#USDA zone 6b

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I'm in USDA zone 6b. but! I'm at 2k elevation in high desert. that means it gets brutally cold, then brutally hot, with almost no spring or fall weather. it means the heat wave starts in July and goes into August, burning everything. it means no rain from June until October.

it means last frost is mid May, last freeze is April; but it could snow into June. it's really fucking weird to grow anything here.

I use rain barrels to collect all winter. it's enough for the worst weeks of drought. I use homemade ollas in the middle of my garden to try to keep things watered. I use light mulch to keep the soil damper in the heat. I have a shade cloth but it's never enough (now taking donations of large burlap rolls or such!)

our season is short. 100 days, 110 at most. usually it's closer to 90. the original soil is urban, compacted silt on decades of grass lawns. it needs loads of wood mulch, manure, aeration, fertilizer. I've been feeding the dirt for 7 years.

I'm in town. so big trees are not possible but semi dwarf, dwarf trees are ok. I'm trying my best.

it was 56F yesterday then today it snowed. 55F+ all week in the daytime, below freezing at night. difficult conditions.

good for apples though- but there's so many here that you've got to spray them or they die.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

food & agriculture in fallout: extrapolation and speculative worldbuilding

Okay, well. This is going to be an extremely long and data heavy post. Bear with me.

I'm going to go into detail about the crops and available food given to us canonically and textually. I'm going to be drawing some real world parallels between the crops we see in Fallout and what we have here. I'll be pulling relevant data from all the games, but the majority focus on this post is going to be about the east coast and Massachusetts in particular because it gives us the opportunity to participate in the agricultural climate of the wasteland.

Is there a point to this? Not really, but I'm pedantic and I take things too seriously.

my sources will be linked in the text throughout. for those of you who want to read about agricultural and growing zones of the continental united states, please follow me under the cut.

Growing zones and real world agriculture

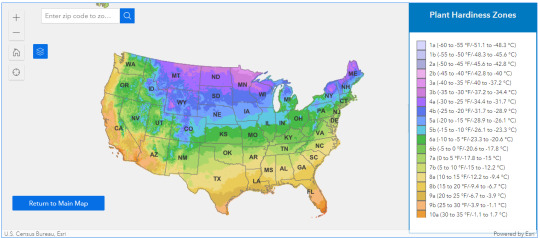

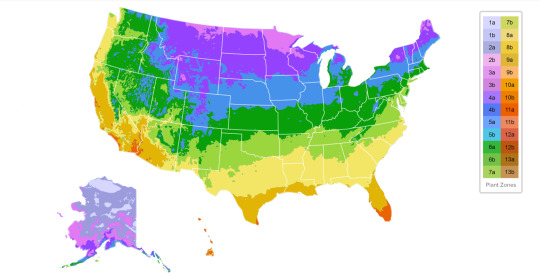

Shown here are the growing zones of the united states, divided into a temperature map of about 19 different regions. It's fairly intuitive to read -- colder temperatures are north and east, while warmer temperatures are south and west. The majority of the Mojave desert sits between 7a to 9a, a temperature range of about 20 degrees. DC and the nearby section of the southeast coast sits between 7a and 8a. The interactive map linked below will tell you where your growing zone sits.

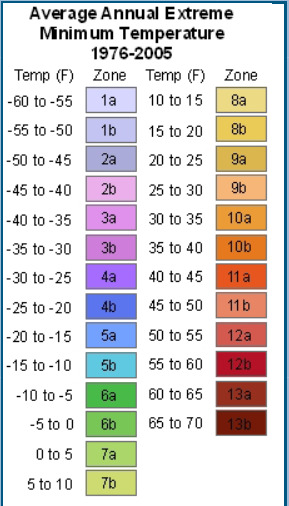

The 2012 USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map is the standard by which gardeners and growers can determine which plants are most likely to thrive at a location. The map is based on the average annual minimum winter temperature, divided into 10-degree F zones and further divided into 5-degree F half-zones.

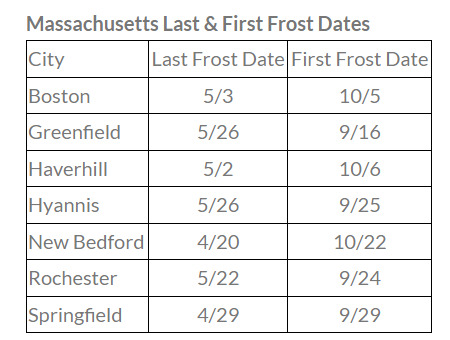

For the moment, we are going to focus on Massachusetts.

Using the temperature above, we can see that the growing zone of Massachusetts is 5a (-20f) at it's very coldest, all the way to 7b, (5f) at it's warmest during winter. Most of what we see in fallout 5 sits in the 6a to 6b zone, which is middle ground during the winter, but cold enough to want to warrant crops that can withstand the frost.

There is a solid 5 month window for planting annual crops, like corn, melons, and gourds like pumpkin. Your perennial crops are limited to fruit trees and possibly grains, depending on the variety and whether or not a perennial variety has been bred.

Cold weather crops include beets, carrots, greens like cabbage, collards, kale, and potatoes. These aren't the types of crops that will survive the winter as much as these are foods that can go in the ground as soon as it is unfrozen enough to be workable. Root vegetables and greens can germinate in soil as cold as 40 degrees Fahrenheit, which provides some leeway with unpredictable frosts and late planting times.

Much of the agricultural landscape of Massachusetts is dependent on the dairy industry, farming cattle, and aquaculture -- fishing and catching shellfish. Those with access to the coasts, fish and shellfish ought to provide protein during lean months.

Why are we talking about this? Well, if we're stepping into the shoes of a subsistence farmer in the fallout universe, we're going to have to take into account climate and ideal planting times for certain crops. It's not wholly important in terms of things like fic writing, unless you happen to be writing about the life and times of wasteland agriculture, in which case, I hope this is helpful! Again, I am pedantic, and this section is to provide a template when considering and discussing other parts of the game and what their specific diet and agricultural landscapes might look like.

Something to keep in mind when thinking about how farms might function in the Mojave, for instance, or if you're doing worldbuilding for a different part of the US.

Crops in the fallout universe

Now that we're familiar with growing zones and why certain crops are planted and when, we're going to apply some speculative worldbuilding to fallout itself. We will be revisiting growing zones when we talk about other climates, but for the moment, we're going to focus on fallout 4.

Now to preface -- I don't think that the food that is given to us in game is wholly representative of the plants or animals that survived the apocalypse. If some managed to mutant and survive, I'm willing to bet others did. I certainly won't deduct any points from anyone who wants to talk about growing cotton, or farming peaches or cherries, and I won't raise any eyebrows if someone includes things like spices into their wasteland cuisine.

In the 210+ years since the bombs fell, I do not think that the majority of the US is a desolate wasteland, but this post is not going to be my beef with the devs about how brown everything is. This beef is about food in particular. However, for sake of ease, I'm mostly just going to focus on the food that is presented to us in game.

There will be some extrapolation and speculation later, but if I do that for everything, then we'll be here all day, and we've all got things to do.

I would also be remiss to mention that agriculture in the US is old. It predates colonialism. The Native Americans cultivated the land long before any European settlers. They practiced a type of crop growing referred to as Three Sisters planting, which utilized corn, pole beans, and squash -- all things that exist in the agricultural landscape of Fallout as we know it.

Corn

I'm not going to say much about corn because there's not a lot to say about it. We all know what corn is. Fallout's corn is visually similar to wild violet, a hybrid corn.

But I am not going to say Fallout's corn is one such variety or another. In the 210 years since the bombs dropped, I imagine corn varietals have been bred and interbred a thousand times, and it is probably it's own unique strain. It's kind of a moot point. Corn is corn. You can do with yellow corn what you can do with wild violet, and whatever special breeds that make up Fallout's corn.

Corn is the third largest plant-based food source in the world. Despite its importance as a major food in many parts of the world, corn is inferior to other cereals in nutritional value. Its protein is of poor quality, and it is deficient in niacin. Diets in which it predominates often result in pellagra (niacin-deficiency disease). Corn is high in dietary fibre and rich in antioxidants.

