#Ugaritic texts

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Ugaritic texts, found in Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra, Syria), date back to the late Bronze Age. They offer insights into the religion of the Canaanites, who lived at the same time as early Israelites. These texts include myths & rituals similar to those in the Bible, mentioning gods like El & Baal Hadad. For instance, Baal's story as a storm god parallels Yahweh in the Psalms, & Baal's battle with the sea god Yam is like Yahweh defeating chaotic waters. These similarities suggest biblical writers were influenced by Canaanite mythology.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts” by Mark S. Smith is in my wish list.

0 notes

Text

Melchizedek

View On WordPress

#Bible#Dead Sea Scrolls#Events#Freemasonry#gNOSTIC#God#Jesus#Melchizedek#Messianic#Mystical#Symbolism#Theological#Theophqany#Ugaritic mythology#Ugaritic texts

1 note

·

View note

Text

So I’m reading the Baal Cycle right? Fun little epic poem about the Canaanite god Baal Hadad and the rest of his pantheon friends (hi Anat <3).

And uh.

Who the fuck was gonna tell me that El (also the capital G God of Judaism/Christianity/etc) had a wife and she HELPED CREATE THE WORLD WITH HIM I—

Asherah you’ve been done so dirty… babygirl I’m so sorry they forgot you and turned you into a pole

#im begging anyone with brainworms about this to come talk to me im going nuts#ugaritic mythology#ugaritic texts speak to me#tell me your secrets#baal cycle#canaanite mythology#asherah#athirat#i wanna kick this beehive so bad too people are MAD mad about El’s wife

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

academic writing is starting out w one thesis and landing somewhere totally different

#somehow I've written like 13 pages so far abt what deities and stories were absorbed into the mythology of god#that wasn't the intent it was just going to be a look at the connections between the ugaritic texts and the tanakh but well. here we are.#capstone of my entire BA being the thesis that God is made up of 2 goddesses and 2 gods.#he's slaying in a bigender manner or whatever#actually more than that bc this is just the ugaritic texts but you can find other gods that got absorbed into god from other nearby#or more ancient traditions#which to Me is very lovely and kind of poetic but that's on a personal spiritual belief note#(not the historical absorption being lovely but rather the spiritual idea that god IS every god. one that has always appealed to me)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

A/n: so I found this archeological essay about Baal's origin and it's quite fascinating to read about it, as it was in my mother tongue I had translated it to english so others could read as well. This post is long btw, read it when you have time! ^^

Introduction

The fact that Baal is so prominent in the Bible has always attracted research attention. Why is he so present? What led the authors/editors of the biblical texts to mention Baal so often? In general, Baal has been interpreted as the adversary of Yahweh, as the one who leads God's people astray.

However, with the archaeological discoveries of a large number of artifacts, stelae, ostraca, seals, etc., which reveal the widespread presence of the Baal cult, not only in Israel and Judah, but also throughout the Levant, another view of Baal began to emerge. The discoveries of the tablets from Ugarit (Rash-Shamra), from the 1929 excavations, contributed essentially to this.

The literature of Ugarit revealed to the world a society built around the worship of Baal. It revealed that the culture of Ugarit preceded Israelite culture and therefore influenced it enormously. In other words, it made it clear that the matrix of Israelite culture is found in Ugarit. We could say in clearer terms that the Old Testament is found in Ugaritic literature, which has Baal as the basis of its religious horizon.

Once this has been assimilated, another question arises. In other words, the old maxim imposes itself once again: the answer to one question opens the door to new questions. And the main one is: if the cultural matrix of Israel is in Ugarit, where, then, does the culture of Ugarit come from? What is the origin of Baal? It is with the answer to this question that this research will deal.

The Temple of Baal at Pella

In 2014, on a study expedition to Jordan’s archaeological sites, one of the sites on our list of places to visit was Pella (Tabagat Fahl), which is located about 2 km in a straight line east of the Jordan River, 10 km from Beth-Shean and 85 km northeast of Jerusalem. Our main objective was to visit the site that, according to one line of research, was the city to which many Judahites fled during the Jewish war of 66-73 CE, including Christians from the Markan community. Perhaps for this reason, the city was marked by a strong Christian presence during the Byzantine period (330-1453).

Many large churches were built in Pella during this period, some of the remains of which are still standing. Our focus was precisely on seeing these churches. However, when we arrived at the site we were surprised by a huge excavation of three impressive superimposed temples: from the Middle Bronze Age, the Late Bronze Age and the Iron I.

What caught our attention, and certainly that of the archaeologists as well, was the size of the first two superimposed temples (the Middle Bronze Age and the Late Bronze Age), no less than 32 meters long by 24 meters wide. It was a fortress-temple, with wide adobe walls, perhaps the largest ever found in the region. We then wondered to which God these temples had been dedicated.

Some years later, when I returned to research Pella and read the archaeologists’ report, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that in the second and third phases, the temple was dedicated to Baal. Let us briefly review some of the points in the report.

The temple was excavated during the 1994–2001 expeditions of the Australian Archaeological Mission in Sydney, led by archaeologist Stephen Bourke, in conjunction with the Jordanian Government’s Department of Antiquities. The archaeologists concluded that the temple was built around the 19th century BCE and was continually restored. The first phase of the temple was dated between 1800–1450; the second phase, between 1450–1000; and the third phase, between 1000–800, during which time the temple was reduced in size. Around the year 800, the city of Pella was destroyed and the temple was never rebuilt. The temple was oriented to the northeast, which points to the sunrise in summer.

The various objects of worship found inside the temple led archaeologists to conclude that in the beginning, in the first phase, although the evidence was not very reliable, during the Middle Bronze Age, the temple was dedicated to El, the God of the Canaanite pantheon. In the second phase, in the Late Bronze Age, the temple began to be dedicated to Baal. And in the third phase, in the Iron Age I, when Egyptian influence was already strongly noticeable, the temple began to be dedicated to the God Seth-Baal.

In short, in our opinion, the temple of Pella can be a kind of model for understanding the evolution of the cult of Baal throughout the Levant, the object of our research. Therefore, we will return to this site later.

The Gods of Time

Modern research is increasingly convinced of the great cultural influence that the region of Upper Mesopotamia, especially Anatolia and northern Syria, exerted on Lower Mesopotamia, as well as on the entire Levant. Hence the importance of seeking the roots of Levantine culture in the north. And, in our specific interest, of knowing the divinities that were worshipped there and how their cult migrated to the south, integrating or being absorbed by the local pantheons.

It is quite understandable that in the regions of Upper Mesopotamia, the main deities were linked to the fertility of the land, since these were regions with strong agricultural characteristics. In other words, regions that constantly depended on rain, but as such, were also prone to floods, storms, lightning, etc. The oldest god in Sumerian texts responsible for the weather (rain, winds, lightning, and thunder) is Iskur.

From the Middle Bronze Age onwards, in addition to Sumerian personal names with the theophoric element Iskur, Akkadian personal names with the theophoric element Hadu, Adad, or Adda began to appear. From then on, the names of Hadu/Adad became increasingly frequent, largely surpassing those of Iskur. In other words, it seems that Iskur is gradually merging into Hadu/Adad, whose functions and characteristics, in general, were the same.

The God Hadu of Aleppo

The God Hadu, with some linguistic variations (Haddu, Hadda, Hadad, Addu, Adad), depending on the region, ended up becoming the most important God of weather, specifically of storms, in the Ancient Near East. The oldest attestation of Hadu is found in a cuneiform text from the middle of the third millennium BCE in the city of Ebla, northern Syria.

There Hadu appears among the most important Gods of the pantheon with the name Hadda, from the Semitic root hdd (to thunder). “The fact that the root *hdd is no longer used in most Semitic languages of the Ancient Near East allows us to infer that the divine name is very old”.

The most important sanctuary of Hadu in the entire region of what would later become Syria (Aram-Damascus, Ebla, etc.) was the temple of Aleppo (Halab). Aleppo is about ninety kilometers in a straight line northeast of Ugarit (Rash-Shamra). The temple of Hadu, on the hill of the present-day city of Aleppo, survived all periods of the history of the Ancient Near East, from the end of the Old Bronze Age to the Iron Age.

Even with the change of power of the empires of turn, the temple remained unshaken for more than a millennium. There was found a stele of the God Hadu in human form and standing on a bull, holding lightning in one hand and thunder in the other. Above the head of the image is the symbol of the Sun God, probably an Egyptian influence.

Hadu's consort was the goddess Habatu, who was worshipped in Aleppo and Ebla. The proximity of the important city of Ebla to Aleppo, about 55 km to the southeast as the crow flies, made these two cities, perhaps also Mari, the main center of Hadu's cult. Perhaps also, via the trade route, its largest centers of propagation. A seal with the god Hadu was also found in Ebla, next to a bull on a throne.

From northern Syria, the cult of Hadu, in the Iron II period, spread widely to Assyria and Babylonia, being taken up by kings, such as the kings of Aram-Damascus, Ben-Adad I (885–865), Ben-Adad II/Adadazer (860-843) and Ben-Adad III, son of Hazael (796-770); and the Assyrian king Adadnirari (811-783).

In other words, Hadu migrated from Aleppo to Assyria and Babylonia under the name Adad or Addad.

