#What is Agriculture Insurance Market

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#Agriculture Insurance Market#Agriculture Insurance Market Size#Agriculture Insurance Market Share#What is Agriculture Insurance Market

0 notes

Note

Opinion on the US's Cogs damn obsession with corn?

don't know what you're talking about specifically but my understanding of US agricultural policy in general is that being a farmer in capitalism sucks and has since colonization and for a long time the US government tried to make it suck less with subsidies which sometimes work (because people get paid predictably regardless of demand and its less like gambling with crops) but sometimes go over really badly (because then too many people grow it and the price per bushel goes down and then government has too much corn) and then a couple times they got rid of all the subsides and related regulations and that REALLY didnt work (because then the price just crashed hard and with nothing to compensate them a bunch of farmers, many of whom were in debt for other farming-related reasons, couldnt get paid and actually had to foreclose their farms, which accelerated the long-standing trend of farms getting foreclosed on and then being bought out by bigger farms that then ended up running INSANE multi million dollar operations, sometimes even on farms in other states where the owners do not live, in communities they do not contribute to) and they had to backpedal on it and then eventually they just started on the current system where you simply pass a farm bill every 10-12 years instead of yearly or biyearly and that way you simply dont have to think about it, and then when it is election time you go stand by a cornfield for a while for tv. it does not fix the huge enormous farms buying out smaller farms problem or any of the complicated related problems but it DOES put it off for longer which is more important.

sometimes also you (USAID for instance) can give the too-much-corn you have from farm subsidies to a foreign country as a 'gift' and say youre just being a helpful little guy, but in the process of doing so undercut the local farmers in that country because they cant compete with free stuff but that's cool because then the foreign country can't really survive as well without US agricultural aid and you can manipulate them to do imperialism better AND you have more demand for the corn which might raise the price per bushel in the US. also sometimes the corn is fed to livestock en masse because the meat is worth more and sometimes its made into gas or high fructose corn syrup, and sometimes the price is so low per bushel that the insurance on the field is worth more than the actual corn.

but. i CANNOT stress enough that the most important thing about corn is that you can stand next to it on tv and if you cant do that, maybe you can stand next to a guy who is around it a lot and say you are helping him.

in my relatively uneducated opinion the most epic way to solve this complex multi-century interdisciplinary push and pull of supply and demand would be to just pay farmers a salary through the state since youre already paying out massive state subsidies for crops you dont need anyway and the farmers are performing a vital service and that way you can guarantee people a consistent salary AND control how much of each thing gets planted so you dont have a massive stockpile at all times AND you reward individual people instead of paying out large amounts of money to whatever massive operation sells the most corn by virtue of being big, but if you dont want to do that then the second best thing is to just pass another mediocre farm bill whos inflexible 10-ish year lifespan makes it impossible for it to respond well to changes in market demand and that way you can just put off making tough decisions and instead stand next to a guy and a cornfield on tv again. which as we have covered is the most important part of american agriculture

#you know?#(i took an agricultural history class in college. dont remember everything but i remember my overall impression was this)#asks#plont asks

725 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction To Supporting Sustainable Agriculture For Witches and Pagans

[ID: An image of yellow grain stocks, soon to be harvested. The several stocks reach towards a blurred open sky, focusing the camera on he grains themselves. The leaves of the grains are green and the cereals are exposed].

PAGANISM AND WITCHCRAFT ARE MOVEMENTS WITHIN A SELF-DESTRUCTIVE CAPITALIST SOCIETY. As the world becomes more aware of the importance of sustainability, so does the duty of humanity to uphold the idea of the steward, stemming from various indigenous worldviews, in the modern era. I make this small introduction as a viticulturist working towards organic and environmentally friendly grape production. I also do work on a food farm, as a second job—a regenerative farm, so I suppose that is my qualifications. Sustainable—or rather regenerative agriculture—grows in recognition. And as paganism and witchcraft continue to blossom, learning and supporting sustainability is naturally a path for us to take. I will say that this is influenced by I living in the USA, however, there are thousands of groups across the world for sustainable agriculture, of which tend to be easy to research.

So let us unite in caring for the world together, and here is an introduction to supporting sustainable/regenerative agriculture.

A QUICK BRIEF ON SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE

Sustainable agriculture, in truth, is a movement to practise agriculture as it has been done for thousands of years—this time, with more innovation from science and microbiology especially. The legal definition in the USA of sustainable agriculture is:

The term ”sustainable agriculture” (U.S. Code Title 7, Section 3103) means an integrated system of plant and animal production practices having a site-specific application that will over the long-term:

A more common man’s definition would be farming in a way that provides society’s food and textile needs without overuse of natural resources, artificial supplements and pest controls, without compromising the future generation’s needs and ability to produce resources. The agriculture industry has one of the largest and most detrimental impacts on the environment, and sustainable agriculture is the alternative movement to it.

Sustainable agriculture also has the perk of being physically better for you—the nutrient quality of crops in the USA has dropped by 47%, and the majority of our food goes to waste. Imagine if it was composted and reused? Or even better—we buy only what we need. We as pagans and witches can help change this.

BUYING ORGANIC (IT REALLY WORKS)

The first step is buying organic. While cliche, it does work: organic operations have certain rules to abide by, which excludes environmentally dangerous chemicals—many of which, such as DDT, which causes ecological genocide and death to people. Organic operations have to use natural ways of fertilising, such as compost, which to many of us—such as myself—revere the cycle of life, rot, and death. Organic standards do vary depending on the country, but the key idea is farming without artificial fertilisers, using organic seeds, supplementing with animal manure, fertility managed through management practices, etc.

However, organic does have its flaws. Certified organic costs many, of which many small farmers cannot afford. The nutrient quality of organic food, while tending to be better, is still poor compared to regeneratively grown crops. Furthermore, the process to become certified organic is often gruelling—you can practise completely organically, but if you are not certified, it is not organic. Which, while a quality control insurance, is both a bonus and a hurdle.

JOINING A CSA

Moving from organic is joining a CSA (“Community supported agriculture”). The USDA defines far better than I could:

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), one type of direct marketing, consists of a community of individuals who pledge support to a farm operation so that the farmland becomes, either legally or spiritually, the community’s farm, with the growers and consumers providing mutual support and sharing the risks and benefits of food production.

By purchasing a farm share, you receive food from the farm for the agreed upon production year. I personally enjoy CSAs for the relational aspect—choosing a CSA is about having a relationship, not only with the farmer(s), but also the land you receive food from. I volunteer for my CSA and sometimes I get extra cash from it—partaking in the act of caring for the land. Joining a CSA also means taking your precious capital away from the larger food industry and directly supporting growers—and CSAs typically practise sustainable and/or regenerative agriculture.

CSAs are also found all over the world and many can deliver their products to food deserts and other areas with limited agricultural access. I volunteer from time to time for a food bank that does exactly that with the produce I helped grow on the vegetable farm I work for.

FARM MARKETS AND STALLS

Another way of personally connecting to sustainable agriculture is entering the realm of the farm stall. The farmer’s market is one of my personal favourite experiences—people buzzing about searching for ingredients, smiles as farmers sell crops and products such as honey or baked goods, etc. The personal connection stretches into the earth, and into the past it buries—as I purchase my apples from the stall, I cannot help but see a thousand lives unfold. People have been doing this for thousands of years and here I stand, doing it all over again.

Advertisement

Farmers’ markets are dependent on your local area, yet in most you can still develop personal community connections. Paganism often stresses community as an ideal and a state of life. And witchcraft often stresses a connection to the soil. What better place, then, is purchasing the products from the locals who commune with the land?

VOLUNTEERING

If you are able to, I absolutely recommend volunteering. I have worked with aquaponic systems, food banks, farms, cider-making companies, soil conservation groups, etc. There is so much opportunity—and perhaps employment—in these fields. The knowledge I have gained has been wonderful. As one example, I learned that fertilisers reduce carbon sequestration as plants absorb carbon to help with nutrient intake. If they have all their nutrients ready, they do not need to work to obtain carbon to help absorb it. This does not even get into the symbiotic relationship fungi have with roots, or the world of hyphae. Volunteering provides community and connection. Actions and words change the world, and the world grows ever better with help—including how much or how little you may provide. It also makes a wonderful devotional activity.

