#Whitechapel Gallery

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Mark Rothko at Whitechapel Gallery, 1961; photo Sandra Lousada

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

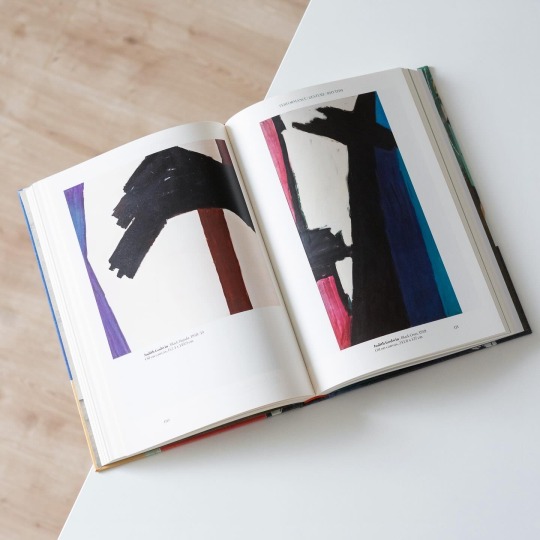

PLATES, Whitechapel Gallery, 2019-2020

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Teylers Wunderkammer

Top Je vous ai dit déjà tout le bien que je pensais du musée Teylers, le plus vieux des Pays-Bas (1784), plus vieux que le Louvre ! Il présente maintenant un cabinet de curiosités tout a fait particulier, plein de science surréaliste : il s’agit de la combinaison d’une collection d’objets scientifiques et de l’oeuvre d’un artiste contemporain. Le résultat est… oui, surréaliste. Et très fascinant…

View On WordPress

#19e siècle#19th century#art#cabinet de curiosités#exhibition#exposition#Haarlem#Joris Loudon#Pays-Bas#Salvatore Arancio#science#Sciences#Teylers#vaut la visite#Whitechapel Gallery#worth a visit#Wundeekammer#XIXe siècle

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

with lotta thießen & dom hale i'll be reading at the whitechapel gallery in london on 18/1/23 for lotte ls's excellent THIS ENERGY WASTED BY FLIGHT which has recently been published in the uk by pamenar press. come through, £5 https://shorturl.at/noLRS

#lotte ls#dom hale#lotta thießen#pamenar press#poetry#london#whitechapel gallery#this energy wasted by flight

0 notes

Text

Readings from whitechapel documents of contemporary art book on nature, edited by Jeffery Kastner. All the writings I have read involving animals.

#contemporary art#fine art#art and ecology#ecology#whitechapel gallery documents on contemporary art

0 notes

Text

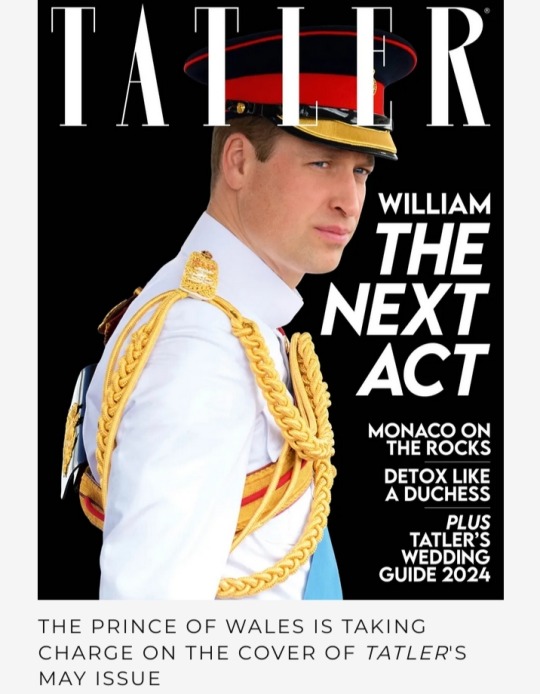

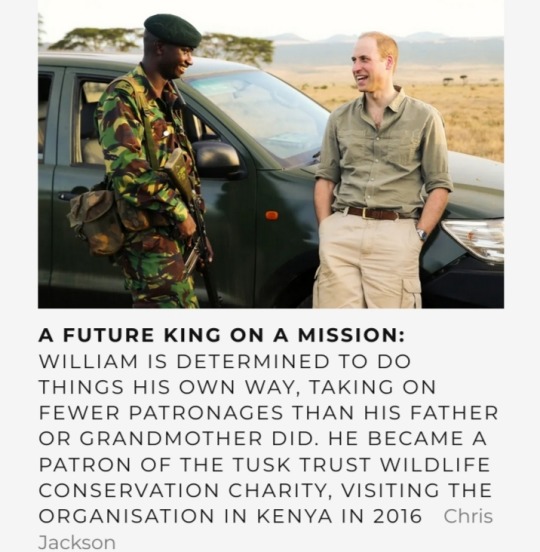

Inside William’s Next Act: Tatler’s May issue goes behind the scenes as the Prince of Wales is rising above the noise — and playing the long game

