#Washington seminary

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Graphic, England, February 26, 1927

Image © The British Library Board.

#saresmusings#painting#boyishbob#extreme high heels#bad manners#slang#1920s#1927#flappers#atlanta ga#feminine sins#women’s history#Washington seminary#modern girl#for you page#the graphic

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"[David] Dellinger meanwhile continued to speak out against the war, riding the rails and hitchhiking as needed to reach whoever would listen. In delivering an antiwar speech to a Christian student conference in Ohio over the Christmas break of 1941–42, he had met lively, twenty-one-year-old Elizabeth Peterson, a minister’s daughter known as Betty, whom he would quickly marry. Both were radical Christians with a demonstrated commitment to activism. And despite two brothers in the armed forces, Betty was a pacifist. “David was my ideal,” she recalled years later.

He believed in voluntary poverty, which was something I was coming to after working in a migrant camp one summer. And he believed in communal living, which I felt was closer to the original idea of Christian living.

She could not possibly have known what she was in for, yet despite years of trials their marriage would endure. It did so despite the burdens of five children, the lack of money, the notoriety, David’s protracted absences, and infidelities by both parties. It endured even though, as Betty later told an interviewer, “I was not active in David’s causes.” It even survived a period of separation late in life, when decades of accumulated grievances and rising feminist consciousness drove her to explore living apart. David, too, came to feminism as time went by, but in 1941 it wasn’t a paramount concern. He was, with his fellow male radicals, the creature of an era when only a quarter of women worked outside the home, and ideas about gender roles were different. It’s not clear that Betty had any more feminist consciousness in those days than he did. She could not know the fullness of the future when she got married, and she knew relatively little about her fiancé when they were wed. She likely knew nothing of his bisexuality and was even ignorant of his family background:

He hid a lot from me before we got married. I didn’t know he’d gone to Yale. I didn’t know his family was very well off. I was mending his pants the day before we got married because there was a hole in the knee.

But she knew he was a draft resister, and that his continued resistance meant another arrest was likely. He’d already told her how, hitchhiking west for his own wedding in Seattle, the police had arrested him in the Sierra Nevada mountains because they thought he had helped steal the car he was riding in. He was innocent, of course, but, worried about his lack of a draft card, decided to risk escaping through the window, which involved leaping onto a nearby fire escape. Still athletic, he managed to get away. Once married, he and Betty took a bus to Salt Lake City (in order to disguise their real transportation plans from her parents) and then hitchhiked the rest of the way across the country, including a stop in Chicago to visit Union Eight chums. They covered the last few miles on foot, suitcases in hand, arriving at the ashram exhausted. Betty had never been east of Detroit, never stayed in a hotel or motel, never hitchhiked. Years later she called the journey “traumatic.” As a newlywed, she now had the communal living she would later say she had wished for. “It was quite a cultural shock,” she said. There was little privacy, and a bunch of people with whom to work out household chores such as cooking, cleaning, and maintaining the building, not to mention all the other exigencies of group living. But there was also teamwork on the ashram’s outreach programs and cooperative store, among many other ventures. Dave for a while worked the graveyard shift five nights a week at a big commercial bakery to bring in money. Dallas and Benedict worked there, too (but the latter soon moved on to a similar project in Detroit). Dellinger insisted on being paid in cash so as not to contribute to the war effort through his taxes, a policy he would follow for the rest of his working life.

Life at the ashram wasn’t easy for women, especially for Betty. “She was the most fragile of the group,” Henry Harvey, who lived at the ashram at the time, observed in a 1988 interview. Harvey was a pacifist and Union Theological alumnus whose mother was first cousin to the secretary of war, Henry Stimson. Evidently young Harvey came from money; he and fellow Union student Francis Hall had put up $1,000 each to buy the house, according to Willa Winter. Told that Betty was still married to Dellinger after all those years, the elderly Harvey said with a laugh: “She’s a lot tougher than I thought.” Betty’s focus was homemaking, she would recall, and there was plenty of it to do. Draft resisters slept on floors and sofas, antiwar meetings were held, and supporters including Dorothy Day came out from the city. “We were deluged with visitors,” Dellinger writes, many of them staying for days or weeks. Among residents, there was continual turnover. The ashram was a well-known center for draft resisters and their supporters, and as the war progressed the FBI hauled away one resister after another. Virtually all the men present—and of course their loved ones—lived under the cloud of future arrest. “Every man there was either on his way from prison or on his way to prison,” Betty recalled. “Every woman there was related to one of these men and had that sense of never knowing when it was going to happen…There was quite a bit of anxiety.” Sutherland was arrested at the ashram in July of 1942. Benedict was picked up in Detroit in 1943 and would serve a second, personally quite consequential prison term at Danbury. Dallas, too, would be back in custody before long. “The FBI was always floating around,” he recalled years later. “It got so we could spot them anywhere.”

Dave and Betty knew his time was coming, but he didn’t lay low or move far away. On the contrary. In the first few months of 1942, by which time his father was chairman of the Boston United War Fund, Dellinger had joined the War Resisters League in a move emblematic of his increasingly secular radicalism. He would be joined there by many of his fellow war resisters, who were eventually to take over the place. Meanwhile he launched his own miniature antiwar organization, the People’s Peace Now Committee, which conducted small public protests against the war that all parties were prosecuting with such terrible ferocity around the world. Prospects for peace seemed to grow worse in January of 1943, when FDR was flown secretly to a conference with Winston Churchill in Casablanca. After the meetings, Roosevelt made public a notion previously discussed among the Allies privately: that they would require from the Axis powers “unconditional surrender” in order to end the war. The news dismayed pacifists, who hoped that a negotiated end to the fighting might save countless lives. The People’s Peace Now campaign held small protests in Newark and outside the Capitol in Washington. “Month after month the peoples of Europe and Asia are being shattered by mass bombing raids, deliberate starvation and total war,” said a leaflet from Dellinger’s group. In a poke to the eye of Selective Service authorities, the leaflet added: “Peaceful Americans have been conscripted to help commit these acts of destruction.”

On April 6, 1943, the twenty-sixth anniversary of U.S. entry into the previous world war, Betty and David attended a Peace Now protest in Washington, outside the Capitol, where they distributed leaflets saying that “Truth and Brotherhood will not be helped by Unconditional Surrender.” The flyers predicted Hitler’s overthrow by the German people and called for an end to anti-Semitism, Jim Crow, and colonial exploitation. (Police confiscated leaflets and signs but made no arrests.) Dellinger attended other antiwar events as well, each time putting himself further at risk. He and Betty, knowing what was ahead, decided quite deliberately to have a baby. Betty’s first pregnancy ended in a miscarriage, but she managed to conceive again.

The whole time, her husband had been engaged in a tussle with his local draft board, which conscripted him just a month after his release from prison on the basis of the registration form completed on his behalf—and against his will—by Danbury’s warden. After ignoring a series of official notices, Dellinger finally wrote back explaining his religious objections to war and pointing out that he’d already served a prison term for his stance. In 1942, his Newark draft board responded with a furious condemnation of conscientious objectors:

Citizenship should be taken from them regardless of their birthplace and, as soon as it is practicable, all such should be removed from the soil they refuse to defend…Cowards, slackers, and hypocrites, who hide behind so-called conscientious scruples, must be denied membership in a free society. We owe it to our fighting men.

A.J. Muste rose to Dellinger’s defense, writing to Hershey and Biddle to suggest the removal of the board members, whose words he feared could incite violence against COs, and who appeared either ignorant of the law or eager to flout it. “Unfortunately,” Muste added, “a good many members of local boards throughout the country have expressed similar opinions regarding conscientious objectors.” The difference is that those other unlucky COs didn’t have organized pacifism, what little there was of it, in their corner. Dellinger’s corner was not an easy one to inhabit, as Muste would soon learn.

