#Trevor's comm sheet

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

How much do you charge for commissions?

I charge $15 per hour!

I do digital art, fanart, book covers (yes, fanfic covers included), graphic design, logos, business cards, acrylic paint, watercolor paint, washi tape art, Minecraft skins, custom stickers, etc.

I accept PayPal, Venmo, CashApp, Zelle, and I'm working on a Stripe account.

"How many hours does it take to complete a comm?"

That depends on the nature of the comm. Here are some of mine from this year:

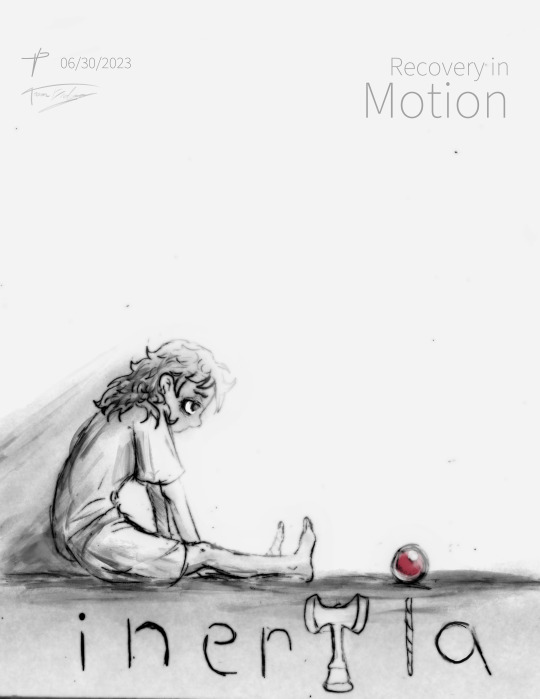

1 HOUR ($15) - These were commissioned by CrustySoap. These drawings took roughly an hour each. Generally speaking, scanned sketches and scanned sketches with flat colors are my quickest styles. If you're on a budget, this may be the style for you.

2. 2.48 HOURS ($37.20) - This one was commissioned by Ian. She wanted a self portrait based on one of her outfits. The background is made of a recycled filter made in one of my previous drawings.

3. Roughly 8.46 HOURS ($127~) - Commissioned by my good friend Nicole Straussman-Allen for her husband's bday. She approached me with the prompt of having Link from TTOK and Solid Snake from Metal Gear Solid shaking prosthetic hands. Since they have the hands on the same side, I suggested a fist bump instead, to which she heartily agreed. The result is something I'm very proud of.

However, these are not all the art styles I can do.

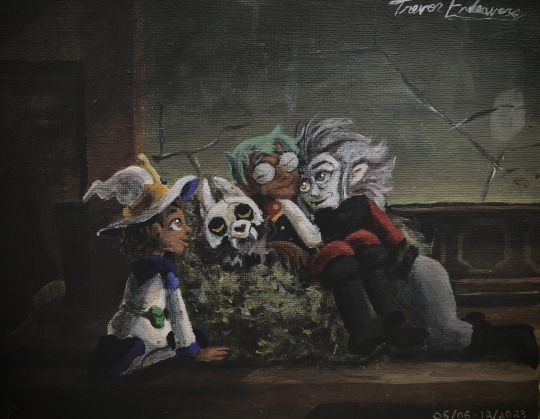

I was also commissioned by none other than Avi Roque this year! Their prompt was to create a physical painting/sketch of a scene from The Owl House. Disclaimer: I collected $50 + shipping for this painting - the prices listed on my website are approximately such, but as of this year they are currently out of date.

As with anything I make, $15/hour is the charge.

Here are other examples of my art!

Here's how I operate commissions:

Think of a character(s) you want me to draw and in what style. This can be a style I've already drawn in or one you'd like me to emulate. If you're not sure, I can give you recommendations based on your budget and aesthetic preferences. I can draw backgrounds as well, or even use a photo (either yours or mine) as a background.

From there, I'll give you a time estimate on how long it'll take. This varies greatly depending on the chosen art style and complexity of the comm.

Once we agree on the estimated price and style, that is when I begin timing myself as I work on your comm. I count strictly the hours I am working on the comm - not days between drawing sessions.

I'll send you work in progress photos/screenshots throughout. If you see something you'd like changed, it's better to let me know sooner rather than later so I can reduce the time needed to make adjustments.

Once you're satisfied with the final result, that's when payment is due. I take PayPal, Venmo, CashApp, and Zelle. I'm working on adding Stripe as well.

It is then that I'll email you the final result in high resolution and your preferred file format. NOTE: I also do painting commissions. If you would like a physical painting shipped to you, you will be responsible for shipping charges (thankfully my post office is relatively cheap, so depending on the size you're looking at an additional fee of $5-10, if that).

WILL DO / WON'T DO:

I will draw pretty much anything except for deliberately fetishistic art. For anything nsfw, I require proof of age. I reserve the right to terminate a comm for any reason.

That said, I look forward to working with you!

#trevorendeavorsart#Trevor's comm sheet#about time I made one of these actually#lumity#the owl house#Steven universe#jasper su#su jasper#huntlow#Trevor-brand huntlow#emerald trio#pride art#the owl house fanart#luz noceda#hexsquad#gus porter#willow park#hunter toh#toh hunter#hunter noceda#commissions open#comms open#graphic design#acrylic painting#digital artwork#deltarune noelle#Noelle holiday#Camila noceda#Minecraft skin commissions#minecraft

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

OLIVER JONES, SUR LES TRACES D’OSCAR PETERSON

“There was a lot of hullabaloo surrounding Charlie and myself. Anything pertaining to jazz, we were asked to do. I’d made my first recording. Truthfully, I was in a state of shock, because when you dream something for 30 years…”

- Oliver Jones

Né le 11 septembre 1934 dans le quartier ouvrier de la Petite-Bourgogne à Montréal, Oliver Theophilus Jones est le fils de parents originaires de la Barbade. Le père de Jones était mécanicien dans l’industrie des chemins de fer, et avait travaillé pour la Canadian Pacific Railways durant trente-sept ans. Au début, le père de Jones avait voulu que son fils devienne comptable, mais il n’avait vraiment aucune aptitude pour les mathématiques. Jones expliquait: ‘’For some reason, my dad wanted me to be an accountant. However, I was so poor at math that my parents had to hire a tutor for me. So my future as an accountant didn’t look very bright.’’

Jones avait commencé à apprendre le piano classique à l’âge de cinq ans. Le père de Jones était d’ailleurs un grand amateur du répertoire religieux de Jean-Sébastien Bach. Même si le père de Jones avait échoué dans sa tentative de faire de son fils un comptable, il était très fier de sa réussite comme pianiste. Jones précisait: ‘’My father liked to take credit for my musical ability, although it was my mother and her two sisters who travelled around the Carribean, performing as singers with their father. My grandfather was also a high school principal and a minister.’’

Même si Jones n’avait peut-être pas choisi un métier très lucratif, cela n’avait pas empêché son père de lui avoir inculqué une solide éthique de travail. Jones poursuivait: ‘’When I quit high school, my father insisted that I work during the week - even though I was playing music on the week-ends. I’d made $16 - $17 for five days’ work during the week in a dress factory, and then go {to} make 100$ playing in a club on the weekend. When I first started playing in the clubs - the first person I saw in the audience was my father.’’

Jones avait d’abord étudié le piano avec une certaine Mme Bonner de la Union United Church, une église rendue célèbre par la Montreal Jubilation Gospel Choir de Trevor W. Payne. À partir de l’âge de huit ans, Jones avait poursuivi ses études musicales avec la soeur d’Oscar Peterson, Daisy Peterson Sweeney, qui lui avait enseigné la théorie et la composition de 1959 à 1960. Au début, Jones, qui adorait le baseball comme tous les jeunes de son âge, n’avait pas pris ses études musicales très sérieux. C’est alors qu’il avait été sévèrement réprimandé par son ami Oscar. Comme Jones l’avait expliqué plus tard, ‘’I liked to play baseball with the other neighbourhood kids, and one day I was a little late for my lesson. Oscar admonished me - saying that I’d have to take my lessons and practice time more seriously if I hoped to be successful in music.’’

