#VGKC Autoimmune Encephalitis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

症例報告:COVID-19関連自己免疫性脳炎の1例におけるステロイド大量投与とIVIGによる治療成功:文献的考察

自己免疫性脳炎はまれであるが、COVID-19の重大な合併症である。COVID-19関連自己免疫性脳炎の管理には、ステロイド、免疫グロブリン静注(IVIG)、プラズマフェレーシス、モノクローナル抗体療法などが用いられる。この研究では、副腎皮質ステロイドとIVIG療法の開始後に急速に回復した重症COVID-19自己免疫性脳炎患者を紹介した。本研究では、COVID-19関連自己免疫性脳炎の病態生理学的機序、診断、管理に関する最新の文献を概説した。

本報告は、IVIG療法後に改善した重症のCOVID-19関連自己免疫性脳炎の症例である。脳炎はCOVID-19患者では比較的死亡率の高いまれな合併症である。罹患者では呼吸器症状は軽度であるか、あるいは消失することもある。精神状態の変化、運動障害および痙攣が、COVID-19関連自己免疫性脳炎患者における神経症状の主な領域である。他のタイプの自己免疫性脳炎と同様に、免疫療法は有望な臨��結果を示している。

COVID-19では神経学的合併症の3つの病態生理学的機序、すなわち脳炎が考えられる:

最初の、そして最も受け入れられているメカニズムは、COVID-19によって引き起こされる分子模倣である。この説では、活性化された宿主抗体が自己抗原を同定し、様々なシステムを攻撃する。COVID-19関連自己免疫性脳炎患者には、抗ニューロナル抗体、抗グルタミン酸デカルボキシラーゼ抗体、抗CASPR2抗体、抗ミエリンオリゴデンドロサイト糖蛋白など、いくつかの一般的な抗ニューロナル自己抗体が認められる。この病態生理学的メカニズムは、自己免疫性肝炎、ギラン・バレー症候群、脊髄炎、急性散在性脳脊髄炎、まれに自己免疫性副腎炎など、COVID-19に関連する他の自己免疫疾患も説明できる。

第二に、腫瘍壊死因子α、インターロイキン(IL)-1、IL-6などの炎症性サイトカインが過剰に産生されることによるサイトカインストームもメカニズムの一つである。総説によると、末梢循環系におけるサイトカインが神経血管内皮を障害し、血液脳関門(BBB)の透過性を高めるという経路も考えられる。サイトカインストームが起こると、炎症亢進状態が形成され、脳組織の損傷や脳炎を引き起こす。髄液分析やDダイマー、C反応性蛋白などの血清学的検査は、このメカニズムの証拠となる。自己免疫性脳炎の脳波パターンでは、全身性の炎症を示すびまん性徐波を示すことがある。炎症反応に関与するいくつかのバイオマーカーが、疾患の重症度や全予後と関連する可能性があることは言及に値する。Rizziらは、IFN-γ-induced protein 10 (IP-10)とCRPが重症COVID-19患者の予後マーカーになりうると報告している。Tonelloらによって報告された別の研究では、オステオポンチン(OPN)がCOVID-19の重症度を層別化する有望なバイオマーカーになりうることがわかった。

第三に、中枢神経系へのウイルスの直接浸潤が起こる。ウイルスが直接侵入する主な経路には、血行性伝播と経神経逆行性経路の2つがある。血行性伝播では、ウイルスはBBBを通過し、ウイルスのスパイクタンパク質が上皮細胞のアンジオテンシン変換酵素II受容体に結合することで脳組織に侵入する。SARS-CoVはまた、白血球などの異なる骨髄系細胞に感染し、中枢神経系を含む異なる組織に播種する可能性がある。神経を通過する逆行性経路では、ウイルスは嗅覚ニューロンに侵入し、軸索の逆行性輸送を利用して篩状板を越え、CNSに侵入する。この経路は、COVID-19の最も一般的な症状の一つである無嗅覚症の発生に重要な役割��果たしている可能性がある。