Later that summer the Dellingers risked arrest again at another antiwar event, attended by about thirty people, in downtown Newark, where they encountered no interference. But when they returned the next day for another protest, Dellinger reports, police confiscated their materials. Andwhen they returned home to 37 Wright Street, federal agents waiting there arrested him, probably on July 7, 1943. In custody, he refused to pay bail— another lifelong practice, albeit with exceptions. “I usually refuse because I believe the amount of money that a person can command should not determine whether or not he or she stays in jail,” he wrote later, describing defendants who can’t make bail as “hostages” held “for a ransom that neither they nor their families or friends are able to pay.” Betty, pregnant, went to see the judge, explained her husband’s point of view, and Dave was soon free on his own recognizance. She picked him up in “a flamboyant new sports car” driven by their friend Louis McMillan, a naval lieutenant in uniform who nonetheless supported the Dellingers’ work in Newark. Dellinger was borne away from jail by capital in concert with military power, but he still managed to enjoy the ride." - Daniel Akst, War By Other Means: How the Pacifists of World War 2 Changed America for Good. New York: Melville House, 2022. p. 220-224

#conscientious objectors#world war ii#united states history#draft dodgers#draft evasion#war resisters#pacifism#reading 2024#anti-war#american prison system#seminary students#new york#newark#ashram#union theological seminary#washington dc#seattle

0 notes

Text

THURSDAY HERO: Johan Weidner

Johan “Jean” Weidner was a Dutch businessman who created an extensive underground rescue network and saved the lives of 800 Jews and 112 downed Allied aviators.

Born in Brussels in 1912 to Dutch parents, Jean grew up in Switzerland in a devout Seventh-Day Adventist home. His father, a minister who taught Greek and Latin at a church seminary, wanted Jean to become a clergyman but instead he decided to go into business. He moved to Paris in 1935 and started an import-export textile firm.

When the Germans occupied Paris in 1940 Jean dropped everything and fled to Lyon in unoccupied France. He had to abandon his company, so he started a new one in Lyon.

In 1941, as the situation for Jews and other enemies of the Nazi war machine grew more dire, Jean took action. He created an underground network secretly run out of his textile factory. To facilitate escape to Switzerland, Jean opened a second branch of his business in Annecy, near the Swiss border. The route was dotted with safe houses and locals sympathetic to the Resistance who sheltered the refugees and helped them cross the border.

Known as Dutch-Paris, the network Jean created became one of the most effective resistance groups during war. Also called “the Swiss Way,” the network’s mission was to rescue people targeted by the Nazis by hiding them until they could help them escape to a neutral country.

Jean was leader of 330 men, women and teenagers working clandestinely in occupied countries of Western Europe as well as in Switzerland.

Dutch-Paris was constantly in need of funds to support their extensive activities, and Jean made a deal with the Dutch ambassador to Switzerland. The Dutch government-in-exile in London would fund the rescue operations if Jean 1) expanded the escape route to reach all the way to Spain and 2) used the route to convey intelligence on microfilm between Dutch resistance groups. Jean agreed to the terms and the expanded network began operating in November 1943.

In January of 1944 they began rescuing downed Allied aviators, an especially dangerous operation because it attracted the attention of German military intelligence officers. In only a month they saved over 112 pilots before tragedy struck. In February 1944, a young Dutch woman working as a courier was arrested by the French police and turned over to the Gestapo. They tortured her physically and psychologically, and threatened her family. She cracked under pressure and gave up names of her colleagues colleagues in the Dutch-Paris network.

Germans started arresting members of Dutch-Paris, including Jean’s sister Gabrielle. Over the next few months, many of the rescuers were sent to concentration camps, where at least forty of them were murdered. Gabrielle survived until liberation by the Russians, but she was so malnourished that she died days later.

Jean was able to escape capture long enough to rebuild networks and continue his rescue operations. In Toulouse he was arrested by the French police, but he escaped before they were able to transfer him to the Germans.

France was liberated in November 1944 and Jean was invited to London by Queen Wilhemina to inform her about the Dutch-Paris route, and the situation for Dutch civilians in areas occupied by the Germans. He was made a Captian in the Dutch Armed Forces but after the war he was let go by the Dutch government for not being a professional policeman. Jean returned to his textile business, and in 1955 emigrated to the United States where he and his wife operated a chain of health food stores for several decades.

He received multiple awards for his wartime heroism including the US Medal of Freedom, the Croix de Guerre and the Legion d’honneur. He was honored as Righteous Among the Nations by Israeli Holocaust Memorial Yad Vashem, and a grove of trees was planted in his name. In 1993, at the opening of the United States Holocaust Museum in Washington DC, he was one of seven people chosen to light candles honoring rescuers.

Jean Weidner died in 1994 in Southern California. Abraham Foxman, then National Director of the ADL said, “John Weidner lived his entire life giving back… Until his death, he lived a life of selflessness and service, working tirelessly to make the world a better place.”

For creating an underground escape route for victims of the Nazis, and saving hundreds of lives, we honor Jean Weidner as this week’s Thursday Hero.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

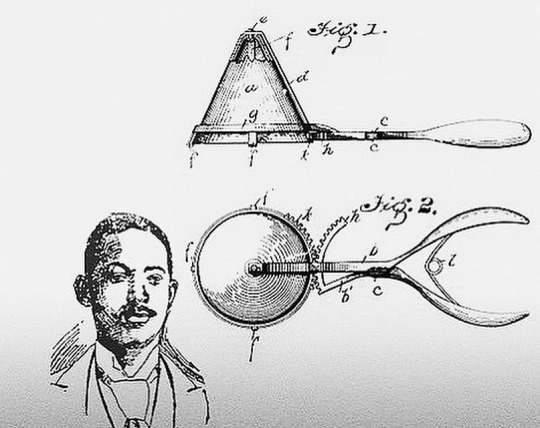

Today In History

Alfred L. Cralle was a Black businessman and inventor, who invented the ice cream scooper, patent #576,395 on this date February 2, 1897.

Alfred L. Cralle was born in Kenbridge, Lunenburg County, Virginia just after the end of the American Civil War. He attended local schools and worked with his father in the carpentry trade as a young man, becoming interested in mechanics. Cralle went to Washington, D.C., and attended Wayland Seminary, one of several schools founded by the American Baptist Home Mission Society to help educate Blacks after the American Civil War.

He settled in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he first served as a drug store and hotel porter. Alfred noticed that servers at the hotel had trouble with ice cream sticking to serving spoons, and he developed an ice cream scoop.

The patented “Ice Cream Mold and Disher” was an ice cream scoop with a built-in scraper to allow for one-handed operation. Cralle’s functional design is in modern ice cream scoops. He later became a general manager for the Afro-American Financial, Accumulating, Merchandise, and Business Association.

CARTER™️ Magazine

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more … November 15

1919 – Paul Moore, Jr. (d.2003) was a bishop of the Episcopal Church and served as the 13th Bishop of New York from 1972 to 1989. During his lifetime, he was perhaps the best known Episcopal cleric in the United States, and among the best known of Christian clergy in any denomination.

Moore joined the Marine Corps in 1941. He was a highly decorated Marine Corps captain, a veteran of the Guadalcanal Campaign during World War II earning the Navy Cross, a Silver Star and a Purple Heart.

Returning home after the War, Moore was ordained in 1949 after graduating from the General Theological Seminary in New York City. Moore was named rector of Grace Church Van Vorst, an inner city parish in Jersey City, New Jersey, where he served from 1949 to 1957. There he began his career as a social activist, protesting inner city housing conditions and racial discrimination. He and his colleagues reinvigorated their inner city parish and were celebrated in the Church for their efforts.

In 1957, he was named Dean of Christ Church Cathedral in Indianapolis, Indiana. Moore introduced the conservative Midwestern capital to social activism through his work in the inner city. Moore served in Indianapolis until he was elected Suffragan Bishop of Washington, D.C., in 1964.

During his time in Washington he became nationally known as an advocate of civil rights and an opponent of the Vietnam War. He knew Martin Luther King, Jr., and marched with him in Selma and elsewhere. In 1970, he was elected as coadjutor and successor to Bishop Horace Donegan in New York City. He was installed as Bishop of the Diocese of New York in 1972 and held that position until 1989.

