#Trump’s Indo-Pacific Strategy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

الخطابات والممارسات الأمريكية تجاه منطقة المحيطين الهندي والهادئ - من أوباما إلى بايدن (منظور بنائي)

الخطابات والممارسات الأمريكية تجاه منطقة المحيطين الهندي والهادئ – من أوباما إلى بايدن (منظور بنائي) الخطابات والممارسات الأمريكية تجاه منطقة المحيطين الهندي والهادئ – من أوباما إلى بايدن (منظور بنائي) المؤلف: Nourhan Aboelfadl المستخلص: تطورت استراتيجية الولايات المتحدة لإعادة التوازن نحو آسيا بشكل جوهري، خاصةً في ظل ت��ير للتحالفات الإقليمية في المنطقة. ولذلك يست��عي التوجه الأمريكي المتقلب…

#A Constructivist Perspective#Biden’s Indo-Pacific Strategy#China’s rise#China’s threat to the US#Indo-Pacific#Obama’s Rebalance#Trump’s Indo-Pacific Strategy#US#US construction of the Indo-Pacific.#US containment of China#US discourse#US Foreign Policy#US- Asia relations#الولايات المتحدة؛ إعادة التوازن لأوباما؛ إستراتيجية ترامب للمحيطين الهندي والهادئ؛ إست

0 notes

Text

الخطابات والممارسات الأمريكية تجاه منطقة المحيطين الهندي والهادئ - من أوباما إلى بايدن (منظور بنائي)

الخطابات والممارسات الأمريكية تجاه منطقة المحيطين الهندي والهادئ – من أوباما إلى بايدن (منظور بنائي) الخطابات والممارسات الأمريكية تجاه منطقة المحيطين الهندي والهادئ – من أوباما إلى بايدن (منظور بنائي) المؤلف: Nourhan Aboelfadl المستخلص: تطورت استراتيجية الولايات المتحدة لإعادة التوازن نحو آسيا بشكل جوهري، خاصةً في ظل تغير للتحالفات الإقليمية في المنطقة. ولذلك يستدعي التوجه الأمريكي المتقلب…

#A Constructivist Perspective#Biden’s Indo-Pacific Strategy#China’s rise#China’s threat to the US#Indo-Pacific#Obama’s Rebalance#Trump’s Indo-Pacific Strategy#US#US construction of the Indo-Pacific.#US containment of China#US discourse#US Foreign Policy#US- Asia relations#الولايات المتحدة؛ إعادة التوازن لأوباما؛ إستراتيجية ترامب للمحيطين الهندي والهادئ؛ إست

0 notes

Text

(Al-Akhbar English) Red Scare Reborn: US Anti-Communist Push and Global Consequences

Ali Awwad

Between 1917 and 1920, the United States grappled with intense fear stemming from the Russian Revolution, which ignited anxieties about the spread of communism and anarchism. This fear led to widespread repression against leftists, unionists, and immigrants, culminating in arrests, investigations, and a climate of suspicion. A similar wave of paranoia resurfaced in the 1950s during the Cold War, known as the “Second Red Scare.” Senator Joseph McCarthy spearheaded this period with his aggressive campaign against alleged communists, expanding the witch hunt beyond politicians to include intellectuals, artists, and civil rights leaders. These events were justified under the guise of national security but were ultimately aimed at enforcing ideological conformity and silencing progressive voices.

Now, with the election of Donald Trump as the 47th US President, echoes of this Cold War legacy resurface. Trump’s administration is pushing the “Decisive Education on Communism” bill (H.R. 5349), designed to implement an anti-communist curriculum in schools. While ostensibly focused on educating students about communism’s “crimes,” this bill mirrors past repressive efforts, using education as a tool for cultural censorship and ideological control. The bill, spearheaded by Representative Maria Salazar, has faced opposition to amendments that would include education on fascism and other oppressive ideologies, highlighting its partisan agenda.

This bill comes amid growing support for leftist movements among young Americans, particularly in solidarity with Palestinians. The rise of these movements has sparked anger from the American right, which is increasingly challenged by shifting public opinions on US foreign policy. Opinion polls reveal that younger generations are more critical of authority and increasingly open to socialist principles. This shift in political consciousness is seen as a direct threat to established power structures, prompting fears of a new “Red Scare” targeting left-wing movements.

Parallel to these developments, conservative think tanks like the Heritage Institute have launched initiatives such as the Esther Project, which seeks to criminalize political activism against Israel and label Palestinian solidarity as part of a broader anti-capitalist agenda. These efforts aim to dismantle these movements through legal and political means, employing tactics reminiscent of McCarthyism. Trump's supporters plan to expand this repression to education and media, purging institutions that oppose right-wing ideology, and even considering military intervention against protesters, as seen in the 2020 George Floyd protests.

While the bill's focus remains on combating communism, its broader aim is to prevent China from challenging US global hegemony. The "communist threat" narrative is being used to justify escalating tensions with China, through economic sanctions and military alliances in the Indo-Pacific. This strategy not only aims to curb China’s rise but also seeks to compel other nations to align politically with the US These actions could lead to a new global conflict, marked by competition for influence, resources, and technology. As tensions rise, nations will be pressured to take sides, increasing international polarization. However, in the midst of this global upheaval, there may also be opportunities for change, as history has often shown.

Full article in Arabic: https://al-akhbar.com/culture/816676

#palestine#free palestine#gaza#free gaza#jerusalem#current events#yemen#tel aviv#israel#palestine news#biden#trump#anti capitalism#anti communism

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Former Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen emphasized the importance of U.S. support for Ukraine during the Halifax International Security Forum on Nov. 23, urging Washington to prioritize helping Kyiv despite the rising threat of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

"They should do whatever they can to help the Ukrainians," Tsai said, according to a Politico report. "We [Taiwan] still have time."

Tsai’s comments came after U.S. Indo-Pacific Command chief Adm. Samuel Paparo acknowledged that aiding Ukraine has begun to strain the U.S. military’s capacity to prepare for potential conflict in Asia. Paparo highlighted the depletion of critical weapon stockpiles, including Patriots and air-to-air missiles.

During her Halifax appearance, Tsai argued that Ukraine's success against Russian aggression would serve as a global deterrent.

"A Ukrainian victory will serve as the most effective deterrent to future aggression," she said.

Taiwan has increased its defense spending by 80% over the past eight years, reaching $19 billion in 2024. However, Tsai dismissed calls for Taiwan to raise its defense budget to 10% of GDP, a suggestion made by U.S. President-elect Donald Trump. "We would have some difficulty accepting an arbitrary figure," she said, according to Politico.

While the Biden administration has consistently defended its ability to balance support for Ukraine and preparations for a conflict with China, Trump allies argue otherwise. Tsai remained cautious about Taiwan's defense strategy under Trump’s presidency, declining to comment on potential major arms purchases in early 2025.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lula in China: The End of Brazil’s Flirtation With the Quad Plus

The new Lula administration has brought Brazil’s China policy back in line with its traditional approach, after the anti-China rhetoric of Jair Bolsonaro.

In 2018, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi dismissed the idea of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), formed by the United States, Japan, India, and Australia, asserting that it would “dissipate like sea foam.” The Quad, created to facilitate the convergence of the four countries in terms of policies toward the Indo-Pacific, not only proved to be resilient over time but also intensified its activities in the region under both former U.S. President Donald Trump (2017-2021) and current President Joe Biden. During this period, the consultation between the group members went from being a biannual foreign ministerial dialogue to head of government-level consultations.

Analysts introduced the term Quad Plus in 2020 to describe a minilateral dialogue of states that extends the Quad beyond the four lynchpin democracies. However, while the term “Quad Plus” is not officially endorsed by Washington, Canberra, New Delhi, and Tokyo, it has become shorthand for non-Quad members that are closely cooperating with the group. That list includes other important U.S. partners such as Brazil, South Korea, Vietnam, Israel, New Zealand, and France. The idea originated during the uncertainty and global tensions at the time of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The first concretization of the Quad Plus framework took place on March 20, 2020, when then-U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Stephen Biegun proposed a Quad meeting including Vietnam, New Zealand, and South Korea, which aimed to enable an exchange of assessments of the national pandemic situation of participant nations and align their responses to contain its spread. Later, a foreign ministers-level meeting in May 2020 with the participation of Israel, South Korea, and Brazil consolidated the Quad Plus with a global outlook. The extended initiative also materialized for the first time in the security realm in April 2021, when France led the La Pérouse Naval Exercise in the Bay of Bengal.

