#georges sadoul

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

To Georges Sadoul

Paris, 24 October 1966

My very dear Georges, I was so glad to get your letter and will certainly, as agreed, pay you a visit. I’ve kept the letter, because the itinerary is so detailed.

I’m going to leave it a few days, because I spend Sundays alone in my room to give my terrible hearing a rest from the daily racket.

Also, I’m too old now to get through a 10-hour working day without having to sit down, fed up with some leading lady’s miniskirt or annoyed at having to choose between a 35 or a 40mm lens. They both can go to hell. So I’ll warn you when I’m coming. It’ll be as soon as I finish the film though (so still another six weeks away).

Give Ruta a very affectionate hug from me, and my unconditional friendship for you as always.

Luis Buñuel

Jo Evans & Breixo Viejo, Luis Buñuel: A Life in Letters

1 note

·

View note

Text

Exactly 100 years ago, one of Charlie Chaplin's greatest films, "The Gold Rush" - 1925, was made. It was about this, undoubtedly the best comedy in the history of silent cinema, that Chaplin said that he would like to be remembered for this picture.

In a rather accidental way, Charlie Chaplin came up with the idea to make the film "The Gold Rush": while having breakfast with Mary Pickford, he saw stereoscopic photographs of gold prospectors at the Chilkoot Pass in the Klondike in 1898. The photos were accompanied by a description of the hardships that the tired searchers had to endure. Then he read a book about George Donner's famous expedition on the California trail in 1864 and about the tragedy that befell them in the Sierra Morena Mountains, which led to the members of this expedition turning into cannibals because they were left without any means of subsistence. It was this case that inspired the most famous and loudest film by Charlie Chaplin, "The Gold Rush". In December 1923, preparations for the production of the film began. The film was produced by Chaplin-United Artists, the author of the script, music and direction was, of course, Charles Chaplin, and of course Roland Totheroh was involved in the filming. The film "The Gold Rush" by Charlie Chaplin required incredible effort, in the opening scene showing gold prospectors climbing Mount Lincoln along a 700-meter path, of which 300 meters were uphill, as many as six hundred men were involved. It was similar with many other scenes with the participation of excellent cinematographers: Jack Wilson and Mark Marlatt. Operators of that time had to be able to cope, the equipment was of great quality, but lacked today's improvements. The implementation took almost two years, also in the summer months: 73,000 were used. cubic meters of sawn timber, 200 tons of plaster, 285 tons of salt and 100 barrels of flour went into artificial wood and snow. At the beginning of the 1920s, there were no companies in Hollywood that dealt with special effects - they were only the result of the arduous, artistic work of the then decorators, scriptwriters, cinematographers and prop makers. The famous scene with the hut hanging over the cliff was shot partly using a model - perfect work, the viewer is unable to figure out what the model is. Among the wonderful actors accompanying Charlie Chaplin, such as: Mack Swain, Tom Murray, Lita Gray, Betty Morissey, actress Georgia Hale was hired. Final filming took place on May 14-15, 1925, then Charlie Chaplin personally edited the film - from April 20 almost until the premiere, which took place on June 26, 1925 at Graum's Egyptian Theater in Hollywood. The production cost Chaplin a total of $923,886.45, and over time the film was expected to generate a profit of $6 million. "The Gold Rush" is a perfectly shot film, wonderful, unforgettable cinematography, and, above all, the profile of Charlie the tramp himself, whose level of acting is classed at the highest! However, Chaplin's talent is not only acting, he was also a great improviser, dancer, and comedian. His famous scenes in which he chews the sole of a shoe, winds the laces on a fork like spaghetti, and the famous, so-called bun dance, is an unconventional improvisational show, and at the same time, artistry of the highest order. The film "The Gold Rush" is "the most beautiful film love poem", a timeless work that will remain forever in memory.

Based on the books - "Chaplin: His Life And Art" by D. Robinson, "My Autobiography" by Charles Chaplin, "Charlie Chaplin" by G. Sadoul and others.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vía Groupe Surréaliste Internazionale Daniel Ollivier

Max Ernst ~ Loplop Introduit les membres du groupe surréaliste, 1931

Collage of photographs, pencil and frottage

En partant du haut à gauche, Yves Tanguy, Louis Aragon, Alberto Giacometti, René Crevel, Georges Sadoul (from behind with raised arms); from center left, Luis Buñuel (before helmeted figure), Benjamin Peret, Tristan Tzara, Salvador Dali, Max Ernst, Gala Éluard, André Thirion (below Ernst), Paul Éluard, René Char (arm raised), Maxine Alexandre; below André Breton, Man Ray

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Orphée (Jean Cocteau, 1950)

Cast: Jean Marais, François Périer, María Casares, Marie Déa, Henri Crémieux, Juliette Gréco, Roger Blin, Édouard Dermithe. Screenplay: Jean Cocteau. Cinematography: Nicolas Hayer. Production design: Jean d'Eaubonne. Film editing: Jacqueline Sadoul. Music: Georges Auric.

