#Virginia Rankin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

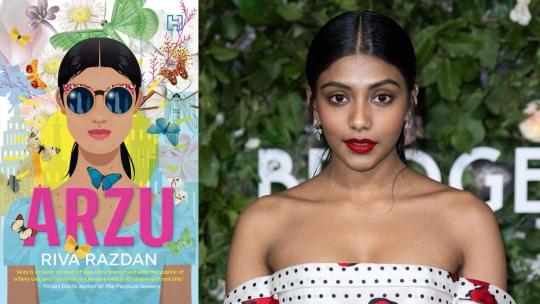

Arzu | Charithra Chandran irá estrelar série dramática

Charithra Chandran, estrela de Bridgerton, vai estrelar a série "Arzu"! Veja mais na matéria. #arzu #serie

Vem série nova por aí! Charithra Chandran, a querida Edwina Sharma de Bridgerton, irá protagonizar a nova série de drama Arzu. Baseada no romance de mesmo nome, a produção irá contar com a direção e roteiro de Geetika Lizardi, que também roteirizou Bridgerton. De acordo com a Variety, Chandran está empolgada para protagonizar a série, que será marcada por glamour e um viés social: Estou…

View On WordPress

#Arzu#Blink49#Bridgerton#Carolyn Newman#Charithra Chandran#Geetika Lizardi#Lilly Singh#Polly Auritt#Riva Razdan#Unicorn Island#Virginia Rankin

0 notes

Text

250 - Her Smell

We've come up on another anniversary episode of This Had Oscar Buzz, and we've got another favorite that long-time listeners have heard us praise before: 2019's Her Smell. Debuting on at TIFF 2018, the Alex Ross Perry film is a daring and ambitious take on the riot grrrls of the early 1990s. Starring Elisabeth Moss as Becky Something, an addict egomaniac who brings her own downfall, the film audaciously immerses us in Becky's destruction (and later climb out of it) in ways that are exhausting and rewarding. Earning stratospheric praise for Moss by even the film's most frustrated viewers, the film was cursed to a microrelease and stayed an Oscar outsider despite vocal critical support.

This episode, we talk about the audacity of both Perry's film and Moss' performance. We also get into the depressing state of independent distribution, Perry's open comments regarding its release and support for Moss' performance, and the Gotham Awards.

Topics also include the film's fake album covers, our appreciation for difficult characters, and our superlatives for the past year of the podcast.

But perhaps most exciting is two bits of news right at the top: our new theme music by Taylor Cole and our newly launched Patreon!! Please consider subscribing and joining us for This Had Oscar Buzz: Turbulent Brilliance over at patreon.com/thishadoscarbuzz!!

Links:

The 2019 Oscar nominations

Her Smell and the state of independent film

Alex Ross Perry campaigns for Elisabeth Moss

Her Smell's fake album covers

Subscribe:

Patreon

Spotify

Apple Podcasts

Google Play

Stitcher

youtube

#Her Smell#Elisabeth Moss#Alex Ross Perry#Agyness Deyn#Dan Stevens#Eric Stoltz#Virginia Madsen#Cara Delevingne#Gayle Rankin#Ashley Benson#Dylan Gelula#Amber Heard#Best Actress#Best Supporting Actress#Best Director#Academy Awards#Gotham Awards#Oscars#movies#Youtube

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rankin Street, Branchland, West Virginia.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

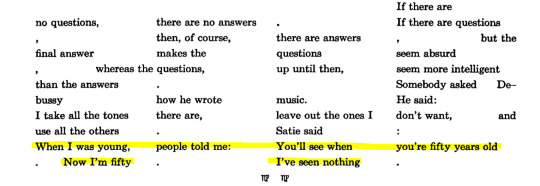

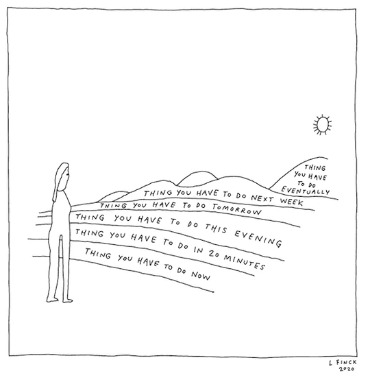

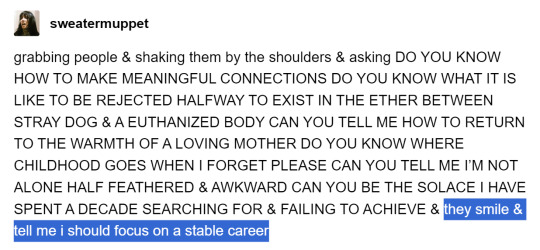

i don't want to grow up i don't want to grow up i don't want to grow up

mary maclane i await the devil's coming \\ @\blaineunderstudy on tiktok \\ virgina woolf the diary of virginia woolf vol. 3: "11 july 1927" (via @hungryfictions) \\ goretzkas-moved-deactivated2023 \\ amy hempel cloudland \\ @ashstfu \\ emil cioran a short history of decay \\ alida nugent \\ @havingrevelations \\ franz kafka the diaries of franz kafka, 1914-1923: "july 5, 1914" (via @dailykafka) \\ claudia rankine the end of the alphabet: "overview is a place" (via @feral-ballad) \\ john cage lecture on nothing \\ holly black the cruel prince (via @existential-celestial) \\ liana finck horizon \\ @sweatermuppet

buy my chai latte

#on self#on identity#on life#mine#my webweaving#webweaving#web weaving#webweave#web weave#web#webs#ww#parallel#parallels#parallelism#compilation#compilations#intertext#intertextuality#comparative#comparatives#the diary of virginia woolf#virginia woolf#amy hempel#cloudland#emil cioran#a short history of decay#alida nugent#claudia rankine#overview is a place