Jones, qui avait grandi à quelques pâtés de maison de Peterson, était également devenu son protégé et ami. Enfant prodige, Jones était si doué que dès l’âge de trois ans, il pouvait interpréter les airs qu’il avait entendus une seule fois à la radio. Comme plusieurs musiciens de jazz, Jones avait fait ses débuts à l’église, notamment en se produisant aus côtés de ses parents à l’Union United Church. Il avait également joué dans les hôpitaux, les danses et les spectacles de variétés. Jones confirmait: "I did a lot of that, I won a lot of insignificant prizes doing that."

À l’âge de seulement neuf ans, Jones avait fait sa première performance publique dans un club dans le cadre d’une prestation en solo au Café Saint-Michel. Jones expliquait: "I had a trick piano act, dancing, doing the splits, playing from underneath the piano, or with a sheet over the keys." Durant cette période, Jones s’était également produit dans d’autres clubs et théâtres de la région de Montréal comme le Rockhead’s Paradise (1963). Dans une autre entrevue, Jones avait commenté: "It was fun, it was amusing and I had done it for quite a few years. But up until the time that I was 17 or 18, I really didn't take it seriously. I didn't think of it as being a step to becoming a pro musician, and especially a jazz musician. That was unheard of, other than Oscar and a few others who really had the talent."

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

Jones avait amorcé sa carrière professionnelle en participant à une tournée au Vermont et au Québec avec le groupe Bandwagon. De 1953 à 1963, Jones s’était produit principalement dans la région de Montréal, tout en faisant des tournées un peu partout au Québec avec des artistes comme Richard Parris, Al Cowans et Allan Wellman. C’est dans le cadre de son séjour au Rockhead’s Paradise en 1963 que Jones avait été découvert par le chanteur de calypso jamaïcain Kenny Hamilton, qui l’avait engagé comme directeur musical. Au début, le groupe de Hamilton avait obtenu un contrat d’une durée de quatre mois au Americana Hotel de San Juan, à Puerto Rico. Après la Révolution cubaine, les clubs et les casinos de l’île avaient été relocalisés à Puerto Rico, qui avait alors connu une sorte de renaissance. Jones précisait: "It was a wonderful time. Puerto Rico was really starting to flourish, so I was there during that heyday." Le groupe avait même fait des tournées internationales avec Bob Hope.

Jones s’était finalement installé à Puerto Rico avec sa femme et son jeune fils en 1964. Le groupe de Hamilton se produisait principalement dans les Caraïbes, mais faisait aussi de nombreuses tournées aux États-Unis, ce qui avait permis à Jones de travailler avec plusieurs chanteurs et de rencontrer de nombreux musiciens. Il avait également commencer à écrire des arrangements pour des chanteurs et des danseurs. En fait, Jones faisait tellement d’argent à l’époque qu’il avait pu s’acheter une maison à Puerto Rico. Tout en interprétant principalement des chansons du Hit Parade, Jones avait aussi commencé à développer un grand intérêt pour le jazz. Après le travail, Jones se rendait d’ailleurs régulièrement dans les clubs de jazz pour écouter les plus grands noms de l’époque.

Retourné à Montréal en 1980, Jones se remettait d’une opération à l’oeil droit lorsqu’il avait été visité dans sa chambre d’hôpital par le contrebassiste montréalais Charles Biddle qui lui avait proposé de former un duo. Jones expliquait: ‘’During that visit, Charlie told me that he needed a pianist, because my friend, the late Sean Patrick, was going back to teaching.’’ Après avoir hésité un long moment car il n’avait pas joué de jazz depuis un certain temps, Jones a finalement a ccepté l’offre de Biddle et avait commencé à se produiredans les clubs locaux et les hôtels de Montréal.

Jones se produisait avec Biddle depuis environ un an lorsque ce dernier avait décidé d’ouvrir un club sur la rue Aylmer, le Biddle’s Jazz and Ribs. Devenu très populaire, le club (devenu aujourd’hui la House of Jazz) attirait de nombreux amateurs. Décrivant cette période de sa carrière, Jones avait commenté: "It was the first time that I really had the opportunity to play jazz on a regular basis." De 1981 à 1986, Jones était d’ailleurs devenu le pianiste attitré du club. En 1981, Jones s’était également produit dans le cadre de la seconde édition du Festival international de jazz de Montréal, qui comprenait notamment des artistes comme Tom Waits, Dizzy Gillespie et Dave Brubeck. Très attaché à Montréal, Jones s’était produit au festival à chaque année jusqu’en 1999, se permettant même de participer à l’ouverture et à la clôture de l’événement à sept occasions ou de jouer en première partie de grandes vedettes comme Sarah Vaughan et Art Blakey. En 1985, Jones a d’ailleurs enregistré un album en duo avec Biddle dans le cadre du même festival.

C’est en se produisant dans le club de Biddle que Jones fut finalement remarqué par le producteur Jim West, qui était sur le point de fonder les disques Justin Time. Décrivant sa réaction lorsqu’il avait entendu Jones jouer, West avait déclaré: "I went to have dinner at Biddle's, and I was with my wife and another couple, but I wasn't paying attention to them at the table. I was listening to the music. I was fascinated. I couldn't believe how good it was."

West avait d’abord proposé à Jones d’enregistrer un album solo, mais ce dernier n’étant pas encore tout à fait prêt à prendre toute la place, il a plutôt proposé d’enregistrer un album en trio avec Biddle et le batteur Bernard Primeau. Jones poursuivait: “There was a lot of hullabaloo surrounding Charlie and myself. Anything pertaining to jazz, we were asked to do. I’d made my first recording. Truthfully, I was in a state of shock, because when you dream something for 30 years…”

C’est d’ailleurs Jones qui avait enregistré le premier album publiéde la nouvelle étiquette Justin Time en 1983. Intitulé ‘’Live at Biddle’s Jazz and Ribs’’, l’album qui était le premier enregistrement de Jones comme leader, mettait également en vedette Biddle à la contrebasse et Bernard Primeau à la batterie. C’est également dans le cadre de cet album que Jones avait expérimenté pour la première fois le jeu en trio qui était devenu par la suite son format de prédilection. Accédant enfin à la requête de West, Jones avait enchaîné l’année suivante avec un premier album solo intitulé ‘’The Many Moods of Oliver Jones.’’ Fort du succès de ces deux premiers albums, Jones avait énormément voyagé autour du monde, parcourant jusqu’à 200 000 miles par année et se rendant aussi loin qu’en Espagne, en Nouvelle-Zélande, en Australie, en Chine, au Portugal et en France.

Devenu de plus en plus populaire tant sur la scène nationale qu’internationale, Jones avait dû de plus en plus espacer ses apparitions au club Biddle. Devenu l’étoile montante du jazz canadien dans les années 1980, Jones avait même devancé le populaire groupe Shuffle Demons. En 1985, Jones avait traversé tout le Canada, faisant des apparitions dans les festivals et les clubs, que ce soit en solo ou en trio avec des musiciens comme Skip Bey, Bernard Primeau, Michel Donato, Skip Beckwith, Dave Young, Steve Wallace, Bernard Primeau, Jim Hillman, Nasyr Abdul Al-Khabyyret Archie Alleyne. Il s’était également produit en Europe. L’année suivante, Jones avait fait une tournée en Australie, en Nouvelle-Zélande et aux îles Fiji. Il a également présenté ses premiers concerts aux États-Unis, notamment au festival de jazz de Newport et dans le cadre d’apparitions au célèbre Greenwich Village de New York.