You can do a shit ton with corn. It's a staple grain. It would not be incongruous with the fallout setting to have settlers making tortillas, cornbread, polenta, grits, tamales, etc. Corn can also be used to make corn whiskey. The husks can be spun into yarn and woven into garments similar to cotton, which I thought was interesting and also solves the problem of where the hell wastelanders are getting their clothes. Corn can be used as livestock feed, especially in the winter when cattle can't graze. While corn is a staple grain of the US, the east coast has minor corn production compared to places like the midwest. Corn is a staple, but it does not consist of the entire diet of your average wastelander.

Carrots

Not going to say much about carrots either. They're carrots. They grow well in colder soil and tend to have a lot of natural sugars. The carrots we're shown in FO4 seem to be a mutated variety different than the "fresh carrot" consumable in FNV, but there's virtually no difference, so I'm not counting it. Make some carrot cake.

Razorgrain

"This species appears to be quite promising. It's a toothy grain that we may be able to grind in order to replace wheat, which is untenable in the Wasteland. We are uncertain how to increase crop yields, which are very unpredictable. Will continue to study."

Razorgrain is our first unique mutated crop in the fallout setting. It most closely resembles a barley or a rye. Both are a fairly hardy species and can grow all across the continental united states; rye can germinate in cold weather temperatures. It wouldn't be outrageous to assume that razorgrain is similar too or a crossbred variation of both rye and barley. I have decided to base the majority of my research assuming it is a barley variant. Barley is also a major crop on the east coast near the Commonwealth, so that would explain why razorgrain is present in FO4 and not in the other games.

Barley requires a mild winter climate and can grow in growing zones 3-8, so it would be viable in Massachusetts. Barley can be milled into flour and it contains gluten; the gluten content of North American wheat and barley tends to be higher to survive the colder climates, so razorgrain would likely be very glutenous. It is also less susceptible to ergot than rye, but barley can still become infected -- and, I am assuming, razorgrain could as well.

Razorgrain fills the nutritional niche of carbohydrates and can be used to make breads, cakes, pastas, etc. It produces darker breads that have an earthier flavor than milled white flour. There has to be some method of actually milling the grain, though, which is an intensive process that can often be dangerous. Grain can also be used to make malted candy, which is our first option for wastelanders with a sweet tooth. Obviously, razorgrain can also be used to make malt or grain alcohol and is probably the source of all the beer you find littered around the wasteland.

Gourds and melons

Gourds and melons are actually a part of the same family, Cucurbita. The category of 'gourd' covers several different kinds of vegetables, including ornamental fruits that shouldn't be eaten. We aren't going to spend a whole lot of time on this one, simply because canon doesn't tell us that much and there's a lot of wiggle room in terms of interpretation.

FO4's model looks the most similar to a pumpkin, but it could be some other squash varietal from the Cucurbita family, which includes watermelon, honey melon, cucumber, squash, zucchini and pumpkin.

Melons is another pretty broad category. Melons and squash are part of the same family, as mentioned above. If we're going visuals again, the model is likely intended to resemble a watermelon. Watermelons grow best in humid and semi-arid environments between 70 and 8- degrees Fahrenheit. It's not impossible for wastelanders to be growing watermelons, but considering the humidity and frequent rainfall in Massachusetts, the melons would be vulnerable to fungal infections.

There isn't a lot of information on what specifically gourds and melons are in the fallout universe, so you could get away with writing in a pretty wide variety. Personally, I lean a little bit towards melons being a muskmelon variety, like cantaloupe or honeydew. Squash fills in some vitamin requirements for the human diet, and can be canned and stored for winter. It tends to be high in vitamin C and magnesium.

The limit to this one seems to be your imagination. Go crazy.

Mutfruit

This wiki claims that the mutfruit (it has a scientific name apparently, malus maata) is a mutated species of apple and crabapple. There are two different wikis about the mutfruit, both distinct. The first is linked above. The second is linked here -- I got most of my information from this second wiki.

There is a handful of "canon" information we can take from this set of wikis.

Priscilla Penske in Vault 81 is attempting to create foods that have increased resistance to radiation. She mentions the mutfruit would do well, but isn't certain how the hybridization would affect the flavor and texture.[5]

This claim is taken directly from the second wiki, but in comparison, it makes no sense. If the mutfruit tree is a product of mutation, then radiation shouldn't really affect it at all. It's survived and propagated to this point, hasn't it? I am disregarding this claim on the basis of being stupid.

Farmers in at Warwick homestead will comment on the fruit's characteristics, such as tasting sweet and being versatile in recipes.[1][2] The vault dwellers of Vault 81 trade for mutfruit with the outside world, and use it to make special occasion desserts such as pie.[6][7]

If the mutfruit is an apple variant, then it likely has a high sugar content, and it would have to be harvested in the peak of summer or in early fall.

There are fresh apples the be found across the wasteland, implying the existence of apple trees that have been unaffected by the bombs. Personally, I was assuming that the mutfruit was some kind of blackberry, given its appearance as a clustered fruit, or maybe even a type of plum. Regardless, the mutfruit is a fruit, which means that it would preserve well by being jarred or canned, has a high sugar content, and could likely be reduced to form sugar syrups. Like any fruit, it could be used to make alcohol.

Tatos

I want to stop myself from editorializing too much, but goddamn tatos. The crop that makes the least goddamn sense in the fallout universe. The bane of my existence. Let's get into it.

First off, we're given some pretty damning canon facts about tatos:

Tatos are a mutated hybrid of the cross-pollination of the tomato and potato plants.[1] The new consumable looks like a tomato on the outside, but the inside is brown.[2] Commonly cultivated in the Commonwealth, Appalachia and on the Island, its fruit is easy to grow and can keep one from starving, but their taste is described as "disgusting"[2][3][Non-game 1] and resembling "ketchup-flavored cardboard."[1]

According to some old botany texts we found, this appears to be combination of a now extinct plant called a "potato" and another extinct plant called a "tomato." The outside looks like a tomato, but the inside is brown. Tastes as absolutely disgusting as it looks, but will keep you from starving.

Note: This text was written from the perspective of someone who is unaware that both the tomato and the potato are being cultivated elsewhere. The writer also does not mention any sort of DNA test. However, the potato is also found in the Capital Wasteland, and the writer is a scribe in the Brotherhood of Steel, which originated from that area.

Both potatoes and tomatoes are from the nightshade family. They have the same nutrient requirements, and would compete for resources if planted separately but in the same soil. There is a method for planting them together where you splice a tomato stalk onto a potato root, but this is not the same as cross pollination and will not result in what fallout presents as a tato. What will happen is that the roots will grow potatoes and the fruit of the tomato will branch off the stems.

The potato itself is a stem tuber -- high in starch and calorically dense. A stem tuber is an offshoot of the parent plant that will grow beneath the soil as a type of asexual budding reproduction. We all know what a potato is. The tomato is a berry. It's the ovary of a flowering plant -- again, we all know what a tomato is.

I am going to give Fallout a little bit of grace and not comment on how mind bendingly stupid their description of a tato is. The outer skin is a tomato, but the inside is brown and starchy like the potato? I am not going to comment on how it makes little to no biological sense. The starchy tuber is starchy because it's an energy and nutrient storage device. The tomato is the enlarged ovary of a fruit. Why did those things, which are separately very good, combine into one very terrible thing? I don't know. It doesn't make sense. I don't really want to think about it. But these are the facts as they are given to us in game and I suppose I have to live with that. Obligatory "goddamn you todd howard. a pox on your house."

The tato is probably extremely calorically dense. It's specifically mentioned as being easy to grow and it is a better alternative to starving. It's probably grown as a staple crop throughout the planting season. I'm not entirely sure if the tato can produce glycoalkaloids like the potato does (that is, the green sections of the potato that can become poisonous when exposed to light) but if they can, and if stored improperly, it would negatively impact the health of whoever ate them.

I suppose since the taste is so offensive, tatos are better served as a carrier of some other type of food. Fried, mashed, baked -- the purpose of the tato is simply to get calories into your body. Starch can also be turned into alcohol, which I am going to need a lot of after reading the canonical facts of this stupid fucking plant.