Moore was widely known for his liberal activism. Throughout his career he spoke out against homelessness and racism. He was an effective advocate of the interests of cities, once calling the corporations abandoning New York "rats leaving a sinking ship". He was the first Episcopal bishop to ordain an openly homosexual woman as a priest in the church. In his book, Take a Bishop Like Me (1979), he defended his position by arguing that many priests were homosexuals but few had the courage to acknowledge it.

His first wife, Jenny McKean Moore died of colon cancer in 1973. Eighteen months later Moore married Brenda Hughes Eagle, a childless widow twenty two years his junior. She died of alcoholism in 1999. It was she who discovered his bisexual infidelity, around 1990, and made it known to his children, who kept the secret, as he had asked them to, until Honor Moore's revelations in 2008.

Honor Moore, the oldest of the Moore children and a bisexual, revealed that her father was himself bisexual with a history of gay affairs in a story she wrote about him in the March 3, 2008 issue of The New Yorker and in the book The Bishop's Daughter: A Memoir. In addition, she described a call she received six months after her father's death from a man, identified in the article by a pseudonym, who was the only person named in Moore's will who was unknown to the family. Honor Moore learned from the man that he had been her father's longtime gay lover and that they had traveled together to Patmos in Greece and elsewhere.

1939 – Réal Lessard was born in Mansonville, Canada. He led a quiet life until he was eighteen years old. He he had always dreamed of traveling and becoming an artist.

Hitchhiking, he set out to conquer the world. In Miami, he met his fate: Fernand Legros. They began an uneven relationship. Legros occasionally accused Lessard of infidelity, although he himself slept with other men. An unscrupulous art dealer, Legros quickly discovered the innate talent of Réal Lessard who painted, without knowing it, in the manner of great Fauves fromturn of the century.

Promising an art show that would never happen, Legros sold Lessard's paintings, without the knowledge of the artist, as authentic Dufy, Matisse, Derain, Van Dongen, Modigliani and many others. He managed to get everyone in his pocket – experts, beneficiaries, and even widows of the painters. The world was awash with raw Réal Lessard.

Reál and Legros on the beach at Cannes

Lessard discovered the scam but dared not speak. It will not take long for the Association of Art Dealers of Americans to intervene and the affair would culminate in a trial. Real was cleared but he had to prove that thousands of paintings, dating from his first from his meeting with Legros, were from his brush.

1941 – Holocaust SS chief Heirich Himmler orders the arrest and deportation to concentration camps of all homosexuals in Germany, with the exception of certain top Nazi officials. He also announced a decree that any member of the Nazi SS or the police who had sex with another man would be put to death.

1952 – ONE, the official publication of the Mattachine Society, Articles of Incorporation signed in the Los Angeles law office of Eric Julber. In January 1953 ONE, Inc. began publishing ONE Magazine, the first U.S. pro-gay publication, and sold it openly on the streets of Los Angeles. In October 1954 the U.S. Post Office Department declared the magazine 'obscene'. ONE sued, and finally won in 1958, as part of the landmark First Amendment case, Roth v United States. The magazine continued until 1967.

ONE also published ONE Institute Quarterly (now the Journal of Homosexuality). It began to run symposia, and contributed greatly to scholarship on the subject of same-sex love (then called homophile studies').

ONE readily admitted women, and Joan Corbin (as Eve Elloree), Irma Wolf (as Ann Carrl Reid), Stella Rush (as Sten Russell), Helen Sandoz (as Helen Sanders), and Betty Perdue (as Geraldine Jackson) were vital to its early success. ONE and Mattachine in turn provided vital help to the Daughters of Bilitis in the launching of their newsletter The Ladder in 1956. The Daughters of Bilitis was the counterpart lesbian organization to the Mattachine Society, and the organizations worked together on some campaigns and ran lecture-series. Bilitis came under attack in the early 1970s for 'siding' with Mattachine and ONE, rather than with the new separatist feminists.

In 1965, ONE separated over irreconcilable differences between ONE's business manager Dorr Legg and ONE Magazine editor Don Slater. After a two-year court battle, Dorr Legg's faction retained the name "ONE, Inc." and Don Slater's faction retained most of the corporate library and archives.

1954 – Poet and Carl Sandburg Prize winner, Rane Ramón Arroyo born (d.2010); Arroyo was an American poet, playwright, and scholar of Puerto Rican heritage descent who wrote numerous books and received many literary awards. He was a professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Toledo in Ohio. His work deals extensively with issues of immigration, Latino culture and homosexuality. Arroyo was out Gay and frequently wrote self-reflexive, autobiographical texts. He was the long-term partner of the American poet Glenn Sheldon.

He published ten books of poems, a book of short stories, and a collection of selected plays. Arroyo said: "No one is more surprised than I at being read in my lifetime." Arroyo's most recent books include "The Buried Sea: New & Selected Poems" , and "The Sky's Weight." "Midwest Challenge" was nominated for a 2009 Pushcart Prize.

The Umbrella Class assignment: bring in an object that tells your life story. Friends bought a music box, a painting of a cowboy being tamed by a mountain, a jeweled Buddha, but I was poor and had to risk being modest. Then I saw the broken umbrella, turned it inside out and exposed its ribs. There was a pun in it, rain and Rane, but the teacher said, how sad is your life? The other students nodded for their grades, but I opened up the umbrella, holding it by what was left of the handle, and it blossomed before the astonished class. Once again, when dismissed, I made magic and I got an A for seeing among the blind. - Rane Ramón Arroyo

1967 – François Ozon is a French film director and screenwriter whose films are usually characterized by sharp satirical wit and a freewheeling view on human sexuality, particularly gay, bi, and lesbian sexuality. Ozon is himself openly gay.

He has achieved international acclaim for his films 8 femmes (2002) and Swimming Pool (2003). Ozon is considered to be one of the most important French film directors in the new “New Wave” in French cinema.

Ozon often features LGBT people in his films. Some examples include:

Une robe d'été: a young gay man strengthens his relationship with his boyfriend through a brief encounter with a woman.

Scènes de lit: this features a lesbian couple and a gay couple.

La petite mort: a gay man's relationship with his estranged father.

Sitcom: this spoof comedy has numerous lesbian and gay references. The family's son comes out, engages in sexual orgies and begins an affair with the maid's husband, a sports teacher. The maid, herself, finds out she's a lesbian and seems to have a relationship with the mother, who has tried to cure her son's homosexuality by sleeping with him - she, of course, fails.

Les amants criminels: the main male character is gay and in the closet; he kills his (male) object of desire out of jealousy and enjoys his relationship with an ogre-like man who's kidnapped him and his female friend who was, more or less, his beard.

Gouttes d'eau sur pierres brûlantes: the two male characters, Léopold and Franz, are lovers - they are either gay or bisexual, while Véra, a former boyfriend of Léopold's, is now an M2F transsexual/trans woman.

8 femmes: one woman is lesbian and two others are bisexuals; the maid is ambiguous towards her female boss all the while she is her male boss's mistress. This film presents a lesbian kiss between Catherine Deneuve and Fanny Ardant. It's a gay cult movie in France.

5x2: a happy gay couple is used to highlight the unhappiness of the heterosexual couple in the film.

Le temps qui reste: this deals with the end of life of a young gay man dying of cancer.

Le Refuge: this film explores the relationship between a homosexual man and the pregnant girlfriend of his deceased brother.

1974 – Todd Klinck, born in Windsor, Ontario, is a Canadian writer, nightclub owner and pornography producer.

Klinck moved to Toronto at age 18 to study theatre at York University, but dropped out to focus on his career. In 1996, his novel Tacones (High Heels) was the winner of the Three-Day Novel Contest, and was published by Anvil Press to strong reviews in the Toronto Star and Quill and Quire.