Hadu and Baal

Upper Mesopotamia, including the important cities of Aleppo, Ebla and Mari, underwent a profound political change at the end of the ancient Babylonian Empire (1790-1750), when Amorite rule in the region was supplanted by the Hurrians. The Hurrian god of weather (storms and rain, etc.) was Teshub. He was the main god of the Hurrian pantheon, king of the gods, of royalty and of the court.

However, Hadu continued to be worshipped in Aleppo and the region. In other words, with the arrival of the Hurrians, who dominated a large part of the city-states of the Levant, and their main god, Teshub, Hadu continued to be worshipped, practically in the same way as before, especially among the people. This is probably due to the similarity of the two weather gods, Teshub and Hadu.

Possibly also because the cult of Teshub was more specifically that of Hurrian royalty. In short, Hadu's temples remained as before, as did his image, now next to Teshub.

It is during this period, perhaps a little before the middle of the second millennium BCE, around 1600-1500, that the cult of Baal or Baalu, as the God of weather (rain, storms, fertility, etc.), began to emerge on the Syro-Palestinian coast. Not only temples to Baal/Baalu began to emerge on the Mediterranean coast, but also literature, as evidenced by the findings from Ugarit.

The cult of Baal emerged with a strong association between Hadu, Teshub and Baalu. The proximity of Aleppo to Ugarit helps to understand the influence that it, specifically its temple, exerted on Ugarit, on the Syro-Palestinian coast.

Baal is Hadu

The epithet Belu, Baalu, "lord", together with the proper name of a particular God, is attested in different Gods at various times in the Ancient Near East. The epithet is often used as a form of abbreviation for "lord of...", lord of a toponym or lord of the gods, etc., as in the case of "Bel Marduk".

Furthermore, the element Baalu found together with the name of different deities, mainly in Mesopotamia, should be understood as an epithet, a qualifier of the deity in question, not as the proper name of a God, of a single God. So, it is not correct to associate the form "Baalu" found in writings from Ebla, Tell Beydar, etc. of Mesopotamia as a precursor of the God Baal of the mid-second millennium and early first millennium BCE on the Syro-Palestinian coast.

From what can be determined in the writings found in Ugarit, the epithet Baal was initially associated with Hadu, as can be seen in some tablets, in which he is called Hadu. Over time, the epithet would end up replacing the name of the deity. In other words, Hadu becomes Baal. In this "metamorphosis," Baal becomes the most popular God on the Syro-Palestinian coast, as can be seen in the tablets of Ugarit.

However, there is some difference between the "old" God (Hadu) and the "new" God (Baal). Hadu's main characteristic was that he was the God who controlled storms, floods, lightning and thunder. He is often understood as a God with destructive powers. In this sense, he also had attributes of war, a characteristic particularly exploited by the kings of the day for their battles.

However, although he also controlled the rain, fertility was a rather secondary attribute of Hadu. There is little reference to Hadu as a God of fertility. In contrast, Baal is primarily the God of fertility, the one who sends the rain to water the land and ensure agriculture, the one who controls the cycle of rain and drought. Finally, as seen, we can affirm with relative certainty that Baal is Hadu.

Therefore, from the middle of the second millennium, with greater intensity at the turn of the second to the first millennium BCE, an intense development of the cult of Baal can be seen along the entire Mediterranean coast as far as Egypt. As an example of the spread of the cult of Baal in this region, it is enough to observe the titles that the kings of important coastal cities, such as Tyre and Byblos, adopted.

Kings of Tyre: Abibaal (993-981), Baal-Ezer I (946-930), Ethbaal I (878-847), Baal-Ezer II (846-841), Ethbaal II (750-739) and Baal I (609-599). Kings of Byblos (since the dates are not precise, we list only the names): Abibaal, Elibaal, Shafatbaal I, Shafatbaal II, Shafatbaal III and Yeharbaal.

Hadu's prominent role in the divine pantheon in the northern region helped Baal's expansion. The "new God" would develop in the fertile lands watered by Hadu. In the eastern region of the Levant, Baal would maintain more of Hadu's characteristics, as the God of storms and floods, while in the western region, as the God of fertility.

However, not exclusively of fertility, because, as can be seen in the Ugaritic myths, Baal would also identify himself as the God of storms, lightning and violent winds, etc., especially when related to Mount Saphon (Jebel el-Agra), where his dwelling was located. And, occasionally, also as the God of war, although much less frequently.

Baal son of Dagan and son of El

In Ugaritic mythology, Baal appears as the son of El and Asherah, father and mother of the Gods. However, in other tablets, Baal also appears as the son of Dagan. It is possible that this filiation to both Gods is due to the fact that El and Dagan, belonging to different pantheons, were known as the fathers of the Gods.

In the middle Euphrates, Dagan was associated with the Hurrian God Kumarbi and the Babylonian God Enlil, fathers of the Gods and responsible for the enthronement of kings, as well as their protectors. There, he appears at the top of the pantheon of Emar. El or Elu, in turn, appears as God king and father of the generation of younger Gods.

In Ugarit, a large temple dedicated to Dagan was found. Apparently, there Dagan was worshipped more as a sea deity, from which his name (dag: "fish") comes, protector of sailors. Proof of this are the several anchors found in his temple, deposited there by sailors as an offering for Dagan having saved them from the storms of the sea.

Therefore, since Dagan and El are the fathers of the Gods in different pantheons, it is understandable that, given the importance that Baal acquired in Ugarit and the region, together with Dagan and El, both were considered the fathers of Baal. Furthermore, it is important to consider that there are many myths where Gods have dual paternity.

Finally, the most convincing seems to be that two parallel myths developed in Ugarit and the region: one that Baal was the son of Dagan and another that Baal was the son of El or Elu, with the probability that the first myth was older.

Seth-Baal

Also in Alalak, Syria, a cylinder seal was found containing an inscription similar to that of Sidon with the phrase: "...Seth-Baal, Lord of..." (Soler, 2021, p. 461). The dating is close to the seal of Sidon, perhaps a little later, between the 13th and 12th centuries BCE. Alalak is west of Aleppo, forming with it, Ebla and Ugarit, a kind of geographic rectangle between the four cities. Unfortunately, the toponym of which Seth-Baal is lord has been damaged. Perhaps it was Ugarit, Lebanon or Byblos.

Several records have been found, mainly on the Mediterranean coast and in Egypt, that relate Baal to the Egyptian god Seth or vice versa. In fact, Baal sometimes appears with Egyptian characteristics. This is the case of the famous statuette found in Ugarit, in the 1929 excavation by Claude Schaeffer. The statuette was found in stratum II, which places it between the 15th and 8th centuries BCE.

There Baal appears with lightning and thunder in his hands and wearing an Egyptian crown. Or, the bronze statuette of Baal seated on a throne, similar to El, found in Hazor in 1996, where Baal appears in Egyptian clothing.

Um dos registros mais antigos da costa mediterrânea que relacionam Baal e Seth é o selo de escarapóide encontrado na Sidônia. Este selo contém uma inscrição em hieróglifo que diz: "Sadok-Re, amado de Seth-Baal, Senhor de Lay" (Soler, 2021, p. 461). A datação do selo não é segura. É possível que seja por volta do século XV AEC (Goldwasser, 2006, p. 123).

There is some doubt as to the association of Baal with Seth and Baal with Horus in Egypt, which seems to have occurred at the same time and in a similar way. This inconsistency is perhaps understandable if it is understood that Baal-Horus was more associated with popular religion, while Baal-Seth was more linked to royal circles or vice versa.

Sílvia Schröer, when referring to the association between Baal and Seth, states that "Basically, however, Baal, similar to El, is not a proper name, but a title that was associated with a certain God by the local population, but as such did not make the identification visible".

However, the safe assertion that Seth is Baal is still an open debate. The problem lies in the translation of the sign (hieroglyph) of the inscriptions that identifies Seth, whether it refers to the divinity itself or whether it is an epithet. Porzia disputes the assertion that Seth is Baal. For Porzia, this assertion would be an academic creation introduced by Keel and Uehlinger, since the name Baal-Seth, sometimes Seth-Baal, does not appear on the seals or papyri and stelae.

The hieroglyphic sign (Seth's animal) that identifies Seth would be a "Sethian" determinative, which precedes the name of Baal, a kind of presentation card to place Baal, a foreign God, within the divine sphere dominated by Seth. Therefore, it would not be a fusion of two deities, or a religious syncretism, Baal-Seth, but only Baal.

Porzia's position makes sense, because Seth was not a rain god, since in Egypt the rains only reached a strip of the Mediterranean. The rest of the land's fertility depended on the overflow of the Nile River, caused by the melting of snow in the mountains of North Africa.

Finally, if Porzia's argument is correct, it further reinforces the power of expansion of the cult of Baal throughout the Levant and Egypt.

Baalsamem

Around the beginning of the first millennium BCE, a god named Baalsamem (Baal of the sky) also appeared in the region of Phoenicia (Sumur, Byblos, Tyre and Qatna). His relationship with the weather (rain, storms, floods, fertility, etc.) is not very clear. It seems that his attributes were more related to the cosmos, as well as to the care of royal affairs, with some similarity to the god El.