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

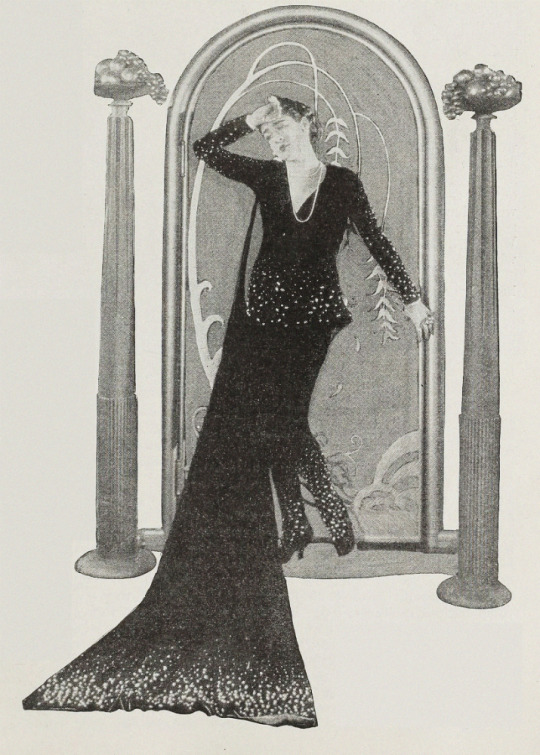

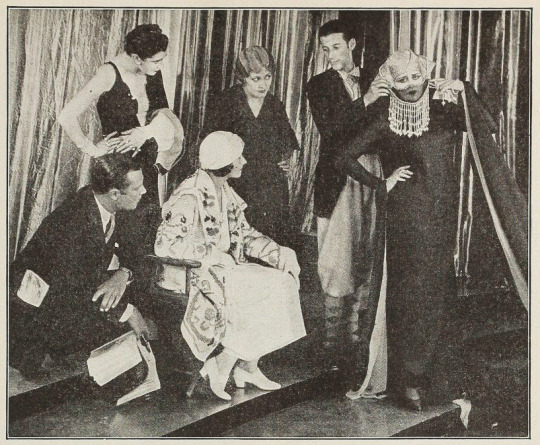

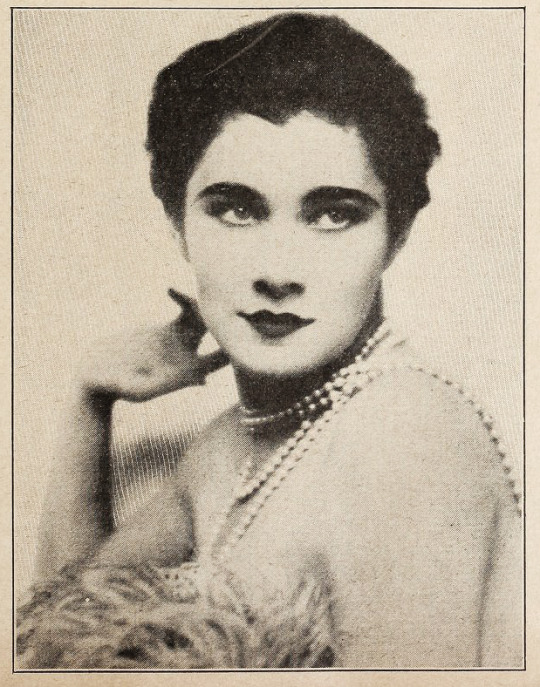

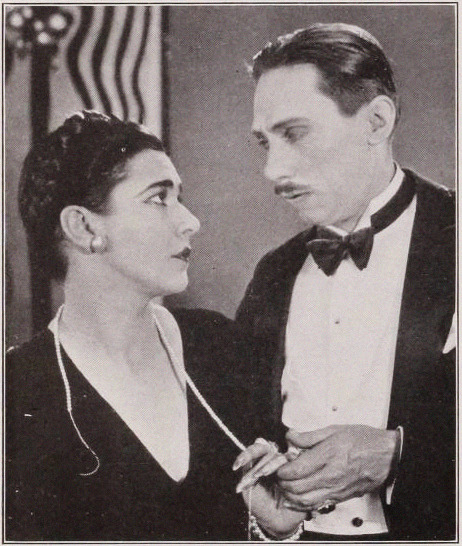

Lost, but Not Forgotten: What Price Beauty? (1925)

Direction: Thomas Buckingham

Scenario & Story: Natacha Rambova

Titles: Malcolm Stuart Boylan

Production Manager: S. George Ullman

Camera: J. D. Jennings

Art Direction: Natacha Rambova

Production Design: William Cameron Menzies

Costume Design: Adrian

Studio: Circle Films (Production) & Pathé Exchange (Distribution)

Performers: Nita Naldi, Pierre Gendron, Virginia Pearson, Dolores Johnson, Myrna Loy, Sally Winters, La Supervia, Marilyn Newkirk, Victor Potel, Spike Rankin, Rosalind Byrne, Templar Saxe, Leo White Maybe: John Steppling, Paulette Duval, Dorothy Dwan, and Sally Long

Premiere: None, general release: January 22, 1928

Status: Presumed entirely lost.

Length: Variously reported as 5000 and 4000 feet (more commonly listed as 4000) or 5 reels

Synopsis (synthesized from magazine summaries of the plot):

Mary, a.k.a. “Miss Simplicity” (Dolores Johnson) is a starry-eyed, country-to-city transplant. She works at a beauty shop operated by a glamorous matron (Virginia Pearson) and owned by the young and handsome Clay (Pierre Gendron).

Mary is in love with Clay, but doesn’t have the nerve or feminine wiles to woo him. The uber-sophisticated Rita (Nita Naldi), however, is chock full of nerves and wile. Rita’s fancy clothes and perfumes and advanced flirting skills leave Mary feeling destined to fail at winning Clay’s amorous attention.

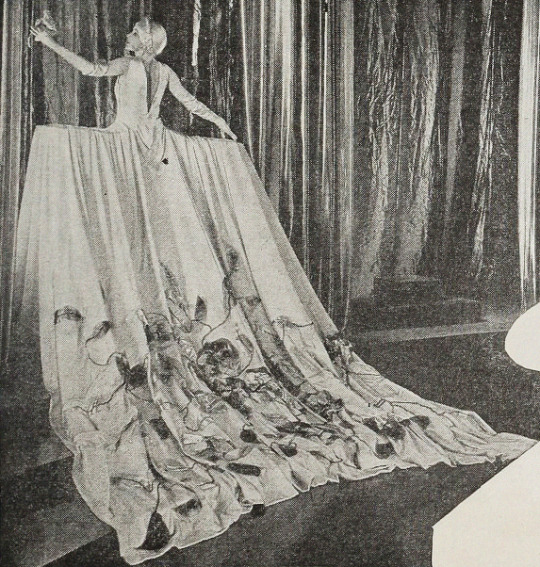

These feelings sublimate into an expressionistic dream for Mary, where she finds herself transformed into a sophisticate like Rita. Her boss is seen as a magnificent wizard, converting her clients into archetypes of glamour: exotic types, flappers, and sirens. Her competition, Rita, is seen as a bewitching spider.

In the end, surprising Mary, it turns out that her fresh-faced, unassuming charm is more appealing to Clay than Rita’s more practiced charm.

Additional sequence(s) featured in the film (but I’m not sure where they fit in the continuity):

Scene of the trials and tribulations of a fat woman trying to “reduce”

Points of Interest:

Only one quarter of Nita Naldi’s Hollywood films have survived (7 extant titles/21 lost or mostly lost titles).

——— ——— ———

What Price Beauty? was the first and only film produced under Natacha Rambova’s own company. Coordinating production for the film was the business manager for Rambova and her husband Rudolph Valentino, S. George Ullman. The couple met Ullman when he was working for Mineralava beauty products, the sponsor of their 1922-3 dancing tour.

When Rudolph Valentino entered into a contract with United Artists, said contract reportedly stipulated that Valentino-Rambova were not a package deal. Therefore, Rambova could not collaborate with Valentino on his productions for United. Possibly as consolation, Ullman funded a production for Rambova while Valentino worked on The Eagle (1925, extant).

For Rambova, What Price Beauty? was meant to be a proving ground for her idea that an artistic film could be made on a modest budget. She also wished to remind people that she was a skilled artist in her own right.

In an interview in Picture Play Magazine from August 1925, Rambova asserts:

“…I do not want the production in any sense to be referred to as high-brow or ‘arty’. My reputation for being ‘arty’ is one of the things that I have to live down, and I hope by this picture, which is a comedy—even to the extent of gags and hokum—to overcome that idea. “A woman who marries a celebrity is bound to find herself in a more or less equivocal position, it seems, and her difficulties are only increased when she happens to have had some artistic ambitions of her own before her marriage. I am afraid that those who have accused me of meddling in my husband’s affairs forget that I enjoyed a certain reputation and a very good remuneration for my work as well before I became Mrs. Valentino.”

“What I desire personally is simply to be known for the work which I have always done, and that has brought me a reputation entirely independent of my marriage.”

There isn’t a vast amount of information on what exactly prevented WPB from gaining release in a timely fashion. If the film was truly nothing more than a ploy to separate Rambova from Valentino, that would be an absurd waste of time, money (~$80,000 in 1925 USD), and talent—Rambova employed soon-to-be famous designer Adrian for costumes and William Cameron Menzies for set decoration. Not to mention that, in front of the camera, Nita Naldi was still a popular star and the Rambova discovery, Myrna Loy, made her quickly hyped debut.

