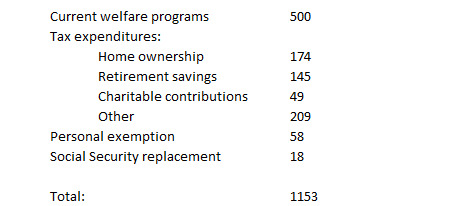

His plan, in brief, is this: eliminate all federal means-tested welfare, except for health care programs. Eliminate some middle class entitlements such as the mortgage interest rate deduction and the personal exemption for income taxes. Divide the money equally among all US citizens (including children). Returees get the choice of the UBI or their current Social Security benefits, but not both. The budget is below, figures in billions of dollars.

Excluding those retirees who would rather keep their current Social Security benefits, Dolan figures on 259 million recipients, for a benefit of $4452 per person.

Before I go on to what’s wrong with this, let me mention two things that Dolan got right. First, he left health care alone. Many people who propose replacing the current welfare system with UBI sweep up health care along with everything else, ignoring the fact that if you have $50,000 in medical expenses a year, a UBI of less than that is not going to leave you better off. And second, he gives the benefit equally to children and adults. Poverty is concentrated among children, so if you are trying to make a poverty-reduction program, you should prioritize children. A lot of UBI plans give children either a smaller benefit or nothing.

That said, $4452 per year isn’t nothing, but it’s not credible to call this a basic income if “basic” means “provides for basic survival needs.” Using federal poverty guidelines for 2014 found here, that's 38% of the poverty level for an individual or 75% of the poverty level for a family of four. (Lower 48 only. Guidelines for Alaska and Hawaii are higher.)

And that’s before getting into specific problems with the components of Dolan’s budget, which I will tackle in reverse order.

Most retirees and disabled people on SSI are worse off

Dolan figures that there are about .42 million retirees on Social Security and 21 million people under 65 who receive Supplemental Security Income, most due to disability. His plan is to offer them either $4452 per year or their current benefit, whichever is greater. For most of them, their current benefit is the better deal, so Dolan figures 57 million people will keep what they’re currently getting and be no worse off.

Except that they will be worse off, because of Dolan’s other cuts. They will lose all of whatever welfare they are currently receiving, as well as the provisions in the tax code that Dolan calls middle class entitlements. Every one of those 57 million is going to lose something, because Dolan would eliminate the personal exemption on income taxes. For those 57 million, Dolan’s plan means all loss and no gain.

The AARP is never going to sit still for this, so I think Dolan’s plan is dead in the water on this provision alone.

Vagueness on cuts to tax expenditures

Dolan wants to cut some federal tax expenditures for a total of $577 billion in new revenue, but he’s not clear on exactly what. He leaves out exclusion of taxes on health insurance plans, and then lists $174 billion in benefits to home owners, retirement savings exemptions at $145 billion, and deductions for charitable giving at $49 billion. The rest, which would come to $202 billion, would be a number of smaller tax measures.

But all tax expenditures, leaving out health-related ones, come to much more than $577 billion, so it’s not clear which ones Dolan is targeting. His link to a list of tax expenditures no longer works, but I believe he’s using these figures. Which of them make up the $202 billion in the miscellaneous category? The big ones would be capital gains ($76 billion), the step-up basis of capital gains at death ($66 billion), the child tax credit ($24 billion), exemption of Social Security income ($26 billion), exclusion of interest on state and local bonds ($29 billion), and deductibility of state and local taxes ($46 billion). Those come to $267 billion, and the smaller provisions would add a lot more. Since Dolan doesn’t say which ones he wants to eliminate, it’s impossible to figure who benefits from his plan and who pays.

Current welfare recipients are much worse off

Go back and look at that budget again. It takes $500 billion that currently goes to the poor and divides it up among everybody, poor, middle class, and rich alike. That means, obviously, that a lot less of that money is going to the poor.

To make up for this, Dolan adds another $653 billion and again, divides it among everybody, and again, that means most of it is not going to the poor.

If you’re trying to help poor people, don’t you think it would be a good idea to make sure they’re getting back at least the $500 billion you cut from welfare?