RESOURCING FOOD AND COOKING

Buying from farmers is not always easy, however. Produce often has to be processed, requiring labour and work with some crops such as carrots. Other times, it is a hard effort to cook and many of us—such as myself—often have very limited energy. There are solutions to this, thankfully:

Many farmers can and will process foods. Some even do canning, which can be good to stock up on food and lessen the energy inputs.

Value-added products: farms also try to avoid waste, and these products often become dried snacks if fruit, frozen, etc.

Asking farmers if they would be open to accommodating this. Chances are, they would! The farmer I purchase my CSA share from certainly does.

Going to farmers markets instead of buying a CSA, aligning with your energy levels.

And if any of your purchased goods are going unused, you can always freeze them.

DEMETER, CERES, VEIA, ETC: THE FORGOTTEN AGRICULTURE GODS

Agricultural gods are often neglected. Even gods presiding over agriculture often do not have those aspects venerated—Dionysos is a god of viticulture and Apollon a god of cattle. While I myself love Dionysos as a party and wine god, the core of him remains firmly in the vineyards and fields, branching into the expanses of the wild. I find him far more in the curling vines as I prune them than in the simple delights of the wine I ferment. Even more obscure gods, such as Veia, the Etruscan goddess of agriculture, are seldom known.

Persephone receives the worst of this: I enjoy her too as a dread queen, and people do acknowledge her as Kore, but she is far more popular as the queen of the underworld instead of the dear daughter of Demeter. I do understand this, though—I did not feel the might of Demeter and Persephone until I began to move soil with my own hands. A complete difference to the ancient world, where the Eleusinian mysteries appealed to thousands. Times change, and while some things should be left to the past, our link to these gods have been severed. After all, how many of us reading know where our food comes from? I did not until I began to purchase from the land I grew to know personally. The grocery store has become a land of tearing us from the land, instead of the food hub it should be.

Yet, while paganism forgets agriculture gods, they have not forgotten us. The new world of farming is more conductive and welcoming than ever. I find that while older, bigoted people exist, the majority of new farmers tend to be LGBT+. My own boss is trans and aro, and I myself am transgender and gay. The other young farmers I know are some flavour of LGBT+, or mixed/poc. There’s a growing movement for Black farmers, elaborated in a lovely text called We Are Each Other’s Harvest.

Indigenous farming is also growing and I absolutely recommend buying from indigenous farmers. At this point, I consider Demeter to be a patron of LGBT+ people in this regard—she gives an escape to farmers such as myself. Bigotry is far from my mind under her tender care, as divine Helios shines above and Okeanos’ daughters bring fresh water to the crops. Paganism is also more commonly accepted—I find that farmers find out that I am pagan and tell me to do rituals for their crops instead of reacting poorly. Or they’re pagan themselves; a farmer I know turned out to be Wiccan and uses the wheel of the year to keep track of production.

Incorporating these divinities—or concepts surrounding them—into our crafts and altars is the spiritual step towards better agriculture. Holy Demeter continues to guide me, even before I knew it.

WANT CHANGE? DO IT YOURSELF!

If you want change in the world, you have to act. And if you wish for better agriculture, there is always the chance to do it yourself. Sustainable agriculture is often far more accessible than people think: like witchcraft and divination, it is a practice. Homesteading is often appealing to many of us, including myself, and there are plenty of resources to begin. There are even grants to help one improve their home to be more sustainable, i.e. solar panels. Gardening is another, smaller option. Many of us find that plants we grow and nourish are far more potentant in craft, and more receptive to magical workings.

Caring for plants is fundamental to our natures and there are a thousand ways to delve into it. I personally have joined conservation groups, my local soil conservation group, work with the NRCs in the USA, and more. The path to fully reconnecting to nature and agriculture is personal—united in a common cause to fight for this beautiful world. To immerse yourself in sustainable agriculture, I honestly recommend researching and finding your own path. Mine lies in soil and rot, grapevines and fruit trees. Others do vegetables and cereal grains, or perhaps join unions and legislators. Everyone has a share in the beauty of life, our lives stemming from the land’s gentle sprouts.

Questions and or help may be given through my ask box on tumblr—if there is a way I can help, let me know. My knowledge is invaluable I believe, as I continue to learn and grow in the grey-clothed arms of Demeter, Dionysos, and Kore.

FURTHER READING:

Baszile, N. (2021). We are each other’s harvest. HarperCollins.

Hatley, J. (2016). Robin Wall Kimmerer. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Environmental Philosophy, 13(1), 143–145. https://doi.org/10.5840/envirophil201613137

Regenerative Agriculture 101. (2021, November 29). https://www.nrdc.org/stories/regenerative-agriculture-101#what-is

And in truth, far more than I could count.

References

Community Supported Agriculture | National Agricultural Library. (n.d.). https://www.nal.usda.gov/farms-and-agricultural-production-systems/community-supported-agriculture

Navazio, J. (2012). The Organic seed Grower: A Farmer’s Guide to Vegetable Seed Production. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Plaster, E. (2008). Soil Science and Management. Cengage Learning.

Sheaffer, C. C., & Moncada, K. M. (2012). Introduction to agronomy: food, crops, and environment. Cengage Learning.

Sheldrake, M. (2020). Entangled life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures. Random House.

Sustainable Agriculture | National Agricultural Library. (n.d.). https://www.nal.usda.gov/farms-and-agricultural-production-systems/sustainable-agriculture

#dragonis.txt#witchcraft#paganism#hellenic polytheism#witchblr#pagan#helpol#hellenic pagan#hellenic worship#hellenic paganism#hellenic polytheist#demeter deity#demeter worship#persephone deity#kore deity#raspol#etrupol#etruscan polytheist#etruscan polytheism#rasenna polytheism#rasenna polytheist#rasenna paganism

343 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gonna make this a quick one since I just don’t have the spoons for a really big effort post: Pre-CCP 20th Century China Did Not Have Feudal or Slave-like Land Tenancy Systems

Obviously what counts as “slave-like” is going to be subjective, but I think it's common, for *ahem* reasons, for people to believe that in the 1930’s Chinese agriculture was dominated by massive-scale, absentee landlords who held the large majority of peasant workers in a virtual chokehold and dictated all terms of labor.

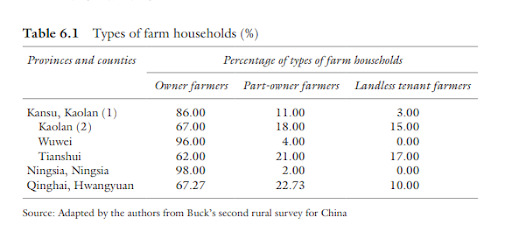

That is not how Chinese land ownership & agricultural systems worked. I am going to pull from Chinese Agriculture in the 1930s: Investigations into John Lossing Buck’s Rediscovered ‘Land Utilization in China’ Microdata, which is some of the best ground-level data you can get on how land use functioned, in practice, in China during the "Nanjing Decade" before WW2 ruins all data collection. It looks at a series of north-central provinces, which gives you the money table of this:

On average, 4/5ths of Chinese peasants owned land, and primarily farmed land that they owned. Tenancy was, by huge margins, the minority practice. I really don’t need to say more than this, but I'm going to because there is a deeper point I want to make. And it's fair to say that while this is representative of Northern China, Southern China did have higher tenancy rates - not crazy higher, but higher.

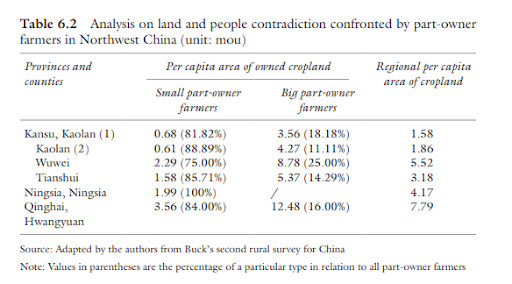

So let's look at those part-owner farmers; sounds bad right? Like they own part of their land, but it's not enough? Well, sometimes, but sometimes not:

A huge class (about ~1/3rd) of those part-owners were farming too much land, not too little; they were enterprising households renting land to expand their businesses. They would often engage in diversified production, like cash crops on the rented land and staple crops on their owned land. Many of them would actually leave some of their owned land fallow, because it wasn’t worth the time to farm!