When Pathé finally purchased WPB for distribution in 1928, they did very little to promote the film. Naldi had moved on from the film industry—as had Rambova. And, while Loy hadn’t become the huge star we know today by January of 1928, Warner Brothers had already given her top billing in a number of films. Pathé barely mentions Loy’s role in the little promotion they did do.

To put WPB’s release in the context of Rambova’s personal/professional biography (which you can read more about here):

June/July 1925 – WPB is completed, Rambova and Valentino separate (in July according to Rambova’s mother as quoted in Rambova’s book Rudy)

August 1925 – Rambova leaves Hollywood for New York City, reportedly to negotiate distribution for WPB. She and Valentino would see each other in person for the last time. Rambova leaves NYC for Europe.

September 1925 – Valentino draws up a new will disinheriting Rambova

November 1925 – Rambova returns to the US to act in a film, When Love Grows Cold (1926, presumed lost), a title which Rambova objected to

December 1925 – Rambova files for divorce

August 1926 – Valentino dies

January 1928 – WPB is finally released with no fanfare by Pathé

In my research for my Rambova cosplay, the suspicious production/release history for this film stood out to me. I hoped that I might find some reliable evidence of whether WPB was a consolation prize and/or a scheme to keep Rambova and Valentino apart. Honestly and unfortunately, circumstantial evidence does support it!

After poring over what few contemporary sources cover WPB, there seemed to be no plan in place for distribution as the film was in production. United Artists, at whose lot the film was shot, claimed to have nothing to do with its release. Ullman had a news item placed about negotiating the distribution rights in the East. However, in Ullman’s own memoir, he admits that when he travelled to New York with Rambova, it was in a personal, not professional capacity—navigating the couple’s separation. (Ullman’s book contains many disprovable claims and misrepresentations, so anything cited from it should be taken with a grain of salt.) That said, Ullman’s failure to secure even a modest distribution deal for WPB in a reasonable timeframe speaks to how ill-founded Valentino’s and Rambova’s trust in his business acumen was.

WPB cost $80,000 to produce, which converts to $1.4 million in 2023 USD. While that wasn’t an outrageous budget for a Hollywood feature film at the time, especially one with such advanced production value, it’s certainly an absurd cost if the goal was only to separate a bankable star from his wife and collaborator.

A close friend and employee of Valentino and Rambova, Lou Mahoney, recalled in Michael Morris’ Madam Valentino:

“The picture was previewed at a theater on the east side of Pasadena, and Mahoney remembered the audience reaction as positive, but, thereafter, What Price Beauty? was consigned to oblivion. Mahoney knew why: ‘No help came from anyone, no thoughts of trying to get this picture properly released. No help came from Ullman, Schenck, or anybody else. Their whole thought was that if the picture were a success, Mrs. Valentino would be a success. She would then start producing under the Rudolph Valentino Production Company. But this nobody wanted—except herself, and Mr. Valentino.’”

——— ——— ———

The few reviews from 1928 that I was able to find are not very complimentary of WPB. The critics seem thrown by the film’s tone or genre—reading it as a drama. (Part of that is Pathé’s fault as they listed it as one.) But, according to sources contemporary to WPB’s production, it was intended to be a farcical satire of the beauty industry and social expectations of feminine beauty. Given the simple story, the intentional typage of characters (“The Sport,” “The Sissy,” and “Miss Simplicity”), and the over-the-top-but-on-a-budget art design of WPB, all signs point to high camp. In 1925 as well as 1928, the stodgier side of the critical spectrum would likely fail to see its appeal.

It’s a true shame we can’t find out for ourselves how good, bad, or campy WPB was as of yet, but here’s hoping the film resurfaces!

More about Rambova

GIFs of some of her design work on film

☕Appreciate my work? Buy me a coffee! ☕

Transcribed Sources & Annotations over on the WMM Blog!

#1920s#1925#1928#natacha rambova#nita naldi#cinema#silent cinema#american film#independent film#classic film#classic movies#film#silent film#silent movies#silent era#classic cinema#silent comedy#lost film#film history#history

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The mysterious coffins of Arthur’s Seat.

I popped into the National Museum of Scotland and captured a few shots of these wee beauties. Nobody knows. the full story about them, who made them and why, but a fair bit work went into, they may lack real craftsmanship, and look a bit "naive", but I think they are pretty cool. They have always fascinated me after I read about them in the Ian Rankin, Inspector Rebus book, The Falls in 2001 In 1836, five boys were hunting rabbits on the north-eastern slopes of Arthur’s Seat, the main peak in the group of hills in Holyrood Park, in a small cave in the crags of the hill they stumbled across seventeen miniature coffins carved in pine and decorated with tinned iron. Carefully arranged in a three-tiered stack, each coffin contained a small wooden figure with painted black boots and individually crafted clothing. At the time of their discovery, some speculated that they were implements of witchcraft; others suggested they were charms used by sailors to ward off death or even mimic burials for those lost at sea. There is also a provocative theory that the little figures are tributes to the seventeen victims of famed Edinburgh serial killers Burke and Hare, as the figures were found just seven years after Burke’s execution. However, all of the figures are dressed in male attire, whereas twelve of Burke and Hare’s victims were female. Interestingly, some of the figures have arms while others have had theirs removed to fit in their coffins, perhaps suggesting they were not originally made to be buried. Allen Simpson and Samuel Menefee (of the University of Edinburgh and the University of Virginia, respectively) carried out a detailed study of the figures in 1994, and have suggested they were adapted from a set of wooden toy soldiers manufactured around the 1790s, but not re-clothed or buried in the cave until the 1830s. But this is really the extent of knowledge about them. There's a great very well researched article on The Fortean in the Archives site here https://aforteantinthearchives.wordpress.com/2010/01/10/the-miniature-coffins-found-on-arthurs-seat/ It's quite a coincidence that I visited today, as it is only three days away from the first published account of the discover, which appeared in the Scotsman on July 16th 1836, said to be three weeks after the boys found them. If you want to read a very well researched article about the coffins check out the Historian Mike dash's web page below. https://mikedashhistory.com/2010/08/31/the-miniature-coffins-found-on-arthurs-seat/

#Edinburgh#Arthur’s Seat#holyrood park#Scotland#scottish#mystery#National Museum of Scotland#my pics

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Mostly we just harassed KGB guys incessantly,” Rankin recalls, “by taking their parking places, blocking their parked cars, and, if they tried to lose us on the road, boxing them in on the highway, slow-speed, so they couldn’t take the exit they wanted. We once forced Gennady’s fellow KGB officer Alexander Kukhar to drive thirty miles outside Washington when he was trying to get to his apartment in Alexandria. He was a hothead, anyway, always trying to outrun us, which is never done. But after depositing him somewhere south of Quantico, Virginia, he never tried to lose us again. If we couldn’t recruit them, then we just wanted them to give up recruiting us and go home.”

