#United States Coast Guard Cutter

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Three Girls

FV Three Girls burnt & sunk in Gulf of Maine; 6 rescued by USCG

Photo: United States Coast Guard On the night of August 12, the 81 foot long fishing vessel Three Girls (MMSI: 368140980) caught fire in the Gulf of Maine off Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The groundfish trawler had departed from Boston and was positioned some 100 miles east of Portsmouth when the fire broke onboard the vessel. The United States Coast Guard received a distress call from the Three…

View On WordPress

#Fire#Fishing vessel#Gulf of Maine#New Hampshire#Portsmouth#sank#Three Girls#United States Coast Guard Cutter#William Chadwick

1 note

·

View note

Text

USCG EDGAR CULBERTSON (WPC-1137) and Battleship Texas during the Texian Navy Day Parade.

Photographed by 409dronegraphy on September 21, 2024.

Posted by Michael Grimes on the Battleship Texas Foundation Facebook Group: link

#Battleship TEXAS#Battleship Texas Foundation#USS TEXAS (BB-35)#USS TEXAS#New York Class#Dreadnought#Battleship#Warship#Ship#Museum Ship#Update#Gulf Copper#Galveston#Texas#Repairs#Restoration#USCG EDGAR CULBERTSON (WPC-1137)#USCG EDGAR CULBERTSON#Sentinel Class#Cutter#United States Coast Guard#USCG#September#2024#my post

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

#migrants#migrant interdicted#newport beach#california#us coast guard#united states#coast guard cutter narwhal

1 note

·

View note

Text

USRC Bear in the Arctic, by Patrick O'Brien (1960-)

(USRC stands for United States Revenue Cutter) The USRC Bear was probably the most famous ship of the US Coast Guard. She had a long and varied career serving in the upper latitudes. In 1909 she assisted in the relief after the big earthquake in San Francisco.

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

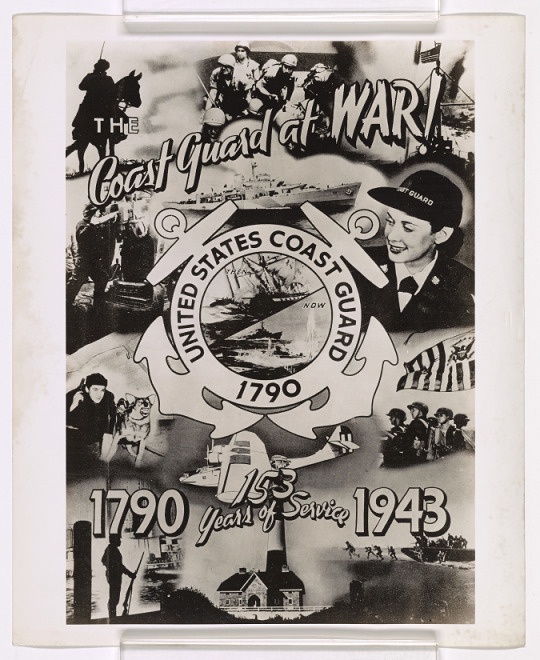

The Coast Guard celebrated its 153rd anniversary during WWII with this poster, August 2, 1943.

Record Group 26: Records of the U.S. Coast Guard

Series: Photographs of Activities, Facilities, and Personalities

File Unit: Port Security; Photographs of Posters

Image description: Poster reading “The Coast Guard at WAR! / United States Coast Guard 1790 / 1790 / 153 Years of Service / 1943” Photos and illustrations show: A man on horseback, holding a sword; a group of men in uniform, wearing helmets; the American flag flying from a ship; a smiling woman in uniform; modern Coast Guardsmen under the flag of the Revenue Cutter Service; men jumping from a landing craft and running up a beach; a lighthouse; a man standing guard, holding a rifle; a Coast Guard aircraft; a man in black cap with a snarling dog; a man loading ammunition into a ship’s gun; a Coast Guard ship; in the center is the Coast Guard logo with illustrations of a 1799 battle against a French privateer, and a Coast Guard cutter sinking a U-boat.