The unstated motivation of the Quad is the shared concern among the four original members about the rise of China’s international political and economic clout and the desire to check Beijing’s increasing military activities in the South and East China Seas. At the time, Brazil seemed to share such wariness in relation to Beijing since it was under the Jair Bolsonaro administration (2019-2022). The far-right former Brazilian Army captain aligned the country’s foreign policy to Washington’s interests. Bolsonaro also embraced fierce anti-Chinese rhetoric due to his distaste for Communism and China’s growing investments in sensitive Brazilian sectors like agriculture, meatpacking, and mining. Bolsonaro insinuated that China had engineered the COVID-19 virus and purposefully spread it worldwide to benefit from the pandemic economically.

Despite contentious relations with the East Asian power, Brasília failed to concretize a rapprochement with the Quad. It happened for three main reasons. First, Brazil is clueless about the Indo-Pacific. It lacks a full-fledged long-term strategy toward the region and has failed to include the very term “Indo-Pacific” in its official vocabulary. Brazil’s geographical position, facing the South Atlantic Ocean, and its limited capacities of naval power projection beyond marginal seas make it unlikely that Brasília will be able to ensure the freedom of navigation in a region half a world away. For example, among the last seven IBSAMAR Naval Exercises, carried out with India and South Africa, Brazil deployed an offshore patrol vessel to Goa only once.

Continue reading.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

full article text under readmore

CANADIAN INDIGENOUS GROUPS SEEK DEALS WITH CHINA DESPITE SECURITY FEARS

Canada’s indigenous communities are seeking deals with China that could give Beijing access to the country’s natural resources, despite warnings from Canadian security services over doing business with Xi Jinping’s government.

This week the Canada China Business Council indigenous trade mission is in Beijing to discuss potential energy and other business deals in a trip that could put Canada’s national “reconciliation” with its First Nation communities at odds with its national security priorities.

Karen Ogen, the trade mission’s co-chair and chief executive of the First Nations Liquefied Natural Gas Alliance, said her goal on the trip, which starts on Wednesday, was to sell LNG for the benefit of the Wet’suwet’en communities in Canada’s western province of British Columbia_._

“We’ve been oppressed and repressed by our own government,” she said. “I know the history with China is not good but we have an understanding of what we need and what they need.”

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau came to power in 2015 pledging to promote “economic reconciliation” with indigenous, or first nation, communities, which for decades saw their ancestral lands and resources exploited by European settlers and their culture belittled and attacked.

He committed to spend billions on business, economic and social programmes in an effort to reduce inequalities between indigenous and non-indigenous Canadians. The government also signed a number of land-sharing treaties with first nations communities giving them rights over the natural resources in their territories — subject to federal foreign investment rules.

Despite the pledges, many first nations communities remain socially and economically deprived. Earlier this year, a UN special rapporteur said Canada’s failure to provide First Nations reserves with clean drinking water and sanitation constituted a human rights violation.

China has spotted an opportunity in the sometimes fraught relations between Canada’s national and provincial governments and indigenous groups.

In 2021, shortly after Canada imposed sanctions on Beijing over the treatment of its Uyghur population, Chinese officials began to object to the “systemic violations of Indigenous people’s rights by the US, Canada and Australia” at the UN’s Human Rights Council.

“The PRC tries to undermine trust between Indigenous communities and Canada’s government by advancing a narrative that the PRC understands and empathises with the struggles of Indigenous communities stemming from colonialism and racism,” said a spokesperson for Canada’s security intelligence service.

A 2023 CSIS report accused China’s government of employing “grey zone, deceptive and clandestine means” to influence Canadian policymaking, including Indigenous communities.

“China knows how sensitive Indigenous reconciliation is to the Trudeau government,” said Phil Gurski, a former CSIS intelligence analyst.

Relations between Canada and China have deteriorated significantly in recent years. An official inquiry reported in May that China had directly meddled in Canada’s 2019 and 2021 elections and was “the most active foreign state actor engaged in interference” in the country. Ottawa’s 2022 Indo-Pacific strategy also described China as “increasingly disruptive”.

As a result, Canada’s policy towards Beijing is becoming more in line with that of the US, with Ottawa imposing tariffs on Chinese goods and forcing Chinese-owned social media company TikTok to close its Canadian office.

This realignment is expected to become even more important with the election of Donald Trump south of the border. “Canada would be expected to enforce harsher trade governance with China,” said Marc Ercolao, an economist with TD Bank.

But CSIS remains concerned over Beijing’s possible access to resource-rich areas or geopolitically important waterways and regions such as the Arctic through First Nations groups.

“It not only undermines the government but is a way to potentially embarrass them on Canada’s past,” said Gurski.

But Matt Vickers, from Sechelt Nations land in Canada’s western province of British Columbia, who first visited China in the 1990s and is part of the CCBC delegation heading to Beijing this week, rejected the concerns of the security services.

“China now understands that for any major project to receive approval in Canada, you need First Nation consent, and not only consent but the First Nations require a majority equity play in those projects,” he said.

The CCBC is a bipartisan organisation consisting of Canada’s biggest companies, including Power Corp, which is the main sponsor of the Indigenous event.

This week’s trip marks the third time a group of Indigenous officials has travelled with the council to China in an effort to identify export markets, sources of capital and potential tourism projects.

“These missions have been developed in the spirit of reconciliation and collaboration, to help delegates better understand how China’s economy and economic development influences its desire for imports and investment opportunities,” said Sarah Kutulakos, executive director of the CCBC.

The Chinese embassy in Ottawa declined to comment on CSIS’s security concerns over deals with First Nations communities but said: “We are pleased to see Canadians from all walks of life, including Indigenous Canadians, proactively engage in pragmatic co-operation with China.”

Deteriorating relations between Ottawa and Beijing meant this year’s CCBC meeting would likely be “sombre”, said former Canadian ambassador to China Guy Saint-Jacques.

First Nations leaders should have “very limited expectations” from the trip. “I don’t expect big business coming out of it,” he said.

But Ogen, of the First Nations LNG Alliance, said she would put the controversy surrounding the trip to Beijing aside. “I . . . look at the global energy sector, China’s need for our gas, and how I can make the best deal for my people,” she said.

ok ppl are saying this is funny as in "fuck around and find out" but completely honestly this could be laying the groundwork for more advanced warfare between canada and its first nations in the 21st century. like the fact that first nations are finding political alliances outside of major western powers at the express disapproval of the settler government is a big deal. am i the only one seeing how this is a big deal

793 notes

·

View notes

Text

While I don’t intend to follow most of Trump’s appointments closely at this point, there are areas in which I have a particular interest. National Security and the Deep State more generally is obviously one of those areas, and that’s an area where the shape of Trump 2.0 can be said to be still evolving. The Gaetz withdrawal and uncertainties regarding where Pam Bondi will stand on critical NatSec issues as AG is one consideration, and the uncertainty regarding a new Director FBI is another. The good news is that, once again, the Trump team is denying that Mike Rogers is being considered for the FBI spot.

Another interesting NatSec pick has also come to light—Alex Wong as Deputy National Security Adviser. On paper Wong has strong qualifications in the NatSec field. He served in Trump 1.0 in important NatSec areas:

Wong oversaw regional and security affairs for the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs (EAP), including U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy. On December 1, 2017, was appointed deputy assistant secretary for North Korea in the EAP. He was dual-hatted as the deputy special representative for North Korea. In these roles, he managed all diplomatic and technical policy on North Korea in support of the U.S. Special Representative for North Korea, Stephen Biegun.