Jean Marais and François Périer in Orpheus (1950) dir. Jean Cocteau

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

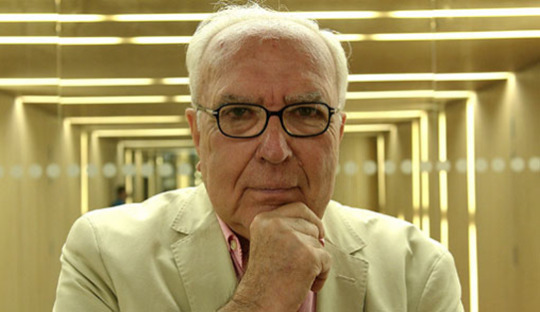

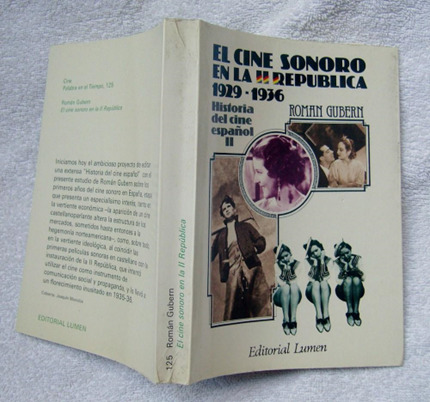

ROMÁN GUBERN

MI OTRO PIGMALION

(“Nada es permanente a excepción del cambio. La permanencia es una ilusión de los sentidos”. Con esta reflexión de un filósofo clásico, Heráclito, doy fin a esta larga serie de 10 años de trabajos sobre cine. Mil gracias y mil perdones a cuantos hayan tenido la osadía y paciencia de leerlos).

Gracias a un gran amigo, ya desaparecido pero que siempre tengo presente, me acerqué al cine cuando era un adolescente que acababa de abandonar el pueblo para marchar a la capital a realizar el curso que entonces se denominaba Preuniversitario y que era selectivo para ingresar en la Universidad. Corría el año 1965 y en los meses siguientes me fui enterando que existía un cine más divertido, pero al mismo tiempo más profundo y más artístico que la mayoría de las películas que nos pasaban en el Palacio Erisana, en el Salón Alhambra o en las escasas películas que se veían en aquella televisión en blanco y negro. En Sevilla tenía la posibilidad de ver películas que seguramente no llegarían al pueblo y tendría opción de ver “otro cine” en aquellos cineclubes de las diferentes facultades universitarias. Mi amigo fue una especie de Pigmalión para mí.

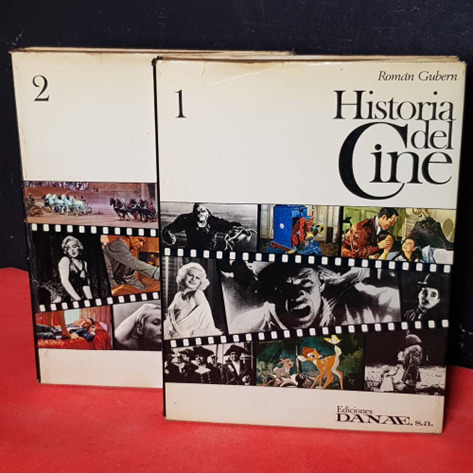

Yo me interesé rápidamente por el tema, pero me faltaban fuentes informativas. Acudí – después de ahorrar durante varios meses – a dos fuentes: “Historia del cine mundial de los orígenes a nuestros días”, de George Sadoul, que era una especie de “biblia” del cine para los cinéfilos y “La historia del Cine”, en dos grandes tomos, de Román Gubern. Debo confesar que el oráculo Sadoul no me convenció. Sin embargo, Gubern me sedujo desde el primer instante y me convertí en un fiel seguidor suyo, un devorador de muchos de sus textos. Román Gubern fue el otro Pigmalion que me acercó al mundo del cine. A él va dedicado este pequeño homenaje.

“Se empieza a ser sabio cuando uno comprende que, incluso en su especialidad, ignora mucho más de lo que sabe”. Para decir esa frasehay que tener un bagaje profesional y moral de gran altura, sobre todo si quien lo dice presenta la trayectoria de Román Gubern (Barcelona, 1934). Su figura sobrepasa las fronteras de la cinematografía y para exponer, aunque resumido, su curriculum necesitaríamos varios folios; no obstante hay va un pequeño resumen: Doctor en Derecho por la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona y Catedrático de Comunicación Audiovisual de la misma Universidad; profesor en las Universidades de la Sorbona, Harvard, Yale, Southern California (Los Ángeles), Venice International; conferenciante en el MoMA de Nueva York; investigador en el Massachusetts of Technology; profesor de Historia del Cine en el California Institute of Technology (Pasadena); presidente de la Asociación Española de Historiadores del Cine; miembro de la Association Française pour la Recherche sur L’Histoire du Cinéma; Miembro de la New York Academy of Sciences, de la American Association for the Advancement of Science y del Comité de Honor de la International Association for Visual Semiotics. Abruma la formación tan heterogénea de Gubern, que abarcó la historia, la literatura, el cine, los comics, la filosofía, el derecho o la comunicación. Guionista, crítico, director, escritor, profesor, su relación con el cine ha sido enorme.