There are, let’s say, 50 million poor people in the US. Depending upon what you count as poverty, you get a different number, but 50 million is a nice round number and good enough for a sanity check on Dolan’s idea. At $4452 each, their share of the UBI payout is $222.6 billion.

Poor people are getting back less than half of what they lose to welfare cuts.

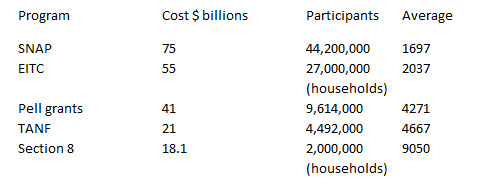

That’s a very rough estimate, but we can check it against data that Dolan had on hand: the report from the Cato Institute that he cited for his welfare numbers. Starting on page 11 of the report, there is a breakdown of the cost and the number of recipients for each program, which lets us calculate average welfare spending per participant. Here are the results for some of the larger programs.

Those are averages, of course, and in particular the number for TANF is not to be taken at face value because only about 25% of that goes to cash benefits. But it should raise some red flags. A thoughtful and responsible person would have done a little googling around.

Median combined SNAP and TANF cash benefits for a family of 3 in 2012 were $869 per month (source, p. 13), which is $10,428 per year. Dolan’s UBI for three people is $13,356, so substituting that for SNAP and TANF, the family is $2928 per year better off. But take away an average EITC of $2037 and school breakfast and lunch programs for two kids at $1203, and the family is now $312 worse off. And that’s before losing WIC, Head Start, Section 8, or any other program they might benefit from.

I have criticized the authors of other plans for not using a tax model to figure out who benefits and who pays, but Dolan couldn’t be bothered to run the simplest check to see if it’s even plausible that his plan works. That’s insultingly shoddy.

Having completely missed this little flaw in his plan, Dolan ends part 2 of his series with this statement:

My purpose here has simply been to show that a UBI within striking distance of the poverty level, as commonly understood, would , conceptually, be affordable without aggressively attacking the fortunes of upper income Americans and without raising anyone’s effective marginal tax rates.

Well you fucking failed at that. Ed Dolan, you are a professional economist with a PhD from Yale. I, an anonymous rando on Tumblr, have only taken one class in economics ever and that was at a second-rank state school. And yet I discredited your work with about two minutes of arithmetic.

That being the case, I feel qualified to say that you are an innumerate nitwit and I wouldn’t trust you to add up a bar tab.

Oh, and if you take away the personal exemption you are obviously raising the effective marginal tax rate for at least some people. Good grief, think about what you’re saying for a moment.

Conclusion: this is a horrible plan that completely screws the poor, and the quality of the economics program at Yale must be pretty awful if this guy is any indication.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Universal Income (project) in Canada - ONTARIO

The so-called Universal Basic Income project is just a bunch of rich people studying poor people to see if giving them more pennies will push them into the job market more.

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/what-is-basic-income-and-who-qualifies/article34795127/

[ image is Kathleen Wynne, the Premier of Ontario ]

|Ontario will provide residents in Hamilton, Thunder Bay and Lindsay with free income, part of the government’s plan to test whether the extra funds will help improve their job prospects and quality of life.

The idea is to give the province’s working poor, unemployed and homeless residents an income to pay for their basic needs of food and housing. (When you pay for your most basic items, have housing, and some stability, it is obvious that those who want more out of life will pursue goals, including entering the job market. They know this. This is not a pure act of humanity.)

About 4,000 recipients will be randomly chosen from the three regions. One group will start receiving the so-called basic income as soon as this summer, and the remainder will be part of the control group, which will not receive any payments, according to a provincial spokesman. A single person could receive up to $16,989 per year. A couple could get up to $24,027 annually.

Opinion: Ontario’s Liberals take a big step to the left

Initially, government officials said 4,000 recipients would receive the funding. A spokesperson later said half of the 4,000 would receive the basic income. Later in the day, the province said it could not confirm how many would receive the basic income.

“One income used to be enough for most families,” Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne said in Hamilton to announce the three-year pilot.

