#Vsevolod Pudovkin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#polls#movies#storm over asia#storm over asia 1928#storm over asia movie#20s movies#vsevolod pudovkin#valéry inkijinoff#i. dedintsev#aleksandr chistyakov#anel sudakevich#boris barnet#have you seen this movie poll

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

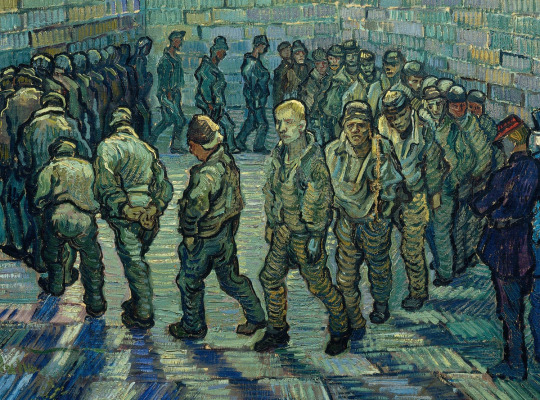

Art Influences Film - Side by Side

Prisoners Exercising - Vincent Van Gogh - 1890

Mother (1926) Vsevolod Pudovkin

A Clockwork Orange (1971) Stanley Kubrick

#a clockwork orange#stanley kubrick#mother#vsevolod pudovkin#prisoners exercising#vincent van gogh#art influences film#side by side#comparison#cinematic parallel#art#film

346 notes

·

View notes

Text

#gif#gifmovie#film#movie#vintage#black and white#landscape#nature#calm#peaceful#Mother#1920s#20s#soviet cinema#Vsevolod Pudovkin#Nathan Zarkhi#maxim gorky

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

four late stalinist films, four red tinted cuts between scenes; a cinema industry drenched in blood

(1) Boris Barnet, {1950} Щедрое лето (Bountiful Summer) (2) Vladimir Petrov, {1951} Спортивная честь (Sporting Honour) (3) Nikolay Lebedev, {1952} Навстречу жизни (The Encounter of a Lifetime) (4) Vsevolod Pudovkin, {1953} Возвращение Василия Бортникова (The Return of Vasili Bortnikov)

#film#boris barnet#vladimir petrov#nikolay lebedev#vsevolod pudovkin#Щедрое лето#Спортивная честь#Навстречу жизни#Возвращение Василия Бортникова#bountiful summer#sporting honour#the encounter of a lifetime#the return of vasili bortnikov#1950#1951#1952#1953#red#late stalinist cinema#stalinist cinema#soviet cinema#soviet union#cccp#colour#1950s#feature length#male filmmakers

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924)

#the extraordinary adventures of mr. west in the land of the bolsheviks#lev kuleshow#porfiri podobed#Boris barnet#Alexandra khokhhlova#vsevolod pudovkin#silent film#talks

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vsevolod Pudovkin, February 16, 1893 – June 30, 1953.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Valéry Inkijinoff in Storm Over Asia (Vsevolod Pudovkin, 1928)

Cast: Valéry Inkijinoff, I. Didintseff, Aleksandr Chistyakov, Victor Tsoppi, Fyodor Ivanov, V. Pro, Boris Barnet, Karl Gurniak, I. Inkizhinov, V. Belinskaya, Anel Sudakevich. Screenplay: Osip Brik, Ivan Novokshenov. Cinematography: Anatoli Golovnya. Art direction: M. Aronson, Sergei Kozlovsky.

The great silent Russian propaganda films depended heavily on two things the nascent Soviet Union had in abundance: faces and landscapes. This reliance on closeups and sweeping views of fields and plains sometimes resulted in a loss of narrative coherence, but put the emphasis on the people and resources that the Bolsheviks needed to exercise control over. Storm Over Asia is no exception, beginning with the windswept land and Asiatic faces of the Mongol peoples of eastern Russia, which at the time depicted in the film was still a vast battleground for the Bolsheviks and European forces. After establishing the location, the film focuses on Bair (Valéry Inkijinoff), a young hunter whose father sends him off to the bazaar to sell a silver fox pelt. In the vividly filmed bazaar, Bair is cheated by an unscrupulous European fur trader (Viktor Tsoppi), who might as well be wearing a label: bourgeois capitalist. Beaten by the henchmen for the trader, Bair escapes and joins a group of Soviet partisans fighting the occupiers. The occupation forces seem to be British, who were never a significant presence in this part of the Soviet Union, but the film is vague about such details. They manage to capture Bair, who is sent out with a soldier to be shot, but when they examine Bair's belongings they discover an ancient document indicating that he's a direct descendant of Genghis Khan. (The original title of the film, in Russian, was The Heir to Genghis Khan.) They find the wounded Bair, restore him to health, and set him up as the puppet ruler of a Mongolian state. In the end, Bair turns against the imperialists and the film concludes with a literal storm sweeping them away. It's a film full of great set-pieces, including a montage mockng the imperialists and their wives as they put on their finery and then are driven on a muddy road to meet the new Grand Lama. After an elaborate ceremony (actually filmed at a Tibetan Buddhist celebration) the lama turns out to be a small boy, not at all impressed with his visitors.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Potomok Chingis-Khana, Vsevolod Pudovkin, 1928