It is difficult to know whether Baalsamem is an extension of the cult of Baal or whether he is an extension of the cult of Hadu or whether he is a new God of the Phoenician pantheon who only appears from the first millennium BCE onwards. Perhaps one could, at the level of supposition, draw a timeline as follows: in the beginning there would be the Hurrian and Hittite God Teshob, then Hadu of Aleppo, then Baal-Hadu, and then Baal and finally Baalsamem.

In the Ancient Near East, a sky god has been known since the Bronze Age, but not under the name Baalsamem. It was only at the end of the first millennium BCE, around the second century BCE, that a Roman temple dedicated to Baal-Shamen or Baalsamem was found in Palmyra. Everything indicates that this god is the same Phoenician Baalsamem.

There was only a small change in the final consonant of the name. The final "m" changed to "n"s. In other words, it is likely that the cult of Baalsamem migrated from Phoenicia to the city of Palmyra in Mesopotamia towards the end of the first millennium BCE.

There would still be other qualitative attributes that Baal began to receive from his expansion in the Levant that deserve to be addressed. This is the case, for example, of Baal-Zebub or Baal-Zebul, who, according to 2 Kings 1:26, was worshiped in the coastal city of Ekron, neighboring Israel. Or of Baal-Berit, who, according to Judges 8:33; 9:4,46, was worshiped in Shechem.

According to Niehr, there is no evidence that there was a cult of Baalsam in Israel and Judah. The fact that there was a widespread cult of Baal in Israel, Judah and the region does not mean that this cult can be directly projected onto Baalsam. They are two distinct Gods. The cult of astral deities present in biblical texts, such as in 2 Kings 22-23, is not related to Baalsam.

Likewise, the title "God of Heaven" given to Yahweh, for example, in the book of Ezra, in the post-exile period, is not related to Baalsam and is probably an influence of Persian theology.

However, this is a subject to be explored in greater depth in other research. What we want to record with our analysis here is that: a) The origins of Baal, as God of time, must be sought in Aleppo. That is, Baal is the transculturation in Ugarit, Phoenicia and the region of the God Hadu of Aleppo, first as Baal-Hadu and then only Baal; b) The origins of Baal, as only Baal, without qualitative, must be sought in Ugarit, Phoenicia and the region.

Baal in Israel and Judah

As shown, from Ugarit and later along the entire Mediterranean coast, the cult of Baal expanded throughout the Levant. Kingdoms such as Israel, Judah, Edom, Moab, etc. were not exempt. It is not our objective here, however, we consider it relevant to make a brief mention of the cult of Baal, specifically in Israel and Judah, based on the biblical accounts to show the importance that Baal had within the Yahwist domain.

One way to attest to the antiquity of the Baal cult in Israel and Judah is to look at the place names (Levin, 2017, p. 203-222). In the Bible there are several mentions of places that bear the name of Baal. Let's look at some:

Baal-Safon (Ex 14,2. 9; Nm 33,7); Baal-Meon (Nm 32,38; Js 13,17; Jr 48,23; Ez 25,9; 1Ch 5,8), a site that is also mentioned on the Mesa stele, in line 9 (KAEFER, 2006, p. 171-172); Baal-Gad (Joshua 11:17; 12:7; 13:5); Baalah (Js 15,9. 10. 11. 29; 1Ch 13,6); Bealot (Joshua 15:24; 1Ki 4:16); Baalat-Beer (Joshua 19:8; 1Chr 4:33); Baalat (Js 19,44; 1Rs 9,18; 2Ch 8,6); Baal-Hermon (Jz 3,3; 1Ch 5,23); Baal-Tamar (Jz 20:33); Baal-Perazim (2Sm 5,20); Baalei-Judah (2Sm 6:2); Baal-Hazor (2Sm 13,23); Baal-Shalishah (2Rs 4,42); Baal-Hamón (Song 8:11).

In addition to the Baal place names found in the Bible, according to 1 Kings 16:32, there was also a temple of Baal in Samaria, built by Ahab, who had married Jezebel, daughter of Ethbaal, king of Sidon. This Baal is usually identified as the Baal Melearth of Tyre (1 Kings 18). However, not only in Samaria, but also in Jerusalem, according to 2 Kings 11:18 and 2 Chronicles 23:17, there was a temple of Baal.

In short, it seems to us that it is not necessary to go into detail to demonstrate the popularity of the cult of Baal in Israel and Judah, not only from the biblical accounts, but also from what archaeology proves. It is understandable, therefore, that even in Israel and Judah, Baal was much more popular than Yahweh himself, especially in its initial phase, as demonstrated, for example, by the book of Hosea.

Conclusion

While Hadu was primarily characterized as the God of storms and floods, Baal was primarily characterized as the God of fertility, the one who controlled the rains, without, however, ceasing to exercise them as well. The growing popularity of Baal gave rise to several myths about him. Among these, that Baal is the son of two different Gods: "son of El" and "son of Dagan". Both "fathers" were the supreme deities of two distinct pantheons.

In Upper Mesopotamia, one of the oldest and most popular gods of time was Hadu of Aleppo. With the expansion into Lower Mesopotamia, Assyria and Babylon, already entering the Iron Age, Hadu underwent some name variations: Haddu, Hadda, Hadad, Addu, Adad. Around the middle of the second millennium BCE, the cult of Hadu also spread to the Syro-Palestinian coast, with the epithet "Baal", "Baal-Hadu".

The epithet Baal was common in several deities of the Ancient Near East. It was used to designate a qualitative aspect of the deity, "lord of...". However, on the Syro-Palestinian coast the epithet would end up replacing the deity itself. In other words, Hadu became Baal. The "new" God would differ somewhat from the "old" one.

Baal's expansion and popularity reached Egypt, where he was associated with Seth, as the god Seth-Baal or Baal-Seth. However, in important coastal cities, around 1000-900 BCE, such as Tyre and Byblos, Baal received other epithets, such as Baalsamem "Baal of heaven".

From the coast of Phoenicia, Baal also spread to Mesopotamia, where a temple from the 2nd century BCE dedicated to Baalsamem was found in the city of Palmyra. Baal was also worshipped under other attributes, such as Baal-Zebub of Ekron, Baal-Berit of Shechem, etc. In short, there is extensive evidence, both literary and archaeological, of the widespread expansion of the cult of Baal throughout the Levant.

Returning to Pella, the subject with which we began this research and with which we wish to conclude it. We said, based on the information provided by archaeologists, that the temple excavated in Pella belonged in the first phase (1800-1450) to El; in the second phase (1450-1000) to Baal; and in the third phase (1000-800) to Baal-Seth. We also said that the dedication of the temple to El, in the first phase, was not very certain.

Given the process of transformation that the cult of Baal underwent in the Levant, as we have demonstrated, we suggest that instead of El, in the first phase, the temple of Pella was dedicated to Hadu. This possibility is based on the fact that the change in cult from El to Baal does not fit, due to the different characteristics of the two Gods.

However, from Hadu to Baal is perfectly possible, since the characteristics of both Gods are very similar. Therefore, the temple of Pella, in our understanding, is a perfect illustration to demonstrate the origin of Baal, as an extension of the God Hadu, and its expansion throughout the Ancient Near East, receiving new attributes.

Fonts

ALLON, Niv. Seth is Baal — Evidence from the Egyptian Script. JSTOR, v. 17, p. 15-22, 2007.

AYALI-DARSHAN, Noga. Baal, Son of Dagan: In Search of Baal’s Double Paternity. Journal of the American Oriental Society, v. 133, n. 4, p. 651-657, 2013.

BOURKE, Stephen. Cult and Archaeology at Pella, Jordan. Excavating the Bronze Iron Age Temple Precinct (194-2001). Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales*, v. 137, p. 1-31, 2004.

FLEMING, E. Daniel. The Installation of Baal’s High Priestess at Emar: A Window on Ancient Syrian Religion. Michigan: Scholars Press, 1992.

FREVEL, Christian. The Enigma of Baal-Zebub: A New Solution. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, v. 299. Leuven: Peters Publishers Leuven, p. 202-237, 2023.

GONNELLA J., KHAYYATA W., KOHLMEYER K. The Citadel of Aleppo and the Temple of the Weather God - New Research and Discoveries. Münster: Rhema, 2005.

KAEFER, José Ademar. Ugarit - Rash Shamra: Its History. Caminhando, v. 27. São Bernardo do Campo: Editeo, p. 1-19, 2022.

Journal Pislis Prox., Theol. Past., Curitiba: PUCPRESS Publisher, v. 16, n. 3, p. 395-408, 2024.

KAEFER, José Ademar. A Free People Without Kings – The Role of Gn 49 and Dt 33 in the Composition of the Pentateuch. Spanish Biblical Association / 44. Estella: Verbo Divino Editorial, 2006.

KEEL, O. On the Identification of the Falcon-Headed on the Scarabs of the Late 13th and 15th Dynasties. In: O. KEEL, H. KEEL-LAU, and S. SCHRÖER (eds.), Studies on the Stamp Seals from Palestine/Israel, OBO 88. Fribourg/Göttingen, 243–280, 1989.

LETE, Gregorio del Olmo. Myths and Legends of Canaan According to the Ugaritic Tradition. Madrid: Ediciones Cristiandad, 1981.

LEWIS, Theodore J. The Identity and Function of El/Baal Berith. Journal of Biblical Literature, v. 115, n. 3, p. 401-423, 1996.