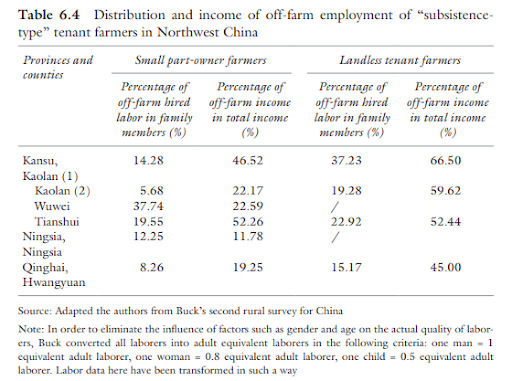

Meanwhile the small part-owners and the landless tenant farmers would rent out land to earn a living…sometimes. Because that wasn’t the only way to make a living - trades existed. From our data, if you are a small part-owner, you got a substantial chunk of your income from non-farm labor; if you owned no land you got the majority of your income from non-farm labor:

(Notice how that includes child labor by default, welcome to pre-modernism!)

So the amount of people actually doing full-tenancy agriculture for a living is…pretty small, less than 10% for sure. But what did it look like for those who do? The tenancy rates can be pretty steep - 50/50 splits were very common. But that is deceiving actually; this would be called “share rent”, but other systems, such as cash rents, bulk crop rents, long-term leases with combined payment structures, etc, also existed and were plentiful - and most of those had lower rent rates. However, share rent did two things; one, it hedged against risk; in the case of a crop failure you weren't out anything as the tenant, a form of insurance. And two, it implied reciprocal obligations - the land owner was providing the seed, normally the tools as well, and other inputs like fertilizer.

Whether someone chose one type of tenancy agreement or the other was based on balancing their own labor availability, other wage opportunities, the type of crop being grown, and so on. From the data we have, negotiations were common around these types of agreements; a lot of land that was share rent one year would be cash rent another, because the tenants and market conditions shifted to encourage one or the other form.

I’m doing a little trick here, by throwing all these things at you. Remember the point at the top? “Was this system like slavery?” What defines slavery? To me, its a lack of options - that is the bedrock of a slave system. Labor that you are compelled by law to do, with no claim on the output of that work. And as I hit you with eight tiers of land ownership and tenancy agreements and multi-source household incomes, as you see that the median person renting out land to a tenant farmer was himself a farmer as a profession and by no means some noble in the city, what I hope becomes apparent is that the Chinese agricultural system was a fully liquid market based on choice and expected returns. By no means am I saying that it was a nice way to live; it was an awful way to live. But nowhere in this system was state coercion the bedrock of the labor system. China’s agricultural system was in fact one of the most free, commercial, and contract-based systems on the planet in the pre-modern era, that was a big source of why China as a society was so wealthy. It was a massive, moving market of opportunities for wages, loans, land ownership, tenancy agreements, haggled contracts, everyone trying in their own way to make the living that they could.

It's a system that left many poor, and to be clear injustices, robberies, corruption, oh for sure were legion. Particularly during the Warlord Era mass armies might just sweep in and confiscate all your hard currency and fresh crops. But, even ignoring that the whole ‘poverty’ thing is 90% tech level and there was no amount of redistribution that was going to improve that very much, what is more important is that the pre-modern world was *not* equally bad in all places. The American South was also pretty poor, but richer than China in the 19th century. And being a slave in the American South was WAY worse than being a peasant in China during times of peace - because Confederate society built systems to remove choice, to short-circuit the ebb and flow of the open system to enshrine their elite ‘permanently’ at the top. If you lived in feudal Russia it was a good deal worse, with huge amounts of your yearly labor compelled by the state onto estates held by those who owned them unimpeachably by virtue of their birthright (though you were a good deal richer just due to basic agriculture productivity & population density, bit of a tradeoff there).

If you simply throw around the word “slavery” to describe every pre-modern agricultural system because it was poor and shitty, that back-doors a massive amount of apologia for past social systems that were actively worse than the benchmarks of the time. Which is something the CCP did; their diagnosis of China’s problem for the rural poor of needing massive land redistribution was wrong! It was just wrong, it was not the issue they were having. It was not why rural China was often poor and miserable. It could help, sure, I myself would support some compensated land redistribution in the post-war era as a welfare idea for a fiscally-strapped state. But that was gonna do 1% of the heavy lifting here in making the rural poor's lives better. And I don’t think we should continue to the job of spreading the CCP's propaganda for them.

There ya go @chiefaccelerator, who alas I was not permitted to compel via state force into writing this for me, you Qing Dynasty lazy peasant.

290 notes

·

View notes

Text

Electronic Maintenance of Commercial Books Starts in Turkey

Electronic maintenance of commercial books unrelated to accounting of the business starts in Turkey. That is a sign of a new era in the field of Corporate Governance and Commercial in Turkey.

Table of Contents

Introduction

What is Corporate Governance?

Which Companies are Obligatory for Electronic Keeping of Books in Question?

What is meant by System User?

Conclusion

Introduction

The electronic maintenance of commercial books unrelated to accounting of the business has been officially introduced in Turkey. That is declared by the Communiqué in the Official Gazette dated 14 February 2025 and numbered 32813. The present article will analyze long term implications of the regulatory change upon Turkish markets. Turkish business lawyers should update their corporate governance consulting process because of new developments.

What is Corporate Governance?

Corporate governance encompasses rules, practices, and processes guiding proper management and oversight of a company. Corporate governance encompasses the rules, practices, and processes that guide a company’s management and oversight. Typically, a company’s board of directors holds the responsibility for these activities, which include organizing senior management, overseeing audits, and managing board and general assembly meetings according to both national and international standards.

Regarding more information about how the system operates for corporate governance consulting take a look at our practice area: Corporate Governance

Scope of Electronic Keeping of Commercial Books Companies are now permitted to maintain certain commercial books electronically, provided these books are unrelated to accounting records. Article 2 of the Communiqué designates the following books as eligible for electronic storage:

share ledger [pay defter in Turkish],

board of directors’ resolution book [yönetim kurulu karar defteri in Turkish],

board of managers’ resolution book [müdürler kurulu karar defteri in Turkish],

general assembly meeting book [genel kurul toplantı defteri in Turkish],

negotiation book [müzakere defteri in Turkish].

It means that the aforementioned books will be kept electronically under the new Communiqué by companies for and beyond 2025.

Which Companies are Obligatory for Electronic Keeping of Books in Question?

Those companies are obligated to electronic keeping of commercial books:

Companies whose incorporation is registered with the Trade Registry as of 1 January 2026

Bankings, financial leasing companies, factoring companies, consumer finance and card services companies, asset management companies, insurance companies, holding companies established as joint stock companies, companies operating foreign exchange kiosks, companies engaged in general retailing, agricultural products licensed warehousing companies, commodity specialization exchange companies, independent auditing companies, surveillance companies, technology development zone management companies, companies subject to the Capital Markets Law numbered 2499 and free zone founder and operator companies.

Companies not included in this mandatory list may voluntarily opt for electronic bookkeeping. However, those choosing to transition to electronic records must obtain a closing certification for their physical books from a local notary. In this case, all books shall be kept in an electronic environment. Companies wishing to voluntarily maintain their commercial books electronically should obtain a closing certification for their physical books before local notaries.

What is meant by System User?

System users play a critical role upon electronic keeping of commercial books. System users are defined by the company management or managing partner managing partners. Therefore a system user can be a member of the management body, one of managing partners or a third party.

Companies are obligated to scrutinize closely and regularly the System user’s transactions and take appropriate steps if necessary for any unintended consequences.