The burden of leadership is falling upon Prince William, but as former BBC Royal Correspondent, Wesley Kerr OBE, explains in Tatler’s May cover story, the future king is taking charge

By Wesley Kerr OBE

21 March 2024

When I first met Prince William in 2009, he asked me if I could tell him how he could win the National Lottery.

It was a jokey quip from someone who has since become the Prince of Wales, the holder of three dukedoms, three earldoms, two baronies and two knighthoods, and heir to the most prestigious throne on earth.

He was, of course, being relatable; I was representing the organisation that had allocated Lottery funding towards the Whitechapel Gallery and he wanted to put me at ease.

William is grand but different, royal but real.

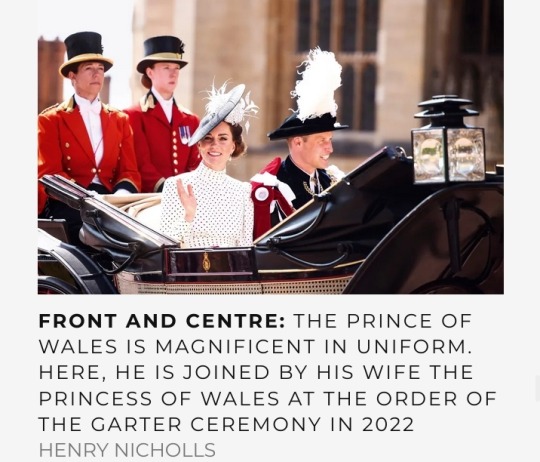

At 6ft 3in, he has the bearing and looks great in uniform after a distinguished, gallant military career.

He will be one of the tallest of Britain’s kings since Edward Longshanks in the 14th century and should one day be crowned sitting above the Stone of Scone that Edward ‘borrowed.’

William, by contrast, has a deep affinity with Scotland and Wales, having lived in both nations and gained solace from the Scottish landscape after his mother died.

He’s popular in America and understands that the Crown’s relationship to the Commonwealth must evolve.

The Prince of Wales has long believed that ‘the Royal Family has to modernise and develop as it goes along, and it has to stay relevant’, as he once said in an interview.

He seeks his own way of being relatable, of benefitting everybody, in the context of an ancient institution undergoing significant challenge and upheaval, as the head of a nation divided by hard times, conflicts abroad, and social and political uncertainty.

We might recognise Shakespeare’s powerful line spoken by Claudius in Hamlet: ‘When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions.’

With the triple announcement in January and February of the Princess of Wales’s abdominal surgery and long convalescence, of King Charles’s prostate procedure and then of his cancer diagnosis, the burden of leadership has fallen on 76-year-old Queen Camilla and, crucially, on William.

The Prince of Wales’s time has come to step up; and so he has deftly done.

In recent months, we have seen a fully-fledged deputy head of state putting into practice his long-held ideas, speaking out on the most contentious issue of the day and taking direct action on homelessness.

Last June, he unveiled the multi-agency Homewards initiative with the huge aspiration of ending homelessness, backed with £3 million from his Foundation to spearhead action across the UK.

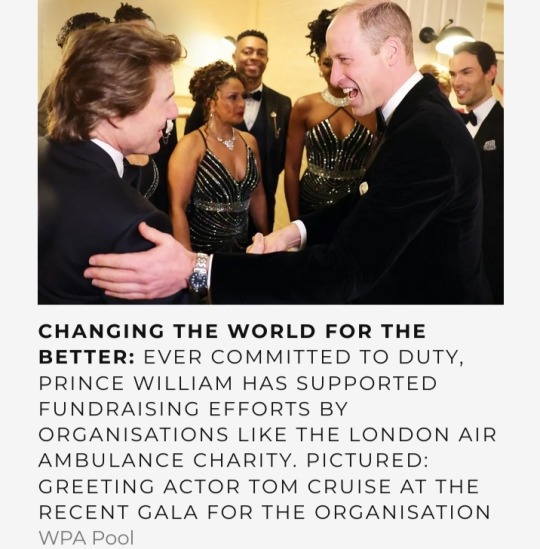

He is consolidating Heads Together, the long-standing campaign on mental health, and fundraises for charities like London’s Air Ambulance Charity.