Fallout: The Roleplaying Game Rulebook p.158: "A mutated hybrid of the pre-War tomato and potato plants, with the stem and reddish skin of the former and the brownish flesh of the latter. Tatos provide decent nutrition, but taste disgusting. However, they’re relatively easy to grow and thus are a staple of wasteland agriculture and is an ingredient in a variety of recipes."

fucker

"non farmable" crops

You can't cultivate these plants, but again - we're taking what's given to us and interpreting it extremely literally. There is no reason that these crops could not be domesticated and farmed.

Siltbean

Siltbean is likely a type of bushbean, rather than a pole bean. It's squat and low to the ground. Bush beans require little care or attention and you can pick them when you're ready to harvest them. Historically in North America, beans and corn were grown side by side (though those beans were pole beans using the stalks as support). Bush beans require successive plantings since harvests are early.

There's no good allegory for what type of bean this might be. The potato bean (Apios americana) is native to North America and also produces edible tubers, but there's no reason this couldn't be just some other type of bean. No beans that I could find had red/orange pods.

Beans are a good source of both proteins and carbohydrates, and another crop that can store well for the winter.

Tarberry

Tarberry is a little iffy, considering it is farmed by the ghouls at The Slog, but they're the only farm shown capable (or willing?) to farm the berries. Originally, I had assumed that tarberries were a type of mutated cranberry, and I thought the wiki was supporting me in that claim by saying this:

Tarberries are small, dusty orange berries of the tarberry plant. It is a water-grown crop similar to cranberries.

But cranberries themselves are also canon in the world of Fallout. So who knows! There's no canon information presented on the tarberry's characteristics, so it can be treated the same as any other fruit or berry.

Fungus variants

Glowing fungus: Glowing fungus is one of the few real world equivalents we have. It is a Japanese mushroom called Enoki. It is also farmable as shown in FNV at Hell's Motel.

Brain fungus: This is harvestable, but there aren't any "crops" shown as we would consider them. Considering it's benefits as a mentat replacement, then it's likely that there could be a dedicated space for growing it.

Food and Plants mentioned in the text

Potato

Thank god almighty, potatoes are canon in the universe of Fallout. Fresh potatoes are found as consumables in FO3 and FNV but potatoes are also mentioned in the text of FO4:

Mentioned in dialogue -- {Angry} Shut up Jake. If I hear anything out of either of you, you'll both be peeling potatoes for the next year.

I'm taking this as word of god. Potatoes are canon and I don't care what anyone says.

Tomato

Tomatoes are mentioned in the text, but are never actually seen in game. The only hint that this plant survived extinction is this excerpt from the wiki.

Note: As fresh tomatoes and potatoes are seen in the Mojave Wasteland as of 2281, with the potato seen in the Capital Wasteland as of 2277, the claim of either's extinction by 2287 in the Commonwealth Plant Database could be taken to mean local extinction in east coast regions, as opposed to global extinction. This entry may also just be in error.

There's potential for leeway here, but take it as you will!

Fresh apple

We discussed this back up in the mutfruit section of the essay, but the existence of fresh apples implies the existence of non mutated apple trees. They're found in both FO3 and FNV as a consumable item, so the apple tress have either proliferated across the continental united states, or multiple varieties survived the bombs.

Fresh pear

See above. Pears are also naturally high in pectin, which makes them useful for making jams and preserves.

Pinto beans

Pinto beans are a consumable in FNV and is another W in the bean category of the agricultural landscape.

Jalepeno

Look, I'm picking out this one specifically because I need to believe that other spices and peppers exist in the world. Where would we be without her? Nowhere good.

Raw sap

I am going to say that sap collecting is probably where most of the sugars and sweeteners in the wasteland come from. It's relatively easy to tap trees and collect sap, and it only takes a few hours to reduce the sap down into useable syrup.

Wild Blackberry, Lime, Cranberries, as well as Watermelon as being distinct from simply 'melon' are all mentioned in the text. The list of fruits mentioned or found in the games can be found here.

Animal husbandry

Fallout doesn't give us a lot of canonical information on the animal side of farming. The biggest real world agricultural export of Massachusetts is dairy and cattle farming. Chickens are canon in the worldbuilding of fallout as of Far Harbor, but canon feels both restrictive and extremely loose with regards to what animals can be cared for and how.

We aren't going to spend a whole lot of time on this one, only because the information is pretty limited.

Brahmin

There are plenty of brahmin found throughout the landscape of the wasteland. We most commonly see them as either livestock or beasts of burden. Things like milk, cheese, and other dairy products would be common if a farm has access to dairy cows. The investment to raise cows would be enormous for a subsistence farmer. Dairy cows would likely be kept for a number of years, where steers would be raised 12 to 24 months before being slaughtered; they'd likely be grass fed in the summer and corn or grain fed in the winter. Leather and beef would be products, of course, and things like soap and candles can be made from the beef tallow.

Chickens

Chickens are largely easy to keep and care for, producing eggs and necessary proteins. Chickens can provide niacin, filling in the nutritional gap that would be left by a heavy corn based diet. The investment for keeping chickens is lower than raising brahmin, but so is the payoff.

Bighorners

Bighorners are mutated bighorn sheep native to the American Southwest.[1] Humans have since domesticated them for their horns, meat, milk, and hides,[2][3]

Granted, bighorners are only seen in FNV, but I don't think there's any reason they couldn't have migrated east. In the text, it says they're kept for meat and milk, but there's no reason that they shouldn't provide a fleece as well. In the colder climate of Massachusetts, they would find value in wool, which can keep its warmth even when wet. They may be sparse across the commonwealth, but that would make wool and fleece all that much more valuable.

Fish

Yeah, I know. Technically we can't fish in Fallout (and depending on the game you play, you might not even know what a fish is). But aquaculture is huge in Boston, and with access to the coasts, it's completely fair to say that fish, shellfish, and hydroponics is a completely viable source of food in the wasteland. We see dead fish washed up on shore all the time, along with whatever the hell those shark things are. There should be fisheries and fishing towns all along the coasts.

New Vegas and Fallout 3

Consulting our growing zone chart, we can see that much of the southwest sits between 7b to 8b. The winters in the southwest are fairly mild, and while you can get seeds in the ground sooner, the majority of the battle is going to be finding a reliable water source.

The farming we see in New Vegas has one distinct notable inclusion: the NCR sharecropper farm.

The sharecroppers are growing a number of crops, including maize, tobacco, pinto beans, and honey mesquite. Corn can handle hot, arid weather, it's just not commercially grown out west. Barley can also handle hot, arid climates, and razorgrain would be suitable for the western front -- maybe we can assume it's made it's way that far west and is being cultivated alongside corn.

Most of the plants we see in FNV aren't the type we would see typically domesticated for agricultural use, but that doesn't mean people haven't adapted to their surroundings. It makes a lot of sense for locals to have domesticated local plants like prickly pear and banana yucca. There are a number of fresh produce items to be found as consumables, alongside local fruits the local fruits.

Heat-loving plants are best suited for summer production in desert climates. The plant families that fit into the heat-loving category are nightshade or Solanaceae (tomatoes, peppers, eggplant) and squash or Cucurbitaceae (cucumbers, melons, summer and winter squash). Corn and beans also perform best in hot climates.

Most plants CAN handle the heat and climate of the southwest, the issue is just finding a reliable source of water. Somewhere close to Lake Mead or the banks of the Virgin River would be prime real estate for farming, since irrigation could be accomplished without the use of pumps, like the sharecroppers use.

If we look back at the history of agriculture, it's developed along established waterways in almost every ancient civilization because that's what's easiest. There should be thriving communities surrounding the lakes and rivers in the southwest.

Comparatively, DC was formerly a swamp. It's hot and humid in the summer, though the winters are fairly mild. It wouldn't be a stretch to say that farming practices in the Commonwealth don't differ all that much from farming in the Capital Wasteland -- you could even posit that food from the Capital is of better quality ever since the successful activation of Project Purity. Fresh and unirradiated food was growing there before, so it's entirely likely that even more is growing now. YMMV!

Other consumables

We would be here all damn day if I did research onto every single consumable item available across all three games, so this mostly just because I'm covering my bases.

I am going to say that sap collecting is probably where most of the sugars and sweeteners in the wasteland come from. It's relatively easy to tap trees and collect sap, and it only takes a few hours to reduce the sap down into useable syrup.

Look, I'm picking out this one specifically because I need to believe that other spices and peppers exist in the world. Where would we be without her? Nowhere good.