Conclusion

Having regard to the aforementioned considerations, keeping commercial books not related to the accounting of the business electronically is made obligatory for the companies listed above. In summary, the mandatory electronic keeping of specified commercial books marks a significant transformation in corporate governance and regulatory compliance in Turkey. This requirement applies to companies listed in the Communiqué, while others may voluntarily adopt electronic bookkeeping starting July 2, 2025. This regulatory shift is expected to enhance transparency, efficiency, and regulatory oversight, ultimately strengthening corporate governance frameworks in Turkey.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

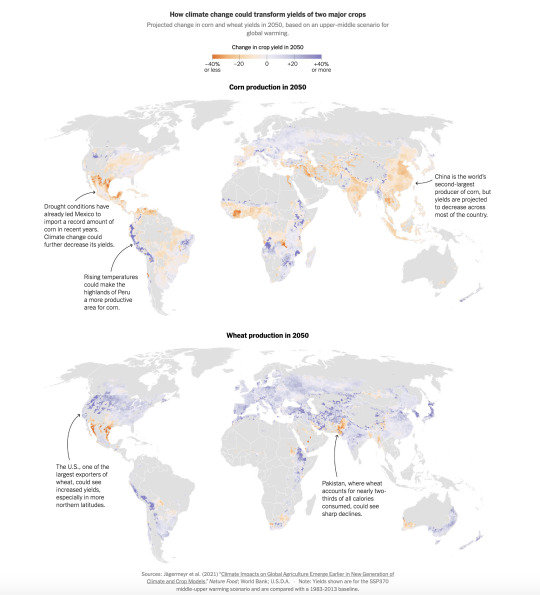

Food as You Know It Is About to Change. (New York Times Op-Ed)

From the vantage of the American supermarket aisle, the modern food system looks like a kind of miracle. Everything has been carefully cultivated for taste and convenience — even those foods billed as organic or heirloom — and produce regarded as exotic luxuries just a few generations ago now seems more like staples, available on demand: avocados, mangoes, out-of-season blueberries imported from Uruguay.

But the supermarket is also increasingly a diorama of the fragility of a system — disrupted in recent years by the pandemic, conflict and, increasingly, climate change. What comes next? Almost certainly, more disruptions and more hazards, enough to remake the whole future of food.

The world as a whole is already facing what the Cornell agricultural economist Chris Barrett calls a “food polycrisis.” Over the past decade, he says, what had long been reliable global patterns of year-on-year improvements in hunger first stalled and then reversed. Rates of undernourishment have grown 21 percent since 2017. Agricultural yields are still growing, but not as quickly as they used to and not as quickly as demand is booming. Obesity has continued to rise, and the average micronutrient content of dozens of popular vegetables has continued to fall. The food system is contributing to the growing burden of diabetes and heart disease and to new spillovers of infectious diseases from animals to humans as well.

And then there are prices. Worldwide, wholesale food prices, adjusted for inflation, have grown about 50 percent since 1999, and those prices have also grown considerably more volatile, making not just markets but the whole agricultural Rube Goldberg network less reliable. Overall, American grocery prices have grown by almost 21 percent since President Biden took office, a phenomenon central to the widespread perception that the cost of living has exploded on his watch. Between 2020 and 2023, the wholesale price of olive oil tripled; the price of cocoa delivered to American ports jumped by even more in less than two years. The economist Isabella Weber has proposed maintaining the food equivalent of a strategic petroleum reserve, to buffer against shortages and ease inevitable bursts of market chaos.

Price spikes are like seismographs for the food system, registering much larger drama elsewhere — and sometimes suggesting more tectonic changes underway as well. More than three-quarters of the population of Africa, which has already surpassed one billion, cannot today afford a healthy diet; this is where most of our global population growth is expected to happen this century, and there has been little agricultural productivity growth there for 20 years. Over the same time period, there hasn’t been much growth in the United States either.

Though American agriculture as a whole produces massive profits, Mr. Barrett says, most of the country’s farms actually lose money, and around the world, food scarcity is driving record levels of human displacement and migration. According to the World Food Program, 282 million people in 59 countries went hungry last year, 24 million more than the previous year. And already, Mr. Barrett says, building from research by his Cornell colleague Ariel Ortiz-Bobea, the effects of climate change have reduced the growth of overall global agricultural productivity by between 30 and 35 percent. The climate threats to come loom even larger.

It can be tempting, in an age of apocalyptic imagination, to picture the most dire future climate scenarios: not just yield declines but mass crop failures, not just price spikes but food shortages, not just worsening hunger but mass famine. In a much hotter world, those will indeed become likelier, particularly if agricultural innovation fails to keep pace with climate change; over a 30-year time horizon, the insurer Lloyd’s recently estimated a 50 percent chance of what it called a “major” global food shock.

But disruption is only half the story and perhaps much less than that. Adaptation and innovation will transform the global food supply, too. At least to some degree, crops such as avocados or cocoa, which now regularly appear on lists of climate-endangered foodstuffs, will be replaced or redesigned. Diets will shift, and with them the farmland currently producing staple crops — corn, wheat, soy, rice. The pressure on the present food system is not a sign that it will necessarily fail, only that it must change. Even if that progress does come to pass, securing a stable and bountiful future for food on a much warmer planet, what will it all actually look like?

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Long story short, like Florida and Louisiana, California's earthquakes and fires have caused insurance companies to have to pay out, the thing you pay them for. So they are dropping areas they deem particularly prone to natural disasters so they don't have to pay out when one hits.

Natural disasters are increasing because of climate change. But I bet you each of those insurance companies has had some form of "back to office" for workers who went remote during COVID lockdowns and is rolling out "AI" in one or more areas internally with zero care of the environmental impacts of those choices. To say nothing of the deforestation that has happened so they can send every adult in the country a mailed ad every other week.

Just a reminder, even before Silicon Valley was a thing California was the 7th largest economy in the world. It has some of the most prestigious universities in the world. It is the major producer of certain agricultural goods for the entire planet to say nothing of what it produces for the US grocery market. And wine, don't forget wine. People like to attack California, and there certainly is a massive amount that could improve there, but economic issues that arise from this situation will have a ripple effect across the world.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just a thought. You know how the price increase and the income not increasing as well happened before? And since everything was so costly, no one bought anything, so the economy got bad, people panicked, prices rose more, people still didn't buy, and everything crashed into the dirt?

According to History.com, The Great Depression's causes were, "The stock market, centered at the New York Stock Exchange on Wall Street in New York City, was the scene of reckless speculation, where everyone from millionaire tycoons to cooks and janitors poured their savings into stocks. As a result, the stock market underwent rapid expansion, reaching its peak in August 1929. By then, production had already declined and unemployment had risen, leaving stock prices much higher than their actual value. Additionally, wages at that time were low, consumer debt was proliferating, the agricultural sector of the economy was struggling due to drought and falling food prices and banks had an excess of large loans that could not be liquidated. The American economy entered a mild recession during the summer of 1929, as consumer spending slowed and unsold goods began to pile up, which in turn slowed factory production."

Another important quote from the article is this, "As consumer confidence vanished in the wake of the stock market crash, the downturn in spending and investment led factories and other businesses to slow down production and begin firing their workers. For those who were lucky enough to remain employed, wages fell and buying power decreased."

Sounds familiar, doesn't it? The US unemployment rate right now, according to the Department of Labor Statistics, is 4.2%. Wages are low. Thousands of workers were let go during Covid (and it seems hard right now to get a decent-paying job). Not to mention how everything is raising prices.

About a year and some ago, I could pay $150- $180 US dollars for basic food necessities and a few ingredients for cooking. I came back to the USA for the holidays and bought like 20 items? Maybe 15? It was $280 US dollars.

$280!!!!!! FOR HEALTHY FOOD!!!!! FOR ONE FUCKING RECIPE AND BREAKFAST!!!!

As an outsider of the USA, things don't have to be what it is now. You may not know it but there are so many countries out there that have affordable needs. Things can be better. Food doesn't have to cost so much, insurance doesn't have to cost so much and be so useless, and basic human needs shouldn't be a costly purchase.

