#Theadora Van Runkle

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

New York, New York (Martin Scorsese, 1977).

#new york new york#martin scorsese#liza minnelli#robert de niro#lászló kovács#bert lovitt#david ramirez#tom rolf#boris leven#theadora van runkle

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theadora Van Runkle’s costume sketches for Faye Dunaway in Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suits created by costume designer Theadora Van Runkle for Faye Dunaway in the film, "The Thomas Crown Affair" directed by Norman Jewison in 1968.

Tailleurs créés par la costumière Theadora Van Runkle pour Faye Dunaway dans le film, "L' Affaire Thomas Crown" réalisé par Norman Jewison en 1968.

#faye dunaway#american actress#theodora van runkle#thomas crown affair#norman jewison#1968#style 60s

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty in Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967)

Cast: Warren Beatty, Faye Dunaway, Michael J. Pollard, Gene Hackman, Estelle Parsons, Denver Pyle, Dub Taylor, Evans Evans, Gene Wilder. Screenplay: David Newman, Robert Benton. Cinematography: Burnett Guffey. Art direction: Dean Tavoularis. Film editing: Dede Allen. Music: Charles Strouse.

Calling a film a landmark, as Bonnie and Clyde so often has been called, does it a disservice in that it prioritizes historical significance over the aesthetic ones. It makes it difficult to appreciate or criticize the movie without recalling what it was like to see and to talk about the first time you saw it -- if, like me, you saw it in a theater when it was first released. It's a landmark because its success showed the Hollywood studios, which were mere surviving remnants of the old movie factories of the '30s and '40s, that there was an audience for something other than the big musicals and epics that had dominated American movies during the 1960s. There was a young audience out there that had grown up with the French New Wave and the great Italian and Japanese films of that decade, and was resistant to piety and platitudes. Along with The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967), Bonnie and Clyde gave this audience something they were looking for, and fed the revolution in filmmaking that made the 1970s one of the most adventurous decades in film history. It's no surprise that the screenwriters, Robert Benton and David Newman, were so familiar with the New Wave that they wanted François Truffaut or Jean-Luc Godard to direct their movie. And even today Warren Beatty, in the opening scenes of Bonnie and Clyde, is bound to remind one of Jean-Paul Belmondo in Breathless (Godard, 1960). It was a movie that launched the careers of Faye Dunaway and Gene Hackman, not to mention giving Beatty a boost into superstardom. It also put an end to some careers, most notably that of Bosley Crowther, who had been the New York Times's film critic since 1940 but was undone by his vitriolic attack on Bonnie and Clyde, which he denounced not only in his initial review but also, after protests from the movie's admirers, in two subsequent articles. Crowther was replaced as the Times critic in 1968. On the other hand, Newsweek's critic, Joe Morgenstern, initially panned the film but, after being urged by readers to reconsider, recanted his original critique. So the question persists: Historical significance aside, is Bonnie and Clyde really any good? I'd have to say, after seeing it again for the first time in many years, that it holds up as entertainment. The acting is superb, and Burnett Guffey's cinematography, Dean Tavoularis's art direction, and Theadora van Runkle's costuming all provide a fine 1960s interpretation of 1930s style. Where it falls down for me is in substance: The screenplay, which was worked over by Robert Towne, is too preoccupied with Bonnie and Clyde as lovers with (especially Clyde) some psychosexual hangups. It only feints at demonstrating why the pair became cult figures in the Great Depression, most notably in a scene when Clyde refuses to take the money of a farmer who is in the bank they're robbing, and in a scene in which the wounded couple and C.W. Moss (endearingly played by Michael J. Pollard) stop for help at a bleak migrant camp. Only in scenes like these do we get a sense of the deep background of Depression-era misery, a fuller treatment of which might have elevated the film into greatness, the way Francis Ford Coppola's first two Godfather films (1972, 1974) turned Mario Puzo's popular novel into an American myth. Otherwise, the criticism that it glamorizes the outlaws by turning them into fashion-model beauties still has some merit.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Bruce McBroom (American, b. 1939) [Publicity still, The Godfather, Part II, Robert De Niro as Vito Corleone] Ca. 1974 Gelatin silver print Dick Smith [Makeup test photographs of Robert De Niro as Vito Corleone] Ca. 1973 Gelatin silver print Bruce McBroom (American, b. 1939) [Publicity still, The Godfather, Part II, Robert De Niro and Francis Ford Coppola] Ca. 1974 Theadora Van Runkle's costume design for Vito Corleone in The Godfather, Part II, Ca. 1973 Gelatin silver print with fabric swatches Note by Robert De Niro for The Godfather, Part II, "Impressions of older me," 1973 Robert De Niro Papers 66.3, 66.1, 65.7, 65.4, 182 --- Francis Ford Coppola considered casting Robert De Niro in the role of Michael Corleone in The Godfather but ultimately cast Al Pacino instead. The film was a blockbuster hit, nominated for 11 Academy Awards and winning three: Best Actor for Marlon Brando, Best Adapted Screenplay for Coppola and author Mario Puzo, and Best Picture. Coppola initially had no intention of making a sequel but was eventually persuaded by Paramount Pictures to do so. To play the young Vito Corleone in The Godfather, Part II, Coppola chose Robert De Niro, remembering De Niro's audition and his performance in Mean Streets. True to his process, De Niro studied the screenplay, conducted background research, and traveled to Sicily to improve his Italian and master the accent. He also arranged for videotapes of The Godfather to be made so he could study Brando's performance, noting the gestures and movements he might use in building his own portrayal of the character on the page here titled, "Impressions of Older Me." In an interview with Photoplay magazine, De Niro said, "I didn't want to do an imitation, but I wanted to make it believable that I could be him as a young man. I would see some little movements that he would do and try to link them to my performance." Celebrated special effects makeup artist Dick Smith, who had created Brando's makeup in The Godfather, created De Niro's makeup. And Theadora Van Runkle, known for her costume design work on Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Bullitt (1968), also helped De Niro construct the character of the young Vito Corleone. The film was an artistic and popular triumph, becoming Paramount Pictures' highest grossing film of 1974 and prompting many critics to declare the film superior to the original. The film's success and De Niro's win for Best Supporting Actor at the Academy Awards amplified his clout in the film industry and gave him more power to choose roles he found interesting and satisfying.”