��Now even with two people working, it is tough to feel as though you are getting ahead and it is tough to feel confident that your job will still be yours or even still be around in 10 years, in five years or even less,” she said. (She may or may not be alluding to automation which is a possible scenario as technology advances more and replaces human labour with technological labour - Problem for capitalists who need their workers and people to buy their products, but have no money to do that because of no work that is available, leaving people to go on social assistance.)

Ontario has emerged as one of the country’s stronger economies amid the energy downturn, which has wiped out thousands of high-paying jobs in oil-producing Alberta. However, certain parts of Ontario have struggled for years to recover from the loss of major industries. ( we wouldn’t have this issue though if we didn’t have an economic system based on competition of private ownership. Including basic necessities like water, oil, and electricity.)

The provincial government did not provide details on why or how the three regions were selected. Thunder Bay has suffered from the elimination of forestry jobs and Hamilton has undergone years of economic woes with the decline of the steel industry. (Thunder Bay apparently has one of the highest rates of unemployment in the country. As well as a few other towns/cities in Ontario - http://www.citynews.ca/2016/12/02/list-of-unemployment-rates-in-selected-canadian-cities-for-november/ - for reference.)

Meanwhile, other cities such as Waterloo have experienced strong job growth from the tech sector.

“Technological progress and automation are creating new industries. But they are also creating new pressures and they are putting existing jobs at risk,” said Ms. Wynne.

The project will cost the province $150-million or $50-million a year. About 1,000 individuals will be selected from the Thunder Bay region and 1,000 from Hamilton and the nearby Brant region. The remaining 2,000 will be selected Lindsay.

It’s not just people receiving social assistance who will be eligible for the basic income. The government is also targeting those who are underemployed, earning minimum wage and/or living in poverty.

However, if an individual is receiving income from a job, the government will deduct half of his or her earned income.

For example, if a single person earned $10,000 from a job, the government would provide $11,989 in basic income – the maximum $16,989 minus $5,000 from his or her wages. That recipient would then have a total income of $21,989 for the year.

One economist said the basic income plan could become a disincentive to work, because every dollar earned would reduce the amount of government benefits paid.

“There would be an incentive to get basic income. But then the incentive to earn more through work would be blunted by the fact that each dollar one earns would reduce your basic income by 50 cents,” said Douglas Porter, chief economist with Bank of Montreal, who called it “an effective tax rate of 50 per cent.”

The Wynne government did not say how it came up with the basic-income amount and said it was “something we want to test.”

Chris Ballard, the province’s minister in charge of housing and poverty reduction, said other basic-income projects have shown that the approach improves people’s lives.

“People get a chance to go back to school. They don’t have to work low-paying dead-end jobs. They get a chance to go finish college or go on to university,” he told reporters.

The idea of providing people with a basic income has gained popularity in Silicon Valley and among some tech executives in Canada, who believe that their creations are helping put people out of work.

The provincial government, which will soon hire researchers to conduct the pilot, plans to mail out requests to participate in the program and will include homeless shelters.

The government said it would be examining the impact on health, education and employment over the course of the pilot.

Ontarians who are already receiving social assistance through programs such as Ontario Works or the Ontario Disability Support Program will have a choice of getting the new basic income or staying on their current benefits if they are selected. Anyone who receives other aid such as free dental and prescription drugs would not have to give those up.

It will be at least three years until a decision will be made whether to roll out basic income across the province.

The outcomes for those chosen to take part in the pilot will be examined to see what kind of impact the extra funds will have on their lives. Lindsay will be analyzed for the program’s impact on the entire community.

A separate program for First Nations people living on reserves will be rolled out later this year; however, First Nations people living in the selected areas are eligible to participate in the pilot.

***

What is basic income?

A guaranteed annual income designed to pay for basic necessities such as food and housing. In Ontario, the provincial government will provide income to certain residents who are living in poverty, unemployed, underemployed or working minimum-wage jobs.

Who qualifies?

Only residents from the following regions: Thunder Bay, Hamilton, Brantford, Brant County and Lindsay. A separate basic income plan for First Nations communities will be rolled out later this year.