I'd suggest watching Oversimplied's French Revolution (Part One & Two) and The Emu War beginning. From 1:20-1:53.

We need to learn history to not repeat the past but at this point, the past has been repeated one too many times. Be smart. Learn. Expand your horizons. And if anyone tells you "It is what it is" fucking bite them.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soil: The Secret Weapon in the Fight Against Climate Change - EcoWatch

www.ecowatch.com

Soil: The Secret Weapon in the Fight Against Climate Change

EcoWatch

7 - 8 minutes

By Claire O’Connor

Agriculture is on the front lines of climate change. Whether it’s the a seven-year drought drying up fields in California, the devastating Midwest flooding in 2019, or hurricane after hurricane hitting the Eastern Shore, agriculture and rural communities are already feeling the effects of a changing climate. Scientists expect climate change to make these extreme weather events both more frequent and more intense in coming years.

Agriculture is also an important — in fact a necessary — partner in fighting climate change. The science is clear: We cannot stay beneath the most dangerous climate thresholds without sequestering a significant amount of carbon in our soils.

Agricultural soils have the potential to sequester, relatively inexpensively, 250 million metric tons of carbon dioxide-equivalent greenhouse gasses annually — equivalent to the annual emissions of 64 coal fired power plants, according to National Academy of Sciences.

But we can’t get there without engaging farmers, turning a source of emissions into a carbon sink. Here are just a few of the ways the Natural Resources Defense Council works to encourage climate-friendly farming:

Creating New Incentives for Cover Crops: Cover crops are planted in between growing seasons with the specific purpose of building soil health. Despite their multiple agronomic and environmental benefits, adoption is low — only about 7% of U.S. farmland uses cover crops. NRDC is working to scale up cover cropping through innovative incentives delivered through the largest federal farm subsidy: crop insurance. We’ve worked with partners in Iowa and Illinois to launch programs that give farmers who use cover crops /acre off of their crop insurance bill. And partners in Minnesota and Wisconsin are exploring similar options. While we’re delighted at the benefit this program has for farmers in those individual states, we’re even more excited about the potential to scale this program to the 350 million acres that utilize subsidized crop insurance nationwide. A recent study suggests that cover crops sequester an average of .79 tons of carbon per acre annually, making cover crops one of the pillars of climate-friendly farming systems.

Supporting Carbon as a New “Agricultural Product”: Championed by Senator Ron Wyden, the 2018 Farm Bill created a new program, the Soil Health Demonstration Trial, that encourages farmers to adopt practices that improve their soil health, and tracks and measures the outcomes. NRDC worked alongside our partners at E2 and a number of commodity groups, farmer organizations, and agribusinesses to secure passage of this provision. The Demonstration Trial will create a new, reliable income stream — farmers will get paid for the carbon they sequester regardless of how their crops turn out, and it builds the data needed for confidence in any future carbon markets. USDA recently announced the first round of awards under this new program, totaling over million in investments to improve soil health. Senator Cory Booker has since drafted legislation that would increase funding for the program nearly 10-fold to 0 million annually; Representative Deb Haaland released a companion bill in the House.

Scaling up Regenerative Agriculture: Regenerative agriculture is an approach to farming that looks to work with nature to rebuild the overall health of the system. Regenerative farmers use a variety of tactics, including reduced chemical inputs, diverse crop and livestock rotations, incorporating compost into their systems, and agroforestry, among others. Our team is in the midst of interviewing regenerative farmers and ranchers to learn more about what’s working for them and what challenges they’ve faced in their shift to a regenerative approach. We’re planning to analyze our interview results and combine them with a literature review to identify what role NRDC could potentially play in helping to scale up regenerative farming and ranching systems. We’ll also be sharing quotes and photos from our interviews on social media every Friday starting in January, so stay tuned for some inspiring farm footage!

Supporting Organic Farmers: Organic agriculture by design reduces greenhouse gas emissions, sequesters carbon in the soil, does not rely on energy-intensive chemical inputs, and builds resiliency within our food system. Practices integrated into organic production will become increasingly more important in the face of a changing climate. NRDC supports organic farmers through policy initiatives like the Organic Farm-to-School program that was introduced in the California legislature last year. In the coming year, we’ll continue to work to support organic farmers in California.

Reducing Food Waste: Food waste generates nearly 3% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., and NRDC is working hard to reduce that number, and improve soil health in the process. Some of our policy proposals include securing passage of date labelling legislation to eliminate confusion about whether food is still good to eat, working with cities to reduce waste and increase rescue of surplus food, and supporting efforts at all levels to increase composting of food scraps. Adding compost to soils improves their ability to sequester carbon, store nutrients, and retain water. Composting food scraps also helps to “close the loop” on organic matter and nutrients by returning them to the agricultural production cycle, rather than sending that organic material to landfills, where it generates methane (a powerful climate pollutant).

Climate-friendly farming also offers a host of important co-benefits. For example, when farmers use complex crop rotations to break weed, pest, and disease cycles, they can reduce the amount of synthetic chemicals they need to use. When they use practices like cover crops, no-till, and adding compost to protect and restore the soil, they reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers that emit greenhouse gasses. And when farmers can reinvest the oppressive amount of money they had been previously spending on expensive, synthetic inputs into the additional labor required to carbon farm, they bring new jobs to economically-depressed rural areas.

Farmers understand better than many of us the harsh realities of climate change, regardless of their opinions about what’s causing those changes. And tight margins and trade wars make the potential of new value streams particularly attractive for farmers right now. By working alongside the farmers and farmworkers who tend the land, we can bring new allies into the fight against climate change, restore the health of our soil, and create a healthy, equitable, and resilient food system.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Land vs. House: What’s Better for Long-Term Value in Texas?

When it comes to real estate investment in Texas, one of the most debated topics among buyers, investors, and future homeowners is: Should I invest in land or a house? Both options offer long-term value, but which is better for you depends on your goals, budget, and how you see your future shaping up in the Lone Star State.

In this guide, you can read a proper breakdown of the pros and cons of both land and residential property ownership, what the Texas market trends indicate, and how you can make the most of your investment whether you're buying to live, rent, or build wealth.

Understanding the Appeal: Land vs. House in Texas

Texas is known for its vast open spaces, booming cities, and business-friendly environment. From urban hubs like Dallas and Houston to more affordable regions like San Antonio and Lubbock the property market is diverse and dynamic.

Buying land in Texas offers flexibility, potential appreciation, and fewer immediate responsibilities. On the other hand, buying a house provides immediate utility, potential rental income, and a place to call home.

So which offers more value long-term? Let’s explore both.

The Case for Buying Land in Texas

Pros of Buying Land:

Affordability: Raw land is often cheaper than developed property, especially in rural areas or just outside city limits.

Appreciation Potential: As Texas cities expand, undeveloped land close to urban growth corridors may rise significantly in value.

Low Maintenance: No structures mean no repair costs, property taxes are often lower, and insurance is minimal.

Custom Development: Land buyers can build their dream homes or invest in agricultural or commercial use with proper zoning.

Scarcity Over Time: As more land is developed, raw land becomes scarcer—potentially increasing its value in the long run.

Cons of Buying Land:

Lack of Immediate Use: Unless you are ready to build, the land doesn’t generate cash flow.

Zoning and Utility Access: You may face hurdles like securing permits, utility hookups, or rezoning.

Harder to Finance: Land loans are usually riskier for lenders, meaning higher interest rates or larger down payments.

Here is the Land Buying 101 guide that will let you explore the essential factors and considerations to keep in mind when purchasing land in San Antonio.

The Case for Buying a House in Texas

Pros of Buying a House:

Instant Functionality: Whether you are living in it or renting it out, a house has immediate use and return potential.

Equity Growth: As you pay off your mortgage, your equity increases. If home values rise, you build wealth even faster.

Rental Income: Texas has a strong rental market, especially in cities like Austin and San Antonio, creating reliable cash flow.

Tax Advantages: Mortgage interest and property taxes are deductible for homeowners in most cases.