Klinck also collaborated with John Palmer and Jaie Laplante on the screenplay for the 2004 film Sugar, which garnered a nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay at the 25th Genie Awards, and he was a columnist for fab until 2005. He wrote an online only column for Xtra! called "Sex Play" in 2009, and a column called "Porndoggy" in the same publication for most of 2010. His writing has been published in the National Post, Saturday Night and Bil Bo K (Belgium).

Klinck and his business partner Mandy Goodhandy have launched several sex businesses in the Toronto area, including a transgender strip club, "The Lounge", an adult DVD production company, "Mayhem North", and a porn site, "Amateur Canadian Guys". In 2006 they opened a pansexual nightclub, "Goodhandy's", located in downtown Toronto. Klinck has also worked as a professional BDSM dominant, and has appeared on the television series KinK.

With Goodhandy, Klinck was chosen to be the Grand Marshall of the Pride Toronto 2010 parade.

Ted Nebbeling & Jan Holmberg

2003 – With same-sex marriage recognized by the courts, British Columbia cabinet minister Ted Nebbeling becomes Canada's first serving cabinet minister to legally marry Jan Holmberg, his same-sex partner of 32 years, one of the world's first same-sex weddings of a serving cabinet minister.

The day after his marriage was announced in the media, Nebbeling was dropped from cabinet in a shuffle. The government stated that the timing was coincidental and that there was no prejudicial motive behind this, as Nebbeling was openly gay at the time of his election. Nebbeling and Holmberg are both immigrants to Canada, Nebbeling from the Netherlands and Holmberg from Sweden.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The abuse of Nora Spurgin

By Nora Spurgin “There are many things that happened with the children. During the time when I was an IW (Itinerant Worker), it was Christmas time and we had made arrangements to celebrate the holiday. I was in Denver. Hugh was gong to bring the children and I would meet them in Indiana to visit Hugh’s family. We bought the train tickets, and then I got a call that the IW’s should not go home. It was one of the hardest things for me. I couldn’t believe it was happening. It was the most painful Christmas I ever spent. I was almost alone in a big center. Most of the members went home. I bought the most beautiful white material to make a coat for my daughter. It was going to have light blue lining, and blue buttons. I made this coat on Christmas day.”

“Later we were both sent out to do pioneering. The married women from 777 couples were sent out as IWs. I went out for about three years. On my first IW trip, I went to the Colorado and Texas regions. When I arrived they had just received word that there had been a terrible car accident on the way to a workshop, and several people had been killed. Two members and two guests had been killed, as well as two people in the other car. My first duty was to attend all the funerals and deal with the parents. I had to go to New Mexico where it happened.”

“It was during that time that we left the children. They spent a lot of time at the nursery. Hugh was at the seminary, where the nursery was located. We never knew how long these missions would last. Sometimes I wondered how long I could drag my heavy heart around from state to state, I so longed to be with my family. Then we had to work for Yankee Stadium. We thought that might be the end of the IW mission and that Father would say to go home after Washington Monument. By then many of us were pregnant. I think we all felt like it was time for us to go home. Then Father said, “IWs, stand up.” We all stood up. He said, “Continue.” Our hearts sank, to face the word “continue.”

From page 47 of the book 40 Years in America – An intimate History of the Unification Church 1959-1999

The book was edited by Michael Inglis with historical text by Michael Mickler. Design by Jonathan Gullery. Large format; 602 pages

_______________________________________

Sun Myung Moon caused huge damage to many second gen children. There have been many suicides.

Moon instructed: “Whenever the Blessed couples have children, as soon as the child become 100 days old, they will put him in the nursery school.”

Life Among the Moonies [in Oakland] by Deanna Durham

Infants abandoned by UC parents in the US. Two die at Jacob House, Tarrytown.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kwame Nkrumah arrived in Philadelphia in 1935 to begin undergraduate study at Lincoln University. After completing a bachelor’s degree in Sociology magna cum laude, Lincoln admitted him to its Theological Seminary in 1939 for an additional degree in Sacred Theology. It was at this time, however, that Nkrumah began concurrent enrollment at the University of Pennsylvania in the hopes of acquiring multiple degrees simultaneously. Supporting himself through a precarious combination of scholarships and seasonal work in the segregated shipyards of Philadelphia, Nkrumah regularly visited Harlem and Washington to speak on anti-imperial themes in churches, on street corners, at political rallies, and in classrooms. In so doing, he managed to meet such prominent intellectuals of the African diaspora as C.L.R. James, Nnamdi Azikiwe, and Marcus Garvey. As he later recalled in his autobiography, “Life would have been so much easier if I could have devoted all my time to study. As things were, however, I was always in need of money.”

After receiving his Master’s degree from Penn’s Graduate School of Education in 1941, Nkrumah began another program of study with the Department of Philosophy on a University Scholarship. His advisor Glen Morrow noted that he satisfied the requirements for a Master’s degree in Philosophy in 1943, and by 1944 it appears that he had passed his preliminary exams for a doctorate. He then began working as a Twi instructor for Zelig Harris in a new African Studies graduate group, and in 1945 he left the United States for London and Manchester. He finally returned to the Gold Coast in 1947.

Kwame Nkrumah was the founder of the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party.

Source: https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history/nkrumah

#blacktumblr#black history#black liberation#african history#kwame nkrumah#aaprp#all african people’s revolutionary party

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Parting Gift'

Fandom: Fellow Travelers Characters: Tim Laughlin, Marcus Gaines Pairing: Hawk/Tim Rating: G Words: 1k Summary: Tim asks Marcus to deliver the paperweight to Hawk. A/N: I thought it might be fun to write the moment when Tim asks Marcus to deliver the package as well as diving a bit into Tim's intentions behind it. Hope you like it :)

[you can also read it on AO3]

Tim was sitting on the sofa in his apartment, twirling the small package in his hands.

He had spent the last couple days wondering whether he should return the paperweight to Hawk – or rather when he should return it to him. It belonged to Hawk, after all, so of course Tim would have to give it back to him at one point or another. Yet somehow, now felt too soon. Yet there were many things happening too soon. He did not have the privilege of time anymore.

He wanted for the paperweight to be delivered personally, as he did not want to risk it getting lost. A few days ago, Marcus had mentioned that he was going on a trip to D.C. and told Tim that he might pay a visit to Hawk as well in the process. Tim knew that Marcus did not plan on visiting Hawk, but that it had been a question directed at him – asking him whether he wanted for Marcus to talk to him. But Tim had not replied anything to that. He did not want to see Hawk nor talk to him in any way. After years, he had found some sort of peace, and he hoped that Hawk had done the same. There was no reason to disrupt that peace on either part – not anymore.

At the same time, Marcus visiting Washington presented the perfect opportunity to ensure that Hawk would receive his paperweight. And yet, Tim still felt uncertain.

Hawk had left that paperweight for him as a parting gift. Tim still remembered how surprised he had been when he had woken up, the paperweight lying next to him. A smile had appeared on his face then, believing it a sweet gesture. He should have known better. None of Hawk’s sweet gestures had ever come without an ulterior motive.

Tim should have returned the paperweight to Hawk then – but for some reason, he had kept it instead. It had helped him throughout seminary – a constant reminder that it was better for forget about Hawk. At the same time, perhaps the paperweight was the reason he had never been able to forget.

It had been there when he had returned from prison, and he had kept it with him as he had moved to San Francisco. In some ways, he believed that the paperweight had helped him find peace. It was both, a token of remembrance as well as a warning to never return to Hawk. It represented the person that Hawk was, but also the love that Tim held for him. He was glad that he had kept it.

There was a knock on the door, pulling Tim out of his musings. It was Marcus who entered. Tim had asked him over to hand him the package before he would leave tomorrow. He could not have walked the short distance to his and Frankie’s apartment, as his legs had pained him immensely those past days. Which was also why he remained on the sofa and did not stand up as Marcus entered.

“So, what’s been so urgent that it could not wait until after I return from my trip?” Marcus asked, sitting down on a chair next to the sofa. He had told him over the phone that he would leave tomorrow morning and had not yet finished packing. Of course, it had been Tim’s fault for taking so long to think it all through. But now that he had made the decision, he also needed to follow through with it.