Ha escrito cerca de 50 libros sobre cine, comunicación y comics. Ha publicado infinidad de artículos en El País (pueden revisarse por Internet). Pero además su labor no solo ha sido teórica, sino que ha escrito varios guiones cinematográficos. Entre sus libros más destacados podemos señalar: Godard polémico (1969), Historia del cine (1969), El lenguaje de los cómics (1972), Mensajes icónicos en la cultura de masas (1974), Un cine para el cadalso. 40 años de censura cinematográfica en España (1975), El cine español en el exilio (1976), El cine sonoro en la II República, 1929–1936, (1977), La caza de brujas en Hollywood (1987), Proyector de luna (1999), Patologías de la imagen (2004) o Cultura audiovisual (2013). En colaboración con Javier Coma o Luis Gasca escribió vario textos sobre el comic y su influencia en la cultura. Dirigió el Cine Club Universitario de Barcelona en los años 50. Su colaboración con la prensa escrita se realizó en revistas como Cinema Universitario, Nuestro cine, Triunfo, Destino o El País. Fue también director del Instituto Cervantes de Roma.

Escribió varios guiones tanto para el cine como para televisión. Para el cine escribió Mañana será otro día, España otra vez, Un invierno en Mallorca, Dragón Rapide o El largo invierno, luego dirigidas por Jaime Camino y Espérame en el cielo, de Antonio Mercero. Como cineasta independiente escribió y dirigió en 1964, Brillante porvenir y en 1969, Costa Brava.

Sus trabajos como historiador nos han acercado al cine de la II República o al impacto de la censura a lo largo de los años. Su labor como investigador también ha sido encomiable, llegando a descubrir una película de Buñuel de 1930 sobre la familia de Salvador Dalí (una película doméstica pero no exenta de interés) y durante su estancia en Francia dos películas de Benito Perojo con Concha Piquer que se creían desaparecidas: El negro que tenía el alma blanca, de 1927 y La bodega, de 1929.

En definitiva, un intelectual de primera línea del que se pueden sentir orgullosos no solo el cine español en particular, sino la cultura española en general y que mantiene una claridad mental envidiable a sus 90 años. En una entrevista del año 2020 expuso con lucidez su impresión sobre la situación político social de los últimos tiempos:

“La verdad es que lo que está ocurriendo en Cataluña me tiene asombrado y perplejo, y no entiendo cómo en un estado europeo, en una democracia como la española, puede haber un movimiento insurreccional activo. Hablo con muchos amigos franceses, alemanes, etc., y están perplejos al ver que hay una insurrección en toda regla de una parte de un estado democrático europeo. Es verdad que la política es compleja, que hay muchos puntos de vista, muchas creencias, pero siempre que me preguntan digo que, antes que nada, me siento europeo. Luego, puedo ser español, y catalán, pero primero europeo, porque además, he vivido en París, en Roma, y conozco Europa bastante bien. Pienso que la situación española es complicada, pero como sufrí la dictadura de Franco que era la más fascista, y por eso marché de España, comparándola con la situación actual, desde luego que ahora estamos mucho mejor, pero me sigue incomodando mucho la situación en Cataluña, y le diré por qué: en el franquismo, los catalanes, junto con los madrileños, gallegos, andaluces, etc. luchamos contra la dictadura; y durante la Guerra Civil, de la cual soy hijo porque nací en 1934, cayeron en los frentes y muriendo juntos catalanes, madrileños, extremeños, andaluces…, luchando todos contra el fascismo. Para mí, ese es el pacto de sangre. Es cierto que en España hay culturas diversas: Euskadi, Cataluña o Galicia, y la Constitución las reconoce con personalidad propia, pero a mí personalmente, esta ruptura que se propone desde Cataluña me duele mucho como catalán”.

Espero y deseo que Román Gubern nos acompañe, todavía, muchos años…

19/10/2024

1 note

·

View note

Text

La Pointe Courte: How Agnès Varda “Invented” the New Wave

“In September 1997, I saw Agnès Varda introduce a brand-new 35 mm print of her first feature film, La Pointe Courte (made in 1954), to an admiring audience at Yale University. More astonishing than the luminous black-and-white images was Varda’s claim that she had seen virtually no other films before making it (after racking her brain, she could come up with only Citizen Kane). Whether Varda’s assertion was true or the whim of an artist who does not wish to acknowledge any influence, La Pointe Courte is a stunningly beautiful and accomplished first film. It has also, deservedly, achieved a cult status in film history as, in the words of historian Georges Sadoul, ‘truly the first film of the nouvelle vague.’ ...”