#archivesgov#August 2#1943#1940s#World War II#WWII#military#U.S. Coast Guard#war#poster#graphic design

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

KODIAK, Alaska—At Coast Guard Air Station Kodiak, the USCGC Stratton, a 418-foot national security cutter, was hemmed into port by a thin layer of ice that had formed overnight in the January cold. Named for the U.S. Coast Guard’s first female officer, Dorothy Stratton, the ship was not designed for ice; its home port is in Alameda, California. After serving missions in the Indo-Pacific, it was brought to Alaska because it was available.

Soon the sun would rise, and the ice would surely melt, the junior officers surmised from the weather decks. The commanding officer nevertheless approved the use of a local tugboat to weave in front of the cutter, breaking up the wafer-like shards of ice as the Stratton steamed away from shore and embarked toward the Bering Sea.

In the last decade, as melting ice created opportunities for fishing and extraction, the Arctic has transformed from a zone of cooperation to one of geopolitical upheaval, where Russia, China, India, and Turkey, among others, are expanding their footprints to match their global ambitions. But the United States is now playing catch-up in a region where it once held significant sway.

One of the Coast Guard’s unofficial mottos is “We do more with less.” True to form, the United States faces a serious shortage of icebreaker ships, which are critical for performing polar missions, leaving national security cutters and other vessels like the Stratton that are not ice-capable with an outsized role in the country’s scramble to compete in the high north. For the 16 days I spent aboard the Stratton this year, it was the sole Coast Guard ship operating in the Bering Sea, conducting fishery inspections aboard trawlers, training with search and rescue helicopter crews, and monitoring the Russian maritime border.

Although the Stratton’s crew was up to this task, their equipment was not. A brief tour aboard the cutter shed light on the Coast Guard’s operational limitations and resource constraints. Unless Washington significantly shifts its approach, the Stratton will remain a microcosm of the United States’ journey in the Arctic: a once dominant force that can no longer effectively assert its interests in a region undergoing rapid transformation.

During the Cold War, the United States invested in Alaska as a crucial fixture of the country’s future. Of these investments, one of the most significant was the construction of the Dalton Highway in 1974, which paved the way for the controversial Trans-Alaska Pipeline and the U.S. entry as a major player in the global oil trade. Recognizing Alaska’s potential as a linchpin of national defense, leaders also invested heavily in the region’s security. In 1957, the United States began operating a northern network of early warning defense systems called the Distant Early Warning Line, and in 1958, it founded what became known as the North American Aerospace Defense Command.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, such exigencies seemed excessive. The north once again became a domain for partnership among Arctic countries, a period that many call “Arctic exceptionalism”—or, as the Norwegians put it, “high north, low tension.”

But after the turn of the millennium, under President Vladimir Putin, Russia took a more assertive stance in the Arctic, modernizing Cold War-era military installations and increasing its testing of hypersonic munitions. In a telling display in 2007, Russian divers planted their national flag on the North Pole’s seabed. Russia wasn’t alone in its heightened interest, and soon even countries without Arctic territory wanted in on the action. China expanded its icebreaker fleet and sought to fund its Polar Silk Road infrastructure projects across Scandinavia and Greenland (though those efforts were blocked by Western intervention). Even India recently drafted its first Arctic strategy, while Turkey ratified a treaty giving its citizens commercial and recreational access to Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean.

Over the past decade, the United States lagged behind, focusing instead on the challenges posed to its interests in the Middle East, the South China Sea, and Ukraine. Its Arctic early warning system became outdated. Infrastructure off the coast of Alaska that climatologists use to predict typhoons remained uninstalled, seen as a luxury that the state and federal governments could not afford. In 2020, an engine fire in the sole Coast Guard Arctic icebreaker nearly scuttled a plan to retrieve scientific instruments and data from vessels moored in the Arctic Ocean. Two years later, a Defense Department inspector general report revealed substantial issues with the structural integrity of runways and barracks of U.S. bases across the Arctic and sub-Arctic.

Until recently, U.S. policymakers had little interest in reinstating lost Arctic competence. Only in the last three years—once Washington noticed the advances being made by China and Russia—have lawmakers and military leaders begun to formulate a cohesive Arctic strategy, and it shows.