He was, of course, once a pilot for the East Anglian Air Ambulance services – a profession that had its downside: seeing people in extremis or at death’s door, he found himself ‘taking home people’s trauma, people’s sadness.’

Tom Cruise was a guest at the recent London’s Air Ambulance Charity fundraiser, William’s first gala event after Kate’s operation.

And more stardust followed when William showed that, even without his wife by his side, he could outclass any movie star at the Baftas.

There’s also his immense aim of helping to ‘repair the planet’ itself with his Earthshot Prize: five annual awards of £1 million for transformative environmental projects with worldwide application.

This project has a laser focus on biodiversity, better air quality, cleaner seas, reducing waste and combating climate change. Similar aims to his father; different means to achieve the goal.

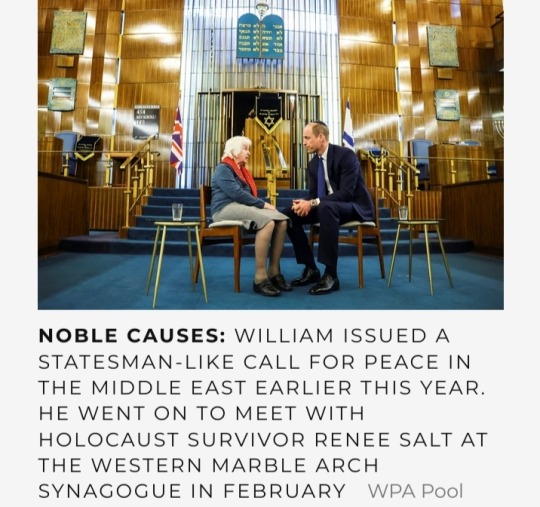

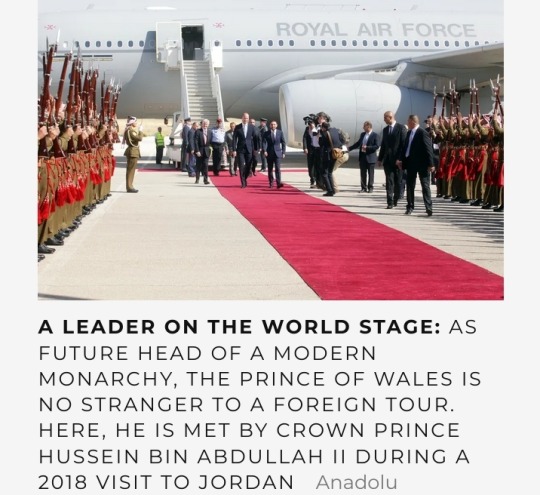

On the issue which has caused huge convulsions – the Middle East conflict – William’s 20 February statement from Kensington Palace grabbed attention.

He said he was ‘deeply concerned about the terrible human cost of the conflict since the Hamas terrorist attack on 7 October. Too many have been killed.’

There were criticisms – along the lines of ‘the late Queen would have never spoken out like this’ or ‘what right does he have to meddle in politics?’ – but it was hard to disagree with his carefully calibrated words.

His call for peace, the ‘desperate need’ for humanitarian aid, the return of the hostages.

The statement was approved by His Majesty’s Government, likely cleared with the King himself at Sandringham the previous weekend and also backed by the chief rabbi of Great Britain, Sir Ephraim Mirvis.

Indeed, William and Catherine had immediately spoken out on the horrors of 7 October.

William followed up the week after his Kensington Palace statement by visiting a synagogue and sending a ‘powerful message’, according to the chief rabbi, by meeting a Holocaust survivor and condemning anti-Semitism.

This is rooted in deep personal conviction following William’s 2018 visit to Israel and the West Bank, says Valentine Low, the distinguished author of Courtiers and The Times’s royal correspondent of 15 years, who was on that 2018 trip.

‘William was so moved by his visit to Israel and the West Bank, he found it very affecting, and he was not going to drop this issue – he was going to pay attention to it for the rest of his life,’ says Low.

‘He must feel that… not to say something on the most important issue in the world [at that moment] would be a bit odd if you feel so strongly about it.’

There was concern from some commentators about politicising the monarchy, but this rose above the particulars of party politics.

As Prince of Wales, like his father before him, there is perhaps space to speak out sparingly on carefully chosen issues.