Criterion

W - La Pointe Courte

Criterion: La Pointe Courte

YouTube: Theatrical Trailer

May 2011: The Beaches of Agnès, 2011 December: Interview - Agnès Varda, 2013 February: The Gleaners and I (2000), 2013 September: Cinévardaphoto (2004), 2014 July: Black Panthers (1968 doc.), 2014 October: Art on Screen: A Conversation with Agnès Varda, 2015 September: Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), 2017 February: Plaisir d’amour en Iran (1976), 2017 April: Agnès Varda’s Art of Being There, 2017 April: AGNÈS VARDA with Alexandra Juhasz, 2017 August: Agnès Varda on her life and work - Artforum, 2017 October: Agnès Varda’s Ecological Conscience, 2018 March: Faces Places - Agnès Varda and JR (2017), 2018 July: Vagabond (1985), 2019 March: Agnès Varda, Influential French New Wave Filmmaker, Is Dead at 90, 2019 April: Mur Murs (1980), 2020 May: Socialism and cha-cha-cha: Agnès Varda's photos of Cuba forgotten for 50 years, 2020 August: Four Ways of Looking at Agnès Varda, 2022 January: From Here to There (2011)

0 notes

Text

Safi Faye, a pioneer filmmaker

Safi Faye is an emblematic figure of African cinema, one of the first women on the continent toassert herself as a director, particularly of documentaries.

It was a decisive encounter that led Safi Faye to launch her career in cinema. In 1966, when she was a young teacher in Dakar, she met the director Jean Rouch during the World Festival of Black Arts. He gave her a role in Petit à Petit (1969). She quickly flew to France and studied cinema at the Louis-Lumière school and ethnology at the EHESS. In 1972, she directed her first short film La Passante, based on Baudelaire's poem Les Passants. « It shows the acculturation in which we were» she says.

With cinema, Safi has the ambition to film her country, Senegal, but above all to highlight characters who resist the weight of colonial history, political corruption and patriarchy. Safi Faye is a pioneer, the first woman director on the African continent. She shot her first feature film, Lettre paysanne (Kaddu Beykat), in 1975. It deals with the economic problems of the rural world. The film was rewarded and noticed all over the world: it was the starting point of the African feminist cinema. But Lettre Paysanne was censored in her country, refused by Adrien Senghor, the president's nephew, then Minister of Agriculture, because the film tells of «swindling illiterates ». When she talks about her film, Safi says: « I show myself and I go back to my corner to make films and try to make things change »

Her second feature film, Fad'jal (1979), shot in her native village and awarded the George Sadoul Prize in 1975 and many other prizes, deals with the opposition between tradition and modernity. Other edifying documentaries follow: Goob Na Nu (The Harvest is Over, in 1979) or Les Âmes au soleil (1981), which evoke both work and the condition of women. It is only with her last feature film Mossane (1996) that Safi tackles fiction. This film starts from a legend, invoking spirits and deities, to thwart the arranged marriage to which the young and beautiful Mossane is condemned. The film was presented in the Un Certain Regard section of the Cannes Film Festival. Safi Faye then stopped making films. This selection in Cannes is one of the rare marks of recognition from the profession. Note that in 2018, she was also the guest of honor of the CNC at the Cannes Film Festival on the occasion of the presentation of the restoration of his film Fad'jal in the section Cannes Classic's.

To conclude, I propose to end with these words proposed by Safi Faye on the occasion of her «Film Lesson » at the Créteil Women's Film Festival in 2009.

« I chose the rural world, because I am a farmer [...]. I wanted to emphasize this world which alone can save Africa [...]. I imposed that I am a peasant, that I am not from the city and that no African is from the city ».

Juliette Corbel Vivas

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Olivier Assayas - Something in the Air (2012)

#film#olivier assayas#something in the air#après mai#tibetan book of the dead#j'accuse#situationist international#gasoline#georges sadoul#2012#mine

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

CADAVRES EXQUIS 1927-1928 yves tanguy, andré masson, pierre unik, suzanne musard, jacques prévert, andré thirion et georges sadoul

#CADAVRES EXQUIS#1927#figure#yves tanguy#andré masson#pierre unik#suzanne musard#jacques prévert#andré thirion#georges sadoul

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Uno schizzo mi dice di più di un lungo rapporto.

11 notes

·

View notes

Quote

To Georges Sadoul Mexico City, 25 June 1953 My dear Georges, I’m truly ashamed not to have replied to your letter by return post, but you are already familiar with my horrible laziness when it comes to letter writing. I suppose though, that late is better than never. Thank you for your very interesting comments about the Cannes Festival and about all the racket the ‘revanchists’ made against my film, which came as a considerable surprise to me. I think the Cannes Festival is going from bad to worse, it’s become a kind of Salon d’Automne of the old days. I can’t believe the prizes awarded this year for Rossana, for example, or the ‘International Award for Good Humour’. As for This Strange Passion, it’s not, as Cocteau thought, a film I made ‘to make money’. Failure or not, and in spite of some trite sequences, it’s a film I had great interest in making. I’m not sure what people expect of me, but you can’t expect a masterpiece given the conditions I work under here in Mexico! When you think that every film I’ve made down here has been shot in seventeen (The Brute, for example) to twenty-three days (This Strange Passion). I would love to find a good story and direct it in France. Here in Mexico, we don’t have a single actor or actress of any calibre. I’ve discussed your book with a friend of mine who is the head of a publishing house. He’s asked me to ask you how much Fondo de Cultura Económica offered for your Chaplin. I’m sure they will make you a better one, but they want to find out how much you’ve been offered, so they don’t suggest the same amount. As soon as I have a little money saved up I will come to Paris; I’m really keen to see old friends and, above all, to have long conversations with you. I hope it will be this winter. Yours, Buñuel