-Best of Enemies: The Last Great Spy Story of the Cold War. Gus Russo and Eric Dezenhall.

is it me or does cold war espionage gives a childish play vibe 😅

CIA v. KGB as you imagined: 007 style combat

CIA v. KGB in real life: "I keyed that Russian's car LOL"

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHEN CASH WAKES UP BEHIND BARS, WILL HE BE OUT IN TIME TO COMPETE? IT’S A RACE TO SAVE THE RANCH IN THE SHOCKING SEASON FINALE OF ‘RIDE’ PREMIERING MAY 28, ON HALLMARK CHANNEL

STUDIO CITY, CA – May 22, 2023 – Cash’s (Beau Mirchoff, “Good Trouble”) day to compete at Cheyenne has arrived, only first he must get out of jail in “Andalusians,” this week’s episode of “Ride” premiering Sunday, May 28 (9 p.m. ET/PT), on Hallmark Channel. Nancy Travis (“Last Man Standing”), Tiera Skovbye (“Riverdale”), Mirchoff, Sara Garcia (“The Flash”), Jake Foy (“Designated Survivor”) and Tyler Jacob Moore (“Shameless”) star.

It's the morning of Cheyenne! Winning the competition could lead to Cash securing the Frontier sponsorship and finally solving the ranch’s growing financial problems. Unfortunately, an altercation with Tucker Clarke (Roger LeBlanc, “Joe Pickett”) has landed Cash in jail. Still reeling from the secrets surrounding the night of Austin’s death and his own guilt, Cash is eager to get out of his cell and into the ring – renewing Isabel (Travis) and Missy’s (Skovbye) fears of history repeating itself. It’s a race against time to save the ranch until one of the McMurrays receives shocking news that could tear the family apart for good.

“Ride” is a Blink49 Studios/Seven24 Films Production. Executive producers are Rebecca Boss, Chris Masi, Sherri Cooper, Alexandra Zarowny, Paolo Barzman, Greg Gugliotta, FJ Denny, John Morayniss, Carolyn Newman, Virginia Rankin, Elana Barry, Josh Adler, Jordy Randall and Tom Cox. Alejandro Alcoba is executive producer. The series is produced by Brian Dennis. Lesley Grant is supervising producer. Paolo Barzman directed from a script by Boss & Masi.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

British "masters of the field" : The disaster at Brandywine

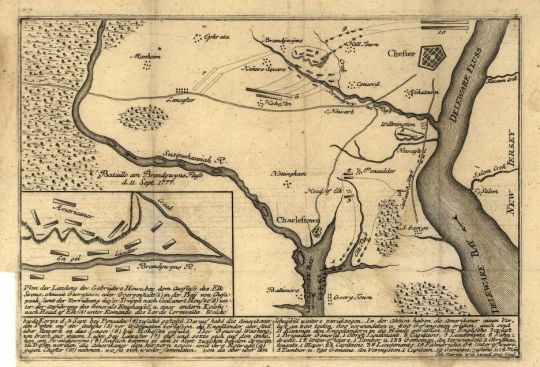

Illustration of the Battle of Brandywine, drawn by cartographer, engraver and illustrator Johann Martin Will (1727-1806) in 1777. Image is courtesy of the Library of Congress.

This post is reprinted from Academia.edu and my History Hermann WordPress blog. It was originally written in September 2016, one day after the anniversary of the battle, when I was a fellow at the Maryland State Archives for the Finding the Maryland 400 project. Enjoy!

On the night of September 10, 1777, many of the soldiers and commanding officers of the Continental Army sat around their campfires and listened to an ominous sermon that would predict the events of the following day. Chaplain Jeremias (or Joab) Trout declared that God was on their side and that

“we have met this evening perhaps for the last time…alike we have endured the cold and hunger, the contumely of the internal foe and the courage of foreign oppression…the sunlight…tomorrow…will glimmer on scenes of blood…Tomorrow morning we will go forth to battle…Many of us may fall tomorrow.” [1]

The following day, the Continentals would be badly defeated by the British and “scenes of blood” would indeed appear on the ground near Brandywine Creek.

In the previous month, a British flotilla consisting of 28 ships, loaded with over 12,000 troops, had sailed up the Chesapeake Bay. [2] They disembarked at the Head of Elk (now Elkton, Maryland) in July, under the command of Sir William Howe, and had one objective: to attack the American capital of Philadelphia. [3] Howe had planned to form a united front with John Burgoyne, but bad communication made this impossible. [4] At the same time, Burgoyne was preoccupied with fighting the Continental Army in Saratoga, where he ultimately surrendered later in the fall. With Howe’s redcoats, light dragoons, grenadiers, and artillerymen were Hessian soldiers fighting for the Crown. [5]

Opposing these forces were two sections of the Continental Army. The first was the main body of Continentals led by George Washington, consisting of light infantry, artillery, ordinary foot-soldiers, and militia from Pennsylvania and Maryland. The second was the Continental right wing commanded by John Sullivan, which consisted of infantry from New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia, and Maryland. The latter was led by William Smallwood and included the First Maryland Regiment. Other Marylanders who participated in the battle included Walter Brooke Cox, Joseph Marbury, Daniel Rankins, Samuel Hamilton, John Toomy, John Brady, and Francis Reveley. While the British were nearby, the 15,000-man Continental Army fortified itself at Chadd’s Ford, sitting on Brandywine Creek in order to defend Philadelphia from British attack. [6]

A map by Johann Martin Will in early 1777, in the same set as the illustration of the battle at the beginning of this post, which shows British and Continental troop movements during the Battle of Brandywine.

The morning of September 11 was warm, still, and quiet in the Continental Army camp on the green and sloping area behind Brandywine Creek. [7] Civilians from surrounding towns who were favoring the Crown, the revolutionary cause, or were neutral watched the events that were about to unfold. [8]

Suddenly, at 8:00, the British, on the other side of the creek, began to bombard the Continental positions facing the creek complimented by Hessians firing their muskets. [9] However, these attacks were never meant as a direct assault on Continental lines. [10] Instead, the British wanted to cross the creek, which had few bridges, including one unguarded bridge called Jeffries’ Ford on Great Valley Road. As Howe engaged in a flanking maneuver, which he had used at the Battle of Brooklyn, the Marylanders would again find themselves on the front lines.

As the British continued their diversionary frontal attack on the Continental lines, thousands of them moved across the unguarded bridge that carried Great Valley Road over Brandywine Creek. Washington received reports about this British movement throughout the day but since these messages were inconsistent, he did not act on them until later. [11] At that point, he sent Sullivan’s wing, including Marylanders, to push back the advancing British flank. [12]

These Marylanders encountered seasoned Hessian troops who, when joined by British guards and grenadiers, attacked the Marylanders. Due to the precise and constant fire from Hessians and a British infantry charge with bayonets, the Marylanders fled in panic. [13] Lieutenant William Beatty of the Second Maryland Regiment, who would perish in the Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill, recounted this attack:

“…[in] the Middle of this Afternoon…a strong Body of the Enemy had Cross’d above our Army and were in full march to out-flank us; this Obliged our Right wing to Change their front…before this could be fully [executed]…the Enemy Appeared and made a very Brisk Attack which put the whole of our Right Wing to flight…this was not done without some Considerable loss on their side, as of the Right wing behaved Gallantly…the Attack was made on the Right, the British…made the fire…on all Quarters.” [14]

As a Marylanders endured a “severe cannonade” from the British, the main body of the Continental Army was in trouble. [15] Joseph Armstrong of Pennsylvania, a private in a Pennsylvania militia unit, described retreating after the British had crossed Brandywine Creek, and moved back even further, at 5:00, for eight or nine miles, with the British in hot pursuit. [16]

Despite the “heavy and well supported fire of small arms and artillery,” the Continentals could not stop the British and Hessian troops, who ultimately pushed the Americans into the nearby woods. [17] The British soldiers, exhausted and wearing wool, were able to push back the Continentals at 5:30 on that hot day. [18] As Washington would admit in his apologetic letter to the President of the Continental Congress, John Hancock, “…in this days engagement we have been obliged to leave the enemy masters of the field.” [19]

As the smoke cleared, the carnage was evident. Numerous Continentals were wounded, along with French military men such as the Marquis de Lafayette. [20] Despite Washington’s claim that “our loss of men is not…very considerable…[and] much less than the enemys,” about 200-300 were killed and 400 taken prisoner. [21] This would confirm Lieutenant Beatty’s claim that Continental losses included eight artillery pieces, “500 men killed, wounded and prisoners.” [22] In contrast, on the British side, fewer than a hundred were killed while as many as 500 were wounded. [23] Beatty’s assessment was that the British loss was “considerable” due to a “great deal of very heavy firing.” [24] Still, as victors, the British slept on the battlefield that night.