Pre War food

Most shelf-stable foods are safe indefinitely. In fact, canned goods will last for years, as long as the can itself is in good condition (no rust, dents, or swelling). Packaged foods (cereal, pasta, cookies) will be safe past the ‘best by’ date, although they may eventually become stale or develop an off flavor.

The risk with improperly canned good, or damaged canned goods, is botulism. Botulism will straight up kill you. You don't even have to consume that much of it; just a little bit will leave you dead in days. As desperate as I might be for a meal, I'm not going to risk dying because that can of two hundred year old peaches looks really tasty.

If properly sealed and in a dry, ideal environment, I... guess things like cereal and instant food could be okay? But again, with access to fresh grain, sugars, and yes, even potatoes and pasta, why would you want to risk eating InstaMash that's been around since before your great grandmother.

Pre War drinks

Sigh. Okay.

Unless stored extremely, extremely well, most bottled drinks aren't going to last much longer than 9 months. A year, if you're lucky. Exposure to sunlight and improper storage will break down the contents -- the best bottles are brown, then green. Clear glass is the worst because it does nothing to protect the liquid inside.

All the Nuka Cola you find throughout the world is flat, nasty, and will probably make you sick. I don't think that really needs to be pointed out, but there we go. I suppose the soda could probably be reduced to form sugar syrups, but with access to sap syrup and grain malt, I'm not sure why you would be desperate enough to do that.

So what does food look like in Fallout?

If there's one thing I know about humans, it's that humans like to eat. Food is culture, as much as culture and community is built around food. Good food and access to it is paramount to human happiness. All this to say is that food in fallout is whatever you want it to look like.

I can extrapolate and theorize all day long based on what Fallout tells us definitively, but I'm not going to tell you what the culinary landscape in the wasteland looks like. The only point that I will stress is that humans are really, really good at making things appetizing.

The fandom is already so creative when it comes to developing their idea of what food means in the wasteland. It's what's directly inspired me to write up this stupid, long ass post about farming and agriculture.

Obviously this is not a comprehensive list of all the base ingredients you can find in Fallout. I picked the ones I did because of the potential for consistent farming. Wastelanders have had two centuries to develop agricultural practices based around subsistence farming. I am not a subsistence farmer, and I have no idea how wasteland cottagecore would work at the heart of it. Running a farm is extremely labor intensive, and so much of your investment has to be immediately recouped in the form of eating what you harvest.

What a farm is likely to look like will start in the early spring when the ground begins to thaw, and a farmer can plant his cold resistant crops, like green vegetables and razorgrain. Potatos, carrots, and tatos will also weather the spring chill. When it starts to warm up, the more delicate plants like corn, beans, and squash or melons will get planted and tended to.

If your family is lucky enough to have a greenhouse, you can keep crops growing all through the winter and have a surplus for trade and barter, or just to preserve and refill the pantries.

A lot of the investment will have to be immediately recouped. Eggs from the chickens can't be preserved, obviously, but there will be meat from hunted animals, milk from the brahmin, probably an early harvest from the beans and tatos, and whatever else is in the pantry from the previous harvest.

Some of it will be canned or preserved in the forms of jams or jellies (just remember what I said about botulism). Meat from animals that get hunted can be smoked or otherwise preserved. Grain can be milled into flour or eaten whole and unshelled. Even the corn silk can be woven into clothes for the summer.

There really is no limit to what can be done in the end. While a lot of this information was taken from what we're given in the text, there's no rule that says you have to follow it word for word. If you believe something exists out there, then write it! We're all just making shit up as we go along anyway. If you need permission, then here it is. You can do whatever you want. Make up recipes! Go insane. Follow whatever your little foodie heart desires.

#fallout#kal talks#fallout 4#fallout new vegas#fnv#fallout 3#fallout meta#fallout food#fallout headcanons#behold. the agricultural masterpost of my farming headcanons#here she is

821 notes

·

View notes

Text

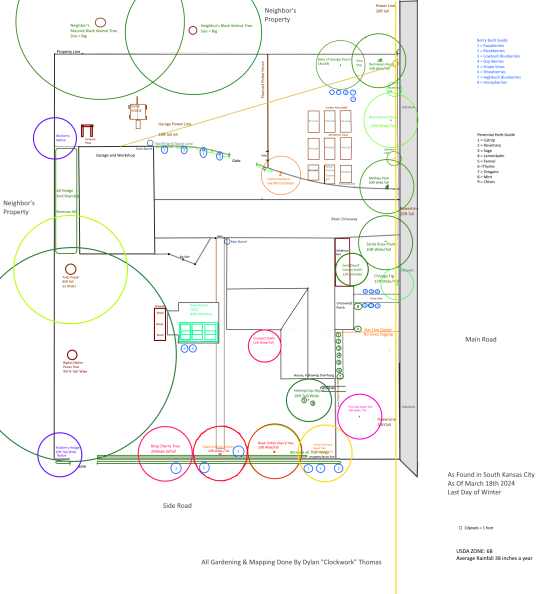

Decided to make my own permaculture map for everything that I'm growing around my house and workshop. It wasn't too difficult, let me know if it's difficult to read for anyone or if anyone wants advice making their own.

This map includes:

Apples Trees x4

Peach Trees x2

Cherry Trees x4

Japanese Plum Trees x2

Blue Damson Plum Tree x1

Fig Tree x1

Pecan Tree x1

Hazelnut Tree x1

Mulberry Tree x2

x8 Different Types of Berry Bushes

x9 Different types of Herbs

One Greenhouse made out of scavenged windows.

A Duckhouse that looks like a rabbit for legal reasons.

Two plots for perennial vegetables such as, horseradish, asparagus, and rhubarb.

And Seven Plots of Annual Vegetables that somehow take up the most of my time.

USDA Zone is 6B in South Kansas City.

#solarpunk#solarpunkdiy#permaculture#permaculture map#gardening#garden#maps#homesteading#farming#agriculture

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don't know if you've ever mentioned what hardiness zone you live in, but if you have any good zone specific resources you'd like to share, re. the planned food forest that would be super cool

Ooh! So you may not have known this when you brought it up, but this is an interesting and challenging phenomena I've been working within!

Climate change is causing USDA hardiness zones to evolve with time in really interesting and unique ways. So while the zoning at present in the region I'm planning for is in the 6's (6a or 6b depending on elevation and location), there are also zones of 7 and even 8 spreading across the region and we're having to plan our food forest to evolve with that spread.

So essentially, I have been working with a hardiness RANGE rather than a SPECIFIC hardiness zone, seeking out plants that demonstrate dofferent qualities at different zones and will still allow the forest to function symbiotically if climate change impacts our zoning unpredictably. This has been interesting work! Some trees are more like shrubs in colder climates and then become giants in warmer zones, allowing them to take the place of overstory trees that may begin to struggle or even die out with a warmer zoning. Other plants may be more likely to grow wild and out of control in warmer zoning and therefore should be monitored closely as indicators of zoning shifts, as well as utilized more heavily or even culled as a transition occurs.

Most of this information has been accessible to me through my regional service extension site, which has a truly GLORIOUS amount of knowledge collected about native and introduced flora and fauna, as well as their growing conditions and adaptive environmental information:

https://www.ces.ncsu.edu/

However, I do also often lean on the old farmer's almanac as a classic and time-tested source of agricultural knowledge:

The big thing to know about hardiness zones is that they impact HOW you grow things a lot more than WHAT you grow. Certain things will be native or a thriving introduced species, and hardiness zones can abasolutely contribute to that, but many domesticated plant species will and can happily grow anywhere with the right circumstances. A food forest is all about navigating that balance. What is meant to grow here? What can comfortably coexist here? What can meet a need or contribute to forest interdependency here? If you are answering those questions, your forest can thrive, even with plants ostensibly not within your hardiness zone. You may have a lessened harvest or a slower growing plant, but that's not necessarily a bad thing here. Food forests operate on the scale of decades or even centuries, not single year harvests. A single crop with a low yield isn't a problem if it fills other roles within your ecosystem.