LEVIN, Yigal. Baal Worship in Early Israel: An Onomastic View in Light of the “Eshbaal” Inscription from Khirbet Qeiyafa. A Journal for the Study of the Northwest Semitic Languages and Literatures, v. 21, p. 203-222, 2017.

NIEHR, Herbert.nBaalsamem: Studies on the Origin, History, and Reception History of a Phoenician God. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, 123, Leuven/Paris, 2003.

ORNAN, Tallay. “Let Ba`al Be Enthroned”: The Date, Identification, and Function of a Bronze Statue from Hazor. Journal of Near Eastern Studies, v. 70, n. 2, p. 253-280, 2011.

POLCARO, Andrea; GONZÁLES-GARCÍA, A. Cézar; BELMONTE, Juan Antonio.** The Orientation of the Bronze Age Temple of Pella, Jordan: The Dying God of Baal and the Rituals of the Summer Solstice. In: Ivan Spraje; Peter Pehani. Ancient Cosmologies and Modern Prophets. Ljubljana: Slovene Anthropological Society, 2013.

PORZIA, Fabio. Religion(s) in Seals - Old and New Challenges. Near Eastern Archaeology, v. 87, n. 1, p. 4-13, 2024.

RÖMER, Thomas.nThe Origin of Yahweh - The God of Israel and His Name. São Paulo: Paulus, 2016.

SANTOS, João Batista Ribeiro. The Iconographic Diffusion of Religion – Iconography and Policies of War and Visual Representations in the Ancient Near East. São Paulo: Alameda Editorial House, 2023.

SCHAEFFER, Claude Frédéric-Armand. Ras-Shamra 1929–1979. Collection Maison de l’Orient (CMO), Hors série n. 3. Lyon: Maison de l’Orient Méditerranéen, 1979.

SCHNEIDER, Thomas. A Theophany of Seth-Baal in the Tempest Stele. Ägypten und Levante/Egypt and the Levant, v. 20, p. 405–409, 2010.

Journal Pistis Prox., Theol. Past., Curitiba: PUCPRESS Publisher, v. 16, n. 3, p. 395-408, 2024.

SCHRÖER, Silvia. The Iconography of Palestine/Israel and the Ancient Near East - A Religious History in Images. Volume 4, Bern: Schwabe Verlag, 2018.

SCHWEMER, Daniel. The Weather God Figures of Mesopotamia and Northern Syria in the Age of Cuneiform Cultures. Materials and Studies Based on Written Sources. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2001.

SCHWEMER, Daniel. The Storm-gods of the Ancient Near East: Summary, synthesis, recent studies. New York, Leiden: Brill, 2008.

SOLER, S. The Origins of the Seth-Baal Syncretism. Seth and the Storm According to the Classifiers of the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom. Monographica Orientalia, Barcino, v. 16, p. 461-475, 2021.

YON, Marguerite. The City of Ugarit at Tell Ras Shamra*. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2006.

WYATT, Nicolas. The Baal au Foudre Stela and Its Historical Context. Ugarit-Forschungen, v. 49. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, p. 429-430, 2018.

#demonolatry#demon work#demon worship#deity work#baal#baal devotee#lord baal#demonology#witchcraft#paganism#witchblr

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear Goyim Who Think Judaism and Israel Aren't Connected,

They absolutely are. The holy land of Judaism is Israel, and no amount of fiddling will get around that inconvenient fact.

Even throughout our exile, Jews clung to the idea of Israel, the holy land. Even after the Romans slaughtered us, sold us slaves, expelled us, and tried to erase our connection to the land (a propaganda that you seem to have swallowed), even after their successors tried to keep us from coming back (not that all of us left; some stayed, stayed through persecution and massacre and more), we clung to it.

Israel is the holy land. And, in the words of Jefferson, "To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world."

The central prayer in Judaism, Shema Yisrael, uses "Israel" as a synonym for the Jewish people.

We pray facing Jerusalem.

In old texts, it is incredibly common to see Israel used as a synonym of Jews. Thus in Nathan Ausubel's 1948 Treasury of Jewish Folklore we see rabbis referred to as the "Sages of Israel" (in a discussion of why Jerusalem was destroyed, no less!), and the saying "Am Yisrael Chai" literally translates as "the People of Israel live!"

At the end of the Passover seder, we say, "L'shana haba'a b'Yerushalayim" (Next year in Jerusalem).

Psalm 137: "על נהרות בבל שם ישבנו גם־בכינו בזכרנו את־ציון". Or, "Al naharot bavel sham yashavnu gam-bakhinu bezakhernu el-tzion" (Tzion, Zion, being another name for the land). "By the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept as we thought of Zion." It continues, "How can we sing God's song in a foreign land? / If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning."

There are many rules that only apply when in Israel.

Observant Jews say, "ברוך אתה יי בונה ירושלים" (Barukh atah Adonai boneh Yerushalayim), or "Blessed are you, God, builder of Jerusalem" three times daily.

My very short Haftarah portion, which is assigned based on when you were born and thus not something I had control over, mentions Israel ("vegoaleikh kedosh Yisrael elohei khol-haaretz yikarei" - my brain can't stop singing it, Isaiah 54:5), in the context of God being the "Holy One of Israel". The prayer before the Haftarah reading includes the line "uvyisrael amo" (for Your [God's] people Israel). Again, my Haftarah portion was not in any way special; it was five verses. The translation of the part I read is all of 153 words. And yet it still mentions Israel. (The Hebrew, by the way, is 71 words.)

In short: by denying Jewish claims to Israel as the holy land (kedushat ha-aretz), you are erasing an indigenous people's history and implicitly accepting the narrative of settler-colonialist genociders who sought to make it as though the people whose land they were taking and who they were selling as slaves were not tied to the land and did not have any ancestral connection. Your claims are entirely false.

Sincerely,

Your Neighborhood (Non-Israeli, But Y'all Are Making Me Want To Consider Aliyah) Jew

*Extended footnote on the terminology used: There are two major (and definitely non-dialectical) indigenous languages in the region that still survive to some extent: Hebrew and Aramaic. (Other languages existed in the region - Phonecian and Ugaritic, for instance. But they didn't survive.)

The indigenous name for the region in Aramaic and Hebrew is ישראל, pronounced, roughly, "Yisrael". Via the process of translation, that became "Israel". The other common name for the region, Palestine, derives from the Roman Palestina, a relic of their campaign to destroy Jewish connection to the region by renaming it after a small Greek group who were long since gone, the Philistines. I am using the name the indigenous people of the region used, rather than the name of a colonial occupier trying to pretend like the indigenous people were unconnected to the land.

#jumblr#jewblr#jewish#antisemitism#jewish tumblr#israel#judaism#jews are indigenous to israel#israel is the indigenous name of the region#well technically yisrael but y'know#it's shema yisrael not shema [diaspora location]#fuck colonizers#fuck colonization#decolonization#the ancient romans were genocidal colonialist assholes#and people are still buying their propaganda#MILLENNIA LATER#and the funny thing is these people are the same people who do land acknowledgments and say whose land they're on#and then they unquestioningly buy into colonialist bs#either they're the world's stupidest people or they're antisemites#(that was an inclusive or fyi)#(they can be both)

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, You Wanna Know About?: The Evil Eye

The concept of the “evil eye” exists in virtually every culture worldwide, as do amulets such as the nazar and hamsa. It's a fundamental part of most folk groups' magic and culture, which is why we use it as a symbol for our server. But what do we know about this concept and the symbols and practices surrounding it? Let’s take a second and explore.

What Exactly Is The Evil Eye?

In simplest terms, the evil eye is “a curse transmitted through a malicious glare, usually one inspired by envy.” [1] It's believed that this glare can cause misfortune, illness, injury, death, and general misery. [3] Pregnant women, infants, young children, and animals are thought to be especially susceptible. [4]

The Evil Eye’s First Appearance

Historians are unsure of the exact date the evil eye and amulets used to ward them off were invented, however, we can find examples going as far back as ancient Mesopotamia. Texts have been found in Ugarit (located in modern-day Syria) attesting to the concept until roughly 1180 BC. [2] According to Dr Nese Yildiran, “The earliest version of eye amulets goes back to 3,300 BC … The amulets had been excavated in Tell Brak, one of the oldest cities of Mesopotamia – modern-day Syria. They were in the form of some abstract alabaster idols made with incised eyes.” [1]

The Evil Eye Travels

Various things across history such as trade, travel, colonization, and immigration have caused the evil eye to travel the world. It spread through the SWANA region at first, but soon traveled to all continents worldwide: “[The evil eye has] occurred in ancient Greece and Rome, in Jewish, Islamic, Buddhist, and Hindu traditions ... [and in] Indigenous, peasant, and other folk societies.” [4] Historians have found it difficult to trace exact lines of transmission of the idea, but it notably seemed to spread rapidly among the common folk or working class. [5] It wasn't long before its presence became known across all continents, though it has always varied across time and space. For example “In Roman times, not only were individuals considered to possess the power of the evil eye but whole tribes…were believed to be transmitters of the evil eye.” [6] This is very different from how the evil eye exists in the current regions of the previous Roman Empire, as these tribes no longer exist.

It Came With The Amulets!