Where else in the world do basic income pilots exist?

Finland, Kenya, The Netherlands, and Oakland, California.

Are other provinces looking at Ontario’s pilot project?

PEI lawmakers are supportive of a basic income, but the province would need Ottawa to provide the funding.

At this time, the Trudeau government will not support a basic income plan for the country and has highlighted its child tax benefit as a form of guaranteed income for families with children.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cash Aid Could Solve Poverty, But There’s a Catch

Nurith Aizenman, NPR, August 9, 2017

You don’t have to convince Likezo Nasilele that giving people a small but steady stream of cash with no strings attached may be the smartest way to fix poverty.

Just a few years ago Nasilele and her husband, Chipopa Lyoni, couldn’t even afford to feed their four children properly. Then Nasilele, who lives in a rural village in Western Zambia, lucked into an experimental government program that has provided her with up to $18 every other month. In the 2 1/2 years since, she and her husband have more than doubled the money by using it to start several businesses.

“We’ve crossed from poverty to a better life,” marvels Nasilele. “We’re set up now!” Hundreds of other families in the experimental program tell a similar story.

So you’d think Zambian officials would be eager to scale up the program. And to a large extent they are. The government is now expanding cash aid to cover the entire country.

But there’s a catch. Nasilele’s family would not be eligible for the nationwide version of the program.

Instead, the government is reserving the money for people who really can’t work--the elderly, the sick, single moms with lots of kids. They’re not going to give it to the kinds of families that made up the vast majority of the 1,250 households in the pilot program: families where there’s both a mom and a dad, who are able-bodied.

That option was considered too controversial, explains Esther Ngambi, the official in charge of the new cash program.

“Everybody would be saying that you’re trying to give money to lazy people--that you’re encouraging laziness,” Ngambi says.

For years, evidence has been mounting about the effectiveness of cash aid over traditional aid to the poor such as food or seeds or job training. But Zambia’s experience suggests that when it comes to persuading governments to adopt the approach, evidence might not be enough. Zambia’s study--which spanned five years, analyzed data from 5,500 households and cost about $5 million--is one of the most significant to date. And the country’s commitment to pouring its own resources into cash aid has established it as a leader of one of the most intriguing trends in the fight to conquer poverty. Yet this is also a tale of how gut feelings about which poor people deserve our help, and which do not, can be so entrenched they led a government to ignore the most powerful lesson of its own experiment.

When the possibility of cash aid was first floated in Zambia, it seemed totally implausible. The year was 2009. Cash aid had already emerged as a hot idea among social scientists who research anti-poverty efforts. Nongovernmental groups had launched some small-scale efforts to do it in Zambia. And some of the donors involved, including UNICEF and the German and British governments, were pushing Zambia’s leaders to try cash aid in a bigger way.

But Zambian officials were wary of giving people money with no strings attached. “People would say, you’re just putting money into a bottomless pit,” recalls Ngambi. There was concern that people would squander the money on vices, she says. For instance, “that men will be using the money for beer.” And even if people used the money for legitimate needs like food, the assumption was that as soon as they spent it they’d be right back where they started and would need more help--making cash aid an unsustainable drain on Zambia’s budget.

Still, officials in Ngambi’s ministry, which administers social welfare programs, were intrigued enough to set up two pilot programs. The first gave the money to any mother of a young child. This was the program Likezo Nasilele signed up for. The second targeted people who were somehow incapacitated, meaning that working was more difficult for them, if not impossible--such as the disabled or elderly people caring for orphaned relatives.

Then officials commissioned a study of these pilots from one of the premier researchers on the subject, Ashu Handa, an economist and professor at the University of North Carolina.

Handa collected a wealth of data on recipients’ economic activities: How much more did they invest in their farms? Did they buy more livestock? Did they hire others to help with the farm work? How much did they produce? And did they open other businesses not related to farming?

A few years later, in 2014, those results started coming in. “Holy smoke!” says Handa. “They were incredible.” In both versions of the program, the recipients managed to boost their spending, which is effectively a measure of their income, by more than 50 percent over what the government had given them. In other words, if they got $100 over the course of a year in handouts, they spent an extra $200 above what they had been spending before--proof that they were using the free money to make more money.