Not long after, the British engaged in a feint attack to draw away the Continental Army from Philadelphia and marched into the city without firing a shot, occupying it for the next ten months. [25] In the meantime, Congress fled to York, Pennsylvania, where it stayed until Philadelphia could be re-occupied in late June 1778.

In the months after the battle, the Continental Army chose who would be punished for the defeat. This went beyond John Adams’s response to the news of the battle: “…Is Philadelphia to be lost? If lost, is the cause lost? No–The cause is not lost but may be hurt.” [26] While Washington accepted no blame for the defeat, others were court-martialed. [27]

One man was strongly accused for the defeat: John Sullivan. While some, such as Charles Pickney, praised Sullivan for his “calmness and bravery” during the battle, a sentiment that numerous Maryland officers agreed with, others disagreed. [28] A member of Congress from North Carolina, Thomas Burke, claimed that Sullivan engaged in “evil conduct” leading to misfortune, and that Sullivan was “void of judgment and foresight.” [29] He said this as he attempted to remove Sullivan from his commanding position. Since Sullivan’s division mostly fled the battleground, even as some resisted British advances, and former Quaker Nathaniel Greene led a slow retreat, the blame of Sullivan is not a surprise. [30] Burke’s effort did not succeed since Maryland officers and soldiers admired Sullivan for his aggressive actions and bravery, winning him support. [31]

Another officer accused of misdeeds was a Marylander named William Courts, a veteran of the Battle of Brooklyn. He was accused of “cowardice at the Battle of Brandywine” and for talking to Major Peter Adams of the 7th Maryland Regiment with “impertinent, and abusive language” when Adams questioned Courts’ battlefield conduct. [32] Courts was ultimately acquitted, though he left the Army shortly afterwards. However, his case indicates that the Continental Army was looking for scapegoats for the defeat.

The rest of the remaining Continental Army marched off in the cover of darkness, preventing a battle the following day. They camped at Chester, on the other side of the Schuylkill River, where they stayed throughout late September. [33] Twenty-four days after the battle on the Brandywine, the Continental Army attacked the British camp at Germantown but foggy conditions led to friendly fire, annulling any chance for victory. [34] While it was a defeat, the Battle of Germantown served the revolutionary cause by raising hopes for the United States in the minds of European nobility. [35] It may have also convinced Howe to resign from the British Army, as commander of British forces in North America, later that month.

In the following months, the Continental Army continued to fight around Philadelphia and New Jersey. After the battle at Germantown, the British laid siege to Fort Mifflin on Mud Island for over a month. They also engaged in an intensified siege on Fort Mercer at Red Bank, leading to its surrender in late October. In an attempt to assist Continental forces, a detachment of Maryland volunteers under Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smith were sent to fight in the battle at Fort Mifflin. [36] By November, the Continentals abandoned Fort Mifflin and retired to Valley Forge. Still, this hard-fought defense of the Fort denied the British use of the Delaware River, foiling their plans to further defeat Continental forces.

As the war went on, the First Maryland Regiment would fight in the northern colonies until 1780 in battles at Monmouth (1778) and Stony Point (1779) before moving to the Southern states as part of Greene’s southern campaign. [37] They would come face-to-face with formidable British forces again in battles at Camden (1780), Cowpens (1781), Guilford Courthouse (1781), and Eutaw Springs (1781). In the end, what the Scottish economist Adam Smith wrote in 1776 held true in the Battle of Brandywine and until the end of the war: that Americans would not voluntarily agree with British imperial control and would die to free themselves from such control. [38]

– Burkely Hermann, Maryland Society of the Sons of American Revolution Research Fellow, 2016.

Notes

[1] Collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Vol. 1 (Merrehew & Thompson, 1853), 70-72; Lydia Minturn Post, Personal Recollections of the American Revolution: A Private Journal (ed. Sidney Barclay, New York: Rudd & Carleton, 1859), 207-218; Virginia Biography, Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography Vol. V (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1915), 658. Courtesy of Ancestry.com; George F. Scheer, and Hugh F. Rankin, Rebels and Redcoats: The American Revolution Through the Eyes of Those who Fought and Lived It (New York: De Capo Press, 1957, reprint in 1987), 234. Trout, who was also a Reverend, would not survive the battle. While some records reprint his name as “Joab Traut,” other sources indicate that his first name was actually Jeremias and that his last name is sometimes spelled Trout.

[2] Andrew O’Shaughnessy, The Men Who Lost America: British Command During the Revolutionary War and the Preservation of the Empire (London: One World Publications, 2013), 254; Ferling, 177; Letters from Gen. George Washington, Vol. 5, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_344144_0001, item number 152, p. 87; “A Further Extract from the Examination of Joseph Galloway, Esq; by a Committee of the British House of Commons,” Maryland Journal, December 7, 1779, Baltimore, Vol. VI, issue 324, page 1.

[3] Washington thrown back at Brandywine, Chronicle of America (ed. Daniel Clifton, Mount Kisco, NY: Chronicle Publications, 1988), 163; “The Examination of Joseph Galloway, Esq; before the House of Commons,” Maryland Journal, November 23, 1779, Baltimore, Vol. VI, issue 322, page 1. Joseph Galloway, a former member of the Contintental Congress who later became favorable to the British Crown, claimed that inhabitants supplied the British on the way to Brandywine.

[4] Stanley Weintraub, Iron Tears: America’s Battle for Freedom, Britain’s Quagmire: 1775-1783 (New York: Free Press, 2005), 115.

[5] Bethany Collins, “8 Fast Facts About Hessians,” Journal of the American Revolution, August 19, 2014. Accessed August 31, 2016. They were called Hessians since many of them came from the German state of Hesse-Kassel, and many of them were led by Baron Wilhelm Von Knyphausen.

[6] Chronicle of America, 163; Letters from Gen. George Washington, Vol. 5, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_344144_0001, item number 152, p. 33. Courtesy of Fold3.com; Letters from Gen. George Washington, Vol. 5, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_344144_0001, item number 152, p. 37. Courtesy of Fold3.com; Letters from Gen. George Washington, Vol. 5, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_344144_0001, item number 152, p. 41. Courtesy of Fold3.com; The Annual Register or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature, for the Year 1777 (4th Edition, London: J. Dosley, 1794, 127-8; Mark Andrew Tacyn, “’To the End:’ The First Maryland Regiment and the American Revolution” (PhD diss., University of Maryland College Park, 1999), 137; The Winning of Independence, 1777-1783, American Military History (Washington D.C.: Center for Military History, 1989), 72-73.

[7] John E. Ferling, Setting the World Abaze: Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and the American Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 175-176; O’Shaughnessy, 107. O’Shaughnessy argues that the encampment at Chad’s Ford was an “excellent defensive position.”