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Slapstick 2025: for the love of silent comedy

It’s supposed to be big mystery: what do women want from a romantic partner? But there is no mystery at all. GSOH every time. That’s good sense of humour, of course. So if you’re in anyway romantically inclined, you’ll already be asking yourself: what is the FUNNIEST way I can celebrate Valentine’s Day next year. Not to brag, but I do have the solution. Bristol’s Slapstick Festival runs 12-16…

#Boris Barnet#Bristol#featured#John Sweeney#Lucy Porter#Paul McGann#silent film#Slapstick comedy#Slapstick Festival#Soviet cinema#Vsevolod Pudovkin

1 note

·

View note

Text

hybride räume - filmwelten im hollywood-kino der jahrtausendwende, oliver schmidt, schüren verlag marburg 2014 (excerpt)

#hybride räume#filmwelten im hollywood-kino der jahrtausendwende#oliver schmidt#schüren verlag#marburg#2014#the empty space#peter brook#vsevolod pudovkin#mystery#90's#beeing#identity#persona#space#hyperspace#cyberspace#new hollywood#new new hollywood#lost highway#the cell#the matrix#the eternal sunshine of the spotless mind#groundhog day#the lawnmower man#beeing john malkovich#ames room#the tenant#ein mann geht durch die wand#i'm not there

1 note

·

View note

Text

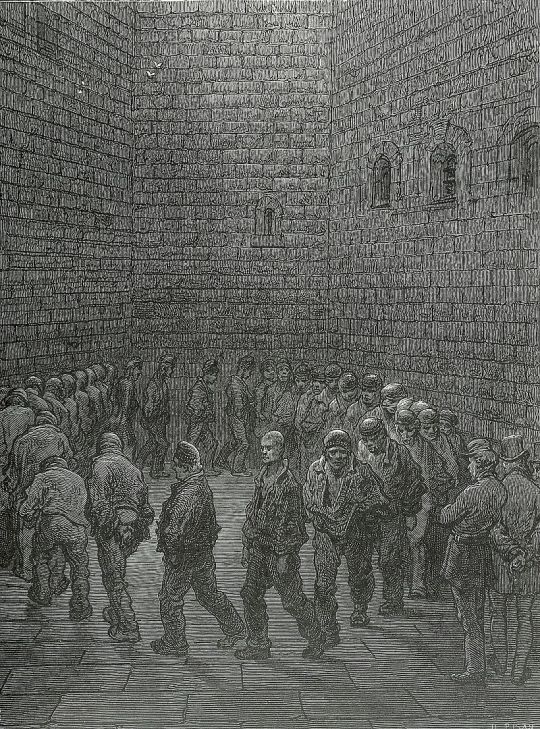

Exercise yard, 1872 — Мать, 1926

#parallels#gustav dore#1872#Prisoners' Round#mat#Мать#1926#silent film#mother 1926#Vsevolod Pudovkin#Pudovkin#Maxim Gorky#Gorky