ÉVOLUTION RÉCENTE

En 1987, Jones a participé à une première tournée européenne d’envergure, notamment dans le cadre de prestations en Grande-Bretagne, en France, en Espagne, en Irlande, en Écosse, au Portugal, en Allemagne et en Suisse. Au cours de cette période, Jones avait également fait des apparitions dans de nombreux festivals de jazz, comme ceux de La Haye et de North Sea en Hollande (1987) de Monterey, en Californie (1988), et au festival JVC de New York (1989). De 1987 à 1989, Jones avait aussi collaboré avec des orchestres prestigieux comme le Symphony Nova Scotia, l’Orchestre métropolitain de Montréal, l’Orchestre symphonique de Québec, l’Orchestre symphonique de Kitchener-Waterloo ainsi que l’Orchestre symphonique de Montréal dans le cadre du Festival international de jazz de Montréal. Poursuivant sa carrière internationale, Jones s’était produit à Cuba et au Brésil en 1988, puis en Égypte, en Côte d’Ivoire et au Nigéria l’année suivante. L’Office national du film du Canada avait éventuellement immortalisé la tournée dans le cadre du documentaire ‘’Oliver Jones in Africa’’ publié l’année suivante. Le film s’était d’ailleurs mérité en 1990 le prix Golden Dukat décerné dans le cadre du Festival du film de Mannheim en Allemagne. La musique de Jones était également en vedette dans le court-métrage ‘’Season of Change’’, qui évoquait la saison que Jackie Robinson avait passée avec les Royaux de Montréal en 1946. Jones s’était également rendu en Namibie en 1990.

En 1993, Jones avait enregistré un second album solo intitulé ‘’Just 88.’’ Parmi les pièces de l’album, on remarquait deux compositions originales de Jones, ‘’Blues for Laurentian U’’ et ‘’Dizzy-Nest.’’ L’album s’est d’ailleurs mérité un prix Félix en 1994. La même année, à l’invitation du gouvernement canadien, Jones avait présenté une série de concerts en Chine. En 1995, Jones avait publié un premier enregistrement avec grand orchestre intitulé ‘’From Lush to Lively.’’ En 1997, Jones avait enregistré un album en trio intitulé ‘’Have Fingers, Will Travel’’. Enregistré aux studios Capitol de Los Angeles, l’album, qui mettait en vedette le légendaire contrebassiste Ray Brown et le batteur Jeff Hamilton, comprenait des pièces comme MMStreet Of Dreams", "If I Were A Bell" et "My Romance".

Même si Jones avait officiellement annoncé sa retraite le 1er janvier 2000, sa passion pour la musique était demeurée la plus forte. Décrivant les quatre années de sa retraite comme les plus intéressantes de son existence, Jones avait ajouté que cela lui avait laissé de temps d’enseigner à l’Université McGill et au Collège Vanier, en plus d’avoir travaillé comme directeur du Conseil des Arts du Maurier, qui soutenait le développement des arts un peu partout au Canada. Jones expliquait: ‘’I was truly enjoying my retirement. I took up golf at 65, and today I shoot 82-84, and on a good day I can break 80. I bought a house that backs onto a golf course in Florida, and I play at least three times a week. I generally shoot in the low 80s, and on a good day I can break 80. I have a great sense of joy in sharing the game with my son Richard. It’s odd; I lived all those years in Puerto Rico, and never took up golf.’’

C’est finalement André M��nard, le directeur artistique du Festival international de jazz de Montréal, qui avait sorti Jones de sa retraite en 2004. À l’époque, le festival était sur le point de célébrer son 25e anniversaire, et Ménard avait eu l’idée de célébrer l’événement dans le cadre d’un concert en duo à la Place des Arts mettant en vedette Jones et son mentor Oscar Peterson. Reconnaissant envers tout ce que le festival avait fait pour faire avancer sa carrière, Jones n’avait pu refuser. Il expliquait: ‘’The Jazz Festival has been very good to me, and really helped to put Oliver Jones on the map. Even though Oscar and I had been good friends since we grew up a few blocks from each other, we had never performed together.’’ Finalement, le concert avait remporté un tel succès que le carnet de commandes de Jones s’était rempli comme jamais auparavant. Jones poursuivait: ‘’Well... I started getting calls the day after the jazz festival concert. I figured that it might be nice to play 15 to 20 concerts a year. I called my agent, and he called back in a week with 59 different offers, including 40 dates in 2006.’’ Jones avait conclu en riant: ‘’Since then, retirement went out the window.’’ Très satisfait du concert, Ménard avait décrit la performance du duo de la façon suivante: ‘’It was very emotional. Oliver was relieved that it would finally happen, that he would share the stage with Oscar, and he said something very funny. He said, ‘Well, to be on the same stage as Oscar Peterson, for me, is a great feeling, but I wish I had his money.’’

Deux ans après le concert, Jones avait décidé de retourner en studio avec le contrebassiste Skip Bey pour terminer l’album ’’Then and Now’’, qui était resté inachevé en 1986. La même année, Jones était aussi devenu directeur artistique de la section jazz du Festival de musique de chambre de Montréal. En 2005, Jones a enregistré avec sa compagne, la chanteuse Ranee Lee, l’album ‘’Just You, Just Me’’, qui s’était mérité l’éloge du public et de la critique. En 2006, Jones a été en vedette dans le cadre du Festival de musique de chambre d’Ottawa. La même année, il avait aussi été nommé directeur artistique de la House of Jazz (anciennement le club de jazz Biddle’s) à Montréal. Toujours en 2006, Jones avait publié trois nouveaux enregistrements: ‘’One More Time’’ (avec le bassiste Dave Young et le batteur Jim Doxas), ’’From Lush to Lively’’ (avec un ‘’big band’’ et un orchestre à cordes) et ’’Serenade’’ (DVD). Jones a publié son dernier album intitulé ‘’Just for my Lady’’ en 2013. Continuant toujours de se produire sur scène, Jones avait été un des principaux invités du P.E.I. Jazz and Blues Festival de Charlottetown, à l’Ile du Prince-Édouard en 2011. Jones avait également été en vedette au Festival de jazz de Sudbury, en Ontario, tenu du 6 au 8 septembre 2013.

Victime de problèmes de santé en 2015, Jones avait annoncé officiellement sa retraite en janvier 2016 dans le cadre de la 10e édition du Festival international de jazz de Port-au-Prince. Jones avait présenté son dernier concert à la Barbade, le lieu de naissance de ses parents.

Très prolifique, Jones avait enregistré plus de quinze albums de 1982 à 1999, dont ‘’Lights of Burgundy’’ (1985), ‘’Cookin’ at Sweet Basil’’ (enregistré en 1988 au célèbre club Sweet Basil de New York) et ’’Just in Time’’ (enregistré au Montreal Bistro avec Dave Young et Norm Villeneuve en1998). Durant la décennie 1990, Jones se produisait plus de 130 fois par année. En 1992, Jones avait participé aux festivités entourant le 350 anniversaire de la fondation de la ville de Montréal aux côtés du big band de Vic Vogel et du Montreal Jubilation Gospel Choir dans le cadre de la soirée de clôture du Festival de jazz.

Jones, qui avait aussi entrepris une carrière de professeur, avait enseigné la musique à l’Université Laurentienne de 1987 à 1995. De 1988 à 1995, il avait été professeur à l’Université McGill. En 2009, Jones avait également parrainé la chanteuse Dione Taylor dans le cadre du Performing Arts Awards (GGPAA) Mentorship Program du Gouverneur-Général du Canada.

Jones avait remporté de nombreux honneurs au cours de sa carrière, dont le prix Procan qui lui avait été décerné en 1984 pour souligner sa contribution au développement du jazz. En 1992, Jones avait également remporté le prix Martin Luther King Jr. pour souligner sa contribution à la communauté noire du Canada et à sa ville natale, Montréal. Décoré de l’Ordre du Canada en 1993, Jones avait été intronisé chevalier de l’Ordre national du Québec l’année suivante. Jones était particulièrement fier d’avoir été le second musicien de jazz à avoir remporté l’Ordre du Canada après Oscar Peterson. Il précisait: ‘’Oscar was the first, and I was the second jazz musician to receive the Order of Canada. This legitimizes our particular type of music - that was relegated to the cellars for so long. So many other great musicians have also been honoured, including Phil Nimmons, Rob McConnell, and Moe Kaufman. I did to think that Oscar and I led the way.’’