[8] Thomas J. McGuire, The Philadelphia Campaign: Brandywine and the Fall of Philadelphia Vol. I (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2006), 172-173. Reportedly, some Quakers ignored the dueling armies and went about their daily business but others such as Joseph Townsend did watch the battle and worried about their fate if the British were to be victorious.

[9] Ferling, 175-176; “Journal of Captain William Beatty 1776-1781,” Maryland Historical Magazine June 1908. Vol. 3, no.2, 109. The British had endured two weeks of horrible weather conditions in their journey from Elkton.

[10] Tacyn, 138; Ferling, 175; O’Shaughnessy, 7, 226, 228.

[11] “II: From Lieutenant Colonel James Ross, 11 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “III: To Colonel Theodorick Bland, 11 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “IV: From Major General John Sullivan, 11 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “V: From Colonel Theodorick Bland, 11 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “VII: Lieutenant Colonel Robert Hanson Harrison to John Hancock, 11 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to John Hancock, 13 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Brigadier General Anthony Wayne, 19 September 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; Scheer, and Rankin, 235.

[12] Tacyn, 138-9; Scheer, and Rankin, 236; McGuire, 184-185, 167, 171, 186, 193, 196, 241.

[13] The Winning of Independence, 1777-1783, American Military History (Washington D.C.: Center for Military History, 1989), 72-73; Tacyn, 139; David Ross, The Hessian Jagerkorps in New York and Pennsylvania, 1776-1777, Journal of the American Revolution, May 14, 2015. Accessed August 31, 2016. The British and Hessians advanced with minimal casualties.

[14] “Journal of Captain William Beatty 1776-1781,” 109-110; Muster Rolls and Other Records of Service of Maryland Troops in the American Revolution Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 18, 189, 310, 344, 345, 363, 379, 388, 519. William Beatty would become a captain in April 1778 in the Seventh Maryland Regiment, then in the First Maryland Regiment in early 1781.

[15] Letters from Gen. George Washington, Vol. 5, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_344144_0001, item number 152, p. 49. Courtesy of Fold3.com.

[16] Pension of Jacob Armstrong, Revolutionary War Pensions, National Archives, NARA M804, Record Group 15, pension number S.22090, roll 0075. Courtesy of Fold3.com; “VII: Lieutenant Colonel Robert Hanson Harrison to John Hancock, 11 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016. Jacob served as a substitute for his father, Simon Armstrong.

[17] The Annual Register, 128-129.

[18] Ferling, 176.

[19] Weintraub, 118; “VIII: To John Hancock, 11 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; Letters from Gen. George Washington, Vol. 5, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_344144_0001, item number 152, p. 53-53a; “VIII: To John Hancock, 11 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016. This letter was published by order of Congress.

[20] Tacyn, 140; The Annual Register, 129-130; Letters from Gen. George Washington, Vol. 5, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_344144_0001, item number 152, p. 53-53a; “VIII: To John Hancock, 11 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; Letters from Gen. George Washington, Vol. 5, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_344144_0001, item number 152, p. 287. Courtesy of Fold3.com; “To George Washington from Brigadier General William Woodford, 2 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, 1781-1784 Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 48, 458; Scheer, and Rankin, 240.

[21] Ferling, 177; O’Shaughnessy, 109; Washington thrown back at Brandywine, Chronicle of America, 163; Letters from Gen. George Washington, Vol. 5, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_344144_0001, item number 152, p. 53-53a; “VIII: To John Hancock, 11 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; Petitions Address to Congress, 1775-189, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_419789_0001, item number 42, p. 159. Courtesy of Fold3.com; Pension of Jacob Ritter (prisoner after battle), Revolutionary War Pensions, National Archives, NARA M804, Record Group 15, pension number S.9080, roll 2052. Courtesy of Fold3.com; John Dwight Kilbourne, A Short History of the Maryland Line in the Continental Army (Baltimore: Society of Cincinnati of Maryland, 1992), 14; Howard H. Peckham, The War for Independence: A Military History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), 68-70; Scheer, and Rankin, 239. Washington’s letter was later published by order of Congress.

[22] “Journal of Captain William Beatty 1776-1781,” 110.

[23] O’Shaughnessy, 109; The Annual Register, 129-130; “To George Washington from Major John Clark, Jr., 12 November 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; Peckham, 70; Scheer, and Rankin, 239.

[24] “Journal of Captain William Beatty 1776-1781,” 110; Peckham, 70; McGuire, 209. Claims by Continentals that there were many British casualties may have been explained by British tactics.

[25] “A Further Extract from the Examination of Joseph Galloway, Esq; by a Committee of the British House of Commons”; “The Examination of Joseph Galloway, Esq; before the House of Commons”; Weintraub, 115; Tacyn, 143; Trevelyan, 249, 275; O’Shaughnessy, 110.

[26] John Adams diary 28, 6 February – 21 November 1777 [electronic edition], entries for September 16, Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society

[27] “A Further Extract from the Examination of Joseph Galloway, Esq; by a Committee of the British House of Commons” ; “General Orders, 19 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “General Orders, 25 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “General Orders, 3 January 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[28] Tacyn, 142; Letters from General Officers, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_4345518_0001, item number 100, p. 69. Courtesy of Fold3.com.

[29] Tacyn, 141.

[30] Tacyn, 140-141.

[31] Tacyn, 143.

[32] “General Orders, 19 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[33] Pension of Jacob Armstrong; Weintraub, 116-117; O’Shaughnessy, 109; “Journal of Captain William Beatty 1776-1781,” 110; Kilbourne, 14.

[34] Pension of Jacob Armstrong; The Annual Register, 129-130; Sir George Otto Trevelyan, The American Revolution: Saratoga and Brandywine, Valley Forge, England and France at War, Vol. 4 (London: Longmans Greens Co., 1920), 275; O’Shaughnessy, 110; Ross, “The Hessian Jagerkorps in New York and Pennsylvania, 1776-1777,” Journal of the American Revolution, May 14, 2015. Accessed August 31, 2016; “Journal of Captain William Beatty 1776-1781,” 110-111; Kilbourne, 17, 19. As Beatty recounts, Marylanders were joined by the Maryland militia and were still part of General Sullivan’s division.

[35] Trevelyan, 249; O’Shaughnessy, 111; Christopher Hibbert, George III: A Personal History (New York: Basic Books, 1998), 154-155.

[36] “Journal of Captain William Beatty 1776-1781,” 110; Kilbourne, 14.

[37] Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, April 1, 1778 through October 26, 1779 Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 21, 118; Kilbourne, 21-22, 24-27, 29-30, 31, 33.

[38] Adam Smith, Chapter VII: Of Colonies, Part Third: Of the advantages which Europe has derived from the Discovery of America, and from that of a passage to the East Indies by the Cape of Good Hope, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (ed. Edward Canman, New York: The Modern Library, reprint 1937, originally printed in 1776), 587- 588.

#battle of brandywine#american revolution#revolutionary war#battles#military history#british victory#continental army#us history#18th century#muskets

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

William B. Hartgrove, Jr. (November 1877 - June 1918) one of the founders of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History was born in DC to William B. Hartgrove, Sr. and Rebecca Perry Hartgrove, former enslaved. He studied at Howard University. He and his brother, Robert Sinclair Hartgrove, shared a house in DC. A graduate of Amherst College, he became a lawyer. He was teaching at Armstrong Manual Training School, one of the only two high schools in the District accepting African American students. His annual salary was about $650 but there were times when his only income came from lecturing about African American history.

He befriended Carter Godwin Woodson, who was teaching at M Street High School. Woodson admired his intellectual and leadership abilities and began mentoring him. They shared in common a passion for African American history and would often walk together to the Library of Congress when Woodson was working on his doctoral dissertation.