“Are you still planning on paying Hawk a visit?” Tim asked.

“Why are you asking?”

Tim looked down on the package in his hands. There was still a slight feeling of hesitation, but he knew that now was the right time – or maybe, it was the only time.

“Would you mind giving this to him?” he asked, reaching out his arm to hand him the package.

Marcus looked at the package, not yet taking it. Instead, he eyed Tim curiously. “What’s in there?”

“Just some old paperweight that belonged to him,” Tim replied as casually as possible. “You know, I’m sorting out some stuff – making sure everything’s settled. And I want this to be returned to him.”

Marcus still hesitated while Tim continued reaching out the package to him. His arm began to shake and carefully, Marcus took the package from him, asking, “Why now?”

“Why not now?” Tim asked in return.

Marcus frowned slightly at that. Instead of answering his question, he said, “Have you heard from him at all?”

“No,” Tim replied plainly.

“So … this is not meant as a way to … maybe get his attention?”

Marcus gave him a knowing look, but Tim simply shook his head. “It’s only convenient. You’re already going over there, so you might as well take this with you,” he told him. “I doubt he wants to talk to me, and neither do I want him to. If he makes any suggestion like that, you can make it clear that I don’t want to hear from him.”

Marcus looked at him silently for a moment. Then, he nodded as he stood up, promising him to deliver the package and message.

After Marcus had left, Tim remained on the sofa, silently staring at the closed door for a moment. For almost three decades, the paperweight had been part of his life – almost as long as he had known Hawk. Some part of him already regretted letting go of it. But in the end, it did not belong to him.

Marcus was probably not wrong in his assumption that it was meant as a way to receive Hawk’s attention. Yet Tim also knew that he did not want Hawk’s attention. Maybe, he was simply curious. He did not know how Hawk might react – whether he would accept it silently or call or even come by for a visit. Neither did Tim know what he wanted him to do. In the end, it did not matter. He had no expectations.

#fellow travelers#fanfiction#tim laughlin#marcus gaines#hawk x tim#one of the many ft oneshots that's been collecting dust in my drafts#but i'm working on way too many fics currently and just can't find the time to edit them#but this one was pretty straightforward and didn't need too much editing so i thought i might share it

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is what entryist subversion looks like. This is what Militant did to Labour in Liverpool and what the DSA has done to Democrats in Astoria, Queens: a hostile takeover from within.

Moishe House is an explicitly Zionist organization. Why would an anti-Zionist rabbi want to work for them except to promote ideologies contrary to the organization’s mission? Moishe House’s handbook rules were well written to prevent such expected eventualities, and in violating them, Rabbi Kleinman is the author of her own termination - not for criticism of the war, but for her opposition to the existence of the country that is home to half the world’s Jews.

Why, you might ask, would someone who desires such harm to befall half the total population of Jews would want to become a rabbi in the first place? Wouldn’t a Jewish cleric have a pastoral responsibility to all k’lal Yisrael, not just those privileged enough to live in countries from which they’d not had to flee?

This is what happens when one’s calling is narrow, doctrinaire, and uncompromising social causes, rather than the full duties of the role one seeks to inhabit. Kleinman could have been an activist anywhere. She did not have to kasher views that put Jews in danger with seminary training. But her calling was not faith nor ritual nor scripture nor care: it was a desire to shrink something far greater than herself - Judaism - into something no larger than the size of her own ego.

I’ve written about how instruction is incompatible with activism. The educator must teach students how to think, must maintain multiple perspectives simultaneously, must think broadly, cautiously, and charitably. The activist must push their ideals with a single-minded sense of purpose, must be apologist and polemist, must seek favorable ends for their side rather than stay analytically aloof and detached from the fray. The activist avoids asking themselves difficult, challenging questions about their own mission and worldview. Consider then that “rabbi” means ‘teacher’ in Hebrew. Kleinman has placed herself in multiple professional and confessional conflicts of interest. The Washington Post should have considered this before running her side of the story so uncritically.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The educational opportunities for African-Americans were so severely limited in the pre-Civil War period that the issue of separate education for girls did not arise. Black boys and girls generally shared whatever inadequate educational facilities were available. Still, there were a few black women teachers in the early national period who founded and maintained schools for black children. In 1820, fifteen-year-old Maria Becraft opened the first boarding school for black girls in Washington, D.C. Two decades later the Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia became the training ground for a core of women teachers who significantly affected the development of black schools and whose training could match that of graduates of white female seminaries. Fannie Jackson Coppin (1837-1913), a former slave who in 1860 graduated from Oberlin College, headed the Institute's Female Department from 1869 on for over three decades. Like the other great teachers and founders of educational institutions who followed in her footsteps, her educational goal was first and foremost the elevation of her race and of its mothers. In an adaptation of the ideology of Republican Motherhood the African-American pioneer educators developed an ideology which exalted black mothers as the emancipators of the race.

In one of the greatest social experiments in history, nearly a quarter-million black children, kept illiterate under slavery, were instructed in over 4300 schools within five years of the end of the Civil War. Some 45 percent of the teachers of the freedmen were women, many of them African-American. The movement of which they were a part laid the foundation for the establishment of public schools in the South.

The great black educator Anna Julia Cooper, writing the first full-blown feminist argument in America made by an African-American woman, appealed to black men to “give the girls a chance. . . . Teach them that there is a race with special needs that they and only they can help; that the world needs and is already asking for their trained, efficient forces." And she described with great foresight the result of men's hegemony over ideas, concepts and theories:

So long as woman sat with bandaged eyes and manacled hands, fast bound in the clamps of ignorance and inaction, the world of thought moved in its orbit like the revolutions of the moon; with one face (the man's face) always out, so that the spectator could not distinguish whether it was a disc or a sphere. . . . I claim . . . that there is a feminine as well as a masculine side to truth; and that these are related not as inferior and superior, not as better or worse, not as weaker or stronger, but as complements—complements in one necessary and symmetric whole.

With the beginning of the organized movement for woman's rights, male dominance over definitions and mental constructs was under continuous challenge. It would take another hundred years in the United States before women would gain equal access to all institutions of higher learning, but the trend and the outcome were inevitable. The world of thought would no longer reflect only the man's face. The other half of the human race had, after two millennia of struggle, found its voice and established its claims. At long last, a truly human edifice of human thought could and would be built, combining the male and the female vision and irrevocably altering our view of wholeness. Hereafter we, women and men, would know whether the moon is a disc or a sphere.

-Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Feminist Consciousness

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

It Happened Today in Christian History

June 1, 1909: Rosa Jinsey Young, the valedictorian of Payne University, Selma, Alabama delivered a speech titled “Serve the People.” The nineteen-year-old sat to give her speech because she had worked so hard her body had broken under the strain. She said nothing of her suffering, however, and spoke a message of selflessness instead:

“Every vocation in life implies service. Those who are aspiring for high positions should seek to become the servants of all... The talent we possess is for the service of all. The truth we hold is the truth of all mankind... ‘He that is greatest among you shall be your servant,’ is the language of the Great Teacher. To serve is regarded as a divine privilege as well as a duty by every right-minded man... As we go from these university halls into the battle of life, where our work is to be done and our places among men to be decided, we should go in the spirit of service, with a determination to do all in our power to uplift humanity... It makes no difference how circumscribed opportunities may be, show yourself a friend to those who feel themselves friendless.”

Idealistic as her words may have been, Rosa Young turned them into reality.

Born in Rosebud, Alabama, she was the daughter of a black Methodist circuit rider, and was determined to use her education to better the lot of African-Americans. After several years teaching in Alabama towns, she yearned to open her own school. Believing that this good desire was from God, she stepped forth in faith and opened a private school near home for seven students.

In three terms, the school had grown to 215 students. However, the students’ families were poor and could pay little toward expenses. The cotton crop had fared poorly because of boll weevils and she had no money to keep the school open. After paying her sister, whom she had hired to help her, she only had a few cents left. She turned to her church, to well-to-do whites, and to anyone who might be able to help. Although she received small contributions, it was not enough.