Of special interest is the appointment of Marty Makary as head of FDA. Makary has a mixed record with regard to the Covid Hoax. Overall it can be termed moderate, in a strictly relative sense—or, perhaps, “mixed bag” would be better. You need to read between the lines of the Wikipedia presentation at the link, but it appears that Makary’s positions evolved from establishment views to more critical views regarding the public health response to Covid. While he was an early advocate for lockdowns, masking and mRNA injections, by December 2021 he was referring to Omicron as “nature’s vaccine.” He was also an early advocate for getting people back to work and back to school. So, mixed.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Makary was an early advocate for universal masking to control the pandemic and recommended vaccines for adults. However, he was an outspoken opponent of broad COVID-19 vaccine mandates and, in late 2021 and early 2022, non-pharmaceutical interventions [i.e., masking etc.] meant to reduce transmission in schools and universities.

…

Makary stated in a February 2021 op-ed in The Wall Street Journal that "At the current trajectory" in the United States COVID-19 would "be mostly gone by April" 2021, primarily as a result of naturally acquired immunity.

…

Makary considers himself pro-vaccine but has also criticized vaccination mandates for populations other than healthcare workers.

…

Makary is the author of the New York Times Best Selling book Unaccountable, in which he proposes that common sense, physician-led solutions can fix the healthcare system.[56][57] … The Price We Pay, was released in 2018 and describes how business leaders can lower their health care costs and explores the grass-roots movement to restore medicine to its noble mission.[62] Makary is also the editor of the surgery textbook "General Surgery Review".[63] His latest book, Blind Spots, urges readers to think critically about today's medical consensuses.[64]

So, while it seems impossible to predict what approaches he will take as head of FDA, he at least appears willing to venture into regions outside the medical establishment’s approved opinions. Make of it what you will. He’ll be going up against Big Pharma if he attempts to reform FDA, which is heavily funded by Big Pharma and is deeply corrupt. The real question is whether reform measures will be backed by Trump. Trump’s positions are, at best, unclear at this point. No doubt will get some clarity during confirmation hearings.

1 note

·

View note

Text

[ad_1] The “America First” trade policy promoted by upcoming US President Donald Trump has far-reaching implications for global trade and geopolitics. According to a report by Motilal Oswal, this policy carries mixed outcomes for exporters worldwide because it is designed to prioritize US manufacturing by reducing imports, particularly from China. Trump’s policies present opportunities and challenges for India. The Indo-Pacific defense strategy could strengthen US-India collaboration, opening doors for Indian businesses in sectors such as pharmaceuticals and defense. It said, “Indian businesses in sectors such as pharmaceuticals and defence might also find new opportunities, especially if US- India collaboration strengthens… Emerging markets face a mixed bag of challenges and opportunities.” Additionally, anticipated US corporate tax cuts could boost IT spending, benefiting India’s IT sector. However, a stronger dollar and potential tariffs on Indian exports could strain its trade balance. Another significant concern is the impact of increased tariffs on US exports. Key industries like agriculture and technology risk losing competitiveness in global markets if trading partners impose retaliatory tariffs. The report said, “Increased tariffs might prompt retaliatory measures from trade partners, potentially affecting US exporters in sectors like agriculture and technology.” The report also highlighted that India may find a silver lining in global supply chain realignments, particularly in technology areas like AI and semiconductors, driven by the “China+1” strategy. For instance, the European Union (EU) may levy duties on American goods, potentially hampering the automotive and steel industries. These measures could slow growth in Europe and disrupt global trade patterns. Emerging markets face a dual challenge. While higher tariffs and a stronger dollar may escalate export costs for sectors like IT and pharmaceuticals, some countries, like Mexico, stand to gain by attracting manufacturing that might otherwise remain in China. The report highlighted that geopolitically, Trump’s approach will likely escalate tensions with China and reshape alliances. Countries like Japan and South Korea may reconsider their strategies, while the EU might strive for self-reliance, fostering new alliances outside US influence. [ad_2] Source link

0 notes

Text

[ad_1] The “America First” trade policy promoted by upcoming US President Donald Trump has far-reaching implications for global trade and geopolitics. According to a report by Motilal Oswal, this policy carries mixed outcomes for exporters worldwide because it is designed to prioritize US manufacturing by reducing imports, particularly from China. Trump’s policies present opportunities and challenges for India. The Indo-Pacific defense strategy could strengthen US-India collaboration, opening doors for Indian businesses in sectors such as pharmaceuticals and defense. It said, “Indian businesses in sectors such as pharmaceuticals and defence might also find new opportunities, especially if US- India collaboration strengthens… Emerging markets face a mixed bag of challenges and opportunities.” Additionally, anticipated US corporate tax cuts could boost IT spending, benefiting India’s IT sector. However, a stronger dollar and potential tariffs on Indian exports could strain its trade balance. Another significant concern is the impact of increased tariffs on US exports. Key industries like agriculture and technology risk losing competitiveness in global markets if trading partners impose retaliatory tariffs. The report said, “Increased tariffs might prompt retaliatory measures from trade partners, potentially affecting US exporters in sectors like agriculture and technology.” The report also highlighted that India may find a silver lining in global supply chain realignments, particularly in technology areas like AI and semiconductors, driven by the “China+1” strategy. For instance, the European Union (EU) may levy duties on American goods, potentially hampering the automotive and steel industries. These measures could slow growth in Europe and disrupt global trade patterns. Emerging markets face a dual challenge. While higher tariffs and a stronger dollar may escalate export costs for sectors like IT and pharmaceuticals, some countries, like Mexico, stand to gain by attracting manufacturing that might otherwise remain in China. The report highlighted that geopolitically, Trump’s approach will likely escalate tensions with China and reshape alliances. Countries like Japan and South Korea may reconsider their strategies, while the EU might strive for self-reliance, fostering new alliances outside US influence. [ad_2] Source link

0 notes

Text

*Donald Trump's* historic return to the White House marks the beginning of a *complex geopolitical* era, with profound *implications for India and global diplomacy.*

For India, this development presents both opportunities and challenges as it navigates a more *assertive U.S. foreign policy.*

Trump's victory may enhance India's role in the *Indo-Pacific region and open new avenues* in technology and defense collaboration, yet his *unpredictable leadership style* requires strategic foresight.

Internationally, Trump's resurgence signals a potential rise in protectionist policies, straining traditional alliances and deepening geopolitical divisions.

As nations recalibrate their foreign strategies, the global stage is set for a new phase of *economic nationalism,* with all eyes on the unfolding *dynamics of the Trump presidency.*

http://arjasrikanth.in/2024/11/08/trumps-white-house-reboot-indias-gamble-in-the-new-america-first-showdown/

0 notes

Text

‘War Criminal United States’ Missile Plan In ‘Puppet, War Criminal & Genocidal Germany’ Dangerous Subservience

— Sevim Dagdelen | July 21, 2024

Illustration:Liu Rui/Global Times

On the sidelines of the recent NATO summit in Washington, the Biden administration announced that beginning in 2026, the US is to position new weapons in Germany capable of hitting targets within 2,700 kilometers.

While still in Washington, the German chancellor agreed to this future deployment in a joint statement. Yet no prior discussion about these new US rockets and cruise missiles was held in the Bundestag or in the Committee on Foreign Affairs, nor was there any debate on the topic in the wider German public sphere.

This development ought to be highly controversial, especially as the missile systems in question are equipped to reach targets deep inside Russia - the linear distance between Berlin and Moscow is a mere 1,600 kilometers. Russia has declared its intention to respond accordingly.

The US' purported deterrent in fact poses a massive threat to the security of Germany's population. The US treats our country as if it is nothing but an aircraft carrier. The subservience with which the federal government accepts and waves through decisions by the US is actually frightening. When he was sworn into office, the chancellor committed himself to protecting the German people from harm. But by allowing the US to place its missiles in Germany, his willingness to uphold this obligation has been thrown into doubt.

The planned long-range missile deployment is just one example of a series of decisions the US has made in an attempt to push Germany onto the frontline of its conflict with Russia. Other examples include the US putting pressure on Berlin to ship its Leopard tanks to Ukraine, which factored in a predictable, and brutal, Russian reaction. In the meantime, the NATO mission in Ukraine has established its headquarters in the German city of Wiesbaden, near the banking centre of Frankfurt am Main. Stationing long-range missiles in Germany under US command - the attendant infrastructure will likely be partly financed by German tax payers - only inflames the situation further.