In 1915, Woodson asked him to become, with him, one of the five founders of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, renamed the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, when the organization was launched in Chicago. The Association became the first organization dedicated to the study of Black history.

The author of many articles and annotated bibliographies of African American works, including the popular The Negro Soldier in the American Revolution, published in 1916, Hartgrove also wrote “The Story of Maria Louise Moore and Fannie M. Richards” which highlighted the accomplished of free Black women of Virginia. This important early account of the history of Black women was published in the first volume of The Journal of Negro History, Volume I.

He often lectured on the achievements of Blacks at the institution’s Rankin Chapel, especially the role of Black soldiers fighting on behalf of the country.

In 1918, his last publication, “The Story of Josiah Henson” was completed by Dr. Woodson because of his illness. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

1 note

·

View note

Text

Beavoir Gets New Signs (MS)

(Thank You so much for your efforts, gentlemen! – DD) Help Spread Mockingbird Non-Compliant News! Like, Share, Re-Post, and Subscribe! There’s a lot more to see at our main page, Dixie Drudge! Beauvoir, The Jefferson Davis Home and Presidential Library (The Virginia Flaggers) – As many know the signs at Beauvoir have been needing to be replaced for quite some time. Taking the initiative Rankin…

0 notes

Text

Canadian procedural Wild Cards is coming back for a second season on The CW.

The renewal news came this morning as originating broadcaster CBC renewed the show and unveiled it at its Upfronts.

It marks a bit of good news for The CW, which canceled Walker earlier this week, while Canadian drama The Spencer Sisters, which it also aired, was canceled at CTV.

The show, stars Grey’s Anatomy’s Giacomo Gianniotti, Riverdale’s Vanessa Morgan and Jason Priestley, has been one of The CW’s stronger performers over the last year.

Earlier this month, The CW’s President of Entertainment Brad Schwartz told Deadline that he was keen to bring back the show for more episodes.

Wild Cards is a crime-solving procedural with a comedic twist that follows the unlikely duo of a gruff, sardonic cop and a spirited, clever con woman. Ellis (Gianniotti) plays a demoted detective who has spent the last year on the maritime unit, while Max (Morgan) has been living a transient life elaborately scamming everyone she meets. But when Max gets arrested and ends up helping Ellis solve a local crime, the two are offered the opportunity to redeem themselves, with Ellis going back to detective and Max staying out of jail. The catch? They have to work together, with each using their unique skills to solve crimes. Terry Chen and Karin Konoval also star.

It is produced by Blink49 Studios, Front Street Pictures and Piller/Segan with Michael Konyves as showrunner. He exec produces alongside Shawn Piller, James Genn, Lloyd Segan, Alexandra Zarowny and James Thorpe. Produced by Charles Cooper and Virginia Rankin, it is distributed internationally by Fifth Season.

The second season will premiere in winter 2025 on both The CW and CBC and consists of 13 episodes.

“We are thrilled to order a second season of The CW’s breakout series Wild Cards,” said Liz Wise Lyall, Head of Scripted Programming, The CW Network. “Wild Cards has clearly captured the imagination of our viewers thanks to exhilarating storytelling and the crackling chemistry between Vanessa and Giacomo. We are confident Wild Cards is the kind of smart and sexy blue-sky drama that could continually build its audience for years.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gov. Youngkin signs a measure backed by abortion-rights groups but vetoes others

By SARAH RANKIN Updated [hour]:[minute] [AMPM] [timezone], [monthFull] [day], [year] RICHMOND, Va. (AP) — Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin signed 88 bills Friday and vetoed 11 others, including legislation that advocates said would have helped protect women and medical practitioners from potential extraditions related to abortion services that are legal in Virginia. Youngkin said in a statement…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

#rick goldschmidt#rankin/bass#tadahito mochinaga#rankin/bass historian#rankin bass#studio m.o.m.#m.o.m. studios#animagic#stopmotion#japan#anime#stop motion anime

1 note

·

View note

Text

VIRGINIA MAESTRO..que prefieres UN JAIRO ZAVALA alias DE PEDRO cantando o chupando y lamiendo, HONEY de EL PRESIDENTE grupo escoces q formo el bajista y actual cantante de GUN a cuyo escenario en sala UNIVERSAL SUR me subí cuando tomo el micro en vez de Mark RANKIN [al q llevaron EN VOLANDAS a la barra a por una BOTELLA ] para cantar SMELL LIKE TEEN SPIRIT de cd NEVERMIND de nIrVANa y cerrar el concierto para ser televisados el día siguiente x CANAL+ en la plaza SONY de la EXPO UNIVERSAL DE SEVILLA'92=27_6_92

Por cierto DE PEDRO toco con NIKKI LANE en el jardin botanico de ALFONSO XIII en junio 2023 como tu hiciste en 2016 en el TEATRO DEL ARTE cuando a su guitarrista español ALEX MUÑOZ tuvo q ser operado de URGENCIA de un CANCER con 26 años

youtube

0 notes

Text

Attacks against African-American churches in the United States have taken the form of arson, bombings, mass murder, hate crimes, and white supremacist-propelled domestic terrorism. This timeline documents acts of violence against churches with predominantly black leadership and congregations.

19th century

1822 Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina was burned down.[1]

20th century

1921 May 31 Black Wall Street Church, Bombed, Tulsa Oklahoma

1951–1960

1955 October 5 Burning of St. James AME Church, Lake City, South Carolina

1956 December 25 Bethel Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, was bombed.

1957 April 28 At Allen Temple African Methodist Episcopal Church in Bessemer, Alabama, dynamite exploded at the rear of the church during an evening service.

1958 June 29 Bethel Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, was bombed again. This time, guards removed the bombs to a ditch; the blast blew out the windows, however.[2]

1961–1970

1962 January 16 New Bethel Baptist Church, St Luke's African Methodist Episcopal Church, and Triumph Church Kingdom of God and Christ, all three in Birmingham, Alabama, were fire-bombed.

1962 September 25 St. Matthew's Baptist Church of Macon, Georgia, was burned. "It is the fifth church to burn in a month."[3][4]

1962 December 14 At Bethel Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, a third bomb blew out the church windows.

1963 August 10 St. James United Methodist Church of Birmingham, Alabama, was destroyed by a "gasoline fire bomb."[2]

1963 September 15 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, was bombed during a Sunday church service. Twenty-two people were injured and four girls died.

1964 June 16 Mount Zion Methodist Church in Longdale, Mississippi, was burned to the ground. An investigation by Mississippi civil rights workers led to the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner.

1964 July 30 Mount Moriah Baptist Church near Meridian, Mississippi was leveled by fire. This attack is connected to countless others that were meant to intimidate Black residents who were active in the Civil rights movement.[5]

1964 July 31 Pleasant Grove Missionary Baptist Church in Rankin County, Mississippi, 15 miles east of Jackson, was burned shortly before midnight. At least 15 churches were damaged or destroyed by lire between the statewide civil rights drive opening in mid-June and this day.[5]

1971–1980

1972 (exact date unknown) Cartersville Baptist Church, in Reston, Virginia, was burned, causing the main church to fall into the basement.[6][7]

1974 June 30 At Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia, Alberta Williams King, mother of Martin Luther King Jr., and Edward Boykin were killed by a man who had determined that "black ministers were a menace to black people." A third churchgoer was wounded.

1977 December 18 Zoah Methodist Church, Mulberry Baptist in Wilkes County, Georgia; Mt. Zion Baptist Church and Antioch CME in Lincoln County, Georgia. Three teens were found guilty in the burning of 4 black churches in Wilkes and Lincoln counties.