En 1997-98, Jones avait aussi été le récipiendaire d’un prix Hommage du Conseil québécois de la musique. En 1999, Jones avait également été lauréat d’un Special Achievement Award décerné dans le cadre du gala de la Socan à Toronto. En 2005, Jones avait également été lauréat du Performing Arts Award décerné par le Gouverneur-Général du Canada. L’année suivante, Jones avait également été élu claviériste de l’année dans le cadre des National Jazz Awards. En 2012, le Festival international de jazz de Montréal a décerné à Jones le Prix Oscar Peterson. Le prix lui avait été remis par le directeur artistique de l’Orchestre symphonique de Montréal, Charles Dutoit, dans le cadre d’un concert présenté le 5 juillet au Théâtre Maisonneuve de la Place des Arts lors de la 33e édition du festival.

Jones avait remporté deux prix Juno: le premier pour son album ‘’Lights of Burgundy’’ en 1986, et le second pour son album de 2009 ‘’Second Time around.’’ Jones avait été mis en nomination neuf autres fois pour un prix Juno, y compris pour son album de 2012 Live in Baden. Jones était aussi récipiendaire de quatre prix Félix, décernés respectivement en 1989, 1994, 2007 et 2008.

En 2006, Jones s’est également vu remettre le prix de l’album de l’année dans le cadre des National Jazz Awards pour son album ‘’Just You, Just Me.’’ En 2010, l’arrondissement de Montréal-Nord a également rendu hommage à Jones en donnant son nom à la salle de spectacle de sa Maison culturelle et communautaire.

Le Service canadien des Postes a aussi émis un timbre en l’honneur de Jones dans le cadre du mois de l’histoire des Noirs en 2013. En 2017, l’ancienne athlète Rosey Ugo Edeh a rendu hommage à Jones dans un documentaire biographique de 48 minutes intitulé ‘’Oliver Jones Mind Hands Heart.’’ Le film a été présenté en grande première au Montreal International Black Film Festival la même année.

En 2015, Jones a également été nommé ‘’Grand Montréalais’’ par la Chambre de commerce du Grand Montréal. Il a aussi remporté le prix RIDEAU Hommage 2015 du Réseau indépendant des diffuseurs d’événements artistiques unis pour sa présence assidue sur les scènes du Québec. Jones est également titulaire de plusieurs doctorats honorifiques (Université Laurentienne, 1992; Université McGill, 1995; Université St. Francis Xavier, 1996; Université Windsor, 1999).

Considéré comme un des plus grands pianistes de jazz canadiens aux côtés d’Oscar Peterson et Paul Bley, Jones est caractérisé par un style lyrique et très mélodique alliant dextérité technique à un indéniable sens du swing. En dehors de sa carrière de musicien de jazz, Jones avait aussi accompagné plusieurs vedettes de la musique populaire. Souvent comparé à son mentor Oscar Peterson, Jones avait toujours été un peu flatté par la comparaison. Il s’était même souvent produit avec d’anciens collaborateurs de Peterson, comme Ray Brown, Clark Terry, Herb Ellis et Ed Thigpen. Dans une entrevue qu’il avait accordée en 2004, Jones avait d’ailleurs reconnu Peterson comme sa ‘’plus grande source d’inspiration.’’

Très influencé par Bach et Chopin, Jones avait toujours entretenu une certaine prédilection pour les ballades. La musique classique avait toujours occupé une grande place dans la vie de Jones. Même s’il possédait une importante collection de disques de jazz, Jones avait toujours préféré écouter de la musique classique pour se divertir.

Même si Jones trouvait souvent le bebop un peu répétitif, cela ne l’avait jamais empêché d’exprimer énormément de nynamisme et de vitalité dans ses pièces plus rythmées. Faisant état d’un concert de Jones au club Positano de New York en 1987, le critique John S. Wilson du New York Times écrivait: ‘’On remarque une légèreté de touche évoquant la facilité de [Art] Tatum et de [Oscar] Peterson, mais dans un contexte qui rappelle les grandes structures mélodiques et exubérantes d’Erroll Garner.’’ Compositeur prolifique, Jones avait dédié plusieurs de ses oeuvres à des amis et collègues, dont ‘’Blues for Chuck’’ et ‘’Big Pete’’, qui avaient été écrites en hommage à Chuck et Oscar Peterson respectivement. Parmi les autres compositions de Jones, on remarquait ‘’Gros Bois Blues’’, ‘’Lights of Burgundy’’, ‘’Snuggles’’, ‘’Fulford Street Stomp’’, ‘’Here Comes Summer Again’’, ‘’Dumpcake Blues’’, ‘’Hilly’’, ‘’The Sweetness of You’’, ‘’Looking for Lou’’, ‘’Bossa for CC’’, ‘’Stay Young’’, ‘’Blues for Hélène’’, ‘’Last Night in Rio’’, ‘’Sophie’’, ‘’Abunchafunk’’, ‘’What a Beautiful Sight’’, ‘’Jordio’’, ‘’Katatura’’, ‘’Mark My Time’’, ‘’Tippin’ Home from Sunday School’’, ‘’Stan Pat’’ et ‘’Peaceful Time’’. En 2012, Jones avait d’ailleurs interprété un répertoire composé exclusivement de ses propres compositions dans le cadre du Festival international de jazz de Montréal.

Oliver Jones avait enregistré vingt-cinq albums sous son nom au cours de sa carrière. Très apprécié sur la scène internationale, Jones avait fait plusieurs tournées à travers le monde, tant aux États-Unis qu’en Europe, en Nouvelle-Zélande, en Australie, au Japon, en Chine et en Afrique. Un des derniers trios de Jones mettait en vedette le contrebassiste Éric Lagacé et le batteur Jim Doxas. Jones appréciait d’ailleurs particulièrement de se produire avec de jeunes musiciens. Une semaine avant la présentation de son concert en duo avec Oscar Peterson en 2004, Jones avait évoqué son avenir en ces termes: "I know that I'll try to stick around for another couple of years. But after that, if I do anything at all, it won't be teaching but perhaps to motivate young musicians and artists and try to make sure that they get the opportunity to be heard and seen and get the exposure — which was very elusive in my era."

Commentant l’implication de Jones auprès des jeunes musiciens, Doxas avait expliqué: "My particular case is very explanatory. He wanted some younger musicians to 'burn the fire under his butt,' that's what he always said. Wherever we go, [Jones] always takes the time to give master classes, to listen to young musicians play, to get their CDs, to listen to their CDs." Commentant la contribution de Jones au développement des arts au Canada, Doxas l’avait décrit comme un des grands ambassadeurs de la musique et du pays tout entier.

Une des plus grandes satisfactions de Jones avait été que sa mère, qui avait vécu jusqu’à l’âge avancé de 102 ans, avait pu le voir connaître du succès dans le domaine qu’il avait choisi. Mais malgré tous ses succès, Jones n’avais jamais remporté le même succès que son idole et mentor Oscar Peterson. Né neuf ans après Peterson, Jones avait commencé sa carrière de musicien de jazz professionnel relativement tard. Le fait que Jones et Peterson aient joué à peu près le même style de musique était probablement une autre raison de cette situation.

©-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

SOURCES:

KASSEL, Matthew. ‘’Back Home With Canada’s Greatest Living Jazz Musician.’’ NPR, 12 juillet 2012.

‘’Oliver Jones.’’ Wikipedia, 2023.

‘’Oliver Jones.’’ All About Jazz, 2023.