An example of this: we plan to grow largely hard necked garlic. It's cold hardy in a way that soft neck often isn't, stores well, is native and has varieties native to the region, allows us to also grow cut and come again scapes, and will remain viable even if the climate warms, despite being slower to produce. And because garlic, an allium that is largely safe for livestock to consume, fills several roles in food forestry (it's rhizomatic - being a root vegetable - and helps aerate the soil, it repels unwanted pests from nearby crops, and it can be a good nutritional compost in the soil for other plants if left to decomes rather than harvested) it can be widely cultivated in the forest at rates that allow a sizeable harvest for us while still leaving plenty to the forest itself, even in the event of a zoning shift.

Most of the biomes and guilds within my food forest contain alliums, specifically native hard neck garlic and cold hardy leeks which, despite their similar flavor to onions, lack the toxicity to most animals and livestock that onions typically have. It's essentially the base components of my rhizomatic layer of food forestry, in much the same way that violets and marigolds are the base components of many of my ground cover layers for guilds.

Often what ends up being far more influential of "what plant goes where" is things like soil composition. For example, I've been fleshing out my Juglone guild recently for the first issue of Rewilding and Other Matters of the Soul, and the defining characteristics of the guild are the following:

Hardiness Range 6-8 compatible

Moist soil with a high water table that only rarely dries out

Full shade plants or partial sun tolerant plants

Juglone resistant

It was REALLY impressive how drastically those 4 qualifiers narrowed down my list of available plants, especially when you're only willing to use natives, non-invasive introduced varieties, or local domestic heirloom cultivars. I managed just over 30 varieties of plants for a guild. Which sounds like a lot until you realize that forests have probably several thousand species of plants per km, and we're trying to replicate that biodiversity with only 30 cultivars.

But it's a starting place, right?

You start a guild with 30 cultivars, and then little by little you see what else grows there, what else creeps in and makes a home, what else volunteers itself to grow in your little mini tract of forest, and suddenly it's not 30 but 50, not 50 but 100, and little by little you turn an acre of barely grown trees into a lush forest of plants and undergrowth and life.

Hell, start a guild with half a dozen cultivars, one each for each layer of the forest, and do the same thing, and little by little watch it grow and creep and expand until it takes back the land.

The Juglone Guild is in its final form for now (at least the final form it will take for release in the zine!) but I still have some work to do detailing uses for the plants, their role in the forest, and some philosophy around rewilding and why we do it in the first place. I have notions about connecting rewilding of the land and rewilding of the mind that have been floating around in my head since some recent conversations around prison abolition with a comrade, so I may see how to slide those in as well over time.

All this to say, getting to know your hardiness zone is mostly about getting to know the land you'll be collaborating with to cultivate growth and biodiversity. And as frustrating as I and everyone else may find it, one doesn't do that through a webbed site. One can learn how though! One can learn all about soil composition, nutritional needs and biochemistry of plants, the differency between well drained versus poorly draining soil, the difference between sandy soil, loam, and clay, the difference between a nitrogen fixing plant and a a plant that reacts to excess phosphorus in the soil, how long compost takes to decompose and the difference between hot and cold decomposing matter, all this stuff. And if you learn about it in advance, then when your crouched down in the dirt like a gremlin, digging around to look for good places to plant trees, drop a well or divert a stream, build a barn or house, put your moist plants versus your dry plants, it'll feel like second nature to dig down, find ash and know that this place will feed your babies, or watch a mud puddle live somewhere for 8 months of the year and decide to build a forest designed to re-aerate the soil and enjoy the high water table underneath. Getting to know the land starts with getting know what land is, and that's something a lot of us haven't grown up being taught.

#the earth is alive and she is calling you home#rewilding and other matters of the soul#food forestry#sustainable agriculture#have you ever squished your toes in topsoil? it's very good

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Make your garden GAY with our free seeds by mail program!

just select what you want and give us a mailing address and seeds will be mailed to you for free so long as you live in the US!

What's on the list changes as we run out or as we get local folks giving us more seeds to send out!

Live in the Bethel CT area and want to drop off seeds you saved from last year? You can drop them off at Rainy Day Paperback at 81 Greenwood Ave. during business hours or in the yellow drop box on the porch.

We also host a monthly in-person plant swap. March & April are indoor plants only, but May we will have free live seedlings and trees available!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

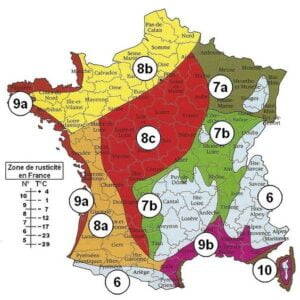

Zone de rusticité en France

gerbeaud.com

QU'EST-CE QU'UNE ZONE DE RUSTICITÉ ?

En fait, on parle de zones USDA qui ont été créées par le département de l’agriculture des États Unis (US pour United States, D pour Department et A pour Agriculture). Une carte a été créée afin de déterminer une moyenne des températures minimales pour chaque région. Cette dernière est la norme utilisée par les jardiniers et les agriculteurs pour connaitre avec exactitude quelles températures que chaque végétal peut supporter. Prenons un exemple. Une plante qui est rustique jusqu'à une température de -15° mourra si la température descend sous cette barre. A noter que la plante en question peux avoir certains dommages dans sa partie aérienne avant que la température de -15° soit atteinte. En principe, elle doit repartir de la base à la saison printanière car le système racinaire n'a pas été atteint. Il en est de même pour les végétaux qui craignent énormément la chaleur et qu'il est fortement déconseillé de cultiver dans le sud de la France.

https://www.pinterest.fr/pin/215539532151270979/

QU'EN EST-IL EN FRANCE ?

En France, nous avons la particularité d'avoir une diversité de paysages, mais aussi des climats bien différents. En effet, malgré un climat globalement tempéré, notre pays, suivant les régions, affiche de grandes différences de température, ainsi que de pluviométrie. Dans la nature, vous verrez des végétaux spécifiques à chaque région. En ce qui concerne les jardins, Il faut adapter la culture des végétaux en fonction de sa région (plantes rustiques donc résistantes au froid, celles qui se développent mieux avec un climat doux et humide.. Etc..)

VOYONS CELA PLUS EN DÉTAIL

type 1 : les climats de montage Le type 1 concerne les climats de montagne qui est réparti sur une bonne partie de la France : Massif Central, Alpes, Jura, Pyrénées, Morvan, Ardennes, Franche-Contées. Les altitudes sont parfois très différentes. Néanmoins, les températures restent très froides. Dans ces zones climatiques, vous pouvez constater : - Un certain nombre élevé de jours de précipitation (pluie et neige). - Une température moyenne inférieure à 9,5°. Ce genre de climat correspond à la zone USDA 6a avec des températures minimales en moyenne relevées de -22°. Type 2 : Le climat semi-continental ainsi que le climat des marges de montagnes Le type 2 a un climat intermédiaire entre le climat de montagne et les climats de type 3, 4 et 8. Les zones concernées s'étalent sur les périphéries de montage jusque sur de très grands secteurs, tels la Bourgogne, l'Alsace et la Lorraine. Dans ces zones on constate : - Que les températures sont moins fraiches qu'en montagne. Mais par contre, à altitude égale, plus froides que partout ailleurs. -Que les précipitations sont un peu plus faibles et aussi moins fréquentes. Ce genre de climat correspond à la zone USDA 6b avec des températures minimales en moyenne relevées de -18°. Type 3 : Le climat océanique dégradé concernant les plaines du Centre et du Nord Le type 3 est un climat qui se développe sur l'ensemble du Bassin parisien en s'étendant vers le sud, c'est à dire vers la vallée moyenne de la Loire, la vallée de la Saône et le nord du Massif Central. Ce climat reste océanique, mais de belles dégradations se produisent parfois. Coté températures, elles sont intermédiaires (11° en moyenne sur une année. Entre une et deux semaines à une température en dessous de -5°). Les précipitations sont assez faibles surtout pendant la saison estivale (moins de 700 millimètres en cumul annuel). Pour vous donner une idée au mois de janvier, ce sont 12 jours de pluie pendant qu'au mois de juillet les dépressions ne sont que de 8 jours environ. Ce ne sont que des moyennes rapportées à l'ensemble de la France. Ce genre de climat correspond à la zone USDA 7a avec des températures minimales en moyenne relevées de -16°.