Young went home and prayed. Then it occurred to her to write to the black educator Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee Institute. Washington replied that he was unable to help, but advised her to contact the Board of Colored Missions of the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod (LCMS). According to Washington, Lutherans were doing more for African-Americans than any other denomination.

The LCMS sent pastor Nils Bakke to investigate. When he found she was telling the truth, he arranged for help. Young joined the Lutheran church and with its aid founded thirty rural schools, a high school, and a teacher training college, on whose faculty she served. She also planted Lutheran churches. Although derided for leaving the Methodists, she defended herself: “I was born and reared in gross darkness, wholly ignorant of the true meaning of the saving Gospel contained in the Holy Bible...I did not know that I could not read the Bible and pray enough to win heaven.”

Young worked tirelessly almost to the end of her 81 years, even mortgaging her own property to keep the work alive. In 1961, Concordia Theological Seminary in Springfield, Illinois awarded her an honorary Doctor of Letters degree. Ten years later, in 1971, she died, having contributed to the education of thousands of students while spreading the Gospel in Alabama. She titled her autobiography Light in the Dark Belt.

#It Happened Today in Christian History#June 1#Rosa Jinsey Young#valedictorian speech#Payne University

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"David Dellinger and his friend Don Benedict caught a ride from New York to Washington, D.C., for the Lincoln’s Birthday weekend of 1940. Who knows where they stayed—on somebody’s floor, probably. It was the Depression, and Dellinger in particular knew all about roughing it. Benedict was hoping to learn from him on that score. They were in Washington because the two of them were part of a youth movement whose eager vanguard had descended on the city to agitate for jobs, rights, peace, and what they saw as justice. Both had backgrounds in the important Christian student movement of the era, Dellinger at Yale and Benedict at Albion, a little Methodist college in Michigan, and both now were graduate students at Union Theological Seminary in New York. There Dellinger had quickly formed a close bond with Benedict and Meredith Dallas, also from Albion. Pacifism, like socialism, was in the air at Union, at least among students.

Members of the American Youth Congress parade in gas masks on Fifth Avenue in New York City February 6, 1940 protesting impending war and publicizing the upcoming youth pilgrimage to Washington, D.C. Acme News Service. Washington Spark Flickr.

It was an exciting time, even if, like W. H. Auden, America’s young, having lived through “a low dishonest decade,” could feel the

Waves of anger and fear Circulate over the bright And darkened lands of the earth, Obsessing our private lives[.]

The students who made their way to Washington that weekend had come of age in the Great Depression. America’s collegians, once apathetic, were now far more conscious of injustice, chafing under the political constraints imposed by paternalistic faculty and administrators—and determined to stay out of war. “It was a time when frats, like the football team, were losing their glamor,” wrote the playwright Arthur Miller, recalling his days at the University of Michigan (Class of 1938):

Instead my generation thirsted for another kind of action, and we took great pleasure in the sit-down strikes that burst loose in Flint and Detroit…We saw a new world coming every third morning.

Many such Americans worried that war would undo whatever progress had been made by the New Deal, while undermining civil liberties. Stuart Chase, a popular economics writer and FDR associate whose 1932 book, A New Deal, provided ideas and a name for the White House program, argued that by avoiding war we might achieve

the abolition of poverty, unprecedented improvements in health and energy, a towering renaissance in the arts, an architecture and an engineering to challenge the gods.

But if war were to come, he wrote, we would see

the liquidation of political democracy, of Congress, the Supreme Court, private enterprise, the banks, free press and free speech; the persecution of German-Americans and Italian-Americans, witch hunts, forced labor, fixed prices, rationing, astronomical debts, and the rest.

Delegates to the American Youth Congress march from the U.S. Capitol to the White House Feb 9, 1940 where they were addressed by President Franklin Roosevelt. International News Photo, Washington Area Spark Flickr.

If Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal didn’t go far enough, it had at least offered hope. But in foreign affairs even this scant comfort was absent. During the thirties students had seen the rise of Hitler, the fascist triumph in the Spanish Civil War, and a series of futile appeasement measures culminating in the Nazi invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, which triggered war with Britain and France. As Dellinger, Benedict, and thousands like them arrived in Washington, tiny Finland was still fighting with unexpected ferocity to repel an invasion by the Soviet Union, which had cynically agreed with Germany to divide Europe between them. The Red Army even joined in the dismembering of Poland. On the other side of the world, China had been struggling since 1937 against a brutal Japanese invasion.

Hope springs eternal, but on the morning of Saturday, February 10, 1940, even the nasty weather augured ill. Washington was rainy and cold as a young woman on horseback—dressed as Joan of Arc—led a procession of idealistic young Americans along Constitution Avenue. Many were in fanciful costumes. The rich array included some in chain mail and others dressed as Puritans. A delegation from Kentucky rode mules. Signs and banners held aloft by the students that weekend bore antiwar slogans, including, loans for farms, not arms; jobs not guns; and, in sardonic reference to the discredited crusade of the Great War, the yanks are not coming.

The context of their march was the national struggle over what role America should play in the European war—a war that had happened despite the best efforts of well-meaning people the world over to avoid it by means of rhetoric, law, arms control, appeasement, and every other method short of actually fighting about it. Now that it was at hand, America’s young were far more opposed to intervention than their elders, and this was a source of conflict on campus. At Harvard’s graduation a few months later, class orator Tudor Gardiner reflected the attitudes of many students in calling aid for the Allies “fantastic nonsense” and urging a focus on “making this hemisphere impregnable.” When Gardiner’s predecessor by twenty-five years recalled, at a reunion event, that “We were not too proud to fight then and we are not too proud to fight now,” recent graduates booed. But when commencement speaker Cordell Hull, FDR’s secretary of state, called isolationism “dangerous folly,” Harvard president James Bryant Conant nodded in support. Scenes like this would play out at campuses all across the country.

Delegates to the American Youth Congress with the U.S. Capitol in the background Feb 9, 1940 call for more jobs not war. The image is an undated Harris & Ewing photograph from the Library of Congress.

The students who converged on Washington for the Lincoln’s Birthday weekend brought with them their generation’s disdain for war. Marching in a steady drizzle, they were bound, these tender youths, for the White House, to which they had foolishly been invited by Eleanor Roosevelt—herself an active pacifist during the interwar years. “Almost six thousand young people marched,” her biographer reports, “farmers and sharecroppers, workers and musicians, from high schools and colleges, black and white, Indians and Latinos, Christians and Jews, atheists and agnostics, freethinkers and dreamers, liberals and Communists.”

Dellinger and Benedict were part of this “extraordinary patchwork,” the two seminarians having made the trip from New York by car with some other young people. Dellinger in particular was already being noticed, as he always seemed to be. Years later he would recall (clearly as part of this weekend) being invited by the First Lady to a White House tea in early 1940 with other student leaders who had, as he put it, organized a protest that she supported. Benedict’s memoir recalls that the two of them went to Washington that same month and attended “a huge rally, with thousands massed around the White House” to hear remarks by the president and the First Lady. “Dave and I talked a lot about demonstrating,” Benedict writes, adding: “Both of us knew the value of drama.”

...

For the White House, it made sense to pay attention to the young, many of whom would be just old enough to vote in the upcoming presidential election. Before the Depression, college students were solidly Republican, but as the thirties wore on and their social consciousness expanded, they swung increasingly to Roosevelt’s Democrats. The AYC [American Youth Congress] was both a cause and effect of this change and enjoyed the warm support of Eleanor Roosevelt, who over the several years of its existence had raised money for it, defended it in her newspaper columns, procured access to important public figures, and even scheduled face time with the president. For the big weekend event she had gone all out, prevailing on officials, hostesses, and her husband to accommodate the anticipated five thousand young people in every possible way. An army colonel named George S. Patton housed a bunch of the boys in a riding facility the First Lady had recently visited. She lined up buses; helped with costumes and flags, meals and teas; and arranged at least one of the latter at the White House—consistent with Dellinger’s recollection.