Faster Resale: Homes are generally easier to sell than raw land, especially in areas with high demand.

Cons of Buying a House:

Higher Initial Costs: A house is a larger upfront investment, with costs like inspections, appraisals, and insurance.

Ongoing Maintenance: Homes require upkeep and repairs which sometimes can be subject to unexpected issues like plumbing or HVAC failure.

Market Fluctuation: While Texas is generally stable, real estate values can dip during economic downturns.

Texas Real Estate Trends: What Does the Market Say?

According to the Texas A&M Real Estate Center and local housing reports, Texas continues to see consistent demand in both residential and land markets. However, areas near rapidly growing cities like San Antonio, Austin, and Houston have shown especially strong land appreciation, driven by urban sprawl and population growth.

This means land close to infrastructure and future developments could be a smart long-term play. Conversely, houses within city limits offer better rental prospects and immediate resale potential.

Which Offers Better Long-Term Value?

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Here's a helpful breakdown to guide your decision:

Choose Land If:

You are thinking long-term, want lower entry costs, and are willing to wait or develop. Ideal for those who want to build or hold for future resale in high-growth areas.

Choose a House If:

You want a place to live or rent now, prefer a steady income, and are looking to build equity through appreciation and mortgage payments.

Many Texans are also choosing lease-to-own options, combining the benefits of both renting and ownership.

Final Thoughts: Build Your Future the Smart Way

Whether you invest in land or buy a house in Texas, real estate remains one of the most reliable paths to building wealth. The key is understanding your goals and how each option aligns with your lifestyle, financial plan, and risk tolerance.

For those looking to explore lease listings, down payment assistance, or flexible homeownership options in San Antonio and beyond, trust the expertise and personalized service offered by Zertuche Homes.

#Local Realtor San Antonio#Local Real Estate Agent in Bracken#Local Real Estate Agent in Garden Ridge#Local Real Estate Agent in Windcrest#San Antonio Property Management#Commission Structure#Buy a House in San Antonio#Lease Listing San Antonio

0 notes

Text

Best Transportation Service in India

In a country as vast and dynamic as India, transportation plays a vital role in enabling trade, connecting supply chains, and powering economic growth. From moving raw materials to delivering finished goods across thousands of kilometers, businesses rely heavily on logistics to stay competitive. Choosing the best transportation service in India can be the difference between success and stagnation.

Whether you're a small business owner or a large-scale manufacturer, finding a reliable transportation partner ensures on-time deliveries, reduced costs, and satisfied customers.

What is Transportation in Logistics?

Transportation in logistics refers to the movement of goods from one location to another — whether it’s from a factory to a warehouse, a distribution center to a retailer, or directly to the end customer. It involves different modes, including:

Road Transport – Trucks, trailers, and LCVs for domestic movement

Rail Transport – Cost-effective for heavy and bulk goods

Air Transport – Ideal for time-sensitive and high-value shipments

Sea Transport – Best suited for international and large-volume shipments

An efficient transportation service ensures speed, safety, and visibility at every stage of delivery.

Best Transportation Service Providers in India

Here are some of the top logistics companies offering the best transportation services in India, across various sectors and transport modes:

1. Blue Dart Express

Leading express and parcel logistics company

Strong last-mile delivery network with integrated air transport

Ideal for e-commerce and time-sensitive shipments

2. Delhivery

Tech-enabled logistics provider with strong pan-India reach

Offers part truckload (PTL), full truckload (FTL), and warehousing services

Preferred by online retailers and SMEs

3. Gati-KWE

Offers end-to-end surface express, air freight, and supply chain solutions

Strong presence in tier-1 and tier-2 cities

4. TCI Express

Focuses on express delivery and surface transportation

Specializes in high-speed freight services for industrial clients

5. VRL Logistics

One of India’s largest fleet operators

Known for reliability in long-haul transportation and cargo handling

6. Safexpress

Strong presence across 29,000+ pin codes

Offers B2B logistics with secure and time-definite deliveries

Why Choose a Professional Transportation Service in India?

Punctual Deliveries Timely deliveries help maintain inventory flow and customer satisfaction.

Nationwide Reach Leading companies offer access to even remote areas of India.

Cargo Safety Trained personnel and modern fleet management reduce damage or loss.

Technology Integration Real-time tracking, automated scheduling, and digital proof of delivery enhance efficiency.

Multi-Modal Capabilities Seamless integration between road, rail, air, and sea transport for optimized routes.

Key Industries Served

E-commerce & Retail – Fast-moving and high-volume shipping

Pharma & Healthcare – Temperature-sensitive and urgent transport

Automotive – Just-in-time delivery for parts and assemblies

FMCG – High-frequency shipments to urban and rural markets

Agriculture – Bulk goods and perishables requiring cold chain support

Choosing the Best Transportation Service in India

When selecting a transport partner, consider:

Fleet size and availability Insurance and cargo safety standards Route coverage and delivery timelines Industry experience Customer service and tech tools for tracking and support

Final Thoughts

As India moves toward becoming a $5 trillion economy, having a strong logistics backbone is more important than ever. The best transportation service in India isn’t just about moving goods—it’s about moving your business forward. Whether you’re scaling operations or expanding into new markets, reliable transport is your foundation for growth.

Need help with logistics or transportation planning? Connect with a trusted transport service provider and streamline your supply chain from start to finish.

0 notes

Text

Agriculture and Seasonal Jobs in Russia: Apply Through Verified Agencies in Pakistan

As the global job market evolves, overseas employment opportunities have become a vital source of income and career development for many skilled and unskilled workers in Pakistan. One of the rising destinations for jobseekers is Russia particularly in the agriculture and seasonal job sectors. Whether you're interested in working on large-scale farms, greenhouses, or food processing plants, Russia presents countless possibilities. Falisha Manpower, a trusted name in overseas employment services, has positioned itself as a leading Recruitment Agency for Russia in Pakistan, helping Pakistanis navigate the process of working abroad with complete transparency, legal documentation, and ethical recruitment procedures.

Why Russia Is a Growing Hub for Seasonal and Agriculture Jobs

Russia’s vast landscape, long agricultural seasons, and reliance on migrant labor have made it a hotspot for foreign workers, especially in sectors such as:

Crop farming (wheat, barley, corn, potatoes)

Greenhouse vegetable production

Fruit picking and orchard work

Dairy and livestock farming

Food processing and packaging

Warehouse labor and logistics in agricultural chains

Due to labor shortages and seasonal demand, employers in Russia actively seek reliable and hardworking individuals from Pakistan and other countries. For Pakistani workers, these opportunities offer competitive wages, accommodation, and in many cases, return airfare and health insurance.

Challenges Faced by Jobseekers Without the Right Recruitment Partner

While opportunities abound, many Pakistani workers face difficulties in finding legitimate employment due to:

Lack of verified job offers

Exploitative middlemen

Language barriers

Visa frauds and legal complications

Misunderstanding of Russian labor laws

This is where Falisha Manpower plays a pivotal role. As one of the Best Manpower Recruitment Agencies In Pakistan, Falisha ensures legal processing, employer verification, and pre-departure briefings that help Pakistani workers transition smoothly into their roles abroad.

What Makes Falisha Manpower Stand Out?

1. Verified Job Opportunities

Falisha Manpower works directly with licensed employers and government-approved partners in Russia. Every job offer is thoroughly screened to meet legal and ethical recruitment standards.

2. Legal Documentation & Visa Processing

Navigating Russia’s visa system can be complicated. Falisha ensures that every selected candidate receives full assistance in:

Preparing visa applications

Collecting legal documents

Coordinating with the Russian embassy

Securing work permits

As a Recruitment Agency for Russia in Pakistan, they eliminate the guesswork and stress involved in international paperwork.

3. Training and Language Support

Basic Russian language phrases and job-related instructions are taught to selected workers so they can integrate easily at the workplace. Falisha also offers orientation sessions on:

Cultural sensitivity

Workplace expectations

Health and safety standards

Workers’ rights in Russia

4. Affordable Fee Structure with No Hidden Charges

Many manpower agencies burden workers with hidden fees and illegal deductions. Falisha’s approach is transparent and aligned with Pakistan’s Bureau of Emigration regulations. Their ethical model allows workers to focus on earning and growing, not worrying about exploitation.