On this occasion, his views were in line with majority public opinion.

On homelessness, news came that same week that William was planning to build 24 homes for the homeless on his Duchy of Cornwall estate.

‘William’s impact is very personal,’ says Mick Clarke, chief executive of The Passage, a charity providing emergency accommodation for London’s homeless.

‘Two weeks before Christmas, the prince came to our Resource Centre in Victoria for a Christmas lunch for 150 people.

He was scheduled to stay for an hour, to help serve, wash up, and talk to people.

He ended up staying for two and a quarter hours, during which time he went from table to table and spoke to every single person.’

Clarke continues:

‘William has an ability to listen, talk and to put people at ease. During the November 2020 lockdown, he came on three separate occasions to help.

It gave the team a boost that he took the time; it was his way of saying: “I support you; you’re doing a great job.”’

Seyi Obakin, chief executive of Centrepoint, one of the prince’s best-known causes, adds:

‘People associate his patronage with the big moments like the time he and I slept under Blackfriars Bridge.

The things that stick with me are smaller in scale and the more profound for it – in quieter moments, away from the cameras, where he has volunteered his time.’

It is a different approach from the King’s.

As Prince of Wales, he was involved in the minutiae of dozens of issues at any one time, working into the night to follow up on emails, crafting his speeches, writing or dictating notes.

Add to that much nationwide touring over 40 years (after he left active military service in 1976), fitting in multiple engagements, often being greeted formally by lord lieutenants.

This is not William’s style. He has commended his father’s model, but he does things his own way.

Although patronages are under review, William has up till now far fewer than either his father or his grandparents.

Charles is sympathetic to William’s approach and his desire to make time with his young family sacrosanct.

They are confidantes, attested by the night of Queen Elizabeth’s death.

They were both at Birkhall with Camilla, reviewing funeral arrangements while the rest of the grieving family were nearby at Balmoral, hosted by the Princess Royal.

Charles has had almost six decades in public life and is the senior statesman of our time, with even longer in the spotlight than Joe Biden.

After Eton and St Andrew’s University, where he met Catherine, William served in three branches of the military between 2006 and 2013, finishing as a seasoned and skilled helicopter rescue pilot.

His later employment as an air ambulance pilot stopped in 2017, when he became a full-time working royal.

At that time, not so long ago – with Harry unmarried, Andrew undisgraced, and Philip and Elizabeth still active – William shared the spotlight.

Now, after the King, he’s the key man.

He can look back on the success of his first big campaign initially launched with his wife and brother in 2016: Heads Together.

‘We are delighted that Prince William should have become such a positive and sympathetic advocate for mental health through his Heads Together initiative and now well-established text service, Shout, among other projects,’ says the longtime CEO and founder of Sane, the remarkable Marjorie Wallace CBE.

‘It is not always known that he follows in the footsteps of his father, the King, whose inspiration and vision were vital in the creation of our mental health charity Sane.

As founding patron, he was instrumental in establishing our 365-days-a-year helpline and was a remarkable and selfless support to me in setting up the Prince of Wales International Centre for Sane Research.’

'Indeed,' says Wallace, 'this is where Prince William echoes the work of his father, showing the same ‘understanding and compassion for people struggling through dark and difficult times of their lives and has done much to raise awareness and encourage those affected to speak out and seek help.

We owe a huge debt to His Majesty and the Prince of Wales for their involvement in this still-neglected area.’

Just as I saw all those years ago at that early solo engagement in Whitechapel, William still approaches his public duties with humour and fun.

‘He defuses the formality with jocularity,’ says Valentine Low, citing two public events in 2023 that he witnessed.

In April last year, while on a visit to Birmingham, William randomly answered the phone in an Indian restaurant he was being shown around and took a table booking from a customer – an endearing act of spontaneity.

On his arrival later that day, the unsuspecting diner was surprised to be told exactly whom he had been talking to.

In October, Low reported, William ‘unleashed his inner flirt as he hugged his way through a visit with Caribbean elders [in Cardiff] to mark Black History Month.

As he gave one woman a hug – for longer than she expected – he joked: “I draw the line at kissing.”

And while posing for a group photograph, he prompted gales of laughter when he quipped: “Who is pinching my bottom?”’

Low believes that when William eventually becomes king, he will be more ‘radical’ than his father but wonders if people will respond to ‘call me William’ when ‘the whole point of the Royal Family is mystique and being different.’

However, William has thought deeply about his current role and is prepared for whatever his future holds.

For now, there is a decision to be made on Prince George’s secondary schooling. It’s said that five public schools are being considered, all fee-paying.