The event in Washington was billed as “a monster lobby for jobs, peace, civil liberties, education and health,” but it turned out to be the Götterdämmerung for the youth congress, and a landmark in the decline of America’s vigorous interwar peace movement. Nothing could more effectively symbolize the movement’s tender idealism, fair-weather pacifism, and ecclesiastical aura than an American college student dressed as the Maid of Orleans—a sainted military hero—on horseback, just months before France itself fell to an onslaught of modern mechanized warfare. Of course the American Joan of Arc, whoever she was, can be read as a symbol of hope for France because, in fact, the Yanks were coming, even if most of them didn’t know it yet. On the other hand, hopes for peace were starting to look more like delusions, even to those who held them, and here the symbolism becomes even richer, for Joan embodies three powerful drivers of the era’s American peace movement: She is young, she is female, and she is religious.

A few of the 3,000 youth that arrived for the opening of the three day American Youth Congress February 9, 1940 that will lobby Congress for passage of a youth bill to provide education and jobs. Washington Area Spark Flickr.

Many of these activists regarded abolitionism as the forerunner of their reformist enterprise, so it was fitting that here they were, in 1940, rallying for righteous change on the weekend of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. By now the students have reached the White House, arriving an hour early to hear the president. They had to leave their banners and placards outside the gates, where the guards on duty counted 4,466 gaining admission to the South Lawn—no doubt including Dellinger and Benedict. They grew colder and wetter as they waited.

After a while the American Youth Congress’s national chairman, Jack McMichael, a southern divinity student who had earlier spoken out against the violent abuse and disenfranchisement of blacks, took the microphone on the South Portico and led the students in singing “America the Beautiful.” And then, at long last, he introduced the president, describing our troubled country as a place where Americans dream of “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” but face the threat of bloodshed.

Now war, which brings nothing but death and degradation to youth and profit and power to a few, reaches out for us. Are we to solve our youth problem by dressing it in uniform and shooting it full of holes? America should welcome and should not fear a young generation aware of its own problems, active in advancing the interests of the entire nation…They are here to discuss their problems and to tell you, Mr. President, and the Congress, their needs and desires…I am happy to present to you, Mr. President, these American youth.

When FDR finally appeared, looking out with Eleanor over a sodden crowd dotted with umbrellas, he wore a strange smile—and gave them a blistering earful, dismissing as “unadulterated twaddle” their concerns about Finland and warning them against meddling in subjects “which you have not thought through and on which you cannot possibly have complete knowledge.” Concerning their cherished Soviet Union, FDR said that in whatever hopes the Soviet “experiment” had begun, today it was “a dictatorship as absolute as any other dictatorship in the world.” It was a shocking public rebuke to the students as well as the First Lady. The young compounded the fiasco by booing and hissing, creating a public relations nightmare in a nation that took a dim view of such a response to the president. Later that afternoon the First Lady had to sit still at an Institute plenary session, calming herself by knitting, while the fiery antiinterventionist John L. Lewis pandered to his student audience by heaping abuse on FDR. He would support Willkie in the coming election.

Besides Dellinger, other future activists who stood in the rain for Roosevelt’s “spanking,” as some newspapers called it, included future Representative Bella Abzug of New York and the writer Joseph Lash, who would win the Pulitzer Prize for his biography of Eleanor Roosevelt and help found with her (and Niebuhr) the liberal but anti-communist Americans for Democratic Action. Woody Guthrie was on hand, too, to write the student movement’s requiem. The folk singer, not yet a celebrity, arrived by riding the rails from Texas. Stunned by the president’s public scolding of the idealistic youngsters, Guthrie wrote a song on the spot entitled, “Why Do You Stand There in the Rain?”

It was raining mighty hard in that old Capitol yard When the young folks gathered at the White House gate. … While they butcher and they kill, Uncle Sam foots the bill With his own dear children standing in the rain.

Without money, Dellinger and Benedict made like Guthrie by riding the rails to get home—a first for Benedict but something Dellinger had been doing on and off for several years. After the excitement of the weekend they entered the railyard in darkness, careful to elude watchmen, and hunted for a train heading north. When they found one, they couldn’t gain access to any of the boxcars, but finally climbed aboard an open coal car, the freezing wind whipping them as they picked up speed, the air thick with choking dust and smoke. Miserable as it was, they were moving too fast to get off. It was an omen, perhaps, of the nature of their journey to come.

- Daniel Akst, War By Other Means: How the Pacifists of World War 2 Changed America for Good. New York: Melville House, 2022. p. 4-6, 7-8, 17-19.

#washington dc#peace march#youth rally#white house#fdr#american youth congress#youth movement#pacifism#world war ii#united states history#the great depression#new deal#research quote#reading 2024

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Eye for an Eye

The following is a post from a UCC colleague and friend in Ann Arbor, Michigan (here's her church). Thank , Pastor Deb and Church of the Good Shepherd, for your loving presence in the world.

Dear friends-

When I started seminary at Pacific School of Religion in 1995, I took a class called The Bible and the Near East from a visiting Israeli scholar (Dr. Shalom Paul). He approached the Hebrew Bible from a comparative literature perspective, and we read other ancient writings from other religions/ethnic groups from around the same time. It was an interesting approach for sure.

One lesson that has stuck with me was about “an eye for an eye” that is found in Leviticus:

19 If someone injures a fellow citizen, they will suffer the same injury they inflicted: 20 broken bone for broken bone, an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. The same injury the person inflicted on the other will be inflicted on them. (Lev. 24:19-21, Common English Bible).

We have all heard this saying even if we weren’t clear about where the saying came from. You also might remember the famous Gandhi quote “an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.” I have seen that on numerous bumper stickers over the years. Dr. Paul spent an entire class session talking about what this verse has meant to our Jewish siblings over the millennia as well as how this law was quite unusual in its ancient context.

According to our Israeli professor, an eye for an eye is not about revenge as one might guess. An eye for an eye was about setting limits to revenge. In an ancient context where “justice” was meted out in radically disproportionate ways (i.e. someone stole a piece a fruit and they would lose their whole arm), an eye for an eye was commanding that punishment fit the crime. It was about a proportionate response to whatever crime or misdeed had happened. While I do not believe in capital punishment, an eye for an eye regarding killing a human limited the response to only executing the person responsible for the death. Many other laws in that historical context would call to execute the whole family, or destroy the whole village. Even if it can feel brutal in our context, an eye for an eye was about limiting the retribution, and that was a radical thing in the ancient near east.

Now, I cannot say with confidence that this interpretation is indeed the dominant interpretation in most Jewish contexts. As we know, Biblical interpretation can vastly differ from community to community. But I have carried that lesson with me for almost 30 years and I have been thinking about this so much in the last 10 days…the devastation in Israel/Palestine brings this question up for me in profound ways.

I have heard many people say, “This conflict is so complicated.” I have said it in the past as well. But it is becoming clearer and clearer to me that it is not that complicated. The Israeli response to the Hamas massacre is beyond an eye for an eye. It is beyond a proportionate response. It is beyond “defending” itself. The government of Israel has dropped 6000 bombs on Gaza in 10 days. For context, the US dropped 6000 bombs in a year during an active war in Afghanistan. 6000 bombs have been dropped on 2.2 million people living in an area the size of Las Vegas, but with 3 times the population. Gaza City is more densely populated that New York City. And unlike any other city in the world, there is nowhere to flee. Nowhere.

Yesterday in Washington DC, hundreds of people, mostly American Jews, protested in the capital. These protesters were lamenting the loss of innocent lives in Israel and those who remain in Hamas custody. But all of them were calling for a ceasefire. One protestor said, “Killing Palestinian babies won’t bring back the murdered babies of Israel.” Israel cannot kill its way out of this conflict, but the right-wing Zionist government of Israel is showing no signs of mercy.