‘’Oliver Jones.’’ Encyclopédie canadienne, 2023.

‘’Oliver Jones.’’ The Montrealer, 1er mai 2012.

PINCOMBE, C. Alexander. ‘’Jones, Oliver.’’ Dictionnaire biographique du Canada, 2023.

1 note

·

View note

Text

i’ll be your god of loss

(from “The God of Loss” by Darlingside, which will make you cry.)

so I was thinking about the trio and kids. Because these people, you know, they adore kids! they’re great with them! And they might not admit to that, they may not believe it, but we know it, we see it with Eliot and Molly, with Hardison and Trevor, with Parker and Josie, with the kids from The Stork Job and The Fairy Godparents Job and their clients’ children and so very many more.

Most of all we see it with Breanna. We see how they mentor her, how they provide advice, how they encourage her, how they build her up, how they laugh with her and speak of teaching her and telling her stories from the beginning. they unashamedly adore her. And they are so very good with her—they know how she looks up to them, they know they are always watched, and they behave like it. They are truly wonderful with her.

We know they love kids. We know, too, that they see the foster system’s flaws, and we know they fear for the children they save from bad situations. We see how they instinctively nurture the kids of the clients who have lost a parent. We watch how they will lift up the children of the marks who do not treat them well.

But they are not meant for white-picket fences.

These are not the kinds of people who settle down. They do not get tired of what they do one day and say “perhaps we’d best end this now.” They never get tired of it. They adore their work, they adore their life, they cannot imagine anything else. They will never willingly stop.

But there is a point where need eclipses want. There will be a day when they cannot do it anymore.

This is a known fact, but it is not a loved one.

The years trickle by. The time of Redemption comes and goes. They raise team after team, create an ever-reaching map of International, help people by the thousands and by the singles. And they are not the management. They leave that to the capable people they have trained, the ones they trust with their lives and more, and they keep doing the jobs, they stay involved, they get their hands dirty. Because there is nothing else for them. They began this doing what they loved, after all, and that love has not faded. If anything it has only grown.

Parker cannot sit still in an office all day, and Eliot cannot watch others fight and listen to them take the blows that he should, and Hardison will never be able to see all the things his algorithms raise and all the troubles that pass in the media and not do anything about it himself. This is against their very nature.

But the years go on and on, decades pass, and Hardison realizes one day that this cannot go on forever.

It is Hardison, because it is him who sits in the headquarters or the van or the discreetly close location with his laptop open and monitoring frequencies. It is Hardison, not Eliot or Parker, who can pay the most attention to the every soft grunt and caught breath and withheld noise of pain.

It is Hardison who realizes, one fateful day, that those moments increase day by day, job by job, and his injury logs have grown exponentially thicker in the last year. He watches their medical supplies drain away faster and faster even as he replaces them. More and more there are mornings when the other two linger between the sheets for longer than they used to.

It is he who watches Eliot squint ever more at the files and sees his glasses come out of his pocket with unusual regularity. There is a box full of spares in the bottom drawer of their wardrobe for when they break on the job. Hardison begins tipping the lid more often when he starts hearing the crunch of broken glass in his husband’s jacket pocket. They disappear faster these days.

(One day Hardison has had enough. He makes the toughest case he can and slips it into Eliot’s jacket pocket the night before a job. Eliot never says anything, but it lays on the bedside table sometimes when they’re off, and the glasses stop disappearing from the box so often.)

It is he who notices how Parker reinforces her rigs more and more, how ropes and straps support more than they used to and stretch further. The vents don’t thud so often these days. She has hung a hammock high in the rafters of their house, and he sees her less in the harness and more tucked away there.

(He adds padded bottoms to some of the vents and larger places to rest. Parker never says anything, but the vents rattle a little more often.)

It is he who observes how Eliot isn’t at the punching bag as regularly anymore, how he wraps his hands so carefully when he is, he who sees how Parker does not stretch quite as far as she used to, how she painstakingly plan jobs where she does not have to do a backbend or a particular contortion.

It is he who watches every time they step out—not jump out, no, not anymore—of the van, carefully holding on to the sides, and thinks to himself as he watches them walk away—

Is this the last time I will ever see you?

It’s Hardison who, whenever he finds a new job for them to do, eyes the circumstances and determines whether it’s something he can ship off to another team or not. His algorithms are prioritized now to chances of harm rather than potential jobs, attuned to the ever-growing injury logs. Their jobs begin to skew further to grifts and simpler building plans. But that never stops him wondering: Will this be the last job we ever take?

Will I send them to their deaths today?

For it is not his hair that fills with grey streaks faster and faster. It is Parker’s. When he sits behind her on the bed with her brush beside him, carefully separating her hair into strands for braiding, he finds more and more of them silvering.

(He watches her braid it every day, but some mornings she slips before him anyway. She was delighted when she discovered he could do it, courtesy of too many little sisters and not enough time in busy school mornings. It brings a grin to his face every time he thinks of her sunshine smile.)

It is Eliot’s, for there are late nights when Hardison finds him stretched out and half-asleep on the couch, and when he comes back with a blanket Eliot will be sitting up and waiting. He always sits beside him. Sometimes, Eliot lays back down with his head in his husband’s lap and lets him card gentle fingers through his hair. Those cherished moments become bittersweet when he finds that it is not so thick nor as deep in color as he remembers (though it is always soft).

And it is Hardison who bolts awake in the midst of the night with the ringing of the comms in his ears, clutching at the sheets to reassure himself he is not in the van he is not in the headquarters he is not on a job he does not have the earbud in his ear he is not listening to his lovers dying.

These nightmares plagued him from the beginning. He cannot count the number of times he has dreamt of sucking death-rattle breaths, the crack of spines, the sound of screaming in his ears, cannot count the times he has dreamt of searching and searching for bodies. Sometimes he does find them, staring eyes and crushed ribs and mangled limbs. Sometimes he doesn’t. Sometimes they aren’t dead at all—but those times he never finds them. He can never figure out which is worse.

But the nightmares have never been so bad as they are now.

Other nights he does not sleep. Other nights, he sits awake and watches his lovers’ scarred chests rise and fall in deep slumbering breaths, and wonders when will I lose you? A year from now? Two? Or only months, only weeks?

What if it’s tomorrow?

He wakes to the others’ weeping often. But he thinks they are the ones comforting him more these days.

Finally Hardison has had enough.

They can’t do this any longer. He can’t do this any longer. Hardison cannot live without them, these two lights of his life, his sun and moon and bright diamond stars—but he knows he will die last, should they continue down this path, and he will die alone and many years from now.

For it is not he who takes punch after punch from men decades younger than himself, who climbs into stories-high elevator shafts where one wrong button-press could end it all, who stares down the barrels of guns without one himself, who hangs off the sides of buildings by his fingertips, who pushes and pushes and pushes his body day in and day out. His husband and wife are resilient. The odds say that they should have been unable to keep doing this a decade ago—and the odds are wrong.

But Eliot and Parker are not the kinds of people who can merely stop. There will never be a day, Hardison knows, when they will sit down with him and say we do not want to do this anymore. They will push and push and push themselves till they break.

Hardison knows what their breaking will look like. His dreams have told him so. Hardison will not, will never, let that happen on his watch. He will have to stop them.

If he asked, they would. It would take coercing, it would take shouting and arguing and probably many hours of the two of them off on their own and thinking, but they would.

But Hardison turns this over in his mind as he forges paintings and writes code and sends out emails to the teams, tries to picture stopping, and it makes him go nearly as cold as the thought of breaking does.

Stopping means no more jobs. No more jobs means…

Well, it means a lot of time spent volunteering, he supposes, and overseeing International’s teams. It means a lot more nights spent at home and not hotels. More of Eliot’s home cooked meals, he guesses, and more movie nights, more trips for fun. The medical kit wouldn’t have to be refilled nearly as often. Eliot’s box of glasses would never have to be replenished again. It means fewer days spent watching his partners hobble around and deny that they need to sit. Hardison wouldn’t have to plan jobs around the weather that makes their bones ache, or watch Parker wince as she drops out of a vent, or notice how Eliot needs the volume in his comm brought up higher than he used to.