On patrol with the Stratton, the effects of this delay were apparent. The warm-weather crew struggled to adapt to the climate, having recently returned from warmer Indo-Pacific climates. The resilient group deiced its patrol boats and the helicopter pad tie-downs with a concoction conceived through trial and error. “Happy lights,” which are supposed to boost serotonin levels, were placed around the interior of the ship to help the crew overcome the shorter days. But the crew often turned the lights off; with only a few hours of natural daylight and few portholes on the ship through which to view it anyway, the lights did not do much.

The Coast Guard is the United States’ most neglected national defense asset. It is woefully under-resourced, especially in the Arctic and sub-Arctic, where systemic issues are hindering U.S. hopes of being a major power.

First and foremost is its limited icebreaker fleet. The United States has only two working icebreakers. Of these two, only one, the USCGC Healy, is primarily deployed to the Arctic; the other, the USCGC Polar Star, is deployed to Antarctica. By comparison, Russia, which has a significant Arctic Ocean shoreline, has more than 50 icebreakers, while China has two capable of Arctic missions and at least one more that will be completed by next year.

Coast Guard and defense officials have repeatedly testified before Congress that the service requires at least six polar icebreakers, three of which would be as ice-capable as the Healy, which has been in service for 27 years. The program has suffered nearly a decade of delays because of project mismanagement and a lack of funds. As one former diplomat told me, “A strategy without budget is hallucination.” The first boat under the Polar Security Cutter program was supposed to be delivered by this year. The new estimated arrival date, officials told me, will more likely be 2030.

“Once we have the detailed design, it will be several years—three plus—to begin, to get completion on that ship,” Adm. Linda Fagan, the commandant of the Coast Guard, told Congress last April. “I would give you a date if I had one.”

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has long warned that the U.S. government and military, including the Coast Guard, have made serious miscalculations in their Arctic efforts. For one, the Coast Guard’s acquisition process for new boats is hampered by continual changes to design and a failure to contract competent shipbuilders. Moreover, the GAO found in a 2023 report that discontinuity among Arctic leadership in the State Department and a failure by the Coast Guard to improve its capability gaps “hinder implementation of U.S. Arctic priorities outlined in the 2022 strategy.”

Far more than national security is at stake. The Arctic is a zone of great economic importance for the United States. The Bering Sea alone provides the United States with 60 percent of its fisheries, not to mention substantial oil and natural gas revenue. An Arctic presence is also important for achieving U.S. climate goals. Helping to reduce or eliminate emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, and black carbon in the Arctic protects carbon-storing habitats such as the tundra, forests, and coastal marshes.

Capt. Brian Krautler, the Stratton’s commanding officer, knows these problems well. Having previously served on Arctic vessels, he was perhaps the ideal officer to lead the Stratton on this unfamiliar mission. After a boarding team was recalled due to heavy seas and an overiced vessel, Krautler lamented the constraints under which he was working. “We are an Arctic nation that doesn’t know how to be an Arctic nation,” he said.

The Stratton reached its first port call in Unalaska, a sleepy fishing town home to the port of Dutch Harbor. Signs around Unalaska declare, “Welcome to the #1 Commercial Fishing Port in the United States.” The port is largely forgotten by Washington and federal entities in the region, but there is evidence all around of its onetime importance to U.S. national security: Concrete pillboxes from World War II line the roads, and trenches mark the hillocks around the harbor.

As Washington pivoted away from the Arctic, Alaska and its Native communities have become more marginalized. Vincent Tutiakoff, the mayor of Unalaska, is particularly frustrated by the shift. Even though Washington made promises to grant greater access to federal resources to support Indigenous communities, it has evaded responsibility for environmental cleanup initiatives and failed to adequately address climate change.

Federal and state governments have virtually abandoned all development opportunities in Unalaska, and initiatives from fish processing plants to a geothermal energy project have been hindered by the U.S. Energy Department’s sluggish response to its Arctic Energy Office’s open call for funding opportunities. “I don’t know what they’re doing,” Tutiakoff said of state and federal agencies.

Making matters worse, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is moving ahead to make the northern Alaska city of Nome the site of the nation’s next deep-water port rather than build infrastructure near Unalaska, the gateway to the American Arctic and the port of call for the few patrol ships tasked with its security. It seems that the decision was based on the accessibility needs of cruise ships; Unalaska is not necessarily a vacation destination.