Popular Seasonal Job Categories for Pakistanis in Russia

1. Greenhouse Farm Workers

Jobs involve planting, harvesting, packaging, and maintaining vegetable crops like cucumbers, tomatoes, and lettuce in climate-controlled environments.

2. Orchard Pickers

Workers are hired seasonally to pick apples, pears, and cherries in vast Russian orchards, particularly in the southern and central regions.

3. Dairy Farm Assistants

Daily tasks include milking, feeding livestock, cleaning, and helping with dairy product preparation and distribution.

4. Food Packaging Staff

These roles are typically based in food processing plants where employees package and label fresh produce and processed items for retail markets.

5. Agricultural Technicians

For semi-skilled or skilled workers, there are positions involving soil management, equipment operation, and irrigation support.

Worker Benefits Secured Through Falisha Manpower

Falisha Manpower ensures that candidates placed in Russia benefit from:

Legal employment contracts

Competitive wages paid on time

Overtime pay (when applicable)

On-site accommodation or housing stipend

Workplace insurance and medical coverage

Return airfare (in many contracts)

Renewable contracts for long-term opportunities

By securing these benefits, Falisha guarantees that workers are not just employed, but empowered.

How to Apply Through Falisha Manpower?

Falisha has made the application process simple and efficient:

Visit the Website: Go to https://falishamanpower.com and explore current job openings.

Submit Your Application: Use the contact form or apply online with your CV, CNIC, and passport details.

Initial Screening: Falisha’s team will review your eligibility and match you with appropriate openings in Russia.

Interview & Selection: Shortlisted candidates are interviewed and briefed. Employer interviews (online or in-person) may also take place.

Documentation & Visa Process: Upon selection, the agency processes all required documents, including visa, ticket, and insurance.

Pre-Departure Orientation: Attend a training session before flying to Russia to understand job duties, rules, and safety guidelines.

Conclusion

Russia offers immense potential for Pakistani workers, especially in the agriculture and seasonal job sectors. However, finding legitimate and beneficial work opportunities abroad requires more than luck it requires the guidance of a reputable recruitment partner. Falisha Manpower has earned its name as one of the Best Manpower Recruitment Agencies In Pakistan through its commitment to transparency, legal compliance, and a worker-first approach. For anyone looking to work in Russia, whether seasonally or for a longer term, Falisha Manpower is the most trusted Recruitment Agency for Russia in Pakistan.

0 notes

Text

And why does America grow so much fucking corn? Well, several reasons, but dominant among them: Subsidised revenue insurance programs! "In 1949, government payments made up 1.4% of total net farm income — a measure of profit — while in 2000 government payments made up 45.8% of such profits. In 2019, farms received $22.6 billion in government payments, representing 20.4% of $111.1 billion in profits."

Bad year? Bad market? Get paid anyway. Grow corn! Why go to all the risk and expense of diversifying your operation to try and grow crops there's an actual market demand for when you could instead go all-in on corn and soybeans? Now so many farmers have gone down this route that if the government reduces those subsidies, it would devastate entire regions. In today's agricultural industry of broadacre cropping, most farming is done by massive, expensive, highly specialized machinery. You can't just pivot, because you're in debt on giant machines that really only work on corn. So the government isn't going to cut the subsidies. So more farmers are going to go all-in on the safe bet that is corn. It's a horrible self-perpetuating cycle.

(Source for quote and image: https://usafacts.org/articles/federal-farm-subsidies-what-data-says/)

I will write this thought about Veganism and Classism in the USA in another post so as to not derail the other thread:

There are comments in the notes that say meat is only cheaper than plant based foods because of subsidies artificially lowering the price of meat in the United States. This is...part of the story but not all of it.

For my animal agriculture lab we went to a butcher shop and watched the butcher cut up a pig into various cuts of meat. I have had to study quite a bit about the meat industry in that class. This has been the first time I fully realized how strongly the meat on a single animal is divided up by socioeconomic class.

Like yes, meat cumulatively takes more natural resources to create and thus should be more expensive, but once that animal is cut apart, it is divided up between rich and poor based on how good to eat the parts are. I was really shocked at watching this process and seeing just how clean and crisp an indicator of class this is.

Specifically, the types of meat I'm most familiar with are traditionally "waste" parts left over once the desirable parts are gone. For example, beef brisket is the dangly, floppy bit on the front of a cow's neck. Pork spareribs are the part of the ribcage that's barely got anything on it.

And that stuff is a tier above the "meat" that is most of what poor people eat: sausage, hot dogs, bologna, other heavily processed meat products that are essentially made up of all the scraps from the carcass that can't go into the "cuts" of meat. Where my mom comes from in North Carolina, you can buy "livermush" which is a processed meat product made up of a mixture of liver and a bunch of random body parts ground up and congealed together. There's also "head cheese" (made of parts of the pig's head) and pickled pigs' feet and chitlin's (that's made of intestines iirc) and cracklin's (basically crispy fried pig skin) and probably a bunch of stuff i'm forgetting. A lot of traditional Southern cooking uses basically scraps of animal ingredients to stretch across multiple meals, like putting pork fat in beans or saving bacon grease for gravy or the like.

So another dysfunctional thing about our food system, is that instead of people of each socioeconomic class eating a certain number of animals, every individual animal is basically divided up along class lines, with the poorest people eating the scraps no one else will eat (oftentimes heavily processed in a way that makes it incredibly unhealthy).

Even the 70% lean ground beef is made by injecting extra leftover fat back into the ground-up meat because the extra fat is undesirable on the "better" cuts. (Gross!)

I've made, or eaten, many a recipe where the only thing that makes it non-vegan is the chicken broth. Chicken broth, just leftover chicken bones and cartilage rendered and boiled down in water? How much is that "driving demand" for meat, when it's basically a byproduct?

That class really made me twist my brain around about the idea of abstaining from animal products as a way to deprive the industry of profits. Nobody eats "X number of cows, pigs, chickens in a lifetime" because depending on the socioeconomic class, they're eating different parts of the animal, splitting it with someone richer or poorer than they are. If a bunch of people who only ate processed meats anyway abstained, that wouldn't equal "saving" X number of animals, it would just mean the scraps and byproducts from a bunch of people's steaks or pork chops would have something different happen to them.

The other major relevant conclusion I got from that class, was that animal agriculture is so dominant because of monoculture. People think it's animal agriculture vs. plant agriculture (or plants used for human consumption vs. using them to feed livestock), but from capitalism's point of view, feeding animals corn is just another way to use corn to generate profits.

People think we could feed the world by using the grain fed to animals to feed humans, but...the grain fed to animals, is not actually a viable diet for the human population, because it's literally just corn and soybean. Like animal agriculture is used to give some semblance of variety to the consumer's diet in a system that is almost totally dominated by like 3 monocrops.

Do y'all have any idea how much of the American diet is just corn?!?! Corn starch, corn syrup, corn this, corn that, processed into the appearance of variety. And chickens and pigs are just another way to process corn. That's basically why we have them, because they can eat our corn. It's a total disaster.

And it's even worse because almost all the USA's plant foods that aren't the giant industrial monocrops maintained by pesticides and machines, are harvested and cared for by undocumented migrant workers that get abused and mistreated and can't say anything because their boss will tattle on them to ICE.

#agriculture#monoculture#economics#Many countries have problems with lack of agricultural diversity due to government subsidy programs gone wrong#but America's pretty special#in Arizona specifically they grow a crazy amount of cotton#it's a desert#Cotton needs a ton of water#but due to circumstances based in the fucking CIVIL WAR#the self-perpetuating cycle of growing cotton for subsidies is so deeply entrenched in the region's economy that nobody's game to change it#so they're just draining the Colorado river to water cotton plants#like America's cotton and sugar subsidies are so extreme that they actually violate some international trade conventions#they almost got in trouble for it but they made some sneaky deals with the countries objecting and now those countries#also get to do illegal subsidies without getting in trouble#yay#problem solved#sigh

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Plow Together Rise Together The Co-op Spirit

Farming is more than a livelihood it's a way of life. But for many small and medium-scale farmers, challenges like rising costs, unpredictable markets, and limited access to technology often make this life uncertain. That’s where agricultural cooperatives come in. They offer a proven way for farmers to join hands, share resources, and grow stronger together. In this article, we explore how cooperatives work, why they matter, and how they are transforming lives from the soil up.