There would be no heart monitors that spike and fall on the screens.

Hardison thinks of this, and then he imagines Parker and Eliot in their house, day in and day out, and it brings a shake to his breath rather than a steadiness.

Ever-moving Parker and Eliot, his never-stopping always-going wife and husband, for whom he has to fill the house with distractions to keep them from pacing and snapping and looking for trouble. Parker has vents and climbing systems and a room full to the brim of boxes of locks, safes, puzzle-boxes, books of riddles, absolutely anything and everything that could challenge her.

There’s a small gym for Eliot. Hardison always puts new gadgets and cookbooks in the kitchen, and he’s found that there are indeed some books that Eliot will spend hours reading (assuming he can find his glasses). A guitar found its way into the living room one day, and now books of music pile up on the nearby shelves. He keeps a closet specifically for outdoor gear.

But there are only so many meals that can be cooked. Parker is already bored of most of the puzzle room. More than that, they both have to move. Challenges from books and puzzles and games have never and will never be enough for them.

Hardison thinks of them in that house, day in and day out, growing wearier and wearier of what they have, growing tired of what life has to offer, and it sends a racking shudder through him.

He goes on, day in and day out, and he watches them, and they push themselves, and he worries and he wonders and he dreams and he fears.

And then, one day, it hits him.

They’re sending off yet another kid to the foster system. Hardison will track them and make sure they find the right place, but it always aches a little to watch them go. He’s been through that hell. There is nothing he wouldn’t give not to help them. The three of them always see them off, but it never feels like enough.

This time, though, he’s rushing, running to meet them. The kid is already leaving. Parker and Eliot watch them go, tension laced in their shoulders, and it occurs to him that he rarely ever watches them watch the kid.

They look with the same love in their eyes he saw so many years ago. In a moment he is struck with memories: listening to Eliot teaching Molly how to hit balloons with a dart in the mirror, Parker putting her hands over Josie’s ears as she taught her to break into a car, the worried love in his husband’s voice as he searched for the girl he had known for mere hours, the outraged passion of his wife’s protectiveness over the teenager she had seen so much of herself in.

There is the ringing of Parker’s half-choked declaration they’ll wind up like me. There is the way Eliot had spoken of Cory, a boy who still carried his father’s lunchbox while he worked in a mine for his family. There’s the kid from the boxing ring and the kid whose father was killing himself in the ice rink and the children tackling Eliot in the school and, and, and—

—and Hardison remembers teaching bright, precocious Trevor about hacking when they were trying to steal a goddamn potato of all things. And of course Breanna, wonderful, perfect Breanna, who leads International now. Breanna, whom he spent so many long, long days and nights teaching how to hack and how to build software and hardware and engineering and whatever else she asked of him. Breanna, who called even when it was four in the morning for her, just to hear his tales of the crew. She still calls. Half the time it’s only to hear their voices.

With her comes the loud, bustling noise of Nana’s house, the shouting echoing off the walls, the warmth of his little siblings on his hip, the attention and focus it took to put braid after braid in his sisters’ hair. Nana was forever busy with the kids. He still loves coming over as often as he can to help. One thing never changes—her house is forever noisy. There are always new kids around, and there are always lessons to be taught: how to fold laundry, how to dance along to a song without worrying whether you’re doing it right, how to complete all of your schoolwork for the night, how to speak kindly, how to work together, and the most important one of all:

Love yourself.

Nana’s work is never done. She is always busy.

Eliot and Parker cannot stand to be still. They need to be doing something. But most of all, they have to be helping someone.

The puzzle snaps together like a flash of lightning. As the thunder rolls, so does his mind: he knows precisely what he needs to do.

First there’s the matter of housing. Their house is big, but not that big, and anyway, the only home that matters to them is each other. Nana’s only one person, and she can manage plenty of kids on her own. Between the three of them, Hardison is sure they’ll wind up with quite the brood.

There are any number of mansions lying around the States. It’s shocking how many there are. They’re not small, either: most of them could fit a whole extended family in them, though most of the time they’re just bought by too-rich people who can’t hope to fill a quarter of the space. Hardison should know. The crew has infiltrated plenty of them. But he knows they’ll find a way to put one to good use.

He searches for the ones that are unlikely to be bought and only takes up space. There’s a lot of them, half too damaged to be good for anything, but one sticks out: secluded with beautiful grounds, an area with good (but not too good) schools, a half-decent price point, and a bit of a fixer-upper.

Standing on ladders and driving in nails isn’t not physical, but it’s a lot better than dodging punches or dropping two stories off a building. Giving Eliot and Parker a project right off the bat will help ease the blow of quitting the jobs.

Then he hunts down research. He already has shelves upon shelves of books on psychology and parenting and foster children and anything else that could be helpful, but there’s always more to read. A refresher course is important.

While he’s got algorithms searching for that, he sets some to hunting down more details on the local area as well as building renovations, then begins building a plan. He’ll have to introduce the idea slowly. Parker and Eliot won’t be opposed, per say, but getting them to completely agree will be a challenge.

It takes a few weeks, but it’s going well, and Hardison’s almost ready to present his idea to them.

Then his world shatters.

It’s another job, another day, another time when he watches his lovers head out the door and wonders will it be this time?

Except then will it be this time? changes to oh God, it’s this time.

Eliot’s breaths choke off at the same time something crunches.

Parker screams his name so loud Hardison’s ears ring. Or maybe that’s him—maybe that’s him screaming so hard that the taste of blood coats his throat—but it doesn’t matter because Parker’s cut off with a jerk and the comms go dead and they are dead dead dead and—

The world spins and drops out. The next few hours are black but for agonizing pain.

His only memory is not of sight or sound or hearing. It’s touch, the thready warmth of two pulses flickering under his fingers.

They tell him later that he found them in the nick of time: two unconscious bodies collapsed side-by-side in a back alley, and him, clutching their wrists with 911’s number still glowing on the phone beside them. Apparently he rode in the ambulance, because they couldn’t get him away from the other two without restraining him. Every time they tried they feared they’d hurt him.

What he remembers next is this: waking in a plastic chair, head dizzy (with sedatives, he learns later), an ice-cold knife of grief sunk into his heart and tears coating his cheeks, to the steady paired beeping of twin heart monitors.

They survive. Miraculously, they survive, somehow with only minimal injuries. Hardison knows it’s only because of the advancements made within the last few years. Three days later they’re out of the hospital and back home, Eliot on crutches and unhappy about it, Parker complaining at length over the stitches in her arm. Hardison can’t even be annoyed by it. They’re here and they’re alive and they’re still here.

He gives them the evening. But the next day he’s up even before them, spreading papers on the table and making breakfast at the stove (because you learn some things when your husband is a world-class cook) when the two of them come to the table.

When they ask, he doesn’t bother to soften the blow. This is the last time he’s doing that. They’re done.

Eliot and Parker look at each other, then at him. They nod.

He blinks. Just like that? he wonders, and then asks it aloud.

“We don’t want to hurt you again,” they answer, and his heart could break with relief.

When he presents the plans they answer with all the joy he had hoped for. They’re worried, of course—will they be fit to care for children?—but Hardison only rolls his eyes and reminds them of Breanna and Josie and Molly and Cory and all the rest, and they relent.

Two months later they move out to the mansion. It’s a difficult project. Even Hardison didn’t anticipate how long it would be (though Eliot grumbled at him about how much harder this would be than it seemed, dammit, Hardison, what have you gotten us into this time?) but it’s good work, hard work, busy work. He doesn’t have to watch them pace in a hotel room with boredom. There is no angry snapping born of too much time spent sitting around. They work and Hardison blasts music and the other teams chat with them over voice calls.