上述した3つのメカニズムによれば、自己免疫性脳炎は髄液に自己抗体がなくても発症する可能性がある。したがって、臨床医は自己抗体が陰性であっても自己免疫性脳炎を除外すべきではない。COVID-19の活動性感染の臨床的・検査的証拠を認めなかった本症例では、自己免疫性脳炎の自己抗体も陰性であった。しかし、COVID-19関連自己免疫性脳炎の治療については、症例数が限られているため、確立されたガイドラインはまだ普及していない。

しかし、高用量の副腎皮質ステロイドと免疫グロブリンの静脈内投与が最も広く用いられている治療法である。2020年、Pilottoらは、60歳の自己抗体陰性脳炎の男性に、副腎皮質ステロイド(メチルプレドニゾロン1g/日)を5日間大量静脈内投与した症例を報告した。ステロイド点滴の1サイクル目終了後、患者の意識は改善(運動性緘黙から覚醒)し、神経学的検査も正常で退院した。本報告では,IVIGの投与により改善した重症のCOVID-19関連自己免疫性脳炎の1例を紹介する.脳炎はCOVID-19患者では比較的死亡率の高いまれな合併症である。呼吸器症状は軽度であるか、あるいは消失することもある。COVID-19関連自己免疫性脳炎患者における神経症状の主な領域は、精神状態の変化、運動障害および痙攣である。他のタイプの自己免疫性脳炎と同様に、免疫療法は有望な臨床結果を示している。

また、COVID-19に関連した抗VGKC辺縁系脳炎で、副腎皮質ステロイドの投与により回復した症例も報告されている。この症例は67歳の女性で、三半規管性運動失調、運動性失語症、認知障害を含む中枢神経症状を有していた。彼女はデキサメタゾンの静脈内投与を開始した後、徐々に改善し、最終的にはほぼ完全に回復して退院した。この論文はまた、コルチコステロイドを第一選択薬とし、診断後すぐに開始することを推奨している。

プラズマフェレーシスも有効であると報告された。2020年、DoganらはCOVID-19関連自己免疫性脳炎におけるプラズマフェレーシスの効果を記述した最初のケースシリーズを行った。この研究では、COVID-19関連自己免疫性脳炎の6症例がアルブミンによるプラズマフェレーシスを受け、ICUで経過中の臨床状態、検査データ(特に血清フェリチン値)、脳MRIが記録された。患者のうち1人は臨床状態が悪化したが、他の患者は1~3サイクルのプラズマフェレーシス後に意識を回復し、抜管することができた。検査データ(特に血清フェリチン値)と脳MRIからも脳炎の退縮が示唆された。

同年、Caoらは、メチルプレドニゾロン1g/日を5-10日間静脈内投与し、血漿交換を行った5人の患者のケースシリーズを行った。3人の患者は、1週間以内に意識が改善し、劇的な神経学的改善を示した。リツキシマブなどのモノクローナル抗体も治療の選択肢になりうる。症例報告ではリツキシマブの有効性が証明されている。重篤な神経症状を呈した患者の1人は、全身痙攣と幻覚を呈し、リツキシマブ投与後に徐々に改善した。言及された論文の要約と治療法選択の結論を表3に簡単に示す。

この症例報告は、COVID-19関連自己抗体陰性自己免疫性脳炎の管理における副腎皮質ステロイドとIVIGの併用療法の有効性を強調するものである。これまでの報告では、COVID-19関連自己免疫性脳炎におけるIVIGまたはコルチコステロイド治療の成功が報告されている。しかし、IVIGと副腎皮質ステロイドを併用することの有効性と安全性に関する臨床的証拠はまだ限られている。今回の症例では、併用療法後に良���な転帰が得られた。結論として、高用量ステロイドとIVIGの併用に関するデータは限られており、ガイドラインもないにもかかわらず、この治療法はCOVID-19関連自己免疫性脳炎患者にとって有益である可能性がある。その結果、IVIGと高用量コルチコステロイドの併用療法は、自己免疫性脳炎と診断された患者、特にCOVID-19を合併している患者にとって有益である可能性がある。