Jo Evans & Breixo Viejo, Luis Buñuel: A Life in Letters

0 notes

Photo

Jean Marais in Orphée (Jean Cocteau, 1950) Cast: Jean Marais, François Périer, María Casares, Marie Déa, Henri Crémieux, Juliette Gréco, Roger Blin, Édouard Dermithe. Screenplay: Jean Cocteau. Cinematography: Nicolas Hayer. Production design: Jean d'Eaubonne. Film editing: Jacqueline Sadoul. Music: Georges Auric. Though it's not as sumptuous as his Beauty and the Beast (1946), Jean Cocteau's Orphée seems to me in some ways the more beautiful film. It embraces ugliness as a foil for beauty in ways that the earlier film doesn't. (As many have noted, the Beast of Cocteau's film is too beautiful a creature to inspire the disgust he presumably was doomed to evoke.) In Orphée the ugliness is that of the modern world, still in the time of the making of the film filled with the rubble of war, such as the bombed-out Saint-Cyr military academy that serves as the film's underworld. So the entire film is a kind of balancing act between antagonistic forces, not just ugliness and beauty or ancient myth and modern reality, but also and especially Eros and Thanatos. It is, of course, dreamlike, not in the cliché surrealist manner of most movie dreams, but in the oddities of its settings: an upstairs bedroom, for example, accessible only by a trapdoor or a ladder outside the window. I'm particularly drawn to the low-tech special effects, created by obvious means: film run backward, rear-screen projection, sets built on an incline. Even if we know how the tricks are done we marvel at the magic they add. Cocteau has de-sentimentalized the Orpheus myth. The marriage of his Orpheus (Jean Marais) and Eurydice (Marie Déa) is hardly an ideal one: He's a self-centered crank, and she's a wimp. But by doing so he has made the film's "happy ending" more poignant, as the couple return to life in improved versions and the Princess (María Casares) and Heurtebise (François Périer), a marvelously imagined character, wander deeper into the underworld. It's an ambiguous fairytale at best.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photomontage pour le dernier numéro de ‘La Révolution Surréaliste’ le 15-12-1929.

Toile de André Magritte avec Louis Aragon, André Breton, Yves Tanguy, Salvador Dali, Luis Bunuel, André Magritte, Jean Caupenne, Maxime Alexandre, Max Ernst, Paul Eluard, Marcel Fourrier, Albert Valentin, André Thirion, Georges Sadoul, Paul Nougé, Pierre Coumans...

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

March 9, 2021: Orpheus (Review)

Man, I really should’ve taken a film class in college.

Orpheus, understand, is a fantastic film...that I am highly unqualified to judge. I man, I’m gonna give it a shot, but this isn’t gonna be a professional film essay on the reflections (ha) of this movie on the French political scene at the time or anything like that. It’s just gonna be what I thought of the movie.

And what did I think of the movie? Well, other than letting me refresh my French language skills a little, I had an excellent time with this movie. It’s stunning, it’s groundbreaking, it’s breathtaking, and it’s a great example of what can be done with clever filmmaking and practical effects. I mean, what would you expect? It’s Jean Cocteau.

I’ve only seen one of his films prior to this, La Belle et la Bête, and that’s a beautiful film in its own right, with equally fantastic effects. Like Aladdin and The Thief of Bagdad, Disney took a lot of that film’s aesthetic and themes from Cocteau’s version of the story. What can I say, they’ve got good taste.

As for me...I’d like to think I have good taste, but that’s technically what this whole thing is for, right? To broaden my palate and further define my taste. Sooooo, what exactly did I think of this one? Check out the Recap (Part One | Part Two) if you want to see my reaction to the movie as I watched it! Otherwise...

Review

Cast and Acting: 9/10

Jean Marais is our star here, and one of Cocteau’s favorites (he was also the Beast and the Gaston in La Belle et la Bête four years earlier). He plays Orpheus like an absolute dick most of the time, which is interesting, since the character is the prototype of a tortured artist, so it makes some sense. However, that portrayal is somewhat on the writing, less so than Marais’ performance. That said, he’s still fantastic in the role. François Périer is also fucking fantastic as Heurtebise, and is genuinely my favorite character (and I still think he was meant to represent Hermes). María Casares intricately plays her complex character, an aspect of Death in love with a poet. Which, yeah, rules. And Marie Déa and Édouard Dermit were...fine as Eurydice and Jacques. Yeah, they were both very good, but I can’t say that they were perfect, especially Dermit. But still, all of these were strong performances in a strong movie.