1979 December 16 Second Wilson Church of Chester, South Carolina, a meeting place for civil rights activists, was gutted by fire.

1981–1990

1991–2000

More than 30 black churches were burned in an 18-month period in 1995 and 1996, leading Congress to pass the Church Arson Prevention Act.[7]

1993 April 5 Rocky Point Missionary Baptist Church in Pike County, Mississippi, was set on fire by three teenagers who served time.[8]

1995 January 13 Johnson Grove Baptist Church in Bells, Tennessee, was burned.

1995 January 13 Macedonia Baptist Church in Denmark, Tennessee, was burned.

1995 January 31 Mount Calvary Baptist Church in Hardeman County, Tennessee, was burned.

1995 June 21 Outside of Manning, South Carolina, four men affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan worked together to burn down Macedonia Baptist Church and Mt. Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church of Greeleyville, both majority black churches. Criminal convictions were obtained. In a 1998 civil suit, Grand Dragon Horace King and four other Klansmen, together with Klan organisations, were sued for $37.8 million for their roles, and amount reduced on appeal.[9][10]

1995 August 15 St. John Baptist Church in Lexington County, South Carolina, was burned and an arrest was made.

1995 October 31 Mount Pisgah Baptist Church of Raeford, North Carolina, was burned.

1995 December 22 Mount Zion Baptist Church of Boligee, Alabama, was burned.

1995 December 30 Salem Baptist Church in Gibson County, Tennessee, was burned.

1996 January 6 Ohovah African Methodist Episcopal Church of Orrum, North Carolina, was burned and an arrest was made.

1996 January 8 Inner City Church of Knoxville, Tennessee, was burned.

1996 January 11 Little Zion Baptist Church and Mount Zoar Baptist Church of Green County, Alabama, were both burned on the same day.

1996 February 1 Cypress Grove Baptist Church, St. Paul's Free Baptist Church, and Thomas Chapel Benevolent Society of East Baton Rouge, Louisiana, were all burned on the same day.

1996 February 1 Sweet Home Baptist Church in Baker, Louisiana, was burned.

1996 February 21 Glorious Church of God in Christ of Richmond, Virginia, was burned.

1996 February 28 New Liberty Baptist Church in Tyler, Alabama, was burned and an arrest was made.

1996 March 5 St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church in Hatley, Mississippi, was burned.

1996 March 20 New Mount Zion Baptist Church in Ruleville, Mississippi, was burned.

1996 March 27 Gay's Hill Baptist Church of Millen, Georgia, was burned.

1996 March 30 El Bethel Missionary Baptist Church of Satartia, Mississippi, was burned and an arrest was made.

1996 March 31 Butler Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church of Orangeburg, South Carolina, was burned.[11]

1996 April 11 St. Charles Baptist Church in Paincourtville, Louisiana, was burned.

1996 April 13 Rosemary Baptist Church in Barnwell, South Carolina, was burned.

1996 April 26 Effingham Baptist Church in Effingham, South Carolina, was burned.

1996 May 14 Mount Pleasant Baptist Church in Tigrett, Tennessee, was burned.

1996 May 23 Mount Tabor Baptist Church in Cerro Gordo, North Carolina, was burned.

1996 May 24 Pleasant Hill Baptist Church in Lumberton, North Carolina, was burned.

1996 June 3 Rising Star Baptist Church in Greensboro, Alabama, was burned.

1996 June 7 Matthews Murkland Presbyterian Church sanctuary in Charlotte, North Carolina, was burned and an arrest was made.

1996 June 9 New Light House of Prayer and The Church of the Living God, both of Greenville, Texas, were burned on the same day.

1996 June 12 Evangelist Temple on Marianna, Florida, was burned.

1996 June 13 First Missionary Baptist Church of Enid, Oklahoma, was burned and an arrest was made.

1996 June 17 Hills Chapel Baptist Church, Rocky Point, North Carolina, is burned.

1996 June 17 Mount Pleasant Missionary Baptist Church and Central Grove Missionary Baptist Church, both of Kossuth, Mississippi, were burned on the same day.

1996 June 20 Immanuel Christian Fellowship of Portland, Oregon, was burned.

1996 June 24 New Birth Temple Church of Shreveport, Louisiana, was burned.

21st century

2001–2010

2006 July 11 A cross was burned outside a predominantly black church in Richmond, Virginia[12]

2008 November 5 Macedonia Church of God in Christ, in Springfield, Massachusetts, was burned down and an arrest was made.[13]

2010 December 28 In Crane, Texas, the Faith in Christ Church was vandalized with "racist and threatening graffiti" and then firebombed by a man who was attempting to gain entry into the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas; an arrest was made and the perpetrator was found guilty and sentenced to 37 years in prison.[14]

2011–present

2014 November 24 The Flood Christian Church in Ferguson, Missouri, was burned by arsonists during a series of protests over the police shooting of Michael Brown, Jr. Michael Brown Sr. had been baptized at the church a week before the fire.[15] While other buildings in Ferguson were burned that night, the church was some distance from the protests, and buildings nearby were not damaged; investigators also found signs of forced entry at the church.[16] Members of the congregation believed it had been a targeted attack, motivated by Pastor Carlton Lee's calls for Officer Darren Wilson's arrest and his participation in Al Sharpton's National Action Network.[15][17] Pastor Lee died of an apparent heart attack in 2017, at the age of 34.[18]

2015 June 17 At Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, 10 African Americans, including Clementa C. Pinckney, member of the South Carolina Senate, were shot in a mass attack; nine were killed. White supremacist and neo-Nazi Dylann Roof pled guilty to murder and was sentenced to nine consecutive life sentences without parole.

2015 June 22 At College Hill Seventh Day Adventist, in Knoxville, Tennessee, a small fire was set, resulting in minimal damage to the church structure and destruction of the church van. The act was not classified as a hate crime.[19]

2015 June 23 God's Power Church of Christ in Macon, Georgia, was gutted by a fire which was ruled arson.[20][21]

2015 June 24 At Briar Creek Baptist Church in Charlotte, North Carolina, an unknown arsonist started a three-alarm fire, causing more than $250,000 in damages.[22]

2016 November 1 The 111-year-old Hopewell Missionary Baptist Church in Greenville, Mississippi, was burned and vandalized with the words "Vote Trump" spray-painted onto the building. The arsonist, a black man who was a member of the church, pled guilty in March 2019.[23][24][25]

2019 March 26 St. Mary Baptist Church in Port Barre, Louisiana. This was the first in a series of three historically black churches over 100 years old, burned within a span of 10 days. Holden Matthews, 21, the son of a St. Landry Parish sheriff's deputy, was charged with the arson attack.[26][27][28] Matthews reportedly was not motivated by race but rather by anti-Christian animus and a desire to promote himself as a black metal musician in the mold of Varg Vikernes, who committed a similar series of church burnings in 1990s Norway.[29] On November 2, 2020, Matthews was sentenced to 25 years in prison and ordered to pay the churches $2.6 million.[30]

2019 April 2 Greater Union Baptist Church in Opelousas, Louisiana. Holden Matthews was charged with the arson attack.[26][27][28]

2019 April 4 Mount Pleasant Baptist Church in Opelousas, Louisiana. Holden Matthews was charged with the arson attack.[26][27][28]

2022 November 8 Two churches, Greater Bethlehem Temple Church and Epiphany Church, in Jackson, Mississippi were burned overnight. Both fires, in addition to 5 others set the same night, were deemed the work of an arsonist.[31][32]

#List of attacks against African-American churches#Black Churches#white supremacy#white hate in america

0 notes