Eton is single-sex and boarding but close to home. Marlborough (Catherine’s alma mater) is co-ed and full boarding. And Oundle, St Edward’s Oxford and Bradfield College (close to Kate’s parents) are co-ed with a mix of boarding and day.

As parents, William and Catherine aspire to raise their children ‘as good people with the idea of service and duty to others as very important’, William said in an interview with the BBC in 2016.

‘Within our family unit, we are a normal family.’ Which may be one reason why he is so resistant to their privacy being compromised either by the media or close family members.

The 19th-century author Walter Bagehot wrote:

‘A family on the throne is an interesting idea also. It brings down the pride of sovereignty to the level of petty life… a princely marriage is the brilliant edition of a universal fact, and, as such, it rivets mankind.’

If hereditary monarchy is to survive, it must beguile us but also demonstrate its utility, that it is a force for good.

William said in that 2016 interview, ‘I’m going to get plenty of criticism over my lifetime,’ echoing Queen Elizabeth II’s famous Guildhall speech in 1992 ‘that criticism is good for people and institutions that are part of public life. No institution – city, monarchy, whatever – should expect to be free from the scrutiny of those who give it their loyalty and support, not to mention those who don’t.’

William saw close up his mother’s ability to bring public focus and her own personal magnetism to any subject or cause she focused on.

He admires his father’s work ethic, the way he ‘really digs down,’ sometimes literally (I understand that gardening is giving the King solace during his cancer treatment).

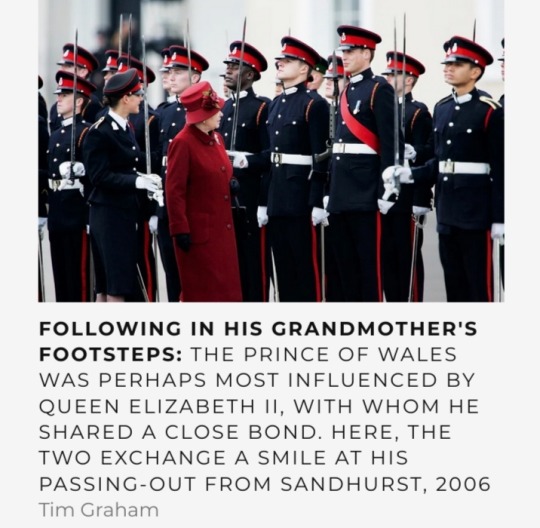

But the biggest influence for William was Her late Majesty, as he said on her 90th birthday.

As an Eton schoolboy, William made weekend visits to the big house on the hill, being mentored by Granny rather as she had been tutored in the Second World War by the then vice-provost of Eton, Sir Henry Marten.

William said in 2016:

‘In the Queen, I have an extraordinary example of somebody who’s done an enormous amount of good and she’s probably the best role model I could have.’

That said, his aim was ‘finding your own path but with very good examples and guidance around you to support you.'

Queen Elizabeth II had a brilliant way of rising above the fray and usually being either a step ahead of public opinion or in tune with it.

If you are at the helm of affairs in a privileged hereditary position, your duty is to serve and use your pulpit for the benefit of others.

In a democracy, monarchy is accountable.

The scrutiny is intense, with an army of commentators paid for wisdom and hot air about each no-show, parsing each announcement, interpreting each image.

William takes the long view. He has ‘wide horizons,’ says Mick Clarke.

‘There are so many causes that are more palatable and easier to achieve than ending homelessness, but his commitment and drive are 100 per cent.’

The prince seeks a different way of being royal in an ancient institution that must move with the times. His task? To develop something modern in an ever-changing world.

He faces all sorts of new issues – or old issues in new guises.

Noises off from within the family don’t help – Andrew’s difficulties, or the suggestions of prejudice from Montecito a couple of years ago (now seemingly withdrawn), which prompted William’s most vehement soundbite: ‘We’re very much not a racist family.’

William is maybe a new kind of leader who can keep the monarchy relevant and resonant in the coming decades.

Queen Elizabeth II is a powerful exemplar and memory, but she was of her time. William is his own man.

He must overcome and think beyond ‘the unforgiving minute.’

Indeed, he could seek inspiration in Rudyard Kipling’s poem, If.

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch[…]

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!

This article was first published in the May 2024 issue, on sale Thursday, 28 March.