I have no idea how we get beyond this terrible place. But I do know that a genocide of indigenous people in Gaza and in the West Bank is not the answer. An Apartheid state for Palestinians is not the answer. Western colonial expansion is not the answer. The answer must be rooted in human dignity and agency…or we will never find our way out of this mess.

Not in our name. That is what the protestors said yesterday. Not in our name.

In love and solidarity, Deb

#Israel#Palestine#Gaza#West Bank#war#conflict#Zionist#eye for an eye#Hebrew#bible#UCC#Hamas#Israel Hamas war

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today In History Alfred L. Cralle was a Black businessman and inventor, who invented the ice cream scooper, patent #576,395 on this date February 2, 1897. Alfred L. Cralle was born in Kenbridge, Lunenburg County, Virginia just after the end of the American Civil War. He attended local schools and worked with his father in the carpentry trade as a young man, becoming interested in mechanics. Cralle went to Washington, D.C., and attended Wayland Seminary, one of several schools founded by the American Baptist Home Mission Society to help educate Blacks after the American Civil War. He settled in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he first served as a drug store and hotel porter. Alfred noticed that servers at the hotel had trouble with ice cream sticking to serving spoons, and he developed an ice cream scoop. The patented "Ice Cream Mold and Disher" was an ice cream scoop with a built-in scraper to allow for one-handed operation. Cralle's functional design is in modern ice cream scoops. He later became a general manager for the Afro-American Financial, Accumulating, Merchandise, and Business Association. CARTER™️ Magazine carter-mag.com #wherehistoryandhiphopmeet #historyandhiphop365 #cartermagazine #carter #staywoke #alfredcralle #blackhistorymonth #blackhistory https://www.instagram.com/p/CoKOIYorJK8/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#576#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#historyandhiphop365#cartermagazine#carter#staywoke#alfredcralle#blackhistorymonth#blackhistory

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

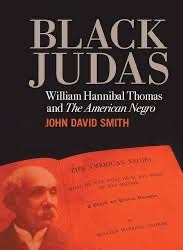

Sergeant William Hannibal Thomas (May 4, 1843 - November 15, 1935) was born in Pickaway County, Ohio to free parents. He performed manual labor and broke the color line by entering Otterbein University in 1859. His matriculation at the school sparked a race riot and he withdrew. Denied entry to the Union Army in 1861 because of his race, he served as principal of Union Seminary Institute.

After twenty-two months’ service as a servant in two white Union regiments, in 1863 he enlisted in Ohio’s first all-Black military unit, the 127th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Appointed sergeant, he became a decorated combat soldier. He received a gunshot wound in the right arm that resulted in its amputation. He suffered pain and medical complications from this wound for the remainder of his life.

He resided in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Georgia, South Carolina, and Massachusetts. After attending divinity school, he worked as a journalist, teacher, theologian, lawyer, militia officer, trial justice, and elected official. The State Department appointed him consul to Portuguese Southwest Africa. He faced allegations of financial and moral improprieties from church, state, and local officials. He launched the short-lived magazine The Negro. He published Land and Education, a monograph that urged Blacks to reform themselves through prayer, improved moral values, education, and land acquisition.

He is known for The American Negro, a book that censured Blacks, especially women, and clergymen, as immoral, irresponsible, and destined to fail. He differentiated between mulattoes like himself, whom he considered superior, and Negroes, whom he judged to be hopelessly depraved. Few contemporary white critics denounced African Americans with as much crude rhetoric as he employed in The American Negro.

His book catapulted him onto the national stage. White supremacists cited The American Negro as justification for the repeal of the Fifteenth Amendment. African Americans, including Charles W. Chesnutt, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Booker T. Washington, were charged with hypocrisy and sought to suppress his book. They dubbed him “Black Judas. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A greater share of young adults say they believe in a higher power or God.

About one-third of 18-to-25-year-olds say they believe—more than doubt—the existence of a higher power, up from about one-quarter in 2021, according to a recent survey of young adults. The findings, based on December polling, are part of an annual report on the state of religion and youth from the Springtide Research Institute, a nonpartisan nonprofit.

Young adults, theologians and church leaders attribute the increase in part to the need for people to believe in something beyond themselves after three years of loss.

For many young people, the pandemic was the first crisis they faced. It affected everyone to some degree, from the loss of family and friends to uncertainty about jobs and daily life. In many ways, it aged young Americans and they are now turning to the same comfort previous generations have turned to during tragedies for healing and comfort.

Believing in God “gives you a reason for living and some hope,” says Becca Bell, an 18-year-old college student from Peosta, Iowa.

Ms. Bell, like many in her age group, doesn’t attend Mass regularly as she did as a child because of studies and work. But she explores her faith by following certain people on social media, including one young woman who talks openly about her own life and belief, which Ms. Bell, who was raised Catholic, says she finds more meaningful and relevant.

The Springtide survey uses the term “higher power,” which can include God but isn’t limited to a Christian concept or specific religion, to capture the spectrum of believers. Many young adults say they don’t necessarily believe in a God depicted in images they remember from childhood or described in biblical passages, but do believe there is a higher benevolent deity.

Other polls, including Gallup, ask specifically about believing in God and show a decline in young adults who believe in God.

The Rev. Darryl Roberts, pastor of the Nineteenth Street Baptist Church in Washington, D.C., says the pandemic, racial unrest, fears of job loss and other economic worries, stripped away the protective layers that many young people felt surrounded them. No longer feeling invincible, he says, some are turning to God for protection.

“We are seeing an openness to transcendence among young people that we haven’t seen for some time,” says Abigail Visco Rusert, associate dean at Princeton Theological Seminary and an ordained pastor in the Presbyterian Church.

At the same time many young adults say they feel disconnected from organized religion over issues like racial justice, gender equity and immigration rights. And belief in God or a higher power doesn’t necessarily translate into church attendance or religious affiliation.

A Wall Street Journal-NORC poll published last month found that 31% of younger Americans, ages 18 to 29, said religion was very important to them, which was the lowest percentage of all adult age groups. A Pew Research Center study also released last month found that 20% of 18-to-29-year-olds attend religious services monthly or more, down from 24% in 2019.

Desmond Adel, 27, describes himself as an “agnostic theist,” which is someone who believes in one or more deities but doesn’t know for sure if they exist. He attended church every Sunday as a child, but doesn’t recall “which subset of Christianity” it represented, and quit going as a teen. He says he’s not 100% convinced there is a higher power, but “leans towards” the existence of one that isn’t tied to one denomination.

“I don’t think it’s like any Gods described by major religions,” says Mr. Adel, of Carmel, Ind.

Nicole Guzik, a rabbi at Sinai Temple in Los Angeles, says she’s observed more young adults coming to Friday night services at the synagogue as well as monthly events that might include hikes and yoga in the park.

“I think this demographic has a need to connect socially and spiritually,” she says.

Christian Camacho, 24, was raised in a conservative Catholic household and says he has had doubts about God when his parents were going through a divorce and when he was dealing with depression. “How could God allow something like this to happen?” he would ask.

Over the years, his image and perception of God has changed, from a judgmental punitive God of his childhood to a more accepting one. He thinks this belief is common among his generation, who don’t associate God with a specific organized religion.

“A lot of people are turned off by the institutions,” says Mr. Camacho, who lives in Minneapolis and is studying to join a religious order.

Courtney Farthing, 26, who works as a customer-service representative for a call center, attended Baptist and Pentecostal churches growing up and identifies as Christian. Ms. Farthing, who lives in Richmond, Ky., believes in God but says she questioned that belief as a teen.

Now, she says, she chooses to believe.

“If I ever started to doubt, or believe there wasn’t a God, it would send me into a spiral of ‘What ifs,’ things that I would rather not get into.”

Alora Nevers, a 29-year-old stay at home mom of four in Sidney, Mont., has always believed in God. She no longer goes to her Catholic church, where, she says, they talked too much about making donations.

“I would rather praise God the way I do with my family. We pray every night.”

15 notes

·

View notes