0 notes

Quote

From Georges Sadoul Paris, 10 December 1951 My dear Luis, I’ve been wanting to reply for six months now to your letter, as I was considerably moved by it. But at Easter, after finishing my tome of a book, I had an attack of lumbago and, after I recovered from that, an extreme case of fatigue lasted well into the summer. The truth is that I have been dragging myself around for six months now and am only a little improved after my return in November. I had an enormous backlog of work when I arrived back in Paris, where I had practically not set foot since April. You will know that your film was a monstrous success in Cannes. I saw it again and some of my reservations disappeared. However, the viewers were largely bemused, always, or almost always applauding at quite the wrong moments. For example: an ovation when the cop tells the mother: ‘it’s the parents’ fault, madam’. They thought that statement was a reflection of your own views, but I know it’s the opposite, because the character of the mother is truly chilling. On my second viewing, what moved me most was your tenderness towards your characters. But Pudovkin only needed to see The Young and the Damned once to understand it and to say as much in places like Pravda. I was too under the weather in April to be able to remember now precisely what he said in private, but it was basically that in a festival where the films from capitalist countries were generally dismal and dispiriting, your film (and the Italian films) introduced a sense of condemnation, a cry of rage, or in other words, hope. You will also have heard that The Young and the Damned has been a great success in Paris for two months now. I haven’t been to Studio Vendôme yet (the old Opéra cinema, Avenue de l’Opéra), but everyone tells me it is full every night. The cinema had been ‘dying’ for a long time and they tried to relaunch it with, amongst other things, that repulsive Swedish film, Fröken Julie (Grand Prix at Cannes), but with no luck. The Young and the Damned is a rejection of society. But what’s most important is that everyone tells me that people (high society people) are leaving ashamed. That doesn’t mean they understand it all, of course, but at least they’ve understood the essential. And they’re not just going to be entertained by the horror, like the Grand Guignol, which is what I feared initially. You may know that at first it was practically sponsored by Le Figaro (even more repugnant in 1951, if possible, than in 1930 in the days of Coty and The Golden Age); a ploy by the distributor of course. Still, The Young and the Damned did not have the impact Le Figaro expected, which is crucial. I was talking about you for hours yesterday with the Lotars, going over so many old and shared memories. They had been interviewed by little Pierre Kast, who wrote an article in Cahiers du cinéma (Lulu and Viñes will have sent it to you) full of memories of your friends, and in which you are represented, at the end of the day, as a Rimbaud who removed himself forever to an inaccessible Harar, or like a Gauguin who never wrote from Tahiti. Apart from the tendency to bury you definitively in ‘other places’, there is little to say about this ‘Search for Buñuel’. However, I really disliked the other Cahiers du cinéma article: the first one. I wrote a letter correcting Little Kast (in reference to the part where he referred to me without naming me). You’ll find a copy of my letter to Kast enclosed, as well as cuttings from my three articles on The Young and the Damned published in L’Humanité, Les Lettres françaises and L’Écran français. I expressed some reservations, as you’ll see, but it would have been worse if I’d written them the day after Studio 28 and before our (last) meeting on the Champs-Élysées (or even just after it). And I also believe that my reservations have faded (although they haven’t yet disappeared altogether). What irritated me most about Little Kast’s article was that he called into question and in the worst possible faith, what I had said about your three films in my Histoire du cinéma. Those three pages were difficult for me to write at the time. I made a real effort to put in them, in good faith, what I thought at the time (and what I’m sure you also thought), between 1927 and 1932. At that time, I think I was a witness, rather than an historian. Nevertheless, witnesses are often confused. If you think that at any point in those three pages I betrayed your principles, do please tell me. I could make corrections to future editions, or to the international editions that are underway. I’m very grateful for the magazines you sent me on Mexican cinema. They will be very useful for the next book I’m preparing (film from 1939 to 1952). But on a personal note, I should like you to keep your promise: to send me the photographs of the Vallée de Chevreuse from 1932. I so much loved the photo you took of poor Norma. I have no other photograph of Pierre Unik and you. If you can, please send me those negatives. I saw a still from your new film. The Lotars mentioned a letter you sent to the Viñes, they tell me you think it’s a very optimistic film. Bravo. And above all, I would be pleased (and here I think I speak on behalf of all your friends) if the success of The Young and the Damned would allow you to return to France. With your wife and children. You must tell your producer that The Young and the Damned would not have sold as well nor earned as much had you not come over to prepare its release (it’s true). And that its chances of winning the Grand Prix at Cannes would have been much higher if you had been at the Festival (even more true). For all these reasons, they must pay for your travel and an extended stay in Paris at the beginning of 1952, or when the Cannes festival is on. Until later. Impatiently awaiting your next film. My wife joins me in sending you our warmest regards and best wishes, Georges Sadoul 3 rue de Bretonvilliers PS I quoted from your letter in my response to Kast and in the article for L’Écran français. Please forgive me, although I’m sure you’ll bear me no ill-will for doing so. I can’t find L’Humanité, but I think Lulu and Ricardo will send it to you.

Jo Evans & Breixo Viejo, Luis Buñuel: A Life in Letters

#jo evans#breixo viejo#luis bunuel: a life in letters#georges sadoul#luis bunuel#los olvidados#vsevolod pudovkin

0 notes

Text

#gif#gifmovie#film#movie#black and white#vintage#1920s#20s#Mother#Vsevolod Pudovkin#Nathan Zarkhi#Maxim Gorky#Anatoli Golovnya#dystopian#dystopia#post apocalypse

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vsevolod Pudovkin, {1953} Возвращение Василия Бортникова (The Return of Vasili Bortnikov)

#film#gif#vsevolod pudovkin#Возвращение Василия Бортникова#The Return of Vasili Bortnikov#1953#landscapes#stalinist cinema#marked frames#static screens#people#sunflowers#wind#storm#animals#summer#winter#colour#soviet cinema#cccp#soviet union#male filmmakers#feature length#1950s#sunbeams

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vsevolod Pudovkin, un pionero del cine soviético, transformó la industria cinematográfica con su estilo de montaje y creatividad. Sus películas "Mecánica del cerebro" y "Fiebre de ajedrez" son testimonio de su genialidad y siguen inspirando a cineastas de todo el mundo.

0 notes

Text

Mother (1926), directed by Vsevolod Pudovkin (February 16, 1893 – June 30, 1953).

19 notes

·

View notes