自己免疫性脳炎の診断と治療

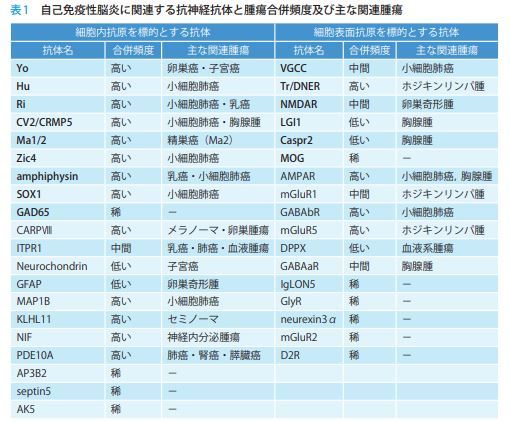

自己免疫性脳炎は,自己免疫学的機序を介し,髄膜・脳・脊髄が障害される中枢神経疾患である.急性・亜急性に進行する意識障害,精 神症状,認知機能障害,痙攣発作,運動異常症等多彩な神経症状を呈する.時に傍腫瘍性に発症することがあり,神経症状が腫瘍の発見に先立 つ こ と も 稀 で は な い. 頭 部MRI(magnetic resonance imaging)検査や脳脊髄液検査に異常を認めないこともあり,診断に難渋することも多い.

みんなの脳神経内科

@user-vp3fz8vv9c

youtube

0 notes

Photo

For Lek

#thai tattoo#brain tattoo#inner arm tattoo#forarmtattoo#thai#thai writing#tattoo#arm tattoo#mine#personal#me#encephalitis#Encephalitis awareness#VGKC Autoimmune Encephalitis#autoimmune disease

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Background: Autoimmune encephalitis was very rare prior to the current pandemic. A sharp rise in cases has been observed from March to August of 2022 in Los Angeles. Such an increase, especially with certain types of antibodies, may point toward the possibility of post-infectious autoimmune encephalitis. While review articles on autoimmune encephalitis during this pandemic have been published, a sharp rise in one geographic area within a short period of time has not been documented yet.

Aims: To report an alarming increase in autoimmune encephalitis with mostly positive glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) and/or voltage-gated potassium channel (VGKC) antibodies over six months during 2022 in Downtown Los Angeles.

Material and methods: This is an observational case series from one neurocritical care practice in Downtown Los Angeles. Autoimmune encephalitis antibody panels were sent to patients with altered mental status or neurologic deficits of unclear etiology from March to August of 2022.

Results: Of the 29 patients tested, 12 reports came back positive. Ten had positive GAD and/or VGKC antibodies, one had a positive myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody, and one had a positive leucine-rich glioma-inactivated 1 protein antibody; a 41% positive rate.

Conclusions: This observation has important implications: (1) We may be entering an era of heightened autoimmune encephalitis. (2) These occurrences may be post-infectious in nature at this point of the pandemic. (3) Mostly GAD and VGKC antibodies have been identified (10 of them), which may point toward a new direction of research from a molecular mimicry standpoint. (4) To benefit patients, clinicians need to be aware of such disease manifestations and increase testing; resources must be increased to improve test availability and shorten turnaround time; and treatment, which is expansive, must be made widely available for these potentially reversible diseases.

0 notes

Text

Clinical Reasoning: Rapid progression of reversible cognitive impairment in an 80-year-old man

Clinical Reasoning: Rapid progression of reversible cognitive impairment in an 80-year-old man Walid Bouthour, Lukas Sveikata, Maria Isabel Vargas, Johannes Alexander Lobrinus, Emmanuel Carrera Neurology Dec 2018, 91 (24) 1109-1113; DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006647

Neurologyの研修医とフェロー向けの症例検討です.