Plot and Writing: 9/10

Oh boy, the PLOT. Jean Cocteau’s screenplay is a great example of a screenplay adapted from source material, but doing something completely different with that material. It’s adaptation done...well, right, but also done creatively. Now, obviously, that’s done mostly through the visual rather than the verbal, but it’s still done VERY well. I mean, come on, they turned the tale of Orpheus into a Hades and Persephone love story as well!

Yeah, I didn’t mention it in the Recap, but think about it! An aspect of Death, referred to as royalty, falls in love with a mortal human. Said mortal is also in love with another woman (allegedly). Now, yeah, that’s basically the whole “even the Gods loved Orpheus” thing, but HE also falls in love with HER. She’s Hades, and he’s Persephone! But in the end, he needs to return to the mortal world for springtime, while Hades must remain in the Underworld...for now, anyway. Maybe that’s e over-reading a bit, but I can see it. In any case, the screenplay’s adaptation of the original story is fantastic. Not the easiest to dissect, maybe (the whole “Death loves Orpheus” thing sort of comes out of nowhere), but still great!

Directing and Cinematography: 10/10

I mean...it’s Jean Cocteau (and Nicolas Hayer for the cinematography). What else am I gonna do, give him a nine and say that it wasn’t perfect? I mean...come on. It was amazing. It’s Jean goddamn Cocteau. The camera movements and shot framing are goddamn spectacular IT IS JEAN FUCKING COCTEAU

Production and Art Design: 8/10

Art design was only really OK, though. Yeah, sorry, sometimes it struck me quite well, but I don’t know that I can say the production and art design was as much of a stand out for this one. The only reason is because the camera and editing really did all of the work here, real talk. Cocteau made this movie look amazing, not as much the movie itself. But don’t get me wrong, the movie does still look amazing. Whomever did the location scouting did a great job in finding an abandoned military school for the Underworld, because it’s great looking. However, again...the way it’s all shot isn’t about the set itself, it’s about the camera work. And one other thing...

Music and Editing: 10/10

MMMMMMMMMMMWAHCHEF’SKISSBABY

Yeah, now, this is an amazing goddamn editing job be Jacqueline Sadoul, and the music by Georges Auric is equally as fantastic. This is a gorgeous film, and the editing is a HUGE part of that. Practical effects is one thing, but clever editing also made this film work as well as it did. There’s so much to unpack with that, it’s genuinely hard to go into. But hell, I don’t need to. Watch this film, especially if you have HBO Max. You’ll see what I mean, because it’s a fantastic looking movie that’s genuinely hard to describe to the unfamiliar.

92%, and I’m not looking back.

Well, one day I probably will, because this movie was wonderful, and DEFINITELY worth another watch. Mostly so I can better figure out what’s going on, and what Cocteau’s trying to say. Although, to be fair, this movie isn’t as experimental as film can get, not by a long shot. It’s still beautiful, without a doubt, and it’s absolutely worth a second viewing.

OK. Now that that’s done, let’s go to another country renowned for its fantasy stylings. Or, to be more accurate...let’s go back. You guys ready to get spooked?

March 10, 2021: Ugetsu Monogatari (1953)

#orpheus#Orphée#orpheus 1940#orphee#cocteau#jean cocteau#orphic trilogy#jean marais#François Périer#María Casares#Marie Déa#Juliette Gréco#Édouard Dermit#fantasy march#greek mythology#user365#365 movie challenge#365 movies 365 days#365 Days 365 Movies#365 movies a year#useranais#usercande

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Orpheus (Orphée) [1950]

Country: France

Written & Directed by: Jean Cocteau

Cinematography by: Nicolas Hayer

Edited by: Jacqueline Sadoul

Music by: Georges Auric

Production Design by: Jean d’Eaubonne

#Orpheus#Orphée#Movie#France#Jean Cocteau#Nicolas Hayer#Jacqueline Sadoul#Georges Auric#Jean d'Eaubonne#The Criterion Collection#DisCina International#Home Vision Entertainment#1950s#Fantasy#Drama#Romance

0 notes

Text

松本俊夫実験映像集1−詩としての映像−

本人解説要約

【西陣】

youtube

●1961年発表。

●カメラマンは日本映画の天皇とも言われている宮島義勇が自ら名乗り出てくれた。

●詩人の関根弘。

●日常的な風景の積み重ねで見えなかった内向的な部分が見えてくる。

●見えない怖いもの、鬱屈した気分を拾い集めながら発酵させるスタイル。

●何かが出てくるのか出てこないのかは分からずに撮っている。

●インタビューを素材にしてモンタージュ(映画・写真で、いろいろの断片を組み合わせて、一つの場面・写真を構成すること。そうして作ったもの。)にしている。

●機械化(生産の合理化)と手織り(独自性)の対比。

●基本織物を織っている場面の積み重ねで進んでいく。

●織っている人の顔をほとんど出さないようにしている。

●西陣の全体像を作り上げさせる映像。

●おまじないが非常に目立つ世界を映している。

●西陣の中に沈んで溜まっていく心と身体の病が見えてくる。

●展示会等、表面の華やかな面を西陣のイメージとして作り上げるがその裏では歴史を背負った習慣が人々の意識を作り上げている。

●能を踊っているのはカンジヒデオ。

●蜘蛛の”糸”と織物の”糸”を掛けている。

●当時は五寸釘の遊びという子供の遊びがあった。

●釘抜き地蔵に職業病で悪くなっている身体の釘を抜いてもらうというもの。(これもおまじないの一部)