The aim is clear, to bring Germany closer to a direct military confrontation with Russia, or at least to force Berlin to spend a greater share of its resources on the proxy war with Moscow. Washington appears to have calculated that if Germany keeps Russia busy in Europe, the bulk of its own military capacity can be shifted over to its efforts to contain China in East Asia and the Indo Pacific.

It must be stressed that the current decision to station US missiles in Germany was only made possible by the US' unilateral withdrawal from the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) under US President Trump in 2019 (the US alleged that Russia had breached the terms of the treaty).

Since 1987, the INF had barred the manufacture and deployment of all ground-launched intermediate-range missiles capable of hitting targets in a range of 500 to 5,500 kilometers.

The question must be raised: Is the current US deployment of missiles in Germany one component of a long-planned strategy of escalation, responsible for both Washington's withdrawal from the INF and NATO's eastward expansion? This interpretation would be consistent with the fact that the US had evidently already begun developing new intermediate-range missiles prior to the termination of the INF. As early as 2017, an initial Multi-Domain Task Force (MDTF) was established in Wiesbaden, allegedly for test purposes only. The 2021 reactivation of the 56th US Artillery Command may also be considered a preparatory step toward escalation. During the Cold War, this Command was responsible for US Pershing missiles; now it will oversee the new US long-range deployments.

The US' plans today are not identical to its previous Cold War strategy. However, the shorter warning period entailed by new hypersonic missiles, for example, means that contemporary US deployments are distinct from the intermediate-range missiles stationed in Germany in the earlier era. Not surprising, Russia perceives the new weapons systems as a significant threat - "a knife to the throat". The speed of the new hypersonic missiles in particular creates a far more dangerous situation than what prevailed during the Cold War, including potentially greater risk of irreversible consequences due to false alarms. As such, US long-range missile deployments increase the risk of nuclear war enormously, amid a new nuclear arms race that is already underway.

The central problem facing all NATO allies - those formal members of the alliance and those included through bilateral agreements - is this: As with the dependent kingdoms on the eastern border of the Roman Empire two millennia ago, allies must forfeit their sovereignty and subordinate their foreign policy to the security interests of the hegemon. All the while, an illusion is to be maintained that their sovereign interests are indeed served by such an arrangement with the US, if only as a collateral benefit. But this wishful thinking is increasingly difficult to sustain.

Instead of cultivating diplomacy, the US' NATO allies have followed Washington's example, and attempted to dictate to other countries what is and what is not permissible. Given the rapid economic rise of the BRICS states, such a neocolonial approach, however, appears to be doomed.

In Germany, the focus must now turn to mobilising society against the stationing of US missiles within its borders. Since this decision calls into question the very security of the German population, a referendum must be held urgently to determine whether the polity accepts it. Even more pressing is finding an answer to the general question of how peace and democratic sovereignty may be defended in today's Germany, given the US' evident willingness to put its own allies at such grave risk.

— The Author, Sevim Dagdelen, is Foreign Policy Spokesperson for the "Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance" (BSW) grouping in the German Bundestag, and is the BSW grouping coordinator on the Committee on Foreign Affairs.

#‘War Criminal United States 🇺🇸’#‘Puppet War Criminal & Genocidal Germany 🇩🇪’#Missile Plan | Deployment | Germany 🇩🇪#North Atlantic Terrorist Organization (NATO)#Russia 🇷🇺#Ukraine 🇺🇦#Sevim Dagdelen | Foreign Policy Spokesperson#Global Times | China 🇨🇳

0 notes

Text

BBC 0432 4 Aug 2023

12095Khz 0357 4 AUG 2023 - BBC (UNITED KINGDOM) in ENGLISH from TALATA VOLONONDRY. SINPO = 55445. English, dead carrier s/on @0357z then ID@0359z pips and Newsday preview. @0401z World News anchored by Neil Nunes. Former US President Donald Trump has pleaded not guilty in a Washington DC court to conspiring to overturn his 2020 election defeat. During a short arraignment, he spoke softly to confirm his not-guilty plea, name and age, and that he was not under the influence of any substances. The oceans have hit their hottest ever recorded temperature as they soak up warmth from climate change, with dire implications for our planet's health. The average daily global sea surface temperature beat a 2016 record this week, according to the EU's climate change service Copernicus. "March should be when the oceans globally are warmest, not August or September. The fact that we've seen the record now makes me nervous about how much warmer the ocean may get between now and next March," says Dr Samantha Burgess from the Copernicus Climate Change Service. Niger's newly installed junta has threatened an immediate response to any "aggression or attempted aggression", as the clock ticks down on a deadline given by its neighbours to reverse last week's coup. It also made diplomatic swipes against international condemnation of the putsch, scrapping military pacts with France and pulling its ambassadors from Paris and Washington as well as from Togo and Nigeria. A husband and wife cyber-crime team have pleaded guilty to trying to launder $4.5bn (£3.5bn) of Bitcoin that he had stolen in a hack in 2016. Heather Morgan and Ilya Lichtenstein were arrested last year in New York after police traced their riches back to the crypto heist. At least 18 people died in western Mexico when a passenger bus plunged off a highway into a ravine early on Thursday, state officials said, adding the passengers were mostly foreigners and some were heading for the U.S. border. The New Zealand government on Friday presented its first national security strategy, along with the first stage of a defence review. The review outlined how New Zealand needs to spend more on its military and strengthen ties with countries in the Indo-Pacific to help meet the challenges of climate change and strategic competition between the West, and China and Russia. The government of Alberta has pulled its support for a bid to host the 2030 Commonwealth Games due to rising costs. @0406z Newsday begins. 250ft unterminated BoG antenna pointed E/W w/MFJ-1020C active antenna (used as a preamplifier/preselector), Etón e1XM. 250kW, beamAz 315°, bearing 63°. Received at Plymouth, United States, 15359KM from transmitter at Talata Volonondry. Local time: 2257.

0 notes

Text

ltdan2288 asked: As a fellow veteran of the Afghan Campaign, might I ask if you have any thoughts about the imminent end of Allied air support & combat-advisory operations over there? The fall of large swaths of the country to the Taliban is already underway, which can only be seen as an unspeakable tragedy for the people there. From a strategic perspective, there’s no reason to believe that we won’t have to return in some capacity of AQ or ISIS reestablish themselves under Taliban sponsorship. At the same time, it’s not clear to me that our presence did anything beyond kick the can down the road and delay this inevitable outcome. As someone with such a deep knowledge of military history, I’m curious if you have a different perspective.

I have been avoiding answering this post for a while now because Afghanistan dredges up so many conflicting emotions inside me. I wrestle with so many memories of my time there with my regiment to fight in a war that we all didn’t really understand what we were fighting for.

Deep breath.

Almost two decades of conflict in Afghanistan has cost British taxpayers £22.2billion, or $31.3 billion according to UK government figures. As British troops prepare to leave Afghanistan, the 20-year deployment bill could be even higher. As of May 2021, the total cost of Operation Herrick (codename for the deployment of British soldiers to Helmand province) is £22.2billion. There were 457 fatalities on, or subsequently due to, Op Herrick. Of which 403 were due to hostile action. During the operation between January 1, 2006 and November 30, 2014, there were 10,382 British service personnel casualties. Of these 5,705 were injuries and the remainder being illness or disease. The UK’s remaining 750 troops in Afghanistan, involved in training local forces, started exiting the war-devastated country in May. Most of them will return home by the end of July.

They, like every one of us who went to fight in Afghanistan, will ask the same questions, ‘Why did we go there?’ ‘What was the real purpose of the mission?’ ‘Was it worth it?’

Both my older brothers fought there with special distinction and I later fought there too. I have very mixed emotions when I think about my time in Afghanistan. For all its faults and tortured history, I love that country and love its many ethnic people. I even started to learn Pashtu as I already had a spoken command of Urdu because I had been raised partly in both Pakistan and India and it’s where many Afghan refugees living in the UN camps for over a generation had learned Urdu too.