Chapter 1: What is a Cooperative?

A cooperative is not just a business it's a partnership among farmers. In a co-op, each member owns a share and has a voice. Decisions are made together, and profits are shared fairly. This model ensures that no farmer is left behind, and everyone moves forward as one.

Types of Agricultural Cooperatives:

Marketing Cooperatives: Help sell produce at better prices.

Supply Cooperatives: Provide affordable seeds, fertilizers, and tools.

Credit Cooperatives: Offer loans at low interest.

Processing Cooperatives: Add value through storage, packaging, or manufacturing.

Co-ops are built on the values of democracy, self-help, equality, and solidarity the very values farmers hold dear.

Chapter 2: Why Farmers Need Cooperatives

Fair Prices for Produce: On their own, farmers often have to accept low prices from middlemen. In a co-op, they negotiate better prices as a group.

Lower Costs of Inputs: Bulk buying of seeds, agrochemicals, and tools through a co-op reduces costs significantly.

Access to Credit and Insurance: Many co-ops have tie-ups with banks and microfinance institutions. This makes credit more accessible and affordable.

Training and Innovation: Co-ops often organize workshops on sustainable farming, greenhouse techniques, crop rotation, and soil testing.

Government Schemes and Subsidies: Co-ops make it easier to avail subsidies, grants, and schemes meant for farmers.

Chapter 3: Real Farmers, Real Stories

Let’s look at how cooperatives have changed the lives of real farmers:

Ramu from Maharashtra struggled to get fair rates for his onions. After joining a co-op, his group set up a grading unit and began selling directly to cities. His income doubled.

Sunita Devi in Bihar used to borrow at high interest from local moneylenders. Her cooperative helped her get a low-interest loan and taught her how to manage a group vermicompost unit. Today, she trains other women farmers.

Gurdeep Singh in Punjab joined a dairy cooperative. With better veterinary support and a collective chilling plant, his milk yields improved and he started earning regularly.

These stories prove that when farmers plow together, they truly rise together.

Chapter 4: Challenges Faced by Cooperatives

While co-ops offer many benefits, they also face challenges:

Lack of Awareness: Many farmers still don’t know how co-ops work or how to join one.

Poor Management: Some cooperatives fail due to weak leadership or lack of training.

Limited Infrastructure: Without storage, transport, or processing units, co-ops can’t reach their full potential.

Political Interference: In some cases, politics hampers the smooth functioning of cooperatives.

But these problems can be solved with better training, government support, and farmerparticipation.

Chapter 5: How to Start or Join a Cooperative

Form a Group: Gather a group of like-minded farmers.

Register Legally: Follow your state’s cooperative registration process.

Create a Plan: Decide your goals marketing, input supply, processing, etc.

Raise Capital: Pool small amounts or apply for initial grants.

Elect Leaders: Choose a committee with honest and capable members.

Keep Records: Maintain transparency in accounts and meetings.

Or, if a co-op already exists in your area, reach out and become a member. Attend meetings, participate in decisions, and make your voice count.

Chapter 6: Government Support for Cooperatives

Governments at both the state and central level support cooperatives through:

NABARD loans and schemes

Subsidies on cold storage and transport

Training programs and workshops

Digital platforms for marketing and procurement

With schemes like the E-NAM portal, Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs), and AgriInfrastructure Fund, the time has never been better to join or form a co-op.

Chapter 7: The Role of Youth and Women

The future of cooperatives lies in the hands of young farmers and women.

Youth bring energy, education, and technology.

Women add strength, discipline, and community spirit.

Cooperatives must train and involve the next generation to stay strong. Digital literacy, social media marketing, organic farming, and precision agriculture are all areas where youth can shine within co-ops.

Chapter 8: Green and Smart Co-ops

Many cooperatives today are adopting green and smart farming techniques:

Greenhouse farming

Drip irrigation

Solar-powered equipment

Organic inputs

App-based market linkages

These not only increase profits but also protect the planet. Co-ops can play a major role in climate-resilient agriculture.

Conclusion

To every farmer reading this your voice matters, your harvest matters, and your future matters. Alone, challenges may seem big. But together, with the spirit of agricultural cooperative , we can overcome anything.

Plow together. Rise together. Whether it's better prices, modern techniques, or shared success cooperatives are the wayforward. Let’s not just grow crops let’s grow unity, prosperity, and strength.

0 notes

Text

How Rural Sales Training Can Boost Your Agribusiness Revenue in 2025

In New Zealand's fast-changing rural economy, agribusinesses face growing pressure to meet sales targets while dealing with supply chain challenges, seasonal demands, and shifting customer expectations. One proven way to drive consistent revenue growth is through rural sales team training in New Zealand. In this blog, we’ll explore how working with the right rural sales training companies in New Zealand can help you sharpen your team’s skills, increase conversions, and align your sales strategy with 2025 goals — all in a practical, human-focused way.

What Are the Benefits of Rural Sales Training in New Zealand?

Many agribusiness owners assume sales skills come naturally or through on-the-job experience. But the rural sector is a unique space — relationships matter, technical understanding is critical, and trust takes time.

Here are some key benefits of rural sales training specific to New Zealand's market:

Increased confidence when dealing with technical products (e.g., agri-tech, fertilisers, irrigation tools)

Better engagement with farmers and rural decision-makers through tailored communication

Stronger objection handling and closing techniques relevant to long sales cycles

Consistency across your team, especially when managing remote or regional reps

Rural sales training provides structure, strategy, and soft skills that reflect the reality of selling in agricultural settings.

How Can Training Improve the Performance of a Rural Sales Team?

When your sales reps are scattered across regions, their performance can vary widely. A team-based training approach closes skill gaps and helps your people stay aligned.

With structured rural sales team training in New Zealand, you can:

Set clear performance expectations and KPIs for the whole team

Use training to role-play real-life scenarios, helping reps feel prepared

Develop shared sales language and tools so your brand speaks consistently

Train new hires faster by integrating them into a clear framework

Increase cross-team collaboration and accountability

For instance, the Rural Sales Manager Mastery Programme offers guidance to upskill team leaders so they can mentor others effectively — a smart move in 2025’s competitive talent landscape.

What Should I Look for in Rural Sales Training Companies in New Zealand?

Not all training providers understand rural markets. Before selecting a programme or company, consider:

Experience with rural and agribusiness sectors

Trainers who have worked directly in rural sales roles

Programmes that are customised, not generic

Options for team-wide training and individual coaching

Case studies or references from businesses similar to yours

One example of such a provider is Rural Sales Success, which offers tailored development for sales professionals working in the rural economy. Their programme invitation outlines how they approach rural-specific training challenges.

Is Team-Based Rural Sales Training Worth the Investment in 2025?

Absolutely — especially as agribusinesses gear up for a data-driven, digitally supported future. A team that sells better doesn’t just increase revenue — they reduce customer churn, identify upsell opportunities, and represent your brand more effectively.

In 2025, investing in rural sales team training in New Zealand also means staying ahead of:

Industry consolidation — where fewer players mean more competition

Climate and compliance changes — requiring smarter, trust-based sales

Digital adoption — using CRMs, remote selling tools, and analytics more efficiently

The payoff? You get a team that can sell with empathy, credibility, and results.

What Types of Agribusinesses Need Rural Sales Training the Most?

Based on common Quora and Google searches, here are examples of businesses that benefit most from rural sales development:

Fertiliser and chemical companies with large field sales teams

Rural insurance providers wanting stronger regional penetration

Agri-tech businesses selling high-ticket products

Animal health product distributors

Farm equipment and irrigation solution providers