#Prince William#Prince of Wales#British Royal Family#Wesley Kerr OBE#Edward Longshanks#Homewards#Heads Together#London’s Air Ambulance Charity#East Anglian Air Ambulance#Tom Cruise#BAFTAS#Earthshot Prize#Kensington Palace#King Charles III#Sir Ephraim Mirvis#Valentine Low#Duchy of Cornwall estate#The Passage#Centrepoint#Birkhall#Sane#Marjorie Wallace CBE#Shout#Balmoral#Prince George#Walter Bagehot#Sir Henry Marten#Rudyard Kipling#If

149 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rothko Exhibition, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 1961

by Sandra Lousada

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sound is invisible stuff. Those who have expertise in its properties and potentialities also have a tendency to lack a full understanding of the worlds of tactile matter, visible surfaces, the volume of sound. Sound is a thing and no-thing, like air, money, time or love, complex to infinitude as one of the ungraspable phantoms of life. All these metaphors we use to bring into being the property of sound and the sensation of its hearing: a honeyed voice, a rough voice, a piercing scream; the taste of viscosity, a hand passes over splintered wood, a needle punctures the skin. Think of sound – that high sound of hearing and air – pouring into the volume of a space, translucent block of air like colourless jelly flecked and warped with every passing noise event and its trail of decomposing matter, something like a stiff liquid or intangible runny paste through which the body passes without resistance yet it enfolds and penetrates the body with the insistence of abyssal pressure and the clotted emotions of memories as active entities, in flight like birds, insubstantial as papery moths.

David Toop, A Piercing Silence: James Richards, from Inflamed Invisible, originally published in James Richards: To Replace a Minute's Silence With a Minute's Applause, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2015

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Veryyy general look at the Story Chapters (Books? Wait genuine question are we calling the main story Books or Chapters?) and the Books / media they are based on (Global only)

(I think someone has done this already?)

Prologue: This is Tomorrow - quick search seems that the title is a reference to the 1956 London Art Exhibition that opened in the Whitechapel Art Gallery and considered a watershed in British post-art and kick starting the art movement of "Pop Art" (see the effects of the Storm having comic book like attributes)

(Richard Hamilton was a painter famous for Pop Art and had a work in that exhibition so it checks out)

Book One: In Our Time - based on a collection of short stories of the same name by Hemingway. these are stories about before, during and after WW1. The stories have a general theme of separation, loss, death, grief and alienation. (Potentially allusions to Druvis maybe?)

Book Two: Tender is the Night - this is the final completed book by Scot Fitzgerald (who wrote the Great Gatsby and referred in the beginning quote of the game) and is a tragedy that follows the deterioration of a married couple that reflects Fitzgerald's own troubled relationship with his wife who Schneider's design greatly references. (The couple in the Book either inspire Druvis and FMN's relationship or Vertin and Schneider's relationship)

Book Three: Nouvelles et Textes pour Rien. (Translation is 'Stories and Texts for Nothing') - Again a collection of stories by Samuel Beckett. Seems to be lesser known, heres from Wikipedia "All three stories deal with the deplacement or expulsion of three old men who are forced to leave their modest lives in search of a new niche they might fit" (the SPDM kids desire to learn more about themselves and the outside world)

Book Four: EL ORO DE LOS TIGRES (Translation "the Gold of Tigers") - this is even harder to find stuff on and in English,An allegoric analysis of the contemporary juvenile reality. A review of the movie based on the book- "Inspired by a J.L.Borges' collection of poems, the story recounts the survey of an individual conscience by three young men, surrounded by the nihilism of a society with a hopelessly urban future" ( the struggle between Madam Z and the suitcase fam against the oppressive Foundation maybe?)

Book Five: Prisoner in the Cave - Based on Plato's allegory of the cave

Book Six: E Lucevan le stelle (Translation "the stars are shining") based on the opera of Tosca by Giacomo Puccini in 1900, the title is a direct reference to an aria sung in the Third Act which Isolde also sings parts of.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lygia Clark: The I and the You Whitechapel Gallery, London October 2, 2024 – January 12, 2025

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Don Judd,’ the artist’s first major European retrospective opened at the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven in the Netherlands fifty-five years ago today on January 16, 1970. The exhibition included six floor works and six wall works, one of which was acquired by the museum for its collection. Curated by Jean Leering, then museum director, the exhibition then traveled to the Museum Folkwang in Essen; Kunstverein in Hannover; and Whitechapel Art Gallery in London.

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://www.tumblr.com/pynkhues/770330080935346176/httpswwwtumblrcomloustat-0770311728091299840?source=share

That is something I love about your fics, how viscerally you convey their need to touch each other, not just sexually, but all touch.