By failing to invest in places like Unalaska, the United States is hobbling its own chances for growth. The region could be home to major advances in the green energy transition or cloud computing storage, but without investment this potential will be lost.

In the last year, the United States has tried to claw back some of what it has lost to atrophy. It has inched closer to confirming the appointment of Mike Sfraga as the first U.S. ambassador-at-large to the Arctic. In March, the U.S. Marine Corps and Navy participated in NATO exercises in the Arctic region of Finland, Norway, and Sweden. The U.S. Defense Department hosted an Arctic dialogue in January ahead of the anticipated release of a revised Arctic strategy, and the State Department signed a flurry of defense cooperation agreements with Nordic allies late last year.

Nevertheless, it has a long way to go. Tethered to the docks at Dutch Harbor, the weather-worn Stratton reflected the gap between the United States’ Arctic capabilities and its ambitions. Its paint was chipped by wind and waves, and a generator needed a replacement part from California. Much of the crew had never been to Alaska before. On the day the ship pulled into port, the crew milled about, gawking at a bald eagle that alighted on the bow and taking advantage of their few days in port before setting out again into hazardous conditions.

“I know we’re supposed to do more with less,” a steward aboard the Stratton told me, “but it’s hard.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

UNCLAS //N05752// SUBJ: FINAL FAREWELL 1. I SERVED WITH HONOR FOR ALMOST FORTY-SIX YEARS, IN WAR AND PEACE, IN THE ATLANTIC AND PACIFIC. WITH DUTY AS DIVERSE AS SAVING LIVES TO SINKING U-BOATS, OCEAN STATIONS TO FISHERIES ENFORCEMENT, AND FROM TRAINING CADETS TO BEING YOUR FLAGSHIP. I HAVE BEEN ALWAYS READY TO SERVE. 2. TODAY WAS MY FINAL DUTY. I WAS A TARGET FOR A MISSILE TEST. ITS SUCCESS WAS YOUR LOSS AND MY DEMISE. NOW KING NEPTUNE HAS CALLED ME TO MY FINAL REST IN 2,600 FATHOMS AT 22-48N 160-06W. 3. MOURN NOT, ALL WHO HAVE SAILED WITH ME. A NEW CUTTER CAMPBELL BEARING MY NAME, WMEC-909, WILL SOON CONTINUE THE HERITAGE. I BID ADIEU. THE QUEEN IS DEAD. LONG LIVE THE QUEEN.

The final message of the United States Coast Guard Treasury-class Cutter USCGC Campbell, broadcast 29 November 1984. Commissioned in 1936, she was called the 'Queen of the Seas'. When she was decommissioned in 1982, she was the oldest vessel in the Coast Guard.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

United States Coast Guard Cutter Porter (CG-7) circa 1924-30. This was formerly the U.S. Navy Tucker-class destroyer USS Porter (DD-59), one of 25 ex-Navy destroyers turned over to the Coast Guard in 1924 to enforce Prohibition and battle rumrunners. During her Coast Guard service, Porter captured the rum-running vessel Conseulo II (the former Louise) off the coast of Long Island. The destroyer was returned to the Navy in 1933 but scrapped in 1934 without being recommissioned.

#1920s#prohibition#uss porter#uscgc porter#coast guard cutter#uscg#rum patrol#Tucker class destroyer#1925#1927#1926#1928#1929#1930#1931#1932#1933#destroyer#USS Porter (DD-59)#USCGC Porter (CG-7)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

U.S. Coast Guard Day

U.S. Coast Guard Day honors the United States Coast Guard, the military branch that protects the waters and shorelines of the United States. It is celebrated on the anniversary of the founding of the Revenue Marine, the forerunner of the Coast Guard. On August 4, 1790, the United States Congress created the Revenue Marine and authorized the construction of 10 revenue cutters to be used to enforce U.S. tariff laws—to stop illegal smuggling and collect revenue on incoming goods. The Revenue Marine was housed in the Department of Treasury and thus directed by Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton.

The Revenue Marine's name was later changed to the Revenue Cutter Service. Then, in 1915, the Revenue Cutter Service was combined with the United States Life-Saving Service to form the United States Coast Guard. This created a single maritime service, bringing together one devoted to enforcing maritime laws and one dedicated to saving lives. The United States Lighthouse Service became part of the Coast Guard in 1939, and the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation became part of it in 1946. In 1967, the Coast Guard was transferred from the Department of Treasury to the newly-created Department of Transportation. Similarly, it was transferred to the Department of Homeland Security in 2003.