It’s not just that my family has history in Afghanistan going back to the days of the East India Company but I had a sincere respect for its culture and history as one of the central hot spots for great civilisational achievements, but also as a stubborn and unruly country who proudly defied the Great Powers to bend the knee and turned it into a ‘graveyard of empires’. Most of all I think of the friendships I made there and how my perspective on life changed as a consequence of knowing such resilience and fortitude in the face of catastrophe and death.

I’m sure like everyone else I wasn’t too surprised by President Biden’s announcement that he was announcing the imminent withdrawal of all American troops in Afghanistan. He wanted to pivot to something else when asked about it. “I want to talk about happy things, man!” He said. Who could begrudge him given that America has been at war in Afghanistan for a better part of 20 years and has nothing to really show for it. Except of course the loss of its brave service men and women as well as the death of thousands of Afghan civilians. It spent more than $2 trillion to kill Osama bin Laden, the architect behind 9/11 attacks and failed to convincingly snuff out both murderous terror groups, Al Qaeda and ISIS.

When the Secretary General of Nato announced back in April 2021 all alliance troops were to be withdrawn from Afghanistan, it was made to look like a nice, clean, enunciation of a joint decision. The end date was set for 11 September, 2021 - 20 years after the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington - and it was in line with the oft-repeated alliance maxim: we went in together; we will come out together. Except that, on closer examination, it was all rather messier.

This was partly because the withdrawal from Afghanistan had actually been Trump’s policy, so here was Joe Biden, the anti-Trump, co-opting a policy from his predecessor (a policy Trump had been so keen on that he tried to accelerate the withdrawal after he lost the election). Biden then tried to detach it from Trump by slowing down the withdrawal date a little and expressing it in terms more comprehensible to the Washington establishment and to US allies.

Where Trump had essentially done a deal with the Taliban and set a withdrawal date of 1 May, Biden left the Taliban out of it and invoked the totemic date of 9/11. This does not mean, of course, that the withdrawal will not be completed a good deal sooner - once you announce a withdrawal, you might as well get on with it.

In fact, Biden had to make a decision one way or another, given the rapid approach of Trump’s 1 May withdrawal date. And, whether it came from Washington or Nato, it was pretty low key for an announcement that a 20-year military involvement that had cost 4,000 allied lives was ending. Indeed, many people beyond Washington and Afghanistan might not quite have registered the news, given the considerable noises from Nato’s simultaneous dire warnings about Russia massing troops on the Ukrainian border, the death of the Duke of Edinburgh in the UK, and the Covid pandemic everywhere.

And distractions were needed not just because Biden was implementing a Trump policy. It was also because he was ordering an unconditional withdrawal – which he justified, correctly, by saying that setting preconditions would mean that the troops could be there forever. It was a risk Biden knew all too well, given that Barack Obama had been persuaded by General David Petraeus – against his election pledges and his better judgement – that what Obama really wanted was not a withdrawal, but a ‘surge’ with conditions attached before a withdrawal could take place.

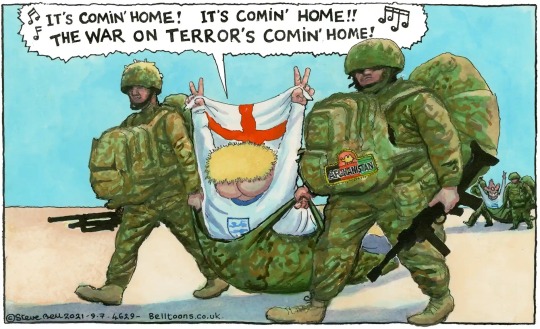

Distractions were also useful for London, where the timing was hardly ideal. Imagine you were in government in London, you had watched the dismal failure of the UK’s Herrick operations in Helmand Province between 2006 and 2014, you knew that your armed forces had suffered 456 deaths in 20 years, with many more severely injured, but you had hung on in there.

Your government had also just released a blueprint for foreign and security policy, setting future priorities even further from home, in the Indo-Pacific, and your Prime Minister was about to make a high-profile visit to India as part of his post-Brexit ‘Global Britain’ branding . In those circumstances, an announcement that the US had decided to leave Afghanistan, giving you no choice but to follow, was almost exactly what you did not need. Rather than showing the UK as a powerful, autonomous military actor and a valued ally, it showed the exact opposite.

It also reminded an unhappy British public about a costly conflict it had rather forgotten. And those who did more than bother to remember - like the families who lost loved ones on the battlefield - and who over the years have blamed successive governments for moving the goalposts and lacking an exit strategy (all true too).

All of which might explain why the UK’s Foreign and Defence Secretaries followed the US example by changing the subject to the iniquities of Russia and China, rather than issuing a joyous pronouncement to the effect of: hooray and thank goodness, our boys and girls are coming home.

The UK’s Chief of Defence Staff, General Sir Nick Carter gave a subdued, unenthusiastic response to Biden’s announcement. I cannot remember such open acknowledgement of UK-US military policy friction in recent decades - or such an abject admission by the UK of its defence dependence on the US. What Carter said was that the unconditional withdrawal was ‘not a decision we had hoped for, but we obviously respect it and it is clearly an acknowledgement of an evolving US strategic posture’. In other words, the UK had opposed Biden’s decision – or would have done, if asked (which is not clear). Also, that it was Washington’s ‘strategic posture’ that had ‘evolved’, not the UK’s. He suggested there was a real danger that progress made could be lost and that there could be a return to civil war, with the Taliban maybe returning to power - again, all true.

Given that the UK officially has only 750 troops in Afghanistan at present, and most of them are there in a training capacity, to dissent from the US position so openly would be considered decidedly rude in the Ministry of Defence. Perhaps to that end, General Carter played the dutiful soldier and had to - through gritted teeth - put a positive gloss on Afghanistan’s future, insisting that the objective in going into Afghanistan, ‘to prevent international terrorism emerging from the country’, had been achieved which was ‘great tribute to the work of British forces and their allies’.

He also said that Afghan forces were ‘much better trained than one might imagine’ and that the Taliban ‘is not the organisation it once was’, so that ‘a scenario could play out that is actually not quite as bad as perhaps some of the naysayers are predicting.’ Blah blah blah. He’s wrong, and I think he knows it but only in the sanctity of his gentlemen’s club might he truly admit it.

I know he’s wrong because the chatter amongst ex-veterans I know is that we’ve made a balls up of Afghanistan yet again - by ‘again’ I mean from the past 200 years of us Brits trying to bring order to chaos in Afghanistan and getting burned for our troubles.

Both my father and my older siblings tell me what their friends and ex-service peers (some very senior indeed) have been nattering over a drink at their gentlemen clubs where ex-veterans haunt the club bar. Many just shake their heads in sighed resignation before burying themselves in the Times crossword or drowning their sorrows with a beer or two at how lock in step we’ve become to the Americans at a time when the British army is re-branding itself as a more independent nimble hi-tech impact army (the creation of a new ranger regiment being but one example).

Still if President Biden wanted to tie a neat bow on U.S. involvement in Afghanistan - saying, as he had, that the logic for the war ended once al-Qaida was gutted and Osama bin Laden killed - then it reveals a stunning lack of introspection about the United States’ role in the conflict that will continue in Afghanistan long after the last American and British troops leave.

Less than three months after President Joe Biden declared that the last American troops would be out of Afghanistan by September 11th, the withdrawal is nearly complete. The departure from Bagram air base, an hour’s drive north of the capital, Kabul, in effect marked the end of America’s 20-year war. But that does not mean the end of the war in Afghanistan. If anything, it is only going to get worse.

It is true that the president had no good choice on Afghanistan, and that he inherited a bad deal from his predecessor. There are never good choices when it comes to Afghanistan: only bloody trade offs.