Anon, 😭😭 you're very lovely, thank you. This is still a little sexy, but have a domestic snippet from the Cruising fic:

-

Bzzt.

Bzzzzzzzzttttt.

Louis feels his face pinch as he’s roused from his slumber by the sound of the loud vibration, glass ricocheting off glazed wood, echoing through the quiet sanctuary of his bedroom. It’s enough to pull him into the moment, into this new night, to this bed, to this city, to this entanglement, for he feels the knobs of Lestat’s bony spine against his chest before he feels anything else. Before he feels the numbness of his left arm, caught between Lestat’s side and the mattress, before he feels the curve of his perfect ass, cradled between Louis’ hips, and he works his mouth. Tastes the stale remnants of last night – of sleep and blood and Lestat – and he pushes his nose into the valley Lestat’s neck makes with his shoulder, inhales deeply, lets Lestat, however briefly, fill his senses as the blood drips south, and he drops his free hand to Lestat’s hip. Tilts it ever so slightly back against him, the blissful pressure, weight, seam of him there in his lap and- -

Bzzzzzzzzzttttttt.

And - -

Right.

With a low groan, Louis leans back just enough to fumble a hand out behind him in the dark, reaching for where his cell phone sits on his bedside table, blinks bleary eyes up at it as he turns the screen on, but despite a flurry of messages from a flurry of people, his phone’s not the one that’s ringing. He glances across the bed at where Lestat’s phone is glowing bright on top of the other table, and rolls over again to pull his left arm out from beneath Lestat, draping himself over him as he starts to stir, pressing a quick kiss to his shoulder and giving his bare ass a quick, light good-evening slap.

“Phone, baby.”

And Lestat practically growls at that, yanking himself out of sleep only to flop pathetically over in the sheets, grabbing his cell off the bedside table and letting loose a string of cusses in French when he recognises the contact. Still, he promptly answers, even if he does hook it between his head and shoulder so that he can reach a hand back behind him to fondle Louis’ cock briefly as he does it.

Despite himself, Louis can’t quite bite back the grin, half-hard but also awake enough now to know that this ain’t gonna happen on what seems like a work call, so he detaches Lestat’s hand from his (hot, already pulsing - - fuck, no one gets him going like Lestat) member, entwines their fingers briefly with an affectionate squeeze that has Lestat staring back at him unblinking over his shoulder, and sits up in bed, giving them a little distance. He rolls his shoulders back, wills his arousal away, shakes out his left arm to try and get some circulation back into it from where it was pinned beneath Lestat’s body for likely the entire day, before grabbing his phone again to actually read through his messages. There are a few from his assistant, passed on follow-up from the Whitechapel Gallery and meeting requests from property developers back in Dubai, a few from Margot, and one from Rashid about a potential buyer for another Klimt coming through a contact at Sotheby’s.

Enough to get to work, he thinks, slipping out of bed, feeling Lestat’s too hot gaze on the line of his nude body as he tosses on a slate grey cotton t-shirt and a pair of deep, autumnal red silk lounge pants, grabs his laptop from atop the dresser and pads downstairs towards the kitchen.

#i worked way more domesticity into this than i was expecting and i shan't apologise for it!!#haha#it's been fun to think of what they might be like in an environment that let them be stupidly in love#even if louis' still in relative denial that they're obviously back together haha#but seriously thank you#this was a really nice ask to log back into#like a dog-less bone#fic asks#iwtv fic

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Landslide, 2020

detail view in PLATES, Whitechapel Gallery

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

For decades the women of abstract art were pushed aside: critics and propagandists like Clement Greenberg focused on the male “geniuses”, e.g. Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning, and ignored the women artists contributing to abstraction. This marginalization continued in the historicization of abstract art and abstract expressionism in particular: in important exhibitions, e.g. at the MoMA’s 1970 show „New York Painting and Sculpture 1940-1970“, few or no women were included and also art history treated them stepmotherly. The latter actually went well beyond the American and European realms and concerned Asia or Latin America as well.

But thanks to feminist art historians women artists of abstraction have been wrested from oblivion and, although often after their passing, finally their due attention and praise. This concern also drove the Whitechapel Gallery, the Fondation Vincent Van Gogh and the Kunsthalle Bielefeld to collaborate on the survey exhibition „Action, Gesture, Paint - Women artists and abstraction worldwide 1940-70“: besides well-known artists like Helen Frankenthaler or Lee Krasner the exhibition also features lesser-known protagonists like Aiko Miyawaki, Tomie Ohtake or Franciszka Themerson. The final stage of the traveling exhibition at Kunsthalle Bielefeld until March 3 again demonstrates the general diversity of abstraction as an artistic idiom but also the quality of the gathered artists which in no way correlates to their relative obscurity. Instead, the exhibition leaves the impression that the male-dominated art world deliberately excluded the contribution of women to abstract art.