U.S. Coast Guard Day has been marked in some form since at least 1928. Presidents have proclaimed August 4th as "Coast Guard Day." Harry Truman did so in 1948, and Ronald Reagan did so in 1984 after being requested to do so by Congress. In large part, U.S. Coast Guard Day is an internal celebration by Coast Guard personnel and their families, but others join in honoring Coast Guard members as well. Coast Guard units often organize picnics and informal sports competitions, where they celebrate with family and friends. The American flag is typically flown on the day, particularly by those who have family members in the Coast Guard. Grand Haven, Michigan, known as Coast Guard City, USA, holds the annual Coast Guard Festival each year around August 4th.

The Coast Guard defines itself as "the principal Federal agency responsible for maritime safety, security, and environmental stewardship in U.S. ports and inland waterways, along more than 95,000 miles of U.S. coastline, throughout the 4.5 million square miles of U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), and on the high seas." It has active duty, reserve, and civilian employees, and there also is a Coast Guard Auxiliary. It is divided into two area commands, the Pacific Area and the Atlantic Area, and these are divided into nine district commands. Many Coast Guard stations are located in the districts. The Coast Guard fleet consists of cutters, boats, and fixed and rotary-wing aircraft. Today this branch of the military and its members are honored with U.S. Coast Guard Day!

How to Observe U.S. Coast Guard Day

Some ways you could observe the day include:

Make plans to attend New Haven's Coast Guard Festival, Petaluma's Coast Guard Day, or another public event in honor of the Coast Guard's founding. If you are a member of the Coast Guard, or if you have a relative in the Coast Guard, see if there are any private events being held in honor of the day that you can attend.

Stop at a Coast Guard station.

Fly the American flag.

Learn more about the responsibilities and functions of the Coast Guard. You could do so by reading a book such as The Coast Guard or The United States Coast Guard and National Defense: A History from World War I to the Present, or by exploring the official United States Coast Guard website.

Watch a film that features the Coast Guard.

Join the Coast Guard.

Source

#CCGS Laredo Sound#US Coast Guard 87301#U.S. Coast Guard Birthday#U.S. Coast Guard Day#Eureka#USCoastGuardDay#CCGS Sir Wilfrid Grenfell#Canada#Canadian Coast Guard#CCGS Placentia Hope#National Naval Aviation Museum#St. John's#Pensacola#St. Thomas#Charlotte Amalie#architecture#engineering#original photography#travel#vacation#tourist attraction#U.S. Coast Guard Barque Eagle#Boston#San Francisco#Golden Gate Bridge#4 August#4 August 1790#anniversary#USA#cityscape

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 17: Myrtle Hazard!

Myrtle Hazard, née Holthaus, was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1892. As a child, like many of her era, she suffered a bout with polio, but Myrtle was a fortunate survivor. As a teenager, she developed an interest in radio, taking courses at the YMCA and learning Morse code and electrical skills. She married at eighteen, to Claude Hazard, but by the time the United States entered the First World War, she was a widow, left with a young son to support.

The US Coast Guard, put on a wartime footing and needing more personnel, advertised seeking those with telegraph and radio skills. Myrtle applied in person, and was initially turned down - but a nearby lieutenant thought otherwise. He needed a skilled radio operator, male or female, and was impressed by Myrtle’s qualifications. She became the first enlisted woman in the Coast Guard.

Myrtle, who had to put together her own uniform, served as a radio operator throughout the war, reaching the rank of Electrician’s Mate First Class. She retired, remarried, and lived a relatively quiet life until her death in 1951.

The Sentinel-class cutter USCGC Myrtle Hazard, launched in 2020, was named in her honor.

#myrtle hazard#american history#uscg#history#awesome ladies of history#october 2024#my art#digital art

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

TDIH: USCG sinks German submarine U-352

On this day in 1942, a United States Coast Guard cutter sinks a German submarine just off the coast of North Carolina. Dozens of Germans are captured.

Yes, you read that correctly. A German submarine was patrolling the east coast of the United States during the early months of World War II. The Germans captured that day were the first foreign prisoners of war to be held on American soil since the War of 1812.