And the benefits spilled over into the local economy. The beneficiaries spent their extra income at local shops. A related study by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization estimated that, as a result, shopkeepers and business owners saw their profits go up by 50 percent.

These kinds of returns are head and shoulders above what you generally get from traditional aid, says Handa. “I mean, I’ve never seen impacts so large in my life.”

There were two ways that the recipients used the cash to get ahead. In families led by people who were unable to work, they mainly used the money to hire others to help them farm their land more productively. But the young families--because they were able-bodied--did something that Handa argues is remarkable, and even more promising when it comes to growing Zambia’s economy long term: They became entrepreneurial.

Take Nasilele and her husband. They live in a tiny village called Yuka, in a round hut made of sticks and mud. Before the cash program, the couple mostly worked day jobs in construction, pulling in about $30 a month. Not even enough to cover basics like soap or shoes or food, says Nasilele.

“We would have one meal a day and maybe in between we would just have mangoes from our tree,” she recalls. “The thing that saved us were our mangoes.”

Lyoni, Nasilele’s husband, says he was all the more frustrated because he actually had an idea for how to make more money--”a business to sell reed mats.”

He pulls out a mat to show me. It’s about 6 feet by 10, woven from the reeds that grow in the marshes around their village. People sit on them or use them as fences and walls for their homes.

Making a mat takes hours. And in the village and its surroundings the mats sell for only 30 cents or so. But Lyoni thought if he could buy up a whole collection of mats from other people, rent a canoe and paddle across the marshes to a big town several hours away, he could probably sell the mats for 10 times as much.

To put together enough mats to make the trip worthwhile, “I figured we would need about $120,” says Lyoni. So when the couple found out Nasilele was going to get the government payments, they decided to save every penny for a mat business. They were so determined not to dip into their savings until they had reached the full amount that they gave the money to a local businessman to hold for them. It took more than a year.

Lyoni says he still remembers the afternoon his wife came home from getting the last payment. “I said to her, ‘Now everything’s going to be well with us.’ “

And he was right. Their first trip selling mats in the big town, they turned a profit of $340. Soon they were buying land on which to grow cassava and millet for food and even some luxuries--like cute outfits for their children. And they’re setting aside money to replace their thatch roof with a metal sheet.

Now, this isn’t easy money. Mats are actually a scarce commodity since they take so long to make. It takes weeks to purchase enough. On their last trip their canoe capsized in choppy waters and they lost every single one. Lyoni has also developed pain and stiffness in one of his hands that’s been making it ever more difficult to row.

But they’ve been able to ride out the bad breaks by pouring their earnings from the mats into even more businesses. They’re buying milk from local cow owners to resell in the market. They’re breeding chickens. And they’ve already started laying the plans for a new business that won’t require as much rowing: They want to buy nets to catch fish with, then travel inland to trade the fish for maize that they’ll bring back to their village to sell at a higher price.

And when I ask Lyoni, now that the cash program is being phased out for families like yours will you be OK? He shrugs it off.

“No,” he says. “We’re not worried that we’ll ever go back to the life we used to live. We’re on another level now.”

The researcher, Ashu Handa, says the implications of this dynamic--poor people using just a little bit of money to permanently lift themselves up--were huge.

Forty percent of Zambia’s population is extremely poor. The government had conceived of the cash aid as a safety net to keep them from starving. But here was a way to offer more than just a better safety net. Here was a way to help them graduate out of poverty--and simultaneously grow the whole economy--for pennies on the dollar.

“That seems to be in some sense the magic bullet,” says Handa. “Like, this is it.”

Best of all, Zambia can afford it. The country has vast reserves of resources like copper.

So why aren’t they going for it?

It turns out our preconceptions about the poor can trump the evidence.

Ngambi, the social welfare official, says there had been gripes from the public. To a lot of people the program meant young women were collecting a government check just for having a kid. People in the community and even in the media were accusing the women of having babies just to stay on the program. They were calling the women by the English word “divas”--in Zambia it connotes a woman who spends her time buying fancy clothes and fixing her hair. “Yeah,” says Ngambi, “we are turning them into these divas.”