But in announcing an unconditional withdrawal, he made the situation worse by throwing out the minimal conditions U.S. Special Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad had negotiated under the Trump administration. U.S. envoy Zalmay Khalilzad has delivered to the Afghan government and Taliban a draft Afghanistan Peace Agreement - the central idea of which is replacing the elected Afghan government with a so-called transitional one that would include the Taliban and then negotiate among its members the future permanent system of government. Crucial blank spaces in the draft include the exact share of power for each of the warring sides and which side would control security institutions.

The refrain now from the Biden administration is that the United States is not abandoning Afghanistan, that it will aim to do right by Afghan women and girls, and that it will try to nudge the Taliban and Kabul toward a peace deal using a diplomatic tool kit.

But the narrative ignores much of the reality on the ground. It also ignores history.

In theory, the Taliban and the American-backed government had been negotiating a peace accord, whereby the insurgents lay down their arms and participate instead in a redesigned political system. In the best-case scenario, strong American support for the government, both financial and military (in the form of continuing air strikes on the Taliban), coupled with immense pressure on the insurgents’ friends, such as Pakistan, might succeed in producing some form of power-sharing agreement.

But even if that were to happen - and the chances are low - it would be a depressing spectacle. The Taliban would insist on moving backwards in the direction of the brutal theocracy they imposed during their previous stint in power, when they confined women to their homes, stopped girls from going to school and meted out harsh punishments for sins such as wearing the wrong clothes or listening to the wrong music.

More likely than any deal, however, is that the Taliban try to use their victories on the battlefield to topple the government by force. They have already overrun much of the countryside, with government units mostly restricted to cities and towns. Demoralised government troops are abandoning their posts. In the first week of July 2021, over 1,000 of them fled from the north-eastern province of Badakhshan to neighbouring Tajikistan. The Taliban have not yet managed to capture and hold any cities, and may lack the manpower to do so in lots of places at once. They may prefer to throttle the government slowly rather than attack it head on. But the momentum is clearly on their side.

America and its NATO allies have spent billions of dollars training and equipping Afghan security forces in the hope that they would one day be able to stand alone. Instead, they started buckling even before America left. Many districts are being taken not by force, but are simply handed over. Soldiers and policemen have surrendered in droves, leaving piles of American-purchased arms and ammunition and fleets of vehicles. Even as the last American troops were leaving Bagram over the weekend of July 3rd, more than 1,000 Afghan soldiers were busy fleeing across the border into neighbouring Tajikistan as they sought to escape a Taliban assault.

As the outlook for the army and for civilians looks increasingly desperate, so do the measures proposed by the government. Ashraf Ghani, the president, is trying to mobilise militias to shore up the flimsy army. He has turned for help to figures such as Atta Mohammad Noor, who rose to power as an anti-Soviet and anti-Taliban commander and is now a potentate and businessman in Balkh province. “No matter what, we will defend our cities and the dignity of our people,” said Mr Noor in his gilded reception hall in Mazar-i-Sharif, the key to holding the north (sounds like Game of Thrones). The thinking is that such a mobilisation would be a temporary measure to give the army breathing space and allow it to regroup and the new forces would co-ordinate with government troops to push back hard on the Taliban.

However this is Afghanistan. The prospect of unleashing warlords’ private armies fills many Afghans with dread, reminding them of the anarchy of the 1990s. Such militias, raised along ethnic lines, tended to turn on each other and the general population.

With America gone and Afghan forces melting away, the Taliban fancy their prospects. They show little sign of engaging in serious negotiations with Mr Ghani’s administration. Yet they control no major towns or cities. Sewing up the countryside puts pressure on the urban centres, but the Taliban may be in no hurry to force the issue. They generally lack heavy weapons. They may also lack the numbers to take a city against sustained resistance. On July 7th they failed to capture Qala-e-Naw, a small town. Besides, controlling a city would bring fresh headaches. They are not good at providing government services.

Perhaps the Taliban have learned their history lesson and might refrain from attacking Kabul this time around. Their best course may be to tighten the screws and wait for the government to buckle. American predictions of its fate are getting gloomier. Intelligence agencies think Mr Ghani’s government could collapse within six months, according to the Wall Street Journal. So clearly the momentum is on the side of the Taliban and they just need to chip away at Ghani’s forces one district after another until the inevitable and hateful surrender of the central Afghan government to their demands.

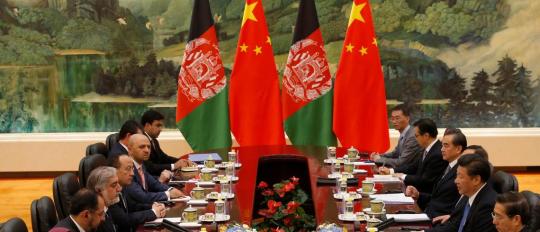

At the very least, the civil war is likely to intensify, as the Taliban press their advantage and the government fights for its life. Other countries - China, India, Iran, Russia and Pakistan - will seek to fill the vacuum left by America. Some will funnel money and weapons to friendly warlords. The result will be yet more bloodshed and destruction, in a country that has suffered constant warfare for more than 40 years. Those who worry about possible reprisals against the locals who worked as translators for the Americans are missing the big picture: America, Britain and other allies are abandoning an entire country of almost 40m people to a grisly fate.

Nothing exemplifies - at least in Afghan eyes - of all that has gone wrong with American involvement in Afghanistan than in the manner of their leaving.

The U.S. left Afghanistan's Bagram Airfield after nearly 20 years by shutting off the electricity and slipping away in the night without notifying the base's new Afghan commander, who discovered the Americans' departure more than two hours after they left in the middle of the night without raising any alarms.

They left behind 3.5 million items, including tens of thousands of bottles of water, energy drinks and military MRE's (Meals Ready to Eat ration packs to the uninitiated). Thousands of civilian vehicles were left, many without keys to start them, and hundreds of armoured vehicles. The Americans also left small weapons and ammunition, but the departing US troops took heavy weapons with them. Ammunition for weapons not left for the Afghan military was blown up.

Now that is some feat considering the logistics of this mass exodus without drawing any attention. You have obviously been to Bagram and so you will know just how big and sprawling it is. Bagram Airfield is the size of a small city, roadways weaving through barracks and past hangar-like buildings. There are two runways and more than 100 parking spots for fighter jets known as revetments. One of the two runways is 12,000 feet long and was built in 2006. There's a passenger lounge, a 50-bed hospital and giant hangar-size tents filled with furniture. And all those shops to remind Americans of home from familiar fast food restaurants and hairdressers and massage parlours to buying clothing and jewellery and buying a Harley Davidson motorbike (or so I’ve been told).

I’m guessing that the Afghans were certainly outside of the wire and probably had not been inside Bagram Airfield for months. So from the outset they would not have had any reason to think anything was going on until the generators probably ran out of fuel and it started to go a little too quiet. The inner gate was probably discretely left unlocked and when the US stopped answering the radio/phone and then they probably investigated.

Before the Afghan army could take control of the airfield about an hour's drive from the Afghan capital, Kabul, it was invaded by a small army of looters, who ransacked barrack after barrack and rummaged through giant storage tents before being evicted, according to Afghan troops. Afghan military leaders insist the Afghan National Security and Defense Force could hold on to the heavily fortified base despite a string of Taliban wins on the battlefield. The airfield includes a prison with about 5,000 prisoners, many of them allegedly Taliban members.

I’m pretty sure some bright spark in the US Pentagon public affairs dept convinced his military superiors that it was important to avoid the optics of Americans leaving in the same way they did in Vietnam in case it depresses the American public and the US military. Instead it demoralised its allies, the Afghan national army who are now the only line of defence against the Taliban. In one night, they lost all the goodwill of 20 years by leaving the way they did, in the night, without telling the Afghan soldiers who were outside patrolling the area. The manner in which the Americans left Bagram air base amounts to a resounding vote of no confidence in Afghanistan’s future. It just looks bad.

The U.S. choice came with costs attached to each decision. With staying, the cost was potential U.S. troop casualties and a fear that things would not change on the ground. With leaving comes the cost of a deeper conflict in Afghanistan and a backsliding of progress made there over the past two decades. In many ways, the costs of staying seem shorter-term and borne by the United States, while the costs of leaving will be predominantly borne by Afghans over a longer time horizon. Yet, even if those costs seem remote now, history tells us that they will be blamed on the United States.