Trouble began on the afternoon of May 9.

U.S.C.G. Icarus was then traveling from Staten Island, New York, to Key West, Florida. She was equipped with relatively obsolete sound detection gear. Nevertheless, at about 4:20 p.m., she picked up a “mushy” sound contact off her port bow.

The story continues here: https://www.taraross.com/post/tdih-uscg-icarus

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

#32

For a very long time, the US Coast Guard has effectively operated as a smaller navy. But rather than fight on the high seas with battleships bristling with cannon, it simply made do with various patrol boats & cutters. Until WWII it mainly played the role of intercepting alcohol smugglers & the like. This all had changed by the time RD 3/c Alvin Cooke had enlisted.

Now, the Coast Guard didn't merely prevent drug trafficking or save wayward boaters, it defended the boundaries of the nation.

Alvin is an example of what was called the Beach Patrol, watching the shores of the United States for U-boats or raiders landing to cause havoc.

For this he is dressed in the sensible undress blues, the middle ground between the stuffy dress blues & the unsightly dungarees (which for many years were not authorized to be worn off a ship). There were no decorations, no neckerchief, only a rating if one had earned it. There was no piping to keep clean, not even any buttons on the cuff.

For equipment he carries a fairly typical set of equipment for someone who isn't posted far from the nearest galley.

Alvin is armed with the even then aging & superseded M1903 Springfield, all the newest M1 Garands going straight to the front.

While some patrolled in boats or on horseback, his unhappy lot is to negotiate the soft sand in his boots & curse the failings of his Dismounted Leggings

Alvin is special for several reasons: firstly he is yet another type of non GI Joe action figure & his uniform is custom made - that set of undress blues can't simply be bought, I had to modify an existing knock off uniform. Considering everything, it turned out fantastically well. There are a few things I'm still working on before I can call him complete, but he's pretty darn close.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Special "Thanks!" to the United States Coast Guard Cutter Campbell Volunteers who helped continue the efforts of recovery in Indigenous Park after Hurricane Ian knocked over a lot of trees. USCGC Campbell crew volunteers helped right a number of tipped trees and helped remove debris around the park. Great job!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Personalized Us Army Green Beret Special Forces Bomber Jacket

More Than Just a Jacket:A Statement of Pride and Belonging This isn't just a bomber jacket; it's a statement.It's a symbol of the dedication, courage, and unwavering commitment embodied by the Green Berets.It's a tangible representation of the brotherhood forged in the crucible of elite training and dangerous missions. For those who wear the Green Beret, this jacket is more than just a piece of clothing. It's a tangible link to a shared history, a badge of honor that speaks volumes without a single word.It's a constant reminder of the sacrifices made, the challenges overcome, and the unwavering loyalty that binds the Special Forces community. For those who admire the Green Berets, this jacket is a unique opportunity to express your respect and admiration for these extraordinary individuals.It's a way to show your support for the men and women who dedicate their lives to protecting our freedom.It's a statement of pride in the values and principles that the Green Berets represent. More than just a fashion statement, this personalized jacket allows you to: Celebrate your heritage: If you are a Green Beret, this jacket is a way to proudly display your lineage and connect with your fellow brothers-in-arms. Honor the legacy:If you admire the Green Berets, this jacket is a way to pay tribute to their service and sacrifice. Make a statement:Show your support for the men and women who stand on the front lines, protecting our freedom and ensuring our safety. This isn't just a jacket. It's a symbol.It's a statement.It's a testament to the spirit of the Green Berets, and a badge of honor for those who wear it proudly.