As for the dads, she adds, “People would complain. The husband or the man in the house has the capacity to work so why should he be on the program?”

But most important, Ngambi says, Zambia’s top leaders shared that queasiness.

So Ngambi’s agency, which administers social welfare, has scaled back the pool of potential recipients. It’s giving cash aid only to people everyone in Zambia agrees is deserving--people who are “vulnerable” because they’re not able to work.

1 note

·

View note

Text

In the 1930s, the poet Langston Hughes published what remains one of the most honest descriptions of that dream:

"A dream so strong, so brave, so true

That even yet its mighty daring sings

In every brick and stone, in every furrow turned

That’s made America the land it has become"

The poem, though, is laced with a counterpoint of protest: “America was never America to me”—not to the “man who never got ahead”; “the poorest worker bartered through the years”; or “the Negro, servant to you all.” Still, for all its outrage, the poem ends with a paradoxical yearning: “O, let America be America again,” Hughes wrote. “The land that never has been yet.”

"Hearing stories of the American dream as a boy in New Delhi, Chetty adopted the faith. When he became a scientist, he discerned the truth. What remains is contradiction: We must believe in the dream and we must accept that it is false—then, perhaps, we will be capable of building a land where it will yet be true." PLEASE READ 📖 Or LISTEN 👂ON AUDUM AND SHARE TY🙏🙏🏽🙏🏾🙏🏿

The Economist Who Would Fix the American Dream.... No one has done more to dispel the myth of social mobility than Raj Chetty. But he has a plan to make equality of opportunity a reality.

GARETH COOK | AUGUST 2019 ISSUE, Updated at 3:47 p.m. ET on July 17, 2019. | The Atlantic Magazine | Posted July 21, 2019 |

RAJ CHETTY GOT his biggest break before his life began. His mother, Anbu, grew up in Tamil Nadu, a tropical state at the southern tip of the Indian subcontinent. Anbu showed the greatest academic potential of her five siblings, but her future was constrained by custom. Although Anbu’s father encouraged her scholarly inclinations, there were no colleges in the area, and sending his daughter away for an education would have been unseemly.

But as Anbu approached the end of high school, a minor miracle redirected her life. A local tycoon, himself the father of a bright daughter, decided to open a women’s college, housed in his elegant residence. Anbu was admitted to the inaugural class of 30 young women, learning English in the spacious courtyard under a thatched roof and traveling in the early mornings by bus to a nearby college to run chemistry experiments or dissect frogs’ hearts before the men arrived. Anbu excelled, and so began a rapid upward trajectory. She enrolled in medical school. “Why,” her father was asked, “do you send her there?” Among their Chettiar caste, husbands commonly worked abroad for years at a time, sending back money, while wives were left to raise the children. What use would a medical degree be to a stay-at-home mother?

In 1962, Anbu married Veerappa Chetty, a brilliant man from Tamil Nadu whose mother and grandmother had sometimes eaten less food so there would be more for him. Anbu became a doctor and supported her husband while he earned a doctorate in economics. By 1979, when Raj was born in New Delhi, his mother was a pediatrics professor and his father was an economics professor who had served as an adviser to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

When Chetty was 9, his family moved to the United States, and he began a climb nearly as dramatic as that of his parents. He was the valedictorian of his high-school class, then graduated in just three years from Harvard University, where he went on to earn a doctorate in economics and, at age 28, was among the youngest faculty members in the university’s history to be offered tenure. In 2012, he was awarded the MacArthur genius grant. The following year, he was given the John Bates Clark Medal, awarded to the most promising economist under 40. (He was 33 at the time.) In 2015, Stanford University hired him away. Last summer, Harvard lured him back to launch his own research and policy institute, with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

Chetty turns 40 this month, and is widely considered to be one of the most influential social scientists of his generation. “The question with Raj,” says Harvard’s Edward Glaeser, one of the country’s leading urban economists, “is not if he will win a Nobel Prize, but when.”