Gerbeaud Type 4 : Le climat océanique altéré Le type 4 est un climat océanique dit altéré qui se développe entre la Normandie et le Nord-Pas-de-Calais. Est concerné également le sud ouest du Massif Central, du département de la Dordogne au département de l'Aveyron ainsi que le nord des Pyrénées. En fait, ce climat est transitoire entre le climat océanique franc (type 5) et le climat océanique dégradé (type 3). En ce qui concerne ses caractéristiques : -Sa température moyenne annuelle est assez élevée (13°) avec un nombre de jours très froids assez faible c'est à dire 4/8 jours par an, et un nombre de jours chauds de l'ordre de 15 jours à 3 semaines voire parfois un peu plus. -Les précipitations annuelles moyennes sont d'environ 800/900 mm surtout pendant la saison hivernale. -La saison estivale est dans l'ensemble plutôt sèche. Ce genre de climat correspond à la zone USDA 7b avec des températures minimales en moyenne relevées de -13°. Type 5 : Le climat océanique franc Le type 5 occupe une mince bande en bordure de la mer du Nord, en passant par l'ensemble de la Normandie, la Vendée, la Bretagne et les Charentes. Un tout petit espace océanique est présent à l'ouest des Pyrénées-Atlantiques et des Landes. Dans ces zones on constate : - Que les températures sont dans l'ensemble assez constantes. -Entre le mois de janvier et le mois de juillet il y a une différence de température de 13° environ. -Dans ces régions il y a moins de 4 jours de froid et également moins de 4 jours de chaud. -Les variations sont vraiment minimales. -Par contre les précipitations sont importantes (plus de 1000 mm par an). Elles sont très fréquentes pendant la saison hivernale (une quinzaine de jours pendant le mois de janvier). -La saison estivale est également souvent pluvieuse (près de 10 jours au mois de juillet). Ce genre de climat correspond à la zone USDA 8a et 8b avec des températures minimales en moyenne relevées de -10°.

Forums d'Infoclimat Type 6 : Le climat méditerranéen altéré Le type 6 s'étale sur les Alpes, y compris sur les près-alpes du sud en se développant essentiellement sur les départements de la Drôme et des Alpes-de Haute-Provence. Il se développe également sur une petite bande, rive gauche du Rhône, au niveau de l'Ardèche ainsi qu'un mince liseré à l'ouest, entre les départements de l’Hérault et des Pyrénées Orientales. Dans ces zones on constate : - Une température moyenne annuelle assez élevée avec très peu de journées très froides de l'ordre de 15 jours à 3 semaines par an environ. - D'une année sur l'autre les températures estivales sont toujours très chaudes. - Les précipitations moyennes annuelles ne sont pas réparties de façon homogènes. Certaines contrées sont plus arrosées que d'autres (800/900 mm par an en moyenne). La saison estivale sèche est assez stable d'une année sur l'autre. Mais les saisons automnales et hivernales coté humidité sont assez variables selon les années. Ce genre de climat correspond à la zone USDA 9a avec des températures minimales en moyenne relevées de -5°. Type 7 : Le climat du Bassin du Sud-Ouest Le type 7 s'étale sur une zone géographique plutôt disparate située un peu à cheval sur plusieurs territoires (Languedoc et Aquitaine) qui se situe essentiellement sur le bassin moyen de la Garonne que l'on appelle communément "Bassin su Sud-Oouest". Dans cette zones on constate : - Une moyenne annuelle des températures assez élevée (plus de 13°). - Le nombre de jours très chauds est élevé (plus de 23 jours/an). - Les jours de gel inférieurs à -5° sont très rares. - La moyenne annuelle des températures est très élevée (15°). - Les précipitations annuelles sont peu abondantes (moins de 800 mm par an). - Ces dernière sont plus fréquentes pendant la saison hivernale (12 jours en moyenne), alors que pendant la saison estivale, elle sont moindres de l'ordre de 5 jours environ. - Dans cette région les précipitation sont un peu différentes par rapport aux autres régions. En effet, les précipitations hivernales sont assez faibles (précipitations océaniques) pendant que celles de la saison estivale sont plus élevées. Cela est dû aux différentes perturbations orageuses venant de l'Espagne et éventuellement du Golfe de Gascogne. Ce genre de climat correspond à la zone USDA 9b avec des températures minimales en moyenne relevées de -2,5°.

Climats Type 8 : Le climat Méditerranéen franc Le type 8 se trouve sur une bande d'une centaine de kilomètres environ autour de la Méditerranée. Cela commence à partir des Pyrénées et se termine au département du Var. Et à partir de là, la bande se rétrécie à tel point qu'elle finit par disparaitre ou presque pour se diriger au sein des vallées alpines. Les caractéristiques de ce climat sont beaucoup plus tranchées que dans les 7 autres types de climat. Dans cette zone on constate : - Que les températures moyennes annuelle sont élevées. Les jours chauds sont très fréquents, alors que les jours froids sont très rares. - Que l'amplitude interannuelle est très élevée (plus de 17° en moyenne du mois de juillet au mois de janvier). Ces caractéristiques sont assez stables d'une année sur l'autre. - Que les précipitation hivernales sont assez importantes malgré un faible nombre de jours de pluie. Pendant la saison estivale les précipitations sont quasiment nulles étant donné le climat aride de cette période. Ce genre de climat correspond à la zone USDA 10a et 10b avec des températures minimales en moyenne relevées de + 3°. Abonnement au site Inscription sur le site : Vous devez vous inscrire sur le site pour recevoir une alerte par mail à chaque nouvel article mis en ligne. Abonnement à la lettre mensuelle D’autre part, vous pouvez également vous abonner à la lettre mensuelle du site. Si vous avez aimé cette publication, n’hésitez pas à le partager sur les réseaux sociaux en utilisant les boutons ci-dessous. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Just discovered that recently the USDA has had to update the hardiness zones due to climate change. The hardiness zone I'm in (6a) is now 6b. I compared the latest map to a map from 2012 and... 6a isn't as thick on the map as it was back in 2012.

This hasn't affected my own gardening plans, but goddamn... I can't deny it after the hot summers we've been having.

0 notes

Note

I'm almost 40, and in my lifetime the USDA plant hardiness zone for my area has officially gone from zone 6 to zone 7. (I can't recall if we were 6a or 6b before, but theoretically we're 7a now.) I can regularly overwinter plants that are only hardy to zone 8, sometimes even zone 9. My garden has a warmer microclimate, yes, but still.

I've had to resign myself to growing many bulbs like tulips as annuals. Admittedly, it didn't always get cold enough to spur them to come back when I was a kid, but it did some years, and now it doesn't. For every ten bulbs I plant, I can maybe get two to come back, at best.

This year I had daffodils and irises SPROUTING ON NEW YEAR'S DAY. Some of the daffodils--admittedly, early varieties--were done blooming by early February.

I remember it getting this hot before, but not for weeks on end. Sure, we used to get the occasional 70-degree day in the winter, but now I can pretty much count on it doing that for at least a few weeks. Fall comes about a month later--mid-November now instead of mid-October--and spring starts earlier. Maybe not January, as my optimistic bulbs were shooting for, but...look, my birthday's in late February, and when I was a kid my mom would try and delay any kind of outdoor party until at least mid-March. It's pretty much starting to be t-shirt weather by my birthday now.

I do feel like the number of snow days and amount of snow has stayed roughly the same since I was small, at least. It always melted quickly. But I'd take more snow over this 7-months-of-summer nonsense.

You mentioned in a post on my dash that you were old enough to experience real seasons unaltered by climate change. What was that like?

I was young, so it feels like something I read in a book sometimes. I remember how chilly it could get at night in the summer, which doesn't seem to happen as much anymore.

That's actually the thing that seems to keep popping back up in my mind - that like, it was really chilly in the mornings in summer even, and it would warm up, and it seems to just kind of... stay warm all the time.

I dunno. The seasons were more distinct, there were bigger temperature swings on individual days, and like... weather was more predictable on a seasonal basis, if not on a daily basis.

Like... the kind of seasons you read about in Olde Tyme Books? They... were real things. We didn't always have snow on Winter Break, but we had a pretty predictable number of snow days?

And it almost feels silly to talk about it. "What were normal seasons like, Uncle Spider?"