One of the earliest amulets associated with the evil eye is the nazar. Its name comes from the Arabic “نَظَر” (naðˤar) meaning “sight,” with many other languages adopting this term or creating their own. [7] The blue eye-shaped bead most commonly associated with this particular amulet is “made of a mixture of molten glass, iron, copper, water, and salt, ingredients that are thought to shield people from evil.” [8] Its blue color may be because “blue eyes are relatively rare [in the SWANA region], so the ancients believed that people with light eyes, particularly blue eyes, could curse you with just one look. This belief is so ancient, even the Assyrians had turquoise and blue-eye amulets.” [9] A similar amulet adopted from the nazar is the hamsa, similarly originating in the SWANA region. [10] The two have become perhaps the most widespread and well-known amulets, though they are certainly not the only ones.

Evil Eye Across Cultures & Religions

NOTE: this is not an exhaustive list, but a jumping off point.

Judaism: The evil eye can be found across various Jewish literature, from the Tanakh to the Talmud, and even books like Pikeri Avot. [11] It’s known best as the “ayin hara” which is Hebrew for the evil eye, though it may have different names across diaspora (for example, in Jewish-Spanish languages like Ladino it might be known as “Mal de Ojo”) [12] There are various customs to protect one from the evil eye across the Jewish diaspora, such as neckbands worn by boys for their brit milah, in the regions of Alsace, Southern Germany, and Switzerland just to name one. [13] One of our Jewish server members, Yosef, says “I'm Jewish and have been all my life ... my family is eastern European and we have gone to orthodox shul and (no) evil eye and other related symbols are prevalent in my family's practice along with the practice of my synagogues ... as such I constantly carry around the symbol”

Islam: The evil eye as a concept in Islam, known as the “al-ʽayn” is common. It's believed to destroy one's good fortune or cause illness. [14] Various phrases including “Mashallah” (God has willed it) are used to ward off the evil eye – “The imperativeness of warding this all too evident evil eye off is common among local communities. Not only did the absence of a “mashallah” tempt fate but it is also believed certain individuals have the power to conjure up the dark forces of the evil eye.” [15]

Italy: The evil eye in Italian is known as the “mal’occhio.” [16] In some regions, the cornicello ("little horn") is an amulet used to ward off the evil eye. It comes from Naples and it’s usually made of red coral and pepper shaped. [17] According to Antonio Pagliarulo, “some families, depending on the region of Italy from which they come, will pin the amulet to a baby's clothing either immediately before or immediately after his or her baptism.” [18]

Ireland: In Ireland, the evil eye is known as “Droch-shúil.” [19] There are a few various Irish folktales about the presence of the evil eye that warn of its dangers. One example is the tale of King Balor. The tale goes that “Balor was a king of the Formorians, the ancient inhabitants of Ireland (before the coming of the Tuatha Dé Danann). He is often described as a giant with a huge eye in the middle of his forehead. This eye brought death and destruction [onto] anyone he cast his gaze upon. He had gained this power from peering into a cauldron that contained a powerful spell that was being created by some druids. The vapors from the cauldron got into his eye when he looked inside which gave him the power of his deathly gaze. The most memorable instance of Balor using his eye is the story of his death at the battle of Maigh Tuireadh. In this famous battle between the Formorians and the Tuatha Dé Danann, Balor fell in battle at the hands of his own grandson, the pan-Celtic god Lugh, when he thrust his spear (or sling depending on the telling) through the eye of the giant. His eye was blown out the back of his head, turning his deadly gaze on his own men, destroying the forces of the Formorians. A piece of Dindseanchas (meaning lore of places) tells us that the place where his head fell and burned a hole in the ground, later filled with water and became known as “Lough na Suil” or “The Lake of the Eye”. Interestingly, this lake disappears every few years when it drains into a sinkhole. Local mythology says that this happens to ensure that the atrocities of the battle may never be forgotten.” [20]

Germany: In German, the evil eye is known as the “Bölser Blick”, something that is cured by a variety of methods such as red string, prayer, salt, iron, and incense. [21]

Poland: In Poland the evil eye is called "złe oko" or "złe spojrzenie." [23] In some regions, they use amulets known as "czarownica" which are charms often made from herbs, metals, or stones, or specific gestures believed to ward off the evil eye. In many Polish homes, you might find them hanging on the walls. A ‘czarownica’ might also be a necklace with a pendant crafted from amber, which is believed to ward off negative energy. [22] There are also folk tales about the evil eye, such as “an archaic Polish folk tale that tells of a man whose gaze was such a potent carrier of the curse that he resorted to cutting out his own eyes rather than continuing to spread misfortune to his loved ones” [1]

Russia: In Russian the evil eye is called "дурной глаз" or just "сглаз." [23] Some Russians ward off the evil eye by bathing in running water, which carries the negativity away. Fire is also used, with young people jumping over a campfire to remove bad energy. Carrying salt or pinning the fabric of your clothing are also other simple ways to ward off the evil eye. [24]

Mexico: In Mexican culture, the evil eye (el ojo) is thought to be especially prevalent during November around the time of Dia de los Muertos, with children being particularly susceptible. There are various ways a child may get the evil eye such as from a stare of a drunk or angry person, or a person who is "caloroso," or overheated from working out in a hot environment such as under the sun or cooking over a hot stove. [25] Some may use an ojo de venado, or “eye of the deer” as a protective charm, which is only effective if “worn as an amulet around the neck at all times.” [26] As a quote from one of our staff members, Ezekiel: “I was raised in a very Hispanic area so we all wore evil eye bracelets most of the time woven from the flea market… In Mexico or some parts of Latin America, it is called El mal de ojo and it is believed that different colored evil eyes do different things.”

Rroma: The concept of the evil eye also exists amongst the Rromani people. For Rroma in Slovakia, the belief in jakhendar is prevalent, often being diagnosed and cured with jagalo paňi, or ‘coal water’ [27] Rroma in places like Brno are also thought to be particularly susceptible to the evil eye, leading to communities to find members to help protect themselves. According to scholar Eva Figurová, “This role, instead, is appointed to the village shepherd, blacksmith, or other person perceived by the community as gifted with the ability to heal, cure, and ward off the effects of negative forces, whether intentionally or not. Nowadays, among the Roma in Brno, the chanting of the zoči is a common ritual that does not require the presence of a specialist.” [28]

India: In many parts of India, people use a nazar battu to ward off the evil eye, or the buri nazar. [29] Other methods of warding off the evil eye include hanging a drishti bommai [30], mothers spitting on their children [31], or marking them with a black mark on the cheek. [32]

Ethiopia: In Ethiopian culture, the evil eye is known as the "buda." [33] It is thought to be wielded by certain people (i.e. metalworkers) and warded off by amulets created by a debtera, or unordained priest. [34]

Conclusion

This blog post only begins to touch the surface when it comes to the evil eye. The history across time and space is so expensive one can truly dedicate their entire lives to studying and still not know everything there is to know. We sincerely hope that we have provided some perspective and gave some jumping off points for further exploration.

Sources & Further Reading:

Hargitai, Quinn (2018). “The strange power of the ‘evil eye’”. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180216-the-strange-power-of-the-evil-eye. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Pardee, Dennis (2002). "VIII. INCANTATIONS: RS 22.225: The Attack of the Evil Eye and a Counterattack". Writings from the Ancient World: Ritual and Cult at Ugarit (vol. 10). Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 161–166.

Ross, C (2010). "Hypothesis:The Electrophysiological Basis of the Evil Eye Belief". Anthropology of Consciousness. 21: 47–57.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "evil eye". Encyclopedia Britannica, 28 Oct. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/topic/evil-eye. Accessed 3 November 2024.

Gershman, Boris (2014). The Economic Origins of the Evil Eye Belief. American University (Washington, D.C.). Online resource. https://doi.org/10.57912/23845272.v1

Elworthy, Frederick Thomas (1895). The Evil Eye: An Account of this Ancient and Widespread Superstition. J. Murray.

WICC Authors, (2023). Nazar (amulet). https://wicc2023.org/nazar-amulet/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Williams, Victoria (2016). Celebrating Life Customs Around the World: From Baby Showers to Funerlan, p.344.

Lynn, Heather (2019). Evil Archaeology, p.167

Bernasek, Lisa. (2008) “Artistry of the Everyday: Beauty and Craftsmanship in Berber Art” Volume 2 of Peabody Museum collections. Harvard University Press. pg 12. ISBN 978-0-87365-405-0

Ulmer, Rivka (1994). KTAV Publishing House, Inc. (ed.). The evil eye in the Bible and in rabbinic literature. KTAV Publishing House. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-88125-463-1.

Jewitches Blog. “The Evil Eye.” Jewitches, 18 Apr. 2023, jewitches.com/blogs/blog/the-evil-eye. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Birth Culture. Jewish Testimonies from Rural Switzerland and Environs (in German and English). Basel: Naomi Lubrich. 2022. pp. 35–37.