#robert de niro#robert de niro archives#robert de niro hrc#hrc archives#harry ransom center#ut austin#films#film history#photographs#storyboards#scripts/notes

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

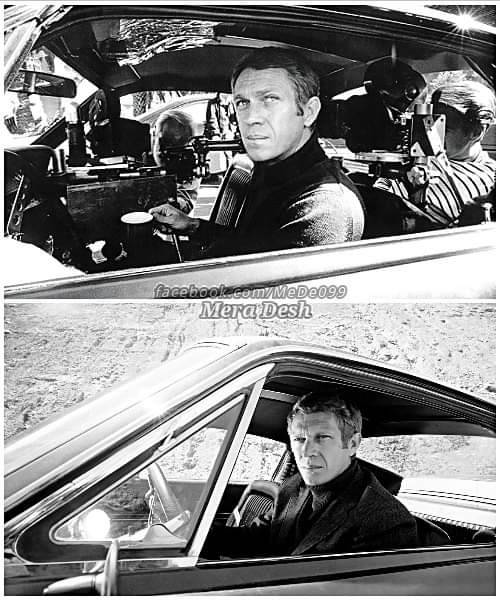

In the opening chase sequence of "Bullitt" (1968), a dark green 1968 Ford Mustang GT tears through the steep, undulating streets of San Francisco. The roar of the engine echoes off brick walls as Steve McQueen’s Lieutenant Frank Bullitt tightens his grip on the wheel. This electrifying scene isn’t just a cinematic moment; it’s a masterclass in coordination, precision, and raw power that has since redefined the action genre. But creating such an iconic sequence and the movie as a whole was no easy feat.

The production of "Bullitt" was as intense and gripping as the film itself. Directed by Peter Yates, a British filmmaker known for his work on "Robbery" (1967), the film was a leap into uncharted territory for American cinema. Yates’s expertise in staging realistic car chases was one of the key reasons McQueen fought to bring him on board. McQueen, who also served as the film's co-producer, was deeply involved in every aspect of the production, ensuring that "Bullitt" reflected his vision of an uncompromisingly cool and gritty detective story.

The screenplay, written by Alan R. Trustman and Harry Kleiner, was based on the novel Mute Witness by Robert L. Fish. The film retained the core story but took creative liberties to suit the cinematic format. McQueen envisioned Frank Bullitt as the embodiment of realism someone who could exist in the real world of law enforcement, without the theatrical flair often seen in Hollywood's portrayal of cops.

One of the standout elements of "Bullitt" is its setting. San Francisco wasn’t just a backdrop; it was a character in its own right. The city’s steep hills and narrow streets provided a natural stage for the now-legendary car chase. To capture the city’s essence, Yates worked closely with cinematographer William A. Fraker. They employed handheld cameras, unique angles, and a subdued color palette to create a gritty, almost documentary-like aesthetic. The result was a visual style that was both grounded and striking.