In order to enter deeper into the history of women and abstraction the present catalogue accompanying the exhibition is highly recommended: it collects 7 essays shedding light on a variety of topics, e.g. the rise of gestural abstraction as a global development with men and women acting as innovators side by side, as Laura Smith concludes, or the particular situation women artists faced in postwar Germany as elaborated by Laura Rehme. Thus, both catalogue and exhibition are an inspiring point of departure for exploring the female side of postwar abstract art.

#women artists#abstract art#exhibition catalogue#art book#art history#abstract expressionism#modern art

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rothko, Whitechapel Gallery 1961

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robert Rauschenberg

a cura di Dominique Stella

Catalogo a cura di Carlo Cambi

Galleria Agnellini Arte Moderna, Brescia 2015, 120 pagine, 28,5x25cm

euro 50,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

Mostra Galleria Agnellini Brescia 16 maggio - 31 ottobre 2015, in esposizione circa 20 opere polimateriche create dall’artista tra il 1973 e il 1988.

Il pensiero e l’opera di Robert Rauschenberg, nato a Port Arthur in Texas nel 1925, per la complessità dei temi affrontati e per l’originalità delle soluzioni prospettate, rivestono un ruolo primario nell’ambito della riflessione estetica della seconda metà del ‘900. L’artista salì alla ribalta nel periodo di transizione fra l’Espressionismo Astratto e la Pop Art degli anni '50. Allora Rauschenberg è conosciuto per i suoi Combines, nei quali utilizzava materiali non convenzionali e oggetti vari disposti in combinazioni innovative.

Rauschenberg ha lavorato anche con la fotografia, la stampa, la fabbricazione della carta e la performance. Nel 1962 utilizzò, per la prima volta, la tecnica della serigrafia su tela mescolata con pittura, collage e oggetti. Usata in precedenza solo in applicazioni commerciali, la serigrafia ha permesso a Rauschenberg di affrontare la riproducibilità delle immagini multiple e il conseguente appiattimento di esperienza che ciò comporta. Le immagini raccolte qua e là occupano un posto preminente nel suo linguaggio visivo, nel quale aggiunge le riproduzioni di giornali e riviste ai suoi disegni, alle sue opere grafiche e ai suoi dipinti, perfezionando la sua padronanza di varie tecniche come il trasferimento con il solvente, la litografia e la serigrafia. Egli concepì i suoi disegni basati sulla tecnica di trasferimento con il solvente nello stesso periodo dei suoi ultimi "Combine", e vi integrò il collage in uno spazio bidimensionale, con le immagini che seguono la superficie del lavoro e si mescolano ad aree disegnate o dipinte. La miscela di figurazione e astrazione rimarrà una caratteristica costante dello stile di Rauschenberg. Nel 1963 si tenne la sua prima retrospettiva europea alla Galerie Sonnabend di Parigi, portata anche al Jewish Museum di New York. Nel 1964 ebbe una retrospettiva alla Whitechapel Gallery, Londra, e vinse il Gran Premio alla Biennale di Venezia. Nel 1970 Rauschenberg lascia New York per stabilirsi a Captiva, un'isola nel Golfo della Florida, dove vive e lavora fino alla morte nel 2008, perfezionando la sua tavolozza di colori.

Lontano dall'immaginario urbano egli privilegia un linguaggio astratto e l'uso di fibre naturali, come tessuti e carta. Nella serie Hoarfrost, alla quale appartengono alcune delle opere del 1974 in mostra, Rauschenberg utilizza una varietà di tessuti trasparenti, traslucidi e opachi, che vanno dalla garza di cotone ad esotici raso e seta, su cui stampa testi e immagini ripresi da giornali e riviste. Altre opere della serie Airport, sempre del 1974, e della serie 7 characters, del 1982, hanno le stesse caratteristiche di assemblaggi di tessuti e oggetti vissuti incollati o serigrafati che riacquistano vita in montaggi e collages tipici della produzione dell’artista.

04/01/25

#Robert Rauschenberg#art exhibition catalogue#Galleria Agnellini Brescia 2015#opere polimateriche#art books#fashionbooksmilano

5 notes

·

View notes