Evil Eye - Oxford Islamic Studies Online.” Archive.org, 2018, web.archive.org/web/20180825110529/www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e597. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

“Mashallah: What It Means, When to Say It and Why You Should.” The National, 22 May 2013, www.thenationalnews.com/lifestyle/mashallah-what-it-means-when-to-say-it-and-why-you-should-1.264001. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

“Mal’occhio | a brief understanding (and offering).” Radici Siciliane, 17 Nov. 2020, www.radicisiciliane.com/blog/malocchio-a-brief-understanding-and-offering. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Melissi, Paolo. The Cornicello: A Traditional Lucky Charm from Naples. 18 June 2021, italian-traditions.com/cornicello-traditional-lucky-charm-from-naples/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Pagliarulo, Antonio. The Evil Eye. Red Wheel/Weiser, 2023. ISBN 978-1-63341-294-1

“Irish Superstitions: The Evil Eye, Fairy Forts, and Lucky Charms.” IrishHistory.com, 14 May 2023, www.irishhistory.com/myths-legends/folk-tales-superstitions/irish-superstitions-the-evil-eye-fairy-forts-and-lucky-charms/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

“The Evil Eye.” Ireland’s Folklore and Traditions, 12 July 2017, irishfolklore.wordpress.com/2017/07/12/the-evil-eye/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Katharina, Anneke. “Boser Blick: Evil Eye in German Folk Magic.” Instagram.com, 2024, www.instagram.com/p/CrO8IIeLMgu/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&img_index=1. Accessed 3 Nov. 2024.

Tobey, Julie. “The Meaning of the Evil Eye in Polish Culture.” Polish Culture NYC -, 7 June 2024, www.polishculture-nyc.org/the-meaning-of-the-evil-eye-in-polish-culture/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Haroush, Alissa. “42 Names for the Evil Eye and Where Did the Evil Eye Amulet Originate.” Alef Bet by Paula, Mar. 2021, www.alefbet.com/blogs/blog/42-names-for-the-evil-eye-and-where-did-the-evil-eye-amulet-originate. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Sorokina, Anna. “How Russians Protect Themselves from Evil Spirits.” Russia Beyond, 3 Nov. 2024, www.rbth.com/lifestyle/331213-protect-from-evil-russia. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Mexico, Na’atik. “El Mal de Ojo, the Evil Eye.” Na’atik Language & Culture Institute, 26 May 2023, naatikmexico.org/blog/el-mal-de-ojo-the-evil-eye. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

“The Evil Eye.” The Atlantic, 1 Oct. 1965, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1965/10/the-evil-eye/659833/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

Hajská, Markéta. “The evil eye – Jakhendar” Factsheets on Romani Culture. https://rm.coe.int/factsheets-on-romani-culture-2-3-the-evil-eye-jakhendar/1680aac373

FIGUROVÁ, Eva. Contemporary signs of magic in the everyday life of Roma minority in the selected areas of Brno, focusing on magical acts like “pokerování” and evil eye. In Individual and Society [Človek a spoločnosť], 2022, Vol. 25, Iss. 3. https://doi.org/10.31577/cas.2022.03.609

Stanley A. Wolpert, Encyclopedia of India, Volume 1, Charles Scribner & Sons, 2005, ISBN 9780684313498

Kannan, Shalini. “Surprises and Superstitions in Rural Tamil Nadu.” Milaap.org, Milaap, 15 Apr. 2016, milaap.org/stories/surprises-and-superstitions-in-rural-tamil-nadu. Accessed 1 Nov. 2024.

John Abbott, Indian ritual and belief: the keys of power, Usha, 1984

George Vensus A. (2008). Paths to The Divine: Ancient and Indian (Volume 12 of Indian philosophical studies). Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, USA. ISBN 1565182480. pp. 399.

Turner, John W. "Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity: Faith and practices". A Country Study: Ethiopia Archived 2012-09-10 at the Wayback Machine. Thomas P. Ofcansky and LaVerle Berry, eds. Washington: Library of Congress Federal Research Division, 1991.

Finneran, Niall. "Ethiopian Evil Eye Belief and the Magical Symbolism of Iron Working. Archived 2012-07-12 at the Wayback Machine" Folklore, Vol. 114, 2003.

#folk magic#folk practice#folk practitioner#folk witchcraft#magic#witch#witch community#witch stuff#witchblr#witchcraft#the evil eye#evil eye#nazar#amulet#enjoy!#long post

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

🦁🧿🌙 Pre Islamic Goddesses 🌙🕋☀️

Al-Lāt, syrian and arabian goddess of destiny and the city Mecca, Lady of the temple, her Name means „Goddess“ and is the female version of „Allah“, represented by the lion, married to Bel, prototype for the greek goddess of wisdom, Athena, her followers took her figures with them in battles, one of the three goddesses of Mecca, the kaaba 🕋 was build for them, her shrine was a red stone cube

Al-Uzza, syrian and arabian goddess of destiny and the venus, one of the three goddesses of Mecca, the youngest of the them, she got worshipped at the kaaba 🕋 and was the greatest idol of the Qurayash who controlled Mecca, they used to journey to her, offer gifts and sacrifices, her shrine was a white stone cube

Anat, syrian and egyptian goddess of war and protector of wild animals, goddess of love and eternal virgin, mother of all, life and death

Ašera, syrian-canaanite sea goddess

Astarte, semitic goddess of love and fertility

Aštoreth, ugarit goddes, bride of the tyrrhenian sea,

Athirat, ugarit sea and sky goddess, lady of the sea, producer of gods, lady of gods

Ereškigal, sumerian goddess of the underworld and Inannas older sister, she can kill with her eyes, snake goddess, she is naked, with eyes out of stone and black hair, sometimes she wears a lions head and her palace is out of lapislazuli

Han-Ilat, northern arabian big goddess

Inanna, sumerian goddess of war, sex, love and the venus, lady of the sky, lady of all houses, city godess of Uruk, female leader goddess, her symbols are the moon and the star

Išhara, syrian underworld goddess

Ištar, babylonian and mesopotamian goddess of war, sex and the venus, most important diety in the ancient world of middle east, many goddesses are versions of her symbols are lions and the star

Ištar of Arbela, assyrian goddess of war

Kiriša, elamic mother goddess with an aspect of war, Lady of the sky, benefactor of the kings, mother of gods

Kulitta, servant of Ištar/Šauška

Lamaštu, babylonian sky goddess, demon with lion head who eats children and makes people sick, kills innocent people, always around rotten and filthy stuff like feces and dead animals,

Lilithu, sumerian goddess of mischief, misery, the night and the storm who lives in ruins, seduced men and stole children

Manat, arabian goddess of the moon, the venus, destiny, and one of the three big goddesses of Mecca. Her shrine was a black stone cube, pilgrims used to cut their hair at her shrine to conplete their journey to the kaaba 🕋

Nammu, sumerian creator goddess of the primordial sea, created together with her son Enki the first men out of clay

Nanše, sumerian goddess of water sources, and brooks, divination, dream interpretation and the holy order, most important goddess in Lagaš, Mother of her daughters Ninmah and Nunmar

Ninatta, servant of Ištar/Šauška

Ningal, mesopotamian goddess, wige of the moon god Nanna, great queen, high lady, lady, star of the prince, sevenfold light, treasured, goddes of the city Ur, goddess of epiphany, mother of Inanna and the sun god Ut

Ninmah, sumerian goddess of midwivery

Ninsianna, babylonian goddess, rust red lady of the sky, pure and sublime judge, sometimes war goddes with a scimitar and a lion headed club, she is the goddess of venus and she wears a star on hear horned crown

Ninšubur, sumerian goddess and holy servant of Inanna, Lady of the servants, been very popular because she was seen as a messenger between men and gods, seen as personal goddess by some kings, guardian who fights with the weapons of air and the sky

Nisaba, sumerian goddess of corn, goddes of writing texts, science and architecture, sister of Nanše and Ningirsu

Pinikir, elamian, later mesopotamian, hurrian and hittian mother goddess

Šauška, hurrian goddess of love, war, incantations and healing

Tiamat, babylonian goddess of the sea, embodiment of salt water, married to Abzu the embodiment of fresh water

Tunit, punish goddess of fertility and guardian of cartago, virgin mother of Baal, who gives him every year new life, her attributes are pomehrenates, figs, ears of corn and the dove

#al-lat#allat#aluzza#uzza#anat#ašera#ashera#astarte#aštoreth#ereshkigal#ereškigal#Han-Ilat#Hanilat#Inanna#Išhara#ištar#ishtar#kiriša#lamaštu#lilithu#al-manat#manat#nammu#Nanše#Ninatta#Ningal#Ninmah#Ninsianna#Ninšubur#Tiamat

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! absolutely love your work but havent read all of it yet, if youve already covered this feel free to ignore this, but I was wondering if you knew anything about Hushbisha? she is mentioned in the epic of gilgamesh as part of enkidus funeral rights and a search on google only gives gilgamesh pdfs or "the tablet of destinys" which idk. ill keep doing research on my own but just wanted to ask in case you knew anything. thank you for your time!!

Hushbisha (literally “its horror is good”; Irene Sibbing-Plantholt, Visible Death and Audible Distress: The Personification of Death (Mūtu) and Associated Emotions as Inherent Conditions of Life in Akkadian Sources, p. 339) does not physically appear as a character in the Epic, but she is indeed mentioned when Gilgamesh mourns Enkidu’s death and makes offerings to various deities to guarantee he’ll be welcomed warmly in the underworld (tablet VIII, lines 159-161; translation via Andrew R. George, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts, p. 661):

The full list of invoked deities shows some similarities with similar passages in Death of Ur-Nammu and Death of Gilgamesh (an earlier “standalone” Gilgamesh myth, I will cover it in more detail soon-ish) but the minor underworld deities invoked don’t overlap fully; Hushbisha appears in the Death of Ur-Nammu as well, though (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 489). In both cases, she is placed directly after Namtar, which is presumed to reflect the view they were spouses (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 859). This is presumed to be a fairly old tradition, going back to the Ur III period at least (Jacob Klein, Namtar in RlA vol. 9, p. 143). The only exception from it I’m aware of is the Underworld Vision of an Assyrian Prince, where Namtar’s spouse is Namtartu, literally the feminine form of his own name (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 859).