Some nights Eliot sits in the central hall, the ceiling four stories above them and laced with Parker’s rigs, and plays new songs for them on his guitar. They all sing along when it’s one they know. The acoustics of the room are perfect for echoing and strengthening their voices.

Other nights they curl up on a pile of king mattresses spread three-wide and two-deep, blankets heaped high, and whisper stories to one another before falling asleep to the songs of morning birds outside the windows.

Hardison still wakes screaming. Eliot and Parker do too. But it’s not every other night anymore, and now that they aren’t on jobs, his nightmares begin to recede.

(Of course there’s always the recurring one that did happen. Sometimes he sleeps with their wrists in his hands or his fingers pressed to their necks, just to reassure himself their hearts are still beating. If Eliot and Parker are still awake, one of them will pull him close and press his ear against their chest, and he falls asleep listening to their heartbeat.)

Some of the International people show up to help. They come with suggestions and ideas that get put to good use. Breanna delights in helping them pick out the tools for a massive workshop. His other siblings come too, and he puts them to work. Nana is too old for traveling these days (though he knows she’ll outlive them all), but she talks to them over video calls and gives them tips on how to make everything work.

“How on earth are you going to handle so many kids?” some of them ask. “You’re looking at a school’s worth.”

The three of them just smile. They’re up to the task—and besides that, there’s a number of people from other crews who are also on the brink of retirement. An entire section of the manor is planned for incoming helpers: they won’t be alone for long.

Finally the mansion is done. Or, well, done enough. It’ll always be a project. There will always be a room that needs repainting, or a sink that breaks out of nowhere and needs repairing, or a piece of roof that’s leaking. But it is more than livable—oh, so beautifully livable, the best home Hardison has ever found for them, filled to the brim with all they could ever want.

There is a library with shelves that stretch two floors up, filled with more books than he could read in a lifetime and skylights flooding the room with sunlight. The gym has endless features: a dance studio, a martial arts room, weights, gymnastic mats and bars, a goddamn ball pit because Parker loved the idea, and slides to go with it. Eliot has the biggest and best kitchen he could have ever dreamed of. There’s even a walk-in fridge and freezer.

(“The hell do you expect me to be cooking for, an army?” he asks once, and Hardison laughs.

“Worse. Kids.”)

They’ve made the bedrooms a little plainer than usual, though they have rooms filled to the brim with furniture and curtains and decorations of all shapes and sizes. It will be the kids’ home too. They deserve to decorate their own rooms, no matter how long they’ll be staying.

There are movie rooms, and rooms of pillows and couches and blankets, hidey-holes aplenty (Parker knows them all), games, puzzles, music (Hardison’s pretty sure a band could set up shop in there), art, writing spaces, closets and closets waiting to be filled, bathrooms with tubs big enough to be small pools, a real pool both indoors and out, and Hardison sometimes loses track of what else. They make sure all but some reserve rooms are used and functional. None of them will let this space go to waste.

Getting everything up to code is a job and a half, but there’s plenty of disabled International people (and Hardison’s siblings too) who give them pointers and let them know who the right people to call are. Hardison delights in picking out elevator music. Eliot informs him that programming them to play The Imperial March every time he uses them is not as funny as he thinks. Parker plans little puzzles in Braille and puts them in all sorts of places.

She, of course, has rigging all over the place. The high ceilings are her dream. There are hammocks everywhere. Eliot adores the greenhouse and gardens, spending hours mulling over plans and determining precisely what will work best. Hardison watches the lawn service mowing the massive yards and mulls over the best use for them. There are paths aplenty for running and walking. Eliot’s got a whole space mapped out for an orchard. Parker’s claimed a not-insignificant section of it for mazes and a high ropes course (which is going to be godawful hard to build, but he can’t wait to watch the kids on it).

Hardison’s read a lot of books and seen a lot of research supporting animal-raising as an excellent activity for kids. And he’s always wanted a dog.

When they visit the local shelter they end up with three (because Eliot’s a softie for them) and two cats. He plans a chicken coop in the back and goes to long-term planning for more farm-type animals. Parker has come to love horses over the years, and he knows Eliot’s fondness has never faded. Maybe a stable or two.

Their adoption and foster papers process not long before they’re done. (Hardison technically already had them, but they hadn’t been done the legal way, and though the law is pretty stupid about this whole thing he still wants to do it right.) Then it’s time to get to work.

They’re careful, of course. They begin with two siblings in the summer. Both are teenagers, that age where it’s hard to get them into a foster home, let alone to adopt. (Of course the three of them aren’t looking for adoption unless the kids want it. They’re human beings: they get to choose their own parents.) Both are quiet and wary, looking overwhelmed as they stare up into the manor’s heights.

Parker and Hardison exchange glances, wincing. They’d known from experience that this might be tricky.

They start small, relegating everything to a single wing. It’s around the size of an ordinary house, maybe a bit bigger, and while the three of them have their own rooms elsewhere they make sure to sleep nearby. (That’s something else the kids look at them strangely for: there aren’t many polycules who foster kids, after all. There aren’t many polyamorous couples visible in the media period, though that’s changing with Breanna’s generation. )

When Eliot loads one kid’s laundry into the machine (and oh, they need to go shopping so badly for these kids), he finds a worn dress at the bottom of a pile of boy’s clothes. The same kid, he recalls, who had shaken their head a little when he had asked them about haircuts, whose hair was already brushing their shoulders. It’s fraying at the edges, obviously well loved. There’s a hole in the skirt. When he brings the laundry up he takes out the sewing kit (well, a piece of it—there is a truly enormous area of the arts room dedicated to material arts) and makes sure to fix the hole before he puts everything in the closet. The dress goes first and foremost, hung delicately on a special hanger.

The days go by, the kids become more open, and a routine falls into place. They fill closets with dresses and scarves and put boxes of pins with pronouns in their rooms. Eliot teaches them to chop vegetables and shows them basic self-defense. He helps them walk the dogs, and when he offers they let him teach them meditation.

Parker takes them to therapy (a tricky conversation, but well worth it) and shows the younger one how to climb. The older one is more interested in puzzles, and she happily complies, bringing out a massive box full to the brim with puzzle-boxes.

Hardison, for his part, puts together movie nights and video gaming sessions. He shows off the library and makes sure they know where to find everything, as well as the rules of the house. When one of them shows an interest in fandom, he makes sure they know where the cosplay stuff is. One day he starts a DnD campaign with all four of his family members.

Four becomes five, five becomes seven, the school year begins and some choose homeschooling and others choose public. Homework is done, meals are cooked, dogs are fed, cats are befriended, lightsaber battles play out in the yards and Nerf gun fights are had in the halls (Eliot still prefers a shield), pillow fights go down, tears are cried and arguments ring out in the halls, the fridge doors and pin boards and walls are covered in artwork, kids eight, nine, and ten show up, conversations about queerness are had, a Pride parade is attended, there’s therapy and therapy and so much therapy, sports teams are joined, clubs are attended, problems occur and they handle it, they handle it, they handle it all no matter how hard it is.

Hardison isn’t sure he’s ever seen the other two so happy. He, for one, cannot contain his joy. The children are hard but they are wonderful, bright sparks ready to go out into the world with no one to dim them.

There is a baby one day that International directs to them. The rest of the kids dote on them. The work is hard, but they manage anyway, and there’s three of them to get up when the little one cries. There is nothing more endearing than watching Eliot asleep with a tiny baby crooked in his arm or Parker carefully climbing with them strapped to her chest.

One day, as he’s sitting on the porch with the other two at his sides and watching the kids play, he glances to the sides and realizes that his partners have gone fully gray. He himself finds his joints creaking more and more these days.

The International retirees are doing fantastic and Breanna is the perfect heir to their throne, directing teams with all her brilliance while getting her own work in on the side. She’s mentioned she thinks she might hand it off to one of her own proteges, just so she can go back to some of the old work.