Biden perhaps reflective of history of Americans getting into quagmires abroad didn’t want to be seen exerting time and energy for a losing cause. His decision also reflects his administration’s foreign policy for the American middle-class paradigm, which focuses on domestic considerations over international ones (and is this so different from Trump’s “America First”? No, it is not). The irony, though, is that the American middle class largely doesn’t care about Afghanistan - their ambivalence gave way to support for this decision once it was announced, but it wouldn’t be hard to visualise the public approving of a scenario that kept a couple thousand troops there for a while longer.

What’s perhaps most disturbing is the narrative the president has presented along with the rationale for withdrawal: that America went to Afghanistan to defeat al-Qaida after 9/11, that mission creep led America to stay on too long and, therefore, it is time to get out. This takes an incomplete view of U.S. agency in the war in Afghanistan. The narrative implies that the civil conflict in Afghanistan today did not originate with America - that this more than 40-year war began with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, preceded America’s interference in Afghanistan, and will follow our departure.

The fact of the matter is that, by beginning the campaign in Afghanistan in 2001 and overthrowing the Taliban, who were then engaged in their draconian rule, and installing a new government, we western allies began a new phase of the Afghan conflict — one that pitted the Kabul government and the United States/Britain/NATO against the Taliban insurgency. The Afghan people did not have a say in the matter. That we allied powers are leaving Afghan women, children, and youth better off in many ways after 20 years is due to us, and we should be proud of that. But that we are leaving them mired in a bloody conflict is also due to us, because we could not hold off the Taliban insurgency, and we must all reckon publicly with that.

I have to ask myself why did we fail?

I’m only speaking about us Brits now as I’m sure you have your own thoughts as an ex-Marine officer of what you thought of the American military effort. Yes, I’m copping out of really bashing the yanks because first, I have too much respect for those fantastic American service men and women I did have the privilege to fight alongside with; and second, we Brits have nothing to crow about as we fucked up in lots of ways too, and to make things worse, we should have known better given our imperial history with Afghanistan.

The seeds of our failure in Afghanistan lies in not learning from history. We didn’t have a mission that was properly defined nor did we have a strategy that was clear, coherent, and easily communicated to both its fighting men and women as well as to the British public.

Were we there to get our hands bloody and to root out and destroy extreme Islamist terrorists or were we there to indulge in state building out of some idealistic notions of liberal humanitarianism? This question was at heart of our failure within our government and also within the British army as well as our relations with America and our NATO allies and finally the Afghans themselves.

Although never colonised in the same manner as other central and south Asian countries, the modern Afghan state is very much a creation borne out of great power rivalry. A land occupied by a number of different ethnic, linguistic and religious groups, it is a country whose borders were defined by, and whose sense of national identity was forged in response to western great power competition. Its geopolitical position - landlocked, mountainous, and surrounded by past great powers and present regional rivals - lends Afghanistan a dual role of geographic obscurity and great strategic significance, and has as such frequently been treated as little more than a buffer state between empires and a proxy of local powers. Its shared historical border with Russia and British India made it an object of imperial intrigue and, by consequence, has been subject to five European military interventions in the last 175 years.

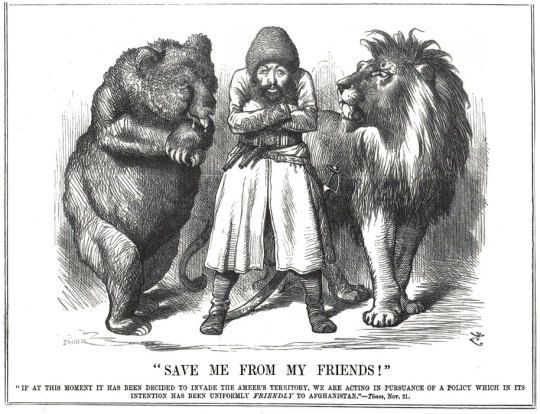

The first three interventions of these occurred during the era of ‘the Great Game’ in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in which Britain and Russia (latterly the Soviet Union) competed for influence and control over Afghan politics in order to protect their respective imperial holdings in India and central Asia.

The fourth and fifth interventions, ranging from the late 1970s to the present day, similarly involved attempts by Soviets and then by an American-led international coalition to remove political leaders acting against their interests and to protect their favoured candidates.

The unifying feature of all these conflicts was the idea of Afghanistan as the site of potential threats to the interests and security of more powerful states.

Britain’s legacy in Afghanistan in particular set the tone for the country’s historical pattern of conflict and political contestation, fuelling both the intermittent emergence of Afghan national consciousness and a fractious political lineage that saw thirteen amirs in just eighty years. Interventions by the Empire during the Great Game set the conditions for the assassination of ostensibly national leaders by their compatriots (Shah Shuja Durrani in the First war) or their exile by the British (Shere Ali Khan and Ayub Khan in the Second).

Despite the British achieving their aim of protecting India in the second and third conflicts by maintaining Afghanistan as either a pro-British buffer state or as a neutral party, the Afghan narrative tends to emphasise successes such as the massacre of British forces retreating from Kabul to Jalalabad in 1842, the defeat of British and Indian forces at Maiwand in 1880, and the gaining of sovereignty in foreign affairs in 1919.

Soviet intervention in the late 1970s and 1980s further buttressed this identity of resistance, and the failure and ultimate overthrow of the Communist-backed Najibullah government, as well as the collapse of the Soviet Union shortly after their drawdown from Afghanistan, led to a sense amongst the victorious mujahidin of the country as the ‘graveyard of empires’.

Afghanistan’s modern history should thus be seen as inextricably linked to the ebbs and flows of great power politics. Each intervention exacerbated extant internal power struggles between rival elite individuals and groups vying for nominal control over the country. Foreign intervention in Afghanistan was met on each occasion with fierce resistance from tribal militias coalesced around religion; as has been remarked upon by one historian of the country, the threat of external domination has been one of the few means of uniting its disparate population around the concept of an Afghan ‘nation’, and in most cases this shared sense of identity cohered around religion, not nationalism.

Indeed, the presence of intervening powers and the development of the Afghan state may be seen as mutually supporting: whilst most Afghan leaders throughout the last two centuries have asserted their sovereignty over the country, the reality has in most circumstances been one of competing tribal chiefs and/or ‘warlords’ rather than a single dominant leader.

Where leaders have managed to cohere the disparate tribal and ethnic groupings of the country under one banner - most notably under the regime of Dost Mohamed Khan (1826-1839, 1845-1863) – this was due in large part to their diplomatic abilities of compromise and co-optation with Afghanistan’s regional power- brokers. In other cases, such as that of the reign of Abdurrahman (1880- 1901), power was maintained by an unflinching ‘internal imperialism’ and the use of punitive force against rebellious factions.

The challenges of maintaining and projecting centralised power in Afghanistan allow us to see the relationship of its leaders with world or regional powers in the last two centuries as one of mutual exploitation. Throughout the Great Game and the Cold War, whilst the British/Americans and Russians/Soviets would use threats and bribes (and occasionally force) to compel Afghan rulers to comply with their geopolitical needs, Afghan rulers themselves often deftly manipulated those powers to maintain and extend their own power.

The pattern followed by Afghan leaders from the nineteenth century to the present day is remarkably similar in the respect that most have relied upon a rentierist economic model, seeking external aid in order to sustain the cost of security and administration. The plan of modern rulers was to warm Afghanistan with the heat generated by the great power conflicts without getting drawn into them directly. Abdurrahman, for example, used British subsidies to fund his military campaigns against rebellious factions; the Musahiban rulers of the mid-twentieth century used American capital to develop its nascent economic infrastructure and Soviet finance to bolster its armed forces; and, following the overthrow of the last royal leader of Afghanistan, Mohamed Daoud, in 1978, the quasi-communist leadership of Babrak Karmal, Hafizullah Amin, Nur Muhammad Taraki, and Mohammad Najibullah during the late 1970s and 1980s relied in the main on Soviet money and military assistance in its ultimately failed attempt to implement socialist policies and put down the American, Saudi and Pakistani-backed mujahidin.