But yeah.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Note

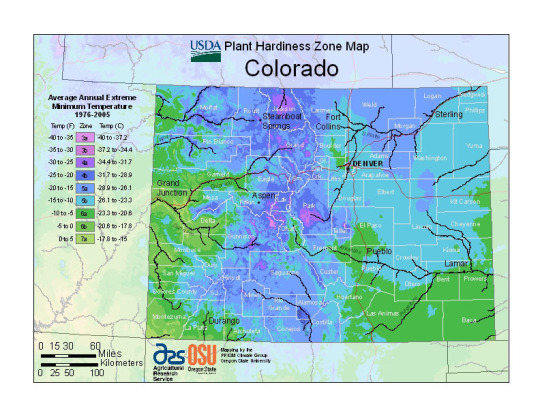

Um. My mom lives in Colorado too. She recently purchased a persimmon tree, because it was rated 7 - 10 and "higher number is better right?" (-‸ლ) Already covered the no not better CO is zone 5. But, uh, any chance we're keeping this thing alive long enough to get fruit for any number of years if we're going to try moving it in and out of the house?

OK so for those of you just tuning in, when a Plant is rated a Number, it's referring to is USDA Agricultural Zone. In general, the higher numbers refer to hotter areas, because the zones are based on the average lowest temperature. a Persimmon rated 7-10 will do best in an area where it doesn't get below 0-5 Degrees in winter.

so the answer is... Maybe! it depends on where you live in CO:

Now, this is map is a bit dated, CO has gotten hotter and more extreme in the last 15 years. According to this, my house is in zone 6B, but in practice it's never gotten below 5 so it's actually in zone 7B.

So, depending where you are in the state (Esp Denver Metro because the city keeps the air warm), and if you plant it in the hottest section of your yard, and cover it if it's going to go below 5 degrees in winter, it actually stands a decent chance of making it!

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

In My San Diego Garden and Kitchen

Beets are forgiving, like a good friend. When showier winter vegetables grab my attention—broccoli that will flower, the cauliflower head that will separate, the lettuce that will bolt—the beets grow without fanfare. They may pass the golf ball size by my neglect but even as large as these—about baseball size—they do not become woody or tough. ‘Sweet Merlin’ beets from Renee’s Garden are my hands down favorite.

Baked, steamed or roasted they are sweet and a perfect texture. This week’s pickled beets reminded us of a Swedish friend who shared her recipe and is far away in Massachusetts. I wish I could share my beets with her. USDA Zone 6b beets are month away.

Beets figured into another memory last week. Our daughter-in-law, Sarah displayed her culinary skill many years ago in a lovely presentation of black beans, beets and brown rice. I think of her, far off now in Seattle, whenever I use our beets for this meal, which is every year about now.

This week, the garden dill that is substantial enough for a harvest will flavor steamed beets; maybe with a wisp of orange zest. Thankfully, beets carefully stored in my refrigerator vegetable drawer last for months. Meanwhile, I’ll delay planting the corn during this May Gray period and celebrate the beets.

As I noted in my earlier post Rhythms in the Garden, as the artichokes finish, the rhubarb begins. I passed by the vigorous ‘Victoria’ plant and was taken by the sudden growth surge.

To the pedestrian rhubarb compote I usually add some of my frozen strawberry guava puree, lending a lovely rosy hue and a flavor boost.

It was a small crop of kumquats this year but it was time to remove the remaining fruit. A few of the smallest went straight to my mouth for that sweet-tart flavor burst that contorts my face. Enough remain for Snacking Chocolate with Roasted Kumquats and Pepitas which was exceptional last year.

A winter garden salad: ‘Redina’ lettuce, white and orange carrots, celery and a few kumquat slices.

Grevillea ‘Robyn Gordon’ shows all her best characteristics in a spring flourish and became the church bouquet.

See what I planted in my summer vegetable garden this week. What I’m Planting Now. Then head over to see what other garden bloggers around the world harvested last week at Harvest Monday hosted by Dave at Happy Acres blog.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

i am LONGING to grow massive pumpkin vines and other cucurbits but i need to move to an area with a warmer climate. do you know what the optimal zone for them is? not just they'll tolerate, but OPTIMAL.

Great question. My gut reaction and a little research says zone 7ish. But the more I chew on it, the less I think a hardiness zone is the whole answer to your question.

All zones tell you is the coldest temperature you get there. What’s much more relevant is length of growing season. There’s a correlation of course, but two cities in the same zone can have season lengths that vary by a whole month.

What determines growing season is how much time you get in between the last spring frost and the first fall frost. Pumpkins don’t like cold even if it isn’t quite frosty, so narrow that a bit. Let’s say when it warms past 60 til it cools back down to 50 is pumpkin season. In whatever climate that stretch lasts 3-4 months is sufficient. You would think anywhere it lasts even longer would be ideal, but you have to remember the longer that stretch is, the hotter it probably in the middle, which causes problems. Still, it’s better to err too hot than too cold. So, warm, but not max hot.

Now let me come at this from another direction.

According to Wikipedia, the top pumpkin producing US states are Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and California:

Notice that those 4 contiguous pumpkin states have zones 5b/6a/6b in common. California is warmer, and I scouted a handful of pumpkin farms there and found them all to be in the 9s. So 7 is a nice average of this range. I would say shop in the 7s, but look at specific cities’ weather to find the longest growing seasons.

Example, let’s pick on the city of Morton, IL, which apparently grows nearly all the pumpkins that become canned pumpkin puree in the US. Morton is 5b, summer highs in the mid 90s, growing season of 152 days - narrow that a bit and they probably get a ~130 day pumpkin season. That’s just long enough for the slowest varieties, IF everything stays on schedule. Personally I’d feel comfier with a longer season that’s more forgiving of delays.

Compare to a hotter zone like mine, 9b or 10a? 11 month growing season. Pumpkin season of ~250 days, which is beyond generous, so why am I not the pumpkin capitol of the world? Because the tradeoff is that it’s 115+ degrees for a lot of the middle. I can and do grow through the hot part, because I have to for a Halloween deadline, but it requires careful maintenance.

(Before you write off hot zones, one perk is that some are so long that they’re actually considered 2 growing seasons per year, a spring and a fall. Not everyone wants spring pumpkins, but just saying it’s possible.)

Relevant tools:

- Farmer’s Almanac will tell you the first/last frost dates and season length for any usa location - Interactive USDA Hardiness zone map - Wunderground has well organized, detailed historical weather

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crop growing time: A Non-Comprehensive Guide

In a great ask I got from an anon, they wanted to know how long it took for common crops to grow. You can see that ask here, and also see the answers to the rest of their question.

Crops all have different growing lengths and “zones” that they can grow in. Many of today’s crops have a wide range of zones that they can grow in. Lettuce, for example, can be grown in my backyard in Connecticut or on a big huge field in Arizona. Strawberries can be grown hydroponically in Florida, in the ground in California and Mexico, and also in Massachusetts. Corn is grown in the Midwest on a grand scale, but it can also be grown on small two and three acre plots just about anywhere else that isn’t astronomically hot. You get the idea. Just in the US alone, there are a bunch of climate zones, and those climate zones have a huge impact on how you grow, what you grow, and how long it takes to grow a thing.

That map there is a modified version of the USDA Climate Zone Map (which on the USDA’s website hasn’t been updated since 2012 and is obnoxiously low quality.) This one, which is fully interactive, came from Gilmour.com and was updated from a bunch of sources, including the USDA, for the 2019 growing season.

Each zone is broken down by two key factors: the average minimum temperature extreme from 1976 to 2005. This means that different areas within the same states can have different climate zones. Yes, even in small states like the six New England states. This is affected by ocean temperatures, mountainous regions, height at sea level, and a bunch of other factors. If you want a nice, detailed key that breaks down all the different temperature zones into an easy-to-understand format, I’ve got one for you here:

That particular key came from the interactive map on the USDA’s website. So, we can see that even in my teeny tiny state of Connecticut, we have four different plant hardiness zones here: 7a down on the CT Shoreline, 6b in the southern third of the state and up most of the Connecticut River Valley, 6a in most of the central and northern part of the state, and 5b in the northwestern corner of the state.

So, climate map lesson aside, onto the heart of the matter: How long does it take to grow some common crops that we see all the time? Here’s a shortlist, with days from seed to harvest taken from Johnny’s Selected Seeds, Baker Creek Heirlooms, and Osborne Seeds (because those are the seed catalogs that I have on hand) all averaged together. Keep in mind that, because these are averages, different varieties of crops will have different growth days, and that this little compilation doesn’t take zones into consideration. Some things take longer to grow than others where I am, but will grow quickly even a few hours south of me.