We built a legacy, he thinks, and then, We built a legacy, and we are here now, and they did not die and leave me here alone, and we are happy.

He realizes Eliot and Parker are looking at him with that we know what you’re thinking expression. They smile at him when he notices. Parker kisses his cheek and Eliot pulls him closer on the porch swing, and though they say nothing at all, he knows they’re all thinking the same thing:

We got our happy ending, and we made sure everyone else will too.

#leverage#leverage fic#I swear to you this wasn't going to be as long as it turned out to be#leverage redemption#leverage redemption spoilers#tw minor gore#leverage redemption fic#fanfic#synapse writes#synapse fanfic#leverage meta#meta#eliot spencer#alec hardison#parker#parker leverage#leverage ot3#ot3: hitter hacker thief#eliot spencer/alec hardison/parker#is that all the tags...?#hopefully#anyway this is not beta'd and it's not my usual fic#typically it's more polished#hence: TUMBLR POST#y'all I have so much work#I have SO MANY other things I need to be doing#I do not know WHY I do this to myself#so this is my happy ending for the ot3#because. them and kids. THEM AND KIDS

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art F City: Highlights, and a Sad Observation, From MICA’s Commencement Exhibition

Ceramics by Keli Beth Smith.

As a rule, we don’t generally discuss student work on the blog. There are plenty of reasons for this, but for me, one is simple: I am forever grateful no one from the art press ever saw the terrible work I was struggling through in art school.

Yet nearly every Spring, I am impressed by commencement exhibitions—how is it possible that so many college seniors have their shit together more than so many grown-ass artists? Thesis shows at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), my old alma mater, tend to be particularly polished and worthwhile.

This year, though, has been a rough one for students nationally. I can’t imagine dealing with Trump’s election in the Fall and inauguration at the start of the Spring semester, all while trying to figure out what the hell you’re doing with your last year of art school. So much work looks like students just gave up hope halfway through a concept—as if a collective trauma had left everyone dispirited and unable to focus. We at AFC can certainly sympathize. The situation is fucking unfair.

That’s why this year we’re covering the MICA commencement show, which closes today (go see it if you’re in Baltimore!). Although it’s overall less enthusiastic and high-caliber than years past, those who persevered through the crisis and turned it out deserve recognition. It’s worth noting that the sprawling show could, in general, benefit from some outside curatorial advice.

Below, the stand-out highlights from the class of 2017. If they can survive pulling-off thesis projects this good in spite of (and often in reference to) the apocalypse, the art world will be a cakewalk:

Chas Druin

Chas Druin’s work in the Gateway Building stands out for several reasons. It’s one of the best strategies for displaying garments I’ve seen employed here—they take on an eerie, vaguely sinister presence that complements the work’s dystopic vibe. The individual pieces recall military or ritualistic uniforms that have been deconstructed and reconstructed into odd forms that would fit awkwardly on typical bodies. One form, which might be a peacoat re-tooled into some sort of protective suit for radiation, looms menacingly over a more feminine (but still gender ambiguous) ensemble. This collection is what Comme des Garçons costumes for The Handmaid’s Tale would look like,��one of many reasons it feels timely.

“Family Portrait” installation view, featuring A.F. Oehmke and Emily Walla.

Tucked away in an upper studio of the Fox Building, A.F. Oehmke and Emily Walla’s collaborative installation makes the overhung gauntlet in the rest of the building worth it. Walla’s sculptures reference impractical midcentury modern furniture. They’re flawlessly crafted, but suggest fragility and an uncomfortable domestic sphere—this is a precarious home where inhabitants and visitors must walk on eggshells. The only splashes of color are a few sparse houseplants and tabloids (“Our Catastrophe”) from A.F. Oehmke scattered on several of Walla’s pieces. “Our Catastrophe” has headlines such as “SHIT’S FUCKED UP!” and “ARE WE ALL BECOMING KIM?!?!?!?!?!?! JERRY SALTZ WEIGHS IN!” The decline of Western Civilization, indeed.

Trevor Blauth, “Epitaph,” installation view.

Trevor Blauth’s Epitaph was one of the first rooms I encountered in the Station Building, and perhaps became the high standard by which I considered all subsequent shows. The installation has an immersive quality that speaks to the remarkably high production value. And like most of this year’s highlights, it’s fraught with anxiety. The gallery is full of sod, with industrial-looking wishing wells (one of which holds a Fiji water bottle floating in dirty water) and a full-scale greenhouse. In the greenhouse, an old TV displays a video game avatar waiting endlessly on a futuristic subway platform. There’s no controller, so the viewer just watches the back of the protagonist as background characters pass him by. Scattered around the gallery, burnt pieces of paper display tiny text, such as “I think happiness is what makes you pretty. Period. Happy people are beautiful. They become like a mirror and they reflect that happiness.” It’s not mentioned in the text, but it’s a quote from Drew Barrymore, the artist whispered to me.

Reece Cox, “Acids in the Style of Phineas Gauge”

Down the hall, Reece Cox’s “Acids in the Style of Phineas Gauge” would be easy to miss if it weren’t for its rumbling soundtrack. Thankfully, it drew me in. It’s one of the most understated but oddly rewarding installations. The artist has replaced all the fluorescent bulbs in a grim conference room with lime green lights. They match the color of sunlight trickling through the tree canopy of the overgrown train tracks outside perfectly—extending the surreal quasi-urban/quasi-wild outdoors into the institutional space. As if to remind the viewer of the room’s usual lighting, a haphazard strand of LEDs flashes occasionally in synch with Cox’s droning music. It’s strangely elegant in its simplicity and honesty (the four speakers are visible, no effort is made to clean up the cords, and the whiteness of the simple light tube references the artifice of the intervention).

Alison Baskerville. “Turf War”.

Of all the vaguely post-apocalyptic work in this year’s commencement show, Alison Baskerville’s Turf War feels the most fun. Her space is littered with technicolor garments that include Balaclavas with slogans such as “HOLLYWASTE” and “CHESTCOAST”. A monitor displays a strange, ritualistic fight club that’s somewhere between lucha libre, a fashion show, and worldstarhiphop.com brawls.

This is the suburban nightmare of the not-so-distant future—if Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome predicted leather would outlast civil society, Baskerville seems to argue it would be synthetic weave, faux-fur, plastic sequins, and all the dayglo vinyl and polyester fabrics that go on sale after Halloween.

Keli Beth Smith, “Slam Pig”.

In the adjoining gallery, Keli Beth Smith’s ceramic pieces get a nod for their versatility and demonstration of mastery over the craft. These include her fetish formal china (top of the page) and figurative sculptures such as “Slam Pig,” in which two golden figures lay on an animal hide masturbating facing away from each other. I should mention that masturbation is a recurring motif across every discipline this year. I suppose that’s one tried-and-true strategy for stress management? At any rate, these ceramic figures are a little unsettling due to their size—they’re proportioned like adults, but scaled to be the height of children. These wouldn’t look out of place in a blue-chip gallery.

Will Staub

I have a soft spot for Will Staub’s takeover of the Gateway Building’s cafe, largely because I once worked for the school’s food services company, and he certainly interrupts the monotony of that post. Staub repackaged the instant food items for sale, so that Goya blackbeans now come in a breakfast-cereal-proportioned box or Chicken of the Sea tuna can come in a potato chip bag (gross). All of the labels have a strange warped quality, as if they had been scanned from their original packages and then reformatted to other shapes regardless of their dimensions. When we visited, the cafe was closed, but an instruction sheet provided for employees filled us in. Everything is for sale, including regular menu items which would be covered with a red dot once ordered. His items, however, can presumably be restocked. Bagged goods cost $10 and boxes $20. That’s a little steep for campus food options (just slightly, sadly), but a damned bargain for an art object (consider Gabriel Orozco’s collection of $30,000 convenience store products, rigged to depreciate with an economy of scale). This feels like a sounder investment.

from Art F City http://ift.tt/2rk2TPg via IFTTT

0 notes