今回は良く遭遇する高齢者の進行する意識障害!

Summary

高齢者の急速に進行する意識障害で,MRIで白質病変とMicro bleeds (MBs)がある症例では炎症性脳アミロイド血管炎(inflammatory cerebral amyloid angiopathy; CAA-I)���考慮する

CAA-Iの診断基準

(1) age >40 years

(2) clinical symptoms, such as headaches or cognitive disturbances, not directly attributable to intracerebral hemorrhage

(3) asymmetric WMD patterns that extend to the immediately subcortical area

(4) presence of cortico–subcortical hemorrhagic lesions

脳の生検は診断に有用

Lesson for clinical setting

高齢者のよくわからない意識障害は遭遇します.MBsと白質病変があれば,CAA-Iも鑑別疾患に挙げるべきだと学びました.

Section 1

An 80-year-old right-handed man was accompanied by his wife to the neurology clinic for difficulties in performing activities of daily living. He was reported to struggle using cutlery and remembering how to dial a phone number. His wife had noticed changes in his speech, which had become incomprehensible. Symptom onset was insidious, with progressive worsening over a couple of weeks. The patient himself had no complaint. His medical history included an episode of transient vertical diplopia 2 months prior to admission, diagnosed as a TIA in the midbrain. Brain MRI at the time of TIA showed no acute lesion but moderate vascular white matter disease (WMD), related to arterial hypertension and type II diabetes, and 11 lobar microbleeds (bilateral temporal, parietal, and frontal). Neurologic examination at the time of the current admission revealed right homonymous hemianopia, production of jargon and impaired comprehension suggestive of Wernicke aphasia, ideational apraxia, executive dysfunction, and anosognosia. The rest of the physical examination was normal. Episodes of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation were detected during the patient’s hospital stay. Questions for consideration:

1. Can you relate the clinical picture to a single lesion? 2. What is your differential diagnosis at this stage? GO TO SECTION 2 Section 2

Both Wernicke aphasia and ideational apraxia suggest a dysfunction in the left posterior hemisphere; more specifically in temporoparietal associative cortices for the Wernicke aphasia and in the supramarginal gyrus for ideational apraxia. Right homonymous hemianopia indicates involvement of the left visual pathways. Although executive functions are widely distributed throughout the brain, executive dysfunction is classically associated with pathologies of prefrontal brain regions. Anosognosia is the result of a lesion in the right temporoparietal lobe. The symptoms and signs suggest widespread bihemispheric dysfunction predominantly affecting the posterior part of the left hemisphere. In our patient, the rapidly progressive evolution of cognitive decline points towards several etiologies including vascular, infectious, and inflammatory processes.1 Vascular causes should be considered because of the history of chronic arterial hypertension, possible TIA, and WMD. However, the absence of an acute or stepwise evolution does not favor a vascular etiology. Among infectious causes, herpes simplex virus encephalitis was ruled out because of the subacute evolution of the disease and the absence of fever or seizures. Neurosyphilis and HIV dementia have a more indolent evolution, and the patient had no sexual risk factors. There was no tick bite or erythema migrans history to support Lyme disease. Voltage-gated potassium channel (VGKC), NMDA receptor, and other antibody-related autoimmune encephalitis are frequently associated with myoclonus or seizures. Paraneoplastic autoimmune encephalitis may also cause rapidly progressive cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Other inflammatory causes include cerebral vasculitis, which could present with subacute cognitive impairment. Inflammatory cerebral amyloid angiopathy is a rare and newly recognized entity that may cause subacute dementia in predominantly older patients. Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease can present with rapid cognitive decline, sometimes associated with visual field defects, myoclonus, or seizures. In the absence of preexisting cognitive decline reported by the family, Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal disease were considered less likely. As for tumor-related pathologies, lymphoma typically presents with progressive cognitive decline, and brain metastases can cause rapidly progressive cognitive symptoms. Question for consideration:

1. Which ancillary tests would you perform to make the diagnosis? GO TO SECTION 3 Section 3

Brain MRI, FSE T2-weighted sequence, showed bilateral and asymmetric cortical and subcortical hyperintense lesions in the left parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes with a discrete mass effect on adjacent structures (figure 1). Axial T2*-weighted images showed the same lobar microbleeds as described previously. There was no superficial hemosiderosis or signs of past intracerebral hemorrhage. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted sequence showed no parenchymal or meningeal enhancement. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy revealed a decrease of the N-acetylaspartate/choline ratio, but no characteristic pattern of brain tumor. Figure 1 Brain MRI slices before admission, upon admission, and during follow-up (A) No lesion on axial fast spin echo (FSE) T2-weighted imaging sequence after the transient focal episode, 2 months prior to admission. (B) Axial FSE-T2 MRI upon admission shows high signal on both parieto-occipital lobes (arrows) and (C) axial T2*-weighted sequence shows several lobar microbleeds (arrows). (D) Axial, gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted sequence shows no enhancement. (E) A small frontal cortico-subcortical ischemic lesion is revealed by diffusion-weighted imaging (arrow) on a follow-up MRI 4 months after onset. (F) Final follow-up axial FSE-T2 MRI shows regression of hyperintensities (arrow). Laboratory investigations, including blood electrolytes, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, liver function, and blood cell count (particularly white blood cells, 5.9 g/L, normal 4–11), were normal. HIV, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination, and Lyme disease screening was negative. VGKC and NMDA antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, and anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies were also negative. Characterization of APOE gene showed a heterozygous APOE with ε4/ε3 alleles. Finally, CSF examination revealed increased protein concentration (1.45 g/L, normal <0.45), normal cell count (<1 M/L, normal 0–5), normal glucose level (4.0 mmol/L, normal 2.8–4.0), no oligoclonal bands, and no abnormal cells. The subacute evolution of the clinical picture and apraxia should prompt a thorough assessment for Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease. However, the MRI did not support this hypothesis. Questions for consideration:

1. What is your diagnosis at this stage? 2. How would you confirm the diagnosis? GO TO SECTION 4 Section 4

The clinical picture, imaging, CSF, and blood workup are suggestive of inflammatory cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA-I). The patient also carried the APOE ε4 allele, which increases the risks of β-amyloid peptide deposition and CAA-related hemorrhage compared to carriers of the common ε3 alleles. To confirm the diagnosis, we performed a brain biopsy in the left posterior parietal lobe including cortical and subcortical brain tissue. Cerebral biopsy showed transmural inflammatory infiltrates and amyloid deposition within vessels, and perivascular inflammatory infiltrates with reactive astrogliosis and microglial activation (figure 2). This provides evidence for 2 variants of CAA-I. The transmural inflammatory infiltrate is a destructive vasculitic process that characterizes Aβ-related angiitis (ABRA), and perivascular inflammatory infiltrates are characteristic of CAA-related inflammation (CAA-ri).2 Both subtypes can coexist in patients with CAA-I3 and respond to immunosuppressive treatment, but it is not established whether such pathologic subtypes translate into separate entities that require different therapeutic management.2 Figure 2 Cortical brain biopsy in the left parietal lobe (A) NeuN immunostaining shows cortical edema and loss of neurons (magnification ×100). (B) Hematoxylin & eosin staining shows eosinophilic deposits within the wall of a cortical vessel, lumen stenosis, and perivascular inflammatory infiltrates (magnification ×400). (C) Congo red staining shows amyloid deposits within the wall of cerebral and meningeal vessels (magnification ×40). (D) β-Amyloid immunostaining shows Aβ deposition within the walls of a cortical vessel (magnification ×400). Questions for consideration:

1. Which treatment would you start? 2. How would you relate the history of transient symptoms (vertical diplopia) to the diagnosis of CAA-I? GO TO SECTION 5 Section 5