Hushbisha’s title from the Epic of Gilgamesh is also attested in the exorcistic incantation Gattung III, line 65 (Ḫušbiša by Wilfred G. Lambert in RlA vol. 4, p. 522). Other attestations are not very numerous, and most provide no information about her beyond establishing she is Namtar’s wife. A brief survey of these I dug up in sources I have access to under the cut.

An = Anum tablet V, line 196, directly described as Namtar’s wife and placed with him in the court of Ereshkigal (Wilfred G. Lambert, Ryan D. Winters, An = Anum and Related Lists, p. 196); while this not explicitly stated, since (He)Dim(me)ku is described as Namtar’s daughter in the same source it is presumed she was her mother (idem, p. 339)

Old Babylonian An = Anum forerunner (aka “Genouillac list”), line 409, directly after Namtar (idem, p. 50)

the incantation series Udug-hul, in sequence with Bitu (the doorkeeper of the underworld) and Dimku (who is, puzzlingly, explicitly not the daughter of Namtar in this case); once again, directly identified as Namtar’s wife (Markham J. Geller, Healing Magic and Evil Demons. Canonical Udug-hul Incantations, p. 189)

the exorcistic incantation Gattung II, as one of the numerous invoked underworld deities - the full sequence consists of Lugal-irra, Meslamtaea, Nergal, Ereshkigal, Ninazu, Ningirida, Ningishzida, Azimua, Geshtinanna, Namtar, Hushbisha, Hedimku, Nirda (deified punishment), Bitu, Sharsharbid (the “butcher of the underworld”), Etana, Gilgamesh, Lugalamashpae (some sort of disease demon) and Ugur (Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 129).

The only other tidbit worth bringing up is that Irene Sibbing-Plantholt suggested that the fact Namtar acquired a family consisting of a wife, daughter and mother (Mardulanki) reflected the development of the idea that he can be countered with incantations or even reasoned with; she contrasts that with functionally similar Mūtu (“Death”; the name is a cognate of more famous Ugaritic Mot), who didn’t undergo similar humanization (Visible Death…, p. 338-339).

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two myths from ancient ʾUgarit: ʿAnat Binds the Dragon and ʿAshtart the Huntress

An early eighth century BCE stamp seal discovered at Tel Hazor depicting a Hero-Deity slaying a seven-headed serpent. Source: Uehlinger, Christoph. “Mastering the Seven-Headed Serpent: A Stamp Seal from Hazor Provides a Missing Link Between Cuneiform and Biblical Mythology”. Near Eastern Archaeology 87:1 (March 1, 2024), pp. 14–19. https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-258353.

Hey folks, these are my versions of some fragmentary myths from the ancient Ugaritic corpus. A lot of what I used to fill in the blanks is based on other Ugaritic literature and I'm sure those with a lot more experience than me reading them will notice pretty quickly.

The first text, KTU 1.83, has been subject to quite some discussion among scholars in the past. I present it here to feature 𒀭Maiden ʿAnat's slaying of the monstrous serpent Lotan (cf. Biblical “Leviathan”) and the Sea-God 𒀭Yam's other cohorts as She recalls in Tablet 3 of Baʿal. I primarily used the “provisional” translation of this text provided in Religious Texts From Ugarit (2nd edition, 2002, pp. 368–69) by Nathaniel Wyatt with credit as well to Wayne T. Pitard's edition titled “The Binding of Yamm” (J. Near East. Stud. 57(4):261–80, Oct. 1998) and Simon B. Parker's translation as “The Binding of a Monster” in Ugaritic Narrative Poetry (1997, pp. 192–93).

Next is KTU 1.92, somewhat more coherently narrating a hunt of 𒀭Lady ʿAshtart and 𒀭Lord Baʿal's passion for Her. My interpretation of this text has some more draw from general Semitic mythology and symbolism. Wyatt (pp. 370–74) is again my main source with further reference to Baruch Margalit's interpretation of the obverse text (Part I) as “A [sic] Ugaritic Theophagy” (Aula Orientalis 7:67–80, 1989).

I hope you enjoy these take on ancient stories of the Goddesses and Gods of Canaan 💛

Anat Binds the Dragon

When Lotan the Shifting Serpent burst forth with one lip to Heaven and one lip to Earth,

it was unleashed by 𒀭Desire, Beloved of 𒀭ʾEl, the 𒀭Rogue, the Bullock of 𒀭ʾEl,

by 𒀭Fire, the Bitch of 𒀭ʾEl, 𒀭Flame, Daughter of 𒀭ʾEl,

they came out from ʿArsa;

with its fangs it thrashed the Sea to foam,

with its forked tongue it kissed the Heavens,

with its split tail it thrashed the Sea to foam.

𒀭ʿAnat snared the Dragon on high,

She bound it on the heights of Lebanon.

Towards the desert shall You be scattered, O 𒀭Yam!

To the multitudes shall You be crushed, O 𒀭Nahar!

You shall not see: You shall foam up!

𒀭ʿAnat will strike You down, O 𒀭Yam, Beloved of 𒀭ʾEl,

slay You, O 𒀭Nahar, the Great God.

She snared Tunnan and vanquished him,

struck down the Writhing Serpent, the Tyrant of Seven Heads;

She strikes down 𒀭Desire, Beloved of 𒀭ʾEl,

vanquishes the 𒀭Rogue, the Bullock of 𒀭ʾEl;

She strikes down 𒀭Fire, the Bitch of 𒀭ʾEl,

makes an end of 𒀭Flame, Daughter of 𒀭ʾEl;

𒀭Maiden ʿAnat battles for the Silver,

She seizes by force the Gold.

ʿAshtart the Huntress

Scribal note: Of Thabil.

Part I. The Hunt of ʿAshtart

𒀭ʿAshtart went out on a hunt,

She headed into the wild grazeland.

She polished the tip of Her Spear,

the Stars and the Crescent of the Moon favored Her bounty.

And lo! The hills began to shake,

the abysmal waters boiled up,

as a herd of antelope dashed off to the Marsh,

the swamp where buffalo graze.

She unsheathed Her Spear.

𒀭ʿAshtart sat and hid in the Marsh,

at Her right She placed Her dog Crusher,

at Her left Boomer.

She lifted up Her Eyes and looked:

a drowsing Hind She espied,

a Bull eating in the pond She saw!

Her Spear She grasped in Her Hand,

Her Lance in Her Right Hand.

She hurled the Spear at the Bull;

She felled 𒀭Baʿal, Servant of 𒀭ʾEl.

As She went home She thought:

She would feed Him to 𒀭ʾEl the Bull, Her Father,

She would feed Him to the Sons of 𒀭ʿAshirat for dinner.

She would feed Him to 𒀭Yariḫ's indomitable gullet,

She would serve the dinner to 𒀭Kothar-wa-Khasis, 𒀭Heyan the Ambidextrous.

Thereafter, when 𒀭ʿAshtart arrived at Her House,

She set away Her Implements of the Hunt.

Part II. Baʿal and ʿAshtart

𒀭ʿAshtart asked after the Guardian of the Vineyard

for She sought 𒀭ʾEl the Bull, Her Father, Master of the Vineyard.

She stood about the vines clad in a Veil of Linen,

donning an Aegis of Cypress, Lady 𒀭ʿAshtart,

the Kilt She wore catching the Splendor of the Male Stars,

Her Sash the Magnificence of the Female Stars.

Once the Maiden had changed,

𒀭Baʿal longed after Her;

the Valiant One wondered of Her Beauty!

𒀭Baʿal the Victorious desired to know Her by heart.

He was glad to see Lady 𒀭ʿAshtart, but She was frightened by the Son of 𒀭Dagan.

He heard Her cry peal across the Valley and the Coast,

past the Two Ṣurs, beyond Ṣidun and Gebal,

echoing off ʾAlashiya and Caphtor,

Ṣapon and Lebanon brought low, Lalu and ʾInbubu brought high,

She lifted up Her Voice to the Guardian of the Vineyard,

𒀭Baʿal-Hadad called out:

“Seventy-seven times You have caught My Eye,

“eighty-eight pierced My Heart!”

But the Guardian answered Him:

“The City is guarded against Your Flesh.

“Do not return to the Court of the Children of 𒀭ʾEl!”

Thereafter, 𒀭Baʿal went up to 𒀭Ṣapon, His Holy Stronghold,

crushed the Heart of 𒀭Baʿal the Prince for want of comfort of the living.

But lo! His Eyes lit up, He beheld His Lady with vessels of wine,

𒀭ʾAshtart the Heifer made feast with the Rider on the Clouds,

a supper of honeycomb and wine and all kinds of fish;

She opened the City Gates for 𒀭Baʿal the Victorious,

Standard raised in triumph for the Rider on the Clouds.