These trends continued into the post-Cold War period in respect to both the Taliban movement (essentially directed and funded by Pakistan), the Northern Alliance (funded largely by former Soviet central Asian states) and the regime of Hamid Karzai (maintained in economic and military terms by the American-led, NATO-operated International Security Assistance Force and the wider international community). In the former cases, occurring in the main in the period of civil war between 1992 and 2001, rentierism was limited to the maintenance of proxy parties and the continuation of conflict.

By contrast, the ISAF mission bore similarities with the Soviet-backed socialist regimes of the 1980s, insofar as it focused huge amounts of capital and military resources on stabilisation and state-building efforts. Both intervening parties made the error of ignoring Afghanistan’s political history and focused their efforts on bolstering the authority of a centralised state, both promoted policies that were deemed ‘universal’ in their application and were, unsurprisingly given such hubris, vulnerable to accusations by Afghan opposition to being alien and imperialistic ideologies, and both expended enormous amounts of blood and treasure in order to sustain the regimes they supported.

The UK’s struggle to locate a coherent strategy for Afghanistan should, therefore, be seen firstly in the light of the historical problematic of Afghan state-building. This is important in narrative terms because difficulties of defining strategy imply similar challenges in explaining strategy. As with its efforts to ‘think’ strategically, Britain’s ability to explain the strategy(ies) for the war in Afghanistan have been frequently criticised by various commentators. The most strategically debilitating aspect of the Afghan campaign has always been the incoherence of the mission’s purpose; indeed the question ‘‘why are we in Afghanistan?’’ has never really been settled in public consciousness. The international community massively underestimated the difficulties of state-building and greatly overstretched themselves in the commitments made to Afghanistan, and that they did so because ‘strategies’ for Afghanistan rested on assumptions of the universal applicability of liberal state-building.

The international community from the start (meaning from the Bonn Conference of late 2001) fundamentally misunderstood the nature of an Afghan society deeply ravaged by decades of conflict, and failed to foresee the malign effects state-building ventures would have on the country. Specifically, the Bonn Conference, which set out the parameters of the post-invasion Afghan state, implemented a centralised state system onto a state whose experience of such was limited, and where the success of such a system in extending its authority beyond the major cities was predicated on coercion and the use of force.

Historically this has rarely been a credible option for Afghan rulers or their international backers, and was even less so under the self-imposed restrictions of liberal war-fighting and state-building. Rather, re-creating a centralised state required Afghan and international actors to enter into the same methods of co-optation and compromise as those of the past; in necessitating these kind of measures – as opposed to implementing a looser, federal system of governance – the centralisation of the Afghan state paved the way for a reconstitution of a ruling order based on tribal elements and ‘strongmen’. This produced something of a paradox for state-builders, as the creation of a strong, central state capable of implementing liberal policies across Afghanistan came at the cost of entering into alliances with ‘warlords’ known for their illiberal and coercive political approaches and illicit economic activities.

Another unintended but unavoidable consequence of centralised state-building identified by scholars is the re-constitution of the rentier state in Afghanistan. Post-Bonn, Afghanistan returned to its historical norm of maintaining the state via the extraction of external security and development rents, without which it would almost certainly implode due to the ruinous state of its economy and taxation system. Studies have shown that his new rentierism differed from previous patronage systems at the state level insofar as it was fuelled by an unprecedented influx of capital and resources into the country. This had the effect of introducing regulated systems of ‘neo-patrimonalism’, where departments were to be distributed as rewards to the various factions that took part in the Bonn conference, and there had to be enough rewards to go around.

In other words, the structure of the post-invasion Afghan state was, to a great extent, defined not by the demands of good governance, the needs of the country or the demands of post-conflict stabilisation and reconstruction – the purposes for which the centralised model was chosen to promote – but rather by the first-order need to avoid the derailment of the centralised state by co-opting regional power brokers.

Because of the imperative of shoring up a nascent state by securing support from potential competitors, the gulf between the ends of liberal state-building and the illiberal means required to facilitate its functioning can therefore be seen to a certain extent as inevitable.

A major issue, however, was that the patrimonial linkages created by the state for its regional proxies was not comprehensive, as it did not extend to the Taliban’s Pashtun heartland and, as such, fuelled resentment and alienation as much as they placated and co- opted extra-state power brokers. Key players in the Northern Alliance - the primarily Tajik opposition to the Taliban - received prestigious posts within the state, whilst the predominantly Pashtun Taliban were themselves excluded from such arrangements. Because those rewarded by the state tended to be given ministerial or governorial roles in cities, the conflict dynamic tended to reflect an urban – rural divide similar to that of the Soviet occupation. Along this reading, the neo-Taliban insurgency was in many ways a product of the political miscalculations and deficiencies of post-invasion state- building activities.

Given this starting point, such a view concludes that the strategic problems encountered by the international community in Afghanistan were, to a large degree, problems created by (or at the very least exacerbated by) the state-builders themselves. They misread Afghan politics in a way that reflected their own philosophical assumptions about the state and society.

Strategy in Afghanistan suffered because the coalition effort, comprised of multiple national actors and the United Nations, rarely took on the form of a unified effort. Part of the reason for this was a divergence of opinion between actors as to the ultimate purpose – counter-terrorism or state-building – of the intervention.

In the first years of the Afghan campaign, the United States’ Bush Administration remained staunchly opposed to what it called ‘nation building’ and opted instead to pursue a policy of capture- or-kill missions against suspected terrorists. For the United Nations and most of the United States’ European NATO allies, however, state-building was considered a necessary element of any counter-terrorist strategy. This difference of opinion was manifest from the start by the creation of two parallel missions – the US-led, counter-terrorism-focused Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and the stabilisation missions of the European Union, United Nations (United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA)) and NATO (International Security Assistance Force (ISAF)) – engaged in seemingly incompatible aims of military prosecution and peace building.

Opinion on the impact of this dual approach varies. Some scholars have noted, along lines similar to those critiquing the state-building efforts of the international community that the approach taken by the UN, EU and ISAF was too ambitious, naïve and unrealistic, and therefore bound to fall short of their liberal political and economic goals. Both Europe and these international agencies ignored the necessity of paring down the international community’s state-building efforts to core, security-centric capacity building within the Afghan National Security Forces. But of course one can make the counter argument, as many have of course, that on the contrary it was the insufficiencies of state-building approaches vis-à-vis OEF’s counter-terrorist approach that led to subsequent failures in UN and ISAF efforts; specifically, that a disproportionate focus on counter-terrorism missions meant that opportunities of peace- building were irreparably compromised.

Within NATO there was a division not just of opinions but also one of mission relating to different political perspectives about the purpose of the Afghan mission and its ultimate referent object – whether it was primarily about the interests of the coalition member states or concerned in the main with Afghanistan itself – and, from that, the methods to be employed in pursuit of one or another objective. This was not merely a debate bounded by strategic necessity, however; rather, such debates stemmed as much from institutional disagreements over who would or could do what in Afghanistan, which in turn arose from the differences in political constitutions and cultural attitudes towards counterinsurgency and counter- terrorism.

These ‘national caveats’ or ‘red cards’ of participation created significant problems for NATO in Afghanistan, both political, in terms of the relations between states and the abiding sense amongst some that others were ‘free-riding’ on the collective security system and, and strategic and operational, in the sense that command-and-control capabilities and cohesion between forces were limited by the engagement restrictions placed on certain armed forces. Indeed, the disproportionate burden placed on combat-oriented states like the United States, the United Kingdom, and several new member states in Eastern Europe led to political statements denouncing Europe’s perceived transgressors of collective security participation; former US Defence Secretary Robert Gates argued, for example, that NATO had effectively become a ‘two-tier alliance’ ‘between members who specialise in ‘soft’ humanitarian, development, peacekeeping and talking tasks and those conducting the ‘hard’ combat missions - between those willing and able to pay the price and bear the burdens of alliance commitments, and those who enjoy the benefits of NATO membership... but don’t want to share the risks and the costs’.