●西陣の良くも悪くも変わらない体質を表現。

●西陣の人手不足。

・若者を募集するビラ、集団就職。

・西陣の過酷さをそこまで過酷と思わない過酷な農村にいた中学生たちを集める。

●細い路地、屋根。

●経営者たちの会議を誇張して映し、モンタージュにしている。

・会議室の隣には誰もいない部屋がある。

・何か大きく穴が空いている様を表現。

・空洞性

●状況が行き詰まっているのをあるがまま映し出している。

●基本寄りでしか撮影していないが最後のみ、織る人の引きの画を映している。

●混沌とした世界。

●映画では最後までメッセージを伝えていない。

・観た後に考えさせる映像にしている。

●第13回ベネチア国際記録映画祭でサン・マルコ金獅子賞を受賞。

【石の詩】

youtube

●1963年、TBSで放映された。

●アーネスト・サトウが700枚程白黒写真を撮ってきた。

●それを映像化するつもりだったがプロデューサーが危機感を抱く。

・誰かの「そんなときは松本に聞けば奇抜なアイデアを出してくれる」の一言で松本俊夫に話が来た。

●最初、石の映像のどこに切り口をつけていいか分からなかった。

●エンターテインメントよりも西陣でやったようなシネポエム(映画用語としては「映画自体が詩であるもの」つまり映像による詩的表現のことを指し、文学用語としてはシナリオ形式を借りた詩のことを指す。)のような考えを進めてはいけないかと考えた。