We initiated immunosuppressive treatment, consisting of oral prednisone, 1 mg/kg a day, tapered over 3 months, with a good initial clinical and radiologic evolution. However, 1 month after the end of immunosuppression (i.e., 4 months after diagnosis of CAA-I), the patient experienced rapid worsening of cognitive functions. MRI at the time showed the recurrence of the same initial hyperintensity at the same location, and an acute, asymptomatic diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) punctiform ischemia in the right subcortical parietal lobe. We reinitiated oral prednisone and introduced oral azathioprine with a favorable clinical evolution. Follow-up MRI did not show recurrence of the inflammatory findings of CAA, but 6 new lobar microbleeds were reported over the 36-month follow-up. Regarding the episode of regressive vertical diplopia presented by our patient 2 months prior to admission, several hypotheses may exist. Transient focal neurological episodes or “amyloid spells,” defined as short, recurrent, stereotyped, spreading neurologic symptoms, are frequently reported in patients with CAA and are often related to superficial hemosiderosis or subarachnoid hemorrhage.3 A TIA is also possible given the age, cardiovascular risk factors, and detection of episodes of atrial fibrillation. Interestingly, small asymptomatic DWI ischemic lesions have been described recently in patients with CAA over the course of the disease.3,4 Discussion

The diagnosis of CAA-I was established based on (1) cerebral MRI showing rapid onset leukoencephalopathy and edema; (2) CSF analysis displaying mildly elevated protein concentration, but no pleiocytosis; and (3) neuropathology demonstrating perivascular inflammation associated with amyloid deposits in cortical vessels and transmural and perivascular inflammation. Before confirmation with cerebral biopsy, our patient met the diagnostic criteria of probable CAA-I: (1) age >40 years; (2) clinical symptoms, such as headaches or cognitive disturbances, not directly attributable to intracerebral hemorrhage; (3) asymmetric WMD patterns that extend to the immediately subcortical area; and (4) presence of cortico–subcortical hemorrhagic lesions.5 The inflammatory variants of CAA have gained a great amount of interest lately because of their increased incidence in the elderly population. Unlike classical CAA, inflammatory variants do not usually present with intracerebral hemorrhage, and the symptoms may be reversed by immunomodulatory therapy.4 However, CAA without inflammation can also exhibit infiltrative white matter processes.6 In order to avoid undue immunosuppressive treatment and the side effects thereof, we carried out a brain biopsy to look for vascular inflammation that characterizes CAA-I. An interesting point raised by this case is the speed of the clinical and radiologic course. The fact that lobar microbleeds were present before the onset of CAA-I supports the preexistence of CAA. The subsequent cognitive symptoms were more likely linked to the CAA-I, as supported by the clinical and radiologic features that progressed rapidly over 2 months. Based on repetitive MRIs and cerebral biopsy findings, our case illustrates that the course of CAA-I may be subacute and clearly distinct from the more progressive evolution of the noninflammatory form of CAA.6 A second interesting point is the management of transient neurologic symptoms and the ischemic lesion on DWI attributed to CAA.7,8 Our patient had CAA, but also cardiovascular disease risks factors (diabetes, hypertension) and episodes of atrial fibrillation. The presence of ≥5 cerebral microbleeds carries a major risk of intracerebral hemorrhage with anticoagulant use (odds ratio 5.50 or 2.8%/y).9 Therefore, we opted for a percutaneous left atrial appendage closure, although it is not known if the bleeding risk is increased to the same extent in the inflammatory form of CAA. Author contributions

Research project conception: E. Carrera. Research project execution: W. Bouthour, L. Sveikata. Writing of the first draft: W. Bouthour, L. Sveikata. Specialized material (radiology, pathology): M.I. Vargas, J.A. Lobrinus. Review and critique: E. Carrera, M.I. Vargas, J.A. Lobrinus. Study funding

No targeted funding reported. Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures. * © 2018 American Academy of Neurology

1 note

·

View note