Get it here : Personalized Us Army Green Beret Special Forces Bomber Jacket

Home Page : tshirtslowprice.com

Related : https://progiftreview.tumblr.com/post/720625309464068096/united-states-coast-guard-hamilton-class-cutter

1 note

·

View note

Text

Berserk Guts And Casca Ugly Christmas Sweater

More Than Just a Sweater: A Statement of Fandom This isn't just another ugly Christmas sweater. This is a declaration. It's a bold statement of your love for the epic world of Berserk, a way to show your allegiance to the indomitable Guts and the fierce Casca. This sweater isn't just about festive cheer; it's about embracing the dark and gritty side of fantasy, the relentless fight against overwhelming odds, and the unwavering loyalty that binds characters together. Imagine the reactions when you wear this sweater to your next holiday gathering. You'll be the center of attention, sparking conversations with fellow Berserk fans and introducing the series to curious newcomers. Picture the camaraderie, the shared understanding, the nod of recognition from a fellow warrior of the Black Swordsman's path. This isn't just an ugly Christmas sweater; it's a conversation starter, a symbol of your passion, a badge of honor.It's a way to celebrate the dark beauty of Berserk, the indomitable spirit of its characters, and the enduring power of a story that resonates with millions. So don't just wear a sweater, wear a statement. Wear the Berserk Guts and Casca Ugly Christmas Sweater, and let the world know who you stand with.

Get it here : Berserk Guts And Casca Ugly Christmas Sweater

Home Page : tshirtslowprice.com

Related : https://giftsforus.tumblr.com/post/720628636594618368/united-states-coast-guard-cutter-joshua-appleby

1 note

·

View note

Text

Events 8.4 (before 1930)

598 – Goguryeo-Sui War: In response to a Goguryeo (Korean) incursion into Liaoxi, Emperor Wéndi of Sui orders his youngest son, Yang Liang (assisted by the co-prime minister Gao Jiong), to conquer Goguryeo during the Manchurian rainy season, with a Chinese army and navy. 1265 – Second Barons' War: Battle of Evesham: The army of Prince Edward (the future king Edward I of England) defeats the forces of rebellious barons led by Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, killing de Montfort and many of his allies. 1327 – First War of Scottish Independence: James Douglas leads a raid into Weardale and almost kills Edward III of England. 1578 – Battle of Al Kasr al Kebir: The Moroccans defeat the Portuguese. King Sebastian of Portugal is killed in the battle, leaving his elderly uncle, Cardinal Henry, as his heir. This initiates a succession crisis in Portugal. 1693 – Date traditionally ascribed to Dom Perignon's invention of champagne; it is not clear whether he actually invented champagne, however he has been credited as an innovator who developed the techniques used to perfect sparkling wine. 1701 – Great Peace of Montreal between New France and First Nations is signed. 1704 – War of the Spanish Succession: Gibraltar is captured by an English and Dutch fleet, commanded by Admiral Sir George Rooke and allied with Archduke Charles. 1783 – Mount Asama erupts in Japan, killing about 1,400 people (Tenmei eruption). The eruption causes a famine, which results in an additional 20,000 deaths. 1789 – France: abolition of feudalism by the National Constituent Assembly. 1790 – A newly passed tariff act creates the Revenue Cutter Service (the forerunner of the United States Coast Guard). 1791 – The Treaty of Sistova is signed, ending the Ottoman–Habsburg wars. 1796 – French Revolutionary Wars: Napoleon leads the French Army of Italy to victory in the Battle of Lonato. 1821 – The Saturday Evening Post is published for the first time as a weekly newspaper. 1854 – The Hinomaru is established as the official flag to be flown from Japanese ships. 1863 – Matica slovenská, Slovakia's public-law cultural and scientific institution focusing on topics around the Slovak nation, is established in Martin. 1873 – American Indian Wars: While protecting a railroad survey party in Montana, the United States 7th Cavalry, under Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer clashes for the first time with the Cheyenne and Lakota people near the Tongue River; only one man on each side is killed. 1887 – Granny, a sea anemone, died in Edinburgh after nearly 60 years in captivity. Her death was reported in The Scotsman and The New York Times. 1889 – The Great Fire of Spokane, Washington destroys some 32 blocks of the city, prompting a mass rebuilding project. 1892 – The father and stepmother of Lizzie Borden are found murdered in their Fall River, Massachusetts home. She will be tried and acquitted for the crimes a year later. 1914 – World War I: In response to the German invasion of Belgium, Belgium and the British Empire declare war on Germany. The United States declares its neutrality. 1915 – World War I: The German 12th Army occupies Warsaw during the Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive and the Great Retreat of 1915. 1921 – Bolshevik–Makhnovist conflict: Mikhail Frunze declares victory over the Makhnovshchina. 1924 – Diplomatic relations between Mexico and the Soviet Union are established.

0 notes