●写真素材は動かない、動きのない石がモチーフ、静物の静止画というのは映画表現から遠く難しいと感じた。

・非映画的。

●じっと眺めていると、別に何か自分の意識の奥底に蹲っているものがこれらの写真によって刺激されることに気が付いた。

●沈黙というのは死に近い世界。

●彫刻家の流政之は「石をみがくと石が生��てくる」と言っている。

●フレームを切り取ったり構築したりする中に映像が表現を孕んでくることによって、石が生きてくる次元で見られるのではないかと考えた。

●死と再生という根源的な題が隠喩されている。

●当時、安保の敗北で全てが終わったという空気になっていた。

・時代の沈滞化。

・63年になると死に近い状況。

・メタファー。

・その中に生が蘇ることをどこかで望みながら胎動を確信することが出来ないでいる。

・歴史のエアポケットのようなところだった。

●石が生きてきたことと映画が息衝き出したことを連鎖的に帯びさせたい。

●写真を映像にするにはアーネスト・サトウの写真のフレームを弄らねばならないが、写真家はフレームを拘って撮影する為に弄られることを酷く嫌う。

・「映像の尺問題があるのでそれがOKなら出来る」と言う。

・最初アーネストサトウは拘りたいと一日時間を置いたが良い手が見つからないとの事で託された。

・この時点で放送まで後10日。

●まずは3日間徹夜してグラフコンテを描き、それをスタッフに渡して指示。

・撮影とコンテを同時進行。

・撮影はすべてコマ撮りにして写真を原画にしたアニメーションにした。

・現像場でエフェクトをかける時間はない為、カメラでエフェクトを直接撮影して付けた。

・それを時間軸へと構成。

・イメージの流れ、時に飛躍をわざと含ます。

●映像内容で無く、素材自体の印象を意識。

・言語内容より言語そのものに刺激を受けるのに近い映像。

●石と作業の素材のみで世界を映し出す。

・沈黙の中に浮かび出す生。

・素材主義。

●音楽は透明な音が聞こえる。

・サウンドを担当した現代音楽の評論家秋山邦晴が石を楽器にしている。

・石から音楽を作っている。

・ミュージックコンクレート。

・速度を落としたり変調したりしたものを6mmテープで合成していった。

●スタッフの不眠不休。オンエアの1時間前に完成。

●出来上がって全体を見てみて初めてこういう映画だったのかと分かった。

●放送後「テレビの常識からかけ離れすぎている」と報道局の局長がひどく怒りプロデューサーは飛ばされてしまう。

・そして松本俊夫はTBS出禁。

●結果、賛否はあったが後にジョルジュ・サドゥールやクリス・マルケルに評価された。

【母たち】

youtube

●1967年発表。

●石の詩からの3年半の間、テレビでも映画でも出禁状態の評判で干されていた。

・焦りも出ていた。

・その間は演劇に携わったりしていたが、やはり映画がやりたいと思っていた。

・映画製作会社「自由工房」を立ち上げた工藤充にやらないかと誘ってもらった。

・電通が絡んでいてスポンサーがプリマハム。

・たまたまプリマハムが当時ハムの中毒事件があってそのイメージを脱却したいとの意図。

・清潔なハムの製造のビデオになるはずだったがそんなのはつまらないし説得力を持たないと思った。

・そこで主婦に目を向けようとした。

●産業映画でなしに時代や人々を見つめる映画にしませんか?と提案。

・それは面白いとなった。

・世界の母親とその子供の姿を捉えることによって生活環境や感情を映し出す。

・共感関心を得られるテーマ。

・説明的ではなく一つの映画として。

・またやらかすともう作れないかもと思い、難解でないものにしようとした。

・「西陣」はベネチア国際映画祭で賞をとっている。

・それでプロデューサー等との葛藤が和らいだ。

・そこで賞を取れるレベルの映画にしようとは思っていた。

・30分くらいの長さにしよう。

・シナリオハンティングの予算はとても無かった。

・ぶっつけで撮影しにいく。

・シナリオではなく意図のみを書き出しスタートした。

・400字ほどの企画書を持って、アメリカ、フランス、ベトナム、ガーナ(アフリカ)の四カ国のオムニバスを撮影しに行った。

・南北問題

●白人が作った文化、社会、それによって苦しむ第三社会の対比。

・あまりキツくは出さずともなんらかの形で出るのではないか。

●予算問題が厳しかったので4カ国で40日間厳守でスタッフと四人旅。

・たまたま松本の発想で寺山修司の詩をコラージュしていた。

・寺山修司から許可をもらった。

・さらに「外国に行った事がないので一緒に行きたい」と言われた。

・寺山修司とも一緒に旅に行くことになった。

●アメリカはその時代ベトナム戦争中。

・黒人差別が露骨に残っている時代。

・そこらを切り口にしてアメリカとベトナム、ガーナ。

・ヨーロッパの経済発展に伴う空虚感を忍ばせるフランス。

・そういった意図でのこの4カ国。

●移動含めて一カ国10日。

・実際に撮影できる日にちは1カ国1週間。

・段取りはできないのでぶっつけで撮影していく。

●アメリカではハーレムにいく。

・当時かなり怖いところだったので、簡単に撮影は出来ない。

・事件が起きるのは夏というデータを取っていたので、事件があまりない冬にはなんとか撮られるのではないかと考えていた。

・現地で本屋を経営する日本人に案内をしてもらうつもりだったが急遽断られた。

・当時は現地の人がビビってしまうほどの状況だった。

・たまたまハーレムの中でアル中のお母さんを捕まえて強引に家まで押しかけて撮影。

●フランスの場合は、道で「こういった母親はいないか?」と聞いて回っていた。

●ベトナムは映像では三個目のシーンだが、最後に撮影した。

・ベトナムに入るには観光旅行の装いをしなければならない。

・アメリカ軍に申請をしようとしたら間に合わない為、世間知らずの若者たちが観光旅行をしながら撮影して入り込んで行っている装いを作ろうとした。

・そのために16mm(他は36mm)で行こうと考えた。

・ちょっとした金持ちのドラ息子だと思わせた。

・寺山修司は仕事で帰国しなきゃいけなかったのでデータや機材を託し、カバンに馬鹿げたお土産をたくさん詰めてベトナムへ行った。

・万一危険な状態になったら案内に従ってほしいと現地の案内人に言われた。

・メコンデルタに行った。

・昼は政府軍、夜はベトコン。

・ある時銃声が聞こえたら、自分たちへの威嚇だった。

・とりあえず捕まって永遠に田んぼを歩かされ、テントに連れてかれて尋問された。

・カメラが銃に見えたと言われた。

・戦場だと知らないで入ったといったらお前らはバカだと言われて強制送還された。

・バカを装って上手く騙したベトナム撮影。

・当時はベトナム戦争の最中だったので子供が死んで泣いている母親もいて深刻感が強かった。

●ガーナに映るときに気持ちを和ませてほしいと言われて最初は躊躇ったがクッションをいれた。

・ガーナでは解放、民主化が上手く進んでいた。

・将来へのビジョンが見えていてハーレムの空気とは対照的だった。

・ガーナの中での黒人の生活は精神的に豊かだった。

・オムニバスの最後に持ってくるのがいいとなった。

・野口英世は高熱病の件でガーナでは特別に扱われていて、それで日本人への対応も暖かかった。

・民族問題、宗教問題はアフリカの新しい矛盾とし��なっていくことをこの頃は予想させなかった。

・紋様のデザインの感覚に驚いていたが何より驚いたのは商品自体の布がメイドインジャパンだった。

・アフリカの映像は映画のラストであり、持つ意味は大きい。

●海は母性。

・今この母子はどうしているのだろうかと思う。

●この映像は、普遍的な訴える力を持っている。

0 notes