#semitic pagan#semitic paganism#canaan#canaanite#cananite pagan#polytheism#ugarit#ugaritic#mythology#myth#myths#baal#hadad#anat#ashtart#el#pagan#paganism#canaanite paganism#ugaritic mythology#polytheist#ancient near east#ancient history#history#ancient levant#bronze age#phoenicia#late bronze age#ancient religion#asherah

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Asherah, ancient West Semitic goddess, consort of the supreme god. Her principal epithet was probably “She Who Walks on the Sea.” She was occasionally called Elath (Elat), “the Goddess,” and may have also been called Qudshu, “Holiness.” According to texts from Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra, Syria), Asherah’s consort was El, and by him she was the mother of 70 gods. As mother goddess she was widely worshiped throughout Syria and Palestine, although she was frequently paired with Baal, who often took the place of El; as Baal’s consort, Asherah was usually given the name Baalat. Inscriptions from two locations in southern Palestine seem to indicate that she was also worshiped as the consort of Yahweh. Via Britannica

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nehushtan

According to the Bible, Nehushtan was a metal serpent mounted on a staff that Moses had made, by God's command, to cure the Israelites of snake bites while wandering in the desert. The symbol of snakes on a staff or pole is a motif that is widespread in both the ancient Near East and the Mediterranean. This symbol held such cultural power that it is still around today in our modern world, like other ancient symbols we encounter almost daily, often without even realizing it. Humanity has a way of collecting images and holding onto them, subtly changing their context to fit the contemporary cultural system.

In our modern world, a staff with a snake wrapped around it is used as a symbol for medicine, a remnant of Greek and Roman mythology. It is the staff of an ancient healer god, known as Asklepios in Greece and Aesculapius in Rome. Another symbol from ancient Greece and Rome is the staff of Hermes/Mercury (respectively) which is seen on the back of ambulances. This symbol is a pole with two snakes wrapped around it and wings at the top. While both are often called a caduceus, technically only the staff of Hermes/Mercury is a caduceus. Additionally, both are often assumed to be medicinal in nature, but Hermes/Mercury was a messenger god known for speed and escorting the dead to the afterlife. One can easily see the connection between our modern use of these symbols with their sources from ancient Greece and Rome.

Moses & the Snake

The story of the biblical snake on a staff is first introduced in a brief couple of verses in Numbers 21, during the Exodus story. This passage is believed to have been written by the E source, in approximately 850 BCE. (For an explanation of biblical sources, see “Torah”.) The Israelites, while traveling to the Promised Land from Egypt, complained about the lack of food and water and, as punishment, God sent fiery serpents to bite and kill many of them. The people then pleaded with God for mercy and, deciding to grant it, God instructed Moses to create a serpent and put it on a pole. When people would look at it, it would cure them of their poison. Moses complied and made the serpent out of nechôsheth, which means bronze, brass, or copper in Hebrew. From here on, this text will use “copper” as the translation.

This narrative is reminiscent of ancient Canaanite sorcerers who would fight alongside serpents to protect people from snakes and scorpions, as described in texts found from Ugarit. These texts also included a large portion of spells which were used to cure snake bites. This incident in the exodus story is quickly passed over in the Bible, and this snake is not heard of again until 2 Kings 18 when King Hezekiah of Judah (who reigned from either 727-698 or 715-687 BCE) destroys it because it had by that time become a pagan cult object. It is also in this passage that it is given the name Nehushtan. Hezekiah destroyed many cult objects and places in an effort to reform the Israelites back to monotheism as they were slipping into idolatry and paganism. It is unknown how the object came to have a proper name.

Continue reading...

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mycenaean Colonization

Around 2000 BCE, the Indo-Europeans migrated to what is today Greece. After settling there, they lived for several centuries in the shadow of the splendorous Minoan civilization on Crete. However, the Indo-Europeans did not remain idle. They developed into a series of well-organized small states, ruled by kings (wanax) in their heavily fortified palaces. This led to the rise of the Mycenaean civilization, named after its most prominent and famous stronghold, Mycenae. After the disintegration of the Minoan civilization—partly due to the catastrophic volcanic eruption on Thera (Santorini) around 1650 BCE—it was the Mycenaeans' turn to become the dominant power in the Aegean.

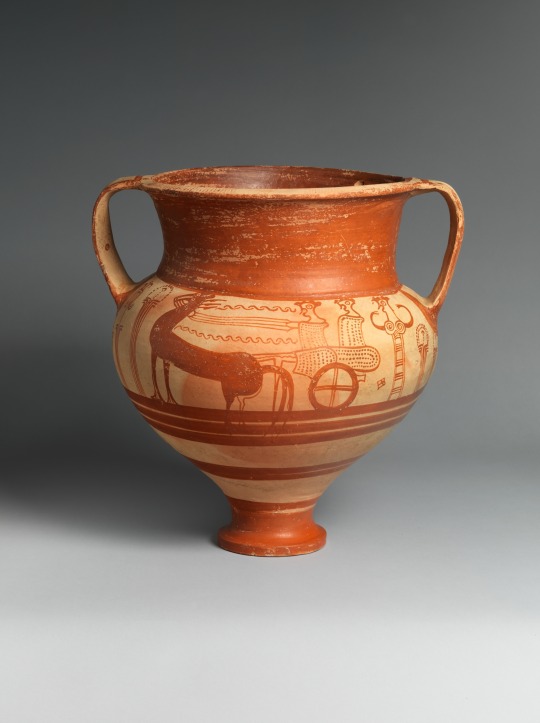

Their artifacts are found throughout the entire Mediterranean, with some of their manufactured goods even reaching Nubia.[1] This attests to the extensive trading networks of the Mycenaean states. Archaeology is our primary source of information in this area, as the Linear B tablets offer only limited evidence of Mycenaean commercial activity. However, this is not the focus of this brief article. Our aim is to explore the regions where Mycenaean presence was not simply the result of brief visits by traders, but rather the permanent settlement of large groups of Greeks—i.e., colonization.

There are three types of colonization. The first involves annexation, where a large group of immigrants takes over already occupied territory. The second is known as a “settlement colony,” where migrants establish themselves in unoccupied land. In this type of colonization, immigrants are most likely to retain their original cultural practices. The third type occurs when a large cultural group is allowed to settle in an existing town but is subjugated to local authorities. These colonies are usually established for commercial purposes. A good Bronze Age example is the Assyrian trading colony in the city of Kanesh, where the immigrants lived in a designated quarter of the city. These colonists in trading posts sometimes held a degree of autonomy over certain matters.

One methodological challenge is the lack of contemporary written sources providing information about colonization activities. To date, no word equivalent to "colonize" has been identified in Bronze Age Greek. [2]Moreover, no Linear B documents have been discovered outside the Greek mainland and Crete. Similarly, foreign texts from Mycenaean trading contacts, such as those from Ugarit, offer no relevant insights. Consequently, it appears that we are once again at the mercy of archaeology for answers.

Another potential non-material source of information is the epic tradition, though its use requires great caution. While some scholars dismiss the reliability of later literary sources, others see value in them. [3]Vanschoonwinkel argues that valuable insights can be gleaned by cross-referencing literary traditions with archaeological evidence. [4] He suggests that there is at least some truth to the stories about legendary times in Classical Greece. For instance, the reluctance of legendary heroes to visit the Levant and Egypt aligns with the lack of evidence for Mycenaean settlements in these regions. This approach gains credibility from archaeological research at Hissarlik (Troy), which uncovered evidence of a large-scale siege that could serve as the historical basis for Homer’s Iliad.

Pottery can also serve as a valuable source of information, though it can present a misleading picture. Some regions have been more thoroughly excavated than others, meaning a lack of pottery in certain areas of the Mediterranean does not necessarily indicate reduced Mycenaean presence. Similarly, a high concentration of Mycenaean ceramics does not necessarily signify colonization; it could just as easily result from successful trade conducted by the Mycenaeans.

As Vanschoonwinkel rightly observes, material evidence that cannot be easily attributed to mere trade—such as funerary practices—is particularly revealing. This aspect of human culture is deeply ingrained and rarely changes solely through commercial contact. Funerary practices similar to those of mainland Greece could, therefore, indicate the settlement of Greeks originating from the Mycenaean kingdoms.

To date, no substantial Helladic evidence has been discovered at any site that conclusively indicates Mycenaean colonization outside the Aegean.[5] While some traces suggest the presence of Mycenaean individuals or small groups, there is no evidence of large-scale migration. Some archaeologists have proposed the existence of Mycenaean trading posts in locations such as Ugarit and Tell Abu Hawam in the Levant[6], Scoglio del Tonno in southern Italy, Thapsos in North Africa, and Antigori in Sardinia.[7] However, these claims have been effectively disproven.

Excavations in Cyprus and western Anatolia have provided more compelling evidence, including the prevalence of imported Mycenaean pottery and the presence of local workshops producing similar ceramics. Even more significant is the similarity in funerary practices. The Bronze Age archaeological layers at Iasus and Miletus reveal urban centers that were either Mycenaean or heavily Mycenaeanized. Additionally, discoveries such as the necropolis at Müskebi, the tholos at Colophon, and possibly the cemetery at Panaztepe suggest the existence of more Mycenaean settlements in Asia Minor.