Of course, no discussion of "Bullitt" would be complete without diving into the 10-minute car chase that has become one of the most celebrated sequences in film history. Filming this scene was an enormous challenge that required weeks of preparation. The cars the Mustang GT driven by McQueen and a black Dodge Charger R/T were modified to handle the rigorous demands of the chase. McQueen, known for his love of racing and stunts, insisted on driving the Mustang himself for most of the sequence. His passion for authenticity pushed the crew to their limits, as McQueen wanted the audience to feel the speed, danger, and adrenaline.

The sequence was meticulously planned but executed with a sense of controlled chaos. Legendary stunt coordinator Bill Hickman, who also played the driver of the Charger, was instrumental in choreographing the chase. Hickman, along with McQueen and Yates, worked out every skid, jump, and hairpin turn, ensuring that the action felt spontaneous yet cohesive. To capture the speed and danger up close, camera rigs were mounted on the cars, and chase vehicles with cameramen strapped in captured the high-speed action. The result was a visceral, pulse-pounding experience that left audiences on the edge of their seats.

Behind the scenes, McQueen’s perfectionism sometimes clashed with the production schedule. He demanded multiple takes of certain scenes, particularly during the chase, to ensure every shot was flawless. This dedication extended to his wardrobe as well. McQueen worked with costume designer Theadora Van Runkle to craft Frank Bullitt’s iconic look most notably, the turtleneck sweater and tweed blazer that became synonymous with McQueen’s cool, understated style.

The film’s soundtrack, composed by Lalo Schifrin, also played a crucial role in defining its tone. Schifrin's jazz-inspired score underscored the tension and rhythm of the film, particularly during the quieter moments. His use of brass instruments and syncopated rhythms created an atmosphere that was both edgy and sophisticated.

Production wasn’t without its challenges. Filming in San Francisco came with logistical hurdles, as the city’s bustling streets and steep terrain posed risks to both the crew and equipment. The city itself, however, was highly cooperative, granting the filmmakers access to key locations. The final chase sequence was shot in multiple parts of the city, with clever editing stitching together footage to make the geography seem seamless. Observant viewers may notice that the cars pass the same landmarks more than once, a minor continuity issue that has since become part of the film’s charm.

Despite the meticulous planning, there were moments of genuine danger. During one high-speed section of the chase, a camera car was nearly hit, and on another occasion, a stunt driver lost control momentarily. These incidents only added to the adrenaline-fueled atmosphere on set, with every participant acutely aware that they were creating something groundbreaking.

The film’s final hospital sequence, which ends with Bullitt facing off against the villain on the tarmac at San Francisco International Airport, also required careful coordination. The airport granted the production limited access to its facilities, and the crew had to work quickly to capture the tense, climactic showdown without disrupting actual airport operations.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Faye Dunaway’s outfits in The Thomas Crown Affair, 1968

#faye dunaway#the thomas crown affair#norman jewison#60s#fashion film#fashion in film#60s style#60s fashion#theadora van runkle

488 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Troop Beverly Hills (1989)

#GIFCreatedByMgmpluto#Shelley Long#Shelly Long#Phyllis Nefler#Troop Beverly Hills#Fabulous#stunning#fashion#Theadora Van Runkle#Van Runkle#animated gif

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theadora Van Runkle costume sketch of Bette Davis for Myra Breckinridge (Michael Sarne, 1970) created in preproduction before Miss Davis turned down the role.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967).

#bonnie and clyde#Bonnie and Clyde (1967)#arthur penn#warren beatty#faye dunaway#burnett guffey#dede allen#dean tavoularis#raymond paul#theadora van runkle

320 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photographer Bruce McBroom took this iconic image of Michael at his mother's viewing. (His work on Godfather II was officially uncredited.) The all-black, three-piece suit was designed by Theadora Van Runkle and is also the one he is wearing when he seals Fredo's fate on New Year's Eve. Talk about your versatile pieces!

#al pacino#godfather II#the godfather#michael corleone#bruce mcbroom#theadora van runkle#movies#film#film photography

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Faye Dunaway in Theadora Van Runkle at the 40th Academy Awards at Santa Monica Civic Auditorium in Santa Monica, California on April 10th 1968.

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bonnie Parker (Faye Dunaway) Yellow target dress.. Bonnie & Clyde (1967).. Costume by Theadora Van Runkle..

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Butcher’s Wife (1991) costume design by Theadora van Runkle

#the butcher's wife#demi moore#amanda watches movies#mine#movieedit#movie edit#film edit#filmedit#style#summer vibes#theadora van runkle#costume design#costumes#costuming

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lucille Ball, Mame. 1974

85 notes

·

View notes