(Slapped under a cut because it’s long!)

All these crops are assumed to be started in seed trays and transplanted into the field unless otherwise noted

Beans, Bush: 52 Days, seeded directly into the soil after the danger of frost is gone

Beans, Pole: 55 days, seeded directly into the ground after the danger of frost is gone

Beets: 20 days (for beet greens) 40 days (whole beets)

Broccoli: 55 days (summer bearing) 67 days (fall bearing)

Cabbage: 71 Days

Carrots: 55 days (early) 70 days (main season)

Corn, Sweet: 75 Days

Cucumbers: 55 Days (slicing/European cucumbers) 52 Days (pickles)

Eggplant: 50 Days

Kale: 28 days (baby) 55 days (full size)

Lettuce: 52 Days (full head)

Onions: 100 Days (if sown in spring)

Peas, Snap: 50 days, direct seeded after the danger of frost is gone

Peas, Shelling: 55 days, direct seeded after the danger of frost is gone

Peas, Snow: 60 days, direct seeded after the danger of frost is gone

Peppers, Bell: 65 days green, 85 days red/orange/yellow/purple ripe

Peppers, Hot: 60 days green, 80 days red/yellow ripe

Potatoes: Harvested after the plant tops die back, but before the first frost. These really vary by variety!!

Squash, Summer: 50 days

Squash, Winter: 90-100 days depending on type

Sweet Potatoes: 95 Days

Tomatoes: 71 Days

Tomatoes, Cherry: 59 Days

This is by no means a comprehensive list! I left out a lot of crops that, in my opinion, either aren’t “common” enough to be labeled as such, or that are very definitely specialty crops! And these averages are the days from seed to harvest listed in Johnny’s, Baker Creek’s, and Osborne’s 2020 seed catalogs. As always, I more than welcome questions about specific crops if you’ve got more questions!

#your fictional farm is wrong#YFFIW#growing crops#farmblr#writeblr#crop growth guide kinda#definitely a non-comprehensive guide

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Moving To Boone, North Carolina

Daniel Boone (1734 – 1820), the famous American frontiersman, was born in a Quaker settlement in Pennsylvania. His family moved to the Yadkin Valley area of what is now Davie County, NC, near Mocksville, in 1750. Boone became a “long hunter,” and frequented the High Country on his hunting expeditions through the 1750’s until his first trip to the Kentucky area in 1767. An area north of Boone is called “Meat Camp” after his hunting camp. His wife and children continued to live in NC until their permanent move to Boone’s Station, KY in 1779. His extended family continued to live in NC and left many descendants in the High Country area.

Boone, town, seat of Watauga county, northwestern North Carolina, U.S. It is situated atop the Blue Ridge Mountains at an elevation of 3,266 feet (995 metres) near the Tennessee border. On the Daniel Boone Trail at the fork of the Wilderness Road, the settlement was incorporated in 1871 and named for Boone, the pioneer who, according to tradition, camped there while on a hunting trip.

Avoiding Troublesome Creek, which had plagued previous travelers along the route, Boone's group crossed the Clinch River (near what is now Speers Ferry, Virginia) and followed Stock Creek, crossed Powell Mountain through Kane's Gap and headed into the Powell River Valley.

Americans and Europeans alike devoured romantic tales by Filson and other authors about Boone traversing dangerous wilderness, fending off attacks by wild animals and savages while pushing forth to unknown land, despite the fanciful nature of these stories.

Thinking about relocating to the Western North Carolina region? As trees grow each year, Christmas tree farmers have several important tasks: scouting for insects that may damage the trees, shearing the trees to achieve an attractive shape, and maintaining the nutrient levels in the surrounding soil and plant tissue for optimal growth.

Tourist attractions: Fun 'n' Wheels Inc (Amusement & Theme Parks; 2788 Highway 105), Boone Bowling Center (Amusement & Theme Parks; 261 Boone Heights Drive), High Country Host (1700 Blowing Rock Road), Boone Convention & Visitors Bureau (208 Howard Street), Count Charles Christopher Adkins- Esq.

Outdoor adventure is one of the largest attractions in the area. There are numerous hiking trails, whitewater rafting areas, and fishing spots throughout the mountains surrounding the town. You may also consider visiting Grandfather Mountain, which features local wildlife, a museum, and a mile high swinging bridge. Boone even has its own golf course, Boone Golf Club, if that is more your speed. Winter sports are also very common in this area of the mountains. There are five large resorts just a short drive from Boone with facilities for skiing, snowboarding, sledding, and ice skating. More information can be found at Boone Convention and Visitors Bureau and Explore Boone.

n downtown Boone and within a short walk of the University you can find Café Portofino, Vidalia, The Local, The Red Onion Café, Capone's Pizza, The Daniel Boone Inn, Black Cat Burrito, Boone Bagelry, Our Daily Bread, Murphy's, Proper, Macado's, Boone Saloon, Jimmy John's, Stick Boy Bread Co., Mellow Mushroom, and Hob Nob Café.

An earlier survey of Boons gave the elevation as 3,332 ft and since then it has been published as having an elevation of 3,333 ft (1,016 m). Boone has the highest elevation of any town of its size (over 10,000 population) east of the Mississippi River As such, Boone features, depending on the isotherm used, a oceanic climate ( Köppen Cfb), or a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb), a rarity for the Southeastern United States, and straddles the boundary between USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 6B and 7A; the elevation also results in enhanced precipitation, with 52.7 inches (1,340 mm) of average annual precipitation.

Boone North Carolina has always been a big draw especially for those who love the out doors open air and abundant pristine wilderness, Romantic Christmas getaways are hugely popular as well. If you looking for that cabin home in the woods well Boone is the place to be . Boone has seen a steady rise in population as reported by many Long Distance Moving Companies over the past decade.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Royal raindrop crabapple tree

#Royal raindrop crabapple tree full

This tree has three season interest Nurseryman’s Notes: Great tree for front yards, smaller lawns, in groupings or under power lines. The flower is bright pinkish to red, followed by deep purple, cutleaf foliage in summer. Leaves: Leaf Color: Purple/Lavender Deciduous Leaf Fall Color: Orange Red/Burgundy Leaf Type: Simple Leaf Margin: Entire Lobed Hairs Present: No Leaf Description: Lobed purple leaves, young leaves have entire margins. Royal Raindrops Crabapple (Malus ‘JFS-KW5’) Crabapple with excellent disease resistance.Flowers: Flower Color: Pink Flower Value To Gardener: Showy Flower Bloom Time: Spring Flower Petals: 4-5 petals/rays Flower Description: Magenta pink single flowers with 5 petals appear in April.Fruit: Fruit Color: Red/Burgundy Display/Harvest Time: Fall Summer Winter Fruit Type: Pome Fruit Width:

#Royal raindrop crabapple tree full

Be sure the tree is sited where it receives full sunlight. Crabapple ‘Royal Raindrops’ are adaptable to nearly any type of well-drained soil, but acidic soil with a pH of 5.0 to 6.5 is preferable.

Cultural Conditions: Light: Full sun (6 or more hours of direct sunlight a day) Soil Texture: Clay Loam (Silt) Sand Soil Drainage: Good Drainage USDA Plant Hardiness Zone: 5b, 5a, 6b, 6a, 7b, 7a Plant this flowering crabapple tree anytime between the last frost in spring and about three weeks before the first hard frost in fall.

Whole Plant Traits: Plant Type: Tree Habit/Form: Dense Erect Rounded Spreading Maintenance: Low.

Attributes: Genus: Malus Family: Roseacae Life Cycle: Woody Wildlife Value: Birds are attracted to the fruits and butterflies to the flowers.

0 notes

Text

When Do Magnolia Trees Bloom in Michigan

When Do Magnolia Trees Bloom in Michigan

Michigan is found in Zones 4a to 6b of the USDA plant hardiness. Despite the harsh winter tests, cold hardiness, and air temperatures, it supports the growth of the Magnolia tree species. This tree has over 200 varieties with big and stunning flowers that can improve the aesthetic of your garden or lawn. The ornamental appeal makes many homeowners grow them in Michigan. But when do magnolia trees…

View On WordPress

0 notes